Abstract

This study examined the effects of diagnosis (functional versus organic), physician practice orientation (biomedical versus biopsychosocial), and maternal trait anxiety (high versus low) on mothers’ responses to a child’s medical evaluation for chronic abdominal pain. Mothers selected for high (n = 80) and low (n = 80) trait anxiety imagined that they were the mother of a child with chronic abdominal pain described in a vignette. They completed questionnaires assessing their negative affect and pain catastrophizing. Next, mothers were randomly assigned to view one of four video vignettes of a physician actor reporting results of the child’s medical evaluation. Vignettes varied by diagnosis (functional versus organic) and physician practice orientation (biomedical versus biopsychosocial). Following presentation of the vignettes, baseline questionnaires were re-administered and mothers rated their satisfaction with the physician. Results indicated that mothers in all conditions reported reduced distress pre- to post-vignette; however, the degree of the reduction differed as a function of diagnosis, presentation, and anxiety. Mothers reported more post-vignette negative affect, pain catastrophizing, and dissatisfaction with the physician when the physician presented a functional rather than an organic diagnosis. These effects were significantly greater for mothers with high trait anxiety who received a functional diagnosis presented by a physician with a biomedical orientation than for mothers in any other condition. Anxious mothers of children evaluated for chronic abdominal pain may be less distressed and more satisfied when a functional diagnosis is delivered by a physician with a biopsychosocial rather than a biomedical orientation.

Keywords: chronic abdominal pain, biopsychosocial, trait anxiety, medically unexplained symptoms, patient satisfaction, catastrophizing

Functional symptoms, defined as symptoms without identifiable organic etiology, account for a high proportion of primary care and subspecialty visits [29]. Pediatric patients with functional symptoms experience high levels of disability and psychological distress [8] that may continue into adulthood [43]. When the medical evaluation yields no evidence of disease, parents may be distressed by uncertainty regarding the cause of their children’s symptoms [9, 10]. For example, parents of youth with chronic abdominal pain—a common pediatric symptom rarely associated with organic disease [8, 43]—have reported helplessness, worry, and dissatisfaction with the medical evaluation [41]. When the medical encounter and communication with the provider do not meet parents’ expectations, their distress may increase [40]. Parent and provider characteristics that influence parents’ responses to a functional diagnosis for their children’s pain have not been described.

Physicians vary considerably in the extent to which their practice reflects a biomedical versus biopsychosocial orientation. Depending on their orientation, some physicians may be more effective than others in communicating with parents about a functional diagnosis [15]. Physicians with a biomedical approach focus on identification of physical pathology and treatment of disease, whereas those with a biopsychosocial approach investigate both biological and psychosocial factors that contribute to illness [15, 16]. Thus, when a child’s medical evaluation indicates no evidence of disease, the physician with a biomedical orientation typically reassures the family regarding the absence of disease and may refer the child to psychiatry, with the implication that the symptoms are not “real”. The physician with a biopsychosocial orientation, in contrast, not only reassures parents regarding the absence of physical pathology, but also gives a psychophysiological explanation of functional symptoms and may suggest lifestyle interventions that enhance parents’ perceived control of their children’s symptoms [15, 16]. The biopsychosocial approach has been advocated for the treatment of functional symptoms [15, 18, 20, 23, 28], but it is not known whether a biopsychosocial approach is superior to a biomedical approach in alleviating parents’ distress about their children’s symptoms.

Parents’ personality characteristics also may influence their responses to children’s medical evaluations. People with high trait anxiety—defined as the stable tendency to worry and be apprehensive [5]—tend to interpret ambiguous stimuli as more threatening than people with low trait anxiety [5, 19, 36, 46]. In Western medicine, a functional diagnosis is an ambiguous stimulus that indicates the absence of identifiable disease. Thus, people with high trait anxiety may find a functional diagnosis particularly distressing.

This study used an experimental design to examine whether mothers’ responses to a child’s medical evaluation for chronic abdominal pain differed by functional versus organic diagnosis, biomedical versus biopsychosocial physician orientation, and high versus low trait anxiety. We assessed mothers’ negative affect, catastrophizing, and satisfaction with the physician because the literature suggests that these are important aspects of parental responses to pediatric medical encounters [41].

Methods

Study Design and Hypotheses

In an experimental design utilizing vignettes, we presented mothers with a vignette of a child with chronic abdominal pain, followed by a video vignette of a physician presenting the results of the child’s medical evaluation. We tested the following hypotheses:

We expected a main effect of diagnosis; compared to an organic diagnosis for the child’s pain, a functional diagnosis will be associated with higher levels of maternal negative affect, catastrophizing about the child’s pain, and lower satisfaction with the physician.

The effect of diagnosis will be moderated by physician practice orientation (biomedical versus biopsychosocial). Specifically, we expected that the negative impact of a functional diagnosis would be greater for mothers who received information from a physician with a biomedical orientation compared to mothers who received a functional diagnosis delivered by a physician with a biopsychosocial orientation.

The effect of diagnosis will be moderated by maternal trait anxiety (high versus low). We predicted that the negative impact of a functional diagnosis for the child’s abdominal pain would be greater for mothers with high trait anxiety compared to mothers with low trait anxiety.

Finally, we expected a three-way interaction effect in which mothers with high trait anxiety who received a functional diagnosis from a physician with a biomedical orientation would demonstrate significantly more negative affect, pain catastrophizing, and significantly less satisfaction with the physician compared to mothers in all other conditions.

Recruitment and Screening

Mothers were invited to participate in eligibility screening by a mass email advertisement sent through the University’s email system to all employees with an email address at the medical center. In the email, mothers of children ages 8 to 17 were invited to participate in an online survey about mothers’ beliefs about children’s health. Mothers were selected for participation because they are more likely than fathers to accompany their children to a medical clinic. Mothers were selected without regard to the status of their own children’s history of abdominal pain or chronic illness. They provided information about their own children’s health so that we could examine whether this variable influenced their responses in the study. Interested persons contacted the study coordinators and were sent an email with a link to a consent form and the online screening survey, which consisted of demographic information and the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) [37]. Mothers completed the consent form and survey online. The screening survey was constructed so that no questions could be skipped, items could only be marked with one answer, and no changes could be made after submission. Responses were recorded through an online survey collection system. Participants’ names were entered into a drawing upon completion of the screening; one in every 25 participants won a $25 gift certificate as a thank-you for participation.

To maximize our ability to detect an effect of trait anxiety, mothers were selected for study participation only if they had high (score ≥ 40) or low (score ≤ 30) trait anxiety, defined as scores that were one-half of a standard deviation above or below the mean of published norms for adult women on the STAI (Published M = 34.79, SD = 9.22) [37]. The STAI is a self-report scale consisting of 20 items that measure dispositional response to psychological stress. Participants rate how they generally feel on a four-point scale with responses ranging from “almost never” (coded “1”) to “almost always” (coded “4”). Responses are summed to create total scores that can range from 20 to 80. Alpha reliability was excellent at .91.

Of the 393 interested mothers who responded to the email advertisement, 348 participated (88%), 19 (5%) did not respond, 11 (3%) submitted incomplete surveys, and 15 (4%) declined. STAI scores for the 348 participants were consistent with published STAI norms; M = 34.90, SD = 9.31. Participants were divided into high, low, and mid level anxiety groups using the selection criteria described above to determine study eligibility. Participants scoring in the high anxiety tier (n = 100) and low anxiety tier (n = 128) were eligible for study participation and were contacted with a second email inviting them to participate in the study. The remaining participants who scored in the mid anxiety tier (n = 120) were not contacted further.

Procedure

Eligible mothers (i.e., those mothers with high and low trait anxiety scores on the screening test) were invited by email to participate in an online study to learn more about how mothers think about their children’s health before and after medical evaluations. Of the 228 mothers invited, 160 (70%) participated, 34 (15%) were interested but did not complete the study within the allotted timeframe, 21 (9%) did not respond to the study invitation, 11 (5%) were unable to be contacted, and 2 (1%) declined. An equal number of mothers from the high and low anxiety groups participated in accordance with the trait anxiety selection criteria; n = 80 in each group. Participants from the high and low anxiety groups were recruited until 80 in each group had completed the study; the remaining interested participants were informed that the study had ended and were thanked for their interest.

Mothers who responded to the study invitation were randomly assigned to one of four physician vignette conditions and sent an email with a link to the online study, including a link to view the physician vignette video pertaining to their condition. Mothers read the child vignette, completed baseline questionnaires, viewed the physician vignette pertaining to their randomly assigned physician condition, and finally completed questionnaires, physician satisfaction and vignette validity ratings, and demographic measures. The study was constructed so that no questions could be skipped, items could be marked with only one answer, and no changes could be made after survey submission. Less than one percent of participants contacted study personnel with questions about the study or problems with the online survey system. Mothers received $10 for their participation after they submitted their responses.

Vignettes

Child vignette

To experimentally control for child characteristics, we developed a written vignette describing a child with chronic abdominal pain and pain-related disability. The use of vignettes in this manner is a scientifically rigorous way of setting up a hypothetical situation that controls study conditions and provides information for future naturalistic testing of similar constructs [e.g., 26]. Abdominal pain was chosen as the presenting complaint because of its high prevalence among children and adolescents [1, 6] and because medical evaluation can yield either a functional or an organic diagnosis [21]. An 11-year-old female was described in the vignette to represent the mean age and higher proportion of females among abdominal pain patients [1, 2]. Empirical research on the correlates of chronic abdominal pain and the medical evaluation for chronic abdominal pain informed the content of the vignette [e.g., 6, 43]. Mothers read the vignette and were told to imagine that the child was their own as they completed study measures. The full text of the child vignette is below:

Imagine you are the mother of an 11-year-old girl. Your daughter has been having stomach aches off and on for several years. She has stomach aches two to three times a week and the pain lasts for at least an hour or more each time. Recently, the stomach aches have been getting worse, becoming even more painful and frequent than ever. Sometimes she cries and doubles over in pain. Your daughter has to stay home from school once or twice a week because of the pain. She has missed two weeks of school already this semester. You can tell that your daughter’s pain is really severe. It is keeping her from doing a lot of things she used to do. You’ve taken her to your primary care physician’s office several times, but they have not been able to determine what’s causing this pain. The doctors haven’t found anything to help relieve her pain. Now, imagine that you are the mother of this child who has been having pain on and off for the last several years, which has become even more severe in the past couple of weeks. You are going to fill out a set of questionnaires. Please answer the questions as if you are the mother of this child with abdominal pain.

Physician vignettes

The vignettes of a physician presenting results of the child’s medical evaluation were presented through video to make the vignettes as realistic and engaging as possible. A male actor (who was a physician experienced in treatment of chronic abdominal pain) was selected for the physician vignette because 73% of pediatric gastroenterologists practicing in this specialty area are male [33]. Gastritis was chosen to represent the organic diagnosis and functional abdominal pain was chosen as the functional diagnosis, because they are common in the differential diagnosis of children with chronic abdominal pain.

The four physician vignettes varied by diagnosis (organic versus functional) and physician orientation style (biomedical versus biopsychosocial). Mothers were randomly assigned to one of the four physician vignette conditions until each vignette was viewed by 20 mothers with high trait anxiety and 20 mothers with low trait anxiety.

The content of the physician vignettes was informed by several sources. We consulted the literature on the components of illness representations regarding the nature of information that parents would expect to receive from a physician regarding their child’s abdominal pain [e.g., 30]. These components—illness identity, consequences, timeline, cause, and treatment—were included in each vignette. We consulted literature on the clinical application of the biomedical and biopsychosocial models to identify how a physician with an orientation to each model would be likely to address these illness components in presenting results of a child’s medical evaluation for abdominal pain [15, 17].

According to the prototypical biomedical model, organic disease causes illness, illness can be attributed to a single underlying cause, disease causes symptoms, and treatment focuses on removal of the organic disease [15, 16, 42]. When an organic etiology is identified, physicians practicing in the biomedical model label the disease, explain how the disease is related to symptoms, and prescribe a medical treatment for the disease. When no organic etiology is identified, physicians practicing in the biomedical model typically report that organic disease has been ruled out, label the patient as healthy, offer reassurance, and may suggest referral to a mental health provider if symptoms persist. In contrast, physicians practicing in the biopsychosocial model may make a positive diagnosis of a functional disorder, refer to biological, psychological, and social contributions to illness, and recommend a treatment plan that addresses multiple non-disease factors that contribute to the patient’s symptoms [15, 17, 23, 31, 42]. If an organic etiology for illness is found, physicians practicing in the biopsychosocial model do not necessarily limit their treatment to medical interventions but also may suggest psychosocial interventions, such as pain coping strategies, that may help alleviate symptoms.

Four physician vignettes were developed and filmed for the study: organic biopsychosocial, organic biomedical, functional biopsychosocial, and functional biomedical. Each vignette had six components. First, the physician presented results of the medical evaluation, which differed for the organic condition (“mild inflammation in some of the cells of her stomach”) and the functional condition (“no evidence of any disease or any other abnormality”) but was identical within biomedical versus biopsychosocial practice orientation conditions. Subsequent information varied across the four physician vignette conditions for the remaining five components: diagnosis, explanation of the cause of the pain, treatment recommendation, prognosis and follow-up, and guidance regarding the child’s school attendance.

Each of these five sections was introduced by a black screen with a question presented in white text. Participants were alerted that these questions would be presented between sections and were asked to read them as if they were asking that question of the physician. The questions represented components of illness representation that had been identified by physicians interviewed for the study that are frequently asked by parents:

“What is her diagnosis?”

“Why is she having such severe pain?”

“What can you do for her?”

“What if she keeps having pain?”

“Can she go to school?”

Participants were asked to read each question aloud in order to simulate the dialogue that typically occurs between physicians and parents during children’s medical visits and to increase participants’ engagement in the study.

Word counts and video playing time of the vignettes were similar across conditions (see Appendix). Drafts of the vignettes were reviewed by pediatric pain physicians and pediatric gastroenterologists; their feedback guided revision of the vignettes. Finally, the physician actor (who was the same in each vignette) modified the language of the vignettes to make it more conversational and consistent with his speaking style.

Measures

After reading the child vignette, mothers completed measures describing how they would think and feel if they were the mother of the child described in the vignette. For each of these measures, they were asked to rate what their thoughts and feelings would be “right now … imagining you are the mother of the child you just heard about.” They completed the same measures again after viewing one of the four physician vignettes in which results of the child’s medical evaluation were presented. Finally, mothers completed ratings of satisfaction with the physician in the vignette, physician vignette validity, and demographics.

Negative Affect

Mothers’ negative affect was assessed with the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) [45]. The PANAS is a widely used, validated, and reliable measure of affect in adults [13, 45]. The measure is comprised of two 10-item scales for negative and positive affect; only the negative affect (NA) scale was used in this study. Participants responded on a 5-point numerical scale ranging from “very slightly or not at all” (coded “0”) to “extremely” (coded “4”). Item ratings are summed and a mean is obtained that can range from 0 to 4. High scores correspond to high levels of negative affect. Alpha reliability was excellent; .91 at baseline and .94 after viewing the physician vignette.

Pain Catastrophizing

Mothers’ catastrophic thinking about children’s pain was assessed with the parent version of the Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS-P) [25]. The PCS-P is a 13-item self-report measure that assesses parents’ perceptions of children’s pain related to three dimensions of catastrophizing; magnification (“I become afraid that my child’s pain may get worse”), rumination (“I can’t seem to keep it out of my mind”), and helplessness (“I feel I can’t go on”). Participants responded on a 5-point scale ranging from “not at all” (coded as “0”) to “all the time” (coded as “4”). Items were summed and averaged, producing a total mean score than can range from 0 to 4. High scores are associated with high levels of pain catastrophizing. Alpha reliability was excellent; .92 at baseline and .93 after viewing the physician vignette.

Satisfaction with the physician

A three-item questionnaire was created to assess mothers’ satisfaction with the physician after viewing the physician vignette. Questions were derived from a review of the literature on parents’ satisfaction with pediatric providers in the outpatient setting and items were selected that made sense in the context of the medical evaluation vignette utilized in the current study [e.g., 35]. Participants rated the degree to which they found the physician effective at communicating, competent, and concerned on a five-point scale ranging from “not at all” (coded as “0”) to “extremely” (coded as “4”). Responses were summed and averaged to yield a total mean score that could range from 0 to 4. Items were worded so that high scores reflect more satisfaction. Alpha reliability was good at .86.

Validity of physician vignettes

Validity of the physician vignettes was evaluated by asking participants to respond the question, “How realistic was the physician vignette?” Participants rated their responses on a five-point scale ranging from “not at all” (coded “0”) to “extremely” (coded “4”).

Demographics

Mothers completed a demographic questionnaire regarding employment, education, age, ethnicity, number of children, and information about their children’s health, including any chronic medical conditions and gastrointestinal (GI) disorders.

Analytic Strategy

First, univariate analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were conducted to test for differences between the four physician vignette conditions on participant demographics and scores on baseline measures. Second, paired t-tests examined the effects of time on dependent variables assessed before and after viewing the physician vignette. Third, univariate analyses of covariance (ANCOVAs) examined the effects of diagnosis, physician orientation, and maternal trait anxiety on measures of mothers’ negative affect and pain catastrophizing, controlling for mothers’ baseline scores on all measures1. Finally, univariate ANOVAs examined the effects of diagnosis, physician orientation, and maternal trait anxiety on mothers’ satisfaction with the physician.

For all analyses, effect sizes were calculated for significant main and interaction effects and interpreted with Cohen’s [12] definition for small (d = .2), medium (d = .5), and large effect sizes (d = .8). Except for the paired t-test analyses of the effect of time, all reported means for negative affect and pain catastrophizing were baseline corrected by using the baseline measures as covariates.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Demographic variables

Mothers ranged in age from 26 to 56 years (M = 41.42; SD = 6.84) and had 1 to 5 children (M = 2.18; SD = .92). Distribution of participants by ethnicity was 77% Caucasian, 16% African-American, and 7% other. All mothers had at least a high school education; in addition, 36% had some college or a technical degree, 34% had a college degree, and 24% had a graduate degree. One quarter of the sample had a child with a chronic condition; asthma was the most frequent response (n = 25). Of mothers of children with a chronic condition, two-thirds described the condition as mild. One quarter of participants had a child with a GI condition; irritable bowel syndrome (n = 12) and reflux (n = 12) were the most frequent responses.

ANOVAs and chi-square analyses were performed to test for differences in demographic variables between participants who were randomly assigned to the four physician vignette conditions. There were no significant differences between participants in demographic variables between physician vignette conditions. Multivariate ANOVAs were performed between chronic and GI condition variables and study variables to assess their relation prior to data analysis. There was no significant relation of mothers’ having a child with a chronic and/or GI condition and their negative affect and pain catastrophizing responses in the study.

Baseline analyses

Scores on baseline measures did not differ significantly across physician vignette conditions, indicating that mothers in the four conditions did not differ on negative affect or pain catastrophizing prior to viewing the physician vignettes.

Time analyses

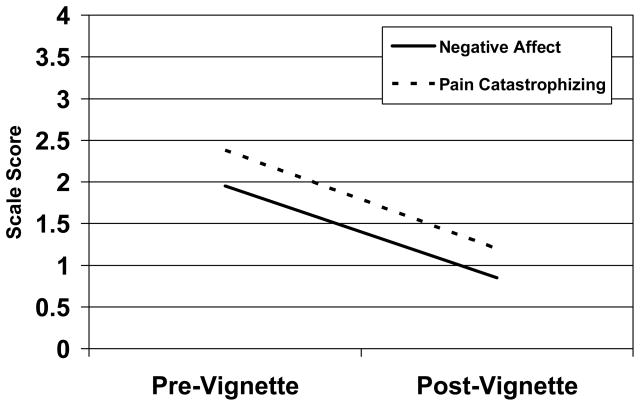

Time had a significant effect on all measures assessed before and after viewing the physician vignette. Significant decreases were observed on measures of mothers’ negative affect, t (159) = 15.71, p < .001, and pain catastrophizing, t (159) = 19.98, p < .001. These data are presented in Figure 1. Effect sizes for time were large; negative affect d = 1.25 and pain catastrophizing d = 1.45. These time effects were qualified by the effects of diagnosis, physician practice orientation, and maternal trait anxiety, as described in the next section.

Figure 1.

Mothers’ Mean Scores on Pain Catastrophizing and Negative Affect Before and After Viewing the Physician Vignette.

Validity of physician vignette

More than 50% of participants described the physician vignette as “extremely” realistic (M = 3.34, SD = .82, Observed Range = 1 – 4); no participant rated the vignette as “not at all” realistic. The effect of participants’ experience caring for children with chronic and/or GI conditions on their vignette validity rating was examined. Results of analyses were non-significant, indicating that mothers of children with a chronic illness did not differ in their vignette validity rating from mothers of well children.

Main and moderating effects of anxiety, diagnosis, and presentation on vignette validity were examined with a univariate ANOVA. A main effect of diagnosis, F (1, 147) = 9.17, p < .01, indicated that mothers in the organic diagnosis condition rated the vignette as significantly more realistic (M = 3.53, SE = .09) than mothers in the functional diagnosis condition (M = 3.14, SE = .09). This was a medium effect size of d = .50. This was the only reliable effect on vignette validity.

Tests of Primary Hypotheses

ANCOVAs were conducted for measures of negative affect and pain catastrophizing assessed after viewing the physician vignette, with the baseline scores on these measures (assessed after reading the child vignette but prior to viewing the physician vignette) entered as a covariate. Adjusted means and standard errors that control for baseline values are presented in the text and figures. Univariate ANOVAS were performed to test main and moderating effects of diagnosis, physician orientation, and maternal trait anxiety on participants’ ratings of satisfaction with the physician. Full tables of means for dependent variables are presented in Table 1 (negative affect) and Table 2 (pain catastrophizing); means for ratings of satisfaction with the physician are presented in the text.

Table 1.

Tables of Means for Negative Affect by Time, Anxiety Group, and Physician Vignette Condition.

| Groups | Pre-Physician Vignette | Post-Physician Vignette | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High Anxiety | Mean | SD | Mean | SD |

| Organic Biopsychosocial | 1.99 | .91 | .80 | .62 |

| Organic Biomedical | 2.33 | .98 | .60 | .75 |

| Functional Biopsychosocial | 2.17 | .88 | 1.05 | .97 |

| Functional Biomedical | 2.22 | .92 | 1.80* | 1.00* |

| Low Anxiety | Mean | SD | Mean | SD |

| Organic Biopsychosocial | 1.70 | .85 | .50 | .64 |

| Organic Biomedical | 1.35 | .76 | .34 | .42 |

| Functional Biopsychosocial | 2.14 | .95 | .83 | .63 |

| Functional Biomedical | 1.72 | .74 | .88 | .93 |

Significant three-way interaction of diagnosis, physician practice orientation, and maternal trait anxiety.

Table 2.

Table of Means for Pain Catastrophizing by Time, Anxiety Group, and Physician Vignette Condition.

| Groups | Pre-Physician Vignette | Post-Physician Vignette | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High Anxiety | Mean | SD | Mean | SD |

| Organic Biopsychosocial | 2.37 | .89 | 1.20 | .59 |

| Organic Biomedical | 2.62 | .97 | 1.00 | .73 |

| Functional Biopsychosocial | 2.56 | .78 | 1.43 | .77 |

| Functional Biomedical | 2.41 | .66 | 1.86* | .90* |

| Low Anxiety | Mean | SD | Mean | SD |

| Organic Biopsychosocial | 2.32 | .89 | .84 | .79 |

| Organic Biomedical | 1.87 | .68 | .74 | .66 |

| Functional Biopsychosocial | 2.53 | .77 | 1.30 | .78 |

| Functional Biomedical | 2.31 | .74 | 1.22 | .79 |

Significant three-way interaction of diagnosis, physician practice orientation, and maternal trait anxiety.

Negative Affect and Pain Catastrophizing

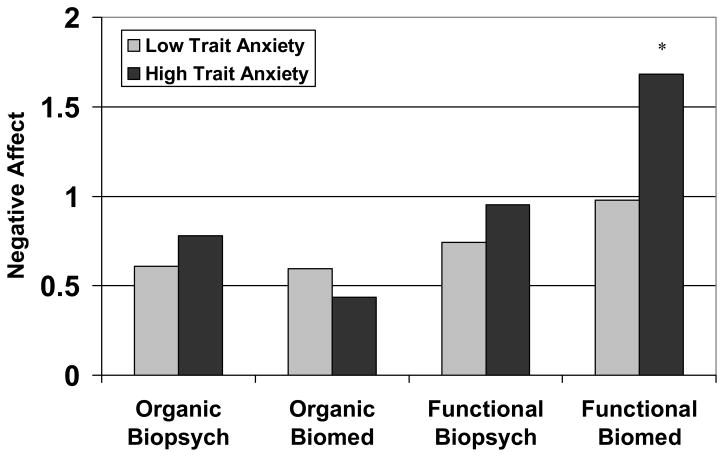

In accordance with study hypotheses, maternal trait anxiety, physician orientation, and type of diagnosis all interacted to moderate mothers’ negative affect, F (1, 151) = 3.82, p = .05 and pain catastrophizing, F (1, 151) = 6.33, p < .05, following presentation of results of the medical evaluation. As predicted, mothers demonstrated the most negative affect and pain catastrophizing when they were highly anxious and received a functional diagnosis presented by a physician with a biomedical orientation.

For negative affect, mothers with high trait anxiety who received a functional diagnosis from a physician with a biomedical orientation reported significantly higher negative affect compared to mothers with high or low anxiety in all other groups. Least Significant Difference comparisons were conducted to identify the statistically reliable differences among the means contributing to this three-way interaction; the functional biomedical high anxiety condition was significantly greater than all other conditions on negative affect, p < .01. This was a small effect size of d = .32. This interaction effect is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Mothers’ Mean Scores on Negative Affect by Diagnosis, Physician Practice Orientation, and Maternal Trait Anxiety after viewing the Physician Vignette, controlling for baseline Negative Affect.

* The High Anxiety Functional Biomedical condition was significantly greater than all other conditions, p < .01.

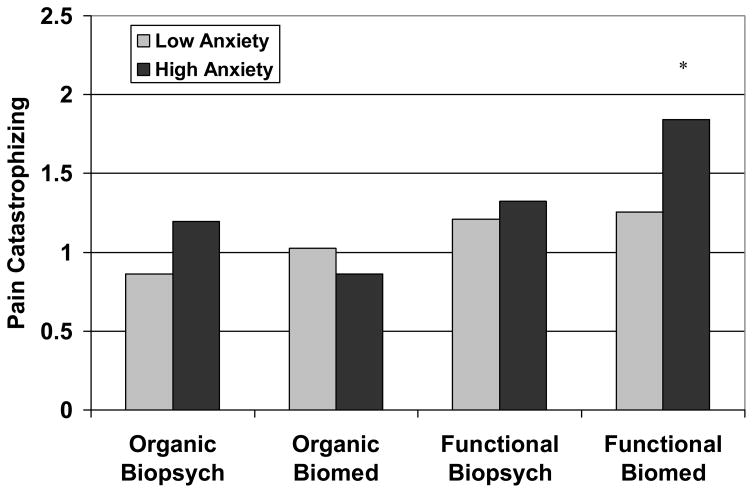

The pattern of the three-way interaction for pain catastrophizing was similar to that for negative affect. Mothers with high trait anxiety who received a functional diagnosis from a physician with a biomedical orientation reported significantly higher pain catastrophizing compared to mothers with high or low trait anxiety in all other groups. As was the case with Negative Affect, the results of Least Significant Difference comparisons indicated that the functional biomedical high anxiety condition was significantly greater than all other conditions on pain catastrophizing, p < .01. Effect size calculation showed a medium effect size; d = .41. This interaction effect is illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Mothers’ Mean Scores on Pain Catastrophizing by Diagnosis, Physician Practice Orientation, and Maternal Trait Anxiety after viewing the Physician Vignette, controlling for baseline Pain Catastrophizing.

* The High Anxiety Functional Biomedical group was significantly greater than all other groups, p < .01.

There were a number of statistically significant main effects and two-way interactions for both negative affect and pain catastrophizing that will not be explained in depth because they were qualified by the three-way interactions. However, one main effect, diagnosis, was general across the physician orientation and maternal anxiety factors, although its magnitude varied across conditions. As predicted, diagnosis (functional versus organic) had significant main effects on negative affect, F (1, 151) = 20.50, p < .001 and pain catastrophizing, F (1, 151) = 19.14, p < .001. Controlling for baseline scores, mothers in the functional condition had significantly higher scores than mothers in the organic condition on both negative affect and pain catastrophizing.

Parent satisfaction

Examination of the means revealed that overall, mothers were highly satisfied with the physician in the medical evaluation vignette; M = 3.46, SD = .77, Observed Range = 0 – 4. As predicted, there was a main effect of diagnosis on satisfaction with the physician; F (1, 152) = 25.72, p < .001. Mothers who received an organic diagnosis were significantly more satisfied (M = 3.75, SD = .52) than mothers who received a functional diagnosis (M = 3.18, SD = .88). This was a large effect size of d = .82.

Also as expected, physician orientation moderated the effect of diagnosis on mothers’ satisfaction with the physician; F (1, 152) = 8.46, p < .01. Mothers who viewed the functional biomedical vignette were significantly less satisfied (M = 3.00, SE = .11) compared to mothers who viewed the functional biopsychosocial vignette (M = 3.34, SE = .11) and mothers who viewed an organic vignette from either a biomedical presentation (M = 3.89, SE = .11) or a biopsychosocial presentation (M = 3.60, SE = .11). Least Significant Difference comparisons were conducted to determine statistically significant differences among the means contributing to this two-way interaction; the functional biomedical condition was significantly lower than all other conditions on physician satisfaction, p < .05. Effect size calculation revealed a medium effect size of d = .47. Maternal anxiety did not have a significant effect on satisfaction with the physician, nor were there reliable interactions of trait anxiety with other factors.

Discussion

Results of this study demonstrated that, given the same level of child pain and disability, mothers reported more negative affect, pain catastrophizing, and dissatisfaction with the physician when the medical evaluation yielded no evidence of organic disease than when the medical evaluation identified organic disease associated with the child’s abdominal pain. Other investigators also have linked medically unexplained or functional symptoms to patient distress [3, 32, 38]. This study extended the literature by identifying characteristics of the physician and mother that moderated the impact on the mother of receiving normal test results from the medical evaluation of a child with chronic pain.

Review of Study Findings

As might be expected given the anxiety reducing effects of information provision [9, 10], parents in all conditions reported reduced distress after being given a diagnosis. However, the degree to which this reduction occurred differed systematically as a function of diagnosis type, presentation style, and maternal trait anxiety.

The physician’s practice orientation—biomedical versus biopsychosocial—had an effect on mothers’ responses to a functional diagnosis for the child’s abdominal pain: Mothers reported significantly less negative affect and less pain catastrophizing, as well as greater satisfaction with the physician, when a functional diagnosis was presented by a physician with a biopsychosocial orientation compared to a physician with a biomedical orientation. These were small and medium effect sizes, based on Cohen’s definition [12]. It may be that a biopsychosocial approach is better suited to meet mothers’ expectation that they will receive an explanation for their children’s pain. Because the biopsychosocial model is based on an assumption of multicausality, physicians with this orientation may be able to explain patient’s symptoms in terms of social, psychological, and physiological factors that contribute to the symptoms even in the absence of organic disease [15, 16, 24, 39, 42]. The primary aim of the biomedical approach, in contrast, is to identify and treat organic disease. In the absence of identifiable disease, providers with a biomedical orientation can offer reassurance that particular diseases have been “ruled out”, but reassurance often is not effective in the face of continued symptoms [14, 32] and may offend the patient and family with the implication that the pain is not “real” [21].

Maternal trait anxiety interacted with physician orientation to moderate mothers’ responses to results of the medical evaluation. Mothers with high trait anxiety reported significantly more negative affect and pain catastrophizing in response to a functional than an organic diagnosis when the diagnosis was delivered by a physician with a biomedical orientation. Ambiguity regarding the cause of medically unexplained symptoms is greater when the medical evaluation is presented from a biomedical perspective, which rules out disease, than from a biopsychosocial perspective, which also explains how multiple factors—both biological and psychosocial—may interact to produce medically benign symptoms. People with high trait anxiety tend to be threatened by ambiguity [5, 19]; thus, mothers with high trait anxiety may be particularly vulnerable to distress when their child’s functional diagnosis (i.e., no identifiable organic cause) is delivered by a physician with a biomedical orientation (i.e., no alternative explanation for symptoms).

Clinical Implications

Considering the high level of trait anxiety observed among parents of children with functional abdominal pain [7, 22, 44], physicians who evaluate these children for chronic abdominal pain are likely to encounter many mothers who may be distressed and dissatisfied with their child’s medical evaluation. Our data indicate that physicians can enhance their relationship with these mothers by using a biopsychosocial model to explain functional abdominal pain, providing a psychophysiological explanation of pain and suggesting interventions that address non-disease factors contributing to symptoms and disability. Physicians should not hesitate to adopt this model, as many mothers of pediatric patients with chronic abdominal pain are receptive to a biopsychosocial approach to children’s pain [11].

The physician vignettes in this study were of equal length regardless of the physician’s practice orientation or results of the medical evaluation. In practice, however, a biopsychosocial approach requires more time with the patient than a biomedical approach, particularly when no organic disease is identified [15]. Mothers with low trait anxiety may be satisfied with a biomedical approach that simply reassures them regarding the absence of underlying organic pathology for their children’s pain, but anxious mothers may require a biopsychosocial explanation that requires additional time. Given the time constraints of a busy clinic, physicians may not be able to do justice to a biopsychosocial explanation for parents of all children with functional abdominal pain. Instead, they might target additional time for the most anxious parents, or use allied health providers to elaborate a biopsychosocial explanation for all parents. Interestingly, mothers in all conditions had a reduction in negative affect and pain catastrophizing from baseline to after viewing the physician vignette, indicating that receiving any information from the physician reassured mothers to some degree.

Limitations and Generalizability

This study adds to the limited empirical research on the effects of a biomedical versus biopsychosocial orientation on patient outcomes and the patient-provider relationship. This is a difficult area for investigation as these models reflect ideologies that providers operationalize in a manner unique to their practice and to individual patients [4]. By using an experimental design to control aspects of the medical encounter that cannot be held constant in a naturalistic setting and using extreme applications of the variables under examination, we advanced research in this important area of investigation.

Given the experimental nature of the design, several factors may impact the findings of the current study, limiting the extent to which the results can be generalized. Sample limitations include the selection of mothers versus fathers and the selection of mothers who, because they were employed in a medical center, may have been more familiar with the medical information presented in the physician vignettes than a community sample. In addition, recruitment of mothers without regard to their children’s health status may have produced different findings than would be the case for mothers of children with chronic illnesses whose responses may have reflected their own experiences.

Additional limitations exist in the vignettes developed for the study. The content of the physician vignettes was grounded in the literature on illness schema and clinical application of the biomedical and biopsychosocial models. Moreover, pediatricians and sub-specialists reviewed and modified the scripts until they agreed that the scripts reflected prototypical biopsychosocial and biomedical approaches that they had observed in their colleagues. Nonetheless, information imparted in actual pediatric medical encounters may differ from that presented in the physician vignettes. Most providers do not have a practice style that can be classified as exclusively biomedical or biopsychosocial [27]. Although we strove to match the four vignettes on information presented about diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis, inherent differences between the biomedical and biopsychosocial models preclude a perfect match on all content that may influence parents’ responses. For example, referral to a psychiatrist was mentioned only in the Functional Biomedical physician vignette; this may have been perceived as frightening or stigmatizing by anxious mothers, in particular. While it is reasonable to conclude that the physician vignettes approximate the reality of a pediatric medical encounter, a naturalistic study is the only way to ensure authenticity of medical information presented from different orientations.

Finally, in any social interaction, information is communicated both verbally and nonverbally. The physician-actor in the vignettes strove to maintain consistent eye contact, deliver his message in the same tone of voice, and keep the same degree of warmth when delivering his message in all four physician vignettes; however, we did not measure participants’ ratings of the physician’s nonverbal communication across vignettes. Future studies would benefit from measures of both verbal and nonverbal communication by providers who are giving different messages.

Future Directions

Additional research is needed to investigate potential clinical implications of our findings. A recent study of patients with low back pain found that patient outcomes did not differ for treatments based on biomedical versus biopsychosocial models [34]. Our findings suggest that mothers with high trait anxiety may respond more favorably to physicians who take a biopsychosocial versus a biomedical approach to children with functional abdominal pain. The next step in this research is to assess whether clinical outcomes for pediatric patients differ when the physician’s practice style reflects a biopsychosocial versus biomedical orientation.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH Grant R01 HD23264 to Lynn S. Walker, a Vanderbilt University Graduate School Dissertation Enhancement Grant to Sara E. Williams, the Vanderbilt Institute for Clinical and Translational Research UL1 RR024975, and NICHD Grant P39HD15052 to the Vanderbilt Kennedy Center for Research on Human Development.

The authors thank Dr. Bruce Compas for his participation on Dr. Williams’ dissertation committee and Lindsey Franks for her contributions to data collection.

Appendix

Physician Vignette 1: Organic Biopsychosocial

MD presents evaluation results

Hi, good to see you again. We have the results of your daughter’s evaluation. As you might remember, we sent some samples of her blood and urine to the lab the last time you were here. Those tests have come back and they’re all normal. We also at that time did an endoscopy and that’s when we put the tube down inside of her stomach and took a look around and also took some biopsies at that time. The biopsy results have come back and they show some mild inflammation in some of the cells in her stomach.

Parent asks: What is her diagnosis?

The results of the stomach biopsy tells us that your daughter has gastritis. What that means is there’s some areas in the lining of her stomach that are mildly inflamed.

Parent asks: Why is she having such severe pain?

Inflammation isn’t the only thing that can be causing her her pain. Other things such as emotions and stress can also intensify pain signals. When you think it about, when you’re upset or you’re stressed, pain has a tendency to get worse, it’s kind of like turning up the volume on the television. And then the other thing we also have a tendency to see is that when patients focus on pain, it can make it worse as well.

Parent asks: What can you do for her?

You know, as far as what we can do for her pain, I can give her some medication that’s going to help reduce the acid in her stomach so that’ll allow the inflammation that she has there currently to heal. I think the other thing that we see is that stress can also aggravate pain, so many patients, like your daughter, can get some control over their pain by learning some stress and some pain management techniques. I’ve got a great psychologist who I work with who can help her cope with her pain and with her stress and teach her some pain management techniques. For example, she can learn how to use relaxation and distraction to turn down the volume of the pain signals.

Parent asks: What if she keeps having pain?

That’s a great question. I’ll be seeing her again in a couple of weeks to see how she’s doing. I’ll give her a different medication if the one that I give her today doesn’t work. The other thing is the psychologist will keep working with her on her strategies to cope with stress and help her manage her pain.

Parent asks: Can she go to school?

Oh yes, she can go back to school and continue her normal activities. In fact, being involved in activities will help distract her from the pain and make her feel better.

Word Count: 422

Playing Time: 2:41

Physician Vignette 2: Organic Biomedical

MD presents evaluation results

Hi, good to see you again. We have the results of your daughter’s evaluation. As you might remember, we sent some samples of her blood and urine to the lab the last time you were here. Those tests have come back and they’re all normal. We also at that time did an endoscopy and that’s when we put the tube down inside of her stomach and took a look around and also took some biopsies at that time. The biopsy results have come back and they show some mild inflammation in some of the cells in her stomach.

Parent asks: What is her diagnosis?

The results of the stomach biopsy tells us that your daughter has gastritis. What that means is there’s some areas in the lining of her stomach that are mildly inflamed.

Parent asks: Why is she having such severe pain?

Even some minor inflammation in the stomach can cause a lot of pain. The stomach lining is red and irritated, so it’s very sensitive to the stomach acid that digests food. And that combination of inflammation in the stomach plus the acid that’s already there can irritate nerves that send pain signals.

Parent asks: What can you do for her?

As far as what I can do for her, what I’d like to do is give her a prescription for Reduxal. This is a medicine that should reduce the acid in her stomach so that the inflammation can heal. This medicine comes in either a liquid form or a tablet form, but I usually like to use the liquid form in kids her age. What I’d like to do for the first week is give her a tablespoon in the morning right before she eats breakfast and then also have her take a tablespoon at night right before she goes to bed. After that first week, she’ll only need to take a tablespoon at night. I’m going to give you a one month prescription of the medicine.

Parent asks: What if she keeps having pain?

That’s a great question. I’ll be seeing her again in a of couple weeks to see how she’s doing. I’ll give her a different medicine if this one doesn’t work. There are several different kinds of medicines that are out there that can be used to reduce stomach acid.

Parent asks: Can she go to school?

Oh yes, she can go back to school and continue her normal activities. This medication should start working pretty quickly and should make her feel better.

Word Count: 382

Playing Time: 2:29

Physician Vignette 3: Functional Biopsychosocial

MD presents evaluation results

Hi, good to see you again. Well we have the results of your daughter’s evaluation. As you know, the last time you were here we sent some samples of her blood and urine to the lab. Those test results have come back and they’re normal. At that time we also did an endoscopy and that’s when we put the tube down inside of her stomach and when I took a look at that time everything looked normal. While I was down there, I took some biopsies and those results are back and those are normal as well. So there is no evidence of any disease or any other abnormality.

Parent asks: What is her diagnosis?

Given that the results of the lab tests and the results from the endoscopy were normal, your daughter has functional abdominal pain. She may be hypersensitive to sensations in her stomach.

Parent asks: Why is she having such severe pain?

In patients with functional abdominal pain, emotions and stress can intensify the sensations and make them more painful. When you think about it, when you’re upset or stressed, pain gets worse, it’s sort of like turning up the volume on the television. Also, what we tend to see is that focusing on the pain can make it worse as well.

Parent asks: What can you do for her?

You know, as far as what we can do for your daughter, you know stress can aggravate pain, so many patients can get some control over their pain by learning stress and pain management techniques. I’ve got this great psychologist who I work with who can help her cope with the stress and teach her some pain management techniques. You know, for example, she can learn how to use relaxation and distraction to turn down the volume of her pain signals, and that should help her cope with the pain.

Parent asks: What if she keeps having pain?

That’s a great question. I’ll see her again in a couple of weeks to see how she’s doing. In the meantime, the psychologist will be seeing her weekly to teach her strategies to cope with her stress and help her manage her pain.

Parent asks: Can she go to school?

Oh yes, she can go back to school and continue her normal activities. In fact, being involved in activities will help distract her from the pain and make her feel better.

Word Count: 364

Playing Time: 2:27

Physician Vignette 4: Functional Biomedical

MD presents evaluation results

Hi, good to see you again. Well we have the results of your daughter’s evaluation. As you know, the last time you were here we sent some samples of her blood and urine to the lab. Those test results have come back and they’re normal. At that time we also did an endoscopy and that’s when we put the tube down inside of her stomach and when I took a look at that time everything looked normal. While I was down there, I took some biopsies and those results are back and those are normal as well. So there is no evidence of any disease or any other abnormality.

Parent asks: What is her diagnosis?

Your child seems to be perfectly healthy. Her history, physical exam and test results don’t show anything wrong with her.

Parent asks: Why is she having such severe pain?

You know, physically, there’s really no reason for her to have any type of pain. You know, we’ve done all the tests that were indicated and they all came back normal. You know, the pain is probably caused by stress or emotions. This seems to be more of a psychological problem and not a medical problem.

Parent asks: What can you do for her?

You know, as far as what we can do for your daughter, I can tell you she’s in good health. When I looked down into her stomach with the endoscopy, it looked just fine. The lining of her stomach is nice and pink and healthy-looking. The results of the biopsy in addition to the blood and the urine tests were all normal. We’ve ruled out a number of conditions, such as infections, food allergies, ulcers, and Crohn’s disease that can cause abdominal pain. So there’s really nothing medically we can do for her.

Parent asks: What if she keeps having pain?

You know, that’s a great question. You know, at this point, there’s really nothing more that I can do for her. Since this is not a physical problem, I would suggest seeing a psychiatrist if the pain continues. I can give you the name of a great child psychiatrist if you want one.

Parent asks: Can she go to school?

Oh yes, she can go back to school and continue her normal activities. She’s not physically sick, so there’s really no reason for her to stay home.

Word Count: 358

Playing Time: 2:25

Footnotes

No authors had any conflicts of interest.

The covariance adjustment was such that the units and theoretical range of the variables remained unchanged.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Apley J. The Child with Abdominal Pains. London: Blackwell; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Apley J, Naish N. Recurrent abdominal pain: A field survey of 1,000 school children. Arch Dis Child. 1958;33:165–70. doi: 10.1136/adc.33.168.165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bertram S, Kurland M, Lydick E, Locke GR, Yawn BP. The patient’s perspective of irritable bowel syndrome. J Fam Pract. 2001;50:521–525. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borrell-Carrio F, Suchman AL, Epstein RM. The biopsychosocial model 25 years later: Principles, practice, and scientific inquiry. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2:576–582. doi: 10.1370/afm.245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cameron LD. Anxiety, cognition, and responses to health threats. In: Cameron LD, Leventhal H, editors. The Self-Regulation of Health and Illness Behavior. NY: Routledge; 2003. pp. 157–83. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campo JV, Bridge J, Ehmann M, Altman S, Lucas A, Birmaher B, Di Lorenzo C, Iyengar S, Brent DA. Recurrent abdominal pain, anxiety, and depression in primary care. Pediatrics. 2004;113:817–24. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.4.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campo JV, Bridge J, Lucas A, Savorelli S, Walker L, Di Lorenzo C, Iyengar S, Brent DA. Physical and emotional health of mothers of youth with functional abdominal pain. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161:131–7. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.2.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campo JV, Fritsch SL. Somatization in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1994;33:1223–35. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199411000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cioffi DL. Asymmetry of doubt in medical self-diagnosis: The ambiguity of “uncertain wellness. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1991;61:969–80. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.61.6.969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cioffi DL. When good news is bad news: Medical wellness as a nonevent in undergraduates. Health Psychol. 1994;13:63–72. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.13.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Claar RL, Walker LS. Maternal attributions for the causes and remedies of their children’s abdominal pain. J Pediatr Psychol. 1999;24:345–54. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/24.4.345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Earlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crawford JR, Henry JD. The Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS): Construct validity, measurement properties and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. Br J Clin Psychol. 2004;43:245–65. doi: 10.1348/0144665031752934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Donovan JL, Blake DR. Qualitative study of interpretation of reassurance among patients attending rheumatology clinics: “just a touch of arthritis, doctor? BMJ. 2000;320:541–544. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7234.541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Drossman DA. Presidential Address: Gastrointestinal illness and the biopsychosocial model. Psychosom Med. 1998;60:258–67. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199805000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Engel G. The need for a new medical model: A challenge for biomedicine. Science. 1977;196:129–36. doi: 10.1126/science.847460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Engel G. The clinical application of the biopsychosocial model. Am J Psychiatry. 1980;137:535–44. doi: 10.1176/ajp.137.5.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Esler JL, Bock BC. Psychological treatments for noncardiac chest pain: Recommendations for a new approach. J Psychosom Res. 2004;56:263–9. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(03)00515-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eysenck MW. Anxiety and Cognition: A Unified Theory. Brighton, UK: Psychology Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ferrari R. The biopsychosocial model—a tool for rheumatologists. Baillieres Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2000;14:787–95. doi: 10.1053/berh.2000.0113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fleisher DR, Feldman EJ. The biopsychosocial model of clinical practice in functional gastrointestinal disorders. In: Hyman PE, editor. Pediatric Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders. New York: Academy Professional Information Services; 1999. pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garber J, Zeman J, Walker LS. Recurrent abdominal pain in children: Psychiatric diagnoses and parental psychopathology. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1990;29:648–56. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199007000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gatchel RJ. Comorbidity of chronic pain and mental health disorders: The biopsychosocial perspective. Am Psychol. 2004;59:795–805. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.8.795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gatchel RJ, Maddrey AM. The biopsychosocial perspective of pain. In: Leviton LC, Raczynski JM, editors. Handbook of clinical health psychology. Disorders of behavior and health. Vol. 2. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2004. pp. 357–78. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goubert L, Eccleston C, Vervoort T, Jordan A, Crombez G. Parental catastrophizing about their child’s pain. The parent version of the Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS-P): A preliminary validation. Pain. 2006;123:254–63. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guite JW, Walker LS, Smith CA, Garber J. Children’s perceptions of peers with somatic symptoms: The impact of gender, stress, and illness. J Pediatr Psychol. 2000;25:125–35. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/25.3.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Houben RM, Ostelo RW, Vlaeyen JW, Wolters PM, Peters M, Stomp-van den berg SG. Health care providers’ orientations towards common low back pain predict perceived harmfulness of physical activities and recommendations regarding return to normal activity. Eur J Pain. 2005;9:173–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2004.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hyams JS, Hyman PE. RAP and the biopsychosocial model of medical practice. J Pediatr. 1998;133:473–8. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(98)70053-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kroenke K, Mangelsdorff A. Common symptoms in ambulatory care: Incidence, evaluation, therapy, and outcome. Am J Med. 1989;86:262–6. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(89)90293-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leventhal H, Meyer D, Nerenz D. The common sense representation of illness danger. In: Rachman S, editor. Medical Psychology. Vol. 2. New York: Pergamon Press; 1980. pp. 7–30. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Like R, Reeb KG. Clinical hypothesis testing in family practice: A biopsychosocial perspective. J Fam Pract. 1984;19:517–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McDonald IG, Daly J, Jelinek VM, Panetta F, Gutman JM. Opening Pandora’s box: the unpredictability of reassurance by a normal test result. BMJ. 1996;313:329–332. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7053.329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition. Pediatric gastroenterology workforce survey, 2003–2004. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2005;40:395–407. doi: 10.1097/01.mpg.0000158523.92175.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sieben JM, Vlaeyen JWS, Portegijs PJM, Warmenhoven FC, Sint AG, Dautzenberg N, Romeijnders A, Arntz A, Andre Knottnerus J. General practitioners’ treatment orientations towards low back pain: Influence on treatment behaviour and patient outcome. Eur J Pain. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2008.05.002. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Simonian SJ, Tarnowski KJ, Park A, Bekeny P. Child, parent, and physician perceived satisfaction with pediatric outpatient visits. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1993;14:8–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Spielberger CD. Anxiety: Current trends in research. London: Academic Press; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene RE. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stenner PH, Dancey CP, Watts S. The understanding of their illness amongst people with irritable bowel syndrome: A Q methodological study. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51:439–52. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00475-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stone J, Carson A, Sharpe M. Functional symptoms and signs in neurology: Assessment and diagnosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76(Suppl I):i2–i12. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2004.061655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Suarez-Almazor M. Patient-physician communication. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2004;16:91–5. doi: 10.1097/00002281-200403000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van Tilburg MAL, Venepalli N, Ulshen M, Freeman KL, Levy R, Whitehead WE. Parents’ worries about recurrent abdominal pain in children. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2006;29:50–5. doi: 10.1097/00001610-200601000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wade DT, Halligan PW. Do biomedical models of illness make for good healthcare systems? BMJ. 2004;329:1398–1401. doi: 10.1136/bmj.329.7479.1398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Walker LS, Garber J, Van Slyke DA, Greene JW. Long-term health outcomes in patients with recurrent abdominal pain. J Pediatr Psychol. 1995;20:233–45. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/20.2.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Walker LS, Greene JW. Children with recurrent abdominal pain and their parents: More somatic complaints, anxiety, and depression than other patient families? J Pediatr Psychol. 1989;14:231–43. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/14.2.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;54:1063–70. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wenzel A, Finstrom N, Jordan J, Brendle J. Memory & interpretation of threat in socially anxious & nonanxious individuals. Behav Res Ther. 2005;43:1029–44. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2004.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]