Abstract

We undertook this qualitative study to examine young people's understandings of the physical and social landscape of the downtown drug scene in Vancouver, Canada. In-depth interviews were conducted with 38 young people ranging from 16 to 26 years of age. Using the concept of symbolic violence, we describe how one downtown neighborhood in particular powerfully symbolizes ‘risk’ among local youth, and how the idea of this neighborhood (and what happens when young people go there) informs experiences of marginalization in society's hierarchies. We also discuss the complex role played by social networks in transcending the geographical and conceptual boundaries between distinct downtown drug-using neighborhoods. Finally, we emphasize that young people's spatial tactics within this downtown landscape – the everyday movements they employ in order to maximize their safety – must be understood in the context of everyday violence and profound social suffering.

Keywords: youth, place, drug scenes, symbolic violence, spatial tactics

Introduction

Popular imaginings of young, homeless drug users are often informed by their use of public space. Whether because they are viewed as children in need of protection or criminals bent on destruction, drug-using, street-dwelling young people are overwhelmingly considered ‘out-of-place’ in the public spaces of urban centers (Scheper-Hughes and Hoffman, 1998, Hecht, 1998, Mitchell, 2003). Accordingly, public health and policy efforts to address the ‘street youth problem’ have consistently aimed to exclude, relocate or forcibly remove ‘deviant’ youth from public space (Caldeira, 2000, Sandberg and Pedersen, 2008, Connell, 2003, Moore, 2004b). These strategies largely ignore the contextual factors – such as neighborhood deprivation and disadvantage, and ongoing experiences of social and economic suffering among youth (Rhodes et al., 2005) – that operate to rapidly isolate and push them towards harmful drug use practices and homelessness, until it becomes difficult or impossible for them to avoid ‘risking risk’ (Mayock, 2005, Lovell, 2002, Mitchell, 2003).

However, there is a growing body of work that focuses on how young people understand and experience place in their everyday lives (Gigengack, 2000, Beazley, 2002, Rhodes et al., 2007), where place is defined as the intersection between social and physical spaces (Massey, 1994). This research has illustrated that rather than being somehow ‘placeless,’ young people living on the margins of social and physical spaces may possess a heightened understanding of and attachment to the landscapes they inhabit. Survival on the streets often means navigating the ‘geographies of power’ (Caldeira, 2000) that limit these young people's uses of public space, and enacting ‘geographies of resistance’ (Beazley, 2002) in response to institutionalized spatial marginalization. A focus on how young people experience, understand and navigate urban space – how they may be simultaneously in-place as well as out-of-place on the streets of urban centers (Moyer, 2004, Scheper-Hughes and Hoffman, 1998) – has highlighted the problematic institutions and structures that contribute to their continued marginalization, as well as the strategies or spatial tactics (De Certeau, 1984) that they employ in order to appropriate public space according to their own needs, priorities and desires (Moyer, 2004, Eugene, 1999). For example, work with street-entrenched youth in Indonesia has illustrated how state ideological discourse about family values and gender roles has been used to justify ‘clean up’ efforts aimed at forcibly removing young people – and particularly young women – from the streets of Yogyakarta (Beazley, 2002). However, this research also illustrates the ways in which these young women have succeeded in rejecting conventional gender roles through spatial tactics (e.g. occupying a city park) aimed at carving out relatively safe, ‘girl-only’ geographical niches in the city center. Similarly, work from Tanzania has discussed the disjuncture between a state-sponsored project of modernization and the presence of hundreds of young men living and working on the streets of Dar es Salaam, which results in the frequent arrest of these informal street-based entrepreneurs and the destruction of their make-shift street stalls. At the same time, this research has shown how young people's appropriation of ‘nowhere places’ (such as street corners, abandoned lots or stretches of roadside) in the pursuit of financial gain in fact constitutes a spatial tactic aimed at securing a place in the very same modernizing project endorsed by the state (Moyer, 2004).

In downtown Vancouver, Canada, a growing number of street-entrenched and drug-using youth have emerged in a residential and business centre of the city known as the Downtown South. While it is difficult to enumerate this highly transient population (The McCreary Centre Society, 2007), a local youth shelter reports that between 500 and 1000 youth are without housing each night in the Greater Vancouver area (Covenant House Vancouver, 2009). In addition to lacking shelter, intensive drug use – including the use of crystal methamphetamine, heroin, cocaine and crack – and alarming rates of HIV and hepatitis C infection have also been documented in this population (Lloyd-Smith et al., 2008, Werb et al., 2008, Wood et al., 2008, Miller et al., 2005). Although various youth services are now situated in the Downtown South (e.g., clinics and drop-in centers), decision makers and advocacy groups continue to struggle to address the ‘street youth problem’ in this setting (The McCreary Centre Society, 2002). To date, enforcement, arrest and removal of youth from public spaces have been the primary strategies aimed at this population, with a particular focus on ‘cracking down on’ the local drug scene.

Drug scenes have been described as inner-city areas characterized by high concentrations of drug users and drug dealing within a specific geographical area (Curtis and Wendel, 2000, Hough and Natarajan, 2000). These places vary considerably according to a number of factors, including the types of drugs available, who controls the sale of illicit substances, the specific locales in which drugs are sold and used, as well as the history of particular drug-use settings (Bourgois, 1996, Maher, 1997). Beyond drug procurement and dealing activities, everyday practices associated with securing basic necessities (e.g., meals, clean clothes, showers) as well as wider patterns of income generation activities are also embedded in the socio-spatial networks of these locales (Bourgois, 1995, Maher, 1997). As such, drug scenes powerfully shape drug use practices, the nature of social interactions between young people and range of social actors (including peers, older drug users, informal ‘street’ employers, police and service providers), as well as the formation of identity constructed and performed through spatial practices (De Certeau, 1984, Dovey et al., 2001, Butler, 1990, Rhodes et al., 2007). Equally, these places are shaped by the practices and human interactions that take place within them.

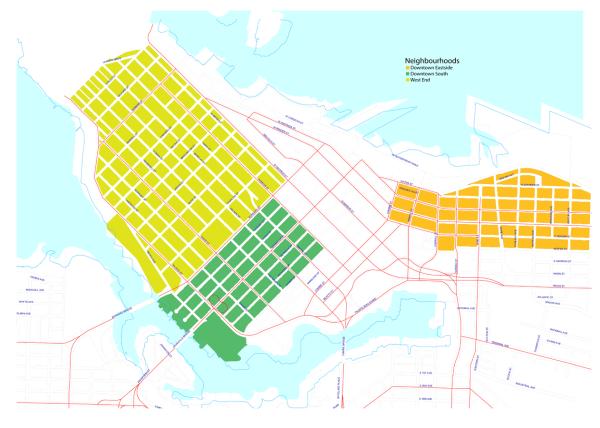

In downtown Vancouver, the local drug scene (referred to by many youth as simply ‘down here’) is primarily comprised of two distinct neighborhoods: the Downtown South1 and the Downtown Eastside. Although these areas are geographically adjacent (within 20 to 30 minutes walking distance of each other), they are generally conceptualized as two distinct urban neighborhoods. Among the general public, the boundary that exists between them is largely one of differential affluence; while the Downtown Eastside is widely recognized as Canada's poorest and most crime-ridden urban postal code (Strathdee et al., 1997, Wood et al., 2003), the Downtown South is a residential and entertainment district characterized by both high-and (limited) low-income housing and numerous thriving businesses. The respective drug-using populations within these neighborhoods are also distinct (although overlap exists); while the Downtown South is characterized by high rates of crystal methamphetamine sales and use primarily among youth (Bungay et al., 2006), the Downtown Eastside is characterized by a long-standing and well-established trade in crack cocaine, cocaine and heroin (Wood and Kerr, 2006). Furthermore, although the Downtown Eastside can accurately be characterized as a more ‘open’ drug scene in comparison to that of the Downtown South, in reality, a wide range of illicit substances are easily available on the streets of both locales. Both neighborhoods are characterized by thriving ‘shadow economies’ largely propelled by sex work activities, drug dealing and the exchange of stolen goods. The Downtown Eastside in particular has been subjected to intensive enforcement initiatives in recent years (Small et al., 2006), although police activities are also ongoing in the Downtown South (The McCreary Centre Society, 2002).

We undertook the present study in order to explore how youth who are currently ‘street-entrenched’ understand the physical and social landscape of the downtown drug scene in Vancouver's urban core. Given the geographical proximity of the Downtown South – a frequent destination for young people ‘at-risk’ – to the Downtown Eastside, there is a need to understand how young people experience and navigate these locales. Indeed, our observations indicate that many youth move frequently between the Downtown South and Downtown Eastside neighborhoods, whether on foot or via public bus (which they can often ride for free depending on the disposition of the driver). To date, however, the majority of research looking at the relationship between drug scene involvement and ‘risk’ among young people has largely focused on geographically confined inner-city areas characterized by ubiquitous ‘open’ drug use and crime – such as Vancouver's Downtown Eastside neighborhood (Bourgois et al., 2004, Bourgois, 1996, Small et al., 2006, Small et al., 2005a, Small et al., 2005b, Maher, 1997). The intersection between experiences of place and experiences of risk and harm among young people existing outside of or transcending the boundaries of these inner-city communities remains less well understood. Furthermore, the ways in which young people's ‘risk trajectories’ – the sequences of transitions experienced by young people in relation to drug use and risk over time (Hser et al., 2007, Elder, 1985) – are shaped by geographical transitions (whether across countries, regions or adjacent drug-using neighborhoods) have yet to be explored in-depth. Finally, a focus on the meanings attached to places – and how these meanings inform spatial practices – has important implications for the development of appropriate interventions for youth who experience significant vulnerability while trying to make their homes in Vancouver's urban core.

Methods

In order to explore how young people conceptualized the Downtown South and Downtown Eastside neighborhoods (as well as the relationship between them), we drew upon data from 38 in-depth individual interviews conducted from May to October 2008, as well as ongoing ethnographic fieldwork (e.g., observations and informal conversations with youth) conducted in both the Downtown South and Downtown Eastside.

Interviewees were recruited from within the At-Risk Youth Study (ARYS) cohort, a prospective cohort of drug-using and street-involved youth that has been described in detail elsewhere (Wood et al., 2006). Eligibility criteria for this study include being between the ages of 14 and 26 years and self-reported use of illicit drugs other than or in addition to marijuana in the past thirty days. A subgroup of the cohort was selected to complete qualitative interviews. Sampling was largely opportunistic, but aimed to attain variation in gender, ethnicity, age, and length of time having lived within the downtown Vancouver drug scene.

Interviews were undertaken by three trained interviewers (one male and two female) and facilitated through the use of a topic guide encouraging broad discussion of experiences and understandings of the Downtown South and Downtown Eastside neighborhoods. In particular, we asked youth to tell us about ‘safe’ and ‘un-safe’ places in the city, and probed for how these experiences might be shaped by gender as well as a young person's social position more generally. We use the terms safety and un-safety in order to distance ourselves from risk factor analyses that focus exclusively on the problematic characteristics of ‘risky places,’ ‘risky people’ and ‘risky practices’ (Shoveller and Johnson, 2006), and to underscore a commitment to young people's perspectives on staying safe ‘on the streets’ – a phase that refers to numerous indoor and outdoor locales that go well beyond stretches of sidewalk. The concept of social positioning draws our attention to how young people see themselves in relation to the places they inhabit. It highlights the ways in which young people are able (or unable) to access and deploy resources in comparison to other social actors, illustrating how youth may be either privileged or disadvantaged within social-structural and physical environments.2

Interviews lasted between 30 and 120 minutes, were tape-recorded, transcribed verbatim and checked for accuracy. All participants provided informed consent, and the study was undertaken with ethical approval granted by the Providence Healthcare/University of British Columbia Research Ethics Board. Participants received a twenty-dollar honorarium. There were no refusals of the invitation to participate in the interview, and no dropouts (i.e. the participant chooses to decline participation in the study) occurred during the interview process. Data collection and analyses occurred concurrently and via ongoing engagement with participants, in order to continually re-evaluate the validity of research findings. While remaining cognizant of confidentiality issues (many of the participants of this study knew each other and it was therefore important to emphasize that what one person said in an interview would under no circumstances be repeated to another participant), evolving interpretations of the data were discussed with participants, both informally with those who had already been interviewed, and more formally in subsequent interviews. This process was used to inform the focus and direction of subsequent interviews (for example, through the addition of new questions and probes). In addition, the research team discussed the content of the interviews throughout the data collection and analysis processes, informing the development and refinement of a coding scheme for partitioning the data categorically. Interview data was initially coded based on key themes; substantive codes were then applied to categories/themes based on the initial codes. ATLAS.TI software was used to manage the coded data.

Results

Participants ranged from 16 to 26 years of age and included 18 women, 18 men and 2 transgender individuals. Sixty-seven percent of study participants were Caucasian, 28 percent self-identified as being of Aboriginal descent, and 5 percent were African Canadian. Half of interview participants reported being homeless at the time of the study, and the majority had experienced homelessness at some time over the course of their involvement with the local drug scene. The majority of participants reported that they had at one time engaged in or were currently engaging in drug use that they defined as problematic – including intensive (i.e. multiple times per day) crack cocaine, crystal methamphetamine and/or heroin use. Furthermore, approximately half of young people said they had been involved in these forms of intensive drug use within the local scene for more than 3 years. In sum, the majority of the young people reported being significantly entrenched in the downtown drug scene – in other words, they were largely consumed by the daily project of ‘staying safe on the streets’ in the context of homelessness, chronic poverty, and involvement in potentially harmful drug use practices and income generation activities, including drug dealing and sex work.

Evading danger: The Downtown Eastside as symbolic representation

Our results illustrate that, among study participants, a number of the perceived dangers that accompany prolonged drug scene involvement – including intensive involvement in the most problematic forms of drug use, risk of HIV and engagement in exploitative sex work – were all understood to be situated in Vancouver's Downtown Eastside neighborhood. Among youth, this neighborhood powerfully symbolized un-safety and the inevitable physical, psychological and moral ‘demise’ of young people who ‘end up down there.’ Although participants acknowledged that the these dangers are by no means exclusive to the Downtown Eastside, and that dangers beyond these exist within the local scene (for example, the dangers that accompany drug dealing activities), participants consistently differentiated the Downtown Eastside from other urban locales according to a number of intersecting aspects of place.

Firstly, the Downtown Eastside was strongly differentiated from the Downtown South neighborhood in particular in terms of the types of drugs being used in each locale. Consistent with our earlier description, participants frequently described a crystal methamphetamine scene situated primarily in the Downtown South neighborhood, which could be contrasted with a crack cocaine and injection cocaine and heroin scene situated in the Downtown Eastside. Interestingly, this separation was often expressed through references to participants' own spatial practices. Transitions in drug use (for example, from crystal methamphetamine to crack cocaine or heroin use) were frequently associated with a geographical transition from elsewhere in the city to the Downtown Eastside. Such geographical/drug use transitions oftentimes carried a heavy moral judgment, as participants consistently equated ‘problematic drug use’ with frequent crack cocaine smoking and/or intravenous heroin use:

I: What sort of areas [are you spending time in at the moment]?

R: Downtown Eastside, depending on how stupid I start to get with my craving for rock [crack cocaine]. I do a hoot [inhalation] and then I crave. Otherwise, if I do my speed [crystal methamphetamine], I'm usually here [in the Downtown South]. (Male Participant 7)

Secondly, participants articulated a negative association between the Downtown Eastside neighborhood and intensive heroin and crack cocaine use, again connecting their own experiences of accelerating and ‘out of control’ drug use with a geographical transition from other areas of the city to the streets of the Downtown Eastside:

P: I just started using [heroin] heavily again … Now, I've moved on from Commercial [a district outside of the downtown core], down to Hastings [in the Downtown Eastside]. (Female Participant 37)

Thirdly, participants described the un-safety afforded by the physical environment of the Downtown Eastside. More specifically, participant accounts situated the risk of contracting HIV within the neighborhood's parks and alleyways, which they characterized as ‘littered’ with uncapped needles:

I: Are there any places that you feel are particularly unsafe?

P: Pigeon Park [in the Downtown Eastside] … ‘Cause of Blood Alley.

I: Why is that area unsafe?

P: Because there is a lot of needle usage. People don't pick up their rigs [needles]. They just leave them there without the cap on. (Female Participant 17)

Interestingly, our ethnographic observations within the Downtown Eastside tell a different story; as a result of frequent needle sweeps in the neighborhood, we have observed relatively few discarded uncapped needles in the area. Furthermore, we have observed that many drug users are aware that a needle poke rarely results in HIV infection. As such, young people's references to an ever-present threat of contracting HIV within the Downtown Eastside via a needle poke may speak more to the symbolic power of the Downtown Eastside as a signifier of unavoidable danger and disease and shameful drug-using behaviors (such as discarding used needles on the ground, ‘tweaking out,’ and ‘nodding off’), rather than to a pervasive problem that requires addressing:

P: [The Downtown Eastside] is just not nice … I don't want HIV shoved in my face. And everyone's a crackhead … I don't need to see those people scratching the fucking pebbles on the ground [i.e. ‘tweaking,’ or repetitive fidgeting with objects in the surrounding environment as a result of stimulant use], like, the guy in the park with a needle hanging out of his arm [i.e. ‘nodding off,’ or falling asleep as a result of opiate use ] … I'm sorry, I just really don't want to see that. (Female Participant 3)

Finally, participants made a clear connection between the Downtown Eastside and involvement in sex work. Moreover, this association was clearly gendered; both male and female participants emphasized that young women who frequented the Downtown Eastside were particularly vulnerable to involvement in exploitative and dangerous sex work activities (even though sex work among young men is also common within the local scene and particularly the Downtown South):

P: On Hastings [a street in the Downtown Eastside] … There are people walking like this, the ‘Hastings shuffle’ [does an imitation of someone high on crack cocaine and heroin]. A bad combination of crack and heroin, right? [It's unsafe because of] drugs and ‘cause of the men. They [pimps] prey on little girls … It's recruiting season [for the local sex trade] right now. Warn girls to stay away. (Female Participant 15)

Participants expressed the belief that prolonged involvement within the open drug scene of the Downtown Eastside inevitably results in the intensive use of problematic substances such as heroin or crack cocaine. Constant proximity to drug use via the social-spatial networks of the Downtown Eastside was identified as an important factor in redefining the boundaries of acceptable drug use to include those substances that were previously morally unacceptable and ‘off limits.’ ‘Out of control’ drug use was in turn associated with a corresponding intensified need to accrue income, which participants indicated for young women in particular often meant heightened vulnerability to situations of sexual exploitation via involvement in sex work:

P: On Hastings [a street in the Downtown Eastside] … There's a lot of active drug use, out in the open. And young girls might see that, and think that it's glamorous, or they'll think it's cool, and they'll start to get into it. And then they'll have to sell themselves for basically next to nothing because they don't know any other way to make money. (Female Participant 21)

Thus, although participants acknowledged that the Downtown Eastside could present dangers to both young men and young women, and via involvement in activities beyond sex work, it seems to be the case that the Downtown Eastside neighborhood powerfully symbolizes the potential physical, psychological and moral ‘demise’ of young women in particular, and that this potential ’demise’ is closely linked to the latter's potential for involvement in sex work activities.

The idea of the Downtown Eastside – and what happens once young people make the transition to this drug-using milieu – led a number of participants to emphasize the social distance (Sandberg and Pedersen, 2008) between themselves and this ‘immoral’ space of accelerating addictions, sexual exploitation, disease and extreme violence:

P: I don't like any young person really saying their going to the Eastside. I threaten violence upon [young people who say they are going to the Downtown Eastside] all the time.

I: What are some of the bad things that happen – let's start with young women – what are some of the things that happen when young women go to the Downtown Eastside?

P: They go missing … They get pimped out … They start not caring about themselves. They start losing touch with humanity.

I: And what about young guys?

P: They learn very bad ethics. They become torture tacticians, and weird insane things. (Male Participant 2)

The above narrative and others like it indicate that social norms prohibiting involvement in the Downtown Eastside do exist among local youth. Participants identified avoidance of the Downtown Eastside as an important spatial tactic aimed at reducing harms (even if this means avoiding crucial service locations):

P: I've got a hole in my tooth that's like this big … I can see a dentist – You can go down to Hastings [in the Downtown Eastside] and get a free dental care but I'm just going to waste my time going down there, and probably end up relapsing. (Male Participant 16)

Nevertheless, existing social norms are often not successful in preventing young people's physical and social initiation into the Downtown Eastside drug-using milieu – even when violence is used as a means of persuasion. Despite an interest in creating social distance between themselves and this neighborhood, and efforts to employ spatial tactics aimed at avoiding this locale, most of the young people with whom we spoke described in graphic detail first-hand accounts of various aspects of the social and physical environment of the Downtown Eastside, indicating that a large number of them had at one time or another spent a significant amount of time ‘down there.’ Participants' wider narratives indicated that many had internalized a ‘mismatch’ between the ideal of distancing themselves from the Downtown Eastside, and a day-today reality that pushes them towards involvement in this un-safe place, whether because of a need to seek out increasingly lucrative income generation strategies (such as sex work) in the face of accelerating addictions, or the need to use increasingly harmful drugs (such as crack cocaine or heroin) in order to remedy ‘dopesickness’ and deal with the immense social suffering (Kleinman et al., 1997) that accompanies ‘life on the street.’ The result of this mismatch can be a crisis of identity and further social suffering, as young people struggle to reconcile transitions to increasingly harmful practices and places (that are themselves powerful symbolic representations of shame and demise) with personal dignity and a moral code ‘of the street’ that prohibits these transitions.

Safety and belonging in the Downtown South?

In contrast to the Downtown Eastside, a number of participants identified the Downtown South as a place of relative safety, and as such sought out more permanent residence in this area – oftentimes underneath bridges and other sheltered structures, and occasionally through the use of the area's shelters or renting a private residence. The Downtown South is where the vast majority of youth services are located, and a number of participants indicated that available services play an important role in allowing them to meet basic needs (such as showering, eating, and using the phone or internet), as well as keeping them safe from police arrest and street-related violence. However, more often participants emphasized that this area was relatively safe because their social position within this locale offered them certain advantages:

P: Around here [in the Downtown South] I feel totally safe because everybody knows me. I could be walking around here at night by myself with a stack of money on me, right, [and not get into trouble] … People know my boyfriend, and then, you know, if they [did anything to me] then they know that they would get in trouble from him. (Female Participant 9)

A young person's social position can be ‘called upon’ to provide protection from street violence; as such, it facilitates relative safety in those areas where young people ‘know people’ and have strong social connections. However, it was also frequently acknowledged by participants that social networks tied to place are also a part of what creates situations of un-safety on the streets and even within service locations. This is especially the case when social networks are called upon to ‘track someone down’ in a specific area, usually for the purposes of ‘jacking someone up’ (i.e. stealing from them) or for punishment related to altercations within romantic partnerships and/or drug dealing partnerships. As such, even service locations in the Downtown South could quickly become places that must be evaded to the detriment of other needs:

P: Basically everybody knows a couple people around here [in the Downtown South] … Like out of a group of people, five people are like, ‘Yeah, I saw that guy, aah, just like a couple of hours ago, he was on his way down to GP [a service location in the Downtown South], man. But he said he was leaving town, or something’ … So everyone'll just go to the Greyhound [a bus station near to the Downtown Eastside] … Where's he gonna' go? … Once somebody knows you … you'll be tracked down in, like, one day tops. (Male Participant 18)

As a result of being frequently ‘tracked down’ and subsequently subjected to extreme acts of violence, a number of participants indicated that the Downtown South could feel like a place from which there is ‘no escape’ (except, ironically, to streets of the Downtown Eastside):

I: Are there any places [in the Downtown South] that are particularly safe?

P: No. Everybody knows where everyone is … When I first came down here, right, this chick, she was like the same size as me. She used to intimidate me with bear spray and a knife … No matter where I went, she found me. No matter how hard I tried to run, she found me. (Female Participant 19)

Similarly, although a number of young women indicated that their boyfriends offer them some degree of protection in those places where the latter's ‘street reputations’ are particularly formidable, female participants also articulated numerous situations of un-safety that arise from these relationships in the places where their boyfriends maintain a strong drug dealing presence. Participants indicated that the loyalty demanded by romantic attachments was sometimes at odds with a lifestyle of addiction, in which a need or desire to score drugs quickly from wherever possible could outweigh a commitment to honor a boyfriend's sense of control over his girlfriend's drug use and associated drug procurement activities:

I: What can you tell me about unsafe places in the city?

P: Downtown Eastside. You always have to watch your back down there.

I: From?

P: My boyfriend. My boyfriend's friends, my boyfriend's workers [in the drug dealing business], you know. Everywhere you go, you turn and look, to make sure none of his workers see what you're doing, or hear what you're saying. (Female Participant 15)

Thus, although all of the youth with whom we spoke made a clear distinction between the Downtown Eastside and Downtown South in terms of relative safety and danger, many youth emphasized that social networks can facilitate situations of danger within and across these drug-using milieus. Interestingly, a few of the youth with whom we spoke expressed concerns that the boundaries between these once discrete neighborhoods were weakening as a result of shifting social networks, resulting in elevated risk for young people experiencing vulnerability in the Downtown South. Participants reported that police intervention in the Downtown Eastside had caused a number of ‘junkies’ and ‘crackheads’ from the Downtown Eastside to move into the Downtown South area, where they were now acting to facilitate young people's geographical transition from the relative safety of the Downtown South area to the relative danger of the Downtown Eastside:

P: [The Downtown South] has changed because the cops decided to start pushing everybody from Hastings [in the Downtown Eastside] up to Granville and Davie [in the Downtown South] … Most of the crackheads that end up down there [in the Downtown Eastside] are thirteen, fourteen years old … they started out this area [the Downtown South] … It starts out where a nice looking crackhead walks up and goes, ‘Hey!’ Starts talking to someone, eventually they'll be like, ‘Hey, you want to try something? Here, put this in your pipe.’ And you put it in your pipe, you smoke it, and it' like, ‘Ooh! Wow!’ And all of a sudden you'e down on Hastings, selling your body. (Male Participant 14)

Again, our ethnographic observations tell a somewhat different story with respect to this data. Certainly, previous work has shown that older drug users can play a role in initiating younger drug users into more harmful forms of drug use (Fuller et al., 2003, Roy et al., 2003). Moreover, aggressive policing in the Downtown Eastside has resulted in the displacement of drug using residents from that neighborhood (Wood et al., 2004). However, our observations do not support a scenario in which members of the Downtown Eastside drug-using community are actively seeking to recruit young drug users, initiate the latter into increasingly harmful drug using practices, and pave the way for their initiation into sex work activities. It is interesting to note that although we heard many stories about what happens when youth make a transition across drug-using milieus – such as the ‘morally-reproachable’ move from the Downtown South to the Downtown Eastside – there was a notable absence of narratives focused on what happens when and if youth are able to more permanently exit either of these locales.

In spite of the fact that most participants felt unable to envision a way out of the local scene in the present, youth consistently acknowledged exiting to be the most effective spatial tactic for extricating themselves from a dangerous and shameful cycle of accelerating addictions and an intensified need to generate income:

P: My drug problems are way different now… And that was because of, like, removing myself from Downtown, right? … Cause [downtown] I'd been doing like, like so many drugs. Like daily right? … Suddenly my [financial] resources are gone, or whatever, and I'm looking for drugs every day, I'm like, ‘How am I gonna get them?’ You know, like, so embarrassing. (Female Participant 11)

Ultimately, a number of participants were clear in emphasizing that, in fact, nowhere is safe for youth entrenched in the local scene due to frequent incidents of sexual exploitation and violence within peer groups and between themselves and various social actors including romantic partners, police, and informal ‘street’ employers. As a result, for many youth, the only viable spatial tactic available to them is to remain highly mobile (even if that means avoiding the regular use of service locations), so that one is difficult to ‘track down.’ Participants indicated that this could be crucial to staying safe on the streets:

P: I don't like anybody knowing where I am. I'm all in like, I'm everywhere. I'm not in one place. I'm everywhere. (Male Participant 16)

Discussion

In sum, our results build on previous work to emphasize how marginal places like the Downtown Eastside can become symbols and how these symbolic representations inform the ongoing construction of identity among young drug users who reside in these places – or those in close proximity to them (Eugene, 1999, Ruddick, 1997). Participants went to great lengths to emphasize the social distance between themselves and the Downtown Eastside, most often by ‘demonizing’ (and thereby vehemently differentiating themselves from) the adult drug users of the Downtown Eastside (Pinderhughes, 1993). However, identifying older residents of the Downtown Eastside as the ‘villains’ in these and other ‘stories-so-far’ is perhaps best understood as a reflection of the sense of powerlessness youth experience when making the transition from the Downtown South to the Downtown Eastside (Pinderhughes, 1993). Indeed, over the course of interviews the majority of participants berated themselves for at one time inhabiting and embodying what was understood as a derelict, disgusting and morally-void ‘junkie’ space (Dovey et al., 2001, Rhodes et al., 2007). Although social norms prohibiting young people's involvement in the Downtown Eastside exist among local youth, there are clearly other contextual factors that ‘push’ young people towards involvement within this drug-using milieu, until it feels difficult or impossible to avoid this geographical and social transition.

There is growing awareness of the relationship between place, everyday experiences of marginalization, and the embodiment of social exclusion (Rhodes et al., 2007, Dovey et al., 2001). Place has been identified as the site of symbolic violence in which those experiencing marginalization internalize forces of exclusion, stigmatization and poverty, which are then understood and experienced as personal deficiencies or shortcomings (Bourgois and Schonberg, 2007, Bourdieu and Wacquant, 1992). Drawing on Bourdieu's concept of habitus, our data illustrates how youth's embodiment of (and perceptions regarding how others embody) social exclusion and economic suffering takes on symbolic power that is naturalized, obscuring the ways in which in which social structural power relations inform intimate ways of being at the level of individual interactions, as well as the spatialization of everyday life (Bourgois and Schonberg, 2007, Bourdieu and Wacquant, 1992). We can see this clearly in young people's narratives about the ‘junkies’ and ‘crackheads’ of the Downtown Eastside – the latter's physical, psychological and moral ‘demise’ is viewed as a natural and inevitable consequence of ‘allowing’ oneself to ‘end up down there,’ rather than as a result of same forces of inequality that largely shape young people's own marginal positions. Indeed, as young people become increasingly powerlessness in their efforts to secure education, employment and housing (largely as a result of inadequate supports for young people struggling with intensive drug use and the psychological effects of everyday violence), it becomes ‘only natural’ that they should end up in the Downtown Eastside. The embodiment of social, spatial and economic marginalization powerfully shapes how young people are able to envision their ‘social destinies’ from places like the Downtown Eastside and the Downtown South, both of which reflect youth's limited opportunities ‘for escape’ (Shoveller et al., 2007). In this way, occupying a marginal position in social and geographical space powerfully informs (and ultimately reproduces) experiences of social suffering and marginalization in contemporary urban society (Castro and Lindbladh, 2004, Shoveller et al., 2007).

It follows that this study has implications for the ongoing debate regarding who has the ‘right to the city’ and its public spaces (Mitchell, 2003, Purcell, 2002). In the interest of enhancing the quality of urban life and protecting ‘public safety,’ young people experiencing homelessness (and other undesirable ‘outsiders’) have seen their rights to public space all but eliminated as a result of numerous state-sponsored initiatives that range from intensified surveillance and policing, to making park benches ‘un-sleepable’ via the addition to metal bars to partition bench ‘seats.’ What this study illustrates is how the spatial segregation of a class of people who have nowhere else to be but in public space is internalized and comes to be viewed by young people themselves as the ‘natural’ order of things in the context of ‘life on the street’ – and therefore nearly impossible to transcend (i.e. in spite of their best efforts, youth inevitably move from the Downtown South to the Downtown Eastside, but would never be able to exit either of these areas).

At the same time, this study demonstrates some of the ways in which marginalized ‘outsiders’ make known their right to those few places still available them for the pursuit of work, rest and relaxation – such as the Downtown South. Interestingly, given their present circumstances (in which exiting the local drug scene was not an option), many participants were committed to maintaining their presence in the Downtown South as an explicitly political project, vowing that they would not be displaced and from this area – whether as a result of urban gentrification or ‘clean-up’ efforts on the part of the city – only to be marginally housed or homeless in another part of the city. We want to emphasize that even young people living on the margins are active in shaping experiences of place and the construction of identity through social-spatial practices (De Certeau, 1984, Ruddick, 1997). Our results indicate that young people do carve out relatively ‘safe’ geographical niches (Beazley, 2002) within the downtown drug scene (e.g., residence in the Downtown South), and employ spatial tactics (De Certeau, 1984) aimed at reducing harm (e.g., avoidance of the Downtown Eastside in favor of the Downtown South, staying mobile). We employ the term spatial tactics in order to emphasize that local youth act within powerful structural constraints – including a lack of access to safe housing and drug treatment facilities (Rachlis et al., 2008) and social exclusion from mainstream employment and recreation opportunities – in order to maximize their safety within immediate environment in which they operate. Moreover, this study builds on previous work that illustrates how marginal, ‘nowhere’ places (such the protected areas underneath bridges and inside car parkades) can be used by youth to confront spatial constraints on their own terms (Ruddick, 1997). By occupying these ‘nowhere’ places in the Downtown South, for example, young people claim a success – albeit a fragile one – in situating themselves apart from the Downtown Eastside and the ‘demise’ it symbolizes.

Nevertheless, our results illustrate how spatial tactics aimed at reducing harms may at times force youth to decide between frequenting crucial service locations and avoiding those places that powerfully symbolize danger (as exemplified by the potential for relapse into problematic substance use, or the likelihood of being ‘tracked down’ for punishment) – drawing our attention to the urgent need for spatially-appropriate interventions for youth. So long as young people feel that they have to be ‘everywhere’ and ‘not in one place’ in order to be safe, we will likely continue to struggle to maintain connections between young people, service locations, and by association, service providers. It is interesting to note the absence of stories regarding the ‘people’ who offer supports for youth (e.g. youth workers) as opposed to the ‘places’ where youth access services (e.g. drop-in centers, shelters). Our data provides further support for mobile outreach and service delivery programs (Shannon et al., 2008b), as it would seem that this approach (for example, the use of well-equipped and well-staffed vehicles to circulate through the downtown core and provide assistance ‘on-the-spot’ in back alleys and other indeterminate spaces) fits nicely with young people's existing spatial tactics for keeping themselves safe in the context of everyday violence. Moreover, our work speaks to the need for large scale structural interventions that go beyond service programs to provide additional housing and other structures that provide more than momentary refuge from street violence.

Paradoxically, our results illustrate the complex role played by social networks in both facilitating and undermining safety among young people across and within geographically and conceptually distinct drug-using milieus. As others have pointed out previously (Singer, 2006, Moore, 2004a, Moore, 2002), our work brings into question the notion of a ‘street youth community’ comprised of relatively stable social relationships and characterized by social solidarity and camaraderie. Our work directly contradicts those studies which draw on somewhat romanticized descriptions of ‘gangs’ or ‘street families’ of youth in order to emphasize young people's agency and resilience in spite of social suffering. What our results indicate is that everyday experiences of violence and exploitation within shifting social networks that include a range of social actors (including peers, romantic partners, pimps and older drug users) lead many youth to the conclusions that ‘no one can be trusted’ and ‘nowhere is safe’ within the local scene. While not discounting the importance of ‘street families’ among youth in our context (and also recognizing that the nature of youth social networks will vary according to context), our findings emphasize that we must continue to look critically at the ways in which social networks may simultaneously diminish and exacerbate experiences of un-safety among youth entrenched in local drug scenes. The oftentimes contradictory roles that social networks play in shaping experiences of safety must be taken into consideration when developing interventions that attempt to integrate ‘community members’ or ‘peers’ from within local drug scenes (Singer, 2006).

Consistent with previous work (Rhodes et al., 2005, Shannon et al., 2008a, Bourgois et al., 2004), the results of this study illustrate the need for immediate structural-environmental interventions for young people – namely, the creation of safer spaces of work, rest and recreation (Rhodes et al., 2006, Rhodes et al., 2007). Young people's ‘right to the city’ must not only refer to the right to choose whether to sleep on the streets of the Downtown South or the Downtown Eastside, but also the right to meaningfully inhabit the urban landscape (Purcell, 2002, Mitchell, 2003). Most basically, interventions should include the creation of accessible housing combined with treatment facilities, as well as modifications to the built environment of the downtown core – for example, the creation of discreet drop-in centers or ‘safe zones’ for young women and young men that facilitate refuge from street-based violence. Moreover, interventions and modifications to the built environment should be aimed not only at reducing harms, but also at facilitating the construction of alternate subjectivities and new identities that provide a challenge to the pervasive and often stigmatizing labels (e.g. drug addict, sex worker) attached to young people entrenched in the local scene. In part, this could be achieved through enhanced access to low-threshold recreation and training programs that offer youth experiences apart from this setting – even if only for a brief period of time.

Young people's emphasis on the importance of ultimately exiting the downtown drug scene underscores the need for interventions that enable youth in their efforts to achieve this. Initially, programs situated outside of the geographical boundaries of the local drug scene (such as sport activities accompanied by accessible transportation to and from young people's places of primary residence) would fit with their existing tactics for beginning to distance themselves from un-safe locales. In the long term, providing enhanced support in finding safe housing, income support and meaningful education and work training placements for young people is crucial, as young people consistently expressed disillusionment regarding their future prospects even if they were to succeed in ‘getting out of downtown.’ Importantly, in seeking to offer young people a refuge or exits from the un-safety the downtown urban core, we do not want to inadvertently replicate efforts to remove ‘unsightly’ youth from public space. Working with youth towards the creation of safer spaces and the construction of alternate subjectivities must be distinguished from efforts that seek to ‘clean up’ the ‘street youth problem’ via programs and policies that allege to be in young people's best interests.

This study has several strengths and limitations that warrant acknowledgement. Firstly, we have attempted to frame this study in terms of young people's subjective experiences and meanings, while remaining sensitive to the need for continual reflexivity on the part of the researchers. We recognize that our own subjectivities and the interview/ethnographic process itself shaped our findings. In-depth interviews create opportunities for reflection on the part of participants that may not have been triggered before, and as such may constitute an intervention in the lives of participants in which new meanings emerge (alternatively, this may not be the case with ‘hyper-researched’ and ‘hyper-serviced’ youth, many of whom are highly adept at telling their stories to service providers and researchers). Furthermore, it is important to recognize that power relations are always embedded in the research process (particularly when working with young people), and this distribution of power ultimately favors the researchers' interpretation. Nevertheless, we believe our data was (to a certain extent) co-constructed through interaction and negotiation that flows in all directions: between members of the research team, between researchers and participants, and between participants themselves through their conversations about this study ‘on the streets’ (Pool, 1994, Fabian, 1998).

Secondly, it is important to note that our findings are based upon interviews with local youth participating in the current study. While an effort was made to ensure that the study sample reflects the demographics of the local youth population, it is likely that our sample is more representative of young people who experience the highest risk in downtown Vancouver. Not all youth experiencing homelessness and intensive drug use in downtown Vancouver experience the Downtown Eastside as a symbol of un-safety and inevitable physical, psychological and moral ‘demise,’ or the Downtown South as a place from which there is ‘no escape.’ Future work should focus on how symbolic representations are continually made and re-made through social-spatial practices. Furthermore, the perspectives of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer youth are underrepresented and under-explored in the present study, in spite of the fact that these youth experience significant vulnerability in our setting (Marshall et al., 2009). It also interesting that the gendered dimensions of our finding (i.e. young women's positioning vis-à-vis the Downtown Eastside and in the context of romantic partnerships) vary considerably from those reported elsewhere (e.g., young women and the creation of ‘girl-only’ spaces in Indonesia). Overall, more work (e.g., engaging youth in social-spatial mapping activities) is needed to understand how various forms of diversity inform situated experiences of safety and un-safety in downtown Vancouver.

Nevertheless, it is hoped that this study represents a contribution towards understanding how the meanings attached to particular places are not only a subject of academic interest, but also have important implications for the development of interventions that resonate with young people's everyday, situated experiences and understandings of risk and harm. Furthermore, we have attempted to raise important questions regarding, on the one hand, young people's right to be present in public space, and on the other hand, their right to be absent from spaces characterized by danger un-safety and danger. This study speaks to the importance of restoring a more broadly envisioned public that includes those currently deemed to be ‘outside’ of what is aesthetically and morally acceptable in public space (Mitchell, 2003). This is arguably a crucial first step in identifying the social structures and institutions that contribute to a narrowly-defined public and deepening inequalities, as well as facilitating young people in the construction of alternative identities beyond ‘homeless,’ ‘sex worker,’ and ‘drug-addicted.’

Acknowledgements

We would particularly like to thank the ARYS participants for their willingness to be included in the study, as well as current and past ARYS investigators and staff. We would specifically like to thank Deborah Graham, Tricia Collingham, Caitlin Johnston, Steve Kain, and Calvin Lai for their research and administrative assistance. This study was made possible through financial contributions from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (HHP-67262, MOP-81171, RAA-79918) and the National Institutes of Health Research (R01 DA011591).

Jean Shoveller is supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Applied Public Health Chair and a Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research Scholar Award. Kate Shannon is supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Bisby Award and a Canadian Institutes of Health Research/Canadian Coalition in Global Health Research Fellowship. Thomas Kerr is supported by a Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research Scholar Award and a Canadian Institutes of Health Research New Investigator Award.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

In referring to the Downtown South area, youth occasionally include Vancouver's West End neighborhood, which contains some youth services and numerous outdoor ‘hang outs’ and sleeping spots for homeless young people. For this reason, we have included the West End in our map of the downtown Vancouver drug scene, while demonstrating that this area is technically separate from the Downtown South.

In order to elicit youth perspectives regarding ‘social positioning,’ we asked youth to discuss the diversity within ‘street youth populations’ by virtue of the social hierarchies that exist within them, probing for how these hierarchies may be informed by gender, sexual orientation, ethnicity, age, and sense of ‘connectedness’ and/or experience within the local scene. We asked youth to reflect on how these hierarchies could affect a person's everyday interactions, movements and decisions within particular locales. We also asked youth what kinds of advice they would give to other youth regarding safe and unsafe places in the city, again probing for how this advice could change depending on the above factors.

References

- BEAZLEY H. ‘Vagrants Wearing Make-up’: Negotiating Spaces on the Streets of Yogyakarta, Indonesia. Urban Studies. 2002;39:1665–1683. [Google Scholar]

- BOURDIEU P, WACQUANT L. An invitation to reflexive sociology. Polity; Cambridge: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- BOURGOIS P. In Search of Respect: Selling Crack in El Barrio. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- BOURGOIS P. In Search of Respect: Selling Crack in El Barrio. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- BOURGOIS P, PRINCE B, MOSS A. The Everyday Violence of Hepatitis C Among Young Women Who Inject Drugs in San Francisco. Hum Organ. 2004;63:253–264. doi: 10.17730/humo.63.3.h1phxbhrb7m4mlv0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOURGOIS P, SCHONBERG J. Intimate apartheid: Ethnic dimensions of habitus among homeless heroin injectors. Ethnography. 2007;8:7–31. doi: 10.1177/1466138107076109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BUNGAY V, MALCHY L, BUXTON JA, JOHNSON J, MACPHERSON D, ROSENFELD T. Life with jib: A snapshot of street youth's use of crystal methamphetamine. Addiction Research & Theory. 2006;14:235–251. [Google Scholar]

- BUTLER J. Gender Trouble. Routledge; New York: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- CALDEIRA T. City of Walls: Crime, Segregation, and Citizenship in Sao Paulo. University of California Press; Berkeley: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- CASTRO PB, LINDBLADH E. Place, discourse and vulnerability--a qualitative study of young adults living in a Swedish urban poverty zone. Health & Place. 2004;10:259–272. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2003.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CONNELL J. Regulation of space in the contemporary postcolonial Pacific city: Port Moresby and Suva. Asia Pacific Viewpoint. 2003;44:243–257. [Google Scholar]

- COVENANT HOUSE VANCOUVER . A Profile of Vancouver's Street Youth. Vancouver: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- CURTIS T, WENDEL R. Toward the development of a typology of illegal drug markets. In: HOUGH M, NATARAJAN M, editors. Illegal drug markets: From research to policy. Criminal Justice Press; Mosey, NJ: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- DE CERTEAU M. The practice of everyday life. University of California Press; Berkeley: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- DOVEY K, FITZGERALD J, CHOI Y. Safety becomes danger: dilemmas of drug-use in public space. Health & Place. 2001;7:319–331. doi: 10.1016/s1353-8292(01)00024-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ELDER GH. Perspectives on the life course. In: ELDER GH, editor. Life course dynamics. Cornell University Press; Ithaca, New York: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- EUGENE JM. Race, Protest, and Public Space: Contextualizing Lefebvre in the U.S. City. Antipode. 1999;31:163–184. [Google Scholar]

- FABIAN J. Moments of freedom: anthropology and popular culture. University Press of Virginia; Charlottesville: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- FULLER CM, VLAHOV D, LATKIN CA, OMPAD DC, CELENTANO DD, STRATHDEE SA. Social circumstances of initiation of injection drug use and early shooting gallery attendance: implications for HIV intervention among adolescent and young adult injection drug users. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;32:86–93. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200301010-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GIGENGACK R. La banda de gari: the street community as a bundle of contradictions and paradoxes. Focaal. 2000;36:117–142. [Google Scholar]

- HECHT T. At home and in the street: street children of northeastern Brazil. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- HOUGH M, NATARAJAN M. Introduction: Illegal drug markets, research and policy. In: HOUGH M, NATARAJAN M, editors. Illegal drug markets:from research to policy. Criminal Justice Press; Monsey, NJ: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- HSER Y-I, LONGSHORE D, ANGLIN MD. The Life Course Perspective on Drug Use: A Conceptual Framework for Understanding Drug Use Trajectories. Eval Rev. 2007;31:515–547. doi: 10.1177/0193841X07307316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KLEINMAN A, DAS V, LOCK M. Social Suffering. University of California Press; Berkeley: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- LLOYD-SMITH E, KERR T, ZHANG R, MONTANER JSG, WOOD E. High prevalence of syringe sharing among street involved youth. Addiction Research & Theory. 2008;16:353–358. [Google Scholar]

- LOVELL AM. Risking risk: the influence of types of capital and social networks on the injection practices of drug users. Social Science & Medicine. 2002;55:803–821. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00204-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAHER L. Sexed work: Gender, race and resistance in a Brooklyn drug market. Oxford University Press; New York: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- MARSHALL B, KERR T, SHOVELLER J, MONTANER J, WOOD E. Structural factors associated with an increased risk of HIV and sexually transmitted infection transmission among street-involved youth. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MASSEY D. Space, Place, and Gender. University of Minnesota Press; Minneapolis: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- MAYOCK P. Scripting risk: Young people and the construction of drug journeys. Drugs: education, prevention and policy. 2005;12:349–368. [Google Scholar]

- MILLER CL, SPITTAL PM, FRANKISH JC, LI K, SCHECHTER MT, E. W. HIV and Hepatitis C Outbreaks Among High-risk Youth in Vancouver Demands a Public Health Response. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 2005;96:107–108. doi: 10.1007/BF03403671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MITCHELL D. The Right to the City: Social Justice and the Fight for Public Space. The Guilford Press; New York: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- MOORE D. Opening up the cul-de-sac of youth drug studies: a contribution to the construction of some alternative truths. Contemporary Drug Problems. 2002;29:13–63. [Google Scholar]

- MOORE D. Beyond “subculture” in the ethnography of illicit drug use. Contemporary Drug Problems. 2004a;31:181–212. [Google Scholar]

- MOORE D. Governing street-based injecting drug users: a critique of heroin overdose prevention in Australia. Social Science and Medicine. 2004b;59:1547–1557. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MOYER E. Popular Cartographies: youthful imaginings of the global in the streets of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. City & Society. 2004;16:117–143. [Google Scholar]

- PINDERHUGHES H. “Down With the Program”: Racial Attitudes and Group Violence Among Youth in Bensonhurst and Gravesend. In: CUMMINGS S, MONTI DJ, editors. Gangs: The origins and impact of contemporary youth gangs in the United States. State University of New York Press; Albany: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- POOL R. Dialogue and the Interpretation of Illness. Berg; Oxford: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- PURCELL M. Excavating Lefebvre: The right to the city and its urban politics of the inhabitant. GeoJournal. 2002;58:99–108. [Google Scholar]

- RACHLIS BS, WOOD E, ZHANG R, MONTANER JS, KERR T. High rates of homelessness among a cohort of street-involved youth. Health & Place. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2008.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RHODES T, KIMBER J, SMALL W, FITZGERALD J, KERR T, HICKMAN M, HOLLOWAY G. Public injecting and the need for ‘safer environment interventions’ in the reduction of drug-related harm. Addiction. 2006;101:1384–1393. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01556.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RHODES T, SINGER M, BOURGOIS P, FRIEDMAN SR, STRATHDEE S. The social structural production of HIV risk among injecting drug users. Social Science & Medicine. 2005;61:1026–1044. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RHODES T, WATTS L, DAVIES S, MARTIN A, SMITH J, CLARK D, CRAINE N, LYONS M. Risk, shame and the public injector: A qualitative study of drug injecting in South Wales. Social Science & Medicine. 2007;65:572–585. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROBINSON C. Creating Space, Creating Self: Street-frequenting Youth in the City and Suburbs. Journal of Youth Studies. 2000;3:429–443. [Google Scholar]

- ROY É, HALEY N, LECLERC P, CÉDRAS L, BLAIS L, BOIVIN J-F. Drug injection among street youths in montreal: Predictors of initiation. Journal of Urban Health. 2003;80:92–105. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jtg092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RUDDICK S, editor. How ‘homeless’ youth subcultures make a difference. Routledge; London: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- SANDBERG S, PEDERSEN W. “A magnet for curious adolescents”: The perceived dangers of an open drug scene. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2008;19:459–466. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHEPER-HUGHES N, HOFFMAN D. Brazillian apartheid: street kids and the struggle for urban space. In: SCHEPER-HUGHES N, SARGENT C, editors. Small wars: the cultural politics of childhood. University of California Press; Berkeley: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- SHANNON K, KERR T, ALLINOTT S, CHETTIAR J, SHOVELLER J, TYNDALL MW. Social and structural violence and power relations in mitigating HIV risk of drug-using women in survival sex work. Social Science & Medicine. 2008a;66:911–921. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHANNON K, RUSCH M, SHOVELLER J, ALEXSON D, GIBSON K, TYNDALL MW. Mapping violence and policing as an environmental-structural barrier to health service and syringe availability among substance-using women in street-level sex work. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2008b;19:140–147. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2007.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHOVELLER J, JOHNSON J, PRKACHIN K, PATRICK D. “Around here, they roll up the sidewalks at night”: A qualitative study of youth living in a rural Canadian community. Health & Place. 2007;13:826–838. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHOVELLER JA, JOHNSON JL. Risky groups, risky behaviour, and risky persons: Dominating discourses on youth sexual health. Critical Public Health. 2006;16:47–60. [Google Scholar]

- SINGER M. What is the ‘Drug User Community’?: Implications for Public Health. Human Organization. 2006;65:72–80. [Google Scholar]

- SMALL W, KERR T, CHARETTE J, SCHECHTER M, SPITTAL P. Impacts of intensified police activity on injection drug users: Evidence from an ethnographic investigation. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2006;17:85–95. [Google Scholar]

- SMALL W, KERR T, CHARETTE J, WOOD E, SCHECHTER M, SPITTAL P. HIV risks related to public injecting in Vancouver's Downtown Eastside. Canadian Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2005a;16:36A. [Google Scholar]

- SMALL W, KERR T, CHARETTE J, WOOD E, SPITTAL P. The physical environment of public drug use in Vancouver's Downtown Eastside. XVIth Conference on the Reduction of Drug Related Harm. 2005b [Google Scholar]

- STRATHDEE SA, PATRICK DM, CURRIE SL, CORNELISSE PG, REKART ML, MONTANER JS, SCHECHTER MT, O'SHAUGHNESSY MV. Needle exchange is not enough: lessons from the Vancouver injecting drug use study. Aids. 1997;11:F59–65. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199708000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- THE MCCREARY CENTRE SOCIETY . Between the cracks: Homeless youth in Vancouver. The McCreary Centre Society; Vancouver: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- THE MCCREARY CENTRE SOCIETY . Against the Odds: A profile of marginalized and street-involved youth in BC. The McCreary Centre Society; Vancouver: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- WERB D, KERR T, LAI C, MONTANER J, WOOD E. Nonfatal Overdose Among a Cohort of Street-Involved Youth. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2008;42:303–306. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WOOD E, KERR T. What do you do when you hit rock bottom? Responding to drugs in the City of Vancouver. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2006;17:55–60. [Google Scholar]

- WOOD E, KERR T, SMALL W, LI K, MARSH DC, MONTANER JS, TYDALL MW. Changes in public order after the opening of a medically supervised safer injecting facility for illicit injection drug users. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2004:171. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1040774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WOOD E, KERR T, SPITTAL PM, TYNDALL MW, O'SHAUGHNESSY MV, SCHECHTER MT. The healthcare and fiscal costs of the illicit drug use epidemic: The impact of conventional drug control strategies and the impact of a comprehensive approach. BCMJ. 2003;45:130–136. [Google Scholar]

- WOOD E, STOLTZ JA, MONTANER JS, KERR T. Evaluating methamphetamine use and risks of injection initiation among street youth: the ARYS study. Harm Reduct J. 2006;3:18. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-3-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WOOD E, STOLTZ JA, ZHANG R, STRATHDEE SA, MONTANER JS, KERR T. Circumstances of first crystal methamphetamine use and initiation of injection drug use among high-risk youth. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2008;27:270–6. doi: 10.1080/09595230801914750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]