Abstract

Severe dengue virus (DENV) infection is epidemiologically linked to pre-existing anti-DENV antibodies acquired by maternal transfer or primary infection. A possible explanation is that DENV immune complexes evade neutralization by engaging Fcγ receptors (FcγR) on monocytes, natural targets for DENV in humans. Using epitope-matched humanized monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) and stable FcγR-transfected CV-1 cells, we found that DENV neutralization by IgG1, IgG3, and IgG4 mAbs was enhanced in high-affinity FcγRIA transfectants and diminished in low-affinity FcγRIIA transfectants, whereas neutralization by IgG2 mAbs (low-affinity ligands for both FcγRs) was diminished equally. In FcγR-negative Vero cells, IgG3 mAbs exhibited the strongest neutralizing activity and IgG2, the weakest. Our results demonstrate that DENV neutralization is modulated by the Fc region in an IgG subclass manner, likely through effects on virion and FcγR binding. Thus, the IgG antibody subclass profile generated by DENV infection or vaccination may independently influence the magnitude of the neutralizing response.

Keywords: Dengue virus, virus neutralization, humanized monoclonal antibody, Fc receptor

Introduction

Current experimental evidence supports a multi-hit occupancy model of flavivirus neutralization where antibodies directed at a virion envelope protein interfere with attachment or fusion if coating levels are high enough (reviewed in: (Pierson et al., 2008)). This notion also suggests an explanation for the paradox of enhanced flavivirus infection by neutralizing antibodies in Fcγ receptor (FcγR)-bearing cells; at lower levels of antibody occupancy, which are sub-neutralizing in nature, virus-immune IgG complexes can enhance dengue virus (DENV) attachment by engaging FcγRs and infection of monocyte/macrophages (Mo/Mϕ). This in vitro finding provides the basis for a hypothesis of antibody-dependent enhanced infection (ADE) to explain more severe infection in individuals with pre-existing DENV antibodies acquired by maternal transfer or primary infection (reviewed in: (Halstead, 2003)). DENVs exist as four serologically distinct but antigenically related virus types (DEN1 through 4), which can cause sequential human infection. Homotypic antibodies confer durable DENV serotype-specific immunity whereas cross-reactive neutralizing antibodies are generally weaker and less protective, and presumably can more readily form DENV immune complexes that remain infectious upon FcγR engagement.

FcγRs comprise a multi-gene family of type 1 integral membrane glycoproteins (reviewed in: (Nimmerjahn and Ravetch, 2008)). Among these, IgG receptors of two activation FcγR classes displayed on DENV-permissive human Mo/Mϕ and dendritic cells (DCs) have specifically been shown to modulate DENV immune complex infectivity (Boonnak et al., 2008; Kou et al., 2008; Littaua, Kurane, and Ennis, 1990; Mady et al., 1991; Rodrigo et al., 2006). The first, FcγRIA (CD64), has high affinity for both monomeric and complexed IgG and is found exclusively on antigen-presenting macrophages and DCs. The second, FcγRIIA (CD32), exists in two allotypic forms (H/R131) that preferentially bind multimeric IgG complexes with at least 100-fold lower affinity than FcγRIA. FcγRIA acquires signaling function by association with the common γ-chain subunit, whereas the FcγRIIA ligand binding chain is intrinsically signaling-competent.

The DENV virion E protein ectodomain is comprised of three domains (DI, DII, DIII), each of which is targeted by neutralizing antibodies. However, the IgG subclass and antigenic distribution of naturally stimulated neutralizing antibodies remains to be fully elucidated and molecular dissection of DENV immune complex interaction with FcγRs is just beginning. Here, we use epitope-matched humanized mAb Fc variants to evaluate the effect of IgG subclass on DENV virion binding, and neutralization in African green monkey kidney Vero and CV-1 cells which lack Fc receptors, and in CV-1 cells which were stably transfected to express human FcγRIA or FcγRIIA. Our results demonstrate that DENV neutralization is modulated in an IgG subclass manner, possibly through independent Fc effects on virion and FcγR binding.

Results

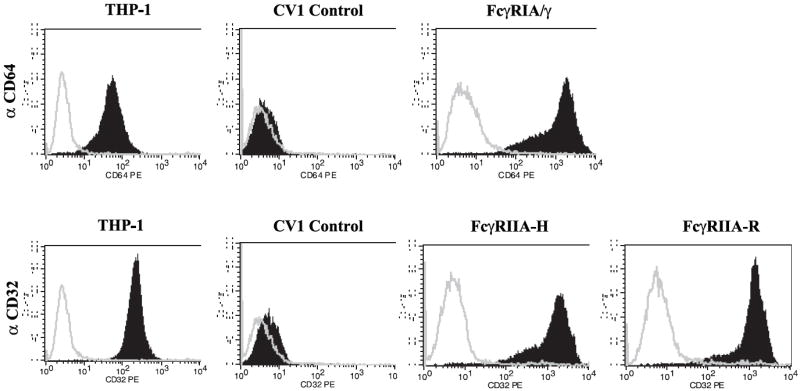

Functional human FcγRs displayed on DENV-permissive CV-1 cells

We evaluated DENV immune complex interactions with FcγRIA and FcγRIIA transfected individually into Fc receptor-negative CV-1 cells, which like Vero cells are used in conventional DENV plaque reduction neutralization (PRNT) assays. Coding sequences of human γ chain and FcγRIA arranged in a bicistronic expression cassette to ensure optimal and equivalent protein expression (Rodrigo et al., 2006), and those of both human FcγRIIA allotypes were respectively integrated into the identical single chromosomal site in CV-1/FRT cells. A CV-1 empty vector-transfected cell line served as the FcγR-negative CV-1 cell control. The three FcγR-expressing CV-1 cell lines (Fig. 1A) displayed the respective FcγR type in comparable abundance (~300,000 FcγR molecules per cell) that was essentially unchanged during continuous culture for ~3 months.

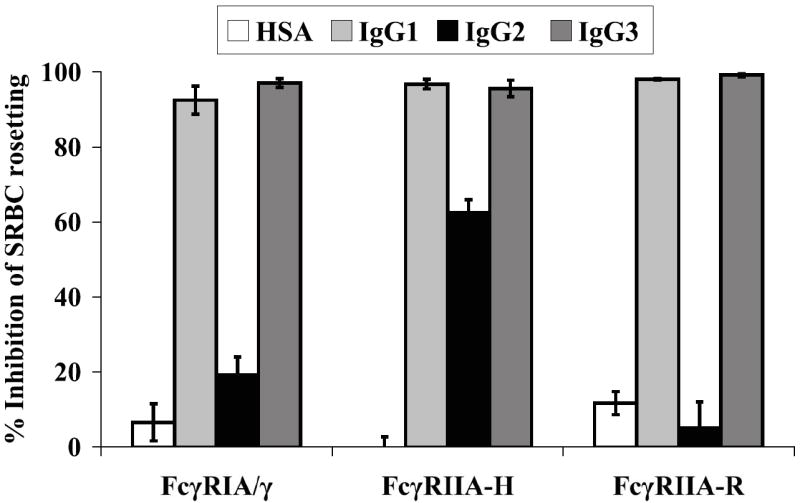

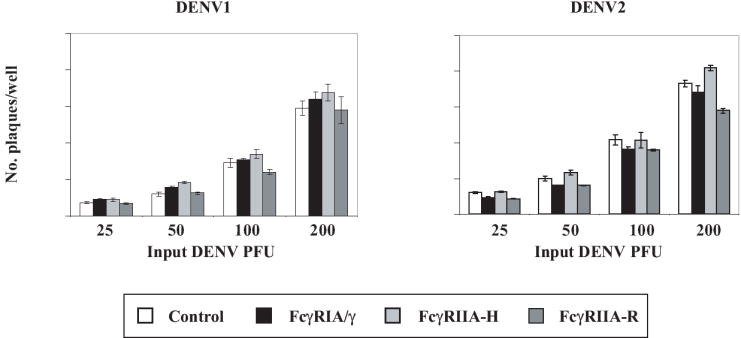

Figure 1. CV-1 cell lines display functional human FcγRIA/γ and FcγRIIA.

(A) FcγR expression. PE-labeled monoclonal antibodies against FcγRIA (CD64) or FcγRIIA (CD32) were used with corresponding labeled isotype controls to verify FcγR expression by flow cytometry. Human macrophage-like THP-1 cells which express FcγRIA and FcγRIIA (Fleit and Kobasiuk, 1991), served as a staining control. Results are representative of at least 6 independent determinations performed during an approximately 3-month period of continuous culture of the FcγR transfectants. (B) Competition-inhibition by aggregated IgG myeloma proteins. Pre-treatment of FcγRIA and FcγRIIA transfectants with heat-aggregated human IgG1 and IgG3 myeloma proteins inhibited (≥ 90%) rosette formation by rabbit IgG-sensitized sheep red blood cells (SRBC). IgG2 myeloma protein preferentially bound to FcγRIIA-H (~60% rosette inhibition). Mean values of triplicate samples and S.E.M. are plotted. Data are representative of four similar experiments. (C) Efficiency of DENV plaque formation in CV-1 transfectants. CV-1 transfectants were infected with serial two-fold (25 to 200) PFU of DENV1 or DENV2. Plaques were detected by indirect immunostaining with a broad DENV serogroup-reactive NS1-specific monoclonal antibody (9A9). Mean values and S.E.M. are indicated for each condition. Differences in plaque numbers over the range of input DENV PFU were not significant (P>0.92, one-way ANOVA). Graphs were generated from an experiment performed in triplicate for both DENV serotypes and are representative of three similar experiments.

IgG engagement by the FcγR transfectants was assessed by a competition binding assay (Fig. 1B). The FcγRIA and FcγRIIA transfectants efficiently bound (82%-97%) rabbit IgG opsonized sheep red blood cells (SRBC) forming rosettes; control CV-1 transfectants did not bind SRBC. To verify predicted IgG complex binding profiles among the FcγRs (Bruhns et al., 2009) we measured the ability of human IgG myeloma protein aggregates of different subclasses to inhibit SRBC rosette formation (Figure 1B). IgG aggregates exhibit properties of immune complexes and FcγR engagement by these particular myeloma proteins has previously been measured (Anderson and Abraham, 1980). Competition binding profiles among the different FcγRs were mainly in agreement with those predicted from a comprehensive reexamination of human FcγR binding preferences (Bruhns et al., 2009); concordantly, pre-treatment with human IgG1 and IgG3 myeloma proteins almost completely abrogated binding of opsonized SRBC by all three FcγR types, whereas inhibition of rosette formation by IgG2 aggregates was mainly found in the FcγRIIA-H131 transfectant (~65%). In contrast, however, we found that IgG2 aggregates bound to FcγRIA, albeit weakly (~20% rosette inhibition), but appeared not to bind to FcγRIIA-R131.

We next measured efficiencies of DENV1 and DENV2 plaque formation among control and FcγR expressing CV-1 cell lines in the absence of antibody and found them to be comparable (Fig. 1C). Similarly, the amount of DENV2 released into infected cell culture supernatants over a 72 hr interval was similar among the four CV-1 cell lines (data not shown).

Chimeric DENV mAbs with distinct human Fc regions

All IgG subclasses are represented in the antibody response to human DENV infection and transferred maternally (Watanaveeradej et al., 2003), but how IgG antibody subclass influences DENV neutralization is incompletely understood. Chimeric DENV mAbs of known epitope specificity with distinct human Fc domains offer novel tools to address this question. Summarized in Table 1 are the properties of three such epitope-matched DENV mAb panels comprising different human IgG subclasses. The first, mAb DV1-E50, was originally generated as a mouse IgM after immunization with DIII of DENV1 envelope protein. Its epitope maps to the A-strand of DIII (residues K307 and K310) by cell surface display of DIII mutants on yeast (S. Sukupolvi-Petty and M. Diamond, unpublished results). DV1-E50 is DENV sub-complex specific, binding (weakly) to DENV2 and DENV3, but not to DENV4. The second, mAb WNV-E60 (mouse IgG2a), was generated after immunization with West Nile virus (WNV). It is flavivirus cross-reactive and maps to amino acids within WNV DII fusion loop (Oliphant et al., 2006). Recombinant Fc switch variants of mAbs DV1-E50 and WNV-E60 incorporate a full-length heavy chain constant region corresponding to each human IgG subclass. The third chimeric mAb, 1A5, was generated from a chimpanzee that was sequentially infected with all four DENV serotypes, and is directed at a flavivirus cross-reactive site on the DII fusion loop (Goncalvez, Purcell, and Lai, 2004). It incorporates a full-length human IgG1 heavy chain (1A5 WT). Notably, sub-neutralizing concentrations of mAb 1A5 WT enhanced DENV4 replication in monkey primary blood monocytes and DENV4 viremia in monkeys after passive transfer (Goncalvez et al., 2007). Focused IgG2 or IgG4-specific amino acid residue substitutions in the FcγR-binding motif of 1A5 WT produced mutants with FcγR binding properties of IgG2 (1A5 ΔB) and IgG4 (1A5 ΔA); a 9-amino acid deletion at the 1A5 WT Fc N terminus (1A5 ΔD) completely abrogated FcγR attachment (Goncalvez et al., 2007).

Table 1.

Humanized monoclonal antibodies: Antigenic, neutralization, and virion binding properties

| Chimeric mAb | mAb Isotype | PRNT50 (μg/ml) a | Virion binding (Kd-app, nM) b | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mouse-human | |||||

| DV1-E50 (D-III) c | DENV1 | DENV2 | DENV1 | DENV2 | |

| DV1-E50-1 | IgG1 | 0.18 | - | 11.9 | - |

| DV1-E50-2 | IgG2 | 0.95 | - | 19.0 | - |

| DV1-E50-3 | IgG3 | 0.02 | - | 8.1 | - |

| DV1-E50-4 | IgG4 | 0.10 | - | 15.4 | - |

| WNV-E60 (D-II) | |||||

| WNV-E60-1 | IgG1 | 0.39 | 0.03 | 20.8 | 9.1 |

| WNV-E60-2 | IgG2 | 1.52 | 0.30 | 19.4 | 8.6 |

| WNV-E60-3 | IgG3 | 0.17 | 0.01 | 7.7 | 7.2 |

| WNV-E60-4 | IgG4 | 0.38 | 0.04 | 9.3 | 7.2 |

| Chimpanzee-human | |||||

| 1A5 (D-II) | |||||

| 1A5 WT | IgG1 | - | 0.84 | - | 21.0 |

| 1A5 ΔA | IgG4 | - | 0.89 | - | 18.4 |

| 1A5 ΔB | IgG2 | - | 0.83 | - | 46.7 |

| 1A5 ΔD | IgG9X d | - | 0.82 | - | 22.5 |

50% Plaque reduction neutralization (PRNT50) end-point titers in Vero cells calculated by probit analysis.

Values represent the apparent Kd (Kd-app) calculated for the mAb concentration that produced 50% of maximum virion binding determined by ELISA.

DENV envelope E domain (D) specificity.

9-amino acid Fc deletion into the 1A5 Fc CH2 domain.

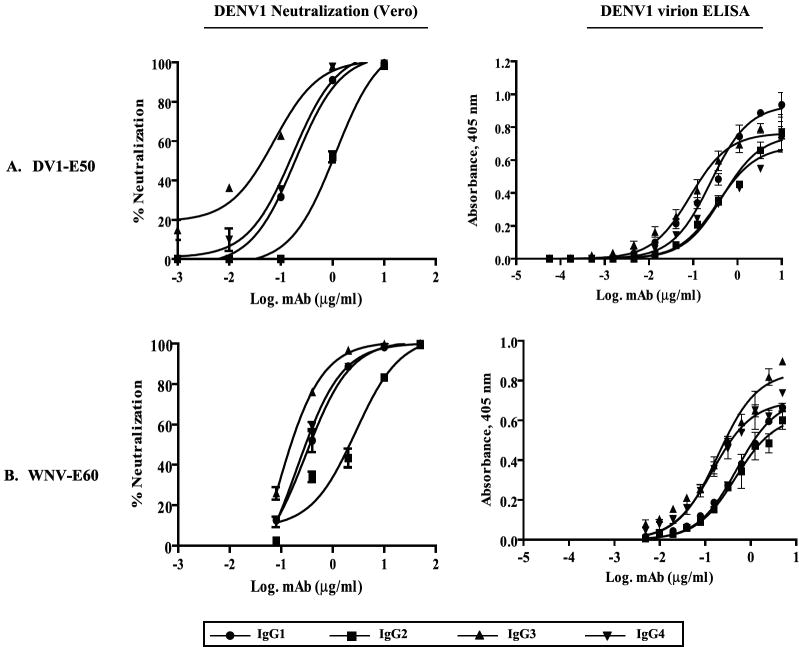

mAb Fc variants differentially neutralize DENV in Fc receptor-negative Vero cells and bind virions in an ELISA

To evaluate a possible Fc region effect on neutralization independent of FcγR engagement, we generated DENV neutralization dose response curves with each chimeric mAb in Vero cells, which lack expression of Fc receptors.(Table 1, Fig. 2). We observed divergent PRNT50 titers and neutralization dose responses among mAb DV1-E50 and mAb WNV-E60 full-length Fc switch variants; the IgG3 versions of both mAbs exhibited the most potent neutralizing activity against DENV1 or DENV2, and the IgG2 versions were the least potent (Fig. 2A-C). Because several recent studies suggested that the Fc region of a given IgG subclass could modulate antigen specificity and affinity of anti-cryptococcal antibodies (Dam et al., 2008; Torres and Casadevall, 2008; Torres et al., 2007), we reasoned that at least part of the altered neutralization profiles by the IgG switch variants could be a function of differential avidity for DENV particles. To test this, we measured whether antibody subclasses of a given mAb differentially bound intact DENV virions in a capture ELISA (Fig 2). Whereas differences in neutralization potency were substantial among the full-length IgG variants (up to ~10-fold), their differential effects on virion binding were relatively small (~2-fold, or less). Nevertheless, the neutralization and virion binding assay profiles appeared roughly concordant particularly with respect to differences between the full-length IgG3 and IgG2 variants. Among mAb DV1-E50 Fc variants, the IgG3 version, which exhibited the highest neutralizing potency, also bound more avidly than did the much more weakly neutralizing IgG2 version (Table 1, Fig. 2A). However, divergent binding avidities comparable to those of the IgG3 and IgG2 versions, were also observed between mAb DV1-E50 IgG1 and IgG4, respectively although these mAbs exhibited similar intermediate neutralizing potencies, With mAb WNV-E60, both IgG3 and IgG4 versions bound DENV1 (Fig. 2B) and DENV2 (Fig. 2C) comparably and more strongly than did the IgG1 and IgG2 versions. Notably, we found no differences in neutralization or virion binding profiles among the mAb 1A5 Fc variants, which contain focal mutations that alter IgG subclass specificity (Fig. 2D). Thus, our findings agree with the studies involving cryptococcal antibodies and suggest that the constant region of the heavy chain of IgG can alter antigen specificity, which affects the neutralizing potential of mAbs against DENV in the absence of FcγR interactions.

Figure 2. Differential binding and neutralization by anti-DENV humanized IgG mAbs.

DENV virion binding and neutralization by purified chimeric mouse-human mAb variants (DV1-E50; WNV-E60) or chimpanzee-human mAb variants (1A5 WT, 1A5 ΔA, 1A5 ΔB). MAb DV1-E50 or WNV-E60 variants incorporated a full-length Fc region corresponding to each human IgG subclass whereas mAb 1A5 variants contained focused amino acid substitutions in the 1A5 WT IgG1 Fc portion that conferred IgG2 (1A5 ΔB) or IgG4 (1A5 ΔA) ligand properties for FcγR binding; a 9-amino acid deletion (1A5 ΔD) abrogated FcγR binding entirely. DENV neutralization dose-response and virion binding curves were generated by parallel plaque reduction neutralization assay in Fc receptor-negative Vero cells and virion-capture ELISA assay, respectively. (A) MAb DV1-E50 IgG subclass variants titrated against DENV1. (B, C) MAb WNV-E60 IgG variants titrated against DENV1 and DENV2, respectively. (D) MAb 1A5 IgG variants titrated against DENV2. Plaques were detected by indirect immunostaining with a DENV NS1-specific monoclonal antibody (9A9) and neutralization dose-response curves were generated using GraphpadPrism5 software. Mean values and S.E.M. of triplicate ELISA determinations and duplicate or triplicate neutralization determinations are plotted. ELISA and neutralization results are representative of at least two similar studies.

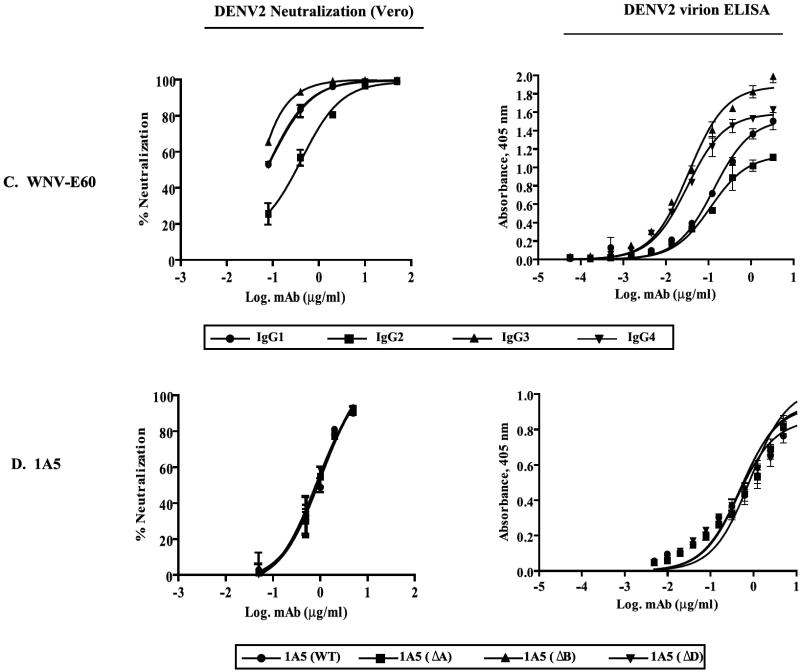

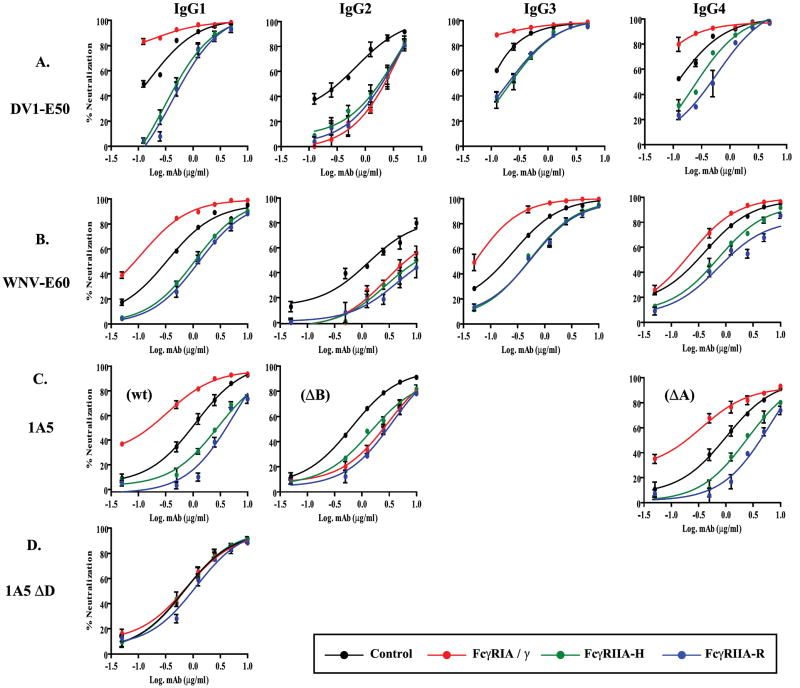

FcγR class differentially modulates DENV neutralization by mAb Fc variants

We next compared DENV neutralization potencies among the mAbs in FcγR-transfected and control CV-1 cell lines (Figure 3). Overall, DENV neutralization by IgG1, IgG3, and IgG4 mAbs was enhanced in high-affinity FcγRIA transfectants and diminished in low-affinity FcγRIIA transfectants compared to neutralizing activity in control CV-1 cells. Notably, IgG2 mAbs, which are low-affinity ligands for both FcγRIA and FcγRIIA, exhibited comparably diminished neutralization potency in each FcγR type (Fig. 3A-C). IgG2 DENV immune complexes, which are expected to bind to both FcγRIIA allotypes (Bruhns et al., 2009), were neutralized with similar efficiency in FcγRIIA-H131 and FcγRIIA-R131 transfectants.

Figure 3. Neutralization of DENV by humanized IgG mAbs in FcγR transfectants.

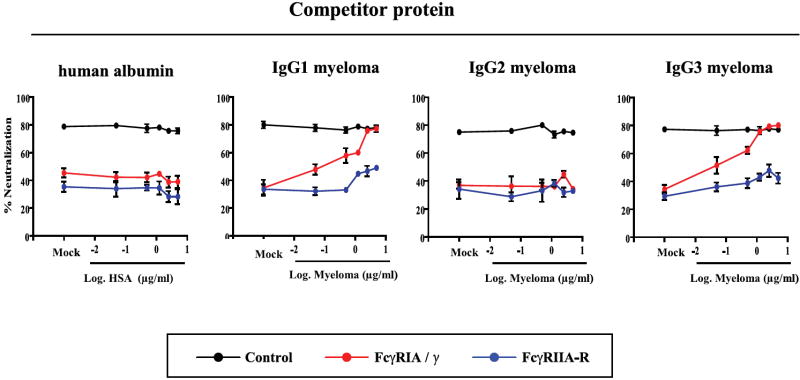

DENV (200 PFU) was incubated with graded concentrations of purified mAbs and the mixtures were used to generate neutralization dose-response curves in control and FcγRIA/γ or FcγRIIA stably transfected CV-1 cells. (A) mAb DV1-E50 variants titrated against DENV1. (B) mAb WNV-E60 variants titrated against DENV1. (C) mAb 1A5 WT (IgG1), 1A5 ΔB (IgG2), 1A5 ΔA (IgG4) titrated against DENV2. (D) mAb 1A5 ΔD titrated against DENV2. (E) FcγRIA- or FcγRIIA-expressing CV-1 cells were treated with a mixture of DENV1 immune complexes formed with DENV1 (200 PFU) and mAb DV1-E50 IgG2 (1 μg/ml), and graded concentrations (0.01 to 10 μg/ml) of purified human IgG1, IgG2, IgG3 myeloma proteins or control human serum albumin (HSA). FcγRIA but not FcγRIIA-modulated neutralization was blocked by the high-affinity IgG1 and IgG3 myeloma proteins only. Plaques were detected by indirect immunostaining with a DENV NS1-specific monoclonal antibody (9A9). Mean values and S.E.M. of triplicate infections are plotted. Results are representative of at least three (A-D) or two (E) similar experiments.

A specific effect of FcγR engagement on neutralization by the mAb IgG subclass variants is highlighted by the neutralization profile of mAb 1A5 ΔD (which is not bound by FcγR): neutralization was identical among the FcγR-expressing and control CV-1 cells (Fig. 3D). Thus, transfectants are comparably susceptible to DENV infection and neutralization in the presence of an antibody that cannot engage FcγRs.

The striking reduction in DV1-E50 and WNV-E60 IgG2 neutralizing potency in FcγRIA/γ transfectants compared to that of the other IgG subclass versions was surprising. Since FcγRIA has relatively little affinity for IgG2 (Fig. 1B), we questioned whether the neutralization disparity involved engagement of this receptor at all. Shown in Fig. 3E are results of a competition experiment designed to address this possibility. We measured neutralization of DENV1 by mAb DV1-E50 IgG2 in the CV-1 transfectants in the presence of graded amounts of human IgG1, IgG2, or IgG3 myeloma proteins using human serum albumin (HSA) as an irrelevant protein control. Treatment with increasing amounts of high-affinity IgG1 and IgG3 myeloma proteins, which bind avidly to FcγRIA, progressively increased DV1-E50 IgG2 neutralizing potency in a dose-dependent manner that approached but did not exceed that observed in control CV-1 cells. No such effect was observed in FcγRIIA-expressing CV-1 cells or in either FcγR cell type by treatment with human IgG2 myeloma or control HSA. These results suggest that the DENV IgG2 immune complexes bind FcγRIA and that neutralization is decreased by FcγRIA/γ engagement, an effect opposite to that observed with DENV complexed by other IgG antibody subclasses.

Discussion

In this study, we evaluated how engagement of human IgG antibody Fc and FcγRs modulates DENV neutralization. To do so, we used epitope-matched mAb switch variants corresponding to each IgG subclass and stable transfectants that display functional FcγR types individually, and in comparable abundance. Several conclusions emerge from our findings. First, FcγRIA/γ and FcγRIIA modulate DENV neutralization in an antibody subclass-dependent manner. Neutralization potency was proportional to FcγR-DENV immune complex binding avidity such that overall, neutralization by IgG1, IgG3, and IgG4 mAbs was enhanced in high-affinity FcγRIA transfectants and markedly diminished in low-affinity FcγRIIA transfectants. Neutralization by IgG2 mAbs (low-affinity ligands for both FcγR types) was diminished equally. Because depressed IgG2 antibody-mediated DENV neutralization in FcγRIA/γ-expressing cells was reversed by FcγRIA blockade (Fig. 3E), we speculate that FcγRIA/γ binding and/or signaling contributes to neutralization through an as yet undetermined mechanism.

Our finding that DENV neutralization was enhanced by high-affinity FcγRIA/γ engagement is consistent with a recent study of HIV immune complex infectivity in FcγR transfectants (Perez et al., 2009). HIV neutralization by IgG1 or IgG3 mAbs directed to gp41 was enhanced in FcγRIA/γ-expressing TZM-bl cells. In apparent contrast to the present results with DENV, the FcγRIA/γ neutralization enhancing effect with HIV was highly epitope-specific and neutralization potency among the HIV mAbs was generally the same in control and FcγRIIA-expressing cells. However, a single mAb and HIV strain combination exhibited somewhat reduced virus neutralization in FcγRIIA transfectants; low-affinity IgG2 immune complexes were not studied.

Our second key finding emerges from neutralization measurements performed in cells lacking FcγRs. Here, IgG3 variants of mAbs DV1-E50 and WNV-E60 neutralized DENVs in Vero cells more efficiently than did other IgG subclasses, with IgG2 variants being the least potent. The superiority of human IgG3 antibody neutralizing potency has been observed with other viruses, most notably HIV (Cavacini et al., 1995; Liu et al., 2003; Scharf et al., 2001) and our results suggest that IgG3 antibodies may preferentially neutralize DENVs as well. This property has been explained by an inherently greater flexibility of IgG3 and evidence of an allosteric effect of the IgG heavy-chain constant region on Fab affinity and specificity (reviewed in (Torres and Casadevall, 2008)). The link between neutralization potency in Vero cells and virion binding avidity among mAb DV1-E50 and WNV-E60 switch variants appeared imperfect as no discernable difference in neutralizing potency was observed among the mAb 1A5 variants in Vero cells. However, the mAbs DV1-E50 and WNV-E60 incorporate complete human heavy chain constant regions, whereas the mAb 1A5 variants were prepared by limited Fc region amino acid substitutions known to confer IgG subclass-specific FcγR binding (Armour et al., 1999; Armour et al., 2003; Goncalvez et al., 2007), but perhaps not alter virion binding. It is worthwhile also considering that discrepancies between virion binding avidity and neutralization potency might reflect other properties of a particular neutralizing antibody such as whether it acts by blocking virion attachment or fusion.

Taken together, the data suggest that IgG neutralization potency is modulated by a combined Fc effect on virion avidity of binding (e.g. hinge flexibility) and FcγR preference. Whether these Fc functions act independently to influence DENV neutralization and what other Fc effects on DENV infectivity might be operating, will be addressed in future experiments.

Finally, our data with infectious DENV immune complexes are consistent with the notion of “two-point” attachment of antibody-coated DENV that involves both the FcγR and a putative virus receptor. Ligand-clustered Fc receptors, including FcγRIIA (Kwiatkowska and Sobota, 2001), concentrate in cell membrane regions, (e.g. lipid rafts) rich in signaling molecules and potential virus receptor engagement sites. We speculate that the relatively weak DENV immune complex binding to FcγRIIA (independent of the IgG subclass) and fast off-rate (Maenaka et al., 2001) lead to a virus receptor-mediated entry pathway that favors virion infectivity, whereas DENV immune complexes comprised of IgG subclasses that are relatively tightly bound to FcγRIA/γ (i.e. IgG1, IgG3, and IgG4) are co-internalized upon cross-linking, and are then directed to a virus-destructive intracellular pathway. DENV immune complexes comprised of IgG2 antibody are exceptional as they weakly bind FcγRIA and thus, likely utilize the same internalization pathway available to FcγRIIA-bound DENV. Failure of low-affinity IgG2-DENV immune complexes to efficiently cross-link FcγRIA/γ and trigger signaling may also contribute to the divergent neutralization effect. Since IgG1 is more abundant than IgG2 in human serum, it seems possible that irrelevant IgG1 antibodies could modulate the FcγRIA influence on IgG2 DENV neutralizing antibodies in vivo.

In conclusion, our findings point to a high level of complexity in the interplay between antibody-coated virion, FcγR, and virus receptor, one in which antibody isotype and FcγR independently and interdependently modulate functional outcome. The mechanisms involved are likely shared among disparate viruses, but are also likely to involve aspects that are unique to a particular virus and host cell type.

Materials and methods

Cells and viruses

Vero cells and C6/36 Aedes albopictus mosquito cells were grown in minimum essential medium; THP-1 cells were grown in RPMI 1640 medium. All media were supplemented with heat-inactivated (1 hr at 56°C) fetal bovine serum (HyClone, Logan, UT). DENV1 (16007) and DENV2 (16681), (Dr. Richard Kinney CDC, Ft. Collins, CO) were propagated from reference stock by a single passage in mosquito cells and titered by plaque assay in Vero cells.

Preparation of FcγR-expressing CV-1 cells

A bicistronic expression cassette in a pcDNA5/FRT backbone containing the human γ chain and FcγRIA coding sequences has been previously described (Rodrigo et al., 2006). Human FcγRIIA (H131 and R131 allotypes) genes were individually generated in the same vector. Construct sequences were verified by DNA sequence analysis. A flp recombinase-mediated integration system (“Flp-In System”, Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA) was used to engineer the respective FcγR or a control empty vector into CV-1 cells bearing a single, fixed chromosomal recombination “FRT” site (CV-1/FRT) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Gene integration was verified by PCR amplification and DNA sequencing.

Cell surface FcγRIA and FcγRIIA were detected and quantified as previously described (Rodrigo et al., 2006). Briefly, THP-1 cells or control and CV-1/FcγR transfectants were stained with R-Phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated IgG1 mAbs against human FcγRIA (CD64 mAb 10.1; eBioscences, San Diego, CA) or FcγRIIA (CD32 H/R131, mAb AT10, Serotec, Raleigh, NC) using a PE-labeled mouse IgG1 isotype control from the corresponding manufacturer. Stained cells were analyzed by FACSCalibur using CellQuest software (BD Immunocytometry Systems, Franklin Lakes, NJ). The number of FcγRIA or FcγRIIA molecules expressed on the surface of the CV-1 transfectants was determined by a quantitative immunofluorescence method that employed standardized QuantiBRITE-PE beads (BD Pharmingen, San Jose, CA).

IgG subclass binding specificity of FcγR-expressing CV-1 cells

IgG opsonized sheep red blood cells (SRBC) binding to FcγR transfectants was measured as previously described (Rodrigo et al., 2006). For competition binding assays, CV-1 transfectant suspensions were treated with heat-aggregated purified human IgG1, IgG2, or IgG3 myeloma proteins (Dr. Clark Anderson, OSU, Columbus OH) or human serum albumin (Anderson and Abraham, 1980) followed by mixing with opsonized SRBC and counting. The percentage of inhibition of rosette formation (%I) was calculated by: %I = (% rosettes in untreated cells) - (% rosetting IgG myeloma protein-treated cells) ÷ (% rosetting in untreated cells) × 100.

Chimeric mouse-human and chimpanzee-human DENV mAbs

Properties of humanized mouse or chimpanzee anti-DENV mAbs used to prepare DENV ICs are summarized in Table 1. Construction and characteristics of full-length humanized chimpanzee IgG mAb 1A5 variants have been previously described (Goncalvez et al., 2007; Goncalvez et al., 2004). Chimeric mouse-human mAbs with human heavy chains were generated as follows: Briefly, DV1 E50 (DENV subcomplex-specific) and WNV E60 (flavivirus cross-reactive) heavy and light chain RNA were isolated from hybridoma cells after guanidinium thiocyanate and phenol-chloroform extraction, and converted to cDNA by reverse transcription. The VH and VL segments were amplified by PCR using the 5′ RACE system as described (Oliphant et al., 2005). The RACE products were inserted into the plasmid pCR2.1-TOPO using the TopoTA kit (Invitrogen). The resulting plasmids were then subjected to DNA sequencing to determine the VH and VL sequences for DV1-E50 and WNV-E60. The cDNA sequences were transcribed and the predicted amino acid sequence determined. From these sequences the framework (FR) and CDR regions were identified as defined by Kabat et al (1991). The mouse VH was joined to individual human C-γ constant regions and an Ig leader sequence, and inserted into pCI-neo for mammalian expression. The mouse VL was joined to a human Cκ segment and an Ig leader sequence and also cloned into pCI-neo for mammalian expression of chimeric DV1-E50 or WNV-E60. The resulting plasmids were co-transfected into human 293T cells using Lipofectamine-2000 and the chimerized antibodies with different human heavy chains were recovered from the resulting conditioned medium and purified by protein A or G, and size exclusion chromatography. Human chimeric or full-length humanized chimpanzee mAbs were used in affinity-purified form in PBS. Purified antibody concentrations were determined using a Bio-RAD DC protein assay kit (Bio-RAD Laboratories, Hercules, CA) and by UV spectrophotometry. Purified human IgG (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was used as a standard.

DENV mAb virion binding assay

A previously described enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) method was modified to measure humanized mAb binding to DENV virion (Goncalvez, Purcell, and Lai, 2004). Briefly, DENV1 or DENV2 virions (1 × 105 PFU/well) from mosquito cell cultures were bound to C-bottom ELISA plates pre-coated with an affinity-purified flavivirus cross-reactive mAb (7E1) prepared against DENV2 (J. J. Schlesinger, unpublished). MAb binding curves were generated with GraphPad Prism5 software from triplicate wells stained with an alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-human IgG antibody (Southern Biotechnology Associates, Inc., Birmingham, AL).

Measurement of DENV neutralization by immunofocus plaque reduction assay

FBS used in the neutralization assays was heat-inactivated at 56°C for 1 hr. Pre-formed DENV immune complexes were prepared by incubating 200 plaque forming units (PFU) of DENV with specified antibody concentrations for 60 min at 37°C. DENV in free form or as immune complexes were adsorbed (200 ul per well) to cell monolayers (2 × 105 cells per well) in 24-well polystyrene cluster plates by incubation for 90 minutes at 37°C followed by aspiration of supernatant and overlaying with 0.6% agarose (SeaKem GTG, FMC BioProducts, Rockland, Me) in MEM with 10% FBS. For competition experiments, purified control HSA or IgG myeloma proteins were mixed with DENV immune complexes before addition to established CV-1 cell monolayers. After overnight incubation at 37°C the newly established cell monolayers were washed with PBS and overlaid with agarose. DENV plaques were immunostained and counted as previously described (Rodrigo et al., 2006). GraphPad Prism5 software was used to generate neutralization dose-response curves by sigmoidal curve-fit and to calculate 50% plaque reduction neutralization test (PRNT50) end-point titers by probit analysis (Russell et al., 1967).

Acknowledgments

We thank Lihua Rong and Danielle Alcena for expert technical assistance. The work was funded by grants from the Pediatric Dengue Vaccine Initiative of the International Vaccine Institute (TR 03/04 to J.J.S.; TR16 to X.J.) and the NIH (R01 AI073755 and U01AI77955) to M.S.D.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Anderson CL, Abraham GN. Characterization of the Fc receptor for IgG on a human macrophage cell line, U937. J Immunol. 1980;125(6):2735–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armour KL, Clark MR, Hadley AG, Williamson LM. Recombinant human IgG molecules lacking Fcgamma receptor I binding and monocyte triggering activities. Eur J Immunol. 1999;29(8):2613–24. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199908)29:08<2613::AID-IMMU2613>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armour KL, van de Winkel JG, Williamson LM, Clark MR. Differential binding to human FcgammaRIIa and FcgammaRIIb receptors by human IgG wildtype and mutant antibodies. Mol Immunol. 2003;40(9):585–93. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2003.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boonnak K, Slike BM, Burgess TH, Mason RM, Wu SJ, Sun P, Porter K, Rudiman IF, Yuwono D, Puthavathana P, Marovich MA. Role of dendritic cells in antibody-dependent enhancement of dengue virus infection. J Virol. 2008;82(8):3939–51. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02484-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruhns P, Iannascoli B, England P, Mancardi DA, Fernandez N, Jorieux S, Daeron M. Specificity and affinity of human Fcgamma receptors and their polymorphic variants for human IgG subclasses. Blood. 2009;113(16):3716–25. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-09-179754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavacini LA, Emes CL, Power J, Desharnais FD, Duval M, Montefiori D, Posner MR. Influence of heavy chain constant regions on antigen binding and HIV-1 neutralization by a human monoclonal antibody. J Immunol. 1995;155(7):3638–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dam TK, Torres M, Brewer CF, Casadevall A. Isothermal titration calorimetry reveals differential binding thermodynamics of variable region-identical antibodies differing in constant region for a univalent ligand. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(46):31366–70. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806473200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabat EA, W T, Perry HM, Gottesman KS, Foeller C. Sequences of Proteins of Immunological Interest. In: Kabat EA, Wu TT, Perry H, Gottesman K, Foeller C, editors. NIH Publication No 91-3242. US Department of Health and Human Services; Bethesda, MD: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Fleit HB, Kobasiuk CD. The human monocyte-like cell line THP-1 expresses Fc gamma RI and Fc gamma RII. J Leukoc Biol. 1991;49(6):556–65. doi: 10.1002/jlb.49.6.556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goncalvez AP, Engle RE, St Claire M, Purcell RH, Lai CJ. Monoclonal antibody-mediated enhancement of dengue virus infection in vitro and in vivo and strategies for prevention. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(22):9422–9427. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703498104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goncalvez AP, Men R, Wernly C, Purcell RH, Lai CJ. Chimpanzee Fab fragments and a derived humanized immunoglobulin G1 antibody that efficiently cross-neutralize dengue type 1 and type 2 viruses. J Virol. 2004;78(23):12910–8. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.23.12910-12918.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goncalvez AP, Purcell RH, Lai CJ. Epitope determinants of a chimpanzee Fab antibody that efficiently cross-neutralizes dengue type 1 and type 2 viruses map to inside and in close proximity to fusion loop of the dengue type 2 virus envelope glycoprotein. J Virol. 2004;78(23):12919–28. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.23.12919-12928.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halstead SB. Neutralization and antibody-dependent enhancement of dengue viruses. Adv Virus Res. 2003;60:421–67. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3527(03)60011-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kou Z, Quinn M, Chen H, Rodrigo WW, Rose RC, Schlesinger JJ, Jin X. Monocytes, but not T or B cells, are the principal target cells for dengue virus (DV) infection among human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J Med Virol. 2008;80(1):134–46. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwiatkowska K, Sobota A. The clustered Fcgamma receptor II is recruited to Lyn-containing membrane domains and undergoes phosphorylation in a cholesterol-dependent manner. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31(4):989–98. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200104)31:4<989::aid-immu989>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littaua R, Kurane I, Ennis FA. Human IgG Fc receptor II mediates antibody-dependent enhancement of dengue virus infection. J Immunol. 1990;144(8):3183–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F, Bergami PL, Duval M, Kuhrt D, Posner M, Cavacini L. Expression and functional activity of isotype and subclass switched human monoclonal antibody reactive with the base of the V3 loop of HIV-1 gp120. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2003;19(7):597–607. doi: 10.1089/088922203322230969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mady BJ, Erbe DV, Kurane I, Fanger MW, Ennis FA. Antibody-dependent enhancement of dengue virus infection mediated by bispecific antibodies against cell surface molecules other than Fc gamma receptors. J Immunol. 1991;147(9):3139–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maenaka K, van der Merwe PA, Stuart DI, Jones EY, Sondermann P. The human low affinity Fcgamma receptors IIa, IIb, and III bind IgG with fast kinetics and distinct thermodynamic properties. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(48):44898–904. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106819200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nimmerjahn F, Ravetch JV. Fcgamma receptors as regulators of immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8(1):34–47. doi: 10.1038/nri2206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliphant T, Engle M, Nybakken GE, Doane C, Johnson S, Huang L, Gorlatov S, Mehlhop E, Marri A, Chung KM, Ebel GD, Kramer LD, Fremont DH, Diamond MS. Development of a humanized monoclonal antibody with therapeutic potential against West Nile virus. Nat Med. 2005;11(5):522–30. doi: 10.1038/nm1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliphant T, Nybakken GE, Engle M, Xu Q, Nelson CA, Sukupolvi-Petty S, Marri A, Lachmi BE, Olshevsky U, Fremont DH, Pierson TC, Diamond MS. Antibody recognition and neutralization determinants on domains I and II of West Nile Virus envelope protein. J Virol. 2006;80(24):12149–59. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01732-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez LG, Costa MR, Todd CA, Haynes BF, Montefiori DC. Utilization of immunoglobulin G Fc receptors by human immunodeficiency virus type 1: a specific role for antibodies against the membrane-proximal external region of gp41. J Virol. 2009;83(15):7397–410. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00656-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierson TC, Fremont DH, Kuhn RJ, Diamond MS. Structural insights into the mechanisms of antibody-mediated neutralization of flavivirus infection: implications for vaccine development. Cell Host Microbe. 2008;4(3):229–38. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigo WW, Jin X, Blackley SD, Rose RC, Schlesinger JJ. Differential enhancement of dengue virus immune complex infectivity mediated by signaling-competent and signaling-incompetent human Fcgamma RIA (CD64) or FcgammaRIIA (CD32) J Virol. 2006;80(20):10128–38. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00792-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell PK, Nisalak A, Sukhavachana P, Vivona S. A plaque reduction test for dengue virus neutralizing antibodies. J Immunol. 1967;99(2):285–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharf O, Golding H, King LR, Eller N, Frazier D, Golding B, Scott DE. Immunoglobulin G3 from polyclonal human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) immune globulin is more potent than other subclasses in neutralizing HIV type 1. J Virol. 2001;75(14):6558–65. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.14.6558-6565.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres M, Casadevall A. The immunoglobulin constant region contributes to affinity and specificity. Trends Immunol. 2008;29(2):91–7. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres M, Fernandez-Fuentes N, Fiser A, Casadevall A. Exchanging murine and human immunoglobulin constant chains affects the kinetics and thermodynamics of antigen binding and chimeric antibody autoreactivity. PLoS One. 2007;2(12):e1310. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanaveeradej V, Endy TP, Samakoses R, Kerdpanich A, Simasathien S, Polprasert N, Aree C, Vaughn DW, Ho C, Nisalak A. Transplacentally transferred maternal-infant antibodies to dengue virus. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2003;69(2):123–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]