Abstract

Rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS), consisting of alveolar (aRMS) and embryonal (eRMS) subtypes, is the most common type of sarcoma in children. Currently, there are no targeted drug therapies available for RMS. In searching for new molecular therapeutic targets, we performed genome-wide siRNA library screens targeting human phosphatases (n=206) and kinases (n=691) initially against an aRMS cell line, RH30. Sixteen phosphatases and 50 kinases were identified based on growth inhibition after 72 hours. Inhibiting polo-like kinase 1 (PLK1) had the most remarkable impact on growth inhibition (~80%) and apoptosis on all three RMS cell lines tested including RH30, CW9019 (aRMS) and RD (eRMS), while there was no effect in normal muscle cells. The loss of PLK1 expression and subsequent growth inhibition correlated with decreased p-CDC25C and Cyclin B1. Increased expression of WEE 1 was also noted. The induction of apoptosis after PLK1 silencing was confirmed by increased p-H2AX, propidium iodide uptake, chromatin condensation, as well as caspase-3 and PARP cleavage. Pediatric Ewing’s sarcoma (TC-32), neuroblastoma (IMR32 and KCNR) and glioblastoma (SF188) models were also highly sensitive to PLK1 inhibition. Finally, based upon cDNA microarray analyses, PLK1 mRNA was over-expressed (>1.5 fold) in 10/10 RMS cell lines and in 47% and 51% of primary aRMS (17/36 samples) and eRMS (21/41 samples) tumors, respectively, compared to normal muscles. Similarly, pediatric Ewing’s sarcoma, neuroblastoma and osteosarcoma tumors expressed high PLK1. We conclude that PLK1 could be a promising therapeutic target for the treatment of a wide range of pediatric solid tumors including RMS.

Keywords: siRNA library, phosphatases, kinases, rhabdomyosarcoma, polo-like kinase 1

Introduction

Rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS) is the most common soft-tissue sarcoma of children and adolescents. The majority (66%) of cases of RMS are diagnosed in children younger than 6 years of age (1). This disease is thought to arise from primitive mesenchymal progenitors that have undergone a limited program of myogenic differentiation (2). RMS consists of a highly heterogeneous family of tumors showing varying degrees of skeletal muscle differentiation (3). Embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma (eRMS) and the morphological spindle/botryoid variants are associated with intermediate and superior patient prognosis, respectively, while alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma (aRMS) is more aggressive with a high frequency of metastasis at the time of initial diagnosis (4). Current treatment for RMS includes chemotherapy, radiation and surgery. The “gold standard” chemotherapeutic agents vincristine, actinomycin D and cyclophosphamide are commonly prescribed to RMS patients (1). Chemoresistance is fairly common as are treatment related side-effects (1, 5). This is coupled to the fact that the present cure rate for children with metastatic RMS is still only 20 – 30% (6, 7). Unlike advanced treatment strategies for other types of malignancies, there are no targeted drug therapies available for RMS that could potentially improve overall cure rates and reduce morbidity. Thus identifying new molecular targets of the disease is necessary.

Loss of heterozygosity on the short arm of chromosome 11 (11p15.5) characterizes eRMS (8). In contrast, aRMS harbor the reciprocal chromosomal translocations t(2;13)(q35;q14) or t(1;13)(p36;q14), generating a chimeric fusion gene involving the PAX3 gene (chromosome 2) or PAX7 (chromosome 1) and FKHR (chromosome 13), a member of the fork-head family (9). The resulting gene fusions encode PAX3-FKHR and PAX7-FKHR proteins that combine transcriptional domains from corresponding wild-type proteins and are more potent transcription factors (10). These proteins induce cell transformation, inhibit myogenic differentiation and apoptosis, and thus enhance oncogenic activity (11). Recently, several gene expression studies of primary RMS tumors have provided new information about the pathways involved in RMS (6, 12–19). New evidence indicates that aRMS can be experimentally induced by expressing PAX/FKHR fusions gene in mesenchymal stem cells followed by the introduction of activating RAS mutation (20). Despite new knowledge and the belief that RMS arises from disrupted proliferation and differentiation of skeletal muscle progenitor cells, the mechanisms of growth control of RMS are not fully understood.

Kinases and phosphatases control the reversible processes of phosphorylation and are deregulated in many diseases, such as cancer. A recent study of genome-wide small interfering RNA (siRNA) libraries against the HeLa cervical carcinoma cell line has demonstrated that a variety of phosphatases and kinases are critical in cancer cell survival (21). Kinase inhibitors targeting PAX3-FKHR, IGF-1R, CDK4/6 and EGFR have also shown potent anti-tumorigenic activity on RMS under in vitro and in vivo conditions (5, 7, 22–24). It is reported that phosphorylation levels of receptors and non-receptor tyrosine kinases, as well as protein kinase C, are elevated in RMS tumors and therefore have high therapeutic potential (25). These studies indicate that interfering with key signal transduction pathways may lead to improved therapies for RMS. However, genome-wide screens have not been reported to date.

In this study, we screened two siRNA libraries of 897 human phosphatases and kinases against an aRMS cell line, RH30 (SJCRH30), with the goal of finding novel therapeutic targets for this particular type of cancer.

Materials and Methods

Cell Lines

RMS cell lines, RH30, CW9019 and RD, and a mouse muscle cell line, C2C12, were cultured in Dullbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium purchased from Invitrogen; a human pediatric glioblastoma multiforme cell line, SF188, was cultured in MEM/EBSS medium from Hyclone; an Ewing’s sarcoma, TC-32 and two neuroblastoma cell lines, IMR32 and KCNR, were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium from Invitrogen. All media contained 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) except for TC-32, IMR32 and KCNR cells that were grown in medium with 15% FBS. The cell lines were maintained at 5% CO2 at 37°C and subcultured twice weekly during the experimental period.

Phosphatase and Kinase siRNA Libraries

The siRNA libraries (V2.0) of 206 phosphatases and 691 kinases were purchased from Qiagen. There are two different sequences of siRNAs targeting each of the genes in the libraries. The siRNA samples were supplied in 96-well plates. They were diluted to working stocks at 2uM upon arrival following the manufacturer’s instructions, and stored at −20°C until use.

siRNA Library Screen and High Content Screening (HCS) Analysis

RH30 cells were seeded (5000/well) into each well of 96-well plates (Becton Dickinson) overnight. The cells were then transfected with siRNA using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’s instruction. The final concentration of siRNA was 5 nM in 120 µl medium per well. The assay plates were incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 72 h. Forty minutes before the end of siRNA treatment, nuclear dyes, Hoechst 33342 and propidium iodide (PI) (Sigma-Aldrich) were added to each well of the 96-well plates to give a final concentration of 1 µg/ml of each dye, and the plates were incubated as before. The cells were washed gently with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) three times before the cells were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde. The plates were kept at 4°C in the dark before analysis on the ArrayScan HCS system (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Twenty focus fields per cell well were scanned and analyzed. The screen was repeated at least once to confirm the activity of siRNAs. Cells treated with Lipofectamine RNAiMAX alone without siRNA served as controls. Additionally, scrambled siRNAs and green fluorescent protein siRNAs were included in the libraries, and served as internal references in each assay plate. Apoptosis was identified by nuclear morphology and dye intensity by the ArrayScan HCS system (26). Growth inhibition was calculated as a percentage of the control. To focus on the phosphatases and kinases with the most significant effect on cell growth, only those siRNAs that were active for both sequences and showed a minimum of 30% inhibition compared to control were considered to be active in the screen.

Effects of Silencing the Selected Phosphatases and Kinases in Different RMS Cell Lines

To evaluate whether the active phosphatases and kinases identified in the primary screen are similarly active in different RMS cell types, twelve phosphatases and 16 kinases were silenced in two additional RMS cell lines, CW9019 (aRMS) and RD (eRMS). The experimental methods are the same as described above for the library screen.

Analysis of the Active Genes by IPA

To explore the possible links or interactions among the active phosphatases and kinases identified in the siRNA library screen, IPA software by Ingenuity Systems was employed to further analyze these genes and to group them into functional categories (4) and cell signaling pathways.

Effect of PLK1 Knocking Down on Pediatric Cancer Cell Lines in vitro

To test the effect of silencing PLK1 on cell growth in vitro, RH30, CW9019, RD, SF188 and C2C12 cell lines were cultured and transfected with PLK1 siRNA as described above for the library screen with the addition of six replicates for each treatment.

Immunofluorescent Assays and Immunoblotting

To directly visualize the expression of PLK1 in cells, RH30, CW9019, RD and SF188 cells were seeded at 1.0 × 105 cells on glass cover slips, washed with PBS, fixed with 2% formaldehyde for 20 min and rinsed twice with PBS. The slides were then incubated with PBS containing 0.1% saponin (Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 min. Next, the cover slips were washed with PBS, and incubated with either rabbit anti-PLK1(8–21) antibody (1:100, Calbiochem) or (for double-staining) a mixture of mouse anti-PLK1 antibody (1:100, Sigma-Aldrich) with rabbit antibody against either p-CDC25C Ser198 (1:100; Cell Signaling Technology), cyclin B1(M-20) or WEE 1(C-20) ( 1:100, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) dissolved in buffer containing 10% bovine serum albumin and 2% goat serum for 1 h at room temperature in a humidified container. After washing three times with PBS, the slides were incubated with Alexa 488 anti-rabbit antibody or mixture of Alexa 546 anti-mouse antibody and Alexa 488 anti-rabbit antibody (for double-staining) for 1 h, washed three times and then mounted with Vectashield mounting medium from Vector Laboratories. Hoechst 33342 dye was used for nuclear staining.

The silencing efficacy of PLK1 siRNA on protein expression was tested using standard SDS-PAGE methods (27) on a panel of pediatric cancer cell lines, including RH30, CW9019, RD, SF188, TC-32 (Ewing’s sarcoma), IMR32 and KCNR (neuroblastoma) and C2C12 (mouse myoblast). Primary antibodies used for the studies and their dilutions were as follows: anti-PLK1 (1:5000; Sigma-Aldrich), anti-caspase 3 (cleaved), anti-PARP (cleaved) and anti-pan-actin (1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology). Apoptosis of the cells was simultaneously assessed by probing with anti-p-H2AXS139 antibody (1: 1000) from Abcam. Apoptosis after PLK1 siRNA treatment of RH30, CW9019, RD and SF188 cells was also analyzed quantitatively on the HCS system using PI and p-H2AXS139 as indicators as described (26).

PLK1 mRNA Expression in RMS Cell Lines and Primary Tumors

RMS cell lines used for microarray analysis included five eRMS cell lines (Birch, RD, TTC-442, TTC-516, and TTC-1318), one aRMS fusion-negative cell line (RH18), and four aRMS FAX3-FKHR fusion-positive cell lines (HR, JR-C, RH28, and RH30). All RMS cell lines were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium with 10% FBS (Invitrogen).

Frozen tumor samples from patients enrolled in the Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study Group (IRS-IV and IRS-V) Children’s Oncology Group clinical trials were obtained from the Pediatric Cooperative Human Tissue Network (CHTN) tumor bank. Additional tumor samples and normal (5 yrs old) or fetal skeletal muscle samples were obtained from the Childrens Hospital Los Angeles (CHLA) institutional tumor bank. Histopathologic diagnoses were based on the International Classification of Rhabdomyosarcoma criteria (28). All tumor samples contained >80% tumor cells. Total RNA extraction, gene expression microarrays and data analysis were performed as previously described (29, 30).

PLK1 mRNA Expression in Primary Tumors of Pediatric Ewing’s Sarcoma, Neuroblastoma and Osteosarcoma

To assess expression of PLK1 in other pediatric solid tumors, as well as in normal human tissues, whole genome expression profiling data from Affymetrix GeneChip Human Exon 1.0 ST oligonucleotide microarrays was analyzed. For tumor studies, total RNA was isolated from samples acquired from the CHLA tumor bank with preparation and labeling of RNA for array hybridization performed in the CHLA genome core facility according to Affymetrix protocols. Data files for 33 normal tissue samples (11 different tissues in triplicate) were downloaded from the Affymetrix website (http://www.affymetrix.com/support/technical/sample_data/exon_array_data.affx). Raw signal data from all normal and tumor cell files was analyzed using Partek Genomics Suite software (Partek). Signal intensities for core probesets were quantile normalized by robust multichip averaging and transcript expression levels determined by median summarization.

Results

siRNA Library Screen Identifies Phosphatases and Kinases Central to the Growth Control of RMS

In this study, we profiled the impact of each human kinase and phosphatase by transfecting RH30 cells with 5 nM siRNA in duplicate using two unique oligonucleotides. Cell growth was assessed 72 h later by Hoechst 33342 staining using a HCS system. From this screen, we determined that 16 of the 206 phosphatases (~8% of all the known phosphatases) evaluated played a significant role in proliferation and survival of RH30 cells in vitro (Table 1). The degree of growth inhibition ranged from 30 – 80% and in some instances apoptosis was also observed. Much of the anti-tumor activity was observed in protein (tyrosine and serine/threonine) phosphatases (Table 1). We queried public databases for evidence of these phosphatases in RMS. Notably almost all of these “survival phosphatases” have previously been shown to be either up-or down-regulated in RMS tumor samples compared to normal muscle (Table 1), and they are thus potential therapeutic targets for RMS. With respect to the kinase screen, 50 of the 691 kinases (~7% of the kinome) were shown to play a significant role in the growth and survival of RH30 cells in vitro (Table 2). Knocking down these kinases by siRNAs caused an overall 30 – 80% growth inhibition and/or apoptosis. Most of the active kinases are functionally related to cell cycle, cell death, MAPK signaling and lipid metabolism (Table 2). Approximately one-third of the identified kinases are known to be expressed, either down- or up-regulated, in RMS tumor samples (Table 2). Yet, most of them have not previously been associated with RMS. Of particular note, PLK1 was one of the most important “survival kinases” for RMS identified in this screen. Further validation of this exciting lead is described below.

Table 1.

Active phosphatases identified in the siRNA library screen and their expression status in primary RMS

| Accession No. | Symbol | Gene description | Growth inhibition (%) (sequence C) |

Growth inhibition (%) (sequence D) |

Gene expression status |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NM_006240 | PPEF1 | Protein phosphatase, EF hand calcium- binding domain1 |

39.7 | 44.7 | ↑ | 19 |

| NM_002714 | PPP1R10 | Protein phosphatase 1, regulatory subunit 10 |

42.5 | 62* | ↓ | 19 |

| NM_002480 | PPP1R12A | Protein phosphatase 1, regulator (inhibitor) subunit 12A |

36.8 | 46.6 | ↑ | 19 |

| NM_017607 | PPP1R12C | Protein phosphatase 1, regulatory (inhibitor) subunit 12C |

46.7 | 68.9* | - | |

| NM_017726 | PPP1R14D | Protein phosphatase 1, regulatory (inhibitor) subunit 14D |

33.2 | 49.8 | ↓ | 19 |

| NM_032833 | PPP1R15B | Protein phosphatase 1, regulatory (inhibitor) subunit 15B |

38.5 | 39.7 | - | |

| NM_002721 | PPP6C | Protein phosphatase 6, catalytic subunit | 44.8 | 44.3 | ↓ | 19 |

| NM_139283 | TA-PP2C | T-cell activation protein phosphatase 2C | 37 | 38.1 | - | |

| Protein tyrosine phosphatases (and associated proteins) | ||||||

| NM_003625 | PPFIA2 | Protein tyrosine phosphatase, receptor type, f polypeptide (PTPRF), interacting protein (liprin), alpha 2 |

50 | 36.4 | ↑ | 19 |

| NM_002836 | PTPRA | Protein tyrosine phosphatase, receptor type, A |

59.8* | 43.4 | - | |

| NM_002842 | PTPRH | Protein tyrosine phosphatase, receptor type, H |

39.9* | 73.1* | ↓ | 19 |

| NM_002846 | PTPRN | Protein tyrosine phosphatase, receptor type, N |

76.4* | 42 | ↓ | 19 |

| NM_017823 | DUSP23 | Dual specificity phosphatase 23 | 39.4 | 60.7 | - | |

| Lipid phosphatases (and associated proteins) | ||||||

| NM_019061 | PIP3AP | Phosphatidylinositol-3-phosphate associated protein |

55.9 | 73.7 | ↓ | 19 |

| NM_016532 | SKIP | Skeletal muscle and kidney enriched inositol phosphatase |

60.5* | 42* | ↓ | 19 |

| Miscellaneous | ||||||

| NM_001948 | DUT | dUTP pyrophosphatase | 51.3 | 70.4 | - | |

Gene expression status: -: unknown. ↑or ↓: overexpression or down-regulated in relation to normal muscle as stated in corresponding references.

apoptosis is at least 5% more than the control based on nuclear properties (nuclear condensation and higher Hoechst intensity).

Table 2.

Active kinases identified in the siRNA library screen and their status in primary tumors

| Accession No. | Symbol | Gene description | Growth inhibition (%) (sequence C) |

Growth inhibition (%) (sequence D) |

Gene expression status |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell cycle | ||||||

| NM_004217 | AURKB | aurora kinase B | 56.1 | 53.7 | - | |

| NM_001204 | BMPR2 | bone morphogenetic protein receptor, type II (serine/threonine kinase) |

43.2 | 35.4 | - | |

| NM_001743 | CALM2 | calmodulin 2 (phosphorylase kinase, delta) |

32.7 | 39.4 | ↓ | 19 |

| NM_033487 | CDC2L1 | cell division cycle 2-like 1 (PITSLRE proteins) |

69.7 | 65.6 | - | |

| NM_003718 | CDC2L5 | cell division cycle 2-like 5 (cholinesterase- related cell division controller |

34.7 | 39 | - | |

| NM_000075 | CDK4 | cyclin-dependent kinase 4 | 47.3 | 42.1 | ↑ or ↓ | 17, 19, 22; 15 |

| NM_001260 | CDK8 | cyclin-dependent kinase 8 | 36.7 | 35.3 | - | |

| NM_001826 | CKS1B | CDC28 protein kinase regulatory subunit 1B |

45.3 | 37.3 | ↑ | 16 |

| NM_001896 | CSNK2A2 | casein kinase 2, alpha prime polypeptide | 62.7* | 35.3 | - | |

| NM_022740 | HIPK2 | homeodomain interacting protein kinase 2 |

33 | 49.4 | ↓ | 19 |

| XM_498294 | LOC392265 | similar to Cell division protein kinase 5 (Tau protein kinase II catalytic subunit) (TPKII catalytic subunit) (Serine/threonine-protein kinase PSSALRE) |

61 | 52 | - | |

| NM_033118 | MYLK2 | myosin light chain kinase 2, skeletal muscle |

34.8 | 35.7 | ↑ or ↓ | 15; 16 |

| NM_033116 | NEK9 | NIMA (never in mitosis gene a)- related kinase 9 |

43.9 | 44.4 | - | |

| NM_002513 | NME3 | non-metastatic cells 3, protein expressed in |

37.1 | 48.8 | ↑ | 19 |

| NM_006206 | PDGFRA | platelet-derived growth factor receptor, alpha polypeptide |

66.4* | 44.8 | ↑ or ↓ | 6, 31; 17 |

| NM_005030 | PLK1 | polo-like kinase 1 (Drosophila) | 87.6* | 86.9* | ↑ | This study |

| NM_006254 | PRKCD | protein kinase C, delta | 52.5 | 46.2* | ↑ | 25 |

| NM_006257 | PRKCQ | protein kinase C, theta | 40 | 36.7 | ↑ | 25 |

| NM_003318 | TTK | TTK protein kinase | 48.8 | 37.5 | ↑ | 19 |

| NM_005983 | SKP2 | S-phase kinase-associated protein 2 (p45) |

46.3 | 38.6 | ↑ | 16, 19 |

| Cell death | ||||||

| NM_004119 | FLT3 | fms-related tyrosine kinase 3 | 50.7 | 44.7 | ↓ | 19 |

| NM_002625 | PFKFB1 | 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6- biphosphatase 1 |

34.4 | 44.4 | ↓ | 19 |

| NM_006212 | PFKFB2 | 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6- biphosphatase 2 |

52.1 | 38.3 | ↓ | 19 |

| NM_005592 | MUSK | muscle, skeletal, receptor tyrosine kinase | 36.1 | 41.2 | ↓ | 19 |

| NM_032409 | PINK1 | PTEN induced putative kinase 1 | 44.6 | 40 | - | |

| NM_016457 | PRKD2 | protein kinase D2 | 38.4 | 52.4* | - | |

| NM_022445 | TPK1 | thiamin pyrophosphokinase 1 | 37.8 | 54* | - | |

| Lipid metabolism | ||||||

| NM_153273 | IHPK1 | inositol hexaphosphate kinase 1 | 31.2 | 45.5 | - | |

| NM_018323 | PI4K2B | phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase type-II beta | 40.3 | 34.2 | - | |

| NM_004570 | PIK3C2G | phosphoinositide-3-kinase, class 2, gamma polypeptide |

44.4 | 44.9 | - | |

| NM_005027 | PIK3R2 | phosphoinositide-3-kinase, regulatory subunit 2 (p85 beta) |

54 | 50.5 | ↓ | 19 |

| MAPK signaling | ||||||

| NM_002756 | MAP2K3 | mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 3 | 32.4 | 43* | ↓ | 19 |

| NM_005922 | MAP3K4 | mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 4 |

34.5 | 45.3 | - | |

| NM_005456 | MAPK8IP1 | mitogen-activated protein kinase 8 interacting protein 1 |

42.3 | 49.4 | - | |

| NM_015133 | MAPK8IP3 | mitogen-activated protein kinase 8 interacting protein 3 |

43.4 | 54.1 | - | |

| NM_024117 | MAPKAP1 | mitogen-activated protein kinase associated protein 1 |

34.4 | 48.2 | ↓ | 19 |

| Miscellaneous | ||||||

| NM_178510 | ANKK1 | ankyrin repeat and kinase domain containing 1 |

53 | 40.4 | - | |

| NM_005876 | APEG1 | aortic preferentially expressed protein 1 | 52.4 | 38.9 | ↓ | 19 |

| NM_006383 | CIB2 | calcium and integrin binding family member 2 |

31.9 | 40.6 | ↓ | 19 |

| NM_017729 | EPS8L1 | EPS8-like 1 | 47.6* | 37.2 | - | |

| NM_145059 | FUK | fucokinase | 60.2* | 42.4 | - | |

| NM_004712 | HGS | hepatocyte growth factor-regulated tyrosine kinase substrate |

33.8 | 38 | - | |

| NM_020836 | KIAA1446 | brain-enriched guanylate kinase- associated protein |

36.7 | 43 | ↓ | 19 |

| XM_292160 | MGC75495 | similar to Serine/threonine-protein kinase Nek1 (NimA- related protein kinase 1) |

49.1 | 49.3 | - | |

| NM_012395 | PFTK1 | PFTAIRE protein kinase 1 | 53.8* | 36 | - | |

| NM_181805 | PKIG | protein kinase (cAMP-dependent, catalytic) inhibitor gamma |

33.4 | 45.9 | - | |

| NM_052902 | STK11IP | serine/threonine kinase 11 interacting protein |

47 | 46.2 | - | |

| NM_015000 | STK38L | serine/threonine kinase 38 like | 53.7* | 33.9 | - | |

| NM_031432 | UCK1 | uridine-cytidine kinase 1 | 49.5 | 54.5 | - | |

| NM_144624 | UHMK1 | U2AF homology motif (UHM) kinase 1 | 46.6 | 40.7 | - | |

Gene expression status: -: unknown. ↑ or↓: overexpression or down-regulated in relation to normal muscle as stated in corresponding references.

apoptosis is at least 5% more than the control based on nuclear properties (nuclear condensation and higher Hoechst intensity).

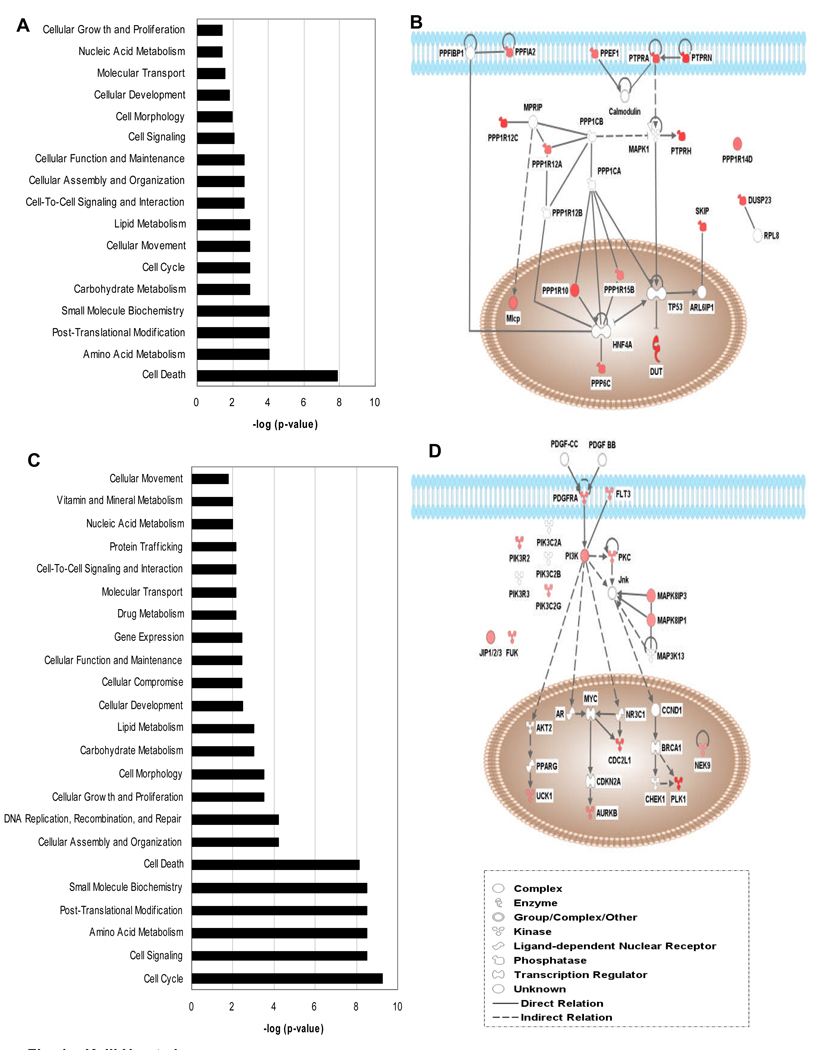

To understand how the identified phosphatases and kinases are functionally related to one another the data were analyzed using IPA. IPA employs proprietary databases to establish cell signaling networks based on peer-reviewed publications. The analysis confirmed the functional categories of phosphatases and kinases based on gene ontology and demonstrated that there is a significant association of the identified genes with functions in cell cycle, cell death, and metabolism (Table 1 and 2; Fig. 1). Of the 50 kinases identified, many of them are directly or indirectly involved in MAPK, PI3K and Jnk pathways, that lead to the eventual activation of PLK1 (Fig. 1D). On a genome-wide scale, the present study provides new clues about the growth control of RMS cells and important signaling networks involved. This information may lead to the development of novel therapeutic approaches in the future.

Figure 1.

Active phosphatases and kinases grouped into functional categories as well as cell signaling pathways by IPA analysis. A, Functional categories of phosphatases. B, Simplified signaling pathways for phosphatases. C, Functional categories of kinases. D, Simplified signaling pathways for kinases. Note the small p-values and thus large –log (p-value) indicating significant association rather than random observation for categories such as cell cycle, cell death, etc. The p-value is calculated with the right-tailed Fisher's Exact Test according to IPA. Only those that have more Functions/Pathways/Lists Eligible molecules than expected by chance are significant.

Ablation of Identified Phosphatases and Kinases Inhibits the Growth of Both aRMS and eRMS in vitro

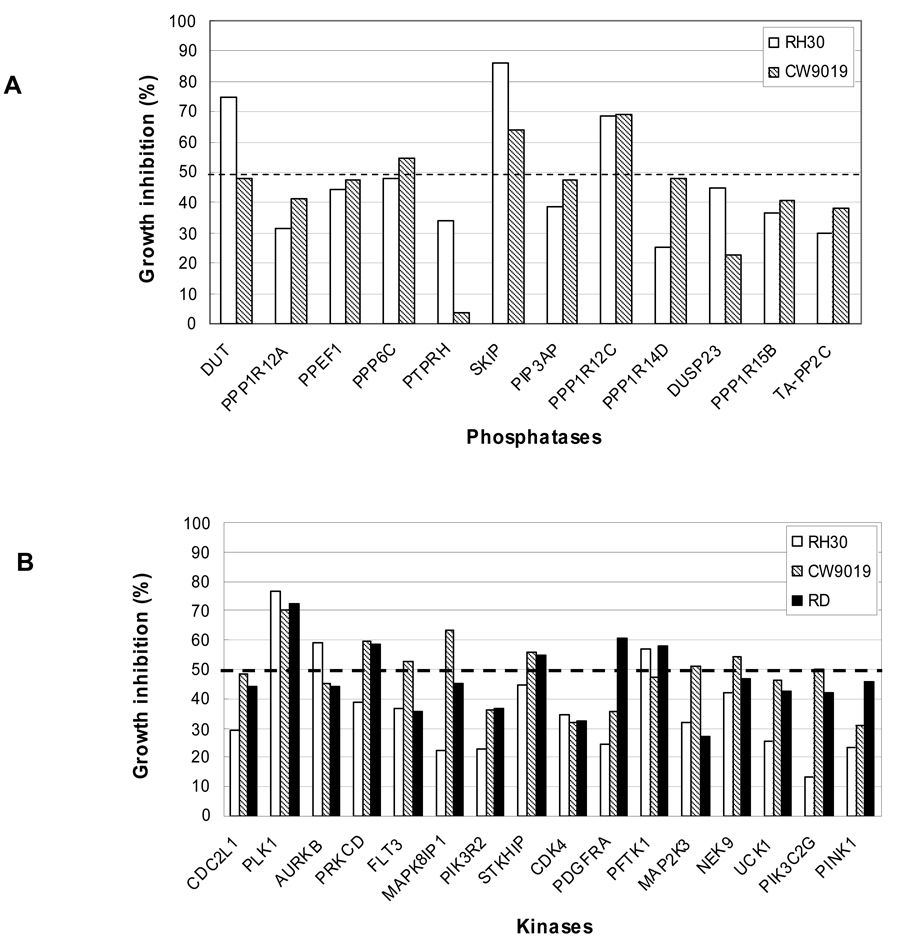

Given the molecular heterogeneity of RMS and the initial aRMS-based screen, the effects of silencing selected phosphatases and kinases that were identified in the primary screen were further tested on two additional RMS cell lines, CW9019 (aRMS) and RD (eRMS). The selected siRNAs targeting 12 phosphatases were rescreened and showed significant growth inhibition on both RH30 and CW9019 cells (Fig. 2A). Similarly, the siRNA silencing of 16 selected kinases inhibited the growth of all three RMS cell lines, RH30, CW9019, and RD (Fig. 2B). The results indicate a broad activity of these target genes on RMS, and further validate the screening results. It is noteworthy that inhibiting PLK1 consistently proved to have the greatest impact on growth suppression.

Figure 2.

siRNA gene silencing of selected phosphatases and kinases which were identified in primary screens significantly inhibited the growth of additional aRMS and eRMS cell lines. A, Growth inhibition of two aRMS cell lines, RH30 and CW9019, by 12 phosphatase-directed siRNAs. B, Growth inhibition of two aRMS cell lines, RH30 and CW9019, and an eRMS cell line, RD, by 16 kinase-directed siRNAs. Data are average of two independent tests for each cell line.

Silencing PLK1 Induces Significant Growth Inhibition and Apoptosis of Pediatric Cancer Cell Lines

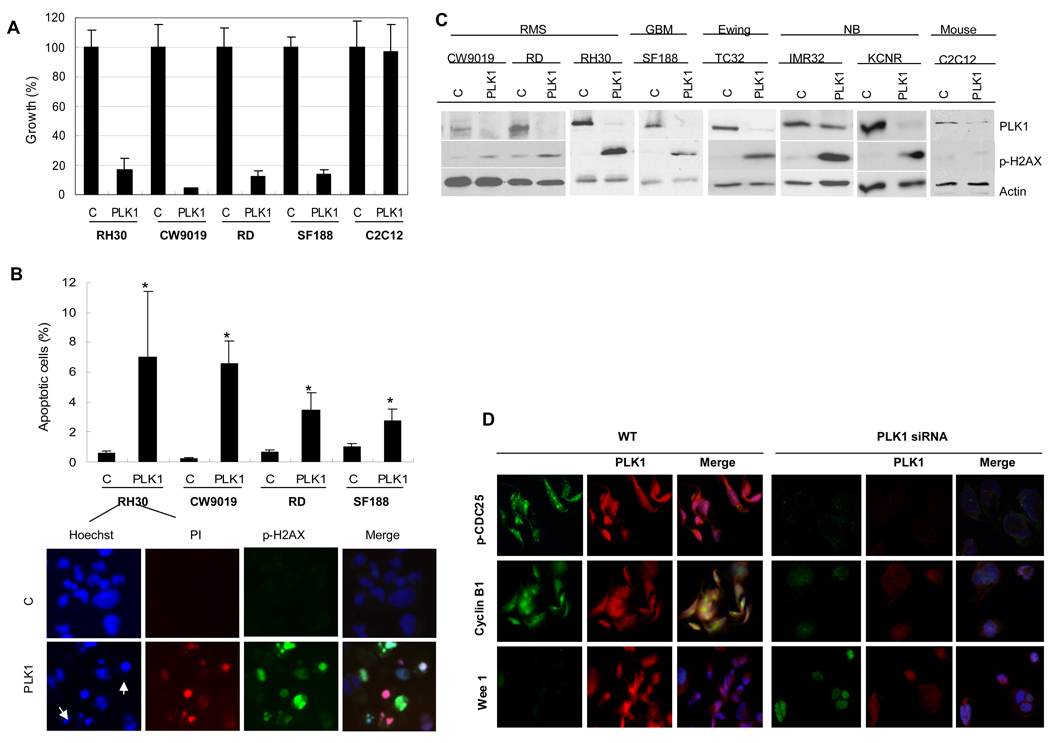

In order to validate PLK1 as a potential target, its expression was evaluated in the RMS cell lines, RH30, CW9019 and RD, and a human pediatric glioblastoma multiforme cell line, SF188, by immunofluorescence and Western blotting. PLK1 was readily detectable in each of these cell lines and was exclusively found in the nucleus (supplementary Fig. S1). Silencing PLK1 by siRNA caused more than 80% growth reduction in these four cell lines but not in a mouse myoblast cell line, C2C12 (Fig. 3A). Evidence for the induction of apoptosis following the loss of PLK1 was independently confirmed using cell-based immunofluorescence assays for p-H2AXS139 and PI uptake (Fig. 3B). The growth reduction correlates with the loss of PLK1 protein expression by immunoblotting and an induction of apoptosis as indicated by p-H2AX S139 (Fig. 3C). These findings were extended to models representing pediatric Ewing’s sarcoma (TC32), glioblastoma (SF188) and neuroblastoma (IMR32 and KCNR) where silencing PLK1 markedly induced apoptosis based on the induction of p-H2AXS139 (Fig. 3C). Furthermore, we confirmed that silencing PLK1 leads to the induction of apoptosis given the observed activation of caspase 3 and PARP cleavage (supplementary Fig. S2). In contrast, silencing PLK1 in non-tumor mouse myoblast C2C12 cells did not induce apoptosis (Fig. 3C and supplementary Fig. S2). To explain how the loss of PLK1 leads to growth inhibition and the induction of apoptosis we report that silencing PLK1 caused decreased levels of p-CDC25C and cyclin B1. There was also an increase in the cell cycle arresting protein WEE 1 (Fig. 3D).

Figure 3.

Growth inhibition and apoptosis induced by PLK1 siRNA treatment in different pediatric cancer cell lines. A, Percentage of growth of cell lines following PLK1 treatment (PLK1) compared to mock treated cells (C). Data are mean ± SD. B, Percentage of apoptotic cells of RH30, CW9019, RD and SF188 cells after PLK1 siRNA treatments as well as the apoptotic nuclear morphology of RH30 revealed by immunofluorescence. Apoptosis is based on PI-positive cells analyzed by the HCS system (p < 0.05, Student’s t-test). For apoptotic nuclear morphology, the top panel shows control samples and the bottom panel shows PLK1 siRNA treated samples. Arrows indicate nuclear condensation or fragmentation. C, Immunoblotting of PLK1 and p-H2AX S139 in different pediatric cancer cell lines, showing the decrease of PLK1 and the increase of p-H2AX S139 levels in PLK1 siRNA treated samples (PLK1) compared to the controls (C). Note that p-H2AX S139 in mouse muscle C2C12 cells did not increase after treatment. RMS: rhabdomyosarcomas; GBM: pediatric glioblastoma multiforme; Ewing: Ewing’s sarcoma; NB: neuroblastoma. D, Mechanism of growth inhibition of RMS (RH30) by silencing PLK1. Note that the cells after PLK1 knockdown (PLK1 siRNA) express lower levels of p-CDC25C and cyclin B1. There was also increase in the cell cycle inhibitor WEE 1 in contrast to the control (WT).

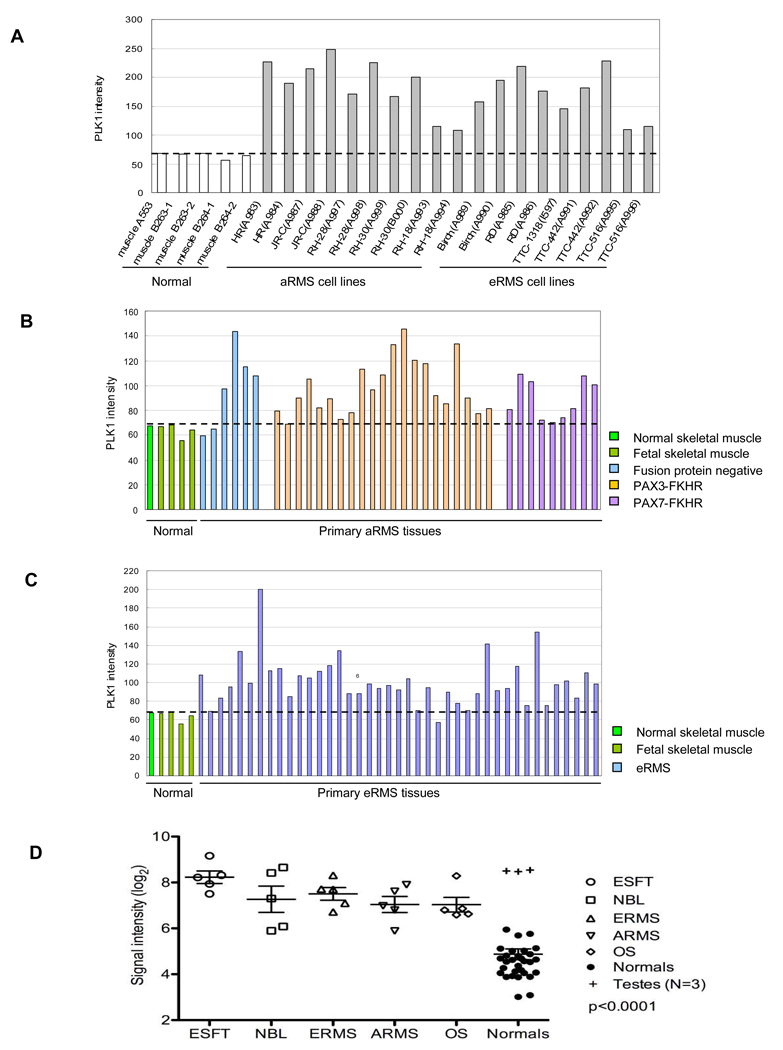

PLK1 Is Over-expressed in 10/10 RMS Cell Lines and in ~50% of Primary RMS Tumors

Gene expression microarray analysis revealed that PLK1 was highly expressed in all ten RMS cell lines examined compared with normal (5 yrs old) or fetal skeletal muscle cells (Fig. 4A). Moreover, PLK1 was present in all primary tumor samples and it was over-expressed (>1.5 fold increase compared to normal tissue) in 47% and 51% of primary aRMS (17/36 samples) and eRMS (21/41 samples) tumors (Fig. 4B and C; supplementary Table S1) based on gene expression analysis. The over-expression of PLK1 applies to subtypes of aRMS regardless of whether or not they express PAX-FKHR fusion proteins. Specifically, PLK1 was over-expressed in 67% (4/6 cases) of tumors where neither PAX3/FKHR nor PAX7-FKHR were detected. Similarly, 43%, (9/21 cases) of PAX3-FKHR positive tumors and 44% (4/9 cases) of PAX7-FKHR positive tumors over-expressed PLK1. Thus, PLK1 is commonly expressed in primary RMS and an excellent candidate for targeted therapy.

Figure 4.

Expression of PLK1 mRNA in normal skeletal muscle samples, RMS cell lines, primary tumor biopsies of pediatric RMS, Ewing’s sarcomas, osteosarcoma and neuroblastoma as revealed using cDNA microarrays. A, PLK1 over-expression in ten RMS cell lines. B, PLK1 expression in primary aRMS tumor biopsies. C, PLK1 expression in primary eRMS tumor biopsies. D, PLK1 expression in primary tumor biopsies of Ewing’s sarcoma (ESFT), neuroblastoma (NBL) and osteosarcoma (OS) in comparison to RMS (ERMS and ARMS) and normal tissues.

PLK1 Is Over-expressed in Primary Tumors of Pediatric Ewing’s Sarcoma, Neuroblastoma and Osteosarcoma

When PLK1 expression in primary pediatric tumors of RMS, Ewing’s sarcoma, neuroblastoma and Osteosarcoma were compared together in the same study, it was found that all four groups had significantly (p < 0.001) higher levels of PLK1 than normal tissues from breast, cerebellum, heart, kidney, liver, muscle, pancreas, prostate, spleen and thyroid (Fig. 4D). The results support our earlier findings in RMS and expanded the potential application of PLK1 in more pediatric cancers.

Discussion

Recently several studies have described the in vivo gene expression profiles of RMS, with the aim of associating specific genes that distinguish subtypes of RMS either for tumor diagnosis or for tumorigenesis (4, 6, 12–18, 30). Our study represents the first attempt to identify novel therapeutic targets by directly measuring the inhibitory effect of siRNA libraries on the growth of RMS cells. As a result, we have identified 16 phosphatases and 50 kinases that play significant roles in the growth control of RMS cells. Some of these genes are implicated in RMS cells for the first time while others have previously been linked to this disease, including CDK4, PDGFRA, PRKCD, PRKCQ, SKP2, etc. (Table 2) (4, 22, 25, 31). Overall these examples illustrate the power of using an unbiased genome-wide screening strategy to identify novel targets, particularly when the results confirm more traditional candidate gene approaches. The screening results further advance our understanding of the growth control of RMS cells. In addition, some of these active genes are known to be present in primary tumor samples and are considered important in the tumorigenesis of RMS and perhaps growth control. Together this indicated a promising avenue for the advancement of targeted therapies for this recalcitrant disease.

Several cell signaling pathways have been suggested for RMS tumors for their involvement in anti-apoptosis, tumor progression and growth (19). In particular, PDK-1/AKT, IGF-2/AKT or ERK, PI3K/AKT, mTOR/Hif-1α/VEGF and STAT3 pathways have been implicated in RMS (19, 24–25, 31–35). Consistent with this, we show by IPA analysis that a majority of the active kinases are associated directly or indirectly with MAP/PI3K/Jnk pathways, and that these pathways lead to the downstream activation of PLK1 that is one of the most important “survival kinases” for RMS identified in the screen. Such information is crucial in understanding RMS in a large context and in designing therapeutic strategies accordingly, as the combined therapy of several key targets may lead to better outcomes of the treatment.

Drug discovery efforts have already been initiated against cell cycle related kinases, such as cyclin-dependent kinases (CDK), Aurora and Polo-like kinase families. These cell cycle protein kinases play critical roles in mitotic entry and chromosome segregation and are often over-expressed in a variety of cancers (36). Inhibition of these proteins frequently results in mitotic arrest and subsequently apoptosis. Therefore, it is not surprising that a large number of the active kinases identified in this study, in particular, PLK1, AUKRB and CDK4, are in the functional groups related to cell cycle, cell death or apoptosis. The pharmacologic inhibition of these cell cycle protein kinases may represent a useful therapeutic strategy to control tumor growth and possibly promote myogenic differentiation in RMS (22). Clinical trials addressing the efficacy of PLK have recently begun for the treatment of adult cancers (37, 38), and therefore similar approaches may be taken to improve the treatment of pediatric RMS.

PLK1 is perhaps the best characterized member of the human Polo-like family. It acts in both mitotic entry and progression, and plays a key role in cell cycle checkpoint recovery after DNA damage (38). PLK1 is over-expressed in a variety of cancers, such as lung, breast, ovarian and prostate cancers (36), and often correlated with poor patient prognosis (38). Numerous studies have now established that PLK1 is a prime target for drug development in proliferative diseases such as cancers (36, 38, 39). However, its significance in childhood cancers has not been reported. PLK1 was identified in our study as one of the most important survival kinases for RMS cells in vitro since silencing it resulted in the greatest degree of growth inhibition compared to the other kinases and phosphatases tested. It was also found to be over-expressed in 49% of primary RMS tumors (n= 77) in this study. Our data also indicates that normal skeletal muscle may not require PLK1 while cancer cells do. This is in direct support of the studies that show PLK1 depletion induced apoptosis in cancer cells, while normal cells could survive (40, 41). It has been suggested that the loss of PLK1 in primary cells may be compensated by backup kinases and thus is less sensitive to PLK1 depletion (41). In our study, silencing PLK1 in the RH30 cancer cell line led to decreased protein levels of p-CDC25C and cyclin B1, both of which are direct targets of this kinase (42, 43). Conversely, there was an increase in WEE 1, the cell cycle inhibitor. These results indicate that the significant growth inhibition of PLK1 silencing on RMS cells is likely attributable to cell cycle arrest at G2/M, followed by apoptosis, as is the case in other cancer cell types (41, 44, 45). In addition, there are reports that PLK1 is involved in the inhibition of the mitochondrial-mediated apoptosis pathway by maintaining the stability of anti-apoptotic proteins such as survivin, Bcl-2 and Mcl-1 (46). Several studies have shown that induction of apoptosis after PLK1 depletion is independent of the p53 pathway. However, this issue remains somewhat controversial (41, 45, 47). The RMS cell lines used in this study express mutant p53 (48, 49), indicating that its status may not be a determinant of sensitivity to PLK1 depletion. Further study is necessary to clarify the apoptotic pathway.

Similar to PLK1, the knock down of several phosphatases and kinases such as PPP1R12C, SKIP, PRKCD, AURKB and PFTK1 also resulted in significant inhibition of RMS cell lines, and are candidates for further evaluation. Also, for some siRNAs in the libraries, the two siRNA duplexes targeting the same gene showed significant differences in their growth inhibition activity (data not shown). They were not considered further in this study, but deserve future investigation. In addition, it is noted that some of the active genes identified in this study were reported to be down regulated in a few gene profiling studies (16, 17, 19, 22), although silencing them by siRNA caused significant in vitro growth inhibition. The essential roles of theses genes under in vitro condition may reflect a difference of expression and importance of the genes from that under in vivo conditions. There are also conflicting reports of the gene expression status (15–17, 19, 22, 31). Future exploration of these potential therapeutic candidates should be accompanied by confirmation of their in vivo status.

In conclusion, we used a genome-wide rather than candidate approach to search for novel molecular targets for RMS. By screening the siRNA libraries of human phosphatases and kinases, we have identified 16 phosphatases and 50 kinases that play significant roles in the growth control and survival of RMS cells. In particular, PLK1 is one of the most important survival kinases for RMS. Silencing it by siRNA caused significant growth inhibition and apoptosis in vitro. More importantly, it is over-expressed in about half of the RMS primary tumor biopsies examined regardless of their molecular subtype, and thus holds great promise to be a therapeutic target for RMS. The same is true for other types of pediatric Ewing’s sarcoma, osteosarcoma, neuroblastoma and brain tumors such as glioblastoma multiforme. A recent study reported that PLK1 was an excellent molecular target for the treatment of leukemias and may have important implications for improving the treatment of pediatric hematological malignancies (50). Further studies on PLK1 and other identified genes may lead to better and safer therapeutic strategies for RMS and other pediatric cancers.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Fig. S2 PLK1 silencing by siRNA cause apoptosis on RMS cell lines. RMS (RH30 and RD) and mouse myoblast (C2C12) were treated with 5nM PLK1 siRNA for 72h. Proteins were subject to Western blotting. C: control; PLK1: siRNA treatment.

Supplementary Fig. S1 PLK1 protein expression in RMS cell lines (RH30, CW9019 and RD) as well as the glioblastoma multiforme cells (SF188) based on immunofluorescence. PLK1 protein is readily detectable in each of these cell lines. Moreover, PLK1 predominantly localized to the nucleus. The images are representatives of five view fields for each cell line.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Jennifer Law, Jing Wang and Betty Schaub for technical assistance as well as the CHLA Tumor Bank and Dept of Pathology staff for provision of tumor samples.

Grant support: British Columbia Children’s Hospital Pediatric Oncology Collaborative Research Fund provided funding to support this project (S.E. Dunn and C.J. Pallen). The Michael Cuccione Foundation Research Fellowship also provided salary support (C. Lee). S.E. Dunn and C.J. Pallen are recipients of Investigator Awards from the Child and Family Research Institute. Drs. Triche and Lawlor were supported by NIH SPECS grant 1U01CA11475-04.

List of abbreviations

- RMS

rhabdomyosarcoma

- aRMS

alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma

- eRMS

embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma

- HCS

high content screening

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- IPA

Ingenuity Pathway Analysis

- PI

propidium iodide

- GBM

glioblastoma multiforme

- NB

neuroblastoma

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Paulino AC, Okcu MF. Rhabdomyosarcoma. Current Probl Cancer. 2008;32:7–34. doi: 10.1016/j.currproblcancer.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Merlino G, Helman LJ. Rhabdomyosarcoma-working out the pathways. Oncogene. 1999;18:5340–5348. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pappo AS, Shapiro DN, Crist WM, Maurer HM. Biology and therapy of pediatric rhabdomyosarcoma. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:2123–2139. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.8.2123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davicioni E, Finckenstein FG, Shahbazian V, et al. Identification of a PAX-FKHR gene expression signature that defines molecular classes and determines the prognosis of alveolar rhabdomyosarcomas. Cancer Res. 2006;66:6936–6946. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kurmasheva RT, Houghton PJ. Pediatric Oncology. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2007;11:424–432. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2007.05.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blandford MC, Barr FC, Lynch JC, et al. Rhabdomyosarcomas Utilize Developmental, Myogenic Growth Factors for Disease Advantage: A Report From the Children’s Oncology Group. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2006;46:329–338. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Melcon SG, de Toledo Codina JS. Molecular biology of rhabdomyosarcoma. Clin Trans Oncol. 2007;9:415–419. doi: 10.1007/s12094-007-0079-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scrable HJ, Witte DP, Lampkin BC, Cavenee WK. Chromosomal localization of the human rhabdomyosarcoma locus by mitotic recombination mapping. Nature. 1987;329:645–647. doi: 10.1038/329645a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barr FG. Molecular genetics and pathogenesis of rhabdomyosarcoma. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2001;19:483–491. doi: 10.1097/00043426-199711000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bennicelli JL, Fredericks WJ, Wilson RB, et al. Wild-type PAX3 protein and the PAX3-FKHR fusion protein of alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma contain potent, structurally distinct transcriptional activation domains. Oncogene. 1995;11:119–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fredericks WJ, Galili N, Mukhopadhyay S, et al. The PAX3-FKHR fusion protein created by the t(2;13) translocation in alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma is a more potent transcriptional activator than PAX3. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:1522–1535. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.3.1522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khan J, Wei JS, Ringner M, et al. Classification and diagnostic prediction of cancers using gene expression profiling and artificial neural networks. Nat Med. 2001;7:673–679. doi: 10.1038/89044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baer C, Nees M, Breit S, et al. Profiling and functional annotation of mRNA gene expression in pediatric rhabdomyosarcoma and Ewing's sarcoma. Int J Cancer. 2004;110:687–694. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wachtel M, Dettling M, Koscielniak E, et al. Gene expression signatures identify rhabdomyosarcoma subtypes and detect a novel t(2;2)(q35;p23) translocation fusing PAX3 to NCOA1. Cancer Res. 2004;64:5539–5545. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Pittà C, Tombolan L, Albiero G, et al. Gene expression profiling identifies potential relevant genes in alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma pathogenesis and discriminates PAX3-FKHR positive and negative tumors. Int J Cancer. 2005;118:2772–2781. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schaaf GJ, Ruijter JM, van Ruissen F, et al. Full transcriptome analysis of rhabdomyosarcoma, normal, and fetal skeletal muscle: statistical comparison of multiple SAGE libraries. FASEB J. 2005;19:404–406. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2104fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldstein M, Meller I, Issakov J, Orr-Urtreger A. Novel Genes Implicated in Embryonal, Alveolar, and Pleomorphic Rhabdomyosarcoma: A Cytogenetic and Molecular Analysis of Primary Tumors. Neoplasia. 2006;8:332–343. doi: 10.1593/neo.05829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ebauer M, Wachtel M, Niggli FK, Schafer BW. Comparative expression profiling identifies an in vivo target gene signature with TFAP2B as a mediator of the survival function of PAX3/FKHR. Oncogene. 2007;26:7267–7281. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Romualdi C, De Pittà C, Tombolan L, et al. Defining the gene expression signature of rhabdomyosarcoma by meta-analysis. BMC Genomics. 2006;7:287–303. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-7-287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ren YX, Finckenstein FG, Abdueva DA, et al. Mouse mesenchymal stem cells expressing FAX-FKHR form alveolar rhabdomyosarcomas by cooperating with secondary mutations. Cancer Res. 2008;68:6587–6597. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.MacKeigan JP, Murphy LO, Blenis J. Sensitized RNAi screen of human kinases and phosphatases identifies new regulators of apoptosis and chemoresistance. Nature Cell Biol. 2005;7:591–600. doi: 10.1038/ncb1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saab R, Bills JL, Miceli AP, et al. Pharmacologic inhibition of cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 activity arrests proliferation in myoblasts and rhabdomyosarcoma-derived cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5:1299–1308. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Amstutz R, Wachtel M, Troxler H, et al. Phosphorylation regulates transcriptional activity of PAX3/FKHR and reveals novel therapeutic possibilities. Cancer Res. 2008;68:3767–3776. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cao L, Yu Y, Darko I, et al. Addiction of elevated insulin-like growth factor I receptor and initial modulation of the AKT pathway define the responsiveness of rhabdomyosarcoma to the targeting antibody. Cancer Res. 2008;68:8039–8048. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cen L, Arnoczky KJ, Hsieh FC, et al. Phosphorylation profiles of protein kinases in alveolar and embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma. Mod Pathol (Epub) 2007;20:936–946. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.To K, Zhao Y, Jiang H, et al. The phosphoinositide-dependent kinase-1 inhibitor, OSU-03012, prevents Y-box binding protein-1 (YB-1) from inducing epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) Mol Pharmacol. 2007;72:641–652. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.036111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee C, Dhillon J, Wang MY, et al. Targeting YB-1 in HER-2 overexpressing breast cancer cells induces apoptosis via the mTOR/STAT3 pathway and suppresses tumor growth in mice. Cancer Res. 2008;68:8661–8666. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Newton WA, Jr, Gehan EA, Webber BL, et al. Classification of rhabdomyosarcomas and related sarcomas. Pathologic aspects and proposal for a new classification-an intergroup rhabdomyosarcoma study. Cancer. 1995;76:1073–1085. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19950915)76:6<1073::aid-cncr2820760624>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Santos ND, Habibi G, Wang M, et al. Urokinase-type Plasminogen Activator (uPA) is Inhibited with QLT0267 a Small Molecule Targeting Integrin-linked Kinase (ILK) Translational Oncogenomics. 2007;2:67–79. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Davicioni E, Anderson MJ, Finckenstein FG, et al. Molecular classification of rhabdomyosarcoma--genotypic and phenotypic determinants of diagnosis: a report from the Children's Oncology Group. Am J Pathol. 2009;174:550–564. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taniguchi E, Nishijo K, McCleish AT, et al. PDGFR-A is a therapeutic target in alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma. Oncogene. 2008;27:6550–6560. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wan X, Shen N, Mendoza A, Khanna C, Helman LJ. CCI-779 Inhibits Rhabdomyosarcoma Xenograft Growth by an Antiangiogenic Mechanism Linked to the Targeting of mTOR/Hif-1α/VEGF Signaling. Neoplasia. 2006;8:394–401. doi: 10.1593/neo.05820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen CL, Loy A, Cen L, et al. Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 is involved in cell growth and survival of human rhabdomyosarcoma and osteosarcoma cells. BMC Cancer. 2007;7:111–120. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-7-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Petricoin EF, Espina V, Araujo RP, et al. Phosphoprotein pathway mapping: Akt/mammalian target of rapamycin activation is negatively associated with childhood rhabdomyosarcoma survival. Cancer Res. 2007;67:3431–3440. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Elia U, Flescher E. PI3K/Akt Pathway Activation Attenuates the Cytotoxic Effect of Methyl Jasmonate Toward Sarcoma Cells. Neoplasia. 2008;10:1303–1313. doi: 10.1593/neo.08636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Strebhardt K, Ullrich A. Targeting polo-like kinase 1 for cancer therapy. Nature Reviews/Cancer. 2006;6:321–330. doi: 10.1038/nrc1841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Perez de Castro I, de Carcer G, Malumbres A census of mitotic cancer genes: new insight into tumor cell biology and cancer therapy. Carcionogenesis. 2007;28:899–912. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Perez de Castro I, de Carcer1 G, Montoya G, Malumbres M. Emerging cancer therapeutic opportunities by inhibiting mitotic kinases. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2008;8:375–383. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2008.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reindl W, Yuna J, Kramer A, Strebhardt K, Berg T. Inhibition of polo-like kinase 1 by blocking polo-box domain-dependent protein-protein interactions. Chem. Biol. 2008;15:459–466. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2008.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu X, Erikson R. Polo-like kinase (Plk)1 depeletion induces apoptosis in cancer cells. PNAS. 2003;100:5789–5794. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1031523100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu X, Lei M, Erikson R. Normal cells, but not cancer cells, survive severe Plk1 depletion. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:2093–2108. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.6.2093-2108.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Toyoshima-Morimoto F, Taniguchi E, Nishida E. Plk1 promotes nuclear translocation of human Cdc25C during prophase. EMBO reports. 2002;3:341–348. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvf069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Toyoshima-Morimoto F, Taniguchi E, Shinya N, Iwamatsu A, Nishida E. Polo-like kinase 1 phosphorylates cyclin B1 and targets it to the nucleus during prophase. Nature. 2001;410:215–220. doi: 10.1038/35065617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Reagan-Shaw S, Ahmad N. Silencing of Polo-like kinase (Plk) 1 via siRNA causes induction of apoptosis and impairment of mitosis machinery in human prostate cancer cells: implications for the treatment of prostate cancer. The FASEB J. 2005;19:611–613. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2910fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bu Y, Yang Z, Li Q, Song F. Silencing of polo-like (Plk) 1 via siRNA causes inhibition of growth and induction of apoptosis in human esophageal cancer cells. Oncol. 2008;74:198–206. doi: 10.1159/000151367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Feng Y, Lin D, Shi Z, et al. Overexpression of PLK1 is associated with poor survival by inhibiting apoptosis via enhancement of survivin level in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2009;124:578–588. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Olmos D, Swanton C, de Bono J. Targeting polo-like kinase: learning too little and too late? J Clinical Oncol. 2008;26:5497–5499. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.6585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Taylor A, Shu L, Danks M, et al. p53 mutation and MDM2 amplification frequency in pediatric rhabdomyosarcoma tumors and cell lines. Medical and Pediatric Oncol. 2000;35:96–103. doi: 10.1002/1096-911x(200008)35:2<96::aid-mpo2>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Caldas H, Holloway MP, Hall BM, Qualman SJ, Altura RA. Survivin-directed RNA interference cocktail is a potent suppressor of tumour growth in vivo. J Med Genet. 2006;43:119–128. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2005.034686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ikezoe T, Yang J, Nishioka C, et al. A novel treatment strategy targeting polo-like kinase 1 in hematological malignancies. Leukemia. 2009:1–13. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Fig. S2 PLK1 silencing by siRNA cause apoptosis on RMS cell lines. RMS (RH30 and RD) and mouse myoblast (C2C12) were treated with 5nM PLK1 siRNA for 72h. Proteins were subject to Western blotting. C: control; PLK1: siRNA treatment.

Supplementary Fig. S1 PLK1 protein expression in RMS cell lines (RH30, CW9019 and RD) as well as the glioblastoma multiforme cells (SF188) based on immunofluorescence. PLK1 protein is readily detectable in each of these cell lines. Moreover, PLK1 predominantly localized to the nucleus. The images are representatives of five view fields for each cell line.