Abstract

Purpose

A variety of cancers, including malignant gliomas, overexpress transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), which helps tumors evade effective immune surveillance through a variety of mechanisms, including inhibition of CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL) and enhancing the generation of regulatory T (Treg) cells. We hypothesized that inhibition of TGF-β would improve the efficacy of vaccines targeting glioma-associated antigen (GAA)-derived CTL epitopes by reversal of immunosuppression.

Experimental Design

Mice bearing orthotopic GL261 gliomas were treated systemically with a TGF-β neutralizing monoclonal antibody, 1D11, with or without subcutaneous (s.c.) vaccinations of synthetic peptides for GAA-derived CTL epitopes, GARC-1 (77-85) and EphA2 (671-679) emulsified in incomplete Freund's adjuvant.

Results

Mice receiving the combination regimen exhibited significantly prolonged survival compared with mice receiving either 1D11 alone, GAA-vaccines alone or mock-treatments alone. TGF-β neutralization enhanced the systemic induction of antigen-specific CTLs in glioma-bearing mice. Flow cytometric analyses of brain infiltrating lymphocytes revealed that 1D11 treatment suppressed phosphorylation of Smad2, increased GAA-reactive/interferon (IFN)-γ-producing CD8+ T cells, and reduced CD4+/FoxP3+ Treg cells in the glioma microenvironment. Neutralization of TGF-β also up-regulated plasma levels of interleukin (IL)-12, macrophage inflammatory protein-1α and IFN-inducible protein-10, suggesting a systemic promotion of type-1 cytokine/chemokine production. Furthermore, 1D11 treatment up-regulated plasma IL-15 levels and promoted the persistence of GAA-reactive CD8+ T cells in glioma-bearing mice.

Conclusions

These data suggest that systemic inhibition of TGF-β by 1D11 can reverse the suppressive immunological environment of orthotopic tumor-bearing mice both systemically and locally, thereby enhancing the therapeutic efficacy of GAA-vaccines.

Keywords: Transforming growth factor β, glioma vaccines, type-1 immune response, regulatory T cells

Introduction

Malignant gliomas represent the most common primary CNS tumors and exhibit a dismal prognosis despite recent advances made in surgical, radiological, and chemotherapeutic approaches (1). Development of novel, multimodal therapeutic approaches is thus critical to improve the outcome of these deadly tumors (2). Among these approaches, immunotherapy can be promising for glioma treatment if we are able to induce potent immune responses directed against glioma-associated antigens (GAAs) (3-5). Indeed, several immunological strategies have been evaluated in early phase clinical trials; however, modest clinical benefit in glioma immunotherapy trials calls for further improvement of these strategies (6).

TGF-β is a highly pleiotropic cytokine that plays key regulatory roles in many aspects of immunity (7). It directly inhibits cytolytic activity of natural killer cells, macrophages, and CD8+ cytotoxic T cells (8, 9). It can also inhibit instruction, activation, and expansion of tumor-specific helper and cytotoxic T-cell populations (10) and enhance the generation of immunosuppressive regulatory T (Treg) cells (11). Thus, the presence of TGF-β in the tumor microenvironment is predicted to disable effective immune surveillance by multiple mechanisms. Indeed, many human tumors, including malignant gliomas, overexpress TGF-β, and elevated expression frequently correlates with tumor progression and poor prognosis (12). The mammalian TGF-β isoforms β1, β2, and β3 are produced by various malignant glioma cells (13, 14). Indeed, in a recent phase I clinical trial of dendritic cell (DC)-based vaccines in glioblastoma multiforme (GBM), resection of post-vaccine tumors demonstrated that TGF-β2 expression within the tumors was inversely correlated with both the intensity of tumor infiltration by cytotoxic T cells and clinical survival (15). Furthermore, data from pre-clinical studies suggests that antagonism of TGF-β can suppress tumorigenesis by enhancing and/or restoring effective antitumor immune surveillance (16-18). These observations led to the hypothesis that inhibition of TGF-β would reverse TGF-β-induced immunosuppression and improve the efficacy of vaccines targeting GAA-derived cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) epitopes.

In the current study, administration of the TGF-β neutralizing monoclonal antibody (mAb), 1D11, can promote systemic and local CTL responses against GAA-derived CTL epitopes, and reverse the suppressive immunological environment of orthotopic gliomas, and thereby enhance the therapeutic efficacy of GAA-vaccines. This study provides strong support for the development of novel combinational strategies using anti-TGF-β mAb in anti-glioma vaccine clinical trials.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

RPMI 1640, FBS, L-glutamine, sodium pyruvate, β-mercaptoethanol, nonessential amino acids, and antibiotics were obtained from Invitrogen Life Technologies (Grand Island, NY). Recombinant human interleukin-2 (rhIL-2) was obtained from PeproTech (Rocky Hill, NJ). The following peptides were synthesized by the automated solid-phase peptide synthesizer in the University of Pittsburgh Peptide Synthesis Facility with >95% purity as indicated by analytical high-performance liquid chromatography and mass spectrometric analysis: H-2Db-binding EphA2671-679 (FSHHNIIRL), H-2Db–binding GARC-177-85 (AALLNKLYA), I-Ab-binding HBV core128-140 (TPPAYRPPNAPIL), H-2Db-binding human/mouse gp100 (h/mgp100) 25-33 (KVPRNQDWL), and H-2Kb–binding ovalbumin (OVA)257-264 (SIINFEKL).

Cell culture

The TAP2-/- RMAS mouse thymoma cell line (H-2b) was kindly provided by Dr. Walter J. Storkus (University of Pittsburgh, PA). GL261 mouse glioma cells (H-2b) kindly provided by Dr. Robert Prins (University of California Los Angeles, LA), express mgp100, EphA2, and GARC-1 as GAAs (4, 19, 20). All cells were maintained in mouse complete medium (RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS, 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 mg/ml streptomycin, and 10 μM L-glutamine [GIBCO® Invitrogen]) in a humidified incubator in 5% CO2 at 37°C. Culture supernatants were harvested, filtered, and concentrated 10-fold using an Amicon Ultra Filter (Millipore). GL261-conditioned medium (GL261-CM) was prepared by mixing the concentrated medium and fresh medium at 1:9 ratio.

Animals

C57BL/6 mice (H-2b) were obtained from Taconic Farms (Germantown, NY). Animals were handled in the Animal Facility at the University of Pittsburgh per an Institutional Care and Use Committee-approved protocol.

Antibodies and tetramers

The anti–murine TGF-β mAb, 1D11, which neutralizes all three isoforms of TGF-β (21), and a murine IgG1 mAb against Shigella toxin, 13C4, which serves as an isotype control, were provided by Genzyme Corporation (Framingham, MA). The following antibodies were obtained from CALTAG Laboratories (Carisbad, CA): PE-conjugated anti-IFN-γ, TC-conjugated anti-CD4, TC-conjugated anti-CD8, and isotype-matched controls. FITC-conjugated anti-CD8 (53-6.7) and PE-conjugated anti-CD25 (PC61) were obtained from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA). Anti-Smad2 and anti-phosphorylated Smad2 (pSmad2) antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). APC-conjugated anti-CD62L (MEL-14) and PE-Cy7-conjugated anti-CD44 (IM7) were purchased from BioLegend (San Diego, CA). PE-conjugated anti-FoxP3 (NRRF-30) antibody was obtained from eBioScience (San Diego, CA). PE-conjugated H-2Db/EphA2671-679 tetramer (EphA2 tetramer) and PE-conjugated H-2Db/GARC-177-85 tetramer (GARC-1 tetramer) were produced by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease tetramer facility within the Emory University Vaccine Center (Atlanta, GA).

Flow cytometry

The procedure used in the current study has been described previously (22). Briefly, single cell suspensions were surface-stained with fluorescent dye-conjugated antibodies. For intracellular staining, cells were surface-stained, washed, fixed, permeabilized with Cytofix/Cytoperm buffer (BD Biosciences), and intracellularly stained. All stained cells were compared with those stained with isotype-matched control antibodies. Samples were examined by Coulter EPICS cytometer or CyAn ADP (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA) and data were analyzed by the WinMDI software (http://facs.scripps.edu/software.html) or Summit software (Dako Colorado, Inc. Fort Collins, CO).

Intracranial (i.c.) injection of GL261 glioma cells

The procedure used in the current study has been described previously (22-25). Briefly, using a Hamilton syringe (Hamilton Company, Reno, NV), 1×105 GL261 cells in 2 μl PBS were stereotactically injected through an entry site at the bregma, 3 mm to the right of sagittal suture, and 4 mm below the surface of the skull of anesthetized mice by using a stereotactic frame (Kopf, Tujunga, CA).

Treatment of i.c. tumor-bearing mice with anti-TGF-β antibody and GAA peptide-based vaccines

Beginning three days following tumor cell inoculation, 25mg/kg of anti–TGF-β antibody (1D11) or isotype control antibody (13C4) was administered i.p. every two days for a total of twelve doses. The animals received s.c. vaccinations with HBV core128-140 and GAA peptides, including EphA2671-679 and GARC-177-85 (100 μg each peptide), emulsified in incomplete Freund's adjuvant (IFA) (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Michigan, MI) on days 3, 13 and 23 after tumor inoculation. In some experiments, symptom-free survival was monitored as the primary endpoint; in other experiments, treated mice were sacrificed on indicated days to evaluate immunological endpoints such as effects on brain infiltrating lymphocytes (BILs).

BIL isolation

The procedure used in the current study has been described previously 25. Briefly, mice were sacrificed by CO2 asphyxia and immediately perfused with PBS through the left cardiac ventricle. Brain tissues were mechanically minced, resuspended in 70% Percoll (Sigma-Aldrich), overlaid with 37% and 30% Percoll, and centrifuged for 20 min at 500 ×g. Enriched BIL populations were recovered at the 70%-37% Percoll interface.

Cytokine and chemokine release assay

Peripheral blood samples were collected from the tail vein of mice, centrifuged, and the resulting supernatents were pooled as plasma samples. The cytokine and chemokine levels in plasma samples were evaluated by specific ELISA kits. The following ELISA kits for murine cytokines and chemokines were purchased from commercial vendors: IL-12p70 (eBioscience); TGF-β1, interferon (IFN)-inducible protein-10 (IP-10), and IL-15 (R&D Systems). Mouse cytokines and chemokines were also analyzed using a 20-plex kit from Invitrogen/Biosource for IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12p40/p70, IL-13, IL-17, IP-10, IFN-γ, monokine induced by IFN-γ (MIG), macrophage inflammatory protein-1α (MIP-1α), tumor necrosis factor–α (TNF-α), and monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1) by the University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute (UPCI) Luminex Core Facility. Analyses of mouse plasma were performed in a 96-well micro plate format according to manufacturers' protocols as previously described (26). Data were presented as the mean ± SD pg/mg of protein.

In vitro cytolytic assay

The procedure used in the current study has been described previously (5). Briefly, target GL261 or peptide-loaded RMAS cells (1×104 cells in 100 μl) labeled with 50 μCi of Na251CrO4 (51Cr) were added to wells containing 100 μl of varying numbers of effector cells using U-bottomed 96-well plates (Corning, Lowell, MA). After a 4-hr incubation at 37°C, 30 μl of supernatants were harvested from each well and transferred to wells of a LumaPlate-96 (Packard Inc., Prospect, CT). The amount of 51Cr in each well was measured in a Micro Plate Scintillation Counter (Packard Inc.). The percentage of specific lysis (% specific lysis) was calculated using triplicate samples as follows: percentage lysis = (cpm experimental release-cpm spontaneous release)/(cpm maximal release-cpm spontaneous release) × 100.

Statistical analysis

The statistical significance of differences between groups was determined by one-way analysis of variance with Holm's post hoc test. Survival data were analyzed by log rank test. We considered differences significant when p <0.05. All data were analyzed by SPSS version 14.0 (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois) and Statcel 2 (OMS Publishing Inc, Saitama, Japan).

Results

Systemic inhibition of TGF-β improves the therapeutic efficacy of vaccinations targeting GAA-derived CTL epitopes

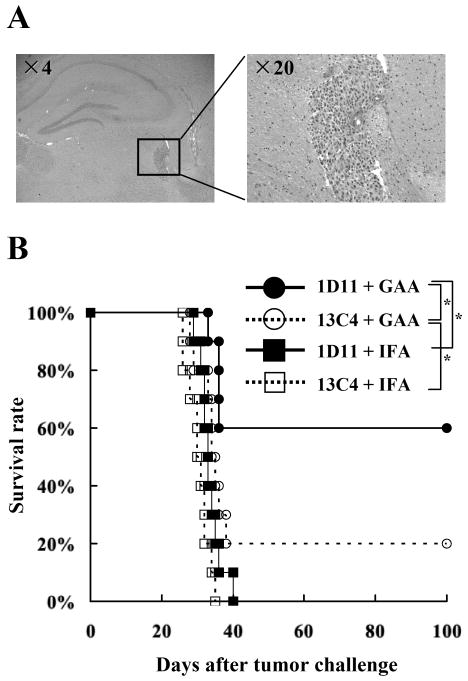

To evaluate the therapeutic benefit of neutralization of TGF-β in combination with a vaccine therapy, mice were treated with 1D11 in combination with s.c. vaccinations targeting GAA-derived CTL epitopes EphA2671-679 and GARC-177-85.beginning three days after i.c. injection of GL261 glioma cells. Histological evaluations confirmed that i.c. injected GL261 cells form solid and vascularized tumors in the brain of syngeneic mice on day 3 following stereotactic inoculation (Figure 1A). Mice receiving the combinatorial therapy of 1D11 and GAA-vaccines exhibited significantly improved survival with 6 of 10 mice treated with the combination regimen surviving longer than 100 days, whereas only 2 of the 10 mice treated with GAA-vaccines and the isotype control antibody, 13C4, survived longer than 100 days (Figure 1B). Treatment with either 1D11+IFA or 13C4+IFA did not provide significant therapeutic benefit in this model. These results indicate that the therapeutic effects of GAA-vaccines can be significantly enhanced by i.p. administration of 1D11.

Figure 1. Systemic inhibition of TGF-β improves the therapeutic efficacy of vaccinations targeting GAA-derived CTL epitopes.

On day 0, each C57BL/6 mouse received a stereotactic injection with 1×105 GL261 glioma cells into the right basal ganglia. Starting on day 3, anti–TGF-β antibody (1D11) or control antibody (13C4) were administered i.p. at a dose of 25mg/kg every two days for a total of twelve doses. On days 3, 13, and 23, mice received s.c. immunization with 100 μg of each GAA peptide and HBVcore128 T-helper epitope peptide emulsified in IFA. A, H&E staining of frozen brain sections derived from C57BL/6 mice bearing day 3 GL261 glioma in the right basal ganglia. B, the mice were stratified into 4 treatment groups: 1) 1D11 plus GAA-vaccines (solid circles); 2) 13C4 plus GAA-vaccines (hollow circles); 3) 1D11 plus control vaccines with HBVcore128 T-helper epitope peptide emulsified in IFA alone (solid squares) and 4) 13C4 plus control vaccines (hollow squares). Symptom-free survival of mice was monitored. n = 10 mice/group. *, p < 0.05 for the mice treated with 1D11 plus GAA-vaccines compared with the mice treated with 13C4 plus GAA-vaccines or 1D11 plus control vaccines *, p < 0.05 for the mice treated with 13C4 plus GAA-vaccines compared with the mice treated with 13C4 plus control vaccines.

Effects of 1D11 on the systemic induction of GAA-specific CTL responses

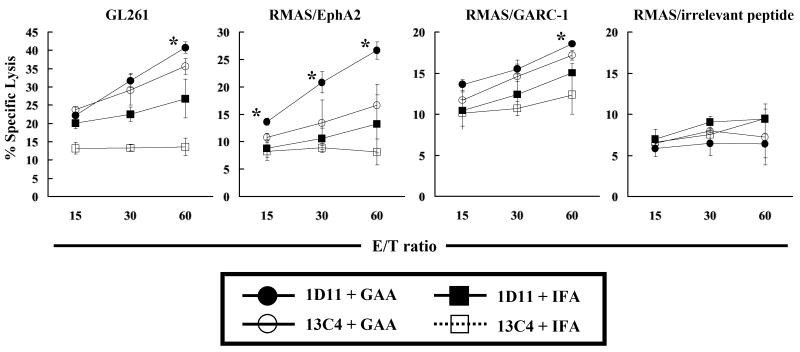

The impact of 1D11 administration on the systemic induction of GAA-specific CTL responses was evaluated using splenocytes from glioma-bearing mice treated with the solo or combinatorial therapies (Figure 2). 1D11 treatment significantly elevated the levels of vaccine-induced CTL activity in the spleen and draining lymph nodes against RMAS cells loaded with EphA2671-679 at all effector/target (E/T) ratios. Although modest, significant increases of the vaccine-induced CTL activity against GL261 cells and GARC-177-85-loaded RMAS cells were observed at an E/T ratio of 60:1 (Figure 2). No increase of CTL activity was observed against RMAS cells loaded with an irrelevant peptide, as expected.

Figure 2. 1D11 enhances the systemic induction of specific CTL responses against GAA-derived CTL epitopes.

SPCs and draining inguinal lymph node cells were harvested and mixed together on day 25 after i.c. tumor inoculation. Following a five-day in vitro stimulation with 50 IU/ml IL-2 and each GAA peptide, these cells were tested for their cytolytic activity against GL261 glioma cells or RMAS loaded with GARC-177-85, EphA2671-679, or irrelevant OVA257-264 peptide. *, p < 0.05 for tumor-bearing mice treated with 1D11 plus GAA-vaccines (solid circles) compared with the tumor-bearing mice treated with 13C4 plus GAA-vaccines (hollow circles) at all E/T ratios. The results represent the mean ± SD of samples from three mice per group. One of two representative experiments with similar results is shown.

Systemic administration of 1D11 leads to decreased TGF-β signaling in the glioma microenvironment

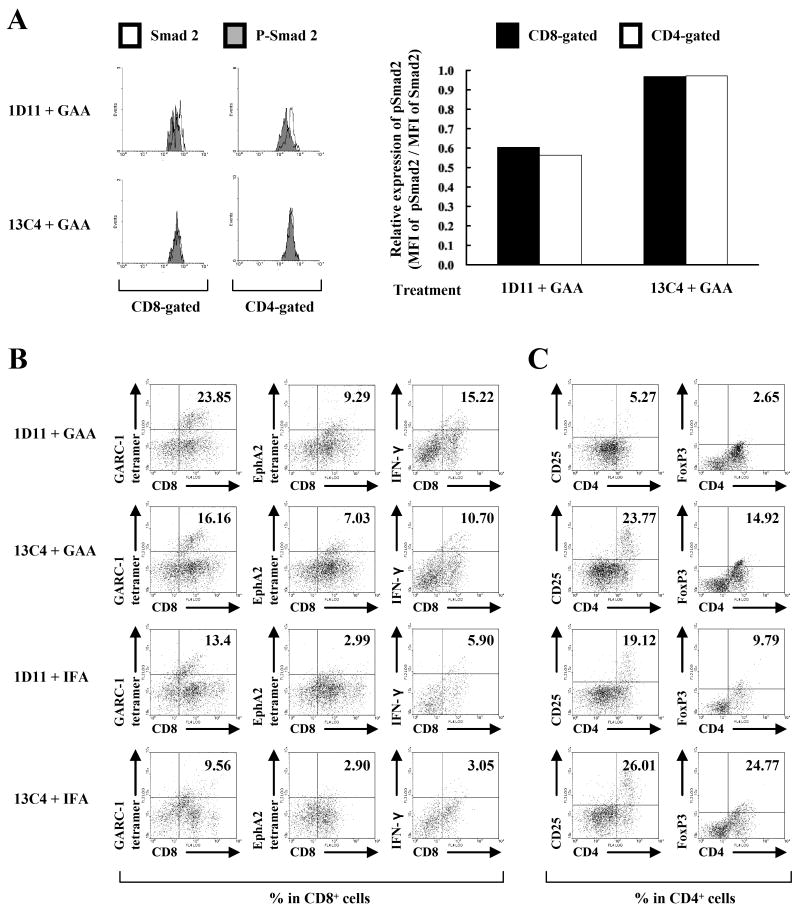

Despite the remarkable improvement of the therapeutic efficacy in glioma-bearing mice (Figure 1), 1D11 treatment only modestly enhanced the systemic CTL activities induced by GAA-vaccines (Figure 2), suggesting that 1D11 treatment might promote anti-glioma immunity in the i.c. glioma microenvironment. To address this, the TGF-β signaling status (Figure 3A) and phenotype (Figure 3B and C) of BILs was evaluated. TGF-β binding to its cell-surface receptors results in phosphorylation of the receptor leading to subsequent phosphorylation and activation of downstream signal transducers called Smads (27). Phosphorylated Smad2 (pSmad2) and Smad3 (pSmad3) associate with Smad4 then translocate to the nucleus to initiate transcription of TGF-β-mediated genes (28). Therefore, 1D11-mediated inhibition of Smad2 phosphorylation in vitro and in vivo was investigated. Secretion of TGF-β by GL261 glioma cells was confirmed through ELISA analysis of conditioned media of GL261 cells grown in culture as these cells secrete 163 ± 33 pg/106 cells/24 hours. Furthermore, conditioned media from GL261 cells could induce phosphorylation of Smad2 in splenocytes (SPCs) from naïve C57BL/6 mice and treatment with 1D11 inhibited Smad2 phosphorylation (Supplementary Figure S1), demonstrating secretion of active TGF-β by GL261 cells and confirming functional blockade of the TGF-β signaling by 1D11.

Figure 3. Systemic 1D11 promotes type-1 anti-GAA CTLs while reducing Treg cells in the i.c. glioma tissue.

Mice bearing orthotopic gliomas were treated with 1D11 and GAA vaccines as described previously. A, left panels, on day 25, BILs were isolated, and intracellular pSmad2 and Smad2 levels were evaluated in CD8- or CD4-gated populations by flow cytometry. Open and shaded histograms represent cells stained for Smad2 or pSmad2, respectively. Right panels, relative expression levels of pSmad2 in CD8-gated (black columns) or CD4-gated (white columns) population of the BILs calculated as relative mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) values of pSmad2 to those of Smad2 in corresponding cell populations. BILs were isolated from treated mice, and flow cytometric analyses were performed for (B) surface expression of CD8 and GARC-177-85 tetramer, EphA2671-679 tetramer or intracellular IFN-γ, and (C) surface expression of CD4 and CD25 or intracellular FoxP3 in lymphocyte-gated populations. For flow cytometric analyses of BILs (B and C), because of the small number of BILs obtained per mouse (∼4×105 cells/mouse), BILs obtained from 5 mice per group were pooled, and evaluated for the relative number and phenotypes between groups. Numbers in each dot plot indicate the percentage of double-positive cells in (B) CD8-gated or (C) CD4-gated BILs. One of two representative experiments with similar results is shown.

BILs were isolated from C57BL/6 mice bearing i.c. GL261 tumors that were treated with GAA peptides and either 1D11 or 13C4. Treatment with 1D11 and the GAA vaccine resulted in decreased levels of pSmad2 in CD4- or CD8-gated BILs (Figure 3A), suggesting that systemically administered 1D11 may penetrate i.c glioma, thereby inhibiting the TGF-β signaling in the tumor microenvironment.

Treatment with 1D11 results in increased infiltration of type-1 anti-GAA CTLs and decreased infiltration of Treg cells in gliomas

BILs were analyzed by flow cytometry for the presence of CD8+ CTLs versus CD25+/FoxP3+ Treg cells. GAA-vaccines alone increased the infiltration of GAA-reactive CD8+ T cells and IFN-γ-producing CD8+ T cells into the brain when compared to mice receiving control therapies, and treatment with 1D11 further increased the infiltration of GAA-reactive and IFN-γ producing CD8+ CTLs into glioma (Figure 3B). Conversely, treatment with 1D11 significantly reduced the number of CD4+/CD25+ and CD4+/FoxP3+ Treg cells in the glioma microenvironment (Figure 3C). These data indicate that the systemic 1D11 administration significantly impacts the i.c. glioma microenvironment by promoting a type-1 (i.e. IFN-γ expressing) CD8+ T cell response and reducing infiltration of immunosuppressive Treg cells.

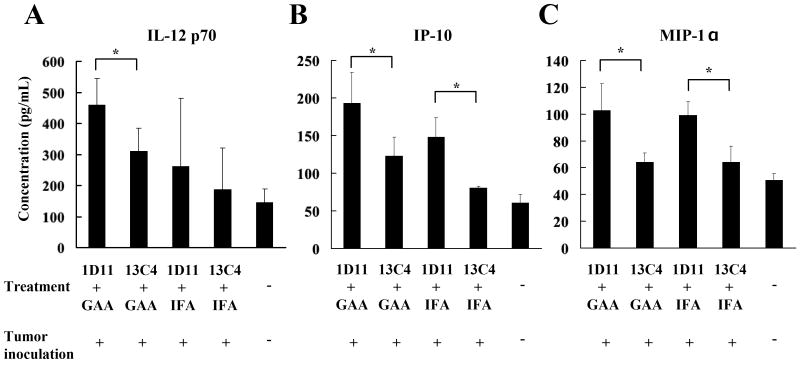

Neutralization of TGF-β with 1D11 promotes systemic type-1 cytokine/chemokine profiles

Tumor antigen–specific CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes, especially IFN-γ–producing type-1 helper T (Th1) and type-1 cytotoxic T (Tc1) cells, play crucial roles in tumor eradication (29). Since TGF-β blockade promoted type-1 function of vaccine-stimulated T cells within the i.c. tumor-microenvironment (Figure 3B, C), the cytokine/chemokine profiles in plasma samples obtained from treated glioma-bearing mice were determined. Treatment with 1D11 appears to up-regulate plasma levels of IL-12 (Figure 4A and Supplementary Figure S2), IP-10 (Figure 4B) and MIP-1α (Figure 4C) regardless of whether or not the mice were concurrently treated with GAA-vaccines. GAA-vaccines by themselves did not elevate plasma levels of these cytokines and chemokines at significant levels. Although IFN-γ was up-regulated in CD8+ BILs derived from mice receiving the combination therapy (Figure 3B), measurable levels of IFN-γ were not detected in the plasma samples from these mice (data not shown). Nevertheless, these results suggest that neutralization of TGF-β may promote type-1 cytokine/chemokine production profiles systemically in the glioma-bearing mice, thereby inducing a strong antitumor immunity.

Figure 4. Neutralization of TGF-β with 1D11 promotes plasma levels of type-1 cytokine/chemokines.

Peripheral blood was collected from treated glioma-bearing mice on day 24, and plasma levels of IL-12 p70 (A), IP-10 (B), and MIP-1α (C) were measured by ELISA (A and B) or Luminex analyses (C). For A-C, values represent the mean ± SD of samples from three mice per group. *, p < 0.05 for each of indicated comparisons.

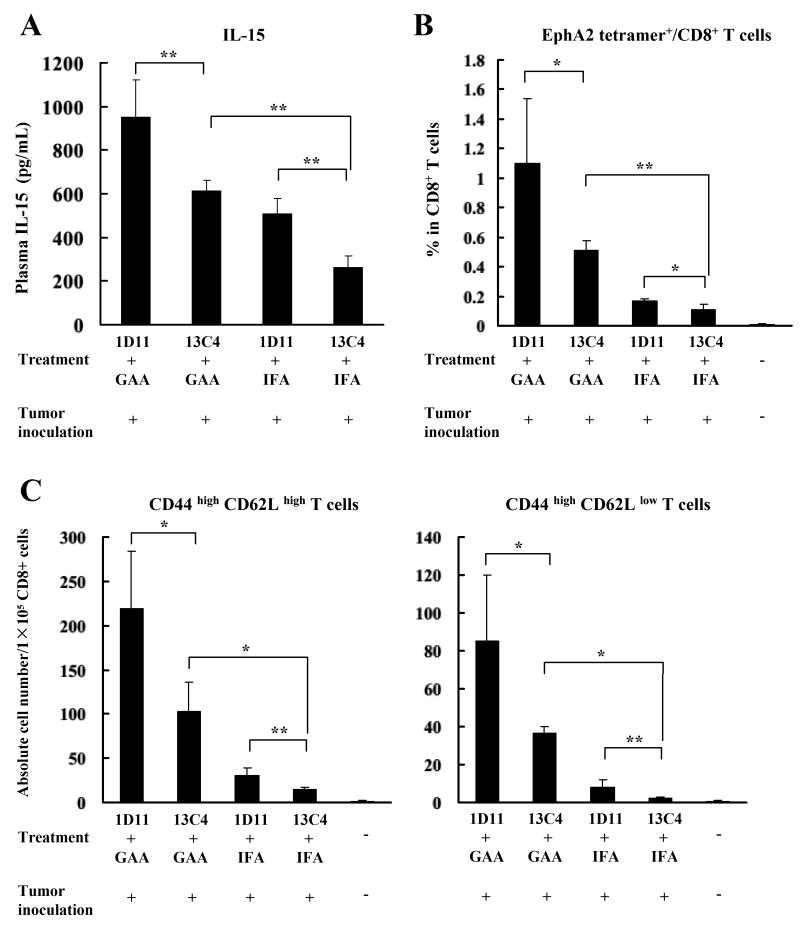

Neutralization of TGF-β with 1D11 promotes the persistence of GAA-reactive CD8+ T cells in association with systemically up-regulated IL-15

IL-15 has shown to be essential for primary expansion and generation of memory CD8+ T cells in vivo (30). Therefore the possibility that neutralization of TGF-β by 1D11 could improve the efficacy of GAA-vaccines associated with systemic up-regulation of IL-15 and the persistence of antigen-specific memory CD8+ T cells was evaluated. Plasma and SPCs were harvested from GL261 glioma-bearing mice on day 35 after the tumor inoculation (12 days following the last vaccination). Administration of GAA vaccines significantly elevated plasma levels of IL-15 compared to mice treated with IFA, and the addition of 1D11 further enhanced the circulating levels of IL-15 (Figure 5A).

Figure 5. Elevated plasma IL-15 levels are associated with increased GAA-reactive CD8+ T cells in mice treated with 1D11 and GAA-vaccines.

On day 35, peripheral blood samples and SPCs were collected from glioma-bearing treated mice. A, plasma IL-15 levels were evaluated by ELISA. B and C, (B) proportions of EphA2671-679 tetramer+/CD8+ cells in lymphocyte-gated CD8+ cells, and (C) absolute numbers of EphA2671-679 tetramer+/CD8+/CD44high/CD62Lhigh (central memory) or EphA2671-679 tetramer+/CD8+/CD44high/CD62Llow (effector memory) cells per 1×105 SPCs were analyzed by flow cytometric analyses. For A-C, the results represent the mean ± SD of samples from three mice per group. *, p < 0.05 and **, p < 0.01 for indicated comparisons.

Next flow cytometry was used to characterize the GAA-specific effector/memory CD8+ T cell phenotype of SPCs derived from the glioma-bearing treated mice. With regard to proportions in CD8+ cells, 1D11 treatment alone slightly but significantly increased the proportion of EphA2671-679-reactive/CD8+ cells compared to controls, as did GAA-vaccines alone though to a stronger degree (Figure 5B). The combination of GAA-vaccines and 1D11 further enhanced the frequency of these cells. The same effects were observed in absolute numbers of the central memory cell subset (CD44high and CD62Lhigh) and the effector memory cell subset (CD44high and CD62Llow) (Figure 5C). Although the short survival time of glioma-bearing mice did not allow for evaluation of the development of memory cells with longer observation periods, these data suggest that neutralization of TGF-β with 1D11 promotes persistence of vaccine-induced GAA-specific effector and central/effector memory CD8+ T cells in hosts associated with up-regulation of plasma IL-15.

Discussion

In the current study, the focus was on the development of combinational strategies using anti-TGF-β mAb with GAA peptide-based vaccines for glioma immunotherapy, and evaluation of immune mechanisms of action underlying the therapeutic effect of this combination regimen.

Cancer vaccines elicit a clinical benefit by catalyzing a number of critical events including: 1) systemic induction of antigen-specific effector and memory CTL responses; 2) traffic of the effector cells to the tumor site; and 3) the execution of anti-tumor effects by the tumor-infiltrating effector cells. In this study neutralization of TGF-β with a TGF-β mAb improved the therapeutic efficacy of GAA vaccines (Figure 1) by improving both systemic induction of GAA-specific CTL responses (Figure 2) and homing of GAA-reactive and IFN-γ producing CD8+ T cells into i.c. gliomas (Figure 3B).

Recent studies have suggested that production of TGF-β by gliomas may have a significant role in the induction of glioma-associated Treg cells (31, 32). In a separate study with a non-CNS tumor model, 1D11 has been shown to inhibit tumor-induced conversion of naïve CD4+CD25- T cells into CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ Treg cells (33). In the current study, systemic administration of 1D11 reduced TGF-β levels and Treg cells within the i.c. glioma microenvironment (Figure 3). Furthermore, inhibition of Smad2-mediated signaling in BIL in the tumor microenvironment suggests that, in addition to its systemic effects, i.p. administration of 1D11 may directly inhibit the pro-tumorigenic effects of TGF-β in the glioma microenvironment. With regard to the cell types producing TGF-β, GL261 glioma cells cultured in vitro produce active TGF-β as demonstrated by ELISA and cell-based assays (Supplementary Figure S1). Recently, a study by Umemura et al. (34) demonstrated that the major source of TGF-β in the i.c. GL261 glioma model is likely to be glioma-infiltrating myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) rather than GL261 glioma cells. Given the potential role of MDSC-derived TGF-β in gliomas, it would be intriguing to evaluate the effects of 1D11 treatment on MDSCs in future studies.

Neutralization of TGF-β with 1D11 promoted systemic type-1 immunity as evidenced by increased IFN-γ expressing CD8+ T cells in BILs and up-regulated plasma levels of IL-12 and IP-10. TGF-β has been shown to down-regulate DC-derived IL-12 (35), which is a potent inducer of IFN-γ producing Th1 cells (36). Moreover, TGF-β contributes to the shift toward a type 2 helper T cell (Th2) responses through direct and IL-10-mediated pathways and dampens the Tc1 population in tumor-bearing mice (37). These data suggest that treatment with 1D11 in the current study may have triggered type-1 cytokine/chemokine production cascades by promoting IL-12 production from antigen-presenting cells in glioma-bearing hosts. Although macrophage- or DC-derived MIP-1α is crucial in controlling leukocyte activation and recruitment of Th1 cells into the tissues at inflammatory sites (38), it remains to be determined how blockade of TGF-β promotes production of the Th1 chemokine MIP-1α.

TGF-β blockade by 1D11 also increased the number of GAA-specific central/effector memory CD8+ T cells, with a concomitant elevation in IL-15 levels (Figure 5). One of the mechanisms by which TGF-β negatively regulates CD8+ memory T-cell homeostasis is by opposing the positive effects of IL-15, which is involved in primary expansion of antigen-specific memory CD8+ T cells (30). TGF-β has been shown to counteract IL-15 by modulating expression of the β-chain of the IL-15 receptor (39) and it is hypothesized that TGF-β neutralization in these studies counteracted TGF-β-mediated suppression of IL-15Rβ resulting in elevated systemic IL-15. Central memory CD8+ T cells confer efficient and persistent antitumor immunity in preclinical tumor models (40) and TGF-β inhibition may have contributed to the up-regulation of GAA-specific central/effector memory CD8+ T cells in GL261-bearing mice, thereby improving the therapeutic efficacy of GAA-vaccines. Future studies evaluating the blockade of IL-15 (e.g., by use of IL-15 specific blocking mAb or IL-15 receptor deficient mice) would directly determine the significance of IL-15 induction to the observed therapeutic effect.

It has been well documented that overexpression of TGF-β by gliomas contributes to systemic immunosuppression and may be a major factor responsible for the failure of current immunotherapy strategies (13, 14, 41). Therefore, TGF-β neutralization might result in reduced tumor-induced immunosuppression and enhanced immunotherapeutic modulation. Indeed, specific blockade of TGF-β expression (42), signaling (16, 18) and ex vivo blockade by Ab (43) have all been shown to result in a beneficial effect on lymphocyte function and have resulted in enhanced immune responses in a variety of models, including glioma. With regard to the use of 1D11 in previous studies, 1D11 treatment reduced the number of lung metastases in a mouse metastatic breast cancer model (44), suppressed tumor growth through down-regulation of IL-17 in tumor cells (45), and reduced tumor burden in a renal cell cancer model through inhibiting tumor conversion of naïve CD4+CD25- T cells into CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ Treg cells (33). The current study is the first evaluating the effects of 1D11 in combination with vaccines targeting GAAs.

Concomitantly with our present study, Terabe et al. have studied the effects of 1D11 in combination with tumor antigen-specific vaccines in a murine TC1 s.c. lung tumor model (this referenced manuscript is concurrently submitted with our study). While their study provides unique mechanistic insights that are not addressed in our study, such as the contribution of NK-T cells, one major difference from ours is that they did not observe any significant reduction of Treg cells by 1D11 treatment. This may be at least partially due to the lower dose of 1D11 administration in their study (5 mg/kg) than that in our study (25 mg/kg), and potentially different levels of TGF-β elaboration by different tumor models. Nevertheless, both studies demonstrate therapeutic benefits of the combination approach with tumor vaccines and TGF-β blockade by 1D11.

Few studies have investigated the effect of combining TGF-β inhibition and vaccine therapy to enhance antitumor immunity. Tumor-bearing rats receiving administration of TGF-β2 antisense oligonucleotides (AONs) combined with systemic vaccination using irradiated tumor cells exhibited significantly prolonged survival compared to rats without any treatment, although little was addressed with regard to the underlying immune mechanisms in this approach (46, 47). Administration of an antibody against TGF-β (2G7) enhanced the ability of an intratumorally injected DC vaccine to inhibit the growth of established mouse breast cancer cells (48). Recent studies with an orally available TGF-β receptor I kinase inhibitor (SM16) have shown that when combined with adenovirus-based vaccines (49) or adoptive T-cell therapy (50), SM16 treatment potentiated the efficacy of both immunotherapies. The authors demonstrated that this was due to changes in the tumor microenvironment, including an increase in anti-tumor CTLs, type-1 cytokines and chemokines, and endothelial adhesion molecules with a decrease in arginase mRNA expression. Although their studies and our current study commonly demonstrate the favorable alteration of tumor microenvironment by systemic TGF-β blockade, novelty of our current study includes the demonstration of decreased CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ Treg cells as well as increased IFN-γ producing CD8+ T cells within the CNS tumor microenvironment.

Although all these studies point to the significance of developing clinically applicable TGF-β–blockade strategies in combination with other forms of immunotherapy, our current study has identified a novel mechanism by which 1D11 treatment induces potent and persistent type-1 adaptive anti-glioma immunity in combination with GAA-vaccines, providing a strong basis for developing novel therapeutic strategies that combine immunotherapy with TGF-β neutralization in the treatment of glioma.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

the National Institutes of Health [1R01NS055140 to H.O., 2P01 NS40923 to H.O., 1P01 CA100327 to H.O.], the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation and James S. McDonnell Foundation [220020036 to H.O.], and the Walter L. Copeland Fund of The Pittsburgh Foundation [D2007-0614 to R.U.]. University of Pittsburgh has a Cooperative Research and Development Agreement with Genzyme Corporation, Framingham, Massachusetts.

Footnotes

Translational Relevance: Overexpression of TGF-β by gliomas contributes to systemic immunosuppression and may be a major factor limiting the efficacy of current immunotherapy strategies. This study demonstrates that systemic administration of anti-TGF-β antibody induces a dynamic change of the immunological environment of glioma-bearing mice and improves the efficacy of vaccinations against glioma-associated antigens (GAAs). Neutralization of TGF-β led to promotion of vaccine-induced type-1 adaptive immune response systemically and reduction of regulatory T cells in the tumor. The current study is the first to evaluate the effects of neutralizing TGF-β in combination with vaccines targeting GAAs in a syngeneic murine glioma model. Given our experience conducting clinical trials of GAA-targeted vaccines in glioma patients, these data provide support for development of vaccine clinical trials in combination with a monoclonal antibody against human TGF-β.

References

- 1.Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, Weller M, Fisher B, Taphoorn MJ, et al. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:987–996. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Selznick LA, Shamji MF, Fecci P, Gromeier M, Friedman AH, Sampson J. Molecular strategies for the treatment of malignant glioma--genes, viruses, and vaccines. Neurosurg Rev. 2008;31:141–155. doi: 10.1007/s10143-008-0121-0. discussion 155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eguchi J, Hatano M, Nishimura F, Zhu X, Dusak JE, Sato H, et al. Identification of interleukin-13 receptor alpha2 peptide analogues capable of inducing improved antiglioma CTL responses. Cancer Res. 2006;66:5883–5891. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hatano M, Kuwashima N, Tatsumi T, Dusak JE, Nishimura F, Reilly KM, et al. Vaccination with EphA2-derived T cell-epitopes promotes immunity against both EphA2-expressing and EphA2-negative tumors. J Transl Med. 2004;2:40. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-2-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ueda R, Kinoshita E, Ito R, Kawase T, Kawakami Y, Toda M. Induction of protective and therapeutic antitumor immunity by a DNA vaccine with a glioma antigen, SOX6. Int J Cancer. 2008;122:2274–2279. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Okada H, Kohanbash G, Zhu X, Kastenhuber ER, Hoji A, Ueda R, et al. Immunotherapeutic approaches for glioma. Crit Rev Immunol. 2009;29:1–42. doi: 10.1615/critrevimmunol.v29.i1.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li MO, Sanjabi S, Flavell RA. Transforming growth factor-beta controls development, homeostasis, and tolerance of T cells by regulatory T cell-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Immunity. 2006;25:455–471. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rook AH, Kehrl JH, Wakefield LM, Roberts AB, Sporn MB, Burlington DB, et al. Effects of transforming growth factor beta on the functions of natural killer cells: depressed cytolytic activity and blunting of interferon responsiveness. J Immunol. 1986;136:3916–3920. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thomas DA, Massague J. TGF-beta directly targets cytotoxic T cell functions during tumor evasion of immune surveillance. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:369–380. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ranges GE, Figari IS, Espevik T, Palladino MA., Jr Inhibition of cytotoxic T cell development by transforming growth factor beta and reversal by recombinant tumor necrosis factor alpha. J Exp Med. 1987;166:991–998. doi: 10.1084/jem.166.4.991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen ML, Pittet MJ, Gorelik L, Flavell RA, Weissleder R, von Boehmer H, et al. Regulatory T cells suppress tumor-specific CD8 T cell cytotoxicity through TGF-beta signals in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:419–424. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408197102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elliott RL, Blobe GC. Role of transforming growth factor Beta in human cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2078–2093. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bodmer S, Strommer K, Frei K, Siepl C, de Tribolet N, Heid I, et al. Immunosuppression and transforming growth factor-beta in glioblastoma. Preferential production of transforming growth factor-beta 2. J Immunol. 1989;143:3222–3229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Constam DB, Philipp J, Malipiero UV, ten Dijke P, Schachner M, Fontana A. Differential expression of transforming growth factor-beta 1, -beta 2, and -beta 3 by glioblastoma cells, astrocytes, and microglia. J Immunol. 1992;148:1404–1410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liau LM, Prins RM, Kiertscher SM, Odesa SK, Kremen TJ, Giovannone AJ, et al. Dendritic cell vaccination in glioblastoma patients induces systemic and intracranial T-cell responses modulated by the local central nervous system tumor microenvironment. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:5515–5525. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gorelik L, Flavell RA. Immune-mediated eradication of tumors through the blockade of transforming growth factor-beta signaling in T cells. Nat Med. 2001;7:1118–1122. doi: 10.1038/nm1001-1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suzuki E, Kim S, Cheung HK, Corbley MJ, Zhang X, Sun L, et al. A novel small-molecule inhibitor of transforming growth factor beta type I receptor kinase (SM16) inhibits murine mesothelioma tumor growth in vivo and prevents tumor recurrence after surgical resection. Cancer Res. 2007;67:2351–2359. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Uhl M, Aulwurm S, Wischhusen J, Weiler M, Ma JY, Almirez R, et al. SD-208, a novel transforming growth factor beta receptor I kinase inhibitor, inhibits growth and invasiveness and enhances immunogenicity of murine and human glioma cells in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7954–7961. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prins RM, Odesa SK, Liau LM. Immunotherapeutic targeting of shared melanoma-associated antigens in a murine glioma model. Cancer Res. 2003;63:8487–8491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iizuka Y, Kojima H, Kobata T, Kawase T, Kawakami Y, Toda M. Identification of a glioma antigen, GARC-1, using cytotoxic T lymphocytes induced by HSV cancer vaccine. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:942–949. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dasch JR, Pace DR, Waegell W, Inenaga D, Ellingsworth L. Monoclonal antibodies recognizing transforming growth factor-beta. Bioactivity neutralization and transforming growth factor beta 2 affinity purification. J Immunol. 1989;142:1536–1541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nishimura F, Dusak JE, Eguchi J, Zhu X, Gambotto A, Storkus WJ, et al. Adoptive transfer of type 1 CTL mediates effective anti-central nervous system tumor response: critical roles of IFN-inducible protein-10. Cancer Res. 2006;66:4478–4487. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sasaki K, Zhu X, Vasquez C, Nishimura F, Dusak JE, Huang J, et al. Preferential expression of very late antigen-4 on type 1 CTL cells plays a critical role in trafficking into central nervous system tumors. Cancer Res. 2007;67:6451–6458. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhu X, Nishimura F, Sasaki K, Fujita M, Dusak JE, Eguchi J, et al. Toll like receptor-3 ligand poly-ICLC promotes the efficacy of peripheral vaccinations with tumor antigen-derived peptide epitopes in murine CNS tumor models. J Transl Med. 2007;5:10. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-5-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fujita M, Zhu X, Sasaki K, Ueda R, Low KL, Pollack IF, et al. Inhibition of STAT3 promotes the efficacy of adoptive transfer therapy using type-1 CTLs by modulation of the immunological microenvironment in a murine intracranial glioma. J Immunol. 2008;180:2089–2098. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.4.2089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gorelik E, Landsittel DP, Marrangoni AM, Modugno F, Velikokhatnaya L, Winans MT, et al. Multiplexed immunobead-based cytokine profiling for early detection of ovarian cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:981–987. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leivonen SK, Kahari VM. Transforming growth factor-beta signaling in cancer invasion and metastasis. Int J Cancer. 2007;121:2119–2124. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Feng XH, Derynck R. Specificity and versatility in tgf-beta signaling through Smads. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2005;21:659–693. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.21.022404.142018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Trinchieri G. Interleukin-12 and the regulation of innate resistance and adaptive immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:133–146. doi: 10.1038/nri1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schluns KS, Williams K, Ma A, Zheng XX, Lefrancois L. Cutting edge: requirement for IL-15 in the generation of primary and memory antigen-specific CD8 T cells. J Immunol. 2002;168:4827–4831. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.10.4827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fecci PE, Mitchell DA, Whitesides JF, Xie W, Friedman AH, Archer GE, et al. Increased regulatory T-cell fraction amidst a diminished CD4 compartment explains cellular immune defects in patients with malignant glioma. Cancer Res. 2006;66:3294–3302. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grauer OM, Nierkens S, Bennink E, Toonen LW, Boon L, Wesseling P, et al. CD4+FoxP3+ regulatory T cells gradually accumulate in gliomas during tumor growth and efficiently suppress antiglioma immune responses in vivo. Int J Cancer. 2007;121:95–105. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu VC, Wong LY, Jang T, Shah AH, Park I, Yang X, et al. Tumor evasion of the immune system by converting CD4+CD25- T cells into CD4+CD25+ T regulatory cells: role of tumor-derived TGF-beta. J Immunol. 2007;178:2883–2892. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.5.2883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Umemura N, Saio M, Suwa T, Kitoh Y, Bai J, Nonaka K, et al. Tumor-infiltrating myeloid-derived suppressor cells are pleiotropic-inflamed monocytes/macrophages that bear M1- and M2-type characteristics. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;83:1136–1144. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0907611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pardoux C, Ma X, Gobert S, Pellegrini S, Mayeux P, Gay F, et al. Downregulation of interleukin-12 (IL-12) responsiveness in human T cells by transforming growth factor-beta: relationship with IL-12 signaling. Blood. 1999;93:1448–1455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Trinchieri G. Interleukin-12: a cytokine produced by antigen-presenting cells with immunoregulatory functions in the generation of T-helper cells type 1 and cytotoxic lymphocytes. Blood. 1994;84:4008–4027. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maeda H, Shiraishi A. TGF-beta contributes to the shift toward Th2-type responses through direct and IL-10-mediated pathways in tumor-bearing mice. J Immunol. 1996;156:73–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Loetscher P, Uguccioni M, Bordoli L, Baggiolini M, Moser B, Chizzolini C, et al. CCR5 is characteristic of Th1 lymphocytes. Nature. 1998;391:344–345. doi: 10.1038/34814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lucas PJ, Kim SJ, Mackall CL, Telford WG, Chu YW, Hakim FT, et al. Dysregulation of IL-15-mediated T-cell homeostasis in TGF-beta dominant-negative receptor transgenic mice. Blood. 2006;108:2789–2795. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-025676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Klebanoff CA, Gattinoni L, Torabi-Parizi P, Kerstann K, Cardones AR, Finkelstein SE, et al. Central memory self/tumor-reactive CD8+ T cells confer superior antitumor immunity compared with effector memory T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:9571–9576. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503726102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Maxwell M, Galanopoulos T, Neville-Golden J, Antoniades HN. Effect of the expression of transforming growth factor-beta 2 in primary human glioblastomas on immunosuppression and loss of immune surveillance. J Neurosurg. 1992;76:799–804. doi: 10.3171/jns.1992.76.5.0799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jachimczak P, Bogdahn U, Schneider J, Behl C, Meixensberger J, Apfel R, et al. The effect of transforming growth factor-beta 2-specific phosphorothioate-anti-sense oligodeoxynucleotides in reversing cellular immunosuppression in malignant glioma. J Neurosurg. 1993;78:944–951. doi: 10.3171/jns.1993.78.6.0944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ruffini PA, Rivoltini L, Silvani A, Boiardi A, Parmiani G. Factors, including transforming growth factor beta, released in the glioblastoma residual cavity, impair activity of adherent lymphokine-activated killer cells. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1993;36:409–416. doi: 10.1007/BF01742258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nam JS, Terabe M, Mamura M, Kang MJ, Chae H, Stuelten C, et al. An anti-transforming growth factor beta antibody suppresses metastasis via cooperative effects on multiple cell compartments. Cancer Res. 2008;68:3835–3843. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nam JS, Terabe M, Kang MJ, Chae H, Voong N, Yang YA, et al. Transforming growth factor beta subverts the immune system into directly promoting tumor growth through interleukin-17. Cancer Res. 2008;68:3915–3923. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu Y, Wang Q, Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK, Franzusoff A, Ng KY, Lillehei KO. TGF-beta2 inhibition augments the effect of tumor vaccine and improves the survival of animals with pre-established brain tumors. J Neurooncol. 2007;81:149–162. doi: 10.1007/s11060-006-9222-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schneider T, Becker A, Ringe K, Reinhold A, Firsching R, Sabel BA. Brain tumor therapy by combined vaccination and antisense oligonucleotide delivery with nanoparticles. J Neuroimmunol. 2008;195:21–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2007.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kobie JJ, Wu RS, Kurt RA, Lou S, Adelman MK, Whitesell LJ, et al. Transforming growth factor beta inhibits the antigen-presenting functions and antitumor activity of dendritic cell vaccines. Cancer Res. 2003;63:1860–1864. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kim S, Buchlis G, Fridlender ZG, Sun J, Kapoor V, Cheng G, et al. Systemic blockade of transforming growth factor-beta signaling augments the efficacy of immunogene therapy. Cancer Res. 2008;68:10247–10256. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wallace A, Kapoor V, Sun J, Mrass P, Weninger W, Heitjan DF, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta receptor blockade augments the effectiveness of adoptive T-cell therapy of established solid cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:3966–3974. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.