Abstract

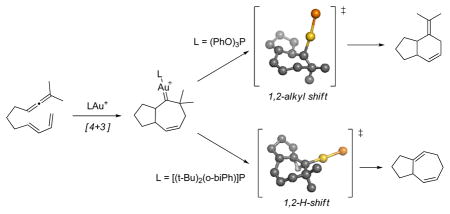

It is shown that [4+3] and [4+2] cycloaddition pathways are accessible in the Au(I) catalysis of allene-dienes. Seven-membered ring gold-stabilized carbenes, originating from the [4+3] cycloaddition process, are unstable and can rearrange via a 1,2-H or a 1,2-alkyl shift to yield six- and seven-membered products. Both steric and electronic properties of the AuL+ catalyst affect the electronic structure of the intermediate gold-stabilized carbene and its subsequent reactivity.

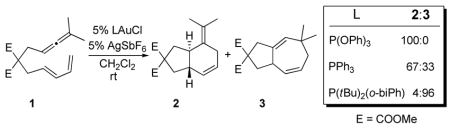

Cycloisomerization and cycloaddition reactions catalyzed by cationic gold(I) complexes have been employed effectively to install high degrees of structural complexity under mild conditions.1 Many of these reactions are proposed to proceed via cationic intermediates which, depending on the reaction, display reactivity reminiscent of gold-stabilized carbenes2 or carbocations.3 This dichotomy is highlighted by the striking differences between the gold-catalyzed intermolecular reaction of allenes-alkenes and allene-dienes: the former generally provided the [2+2]-cycloadduct,4 while the corresponding reaction with dienes allowed for ligand-dependant access to either the 6 or 7-membered ring products (Eq 1).5 Moreover, evidence was accumulated in support of a stepwise, cationic mechanism in the [2+2]-cycloaddition, which contrasted dramatically with the experimental support for concerted [4+2] and [4+3]-cycloadditions. In order to elucidate the factors dictating the reaction pathways, we performed a quantum mechanical study using the M06 flavor6 of density functional theory (DFT). In doing so, we hoped to gain insight into, not only the mechanism of the [4+2] and [4+3] cycloaddition reactions, but also the nature of the Au-C bond in these cationic intermediates and the factors governing their reactivity.

|

(1) |

The accuracy of our computational method [M06/LACV3P++**(2f)] was validated against relative binding data for [IPrAu]+ to isobutylene and propene. Geometry optimizations were performed using the M06 functional and the LACVP** basis set. Electronic energies were obtained from single point calculations using the LACV3P++**(2f) basis set, which includes a double-ζ f-type polarization function on gold. All other atoms used the 6–311++G** (see S. I. for more details). The M06 analytic Hessian was used to obtain vibrational thermodynamic corrections (ZPE, Hvib, Svib). We calculated a binding free energy difference ΔG= 1.0 kcal/mol in CH2Cl2 at − 60 °C, which is in excellent agreement with ΔG= 0.97 kcal/mol from 1H-NMR experiments.7

First, we located a transition structure for the uncatalyzed concerted [4+2]-cycloaddition process with a barrier of ΔG‡= 31.1 kcal/mol (Figure 1). Not surprisingly, we were unable to locate a transition state for the uncatalyzed [4+3]. We next turned our attention to the Au(I)-catalyzed reaction using PMe3 as a ligand. Me3PAu+ coordinates to the allene, followed by formation of Au-stabilized allylic cation8 4 with an activation free energy barrier (TS14) of ΔG‡= 6.8 kcal/mol (Scheme 1). Intermediate 4 undergoes a concerted9 [4+3] cycloaddition via rate-limiting TS4510 at 14.6 kcal/mol (for L=PMe3) leading to intermediate 5.

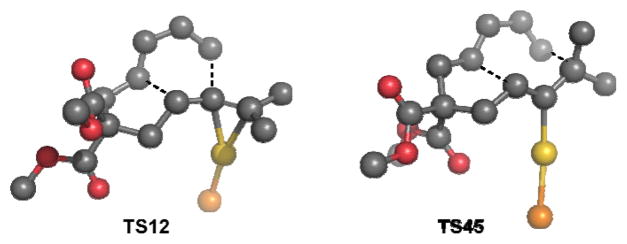

Figure 1.

Calculated transition state structures (L = PMe3) for the concerted [4+2]- and [4+3]-cycloaddition reaction of dienes and gold-complexed allenes.

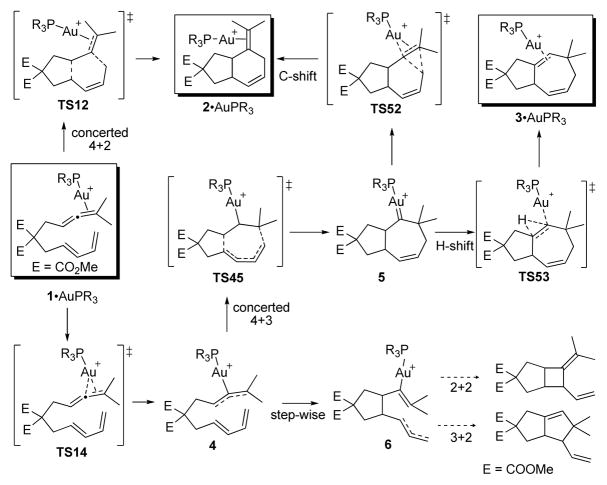

Scheme 1.

Au-catalyzed [4+3] and [4+2]-cycloadditions.

Our results suggest that intermediate 5 is a key bifurcation point in the pathways leading to the formation of six- and seven-membered ring products 2 and 3 via a 1,2-alkyl shift (TS52) or via a 1,2-hydrogen shift (TS53).11,12 We were able to locate a transition state (TS12) for the conversion of 1·AuPMe3 to 2·AuPMe3 by a direct [4+2]-cycloaddition; however, this process is 13.9 kcal/mol higher in energy than the rate-determining barrier for the pathway via intermediate 5.

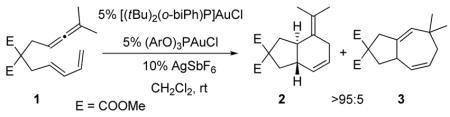

Having established the mechanism using PMe3, we calculated the relative energies for key intermediates and transition structures for catalysts bearing P(OPh)3, PPh3, and P(tBu)2(o-biPh). The phosphite ligand facilitates the [4+3] cycloaddition with respect to PMe3 and PPh3 (TS45·AuP(OPh)3 is 7.9 and 7.2 kcal mol−1 lower in energy than for PMe3 and PPh3 respectively). In contrast, [Au·P(tBu)2(o-biPh)]+ catalyzed reaction shows the highest activation barrier of 9.9 kcal/mol for the [4+3] cycloaddition (TS45). This difference in activation energy was confirmed by a catalyst competition experiment (5% (PhO)3PAuCl, 5% (tBu)2(o-biPh)PAuCl, 10% AgSbF6,, CH2Cl2, rt) that resulted in exclusive formation of 2 (eq. 2). In addition, [AuP(tBu)2(o-biPh)]+ activates the uncoordinated allenic double bond, promoting a highly asynchronous concerted [4+2] cycloaddition. Our results predict that when di-t-butylbiphenylphosphine is used as the ligand, the [4+2] cycloaddition pathway (TS12, 17.3 kcal/mol) becomes competitive with the [4+3] (TS45, 15.1 kcal/mol). Thus, our calculations suggest that a [4+2] pathway is responsible for the 4% (3% predicted) of six-membered ring product (2) observed experimentally when [AuP(tBu)2(o-biPh)]+ is used a catalyst.

In order to account for the differences in activation energy for the cycloaddition (TS45), we considered the effects that the different ligands have on the Au –C bond. We calculated snap-bond energies for [AuL]+ to C and find that the Au –C bond is much stronger for L=P(OPh)3 [92 kcal/mol in 5·AuP(OPh)3] than for P(tBu)2(o-biPh) [78 kcal/mol in 5·AuP(tBu)2(o-biPh)]. Indeed, the carbene intermediate is less stabilized by [AuP(tBu)2(o-biPh)]+, resulting in the observed higher energy for TS45 compared to the [AuP(OPh)3]+-catalyzed reaction. Based on natural bond orbital13 (NBO) analyses, we find that the gold-carbene bond is composed of weak σ and π-components. The σ-interaction originates from the C sp2 lone pair partially overlapping the 6s orbital on gold, which is partially populated by donation from L. In addition, the π-component of the bond is a highly polarized dπ to pπ donation from an Au lone pair to the empty pπ-orbital on C.14

|

(2) |

We next examined TS52 and TS53 (Figure 2) with different ligands in order to assess factors that might lead to a preference for 1,2-H or alkyl shift. In all cases, the 7-membered ring in 5 adopts a chair-like conformation. Consequently, this geometry is essentially conserved in transition structures TS52 for the alkyl shift. The 1,2-alkyl shift involves both σ and π character in the carbene. We envision that density from C2 σ-lone pair is shifted towards C3, contributing to the resulting double bond. In turn, C4 migrates with the C3 –C4 electron pair, which at the transition structure (TS52) forms an occupied pπ-orbital that overlaps with the empty pπ-orbital at C2. Thus, the alkyl shift is relatively insensitive to ligand effects and occurs with barriers of 6.1, 6.0 and 5.7 kcal/mol for [AuP(tBu)2(o-biPh)]+, [AuP(OPh)3]+, and [AuPPh3]+ respectively.

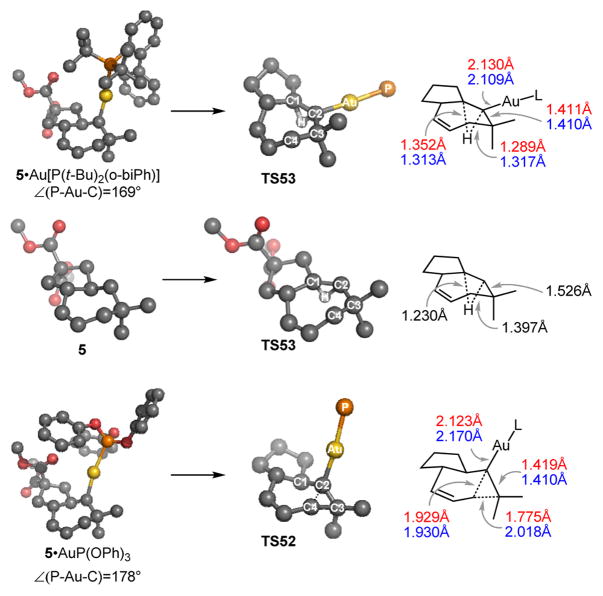

Figure 2.

Calculated structures for 5, TS53 (L= P(tBu)2(o-biPh) and metal-free), and TS52 (L=P(OPh)3). Selected bond lengths for TS53 and TS52 with L= P(tBu)2(o-biPh) and L=P(OPh)3 shown in red and blue, respectively. Selected bond lengths for 5 and TS53 for metal-free structures shown in black.

In contrast, our results suggest that the barrier for the 1,2-H shift is affected (and raised relative to the metal-free case) by increased population of the C pπ-orbital by donation from the Au dπ-electrons.15 The free carbene intermediate undergoes the 1,2-H shift with a barrier of 1.3 kcal/mol.16 This barrier increases to 6.9 kcal/mol for the [AuP(OPh)3]+-stabilized carbene. In contrast, with [AuP(tBu)2(o-biPh)]+ the barrier only increases to 2.6 kcal/mol indicating that Au dπ-electrons have less overlap with the C pπ-orbital in this transition state.

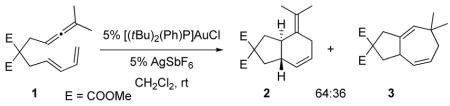

Based on previous theoretical and experimental analyses of dialkylbiaryl phosphines,17 we hypothesized that steric effects of the biaryl were responsible for this difference. The distal aryl causes a repulsive steric interaction with the gold atom and with the substrate. As a consequence, the P-Au-C angle in the complexes bearing the biarylphosphine ligand is ~169°. This geometric distortion reduces the Au-dπ to C-pπ overlap. In accord with this hypothesis, we calculate a C-Au-P angle of ~176° for [5·AuP(tBu)2Ph]+ and predict a 2:3 ratio of 67:33 for this intermediate, which we confirmed experimentally (eq 3).

|

(3) |

Our analysis of the gold-catalyzed [4+2]- and [4+3]-cycloaddition reactions finds that both reactions proceed through an initial concerted [4+3]-cycloaddition of a gold-activated allene with a diene. The selectivity for either pathway arises primarily from a preference for either 1,2-H or 1,2-alkyl shifts in the gold-stabilized carbene intermediate. We conclude that the impact of the gold catalyst on migratory aptitude is a consequence of the relative strength of the dπ to pπ interaction in the Au-C bond. Importantly, these results suggest that in addition to electronic propertes,14 the sterics of the ligand can dramatically impact Au-C bonding, especially in [AuP(tBu)2(o-biPh)]+-catalyzed reactions.

Supplementary Material

Table 1.

Free energies (ΔG, kcal/mol) relative to 1·X at 298 K.

| X | AuPMe3 | AuP(OPh)3 | AuPPh3 | AuP(tBu)2 (o-biPh) | metal-Free |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | 6.3 | −2.4 | 3.5 | 5.2 | – |

| TS45 | 12.4 | 4.5 | 11.7 | 15.1 | – |

| 5 | −6.8 | −10.7 | −9.8 | −10.1 | 26.6 |

| TS52 | −3.7 | −4.7 | −4.1 | −4.0 | – |

| TS53 | −2.8 | −3.8 | −3.8 | −7.5 | 27.9 |

| 2 | −38.7 | −39.2 | −36.2 | −34.9 | −34.7 |

| 3 | −40.2 | −41.2 | −38.6 | −38.5 | −38.5 |

| TS12 | 26.6 | 23.0 | 25.4 | 17.3 | 31.1 |

| Pred. 2:3 | 81:19 | 81:19 | 63:37 | 3:97 | – |

| Exp. 2:3 | – | 100:0 | 67:33 | 4:96 | – |

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge NIHGMS (RO1 GM073932), Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Novartis for funding, and Johnson Matthey for the generous donation of AuCl3. Facilities were funded by grants from ARO-DURIP and ONR-DURIP.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available. Supplied are XYZ coordinates. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.(a) Hashmi SK, Rudolph M. Chem Soc Rev. 2008;37:1766. doi: 10.1039/b615629k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Gorin DJ, Sherry BD, Toste FD. Chem Rev. 2008;108:3351. doi: 10.1021/cr068430g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Shen HC. Tetrahedron. 2008;64:7847. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prieto A, Fructos MR, Diaz-Requejo MM, Pérez PJ, Pérez-Galán P, Delpont N, Echavarren AM. Tetrahedron. 2009;65:1790. [Google Scholar]; (b) Fürstner A, Davies PW. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2007;46:3410. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Jiménez-Núñez E, Echavarren AM. Chem Rev. 2008;108:3326. doi: 10.1021/cr0684319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Shapiro ND, Toste FD. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:4160. doi: 10.1021/ja071231+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Correa A, Marion N, Fensterbank L, Malacria M, Nolan SP, Cavallo L. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2008;47:718. doi: 10.1002/anie.200703769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Johansson MJ, Gorin DJ, Staben ST, Toste FD. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:18002. doi: 10.1021/ja0552500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Shi X, Gorin DJ, Toste FD. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:5802. doi: 10.1021/ja051689g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Fürstner A, Morency L. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47:5030. doi: 10.1002/anie.200800934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Jiménez-Núñez E, Claverie CK, Bour C, Cárdenas DJ, Echavarren AM. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2008;47:7892. doi: 10.1002/anie.200803269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Toullec PY, Biarre T, Michelet V. Org Lett. 2009;11:2888. doi: 10.1021/ol900864n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Luzung MR, Mauleón P, Toste FD. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:12402. doi: 10.1021/ja075412n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mauleón P, Zeldin RM, Gonzalez AZ, Toste FD. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:6348. doi: 10.1021/ja901649s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Zhao Y, Truhlar DG. Theo Chem Acc. 2008;120:215. [Google Scholar]; (b) Zhao Y, Truhlar DG. Acc Chem Res. 2008;41:157. doi: 10.1021/ar700111a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown TJ, Dickens MG, Widenhoefer RA. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:6350. doi: 10.1021/ja9015827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Lee JH, Toste FD. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2007;46:912. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Gandon V, Lemiere G, Hours A, Fensterbank L, Malacria M. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47:7534. doi: 10.1002/anie.200802332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Mauleón P, Krinsky JL, Toste FD. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:4513. doi: 10.1021/ja900456m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.We were able to find stable intermediate 6, presumed to be on the path to step-wise 2+2 and 3+2 cycloaddition pathways. All attempts to locate a step-wise pathway leading to 2 and 3 led to concerted TS45.

- 10.In contrast, a related DFT study of Pt and Au-catalyzed [4+3]-cycloaddition suggests “a 1,2-hydride shift on the generated carbene intermediate as the rate-limiting step”. See: Trillo B, López F, Montserrat S, Castedo L, Lledós A, Mascareñas JL. Chem–Eur J. 2009;15:3336. doi: 10.1002/chem.200900164.

- 11.A stepwise mechanism was proposed for a similar reaction, see: Gung BW, Craft DT. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009;50:2685. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2008.07.155.

- 12.Trillo B, López F, Gulías M, Castedo L, Mascareñas JL. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47:951. doi: 10.1002/anie.200704566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reed AE, Curtiss LA, Weinhold F. Chem Rev. 1988;88:899. [Google Scholar]

- 14.(a) Benitez D, Shapiro ND, Tkatchouk E, Wang Y, Goddard WA, III, Toste FD. Nature Chem. 2009;1:482. doi: 10.1038/nchem.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Gorin DJ, Toste FD. Nature. 2007;446:395. doi: 10.1038/nature05592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Similar effects have been calculated for transition states for 1,2-H-shifts of singlet carbenes. See: Keating AE, Garcia-Garibay MA, Houk KN. J Phys Chem A. 1998;102:8467. and references therein.Albu TV, Lynch BJ, Truhlar DG, Goren AC, Hrovat DA, Borden WT, Moss RA. J Phys Chem A. 2002;106:5323.

- 16.We were unable to locate a transition state for the 1,2-alkyl shift of the free carbene.

- 17.(a) Barder TE, Buchwald SL. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:5096. doi: 10.1021/ja0683180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Herrero-Gómez E, Nieto-Oberhuber C, Lopez S, Benet-Buchholz J, Echavarren AM. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2006;45:5455. doi: 10.1002/anie.200601688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.