Abstract

This study draws data from the Family Life Project to examine parenting behaviors observed for 105 mothers and grandmothers raising an infant in rural low-income multigenerational households. Multilevel models are used to examine the relationships between maternal age and psychological distress and parenting of the infant by both generations. The findings indicate that young maternal age is a risk factor for less sensitive parenting in the presence of other risks, including psychological distress. Further, young maternal age is associated with negative parenting behaviors by grandmothers only. Grandmothers and mothers displayed similar levels of negative intrusive parenting, but different factors were linked to the observed parenting of each generation. These findings contribute to understanding the benefits and risks of three-generation households.

Keywords: adolescent mothers, grandparents, multigenerational, parenting, poor families, rural

Multigenerational households in which mothers and grandmothers raise children together are an increasingly common family structure. In 2006, almost 3.7 million children lived in households with grandparents and parents, with children under 6 years of age the most likely to live in three-generation households (U.S. Census Bureau, 2006). The rising prevalence of this family structure is linked to increases in female-headed households caused by out-of-wedlock births and divorce (George & Dickerson, 2000). Housing, employment, and educational limitations in nonurban environments may also directly or indirectly influence formation of multigenerational households. Despite this growing trend, there has been little systematic investigation of family relations in three-generation households (Foster & Kalil, 2007).

Extant research on multigenerational families has focused on adolescent mothers, who may comprise a particularly vulnerable group of parents. Much research in this area has also focused on African American families in low-income urban communities. The research base includes limited insight into family processes that influence parenting within these family structures (Black et al., 2002; Black & Nitz, 1996; Chase-Lansdale, Gordon, Coley, Wakschlag, & Brooks-Gunn, 1999; East & Felice, 1996; Jones, Zalot, Foster, Sterret, & Chester, 2007). Moreover, the grandmother perspective is often missing from research on multigenerational families, as little research has focused on grandmother-grandchild relationships (Caldwell, Antonucci, & Jackson, 1998; Goodman & Silverstein, 2002; Sadler & Clemmens, 2004). Parenting of mothers and grandmothers may be influenced by different factors and differentially related to child outcomes (Chase-Lansdale et al., 1999; Kalil, Spencer, Spieker, & Gilchrist, 1998; Schweingruber & Kalil, 2000). The present study addresses these research gaps by studying the relations between maternal age, psychological distress, and parenting by mothers and grandmothers in low-income three-generation households.

Consistent evidence indicates that economic disadvantage is associated with less positive parenting and more negative parenting, ranging from less sensitive and responsive parenting, harsher discipline, and the use of fewer child-oriented approaches (Bradley & Corwyn, 2002; Magnuson & Duncan, 2002; McLoyd, 1998). Many parents living in poverty, however, exhibit sensitive parenting behaviors. This positive parenting can serve as an important resource or protective factor for children facing the other risks associated with poverty (e.g., risky neighborhoods, failing schools). Identifying the processes through which poverty compromises parenting while simultaneously identifying the mechanisms that preserve effective parenting in the face of economic adversity are critical goals for researchers (Klein & Forehand, 2000; Magnuson & Duncan).

Psychological Distress And Parenting

Parental psychological distress represents one pathway through which economic disadvantage may compromise parenting (Magnuson & Duncan, 2002; McLoyd, 1998; Petterson & Albers, 2001). Low-income parents face elevated risks for psychological distress, including depression, and parental depression may be most harmful for low-income children, given the constellation of other risks these families face (Magnuson & Duncan; Petterson & Albers). The research linking psychological distress to parenting among economically disadvantaged families has focused on mothers. Research on adolescent mothers indicates that they are more likely to experience depressive symptoms than older mothers, even when controlling for socioeconomic status (Caldwell et al., 1998; Schweingruber & Kalil, 2000). Grandmothers who are primary caregivers and those who are caregivers in three-generation households generally face elevated risks to physical and mental health in comparison to less-involved nonresidential grandmothers (Caputo, 2000; Hayslip & Kaminski, 2005). Although psychological distress has been studied separately in adolescent mothers and grandmothers, little research has addressed these issues with explicit consideration of three-generation households. Moreover, the associations between grandmother psychological distress and interactions with the grandchild remain largely unexplored (Caldwell et al.; Sadler & Clemmens, 2004; Schweingruber & Kalil). Identifying moderators of the relationship between caregiver psychological distress and parenting is a key goal for researchers because those moderators may be targets for interventions.

Social Support

Social support is a critical moderator in the relationship between psychological distress and parenting practices (McLoyd, 1998; Murry, Bynum, Brody, Willert, & Stephens, 2001; Orthner, Jones-Sanpei, & Williamson, 2004). Social support may be especially important for parents living in poverty because they may face more stress and lack financial resources to purchase support (e.g., child care) (Brown, Brody, & Stoneman, 2000; Hashima & Amato, 1994; McLoyd, 1998; Orthner et al.). Adolescent mothers, and perhaps older mothers living in multigenerational households, may rely in particular on family support (Jones et al., 2007). Grandmother coresidence is not synonymous with grandmother support, and hence family social support and coresidence should be examined separately (Apfel & Seitz, 1996; Black & Nitz, 1996; Rosman & Yoshikawa, 2001). For adolescent mothers, family support can be an important buffer of negative parenting when mothers face other risks to parenting, including youth and psychological distress (Apfel & Seitz; Moore & Brooks-Gunn, 2002; Shapiro & Mangelsdorf, 1994). How social support operates within three-generation households remains unclear, however.

Few studies of multigenerational families have included grandmother perceptions of social support. In a rare exception, Sadler, Anderson, and Sabatelli (2001) report that grandmother, but not adolescent mother, self-reported perception of family support was positively related to maternal parenting competence. Grandmother parenting competence was not measured. The authors suggest that grandmothers who feel more supported are able to serve as more beneficial parenting resources for their children. Family social support may be especially relevant in the present sample because rural social support networks may be closely tied to kinship networks (Blalock, Tiller, & Monroe, 2004; Rural Appalachian Youth and Families Consortium, 1996).

Maternal Age

Studying parenting within multigenerational families requires accounting for the timing of family transitions and the interactions among life course trajectories of mothers and grandmothers (Burton, 1996; Elder, 1998). Extensive grandmother involvement may be associated with teenage motherhood, thus causing a disruption in normative expectations for the timing of motherhood and grandmotherhood and the normative tasks associated with adolescence and middle age. From a life course perspective, early grand-motherhood may exert adverse influences on grandmother mental health and, in turn, influence her interactions with the grandchild, as she may resent the “off time” event of grandparenthood, a life role transition she did not choose at a time when she expected to be entering middle age and becoming freer of child-care responsibilities (Burton, 1996; Burton & Bengston, 1985; See et al., 1998).

Grandmothers in multigenerational households may face considerable role overload, as they may be caring for their own young children and, among the predominantly single low-income grandmothers in the present sample, they may also be struggling to provide economic resources for the expanded family (Dallas, 2004; See at al., 1998). Qualitative interviews with young grandmothers of adolescent mothers reveal the conflict many grandmothers feel in dividing their time between grandchildren and children, and the stress of simultaneously parenting an infant, an adolescent, and children of other ages (Sadler & Clemmens, 2004).

Despite this inherent complexity of parenting that is embedded in the simultaneous transition to motherhood and grandmotherhood, much of the research on parenting in three-generation families ignores the importance of considering linked mother and grandmother lives by choosing to focus exclusively on the disadvantages stemming from adolescents parenting at a young age. Adolescent mothers have been shown to be less sensitive and responsive, less stimulating, and less warm than adult mothers (Berlin, Brady-Smith, & Brooks-Gunn, 2002; Coley & Chase-Lansdale, 1998; Moore & Brooks-Gunn, 2002). Within all adolescent samples, younger mothers are often less responsive than older teen mothers (Black & Nitz, 1996; Shapiro & Mangelsdorf, 1994). These conclusions regarding the disadvantages associated with early child-bearing, however, may in part stem from the lack of adequate comparison groups for teenage mothers (Berlin et al.; Coley & Chase-Lansdale; East & Felice, 1996; Moore & Brooks-Gunn). Adolescent mothers may be at risk for negative outcomes and parenting due to the same personal and environmental factors that placed them at risk for early pregnancy in the first place (Coley & Chase-Lansdale; Moore & Brooks-Gunn). Berlin and colleagues reported that negative maternal age effects on parenting in a sample of 1,702 low-income Early Head Start families were accounted for by sociodemo-graphic risk (education, income, English proficiency) for the Latina and White mothers. Sociodemographic risk reduced the strength of the relationship between maternal age and intrusive and less supportive parenting for African American mothers, but the main effect of age persisted, perhaps due to the uniformity of socioeconomic disadvantage and the younger mean age of the African American mothers (Berlin et al.).

As these findings suggest, maternal age itself may not always be related directly to parenting, as only in the presence of other risks to early parenting does age appear to confer a disadvantage. The lack of process-oriented research among adolescent mother families leads to lack of clarity regarding the contexts in which maternal age is linked to impaired parenting (East & Felice, 1996; Shapiro & Mangelsdorf, 1994). Particularly relevant to the current study, coresidence with the grandmother has been demonstrated to be related to positive parenting behaviors for young adolescent mothers in comparison to older adolescent mothers. Chase-Lansdale, Brooks-Gunn, and Zamsky (1994), for example, found that maternal age alone did not predict differences in parenting behaviors observed during a structured observation with 3-year-old children, but younger adolescents who lived with their mothers were more supportive and positive than younger adolescents living alone and older adolescents living with their mothers. The present study provides the opportunity to tease apart the influence of maternal age by including families with similar household structures (three generations), similar community and economic contexts (high poverty rural settings), and diverse maternal ages (adolescence through adulthood) and race or ethnicities (African American and European American).

Grandmother Parenting

Little research has explored grandparent-grandchild relationships in families in which grandmothers are highly involved caregivers (George & Dickerson, 1995; Lee, Ensminger, & LaVeist, 2005). Observational studies of grandparent-infant relationships and research attending to theory and processes shaping grandparent behaviors are missing from the literature. Research on grandmothers who are raising grandchildren, generally in households without the parent, focuses on grandmother mental and physical health, often to the exclusion of parenting behaviors by grandmothers (Goodman & Silverstein, 2002; Hayslip & Kaminski, 2005).

Including grandmother parenting in investigations of households in which grandmothers are functioning as coparents is crucial to understanding risk and protective factors in these households (Jones et al., 2007). Moreover, according to a recent analysis by Foster and Kalil (2007) of child outcomes in diverse household structures, there is considerable diversity within household type, such that future research should focus on delineating variations in family processes within household types rather than comparing child outcomes or processes across household types. Examining factors linked to mother and grandmother parenting in the same households represents an important contribution to this area of research.

Cultural Context

Much research on multigenerational households has focused on low-income African American families, perhaps because kinship care, and in particular grandmother involvement in childrearing, have long been seen as culturally accepted adaptive family forms to endure social and economic pressures. These networks, however, may entail additional burdens for families who are dispersing diminished psychological and economic resources among many family members (Garcia Coll, 1990; Hunter & Taylor, 1998; Murry et al., 2001; Pearson, Hunter, Ensminger, & Kellam, 1990). Unmarried ethnic minority mothers may rely extensively on extended kinship networks (Garcia Coll et al., 1996; Johnson, 2000; Jones et al., 2007). As a result, children are influenced by multiple adults and caregivers, such that studying family processes in these families may require complex models that move beyond mother-father or single-mother paradigms (Garcia Coll; Jones et al.; Murry et al.).

Evidence is emerging to suggest weaker relations between psychological distress and negative parenting among low-income African American mothers (Elder, Eccles, Ardelt, & Lord, 1995; Johnson, 2000; McLeod & Nonnemaker, 2000; McLoyd, Cauce, Takeuchi, & Wilson, 2000). It should be cautioned that these discrepancies could reflect the use of culturally inappropriate measures of psychological distress and parenting. Alternatively, these conclusions may reflect the omission of important sources of support for mothers and children that help buffer the influences of economic disadvantage (Jones et al., 2007; McLoyd et al.). Grandmothers may represent one of these key sources of support. This support for parents, however, may come at a cost to the grandmother's own well-being. In two separate studies of depressive symptoms among Black and White adolescent mother families, Caldwell and colleagues (1998) and Schweingruber and Kalil (2000) found that although levels of depression did not vary by race among mothers, Black grandmothers reported higher mean levels of depressive symptoms than White grandmothers. The implications of these findings for parenting behaviors remain unexplored. The present study presents an opportunity to examine directly processes that have been suggested to be critical to understanding parenting and child outcomes among economically disadvantaged African American families.

The Present Study

The sample for the present study is drawn from the Family Life Project, an investigation of family processes among economically disadvantaged families living in nonurban areas. Multigenerational families were not a target of the Family Life Project. In other studies, the mothers in the present investigation may have been classified as single mothers because they did not live with a romantic partner. This study presents an opportunity to study within-family processes by jointly considering the relationships between maternal age and psychological distress and parenting by coresident grandmothers and mothers.

The first goal of the present study was to addresses the relationship between maternal age and parenting. Hypothesis 1 suggested that maternal age would pose a risk to parenting by mothers only, such that younger maternal age would be associated with less sensitive and more negative intrusive parenting by mothers. The second goal was to examine the individual (perceived family social support) and family (maternal age, household composition, race or ethnicity) factors that may moderate the relationship between psychological distress and observed sensitive and negative intrusive parenting by mothers and grandmothers. Three specific hypotheses were formed. Hypothesis 2 proposed that perceived family social support would moderate the relationship between psychological distress and sensitivity and negative intrusiveness for mothers and grandmothers, such that psychological distress would only predict parenting in the presence of low levels of reported social support. Hypothesis 3 proposed that young maternal age in conjunction with higher levels of psychological distress would be related to less sensitive and more negative observed parenting behaviors. Finally, Hypothesis 4 proposed race or ethnicity as a moderator of the relationship between psychological distress and observed parenting behaviors, such that higher levels of psychological distress would be associated with lower levels of observed sensitivity and higher levels of negative intrusiveness for White families only. Each of these hypothesized moderating effects was expected to be consistent for mothers and grandmothers.

Method

Participants

The sample in the present study is a subset drawn from the Family Life Project (FLP), a longitudinal investigation of the ways in which child, family, and contextual characteristics in nonmetropolitan communities shape early child development. Families enrolled in the study reside in three counties in Eastern North Carolina and three counties in Central Pennsylvania selected to represent the Black South and Appalachia. The sample for the present study consists of families in which during the 6-month home visit mothers nominated the child's grandmother as the secondary caregiver, indicating that next to the mother, the grandmother was the household member most responsible for the child. Designation as a secondary caregiver required residence with the mother and infant in households without the infant's father or mother's romantic partner. All grandmothers nominated as secondary caregivers were maternal grandmothers. From the original 1,292 families, approximately 183 families met this requirement. To be included in the present analyses, both the mother and grandmother participated in the dyadic free play interaction with the infant at a 6-month visit, reducing the sample to 105 families. The 105 families included in the present analyses did not differ from the 183 families in the sample in terms of mean household composition, maternal age, grandmother age, or psychological distress. The subset of families who were not included in the present analyses, however, had on average lower income-to-needs ratios, a greater percentage of African American families, and a greater percentage of mothers and grandmothers with high school diplomas.

Approximately 64% of the sample was African American, 36% was White, and 75% of the sample resided in North Carolina. Mean maternal age was 21.2 (4.32), with approximately 25% of the mothers 18 or under and approximately 51% of the mothers in their 20s. Mean grandmother age was 46.96 (7.90). Approximately 70% of grandmothers and 45% of mothers reported working. Nearly 75% of grandmothers had earned at least a high school degree, 50% of mothers reported earning a high school diploma, and 47% reported current school enrollment. No caregivers reported receiving a 4-year college degree.

Recruitment

The FLP used a developmental epidemiological sampling design to recruit a representative sample of families with oversampling of low-income families in both states and African American families in North Carolina. Families were recruited in person at hospitals and over the phone using birth records. Eligibility criteria included residency in the target counties, English as the primary language spoken in the home, and plans to stay in the area for the next 3 years. A total of 1,292 families enrolled in the study by completing the first home visit when the infant was 2 months of age.

Procedure

Data for the present analyses were collected by two trained home visitors during two home visits that took place when children were on average 6 – 8 months of age. The first visit generally took place close to the child's 6-month birthday, and the second visit usually took place 2 to 4 weeks later. The mother and grandmother were filmed separately in a semistructured 10-min dyadic free play interaction with the infant. The dyadic free play interactions always took place on different days. The caregiver was given a standard set of toys, and she was instructed to play with the child as she normally would given free time during the day. A team of six coders scored the DVDs for caregiver behavior. All coders were blind to other information about the families, and different coders observed the mother-infant and grandmother-infant interactions for each family. Two criterion coders trained all other coders until excellent reliability (intraclass correlation > .80) was maintained for each coder on each scale. Once reliability was met, noncriterion coders coded in pairs, while continuing to code at least 20% of cases with a criterion coder. A random selection of approximately 30% of all interactions were double-coded. For those double-coded cases, each coding pair met to reconcile scoring discrepancies, reaching a final consensus score for each scale. Intercoder reliability was calculated by comparing the scores of two coders on every double-coded interaction. Reliabilities for the sensitivity parenting composite were .88 for mothers and .91 for grandmothers and .74 for mothers and .79 for grandmothers on the negative intrusiveness composite.

Measures

Caregiver behavior

Caregiver behavior during the dyadic free play interaction was rated using seven 5-point global rating scales (Cox & Crnic, 2002), sensitivity/responsiveness, intrusiveness, detachment/disengagement, positive regard for the child, negative regard for the child, animation, and stimulation of development, revised from scales developed in the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Study of Early Child Care (Cox, Paley, Burchinal, & Payne, 1999; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Early Child Care Research Network, 1999). The orthogonal principal components factor analysis with an oblique (promax) rotation suggested the presence of two distinct, relatively independent composites for both care-givers.

The sensitivity composite (α = .88) consisted of the mean of the reverse score for detachment/disengagement, and scores for sensitivity/responsiveness, positive regard, animation, and stimulation of development. The factor scores for the sensitivity factor were −.84, .79, .86, .84, and .77, respectively. Higher scores on this composite reflect parenting that is responsive, supportive, warm, positive, and stimulating. The negative parenting composite, negative intrusiveness (α = .64), represented the mean of scores for negative regard and intrusiveness. The factor loading scores for the negative intrusiveness factor were .77 and .88, respectively. Higher scores on this composite indicate parenting behaviors that are harsh, parent-centered, and affectively negative.

Income-needs ratio

Mothers provided information about total annual household income, which represented the sum of income from all people in the household from all sources. Income-to-needs ratios were calculated by dividing the reported household income by the federally determined poverty threshold for 2004 for the number of individuals living in the household. Income-to-needs ratios above 1 indicate that a family is able to provide for basic needs, and ratios below 1 indicate that the family is not earning a sufficient income to cover basic needs.

Psychological distress

The Brief Symptom Inventory-18 (BSI-18) (Derogatis, 2000), an 18-item self-report symptom inventory designed to reflect the psychological symptom patterns of normative and psychiatric respondents, was administered to mothers and grandmothers. Each item is rated on a 5-point scale ranging from 0 = not at all to 4 = extremely. The BSI-18 is composed of three subscales, somatization, depression, and anxiety. A composite score of psychological distress, the Global Severity Index (GSI), is calculated by summing the scores of each subscale. Internal consistency for the present study was α = .89 for mothers and α = .90 for grandmothers.

Social support

Mothers and grandmothers responded to a short form of the Questionnaire of Social Support (QSS) (Crnic & Booth, 1991). This 16-item version of the original 37-item scale includes four subscales: community involvement, friendship, family, and intimate relationships. Only the family support scale, which is composed of five items, was used in the present analyses. A sample item asks respondents, “How satisfied are you with the amount of help (as babysitters, sources of information, sympathetic ears) family members provide?” Respondents rated satisfaction on a 4-point scale ranging from 1 = very dissatisfied (I wish things were different) to 4 = very satisfied (I'm really pleased). The mean of items from the subscale was calculated with higher scores indicating higher levels of perceived social support. This measure attained acceptable levels of internal consistency for primary (α = .74) and secondary (α = .82) caregivers.

Analytical Strategies

Hierarchical linear models (Bryk & Raudenbush, 1992) were employed to explore factors predicting observed parenting behaviors. Specifically, random effects regression models using the PROC MIXED function in SAS 9.1 with Restricted Maximum Likelihood Estimates were estimated. Multi-level modeling techniques extend multiple regression models to account for the possible non-independence of within-family data. In this case, maternal and grandmother parenting are nested within family. Failing to account for this nesting of data could lead to inflated standard errors and thus inaccurate parameter and model fit estimates (Bryk & Raudenbush). Two separate models were estimated to predict sensitivity and negative intrusiveness. The same predictors were used for each dimension of parenting. The individual (level-1) predictors were generation (coded 1 for grandmothers and 0 for mothers), perceived family social support, and self-reported psychological distress. The family (level-2) predictors were race or ethnicity and maternal age. All significant interactions were probed using standard pick-a-point techniques, which have been validated in multilevel models (Bauer & Curran, 2005; Preacher, Curran, & Bauer, 2006).

RESULTS

Preliminary Analyses

Correlations and means of key variables are presented in Table 1. Child gender was not significantly correlated with parenting by either generation. In addition, income-to-needs ratios were not correlated with any household or caregiver characteristics or outcomes, perhaps reflecting the lack of variability within this disadvantaged sample. The mean reported income-to-needs ratio was 1.20 (0.87) with a range of 0 to 3.21. Neither child gender nor income-to-needs ratios were included as covariates in any of the models.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Bivariate Correlations Among Independent and Dependent Variables

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Maternal age | — | |||||||||

| 2. Race/ethnicitya | .19 | — | ||||||||

| 3. Mother distress | .10 | .28** | — | |||||||

| 4. Grandmother distress | −.07 | .18 | .16 | — | ||||||

| 5. Mother soc. support | −.12 | .04 | −.42* | −.48* | — | |||||

| 6. Grandmother soc. support | .09 | .19 | .06 | .07 | −.05 | — | ||||

| 7. Mother sensitivity | .21* | −.26* | .03 | −.03 | −.05 | −.02 | — | |||

| 8. Grandmother sensitivity | .01 | −.28* | −.01 | −.06 | −.03 | −.18 | .21* | — | ||

| 9. Mother neg. intrusive | .19 | .24* | .06 | −.01 | −.18 | .19 | .10 | −.23* | — | |

| 10. Grandmother neg. intrusive | −.15 | .27* | .01 | −.09 | −.05 | −.07 | −.16 | −.20 | .21* | — |

| M | 21.12 | 0.63 | 47.26 | 48.49 | 3.43 | 3.13 | 2.54 | 2.89 | 2.64 | 2.61 |

| SD | 4.32 | 0.48 | 10.14 | 9.81 | 0.56 | 0.72 | 0.79 | 0.77 | 0.73 | 0.80 |

Note: N = 105.

Race/Ethnicity: 0 = White, 1 = African American.

p < .05,

p < .01.

Given the unusual nature of the sample and the untargeted recruitment of the participants from the larger study, preliminary analyses were conducted to provide a descriptive overview of parenting by both generations before conducting analyses jointly predicting the observed parenting behaviors of mothers and grandmothers. The within family (correlation) and within generation (means) were examined. Sensitivity and negative intrusiveness observed for mothers and grandmothers were moderately positively correlated. Comparing mean parenting, grandmothers (mean = 2.89) were rated as more sensitive than mothers (mean = 2.54) t(103) = −4.45, p < .001. There was, however, no mean difference between generations in observed negative intrusiveness, t(103) = 0.44, p = .66).

Sensitivity

Results from the models predicting sensitive parenting are presented in Table 2. Following standard analytical procedures, the unconditional means model (Model 0) predicting sensitivity was estimated before testing any hypotheses. Further, although fixed effects were the focus of the study hypotheses, standard multilevel modeling procedures call for examination of random effects prior to interpretation of fixed effects. The random effects from this model suggested that there was no systematic nesting of sensitivity between families. In fact, none of the models tested to predict observed sensitive parenting suggested the nesting of sensitivity between families. There was, however, significant observed variation in sensitivity within families (σ2 = 0.54, z = 6.712, p < .0001), indicating considerable variability in individual levels of sensitive parenting observed for mothers and grandmothers living within the same household.

Table 2.

Regression Coefficients and Variance Components for Models of Sensitive Parenting

| Sensitive Parenting | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 0 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||||

| B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | |

| Fixed Effects | ||||||||

| Intercept | 2.71*** | 0.06 | 2.87*** | 0.11 | 2.84*** | 0.11 | 2.82*** | 0.11 |

| Level 1 | ||||||||

| Generation | 0.33** | 0.10 | 0.33** | 0.10 | 0.37*** | 0.10 | ||

| Maternal Age × Generation | −0.04 | 0.02† | −.04† | 0.02 | −0.04 | 0.02 | ||

| Family Social Support | −0.01 | 0.07 | −0.00 | 0.07 | ||||

| Psychological Distress | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Family Support × Psychological Distress | −0.01 | 0.01 | ||||||

| Maternal Age × Psychological Distress | 0.01* | 0.01 | ||||||

| Race × Psychological Distress | −0.00 | 0.01 | ||||||

| Level 2 | ||||||||

| Racea | −0.50*** | 0.12 | −0.47*** | 0.13 | −0.49*** | 0.12 | ||

| Maternal Age | 0.05** | 0.02 | 0.06** | 0.02 | 0.05* | 0.02 | ||

| Random Effects | ||||||||

| Intercept | 0.10 | 0.07 | 0.08† | 0.06 | 0.07† | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.06 |

| Residual | 0.54*** | 0.08 | 0.47*** | 0.07 | 0.47*** | 0.07 | 0.48*** | 0.07 |

Note: N = 105.

Race/Ethnicity: 0 = White, 1 = African American.

p < .10,

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

Maternal Age and Sensitivity

To address the first goal regarding maternal age, Model 1 included fixed effects for race as a demographic control, maternal age, generation, and an interaction between maternal age and generation. This model did not support the inclusion of random effects for generation and the interaction between generation and maternal age, as the boundary condition was met (covariance = 0). The random effects results from this model suggest that significant within-family variation persisted (σ2 = 0.08, z = 6.67, p < .001). Turning to fixed effects, contrary to Hypothesis 1, the interaction between generation and maternal age was not significant. The main effect for maternal age, however, was significant, as maternal age was positively related to sensitive parenting for both generations. In addition, there were significant observed effects for race and generation, indicating that African American race was associated with lower levels of sensitivity, and grandmother generational status was associated with higher levels of sensitivity.

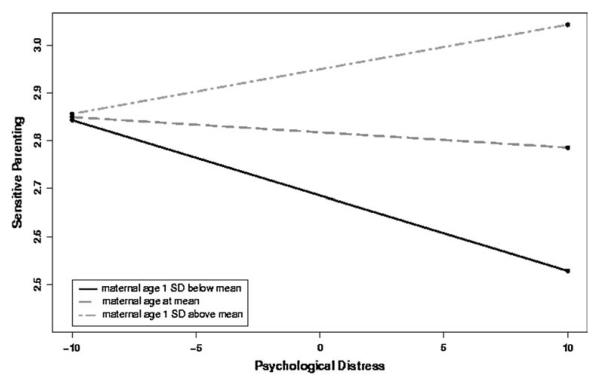

Psychological Distress and Sensitivity

To address the second goal regarding identification of moderators in the relationship between psychological distress and parenting, psychosocial variables were added to the demographic variables that were the focus of the first goal. Specifically, Model 2 added self-reported psychological distress and perceived family social support to the level-1 fixed effect predictors of sensitive parenting. Including these factors neither produced a significant predictor of parenting nor altered the relationship between the fixed and random effects and sensitivity. Finally, to test Hypotheses 2 – 4, Model 3 included potential moderators in the relationship between self-reported psychological distress and observed sensitive parenting. The model did not support the inclusion of any random slopes. Additional fixed effect predictors consisted of interaction terms representing the product of psychological distress and maternal age, psychological distress and family social support, and psychological distress and race. Significant within family variance remained in the final model (σ2 = 0.48, z = 6.59, p < .001). Comparison of this final model to the unconditional means model indicates that approximately 10% of the observed variance in sensitive parenting behaviors was accounted for by the independent variables. This final model yielded several significant fixed effects. Race and generation continued to predict observed sensitivity in the same directions. A significant interaction between maternal age and psychological distress emerged. This cross-level interaction was probed by testing the simple slopes defining the relationship between psychological distress at levels of maternal age 1 SD below the mean, at the mean, and 1 SD above the mean. Consistent with Hypothesis 3, as presented in Figure 1, higher levels of self-reported psychological distress were associated with lower levels of observed sensitive parenting by mothers and grandmothers in families in which maternal age was 1 SD below the mean (beta = 0.03, SE = 0.14, p = .02). The mean age for mothers in this sample was 21.17 and the SD was 4.32, indicating that when mothers were 16.85 or younger, mean or higher levels of psychological distress were linked to less sensitive parenting. Post hoc analyses did not reveal a significant three-way interaction between generation, maternal age, and psychological distress. Hypotheses 2 and 4, which predicted that social support and race or ethnicity would moderate the relationship between psychological distress and sensitive parenting, were not supported.

Figure 1.

Maternal Age Moderates the Relationship Between Psychological Distress and Sensitive Parenting.

Negative Intrusiveness

As shown in Table 3, similar techniques were utilized to model the relationship between maternal age and psychological distress and observed negative intrusive parenting behaviors. The unconditional means or empty model (Model 0) predicting negative intrusiveness suggested that there was significant between-family (τ00 = 0.13, z = 1.99, p = .02) and within-family (σ2 = 0.45, z = 6.59, p < .001) variance in negative intrusiveness. The intraclass correlation suggests that 22.53% of the observed variance in negative intrusiveness was accounted for by between-family variance.

Table 3.

Regression Coefficients and Variance Components for Models of Negative Intrusive Parenting

| Negative Intrusive Parenting | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 0 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||||

| B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | |

| Fixed Effects | ||||||||

| Intercept | 2.62*** | 0.06 | 2.38*** | 0.11 | 2.36*** | 0.11 | 2.38*** | 0.11 |

| Level 1 | ||||||||

| Generation | −0.03 | 0.10 | −0.03 | 0.10 | −0.04 | 0.10 | ||

| Maternal Age × Generation | −0.06* | 0.02 | −0.06** | 0.02 | −0.06** | 0.02 | ||

| Family Social Support | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.07 | ||||

| Psychological Distress | —0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | ||||

| Family Support × Psychological Distress | 0.01 | 0.01 | ||||||

| Maternal Age × Psychological Distress | 0.01 | 0.01 | ||||||

| Race × Psychological Distress | −0.02* | 0.01 | ||||||

| Level 2 | ||||||||

| Racea | 0.42*** | 0.12 | 0.44*** | 0.13 | 0.43*** | 0.12 | ||

| Maternal Age | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | ||

| Random Effects | ||||||||

| Intercept | 0.13* | 0.07 | 0.11* | 0.06 | 0.11* | 0.06 | 0.11* | 0.06 |

| Residual | 0.45*** | 0.07 | 0.43*** | 0.07 | 0.43*** | 0.07 | 0.48*** | 0.07 |

Note: N = 105.

Race/Ethnicity: 0 = White, 1 = African American.

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

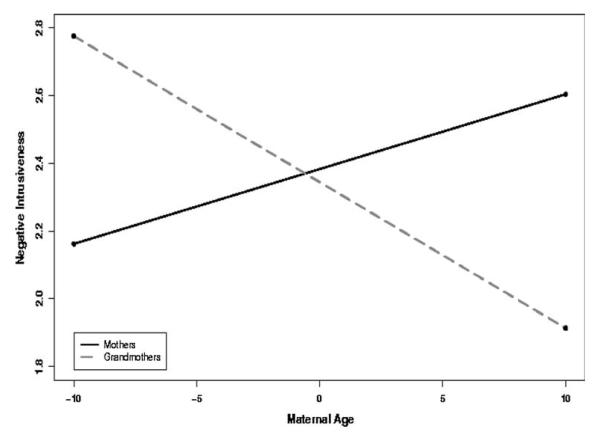

Maternal Age and Negative Intrusiveness

Model 1 included fixed effects for the level-2 predictors race and maternal age, the level-1 predictor generation, and an interaction term representing a cross-level interaction between maternal age and generation to test Hypothesis 1. The random effects revealed that significant between-family variance persisted (τ00 = 0.11, z = 1.74, p = .04), but there was not a significant random slope for generation. Dropping this nonsignificant random slope from the model did not reduce the model fit, χ2(1) = 0.42, p = .60. The fixed effects indicate a main effect for race, as African American identity was associated with higher levels of observed negative intrusiveness. In addition, a significant interaction between maternal age and generation emerged. The term representing this interaction was retained in the model. To ensure interpretability, however, it was not probed until the final model. In this final model, as described in detail below, the interaction between maternal age and generation remained significant. The nature of this cross-level interaction was determined by plotting the simple slopes of the lines defining the relationship between maternal age and negative intrusiveness for mothers and for grandmothers. As depicted in Figure 2, contrary to Hypothesis 1, which predicted young age as a disadvantage for mothers only, older maternal age was associated with lower levels of negative intrusiveness for grandmothers only.

Figure 2.

Generation Moderates the Relationship Between Maternal Age and Negative Intrusiveness.

Psychological Distress and Negative Intrusiveness

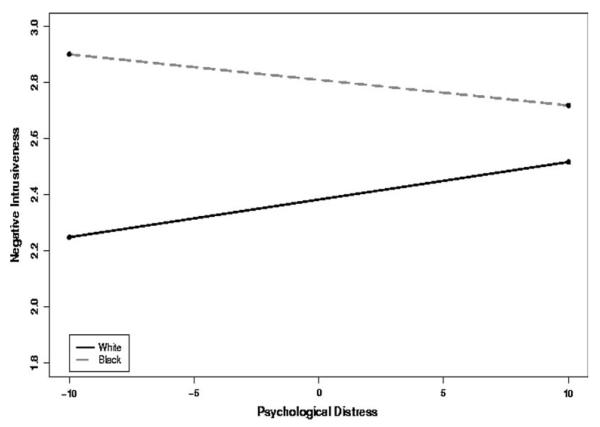

Model 2 included psychological distress and family social support as level-1 fixed effect predictors. This model failed to yield new statistically significant relationships. The final model (Model 3) included potential moderators in the relationship between self-reported psychological distress and observed sensitive parenting in order to test Hypotheses 2 – 4. Random effects for generation and psychological distress were included in the initial model; however, these random slopes were not statistically significant, indicating that the relationships between generation and negative intrusiveness and psychological distress and negative intrusiveness do not vary between families. These random effects were dropped from the model with no resulting decrement in model fit, χ2(2) = 3.62, p = .25. Significant between-family variation in observed negative intrusiveness (τ00 = 0.11, p = .03) persisted. The final model accounts for approximately 13% of the observed between-family variance. The intraclass correlation suggests that, overall, 22% of the observed variance is between families. In addition, this final model explains 7% of the observed within-family variance, and, overall, 77% of the variance is within family.

In support of Hypothesis 4, the fixed effects from this final model yielded a significant interaction between race and psychological distress. The nature of this cross-level interaction was determined by plotting the slopes of the relationship between self-reported psychological distress and observed negative intrusiveness for African Americans and for European Americans. As depicted in Figure 3, the line defining the relationship between psychological distress and negative intrusiveness was significant (beta = 0.43, p < .001) for White families only, such that higher levels of psychological distress were associated with higher levels of observed negative intrusiveness for White caregivers. Post hoc analyses failed to produce a significant three-way interaction between race, psychological distress, and generation. Further, there was no support for Hypotheses 2 and 3 predicting moderating roles for social support and maternal age.

Figure 3.

Race Moderates the Relationship Between Psychological Distress and Negative Intrusiveness.

DISCUSSION

This study contributes to the limited research on family processes in three-generation households. There is a paucity of research on grandmother-grandchild relationships, and maternal behaviors are rarely studied with explicit consideration of the multigenerational family context (Jones et al., 2007). The present study addresses these gaps by examining risks to parenting by both generations.

Intergenerational Parenting

Although observed sensitive parenting by both generations was modestly correlated, grandmothers displayed higher levels of sensitivity in their interactions with infants. This generational advantage may stem from greater grandmother experience in caring for an infant. The grandmothers may be more experienced at picking up on the signals of an infant and reacting accordingly, a key dimension of sensitive parenting. The multilevel models revealed that there was no nesting of sensitivity within household, suggesting little intergenerational transfer of sensitive parenting practices. In contrast, negative intrusive parenting behaviors displayed by mothers and grandmothers were also moderately correlated, but there were no mean differences between the negative parenting displayed by mothers and grandmothers, and there was evidence of systematic nesting of negative intrusiveness within household. A similar level of negative parenting across generations is consistent with Chase-Lansdale and colleagues' (1994) finding in their study of triadic grandmother-mother-preschool child interactions. There may be a greater contagion of negative parenting within households. These findings are in line with prospective examinations of the intergenerational transfer of harsh parenting (Scaramella & Conger, 2003; Simons, Whitbeck, B., Conger, & Wu, 1991). The lack of a main effect for generation may suggest that grandmothers do not have the benefit of experience in terms of negative intrusive behaviors, as the risks they face may trump this experience advantage.

Psychological Distress

This study provided limited support for pathways linking psychological distress to higher levels of negative parenting and lower levels of positive parenting. There was no main effect of psychological distress on sensitive parenting. Furthermore, contrary to Hypothesis 2, perceived levels of family social support did not moderate the relationship between psychological distress and sensitive parenting. Family social support was correlated negatively with psychological distress. Perhaps those caregivers who reported higher perceptions of family support were more likely to experience lower levels of psychological distress, and hence high levels of psychological distress in the presence of family social support (the conditions necessary for a buffering effect) may not have been observed in this sample.

Maternal Age

This study presented a unique opportunity to study the role of maternal age in the prediction of psychological distress and parenting in a sample with mothers of varying ages residing in similar household structures. Maternal age failed to emerge as a main effect on maternal parenting. As hypothesized (Hypothesis 3), maternal age moderated the relationship between psychological distress and sensitive parenting. When mothers were approximately 17 or younger (1 SD below the mean), there was a negative association between psychological distress and sensitive parenting by mothers and grandmothers. Post hoc analyses did not support the presence of a significant three-way interaction between maternal age, generation, and psychological distress, indicating that maternal age in conjunction with elevated psychological distress posed a risk to parenting by mothers and grandmothers. These findings suggest that maternal age is highly relevant to functioning in these families, but the lack of main effects for maternal age may in part account for the mixed findings in the literature linking maternal age to parenting and to child outcomes.

The findings regarding differential effects of maternal age on mother and grandmother negative intrusiveness underscore the utility of a life course framework to consider implications of the interdependent nature of the transition to parenthood and grandparenthood. Consistent with Hypothesis 1, generation moderated the relationship between maternal age and negative intrusive parenting. Contrary to the hypothesis, however, younger maternal age was associated with higher levels of observed negative intrusiveness by grandmothers only. Perhaps the parenting of young mothers is protected in terms of negative intrusiveness when they are residing with their mothers, in line with findings regarding more positive parenting among young mothers coresiding with grandmothers (Chase-Lansdale et al., 1994; Shapiro & Mangelsdorf, 1994).

The parenting of the mothers of young mothers, however, may be particularly compromised. Perhaps these grandmothers face elevated levels of stress that are not captured by the measures employed in this study, as they bear the burden of caring for an additional dependent, perhaps without the financial support of the mother. Mothers of young adolescent mothers were likely juggling multiple responsibilities and developmental demands, including simultaneously raising an infant grandchild and an adolescent child. Many mothers of adolescent mothers may be disappointed and angry with the mother for becoming pregnant and resentful of the “early” and unwanted transition to grandparenthood (Burton & Bengston, 1985; Sadler & Clemmens, 2004). These negative intergenerational feelings may indirectly foster negative parenting of the infant. In addition, the intergenerational nature of negative parenting may be relevant. Negative or harsh parenting of adolescents may be linked to elevated levels of maladaptive adolescent outcomes that may place females at risk for teenage pregnancy (Coley & Chase-Lansdale, 1998; Moore & Brooks-Gunn, 2002). Thus, grandmothers with teenage mothers may be more likely to exhibit negative parenting behaviors in interactions with their grandchildren because that behavior reflects their general parenting style.

Cultural Context

Finally, the cultural context was related to parenting. Consistent with Hypothesis 4, race or ethnicity moderated the relationship between psychological distress and negative intrusive parenting such that higher levels of psychological distress were associated with higher levels of negative intrusiveness for White families only. This finding is consistent with studies of parenting of older children that suggest that there is a weaker link between psychological distress and negative parenting among African Americans (Johnson, 2000; McLeod & Nonnemaker, 2000). Some researchers have suggested that the lack of relationship between psychological well-being and negative parenting by African Americans implies that the use of more harsh or negative parenting is more culturally acceptable or adaptive for African Americans (Deater-Deckard & Dodge, 1997). Negative parenting, therefore, is not the result of impaired parental functioning and hence is not so strongly linked to negative child outcomes. Alternatively, the risks to parenting by African Americans may be deeper and more distinct, and they may exert a direct effect on parenting such that the relationship between psychological distress per se and parenting is weak (McLoyd, 1998). Post hoc analyses that included other forms of disadvantage, including grandmother education, mother and grandmother employment, economic strain, household composition, and income-to-needs ratios failed to change the relationships between race and parenting. These findings underscore the importance of within-group analyses and studies in order to explore developmental pathways within African American samples (Garcia Coll et al., 1996; McLoyd et al., 2000; Murry et al., 2001). The sample size in the present study does not provide the statistical power required for multilevel within-group analyses. Further, although the present sample only included African Americans and European Americans, these issues should be examined in other ethnic minority groups.

It is important to note that the measures of psychological distress and parenting were both developed in majority White samples, although they have been validated in multiethnic samples. This study, like many others in this area, may fail to capture all of the risks associated with parenting among African Americans. In this study, race is also confounded with context. All families resided in chronically disadvantaged nonurban communities transitioning into service-based economies, but most of the African American families resided in the South. The context shaped by the legacy of historical patterns of discrimination in the South may confer disadvantage beyond that measured by income or education. These disadvantages may be amplified in multi-generational families given the intergenerational transfer of disadvantage.

Limitations and Future Directions

Several limitations to this study should be noted. The quality of the relationship between the mother and the grandmother was not included in the present study, yet these factors are likely linked to parenting behaviors (Wakschlag, Chase-Lansdale, & Brooks-Gunn, 1996). In addition, the identity of the head of the household and the reasons for coresidence are unknown. Only 9% of the mothers reported that they owned the home, and 51% reported that someone else in the household, possibly the grandmother, owned the home. Approximately 30% of the mothers reported that the home was rented for cash, but the individual who paid the rent was not noted. In most families, the grandmothers had lived at the residence for longer or for the same number of years as the mother, therefore suggesting that the mothers may have been living in the grandmothers' homes (in many cases their own households of origin), as opposed to the grandmothers moving into the mothers' residences. Given the relatively young range of grandmother age, for most families in the sample, coresidence was likely an adaptation to care for the grandchild, the mother, or both, not an adaptation to care for the grandmother.

Finally, similar to a criticism leveled at research on fathering that evaluates fathers' behaviors using measures developed and validated within maternal samples, the parenting constructs used in the present study were not designed particularly for grandmothers. It remains unknown if grandmothers display different kinds of parenting behaviors or if they contribute unique elements to the interaction with the child or both. Future research that focuses exclusively on grandparents may illuminate these potential patterns.

The goal of this study was to explore parenting, but it is imperative to understand how variations in parenting behavior by mothers and grandmothers may interact to influence child behaviors by including child outcomes in future research. In addition, longitudinal research is essential to understanding the nature, course and implications of family processes in these household structures. There may be considerable mobility in household structure as mothers move from their households of origin to households with romantic partners and back again as those relationships dissolve (Nelson, 2006). The nature of the mother-grandmother and the grandmother-grandchild relationship across time once these are no longer coresident relationships remains an empirical question.

Implications

This study adds to the mounting evidence suggesting that young maternal age by itself may not present a risk to parenting. In the presence of other risks, however, including elevated psychological distress, younger maternal age is a risk factor for less optimal parenting. Further, consistent with a life course perspective that considers the timing of transitions within families (i.e., Elder, 1998), young maternal age is associated with more negative grandmother parenting. Coresidence of grandmothers and young mothers may not foster positive childrearing environments, especially if the coresidence is accompanied by risk factors for the development of less optimal parenting. This study also suggests the need for whole family intervention, as the parenting of mothers and grandmothers may be at risk. Households in which parenting by both generations is compromised may provide a particularly risky early environment. The families that may be the most at risk, and thus the most in need of intervention, may be households in which young mothers and grandmothers are coresiding. Taken together, the findings from this study suggest that parenting behaviors in multigenerational households are complex, varied, and worthy of further investigation.

Acknowledgments

This article is based on a dissertation submitted by the first author to the Psychology Department at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. The data are from the Family Life Project, which is supported by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (P01-HD-39667) with cofunding from NIDA. The dissertation research was supported by a Carolina Consortium on Human Development Predoctoral Fellowship, which was provided by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (T32-HD07376 Human Development: Interdisciplinary Research Training) to the Center for Developmental Science, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and awarded to the first author. The Family Life Project Key Investigators include Lynne Vernon-Feagans (PI), Martha Cox, Clancy Blair, Margaret Burchinal, Linda Burton, Keith Crnic, Ann Crouter, Patricia Garrett-Peters, Mark Greenberg, Stephanie Lanza, Roger Mills-Koonce, Debra Skinner, Emily Werner, and Michael Willoughby. The first author is grateful to the dissertation committee members, Lorraine Taylor, Martha Cox, Vonnie McLoyd, Linda Burton, and Mitch Prinstein for their feedback and guidance. We thank the participant families, the data collectors, and the observational coding teams.

REFERENCES

- Apfel N, Seitz V. African American adolescent mothers, their families, and their daughters: A longitudinal perspective over twelve years. In: Ross Leadbeater BJ, Way N, editors. Urban girls: Resisting stereotypes, creating identities. New York University Press; New York: 1996. pp. 149–170. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer DJ, Curran PJ. Probing interactions in fixed and multilevel regression: Inferential and graphical techniques. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2005;40:373–400. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr4003_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlin LJ, Brady-Smith C, Brooks-Gunn J. Links between childbearing age and observed maternal behaviors with 14-month-olds in the Early Head Start research and evaluation project. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2002;23:104–129. [Google Scholar]

- Black MM, Nitz K. Grandmother co-residence, parenting and child development among low-income urban teen mothers. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1996;18:218–226. doi: 10.1016/1054-139X(95)00168-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black MM, Papas MA, Hussey JM, Hunter W, Dubowitz H, Kotch JB, English D, Schneider M. Behavior and development of preschool children born to adolescent mothers: Risk and 3-generation households. Pediatrics. 2002;109:573–580. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.4.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blalock LL, Tiller VR, Monroe PA. “They get you out of courage”: Persistent deep poverty among former welfare reliant women. Family Relations. 2004;53:127–137. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley RH, Corwyn RF. Socioeconomic status and child development. Annual Review of Psychology. 2002;53:371–399. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown AC, Brody GH, Stoneman Z. Rural black women and depression: A contextual analysis. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2000;62:197–198. [Google Scholar]

- Bryk AS, Raudenbush SW. Hierarchical linear models for social and behavioral research: Applications and data analysis methods. Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Burton LM. Age norms, the timing of family role transitions, and intergenerational caregiving among aging African American women. The Gerontologist. 1996;36:199–208. doi: 10.1093/geront/36.2.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton LM, Bengston VL. Black grandmothers: Issues of timing and continuity. In: Burton LM, Bengston VN, editors. Grandparenthood. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1985. pp. 61–77. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell CH, Antonucci TC, Jackson JS. Supportive/conflictual family relations and depressive symptomatology: Teenage mother and grandmother perspectives. Family Relations. 1998;47:395–402. [Google Scholar]

- Caputo RK. Depression and health among grandmothers co-residing with grandchildren in two cohorts of women. Families in Society. 2000;82:473–483. [Google Scholar]

- Chase-Lansdale PL, Brooks-Gunn J, Zamsky ES. Young African-American multigenerational families in poverty: Quality of mothering and grandmothering. Child Development. 1994;65:373–393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chase-Lansdale PL, Gordon RA, Coley RL, Wakschlag LS, Brooks-Gunn J. Young African American multigenerational families in poverty: The contexts, exchanges and processes of their lives. In: Hetherington EM, editor. Coping with divorce, single parenting and remarriage: A risk and resiliency perspective. Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 1999. pp. 165–191. [Google Scholar]

- Coley RL, Chase-Lansdale PL. Adolescent pregnancy and parenthood. American Psychologist. 1998;53:152–166. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.53.2.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox M, Crnic K. Qualitative ratings for parent-child interaction at 3 – 12 months of age. Department of Psychology, University of North Carolina; Chapel Hill: 2002. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Cox MJ, Paley B, Burchinal M, Payne CC. Marital perception and interactions across the transition to parenthood. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1999;61:611–625. [Google Scholar]

- Crnic KA, Booth CL. Mothers' and fathers' perceptions of daily hassles of parenting across early childhood. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1991;53:1042–1050. [Google Scholar]

- Dallas C. Family matters: How mothers of adolescent parents experience adolescent pregnancy and parenting. Public Health Nursing. 2004;21:347–353. doi: 10.1111/j.0737-1209.2004.21408.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K, Dodge K. Externalizing behavior problems and discipline revisited: Nonlinear effects and variation by culture, context, and gender. Psychological Inquiry. 1997;8:161–175. [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR. BSI 18: Brief Symptom Inventory-18: Administration, scoring and procedures manual. Pearson Assessments; Minneapolis, MN: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- East PL, Felice ME. Adolescent pregnancy and parenting. Lawrence Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Elder GH. The life course as developmental theory. Child Development. 1998;69:1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elder GH, Eccles JS, Ardelt M, Lord S. Inner-city parents under economic pressure: Perspectives on the strategies of parenting. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1995;57:771–784. [Google Scholar]

- Foster EM, Kalil A. Living arrangements and children's development in low-income White, Black and Latino families. Child Development. 2007;78:1657–1674. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia Coll C. Developmental outcomes of minority infants: A process-oriented look into our beginnings. Child Development. 1990;61:270–289. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia Coll C, Lamberty G, Jenkins R, McAdoo HP, Crnic K, Wasik BH, Garcia HV. An integrative model for the study of developmental competencies in minority children. Child Development. 1996;67:1891–1914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George SM, Dickerson BJ. The role of the grandmother in poor single-mother families and households. In: Dickerson BJ, editor. African American single mothers. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1995. pp. 146–163. [Google Scholar]

- George SM, Dickerson BJ. The role of the grandmother in poor single-mother families and households. In: Dickerson BJ, editor. African American single mothers. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2000. pp. 146–163. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman C, Silverstein M. Grandmothers raising grandchildren: Family structure and well-being in culturally diverse families. The Gerontologist. 2002;42:676–689. doi: 10.1093/geront/42.5.676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashima PY, Amato PR. Poverty, social support and parental behavior. Child Development. 1994;65:394–403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayslip B, Kaminski PL. Grandparents raising their grandchildren: A review of the literature and suggestions for practice. The Gerontologist. 2005;45:262–269. doi: 10.1093/geront/45.2.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter AG, Taylor RJ. Grandparenthood in African American families. In: Szinovacz ME, editor. Handbook on grandparenthood. Greenwood Press; Westport, CT: 1998. pp. 70–86. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson D. Disentangling poverty and race. Applied Developmental Science. 2000;4:55–67. [Google Scholar]

- Jones DJ, Zalot AA, Foster SE, Sterret E, Chester C. A review of childrearing in African American single mother families: The relevance of a coparenting framework. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2007;16:671–683. [Google Scholar]

- Kalil A, Spencer MS, Spieker SJ, Gilchrist LD. Effects of grandmother coresidence and quality of family relationships on depressive symptoms in adolescent mothers. Family Relations. 1998;47:433–441. [Google Scholar]

- Klein K, Forehand R. Family processes as resources for African American children exposed to a constellation of sociodemographic risk factors. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 2000;29:53–65. doi: 10.1207/S15374424jccp2901_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee RL, Ensminger ME, LaVeist TA. The responsibility continuum: Never primary, coresident and caregiver heterogeneity in the African-American grandmother experience. International Journal of Aging and Human Development. 2005;60:295–304. doi: 10.2190/KT7G-F7YF-E5U0-2KWD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnuson KA, Duncan GJ. Parents in poverty. In: Borenstein MH, editor. Handbook of Parenting. Vol. 4. Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2002. pp. 95–121. [Google Scholar]

- McLeod JD, Nonnemaker JM. Poverty and child emotional and behavioral problems: Racial/ethnic differences in processes and effects. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2000;41:137–161. [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd VC. Socioeconomic disadvantage and child development. American Psychologist. 1998;53:185–204. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.53.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd VC, Cauce AM, Takeuchi D, Wilson L. Marital processes and parental socialization in families of color: A decade review of research. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2000;62:1070–1093. [Google Scholar]

- Moore MR, Brooks-Gunn J. Adolescent parenthood. In: Borenstein MH, editor. Handbook of parenting. Vol. 3. Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2002. pp. 173–214. [Google Scholar]

- Murry VM, Bynum MS, Brody GH, Willert A, Stephens D. African American single mothers and children in context: A review of studies on risk and resilience. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2001;4:133–155. doi: 10.1023/a:1011381114782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Early Child Care Research Network Child care and mother-child interaction in the first three years of life. Developmental Psychology. 1999;35:1399–1413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson MK. Single mothers “do” family. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2006;68:781–795. [Google Scholar]

- Orthner DK, Jones-Sanpei H, Williamson S. The resilience and strengths of low-income families. Family Relations. 2004;53:159–167. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson JL, Hunter AG, Ensminger ME, Kellam SG. Black grandmothers in multigenerational households: Diversity in family structure and parenting involvement in the Woodlawn community. Child Development. 1990;61:434–442. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02790.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petterson SM, Albers AB. Effects of poverty and maternal depression on early childhood development. Child Development. 2001;72:1794–1813. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Curran PJ, Bauer DJ. Computational tools for probing interaction effects in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 2006;31:437–448. [Google Scholar]

- Rosman EA, Yoshikawa H. Effects of welfare reform on children of adolescent mothers: Moderation by maternal depression, father involvement, and grandmother involvement. Women & Health. 2001;32:253–290. doi: 10.1300/J013v32n03_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rural and Appalachian Youth and Families Consortium Parenting practices and interventions among marginalized families in Appalachia. Family Relations. 1996;45:387–396. [Google Scholar]

- Sadler LS, Anderson SA, Sabatelli RM. Parental competence among African American adolescent mothers and grandmothers. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 2001;16:217–233. doi: 10.1053/jpdn.2001.25532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadler LS, Clemmens DA. Ambivalent grandmothers raising teen daughters and their babies. Journal of Family Nursing. 2004;10:211–231. [Google Scholar]

- Scaramella LV, Conger RD. Intergenerational continuity of hostile parenting and its consequences: The moderating influence of children's negative emotional reactivity. Social Development. 2003;12:420–439. [Google Scholar]

- Schweingruber HA, Kalil A. Decision making and depressive symptoms in black and white multigenerational teen-parent families. Journal of Family Psychology. 2000;14:556–569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- See LA, Bowles D, Darlington M. Young African American grandmothers: A missed developmental stage. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Sciences. 1998;1:281–303. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro JR, Mangelsdorf SC. The determinants of parenting competence in adolescent mothers. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1994;23:621–639. doi: 10.1007/BF01537633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons RL, Whitbeck LB, Conger RD, Wu CI. Intergenerational transmission of harsh parenting. Developmental Psychology. 1991;27:159–171. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau 2006 American community survey. S1001, Grandchildren characteristics. 2006 Available from: http://www.factfinder.census.gov/servlet.

- Wakschlag LS, Chase-Lansdale PL, Brooks-Gunn J. Not just “ghosts in the nursery”: Contemporaneous intergenerational relationships and parenting in young African-American families. Child Development. 1996;67:2131–2147. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1996.tb01848.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]