Abstract

Background

Some health care providers recommend hormone therapy (HT) cessation before mammography to improve performance.

Methods

We performed a randomized clinical trial, the Radiological Evaluation And breast Density (READ) study within an integrated health plan (2004–2007). Women aged 45–80 who used HT at their most recent screening (index) mammogram, were due for a screening (study) mammogram, and were still using HT, were invited to participate. Randomization groups were: 1) no, 2) one-month, or 3) two-month cessation. Women’s willingness to participate was evaluated by age, race, ethnicity, education, hysterectomy, type of HT (unopposed estrogen, ET, estrogen plus progestin, EPT), duration of HT use, body mass index (BMI), breast cancer risk, and breast density.

Results

5861 women were invited to participate; 2999 refused. An additional 169 women agreed to participate, but withdrew before data collection. Compared to women who participated (N=1535), nonparticipants (N= 3168; 2999+169; 54%) were older, were less educated, and had lower BMI (all p<0.05). Among nonparticipants, 1876 (59,2%) were unwilling to stop HT. Among EPT users, women with a first degree relative with a history of breast cancer had lower odds of refusal than women without a family history of breast cancer (aOR=0.71, 95%CI 0.54, 0.93).

Conclusions

Most women were unwilling to stop HT, even for a short period when the intent was to improve mammographic accuracy, and even when informed they could restart HT at any time during the 2-month study. Some factors predicted willingness to stop HT; the magnitude of the differences may not be clinically meaningful.

Keywords: hormone therapy cessation, mammographic screening, mammography performance, estrogen therapy (ET) cessation, estrogen and progestin therapy (EPT) cessation

INTRODUCTION

Currently, some physicians encourage women to stop hormone therapy (HT) before receiving a mammogram in the hopes that short-term cessation will improve mammographic sensitivity and specificity, 1, 2 but little is known about the characteristics of women who might be willing to consider short-term HT cessation. Women who use postmenopausal estrogen plus progesterone (EPT) 3 for 4 or more years and women who have been using estrogen therapy (ET) for extended periods of time may be at increased risk for breast cancer. 4–6 In addition, postmenopausal HT has been shown to increase breast density and increased breast density is a strong risk factor for breast cancer. 7–11

We performed a randomized clinical trial to test the hypothesis that HT cessation for one or two months before a screening mammogram would improve mammographic performance by decreasing breast density and mammography recall rates (recall for additional imaging). This report describes our recruitment experience and women’s willingness to participate in the study. Our trial started recruitment following the publication of findings from the Women’s Health Initiative that EPT increases breast cancer risk. 5 We hypothesized that women who continued HT use in the wake of these findings, particularly women at higher risk for breast cancer, would be interested in, and willing to participate in, a study involving a short-term intervention designed to improve mammographic performance. We also hypothesized that women with more severe menopausal symptoms before starting HT might be less willing to participate, although our recruitment materials specifically stated that any woman who agreed to participate and was randomly assigned to HT cessation but became intolerant of symptoms during the study, could immediately restart her HT.

METHODS

Study Setting

The Radiological Evaluation And breast Density (READ) randomized clinical trial was conducted at Group Health, an integrated health plan in Washington State (US) with approximately 550,000 members. Group Health has a population-based Breast Cancer Screening Program (BCSP) that women are invited to join when they turn 40 years old or when they join Group Health and are age 40 years old or greater.9, 11–13 Demographic and breast cancer risk factor information are gathered via a self-administered questionnaire when women enter the BCSP and then at each subsequent screening mammogram. 9

We used automated administrative data to identify and recruit women aged 45–80 years who were due for a screening mammogram. To be eligible, women had to have had a screening mammogram (“index”) at Group Health within the past two years at which time they reported current HT use on a self-administered questionnaire. Women had to be due for a screening mammogram (“study” mammogram) and to have evidence of continued HT dispensing from Group Health pharmacies in the 6 months before study recruitment. We required that women self report use of HT (denying use of HT was an exclusion criteria) and they were required to have at least 2 fills of a prescription of HT in the prior 6 months to be included in the study. Thus, we had evidence from 2 different sources regarding HT use. Estrogen dose was defined as: medium − 0.0625 mg conjugated estrogens, 1 mg oral estradiol, 0.050 mg transdermal estradiol; low - all doses less than medium; and high - all doses greater than medium.

Women were ineligible if they had a history of myocardial infarction, angina treated with medication, coronary revascularization surgery, stroke, blood clots, breast cancer, mastectomy or breast implants, or dementia or cognitive impairment. We further excluded women with any dispensings of tamoxifen or raloxifene from a Group Health pharmacy because of their potential influence on breast density. Women who had a breast density rating of “entirely fat” (BI-RADS density = 1) on either breast at their index mammogram were also excluded since their density was not likely to influence mammography performance on or off HT.

This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Boards at Group Health and the United States Department of Defense.

Recruitment and Refusal to Participate

We recruited potentially eligible women over a 35-month period from November 2004 through September 2007; enrolling a median of 49 (range 33–75) women per month. Women were initially contacted by mail with an introductory letter and study brochure. They were given the option to call a toll-free number if they did not want to be contacted further by the study team. We contacted potentially eligible women by telephone, invited them to participate, and further screened them for eligibility. We considered a participant enrolled after we verified her eligibility, she returned her consent form and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) authorization, and she was randomized to one of the study groups: 1) no, 2) one-month, or 3) two-month HT cessation.

During telephone screening, we asked women who refused participation to report the main reasons for refusal which included: “not willing to stop HT”, “too busy”, “physician recommended not stopping HT”, “concerned about risks”, “too ill”, “other” and “reason not specified”. Women were classified as “refused participation” if they refused and were never randomized or if they were consented and randomized, but then withdrew before any baseline data were obtained (with the exception of information on reasons for nonparticipation). We grouped these women into two categories: 1) those who refused participation because they were “unwilling to stop HT”, and 2) those who refused participation for all “other reasons”. We only collected one primary reason for refusal for each woman. Since women may have had more than one reason for not wanting to participate, there is likely overlap between the refusal groups. Final percentage of eligible subjects could not be determined as many women refused prior to determining final eligibility.

We modified recruitment materials 12 months into the study to emphasize to women that we welcomed their participation even if they were not sure they could maintain HT cessation, and that they could restart their HT if their symptoms proved intolerable, or for any other reason they ultimately wanted to withdraw from the study.

Data collection

We used self-reported demographic characteristics, duration of HT use, and breast cancer risk information from the Group Health Breast Cancer Surveillance questionnaire 14 completed at the time of the index mammogram, and prior to randomization. Years of enrollment and age were obtained from automated databases. Lifetime Gail model risk score was based on breast cancer risk factors collected at the index mammogram and was calculated using the National Cancer Institute’s (NCI) Breast Cancer Risk Assessment Tool. 15 Reasons for declining study participation were collected and maintained in the study recruitment records. Reasons for taking HT were recorded among study participants: to manage symptoms (including vasomotor symptoms, sleep disturbances, mood, vaginal bleeding, vaginal dryness, and sense of well being), prevent or treat osteoporosis, prevent heart disease, doctor told me to, and “other”.

Outcome

Factors associated with willingness to stop HT 1–2 months before screening mammogram were evaluated including age, race, ethnicity, years of education, hysterectomy, type and duration of HT use at time of recruitment (ET versus EPT), body mass index (BMI), and breast cancer risk (lifetime Gail model risk score; first degree relative with breast cancer). In addition, we evaluated differences in mammographic breast density (using BI-RADS categories) between participants and nonparticipants.

Analysis

We conducted two main comparisons to evaluate the characteristics of: 1) all participants versus nonparticipants; and 2) participants versus the two main groups of non-participants (refused to stop HT; refused for other reason). Chi-square tests were used to compare differences between categorical variables, Wilcoxon rank-sum and Kruskall-Wallis tests for ordinal variables and t-tests and ANOVA for continuous variables. We used multinomial logistic regression models to estimate the odds ratios for each of our two non-participant groups relative to participants (referent group). Logistic regression models were also used to estimate the odds ratios for refusal for the combined non-participant group relative to participants, controlling for those factors that were associated with non-participation in the univariate analyses (p<0.05). All analyses were run both with and without stratification by HT type (ET, EPT) in the 6 months prior to recruitment to the study. Finally we assessed whether modifications to our recruitment materials influenced who was willing to participate.

RESULTS

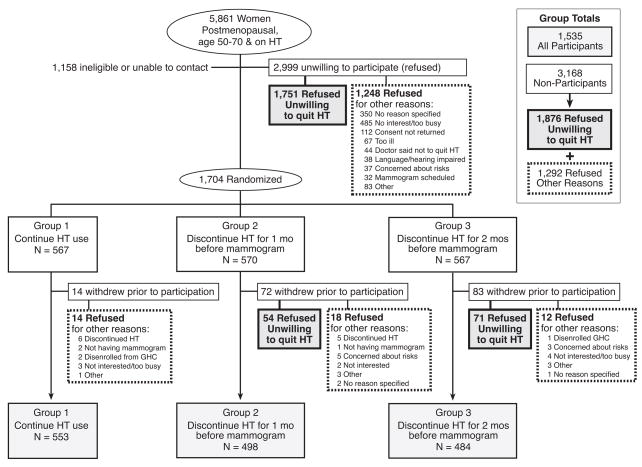

Of the 5861 women contacted to participate, 2999 refused (Figure 1). An additional 169 women agreed to participate and were randomized, but withdrew before data collection and are also considered nonparticipants for this analysis (total nonparticipation 54.1%); 125 of the 169 were unwilling to stop HT. Unwillingness to stop HT was most often cited as the reason for non-participation (n=1876;1751+125) and accounted for 59.2% of 3168 nonparticipants. Other common reasons for refusal were not interested or too busy (15.6%). Nearly one in three potentially eligible women invited to participate (N=1876, 32%) refused or withdrew before any participation because they were unwilling to stop HT use. Of those who enrolled in the study, 47% reported that they had tried to quit taking HT in the past and approximately 75% used at least standard doses of estrogen. There were 247 women (16.1%) who did not list a specific symptom as a reason for HT use. Rather, they stated the reason for HT use as: “to prevent or treat osteoporosis”, “to prevent heart disease”, “doctor told me to”, or “other”. There were 33 women (2.1%) who did not respond to the question about reason for HT use – it is unknown whether this group of women was taking HT for symptoms.

Figure 1.

The Radiological Evaluation And Breast Density (READ) study recruitment and participation

HT = hormone therapy

There were few remarkable distinctions between women who agreed to participate and women who refused, although statistically significant differences were noted (Table 1). Overall, the mean age was 61 years, most women were white with an average BMI of 27.3 kg/m2, most were taking ET (61%), and 52% had had a hysterectomy. Overall characteristics of participants were no different from non-participants with respect to Hispanic race, HT type (ET vs EPT), dose of ET, family history of breast cancer, and mammographic breast density. Women taking EPT were slightly less willing to discontinue use for 1–2 months prior to mammogram as compared to those women taking ET, but differences were not significant (31.5% EPT vs.33.4% ET, p=0.18). All other factors did differ between the two groups, but the magnitudes of the differences were not clinically important. Overall, compared to participants, non-participants were older, had less education and lower BMI.

Table 1.

Characteristics of women who refused to participate vs. those willing to participate in the Radiological Evaluation And Breast Density (READ) study.

| Characteristics | Refused: | Willing to Participate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unwilling to quit HT | Other reason | Overall | ||

| N = 1876 | N= 1292 | N = 3168 | N = 1535 | |

| Age at recruitment, mean (SD) | 60.9 (7.6)† | 61.7 (8.0)‡ | 61.3 (7.7)‡ | 60.4 (7.3) |

| Age at recruitment | ||||

| ≤ 55 years | 26.5 | 22.3 | 24.8 | 26.7 |

| 56–60 | 28.1 | 28.2 | 28.2 | 29.6 |

| 61–65 | 18.1 | 21.0 | 19.3 | 20.9 |

| 66–70 | 14.6 | 11.7 | 13.4 | 12.3 |

| 71+ | 12.8 | 16.9 | 14.5 | 10.6 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Caucasian | 91.5 | 87.8‡ | 90.0 | 91.4 |

| African American | 2.7 | 2.3 | 2.5 | 2.2 |

| Asian | 2.1 | 5.6 | 3.6 | 2.0 |

| Other | 3.6 | 4.4 | 3.9 | 4.5 |

| Hispanic | ||||

| Yes | 2.4 | 3.3 | 2.8 | 2.5 |

| Education | ||||

| ≤High school | 16.7 | 21.6‡ | 18.7† | 14.5 |

| Some college | 38.8 | 37.4 | 38.3 | 40.7 |

| College graduate | 20.3 | 18.8 | 19.7 | 19.7 |

| ≥Graduate school | 24.1 | 22.3 | 23.4 | 25.1 |

| Hysterectomy | ||||

| Yes | 50.8† | 52.4 | 51.4 | 54.3 |

| Type of hormone therapy | ||||

| Estrogen + progestin | 40.1 | 38.9 | 39.6 | 37.6 |

| Unopposed estrogen | 59.9 | 61.2 | 60.4 | 62.4 |

| Self-reported duration of HT use from BSRR at index mammogram | ||||

| ≤ 2 years | 9.3 | 9.3† | 9.3† | 10.3 |

| 3–4 years | 10.8 | 10.6 | 10.7 | 11.7 |

| 5–9 years | 23.5 | 19.7 | 21.9 | 22.7 |

| 10–14 years | 19.6 | 22.1 | 20.6 | 20.1 |

| 15+ years | 36.8 | 38.4 | 37.5 | 35.1 |

| Estrogen dose* | ||||

| Low | 24.8 | 22.2 | 23.8 | 25.3 |

| Medium | 58.7 | 63.4 | 60.6 | 62.5 |

| High | 16.5 | 14.4 | 15.6 | 12.2 |

| Body mass index in kg/m2, at index mammogram | ||||

| (mean, SD) | 27.0 (5.7)‡ | 27.2 (6.0) | 27.1 (5.8)‡ | 27.7 (5.7) |

| (median) | 25.8 | 25.9 | 25.8 | 26.6 |

| <25 | 42.3‡ | 42.7† | 42.4‡ | 37.5 |

| 25 to <30 | 32.9 | 28.8 | 31.2 | 33.1 |

| 30+ | 24.8 | 29.5 | 26.3 | 29.4 |

| Gail model risk score, lifetime | ||||

| <15% | 92.2 | 92.5 | 92.3 | 91.3 |

| 15 – <20% | 5.0 | 5.1 | 5.0 | 5.5 |

| 20 – <30% | 2.2 | 1.8 | 2.1 | 2.2 |

| ≥ 30% | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 1.0 |

| First degree family history | ||||

| Yes | 18.1 | 16.8 | 17.6 | 18.2 |

| Mammographic breast density at index mammogram‡ | ||||

| Scattered fibroglandular | 34.0 | 34.4 | 34.2 | 34.8 |

| Heterogeneously dense | 56.0 | 56.4 | 56.1 | 55.2 |

| Extremely dense | 10.0 | 9.3 | 9.7 | 10.0 |

p<0.01;

p<0.05, comparing group to women willing to participate

Estrogen dose: Medium = 0.0625 mg conjugated estrogens, 1 mg oral estradiol, 0.050 mg transdermal estradiol; Low = any doses < medium: High= any doses > medium.

Univariate analyses evaluated the odds of refusal to participate by HT type and by reason for refusal (Table 2). Type of HT used (ET vs. EPT) did not yield different findings with a few minor exceptions - the confidence intervals were wide; any apparent differences should be interpreted cautiously. Among ET users, older aged women, women with lower BMI, non-Caucasian women, or women with high school education or less were more likely to refuse participation, but the latter two findings were only true for women who refused participation for “other reasons”. Similarly, among women taking EPT, non-Caucasian women or women with high school education or less were more likely to refuse participation for “other reasons”. Women taking EPT had a greater likelihood of participation if they had a first degree relative with breast cancer as compared to those who did not.

Table 2.

Likelihood of refusal to participate versus willing to participate in the Radiological Evaluation And Breast Density (READ) study.

| ET | EPT | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unwilling to quit HT | Refuse: Other reason | Overall | Unwilling to quit HT | Refuse: Other reason | Overall | |

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Age at recruitment | ||||||

| ≤ 55 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 56–60 | 0.89 (0.70, 1.14) | 1.04 (0.79, 1.36) | 0.95 (0.76, 1.18) | 1.03 (0.79, 1.35) | 1.27 (0.93, 1.73) | 1.12 (0.87, 1.43) |

| 61–65 | 0.83 (0.64, 1.07) | 1.13 (0.85, 1.50) | 0.94 (0.74, 1.18) | 0.96 (0.70, 1.32) | 1.33 (0.93, 1.90) | 1.09 (0.82, 1.46) |

| 66–70 | 1.06 (0.80, 1.41) | 0.99 (0.72, 1.37) | 1.04 (0.80, 1.34) | 1.62 (1.08, 2.42) | 1.58 (0.99, 2.51) | 1.60 (1.10, 2.34) |

| 71+ | 1.30 (0.98, 1.73) | 1.90 (1.40, 2.58) | 1.52 (1.18, 1.97) | 1.00 (0.64, 1.59) | 1.85 (1.15, 2.96) | 1.31 (0.87, 1.96) |

| Caucasian | ||||||

| No | 0.98 (0.73, 1.31) | 1.42 (1.05, 1.90) | 1.15 (0.89, 1.49) | 1.01 (0.65, 1.56) | 1.63 (1.06, 2.53) | 1.25 (0.85, 1.84) |

| Yes | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Hispanic | ||||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 0.86 (0.50, 1.50) | 1.46 (0.85, 2.49) | 1.11 (0.69, 1.77) | 1.21 (0.56, 2.60) | 1.18 (0.51, 2.75) | 1.20 (0.59, 2.42) |

| Education | ||||||

| ≤High school | 1.14 (0.87, 1.51) | 1.67 (1.24, 2.25) | 1.35 (1.05, 1.73) | 1.43 (0.97, 2.10) | 1.80 (1.20, 2.71) | 1.57 (1.11, 2.23) |

| Some college | 1.03 (0.82, 1.30) | 1.04 (0.80, 1.34) | 1.04 (0.84, 1.27) | 0.95 (0.73, 1.24) | 1.06 (0.78, 1.43) | 0.99 (0.78, 1.27) |

| College graduate | 1.04 (0.79, 1.38) | 1.10 (0.80, 1.50) | 1.07 (0.83, 1.37) | 1.11 (0.82, 1.51) | 1.05 (0.74, 1.48) | 1.09 (0.83, 1.44) |

| ≥Graduate school | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Self-reported duration of HT use from BSRR at index mammogram | ||||||

| ≤2 years | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 3–4 years | 1.10 (0.69, 1.75) | 0.92 (0.55, 1.56) | 1.02 (0.67, 1.56) | 0.97 (0.66, 1.43) | 1.05 (0.68, 1.60) | 1.00 (0.71, 1.42) |

| 5–9 years | 1.09 (0.73, 1.61) | 0.97 (0.63, 1.50) | 1.04 (0.73, 1.48) | 1.23 (0.87, 1.75) | 0.97 (0.65, 1.43) | 1.13 (0.82, 1.55) |

| 10–14 years | 1.06 (0.72, 1.57) | 1.22 (0.79, 1.87) | 1.13 (0.79, 1.60) | 1.16 (0.80, 1.68) | 1.26 (0.84, 1.88) | 1.20 (0.86, 1.68) |

| 15+ years | 1.22 (0.85, 1.75) | 1.21 (0.82, 1.80) | 1.22 (0.88, 1.68) | 1.21 (0.82, 1.79) | 1.42 (0.93, 2.17) | 1.30 (0.91, 1.85) |

| Body mass index in kg/m2, at index mammogram | ||||||

| <25 | 1.46 (1.18, 1.80) | 1.26 (1.00, 1.59) | 1.37 (1.13, 1.66) | 1.12 (0.84, 1.49) | 1.01 (0.75, 1.38) | 1.07 (0.83, 1.39) |

| 25 to <30 | 1.18 (0.95, 1.47) | 0.94 (0.74, 1.19) | 1.07 (0.88, 1.30) | 1.12 (0.83, 1.52) | 0.80 (0.57, 1.12) | 0.98 (0.75, 1.30) |

| 30+ | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Gail model risk score, lifetime | ||||||

| <15% | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 15 – <20% | 1.10 (0.74, 1.64) | 1.13 (0.74, 1.75) | 1.12 (0.78, 1.60) | 0.65 (0.41, 1.04) | 0.66 (0.39, 1.12) | 0.66 (0.43, 1.00) |

| 20 – <30% | 1.04 (0.59, 1.86) | 0.99 (0.53, 1.87) | 1.03 (0.61, 1.72) | 1.02 (0.46, 2.23) | 0.50 (0.17, 1.46) | 0.81 (0.39, 1.70) |

| ≥ 30% | 0.71 (0.31, 1.66) | 0.71 (0.28, 1.81) | 0.71 (0.34, 1.50) | 0.50 (0.08, 2.99) | 0.37 (0.04, 3.56) | 0.45 (0.09, 2.22) |

| First degree family history | ||||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 1.12 (0.89, 1.40) | 1.10 (0.86, 1.41) | 1.11 (0.90, 1.36) | 0.83 (0.62, 1.11) | 0.64 (0.45, 0.90) | 0.75 (0.57, 0.98) |

| Mammographic breast density at index mammogram‡ | ||||||

| Scattered fibroglandular | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Heterogeneously dense | 1.00 (0.83, 1.20) | 0.94 (0.77, 1.15) | 0.97 (0.82, 1.15) | 1.09 (0.85, 1.39) | 1.22 (0.93, 1.60) | 1.14 (0.91, 1.42) |

| Extremely dense | 1.17 (0.84, 1.63) | 0.90 (0.62, 1.31) | 1.06 (0.78, 1.43) | 0.87 (0.61, 1.25) | 1.03 (0.69, 1.53) | 0.93 (0.67, 1.29) |

OR=Odds Ratio

After controlling for other factors, the odds of participation did vary by type of HT used (ET vs. EPT) with respect to age, BMI, education and first degree relative with breast cancer, but not by race (Table 3). Among women taking ET, older women (≥71 years) or women with low BMI (<25 kg/m2) had higher odds of being unwilling to participate as compared with younger women (≤ 50 years) or women with higher BMI (≥25 kg/m2), respectively. This association was not observed among women taking EPT. Conversely, among women taking EPT, those with a high school education or less had higher odds of refusal compared to women with a graduate school education, and women with a first degree family history of breast cancer had lower odds of refusal compared to women without a family history, These associations were not observed among ET users. Again, the confidence intervals for the estimated OR in the stratified multivariable analysis overlapped, and differences by HT type should be interpreted cautiously.

Table 3.

Multivariable model: likelihood of refusal to participate versus willing to participate in the Radiological Evaluation And Breast Density (READ) study.

| ET | EPT | Overall | |

|---|---|---|---|

| OR* (95% CI) | OR* (95% CI) | OR* (95% CI) | |

| Age at recruitment | |||

| ≤ 55 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 56–60 | 0.94 (0.75, 1.18) | 1.18 (0.91, 1.53) | 1.03 (0.87, 1.23) |

| 61–65 | 0.90 (0.71, 1.15) | 1.12 (0.83, 1.52) | 0.98 (0.81, 1.18) |

| 66–70 | 1.00 (0.76, 1.31) | 1.65 (1.12, 2.43) | 1.15 (0.93, 1.44) |

| 71+ | 1.43 (1.09, 1.88) | 1.25 (0.82, 1.90) | 1.39 (1.11, 1.74) |

| Caucasian | |||

| No | 1.17 (0.89, 1.53) | 1.22 (0.81, 1.84) | 1.18 (0.94, 1.48) |

| Yes | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Education | |||

| ≤High school | 1.22 (0.94, 1.58) | 1.51 (1.05, 2.17) | 1.27 (1.04, 1.57) |

| Some college | 1.04 (0.84, 1.30) | 1.00 (0.77, 1.28) | 1.03 (0.87, 1.21) |

| College graduate | 1.05 (0.81, 1.37) | 1.08 (0.81, 1.44) | 1.07 (0.88, 1.30) |

| ≥Graduate school | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Body mass index in kg/m2, at index mammogram | |||

| <25 | 1.30 (1.06, 1.58) | 1.06 (0.81, 1.39) | 1.22 (1.04, 1.43) |

| 25 to <30 | 0.98 (0.80, 1.20) | 0.98 (0.74, 1.30) | 0.99 (0.84, 1.17) |

| 30+ | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| First degree family history | |||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 1.08 (0.88, 1.33) | 0.71 (0.54, 0.93) | 0.94 (0.79, 1.10) |

OR= Odds ratio, adjusted for all other factors listed in the table

Refining study materials to emphasize our interest in women who were willing to try to quit even if they had doubts about their ability to do so had no impact on who chose to participate (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

We conducted a randomized clinical trial among women due for a screening mammogram to test whether mammographic performance could be improved with short-term HT cessation. One in three potentially eligible women who were invited to participate, knowing that this study might improve mammography performance, refused. Very few differences distinguished women who agreed to participate versus those who refused, emphasizing that among current HT users, overall resistance to HT cessation is strong, even when there may be an immediate personal benefit.

Breast cancer is one of the greatest fears for women considering HT use 16, 17, and this same concern prompts many women to stop HT. 18 Thus, we presumed the majority of women, particularly those taking EPT, would be willing to attempt HT cessation for one or two months on the premise that improved breast cancer screening might be achieved. We were surprised that 54% of women invited to join the study refused and that 59% of women who refused participation did so because of unwillingness to stop HT for 1–2 months, despite recruitment materials explaining that they could resume HT at any time during the study. Perhaps unwillingness to stop HT could be explained by the fact that our study was performed 1–2 years following the major WHI publications describing the risks and benefits of HT. 6, 19 Our other studies have shown the prevalence of HT use in our health plan (and other health plans) fell dramatically after the WHI publications, 3 suggesting that continued HT users are very committed, and might be described as “hard core users”. Indeed, 47% of those who agreed to participate had attempted HT cessation in the past and over 84% acknowledged taking HT for symptoms.

We noted only minor differences in the characteristics of women who refused participation based on use of ET versus EPT, and arguably any statistical differences between these groups were clinically insignificant. Women who refused participation had a lower BMI (predominantly ET) than those who agreed to participate. In addition, women who took EPT and agreed to participate had a higher risk of breast cancer (higher percentage of first degree relatives) than those who refused participation, whereas this finding was not observed among ET users. This finding might suggest that our patients have been educated regarding the Women’s Health Initiative findings and understand that the WHI results showed an increased risk for breast cancer among EPT users and not among ET users. 5, 6, 19

Symptom severity is the most common reason that women report for inability to stop HT. 20 Although the women in our study were not asked specifically if refusal to participate was due to concern for return of severe menopausal symptoms, the work of others would suggest that indeed this is commonly the case. 20, 21 Observational studies show that among women who have been on HT for over 1 year and try to quit, 25% resume HT within 6 months. 22 Ness and colleagues reported that reasons for continued HT use included severe symptoms (34%), personal preference (10%), gynecologist recommended (9%), not documented (11%) and other (3%).21 Although these studies did not specifically address reasons associated with refusal to stop HT for short durations, they suggest that women continue HT use predominantly because of intolerable symptoms, despite known risks. Most likely women who continued or started to use HT following the WHI findings have already made a personal decision that symptom-benefits outweigh risks and potentially they view their personal risks as relatively low.

Others have shown that women who have had a hysterectomy are less likely to quit ET 20 as compared to women who have not had a hysterectomy and are using EPT. Contrary to these findings, we did not find that women taking EPT were more willing to discontinue use for 1–2 months prior to mammogram as compared to those women taking ET (p=0.18), although at baseline, more women overall were taking ET (62%) as compared to women taking EPT (38%). Interestingly, it is well recognized that the characteristics of women who take ET may vary from those of women who take EPT on multiple levels. Women who have had a hysterectomy are more likely to be nonwhite, have higher BMI, lower education and income, increased rates of hypertension, diabetes, hypercholesterolemia and depression, and to be less physically active (all P<0.01). 23,24 Despite these differences, we did not find major differences between those women willing to participate based on estrogen dose or type of HT use (ET versus EPT).

Our study has several limitations. We did not collect data on symptom severity before starting HT, as a number of women had been using HT for many years so we could not fully assess symptom severity as a reason for non-participation. We also did not assess women’s understanding regarding HT risks and benefits, or to what degree they had made an informed decision whether to participate or not, based on their understanding of risks.

Several strengths of the study are noted. Despite multiple publications regarding impact of HT discontinuation on breast density and possible mammographic performance, to our knowledge, no one has investigated women’s willingness to stop HT before screening mammogram. We were careful to maintain details regarding study non-participation. Very little is known about whether a woman would be willing to stop HT for 1–2 months if she might have improved breast cancer screening as a result. Although our study did not find improved recall rates among women who stop HT for 1–2 months before mammogram, versus women who continued HT use, we did find a decrease in breast density, particularly among women who stop HT use for 2 months. 25 If a larger study were to find improved accuracy of mammogram screening with short-term HT cessation, our study is an important reminder that many women are unwilling to stop HT regardless of potential benefits. Currently, targeting HT discontinuation before mammogram to a sub-population of women does not appear feasible as most characteristics between those willing to stop HT for 1–2 months and women unwilling to stop HT varied little. However, with additional patient education regarding breast cancer risks, it is unknown whether high-risk groups (i.e. women on EPT with a first degree relative with breast cancer) might be more willing to attempt short term HT cessation prior to mammogram.

Acknowledgments

Funding source: A population-based trial to assess the effects of short-term hormone therapy (HT) suspension on mammography assessments and breast density, the READ study funded by the Department of Defense (PI, D Buist; DAMD17-03-1-0447). Registered clinical trial number: NCT00117663. Study participants were recruited from the Group Health Breast Cancer Screening Program funded by the National Cancer Institute (PI: D Buist, U01CA63731).

The study team had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the analyses. Drs. Reed and Newton acknowledge research support from Pfizer Pharmaceuticals, Inc. This study could not have been completed without the assistance of Tammy Dodd, Linda Palmer, CCRP, RN, BS or Melissa Rabelhofer. We would further like to thank members of our advisory board: Hermien Watkins, Paula Hoffman, Deb Schiro, and Margrit Schubiger; members of the Data Safety and Monitoring Board: Susan Heckbert, MD, PhD, Chair, University of Washington Department of Epidemiology; Ben Anderson, MD, University of Washington; Mary Anne Rossing, DVM, PhD, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center; Robert D. Rosenberg, MD, University of New Mexico; Thomas Lumley, PhD, University of Washington Department of Biostatistics; and Elizabeth Lin, MD, Group Health Permanente medical monitor. We would further like to thank Robert Karl, MD, Donna White, MD and Jo Ellen Callahan for their support for implementing this trial at Group Health. We also acknowledge Stephen Taplin, MD, MPH for his collaboration in getting this study funded when he was an investigator at Group Health Cooperative.

References

- 1.Boudreau DM, Buist DS, Rutter CM, Fishman PA, Beverly KR, Taplin S. Impact of hormone therapy on false-positive recall and costs among women undergoing screening mammography. Med Care. 2006 January;44(1):62–9. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000188969.83608.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harvey JA, Pinkerton JV, Herman CR. Short-term cessation of hormone replacement therapy and improvement of mammographic specificity. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1997 November 5;89(21):1623–5. doi: 10.1093/jnci/89.21.1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buist DS, Newton KM, Miglioretti DL, et al. Hormone therapy prescribing patterns in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2004 November;104(5 Pt 1):1042–50. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000143826.38439.af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Collaborative Group on Hormone Factors in Breast Cancer. Breast cancer and hormone replacement therapy: collaborative reanalysis of data from 51 epidemiological studies of 52,705 women with breast cancer and 108,411 women without breast cancer. Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer. Lancet. 1997 October 11;350(9084):1047–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chlebowski RT, Hendrix SL, Langer RD, et al. Influence of estrogen plus progestin on breast cancer and mammography in healthy postmenopausal women: the Women’s Health Initiative Randomized Trial. JAMA. 2003 June 25;289(24):3243–53. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.24.3243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, et al. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results From the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002 July 17;288(3):321–33. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carney PA, Miglioretti DL, Yankaskas BC, et al. Individual and combined effects of age, breast density, and hormone replacement therapy use on the accuracy of screening mammography. Ann Intern Med. 2003 February 4;138(3):168–75. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-3-200302040-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Greendale GA, Reboussin BA, Sie A, et al. Effects of estrogen and estrogen-progestin on mammographic parenchymal density. Postmenopausal Estrogen/Progestin Interventions (PEPI) Investigators. Ann Intern Med. 1999 February 16;130(4 Pt 1):262–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-130-4_part_1-199902160-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laya MB, Larson EB, Taplin SH, White E. Effect of estrogen replacement therapy on the specificity and sensitivity of screening mammography. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1996 May 15;88(10):643–9. doi: 10.1093/jnci/88.10.643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McTiernan A, Martin CF, Peck JD, et al. Estrogen-plus-progestin use and mammographic density in postmenopausal women: women’s health initiative randomized trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005 September 21;97(18):1366–76. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rutter CM, Mandelson MT, Laya MB, Seger DJ, Taplin S. Changes in breast density associated with initiation, discontinuation, and continuing use of hormone replacement therapy. JAMA. 2001 January 10;285(2):171–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.2.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taplin SH, Thompson RS, Schnitzer F, Anderman C, Immanuel V. Revisions in the risk-based Breast Cancer Screening Program at Group Health Cooperative. Cancer. 1990 August 15;66(4):812–8. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19900815)66:4<812::aid-cncr2820660436>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taplin SH, Ichikawa L, Buist DS, Seger D, White E. Evaluating organized breast cancer screening implementation: the prevention of late-stage disease? Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004 February;13(2):225–34. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.epi-03-0206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Group Health Breast Cancer Surveillance, Center for Health Studies. [Accessed December 15, 2008];Breast Cancer Surveillance, Center for Health Studies. 2008 July 10; http://www.centerforhealthstudies org/surveillanceproject/public/screening.html. Available at: URL: http://www.centerforhealthstudies.org/surveillanceproject/public/screening.html.

- 15.National Center Institute. [AccessedDecember 15, 2008];Breast Cancer Risk Assessment Tool, An Interactive Tool for Measuring the Risk of Invasive Breast Cancer. 2008 December 15; http://www.cancer gov/bcrisktool/ Available at: URL: www.cancer.gov/bcrisktool/

- 16.Barber CA, Margolis K, Luepker RV, Arnett DK. The impact of the Women’s Health Initiative on discontinuation of postmenopausal hormone therapy: the Minnesota Heart Survey (2000–2002) J Womens Health (Larchmt ) 2004 November;13(9):975–85. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2004.13.975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ettinger B, Pressman A, Silver P. Effect of age on reasons for initiation and discontinuation of hormone replacement therapy. Menopause. 1999;6(4):282–9. doi: 10.1097/00042192-199906040-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buick DL, Crook D, Horne R. Women’s perceptions of hormone replacement therapy: risks and benefits (1980–2002). A literature review. Climacteric. 2005 March;8(1):24–35. doi: 10.1080/13697130500062654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anderson GL, Limacher M, Assaf AR, et al. Effects of conjugated equine estrogen in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy: the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004 April 14;291(14):1701–12. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.14.1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bosworth HB, Bastian LA, Grambow SC, et al. Initiation and discontinuation of hormone therapy for menopausal symptoms: results from a community sample. J Behav Med. 2005 February;28(1):105–14. doi: 10.1007/s10865-005-2721-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ness J, Aronow WS. Prevalence and causes of persistent use of hormone replacement therapy among postmenopausal women: a follow-up study. Am J Ther. 2006 March;13(2):109–12. doi: 10.1097/00045391-200603000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grady D, Sawaya GF. Discontinuation of postmenopausal hormone therapy. Am J Med. 2005 December 19;118(Suppl 12B):163–5. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.09.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Howard BV, Kuller L, Langer R, Manson JE, Allen C, Assaf A, Cochrane BB, Larson JC, Lasser N, Rainford M, Van Horn L, Stefanick ML, Trevisan M Women’s Health Initiative. Risk of cardiovascular disease by hysterectomy status, with and without oophorectomy: the Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study. Circulation. 2005 Mar 29;111(12):1456–8. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000159344.21672.FD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ceausu I, Shakir YA, Lidfeldt J, Samsioe G, Nerbrand C. The hysterectomized woman. Is she special? The women’s health in the Lund area (WHILA) study. Maturitas. 2006 Jan 20;53(2):201–9. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Buist DM, Anderson ML, Reed SD, Aiello Bowles EJ, Fitzgibbons ED, Gandara J, Seger D, Newton KM. EEffects Of Suspending Hormone Therapy For 1–2 Months On Mammography Performance And Mammographic Breast Density: Results From The Radiological Evaluation And Breast Density (Read) Randomized Trial. Ann Int Med. 2009 In press. [Google Scholar]