Abstract

Epilobium angustifolium has been traditionally used to treat of a number of diseases; however, not much is known regarding its effect on innate immune cells. Here, we report that extracts of E. angustifolium activated functional responses in neutrophils and monocyte/macrophages. Activity-guided fractionation, followed by mass spectroscopy and NMR analysis, resulted in the identification of oenothein B as the primary component responsible for phagocyte activation. Oenothein B, a dimeric hydrolysable tannin, dose-dependently induced a number of phagocyte functions in vitro, including intracellular Ca2+ flux, production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), chemotaxis, nuclear factor (NF)-κB activation, and proinflammatory cytokine production. Furthermore, oenothein B was active in vivo, inducing keratinocyte chemoattractant (KC) production and neutrophil recruitment to the peritoneum after intraperitoneal administration. Biological activity required the full oenothein B structure, as substructures of oenothein B (pyrocatechol, gallic acid, pyrogallol, 3,4-dihydroxybenzoic acid) were all inactive. The ability of oenothein B to modulate phagocyte functions in vitro and in vivo suggests that this compound is responsible for at least part of the therapeutic properties of E. angustifolium extracts.

Keywords: oenothein B, Epilobium angustifolium, macrophage, neutrophil, reactive oxygen species, cytokines

Introduction

Enhancement of innate immunity by immunomodulators can increase host resistance to pathogens (1), and a number of innate immunomodulators have been identified, including cytokines (2), substances isolated from microorganisms and fungi (3), and substances isolated from plants (4,5). However, many of these substances are high molecular weight carbohydrates (6) or lectins (7), and only a few plant-derived compounds with a relatively low molecular weight are known to modulate phagocyte functions, e.g., taxol (8), phenylpropanoid glycoside acteoside (9), and alkylamides from Echinacea purpurea (10). Thus, there is a significant amount of interest in identifying low molecular weight compounds with potential medicinal properties.

The genus Epilobium is widely distributed around the world and consists of over 200 species, with the most common being Epilobium angustifolium L. Various members of the genus Epilobium have been used in folk medicine to treat a variety of diseases and enhance wound healing (reviewed in (11)). Indeed, extracts from Epilobium taxa have been shown in both in vitro and in vivo studies to exhibit many therapeutic properties, including anti-inflammatory (12), antiandrogenic (13), antiproliferative (14,15), antifungal (16,17), antimicrobial (18,19), antinociceptive (20,21), and antioxidant (22,23) effects.

Although the active components responsible for therapeutic effects of Epilobium are not well defined, one of the classes of bioactive compounds present in Epilobium species is the ellagitannins (24). Ellagitannins are plant polyphenols, and previous studies have shown that some ellagitannins (e.g., coriariin A) exhibit immunomodulatory activity (25). Oenothein B, a dimeric macrocyclic ellagitannin, has been reported to be one of the main biologically-active components in Epilobium taxa, and this compound is present in high concentrations in Epilobium species (24). Previous studies on oenothein B have shown that oenothein B exhibits significant antioxidant (26), antitumor (14,27–30), antibacterial (31), and antiviral (32) activities. Although polyphenols are known for their antioxidant activity, recent evidence indicates that the therapeutic effects of these compounds is not solely due to antioxidant properties and that they can directly modulate cellular responses (reviewed in (33)). For example, it has been reported that oenothein B has antitumor activity and that this may be due to enhancement of the host-immune system via induction of interleukin (IL)-1β (27). However, little else has been reported on the effects of oenothein B on innate immunity. Thus, we evaluated the effects of E. angustifolium extracts on phagocyte function.

Here, we report that E. angustifolium extracts can activate phagocyte functional responses. Furthermore, fractionation of the extracts indicated that the active component was oenothein B. Oenothein B activated monocyte/macrophages and neutrophils, resulting in increased intracellular Ca2+ flux, production of ROS and cytokines, and chemotaxis. Thus, part of the observed therapeutic effects of oenothein B and Epilobium extracts is due to modulation of innate immune function.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

Corilagin (1-O-galloyl-3,6-hexahydroxydiphenol-β-D-glucopyranose) was from Toronto Research Chemicals (Toronto, ON, Canada); 1,2,3,4,6-pentakis-O-galloyl-β-D-glucose (PGG) was from Sinova (Bethesda, MD); and 8-Amino-5-chloro-7-phenylpyridol [3,4-d]pyridazine-1,4(2H,3H)-dione (L-012) was obtained from Wako Chemicals (Richmond, VA). Pyrocatechol, gallic acid, pyrogallol, 3,4-dihydroxybenzoic acid, Sephadex LH-20 (25–100 µm), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), deuterium oxide (D2O), ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), ionomycin, horseradish peroxidase, N-formyl-Met-Leu-Phe (fMLF), horseradish superoxide dismutase, Percoll, HEPES, Histopaque 1077, Histopaque 1119, lipopolysaccharide (LPS) from Escherichia coli K-235, phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA), xanthine oxidase from bovine milk, xanthine, nitro blue tetrazolium (NBT), and zymosan A from Saccharomyces cerevisiae were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO). IL-8 was purchased Peprotech (Rocky Hill, NJ). Acetone-d6 was from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Inc. (Andover, MA). HPLC grade acetonitrile and methanol were from EMD Chemicals (Gibbstown, NJ), and HPLC grade H2O and trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) were from Mallinckrodt Baker Inc. (Phillipsburg, NJ). Hanks' balanced salt solution, pH 7.4, with and without Ca2+ and Mg2+ (HBSS+ and HBSS−, respectively), and enzyme-free cell dissociation buffer were from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). RPMI 1640 medium was purchased from Mediatech (Herdon, VA). Percoll stock solution was prepared by mixing Percoll with 10X HBSS at a ratio of 9:1.

Serum-opsonized zymosan was prepared by incubating zymosan A with murine or human serum for 45 min at 25°C. After centrifugation (800g for 10 min), the zymosan particles were washed and resuspended in HBSS−.

Extraction and isolation of active compound

Fully blossomed E. angustifolium were collected and identified by Robyn A. Klein (Department of Plant Sciences and Plant Pathology, Montana State University, Bozeman, MT). The dried plant material (400 g) was extracted with 80% methanol at room temperature for 3 days. The combined extracts were concentrated, and any precipitates were removed by filtration through a 0.22 µm filter. The filtrate was lyophilized to obtain the crude extract or subjected to concentration and fractionation on a Sephadex LH-20 column (2.8x33 cm) using 80% methanol as an eluent. The relevant fractions were pooled and evaporated to dryness. For analysis of biological activity, the crude extract and pooled fractions were dissolved in DMSO. Bioactive subfraction S-3 was rechromatographed twice on a Sephadex LH-20 column (2.5x25 cm) using 80% methanol as the mobile phase, resulting in 180 mg of the final product. All lyophilized extracts and fractions were stored at −20°C until use. For biological assays, the samples were dissolved in HBSS− (ROS production and Ca2+ flux assays) or RPMI (cytokine production and NF-κB activity).

Compound identification

For NMR analysis, samples (5 mg) were dissolved in 0.5 ml D2O or acetone-d6 with 2% (v/v) D2O, and 1H spectra were recorded on a Bruker DRX-600 spectrometer (Bruker, Billerica, MA) at 20°C using 3-(trimethylsilyl)-propionic 2,2,3,3,-d4 acid sodium salt as an internal reference. For 13C-NMR, the spectra were recorded on a Bruker DRX-500 spectrometer at 20°C.

Mass spectrometry experiments were performed using a Bruker Microtof high resolution time of flight mass spectrometer. Ionization was achieved using standard electrospray conditions, and data were acquired in positive mode with the following settings: nitrogen drying gas temperature 200°C, drying gas flow rate 3 L/min, nebulizer pressure 0.2 Bar, and capillary voltage was 4000 V. Each sample was dissolved in HPLC grade methanol and directly infused into the mass spectrometer. The full mass scan ranged between (m/z) 100 and 1700 Da.

Purity of isolated oenothein B was determined by reverse-phase HPLC on an automated HPLC system (Shimadzu, Torrance, CA) with a Phenomenex Jupiter C18 300A column (5 µm, 250×4.6 mm) eluted with acetonitrile/water (16/84, v/v) containing 0.1% (v/v) trifluoracetic acid at a flow rate of 1 ml/min and detection at 270 nm, at 30 °C over 15 min (34). Purity was >95% based on reversed-phase HPLC and mass spectroscopic analysis.

Endotoxin assays

A Limulus Amebocyte Lysate (LAL) assay kit (Cambrex, Walkersville, MD) was used to evaluate isolated oenothein B for possible endotoxin contamination, according to the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, the LAL was reconstituted in 250 µl of isolated oenothein B dissolved in endotoxin-free 0.05 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.2, and each vial was incubated at 37°C for 1 h. At the end of the incubation period, each vial was inverted 180° to estimate gel formation compared with control (endotoxin-free buffer).

To further evaluate the possible role of endotoxin, isolated oenothein B dissolved in elution buffer (0.05 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.2 containing 0.5 M NaCl) was applied to a column containing Detoxi-Gel Endotoxin Removing Gel (Pierce, St. Louis, MO). The concentration of oenothein B in the eluted sample was adjusted to match that of the untreated fraction, as determined by UV spectroscopy at 265 nm, and both treated and untreated samples were analyzed for biological activity.

Cell culture

Human monocytic THP-1Blue cells obtained from InvivoGen (San Diego, CA) were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 µg/ml streptomycin, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 µg/ml Zeocin, and 10 µg/ml blasticidin S. THP-1Blue cells are stably transfected with a secreted embryonic alkaline phosphatase gene that is under the control of a promoter inducible by nuclear factor κB (NF-κB).

Human leukemia HL-60 cells were cultured in RPMI supplemented with 10% (v/v) heat inactivated FCS, 10 mM HEPES, 100 µg/ml streptomycin, and 100 U/ml penicillin. HL-60 cells were differentiated to macrophage-like cells by treatment with 10 nM PMA for 3 days (35). All cultured cells were grown at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. Cell number and viability were assessed microscopically using trypan blue exclusion.

Isolation of murine bone marrow leukocytes and neutrophils

All animal use was conducted in accordance with a protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Montana State University. Murine bone marrow cells were flushed from tibias and femurs of BALB/c mice with HBSS using a syringe with 27-gauge needle. The cells were resuspended by gentle pipetting and filtered through 70 µm nylon cell strainers (Becton Dickinson) to remove cell clumps and bone particles, and resuspended in HBSS− at 106 cells/ml (36). This procedure minimizes phagocyte activation during isolation and, thus, their function more accurately reflects the physical condition of these cells in vivo. ROS-generation in bone marrow leukocyte preparations is primarily due to neutrophils and macrophages (37).

Bone marrow neutrophils were isolated from bone marrow leukocyte preparations, as described previously (36). Leukocyte pellets prepared as described above were resuspended in 3 ml of 45% Percoll solution and layered on top of a Percoll gradient consisting of 2 ml each of 50, 55, 62, and 81% Percoll solutions in a conical 15-ml polypropylene tube. The gradient was centrifuged at 1600g for 30 min at 10°C, and the cell band located between the 61 and 81% Percoll layers was collected. The cells were washed, layered on top of 3 ml of Histopaque 1119, and centrifuged at 1600g for 30 min at 10°C to remove contaminating red blood cells. The purified neutrophils were collected, washed, and resuspended in HBSS−.

Isolation of human neutrophils and mononuclear cells

Blood was collected from healthy donors in accordance with a protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board at Montana State University. Neutrophils and mononuclear cells (MNC) were purified from the blood using dextran sedimentation, followed by Histopaque 1077 gradient separation and hypotonic lysis of red blood cells, as described previously (38). Isolated neutrophils were washed twice and resuspended in HBSS−. Neutrophil preparations were routinely >95% pure, as determined by light microscopy, and >98% viable, as determined by trypan blue exclusion. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated from blood using dextran sedimentation and Histopaque 1077 gradient separation (39).

Analysis of phagocyte ROS production

ROS production was determined by monitoring L-012-enhanced chemiluminescence, which represents a sensitive and reliable method for detecting superoxide anion (O2-.) production in vitro (40). Briefly, phagocytes were aliquoted into wells (105 cells/well) of 96-well flat-bottomed white microplates, and test extracts or lyophilized fractions diluted in DMSO were added (final DMSO concentration of 1%). After preincubation at 37°C for the indicated times, an equal volume of 0.05% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in HBSS− was added to each well, the plates were centrifuged, the media was removed, and fresh HBSS+ supplemented with 40 µM L-012 and 8 µg/mL HRP was added. In some experiments, the plates were read directly without replacing the media to evaluate PMA- or zymosan-stimulated ROS production in the presence of the oenothein B or total E. angustifolium extract. Luminescence was monitored for 60 min (2-min intervals) at 37°C using a Fluroscan Ascent FL microplate reader (Thermo Electron, Waltham, MA). The curve of light intensity (in relative luminescence units) was plotted against time, and the area under the curve was calculated as total luminescence.

Xanthine/xanthine oxidase system

O2.- was generated in an enzymatic system consisting of 500 µM xanthine, 500 µM NBT, 3.75 mU/mL xanthine oxidase, and 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.5), and O2.- production was determined by monitoring reduction of NBT to monoformazan dye at 560 nm in the presence or absence of oenothein B. The reactions were monitored with a SpectraMax Plus microplate spectrophotometer at 27°C. To evaluate if oenothein B affected the generation of O2.- by direct interaction with xanthine oxidase, enzyme activity was evaluated by spectrophotometric measurement of uric acid formation from xanthine at 295 nm (41). The reaction mixture contained 500 µM xanthine, 5 mU/mL xanthine oxidase, and 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.5), and the reaction was monitored in the presence or absence of oenothein B at 27°C.

Ca2+ mobilization assay

Changes in intracellular Ca2+ were measured with a FlexStation II scanning fluorometer using a FLIPR 3 Calcium Assay Kit (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Human and murine neutrophils or HL-60 cells, suspended in HBSS− containing 10 mM HEPES, were loaded with FLIPR Calcium 3 dye following the manufacturer's protocol. After dye loading, Ca2+ was added to the cell suspension (2.25 mM final), and cells were aliquotted into the wells of a flat-bottomed black microplate (2×105 cells/well). The compound source plate contained dilutions of E. angustifolium extract or test compounds in HBSS+ or DMSO. Changes in fluorescence were monitored (λex = 485 nm, λem = 525 nm) every 5 s for 120 s at room temperature after automated addition of compounds to the wells. Maximum change in fluorescence, expressed in arbitrary units over baseline signal observed in cells treated with vehicle (HBSS+ or DMSO), was used to determine agonist response. Curve fitting and calculation of median effective concentration values (EC50) were performed by nonlinear regression analysis of the dose-response curves generated using Prism 5 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA).

Chemotaxis assay

Human neutrophils were suspended in HBSS+ containing 2% (v/v) FBS (2×106 cells/ml), and chemotaxis was analyzed in 96-well ChemoTx chemotaxis chambers (Neuroprobe, Gaithersburg, MD), as described previously (42). In brief, lower wells were loaded with 30 µl of HBSS+ containing 2% (v/v) FBS and the indicated concentrations of E. angustifolium extract, test compound, vehicle control (DMSO or HBSS−), or 50 nM IL-8 as a positive control. The number of migrated cells was determined by measuring ATP in lysates of transmigrated cells using a luminescence-based assay (CellTiter-Glo; Promega, Madison, WI), and luminescence measurements were converted to absolute cell numbers by comparison of the values with standard curves obtained with known numbers of neutrophils. The results are expressed as percentage of negative control and were calculated as follows: (number of cells migrating in response to test compounds/spontaneous cell migration in response to control medium)×100. EC50 values were determined by nonlinear regression analysis of the dose-response curves generated using Prism 5 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

Cytokine analysis

Cells were incubated for 24 hr in culture media supplemented with 3% (v/v) endotoxin-free FBS, with or without compounds or LPS as a positive control. Human PBMCs and THP-1Blue human monocytic cells were plated in 96-well plates at a density of 2×105 cells/well. A human cytokine Multi-Analyte ELISArrayTM Kit (SABiosciences Corp., Frederick, MD) was utilized to evaluate various cytokines [interleukin (IL)-1α, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, IL-12, IL-17A, interferon-γ, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF)] in supernatants of peripheral blood mononuclear cells or THP-1Blue monocytes. Human TNF-α or IL-6 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (BD Biosciences Pharmigen) were used to confirm TNF-α or IL-6 levels in the cell supernatants. Cytokine concentrations were determined by extrapolation from cytokine standard curves, according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Analysis of NF-κB activation

Activation of NF-κB was measured using an alkaline phosphatase reporter gene assay in THP1-Blue cells. Extracts, compounds, or LPS (100 ng/ml) were added, the cells (2×105 cells/well) were incubated for 24 h, and alkaline phosphatase activity was measured in cell supernatants using QUANTI-Blue mix (InvivoGen, San Diego, CA). Activation of NF-κB is reported as an absorbance at 655 nm and compared with positive control samples (LPS).

Cytotoxicity assay

Cytotoxicity was analyzed with a CellTiter-Glo Luminescent Cell Viability Assay Kit (Promega, Inc., Madison, WI), according to the manufacturer's protocol. Following treatment, the cells were allowed to equilibrate to room temperature for 30 min, substrate was added, and the samples were analyzed with a Fluoroscan Ascent FL.

In vivo analysis

Oenothein B was resuspended in saline and inject intraperitoneally into 8–12 week old female BALB/c mice. At 4 hr post-injection, the mice were euthanized, their peritoneal cavities were washed with 5 mL of HBSS, and the fluid was collected and centrifuged at 500g for 5 min. The resulting cell preparation was subjected to flow cytometric analysis using standard techniques. Briefly, peritoneal cells were stained with FITC-conjugated RB6-8C5 (anti-GR-1; pan neutrophil stain), APC-conjugated anti-CD45.2 (pan-leukocyte stain; disregards red blood cells, epithelial cells, and fibrobalsts), and phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated anti-CD11b (stains macrophages and neutrophils, bright on highly activated cells). All incubation and wash buffers contained 2% horse serum to minimize background staining of the cell preparations. The samples were analyzed on a FACSCalibur equipped with a high-throughput sampler (HTS) (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Viable leukocytes were gated based on forward-scatter/side-scatter and positive staining for CD45. Of the viable CD45+ leukocytes, the percentage of neutrophils (identified by distinctive light scatter and staining of GR-1bright/CD11bpositive) was determined.

In some experiments, serum samples were collected, and KC levels were quantified by using a Mouse KC Quantikine ELISA kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). Assay plates were read at 450 nm using a Molecular Devices VERSAMax microplate reader (Sunnydale, CA). KC levels were determined by extrapolation from recombinant KC standard curves, according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Prism 5. The data were analyzed by one way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Tukey’s Multiple Comparison Test, with the exception of the data from in vivo experiments, which were analyzed by Student’s t-test. Statistically significant differences (P<0.05 or better) compared to the appropriate controls are indicated.

Results

Effect of E. angustifolium extract on ROS production and NF-κB activity

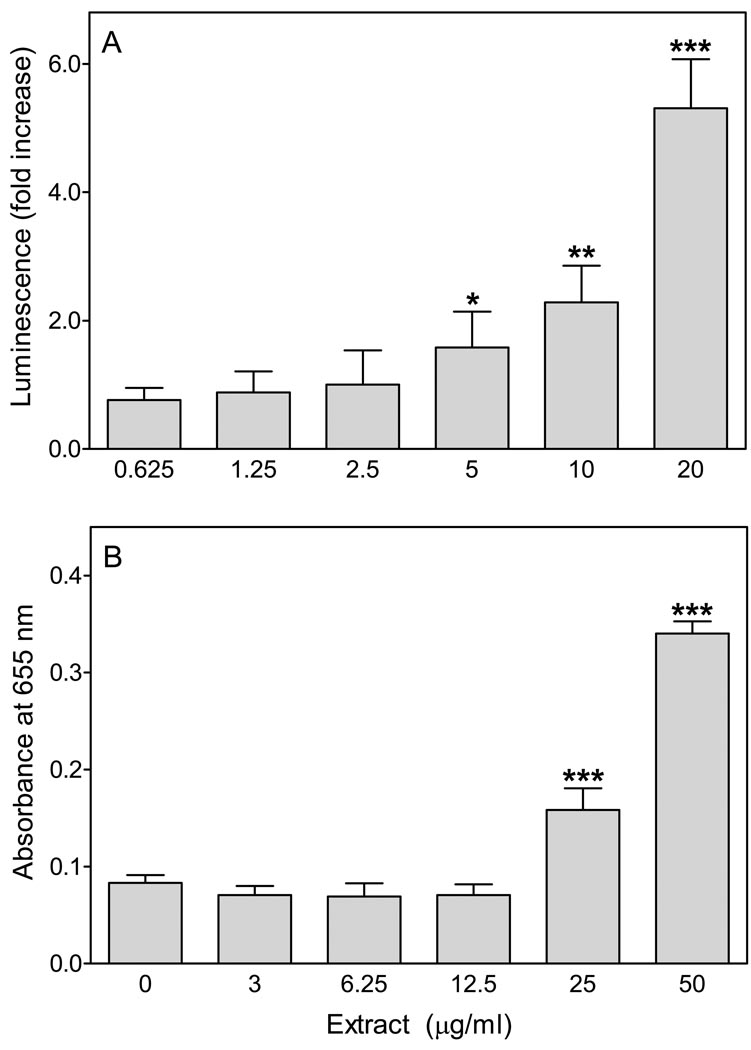

To evaluate the effects of E. angustifolium extracts on phagocyte functional responses, we analyzed the effects of methanol extracts from this plant on phagocyte ROS production and NF-κB activation. As shown in Figure 1, extracts from E. angustifolium dose-dependently activated ROS production in murine bone marrow leukocytes and induced NF-κB in human THP-1 monocytes.

Figure 1.

Effect of E. angustifolium extract on ROS production in bone marrow leukocytes and NF-κB activity in THP-1Blue monocytes. Panel A. Murine bone marrow cells (105 cells/well) were treated with the indicated concentrations of plant extract or vehicle (1% DMSO) and incubated for 30 min at 37°C. The media was removed and replaced with HBSS+ containing L-012 and HRP, and chemiluminescence was monitored for 60 min. Fold increase (FI) of integrated chemiluminescence (for 60 min) was calculated in comparison with vehicle control. Panel B. Human THP1-Blue monocytes (2×105 cells/well) were incubated for 24 hr with the indicated concentrations of plant extract or vehicle (1% DMSO). Alkaline phosphatase release was analyzed spectrophotometrically in the cell supernatant, as described. For both panels, the data are presented as mean±S.D. of triplicate samples from one experiment that is representative of three independent experiments. Statistically significant differences (*P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001) versus DMSO control are indicated.

Identification of the phagocyte-activating component in E. angustifolium extract

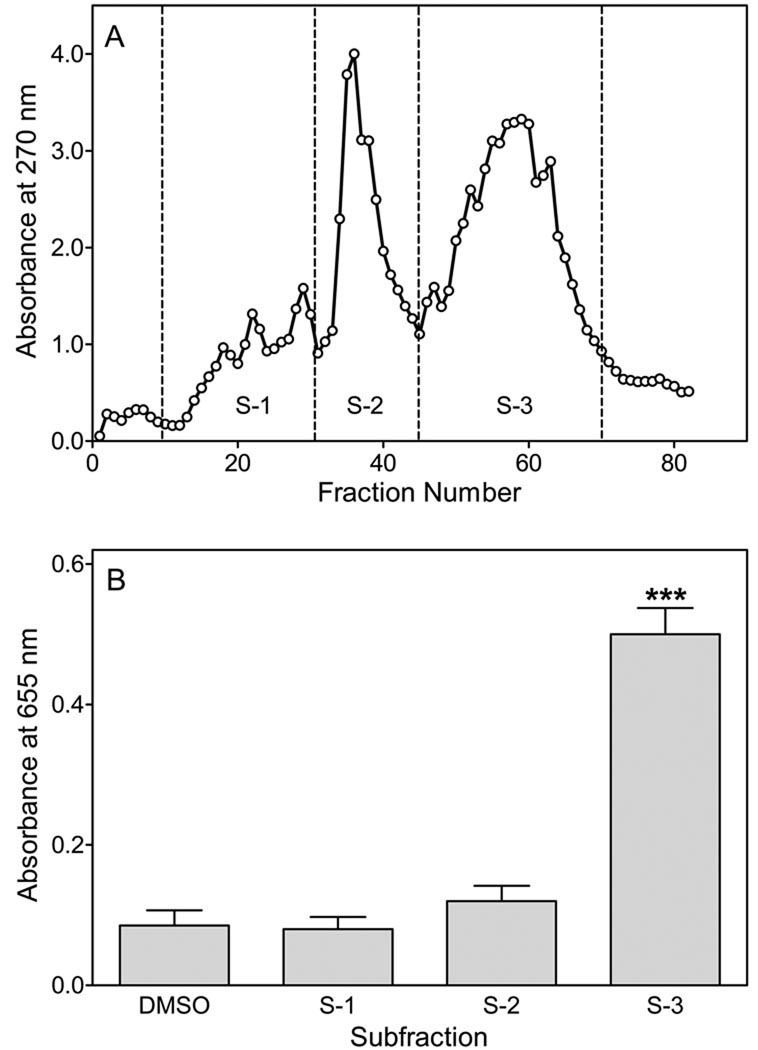

Based on these results, we fractionated the extract in efforts to identify the active component in this crude mixture. Concentrated methanol extract from E. angustifolium was fractionated by preparative Sephadex LH-20 chromatography and sixty 10-ml fractions were collected (Figure 2A). These fractions were pooled into three subfractions, designated as S-1 to S-3, and activity of these subfractions was evaluated in the NF-κB reporter assay. Only subfraction S-3 activated NF-κB in this assay (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Fractionation of methanol extract from E. angustifolium. Panel A. Crude methanol extract was isolated from florets of E. angustifolium, concentrated, and fractionated using Sephadex LH-20 column chromatography. Fractions were collected and pooled based on elution profile (absorbance at 270 nm). Panel B. THP1-Blue monocytes (2×105 cells/well) were incubated for 24 hr with the pooled subfractions (final concentration 50 µg/ml) or vehicle (1% DMSO), and alkaline phosphatase release was analyzed spectrophotometrically in the cell supernatant, as described. The data are presented as mean±S.D. of triplicate samples from one experiment that is representative of three independent experiments. Statistically significant differences (***P<0.001) versus DMSO control are indicated.

The pooled subfraction S-3 was re-chromatographed twice more on a Sephadex LH-20 to obtain the final sample, which was concentrated to dryness and analyzed by HPLC, mass spectroscopy, and 1H- and 13C-NMR (Supplemental Table S1). Based on comparison of mass spectroscopy and NMR data with those in the literature (34,43–45), we found that the active component present in subfraction S-3 isolated from E. angustifolium was oenothein B (Mr=1568; structure of the compound is shown in Supplemental Figure S1).

As shown in Supplemental Figure S2, the mass spectrum was characterized by the presence of monosodium (M + Na)+ at m/z 1592.1 (1 m/z unit separation between isotopic peaks) and doubly-charged disodium (M + 2Na)2+ at m/z 807.1 (0.5 m/z unit separation between peaks) adducts of oenothein B. The prominent series at m/z 1068.7 is apparently a non-covalent dimeric aggregate of the monosodium and disodium adducts. It should be noted that time-of-flight mass spectroscopy of polyphenols, including ellagitannins, tends to favor association with sodium ions because naturally occurring Na+ ions are abundant in these samples (46,47).

The 1H-NMR spectrum of our sample in D2O contained six 1H-singlets and two 2H-singlets in the aromatic region (Supplemental Table S1), which is in agreement with the presence of two galloyl and two valoneoyl moieties in oenothein B. Two glucopyranose residues gave well-resolved signals of sugar protons, with characteristic coupling similar to that of the oenothein B spectrum in acetone (44). Anomeric proton doublets appeared at δ 4.47 (J 9 Hz) and 5.47 (J 3.4 Hz), indicating that the anomeric hydroxyls of both glucose residues were non-acylated. Although an equilibrium occurs between the α- and β-forms of each of the glucopyranose rings, the 1H-NMR spectrum showed that the α-form dominates one ring, whereas the β-form dominates the other glucopyranose moiety. This is in contrast to oenothein F, an isomer of oenothein B, where a mixture of anomeric forms for both rings results in a more complex 1H-NMR spectrum (43). Since previous NMR analysis of oenothein B has been performed in acedone-d6, we obtained additional 1H-NMR spectra of our sample in acedone-d6 with 2% (v/v) D2O. Although some of the signals were overlapped by the broad singlet of residual water protons, many signals characteristic of oenothein B were observed. For example, resonances of α-glucose H-1 at δ 6.17 (d, J 3 Hz) and of β-glucose H-5 at δ 4.11 (dd, J1 5, J2 10 Hz) are very similar to the corresponding signals of oenothein B reported previously [δ 6.18 and δ 4.12, respectively, in acetone-d6–D2O (43); δ 6.24 and δ 4.14, respectively, in acetone-d6 (44)]. These values are quite distinct from any glucose chemical shifts in the 1H-NMR spectrum of oenothein D (43). Eight singlets of galloyl and valoneoyl aromatic rings in the spectrum of our isolated sample were also very close (rms deviation of 0.07 ppm) to the corresponding signals reported for oenothein B in acetone-d6 (44). Note that chemical shifts of aromatic moieties differ significantly between oenothein isomers, and galloyl and valoneoyl NMR signals for oenothein D and oenothein F are in quite different positions than for oenothein B (43). Taken together, our data demonstrate that the primary phagocyte-activating component of E. angustifolium extract is oenothein B.

Effect of oenothein B on ROS production

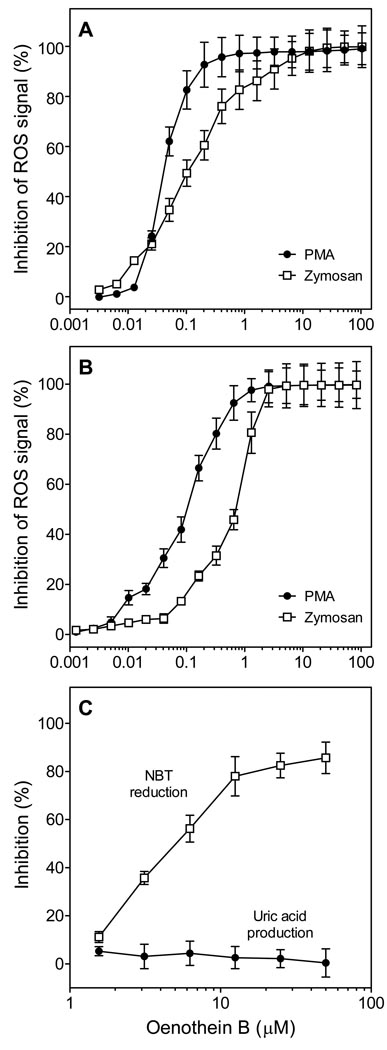

In studies described above, the E. angustifolium extract and subfractions were removed from the cells and replaced with fresh media prior to analysis of ROS production by treated phagocytes. We used this approach to avoid antioxidant effects of potential plant-derived compounds, as it is known that E. angustifolium extract contains flavonoids, such as myricetin, kaempferol, and quercetin, which have antioxidant activity (45,48,49). To directly evaluate this issue, we analyzed potential scavenging effects of crude E. angustifolium extract or oenothein B on ROS produced by zymosan- and PMA-stimulated murine bone marrow leukocytes and human neutrophils. We found that the ROS signal was dose-dependently decreased when crude extract (5–20 µg/ml; data not shown) or oenothein B were present. Indeed, the ROS signal was completely lost when oenothein B was present in the assay at concentrations >2–3 µM (Figure 3). IC50 values were 50 and 90 nM oenothein B for scavenging ROS produced by PMA-stimulated human neutrophils and murine bone marrow leukocytes, respectively, and 110 and 505 nM oenothein B for scavenging ROS produced by zymosan-stimulated human neutrophils and murine bone marrow leukocytes, respectively. Since ROS are generated extracellularly by PMA-stimulated cells, whereas zymosan-stimulated cells generate intracellular ROS, which then can diffuse out of the cell, it is not surprising that oenothein B had lower IC50 values for scavenging ROS in the PMA-stimulated cell system.

Figure 3.

Analysis of oenothein B antioxidant activity. Human neutrophils (Panel A) or murine bone marrow leukocytes (Panel B) were aliquotted into microplate wells (105 cells/well) and treated with 200 nM PMA or 100 µg/ml opsonized zymosan particles and the indicated concentrations of oenothein B. Chemiluminescence was monitored immediately for 1 hr in the presence of 25 µM L-012. Panel C. The indicated concentrations of oenothein B were added to the xanthine/xanthine oxidase system. For analysis of antioxidant activity, NBT reduction was determined. For analysis of xanthine oxidase inhibition, uric acid production was determined. For all panels, the data are presented as mean±S.D. of triplicate samples from one experiment that is representative of three independent experiments.

To verify oenothein B was an effective ROS scavenger, we analyzed scavenging activity in an enzymatic, O2--generating system. As shown in Figure 3C, oenothein B (1–50 µM) effectively scavenged O2- in a xanthine/xanthine oxidase assay. To confirm the effect of oenothein B was due to ROS scavenging and not direct inhibition of xanthine oxidase itself, we measured xanthine oxidase-dependent production of uric acid from xanthine and found no effect of oenothein B over the entire concentration range tested (Figure 3C). Thus, it is clear that, in addition to its phagocyte-activating properties, oenothein B is an effective scavenger of phagocyte-derived ROS, which is consistent with previous reports demonstrating oenothein B has antioxidant properties (26).

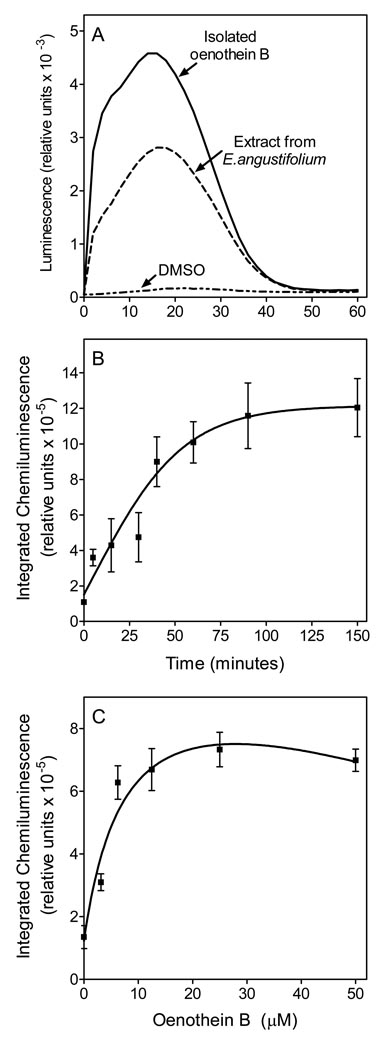

In order to eliminate or decrease antioxidant effects of the compounds/extract under investigation, the media containing test samples was removed and replaced with fresh media prior to subsequent analysis of ROS production. As shown in Figure 4A, the kinetics of murine bone marrow leukocyte ROS production induced by E. angustifolium extract and isolated oenothein B were similar, and ROS production was induced in a time-dependent manner by oenothein B (Figure 4B). Likewise, purified murine neutrophils dose-dependently generated ROS in response to oenothein B (Figure 4C). At concentrations of 10–50 µM oenothein B, the response plateaued, which may be due to competing antioxidant activity of compounds remaining even after media replacement. SOD (50 U/ml) completely (>95%) inhibited ROS production in oenothein B-stimulated neutrophils (data not shown), indicating the response was primarily due to NADPH oxidase-generated O2-.

Figure 4.

Effect of E. angustifolium extract and oenothein B on ROS production in murine bone marrow leukocytes and neutrophils. Panel A. Murine bone marrow leukocytes (105 cells/well) were treated with extract (50 µg/ml) or oenothein B (25 µM) for 2 hr. The media was removed and replaced with HBSS+ containing L-012 and HRP, and chemiluminescence was monitored for 60 min. Representative of 3 independent experiments. Panel B. Bone marrow leukocytes (105 cells/well) were treated with oenothein B (12.5 µM). At the indicated times, the media was removed and replaced with HBSS+ containing L-012 and HRP, and chemiluminescence was monitored. Panel C. Purified murine neutrophils were treated with the indicated concentrations of oenothein B for 60 min, the media was replaced, and L-012-dependent chemiluminescence was recorded. For panels B and C, the data are presented as mean±S.D. of triplicate samples from one experiment that is representative of three independent experiments.

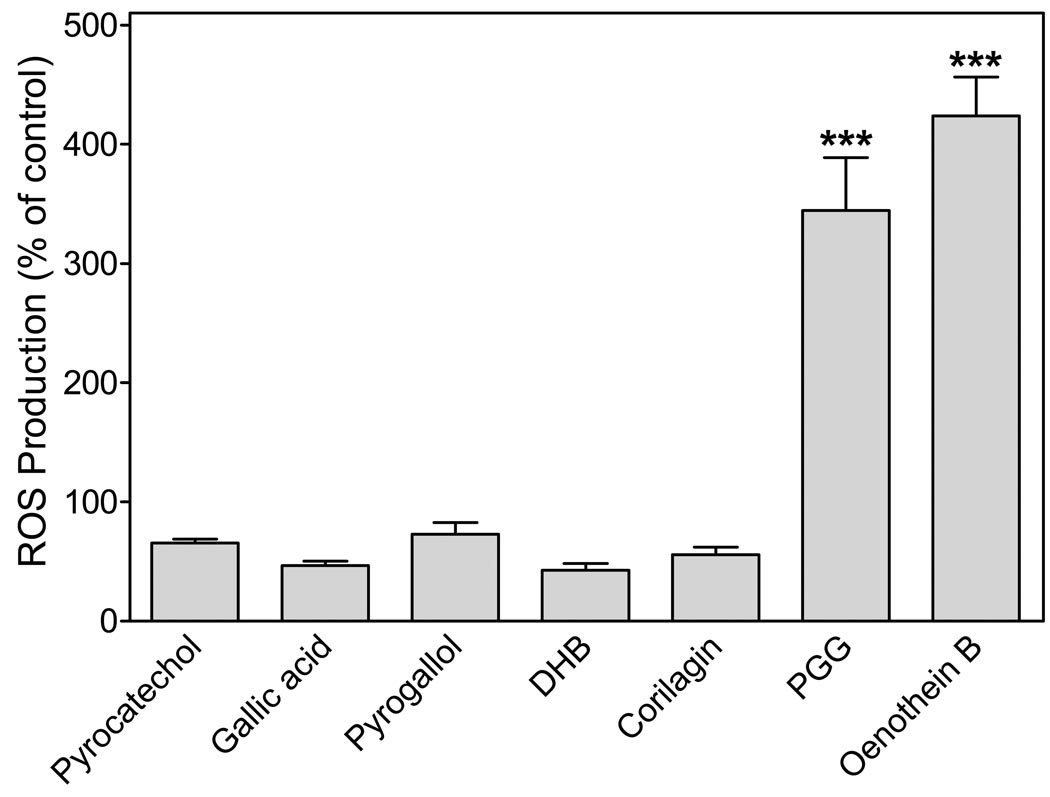

To evaluate the role of oenothein B structural components on phagocyte activation, we evaluated ROS production by phagocytes treated with substructures of oenothein B, including pyrocatechol, gallic acid, pyrogallol, 3,4-dihydroxybenzoic acid, and two related tannins, 1,2,3,4,6-pentakis-O-galloyl-β-D-glucose (PGG) and corilagin (structures of the compounds are shown in Supplemental Figure S3). Only oenothein B and PGG activated ROS production over the concentration range tested (10–100 µM). Figure 5 shows the response to these compounds at selected concentrations, as compared to that induced by 25 µM oenothein B.

Figure 5.

Effect of oenothein B and related compounds on ROS production in bone marrow leukocytes. Bone marrow leukocytes (105 cells/well) were preincubated with the indicated compounds or 1% DMSO (vehicle control) for 60 min. The media was removed and replaced with HBSS+ containing L-012 and HRP, and chemiluminescence was monitored. Concentrations of pyrocatechol, gallic acid, pyrogallol, and 3,4-dihydroxybenzoic acid (DHB) were 100 µM; concentrations of PGG and corilagin were 50 µM; concentration of oenothein B was 25 µM. PGG and corilagin were dissolved in DMSO, whereas all other compounds were dissolved in HBBS. The data are presented as mean±S.D. of triplicate samples from one experiment that is representative of three independent experiments. Statistically significant differences (***P<0.001) versus DMSO control are indicated.

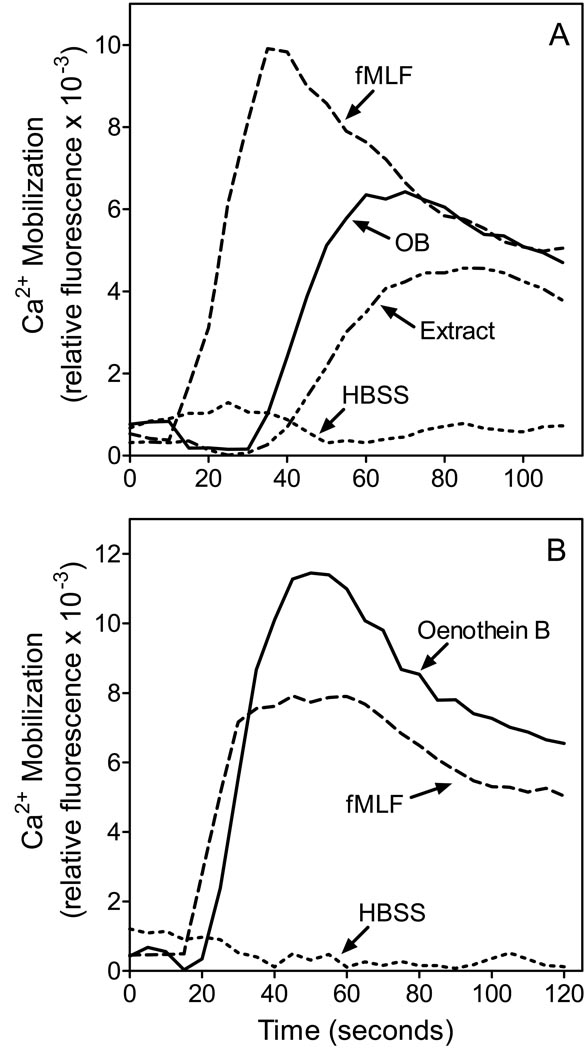

Effect of E. angustifolium extract and purified oenothein B on phagocyte Ca2+ mobilization and chemotaxis

The ability of E. angustifolium extract and oenothein B to induce an intracellular Ca2+ flux in neutrophils was examined. Crude E. angustifolium extract induced a dose-dependent increase in [Ca2+]i in human neutrophils (Figure 6A), with an EC50 of 53 µg/ml. Likewise, oenothein B induced a rapid and dose-dependent Ca2+ flux in human (Figure 6A) and murine neutrophils (Figure 6B), with EC50 values of 25.5 and 18.3 µM, respectively. The peak levels of intracellular Ca2+ were reached within 60 sec of exposure to oenothein B and then decreased. Note however, that [Ca2+]i were still higher than the basal levels at 3 min post-exposure, which is similar to the response observed in cells treated with fMLF (Figure 6). If cells were treated in the absence of extracellular Ca2+, no Ca2+ flux was observed, suggesting that oenothein B treatment induced influx of extracellular Ca2+ (data not shown).

Figure 6.

Representative kinetics of phagocyte Ca2+ mobilization after treatment with E. angustifolium extract and purified oenothein B. Panel A. Human neutrophils were treated with 100 µg/ml E. angustifolium extract, 50 µM oenothein B, 5 nM fMLF, or HBSS and calcium flux was monitored, as described. Panel B. Murine neutrophils were treated with 50 µM oenothein B, 1 µM fMLF, or HBSS and calcium flux was monitored, as described. The data are representative of three independent experiments.

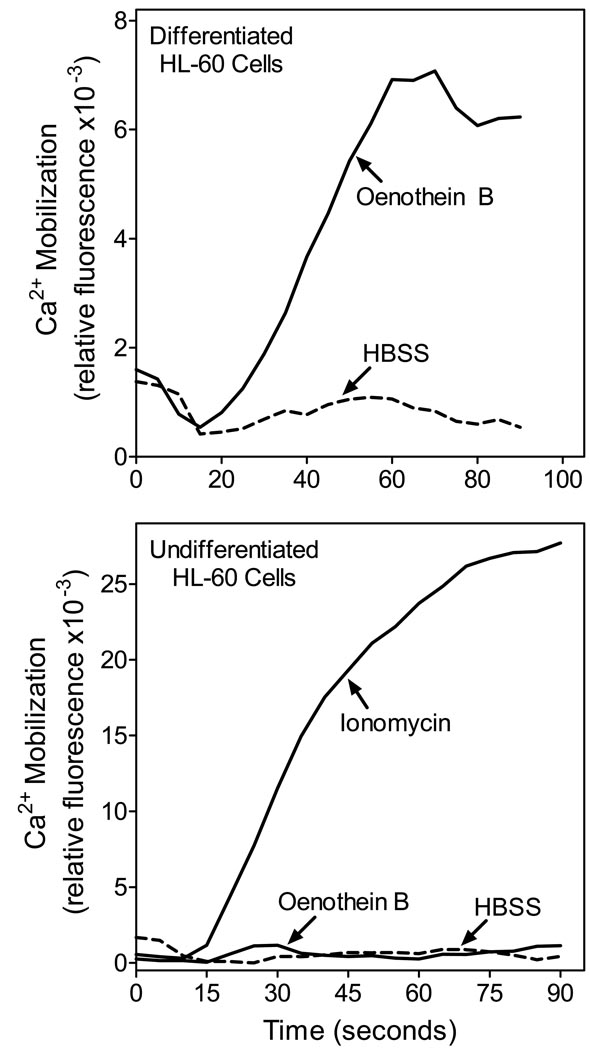

Treatment of PMA-differentiated human HL-60 with oenothein B resulted in an intracellular Ca2+ flux, whereas no significant changes in [Ca2+]i were observed in undifferentiated HL-60 cells (Figure 7, upper panel). In comparison, the Ca2+ ionophore ionomycin increased [Ca2+]i in both non-differentiated and differentiated HL-60 cells (Figure 7, lower panel). These findings suggest that oenothein B does not act as an ion channel and that phagocyte activation by this compound depends on phagocyte differentiation and/or level of receptor expression.

Figure 7.

Analysis of oenothein B-induced Ca2+ mobilization in HL-60 cells. Panel A. HL-60 cells were differentiated with 10 nM PMA for 4 days, the cells were treated with 50 µM oenothein B or control HBSS, and Ca2+ flux was monitored, as described. Panel B. Undifferentiated human HL-60 cells were treated with 50 µM oenothein B, 125 nM ionomycin, or control HBSS and calcium flux was monitored. The data are representative of three independent experiments.

Similar to the results observed for ROS production, pyrocatechol, gallic acid, pyrogallol, 3,4-dihydroxybenzoic acid, and corilagin failed to induce an intracellular Ca2+ flux in human and murine neutrophils, while PGG treatment resulted in increased [Ca2+]i, although with a higher EC50 (31.3 µM) than oenothein B.

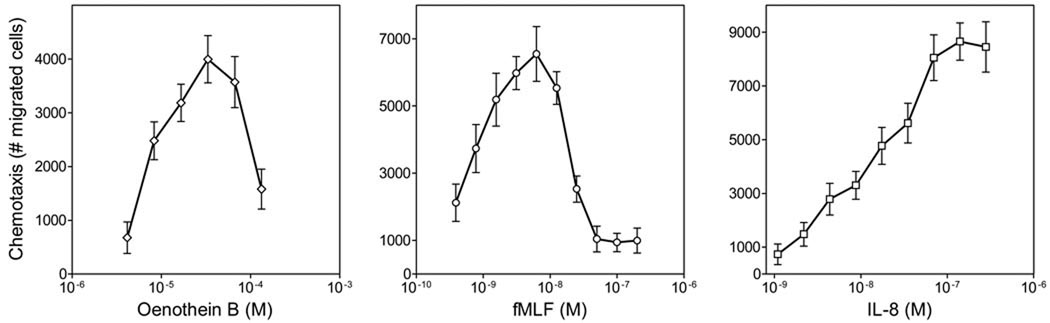

Previous reports indicated that Ca2+ mobilization is associated with chemotactic activity of various agents (50). Thus, we examined the effect of E. angustifolium extract and oenothein B on human neutrophil chemotaxis. Both the extract (data not shown) and purified oenothein B exhibited neutrophil chemotactic activity and dose-dependently induced neutrophil migration, with EC50 values of 46 µg/ml and 11.8 µM, respectively (Figure 8). Note, however, that the magnitude of this response was generally lower than that induced by the positive controls, fMLF and IL-8, which had EC50 values of ~1 and 12 nM, respectively (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Human neutrophil chemotactic response to oenothein B. Neutrophil chemotaxis in response to the indicated concentrations of oenothein B, fMLF, and IL-8 was analyzed in chemotaxis chambers, as described. The data are presented as the number of migrated cells (mean±S.D.; n=3). A representative experiment from three independent experiments is shown.

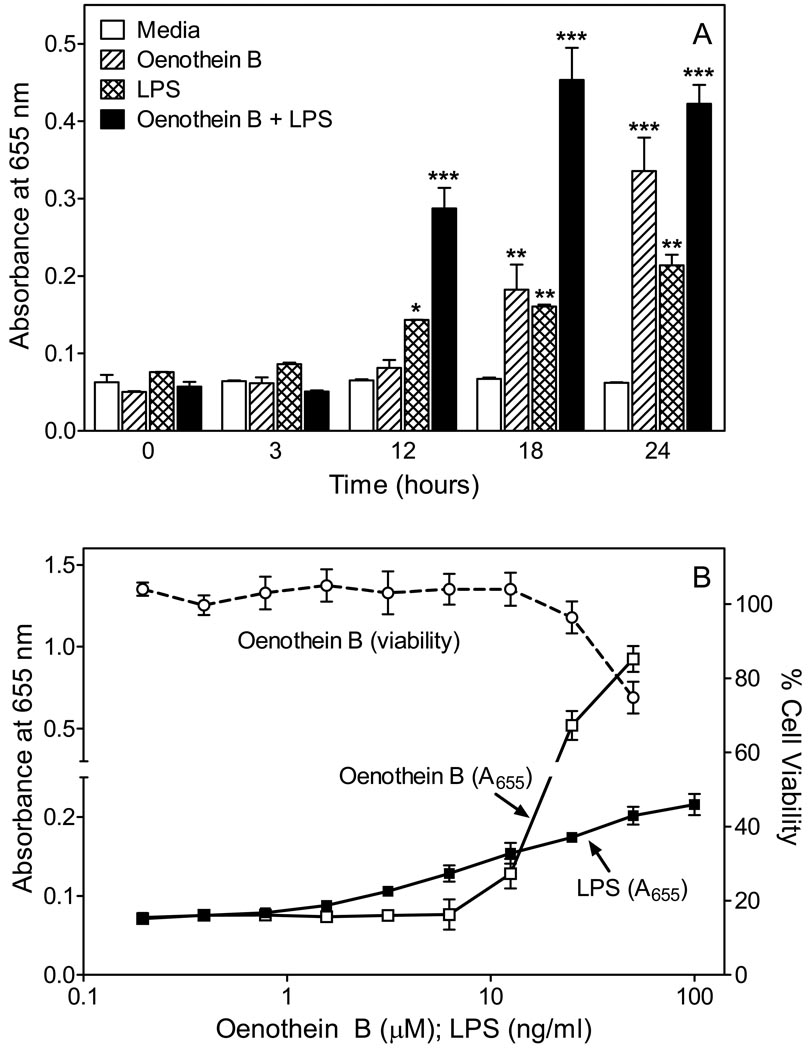

Effect of oenothein B on phagocyte NF-κB activity

To evaluate possible signaling pathways involved in the immunomodulatory activity of oenothein B, we utilized a transcription factor-based bioassay for NF-κB activation in human THP-1 monocytes. NF-κB transcription reporter activity was time-dependently induced by oenothein B (25 µM) and LPS (100 ng/ml), but with slightly different kinetics for these stimuli (Figure 9A). For example, statistically-significant activation of the NF-κB reporter was observed at 12 hr in LPS-treated cells, whereas NF-κB reporter activity induced by oenothein B only reached statistical-significance at 18 hr. Note however, that the response does appear to be increasing in oenothein B-treated cells at 12 hr, and that the level of NF-κB reporter activity induced by oenothein B is equal to or even slightly higher than that induced by LPS at 18 hr. Thus, it is likely that the level of NF-κB reporter activity reaches statistical significance somewhere between 12 and 18 hr in oenothein B-treated cells (Figure 9A), suggesting that oenothein B induces NF-κB with similar or slightly delayed kinetics compared to LPS. As shown in Figure 9B, the response of THP-1 monocytes to oenothein B was dose-dependent, and the level of NF-κB reporter activity induced by oenothein B at concentrations of 25–50 µM far exceeded that induced by 100 ng/ml LPS. Importantly, these concentrations of oenothein B exhibited little toxicity in THP1-Blue cells over the 24 hr assay period (Figure 9B). Finally, treatment of cells with both oenothein B and LPS together led to significantly enhanced responses at 12, 18, and 24 hr, suggesting there was an additive or possibly synergistic effect of these two agents in activating NF-κB and again supporting their similar kinetics of activation (Figure 9A).

Figure 9.

Effect of oenothein B on NF-κB activity and cell viability in THP1-Blue monocytes. Panel A. THP1-Blue monocytes (2×105 cells/well) were incubated for the indicated times with control media, 25 µM oenothein B, 100 ng/ml LPS, or 25 µM oenothein B+100 ng/ml LPS. Alkaline phosphatase release was analyzed spectrophotometrically in the cell supernatant. Statistically significant differences (*P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001) versus media control are indicated. Panel B. THP1-Blue monocytes (2×105 cells/well) were incubated for 24 hr with the indicated concentrations of oenothein B or LPS, and alkaline phosphatase release was analyzed spectrophotometrically in the cell supernatant. Cell viability was also determined using a CellTiter-Glo Luminescent Cell Viability Assay Kit. For both panels, the data are presented as mean±S.D. of triplicate samples from one experiment that is representative of 3 independent experiments.

Pyrocatechol, gallic acid, pyrogallol, 3,4-dihydroxybenzoic acid, carilagin, and PGG were also evaluated for activity in the NF-κB alkaline phosphatase reporter assay. All of these compounds, including PGG, failed to induce NF-κB reporter activity when tested in the concentration range of 10–100 µM. Supplemental Figure S4 shows the response to these compounds at selected concentrations, as compared to that induced by 25 µM oenothein B.

NF-κB activation by was not due to endotoxin contamination in our samples, as analysis of oenothein B for endotoxin using a LAL assay showed that the isolated compound contained <0.625 ng/mg endotoxin, which is considered to be insignificant for various bioactive products (51,52). Since it is possible that oenothein B could inhibit a pathway in the LAL coagulation cascade, for example by binding to one of the protein factors, we also pretreated oenothein B by elution through a column of endotoxin-removing gel. We found that the pretreated oenothein B (oenothein B-ER) was just as active as untreated sample (Supplemental Figure S4), again confirming the absence of endotoxin contamination.

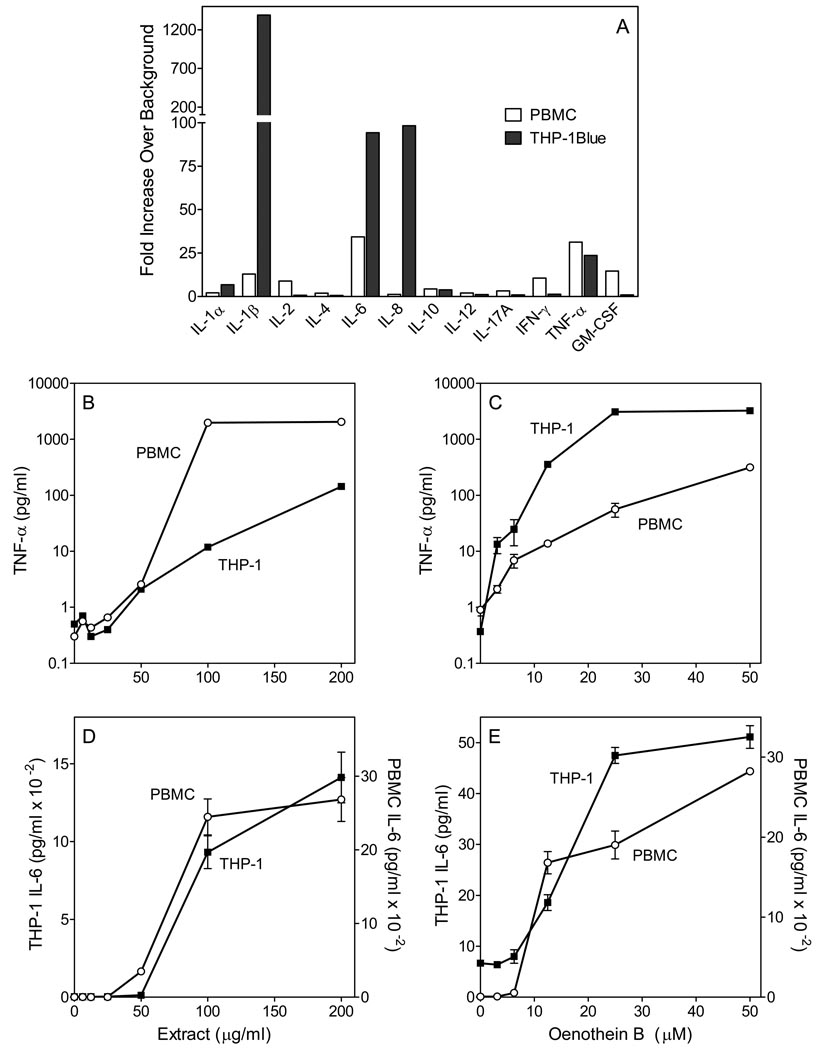

Effect of E. angustifolium extract and purified oenothein B on phagocyte cytokine production

Previous studies showed that oenothein B stimulated release of an interleukin 1β (IL-1β) from murine and human macrophages (28); however, the effect of this compound on other cytokines has not been evaluated. To address this issue, condition media from THP-1Blue monocytes and human PBMCs was analyzed using a cytokine ELISA semi-quantitative array. Among the 12 cytokines analyzed, five were consistently induced in PBMCs (>10-fold) by 10 µM oenothein B, as compared with control cells. These included interferon-γ [fold increase (FI)=11], IL-1β (FI=13), GM-CSF (FI=15), TNF-α (FI=31), and IL-6 (FI=34) (Figure 10A). IL-8 production was inconclusive because of high background production by PBMCs (data not shown), a problem which has also been documented previously (e.g., (53)). Human monocytic THP-1Blue cells, treated with 25 µM oenothein B produced high levels of TNF-α (FI=24), IL-6 (FI=94), and IL-8 (FI=98) (Figure 10A).

Figure 10.

Effect of E. angustifolium extract and oenothein B on cytokine production by human THP-1Blue monocytes and PBMCs. Panel A. THP-1Blue cells and PBMCs were incubated for 24 hr with 25 µM oenothein B, and production of cytokines in the supernatants was evaluated using a Multi-Analyte ELISArrayTM kit. Cytokine expression is shown as an optical density (A450–A570) ratio normalized to background. Panels B–E. THP-1Blue cells and PBMCs were incubated for 24 hr with the indicated concentrations E. angustifolium extract (B, D) or oenothein B (C, E). Cell-free supernatants were collected and secreted TNF-α (B, C) and IL-6 (D, E) were quantified by ELISA. For panels B–E, the data are presented as mean±S.D. of triplicate samples from one experiment that is representative of three independent experiments.

To quantify dose-dependent effects of E. angustifolium extract and oenothein B on cytokine production, levels of TNF-α and IL-6 were determined by ELISA of supernatants from treated cells. Untreated cells produced negligible amounts of TNF-α and IL-6, whereas incubation of THP-1Blue monocytes and PBMCs with crude extract (Figure 10 B,D) or purified oenothein B (Figure 10 C,E) enhanced TNF-α and IL-6 production in a dose-dependent manner. Note, however, that pretreatment of oenothein B with endotoxin-removing gel no effect on its activity, indicating that the induction of TNF-α and IL-6 production was not due to endotoxin contamination (data not shown).

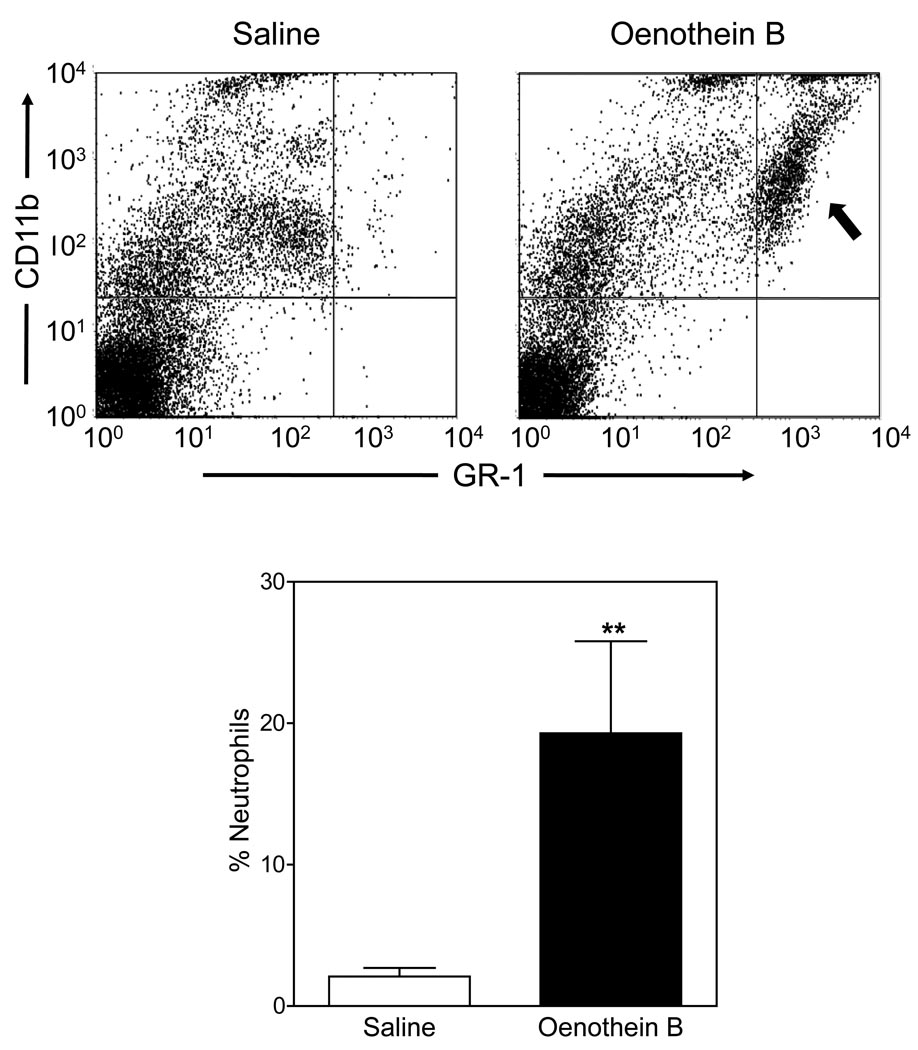

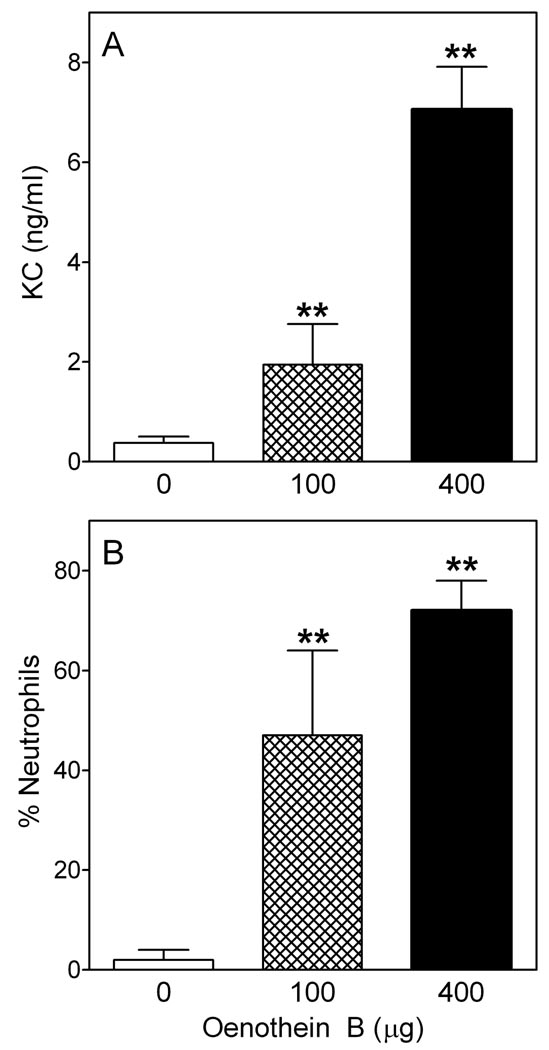

In vivo analysis of oenothein B

To evaluate the effect of oenothein B in vivo, mice were treated by intraperitoneal injection of oenothein B, and neutrophil recruitment to the peritoneum was evaluated. As shown in Figure 11, oenothein B significantly induced neutrophil recruitment (~10-fold increase over saline controls). Since the mice were analyzed 4 hr post-injection, neutrophils were the primary phagocyte recruited. As expected, little change in monocyte/macrophage levels was observed in this short period of time (data not shown). The primary neutrophil chemotactic agent at inflammatory sites is IL-8 (KC in mice). Thus, we evaluated KC levels in mice treated with oenothein B and found that oenothein B dose-dependently induced significant levels of serum KC, which correlated with the observed recruitment of neutrophils into the peritoneum (Figure 12). Thus, these studies verify our in vitro experiments and confirm that this oenothein B is active in vivo.

Figure 11.

Neutrophil recruitment to the peritoneum in response to oenothein B. BALB/c mice were injected intraperitoneally with oenothein B (100 µg) or control saline, as indicated. After 4 hr, peritoneal cells were collected and stained for flow cytometric analysis. Upper Panel. Representative examples of two-color dot plots comparing CD11b and GR-1 staining on CD45+ cells from saline- and oenothein B-treated mice. The quadrant containing the neutrophil population is indicated (arrow), which was used to determine the percentage of the overall CD45+ cell population in the peritoneum. Lower Panel. Pooled results from three mice in each test group, as analyzed in Panel A. The data are presented as mean±S.E.M. of three mice. Representative of two independent experiments. Statistically significant difference (**P<0.01) versus saline control is indicated.

Figure 12.

Oenothein B-induced recruitment of neutrophils in vivo is associated with induction of KC production. BALB/c mice were injected intraperitoneally with either 100 or 400 µg of oenothein B or control saline, as indicated. After 4 hr, serum was collected for KC analysis by ELISA (Panel A), and peritoneal cells were collected and stained for flow cytometric analysis of % neutrophils (RB6-8C5 bright, CD45+ cells) in the peritoneal washes, as described under Figure 12 (Panel B). The data are presented as mean±S.D. of four mice. Representative of two independent experiments. Statistically significant differences (**P<0.01) versus saline control are indicated.

Discussion

Extracts from E. angustifolium have been reported to be beneficial for treating a variety of medical problems, such as gastrointestinal, and prostate diseases, and to improve the healing of wounds (11). However, little is known regarding the effects of E. angustifolium on innate immune functions. Here, we demonstrate that E. angustifolium extracts can induce or enhance phagocyte functional responses and that the active principle in these extracts is oenothein B. Since oenothein B is a major component of Epilobium (24), we propose that the effects of oenothein B on innate immune function likely contribute to the therapeutic efficacy of Epilobium extracts.

Oenothein B was first isolated from Oenothera erythrosepala (Onagraceae) (54) and was subsequently found in Eucalyptus, Eugenia species, and Lythraceae species (31). Previous studies on oenothein B have shown that it exhibits significant antioxidant (26), antitumor (27,28,30,55), antibacterial (56), and antiviral (32) activities, although the mechanisms involved are not well defined. Most studies on oenothein B have focused on its antitumor activity, and it has been shown to inhibit poly-(ADP-ribose) glycohydrolase, 5α-reductase, and aromatase (24,57,58), and also to induce a neutral endopeptidase in prostate cancer cells (34). Miyamoto et al. (27) reported that oenothein B had potent antitumor activity upon intraperitoneal administration to mice before tumor inoculation and suggested that this may be due to enhancement of the host-immune system via macrophage activation. However, essentially nothing else has been reported on the effects of oenothein B on innate immunity. We show here that oenothein B activates phagocytic cells, including monocyte/macrophages and neutrophils, resulting in increased intracellular Ca2+, production of ROS and cytokines, and chemotactic activity. Additionally, we demonstrated that oenothein B induced IL-8 production and neutrophil recruitment to the peritoneum of treated mice. Given the critical role played by phagocytes in innate immunity against pathogens and their contribution to tumor cell destruction (reviewed in (59)), our data support the possibility that at least part of the observed therapeutic effects of oenothein B and Epilobium extracts in general are due to enhancement of innate immune responses.

In addition to enhancement of innate immune function, oenothein B also was found to scavenge ROS generated by activated phagocytes or by an enzymatic system, which confirms previous reports on the antioxidant activity of this compound determined using a radical scavenging assay (26,45). Thus, oenothein B is able to stimulate local innate immunity but may also protect tissues from excessive ROS production. While the antioxidant activity of polyphenols has been assumed to be the primary therapeutic property, recent studies indicate that many polyphenols directly impact cellular signaling events, which is in independent of their antioxidant activity (e.g., see (33)). Since antioxidant capacity is often diminished or even lost during absorption in vivo, the primary therapeutic properties of oenothein B and other polyphenols may indeed be due to direct modulation of cellular activity, such as the modulation of innate immune functions shown here.

The non-specific nature of immunomodulators makes them attractive because they can be used to treat a broad-spectrum of infections and are not susceptible to antibiotic resistance (60). In general, immunomodulators mimic the natural mechanisms used by pathogens to stimulate innate immunity and thus are potentially beneficial in preventing infection (60). Thus, the balance between therapeutic and pro-inflammatory properties is important to consider when evaluating immunomodulators, and the goal is to enhance or prime local host defense without inducing excessive or systemic inflammation. This balance is dependent on pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties of the compound and must be determined empirically. For example, CpG DNA, an immunomodulator with therapeutic promise, induces a range of phagocyte inflammatory responses via Toll-like receptor 9 (TLR9), which leads to beneficial Th1-type responses (60,61). Conversely, excessive activation of TLR9 can contribute to detrimental inflammatory states (e.g., (62)). Likewise, we suggest that therapeutic concentrations of oenothein B could prime or enhance innate immune cells without inducing adverse inflammatory responses, which is supported by our in vivo experiments. On the other hand, our in vitro data suggest that treatment with high concentrations of oenothein B could lead to excessive inflammation if sufficient local concentrations were achieved. Thus, further analyses are clearly needed to further evaluate the specific pharmacological properties of oenothein B in vivo.

Initiation of intracellular Ca2+ flux is one of the earliest events associated with phagocyte receptor activation and plays a central role in receptor-mediated intracellular signaling events (50). Furthermore, Ca2+ mobilization is required for ROS production in phagocytes, mainly through the activation of NADPH oxidase (e.g., (63)). We found that oenothein B induced a transient elevation of [Ca2+]i in neutrophils, indicating this compound is a phagocyte agonist; however, compounds structurally related to the building blocks of oenothein B (pyrocatechol, gallic acid, pyrogallol, and 3,4-dihydroxybenzoic acid) had did not induce Ca2+ mobilization or other phagocyte responses. On the other hand, one of the two tannins tested (PGG) did induce a Ca2+ and ROS production in neutrophils. Although various tannins and other compounds with galloyl groups, including galloylpunicalagin, woodfordin, and cotton-derived tannins, have been reported previously to activate Ca2+ flux in phagocytes (64–67), this is the first report evaluating the effects of oenothein B on phagocyte Ca2+ mobilization, ROS production, and chemotaxis.

A number of ellagitannins and other tannins have been shown to activate phagocyte functions, including cytokine production and phagocytosis. For example, the ellagitannin geraniinm, which is isolated from Geranium funbergii, has been reported to induce macrophage phagocytosis (68). Likewise, cuphiin D1, tellimagrandins I and II, rugosin A, casuarictin, coriariin, agrimoniin, and PGG have been shown to induce IL-1β and/or TNF-α production by human peripheral mononuclear cells and macrophages in vitro (28,69–71). We also found that oenothein B induced IL-1β and TNF-α production by human monocyte/macrophages, but also provide the novel finding that interferon-γ, GM-CSF, IL-6, and IL-8 are also induced in human monocyte/macrophages. Additionally, we found that intraperitoneal administration of oenothein B induced a significant level of KC in treated mice and that KC induction directly correlated with neutrophil influx into the peritoneum, demonstrating that cytokine induction defined in this report is relevant in vivo. Thus, the ability of oenothein B to induce these cytokines may also play an important role in the microbicidal, viricidal, and antitumor effects of this compound. For example, IL-1β is capable of upregulating the activity of tumoricidal natural killer cells and inducing antitumor reactivity in the regional lymph nodes and spleen (reviewed in (72)). Among the proinflammatory cytokines, IL-6 is one of the most important mediators of fever and the acute-phase response (73). TNF-α has direct in vitro and in vivo cytostatic and cytocidal effects and, together with IL-6, is also considered as a major immune and inflammatory mediator (73). One of the most prominent characteristics of TNF-α is its ability to cause apoptosis of tumor cells, resulting in tumor necrosis (74). TNF-α also plays a pivotal role in host defense and can act on macrophages in an autocrine manner to enhance various functional responses and induce the expression of a number of other immunoregulatory and inflammatory mediators (75).

NF-κB is activated in response to stimulation by inflammatory agents, including LPS, and activation of NF-κB is an essential step in inducing proinflammatory cytokines, chemokines, inflammatory enzymes, adhesion molecules, receptors, and inhibitors of apoptosis (reviewed in (76)). Treatment of phagocytes with oenothein B resulted in the activation of NF-κB. In addition, treatment of cells with both oenothein B and LPS resulted in an even greater NF-κB response, suggesting a synergistic effect. Therefore, the ability to activate phagocyte NF-κB signaling provides further evidence that oenothein B possesses immunomodulatory properties. The synergistic effect of oenothein B and LPS is consistent with studies of Feldman (25), who suggested that dimeric tannins could mimic the lipid A moiety of LPS. In contrast with our data, Chen et al. (77) reported that oenothein B modestly inhibited LPS-induced NF-κB activity in Bcl-2-overexpressing murine RAW264.7 macrophages. Although the reasons for this difference are not clear, it is possible that this may be due to differences in the cell lines used. Alternatively, NF-κB activation by oenothein B could be indirect and mediated by cytokines induced during the assay, as NF-κB reporter activity only began to increase at after 12 hr incubation with oenothein B and was not significant until 18 hr. Thus, further studies are now in progress to evaluate this issue and determine which receptor(s) and intercellular pathway(s) are in NF-κB activation and expression of various cytokines induced by oenothein B.

Oenothein B and a related tannin, PGG, induced ROS production and Ca2+ mobilization in phagocytes, whereas, the monomeric polyphenols pyrocatechol, gallic acid, pyrogallol, and 3,4-dihydroxybenzoic acid were inactive. On the other hand, only oenothein B, which has a dimeric macrocyclic structure (see Supplemental Figure S1), induced NF-κB activity. In addition, HL-60 cells responded to oenothein B only after differentiation. These findings suggest oenothein B may be activating phagocytes through a specific receptor or cellular target, which is yet to be identified. Tannins bind to a wide range of targets, including phospholipids, carbohydrates, and proteins (78–80). For example, Teng et al. (81) reported that the ellagitannin rugosin E activated platelet Ca2+ flux by acting as an ADP receptor agonist. Thus, it is possible that oenothein B could be interacting with a number of extracellular membrane targets, such as receptors or lipid rafts involved in regulating phagocyte activation. Nevertheless, further work is necessary to identify the target of oenothein B.

As reported previously, oenothein B is a major component of Epilobium extracts and can be present at concentrations up to 14% (~9 µM in 100 µg/ml extract), although the level varies between species and is reported to be 4.5% in E. angustifolium (24). However, it has not yet been determined whether these concentrations vary in different regions of the world or between different lots of plants. We found that E. angustifolium extracts induced intracellular Ca2+ flux, ROS production, chemotaxis, and cytokine production in qualitatively similar patterns as purified oenothein B, supporting the conclusion that oenothein B is indeed the active component in these extracts. However, it is also apparent that the extracts were more potent than oenothein B if we use the estimated concentration of 4.5% in our extracts (~3 µM oenothein B in 100 µg/ml extract). The reasons for this difference are not clear; however, this observation is supported by studies from Kiss et al. (34) who showed that E. angustifolium extract was ~10-fold more potent that pure oenothein B in inducing neutral endopeptidase activity in prostate cancer cells. One possibility is that other constituents in the extract may help to increase oenothein B bioavailability or stability. For example, the solubility of the active component in a crude extract can often be reduced when the component is purified. It is also possible that some reactive groups are altered during purification, thus affecting activity. These issues are currently under investigation.

Overall, our studies demonstrate that oenothein B activates a number of phagocyte functions, including Ca2+, NADPH oxidase activity, chemotaxis, and cytokine production. In addition, we established that oenothein B can modulate phagocyte activity in vivo. The ability of this compound to modulate innate immune functions suggests that at least part of the reported effects of Epilobium extracts and purified oenothein B on wound healing and inhibition of tumor growth is through modulation of macrophage function. Overall, these studies suggest that oenothein B may serve as a promising lead for further therapeutic development.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Robyn Klein (Department of Plant Sciences and Plant Pathology, Montana State University, Bozeman, MT) for plant identification. We would also thank Drs. Scott Busse and Philip Clark (Department of Chemistry, Montana State University, Bozeman, MT) for help in running NMR and mass spectroscopy samples.

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by NIH grants P20 RR-020185, P20 RR-016455, and P01 AT0004986-01; NIH contract HHSN266200400009C; an equipment grant from the M.J. Murdock Charitable Trust; and the Montana State University Agricultural Experimental Station.

References

- 1.Ballow M, Nelson R. Immunopharmacology: immunomodulation and immunotherapy. JAMA. 1997;278:2008–2017. doi: 10.1001/jama.278.22.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Villinger F. Cytokines as clinical adjuvants: how far are we? Expert. Rev. Vaccines. 2003;2:317–326. doi: 10.1586/14760584.2.2.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wasser SP. Medicinal mushrooms as a source of antitumor and immunomodulating polysaccharides. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2002;60:258–274. doi: 10.1007/s00253-002-1076-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paulsen BS. Plant polysaccharides with immunostimulatory activities. Curr. Organic Chem. 2001;5:939–950. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kayser O, Masihi KN, Kiderlen AF. Natural products and synthetic compounds as immunomodulators. Expert. Rev. Anti. Infect. Ther. 2003;1:319–335. doi: 10.1586/14787210.1.2.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schepetkin IA, Quinn MT. Botanical polysaccharides: macrophage immunomodulation and therapeutic potential. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2006;6:317–333. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gabius HJ. Probing the cons and pros of lectin-induced immunomodulation: case studies for the mistletoe Lectin and galectin-1. Biochimie. 2001;83:659–666. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(01)01311-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Byrd-Leifer CA, Block EF, Takeda K, Akira S, Ding A. The role of MyD88 and TLR4 in the LPS-mimetic activity of Taxol. Eur. J. Immunol. 2001;31:2448–2457. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200108)31:8<2448::aid-immu2448>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fujinaga Y, Inoue K, Nomura T, Sasaki J, Marvaud JC, Popoff MR, Kozaki S, Oguma K. Identification and characterization of functional subunits of Clostridium botulinum type A progenitor toxin involved in binding to intestinal microvilli and erythrocytes. FEBS Lett. 2000;467:179–183. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01147-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gertsch J, Schoop R, Kuenzle U, Suter A. Echinacea alkylamides modulate TNF-α gene expression via cannabinoid receptor CB2 and multiple signal transduction pathways. FEBS Lett. 2004;577:563–569. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.10.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tyler VE. Some recent advances in herbal medicines. Pharmacy Int. 1986;7:203–207. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hiermann A, Juan H, Sametz W. Influence of Epilobium extracts on prostaglandin biosynthesis and carrageenin induced oedema of the rat paw. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1986;17:161–169. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(86)90055-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hiermann A, Bucar F. Studies of Epilobium angustifolium extracts on growth of accessory sexual organs in rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1997;55:179–183. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(96)01498-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vitalone A, Guizzetti M, Costa LG, Tita B. Extracts of various species of Epilobium inhibit proliferation of human prostate cells. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2003;55:683–690. doi: 10.1211/002235703765344603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vitalone A, McColl J, Thome D, Costa LG, Tita B. Characterization of the effect Epilobium extracts on human cell proliferation. Pharmacology. 2003;69:79–87. doi: 10.1159/000072360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jones NP, Arnason JT, Abou-Zaid M, Akpagana K, Sanchez-Vindas P, Smith ML. Antifungal activity of extracts from medicinal plants used by First Nations Peoples of eastern Canada. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2000;73:191–198. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(00)00306-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Webster D, Taschereau P, Belland RJ, Sand C, Rennie RP. Antifungal activity of medicinal plant extracts; preliminary screening studies. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2008;115:140–146. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2007.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Battinelli L, Tita B, Evandri MG, Mazzanti G. Antimicrobial activity of Epilobium spp. extracts. Farmaco. 2001;56:345–348. doi: 10.1016/s0014-827x(01)01047-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rauha JP, Remes S, Heinonen M, Hopia A, Kahkonen M, Kujala T, Pihlaja H, Vuorela H, Vuorela P. Antimicrobial effects of Finnish plant extracts containing flavonoids and other phenolic compounds. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2000;56:3–12. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1605(00)00218-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pourmorad F, Ebrahimzadeh MA, Mahmoudi M, Yasini S. Antinociceptive activity of methanolic extract of Epilobium hirsutum. Pak. Biol. Sci. 2007;10:2764–2767. doi: 10.3923/pjbs.2007.2764.2767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tita B, Abdel-Haq H, Vitalone A, Mazzanti G, Saso L. Analgesic properties of Epilobium angustifolium, evaluated by the hot plate test and the writhing test. Farmaco. 2001;56:341–343. doi: 10.1016/s0014-827x(01)01046-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shikov AN, Poltanov EA, Dorman HJ, Makarov VG, Tikhonov VP, Hiltunen R. Chemical composition and in vitro antioxidant evaluation of commercial water-soluble willow herb (Epilobium angustifolium L.) extracts. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006;54:3617–3624. doi: 10.1021/jf052606i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stajner D, Popovic BM, Boza P. Evaluation of willow herb's (Epilobium angustifolium L.) antioxidant and radical scavenging capacities. Phytother. Res. 2007;21:1242–1245. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ducrey B, Marston A, Gohring S, Hartmann RW, Hostettmann K. Inhibition of 5 α-reductase and aromatase by the ellagitannins oenothein A and oenothein B from Epilobium species. Planta Med. 1997;63:111–114. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-957624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feldman KS. Recent progress in ellagitannin chemistry. Phytochemistry. 2005;66:1984–2000. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2004.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yoshimura M, Amakura Y, Tokuhara M, Yoshida T. Polyphenolic compounds isolated from the leaves of Myrtus communis. Nat. Med. (Tokyo) 2008;62:366–368. doi: 10.1007/s11418-008-0251-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miyamoto K, Nomura M, Sasakura M, Matsui E, Koshiura R, Murayama T, Furukawa T, Hatano T, Yoshida T, Okuda T. Antitumor activity of oenothein B, a unique macrocyclic ellagitannin. Jpn. J. Cancer Res. 1993;84:99–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1993.tb02790.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miyamoto K, Murayama T, Nomura M, Hatano T, Yoshida T, Furukawa T, Koshiura R, Okuda T. Antitumor activity and interleukin-1 induction by tannins. Anticancer Res. 1993;13:37–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang LL, Wang CC, Yen KY, Yoshida T, Hatano T, Okuda T. Antitumor activities of ellagitannins on tumor cell lines. Basic Life Sci. 1999;66:615–628. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-4139-4_34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sakagami H, Jiang Y, Kusama K, Atsumi T, Ueha T, Toguchi M, Iwakura I, Satoh K, Ito H, Hatano T, Yoshida T. Cytotoxic activity of hydrolyzable tannins against human oral tumor cell lines--a possible mechanism. Phytomedicine. 2000;7:39–47. doi: 10.1016/S0944-7113(00)80020-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yoshida T, Hatano T, Ito H. Chemistry and function of vegetable polyphenols with high molecular weights. Biofactors. 2000;13:121–125. doi: 10.1002/biof.5520130120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fukuchi K, Sakagami H, Okuda T, Hatano T, Tanuma S, Kitajima K, Inoue Y, Inoue S, Ichikawa S, Nonoyama M. Inhibition of herpes simplex virus infection by tannins and related compounds. Antiviral Res. 1989;11:285–297. doi: 10.1016/0166-3542(89)90038-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Virgili F, Marino M. Regulation of cellular signals from nutritional molecules: a specific role for phytochemicals, beyond antioxidant activity. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2008;45:1205–1216. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kiss A, Kowalski J, Melzig MF. Induction of neutral endopeptidase activity in PC-3 cells by an aqueous extract of Epilobium angustifolium L. and oenothein B. Phytomedicine. 2006;13:284–289. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2004.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jasek E, Mirecka J, Litwin JA. Effect of differentiating agents (all-trans retinoic acid and phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate) on drug sensitivity of HL60 and NB4 cells in vitro. Folia Histochem. Cytobiol. 2008;46:323–330. doi: 10.2478/v10042-008-0080-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Siemsen DW, Schepetkin IA, Kirpotina LN, Lei B, Quinn MT. Neutrophil isolation from nonhuman species. Methods Mol. Biol. 2007;412:21–34. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-467-4_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li W, Chung SC. Flow cytometric evaluation of leukocyte function in rat whole blood. In Vitro Cell Dev. Biol. Anim. 2003;39:413–419. doi: 10.1290/1543-706X(2003)039<0413:FCEOLF>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schepetkin IA, Khlebnikov AI, Quinn MT. N-Benzoylpyrazoles are novel small-molecule inhibitors of human neutrophil elastase. J. Med. Chem. 2007;50:4928–4938. doi: 10.1021/jm070600+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schepetkin IA, Kirpotina LN, Tian J, Khlebnikov AI, Ye RD, Quinn MT. Identification of novel formyl peptide receptor-like 1 agonists that induce macrophage tumor necrosis factor α production. Mol. Pharm. 2008;74:392–402. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.046946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Daiber A, August M, Baldus S, Wendt M, Oelze M, Sydow K, Kleschyov AL, Munzel T. Measurement of NAD(P)H oxidase-derived superoxide with the luminol analogue L-012. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2004;36:101–111. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2003.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bindoli A, Valente M, Cavallini L. Inhibitory action of quercetin on xanthine oxidase and xanthine dehydrogenase activity. Pharmacol. Res. Commun. 1985;17:831–839. doi: 10.1016/0031-6989(85)90041-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schepetkin IA, Kirpotina LN, Khlebnikov AI, Quinn MT. High-throughput screening for small-molecule activators of neutrophils: Identification of novel N-formyl peptide receptor agonists. Mol. Pharm. 2007;71:1061–1074. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.033100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yoshida T, Chou T, Shingu T, Okuda T. Oenothein-D, oenothein-F and oenothein-G, hydrolyzable tannin dimers from Oenothera laciniata. Phytochemistry. 1995;40:555–561. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Santos SC, Waterman PG. Polyphenols from Eucalyptus consideniana and Eucalyptus viminalis. Fitoterapia. 2001;72:95–97. doi: 10.1016/s0367-326x(00)00252-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hevesi Tóth B, Blazics B, Kéry A. Polyphenol composition and antioxidant capacity of Epilobium species. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2009;49:26–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2008.09.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reed JD, Krueger CG, Vestling MM. MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry of oligomeric food polyphenols. Phytochemistry. 2005;66:2248–2263. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2005.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hager TJ, Howard LR, Liyanage R, Lay JO, Prior RL. Ellagitannin composition of blackberry as determined by HPLC-ESI-MS and MALDI-TOF-MS. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008;56:661–669. doi: 10.1021/jf071990b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hiermann A, Reidlinger M, Juan H, Sametz W. Isolation of the antiphlogistic principle from Epilobium angustifolium. Planta Med. 1991;57:357–360. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-960117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bazylko A, Kiss AK, Kowalski J. High-performance thin-layer chromatography method for quantitative determination of oenothein B and quercetin glucuronide in aqueous extract of Epilobium angustifolium herba. J. Chromatogr. A. 2007;1173:146–150. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2007.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lew PD. Receptors and intracellular signaling in human neutrophils. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1990;141:S127–S131. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/141.3_Pt_2.S127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jahr TG, Ryan L, Sundan A, Lichenstein HS, Skjak-Braek G, Espevik T. Induction of tumor necrosis factor production from monocytes stimulated with mannuronic acid polymers and involvement of lipopolysaccharide-binding protein, CD14, and bactericidal/permeability-increasing factor. Infect. Immun. 1997;65:89–94. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.1.89-94.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Catchpole B, Hamblin AS, Staines NA. Autologous mixed lymphocyte responses in experimentally-induced arthritis of the Lewis rat. Autoimmunity. 2002;35:111–117. doi: 10.1080/08916930290016619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kikkert R, de Groot ER, Aarden LA. Cytokine induction by pyrogens: comparison of whole blood, mononuclear cells, and TLR-transfectants. J. Immunol. Methods. 2008;336:45–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2008.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hatano T, Yasuhara T, Matsuda M, Yazaki K, Yoshida T, Okuda T. Oenothein B, a dimeric, hydrolyzable tannin with macrocyclic structure, and accompanying tannins from Oenothera erythrosepala. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1990;1:2735–2743. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang CC, Chen LG, Yang LL. Antitumor activity of four macrocyclic ellagitannins from Cuphea hyssopifolia. Cancer Lett. 1999;140:195–200. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(99)00071-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yoshida T, Hatano T, Ito H. Chemistry and function of vegetable polyphenols with high molecular weights. Biofactors. 2000;13:121–125. doi: 10.1002/biof.5520130120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Aoki K, Maruta H, Uchiumi F, Hatano T, Yoshida T, Tanuma S. A macrocircular ellagitannin, oenothein B, suppresses mouse mammary tumor gene expression via inhibition of poly(ADP-ribose) glycohydrolase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1995;210:329–337. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lesuisse D, Berjonneau J, Ciot C, Devaux P, Doucet B, Gourvest JF, Khemis B, Lang C, Legrand R, Lowinski M, Maquin P, Parent A, Schoot B, Teutsch G. Determination of oenothein B as the active 5-α-reductase-inhibiting principle of the folk medicine Epilobium parviflorum. J. Nat. Prod. 1996;59:490–492. doi: 10.1021/np960231c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hume DA. The mononuclear phagocyte system. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2006;18:49–53. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2005.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Finlay BB, Hancock REW. Can innate immunity be enhanced to treat microbial infections? Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2004;2:497–504. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Barchet W, Wimmenauer V, Schlee M, Hartmann G. Accessing the therapeutic potential of immunostimulatory nucleic acids. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2008;20:389–395. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2008.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Franklin BS, Parroche P, Ataide MA, Lauw F, Ropert C, de Oliveira RB, Pereira D, Tada MS, Nogueira P, da Silva LH, Bjorkbacka H, Golenbock DT, Gazzinelli RT. Malaria primes the innate immune response due to interferon-gamma induced enhancement of toll-like receptor expression and function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009;106:5789–5794. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809742106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sakaguchi N, Inoue M, Ogihara Y. Reactive oxygen species and intracellular Ca2+, common signals for apoptosis induced by gallic acid. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1998;55:1973–1981. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(98)00041-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lauque D, Prevost MC, Carles P, Chap H. Signal transducing mechanisms in human platelets stimulated by cotton bract tannin. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 1991;4:65–71. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb/4.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bates PJ, Ralston NV, Vuk-Pavlovic Z, Rohrbach MS. Calcium influx is required for tannin-mediated arachidonic acid release from alveolar macrophages. Am. J. Physiol. 1995;268:L33–L40. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1995.268.1.L33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Liu MJ, Wang Z, Li HX, Wu RC, Liu YZ, Wu QY. Mitochondrial dysfunction as an early event in the process of apoptosis induced by woodfordin I in human leukemia K562 cells. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2004;194:141–155. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2003.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chen LG, Liu YC, Hsieh CW, Liao BC, Wung BS. Tannin 1-α-O-galloylpunicalagin induces the calcium-dependent activation of endothelial nitric-oxide synthase via the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathway in endothelial cells. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2008;52:1162–1171. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200700335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ushio Y, Fang T, Okuda T, Abe H. Modificational changes in function and morphology of cultured macrophages by geraniin. Jpn. J. Pharmacol. 1991;57:187–196. doi: 10.1254/jjp.57.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Murayama T, Kishi N, Koshiura R, Takagi K, Furukawa T, Miyamoto K. Agrimoniin, an antitumor tannin of Agrimonia pilosa Ledeb., induces interleukin-1. Anticancer Res. 1992;12:1471–1474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Feldman KS, Sahasrabudhe K, Smith RS, Scheuchenzuber WJ. Immunostimulation by plant polyphenols: a relationship between tumor necrosis factor-α production and tannin structure. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1999;9:985–990. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(99)00110-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wang CC, Chen LG, Yang LL. In vitro immunomodulatory effects of cuphiin D1 on human mononuclear cells. Anticancer Res. 2002;22:4233–4236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Apte RN, Voronov E. Interleukin-1--a major pleiotropic cytokine in tumor-host interactions. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2002;12:277–290. doi: 10.1016/s1044-579x(02)00014-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gabay C. Interleukin-6 and chronic inflammation. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2006;8(Suppl 2):S3. doi: 10.1186/ar1917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lejeune FJ, Lienard D, Matter M, Ruegg C. Efficiency of recombinant human TNF in human cancer therapy. Cancer Immun. 2006;6:6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Baugh JA, Bucala R. Mechanisms for modulating TNFα in immune and inflammatory disease. Curr. Opin. Drug Discov. Devel. 2001;4:635–650. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Brasier AR. The NF-κB regulatory network. Cardiovasc. Toxicol. 2006;6:111–130. doi: 10.1385/ct:6:2:111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chen Y, Yang L, Lee TJ. Oroxylin A inhibition of lipopolysaccharide-induced iNOS and COX-2 gene expression via suppression of nuclear factor-κB activation. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2000;59:1445–1457. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(00)00255-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Takechi M, Tanaka Y. Binding of 1,2,3,4,6-pentagalloylglucose to proteins, lipids, nucleic acids and sugars. Phytochemistry. 1987;26:95–97. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kusuda M, Hatano T, Yoshida T. Water-soluble complexes formed by natural polyphenols and bovine serum albumin: evidence from gel electrophoresis. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2006;70:152–160. doi: 10.1271/bbb.70.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]