Abstract

Background

Reported reasons for change or discontinuation of antiretroviral therapy (δART) include adverse events, intolerability and non-adherence. Little is known how reasons for δART differ by gender.

Methods

In a retrospective cohort study, rates and reasons for δART alterations in a large University-based HIV clinic cohort were evaluated. Logistic regression analyses were used to evaluate the relationship between reasons for δART and gender. Cox proportional hazard models were used to investigate time to δART.

Results

In total 631 HIV+ individuals were analyzed. Women (n=164) and men (n=467) were equally likely (53.0% and 54.4%, respectively) to discontinue treatment within 12 month of initiating a new regimen. Reasons for δART, however, were different based on gender - women were more likely to δART due to poor adherence (adj.OR, 1.44; 95% CI: 0.85-2.42), dermatologic symptoms (adj.OR, 2.88; 95% CI: 1.01-8.18), neurological reasons (adj.OR, 1.82; 95% CI: 0.98-3.39), constitutional symptoms (adj. OR, 2.23; 95% CI: 1.10-4.51) and concurrent medical conditions (adj.OR, 2.03; 95% CI: 1.00-4.12).

Conclusions

Although the rates of δART are similar among men and women in clinical practice, the reasons for treatment changes are different based on gender. The potential for unique patterns of adverse events and poor adherence among women requires further investigation.

Keywords: Gender, HIV, Women, Antiretroviral Therapy Discontinuation, Antiretroviral Therapy Change, HAART

Introduction

Since the advent of antiretroviral (ARV) therapy, HIV infected individuals live longer and better lives than ever before 1. Optimal treatment requires that patients adhere to their regimen, in addition to regular monitoring of therapy to avoid side effects and virologic resistance. As a consequence HIV management consists of closely monitoring the reasons that lead to discontinuation or change of ARV regimens (δART).

Within HIV clinical care the number and proportion of women infected with HIV is increasing in the US and worldwide 2, 3. Management of HIV infected women is primarily based on efficacy and tolerability studies conducted in men as women were typically underrepresented in ARV clinical trials 4. Previous research on the effect of ARV therapy in women has predominantly relied on observational cohorts 5-11. However, these studies did not include comparisons of treatment outcomes between men and women. As a consequence, little is known with regard to gender differences in a number of important aspects of treatment, such as ARV tolerability, treatment duration and reasons for δART 6, 12.

A better understanding of gender differences in treatment is warranted in order to provide most efficient care, which is less likely to result in therapy failure during follow-up. From the limited literature available on this topic, we know that women differ from men in a few important aspects of treatment. For example, women seem to delay ART initiation more than men 13, they experience more side effects 7, 12 and appear to metabolize ARV drugs differently 14. Therefore, they may also δART more often than men, as well as being more likely to experience different reasons for changing regimens. The purpose of this study was to investigate gender differences in discontinuation rates and reasons for δART as reported by medical providers.

Methods

Study Population

The University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) 1917 Clinic Cohort is an ongoing prospective observational cohort, which represents HIV-infected patients seeking care at the clinic since its inception in 1988. Physicians and nurse practitioners provide care for over 1200 patients. Data from physician-patient interactions have been manually entered by trained staff or directly downloaded from the hospital laboratory system into the database. The data elements include demographics, medications (including name, dose, start and stop date), clinical problems (including opportunistic infections (OIs)), vital signs, key laboratory data (e.g., CD4 cell counts (CD4), HIV-1 viral load (VL) and triglycerides/cholesterol), safety laboratory results, home health nursing, hospitalizations and insurance status. Each month, data quality control protocols are run and reviewed for erroneous or missing data values. The UAB Institutional Review Board has approved the database protocol.

For this study the following inclusion criteria for patients were used: ≥16 years of age, Highly Active Anti-retroviral Therapy (HAART)-naïve at first clinic visit, entered into clinic for care between January 1995 and August 2004, and clinical follow-up evaluations that included more than one CD4 or VL measurement. A total of 631 HIV+ individuals were included in the final study population. Four types of ART regimens were considered in this study for analysis: 1) Nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors only HAART (NRTI-HAART), 2) Protease inhibitor containing HAART (PI-HAART), 3) Non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor containing HAART (NNRTI-HAART), and 4) other ARV drug regimens including monotherapy (other ART).

Chart reviews were performed to determine the reason(s) for discontinuation of each patient's initial ART regimen. A regimen was considered discontinued/changed if any ARV within the regimen was discontinued or if any additional ARV was added. Changes in therapy lasting less than 14 days were not considered in this analysis. Reasons for discontinuation of ART regimens were evaluated based on provider notes and all reasons given for a discontinuation event or change in ART were evaluated in this study. For the analysis clinically meaningful composite variables for δART regimen were defined (Table 1).

Table 1. Composite Variables for Reasons to Discontinue or Change ARVs.

| Composite Variable | Reasons for Discontinuation/Change of ARVs given by Provider |

|---|---|

| Virologic failure | Failure/viremia, documented resistance, therapy intensification |

| Poor adherence | Self discontinued, poor adherence, therapy simplification, self administration of regimen taken in the past |

| Toxicities | |

| GI related | Nausea/vomiting, diarrhea, pancreatitis, hepatitis/liver failure, lactic acidosis, abdominal pain, constipation, anorexia, belching, abdominal bloating, difficulty swallowing, GI bleeding, rectal bleeding |

| Neurologic/non-psychiatric | Headache, sedation, insomnia, stumbling gait, peripheral neuropathy, dizziness/vertigo |

| Constitutional | Arthralgias, fever/chills, cough, weight loss/cachexia, fatigue, malaise/lethargy, myalgias/muscle pain, edema, night sweats, back/flank pain, lymphadenopathy, chest pain, asthenia/weakness |

| CNS related/Psychiatric | Hypomania, anxiety/stress, depression, vivid dreams, altered mental status/delirium, mental disorder |

| GU related | Renal failure, nephrolithiasis, proteinuria, urinary dysfunction |

| Metabolic/Endocrine | Lipodistrophy, fat redistribution, increased lipids, increased glucose, breast enlargement, hypophosphatemia |

| Dermatologic | Rash, injection site itching/nodules, alopecia, angioedema, flushing |

| Hematologic | Anemia, leucopenia/neutropenia |

| Other medical condition/drug interaction | Pneumonia, hospitalized, improving from previous medical condition caused by drugs, drug abuse/substance abuse, myocardial infarction, upper respiratory infection, erectile dysfunction, concomitant illness, congestive heart failure, meningitis, pregnancy, delivery of child |

Statistical Analysis

Univariate analyses were conducted to investigate the association between δART due to specific reasons reported by providers (Table 1) and gender. Separate logistic regression models were fit to determine factors associated with the discontinuation of the regimen for reasons summarized by the composite variables reported in Table 1, with gender being considered as the primary predictor variable. Covariates considered in this analyses were: race, type of ART regimen (NRTI-HAART, PI-HAART, NNRTI-HAART, Other ART), body mass index (BMI) and CD4 count at ART initiation, and HIV transmission risk category (intravenous drug use (IVDU) and men having sex with men (MSM)).

Cox proportional hazard models were used to assess factors associated with time to discontinuation of initial regimen. A patient's observation time lasted from the date of ART initiation at the clinic to the first discontinuation or change of any ARV drug or the last clinic visit date. The selected predictor variables for time to discontinuation/change included sex, race, type of ART regimen class (NRTI-HAART, PI-HAART, NNRTI-HAART, other ART) and CD4 count at ART initiation.

T-tests were used to evaluate differences in time off regimen per year of follow-up as number of regimens taken per year of follow-up stratified by gender. All analyses were performed using SAS/STAT software, Version 9.1.3 of the SAS System® for Windows XP (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Of the 631 individuals under study 26% (n=164) were women, of whom 78% were black and 22% were white; 74% (467 individuals) were male patients, of whom 40% were black and 60% were white. The average age at start of the first regimen was similar for women and men, while the mean CD4 count was higher for women than for men (p=0.003) and the mean viral load time was lower for women than for men (p=0.015) (Table 2). Only 6% of all individuals were antiretroviral (ARV) therapy experienced at start of the first regimen at our clinic, and the majority initiated their first regimen between 1999 and 2004 (Table 3). There were no differences by gender on the timing and types of regimens received (Table 3).

Table 2. Patient Characteristics stratified by Gender.

| All | Women | Men | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 631 | 164 | 467 | |

| Race (%) | < 0.0001 | |||

| White | 49.8 | 22.0 | 59.5 | |

| Black | 50.2 | 78.1 | 40.5 | |

| Mode of HIV transmission (%) | < 0.0001 | |||

| Heterosexual | 36.5 | 82.3 | 20.3 | |

| IDU | 5.7 | 6.7 | 5.4 | 0.201 |

| MSM | 43.9 | 0 | 59.3 | |

| MSM/IDU | 3.5 | 0 | 4.7 | |

| Other/unknown | 10.5 | 11.0 | 10.3 | |

| Age (years)* | 0.556 | |||

| Mean | 37.7 | 37.3 | 37.8 | |

| Range | 17-69 | 19-69 | 17-69 | |

| Median | 36.7 | 35.5 | 36.9 | |

| HIV Log-viral load* (copies/ml) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 5.4 (±5.7) | 5.3 (±5.4) | 5.4 (±5.8) | 0.015 |

| CD4 cell count* (cells/μl) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 225 (±257) | 276 (±266) | 207 (±251) | 0.003 |

| Years of follow-up | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 4.2 (±2.7) | 4.3 (±2.8) | 4.1 (±2.7) | 0.464 |

Age, HIV Log VL and CD4 count at start of first regimen

Table 3. Description of Treatment History stratified by Gender.

| All | Women | Men | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 631 | 164 | 467 | |

| ARV naïve (%) | 94.0 | 91.5 | 94.9 | 0.116 |

| Year of regimen initiation (%) | 0.581 | |||

| 1995 –1998 | 45.6 | 45.1 | 45.8 | |

| 1999 –2001 | 27.9 | 25.6 | 28.7 | |

| 2002 – 2004 | 26.5 | 29.3 | 25.5 | |

| Type of ART regimen (%) | 0.952 | |||

| NRTI-HAART | 8.9 | 9.8 | 8.6 | |

| PI-HAART | 33.1 | 33.5 | 33.0 | |

| NNRTI-HAART | 33.8 | 32.3 | 34.3 | |

| Other ART | 24.3 | 24.4 | 24.2 | |

| Discontinued initial regimen(%) | 78.1 | 78.1 | 78.2 | 0.977 |

| Mean number of regimens/year (SD) | 1.4 (±1.5) | 1.5 (±1.5) | 1.4 (±1.5) | 0.444 |

| Mean number of days off therapy/year (SD) | 37.7 (±67.0) | 49.0 (±73.8) | 33.8 (±64.1) | 0.020 |

In our cohort 78% discontinued or altered their regimens during an average follow-up time of 4.2 years (SD±2.7) (Table 3). After 12 months of follow-up about half of women (53.0%) and men (54.4%) discontinued/changed their initial regimen, with no significant differences seen when stratifying gender and race (African American (AA) Females: 53.8%; AA Males: 53.4%; White Females: 50.0%; White Males: 55.2%). Overall, women and men were equally likely to discontinue or change. At the time of change/discontinuation 1/3 of women (34%) and men (31.1%) had achieved undetectable virus levels (<50 copies/ml). Whereas the number of regimens per year did not differ by gender, women experienced more days off therapy than men (Table 3). Furthermore, black women reported the highest number of days off regimen per year, 51.2/year, followed by white women, 41.0/year, black men, 37.3/year, and white men, 31.4/year.

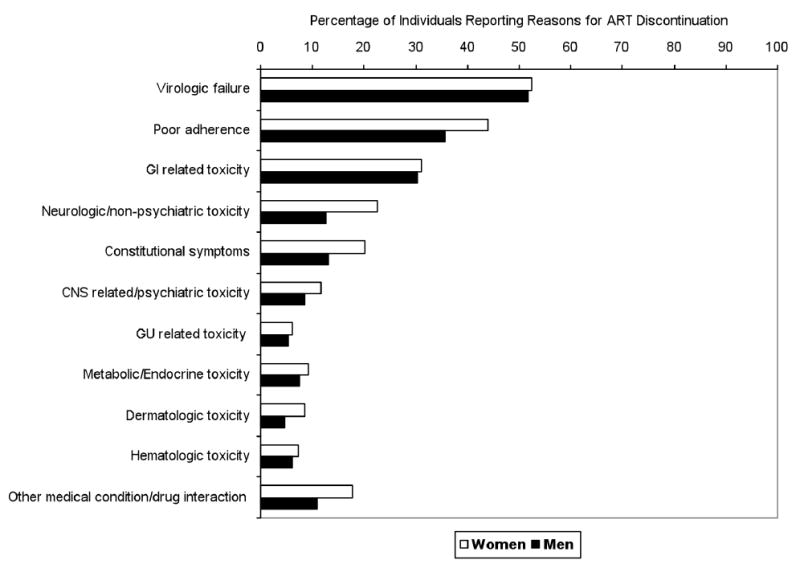

The most common reason for δART regimens was virologic failure (composite variable): about 50% of both men and women had virologic failure documented as one of the reasons for changing regimens (Fig. 1). Individuals who started NNRTI-HAART instead of NRTI-HAART (adj. OR, 0.46; 95% CI: 0.24-0.88) had lower rates of δART due to virologic failure. Individuals on other ARVs had a higher probability of discontinuing a regimen for virologic failure than those on NRTI-HAART (adj. OR, 13.10, 95% CI: 5.55-30.96). As one of the reasons for virologic failure, although numbers involved were small, more men than women discontinued/changed their regimen due to documented resistance (6.9% vs 2.4%, p=0.04).

Fig. 1.

Percentage of women (white bars) vs. men (black bars) reporting Antiretroviral Therapy (ART) discontinuation or change because of reasons listed.

Women were more likely (44%) than men (36%) to discontinue/change their regimen because of reported non-adherence to treatment (composite variable) (adj. OR, 1.44; 95% CI: 0.85-2.42). Individuals who started on NNRTI-HAART (adj. OR, 0.44; 95% CI: 0.22-0.88) compared to those on NRTI-HAART were significantly less likely to discontinue their regimen because of documented poor adherence whereas individuals on other ARVs (adj. OR, 2.32; 95% CI: 1.53-3.95) were more likely to discontinue their regimens due to non-adherence to treatment. Patients who reported IV Drug use as the mode of HIV transmission were significantly more likely to discontinue treatment for adherence reasons (adj. OR, 2.13; 95% CI: 1.15-3.95) than those who did not whereas older patients were less likely to discontinue their treatment due to non-adherence (adj. OR, 0.96; 95% CI: 0.94-0.98).

Multivariate logistic regression analyses demonstrated that women were more likely to δART for neurologic (adj. OR, 1.82; 95% CI: 0.98-3.39) and dermatologic symptoms (adj. OR, 2.88; 95% CI: 1.01-8.18), for constitutional symptoms (adj. OR, 2.23; 95% CI: 1.10-4.51) as well as for other concurrent medical conditions (adj. OR, 2.03; 95% CI: 1.00-4.12) (composite variables) (Fig. 1). Within the composite category of neurologic reasons (see table 1 for definition of composite variables), 15% of women vs. 7% of men discontinued their regimen because of peripheral neuropathy (p=0.002), while about 2% of women vs. 0.4 % of men changed/discontinued their treatment due to experiencing vertigo or dizziness (p=0.04). Within the composite category of constitutional symptoms 9% of women and 4% of men discontinued because of weight loss (p=0.02) and/or fatigue (p=0.05). Within the composite category of CNS-related, psychiatric reasons, women were more likely to discontinue because of depression than men (7% vs 4%, p=0.07). In addition, although the difference was not statistically significant, women tended to discontinue/change regimens more often for rash (7.9% vs 4.5%, p=0.09). As expected, women were more likely to change/discontinue ART due to pregnancy (4.3%) or delivery (2.4%) of a child (categorized as a concurrent medical condition).

Time to discontinuation/change of the first regimen was not significantly different for men and women even after adjusting for race, type of regimen and CD4 count and VL at start of regimen. The only independent factors that had an effect on time to discontinuation/change of the first regimen was the type of regimen that was prescribed (Table 4).

Table 4. Multivariate* Proportional Hazards Regression Analysis of Time to Discontinuation/Change of Initial Regimen.

| Parameter | Hazard Ratio | 95% Hazard Ratio Confidence Limits | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men vs. Women | 1.100 | 0.882 | 1.370 | 0.40 |

| Caucasians vs. African Americans | 0.969 | 0.801 | 1.171 | 0.74 |

| NRTI-HAART vs PI-HAART | 1.358 | 0.972 | 1.896 | 0.07 |

| NNRTI-HAART vs PI-HAART | 0.640 | 0.506 | 0.811 | 0.0002 |

| Other ART vs PI-HAART | 2.104 | 1.673 | 2.647 | <0.0001 |

| CD4 count (50 cells/μl) | 0.993 | 0.974 | 1.012 | 0.45 |

Model was adjusted for all variables listed

Discussion

In the presented cohort of 631 HAART-naïve patients receiving outpatient care in a single urban clinic in the Southeast of the US, women and men were equally likely to discontinue or change their initial HAART regimen, regardless of race, types of regimens and CD4 count at therapy initiation. However, women spent more time off therapy than men, and the data suggests that women were more likely to discontinue or change their regimens due to neurologic, dermatologic or constitutional toxicities or more specifically due to symptoms, such as rash, peripheral neuropathy, fatigue, weight loss and feelings of vertigo/dizziness.

Previous studies have reported conflicting results with regards to the association of gender and discontinuation of therapy, A study by Mocroft et. al. 8 reported that women were less likely to discontinue HAART than men, whereas Monforte et. al. 7 reported that women were more likely to discontinue therapy due to toxicities. Differences between these studies in the characteristics of their populations, the types of regimens, and the definition of adverse event outcomes might explain some of the conflicting results. For example, African American women have been shown to be more likely to discontinue ART than white women 5. However, despite the high proportion of African American women (78% of women) in our cohort we did not see a difference in discontinuation by gender or race.

Whereas general differences in ARV therapy response have been described for both men and women 7, 10, 15, specific reasons for discontinuation or change of therapy as documented by the provider and how they differ by gender have not been reported in detail. When focusing on specific ARVs or side effects, previous studies have shown gender specific differences in ARV side effects, such as rash 16 and depression 17. However, these studies were focusing on specific adverse events as outcomes of interest, rather than exploring the relative contributions of different events to the overall discontinuation rates. No studies to our knowledge have investigated the association of gender differences in therapy discontinuation due to peripheral neuropathy, fatigue or weight loss, although the importance of these side effects as predictors of therapy failure has been established 10. In our study, these were documented more frequently for women than men as reasons for therapy discontinuation or change.

While we identified significant gender differences in reasons for discontinuation or change of therapy, gender differences in the toxicities described, may be also explained by other factors that were significantly different between men and women, i.e., race and progression of HIV disease as shown by VL and CD4 count. Both race and CD4 counts have been described as predictors of adverse events in response to therapy, such as Efavirenz or Nevirapine 18, 19.

Women were more likely to discontinue or change their medications than men due to poor adherence although this difference was not significant in multivariate analysis. In particular, providers were more likely to report that women self-discontinued their medicine – this might explain why women were found to be more days off therapy than men. The number of days off therapy was higher in black women than white women and higher than in white and black men. This emphasizes the importance of strengthening ART adherence strategies and interventions especially in African American women. Previous studies have also found that non-adherence to ART among women was associated with African American race. Other factors included suffering from depression, reluctance to take medications openly at home, and socio-economic status 5, 20. While we did not evaluate socio-economic status or barriers to ART adherence, women in our study were more likely to be African American and to have depression as a reported cause of regimen discontinuation.

The only reason for discontinuation/change in therapy that appeared to be more frequent in men than women was viral resistance. Since women were more likely to be non-adherent and to have more days off therapy than men, this difference may be more likely related to primary drug resistance of the transmitted virus rather than a response to the therapy administered. Although most cohort studies have not identified gender as a predictor for primary drug resistance in recently infected patients 21-24, the Canadian HIV strain and drug resistance surveillance program reported a higher frequency of primary drug resistance in white, male, homosexual populations than any other population group. In our study, white homosexuals accounted for the majority of the male patient population, therefore, it is plausible that the resistance observed in men was primary rather than secondary to suboptimal ARV adherence. However, we did not have data that allowed us to distinguish between primary and secondary drug resistance, nor was resistance testing administered systematically.

While we found no differences in the discontinuation rate by gender, we found that type of regimen was associated with time to initial therapy change or discontinuation. In particular, in comparison to PI-based regimens, NNRTI-based regimens fared the best in delaying the time to regimen change. Therefore, depending on the type of regimen administered, rates of discontinuation may be found to be higher in women than in men. In our study, ART types did not differed significantly by gender, with about 33% of individuals being on PI based regimens, 33% being on NNRTI based regimens, and 9% being on NRTI-based regimens.

The design of this study had several limitations, which need to be considered when interpreting the results. Adverse events leading to discontinuation/change of therapy were those reported by providers and were retrospectively summarized for this study. Therefore, some information on reasons for discontinuation/change may be missing or misclassified in the medical records reviewed. However, all reasons for change/discontinuation were documented by rigorously reviewing the entire record of each patient to minimize the extent of missing information. Furthermore, questionable records were discussed with the providers for clarification. Only adverse events/reasons that led to discontinuation/change of therapy were documented for this study, therefore the frequency of adverse events as a response to therapy may be higher assuming that not every adverse event will lead to therapy change/discontinuation. Therefore, this study did not investigate the overall frequency of specific drug toxicities by gender.

In conclusion, given the increasing predominance of women and in particular African American women in the HIV infected population, documented therapy gaps in women, especially African Americans, is a matter of concern and warrants further detailed investigation. Interventions targeting the prevention of the described adverse events and toxicities need to be developed in order to minimize therapy discontinuation in women. Such interventions will also have an indirect positive effect on adherence patterns given that toxicities might lead to suboptimal adherence to therapy. As suggested by Ofotokun et. al. 25, individualized drug dosages based on drug plasma levels may reduce the disparities in adverse drug events and thus in discontinuation of therapy. Therefore two types of interventions may be needed- one at the provider level – adjusting drug dosage levels to avoid adverse events in response to therapy – and another on the patient level – providing education and resources to stress and support adherence to ART, especially among women who lack the support for taking their medications in their daily life.

Acknowledgments

This research was conducted with the help of the UAB CFAR Grant and the MARY FISHER CARE Fund.

Footnotes

Data from this manuscript has been presented at the following conferences: 6th Annual North American Cohorts Meeting. November 9-10 2005, Washington, DC, USA

2nd North American Congress of Epidemiology. June 21-24 2006, Seattle, WA, USA

References

- 1.Bhaskaran K, Hamouda O, Sannes M, et al. Changes in the risk of death after HIV seroconversion compared with mortality in the general population. JAMA. 2008 Jul 2;300(1):51–59. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prevention DoHA, National Center for HIV/AIDS VH, STD, and TB Prevention, CDC. [10/17/2008];HIV/AIDS surveillance in Women. 2008 May 21; http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/resources/slides/women/index.htm.

- 3.UNAIDS. 2008 Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic. Geneva: UNAIDS; Aug, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Floridia M, Giuliano M, Palmisano L, Vella S. Gender differences in the treatment of HIV infection. Pharmacol Res. 2008 Jul 30; doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2008.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahdieh-Grant L, Tarwater PM, Schneider MF, et al. Factors and temporal trends associated with highly active antiretroviral therapy discontinuation in the Women's Interagency HIV Study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005 Apr 1;38(4):500–503. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000138160.91568.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boulassel MR, Morales R, Murphy T, Lalonde RG, Klein MB. Gender and long-term metabolic toxicities from antiretroviral therapy in HIV-1 infected persons. J Med Virol. 2006 Sep;78(9):1158–1163. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.d'Arminio Monforte A, Lepri AC, Rezza G, et al. Insights into the reasons for discontinuation of the first highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) regimen in a cohort of antiretroviral naive patients. I.CO.N.A. Study Group. Italian Cohort of Antiretroviral-Naive Patients. AIDS. 2000 Mar 31;14(5):499–507. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200003310-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mocroft A, Youle M, Moore A, et al. Reasons for modification and discontinuation of antiretrovirals: results from a single treatment centre. AIDS. 2001 Jan 26;15(2):185–194. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200101260-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moore AL, Sabin CA, Johnson MA, Phillips AN. Gender and clinical outcomes after starting highly active antiretroviral treatment: a cohort study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002 Feb 1;29(2):197–202. doi: 10.1097/00042560-200202010-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O'Brien ME, Clark RA, Besch CL, Myers L, Kissinger P. Patterns and correlates of discontinuation of the initial HAART regimen in an urban outpatient cohort. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003 Dec 1;34(4):407–414. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200312010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yuan Y, L'Italien G, Mukherjee J, Iloeje UH. Determinants of discontinuation of initial highly active antiretroviral therapy regimens in a US HIV-infected patient cohort. HIV Med. 2006 Apr;7(3):156–162. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2006.00355.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Currier JS, Spino C, Grimes J, et al. Differences between women and men in adverse events and CD4+ responses to nucleoside analogue therapy for HIV infection. The Aids Clinical Trials Group 175 Team. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2000 Aug 1;24(4):316–324. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200008010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mocroft A, Gill MJ, Davidson W, Phillips AN. Are there gender differences in starting protease inhibitors, HAART, and disease progression despite equal access to care. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2000 Aug 15;24(5):475–482. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200008150-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dickinson L, Back D, Chandler B, et al. The impact of gender on saquinavir hard-gel/ritonavir (1000/100mg BID) pharmacokinetics and PBMC transporter expression in HIV-1 infected individuals. Paper presented at: 6th International Workshop on Clinical Pharmacology of HIV Therapy; April 28-30, 2005; Quebec City, Quebec, Canada. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murri R, Lepri AC, Phillips AN, et al. Access to antiretroviral treatment, incidence of sustained therapy interruptions, and risk of clinical events according to sex: evidence from the I.Co.N.A. Study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003 Oct 1;34(2):184–190. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200310010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bersoff-Matcha SJ, Miller WC, Aberg JA, et al. Sex differences in nevirapine rash. Clin Infect Dis. 2001 Jan;32(1):124–129. doi: 10.1086/317536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rabkin JG, Johnson J, Lin SH, et al. Psychopathology in male and female HIV-positive and negative injecting drug users: longitudinal course over 3 years. AIDS. 1997 Mar 15;11(4):507–515. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199704000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schackman BR, Ribaudo HJ, Krambrink A, Hughes V, Kuritzkes DR, Gulick RM. Racial differences in virologic failure associated with adherence and quality of life on efavirenz-containing regimens for initial HIV therapy: results of ACTG A5095. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007 Dec 15;46(5):547–554. doi: 10.1097/qai.0b013e31815ac499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Leth F, Andrews S, Grinsztejn B, et al. The effect of baseline CD4 cell count and HIV-1 viral load on the efficacy and safety of nevirapine or efavirenz-based first-line HAART. AIDS. 2005 Mar 25;19(5):463–471. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000162334.12815.5b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sayles JN, Wong MD, Cunningham WE. The inability to take medications openly at home: does it help explain gender disparities in HAART use. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2006 Mar;15(2):173–181. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.15.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Booth CL, Garcia-Diaz AM, Youle MS, Johnson MA, Phillips A, Geretti AM. Prevalence and predictors of antiretroviral drug resistance in newly diagnosed HIV-1 infection. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007 Mar;59(3):517–524. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkl501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grubb JR, Singhatiraj E, Mondy K, Powderly WG, Overton ET. Patterns of primary antiretroviral drug resistance in antiretroviral-naive HIV-1-infected individuals in a midwest university clinic. AIDS. 2006 Oct 24;20(16):2115–2116. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000247579.08449.b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oette M, Kaiser R, Daumer M, et al. Epidemiology of primary drug resistance in chronically HIV-infected patients in Nordrhein-Westfalen, Germany, 2001-2005. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2007 May 4;132(18):977–982. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-979365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Palma AC, Araujo F, Duque V, Borges F, Paixao MT, Camacho R. Molecular epidemiology and prevalence of drug resistance-associated mutations in newly diagnosed HIV-1 patients in Portugal. Infect Genet Evol. 2007 Jun;7(3):391–398. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2007.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ofotokun I, Pomeroy C. Sex differences in adverse reactions to antiretroviral drugs. Top HIV Med. 2003 Mar-Apr;11(2):55–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]