Abstract

Background

Several previous MRI studies have reported reductions in corpus callosum (CC) total area and CC regions in individuals with autism. However, studies have differed concerning the presence, magnitude, and/or region contributing to CC reductions. The primary aim of the present study was to determine the significance and magnitude of reduction in CC total and regional area measures in patients with autism.

Method

PubMed and PsycInfo databases were searched to identify MRI studies examining corpus callosum area in autism. Ten studies contributed data from 253 patients with autism (Mean age=14.58, SD=6.00) and 250 healthy controls (M age=14.47, sd=5.31). Of these ten studies, eight reported area measurements for corpus callosum regions (anterior, mid/body, and posterior), with six studies reported area for Witelson subdivisions. Meta-analytic procedures were used to quantify autism versus healthy control differences in total and region CC area measurements. Demographics and study characteristics were examined as moderators of total CC area.

Results

Total CC area was reduced in autism and the magnitude of the reduction was medium (Weighted Mean d=.48, 95% CI=.30-.66). All regions showed reductions in size with the magnitude of the effect decreasing caudally (anterior d=.49, mid/body d=.43, posterior d=.37). Witelson sub-division 3 (rostral body) showed the largest effect, indicating greatest reduction in the region containing pre-/supplementary motor neurons.

Conclusions

CC reductions are present in autism and support the aberrant connectivity hypothesis. Future diffusion tensor imaging studies examining specific fiber tracts connecting the hemispheres are needed to identify the cortical regions most affected by CC reductions.

Keywords: autism, corpus callosum, meta-analysis, magnetic resonance imaging

Autism is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by deficits in social interaction, communication, and stereotyped or repetitive behaviors (1). There is strong evidence of neural system abnormalities in autism, but the extent and neurodevelopmental timing of these abnormalities remains uncertain (2). Findings from post-mortem, head circumference, and brain imaging studies have suggested increases in brain volume in autism (3-9), with the largest increase being for gray matter and outer radiate white matter (2). These observations may be related to genetic influences, as seen in Fragile X (10) and PTEN heterozygous mutations (11, 12). Recent studies of biological pathways implicated in these changes might support the connection between cortical overgrowth and autism symptoms (13). However, these findings should be reconciled with the hypothesis of abnormal connectivity in autism and the evidence of decreased, and not increased, corpus callosum size.

Aberrant connectivity theory posits dysfunction in the long-distance connections between cortical brain regions in autism, resulting in impairments in complex cognitive processes such as executive functions, social cognition, and language (14). Structural white matter abnormalities (15), recent findings from studies using functional imaging (16-20) , and post-mortem neuropathologic investigations (3) support the theory of aberrant connectivity in autism (17, 20, 21). However, examination of structural imaging studies indicates that the magnitude and direction of white matter findings varies by the region examined and methodological differences across studies. Two studies have found increased volume of outer radiate white matter (15, 22), whereas findings for inner (deep) white matter compartments and long fiber tracts have generally indicated decreased area (17, 23-28), volume (29), density (30, 31), and integrity (29). Negative studies have also been reported, with no significant alterations in CC size in autism (32-34). The present study aims to bring clarity to previous inconsistencies by quantitatively summarizing results from studies examining area measurements of the corpus callosum.

The corpus callosum (CC) is the main fiber tract connecting the hemispheres and is topographically organized (35). Anterior CC regions represent fibers from pre-frontal cortices; mid/body regions are composed of fibers from pre-motor, motor, parietal, and superior temporal cortices; and the posterior region represents fibers from inferior temporal and occipital cortices (25). Given these extensive connections, study of the CC represents an important window into long-fiber, white matter connection abnormalities in autism. The majority of previous studies (7 of 10) have suggested significantly reduced total mid-sagittal area of the CC (17, 23-28). However, the magnitude of total CC area reductions and the regions contributing to these reductions have varied significantly across studies.

The first aim of the present study was to determine the magnitude and significance of total CC area reductions in individuals with autism relative to healthy participants. It was hypothesized that total CC area will be significantly smaller in autism and that the magnitude of this effect will be non-trivial, falling in the medium to large range (Cohen’s d=.50-.80). The second aim was to determine the magnitude and significance of CC region differences. This was done in two ways: using broader regions (anterior, mid/body, and posterior) and Witelson (35) subdivisions. Based upon previous findings of abnormal connectivity in numerous cortical regions in autism (2), it was hypothesized that all regions would show significant reductions in area. However, given the prominence of pre-frontal structures in brain connectivity , the later development and myelinization of these regions (36), and the substantial executive functioning deficits in autism (37, 38), anterior CC areas were hypothesized to show larger reductions than other regions.

An additional and final aim of the present study was to examine moderators of total CC area reductions in autism. To avoid non-replicable, post-hoc findings, a priori hypotheses were generated for potential moderators and analyses were restricted to total CC area. The relationship between age and neurobiological abnormalities is particularly intriguing given recent reviews strongly implicating abnormal neurobiological trajectories in autism (2, 39). Previous data have found reductions of white matter in autism with increasing age (5). Therefore, it was hypothesized that reductions in CC area relative to healthy controls would be larger with increasing average age of study participants. Following previous findings of increased total brain volume in autism, studies correcting for total brain or intracranial volume were anticipated to show larger CC area reductions. One study found a relationship between lower CC volume and lower intellectual level in autism (29), therefore, it was hypothesized that lower functional level of autism participants would be correlated with larger CC area reductions. Finally, it was expected that studies using more sensitive imaging techniques, higher magnet strength, and more detailed reporting of methodology would produce larger effects.

Method

Search Strategy and Exclusion Criteria

PubMed/Medline and PsycInfo were searched from January 1970 to June 2008 using the terms “autism or PDD or pervasive developmental disorder” and “corpus callosum.” A specific search for Asperger’s disorder was also done but no published studies were identified. Additional studies were identified by reviewing the references of each article found. Studies were included if they reported measurement for the total corpus callosum area in patients with autism and healthy controls. A total of 20 potential studies were identified. Ten studies were excluded for the following reasons: if effect sizes could not be computed (k=2), if there was clear overlap with a more detailed report (k=1), or if they reported volume or density measurements rather than area (k=7).

Study Coding

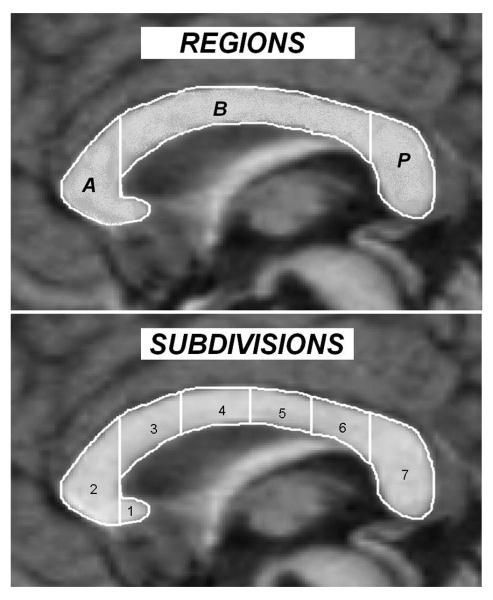

For each study, demographic and clinical variables were coded as follows: study publication date, sample size, average age, % male, IQ scores (if available), magnet strength, and means and SDs of CC total and region areas. If CC total or region means and SDs were not reported, inferential statistics were converted to an effect size (Cohen’s d; 40). If total CC area was not reported, but all CC regions were reported, values were averaged across regions to generate an estimate for total CC area. When more than one comparison group was available, healthy controls were chosen. When more than one set of values were presented for patients with autism (for example, autistic disorder and PDD NOS or autism spectrum), the values for patients with strictly defined autism were chosen. If both total brain volume corrected and uncorrected values were reported, corrected values were used. When covariates were used to adjust descriptive statistics, adjusted values were used. If studies presented a modified Witelson method, effect sizes were included if the regions reported closely mapped onto Witelson subdivisions. Figure 1 presents regions and Witelson sub-divisions. Region A, the anterior CC, represents the combination of Witelson subdivisions 1 and 2. Region B, CC body, represents Witelson subdivisions 3-6. Region P, posterior CC, is Witelson subdivision 7.

Figure 1.

Corpus callosum regions and Witelson subdivisions.

Note. A=Anterior, B=Body, P=Posterior; 1=rostrum, 2=genu, 3=rostral body, 4=anterior midbody, 5=posterior midbody, 6=isthmus, 7=splenium.

To determine the quality of study method and results reporting the following variables were coded (0 if not present/no, 0.5 partially present, 1 completely present/yes): the study was prospective; DSM diagnostic criteria were used; a gold standard diagnostic interview or observation scale was used to make the diagnosis (41, 42); demographics were reported; controls were healthy; controls were screened for neuropsychiatric illness; age, gender, IQ, and total brain or intracranial volume were matched or statistically controlled; image tracing blinded; inter-rater reliability reported; MRI slice thickness</=3mm; imaging method clearly described; and descriptive and/or inferential statistics reported for regions. Summing these variables yields a scale (Method Index) that evaluates methodology and results reporting - rather than study quality, as quality can only be inferred from reporting. The Method Index has a possible range from 0 to 15 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics and Selected Study Characteristics

| Study | Year | Autism n |

Control n |

Autism % Male |

Control % Male |

Autism Age M (SD) |

Control Age M (SD) |

Functional Levela |

Magnetic Field |

Region Method |

ES Corrected for Brain Sizeb |

Method Indexc |

Study ES (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gaffney (34) | 1987 | 13 | 35 | 77 | 60 | 11.30 (4.70) | 12.00 (5.20) | Mixed | 0.5T | no regions | no | 6.5 | .27 (−.37-.90) |

| Egaas (27) | 1995 | 51 | 51 | 88.2 | 88.2 | 15.50 (10.00) |

15.50 (9.90) | Mixed | 1.5 T | broad regions |

no | 9.5 | .33 (−.07-.72) |

| Piven (24) | 1997 | 35 | 36 | 74.3 | 55.6 | 18.00 (4.50) | 20.20 (3.80) | Mixed | 1.5T | broad regions |

yes | 14 | .31 (−.16-.77) |

| Manes (26) | 1999 | 27 | 17 | 81 | 65 | 14.30 (6.80) | 11.80 (5.00) | Low | 1.5T | Witelson | yes | 9 | .87 (.22-1.49) |

| Elia (33) | 2000 | 22 | 11 | 100 | 100 | 10.92 (4.02) | 10.86 (2.85) | Low | 0.5T | no regions | no | 7.5 | .16 (−.57-.88) |

| Hardan (25) | 2000 | 22 | 22 | 100 | 100 | 22.40 (10.10) |

22.40 (10.00) |

High | 1.5T | Witelson | yes | 14 | .64 (.02-1.23) |

| Rice (32) | 2005 | 12 | 8 | 100 | 100 | 12.42 (4.32) | 12.50 (3.46) | High | 1.5T | modified Witelson |

yes | 13 | .44 (−.48-1.33) |

| Boger- Meddido (28) |

2006 | 29 | 26 | 89.7 | 69 | 3.90 (.32) | 3.90 (.53) | Mixed | 1.5T | Witelson | no | 12.5 | .53 (−.02-1.06) |

| Vidal (23) | 2006 | 24 | 26 | 100 | 100 | 10.00 (3.30) | 11.00 (2.50) | High | 3.0T | modified Witelson |

yes | 14 | .73 (.15-1.29) |

| Just (17) | 2007 | 18 | 18 | 94.4 | 83.3 | 27.10 (11.90) |

24.50 (9.90) | High | 1.5T | Witelson | yes | 14 | .69 (.01-1.35) |

Note.

refers to the functional level of participants (low=study text indicated low functioning participants or majority of IQs <70, high=study text indicated all participants were high functioning, IQ>70, mixed=a combination of low and high functioning participants included in the study).

refers to whether the effect size (ES) value was corrected for total brain/intracranial volume or uncorrected. In some cases, total brain volume or intracranial volume corrections were reported but the effect size could only be computed from the uncorrected M’s and sd’s.

Method index ranges from 0-15 with higher numbers indicating better study reporting. 95% CI=95% confidence interval of the Cohen’s d effect size, unadjusted for covariates or matched pairs.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using both fixed and random effects models. Random effects models indicated little change in weighted mean effect sizes and negligible widening of confidence intervals relative to fixed effects models. The similarity of these approaches indicates that study level sampling error was negligible. Therefore, only results of the fixed effects analyses are reported as recommended by Lipsey and Wilson (43). Study effect sizes (Cohen’s d) were pooled using inverse variance weighting methods (43). Pooled effect sizes, 95% confidence intervals, the z-test examining the significance of the pooled effect size, and the chi-square goodness of fit test of heterogeneity of effect sizes (Q) were calculated for each comparison of interest: total CC area; anterior, mid/body, and posterior regions; and Witelson subdivisions (labeled W1-W7; Table 2). Q tends to be underpowered for small meta-analytic sample sizes, leading to failure to reject the null hypothesis of homogeneity of effect sizes when substantial heterogeneity is actually present. For this reason, we examined the influence of study characteristics on effect sizes using meta-regression (44). These analyses were restricted to a priori hypotheses regarding average age, correction for total brain volume, functional level of autism participants, magnet strength, and method index as moderators of total CC effect sizes. The file drawer problem (publication bias) was examined by creating a funnel plot and calculating the fail safe N (45). The funnel plot examines the relationship between study effect size and the standard error of the effect size. This plot is particularly useful for examining whether small or medium-sized studies (with larger standard errors) are under-represented in the region of small effect sizes, signaling publication bias toward larger N studies more likely to detect significance. The fail safe N is the number of studies needed to bring the weighted mean effect size down to a negligible value (d=.05). Fail safe N examines the robustness of the weighted mean effect size to publication bias toward studies with significant effects.

Table 2.

Meta-analytic statistics for each classification and corpus callosum region or sub-division.

| Classification | Region | k effect sizes | Md | M | Weighted M | 95% CI | z | Q | Fail Safe N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total CC Area | 10 | .48 | .50 | .48 | .30-.66 | 5.17a | 5.12b | 86 | |

| Major Regions | |||||||||

| Anterior | 8 | .45 | .52 | .49 | .30-.69 | 4.93a | 4.52b | 70 | |

| Mid/Body | 8 | .41 | .46 | .43 | .24-.63 | 4.35a | 5.33b | 61 | |

| Posterior | 8 | .40 | .37 | .37 | .18-.57 | 3.78a | 1.97b | 51 | |

| Witelson | |||||||||

| W1: Rostrum | 5 | .41 | .41 | .49 | .20-.77 | 3.32a | 5.17b | 44 | |

| W2: Genu | 5 | .55 | .55 | .51 | .22-.80 | 3.47a | 6.87b | 46 | |

| W3: Rostral Body | 5 | .52 | .60 | .66 | .37-.95 | 4.47a | 4.70b | 61 | |

| W4: Anterior Midbody | 6 | .46 | .49 | .51 | .25-.76 | 3.88a | 6.87b | 55 | |

| W5: Posterior Midbody | 5 | .52 | .41 | .41 | .15-.68 | 3.07a | 5.22b | 36 | |

| W6: Isthmus | 5 | .26 | .50 | .46 | .19-.73 | 3.39a | 7.73b | 41 | |

| W7: Splenium | 6 | .46 | .39 | .42 | .16-.67 | 3.41a | 1.46b | 44 |

Note. Md=median, M=mean, Q=homogeneity of effect sizes statistic with chi-square distribution. Positive effect sizes indicate a lower value in autism. All values are derived from fixed effects analysis. Fail safe N refers to the number of additional studies with null effects (d=0.00) needed to bring the observed weighted mean effect size down to a negligible effect size d=.05.

p<.001

p>.10.

Results

Ten studies met inclusion criteria with each study providing one effect size (see Table 1). Of these 10 studies, two studies only provided total CC area (33, 34) and two studies only provided data for broad regions but not Witelson subdivisions (24, 27) . One study included only enough information to evaluate W1-4 and W7 (32). Another study only included enough information to evaluate W4-7 (23).

Table 1 presents demographics and study characteristics. Studies contributed 503 total participants (253 with autism and 250 healthy controls). The average age of study participants was 14.5 (SD=5.7) and 86% of study participants were male. Two studies examined low functioning autism (26, 33), four examined mixed samples including both low and high functioning individuals (24, 27, 28, 34), and four studies exclusively examined high functioning autism (17, 23, 25, 32). Importantly, the body of studies included a number of methodologically rigorous reports, with 6 of the 10 studies receiving scores of 12.5 or above (out of 15) on the method index (median=12.75). Of the 7 studies reporting a significant reduction of the total CC area in autism, 3 had an unadjusted 95 % confidence interval that included zero; further supporting the need for a meta-analysis of these studies.

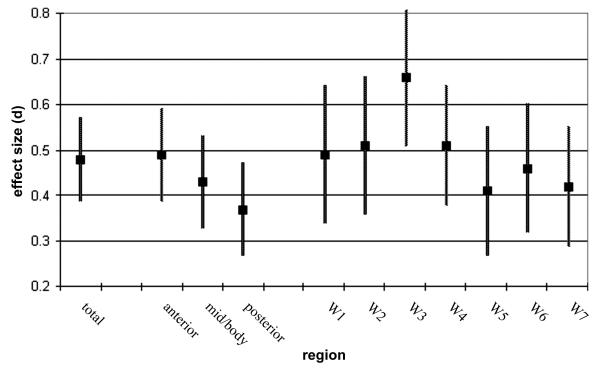

Table 2 presents meta-analytic statistics for total CC area, regions, and Witelson subdivisions. Consistent with expectation, total CC area was significantly reduced in autism patients (z = 5.17, p<.0001). This effect fell at the lower end of the predicted range (weighted mean d=.48, predicted range of d=.50-.80). Areas for each CC region and Witelson subdivision were also significantly reduced in autism (smallest z = 3.07, p<.001). Figure 2 presents weighted mean effect sizes and standard errors for each region and Witelson subdivision. Consistent with expectation, area reductions in CC regions showed a very large linear trend (anterior vs. posterior F(1,7)=3.23, p=.115, d=1.36), and did not reach significance probably due to the small sample (k=8). Similarly, the correlation between Witelson subdivision (numbered 1-7 anterior to posterior) and weighted mean effect sizes was large (r = −.52, d=−1.22, df=5, p=.23), but did not reach significance. Visual inspection of Figure 2 indicates that the rostral body of the CC (Witelson subdivision 3) showed the largest difference (weighted mean d=.66).

Figure 2.

Weighted mean effect sizes (+/− SE) by total, region, and Witelson subdivision.

None of the pooled effect sizes had a significant Q statistic (see Table 2). However, because the Q statistic is under-powered in small samples and a priori predictions were made regarding the relationship between study characteristics and effect sizes, meta-regression was used to examine the relationship between total CC area and potential moderator variables. Meta-regression using weighted least squares indicated a significant overall prediction of weighted effect sizes, adjusted R2=.89, F(5,4)=15.76, p=.010. Age was a significant predictor with increasing age indicating a larger discrepancy between participants with autism and healthy controls, t(4)=4.32, p=.012. Magnet strength was also a marginally significant predictor, t(4)=2.68, p=.055, with stronger magnets showing larger discrepancies between autism and healthy controls. None of the other predictors significantly accounted for unique variance (largest t(4)=1.95, p=.112).

Previous data have suggested that earlier publications in a scientific field tend to yield larger findings, the relationship between publication date and total CC area effect sizes was also examined (46). Contrary to expectation, publication date was positively related to total CC area effect sizes and the effect was significant (β=.76, t(8)=3.26, p=.012). This may be partly due to greater use of more sensitive imaging methods in later publications. The method index did not significantly predict total CC area effect sizes (β=.45, t(8)=1.43, p=.192), indicating that better reporting of study methodology did not influence effect sizes, although the effect was in the expected direction.

Inspection of the funnel plot indicated a relatively even representation of small and moderate N studies across the range of effect sizes (figure available from the first author). The fail safe N (see table 2) indicates that publication bias is an unlikely explanation for the observed effect sizes. Fourteen additional studies each contributing a null effect size (d=.00) would be needed to reduce the observed weighted mean effect size for total CC area to a small effect (d=.20). Eighty-six new studies would be needed to reduce the observed effect size to a negligible effect (d=.05). Similar results were observed for regions and Witelson subdivisions, indicating that publication bias is unlikely to play a substantial role in the present findings.

Discussion

Findings from the present investigation provide strong support to previous studies suggesting involvement of CC in the pathophysiology of autism. The present meta-analytic results indicate that total CC area is smaller in autism; consistent with studies implicating the CC in emotional and social functioning (47) and higher cognitive processes such as decoding non-literal meaning, affective prosody, and understanding humor (48, 49). The CC provides integrated inter-hemispheric communication between homotopic and heterotopic cortical regions (50). Disruption of CC-mediated inter-hemispheric communication may underlie many of the sensory, cognitive, and behavioral symptoms observed in children with autism spectrum disorder.

In the present study the weighted mean effect size for the CC was slightly smaller than anticipated. It is close to the medium range and does not appear to be a result of publication bias. Interestingly, the effect size was found to be large in a recent study using a 3T magnet (d=.73) (23), suggesting that future studies applying newer imaging methodologies (e.g., diffusion tensor imaging or related novel white matter tractography methods) and higher magnet strength are likely to yield larger differentiation of individuals with autism and healthy controls. The present results clarify previous null findings (3 of 10 studies) as either underpowered or due to sampling error. Findings were concordant with studies applying other imaging methods, supporting the aberrant connectivity hypothesis in autism (15-18). These data suggest that brain connectivity is likely to be impaired in most regions as evidenced by alterations of all CC subdivisions and is supported by several functional studies implicating multiple cortical including frontal, and parietal regions (17, 19, 20, 51).

The greatest reduction of CC area was observed in anterior regions providing a neuroanatomical link to the prominent executive dysfunction in autism (37). Furthermore, the largest reduction at Witelson subdivision 3 (rostral body) indicates disruption of fiber tracks originating in pre-/supplementary motor regions (35). Pre-/supplementary motor regions are crucial for motor planning and disruption of these regions may be the neural substrate for impairments in fine motor skills and imitation observed in autism. Several studies have reported abnormalities in motor functioning (52, 53) and imitation (54) when compared to controls. Additionally, these CC regions, while important for motor planning, have also been identified as supporting a subset of mirror neuron functions (55). Thus, the present data may suggest reduced functional output of mirror neuron regions or decreased hemispheric cross-talk between mirror neuron regions. In turn, reduced output or cross-talk of these regions may contribute to reduced attunement to others’ intentions (56).

Total CC reductions were moderated by two major factors: magnet strength and participant age. Increasing magnet strength predicted larger reductions in CC area as would be expected with higher resolution (3T) imaging techniques. Larger CC reductions with advancing age are in agreement with previous white matter findings (5). Increasing reductions in CC size over time might be a downstream consequence of early abnormal cortical development, a result of ongoing neurobiological disruptions, or due to other unknown processes. One possible explanation is that early neural proliferation with abnormal cortical cytoarchitecture and densely-packed minicolumnar organization (3) may lead to poor coordination with distal brain regions. Consequently, developmental alterations of these neural networks may result in reductions over time of long fiber neurons responsible for intra-hemispheric or inter-hemispheric regional communication. Clearly, additional studies incorporating multimodal imaging techniques are needed to tease out these possibilities.

Results reported here are consistent with evidence from investigations examining individuals with agenesis of the CC, pointing to the role that this structure plays in complex brain functions. Several cognitive and social deficits observed in autism have also been described in individuals with agenesis of the CC, although not all individuals with these deficits meet full DSM-IV-TR criteria for autistic disorder. Impairments in abstract reasoning (57, 58), problem solving (59, 60), and generalization (61), as well as emotional immaturity, lack of introspection, impaired social competence, and poor communication of emotions (47, 62, 63) have all been described in individuals with agenesis of the CC in the absence of intellectual disability. Deficits in social judgment and planning (62), decoding non-literal meaning (48), affective prosody and humor (49, 64) have also been reported in both disorders. The clinical similarities between the two disorders highlight the need for a better understanding of the neurobiology of agenesis of CC. This will shed light on the genetic and pathologic contribution of CC structural alterations to cognitive and social deficits observed in neuropsychiatric disorders known to have anatomical abnormalities of the CC.

Limitations and Future Directions

The small study sample size (k=10) makes conclusions concerning moderating factors less certain. Similarly, as in any meta-analysis, the heterogeneity of study methods and samples complicate interpretation of moderating factors. As additional studies are being completed, meta-regression will become more powerful and may uncover additional moderators of the observed effect sizes. Several studies did not include Witelson subdivisions, reducing the ability to statistically examine finer grained differences among CC regions. It is also possible that differences in the magnitude of effects across broad regions and Witelson subdivisions are simply due to sampling error and do not represent real differences, although the pattern of findings appeared congruent with other results in autism research. Additional imaging studies, using diffusion tensor imaging and tractography, may also be helpful for determine which fiber tracts are most responsible for CC reductions.

Despite evidence suggesting moderate reductions in CC area at the group level, not all individuals with autism exhibit reduction in the size of this structure. Coupling larger databases and statistical methods for determining the presence of unique sub-groups, such as mixture modeling, may be useful for uncovering distinct patterns of CC reduction among autism patients. Inclusion of a broader spectrum of autism patients may also be helpful for uncovering CC sub-groups. In turn, these sub-groups may serve as endophenotypes for further neurochemical and genetic exploration.

The present analyses did not include non-autism developmentally delayed controls. Without these controls it is difficult to ascertain whether the CC reduction is specific to autism. In fact, studies of other neuropsychiatric disorders have reported alterations of CC size (65). Further investigations including well-matched psychiatric controls will be useful for determining the specificity of these findings to autism. As the present analysis included only cross-sectional studies, it is difficult to ascertain whether the observed relationship between increasing age and larger reductions in total CC area is an artifact of study differences. Further, cross-sequential and longitudinal studies will be helpful for determining CC reductions across the life span. Growth mixture modeling may be useful for identifying distinct patterns of developmental changes in CC structure and for determining whether rostral brain abnormalities are the primary basis of dysfunction. This is particularly relevant since recent imaging studies in autism have shown that the most abnormal aspect of brain development in this disorder is often the time course and trajectory rather the final product (2, 39).

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by NIMH research grant MH-64027 and MH083972 to Dr. Hardan. Financial Disclosures: Dr. Hardan has received research grants from Bristol-Myers Squibb. He also reports that he has received honoraria for speaking fees from Forest, Pfizer, and AstraZeneca.

Footnotes

None of these are directly relevant to the present paper. Dr. Frazier did not report any relevant biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

References

*indicates inclusion in the meta-analysis

- 1.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Fourth ed American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amaral DG, Schumann CM, Nordahl CW. Neuroanatomy of autism. Trends Neurosci. 2008;31:137–145. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Casanova MF, Buxhoeveden DP, Switala AE, Roy E. Minicolumnar pathology in autism. Neurology. 2002;58:428–432. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.3.428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Courchesne E, Carper R, Akshoomoff N. Evidence of brain overgrowth in the first year of life in autism. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;290:337–344. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.3.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Courchesne E, Karns CM, Davis HR, Ziccardi R, Carper RA, Tigue ZD, et al. Unusual brain growth patterns in early life in patients with autistic disorder: An MRI study. Neurology. 2001;57:245–254. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.2.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Piven J, Arndt S, Bailey J, Havercamp S, Andreasen NC, Palmer P. An MRI study of brain size in autism. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 1995;152:1145–1149. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.8.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lainhart JE. Increased rate of head growth during infancy in autism. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;290:393–394. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.3.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hardan AY, Minshew N, Mallikarjuhn M. Brain volume in autism. J Child Neurol. 2001;16:421–424. doi: 10.1177/088307380101600607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bailey A, Luthert P, Dean A, Harding I, Montgomery M, Rutter M, et al. A clinicopathological study of autism. Brain. 1998;121:889–905. doi: 10.1093/brain/121.5.889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chiu S, Wegelin JA, Blank J, Jenkins M, Day J, Hessl D, et al. Early acceleration of head circumference in children with fragile x syndrome and autism. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2007;28:31–35. doi: 10.1097/01.DBP.0000257518.60083.2d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Butler MG, Dasouki MJ, Zhou X-P, Talebizadeh Z, Brown M, Takahashi TN, et al. Subset of individuals with autism spectrum disorders and extreme macrocephaly associated with germline PTEN tumour suppressor gene mutations. J Med Genet. 2005;42:318–321. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.024646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williams CA, Dagli A, Battaglia A. Genetic disorders associated with macrocephaly. Am J Med Genet A. 2008;146A:2023–2037. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kwon CH, Luikart BW, Powell CM, Zhou J, Matheny SA, Zhang W, et al. Pten regulates neuronal arborization and social interaction in mice. Neuron. 2006;50:377–388. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Williams DL, Minshew NJ. Understanding autism and related disorders: What has imaging taught us? Neuroimaging Clin N Am. 2007;17:495–509. doi: 10.1016/j.nic.2007.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herbert MR, Ziegler DA, Makris N, Filipek PA, Kemper TL, Normandin JJ, et al. Localization of white matter volume increase in autism and developmental disorder. Ann Neurol. 2004;55:530–540. doi: 10.1002/ana.20032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Horwitz B, Rumsey JM, Grady CL, Rapoport SI. The cerebral metabolic landscape in autism: intercorrelations of regional glucose utilization. Arch Neurol. 1988;45:749–755. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1988.00520310055018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *17.Just MA, Cherkassky VL, Keller TA, Kana RK, Minshew NJ. Functional and anatomical cortical underconnectivity in autism: Evidence from an fMRI study of an executive function task and corpus callosum morphometry. Cereb Cortex. 2007;17:951–961. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhl006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Castelli F, Frith C, Happe F, Frith U. Autism, Asperger Syndrome, and brain mechanisms for the attribution of mental states to animated shapes. Brain. 2002;125:1839–1849. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koshino H, Carpenter PA, Minshew NJ, Cherkassky VL, Keller TA, Just MA. Functional connectivity in an fMRI working memory task in high functioning autism. Neuroimage. 2005;24:810–821. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Just MA, Cherkassky VL, Keller TA, Minshew NJ. Cortical activation and synchronization during sentence comprehension in high-functioning autism: evidence of underconnectivity. Brain. 2004;127:1811–1821. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Plunkett K, Karmiloff-Smith A, Bates E, Elman J. Connectionism and developmental psychology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1997;38:53–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01505.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spencer MD, Moorhead WJ, Lymer KS, Job DE, Muir WJ, Hoare P, et al. Structural correlates of intellectual impairment and autistic features in adolescents. Neuroimage. 2006;33:1136–1144. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *23.Vidal CN, Nicolson R, DeVito TJ, Hayashi KM, Geaga JA, Drost DJ, et al. Mapping corpus callosum deficits in autism: An index of aberrant cortical connectivity. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60:218–225. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *24.Piven J, Bailey J, Ranson BJ, Arndt S. An MRI study of the corpus callosum in autism. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154:1051–1056. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.8.1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *25.Hardan AY, Minshew NJ, Keshavan MS. Corpus callosum size in autism. Neurology. 2000;55:1033–1036. doi: 10.1212/wnl.55.7.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *26.Manes F, Piven J, Vrancic D, Nanclares V, Plebst C, Starkstein SE. An MRI study of the corpus callosum and cerebellum in mentally retarded autistic individuals. The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 1999;11:470–474. doi: 10.1176/jnp.11.4.470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *27.Egaas B, Courchesne E, Saitoh O. Reduced size of corpus callosum in autism. Arch Neurol. 1995;52:794–801. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1995.00540320070014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *28.Boger-Megiddo I, Shaw DW, Friedman SD, Sparks BF, Artru AA, Giedd JN, et al. Corpus callosum morphometrics in young children with autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2006;36:733–739. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0121-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alexander AL, Lee JE, Lazar M, Boudos R, DuBray MB, Oakes TR, et al. Diffusion tensor imaging of the corpus callosum in autism. Neuroimage. 2007;34:61–73. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Waiter GD, Williams JHG, Murray AD, Gilchrist A, Perrett DI, Whiten A. Structural white matter deficits in high-functioning individuals with autistic spectrum disorder: a voxel-based investigation. Neuroimage. 2005;24:455–461. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.08.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chung MK, Dalton KM, Alexander AL, Davidson RJ. Less white matter concentration in autism: 2D voxel-based morphometry. Neuroimage. 2004;23:242–251. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *32.Rice SA, Bigler ED, Cleavinger HB, Tate DF, Sayer J, McMahon W, et al. Macrocephaly, corpus callosum morphology, and autism. J Child Neurol. 2005;20:34–41. doi: 10.1177/08830738050200010601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *33.Elia M, Ferri R, Musumeci SA, Panerai S, Bottitta M, Scuderi C. Clinical correlates of brain morphometric features of subjects with low-functioning autistic disorder. J Child Neurol. 2000;15:504–508. doi: 10.1177/088307380001500802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *34.Gaffney GR, Kuperman S, Tsai LY, Minchin S, Hassanein KM. Midsaggital magnetic resonance imaging of autism. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;151:831–833. doi: 10.1192/bjp.151.6.831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Witelson SF. Hand and sex differences in the isthmus and genu of the human corpus callosum. Brain. 1989;112:799–835. doi: 10.1093/brain/112.3.799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lenroot RK, Giedd JN. Brain development in children and adolescents: Insights from anatomical magnetic resonance imaging. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2006;30:718–729. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Geurts HM, Verte S, Oosterlaan J, Roeyers H, Sergeant JA. How specific are executive functoning deficits in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and autism? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2004;45:836–854. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ozonoff S, Jensen J. Specific executive function profiles in three neurodevelopmental disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 1999;29:171–177. doi: 10.1023/a:1023052913110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pardo CA, Eberhart CG. The neurobiology of autism. Brain Pathol. 2007;17:434–447. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2007.00102.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd edition Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lord C, Rutter M, DiLavore PC, Risi S. Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule: ADOS manual. Western Psychological Services; Los Angeles, CA: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lord C, Rutter M, LeCouteur A. Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised: a revised version of a diagnostic interview for caregivers of individuals with possible pervasive developmental disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 1994;24:569–685. doi: 10.1007/BF02172145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lipsey MW, Wilson DB. Practical Meta-analysis. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hedges LV, Olkin I. Statistical methods for meta-analysis. Academic Press; Orlando, FL: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Orwin RG. A fail-safe N for effect size in meta analysis. Journal of Educational Statistics. 1983;8:157–159. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rosenthal R. Meta-analytic procedures for social research. Sage Publications; Newbury Park, CA: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Badaruddin DH, Andrews GL, Bolte S, Schilmoeller KJ, Paul LK, Brown WS. Social and behavioral problems of children with agenesis of the corpus callosum. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2007;38:287–302. doi: 10.1007/s10578-007-0065-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brown W, Symingtion M, VanLancker-Sidtis D, Dietrich R, Paul L. Paralinguistic processing in children with callosal agenesis: emergence of neurolinguistic deficits. Brain Lang. 2005;93:135–139. doi: 10.1016/j.bandl.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brown WS, Paul LK, Symingtion M, Dietrich R. Comprehension of humor in primary agenesis of the corpus callosum. Neuropsychologia. 2005;43:906–916. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2004.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Paul LK, Brown WS, Adolphs R, Tyszka JM, Richards LJ, Mukherjee P, et al. Agenesis of the corpus callosum: Genetic, developmental and functional aspects of connectivity. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2007;8:287–299. doi: 10.1038/nrn2107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kana RK, Keller TA, Cherkassky VL, Minshew NJ, Just MA. Sentence comprehension in autism: Thing in pictures with decreased functional connectivity. Brain. 2006;129:2484–2493. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Larson JC, Mostofsky SH. Motor deficits in autism. In: Tuchman R, Rapin I, editors. Autism: A neurological disorder of early brain development. Mac Keith Press; London: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hardan AY, Kilpatrick M, Keshavan MS, Minshew N. Motor performance and anatomical magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the basal ganglia in autism. J Child Neurol. 2003;18:317–324. doi: 10.1177/08830738030180050801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rogers SJ, Bennetto L, McEvoy R, Pennington BF. Imitation and pantomime in high-functioning adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Child Dev. 1996;67:2060–2073. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Oberman LM, Ramachandran VS. The simulating social mind: The role of the mirror neuron system and simulation in the social and communicative deficits of autism spectrum disorders. Psychol Bull. 2007;133:310–327. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.2.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gallese V, Eagle MN, Migone P. Intentional attunement: mirror neurons and the neural underpinnings of interpersonal relations. J Am Psychoanal Assoc. 2007;55:131–176. doi: 10.1177/00030651070550010601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.David AS, Wacharasindhu A, Lishman WA. Severe psychiatric disturbance and abnormalities of the corpus callosum: review and case series. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1993;56:85–93. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.56.1.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Brown LN, Sainsbury RS. Hemispheric equivalence and age-related differences in judgments of simultaneity to somatosensory stimuli. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2000;22:587–598. doi: 10.1076/1380-3395(200010)22:5;1-9;FT587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Aalto S, Naatanen P, Wallius E, Metsahonkala L, Stenman H, Niem PM, et al. Neuroanatomical substrata of amusement and sadness: a PET activation study using film stimuli. Neuroreport. 2002;13:67–73. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200201210-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fischer M, Ryan SB, Dobyns WB. Mechanisms of interhemispheric transfer and patterns of cognitive function in acallosal patients of normal intelligence. Arch Neurol. 1992;49:271–277. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1992.00530270085023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Solursh LP, Margulies AI, Ashem B, Stasiak EA. The relationships of agenesis of the corpus callosum to perception and learning. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1965;141:180–189. doi: 10.1097/00005053-196508000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Brown WS, Paul LK. Cognitive and psychosocial deficits in agenesis of the corpus callosum with normal intelligence. Cognitive Neuropsychiatry. 2000;5:135–157. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Stickles JL, Schilmoeller GL, Schilmoeller KJ. A 23-year review of communication development in an individual with agenesis of the corpus callosum. International Journal of Disability, Development, and Education. 2002;49:367–383. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tager-Flusberg H. Cognitive neuroscience of autism. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2008;14:917–921. doi: 10.1017/S1355617708081423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hutchinson AD, Mathias JL, Banich MT. Corpus callosum morphology in children and adolescents with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: A meta-analytic review. Neuropsychology. 2008;22:341–349. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.22.3.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]