Abstract

It is proposed that people are motivated to feel hard to replace in romantic relationships because feeling irreplaceable fosters trust in a partner’s continued responsiveness. By contrast, feeling replaceable motivates compensatory behavior aimed at strengthening the partner’s commitment to the relationship. A correlational study of dating couples and 2 experiments examined how satiating/thwarting the goal of feeling irreplaceable differentially affects relationship perception and behavior for low and high self-esteem people. The results revealed that satiating the goal of feeling irreplaceable increases trust for people low in self-esteem. In contrast, thwarting the goal of feeling irreplaceable increases compensatory behaviors meant to prove one’s indispensability for people high in self-esteem.

Keywords: relationships, perceived acceptance, self-esteem

“Don’t accept a partner who wanted you for rational reasons…Look for someone who is emotionally committed to you because you are you. If the emotion moving that person is not triggered by your objective mate value, that emotion will not be alienated by someone who comes along with greater mate value than yours.”

In a Time magazine article (January 28, 2008, p. 83), Steven Pinker (2008) offered pointed advice to people searching for a committed romantic partner. Because the romantic marketplace is inherently competitive, no rational accounting process can guarantee a partner’s commitment. No matter how desirable one’s own qualities, an available and more desirable alternative could be waiting in the wings. Given this unpleasant reality, Pinker advises people searching for lasting love to select the special someone who loves them for the most irrational of reasons – someone who thinks they are essentially irreplaceable (Tooby & Cosmides, 1996).1

Being (and Becoming) Irreplaceable

Why might being irreplaceable to the partner be critical in fostering satisfying, stable relationships? A fundamental approach-avoidance conflict runs throughout romantic life: Seeking connection to a romantic partner seriously increases the risk of rejection (Murray, Holmes & Collins, 2006). This goal conflict permeates relationships because partners are interdependent in multiple ways (Kelley, 1979). Given interdependence in life tasks, personality and relationship goals, conflicts are inevitable – raising the possibility that a partner might not prove to be responsive to one’s needs over the longer term (Reis, Clark & Holmes, 2004).

To take the step of seeking connection, people need to feel protected against the risk of partner non-responsiveness and rejection (Murray et al., 2006). Trust in a partner’s continued motivation to be responsive provides this sense of psychological assurance. In ongoing dating and marital relationships, people generally only feel satisfied and committed themselves when they trust that their partner’s love and commitment, and thus responsiveness, is secure (Murray, Holmes & Griffin, 2000; Murray, Holmes, Griffin, Bellavia, & Rose, 2001). By making their own willingness to risk commitment contingent on trust in the partner’s commitment, people convey an implicit appreciation of the fact that loving and committed partners are less likely to reject or disappoint them (Bowlby, 1969; Reis et al., 2004; Rusbult & Van Lange, 2003).

This paper contends that feeling irreplaceable to one’s partner functions as a goal state in relationships because feeling irreplaceable affords trust and its attendant relationship benefits. Being of special value solves the problem being in an objective state of need creates. When something is wrong – when people are sick, distressed, or fearful – they need the aid afforded by close interpersonal ties. However, when something is wrong, people are least able to repay or reciprocate any help they receive. Tooby and Cosmides (1996) describe this adaptive problem as a “Bankers’ paradox”: People most need loans of interpersonal sacrifice and good will when they are bad credit risks. For people to survive to reproduce, these theorists reasoned that specific cognitive mechanisms needed to be in place to allow people to discriminate good from fair-weather friends. Making such discriminations involves discerning which specific others perceive one’s qualities as special because they could not imagine finding these qualities in others. Filling such a niche – that is, possessing some quality that makes one unique, and thus, valuable to one’s social ties – guarantees that others have some reason to be loyal in times of crisis (Gilbert, 2005; Reis et al., 2004; Tooby & Cosmides, 1996).

The Bankers’ paradox makes Pinker’s advice all the more pointed. To stop a romantic partner’s eyes (and feet) from wandering, people need to ensure that their partner values qualities in them that he/she could not readily find in others if he/she were to look for them. People know this implicitly. In speed-dating situations, people gravitate toward the choosy – they want to pursue relationships with suitors who find them uniquely fascinating. Suitors who like everyone do not get a second look (Eastwick, Finkel, Mochon, & Ariely, 2007). This paper introduces the novel hypothesis that people gauge their “special-ness” or substitutability by comparing their own qualities to the qualities of the partner’s salient alternatives (Thibaut & Kelley, 1959). In this metric, the perception that one has desirable qualities that alternatives do not possess makes one hard to replace and bolsters trust in the partner’s continued responsiveness. In contrast, the perception that one’s own qualities are common among these alternatives threatens feelings of trust (because it makes the partner’s interest in alternatives harder to preempt).2

Comparing oneself to the partner’s alternatives is likely to be basic to trust because people understand how fairness norms limit their romantic options (Berscheid & Walster, 1969; Feingold, 1988; Rubin, 1973; Murray, Aloni, Holmes, Derrick, Leder, & Stinson, 2009; Walster, Walster & Berscheid, 1978). For instance, people who perceive themselves less positively on traits such as warm, intelligent, and attractive aspire to less desirable partners than people who perceive themselves more positively on such traits (Campbell, Simpson, Kashy & Fletcher, 2001; Murray, Holmes & Griffin, 1996a; Murray, Holmes & Griffin, 1996b). Similar pragmatism governs people’s choices on dating websites advertising “hot” prospects. Despite a plethora of options, people maximize the odds of success by pursuing equal matches (Lee, Loewenstein, Ariely, Hong & Young, 2008). Such pragmatism is prudent. The real world pressure to match on social commodities is so powerful that imbalances in dating partners’ physical attractiveness forecasts dissolution (White, 1980).

Seeking an equitable exchange motivates behavior in part because violating fairness norms can open the partner’s romantic options in undesirable ways. Partners’ commitments are constrained by their alternatives to the current relationship (Thibaut & Kelley, 1959; Rusbult & Van Lange, 2003). Their affections can waver when the life that might be had with a possible alternative partner looks better than the life with the current partner (Rusbult, 1983). People worry most about such fleeting affections when the partner’s value exceeds their own (Murray, Rose, Holmes, Derrick, Podchaski, Bellavia & Griffin, 2005). In such situations, partners are more likely to be poached by alternatives because one’s rivals interpret such mismatches as an open invitation. Indeed, a more attractive partner is more often the target of the advances and flirtations of others than the less attractive partner (White, 1980). Because the entreaties of more deserving or better-matched alternatives can pose real temptation, gauging the partner’s love and commitment likely requires tracking how one stacks up against the partner’s best options.

Becoming Irreplaceable: Creating a Niche by Currying Partner Dependence

In the social comparative metric we hypothesize, believing that a partner sees positive qualities in the self is necessary, but not sufficient, to instill trust in the partner’s continued responsiveness (Murray et al., 2000). Instead, people also need to feel valued for the “right” reasons – reasons that make them hard to replace. In assessing how easily they could be replaced, people may look first to their inherent qualities – namely, their physical appeal and personality (Murray et al., 2000). When inspection of the partner’s available alternatives reveals that one’s own qualities are unique, and thus, hard to replicate, such sentiments strengthen trust. When such assessments yield reason to question one’s special value, such sentiments motivate people to distinguish themselves from alternatives. In particular, believing one’s qualities are common, and thus, easy to replicate, motivates people to create a bigger niche for themselves in their partner’s life (Murray et al., 2009). People can carve such niches by increasing their partner’s dependence – the structural basis for commitment (Rusbult & Van Lange, 2003). In particular, people can make themselves more indispensable by satisfying more of their partner’s practical needs (e.g., providing instrumental support) and by strengthening their partner’s investment in the relationship (e.g., limiting contact with outside friends).

The existing literature provides normative, albeit indirect, evidence of the tendency to niche-create in response to threat. Experimentally priming the exchange script – the notion that partners need to match in value to avoid being replaced – automatically elicits compensatory efforts to ensure one’s value to the partner (Murray et al., 2009). For instance, people in dating relationships report greater concerns about being inferior to their partner and being replaced when the metaphor of an economic exchange is primed implicitly (through pictures of U.S. coins). They also report stronger efforts to increase their partner’s dependence on them by taking responsibility for their partner’s life tasks (e.g., scheduling appointments) and limiting contact with other friends. Similarly, newlyweds respond to one day’s feelings of inferiority to the partner by currying the partner’s dependence on subsequent days, going out of their way to run errands, prepare lunches, and search for lost keys (Murray et al., 2009). Being rejected by others similarly prompts efforts to prove one’s value to others, through behaviors as diverse as soliciting friendships, conforming, and working harder on group tasks (Maner, DeWall, Baumeister & Schaller, 2007; Williams, Cheung, & Choi, 2001; Williams & Sommers, 1997).

The Role of Self-Esteem

Although people may aspire to feel irreplaceable, some people are likely to have an easier time than others convincing themselves of their value to their partner. In gauging a romantic partner’s regard, people assume that their partner sees them as they see themselves (Murray et al., 2000). Consequently, people with low self-esteem (i.e., lows) incorrectly believe that their partner perceives relatively few qualities worth valuing in them. In contrast, people with high self-esteem (i.e., highs) correctly believe that their partner perceives many qualities worth valuing in them (Murray et al., 2000). People with high self-esteem also perceive themselves as engaging in more positive relationship behaviors, such as providing support and forgiving transgressions, than people with low self-esteem (Feeney & Collins, 2001; Strelan, 2007). Such findings suggest that high self-esteem people should have an easier time concluding that it would be difficult, if not impossible, for their partner to find anyone quite like them – let alone find someone better. Therefore, in ongoing relationships, we hypothesize that the goal of feeling irreplaceable is more likely to be satiated for high than low self-esteem people.

How might differential goal satiation affect the sensitivity of the social comparative metric meant to gauge and protect one’s status as irreplaceable to the partner? Consider first evidence that enhances one’s unique value to the partner, such as receiving a partner’s compliment on one’s appearance. Such information moves people closer to the goal of feeling irreplaceable. If the desired goal is already met for most high self-esteem people, such an affirmation should have little effect on trust in the partner’s love and commitment (Leary & Baumeister, 2000). However, it should buoy the hopes of low self-esteem people. For lows, such an affirmation should help satiate their unfulfilled goal to feel irreplaceable, thereby heightening trust in the partner. Consistent with this hypothesis, chronically being less trusting does indeed sensitize low self-esteem people to reasons to be more trusting. For instance, pointing to a partner’s faults, and thereby humanizing the partner, increases trust in the partner’s love and commitment for low, but not high, self-esteem people (Murray et al., 2005). Thinking about the broader meaning of a compliment also increases trust in the partner’s love and commitment for low, but not high, self-esteem people (Marigold, Holmes & Ross, 2007).

Now consider evidence that threatens one’s unique value to the partner, such as overhearing a partner compliment a competitor’s appearance. Such information moves one away from the goal of feeling irreplaceable. If the goal of feeling irreplaceable is largely met for most high self-esteem people, any significant threat to this status should motivate compensatory processes aimed at restoring this sentiment. Specifically, high self-esteem people should react to the possibility that they might be replaced with heightened behavioral efforts to prove their instrumental value to their partner. Consistent with this hypothesis, chronically being more trusting motivates high self-esteem people to defend against any threats to this desired state. For instance, high self-esteem people respond to signs of their own faults, such as those revealed by experimentally-induced failure on an intelligence test or a recent failure at work, by concluding that their partner actually loves them more rather than less (Murray, Holmes, MacDonald & Ellsworth, 1998; Murray, Griffin, Rose & Bellavia, 2006). They also react to signs of their partner’s irritation with them by increasing their sense of connection to that same partner (Murray, Rose, Holmes, Bellavia & Kusche, 2002). However, information that threatens their value to their partner should only serve to compound low self-esteem people’s fears of being replaced. Easily hurt, they might then abandon any efforts to create a niche for themselves, and perhaps instead, distance themselves from their partner. In so doing, they effectively protect themselves against the pain of rejection in advance (Murray et al., 1998; Murray et al., 2002).

Summary of Hypotheses and Research Strategy

The current research examines how the need to feel irreplaceable affects perception and behavior in the dating relationships of low and high self-esteem people. We argue that people gauge their status as being more or less replaceable by comparing their qualities to the qualities of available others. To our knowledge, this social comparative origin of relational (in)security has never been examined in the literature. In Experiment 1, we satiated the goal of feeling irreplaceable by leading experimental participants to believe their partner perceived qualities in them that their partner could not imagine finding in others. We expected low, but not high, self-esteem people to report greater trust in the experimental than control condition. In Experiment 2, we thwarted the goal of feeling irreplaceable by leading experimental participants to believe that the qualities their partner valued most in them were readily available on the open market. We expected high, but not low, self-esteem people to compensate for this threat with behavior aimed at creating a unique niche for themselves in their partner’s life. In a final study of dating relationships, we asked both members of the couple to complete measures of self-esteem, feeling irreplaceable, trust, niche creation, and their partner’s actual value to them. We expected high self-esteem people to see themselves as harder for their partner to replace. We also expected feeling irreplaceable to more strongly predict trust in the partner for people low than those high in self-esteem (replicating Experiment 1). We further expected the realistic possibility of being replaced to provoke greater efforts at niche-creation for high than low self-esteem people. Ongoing relationships offer greater odds of being replaced by an alternative when one’s partner finds comparatively little to value in one’s traits (Murray et al., 1996b; Murray & Holmes, 1997). We therefore utilized the partner’s actual regard for one’s traits as an objective benchmark of threat in the correlational study. We expected actually being less valued by one’s partner, and thus, more readily replaced, to more strongly provoke niche-creation for people high than those low in self-esteem (replicating Experiment 2).

Experiment 1: Satiating the Goal of Feeling Irreplaceable

Does satiating the goal of feeling irreplaceable increase trust in the partner for people low in self-esteem in particular? In Experiment 1, we satiated this goal by leading experimental participants to believe their partner (who was physically present) perceived many desirable qualities in them that he/she could not imagine finding in anyone else. We then measured three core components of trust. Holmes and Rempel (1989) define trust in terms of abstract positive expectations that a partner will responsively attend to one’s needs, both now and in the future (see also Murray & Holmes, in press). We triangulated on trust by measuring perceptions in the partner’s love and commitment, perceptions of the partner’s responsiveness, and perceptions of the partner’s closeness (Murray et al., 2006). We expected people with low self-esteem to report greater trust in their partner when their partner gave them reason to feel irreplaceable. We did not expect to observe as pronounced increases for high self-esteem people because highs already possess numerous reasons to feel irreplaceable.

Method

Participants

Seventy-seven undergraduate couples involved in exclusive dating relationships at the University at Buffalo participated in exchange for course credit or a ticket for a $100 lottery. Participants averaged 19.7 (SD = 2.1) years in age; their relationships averaged 13.6 months in length (SD = 13.8).

Procedure

On arriving at the laboratory, couples were told that the study examined the thoughts and feelings that couples in dating relationships commonly experience. Each member of the couple then sat individually at one of two laboratory tables, arranged such that participants had their backs to their partner. The experimenter then told participants that they would be completing identical sets of questionnaires and that they would only proceed from one questionnaire to the next when both members of the couple had finished. The experimenter also reminded participants not to speak to one another. All participants then completed the Rosenberg (1965) self-esteem scale (α= .91) among other measures.

For couples in the experimental condition, target participants were led to believe that their partner was spending an inordinate amount of time listing the ways in which they perceived the target to be irreplaceable. To achieve this end, the target participant received a one page questionnaire that asked them to list “one or two qualities in their partner that they really value – precisely because they don’t think they could find those qualities in another partner.” The instructions then reiterated (in bold) that participants list one or two qualities. Although the targets were led to believe that their partner received the same questionnaire, the partner actually received a one page questionnaire that asked them to list as many of the items in their home as they could generate (and a minimum of 25 items). Through this subterfuge, the partner spent several more minutes writing than the target, giving experimental participants reason to believe that their partner thought they would be really hard to replace. (The experimenter stopped partners 5 minutes after the target participant finished if the partner was still writing). For couples in the control condition, both the target and the partner received the one page questionnaire that asked them to list one or two irreplaceable qualities and both finished the task at approximately the same time. All participants then completed dependent measures tapping perceptions of the partner’s acceptance and love, perceptions of the partner’s responsiveness, and perceptions of the partner’s closeness among fillers (tapping closeness). Participants then completed the manipulation check, were debriefed, and thanked.3

Measures

Perceived love and commitment

This 15-item scale (α= .90), adapted from Murray et al. (2002), tapped perceptions of the strength and stability of the partner’s love and commitment (e.g., “My partner loves and accepts me unconditionally”; “I am confident that my partner will always want to stay in our relationship”). Participants responded on a 7-point scale (1 = not at all true, 7 = completely true).

Perceived responsiveness

This 8-item scale (α= .82) tapped perceptions of the strength of the partner’s motivation to provide responsive care (e.g., “My partner would not help me if it meant he/she had to make sacrifices (reversed); “I am confident that my partner will always be responsive to my needs”). Participants responded on a 7-point scale (1 = not at all true, 7 = completely true).

Perceived closeness

This 5-item scale (α= .93), adapted from Murray et al. (2005) tapped perceptions of the partner’s closeness to the self (e.g., “My partner is closer to me than any other person in his/her life”; “My partner would choose to spend time with me over any one else in his/her life”). Participants responded to these items on a 9-point scale (1 = not at all true, 9 = completely true).

Manipulation check

This 1-item measure asked participants whether their partner listed more qualities than they expected (1 = a lot less, 9 = a lot more).

Results

Did low self-esteem people report greater trust when their partner provided a litany of ways in which they were irreplaceable? We created a composite measure of trust in the partner from the measures of perceived love and commitment, perceived responsiveness, and perceived closeness (each transformed to a z-score and averaged, α= .87). We then conducted regression analyses predicting the dependent measures from experimental condition (1 = experimental, 0 = control), the centered main effects of self-esteem, and the self-esteem by condition interaction. Table 1 presents the predicted scores by condition for participants relatively low and high in self-esteem (one standard deviation below and above the mean, respectively). Table 2 contains the results of the regression analyses (i.e., standardized betas, t-values, and squared semi-partial correlations as indicators of effect size). Tables 1 and 2 list both the subscale indices of trust (i.e., perceived love and commitment, responsiveness, and closeness) and the composite measure of trust. We focus our text discussion on the composite measure of trust as analyses of the subscales yielded parallel and largely significant results.4, 5

Table 1.

Predicted scores as a function of condition and self-esteem in Experiment 1.

| Dependent Measures | Low Self-Esteem | High Self-Esteem | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental | Control | Experimental | Control | |

| Trust composite | −.08 | −1.06 | .32 | .52 |

| Perceived love and commitment | 5.77 | 4.72 | 6.19 | 6.45 |

| Perceived responsiveness | 5.79 | 5.22 | 6.12 | 6.28 |

| Perceived closeness | 7.45 | 5.67 | 7.99 | 8.23 |

| Manipulation check | 5.90 | 5.05 | 6.03 | 5.22 |

Table 2.

Results of the regression analyses in Experiment 1.

| Self-Esteem | Condition | Self-Esteem by Condition | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Measure | β | t | sr2 | β | t | sr2 | β | t | sr2 |

| Trust composite a | .89 | 4.63** | .22 | .22 | 2.07* | .04 | −.53 | −2.87** | .08 |

| Perceived love and commitment a | .98 | 5.33** | .27 | .22 | 2.17* | .04 | −.60 | −3.36** | .11 |

| Perceived responsiveness b | .58 | 2.79** | .10 | .11 | < 1 | .01 | −.32 | −1.60 | .03 |

| Perceived closeness a | .80 | 4.08** | .18 | .24 | 2.21* | .05 | −.511 | −2.67** | .08 |

| Manipulation check c | .05 | < 1 | .00 | .30 | 2.32* | .07 | −.01 | < 1 | .00 |

+ p < .10,

p < .05,

p < .01.

The degrees of freedom for the error term: 73.

The degrees of freedom for the error term: 72.

The degrees of freedom for the error term: 67.

Trust in the Partner

The regression analysis predicting the composite measure revealed a significant main effect of self-esteem, a significant main effect of condition, and a significant self-esteem by condition interaction. We then decomposed the interaction into the simple effects of condition for participants one standard deviation above and below the mean in self-esteem (Aiken & West, 1991). As expected, low self-esteem participants reported significantly greater trust when their partner seemed to list many hard to replace qualities in them, β= .55, t(73) = 3.34, sr2 = .11, p < .01. The simple effect of condition was not significant for highs, β= −.11, t(73) < 1, sr2 = .01.

Manipulation Check

The regression analysis predicting the manipulation check revealed only the expected main effect of condition. Relative to control participants (M = 5.13), experimental participants were more likely to describe their partner as listing more qualities than they expected (M = 5.96).

Discussion

Giving people reason to believe that their partner found them irreplaceable increased trust in the partner for people low in self-esteem. When their partner’s prolonged cataloguing of their special qualities gave lows greater reason to feel hard to replace, they reported greater trust in their partner’s continued motivation to be responsiveness. In contrast, believing their partner listed many irreplaceable qualities in them had no significant effect on trust for people high in self-esteem. We predicted this effect because highs, unlike lows, are likely at a psychological ceiling in trust because their abundant self-concept resources should provide a ready basis for concluding they are irreplaceable (Murray et al., 2000). We demonstrate that highs do indeed feel more irreplaceable than lows in the final correlational study. Of course, the manipulation conveyed more than just information about one’s status as irreplaceable to the partner. It also conveyed the positive nature of the partner’s regard. Because our social comparative logic posits a distinct benefit of bettering one’s competitors, we better distinguish the effects of feeling irreplaceable from feeling positively regarded by the partner in the subsequent studies.

Experiment 2: Thwarting the Goal of Feeling Irreplaceable

Does thwarting the goal of feeling irreplaceable increase efforts to carve out a unique niche in the partner’s life for people high in self-esteem? In Experiment 2, we thwarted this goal by leading experimental participants to believe that the qualities that their partner valued most in them were readily available on the open marketplace. We then measured the tendency to carve a niche for oneself in the partner’s life by making one’s partner more dependent on the relationship (i.e., fulfilling more needs, amplifying investments). We expected feeling more replaceable to generally threaten feelings of trust. We also expected people with high self-esteem to report stronger niche-creation efforts when they were led to believe that the traits their partner cherished in them were readily available in alternative partners. We did not expect to observe similar niche-creation for low self-esteem people because they typically respond to rejection anxieties by distancing themselves from their partner (Murray et al., 1998; 2002).

Method

Participants

Sixty-nine University of Waterloo undergraduates involved in dating relationships averaging 26.2 months in length (SD = 18.1) participated in exchange for course credit, restaurant gift certificates and/or chocolate bars.

Procedure

On arriving at the laboratory, participants were told the study examined people’s thoughts and feelings in dating relationships. All participants then completed background measures that contained the Rosenberg (1965) self-esteem scale. Then they completed a “Valuing Inventory”. Participants received a list of 30 positive attributes (e.g., assertive, patient, physically attractive, responsible, leader, creative, forgiving) and they were instructed to identify the 5 qualities that their partner liked or valued most in them. Experimental participants were then told (via computer) that the valuing inventory taps personality profiles in relationships, much like on-line dating services. Experimental participants then received (purportedly individualized) feedback stating that the profiles of qualities their partner valued in them made them very similar to others because those qualities are very common in most romantic partners (i.e., shared by 75% of people). Control participants did not receive any feedback. All participants then completed dependent measures including the perceived love and commitment scale from Experiment 1 (α= .92) and two scales tapping niche-creation among fillers.6 These scales tapped behavioral efforts to take responsibility for a partner’s life tasks and behavioral efforts to make oneself integral in the partner’s life and social network. Experimental participants then completed a manipulation check (i.e., “The qualities that my partner values in me are pretty common among romantic partners”, 1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strong agree).7 All participants were debriefed.

Measures

Taking behavioral responsibility

This 30-item scale (α= .89), expanded from Murray et al. (2009), assessed how often people satisfied their partner’s practical or instrumental needs (e.g., “cooking for my partner”; “organizing activities with other friends”; “helping my partner with school assignments/exams”; “keeping my partner up to date on things that are going on with friends”; “remembering my partner’s important appointments”; “doing favors for my partner”; “solving my partner’s problems”). Participants rated how often they engaged in each activity on an 8-point scale (0 = never, 4 = every couple of weeks, 8 = every day).8

Narrowing attention

This 16-item scale (α= .82) provided a concrete behavioral index of narrowing attention. It tapped concrete behavioral efforts to focus the partner’s attention and activities around oneself, thereby increasing the partner’s investment in the relationship (e.g., “I try to find activities that just my partner and I can do together”; “I do the things my partner likes to do so he/she won’t need to do those things with other people”; “I point out things I’ve done for my partner to make sure he/she notices them”; “I get jealous when my partner spends time on activities that don’t involve me”; “It means a lot to me when my partner compliments me”; “It makes me feel really good to hear my partner talk about us”; “It makes me feel good when my partner says I do something better than he/she does”). Participants responded on 9-point scales (1 = not at all characteristic of me, 9 = completely characteristic of me).

Results

Did thwarting the goal of feeling irreplaceable motivate relationship compensation for high self-esteem people? To examine this question, we created a composite measure of niche-creation (α= .56) by standardizing and averaging responses to taking behavioral responsibility and narrowing attention scales. We then conducted regression analyses predicting the dependent measures from experimental condition (1 = experimental, 0 = control), the centered main effects of self-esteem, and the self-esteem by condition interaction. Table 3 presents the predicted scores. Table 4 contains the results of the regression analyses. Tables 3 and 4 list both the subscale indices of niche-creation and the composite measure. We focus our discussion on the composite measure of niche-creation as the subscales yielded parallel and significant results.

Table 3.

Predicted scores as a function of condition and self-esteem in Experiment 2.

| Dependent Measures | Low Self-Esteem | High Self-Esteem | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental | Control | Experimental | Control | |

| Perceived love and commitment | 5.57 | 5.83 | 5.58 | 6.05 |

| Niche-creation composite | −.15 | .53 | .06 | −.58 |

| Taking behavioral responsibility | 3.80 | 4.53 | 4.35 | 3.65 |

| Narrowing attention | 3.98 | 4.66 | 3.88 | 3.26 |

Table 4.

Results of the regression analyses in Experiment 2.

| Self-Esteem | Condition | Self-Esteem by Condition | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Measure | β | t | sr2 | β | T | sr2 | β | t | sr2 |

| Perceived love and commitment a | .12 | < 1 | .01 | −.21 | −1.72 | .04 | −.06 | < 1 | .00 |

| Niche-creation composite a | −.67 | −4.20** | .21 | −.01 | < 1 | .00 | .57 | 3.58** | .15 |

| Taking behavioral responsibility a | −.42 | −2.46* | .08 | −.01 | < 1 | .00 | .48 | 2.88** | .11 |

| Narrowing attention a | −.69 | −4.41** | .24 | −.02 | < 1 | .00 | .46 | 2.94** | .10 |

+ p < .10,

p < .05,

p < .01.

The degrees of freedom for the error term: 65.

Perceived Love and Commitment

The regression analysis predicting trust in the partner’s love and commitment revealed a marginal main effect of condition. Participants tended to report less trust in the partner when they believed their qualities were common on the open-market place (M = 5.54) as compared to controls (M = 5.94), consistent with our assertion that feeling irreplaceable is critical for trust.

Niche-Creation

The regression analysis predicting the niche-creation composite revealed the expected significant self-esteem by condition interaction. High self-esteem people reported significantly more niche-creation when they believed their qualities were common β= .39, t(65) = 2.46, sr2 = .07, p < .05. Low self-esteem participants evidenced significantly less niche-creation when they believed their qualities were common, β= −.29, t(65) = −2.63, sr2 = .07, p < .05.

Discussion

Thwarting the goal of feeling irreplaceable tended to decrease trust in the partner’s acceptance and love regardless of self-esteem. However, only high self-esteem people compensated for this threat. When high self-esteem people believed that the qualities their partner most valued in them were readily available on the open-market place, they reported behaving in ways that created a unique niche for themselves in their partner’s life. Although we reasoned that low self-esteem people might not defensively niche-create, they actually downplayed their compensatory efforts more in the common than the control condition. This latter effect mirrors a typical response low self-esteem people have to rejection anxieties; they distance from their partner (Murray et al., 1998; 2002). On having the suspicion that their qualities were easily substituted confirmed, low self-esteem people might simply have believed that there was little point trying to become more important to their partner by doing extra things or acting in ways to become more special. Importantly, this experiment distinguished the effects of feeling more or less irreplaceable from the effects of being more or less positively regarded. Experimental and control participants both identified five qualities their partner valued in them. The experimental condition differed from the control conditions only in conveying feedback raising the possibility that the partner could easily and readily find such positive qualities in alternate partners (if the partner was to look).

A Correlational Replication

To determine the generality of the experimental dynamics, we had both members of dating couples complete measures of self-esteem, feeling irreplaceable, trust, niche creation, and their actual regard for one another (to provide an objective indicator of each partner’s status as more or less replaceable). We expected people with high self-esteem to feel more irreplaceable to their partner than people low in self-esteem. We also expected feeling irreplaceable to predict greater gains in trust for people low than those high in self-esteem. We further expected the threat of actually being less valued by one’s partner (i.e., more replaceable) to predict stronger efforts at niche-creation for people high than those low in self-esteem.

Method

Participants

One hundred thirty-four University at Buffalo undergraduate couples in exclusive dating relationships at least four months in length completed a questionnaire in exchange for credit or $10 payment. Participants averaged 19.6 (SE = 1.5) years in age.9

Method

Participants were told that the study examined people’s thoughts and feelings in relationships. All participants then completed an informed consent form and completed the measures on computer. These measures included global self-esteem, feeling irreplaceable, trust (i.e., perceptions of the partner’s love and perceptions of the partner’s commitment), niche-creation (i.e., taking behavioral responsibility and narrowing attention), perceptions of the partner, and perceptions of the partner’s regard for the self (among other measures).

Measures

Global self-esteem

Rosenberg’s (1965) 10-item measure (α= .89) assessed global self-evaluations (e.g., “I feel that I am a person of worth, at least on an equal basis with others”). Participants responded on a 7-point scale (1 = strongly disagree; 7 = strongly agree).

Feeling irreplaceable

This 14-item scale (α= .84) tapped perceptions that one’s qualities and behavior are not readily available in others (e.g., “My partner couldn’t find anybody else like me”; “My partner could find another partner who is just like me (reversed)”; “My partner knows that I do things for him/her that would be hard to replace”; “The kinds of qualities that I have are ones that my partner could easily find in another partner (reversed)”). Participants responded to these items on 9-point scales (1 = not at all true, 9 = completely true).

Perceived love

This 8-item scale (α= .74), adapted from Murray et al. (2000), tapped perceptions of the partner’s love (e.g., “My partner is very much in love with me”; “My partner loves me just as much as I love him/her”). Participants responded on 9-point scales (1 = not at all true, 9 = completely true).

Perceived commitment

This 7-item scale (α= .91), adapted from Rusbult, Martz and Agnew (1998), tapped the partner’s perceived commitment (e.g., “My partner is committed to maintaining his/her relationship with me”; “My partner wants our relationship to last forever”). Participants responded on 9-point scales (1 = not at all true, 9 = completely true).

Taking behavioral responsibility

The 30-item scale (α= .92) used in Experiment 2 assessed how often people satisfied their partner’s practical or instrumental needs (e.g., “cooking for my partner”; “organizing activities with other friends”; “remembering my partner’s important appointments”). Participants rated how often they engaged in each activity on an 8-point scale (0 = never, 4 = every couple of weeks, 8 = every day).

Narrowing attention

This 10-item measure provided a global index of narrowing attention. It tapped the general motivation (α= .83) to want the partner to be heavily invested in the relationship and focus his/her attention and activities around oneself (e.g., “I want my partner to feel there are some things that she/he needs me to do for him/her”; “I want my partner to feel like he/she couldn’t manage without me.”; “I point out the things I’ve done for my partner to be sure he/she notices them”; “It makes me feel good when my partner needs me to do things for him/her”). Participants responded on 9-point scales (1 = not at all true, 9 = completely true).

Perceptions of the partner

This 29-item scale (α= .89), expanded from Murray et al. (2000) tapped how participants perceived their partner on various positive and negative interpersonal attributes (e.g., “kind”, “selfish”, “warm”, “physically attractive”, “distant”, “socially skilled”). Participants responded on 9-point scales (1 = not at all characteristic of how my partner sees me, 9 = completely characteristic). Negative traits were reverse-scored.

Perceived regard on traits

This 29-item scale (α= .88), expanded from Murray et al. (2000) tapped how participants believed their partner saw them on various positive and negative interpersonal attributes (e.g., “kind”, “selfish”, “warm”, “physically attractive”, “distant”, “socially skilled”). Participants responded on 9-point scales (1 = not at all characteristic of how my partner sees me, 9 = completely characteristic). Negative traits were reverse-scored.

Results

Do people with high self-esteem indeed feel harder to replace than people with low self-esteem? Does feeling irreplaceable to the partner more strongly predict trust for people low than high in self-esteem? And does being less than special to one’s partner predict stronger efforts at niche-creation for people high than those low in self-esteem? We used structural equation modeling (SEM) to test these hypotheses because responses from members of the same couple are dependent. SEM both accommodates the dyadic structure of data from two partners (Kenny & Cook, 1999) and provides efficient tests of gender differences (Kenny, 1996).10

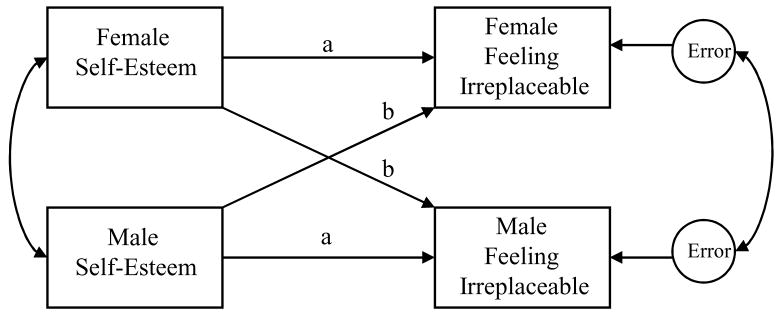

Predicting Feelings of Being Irreplaceable

We first obtained estimates for a preliminary model examining the association between global self-esteem and feeling irreplaceable. Figure 1 presents our analytic model. In this model, non-primed paths reference women’s criterion variables; primed paths reference men’s criterion variables. This model predicts feeling irreplaceable from both the actor’s (path a and a′) and the partner’s (path b and b′) self-esteem. As the first step, we individually constrained the effects of actor’s self-esteem and partner’s self-esteem across gender. Doing so revealed no significant gender differences (a 1-df Chi-square test). We then obtained the estimates for a model that pooled corresponding paths for men and women. As expected, people with high self-esteem feel more irreplaceable than people with low self-esteem, β= .19, z = 3.21, p < .01. No significant effect emerged for the partner’s self-esteem, β= .05, z = 0.84.

Figure 1.

Predicting feeling irreplaceable from self-esteem.

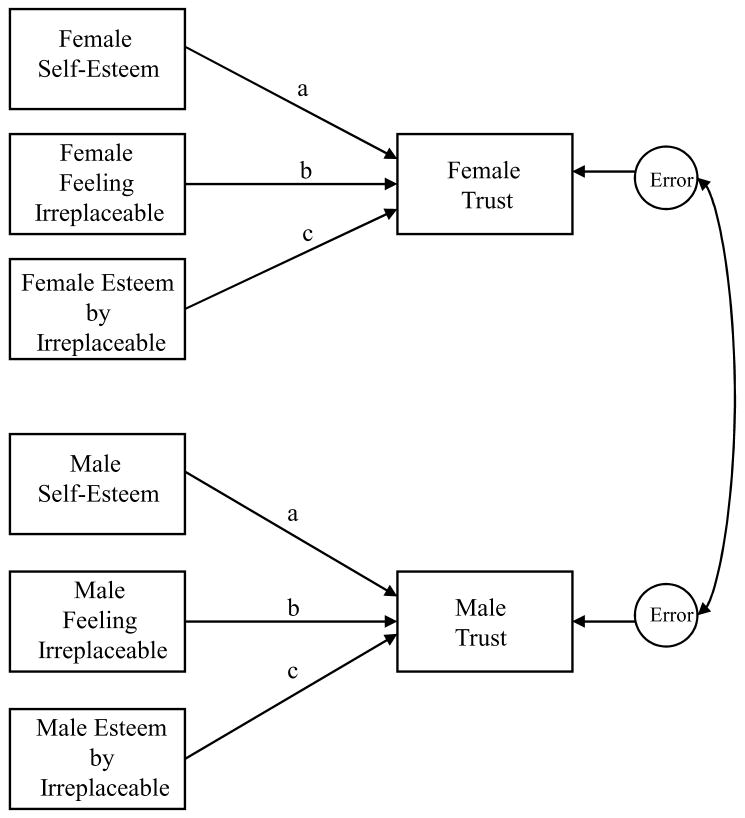

Predicting Trust in the Partner

We created a composite measure of trust in the partner (α= .50) by standardizing and summing responses to the perceived love and commitment measures. We then examined whether self-esteem moderated the nature of the association between feeling irreplaceable and trust using structural equation modeling. Figure 2 presents our analytic model. For each actor, we predicted trust from his or her centered self-esteem score (paths a and a′), his or her centered feeling irreplaceable score (paths b and b′), and a cross-product term representing the interaction between self-esteem and feeling irreplaceable (paths c and c′). (We also included estimates for the intercepts, all correlations among the exogenous variables, and the correlations between men’s feeling irreplaceable and the residual variance in women’s trust and between women’s feeling irreplaceable and the residual variance in men’s trust in the estimation of the model.) As individually constraining the effects of self-esteem, feeling irreplaceable, and the interaction terms across gender yielded no significant differences, we present pooled coefficients in Table 5.

Figure 2.

Predicting trust from self-esteem, feeling irreplaceable and the self-esteem by irreplaceable interaction.

Table 5.

Pooled SEM coefficients predicting trust from self-esteem, feeling irreplaceable, and their interaction.

| Self-Esteem | Feeling Irreplaceable | Self-Esteem by Feeling Irreplaceable | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Measure | β | z | β | z | β | z |

| Trust composite | .10 | 2.00* | .54 | 10.30** | −.13 | −2.69* |

| Perceived love | .16 | 3.16** | .54 | 10.34** | −.12 | −2.40* |

| Perceived commitment | .03 | < 1 | .48 | 8.25** | −.13 | −2.44* |

+ p < .10,

p < .05,

p < .01.

CFI = 1.00, χ2(7, N = 134) = 3.8, ns.

CFI = .99, χ2(7, N = 134) = 8.1, ns.

CFI = 1.00, χ2(7, N = 134) = 6.2, ns.

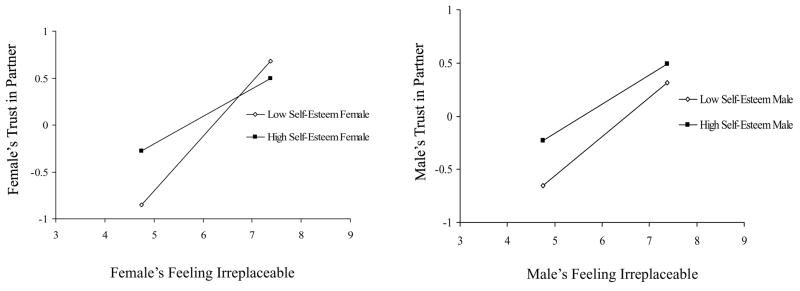

Table 5 lists the results for the subscale indices of perceived love and perceived commitment and the composite measure of trust. We focus our discussion on the composite measure of trust as the individual subscales yielded parallel and significant results. The estimates for this model yielded a significant pooled main effect for feeling irreplaceable predicting the trust composite and a significant pooled self-esteem by feeling irreplaceable interaction. We then decomposed this interaction into the simple effects of feeling irreplaceable on trust for people relatively low and high in self-esteem (one standard deviation below and above the mean, respectively). Figure 3 illustrates the effects separately for men and women. Feeling more irreplaceable predicted significantly greater trust for people low and high in self-esteem. However, feeling irreplaceable predicted stronger gains in trust for people low, β= .68, z = 8.95, p < .001, than people high in self-esteem, β= .40, z = 5.29, p < .001.

Figure 3.

Predicting trust from feeling irreplaceable for low and high self-esteem people.

One important alternative explanation for this effect exists. The benefits of feeling irreplaceable might reflect the benefits of believing that a partner regards one’s traits positively (Murray et al., 2000). We examined a further model to determine whether feeling hard to replace conveys added assurance (as our assumption of a social comparative metric implies). In this model, we included perceptions of the partner’s regard for one’s traits as a control variable. That is, we added the measure tapping how people believed their partner saw them on 29 different interpersonal qualities as a further predictor of trust. Estimates for these models reveal that feeling irreplaceable uniquely and strongly predicted greater trust in the partner, β= .50, z = 9.09, p < .001, and this effect was still moderated by self-esteem, β= −.11, z = −2.24, p < .05.

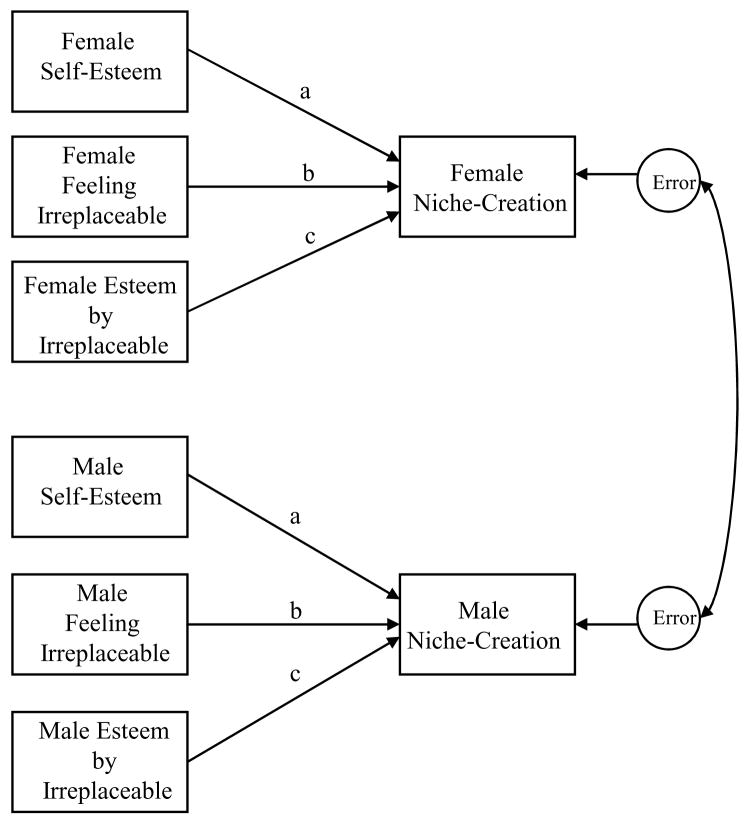

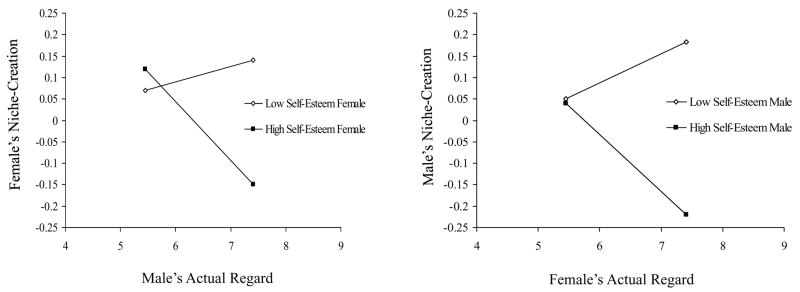

Predicting Niche-Creation

We created a composite measure of niche-creation (α= .56) by standardizing and summing responses to the taking behavioral responsibility and narrowing attention subscales. We then examined whether self-esteem moderated the nature of the association between actually being valued by one’s partner and niche-creation using structural equation modeling. Figure 4 presents our analytic model. For each actor, we predicted niche-creation from his or her own self-esteem score (centered, paths a and a′), the partner’s actual regard for the actor’s traits on the interpersonal qualities scale (centered, paths b and b′), and a cross-product term representing the interaction between self-esteem and actually being valued (paths c and c′). We utilized the partner’s actual regard for the actor’s traits to measure the actor’s value as “irreplaceable” to the partner because such evaluations effectively track partner commitment (Murray et al., 1996b; Van Lange & Rusbult, 1998). (We also included estimates for the intercepts and all correlations among the exogenous variables in the estimation of the model.) As we found no significant gender effects, the results reported in Table 6 represent pooled coefficients.

Figure 4.

Predicting niche-creation from self-esteem, the partner’s actual regard and the self-esteem by regard interaction.

Table 6.

Pooled SEM coefficients predicting niche-creation from self-esteem, the partner’s regard for one’s traits, and their interaction.

| Self-Esteem | Partner’s Regard | Self-Esteem by Partner’s Regard | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Measure | β | z | β | z | β | Z |

| Niche-creation composite a | −.13 | −2.10* | −.04 | < 1 | −.15 | −2.53* |

| Taking behavioral responsibility b | .00 | < 1 | −.04 | < 1 | −.15 | −2.40* |

| Narrowing attention c | −.20 | −3.24** | −.02 | < 1 | −.11 | −1.69+ |

p < .10,

p < .05,

p < .01.

CFI = 1.00, χ2(9, N = 134) = 5.4, ns.

CFI = 1.00, χ2(9, N = 134) = 8.8, ns.

CFI = 1.00, χ2(9, N = 134) = 8.63, ns.

Table 6 lists both the individual and composite indices of niche-creation. We focus our discussion on the composite measure as the subscales yielded parallel results. The estimates for this model yielded a significant pooled main effect for self-esteem and a significant pooled self-esteem by partner’s actual regard interaction. We then decomposed this interaction into the simple effects of being of greater or lesser value to the partner for actors relatively low and high in self-esteem (one standard deviation below and above the mean, respectively). Figure 5 illustrates the effects separately for men and women. As expected, people high in self-esteem compensated for being less valued by their partner with greater efforts to niche-create, β= −.17, z = −1.85, p = .06. However, people low in self-esteem engaged in less niche-creation when they were valued less by their partner, although this effect was not significant, β= .09, z = 1.25.11

Figure 5.

Predicting niche-creation from the partner’s actual regard for low and high people.

Discussion

The results of the correlational study replicate the dynamics observed in the experiments using convergent operational definitions of gains and threats to one’s status as irreplaceable. Both low and high self-esteem people report greater trust in their partner when they believe it would be harder for their partner to replace them. However, high self-esteem people possessed more of this chronic trust-resource than low self-esteem people: They reported feeling more irreplaceable than low self-esteem people. Global self-esteem in turn predicted how people responded to experiences that affirmed or threatened this prerequisite for trust. Incremental gains in one’s status as irreplaceable predicted stronger gains in trust for people low than those high in self-esteem. However, being valued less by the partner, and thus, objectively easier to replace, predicted greater niche-creating behavior for high, but not low, self-esteem people.

General Discussion

Because the romantic marketplace is inherently competitive (Thibaut & Kelley, 1959), being valued for one’s attractiveness, wit, or athleticism may not offer complete security. Another more attractive, wittier, or more agile alternative might always come along. To protect against such threats, Pinker (2008) advises searching for a partner whose love is nontransferable because it is inspired by one’s own idiosyncratic value. To trust in a partner’s continued responsiveness, people need to feel irreplaceable. They need to believe that their partner perceives something in them that their partner could not imagine finding it elsewhere.

Feeling Irreplaceable: A Needed Sense of Assurance

The current findings suggest that feeling irreplaceable functions as a goal state in relationships. People gauge the status of this goal in part by relying on a comparative metric – one that compares their qualities to the qualities of their partner’s available alternatives. When this comparison reveals that one’s attributes are rare, it supports trust in the partner. When this comparison reveals that one’s attributes are common, it motivates compensatory behavioral efforts to carve a niche for oneself. However, global self-esteem (and the associated feelings of being more or less replaceable) seems to calibrate the sensitivity of the comparative metric (see Leary & Baumeister, 2000, for similar arguments about the sociometer).

The cross-sectional study of dating couples suggests that feeling irreplaceable generally predicts greater trust in the partner. It further revealed that believing a partner values one’s traits is not sufficient to instill trust (as prior research assumed, Murray et al., 2000). Instead, feeling irreplaceable confers added and unique benefit beyond believing that the partner regards one’s traits positively. However, people with high self-esteem are chronically more likely to feel irreplaceable than people with low self-esteem. Such differential chronic goal satiation also predicts responses to information that either satiates or threatens this goal. In Experiment 1, incremental gains to one’s status as irreplaceable predicted significant increases in trust for people low, but not high, in self-esteem. The correlational study revealed parallel dynamics using chronic feelings of being irreplaceable as the barometer of one’s special value to the partner. In Experiment 2, threats to one’s status as irreplaceable motivated compensatory efforts to create a niche for people high, but not low, in self-esteem. When led to believe that many alternatives possessed the qualities their partner valued most in them, highs reported engaging in more behaviors that guaranteed their special niche. In contrast, low self-esteem people downgraded such compensatory efforts. The correlational study revealed parallel dynamics using the partner’s actual regard as a barometer for the objective threat of being replaced.

These findings further illustrate the relationship-protective style that people with high self-esteem evidence in relationships (Murray et al., 1998; 2002; Murray, Holmes, Aloni, Pinkus, Derrick & Leder, in press). For instance, high self-esteem people are quick to dismiss reasons to doubt their partner’s acceptance (Murray et al., 1998; 2002) and they readily compensate for costs in their relationships by valuing their partner more (Murray et al., in press). These findings also further illustrate the ambivalence that characterizes low self-esteem people in relationships. Low self-esteem people were quick to grasp onto information that buoyed their hopes (e.g., Murray et al., 2005; Marigold et al., 2007). Witnessing their partner itemizing their “irreplaceable” ways in Experiment 1 made low, but not high, self-esteem people more trusting. However, upon having their fear that they could be easily replaced confirmed in Experiment 2, low self-esteem people actually distanced from their partner (Murray et al., 1998; 2002). They reported engaging in fewer behaviors that might make themselves indispensable.

This finding presents an intriguing counter-point to how low self-esteem people respond to the exchange script itself. In two relevant experiments, Murray et al. (2009) primed the exchange script (i.e., partner attributes are evenly traded). They did so by having participants play match-maker within a dating service simulation and divine marital fates based on partners’ match on social commodities. In these experiments, low self-esteem people reacted to exchange script priming by engaging in more niche-creating behaviors, not less (Murray et al., 2009). However, the exchange script priming in these experiments induced a comparison to the partner, not to the partner’s alternatives. This comparison simply raised the fear that one might be inferior and replaceable – one that motivated lows to do more to even the trade. Indeed, low self-esteem people might engage in stronger chronic niche-creating efforts (see Figure 5) because chronic fears of being inferior routinely motivate them to behaviorally compensate. Experiment 2 induced a comparison to the partner’s alternatives and it further escalated the threat by intimating that one’s qualities were common and inherently replaceable. The manipulation we used in Experiment 2 thus gave low self-esteem people reason to suspect that they had already failed in their efforts to niche-create. This prospect presumably left low self-esteem people much confident that they could indeed measure up – and they instead abandoned such efforts.

Of course, the current studies are not without their limitations. First, the correlational study cannot testify to the causal assumptions that underlie our moderation models. Moreover, we cannot discern whether gains or losses to one’s status (or both) drove the effects we observed in the correlational study. However, the experiments did not suffer from these limitations and they yielded parallel results. Second, the index of objective threat to one’s value to the partner in the correlational study provided only a proxy for how one stacks up to the partner’s alternatives in the partner’s mind. Nonetheless, actually manipulating one’s distinctness from the partner’s alternatives in Experiment 2 yielded parallel effects. Third, the internal consistencies of the composite measure of niche-creation were only moderate in size. We also obtained different measures of “narrowing attention” in Experiment 2 and the correlational study. Of course, inconsistencies in measurement lessen the likelihood of obtaining consistent and significant effects across studies (as lower reliability diminishes power). Nonetheless, we still found consistent and largely significant effects on each individual subscale measure across studies. Indeed, finding conceptually convergent results utilizing divergent methods could be seen as a distinct strength of our approach rather than a weakness.

Hypothesizing the existence of a comparative metric that gauges one’s uniqueness relative to the partner’s competitors also sheds light on the origin of relationship insecurities. To risk connection to a partner, people need to trust in that partner’s love and commitment (Murray et al., 2006). This level of trust seems to require two related inferences: One needs to be just as good a person as the partner (a dyadic comparative metric, Murray et al., 2005), and one’s own qualities need to stack up well against the partner’s alternatives (an alternatives comparative metric). Low self-esteem people have trouble making either inference. When they compare themselves to their partner, they come up short (Murray et al., 2005); when they compare themselves to others, they come up common and replaceable. In contrast, high self-esteem people readily make both inferences, but their status as special is not unassailable. In fact, the findings suggests that feeling common relative to others makes high self-esteem people worry enough about their partner’s regard to work harder on their relationships.

In pointing to a new way to conceptualize the origins of relational insecurities, the present results also point to directions for future research. We believe that self-esteem had its moderating effects because the goal of feeling irreplaceable is more likely to be fulfilled for high than low self-esteem people. If that is the case, further research might examine whether thoughts about a partner’s alternatives are more cognitively accessible for low than high self-esteem people. Future research might also further examine when low self-esteem people might escalate compensatory attempts to protect against their partner’s alternatives. Perhaps low self-esteem people distance in reaction to thoughts about their partner’s alternatives because they cannot readily imagine bettering these alternatives. If that is the case, over-coming such pessimism with unconscious primes, manipulations of cognitive load, or self-affirmations might be sufficient to induce relationship defense. Consistent with this logic, low self-esteem people actually compensate for rejection fears by seeking connection to their partner when they are cognitively busy, and thus, unable to correct their better judgment (Murray, Derrick, Leder & Holmes, 2008). Further research might also examine whether feeling irreplaceable is a more important basis for self-esteem for high than low self-esteem people. Much more so than lows, high self-esteem people pride themselves on being a better-than-average person (Taylor & Brown, 1988). Having this sense of one’s own uniqueness challenged might have engendered greater relationship defense for highs than lows because their self-esteem is more contingent on standing out from the crowd.

The Bankers’ Paradox Revisited

Although the parable of the Bankers’ Paradox has fascinated thinkers in a variety of disciplines, the implications of its dynamics for perception and behavior in close relationships have not been directly studied. The logic of the parable is that on those occasions when people need their partner the most, they are typically least able to reciprocate their partner’s kindnesses. Consequently, people need some means of assuring that their partner is motivated to take care of them when they are a bad credit risk. Feeling irreplaceable to the partner might provide just this needed liability insurance. Our studies indicated that when gained, it promotes trust in the partner’s love and commitment. When lost, it prompts compensatory behavioral efforts aimed at proving one is worth the risk and sacrifice. Feeling irreplaceable in a partner’s eyes indeed seems to be a unique source of security as Tooby and Cosmides (1996) surmised.

Acknowledgments

The research reported was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (MH 60105-02) to S. Murray and a Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council grant to J. Holmes.

We would like to thank Dale W. Griffin for statistical consultation and numerous undergraduate research assistants for their assistance in conducting this research.

Footnotes

The order of the second and third authors was determined alphabetically.

We use the term “irreplaceable” as a short-hand for “hard to replace”. We are not arguing that people would wish their partner a life alone if something were to happen to them. Nonetheless, a simple thought experiment is likely enough to reveal it would be unsettling to believe that one’s partner could replace oneself quickly and easily in the event of one’s unavailability.

Existing research relates one’s own satisfaction and commitment to the nature of the comparison one makes between one’s own partner and one’s own alternatives (e.g., Rusbult, Martz & Agnew, 1998). This paper complements and extends such research by presenting a novel perspective on how people might gauge their partner’s interest in exploring his/her alternatives to the current relationship.

The full set of items comprising the scales utilized in each study are available from the first author upon request.

The sample size varied across dependent measures because of missing data.

We did not find any consistent and significant main or moderating effects of gender in either experiment and so we collapse across gender in reporting the results.

The filler items were included to help disguise the focus of the research. These filler items included items tapping one’s own feelings of closeness to the partner, and thus, helped mask our interest in perceptions of the partner’s sentiment. We also included a measure of perceived barriers to the partner dissolving the relationship. We do not report the results for this measure in full because it revealed no significant effects and we did not collect this measure in the correlational study. Perceived barriers is also less central to the construct of niche-creation because people have limited control over barriers to the partner leaving the relationship (e.g., Sally cannot readily change the objective attractiveness of the alternative partners Harry might attract). We thus limit our discussion to the measures obtained consistently across studies.

Due to a computer error, this data was not collected for control participants. Experimental participants expressed strong agreement with this statement (M = 5.46, SD = 1.25).

As the items make clear, the measure of taking behavioral responsibility is retrospective in nature. We utilized retrospective items because we reasoned that the goal to feel irreplaceable would color perceptions of the past (Kunda, 1990). In the future, it would be value to utilize a prospective measure to see whether the motivation to niche-create also colors predictions for one’s future behavior.

Due to a recording error, the length of participants’ relationships was not obtained.

We did not expect to find any significant gender differences, but we had to model gender within the analyses to control for non-independence of partners’ responses.

We did not use feeling irreplaceable to the partner as a barometer of threat in this analysis because niche-creating behavior is both a barometer of threat and an indicator of responses to threat. Engaging in niche-creating behaviors should and does increase one’s feelings of being irreplaceable).

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Sandra L. Murray, University at Buffalo, State University of New York

Sadie Leder, University at Buffalo, State University of New York.

Jennifer C. D. McClellan, University of Waterloo

John G. Holmes, University of Waterloo

Rebecca T. Pinkus, University at Buffalo, State University of New York

Brianna Harris, University at Buffalo, State University of New York.

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. NY: Sage Publications; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Berscheid E, Walster EH. Interpersonal attraction. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment and loss (Vol. 1: Attachment) London: Hogarth Press; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell L, Simpson JA, Kashy DA, Fletcher GJO. Ideal standards, the self, and flexibility of ideals in close relationships. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2001;27:447–462. [Google Scholar]

- Eastwick PW, Finkel EJ, Mochon D, Ariely D. Selective versus unselective romantic desire: Not all reciprocity is created equal. Psychological Science. 2007;18:317–319. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01897.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feeney BC, Collins NL. Predictors of caregiving in adult intimate relationships: An attachment theoretical perspective. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2001;80:972–994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feingold A. Matching for attractiveness in romantic partners and same-sex friends: A meta-analysis and theoretical critique. Psychological Bulletin. 1988;104:226–235. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley HH. Personal relationships: Their structures and processes. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA. Models of non-independence in dyadic research. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1996;13:279–294. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA, Cook W. Partner effects in relationship research: Conceptual issues, analytic difficulties, and illustrations. Personal Relationships. 1999;6:433–448. [Google Scholar]

- Kunda Z. The case for motivated reasoning. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;108:480–498. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.108.3.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leary MR, Baumeister RF. The nature and function of self-esteem: Sociometer theory. In: Zanna MP, editor. Advances in experimental social psychology. Vol. 32. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2000. pp. 2–51. [Google Scholar]

- Lee L, Loewenstein G, Ariely D, Hong J, Young J. If I’m not hot, are you hot or not? Physical attractiveness evaluations and dating preferences. Psychological Science. 2008;19:669–677. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02141.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maner JK, DeWall CN, Baumeister RF, Schaller M. Does social exclusion motivate interpersonal reconnection? Resolving the “porcupine problem”. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2007;92:42–55. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.92.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marigold DC, Holmes JG, Ross M. More than words: Reframing compliments from romantic partners fosters security in low self-esteem individuals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2007;92:232–248. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.92.2.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray SL, Aloni M, Holmes JG, Derrick JL, Stinson DA, Leder S. Fostering partner dependence as trust-insurance: The implicit contingencies of the exchange script in close relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2009;96:324–348. doi: 10.1037/a0012856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray SL, Derrick J, Leder S, Holmes JG. Balancing connectedness and self-protection goals in close relationships: A levels of processing perspective on risk regulation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2008;94:429–459. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.94.3.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray SL, Griffin DW, Rose P, Bellavia G. For better or worse? Self-esteem and the contingencies of acceptance in marriage. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2006;32:866–882. doi: 10.1177/0146167206286756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray SL, Holmes JG. A leap of faith? Positive illusions in romantic relationships. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1997;23:586–604. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.71.6.1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray SL, Holmes JG. The architecture of interdependent minds: A dyadic motivation-management theory of mutual responsiveness. Psychological Review. doi: 10.1037/a0017015. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray SL, Holmes JG, Aloni M, Pinkus R, Derrick JL, Leder S. Commitment insurance: Compensating for the autonomy costs of interdependence in close relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. doi: 10.1037/a0014562. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray SL, Holmes JG, Collins NL. Optimizing assurance: The risk regulation system in relationships. Psychological Bulletin. 2006;132:641–666. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.5.641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray SL, Holmes JG, Griffin D. The benefits of positive illusions: Idealization and the construction of satisfaction in close relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996a;70:79–98. [Google Scholar]

- Murray SL, Holmes JG, Griffin DW. The self-fulfilling nature of positive illusions in romantic relationship: Love is not blind, but prescient. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996b;71:1155–1180. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.71.6.1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray SL, Holmes JG, Griffin DW. Self-esteem and the quest for felt security: How perceived regard regulates attachment processes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;78:478–498. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.78.3.478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray SL, Holmes JG, Griffin DW, Bellavia G, Rose P. The mismeasure of love: How self-doubt contaminates relationship beliefs. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2001;27:423–436. [Google Scholar]

- Murray SL, Holmes JG, MacDonald G, Ellsworth P. Through the looking glass darkly? When self-doubts turn into relationship insecurities. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;75:1459–1480. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.75.6.1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray SL, Rose P, Bellavia G, Holmes J, Kusche A. When rejection stings: How self-esteem constrains relationship-enhancement processes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002;83:556–573. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.83.3.556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray SL, Rose P, Holmes JG, Derrick J, Podchaski E, Bellavia G, Griffin DW. Putting the partner within reach: A dyadic perspective on felt security in close relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2005;88:327–347. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.88.2.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reis HT, Clark MS, Holmes JG. Perceived partner responsiveness as an organizing construct in the study of intimacy and closeness. In: Mashek D, Aron AP, editors. Handbook of closeness and intimacy. Mahweh, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2004. pp. 201–225. [Google Scholar]

- Rempel JK, Holmes JG, Zanna MP. Trust in close relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1985;49:95–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg M. Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin Z. Liking and loving: An invitation to social psychology. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Rusbult C. A longitudinal test of the investment model: The development (and deterioration) of satisfaction and commitment in heterosexual involvements. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1983;45:172–186. [Google Scholar]

- Rusbult CE, Martz JM, Agnew CR. The investment model scale: Measuring commitment level, satisfaction level, quality of alternatives, and investment size. Personal Relationships. 1998;5:357–391. [Google Scholar]

- Rusbult CE, Van Lange PAM. Interdependence, interaction, and relationships. Annual Review of Psychology. 2003;54:351–375. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strelan P. The prosocial, adaptive qualities of just world beliefs: Implications for the relationship between justice and forgiveness. Personality and Individual Differences. 2007;43:881–890. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SE, Brown JD. Illusion and well-being: A social psychological perspective on mental health. Psychological Bulletin. 1988;103:193–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thibaut JW, Kelley HH. The social psychology of groups. New York: Wiley; 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Tooby J, Cosmides L. Friendship and the banker’s paradox: Other pathways to the evolution of adaptations for altruism. Proceedings of the British Academy. 1996;88:119–143. [Google Scholar]

- Walster E, Walster GW, Berscheid E. Equity: theory and research. Boston: Allyn and Bacon, Inc; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- White GL. Physical attractiveness and courtship progress. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1980;39:660–668. [Google Scholar]

- Williams KD, Cheung CKT, Choi W. Cyberostracism: Effects of being ignored over the Internet. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2001;79:748–762. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.79.5.748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams KD, Sommer KL. Social ostracism by coworkers: Does rejection lead to loafing or compensation? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1997;23:693–706. [Google Scholar]