Abstract

Objective

To test a computer-delivered program for preventing substance use among adolescent girls.

Method

Randomly, 916 girls aged 12.76 ± 1.0 years and their mothers were assigned to an intervention arm or to a test-only control arm. Intervention-arm dyads engaged in exercises to improve the mother-daughter relationship, build girls’ substance use prevention skills, and reduce associated risk factors. Study outcomes were girls’ and mothers’ substance use and mediator variables related to girls’ substance use risk and protective factors. The study was conducted between September 2006 and February 2009 with participants from greater New York City, including southern Connecticut and eastern New Jersey.

Results

At 2-year follow-up and relative to control-arm girls, intervention-arm girls reported lower relevant risk factors and higher protective factors as well as less past 30-day use of alcohol (p< 0.006), marijuana (p<0.016), illicit prescription drugs (p<0.03), and inhalants (p<0.024). Intervention-arm mothers showed more positive 2-year outcomes than control-arm mothers on variables linked with reduced risks of substance use among their daughters, and mothers reported lower rates of weekly alcohol consumption (p<0.0001).

Conclusions

A computer-delivered prevention program for adolescent girls and their mothers was effective in changing girls’ risk and protective factors and girls’ and mothers’ substance use behavior.

Keywords: Adolescents, substance use, prevention programming, computerized approaches, family involvement

Introduction

Reversing gender-differentiated patterns that have long favored boys, American girls are using harmful substances at rates that equal or surpass boys’ rates (Johnston et al., 2007). Whereas recreational prescription drug use is reported by 7.5% of teenage boys, 9.2% of teenage girls report such use (Office of National Drug Control Policy, 2007). Methamphetamine use is also becoming more common among girls than among boys (Embry et al., 2009). Among 12–14 year-olds, alcohol use rates are higher for girls than for boys (Pemberton et al., 2008). Binge drinking is also rising faster among girls than among boys (Newes-Adeyi et al., 2007). Cigarette use too may be making a resurgence among girls but not among boys (Wallace et al., 2003). Once girls start smoking, drinking, and using drugs, they are more likely than boys to become dependent on substance use (National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University, 2006).

Health risks from substance use also differ by gender. Eating disorders, more common among young women than among young men, are not infrequently accompanied by tobacco, alcohol, and drug use (Franko et al., 2008; Stice et al., 2004). Girls’ substance use is associated with high-risk behaviors. Substance-impaired girls who have sex are less likely to use condoms and are vulnerable not only to unintended pregnancy, unprotected sex, HIV infection and STIs, but also to sexual assault and date rape (Roberts et al., 2006). To address the growing prevalence and consequences of substance use among adolescent girls, new prevention approaches are needed.

A promising direction for those approaches is prevention programming that not only engages adolescent girls, but also that enlists their parents, especially their mothers. Throughout the early adolescent years, mothers continue to positively influence their daughters. Indeed, parent-involvement programs for preventing substance use among youth have been shown to be efficacious when delivered in clinical, school, and home settings (Austin et al., 2005; Dishion et al., 2008; Dusenbury, 2000; Trudeau et al., 2007). Yet, many families lack access to traditionally delivered prevention programming. Typically, parent-involvement programs are labor-intensive. And, these programs may fall short of meeting the needs of busy families that cannot easily manage the requisite coordination and multiple appointments associated with professionally delivered intervention programs. For family interventions to impact large numbers, they must be engaging, affordable, and flexible, meet tight scheduling demands, and demonstrate fidelity. An ideal intervention program would be available on demand, at home, and delivered in a way that engages parents and children.

Computer-mediated prevention programming fits these requirements. Computer programs let users access and navigate intervention content at their own pace. Interactive content is stimulating and varied and permits skills demonstrations and guided rehearsals. Participants can interact with content appropriate to their skill levels. Protocol fidelity, portability, ease of use, and data storage are added desirable characteristics of computer-mediated prevention programs. Nascent data support the promise of computer-mediated program delivery (Bellis et al., 2002; Evers et al. 2003; Portnoy et al., 2008; Schinke et al., 2004).

Building on prior work, the present study aimed to advance the science of computer-delivered substance abuse prevention programming. The study’s objective was to longitudinally test the efficacy of a computerized program that engaged adolescent girls and their mothers in a series of interactive exercises ultimately focused on reducing girls’ tobacco, alcohol, and other substance use. Study hypotheses were: 1) girls who participated in the program – compared to girls randomized to a control arm–would use less substances at follow-up; 2) program-arm girls would improve more than control-arm arms on risk and protective factors associated with substance use; and 3) program-arm mothers more than control-arm mothers would score higher on variables linked to increased parental support for their daughters’ reduced substance use risks.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

The study was a randomized clinical trial conducted in 2006, 2007, 2008, and 2009. Participants were adolescent girls and their mothers from greater New York City, including the city’s five boroughs as well as southern Connecticut and eastern New Jersey. Recruitment vehicles were postings on craigslist.org and advertisements in newspapers, posted on buses, and broadcast on a popular New York City radio station. Girls and mothers who responded to the recruitment messages were screened on four eligibility criteria: 1) girls and mothers need to speak and read English, 2) both members of the mother-daughter dyad needed to commit to study participation, 3) girls had to be 11, 12, or 13 years of age, and 4) girls and mothers needed private access to a personal computer.

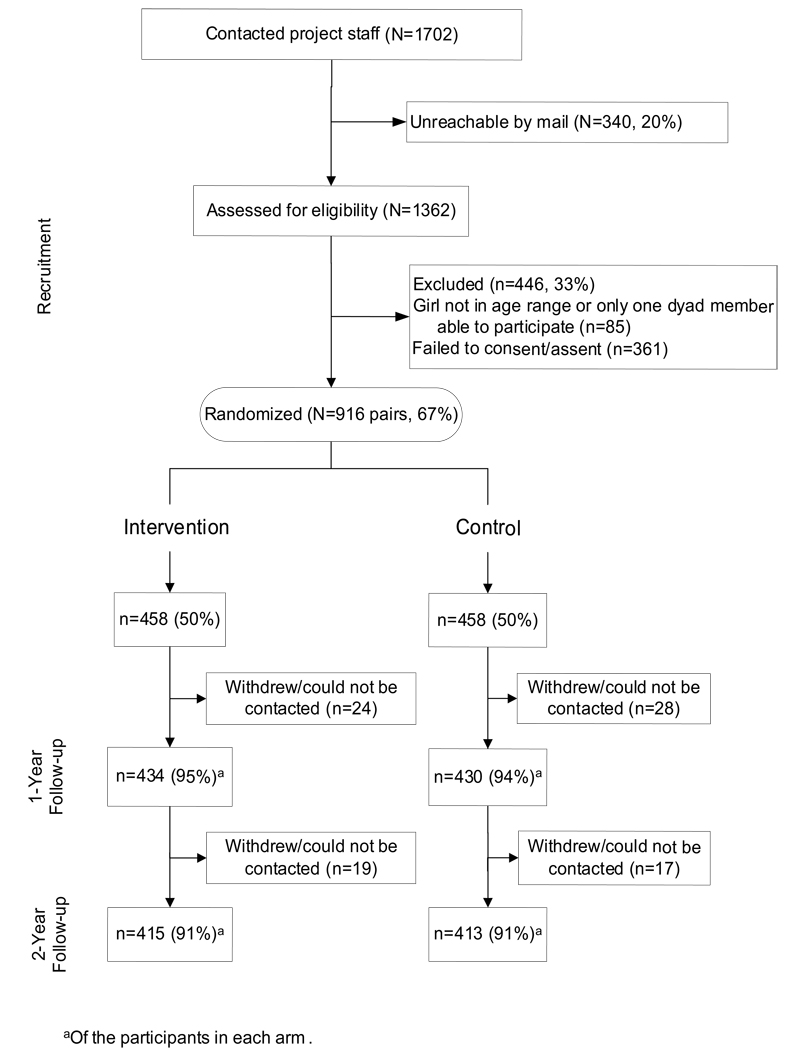

Of the 1,702 pairs of girls and mothers who expressed interest in the research, 340 (20%) could not be reached by mail with the contact information they provided (Figure 1). Of the 1,362 remaining mother-daughter pairs, 85 (6%) did not meet eligibility criteria and 361 (26.5%) failed to return assent, permission, and consent forms. Consequently, 916 mother-daughter dyads were enrolled.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of mother and daughter participant recruitment and progress in a randomized trial (N=916 mother-daughter pairs) of a computerized substance use prevention program conducted in greater New York City, including southern Connecticut and eastern New Jersey, between September 2006 and February 2009

Procedure

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Morningside Campus Institutional Review Board of Columbia University. Girls assented and gained parental permission, and girls’ mothers consented prior to enrollment. Enrolled mother-daughter dyads were randomized to intervention and control arms and given individual usernames and passwords to log onto the study website. All participants completed baseline measures. Intervention-arm participants completed initial program sessions via the Internet or CD-ROM. All participants completed two annual follow-up data collections consisting of measures identical to baseline measures. Intervention-arm participants received annual booster sessions after each follow-up measurement.

After each data collection occasion, girls and mothers in both arms received incentives in the form of online and in-store coupons and gift certificates to merchants of their choosing. Intervention-arm participants were also incentivized to complete initial and booster program sessions in a timely manner. Illustrative of incentive levels provided to mothers and daughters in both arms were coupons and gift cards valued at $20 and $25, respectively, when they finished 1- and 2-year follow-up measurements.

Prevention Program

Most intervention-arm girls and mothers (383 pairs or 84%) gained access to the prevention program through the Internet, with the remaining 75 (16%) completing the program via CD-ROM. No mother-daughter dyads who began the program via the Internet subsequently changed their mode of intervention delivery to CD-ROM. Guided by family interaction theory, the prevention program sought to change girls’ risk and protective factors through mother-daughter interactions (Brook et al., 1990). Mothers learned to better communicate with their daughters, monitor their daughters’ activities, build their daughters’ self-image and self-esteem, establish rules about and consequences for substance use, create family rituals, and refrain from placing unrealistic expectations on their daughters. In the program, girls learned to manage stress, conflict, and mood; refuse peer pressure; enhance their body esteem and self-efficacy; and accurately assess the prevalence of cigarette, alcohol, and drug use among their age-mates.

At home and at times convenient to them, mother-daughter dyads interacted with the program’s initial nine sessions on a schedule of one 45-minute session per week (Table 1). Annual booster sessions were also 45-minutes long. Each session was delivered through voice-over narration, skills demonstrations by animated characters, and interactive exercises for mothers and daughters to complete jointly. Program exercises taught mothers and daughters the value of listening to each other, spending time together, understanding one another’s personality, negotiating mutually agreeable decisions to problems, doing personal favors for one another, and giving each other praise and compliments.

Table 1.

Initial and booster session intervention themes and content for a randomized trial of a computerized substance use prevention program conducted in greater New York City, including southern Connecticut and eastern New Jersey, between September 2006 and February 2009

| Session No. |

Theme | Content |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Intervention | ||

| 1 | Mother-daughter relationship |

Mother-daughter communication (active listening), mother-daughter closeness, assertiveness, praise |

| 2 | Conflict management |

Mother-daughter communication, respect, self- efficacy, parent monitoring |

| 3 | Substance use opportunities |

Substance use education, rules against use, parent monitoring, positive reinforcement, family rituals, mother-daughter closeness, coping, social supports |

| 4 | Body image | Idealized vs. healthy bodies, body esteem, self- esteem, coping skills, physical activity, media influences, puberty |

| 5 | Mood management | Depression, thinking mistakes, coping skills, social supports, physical activity, relaxation techniques, mother-daughter communication |

| 6 | Stress reduction | Coping, social supports, mother-daughter communication, goal-setting |

| 7 | Problem solving | Stop, Options, Decide, Action, Self-Praise (SODAS) problem-solving sequence, self-efficacy |

| 8 | Norms and social influences |

Media influences, family rituals, mother-daughter closeness, substance use education, refusal skills, self-efficacy |

| 9 | Self-efficacy | Refusal skills, self-esteem, goal-setting, racism, assertiveness |

| Booster Sessions | ||

| 1 | Review | Mother-daughter communication, mother-daughter closeness, self-efficacy, refusal skills, coping skills, parent monitoring, rules against use, SODAS sequence, body-esteem, self-esteem |

| 2 | Review | Mother-daughter communication, mother-daughter closeness, self-efficacy, refusal skills, coping skills, parent monitoring, rules against use, SODAS, body- esteem, self-esteem |

Toward enhancing intervention delivery fidelity, program sessions were designed to let girls and their mothers advance to the next session only if each of them separately answered correctly questions on the prior session. Further, participants could access post-intervention and follow-up measures only when they finished all program sessions. Booster session fidelity was monitored by programmed instructions to capture answers about session content from girls and mothers separately.

Measures

Completed exclusively online at baseline and at both follow-up data collections, outcome measures for girls and mothers in both arms of the trial quantified substance use variables and risk and protective factors with particular salience for adolescent girls. Scales for each measured outcome variable, together with illustrative items and Cronbach’s alpha reliability statistics – depicting the range of internal consistency correlations for items within each scale, are summarized in Table 2. Because the online data collection system accepted participant responses only when all questions were answered, missing values were limited to those occasioned by participant loss due to attrition, rather than incomplete answers.

Table 2.

Outcome measures for a randomized trial of a computerized substance use prevention program conducted in greater New York City, including southern Connecticut and eastern New Jersey, between September 2006 and February 2009

| Outcome Variable |

Adapted From | Illustrative Item | α* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Measures for Girls | |||

| Mother-daughter communication | Iowa Family Interaction Ratings Scale (Melby et al., 1988) | In the last week, how often did your mom praise or compliment you for doing something well? | 0.80 – 0.84 |

| Mother-daughter closeness | Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment (Armsden & Greenberg, 1987) | I can talk to my mom about my problems. | 0.72 – 0.91 |

| Family rules | The Family Alcohol Discussions Scale (Komro et al., 2006) | What would your parents do if they found out that you had been drinking alcohol? | 0.77 – 0.83 |

| Parental monitoring | The Parental Monitoring Scale (Li et al., 2000) | I tell my mom about what I plan to do with my friends. | 0.88 |

| Body esteem | Self-Perception Profile for Adolescents (Harter, 1988; Thompson & Zand, 2002) | I am happy about the way I look. | 0.80 – 0.86 |

| Depression | Children’s Depression Inventory (Kovacs, 1992) | In the last 2 weeks, I was sad most of the time. | 0.71 – 0.89 |

| Coping ability | Coping Across Situations Questionnaire (Seiffge-Krenke, 1995) | I think about the problem and try to find different solutions. | 0.73 – 0.88 |

| Normative beliefs | Beliefs about Peer Norms Scale (Hansen & McNeal, 1997) | How many of your closest friends have tried ecstasy? | 0.88 |

| Refusal self-efficacy | Refusal Self-Efficacy Scale (Macaulay et al., 2002) | If a boy you like offered you some pot and you didn’t want it, how hard would it be to say no? | 0.83 – 0.85 |

| Substance use | American Drug and Alcohol Survey (Rocky Mountain Behavioral Institute, 2003) | In the last month, how many times did you smoke marijuana? | 0.72 – 0.94 |

| Intentions | Commitment to Not Use Drugs Scale (Hansen, 1996) | I know that I will get drunk sometime in the next year. | 0.84 |

| Measures for Mothers | |||

| Family rituals | Family Routines Inventory (Jensen et al., 1983) | Do your children have set bedtimes? | 0.74 – 0.79 |

| Mother-daughter communication | Iowa Family Interaction Ratings Scale (Melby et al., 1988) | In the last week, how often did you praise or compliment your daughter? | 0.74 – 0.76 |

| Mother-daughter closeness | Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment (Armsden & Greenberg, 1987) | My daughter tells me about her problems. | 0.76 – 0.91 |

| Family rules | The Family Alcohol Discussions Scale (Komro et al., 2006) | My children know what the consequences are for smoking cigarettes. | 0.77 – 0.83 |

| Parental monitoring | Parent Report of Monitoring (Gorman-Smith et al., 1996) | If my daughter is going to be late, she lets me know. | 0.82 |

| Alcohol use | Substance Abuse Subtle Screening Inventory (Miller, 1994) | In the last week, how many alcohol drinks did you have? | 0.81 – 0.91 |

Cronbach’s alpha reliability statistics showing the range of internal consistency correlations for items within each outcome measurement scale.

Statistical Analyses

Differences between study arms and across baseline and 1- and 2-year follow-up measurements were tested by a repeated-measures general linear analytic model. Tests of intervention by measurement interactions adjusted for girls’ age and ethnic-racial background and for mothers’ age and head-of-household status. By Mauchly’s method, we determined whether sphericity was violated and, if so, we applied the Greenhouse-Geiser corrected epsilon value to adjust subsequent repeated-measures ANOVAs (Keselman et al., 2001).

Results

Participant Characteristics and Retention

Baseline characteristics for the 916 enrolled girls revealed an ethnically and racially diverse sample (Table 3). Of the 916 mothers of these girls, fewer than one-half were single parents, and most were well educated. From baseline to 1-year follow-up, 52 dyads (5.7%) withdrew from the study or could not be reached for further contact. Between 1- and 2-year follow-ups, 36 dyads (4.2%) withdrew from the study or could not be reached for further contact. Girls who left the study prior to 2-year follow-up did not differ from those who remained on any demographic or outcome variable.

Table 3.

Characteristics of adolescent girls (N=916) and their mothers (N=916) in a randomized trial of a computerized substance use prevention program conducted in greater New York City, including southern Connecticut and eastern New Jersey, between September 2006 and February 2009

| Mean (SD) or % | |

|---|---|

| Girls (N = 916) | |

| Age, years | 12.76 (1.0) |

| Ethnicity/Race | |

| Black | 40.6 |

| White | 23.2 |

| Latina | 23.1 |

| Asian | 10.8 |

| Other | 1.7 |

| Academic grades | |

| A’s | 39.1 |

| B’s | 42.3 |

| C’s | 13.4 |

| D’s and below | 5.2 |

| Mothers (N = 916) | |

| Age, years | 39.9 (6.68) |

| Household | |

| Single-parent | 43.7 |

| Two-parent | 56.3 |

| Education | |

| < High school | 6.3 |

| High school | 9.1 |

| Some college | 28.3 |

| A.A. or B.A. degree | 42.6 |

| Graduate degree | 13.7 |

Percentages may not add to 100 because of missing data.

Outcome Analyses

At baseline, intervention-arm girls reported more positive patterns of communication with their mothers than control-arm girls (p<0.05; Table 4). Control-arm girls at baseline reported less depression than intervention-arm girls (p<0.05). Comparisons of girls and mothers who completed the prevention program online and those who completed the program via CD-ROM failed to reveal any 1- or 2-year outcome differences between the two delivery vehicles.

Table 4.

Baseline and 2-year follow-up data for adolescent girls (N=916) and their mothers (N=916) in a randomized trial of a computerized drug use prevention program conducted in greater New York City, including southern Connecticut and eastern New Jersey, between September 2006 and February 2009

| Girls | Baseline | 1-Year Follow-Up | 2-Year Follow-Up | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention Mean (SD) |

Control Mean (SD) |

Intervention Mean (SD) |

Control Mean (SD) |

Intervention Mean (SD) |

Control Mean (SD) |

F | p< | |

| Maternal communication* | 3.44 (2.4) | 3.01 (2.2) | 3.81 (2.4) | 2.76 (2.1) | 3.48 (2.4) | 2.80 (2.1) | 5.44 | 0.004 |

| Maternal closeness | 2.97 (1.1) | 2.79 (1.2) | 3.13 (1.0) | 2.71 (1.2) | 3.04 (1.1) | 2.59 (1.2) | 6.86 | 0.002 |

| Family rules | 2.22 (1.4) | 2.09 (1.3) | 2.76 (1.2) | 2.06 (1.3) | 2.52 (1.3) | 2.05 (1.3) | 12.39 | 0.0001 |

| Parental monitoring | 3.48 (0.8) | 3.50 (0.9) | 3.60 (0.8) | 3.40 (0.9) | 3.52 (0.8) | 3.25 (0.9) | 10.07 | 0.0001 |

| Body image | 3.73 (1.3) | 3.68 (1.3) | 3.65 (1.3) | 3.40 (1.4) | 3.45 (1.3) | 3.42 (1.3) | 2.45 | ns |

| Depressiona* | 3.42 (0.7) | 3.28 (0.8) | 3.45 (0.8) | 3.30 (0.8) | 3.48 (0.8) | 3.23 (0.8) | 1.79 | ns |

| Coping skill | 2.03 (1.5) | 2.13 (1.5) | 1.94 (1.5) | 1.82 (1.5) | 3.59 (0.9) | 3.22 (0.6) | 12.41 | 0.0001 |

| Normative beliefsa | 1.52 (1.1) | 1.50 (1.1) | 1.46 (1.1) | 1.85 (1.5) | 1.78 (1.3) | 2.35 (1.7) | 13.79 | 0.0001 |

| Drug refusal | 3.66 (0.6) | 3.63 (0.7) | 3.69 (0.6) | 3.50 (0.7) | 3.58 (0.7) | 3.35 (0.8) | 7.72 | 0.0001 |

| Past 30-Day Useb | ||||||||

| Cigarettes | 1.02 (0.2) | 1.04 (0.3) | 1.02 (0.4) | 1.14 (1.2) | 1.05 (0.5) | 1.39 (3.6) | 1.11 | ns |

| Alcohol | 0.14 (0.2) | 0.18 (0.3) | 0.15 (0.2) | 0.25 (0.5) | 0.17 (0.3) | 0.33 (0.7) | 5.20 | 0.006 |

| Marijuana | 0.08 (0.0) | 0.09 (0.0) | 0.09 (0.0) | 0.11 (0.2) | 0.10 (0.1) | 0.20 (0.7) | 4.12 | 0.016 |

| Illicit prescriptions | 0.12 (0.2) | 0.09 (0.1) | 0.09 (0.0) | 0.10 (0.1) | 0.09 (0.1) | 0.11 (0.2) | 3.58 | 0.03 |

| Inhalants | 0.04 (0.3) | 0.01 (0.1) | 0.02 (0.2) | 0.04 (0.3) | 0.02 (0.1) | 0.03 (0.2) | 3.72 | 0.024 |

| Future intentionsa | 0.98 (1.0) | 0.98 (1.1) | 0.94 (1.0) | 1.26 (1.3) | 1.10 (1.2) | 1.50 (1.4) | 10.38 | 0.0001 |

| Mothers | ||||||||

| Family rituals | 3.97 (1.7) | 3.54 (1.7) | 3.89 (1.5) | 3.44 (1.6) | 3.86 (1.5) | 1.02 (0.5) | 243.4 | 0.0001 |

| Daughter communication | 3.66 (2.1) | 3.50 (2.1) | 3.70 (2.1) | 3.24 (2.1) | 3.45 (2.0) | 2.03 (0.7) | 34.32 | 0.0001 |

| Daughter closeness | 3.81 (1.6) | 3.73 (1.6) | 3.65 (1.5) | 3.48 (1.6) | 3.44 (1.5) | 1.50 (1.2) | 109.9 | 0.0001 |

| Family rulesc | 4.81 (0.5) | 4.82 (0.6) | 4.90 (0.5) | 4.82 (0.4) | 4.89 (0.4) | 3.70 (1.2) | 41.79 | 0.0001 |

| Monitors daughter | 3.72 (0.5) | 3.66 (0.7) | 3.68 (0.6) | 3.58 (0.7) | 3.59 (0.7) | 3.00 (1.8) | 19.47 | 0.0001 |

| Weekly alcohol useb | 2.17 (2.2) | 1.99 (2.1) | 1.99 (2.0) | 2.14 (2.4) | 1.83 (2.1) | 2.84 (1.1) | 25.17 | 0.0001 |

Except as noted, scores are from 5-point scales; higher scores are better.

Scores are from 5-point scales; lower scores are better.

Reported use occasions.

Scores are from a 6-point scale; higher scores are better.

Baseline differences between arms (p<0.05).

By the 2-year follow-up occasion, according to analyses of time by intervention effects, girls and mothers who received the prevention program realized more positive changes than their control-arm counterparts on 18 of 21 measured variables. At 2-year follow-up, after participating in the prevention program and relative to control-arm girls, intervention-arm girls reported more positive outcomes on communication with their mothers (p<0.004), closeness to their mothers (p<0.002), knowledge of family rules about substance use (p<0.0001), awareness of parental monitoring of their extracurricular activities (p<0.0001), ability to cope with stress (p<0.0001), recognition that adolescent substance use is not normative behavior (p<0.0001), and drug refusal self-efficacy (self-perceived ability to refuse offers of cigarettes, alcohol, and drugs from peers; p<0.0001).

Reported as number of use occasions (i.e., 1.0 indicates a single use occasion of the respective substance in the past 30 days), girls’ substance use in the past 30 days favored the intervention arm over the control-arm at 2-year follow-up. Girls who received intervention reported fewer occasions of alcohol use (p<0.006), marijuana use (p<0.016), use of prescriptions for nonmedical purposes (p<0.03), and inhalant use (p<0.024) than girls in the control arm. Further, relative to control-arm girls, girls in the intervention arm reported lower intentions to use tobacco, alcohol, and drugs in the future (p<0.0001) at 2-year follow-up.

Intervention-arm mothers reported better 2-year follow-up outcomes than control-arm mothers on their observance of family rituals (p<0.0001), communication with their daughters (p<0.0001), closeness to their daughters (p<0.0001), establishment of family rules against their daughters’ substance use (p<0.0001), monitoring of their daughters’ out-of-home activities (p<0.0001), and their own weekly alcohol consumption (p<0.0001).

Discussion

Study findings lend empirical support to the promise of a computer-delivered, mother-daughter program for preventing substance use among adolescent girls. Two years after the prevention program was initially delivered, study results favored intervention-arm girls relative to control-arm girls on variables associated with lower risks for substance use, variables that can protect adolescent girls against substance use, and girls’ substance use behavior and intentions. Mothers who received the prevention program had better outcomes than control-arm mothers on variables associated with lower substance use risks for their adolescent daughters. Intervention-arm mothers also reported lower rates of weekly alcohol consumption than their control-arm counterparts.

Across a number of variables, between-arm differences observed in the study appear as much due to worsening behavior patterns for control girls as to improvements for program girls. That adolescent girls attenuate their closeness to parents and accelerate their risk taking behavior as they mature is an expected part of the developmental process. Over time, substance use in particular increases with adolescents’ expanding discretionary time, friendship networks, and access to substances and substance users. Peer influences ascend and parental control wanes throughout adolescence (De Goede et al., 2009). Study findings for control-arm girls and mothers reveal these trends. Control-arm girls and mothers nearly uniformly reported less positive scores from baseline to 2-year follow-up on variables of mother-daughter communication and closeness, daughter monitoring by parents, knowledge and establishment of family rules against substance use, and participation in family rituals – all factors that can protect adolescent girls against substance use (Borawski et al., 2003; Wood et al., 2004).

Albeit program-arm participants also scored worse on some measured variables over time, their decreases were not as precipitous as those recorded for control-arm girls and mothers. Moreover, girls and mothers who took part in the prevention program performed better over time on several measures, enhancing between-arm differences. Patterns of substance use also reveal upward trajectories for control-arm girls that exceeded those for program-arm girls. Girls’ intentions to smoke, drink, and take drugs in the future show remarkably different slopes across the 2-year measurement period. Starting at baseline with identical intentions about future substance use, control- and program-arm girls reported higher intentions 2-years later. Whereas girls who received intervention increased their intentions to use substances by 12% over this period, control-arm girls increased their intentions by 53%.

The corpus of 2-year findings suggests that beneficial features of the mother-daughter relationship were nurtured and sustained by the prevention program. Compared to control-arm girls, those who took part in the program reported better interactions with their mothers, more knowledge of family rules against their substance use, and stronger awareness that their parents were monitoring their extracurricular activities. Further, girls’ program participation was associated with their enhanced capacity to handle stress, accurate appraisals about peer substance use, and ability to refuse offers of tobacco, alcohol, and drugs. The constellation of these skills is linked with lower rates of substance use among adolescent girls and is theoretically complementary to family protective factors (Botvin et al., 2004; Stevens et al., 2003). Perhaps acting in a synergistic manner, changes in girls’ risk and protective factors may in part explain intervention-arm girls’ comparatively lower use rates of alcohol, marijuana, illicit prescriptions, and inhalants, and their comparatively lower intentions to use harmful substances in the future.

Study outcomes for intervention-arm mothers largely mirror their daughters’ outcomes. By design, the prevention program attempted to alter the relationship, perceptions, and behavior of girls and their mothers. Mothers and girls mutually profited from the program in their communication with and closeness to one another, enforcement and awareness of family rules against adolescent substance use, and engagement in and knowledge of parental monitoring aimed at girls’ out-of-home activities and friendships. Parent-involvement programs are founded on the premise that when children and parents jointly participate, program impact grows (Dishion et al., 2008; Spoth et al., 2002). In our program, girls and mothers engaged in activities to build their relationship. Study outcomes may evince the products of that improved relationship.

Happily surprising were observations of mothers’ own reduced alcohol consumption. Perhaps the program raised mothers’ consciousness of how their substance use could inadvertently serve to model undesirable behavior for their daughters. Or, mothers may have integrated program content to effect changes in their own behavior. Whatever the explanation, an average difference of one alcoholic drink per week between intervention- and control-arm mothers at 2-year follow-up is noteworthy.

The absence of changes in girls’ body esteem, depression, and cigarette use deserve mention. Because the program’s gender-specificity targeted such issues as body image, weight concerns, and idealized standards of physical appearance, post-intervention movement on the body esteem variable was expected. Nearly uniform decreases in positive body esteem across the 2-year measurement period, however, sadly imply that girls in our sample were not immune from societal, media, and peer pressures toward standards of feminine beauty that are difficult to attain (Striegel-Moore et al., 1995). During the course of our study, girls’ average age went from roughly 12.8 years to 14.8 years, a time of pubertal maturation that can bring weight gain, self-scrutiny, and invidious comparisons with thinner and more comely girls, particularly those whose images dominate the media aimed at young women. As for depression, girls in both arms demonstrated a healthy concinnity in their scores on this variable, suggesting that a relative ceiling of good mental health was apparent in the sample and not in need of change. Last, rates of cigarette use remained stable in the intervention arm over the study period, but soared in the control arm, with an accompanying large variance. This trend was due to a few control arm girls reporting heavy cigarette use, without a sufficiently strong trend to move the mean differences into statistical significance.

Study limitations and strengths

Limitations of the study encompass methodological and generalization parameters. A methodological limitation is our reliance upon self-reported data. Not only could study participants have under- or over-reported their substance use behavior, but also girls and mothers could have represented changes in risk and protective factors that were not entirely accurate. The exigencies of self-reported data were particularly acute for intervention-arm participants. Mothers and daughters in this arm may have been more vulnerable than control-arm participants to erroneous perceptions that each member of the dyad may have been privy one another’s self-reports.

Also limiting study findings is the length of follow-up measurement. Given that girls in our sample have not yet entered the highest-risk years for the onset and adoption of substance use, additional follow-up measurements are necessary. Notwithstanding their statistical significance, study results yield modest effect sizes, constraining the clinical implications of the prevention program.

Limiting the generalization of study results is the nature of the substance use prevention program. Delivering program content by computer restricts the reach of the material to households equipped with personal computers. That our sample was from a large urbanized region of the Northeastern United States further limits generalization. Mothers in the sample were well educated and may not typify parents in need of family-involvement programs to prevent adolescent substance use. Given that mothers and girls asked to be part of the research, self-selection biases cannot be denied.

Strengths of the study lie in the intervention approach and the tested program. The intervention approach – combining gender-specificity, parent involvement, and computer delivery – offers advantages. Growing rates of substance use among adolescent girls call for efforts that address gender-specific risk and protective factors. By engaging mothers, our approach tapped a rich source of bonding, positive social support, role modeling, and shared problem solving. Delivering intervention by computer may have overcome barriers to enrolling and capturing the attention of busy families. Computer intervention fosters candid conversations in the privacy and comfort of participants’ homes. Through these conversations, girls can share their everyday problems, and mothers can offer constructive guidance.

Computer programs bring with them features unavailable to traditionally delivered intervention approaches. Illustrative are the fidelity checks built into our program to ensure that mother-daughter dyad members jointly participated in and completed each intervention session. Cost savings in program delivery are another clear advantage of our program and any computer-delivered intervention. Compared with the expense of live program delivery – e.g., training the intervention agents, scheduling and convening program recipients, implementing the program – computer programs demand minimal resources to deliver once they are developed. Computer program dissemination is not only simpler and cheaper than live program dissemination, but also computer programs are likely to have greater fidelity than programs that require trained intervention agents.

A last notable strength of the study was the relatively small loss of participants to attrition. The availability of a relatively intact study sample was an aid to data analyses and, subsequently, to our ability to find outcome effects.

Conclusions

Data from this trial indicate that a gender-specific, mother-daughter substance use prevention program delivered by computer can effect desirable changes for involved adolescent girls and their mothers. Notwithstanding the need for larger replication trials with generalizable samples and longitudinal follow-up, the study suggests that responsive prevention approaches can begin to reverse trends toward increased use of harmful substances among adolescent girls.

Acknowledgements

Research reported in this paper was funded by grant no. DA17721 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health, United States Department of Health and Human Services.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Armsden GC, Greenberg MT. The Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment: individual differences and their relationship to psychological well-being in adolescence. J Youth Adolesc. 1987;16:427–454. doi: 10.1007/BF02202939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin AM, Macgowan MJ, Wagner EF. Effective family-based interventions for adolescents with substance use problems: a systematic review. Res Soc Work Pract. 2005;15:67–83. [Google Scholar]

- Bellis JM, Grimley DM, Alexander LR. Feasibility of a tailored intervention targeting STD-related behaviors. Am J Health Behav. 2002;26:378–385. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.26.5.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borawski EA, Levers-Landis CE, Lovegreen LD, Trapl ES. Parental monitoring, negotiated unsupervised time, and parental trust: the role of perceived parenting practices in adolescent health risk behaviors. J Adolesc Health. 2003;33:60–70. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(03)00100-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botvin G, Griffin KW. Life Skills Training: empirical findings and future directions. J Prim Prev. 2004;25:211–232. [Google Scholar]

- Brook JS, Brook DW, Gordon AS, Whiteman M, Cohen P. The psychological etiology of adolescent drug use: a family interactional approach. Genet Soc Gen Monogr. 1990;116 (Whole No. 2) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Goede IHA, Branje SJT, Meeus WHJ. Developmental changes in adolescents' perceptions of relationships with their parents. J Youth Adolesc. 2009;38:75–89. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9286-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Shaw D, Connell A, Gardner F, Weaver C, Wilson M. The family check-up with high-risk indigent families: preventing problem behavior by increasing parents’ positive behavior support in early childhood. Child Dev. 2008;79:1395–1414. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01195.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dusenbury L. Family-based drug abuse prevention programs: A review. J Prim Prev. 2000;20:337–352. [Google Scholar]

- Embry D, Hankins M, Biglan A, Boles S. Behavioral and social correlates of methamphetamine use in a population-based sample of early and later adolescents. Addict Behav. 2009;34:343–351. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evers KE, Prochaska JM, Prochaska JO, Driskell M, Cummin CO, Velicer WF. Strengths and weaknesses of health behavior change programs on the Internet. J Health Psychol. 2003;8:63–70. doi: 10.1177/1359105303008001435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franko DL, Dorer D, Keel PK, Jackson S, Manzo MP, Herzog DB. Interaction between eating disorders and drug abuse. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2008;196:556–561. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e31817d0153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorman-Smith D, Tolan PH, Zelli A, Huesman LR. The relation of family functioning to violence among inner-city minority youth. J Fam Psychol. 1996;10:115–129. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen WB. Pilot test results comparing the All Stars program with seventh grade D.A.R.E.: program integrity and mediating variable analysis. Sub Use Misuse. 1996;31:1359–1377. doi: 10.3109/10826089609063981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen WB, McNeal RB. How D.A.R.E. works: An examination of program effects on mediating variables. Health Educ Behav. 1997;24:165–176. doi: 10.1177/109019819702400205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harter S. Manual for the self-perception profile for adolescents. Denver CO: University of Denver; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen EW, James SA, Boyce WT, Hartnett SA. The Family Routines Inventory: development and validation. Soc Sci Med. 1983;17:201–211. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(83)90117-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future national results on adolescent drug use: overview of key findings, 2006. Bethesda MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2007. (NIH Publication No. 07-6202) [Google Scholar]

- Keselman HJ, Algina J, Kowalchuk RK. The analysis of repeated measures designs: a review. Brit J Math Stat Psychol. 2001;54:1–20. doi: 10.1348/000711001159357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komro KA, Perry CL, Veblen-Mortenson S, Farbakhsh K, Kugler KC, Alfano KA, et al. Cross cultural adaptation and evaluation of a home-based program for alcohol use prevention among urban youth: the Slick Tracy Home Team Program. J Primary Prev. 2006;27:135–154. doi: 10.1007/s10935-005-0029-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M. The Children’s Depression Inventory manual. New York: Multi Health Systems; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Feigelman S, Stanton B. Perceived parental monitoring and health risk behaviors among urban low-income African-American children and adolescents. J Adol Health. 2000;27:43–48. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(99)00077-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macaulay AP, Griffin KW, Botvin GJ. Initial internal reliability and descriptive statistics for a brief assessment tool for the Life Skills Training drug abuse prevention program. Psychol Rep. 2002;91:459–462. doi: 10.2466/pr0.2002.91.2.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melby JN, Conger RD, Book R, Rueter M, Lucy L, Repinski D, et al. Institute for Social & Behavioral Research. 5th edition. Ames, IA: Iowa State University; 1998. The Iowa Family Interaction Rating Scales. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Miller GA. Substance Abuse Subtle Screening Inventory – Adult. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University. Women under the influence. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Newes-Adeyi GM, Chen CM, Williams GD, Faden VB. Surveillance Report #81: Trends in underage drinking in the United States, 1991–2005. Rockville MD: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Office of National Drug Control Policy. [Retrieved August 31, 2008];Women and prescription drugs. 2007 from http://www.whitehousedrugpolicy.gov/drugfact/pdf/043007_women_presc_drgs.pdf.

- Pemberton MR, Colliver JD, Robbins JM, Gfroerer JC. Underage alcohol use: findings from 2001–2006 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (DHHS Publication No. SMA 08 4333, Analytic Series, A-30) Rockville MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Portnoy DB, Scott-Sheldon LAJ, Johnson B, Carey MP. Computer-delivered interventions for health promotion and behavioral risk reduction: a meta-analysis of 75 randomized controlled trials, 1988–2007. Prev Med. 2008;47:3–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocky Mountain Behavioral Institute. American Drug and Alcohol Survey. Fort Collins CO: 2003. [Retrieved May 5, 2009]. from http://www.rmbsi.com/index.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts ST, Kennedy BL. Why are young college women not using condoms? their perceived risk, drug use, and developmental vulnerability may provide important clues to sexual risk. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2006;20:32–40. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schinke SP, Schwinn TM, Di Noia J, Cole KC. Reducing the risks of alcohol use among urban youth: 3-year effects of a computer-based intervention with and without parent involvement. J Stud Alcohol. 2004;65:443–450. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seiffge-Krenke I. Stress, coping, and relationships in adolescence. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens SJ, Murphy BS, McKnight K. Traumatic stress and gender differences in relationship to substance abuse, mental health, physical health, and HIV risk behavior in a sample of adolescents enrolled in drug treatment. Child Maltreat. 2003;8:46–57. doi: 10.1177/1077559502239611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Burton EM, Shaw H. Prospective relations between bulimic pathology, depression, and substance abuse: unpacking comorbidity in adolescent girls. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72:62–71. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.1.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson NR, Zand DH. The Harter self-perception profile for adolescents: psychometrics for an early adolescent, African-American sample. Int J Test. 2002;2:297–310. [Google Scholar]

- Trudeau L, Spoth R, Randall GK, Azevedo K. Longitudinal effects of a universal family-focused intervention on growth patterns of adolescent internalizing symptoms and polysubstance use: gender comparisons. J Youth Adol. 2007;36:725–740. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace JM, Bachman JG, O'Malley PM, Schulenberg JE, Cooper SM, Johnston LD. Gender and ethnic differences in smoking, drinking and illicit drug use among American 8th, 10th and 12th grade students, 1976–2000. Addiction. 2003;98:225–234. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood MD, Mitchell RE, Read JP, Brand NH. Do parents still matter? parent and peer influences on alcohol involvement among recent high school graduates. Psychol Addict Behav. 2004;18:19–30. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]