SYNOPSIS

Objective

The primary goal of this study was to examine contextual, child, and maternal factors that are associated with mothers’ early emotion talk in an ethnically diverse, low-income sample.

Design

Emotion talk (positive and negative labels) was coded for 1111 mothers while engaged with their 7-month-olds in viewing an emotion-faces picture book. Infant attention during the interaction was also coded. Mothers’ parenting style (positive engagement and negative intrusiveness) was coded during a dyadic free-play interaction. Demographic information was obtained, as well as maternal ratings of child temperament and mother’s knowledge of infant development.

Results

Hierarchical regression analyses revealed that social context and maternal qualities are significant predictors of mothers’ early positive and negative emotion talk. In particular, mothers who were African American, had higher income, and who showed more positive engagement when interacting with their infants demonstrated increased rates of positive and negative emotion talk with their infants. For negative emotion talk, social context variables moderated other predictors. Specifically, infant attention was positively associated with negative emotion talk only for African American mothers, and knowledge of infant development was positively associated with negative emotion talk only for non-African American mothers. The positive association between maternal positive engagement and negative emotion talk was greater for lower-income families than for higher-income families.

Conclusions

Mothers’ emotion language with infants is not sensitive to child factors but is associated with social contextual factors and characteristics of the mothers themselves.

INTRODUCTION

Researchers in the area of socioemotional development have long emphasized the parents’ critical role in the socialization of emotions in their children. As socializing agents, parents influence children’s conceptions of emotions in two primary ways. The first involves nonverbal communication about emotions through parental emotional expressions and emotional reactions in situations that involve their children. The second involves verbal communication through talk about emotions (Denham, Zoller, & Couchoud, 1994; Eisenberg, Cumberland, & Spinrad, 1998). By talking about emotions, parents heighten children’s awareness and understanding of emotional states and promote children’s emotion-related conceptual systems (Dunn, Brown, Slomkowski, Telsa, & Youngblade, 1991; Malatesta & Haviland, 1982).

Most researchers have investigated emotion talk in the context of mothers’ conversations with verbal children who are capable of influencing the nature and content of the emotional discourse. Few researchers have examined maternal emotion talk during infancy, even though mothers regularly use affective language with their infants (Malatesta & Haviland, 1982). Recent research has highlighted the importance of specific types of maternal talk during infancy for children’s later development. In particular, Meins and colleagues reported that mothers’ appropriate references to internal states (e.g., knowing, thinking, feeling) during interactions with their six-month-olds is positively associated with children’s theory of mind performance at age four (Meins, Fernyhough, Wainwright, Gupta, Fradley, & Tuckey, 2002). Mothers’ use of desire language (e.g., like, want, hope) with 15-month-olds has also been found to be positively associated with children’s emotion understanding at 24 months of age, even after controlling for potentially confounding variables (Taumoepeau & Ruffman, 2006). These findings suggest that mothers who use early mental state language likely provide an important context for the development of children’s sociocognitive skills. Similarly, mothers who engage in early emotion talk may also provide an important context for the development of children’s socioemotional skills. We know surprisingly little about which mothers may be predisposed to engage in early emotion talk with their infants.

Previous work has shown that parents’ beliefs and behaviors are determined by factors at multiple levels, including demographics, child characteristics, and parental knowledge and qualities (e.g., Bornstein & Bradley, 2003; Bornstein, Haynes, & Painter, 1998; Goodnow, 2002; Sameroff, Seifer, & Elias, 1982). In the present study, we adopt a multivariate ecological framework (Belsky, 1984; Bronfrenbrenner & Morris, 1998; Lerner, Rothbaum, Boulos, & Castellino, 2002) to examine factors at multiple levels that influence maternal emotion talk to her infant during a picture book interaction. Within this framework, blocks of variables are organized in order of their distal to proximal causal relation to emotion language, such that social context would be most distal to emotion language, child characteristics would be more proximal, and personal characteristics of the parent would be the most proximal. In the present study, we examine simultaneously the more distal influences, including the social context (ethnicity and income) and the child’s personal characteristics (temperamental distress, attention, and gender), as well as the more proximal influences of the mothers’ own attributes and cognitions (parenting style and knowledge of infant development). Given our ecological systems framework, we also examine the potential moderation of the social context variables, with variables at the child and parent levels. Furthermore, these associations are examined as they exist in an ethnically diverse and predominantly low-income sample. Relatively few studies have examined mothers’ emotion talk among economically disadvantaged populations, even though low-income mothers have been reported to value social-emotional knowledge and to engage in emotion-related discourse with their children (Beals, 1993; Blake, 1993).

Social Context: Ethnicity and Socioeconomic Status (SES)

Ethnicity

Sociocultural factors, such as ethnicity, influence how emotions are defined, expressed, and regulated (Halberstadt, 1991; Lutz & White, 1986; Markus & Kitayama, 1991; Mesquita & Frijda, 1992) and likely influence the extent to which mothers use emotion language. Research studies provide empirical support for ethnic variation in maternal emotion discourse (e.g., Cervantes, 2002; Eisenberg, 1999; Wang, 2001; Wang & Fivush, 2005). Although these studies contribute to the growing body of literature on emotion socialization among minority populations, few have included African American mothers. In one exception, Flannagan and Perese (1998) found no associations between ethnicity and the overall tendency to discuss emotions in naturalistic conversations about school experiences among African American, European American, and Mexican American mother-child dyads. However, relative to the other groups, African American dyads made more emotional references when discussing noninterpersonal nonacademic topics, and European Americans made more emotional references when discussing learning topics.

The extant literature also suggests that the perception, expression, and experience of emotions may be different for middle-class African Americans and other groups. For example, African American adults have been reported to rate the intensity of facial expressions higher for negative emotions of anger, disgust, and fear and reported expressing anger more frequently than other ethnic groups (e.g., Asian American, European American, Latin American) (Matsumoto, 1993). African American adults have also been found to show more positive facial expressions in response to emotional imagery and more blood pressure reactivity in emotional contexts than European Americans (Vrana & Rollock, 2003). These findings suggest that the salience of emotional aspects of the environment may be greater for African American groups. As such, this group may be more attuned to perceiving and experiencing emotional events. Additionally, the emphasis on emotional expression in African cultural heritage, as well as the African American cultural emphasis on oral and aural modes of communication (Boykin, 1986; White, Parham, & Jennings, 1996), may lead African American mothers to attend to and comment on emotions more frequently.

SES

Having limited economic resources has been associated with a greater use of negative socialization behaviors among parents (Conger, Conger, Elder, & Lorenz, 1992). The challenges and stresses associated with low SES also appear to contribute to abbreviated mother-child verbal interactions, including less talk, a more restricted vocabulary, and shorter conversations (Flannagan, Baker-Ward, & Graham, 1995; Hoff-Ginsberg, 1991; Tizard, Hughes, Carmichael, & Pinkerton, 1983). The emotional content of mother-child conversations has also been shown to vary with SES. For example, lower SES mother-child dyads have been found to make fewer emotional references than higher SES dyads when talking to their children about school experiences (Flannagan & Perese, 1998). Working-class mothers have also been reported to make fewer references to sophisticated concepts, such as affect and causality, in general conversations with their children, but to use more sophisticated language during attempts to influence their children’s behavior (Brophy, 1971; Sigel, McGillicuddy-DeLisi, & Johnson, 1980). Still other studies have reported no SES differences in mothers’ emotion references, mothers’ talk about causal aspects of emotions, or their discussions of emotions (Eisenberg, 1999; Garner, 2006). These discrepant findings may be due in part to small sample sizes, variations in the samples by SES, ethnicity, and children’s ages, and the context in which emotion language was observed.

Although virtually unexplored, ecological systems theory and empirical research suggest that ethnicity and markers of social class (e.g., income) might interact to predict mothers’ emotion talk. Mothers operate within the larger macrosystem, and structures within this system (e.g., cultural/ethnic values and social class) can interact to influence mothers’ behaviors. For example, Mexican American middle-class dyads and European American working-class dyads have been reported to have similar rates of emotion talk (Eisenberg, 1999). Additionally, African American fathers with higher-income use higher rates of negative emotion talk, whereas there is no association for non-African American fathers (Garrett-Peters, Mills-Koonce, Zerwas, Vernon-Feagans, & Cox, in preparation). In the present study, we will explore the potential influence of the social context interaction (i.e., ethnicity × income) on mothers’ emotion talk.

Child Characteristics: Temperamental Distress, Attention, and Gender

Temperamental distress and attention

Characteristics inherent in the child, such as child temperament, are thought to influence maternal behaviors in a variety of contexts (Rothbart & Bates, 1998), including mother-child discourse. Researchers have recently demonstrated associations between child temperament and the emotional content of mother-child discourse. Mothers who perceive their children to be high in negative reactivity are reported to be more elaborative during reminiscing and more likely to discuss negative emotions when discussing past events (Laible, 2004). Given these findings, it is possible that mothers might modify the content of emotion talk based on their perceptions of their infant’s distress tendencies. For example, mothers who perceive their infants to be easily distressed may be more inclined to talk to their infants about emotions, and particularly negative emotions, as a means to help the infant’s regulation of emotion. Additionally, these mothers may reference the infant’s own previous distress and negativity more frequently.

Infant attention might also promote more maternal emotion talk in the picture book context. Laible (2004) found that mothers use more elaboration in emotional discourse about their children’s past behavior when their children are more inclined toward self-regulation and attention. Thus, infants who demonstrate greater attention during the picture book session are likely to elicit more maternal emotion talk.

Gender

Although previous studies of mother-infant interaction have examined the role of gender in mothers’ emotional expressions to their infants (Malatesta & Haviland, 1982), few studies have investigated the influence of infant gender on mothers’ emotion language. Several studies of older children report differential rates of emotion references, explanations, and labels in conversations with girls and boys (Adams, Kuebli, Boyle, & Fivush, 1995; Cervantes & Callanan, 1998; Eisenberg, 1999; Flannagan & Perese, 1998; Fivush, 1989; Kuebli & Fivush, 1992; Kuebli, Butler, & Fivush, 1995). In general, these studies suggest that parents speak more frequently about emotions with their daughters than with their sons. Still other studies have reported no gender differences in maternal emotion talk (Brock, 1993; Cervantes, 2002; Dunn, Brown, Slomkowski, & Tesla, 1991; Fivush & Wang, 2005). In a meta-analysis of gender socialization studies covering infancy to five years, Lytton and Romney (1991) concluded that the differential treatment of girls and boys decreases with child age. Thus, one might expect that parental pressure for the socialization of gender and emotion occurs very early in development. Yet, it is not known whether these pressures are exerted as early as infancy in the form of maternal emotion language.

Social context

Social context might also moderate associations between child characteristics and maternal emotion language. For example, mothers from certain ethnic groups and mothers with lower family income have been found to report more difficult temperamental characteristics in their children (Pomerleau, Sabatier, & Malcuit, 1998; Lengua, 2006). However, few, if any, studies have examined whether ethnic and social class variations in maternal perceptions of child characteristics influence mothers’ behaviors toward their children. In the present study, we examine whether associations between child characteristics (i.e., distress, attention, and gender), and mothers’ emotion talk differ as a function of our social context variables (i.e., ethnicity and income).

Maternal Qualities: Maternal Knowledge of Infant Development and Parenting Style

Maternal knowledge of infant development

In addition to parenting, maternal knowledge and expectations about children’s developmental competencies influence the type of environments mothers provide for their infants, including the extent to which they talk, read, and tell stories to their infants (MacPhee, 1981; McGillicuddy-DeLisi, 1982). Mothers who have better knowledge of child development have been found to interact more positively with their children and to provide more appropriate learning environments (Fry, 1985; Miller, 1998). To date, there is remarkably little understanding of the associations between maternal knowledge and emotion socialization practices, such as the discussion of emotion.

Parenting style

Research suggests that mothers’ style of parenting and interacting with their infants may provide an important context for examining maternal emotional discourse. For example, Goldberg, Mackay-Soroka, and Rochester (1994) found that mothers of securely attached infants referred to both positive and negative emotions in their conversations. In contrast, mothers of infants with insecure-avoidant or insecure-resistant attachments were unlikely to comment about emotions in general. However, when they occurred, comments about emotions were limited to positive emotions for mothers of avoidant infants and negative emotions for mothers of resistant infants. Research also suggests that discourse about negative emotions (and other sensitive issues) is more frequent and more open in secure dyads and that mothers of secure children are more likely to initiate both positive and negative emotional themes in conversations (Farrar, Fasig, & Welch-Ross, 1997; Laible & Thompson, 1998). In support, attachment security has been found to be positively associated with more elaborative emotional conversations and increased rates of negative emotion talk during reminiscing about the child’s past behavior (Laible, 2004). Taken together, these findings suggest that mothers who are warm and attentive to their children’s physical and emotional needs are more likely to provide a balanced discussion of both positive and negative emotions. In contrast, mothers who are intrusive and hostile may be more likely to restrict emotional discussions to those with negative valence (Goldberg, Mackay-Soroka, & Rochester, 1994).

The social contexts of culture and social class may also moderate the effects of maternal qualities on parenting practices. For example, in the context of high socioeconomic challenge, specific parenting styles (e.g., positive engagement) may be particularly beneficial and serve to foster potentially more desirable parenting practices (e.g., talk about emotions). Additionally, associations between maternal knowledge and parenting behaviors have been found to vary among African American, European American, and Latin American mothers (Huang, Caughy, Genevro, & Miller, 2005). Similarly, associations between parenting styles and child behaviors have been shown to vary among African American and European American samples (Ispa, Fine, Halgunseth, Harper, Tobinson, Boyce, Brooks-Gunn, & Brady-Smith, 2004). Yet we know little about whether associations between parenting styles and mothers’ own behaviors vary among different ethnic groups or vary as a function of other social context variables.

The Present Study

In the present study, we adopted a multivariate ecological systems framework (Belsky, 1984; Bronfrenbrenner & Morris, 1998; Lerner, Rothbaum, Boulos, & Castellino, 2002) to examine the associations of social context variables (i.e., income and ethnicity), child characteristics (i.e., temperamental distress, attention, and gender), and maternal qualities (i.e., parenting style and knowledge of infant development) with maternal positive and negative emotion talk to infants, in an ethnically diverse, predominantly low-income sample. Specific predictions were that (1) income (which was used as a proxy for SES) would be inversely associated with positive and negative maternal emotion language, (2) African American mothers would be more likely to use positive and negative emotion language, (3) maternal report of infant temperamental distress and observed infant attention during the task were hypothesized to be positively associated with both positive and negative emotion language, (4) mothers were expected to talk more frequently about emotions with their daughters than with their sons, (5) maternal knowledge of infant development would be associated with higher rates of positive and negative emotion language, (6) maternal positive engagement would be positively associated with the use of positive and negative emotion language, (7) maternal negative intrusiveness would be associated with negative, but not positive, emotion language, and (8) income and ethnicity may moderate associations between the child level and parent level variables and mothers’ positive and negative emotion talk.

METHODS

Sample and Design

The Family Life Project (FLP) was designed to study families who live in two of the four major geographical areas of high rural poverty among children (Dill, 1999). Specifically, three counties in eastern North Carolina (NC) and three counties in central Pennsylvania (PA) were selected to be indicative of the Black South and Appalachia, respectively. The FLP adopted a developmental epidemiological design in which sampling procedures were employed to recruit a representative sample of 1292 children whose mothers resided in one of the six counties at the time of the child’s birth. (For a complete description of sampling and recruitment procedures see Vernon-Feagans, Pancsofar, Willoughby, Odom, Quade, & Cox, 2008) All families completed a home visit at two months of child age, at which point they were formally enrolled in the study. The current analyses are based on 1111 respondents who (1) were interviewed at home visits when target children were approximately six to eight months of age and (2) completed a videotaped picture book task that allowed for quality transcription and coding.

Of the 1111 participant families in the current analyses, nearly all (99.8%) of the primary caregivers were female, and 99.3% were biological mothers of the children. The remaining primary caregivers included one foster parent, six grandparents, and one other adult relative. Fifty-nine percent of the sample resided in NC and 41% in PA. Approximately 40% of primary caregivers were African American, the vast majority of whom resided in NC. Nearly half of all caregivers were married and living with their spouse (48%). An approximately equal number of caregivers were single (46%). The remaining 6% of caregivers were separated, divorced, or widowed. Finally, on average, four persons lived in each household, with a mean income-to-needs (income/needs) ratio of 1.83 (SD = 1.72) (an income/needs ratio of 1.0 corresponds to the federal poverty line). Because the overwhelming majority of caregivers were biological mothers, we will refer to these caregivers as mothers in the rest of this paper.

Procedures

The current data were collected at a home visit conducted at two months of child age and at one of two home visits at seven months of child age. The first of the two seven-month home visits was typically scheduled close to the child’s seven-month birthday; the second visit was usually two to four weeks later. Home visits consisted of two research assistants conducting interviews, administering questionnaires, and videotaping mother-child interactions, including picture book and free-play interactions.

Measures

Demographic data

During the interview portion of the home visits, detailed information was gathered on household composition, ethnicity, and demographics regarding education and employment of household members. Regarding household income, the FLP adopted the approach taken by Hanson, McLanahan, and Thomson (1997) and based household income on anyone who resided in the household, not simply those people related by blood, marriage, or adoption. Individuals were considered to be co-residents if they spent three or more nights per week in the baby’s household. Using this information, the total annual household income was divided by the federal poverty threshold for a family of that size and composition (thresholds varied, based on number of adults and children) to create the income/needs ratio calculated using the 2004 poverty threshold values. (Income/needs ratio was mean-centered in regression analyses, but descriptive statistics are reported for the unadjusted, true values.)

Child attention

During the picture book task, a trained research assistant observed and coded infant attention to task using the Early Attention to Reading System (EARS; Feagans, Kipp, & Blood, 1994). The research assistant used a laptop computer that was programmed to receive observational codes every five sec. These codes reflected whether the infant was attending to the book, the mother reading the book, or whether the infant was not attending to the book or mother. Two categories of infant behaviors were used for the infant attention to book session variable: the infant’s attention directed toward the book and the infant’s attention directed toward the mother. Because the length of book reading varied somewhat from infant to infant, all the sums of raw frequencies of the categories were changed to proportions to be used in analyses. Cohen’s kappas for inter-rater reliability ranged from .73 to .85 and averaged .79.

Child distress

Selected subscales of the revised version of Rothbart’s Infant Behavior Questionnaire (IBQ-R) (Gartstein & Rothbart, 2003) were administered to mothers during one of the seven-month home visits. A seven-point Likert scale ranging from never (1) to always (7) was used to rate the frequency with which the child exhibited a variety of behaviors over the previous two weeks. In the current study, the two child distress subscales were of interest. Distress to novelty (16 items) and distress to limitations (16 items) were averaged to produce a score for each of the subscales. Alphas were .87 for distress to novelty and .74 for distress to limitations. These subscales were significantly correlated, r (1109) = .37, p < .001, and a composite score, indicating child distress, was created by taking the mean score of the two individual subscales (see also Hane, Fox, Polak-Toste, Ghera, & Guner, 2006). Internal consistency for the child distress composite was .85.

Knowledge of infant development inventory

To assess mothers’ knowledge of typical child development and parenting of infants, an abbreviated 20-item version of the Knowledge of Infant Development Inventory (KIDI) (MacPhee, 1981) was used. This measure was administered to the mother at the two-month visit. Responses to KIDI items are scored as correct, incorrect, or not sure. An Accuracy score was calculated, which corresponds to the proportion of correct answers out of those attempted. Information on test–re-test reliability was collected by administering the KIDI two weeks apart, to a sample of 58 mothers in North Carolina, yielding a coefficient of .92. The internal consistency (alpha) of the KIDI for the sample was .63.

Maternal positive engagement and negative intrusiveness

To examine maternal behavior during play interactions with infants during the home visit, dyads were seated on a blanket, and the mother was instructed to interact with her child as she normally would if she had 10 free min during the day. For this free-play interaction, a standard set of toys was placed on the blanket for the mother and child to use. The task lasted 10 min and was recorded using a DVD camcorder for later coding.

Free-play interactions were coded by independent coders who were unaware of the study’s hypotheses. Coders were trained to reliability, using selected videorecorded free-play episodes that had been previously coded by criterion coders. Approximately 30% of the parent codes were double-coded, which means that the final scores were reached by consensus between two coders. Each coding pair maintained an inter-rater reliability rating of .80 or above.

Seven subscales were used to evaluate maternal behavior during the free-play task. The following qualitative ratings have been used in previous studies to assess the quality of parent-child interaction during the 10-min free-play sessions (NICHD Study of Early Child Care, 1999) and include sensitivity/responsiveness, detachment/disengagement, positive regard, intrusiveness, animation, stimulation of development, and negative regard. Coders rated each of these areas on a five-point Likert scale ranging from not at all characteristic (1) to highly characteristic (5). Factor analyses indicated two overall composite variables. Maternal positive engagement was created by summing the scale scores for positive regard, stimulation of development, animation, and detachment/disengagement (reverse-scored). Maternal negative intrusiveness was created by summing the scale scores for intrusiveness, negative regard, and sensitivity (reverse-scored). For the positive engagement composite, the average intra-class correlation was .87; for the negative intrusiveness composite, .80.

Maternal positive and negative emotion talk

Maternal emotion language data were obtained from a picture book task that was administered and videotaped at one of the seven-month home visits. The mother was asked to sit in a comfortable chair or couch with her child and was given the book Baby Faces (Baby Faces, 1998). This wordless picture book contains a picture of a baby face on each page, with each baby showing a different emotion. The racial/ethnic backgrounds of the baby faces are quite diverse. The mother was given the book before the session began so she could look through the book before she did so with her infant. She was instructed to go through the book with her infant and to let the research assistant know when she was finished. Thus, the time of the picture book session varied considerably. The research assistants were told to end the session after 10 minutes if the mother had not signaled she was finished at that point. The mother wore a high quality wireless microphone, and the session was recorded with a DVD camcorder.

The structured picture book task has been used previously with success, to elicit satisfactory rates of emotion language from low-income mothers (Garner, Jones, Gaddy, & Rennie, 1997), and it is a common activity for middle- and low-income families (McCormack & Mason, 1983, cited in Garner, Jones, Gaddy, & Rennie., 1997; Payne, Whitehurst, & Angell, 1994). Additionally, relative to naturalistic mother-child conversations, a structured picture book task can provide a rich set of information about mothers’ emotion socialization behaviors (Beeghly, Bretherton, & Mervis, 1986), and it is thought to provide a context that promotes mothers’ emotion language, especially for mothers who rarely discuss emotions with their children (Zahn-Waxler, Ridgeway, Denham, Usher, Cole, & Emde, 1993).

Mothers’ language during the picture book interaction was transcribed using the Systematic Analysis of Language Transcripts (SALT) software (Miller & Chapman, 1991). Highly trained research assistants transcribed the language directed to the child during the session. Coders were trained by a master coder to identify emotion talk in mother discourse. Emotion talk was divided into positive and negative valences. Positive emotion talk was identified as any remark made by the mother referencing or labeling a positive emotion in the picture book (e.g., “She’s a happy baby, isn’t she?”) or as referencing the child’s previous positive emotional experience (e.g., “You’re usually a happy baby, too”). Negative emotion talk was identified as remarks made by the mother referencing or labeling a negative emotion in the picture book or referencing the child’s previous negative emotional experience. Intra-class correlations for trained coders ranged from .84 to .87 for positive emotion talk and .91 to .96 for negative emotion talk. Because the length of picture book session varied somewhat from child to child, raw frequencies of emotion talk were divided by time to create rates of positive and negative emotion talk per min.

Covariates

Covariates included maternal educational attainment, maternal age, child age, and location of residence. Maternal education was included as a covariate because maternal education has been found to be positively associated with maternal language input in the current sample (Vernon-Feagans, Pancsofar, Willoughby, Odom, Quade, & Cox, 2008). Maternal age was included, to control for mothers’ experience with children. Child age was included, to control for the range in child age at the time of assessment, which was due largely to the transient nature of our low-income families. Finally, location of residence was included to address a potential confound with ethnicity given that the overwhelming majority of African American families resided in NC.

RESULTS

Descriptive Statistics

Descriptive statistics for the variables used in the analysis are presented in Table 1. Of the 1111 maternal respondents included in the analysis sample, 40% were African American, and 60% were non-African American. Non-African American respondents were slightly older than African Americans. There were ethnic differences in the distribution of income/needs ratio, with African Americans having a smaller mean and less variance than non-African Americans. Educational attainment was slightly higher for non-African Americans, on average. The majority of the sample was located in rural, eastern North Carolina, and the other respondents were located in rural, central Pennsylvania. The mean age for the child sample at the time of interview was 7.7 months, and there was relatively little variance in child ages. African American children were, on average, slightly older than non-African American children.

TABLE 1.

Descriptive Statistics of Analysis Variables (Stratified by Race/Ethnicity)

| Full sample (N = 1111) |

Non-African American (n = 662) |

African American (n = 449) |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | M | SD | Min | Max | M | SD | Min | Max | M | SD | Min | Max |

| Outcomes | ||||||||||||

| Positive emotion talk | .93 | .79 | .00 | 5.54 | .92 | .74 | .00 | 4.00 | .96 | .87 | .00 | 5.54 |

| Negative emotion talk | 1.40 | 1.00 | .00 | 6.67 | 1.33 | .91 | .00 | 5.14 | 1.50 | 1.11 | .00 | 6.67 |

| Maternal demographics | ||||||||||||

| Income/needs ratio | 1.84 | 1.72 | .00 | 16.49 | 2.35 | 1.90 | .00 | 16.49 | 1.09 | 1.02 | .00 | 7.07 |

| Age | 26.41 | 6.01 | 14.70 | 58.20 | 27.38 | 5.93 | 15.68 | 50.04 | 24.99 | 5.83 | 14.70 | 58.20 |

| Location (PA) | .41 | .49 | .00 | 1.00 | .67 | .47 | .00 | 1.00 | .04 | .19 | .00 | 1.00 |

| Less than HS graduation | .19 | .40 | .00 | 1.00 | .16 | .36 | .00 | 1.00 | .25 | .43 | .00 | 1.00 |

| HS graduation/GED | .66 | .47 | .00 | 1.00 | .63 | .48 | .00 | 1.00 | .71 | .46 | .00 | 1.00 |

| Some college | .15 | .35 | .00 | 1.00 | .22 | .41 | .00 | 1.00 | .04 | .20 | .00 | 1.00 |

| Child characteristics | ||||||||||||

| Age (months) | 7.70 | 1.45 | 5.03 | 15.38 | 7.27 | 1.36 | 5.03 | 13.44 | 8.35 | 1.34 | 5.55 | 15.38 |

| Attention | .78 | .19 | .00 | 1.00 | .80 | .17 | .12 | 1.00 | .76 | .20 | .00 | 1.00 |

| Distress | 3.13 | .75 | 1.34 | 6.53 | 2.92 | .68 | 1.34 | 5.34 | 3.46 | .74 | 1.41 | 6.53 |

| Gender (male) | .50 | .50 | .00 | .00 | .50 | .50 | .00 | 1.00 | .51 | .50 | .00 | 1.00 |

| Maternal qualities | ||||||||||||

| Knowledge of development | 16.26 | 2.50 | 7.00 | 20.00 | 17.05 | 2.23 | 7.00 | 20.00 | 15.09 | 2.41 | 8.00 | 20.00 |

| Positive engagement | 2.90 | .79 | 1.00 | 4.80 | 3.19 | .76 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 2.60 | .83 | 1.00 | 4.75 |

| Negative intrusiveness | 2.41 | .77 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 2.48 | .59 | 1.00 | 4.67 | 3.05 | .69 | 1.67 | 5.00 |

With the exception of the emotion talk dependent variables, all assessment variables (child attention, child distress, knowledge of infant development, positive engagement, and negative intrusiveness) were mean-centered in regression analyses; however, in all cases, descriptive statistics are presented for the uncentered, true values. The full sample mean number correct on the 20-item knowledge of infant development inventory was 16.25, with African Americans having slightly lower values than non-African Americans. Proportion correct in the current sample using the abbreviated version of the KIDI was 81%, which is identical to that found in a largely European American sample from varied social class backgrounds (Bornstein & Bradley, 2003). However, this proportion is somewhat higher than that reported in other studies and in a reference group of mothers, and somewhat lower than in a reference group of developmental psychologists and pediatricians (Huang, Caughy, Genevro, & Miller, 2005; MacPhee, 1981). The mean for the positive engagement index of maternal behavior was 2.90 for the full sample, and African Americans had slightly lower values than non-African Americans. Conversely, values of the negative intrusiveness index of maternal behavior were higher among African Americans than non-African Americans, with a full sample mean of 2.41. Regarding assessed child characteristics, the mean proportion of time in which the children’s attention was on task was .78 in the full sample, with negligible ethnic differences. Finally, the mean of the scale of child distress was 3.13 for the full sample, with African American mothers giving higher ratings than non-African Americans. The child distress mean for the full sample was comparable to that reported in a low-risk population of infants (see Hane, Fox, Polak-Toste, Ghera, & Guner, 2006).

Contributors to Maternal Emotion Talk: Zero-Order Correlations

The zero-order correlations for all analysis variables are presented in Table 2. More frequent positive emotion talk by mothers was significantly associated with higher household income/needs ratio, lower child distress, and greater knowledge of development and maternal positive engagement. More frequent negative emotion talk by mothers was significantly associated with African American ethnicity, and greater maternal positive engagement and negative intrusiveness. Although positive emotion talk and negative emotion talk were significantly and positively associated, it is important to examine each criterion separately, given previous research indicating that parenting quality can influence whether mothers’ discussions of positive and negative emotions are balanced or skewed (Farrar, Fasig, & Welch-Ross, 1997; Goldberg, Mackay-Soroka, & Rochester, 1994; Laible, 2004; Laible & Thompson, 1998). Before HM regression analyses were conducted, univariate distributions of the outcome variables, positive and negative emotion talk, were checked for normalcy and outliers. Residuals were also examined, and the variables were assessed for multivariate outliers.

TABLE 2.

Correlations Among Variables Predicting Maternal Positive and Negative Emotion Talk (N = 1111)

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal emotion talk | ||||||||||

| 1. Positive emotion talk | – | |||||||||

| 2. Negative emotion talk | .51** | – | ||||||||

| Maternal social context | ||||||||||

| 3. Ethnicity | .03 | .08** | – | |||||||

| 4. Income/needs ratio | .14** | .05 | −.36** | – | ||||||

| Child characteristics | ||||||||||

| 5. Attention | −.02 | .02 | −.12** | .03 | – | |||||

| 6. Distress | −.07* | −.04 | .35** | −.27** | −.05 | – | ||||

| 7. Gender (male) | −.01 | −.01 | .00 | .04 | −.08** | −.10** | – | |||

| Maternal qualities | ||||||||||

| 8. Knowledge of development | .10** | .06 | −.38** | .33** | .01 | −.27** | .00 | – | ||

| 9. Positive engagement | .25** | .19** | .35** | .32** | −.06* | −.23** | −.02 | .34** | – | – |

| 10. Negative intrusiveness | −.02 | .10** | .41** | −.33** | −.06 | .23** | .05 | −.29** | −.34** | |

p < .05.

p < .01.

Contributors to Maternal Emotion Talk: Hierarchical Multiple Regression

Model building

To investigate the direct and interactive influences of social context, child characteristics, and maternal qualities on early maternal emotion talk, we employed hierarchical multiple regression with predictor variables entered in a blockwise fashion. Order of predictor variable entry was based on ecological systems theory (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 1998), with more distal factors entered first, followed by successively more proximate factors (see also Bornstein, Hendricks, Hahn, Haynes, Painter, & Tamis-LeMonda, 2003). Thus, for both positive and negative emotion talk outcomes, we began by examining the effects of our social context variables of household income/needs ratio and maternal ethnicity (Model 1). In the second model (Model 2), we analyzed the effects of child characteristics, controlling for social context, to investigate the possibility that aspects of the child’s behavior and temperament may evoke maternal emotion talk. In the third model (Model 3), we examined potential effects of maternal qualities on maternal emotion talk, while controlling for social context and child characteristics. In the fourth model (Model 4), we tested for possible moderation of social context effects by maternal qualities, retaining significant main effects from Model 3 and introducing interactions between the significant social context variables and the significant maternal quality variables. The final, trimmed model (Final Model) includes only the significant main effects and interactions.

Positive emotion talk

As seen in Table 3, maternal social context as a block significantly predicted positive emotion talk, F(7, 1103) = 6.09, p < .001, with unique associations for income/needs ratio and ethnicity. Both higher income/needs ratio and African American ethnicity were shown to be associated with higher levels of positive emotion talk. Cumulatively, the social context variables explained 3.7% of the outcome variance. Child characteristics as a block were not significantly predictive of positive emotion talk, F(3, 1100) = 1.36, ns. No individual variable (i.e., attention, distress, and gender) was uniquely related to positive emotion talk, and the inclusion of these variables resulted in little improvement in model fit (R2 = .041). Maternal qualities were significant as a block, F(3, 1097) = 24.77, p < .001. Maternal positive engagement was a significant positive predictor of positive emotion talk. The addition of maternal quality variables resulted in a relatively large increase in variance (i.e., 6.1%). No interactions were found to be significant, but all main effects were robust. In the trimmed Final Model, African American mothers were again shown to have higher levels of positive emotion talk than their non-African American counterparts (B = .25), as were mothers with higher household income (B = .07) and those with higher levels of positive engagement (B = .26). Trimming the model of all nonsignificant main and interaction effects resulted in only a minor drop in R2 from Model 4 to the Final Model (9.9% and 9.4%, respectively), and the adjusted R2 of these models were identical (adj. R2 = .089).

TABLE 3.

Summary of Hierarchical Regression Analysis Predicting Maternal Positive Emotion Talk

| Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 3 |

Model 4 |

Final Model |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor variables | B | SE B | B | SE B | B | SE B | B | SE B | B | SE B |

| Social context | ||||||||||

| Ethnicity (African American) | .14 | 2.22* | .16 | 2.41* | .26 | 3.81** | .22 | 3.23** | .25 | 3.86** |

| Income/needs ratio | .07 | 3.84** | .07 | 3.80** | .06 | 3.43** | .08 | 3.86** | .07 | 4.30** |

| Child characteristics | ||||||||||

| Attention | −.18 | −.72 | .14 | .55 | ||||||

| Distress | −.06 | −1.83 | −.05 | −1.39 | ||||||

| Gender (male) | −.05 | −1.15 | −.03 | −.71 | ||||||

| Maternal qualities | ||||||||||

| Knowledge of development | .32 | 1.51 | ||||||||

| Positive engagement | .26 | 8.24** | .29 | 6.83** | .26 | 8.86** | ||||

| Negative intrusiveness | .07 | 1.92 | .00 | .09 | ||||||

| Moderation of social context | ||||||||||

| Ethnicity × income | −.01 | −.29 | ||||||||

| Ethnicity × positive engagement | −.03 | −.41 | ||||||||

| Income × positive engagement | .12 | 1.50 | ||||||||

| Ethnicity × negative intrusiveness | .01 | .44 | ||||||||

| Income × positive engagement | .04 | 1.55 | ||||||||

| R2 | .037 | .041 | .102 | .099 | .094 | |||||

p < .05.

p < .01.

Control variables included maternal age and education, child age, and location of residence.

Negative emotion talk

Table 4 presents regression models examining contributors to maternal negative emotion talk. The effects of social context block were significant, F(7, 1103) = 4.73, p < .001. Income/needs ratio had a significant positive association with negative emotion talk, and the block as a whole explained a modest amount of outcome variance (R2 = .027). Child characteristics were not significant as a block, F(3, 1100) = 1.53, ns, and no individual variable in the block was a significant predictor. Maternal qualities were significant as a block, F(3, 1097) = 29.96, p < .001. All three maternal qualities were significant, and they added substantial improvement in model fit vs. the former model (R2 = .106 and .031, respectively). All three individual variables (i.e., knowledge of infant development, positive engagement, and negative intrusiveness) were positive predictors of negative emotion talk. In our examination of potential moderation of social context effects by maternal qualities, all significant main effects were robust, with the exception of child attention (see discussion below), and several significant interactions were indicated, F(9, 1092) = 2.94, p < .01. Lastly, the trimmed Final Model indicated six significant main effects and three interactions. As was the case for positive emotion talk, African American ethnicity and household income/needs ratio were both positively associated with negative emotion talk. Thus, African American mothers made .21 more negative emotion references per min than their non-African American counterparts, and each unit increase in income/needs ratio was associated with a .06 increase in the rate of negative emotion talk. Knowledge of infant development also had a significant positive association with negative emotion talk; however, as described below, the inclusion of an ethnicity × knowledge of infant development interaction effect revealed this positive association to be present only in non-African American mothers. As expected, both maternal positive engagement and negative intrusiveness were positively associated with negative emotion talk, with each unit increase associated with increases of .33 and .21 references to negative emotion per min, respectively.

TABLE 4.

Summary of Hierarchical Regression Analysis Predicting Maternal Negative Emotion Talk

| Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 3 |

Model 4 |

Final Model |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor variables | B | SE B | B | SE B | B | SE B | B | SE B | B | SE B |

| Social context | ||||||||||

| Ethnicity (African American) | .12 | 1.49 | .15 | 1.83 | .25 | 2.97* | .21 | 2.45* | .21 | 2.61** |

| Income/needs ratio | .05 | 2.14* | .04 | 2.03* | .04 | 1.90 | .06 | 2.00* | .06 | 2.88** |

| Child characteristics | ||||||||||

| Attention | .19 | .61 | .66 | 2.09* | −.12 | −.28 | −.06 | −.15 | ||

| Distress | −.08 | −1.76 | −.07 | −1.54 | ||||||

| Gender (male) | −.02 | −.28 | −.01 | −.21 | ||||||

| Maternal qualities | ||||||||||

| Knowledge of development | .52 | 1.92 | 1.18 | 3.34** | 1.19 | 3.46** | ||||

| Positive engagement | .33 | 8.40** | .29 | 5.53** | .33 | 8.64** | ||||

| Negative intrusiveness | .23 | 4.72** | .16 | 2.34* | .21 | 4.53** | ||||

| Moderation of social context | ||||||||||

| Ethnicity × income | −.03 | −.42 | ||||||||

| Ethnicity × attention | 1.59 | 2.33* | 1.35 | 2.20* | ||||||

| Ethnicity × knowledge of development | −1.26 | −2.33* | −1.48 | −2.97** | ||||||

| Ethnicity × positive engagement | .10 | 1.15 | ||||||||

| Ethnicity × negative intrusiveness | .12 | 1.15 | ||||||||

| Income × attention | .11 | .52 | ||||||||

| Income × knowledge of development | .28 | 1.34 | ||||||||

| Income × positive engagement | −.05 | −2.07* | −.06 | −2.73** | ||||||

| Income × negative intrusiveness | .03 | .96 | ||||||||

| R2 | .027 | .031 | .106 | .124 | .120 | |||||

p < .05.

p < .01.

Control variables included maternal age and education, child age, and location of residence.

Moderation of social context effects on negative emotion talk

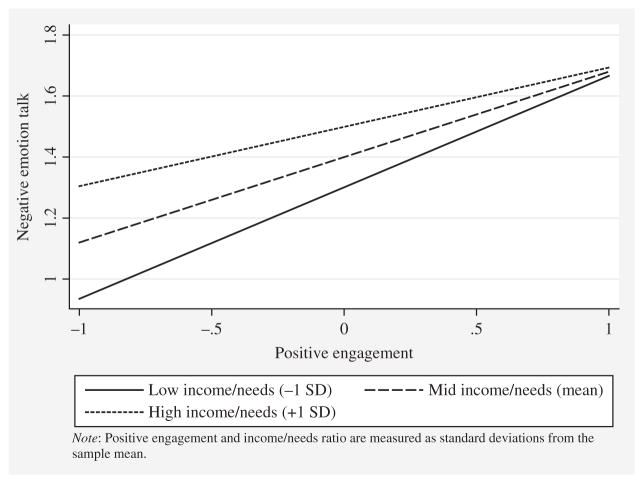

Of nine potential interaction effects testing moderation of social context, three were significant. The coefficient of the first significant interaction, income/needs × positive engagement, equals −.06. Thus, both income and positive engagement have positive direct effects, but these effects are nonadditive (see Fig. 1). One potential explanation is that income and positive engagement may operate via the same underlying mechanism, such that an increase in one variable attenuates the positive effect of the other. Thus, the cumulative effects of the two variables plateau at extreme values. The inclusion of an ethnicity × child attention interaction fully negates the main effect of child attention. As shown in Fig. 2, child attention was associated with increases in negative emotion talk only among African American mothers, and this effect is quite large, given the interaction coefficient equal to 1.35. Thus, non-African American mothers’ use of negative emotion talk is not associated with child attention. In contrast, African American mothers seem to respond to attentive children, capitalizing on opportunities in which the child may be particularly receptive to discuss negative emotions. The final significant interaction in the negative emotion talk analysis is the negative effect of African American ethnicity × knowledge of infant development illustrated in Fig. 3. The interactive effect of African American ethnicity × knowledge of infant development is negative (equal to −1.48), but both the main effects of African American ethnicity and knowledge of infant development are positive. In summary, knowledge of infant development has a very large positive association with the discussion of negative emotions among non-African American mothers, but has little effect among African American mothers. Thus, negative emotion talk to infants is fairly common among African American mothers, whereas among non-African American mothers, it is strongly influenced by levels of knowledge of infant development. As shown in Fig. 3, only non-African American mothers with extremely high levels of knowledge of infant development approached the heightened levels of negative emotion talk observed among the African American mothers.

FIGURE 1.

Interaction effect of maternal positive engagement and income/needs ratio.

FIGURE 2.

Ethnic differences in associations between child attention and negative emotion talk.

FIGURE 3.

Ethnic differences in associations between knowledge of development and negative emotion talk.

Although models for both positive and negative emotion talk were significant, the overall explanatory power of the predictors is modest for both models given the small R squares. Further, considering the effect sizes relative to the standard deviation of the predictors indicates that the individual effect sizes are also generally modest, with the exception of fairly large effects of positive engagement.

DISCUSSION

We examined social context variables and maternal and child characteristics that are associated with mothers’ positive and negative emotion talk to infants in an ethnically diverse, low-income sample. To our knowledge, this is one of the first investigations to examine very early correlates of mothers’ emotion talk in an ethnically diverse high poverty sample—an important but largely understudied population. Results from the present study offer unique insight into the characteristics of mothers who engage in emotion talk with very young children. In general, the evidence provides support for effects of social context and maternal qualities, but not child effects.

As expected, ethnicity proved to be an important indicator of early maternal emotion talk. Consistent with our hypotheses, African American mothers described both positive and negative emotions to their infants more frequently than did non-African American mothers. Patterns also emerged suggesting a moderating effect of ethnicity on other predictors of negative emotion talk. As seen in Fig. 2, African American mothers demonstrated relatively constant rates of negative emotion talk, and consistently higher rates than their non-African American counterparts, regardless of their knowledge of infant development. In contrast, for non-African American mothers, high rates of negative emotion talk were present only when mothers also had greater knowledge of infant development. It appears that early negative emotion talk is more common among African American mothers than among non-African American mothers. Additionally, for African American mothers only, infant attention to task was associated with more frequent discussion of negative emotion (see Fig. 3). Infant attention may have evocative effects for African American mothers such that these mothers take advantage of their infant’s attentive state and use this as an opportunity to discuss negative emotions with their children. Interestingly, research on general language input suggests that African American mothers tend to use fewer verbalizations and fewer questioning behaviors with their children relative to other ethnic groups (Anderson-Yockel & Haynes, 1994; de Cubas & Field, 1984; Heath, 1983). That this pattern is not replicated and is, in fact, reversed in the context of emotion language is noteworthy. In particular, this pattern underscores the potential salience of emotional stimuli among African American mothers, which may result in a greater emphasis on emotional discourse with their children.

Greater emotional discourse among African American mothers may be explained within the framework of Boykin’s (1983, 1986) Triple Quandary Theory, which attempts to account for three types of cultural experiences for African American families and their children: the mainstream experience, the minority experience, and the Afro-cultural experience. One possible explanation for these findings highlights unique aspects of African American culture, or the Afro-cultural experience. The traditional cultural emphases of African Americans include interdependence, extended family, emotional expression, and oral and aural modes of communication (Boykin, 1986; Harrison, Wilson, Pine, Chan, & Buriel, 1990; White & Parham, 1996). Communication styles of African American mothers and their children are described as reflecting a social-emotional orientation, which facilitates relations and the negotiation of conflict between group members (Blake, 1993). Greater emotional discourse among African American mothers may reflect this underlying emphasis on the importance of emotional expression and interdependence among group members within the African American culture.

Another possible explanation of greater emotional discourse among African American mothers highlights the role of the minority experience, which refers to coping strategies and defense mechanisms that are developed in response to oppression and social stratification. Researchers suggest that a history of slavery and repression has led African Americans to place a premium on emotional self-control, perhaps out of concern for censure and retaliation by members of the majority group (Consendine & Magai, 2002). African American mothers’ discussion of emotion in the context of the emotion-faces picture book may reflect this underlying psychological orientation toward emotional vigilance in a climate of prejudice and discrimination, and this may be particularly true in the rural South (i.e., North Carolina) where nearly all of the African American mothers in the present sample resided. This explanation is also consistent with current theorizing on the sociology of emotions, which emphasizes the role of sociocultural factors (e.g., social class position, institutionalized forms of racism, etc.) in shaping emotional experience (Thoits, 1989; Turner & Stets, 2005).

Previous research has shown that economic strain is associated with the use of more negative socialization behaviors, such as restrictive and controlling parenting and fewer and shorter mother-child verbal exchanges (Conger, Conger, Elder, & Lorenz, 1992; Flannagan, Baker-Ward, & Graham, 1995; Hart & Risley, 1992; Hoff-Ginsberg, 1991). Our findings indicate that stress associated with economic strain might also affect the content of mothers’ early emotion dialogues. As expected, relative to higher-income mothers, lower-income mothers talked less to their infants about positive and negative emotions during the picture book task. Other studies have reported that working-class dyads talk about emotions more than middle-class dyads in contexts of disputes and discipline (Eisenberg, 1996), even though they generally talk about causality less often than their middle-class counterparts (e.g., Brophy, 1971; Sigel, McGillicuddy-DeLisi, & Johnson, 1980). Results from the present study are consistent with previous work indicating that lower SES mother-child dyads make fewer emotional references in emotionally neutral contexts (e.g., naturalistic conversations about school) (Flannagan & Perese, 1998) and extend these findings to a structured interaction involving the presence of salient emotional stimuli (i.e., pictures of emotion faces). The psychological resources of low-income mothers appear to be taxed in ways that reduce their use of emotion talk, even toward very young infants and even in the face of emotional stimuli that might otherwise elicit comment. Finally, previous research provides evidence for the presence of negative socialization behaviors in lower-income parents (Conger, Conger, Elder, & Lorenz, 1992), whereas the present results suggest that mother-child interactions in lower-income dyads may also be characterized by the absence of positive socialization behaviors (e.g., talk about emotions) very early in the child’s life.

Unexpected was the finding that temperament and gender were generally not associated with mothers’ positive or negative emotional discourse. One exception was the positive association of infant attention with negative emotion talk for African American mothers discussed earlier. Previous studies have also reported positive associations between a mother’s report of child negativity and maternal elaboration and discussion of negative emotions in older children (Laible, 2004). However, the present findings indicate that a mother’s report of infant distress does not influence maternal discourse to her infant in a picture book context. These findings suggest that positive associations between child negativity and maternal discourse may appear later in development or that this association may be context specific. For example, in the Laible (2004) study, mothers were talking about their own child’s past behavior. Consequently, mothers of highly negative children may have had more on which to comment, given that the past behaviors of highly negative children are likely to be more emotionally intense and frequent than the past behaviors of children low in negativity. Additionally, associations between child negativity and mothers’ emotional discourse may vary as a function of the referent of the emotion. Specifically, mothers of highly negative children might talk about emotions more when referring to their child’s own emotion, but not when referring to the emotions of others.

With regard to gender, mothers have been reported to differentially socialize positive and negative emotions in their infants by modifying their own emotional expressions in response to those expressed by their daughters vs. sons (Malatesta & Haviland, 1982). The nonsignificance of gender in the current study suggests that gender-differentiated emotion socialization practices among mothers of infants are not evident in maternal emotional discourse, but may be limited to other emotional behaviors (e.g., reactive expressions). Given the importance of gender in influencing maternal emotional discourse with older children (Cervantes & Callanan, 1998), it appears that mothers may socialize gender differences in emotions via discourse during specific developmental periods. More broadly, these findings point to the possibility that parents view specific emotion socialization goals (e.g., gender socialization and regulation of child distress) as more or less appropriate and specific emotion socialization strategies (e.g., discussion of emotions) as more or less efficacious, during different periods of development.

Our hypotheses regarding associations between maternal knowledge of infant development and positive and negative emotion talk were only partially supported. Knowledge of development was not associated with positive emotion talk, but predicted more negative emotion talk for non-African American mothers only. Knowledge of development was not associated with positive or negative emotion talk for African American mothers. As discussed previously, this moderating effect suggests that other parental cognitive factors, such as cultural values and parental goals and beliefs, might interact with parental knowledge to affect mothers’ emotional discourse (see also Huang, Caughy, Genevro, & Miller, 2005; Sigel & McGillicuddy-DeLisi, 2002). For non-African American mothers, greater knowledge of development leads to more discourse about negative emotions with their infants. Research with older children suggests that open discourse about negative emotions among mothers can be beneficial to their children’s emotional development, as well as to the development of a positive relationship with their children. For example, researchers have found that avoiding the discussion of negative emotions is associated with insecure-avoidant attachment relationships (Goldberg, Mackay-Soroka, & Rochester, 1994). Knowledge of development did not predict mothers’ positive emotion talk. Given the importance of regulating negative vs. positive emotions, it seems plausible that mothers with greater knowledge of development recognize the importance of discourse about negative emotions for their children’s developing emotional competencies. It is also possible that context could moderate associations between knowledge of development and emotion talk. For example, in the present study, a picture book task was used to elicit talk about others’ emotions, but for other contexts, in which talk about one’s own or the child’s emotions is elicited (e.g., narratives about emotional events), mothers with greater knowledge of development may use more emotion talk.

As predicted, maternal positive engagement in the play context was associated with more positive and negative emotion talk in the picture book context. Additionally, maternal negative intrusiveness was associated with more negative, but not positive, emotion talk. These findings resonate with several formulations of attachment theory that consider parental sensitivity, emotional support, and emotional openness as critical for the development of secure attachment (Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters, & Wall, 1978; Bretherton, 1985; Cassidy, 1998; De Wolf & van IJzendoorn, 1997; Isabella, 1993; Main, Kaplan, & Cassidy, 1985; Sroufe, 1995). Specifically, researchers have found that, relative to insecure dyads, discourse between securely attached dyads is characterized by emotional openness, elaboration, and coherence (e.g., Laible, 2004; Laible & Thompson, 1998; Thompson, Laible, Ontai, & Kail, 2003). Securely attached dyads have also been found to provide a more balanced discussion of both positive and negative emotions during conversations about emotions (Laible, 2004; Laible & Thompson, 1998). Consistent with previous research and theory, the present findings indicate that mothers who are positively engaged during play with their infants promote an emotionally open communication style very early in their children’s lives. Furthermore, the present findings indicate that mothers who are more negative and intrusive emphasize discourse about negative emotional expressions and experiences to the exclusion of positive ones very early in their children’s development.

The association of maternal positive engagement with negative emotion talk was moderated by income (see Fig. 1). Although both income and positive engagement had positive direct effects, this interaction suggests that, at higher levels of income, maternal positive engagement is not as strongly associated with negative emotion talk as it is at lower levels of income. One possible explanation for this finding is that, given the many advantages associated with higher income, the effect of any single positive support for emotion talk (e.g., maternal positive engagement) may be attenuated by the presence of other supports, rendering no single advantage paramount. Conversely, given the numerous challenges associated with low income, a single positive support (e.g., maternal positive engagement) for emotion talk may become increasingly important. The current findings suggest that the role of positive engagement in mothers’ willingness to talk about negative emotions with children may be especially important in the context of poverty.

The findings and limitations of the present study highlight many potential avenues for future research on mothers’ emotional discourse with young children. First, much of the criterion and predictor data in this study share source and/or method variance. Nearly all measures shared source variance because only mothers either provided self-report data or were observed. However, several features of this study mitigate threats to validity. For example, mothers reported knowledge of development, but emotion talk was observed. Additionally, much of our data (e.g., parenting quality and emotion language) stemmed from observations of mothers in different contexts (e.g., parent-child interaction and picture book interaction), and the coding of these observations was conducted by independent groups. The use of direct observations that were coded independently minimized concerns over shared method and source variance that might inflate associations between parenting and emotion talk when the data are gathered during the same interaction or coded by the same group. Second, it is important to recognize that distal constructs such as income and ethnicity are likely mediated by more proximal processes that influence maternal emotional discourse, as well as other emotion socialization behaviors. For example, financial stress likely mediates the association between income and mothers’ emotion talk found in the present study. Thus, future investigations should incorporate measures of more proximal variables, such as parental stress associated with low income. Furthermore, in the present study, ethnicity is defined by biological determinants. It is crucial to also consider the role of culture as defined by sociopsychological factors such as “the shared system of beliefs, attitudes, values, and behaviors, communicated from one generation to the next via language” (Matsumoto, 1993, p. 120). In this regard, interpreting ethnic differences would require identifying the psychological culture underlying the different ethnic groups and the impact of that psychological culture on emotional socialization processes (Matsumoto, 1993). Additionally, it is important to explore mothers’ emotion talk over a range of different contexts. In the present study, lower-income mothers were less likely than higher-income mothers to talk to their infants about emotions in the presence of emotional stimuli (i.e., pictures of emotion faces). However, context may moderate these effects. For example, mothers of securely attached preschoolers were less likely to discuss negative emotions in the context of storybook reading, but more likely in the context of discussing the child’s own past emotion (Laible, 2004). Similarly, working class mothers have been reported to make more emotion references in the context of trying to influence their child’s behavior (Eisenberg, 1996). Thus, discerning the function of parental communication about emotion will also be critical. If parental emotion language represents attempts to remediate children’s socioemotional deficits, rather than to clarify or teach children about emotions, there will likely be negative consequences for children’s socioemotional functioning (Eisenberg, Cumberland, & Spinrad, 1998).

Future studies should also examine different forms of mothers’ emotion talk beyond labels, such as mothers’ explanations and discussions of causes and consequences of emotions, as well as the implications of various forms of talk on children’s emotional development. In the present study, African American mothers engaged in more emotion labeling with their infants than non-African American mothers, but these early behaviors may not have any direct causal impact on children’s later emotional functioning. For example, young African American children have been found to have more difficulty explaining emotions than older African American children and European American children, both younger and older (Currenton & Wilson, 2003). These findings highlight the need for examining stability and change in different patterns of maternal emotional discourse (e.g., labeling, explaining, and so forth) across early development (see Kuersten-Hogan & McHale, 2000) and underscore the importance of parental sensitivity to children’s developing competencies. As young children advance in their sociocognitive understanding, their emotional competencies will be bolstered most by mothers whose emotion language is characterized by more sophisticated emotion talk (e.g., explanations), as opposed to the simple labeling of emotions. Additionally, it will be important to examine the consequences of potential biases in mothers’ discourse about emotions of different valences. Mothers of some insecure children have been found to focus their discourse on negative emotions, which may bias their children’s social schemas to focus on negative emotions (Belsky, Spritz, & Crnic, 1996; Laible, 2004). The potential long-term consequences of these possible cognitive processing biases on children’s socioemotional functioning are not well understood and should be explored. Furthermore, avoiding a simple “dose-response” or “more is better” explanation of parental emotion language input will be essential in future studies, because recent work has pointed to the importance of the appropriateness of mothers’ comments, as well as emotionally matched dialogues in mother-child discourse (Meins, Fernyhough, Wainwright, Gupta, Fradley, & Tuckey, 2002; Oppenheim, Koren-Karie, Sagi-Schwartz, 2007). Of equal importance will be an examination of the manner in which mothers deliver emotional information to their children. For example, talking about emotions in an overwhelming or unregulated manner will likely have a negative impact on children’s emotional functioning. Finally, gains in the domain of emotion socialization will be made through an examination of multivariate influences on fathers’ emotional discourse with children, as well as how fathers’ discourse shapes children’s emotional development. Fathers have been reported to be just as likely as mothers to discuss emotions with their children when discussing past events (Fivush & Nelson, 1993). Thus, identifying characteristics of fathers who are likely to engage in emotional discourse will provide another avenue for understanding children’s socioemotional development.

Acknowledgments

Support for this research was provided by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (PO1-HD-39667), with co-funding from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The Family Life Project (FLP) Key Investigators include Lynne Vernon-Feagans, Martha Cox, Clancy Blair, Peg Burchinal, Linda Burton, Keith Crnic, Ann Crouter, Patricia Garrett-Peters, Mark Greenberg, Stephanie Lanza, Roger Mills-Koonce, Debra Skinner, Emily Werner, and Michael Willoughby. We would like to express our sincere gratitude to all of the families and children who participated in this research and to the Family Life Project research assistants. We would also like to thank Marc Bornstein and three anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments on earlier drafts of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf

This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden.

The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

Contributor Information

Patricia Garrett-Peters, Email: garrettp@email.unc.edu, Center for Developmental Science, 100 East Franklin Street, #8115, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC 27599.

Roger Mills-Koonce, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Daniel Adkins, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Lynne Vernon-Feagans, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Martha Cox, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

The Family Life Project Key Investigators, The University of North Carolina and The Pennsylvania State University.

References

- Adams S, Kuebli J, Boyle PA, Fivush R. Gender differences in parent-child conversations about past emotions: A longitudinal investigation. Sex Roles. 1995;33:309–323. [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth MDS, Blehar M, Waters E, Wall S. Patterns of attachment. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson-Yockel J, Haynes WO. Joint book-reading strategies in working-class African American and White mother-toddler dyads. Journal of Speech & Hearing Research. 1994;37:583–593. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3703.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baby faces. New York: D. K. Publishing; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Beals DE. Explanatory talk in low-income families’ mealtime conversations. Applied Psycholinguistics. 1993;14:489–513. [Google Scholar]

- Beeghly M, Bretherton I, Mervis CB. Mothers’ internal state language to toddlers. British Journal of Developmental Psychology. 1986;4:247–261. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J. The determinants of parenting: A process model. Child Development. 1984;55:83–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1984.tb00275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Spritz B, Crnic K. Infant attachment security and affective-cognitive information processing at age 3. Psychological Science. 1996;7:111–114. [Google Scholar]

- Blake IK. The social-emotional orientation of mother-child communication in African-American families. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 1993;16:443–463. [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH, Bradley RH. Socioeconomic status, parenting, and child development. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH, Haynes OM, Painter KM. Sources of child vocabulary competence: A multivariate model. Journal of Child Language. 1998;25:367–393. doi: 10.1017/s0305000998003456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH, Hendricks C, Hahn C, Haynes OM, Painter KM, Tamis-LeMonda CS. Contributors to self-perceived competence, satisfaction, investment, and role balance in maternal parenting: A multivariate ecological analysis. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2003;3:285–326. [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH, Tamis-LeMonda CS, Pascual L, Haynes OM, Painter K, Galperin C, et al. Ideas about parenting in Argentina, France, and the United States. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 1996;19:347–367. [Google Scholar]

- Boykin AW. On academic task performance and Afro-American children. In: Spencer J, editor. Achievement and achievement motives. Boston, MA: Freeman; 1983. pp. 324–371. [Google Scholar]

- Boykin AW. The triple quandary and the schooling of Afro-American children. In: Neisser U, editor. The school achievement of minority children: New perspectives. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Bretherton I. Attachment theory: Retrospect and prospect. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1985;50:3–35. [Google Scholar]

- Brock SR. An examination of the ways in which mothers talk to their male and female children about emotions. Paper presented at the Biennial Meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development; New Orleans, LA. 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfrenbrenner U, Morris PA. The ecology of developmental processes. In: Lerner RM, Damon W, editors. Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 1. Theoretical models of human development. 5. New York: Wiley; 1998. pp. 993–1028. [Google Scholar]

- Brophy JE. Mothers as teachers of their own preschool children. Child Development. 1971;41:79–94. [Google Scholar]

- Brown JR, Dunn J. Continuities in emotion understanding from three to six years. Child Development. 1996;67:789–802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy J. Attachment and object relations theories and the concept of independent behavioral systems: Commentary. Social Development. 1998;7:120–126. [Google Scholar]

- Cervantes CA. Explanatory emotion talk in Mexican immigrant and Mexican American families. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2002;24(2):138–163. [Google Scholar]

- Cervantes CA, Callanan MA. Labels and explanations in mother-child emotion talk: Age and gender differentiation. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34:88–98. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.34.1.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Conger KJ, Elder GH, Lorenz FO. A family process model of economic hardship and adjustment of boys. Child Development. 1992;63:526–541. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb01644.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Consedine NS, Magai C. The uncharted waters of emotion: Ethnicity, trait emotion and emotion expression in older adults. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology. 2002;17:71–100. doi: 10.1023/a:1014838920556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currenton SM, Wilson MN. “I’m happy with my mommy”: Low-income preschoolers’ causal attributions for emotions. Early Education and Development. 2003;14:199–213. [Google Scholar]

- de Cubas MM, Field T. Teaching interactions of Black and Cuban teenage mothers and their infants. Early Child Development and Care. 1984;16:41–56. [Google Scholar]

- Denham SA, Cook M, Zoller D. “Baby looks very sad”: Implications of conversations about feelings between mother and preschooler. British Journal of Developmental Psychology. 1992;10:301–315. [Google Scholar]

- Denham SA, Zoller D, Couchoud EA. Socialization of preschoolers’ emotion understanding. Developmental Psychology. 1994;30:928–936. [Google Scholar]