Abstract

The rate of mycophenolic acid (MPA) absorption after oral administration of mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) is delayed in patients with diabetes. Cyclosporine (CsA) decreases MPA exposure by inhibiting enterohepatic recirculation of MPA/MPA glucuronide, and tacrolimus (TRL) may alter the rate and extent of MPA absorption due to its prokinetic properties especially in patients with diabetic gastroparesis. This study evaluated the effect of changing from CsA to TRL on pharmacokinetics of MPA in stable renal transplant recipients with long-standing diabetes. Eight patients were switched from a stable dose of CsA to TRL while taking MMF 1 g twice daily. The 12-hour steady-state total plasma concentration–time profiles of MPA and MPA glucuronide were obtained after oral administration of MMF on 2 occasions: first while taking CsA and second after changing to TRL. Pharmacokinetic parameters of MPA were calculated by the noncompartmental method. Changing from CsA to TRL resulted in significantly increased MPA exposure (area under the concentration–time curve from 0 to 12 hours, AUC0–12) by 46 ± 32% (P = 0.012) and MPA predose concentration (C0) by 121 ± 67% (P = 0.008). The magnitude of change in MPA exposure did not correlate well with MPA-C0 or CsA trough concentration. Switching to TRL had minimal impact on peak concentration of MPA (15.0 ± 6.9 mg/L with CsA versus 16.1 ± 9.7 mg/L with TRL, P = 0.773) and time to reach the peak concentration (1.0 ± 0.4 hours with CsA versus 1.2 ± 0.8 hours with TRL, P = 0.461). Highly variable and unpredictable changes in MPA exposure among renal transplant patients with diabetes do not support a strategy of preemptively adjusting MMF dose when switching calcineurin inhibitors in this population.

Keywords: mycophenolic acid, pharmacokinetics, diabetes, cyclosporine, tacrolimus

INTRODUCTION

Mycophenolate mofetil (MMF; CellCept; Roche Laboratories, Inc., Nutley, NJ) is a prodrug of mycophenolic acid (MPA), a selective and reversible inhibitor of inosine 5′-monophosphate dehydrogenase (IMPDH) that inhibits lymphocyte proliferation. It is commonly used in combination with a calcineurin inhibitor [CNI; cyclosporine (CsA) or tacrolimus (TRL)] and corticosteroids to prevent rejection after solid organ transplantation. Many studies observed that the area under the concentration–time curve (AUC) and predose plasma concentration (C0) of MPA were significantly lower in patients taking MMF with CsA than in those taking MMF with TRL or without CsA.1–5 This differential effect of CNIs is because CsA inhibits the biliary secretion of MPA glucuronide (MPAG) through multidrug resistance protein 2 (MRP2) transporter, resulting in decreased MPA reabsorption during enterohepatic recirculation.6–8

Switching maintenance immunosuppression after transplant is very common9 and changing to an alternative CNI can alter MPA-AUC, potentially increasing the risk for rejection or the side effects from MMF. Although the general recommendation is to initiate MMF at a higher dose with CsA,10–12 no specific guidelines are available regarding MMF dose adjustment when CsA is switched to TRL in stable renal transplant patients. Because MPA pharmacokinetics exhibits considerable intersubject variability,10,13 the differential effect of CNIs on MPA exposure is difficult to quantify from published studies using cross-sectional or parallel-group comparisons.1–4 Results of a previously published crossover study were hampered by deterioration of renal function in the study participants, which may have altered MPA pharmacokinetics.5

Diabetes mellitus is the most common cause of end-stage renal disease in the United States, and gastroparesis is a frequent and clinically important complication in long-standing patients with diabetes, affecting 30%–50% of this patient population.14–16 A significant delay in oral absorption of MPA from MMF has been described in patients with and without diabetes with increased gastric emptying time.17–20 Because TRL is a macrolide that has intrinsic prokinetic properties, it has the potential to affect gastric emptying and to alter the pharmacokinetics of concomitant drugs.21,22 Therefore, switching patients from a CsA-based regimen to a TRL-based regimen may alter MPA pharmacokinetics by both eliminating the CsA-induced MRP2 inhibition and enhancing gastric emptying, especially in those patients with diabetic gastroparesis. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the MPA pharmacokinetics when CsA was changed to TRL in stable renal transplant recipients with long-standing diabetes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Our study was an open-label, sequential, 2-period crossover pharmacokinetic drug interaction study in stable renal transplant recipients with diabetes. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Michigan. After written informed consent was obtained, study participants were switched from CsA to TRL while maintaining the same dose of MMF. The 12-hour steady-state total plasma concentration–time profiles of MPA and MPAG were obtained after an oral morning dose of MMF on 2 separate occasions: (1) during coadministration with CsA (MMF-CsA) and (2) at the steady state after changing to TRL (MMF-TRL).

Study Subjects

Renal transplant recipients with diabetes, age 18 years or older, who were at least 6 months after transplant with calculated creatinine clearance >30 mL/min by Cockroft–Gault equation23 and receiving maintenance immunosuppressive therapy consisting of CsA (Neoral; Novartis Pharmaceuticals, East Hanover, NJ), MMF, and prednisone were eligible for study entry. Presence of diabetes mellitus was confirmed by patient medical history, laboratory studies documenting glucose intolerance, hemoglobin A1c, and the need for exogenous insulin therapy. Subjects who were pregnant, nursing, or smokers and those who had received extrarenal transplant were excluded. Drugs that were known to significantly affect gastrointestinal motility such as erythromycin, loperamide, metoclopramide, and tegaserod and those that might significantly alter CsA, TRL, or MMF pharmacokinetics such as bile acid resins, inhibitors, and inducers of cytochrome P450 3A and P-glycoprotein were prohibited during the study period.

Changing of CNIs

All subjects enrolled in this study had been on a stable dose of CsA for at least 2 weeks before study entry with whole-blood CsA trough concentrations of 100–200 ng/mL by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC).24,25 After completing the MMF-CsA pharmacokinetic study, subjects were instructed to discontinue CsA and start TRL 0.05 mg/kg twice daily 24 hours from the last dose of CsA. After the CNI change, subjects underwent safety assessment consisting of physical examination, vital signs, clinical laboratory evaluation including TRL trough concentration, and adverse events weekly up to 3 months. TRL dose was titrated to target whole-blood TRL trough concentrations of 5–10 ng/mL by HPLC–tandem mass spectrometry according to the center practice.24,25 Once steady state was achieved (defined by having at least 2 consecutive TRL trough concentrations within the target range on a stable dose of TRL), the MMF-TRL pharmacokinetic study was conducted. Throughout the study period, all subjects remained on their stable dose of prednisone and MMF 1 g twice daily.

Pharmacokinetic Analysis

In the morning of each pharmacokinetic study, subjects were admitted to the General Clinical Research Center at the University of Michigan after an overnight fast. Subjects took their regular morning dose of MMF and CNI (CsA for the MMF-CsA study and TRL for the MMF-TRL study) simultaneously at 12 hours after their last evening dose. Standardized meals were provided at 1, 5, and 10 hours after dosing. Serial blood samples were collected before and at 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, and 12 hours after administration of MMF and CNI.

Blood samples were centrifuged immediately after collection, and plasma was separated and stored at −80°C until analysis for MPA and MPAG. Plasma concentrations of total MPA and MPAG were measured by a validated HPLC assay at the Mayo Medical Laboratories (Rochester, MN). After thawing, each plasma sample was divided into 2 tubes. One tube (A) was used for direct measurement of unconjugated MPA concentration, and the other tube (B) was used to measure total hydrolyzed MPA concentration after glucuronidase treatment. The difference between unconjugated and total hydrolyzed MPA results allowed calculation of MPAG concentration. To tube A, 200 µL of the standards, controls, and samples was added, and to tube B, 50 µL of sample and 150 µL of blank plasma were added. To only tube B, 100 µL of 1:10 glucuronidase in sodium acetate buffer at pH 6.0 was added and incubated for 10 minutes at 37°C. To both tubes, 100 µL of the internal standard (5 µg/mL zomepirac in acetonitrile) was added. Excess sodium sulfate was added and centrifuged, and the supernatant was removed. The extract was dried under nitrogen at 30°C and reconstituted in 200 µL of the mobile phase. Using Class-VP LC system (Shimadzu Scientific Instruments, Columbia, MD), 30 µL of the reconstituted sample was injected onto a guard column (5 µm, 2 cm × 4.6 mm) and an analytical column (5 µm, 5 cm × 4.6 mm) (both Discovery C18; Supelco; Sigma–Aldrich, Bellefonte, PA) at room temperature. Chromatographic separation was achieved by delivering isocratic solvent with a mobile phase of 20% acetonitrile and 80% triethylamine phosphate buffer at pH 7.0 (final concentration of 25% triethylamine and 1.875 mmol/L potassium phosphate buffer), with a flow rate of 2.0 mL/min. Detection was achieved by monitoring the absorbance at 213 nm. MPA and the internal standard were eluted at 2.8 and 6.75 minutes, respectively. Concentrations were calculated by comparing peak–height ratios of the drug with those of the internal standard. The lower limit of quantification was 0.5 mg/L for MPA and 10 mg/L MPAG. The inter- and intra-assay coefficients of variation were <10%.

Pharmacokinetic parameters for MPA and MPAG were calculated by the noncompartmental method. The area under the concentration–time curve from 0 to 12 hours (AUC0–12) was calculated using the linear trapezoidal rule for ascending concentrations and the log trapezoidal rule for descending concentrations. The predose concentration (C0), the maximum concentration (Cmax), and the time to reach Cmax (Tmax) were determined visually from the concentration–time profiles. Apparent oral clearance of MPA (CL/F = dose/AUC0–12) was calculated after normalizing MMF dose for the subject’s body weight and by multiplying by the ratio of MPA molecular weight to MMF molecular weight.

Statistical Analysis

The impact of changing CNI on MPA AUC0–12 and C0 was determined by calculating the mean and SD of the percentage difference between the MMF-CsA phase and the MMF-TRL phase. To test the differences in pharmacokinetic parameters of MPA and MPAG and the biochemical laboratory variables between the 2 phases, a 2-sided paired t test for normally distributed data and the Wilcoxon signed rank test for non-Gaussian distribution were used. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Eight renal transplant recipients with diabetes participated in this study. Table 1 summarizes their demographic and laboratory characteristics. All subjects had juvenile-onset diabetes mellitus for 35 ± 7 years and hemoglobin A1c of 7.6 ± 1.8% (range 6.1%–11.6%) at the time of study entry. We did not perform radiological diagnostic studies for gastroparesis due to cost and concern for radiation exposure to the study participants.

TABLE 1.

Demographics and Biochemical Variables of Study Participants (n = 8)

| CsA | TRL | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs) | 46 ± 9 | — |

| Gender (male/female) | 4/4 | — |

| Race (White/Asian) | 7/1 | — |

| Living donor/deceased donor transplant | 5/3 | — |

| Time after transplant (mo) | 20 ± 14 | — |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.15 ± 0.27 | 1.13 ± 0.27 |

| Creatinine clearance (mL/min)* | 98 ± 40 | 101 ± 40 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.8 ± 0.3 | 3.8 ± 0.3 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 12.7 ± 1.0 | 12.3 ± 1.0 |

| Hemoglobin A1c (%) | 7.6 ± 1.8 | 7.6 ± 1.8 |

| Weight (kg) | 85.9 ± 20.7 | 86.9 ± 20.7 |

| CsA daily dose (mg/kg) | 3.24 ± 0.82 | — |

| CsA trough concentration (ng/mL) | 127 ± 31 | — |

| TRL daily dose (mg/kg) | — | 0.07 ± 0.02 |

| TRL trough concentration (ng/mL) | — | 8.5 ± 3.4 |

| Prednisone daily dose (mg/kg) | 0.11 ± 0.09 | 0.10 ± 0.09 |

Data are numbers or mean ± SD.

Creatinine clearance calculated by Cockroft–Gault equation19

All subjects tolerated well the change from CsA to TRL without experiencing any rejection episodes, allograft loss, or patient death during the follow-up period (94 ± 5 days). Three patients experienced adverse events including worsening of hypertension requiring the addition of an antihypertensive agent in the second month, an episode of shingles in the first month, and diarrhea in the first week after the change. No new-onset or worsening hematological abnormality or hyperlipidemia was observed. Serum creatinine, albumin, hemoglobin, and weight remained stable during the study period. No significant change in hemoglobin A1c occurred during this short follow-up, although insulin requirements increased in 3 patients. Steady-state TRL target trough concentrations were achieved at 32 ± 3 days after change and the MMF-TRL study was conducted after having been on a stable TRL dose for at least 14 days. All other medications remained unchanged throughout the study period.

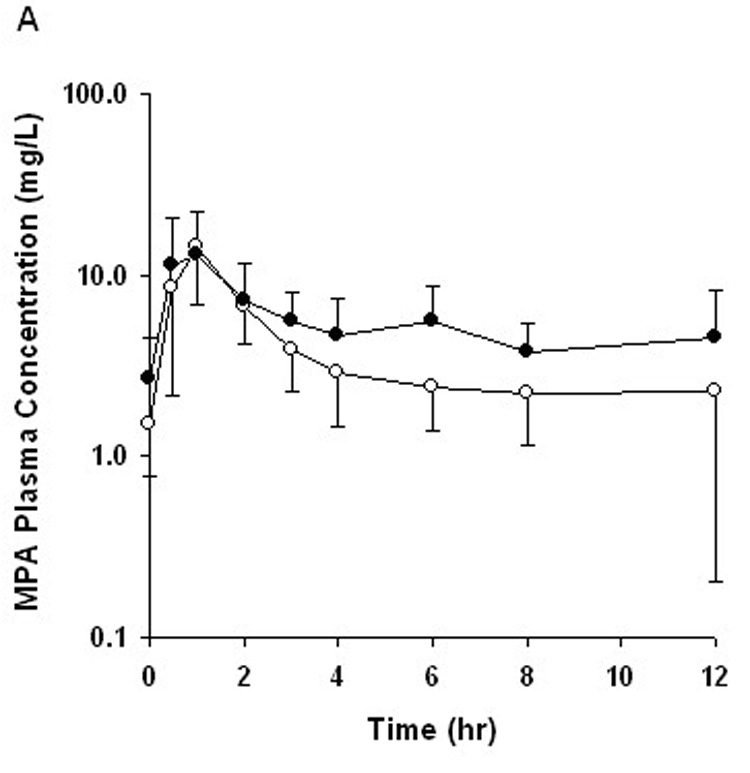

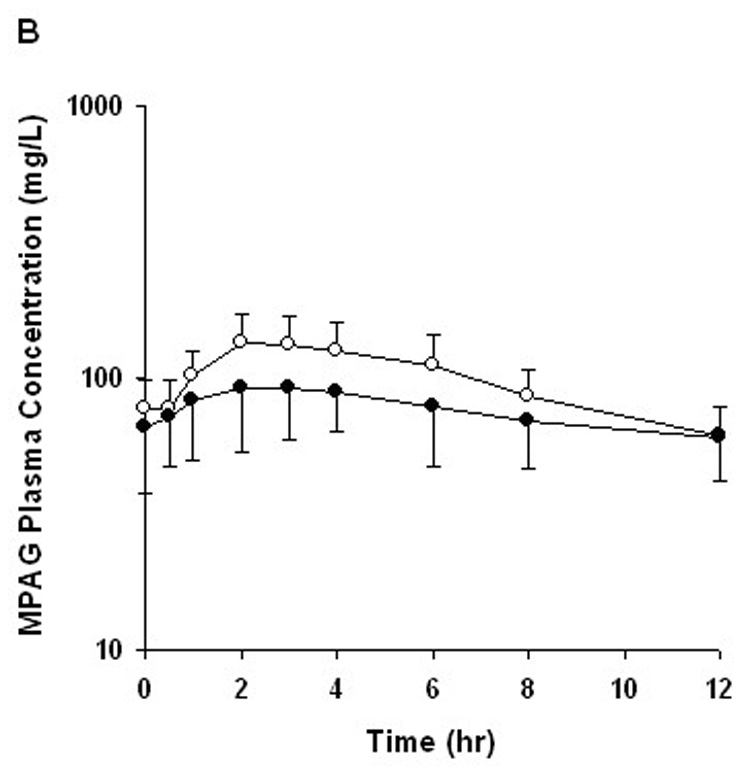

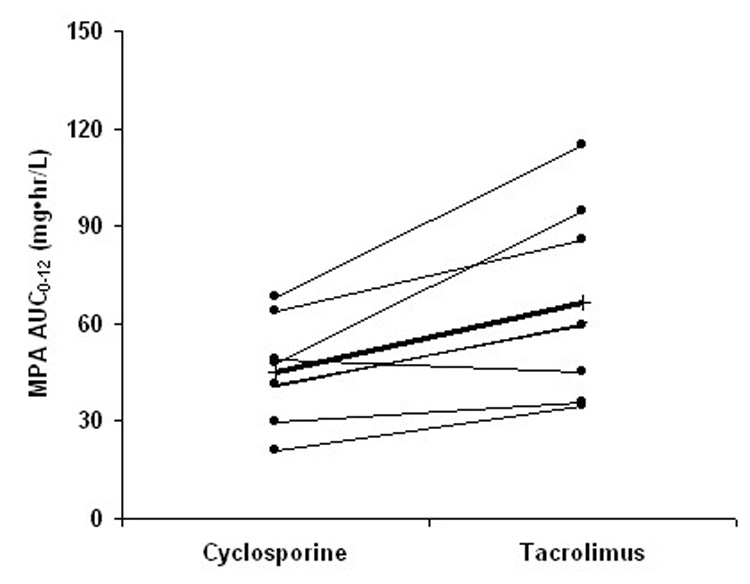

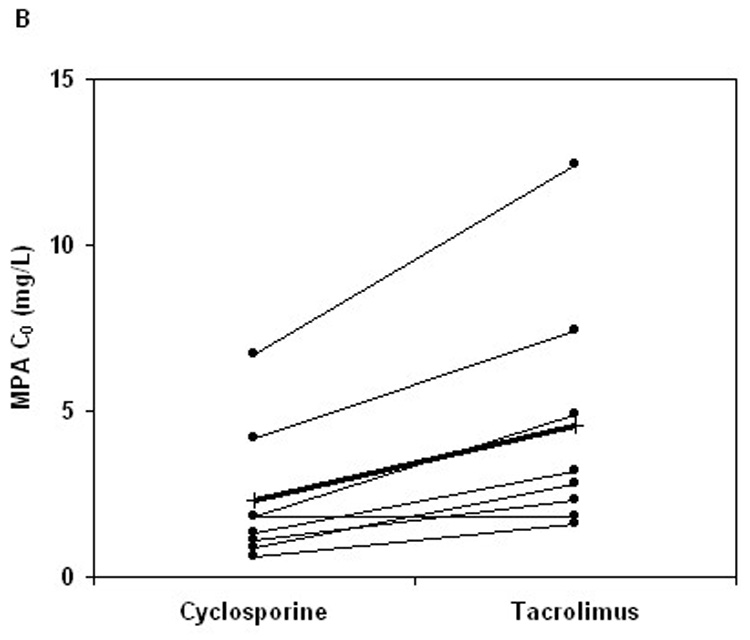

After oral administration of MMF in combination with either CsA or TRL, pharmacokinetic parameters of MPA and MPAG exhibited high intersubject variability, with MPA-C0 having the greatest variability (Table 2). The MPA plasma concentration–time profiles in the MMF-TRL phase showed a prominent second peak between 6 and 12 hours after MMF dosing, which was not observed in 6 of the 8 subjects during the MMF-CsA phase (Fig. 1). MPAG exposure was higher in the MMF-CsA phase compared with the MMF-TRL phase (Fig. 1; Table 2). When CsA was switched to TRL, AUC0–12 and C0 of MPA increased significantly by 46 ± 32% (range 8%–98%, P = 0.012) and 121 ± 67% (range 0%–211%, P = 0.008), respectively (Fig.2; Table 2). The percent change in MPA-AUC0–12 did not correlate well with the magnitude of change in MPA-C0 (r2 = 0.39, P = 0.10). Neither CsA-AUC0–12 nor CsA-C0 predicted the changes in MPA-AUC0–12 (r2 = 0.22, P = 0.24 and r2 = 0.08, P = 0.50, respectively). Apparent oral clearance of MPA was slightly lower in the MMF-TRL phase compared with the MMF-CsA phase, as expected from the increased reabsorption of MPA. No significant changes in Cmax and Tmax of MPA were observed after changing to TRL (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Pharmacokinetic Parameters of Mycophenolic Acid and Glucuronide Metabolite After MMF Administration in Combination With CsA or TRL (n = 8)

| CsA | TRL | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD (range) | CV% | Mean ± SD (range) | CV% | ||

| MPA | |||||

| AUC0–12 (mg·hr/L) | 45.2 ± 15.9 (20.8–68.4) | 35 | 66.2 ± 29.2 (34.7–114.8) | 44 | 0.012 |

| C0 (mg/L) | 2.3 ± 2.1 (0.6–6.7) | 91 | 4.6 ± 3.7 (1.6–12.4) | 81 | 0.008 |

| Cmax (mg/L) | 15.0 ± 6.9 (8.0–28.7) | 46 | 16.1 ± 9.7 (5.7–30.2) | 60 | 0.773 |

| Tmax (h) | 1.0 ± 0.4 (0.5–2.0) | 41 | 1.2 ± 0.8 (0.5–3.0) | 67 | 0.461 |

| CL/F (L h−1 kg−1) | 0.21 ± 0.05 (0.15–0.31) | 25 | 0.15 ± 0.05 (0.09–0.21) | 30 | 0.004 |

| MPAG | |||||

| AUC0–12 (mg·hr/L) | 1180 ± 291 (878–1663) | 25 | 913 ± 299 (695–1587) | 33 | 0.009 |

| C0 (mg/L) | 77 ± 21 (56–109) | 28 | 66 ± 29 (30–125) | 43 | 0.096 |

| Cmax (mg/L) | 144 ± 36 (92–199) | 25 | 102 ± 35 (68–180) | 34 | 0.019 |

| Tmax (h) | 2.7 ± 1.0 (1.9–4.0) | 35 | 2.1 ± 1.1 (1.0–4.0) | 53 | 0.142 |

CV, coefficient of variation.

FIGURE 1.

Mean plasma concentration–time profile for (A) mycophenolic acid (MPA) and (B) mycophenolic acid glucuronide (MPAG) after oral administration of MMF with CsA (open circle) and TRL (closed circle). Error bars represent SD of the mean (n = 8).

FIGURE 2.

Changes in (A) AUC0–12 and (B) predose plasma concentration (C0) of mycophenolic acid (MPA) after change of concomitant CNI from CsA to TRL (thin line: individual subject; thick line: mean; n = 8).

DISCUSSION

Diabetes mellitus is known to alter absorption and disposition of drugs partly due to gastroparesis.26 For MMF, diabetes seems to slow the rate of absorption of MPA without a significant effect on MPA exposure.17–19 Lower MPA-C0 was also observed in patients with diabetes compared with those without diabetes, but in this particular study, other pharmacokinetic parameters of MPA were not characterized.27 Because TRL has the potential to hasten gastric emptying, we hypothesized that coadministration of TRL and MMF could alter MPA absorption in patients with long-standing diabetes.

We observed a significant increase in MPA exposure when CsA was changed to TRL in stable renal transplant recipients with diabetes. In addition, we observed an even larger increase in MPA-C0 when CsA was changed to TRL. The magnitude of this change in MPA exposure was widely variable among patients, and CsA trough concentrations did not seem to have any predictive value for the change. The change in MPA-C0 did not have a strong correlation with MPA exposure. A similar discordant change in MPA-AUC0–12 and MPA-C0 after CNI change has also been reported with enteric-coated mycophenolate sodium in renal transplant recipients without diabetes (a mean increase of 19% in MPA-AUC0–12 and a mean increase of 200% in MPA-C0 from CsA to TRL).28

In our study, neither MPA-Cmax nor MPA-Tmax was significantly changed when CsA was switched to TRL. Although all subjects enrolled in our study had long-standing juvenile-onset diabetes mellitus that was not well controlled, no clear association exists between the length of diabetes and gastroparesis. One weakness of our study was the inability to measure gastric emptying, and it is possible that our study participants did not have severely impaired gastric motility as their MPA-Tmax was shorter than that reported in patients with diabetes but comparable to that observed in patients without diabetes from other studies.18,19

Changes in renal function, plasma albumin level, and hemoglobin level can alter clearance and protein binding of MPA and MPAG, contributing to the intrasubject variability in MPA pharmacokinetics.29 Because serum creatinine, plasma albumin, and hemoglobin remained stable within the subjects during our study, these parameters could not account for the increased MPA exposure with TRL in our study. In contrast to the parallel-group study design, our crossover study design accounted for the intersubject differences that may influence MPA pharmacokinetics such as UGT1A9 T-275A and C-2152T and MRP2 C-24T polymorphisms.30,31 Comparison of the MPA concentration–time profiles of the MMF-CsA and the MMF-TRL revealed that the difference in MPA exposure was attributed mainly to the reduced second peak between 6 and 12 hours after dose with CsA coadministration. Conversely, MPAG exposure was higher with CsA than with TRL. These findings support the proposed mechanism of CsA inhibition of MPA/MPAG enterohepatic recirculation.6,7

Because of large pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic variability of MPA, an interest is increasing in individualized dosing of MMF based on MPA concentrations, IMPDH activity, or both.10,13,32 Considering the inverse correlation between MPA exposure and the likelihood of rejection,33 a total MPA-AUC0–12 target of at least 30 mg·hr/L has been proposed to minimize the risk of rejection in a CsA-based regimen. Although more convenient than measuring AUC0–12, single determinants of MPA concentrations including C0 have limited correlation with total MPA exposure and clinical outcomes. Investigations to find simple and robust limited sampling strategies continue, and availability of data supporting their clinical benefits will determine wider acceptance of MPA therapeutic monitoring in patient care. Considerable intersubject variability also exists in baseline IMPDH activity, and clinical outcomes with MMF therapy seem to vary depending on the pretransplant IMPDH activity.34,35 A small cross-sectional study has reported lower IMPDH activity in stable renal transplant recipients with diabetes compared with the cohort without diabetes despite similar MPA-AUC0–12 in both groups.36 Whether the lower IMPDH activity in patients with diabetes reflects reduced basal IMPDH activity or higher pharmacological response to MPA is unclear without longitudinal monitoring of IMPDH activity in proper comparison groups. Moreover, how such differences affect graft outcome in patients with diabetes remains uncertain at this point. However, it should be noted that diabetes mellitus contributes to significant intersubject variability of MPA pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics; therefore, an MMF monitoring or dosing strategy that is developed in patients without diabetes may require careful validation in patients with diabetes because of the complex nature of diabetes.

CONCLUSIONS

This present study reports that MPA exposure was higher when the standard dose of MMF was taken in a TRL-based regimen compared with a CsA-based regimen in renal transplant recipients with diabetes mellitus. However, switching CsA to TRL did not seem to have significant impact on the rate of absorption of MPA, as judged by MPA-Tmax. The magnitude of change in MPA exposure was substantially variable among patients with diabetes and difficult to predict based on CsA trough concentrations and MPA-C0. In patients with diabetes whose CNI will be switched to the alternative, a strategy of preemptively adjusting MMF dose by a fixed amount in anticipation of altered MPA exposure may result in suboptimal MPA exposure and should be discouraged.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the Mayo Medical Laboratories and the University of Michigan Transplant Research Group, especially Karen Wisniewski, Darlene McLean, and Diane Hilfinger for their integral roles in the completion of the study. This study was supported by a grant from Astellas Pharma US, Inc., and in part by a grant (grant number M01-RR000042) from the National Center for Research Resources, a component of the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zucker K, Rosen A, Tsaroucha A, et al. Unexpected augmentation of mycophenolic acid pharmacokinetics in renal transplant patient receiving tacrolimus and mycophenolate mofetil in combination therapy, and analogous in vitro findings. Transplant Immunol. 1997;5:225–232. doi: 10.1016/s0966-3274(97)80042-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hübner GI, Eismann R, Sziegoleit W. Drug interaction between mycophenolate mofetil and tacrolimus detectable within therapeutic mycophenolic acid monitoring in renal transplant patients. Ther Drug Monit. 1999;21:536–539. doi: 10.1097/00007691-199910000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smak Gregoor PJH, de Sévaux RGL, Hené RJ, et al. Effect of cyclosporine on mycophenolic acid trough levels in kidney transplant recipients. Transplantation. 1999;68:1603–1606. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199911270-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pou L, Brunet M, Cantarell C, et al. Mycophenolic acid plasma concentrations: influence of comedication. Ther Drug Monit. 2001;23:35–38. doi: 10.1097/00007691-200102000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shipkova M, Armstrong VW, Kuypers D, et al. Effect of cyclosporine withdrawal on mycophenolic acid pharmacokinetics in kidney transplant recipients with deteriorating renal function: preliminary report. Ther Drug Monit. 2001;23:717–721. doi: 10.1097/00007691-200112000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Gelder T, Klupp J, Barten MJ, et al. Comparison of the effects of tacrolimus and cyclosporine on the pharmacokinetics of mycophenolic acid. Ther Drug Monit. 2001;23:119–128. doi: 10.1097/00007691-200104000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kobayashi M, Saitoh H, Tadano K, et al. Cyclosporin A, but not tacrolimus, inhibits the biliary excretion of mycophenolic acid glucuronide possibly mediated by multidrug resistance-associated protein 2 in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;309:1029–1035. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.063073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hesseling DA, van Hest RM, Mathot RAA, et al. Cyclosporine interacts with mycophenolic acid by inhibiting the multidrug resistance-associated protein 2. Am J Transplant. 2005;5:987–994. doi: 10.1046/j.1600-6143.2005.00779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meier-Kriesche HU, Chu AH, David KM, et al. Switching immunosuppression medications after renal transplantation—a common practice. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21:2256–2262. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfl134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Gelder T, Le Meur Y, Shaw LM, et al. Therapeutic drug monitoring of mycophenolate mofetil in transplantation. Ther Drug Monit. 2006;28:145–154. doi: 10.1097/01.ftd.0000199358.80013.bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Filler G, Zimmering M, Mai I. Pharmacokinetics of mycophenolate mofetil are influenced by concomitant immunosuppression. Pediatr Nephrol. 2000;14:100–104. doi: 10.1007/s004670050021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mourad M, Malaise J, Eddour DC, et al. Pharmacokinetic basis for the efficient and safe use of low-dose mycophenolate mofetil in combination with tacrolimus in kidney transplantation. Clin Chem. 2001;47:1241–1248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arns W, Cibrik DM, Walker RG, et al. Therapeutic drug monitoring of mycophenolate acid in solid organ transplant patients treated with mycophenolate mofetil: review of the literature. Transplantation. 2006;82:1004–1012. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000232697.38021.9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.U.S. Renal Data System. [Accessed January 23, 2008];Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; USRDS 2007 Annual Data Report: Atlas of Chronic Kidney Disease and End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States. 2007 Available at: http://www.usrds.org/2007/ref/B_prevalence_07.pdf.

- 15.Cohen DJ, St. Martin L, Christensen LL, et al. Kidney and pancreas transplantation in the United States, 1995–2004. Am J Transplant. 2006;6:1153–1169. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Horowitz M, O’Donovan D, Jones KL, et al. Gastric emptying in diabetes: clinical significance and treatment. Diabet Med. 2002;19:177–194. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2002.00658.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pescovitz MD, Gausch A, Gaston R, et al. Equivalent pharmacokinetics of mycophenolate mofetil in African-American and Caucasian male and female stable renal allograft recipients. Am J Transplant. 2003;3:1581–1586. doi: 10.1046/j.1600-6135.2003.00243.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Hest RM, Mathôt RAA, Vulto AG, et al. Mycophenolic acid in diabetic renal transplant recipients: pharmacokinetics and application of a limited sampling strategy. Ther Drug Monit. 2004;26:620–625. doi: 10.1097/00007691-200412000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Akhlaghi F, Patel CG, Zuniga XP, et al. Pharmacokinetics of mycophenolic acid and metabolites in diabetic kidney transplant recipients. Ther Drug Monit. 2006;28:95–101. doi: 10.1097/01.ftd.0000189898.23931.3f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Naesens M, Vwebeke K, Vanrenterghem Y, et al. Effects of gastric emptying on oral mycophenolic acid pharmacokinetics in stable renal allograft recipients. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;63:541–547. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2006.02813.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Costa A, Alessiani M, De Ponti F, et al. Stimulatory effect of FK506 and erythromycin on pig intestinal motility. Transplant Proc. 1996;28:2571–2572. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maes BD, Vanwalleghem J, Kupers D, et al. Differences in gastric motor activity in renal transplant recipients treated with FK-506 versus cyclosporine. Transplantation. 1999;68:1482–1485. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199911270-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cockroft DW, Gault MH. Prediction of creatinine clearance from serum creatinine. Nephron. 1976;16:31–41. doi: 10.1159/000180580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Annesley TM, Clayton L. Simple extraction protocol for analysis of immunosuppressant drugs in whole blood. Clin Chem. 2004;50:1845–1848. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2004.037416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Annesley TM. Application of commercial calibrators for the analysis of immunosuppressant drugs in whole blood. Clin Chem. 2005;51:457–460. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2004.043992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gwilt RR, Nahhas RR, Tracewell WG, et al. The effects of diabetes mellitus on pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics in humans. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1991;20:477–490. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199120060-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zanker B, Sohr B, Eder M, et al. Comparison of MPA trough levels in patients with severe diabetes mellitus and from non-diabetics after transplantation. Transplant Proc. 1999;31:1167. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(98)01948-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaplan B, Meier-Kriesche H-U, Minnick P, et al. Randomized calcineurin inhibitor cross over study to measure the pharmacokinetics of co-administered enteric-coated mycophenolate sodium. Clin Transplant. 2005;19:551–558. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2005.00387.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Hest RM, Mathot RAA, Pescovitz MD, et al. Explaining variability in mycophenolic acid exposure to optimize mycophenolate mofetil dosing: a population pharmacokinetic meta-analysis of mycophenolic acid in renal transplant recipients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:871–880. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005101070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kuypers DRJ, Naesens M, Vermeire S, et al. The impact of uridine diphosphate-glucuronsyltransferase 1A9 (UGT1A9) gene promoter region single-nucleotide polymorphisms T-275A and C-2152T on early mycophenolic acid dose-interval exposure in de novo renal allograft recipients. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2005;78:351–361. doi: 10.1016/j.clpt.2005.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Naesens M, Kuypers DR, Verbeke K, et al. Multidrug resistance protein 2 genetic polymorphisms influence mycophenolic acid exposure in renal allograft recipients. Transplantation. 2006;82:1074–1084. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000235533.29300.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weimert NA, DeRotte M, Alloway RR, et al. Monitoring of inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase activity as a biomarker for mycophenolic acid effect: potential clinical implications. Ther Drug Monit. 2007;29:141–149. doi: 10.1097/FTD.0b013e31803d37b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Gelder T, Hilbrands LB, Vanrenterghem Y, et al. A randomized double-blind, multicenter plasma concentration controlled study of the safety and efficacy of oral mycophenolate mofetil for the prevention of acute rejection after kidney transplantation. Transplantation. 1999;68:261–266. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199907270-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Glander P, Hambach P, Braun KP, et al. Effect of mycophenolate mofetil on IMP dehydrogenase after the first dose and after long-term treatment in renal transplant recipients. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2003;41:470–476. doi: 10.5414/cpp41470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Glander P, Hambach P, Braun KP, et al. Pre-transplant inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase activity is associated with clinical outcome after renal transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2004;4:2045–2051. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00617.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Patel CG, Richman K, Yang D, et al. Effect of diabetes mellitus on mycophenolate sodium pharmacokinetics and inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase activity in stable kidney transplant recipients. Ther Drug Monit. 2007;29:735–742. doi: 10.1097/FTD.0b013e31815d8ace. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]