Abstract

Sex hormones have actions in brain regions important for emotion, including the amygdala and prefrontal cortex. Previous studies have shown that cyclic sex hormones and hormone therapy after menopause modify responses to emotional events. Thus, this study examined whether hormone therapy modified emotion-induced brain activity in older women. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), behavioral ratings (valence and arousal), and recognition memory were used to assess responses to emotionally laden scenes in older women currently using hormone therapy (HT) and women not currently using hormone therapy (NONE). We hypothesized that hormones would affect the amount or persistence of emotion-induced brain activity in the amygdala and ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (VLPFC). However, hormone therapy did not affect brain activity with the exception that NONE women showed a modest increase over time in amygdala activity to positive scenes. Hormone therapy did not affect behavioral ratings or memory for emotional scenes. The results were similar when women were regrouped based on whether they had ever used hormone therapy versus had never used hormone therapy. These results suggest that hormone therapy does not modify emotion-induced brain activity, or its persistence, in older women.

Keywords: hormone therapy, estrogen, emotion, amygdala, prefrontal cortex, aging, women, functional magnetic resonance imaging

Introduction

Sex hormones affect emotion in younger and older women. Perceptual identification of fearful faces is worse in the pre-ovulatory phase of the menstrual cycle, when estrogen is high, than during menstruation, when estrogen is low (Pearson and Lewis, 2005). Additionally, amygdala activity induced by negative scenes is lower at the high estrogen phase (as compared to neutral scenes) than the low estrogen phase of the menstrual cycle (Goldstein et al., 2005). Hormones affect emotional responses in older women as well. We recently showed that women on hormone therapy rate negative scenes as more arousing than positive scenes, and find negative scenes more arousing than do women not on hormone therapy (Pruis et al., 2009). Depression and anxiety disorders increase in women during hormonal transitions in their lives, including puberty (Birmaher et al., 1996), the post-partum period (O'Hara and Swain, 1996), and the menopausal transition (Freeman et al., 2006), suggesting that hormones influence mood and emotion. However, some studies report no effects of hormone therapy on emotion, including memory for emotional faces (LeBlanc et al., 2007) and depressed mood, anxiety, and well-being (Nielsen et al., 2006).

Estrogen may influence the structural and functional changes that occur with normal aging in brain areas (e.g. prefrontal cortex, amygdala) that are important for emotional regulation. Structural changes of aging include cortical thinning (Salat et al., 2004); loss of cortical volume (Resnick et al., 2003); loss of white matter in the cortex (Walhovd et al., 2005); and loss of volume in the amygdala (Mu et al., 1999). Estrogen modifies these changes in the prefrontal cortex. Women using estrogen therapy have larger cortical volumes (Erickson et al., 2005), more cortical white matter (Ha et al., 2007), and less shrinkage of the prefrontal cortex (Raz et al., 2004) than women not using estrogen therapy. However, as a counter example, Low et al. (2006) found no differences in grey matter volume, white matter volume, or in frontal atrophy among women currently using hormone therapy, women that used hormone therapy in the past, and women that never used hormone therapy. Fewer studies have examined the effects of estrogen on the human amygdala. Available evidence suggests that amygdala volume is not affected by estrogen either opposed (Low et al., 2006) or unopposed by a progestin (Lord et al., 2008). However, estrogen receptors are present in the human amygdala (Osterlund et al., 2000;Perlman et al., 2004) and may have other functional effects. Certainly, numerous behavioral, neuroanatomical, and physiological effects of estrogen have been found in the prefrontal cortex in studies using nonhuman primate (Hao et al., 2006;Hao et al., 2007;Rapp et al., 2003) and rodent models (for review see Rissman, 2008). A placebo-controlled crossover study (Smith et al., 2006) and a cross-sectional study (Joffe et al., 2006) show that hormone therapy is associated with higher activation in frontal regions during working memory tasks in middle-aged post-menopausal women. Additionally, older post-menopausal women taking estrogen therapy have higher resting cerebral blood flow in the left orbital frontal cortex than women not taking estrogen therapy (Eberling et al., 2004). Thus, sex hormones can act in brain areas involved with emotion and can alter the structure and function of those areas as they age.

Emotion processing differs between younger and older adults. Older adults rate negative scenes as less arousing (Mather et al., 2004) and remember proportionately more positive than negative material (Charles et al., 2003;Leigland et al., 2004), as compared to young adults. They also attend more to positive and less to negative stimuli (Isaacowitz et al., 2006) and have lower physiological responses to emotion than younger adults (Levenson et al., 1994;Neiss et al., 2007;Tsai et al., 2000). Neuroimaging studies suggest that these age differences are due to higher prefrontal activity and/or diminished amygdala activity in response to emotion in older adults. In younger adults, the amygdala is activated most consistently and strongly by negative emotional stimuli, such as negative scenes (Liberzon et al., 2000) and fearful faces (Morris et al., 1996), but it is also activated by positive stimuli (Hamann et al., 1999). The amygdala response decreases over time (i.e. habituates) to repeated emotional stimuli of the same valence category, regardless of whether the stimuli are negative or positive (Breiter et al., 1996;Whalen et al., 1998). The prefrontal cortex is activated by emotion (Lane et al., 1997) and habituates to emotional stimuli in young adults (Wright et al., 2001). However, older adults have less amygdala activation to negative emotional stimuli than younger adults (Mather et al., 2004;Roalf et al., under review;Tessitore et al., 2005) and do not always activate the amygdala when discriminating faces expressing negative emotion (Gunning-Dixon et al., 2003;Iidaka et al., 2002). Older adults activate prefrontal regions in response to emotion, in some cases more so than young adults (Roalf et al., under review;Tessitore et al., 2005). The possibility that hormone therapy contributes to the changes in brain activity induced by emotion in older women has not been examined.

The current study examines whether hormone therapy modifies brain activity, as measured by functional MRI, while viewing emotional scenes. Hormone therapy could modify activation in the prefrontal cortex or amygdala by amount or persistence of activity to repeated emotional stimuli. We also assessed behavioral measures of valence, arousal, and recognition.

Methods

Participants

Women aged 65-85 participated in the study. Participants were recruited through phone contact, from a database of previous study participants, and through advertisements (see participant characteristics in Table 1). Inclusion criteria required that women were healthy and post-menopausal, either currently using hormone therapy (HT; n = 11) or not currently using hormone therapy (NONE; n = 12). Menopausal status and use of hormone therapy was obtained by self-report. All women were many years post-menopausal. HT women were recruited on their physician-prescribed hormone therapy and remained on their hormone regimen during the study. Other inclusion criteria included fluency in English and adequate vision (with correction if necessary) to view computer tasks. Health histories were obtained via phone interview and confirmed in person. Exclusion criteria included: smoking or having quit less than one month from the study date; consuming >3 alcoholic beverages per day; depression score >10 on the Geriatric Depression Scale (Yesavage et al., 1983); Mini-Mental Status Examination score < 26 (Folstein et al., 1975); psychiatric conditions (e.g. schizophrenia or mood disorders); significant medical problems (e.g. uncontrolled hypertension); current use of medications likely to affect cognition (e.g. anti-depressants or anxiolytics); history of neurological problems (e.g. stroke, seizure, or head trauma); and exclusions for MRI, such as claustrophobia and electrical or magnetic metal devices implanted in the body (e.g. pace maker). HT and NONE groups were matched for age, years of education, and the WAIS-R Vocabulary subtest (Wechsler, 1981; see Table 1).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

| HTa | NONEb | EVERc | NEVERd | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 11 | 12 | 16 | 7 |

| Age (years) h | 73.3 (68-84) | 71.6 (65-83) | 73.9 (68-84) | 68.9 (65-74) |

| Education (years) | 15.9 (12-19) | 15.3 (12-18) | 15.2 (12-19) | 16.1 (13-18) |

| WAIS-R Vocabulary (raw scores) | 57.5 (28-66) | 56.9 (38-68) | 55.9 (28-68) | 59.1 (44-65) |

| Geriatric Depression Scale | 2.36 (0-8) | 2.42 (0-8) | 2.75 (0-8) | 1.71 (0-4) |

| Mini-Mental Status Examination | 28.8 (28-30) | 29.3 (28-30) | 29.0 (28-30) | 29.4 (28-30) |

| Mean duration of hormone therapy use (yrs) | 29.5 (5-51) | 8.5 (0.5-18) | 21.1 | NAf |

| Mean time since last hormone therapy use (yrs) | NAf | 14.3 (3-39) | NAf | NAf |

| Used/did not use hormone therapy during menopause (n) | 9/2 | 4/8 | 13/3 | NAf |

| Used unopposed/opposed estrogen (n) | 9/2 | NAf | 10g | NAf |

| Hysterectomye (n) | 7 | 2 | 8 | 1 |

Note: Range is shown in parentheses.

HT = women currently using hormone therapy.

NONE = women not currently using hormone therapy. Seven NONE women had never used hormone therapy in the past; five had.

EVER = women that have ever used any hormone therapy, either currently or in the past.

NEVER = women that have never used any hormone therapy, either currently or in the past.

All women with hysterectomies used unopposed estrogen.

Information not available or not applicable.

Information about type of hormone therapy not available for 3 of the EVER women (they were previously NONE women).

EVER > NEVER, p<0.05

Since five NONE women had used hormone therapy in the past, we did an exploratory re-analysis that grouped the women by those that had ever used hormone therapy for any period of time (EVER) and those that had never used hormone therapy for any period of time (NEVER). With this regrouping, the EVER women were older than NEVER women (mean=74 vs. 69 yrs., respectively), and there were unequal sample sizes. Hormone information about these exploratory groups, as well as the HT and NONE women, can be found in Table 1.

Six additional women were recruited for the study but were dropped from all analyses. Three were dropped due to MRI susceptibility (1 from HT, 2 from NONE). The amygdala is near an air-tissue interface, which makes it prone to susceptibility artifact in EPI-BOLD imaging (Ojemann et al., 1997), especially at high fields (Krasnow et al., 2003). One additional subject was dropped from all analyses because their data was an outlier for amygdala signal change (> 2SD from mean). Two other subjects were dropped as well; one for a large, previously unknown lesion that was discovered during imaging and one for excessive head movement. These six subjects were not included in the demographics above (e.g. final N=11 HT, 12 NONE; 16 EVER, 7 NEVER).

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Oregon Health & Science University. All participants provided written informed consent and were paid for their time and involvement in the study. Authors have no actual or potential conflicts of interest.

Task design

During functional MRI, women viewed 240 scenes (80 negative, 80 neutral, 80 positive) selected from the International Affective Picture System (IAPS; Lang et al., 1999). A large number of scenes were needed, because, in this design, different scenes of the same valence were repeated to assess habituation to that valence category as opposed to an individual exemplar. This is in contrast to other studies where the same stimulus of a single valence was repeated (Breiter et al., 1996;Fischer et al., 2003;Wedig et al., 2005;Wright et al., 2001). These scene sets represented distinct valence categories based on the published norms that were derived from a college-aged sample (Lang et al., 1999). The norms utilize 1 to 9 scales for valence (1 = most negative, 5 = neutral, 9 = most positive) and arousal (1 = least arousing or calming, 5 = neither calming nor arousing, 9 = most arousing). The average normative valence ratings were 2.31 for negative (range: 1.45-2.98), 5.16 for neutral (range: 4.53-5.93), and 7.41 for positive (range: 6.82-8.34) scenes. Negative scenes had lower valence ratings than neutral, which had lower ratings than positive scenes (F (2, 158) = 3157, p < 0.001; pair wise post hoc comparison: ts (79) >38, ps < 0.001). The average normative arousal ratings for the scenes used were 5.83 for negative (range: 4.00-7.35), 3.37 for neutral (range: 2.17-4.93), and 5.09 for positive (range: 3.98-6.65). Negative scenes had higher arousal ratings than positive, which had higher ratings than neutral (F (2, 158) = 213, p < 0.001; pair wise post hoc comparisons: ts (79) > 5.6, ps < 0.001).

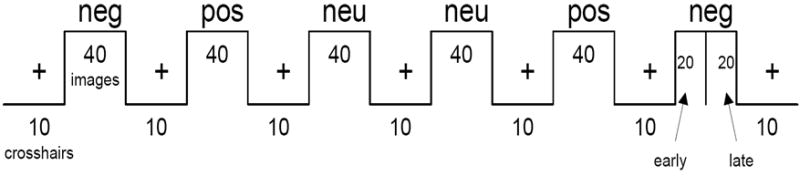

The 240 scenes were separated into 6 blocks of 40 scenes each, two blocks for each valence category. Both blocks were matched for valence (Fs (1, 78) < 0.93, ps > 0.33) and arousal (Fs (1, 78) < 0.41, ps > 0.52). Although the scenes were not chosen specifically for content, both blocks had similar numbers of scenes containing people or animals. Each block was separated by a series of 10 crosshairs, and 10 crosshairs were shown at the beginning and end of the entire block series (70 crosshairs total). Each scene or crosshair appeared for 1500 msec with a 500 msec interstimulus interval (ISI). The last three blocks of unique scenes were shown in the reverse order as the first three blocks with respect to valence category (Figure 1). This was done to help alleviate the possibility of drift in the scanner signal during acquisition, which would preclude interpretation of the habituation analysis. All subjects saw the blocks in the same order. We did not assess attention to each stimulus with a behavioral response during scanning because prior studies show that responding during emotional stimuli modifies activity in the amygdala and prefrontal cortex (Taylor et al., 2003), which would again preclude interpretation of our functional imaging data. To assess habituation, each block of 40 scenes was split in half. The first 20 scenes were designated as “early” scenes and the last 20 as “late” scenes (Fischer et al., 2003;Wedig et al., 2005;Wright et al., 2001). The comparison of early and late scenes served as the index of habituation, such that a loss of activity indicated habituation (early > late), while no change in activity indicated persistence (early = late). The early and late scenes of each block were matched for normative valence (Fs (1, 78) < 2.86, ps > 0.10) and arousal (Fs (1, 78) < 2.33, ps > 0.13) and had similar content with regard to number of people and animals.

Figure 1.

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) design. Subjects viewed 240 scenes in blocks of 40 separated by 10 crosshairs. There were two blocks of each valence category. All subjects saw the blocks in the same order. neg = negative; neu = neutral; pos = positive.

After scanning, subjects were shown the scenes again and rated each one on the 9-point scales for valence and arousal. The scenes were presented in the same order during rating as during the scan. Mean valence and arousal ratings were calculated by taking the average subject ratings across both blocks of each valence.

After a one-week retention interval (mean = 6.96 days, range = 6-7 days), participants performed a yes/maybe/no recognition test with one of two randomly assigned recognition sets containing 120 of the previously viewed scenes and 60 foils. This retention interval ensured that performance would not be at ceiling or floor. There were equal numbers of negative, neutral, and positive scenes in the recognition sets. Participants had not been told that they would be asked to remember the scenes later. Only targets were used to calculate percent correct because the foils were not shown during imaging and thus could not be assigned an “early” or “late” status. Target recognition was calculated as percent correct for only those target scenes for which the subjects responded “yes”. Total recognition included correct responses for targets and foils and was calculated to ensure that subjects were not simply responding “yes” to all scenes.

Imaging procedure and analyses

MRI data were collected with a Siemens 3T TIM Trio scanner (Erlangen, Germany) and 12-channel head coil in the Advanced Imaging Research Center at Oregon Health & Science University. Subjects were positioned supine, headfirst in the scanner and wore earplugs to dampen the noise. Air conductance headphones were used to further dampen scanner noise and to communicate with the subjects from the control room. Structural images were acquired using a magnetization prepared rapid gradient echo (MPRAGE) T1 sequence with the following parameters: repetition time (TR) = 2300 msec; echo time (TE) = 4.38 msec; flip angle (FA) = 12 degrees; field of view (FOV) = 256 mm; matrix= 256 × 256. Slices were: 1 mm thick (no skip), 144 total, collected in a transverse orientation. Functional brain activity was measured using an echo-planar imaging, blood oxygenation level-dependent (EPI-BOLD) sequence with the following parameters: TR = 2000ms; TE = 35 msec; FA = 90 degrees; FOV = 220 mm; matrix= 64 × 64. The 34 slices were 4 mm thick (no skip) and collected in a transverse orientation. For two subjects in the HT group, the EPI-BOLD sequence had TR=2080ms and 36 slices due to operator error during data collection. For all subjects, the length of one TR matched the length of one scene + ISI presentation. A total of 310 volumes were collected.

MRI data were processed and analyzed using Brain Voyager QX 1.9 (Brain Innovations; Maastricht, Netherlands). Functional data were spatially smoothed with a Gaussian filter (FWHM = 8mm) and temporally corrected with a high pass filter and linear trend removal. Slice scan time and 3D motion corrections with sinc interpolations were applied to the functional data. Structural data were collected and reconstructed as 1×1×1 mm voxels. Functional data were coregistered to the structural images, and both were transformed into Talairach space (Talairach and Tournoux, 1988).

Voxel-wise region-of-interest (ROI) analyses were performed on the amygdala and the ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (VLPFC). Data for both ROIs were extracted from Talairach-transformed brains. The amygdala of each subject was defined using a mask that was created based on Talairach boundaries (supplementary Figure1A). The VLPFC ROI was motivated by other studies that found prefrontal activation in response to emotional stimuli (Gutchess et al., 2005;Iidaka et al., 2002;Tessitore et al., 2005;Wright et al., 2001). However, what constitutes the VLPFC, or any PFC region, varies from manuscript to manuscript. Thus, we used the functional data to specify the VLPFC ROI for this study. Within-subject contrasts of each valence category versus baseline for each group yielded prominent bilateral activations in the PFC in similar areas (Supplementary Figure 2A,B,C). We used a contrast of all valence categories versus baseline (i.e. [negative + neutral + positive] − baseline) averaged across both groups to find the central location of this large area of activation that we wanted to quantify (Figure 2D). This contrast was used for this purpose only and was not used to analyze within-or between-group differences. Talairach Daemon software indicated the center of mass for the group-averaged prefrontal activation was +/-40, 4, 24. This ROI was closest in proximity to points labeled ventral (Tessitore et al., 2005) and dorsolateral PFC (Tessitore et al., 2005;Wright et al., 2001) in other papers on emotion. Thus, our prefrontal ROI was comprised of two 20mm cubes centered at these coordinates (supplementary Figure 1B), and we refer to it as VLPFC. The time courses of mean intensity values were extracted from the amygdala and the VLPFC of each individual using a fixed effects model. These values were used to calculate mean percent signal change from baseline (the crosshairs) for each valence category (negative, neutral, positive) and habituation (early, late). The mean percent signal change values were used in within- and between-group comparisons and correlation analyses.

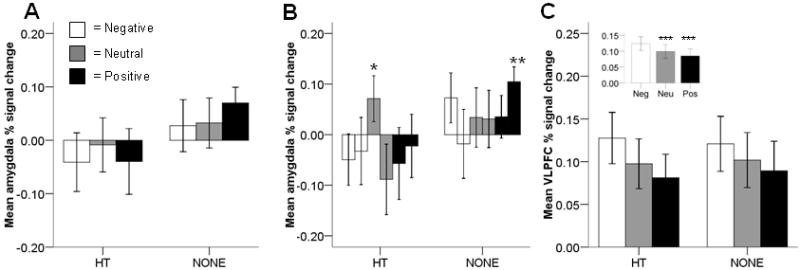

Figure 2.

Region-of-interest % signal change. A: Amygdala % signal change did not differ between women that currently used hormone therapy (HT) and women that did not (NONE). B: Amygdala % signal change was marginally higher for early neutral scenes than for late neutral scenes in HT women (p = 0.06)*. Signal change for late positive scenes in NONE women was significantly different from zero (p = 0.02)**. First bar is early scenes; second bar is late scenes. C: Ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (VLPFC) % signal change did not differ between HT and NONE women. Inset: VLPFC signal change was higher for negative than for neutral or positive scenes (ps < 0.03)***. Neutral and positive scenes did not differ from each other.

Within-subjects whole brain contrasts were performed separately in each group of women for emotion versus neutral (i.e. negative − neutral, positive − neutral) and for each valence category versus baseline (i.e. negative − baseline, neutral − baseline, positive − baseline; supplementary Tables 1-3) using a random effects general linear model on group-averaged, Talairach-transformed functional data. Between-subjects whole brain contrasts were also performed for each emotion versus neutral (e.g. [HT negative − HT neutral] − [NONE negative − NONE neutral], etc.) using a random effects model on Talairach-transformed functional data. Talairach coordinates for the center of mass of each cluster were assigned hemisphere, lobe, region, and a Brodmann Area (BA) number using Talairach Daemon software (Lancaster et al., 2000). The p-value threshold was p = 0.001 for all contrasts, as reported in other studies that use random effects general linear models (Gutchess et al., 2005;Iidaka et al., 2002).

Statistical analyses

A mixed model ANOVA (SPSS version 15.0) was used to compare HT and NONE women for percent signal change in the amygdala and VLPFC, as well as behavioral data, which included valence ratings, arousal ratings, and recognition. The repeated measures were valence category (negative, neutral, positive) and habituation (early, late). A separate mixed model ANOVA was used to assess effects of encoding order on percent signal change (amygdala, VLPFC) and recognition in HT and NONE women; the repeated measure was order (1st through 6th blocks). Paired t tests were used where appropriate to examine main effects and interactions. All p-values reported for post-hoc tests are Bonferroni corrected unless otherwise stated. Two-tailed alpha level was set at 0.05. Some amygdala and VLPFC signal change data did not have a normal distribution. Transformation to normalize the data did not change the findings. Therefore, data were reported as percent signal change without transformation. A mixed model ANOVA including group (HT, NONE), side (right, left), and valence (negative, neutral, positive) found no significant effects of laterality in the amygdala or VLPFC. Therefore, amygdala and VLPFC data were combined across hemispheres. Pearson's R was used for correlations; Bonferroni corrected p < 0.05 was considered significant. The same analysis plan was used for the exploratory EVER/NEVER analysis, but with age as a covariate.

Results

Amygdala activity

Activity in the amygdala did not differ between HT and NONE women (F(1,21)=1.24, p=0.28; Figure 2A). Amygdala activity also did not differ among valence categories (F(2,42)=0.72, p=0.49) or for early vs. late scenes (i.e. habituation; F(1,21)=0.57, p=0.46). There were no hormone status interactions with valence category (F(2,42)=1.51, p=0.23) or habituation (F(1,21)=0.23, p=0.64). However, there was a 3-way interaction with hormone status, valence, and habituation (F(2,42)=3.71, p=0.03). For HT women only, amygdala activity habituated to neutral scenes (early neutral > late neutral); however, this effect was marginal after Bonferroni correction (t(10)=2.67, p=0.06; Figure 2B). Amygdala signal change was not significantly different from baseline with the exception that NONE women show a response to late positive scenes (p=0.02; Figure 2B).

VLPFC activity

Activity in the VLPFC did not differ between HT and NONE women (F(1,21)=0.002, p=0.97; Figure 2C). VLPFC activity did differ across valence categories (inset Figure 2C; F(2,42)=7.96, p=0.001). Negative scenes elicited more signal change than neutral scenes (t(22)=2.87, p=0.03) or positive scenes (t(22)=3.50, p=0.006), which did not significantly differ from each other (t(22)=1.52, p=0.43). VLPFC activity did not differ for early vs. late scenes (F(1,21)=0.80, p=0.38). There were no hormone status interactions with valence category (F(2,42)=0.30, p=0.74) or habituation (F(1,21)=0.04, p=0.85).

Whole brain contrasts

The within-subjects qualitative analysis of negative versus neutral scenes showed numerically more regions of frontal activation (e.g. frontal, cingulate, precentral) in HT than in NONE women (Table 2). There were no regions in either group for which neutral scenes elicited more activation than negative scenes. The within-subjects qualitative analysis of positive versus neutral scenes also showed numerically more regions of frontal activation in HT than in NONE women (Table 2). In fact, positive images did not elicit any frontal activation as compared to neutral in NONE women. Neutral scenes elicited more parietal activation than positive scenes in HT women, but not NONE women. There were no regions in which neutral scenes elicited more activation than positive scenes in NONE women. However, between-subjects contrasts for negative versus neutral and positive versus neutral scenes did not show any regions of significant activation.

Table 2.

Whole brain within-subjects contrast of negative vs. neutral and positive vs. neutral scenes a.

| Group | Left/right | Region | x | y | z b | BA | mm3c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HT | Negative > Neutral | ||||||

| L | Middle Occipital Gyrus | -39 | -67 | 10 | 19 | 3102 | |

| L | Cingulate Gyrus | -22 | -35 | 34 | 31 | 2119 | |

| L | Cingulate Gyrus | -11 | -37 | 38 | 31 | 324 | |

| L | Superior Frontal Gyrus | -21 | 15 | 40 | 8 | 224 | |

| L | Thalamus | -11 | -2 | 10 | NA | 188 | |

| L | Precentral Gyrus | -32 | 5 | 25 | 6 | 171 | |

| L | Cingulate Gyrus | -17 | -52 | 31 | 31 | 130 | |

| L | Thalamus | -8 | -19 | 6 | NA | 80 | |

| R | Precuneus | 12 | -51 | 28 | 31 | 4395 | |

| R | Middle Temporal Gyrus | 42 | -61 | 9 | 37 | 1506 | |

| R | Lentiform Nucleus | 20 | -9 | 5 | NA | 575 | |

| R | Insula | 31 | 7 | 21 | 13 | 280 | |

| R | Middle Occipital Gyrus | 48 | -70 | -7 | 19 | 132 | |

| Neutral > Negative | |||||||

| No significant regions | |||||||

| Positive > Neutral | |||||||

| L | Superior Frontal Gyrus | -14 | -7 | 63 | 6 | 201 | |

| R | Medial Frontal Gyrus | 1 | -18 | 58 | 6 | 783 | |

| R | Medial Frontal Gyrus | 25 | 37 | 19 | 9 | 172 | |

| Neutral > Positive | |||||||

| L | Superior Parietal Lobule | -9 | -69 | 52 | 7 | 210 | |

| R | Precuneus | 18 | -79 | 35 | 7 | 62 | |

| NONE | Negative > Neutral | ||||||

| L | Middle Occipital Gyrus | -38 | -68 | 7 | 19 | 507 | |

| L | Superior Frontal Gyrus | -13 | 45 | 29 | 9 | 434 | |

| L | Superior Parietal Lobule | -9 | -69 | 52 | 7 | 210 | |

| L | Medial Frontal Gyrus | 0 | 44 | 34 | 9 | 96 | |

| L | Lingual Gyrus | -17 | -83 | 3 | 17 | 66 | |

| R | Middle Temporal Gyrus | 43 | -62 | 11 | 37 | 2223 | |

| R | Precuneus | 18 | -79 | 35 | 7 | 62 | |

| Neutral > Negative | |||||||

| No significant regions | |||||||

| Positive > Neutral | |||||||

| L | Middle Temporal Gyrus | -55 | -7 | -15 | 21 | 59 | |

| Neutral > Positive | |||||||

| No significant regions |

Uncorrected p = 0.001 in random effects model.

Coordinates correspond to Talairach space.

Only regions over 50mm3 reported.

Note: n = 11 HT, 12 NONE.

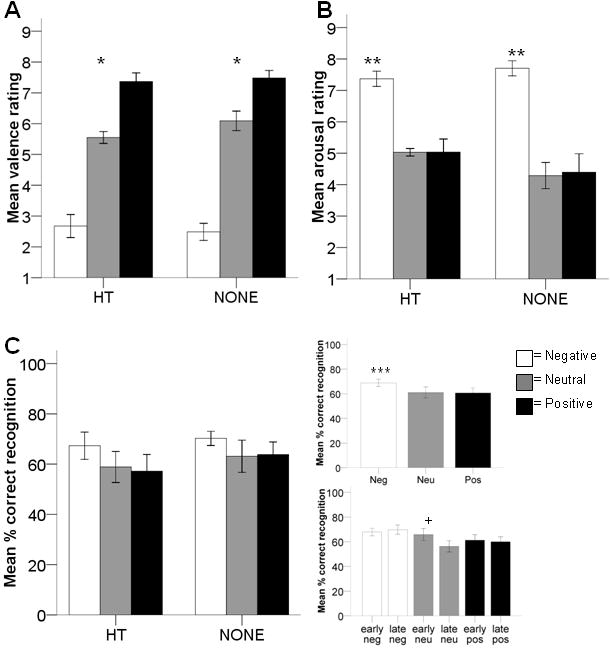

Valence ratings

Valence ratings did not differ between HT and NONE women (F(1,21)=0.50, p=0.49; Figure 3A). As expected, valence ratings did differ across valence categories (F(2,42)=141, p<0.001). Women rated negative scenes as more negative than neutral and positive scenes and rated positive scenes as more positive than neutral or negative scenes (negative < neutral < positive; ts>9.81, ps<0.003). Valence ratings did not differ for early vs. late scenes (e.g. habituation; F(1,21)=0.45, p=0.51). There were no hormone status interactions with valence category (F(2,42)=0.78, p=0.47) or habituation (F(1,21)=0.18, p=0.67).

Figure 3.

Behavioral measures. A: Valence ratings did not differ between women that currently used hormone therapy (HT) and women that did not (NONE). Women rated negative scenes lower than neutral, which were lower than positive (ps < 0.003)*. B: Arousal ratings did not differ between HT and NONE women. Women rated negative scenes as more arousing than neutral or positive (ps < 0.003)**. Ratings for neutral and positive scenes did not differ. C: (left) Percent correct recognition did not differ between HT and NONE women. (top right) Women correctly recognized negative scenes better than positive scenes (p = 0.05)***. Negative did not differ from neutral after Bonferroni correction (p = 0.11); recognition for neutral and positive scenes did not differ. (bottom right) Women recognized more early neutral than late neutral scenes (p = 0.05)+.

Arousal ratings

Arousal ratings did not differ between HT and NONE women (F(1,21)=0.95, p=0.34; Figure 3B). However, arousal ratings did differ across valence category (F(2,42)=45.8, p<0.001). Women rated negative scenes as more arousing than neutral (t(22)=8.53, p<0.003) or positive (t(22)=6.45, p<0.003), which were not significantly different from each other (t(22)=0.26, p=0.80). There was no effect of habituation (i.e. early vs. late) on arousal ratings (F(1,21)=0.01, p=0.91). There were no hormone status interactions with valence category (F(2,42)=1.50, p=0.24) or habituation (F(1,21)=1.24, p=0.28).

Recognition

Recognition memory did not differ between HT and NONE women (F(1,21)=0.46, p=0.51; Figure 3C, left). However, recognition did differ across valence categories (F(2,42)=4.09, p=0.02; Figure 3C, top right). Women remembered more negative scenes than positive scenes (t(22)=2.63, p=0.05). Memory for negative scenes was not significantly higher than neutral scenes after Bonferroni correction (t(22)=2.24, p=0.11), nor was memory for neutral and positive scenes different from each other (t(22)=-0.15, p=0.89). Recognition memory did not differ for early vs. late scenes (F(1,21)=2.83, p=0.11), but this was modified by an interaction with valence category (F(2,42)=3.24, p=0.05). Women remembered early neutral scenes better than late neutral scenes (t(22)=2.60, p=0.05; Figure 3C, bottom right); there were no effects of habituation for recognition of negative or positive scenes (ts<0.54, ps>0.59). There were no hormone status interactions with valence category (F(2,42)=0.17, p=0.85) or habituation (F(1,21)=2.42, p=0.14).

A secondary analysis of encoding order found that recognition differed among the six blocks (F(5,105)=4.62, p=0.001; data not shown). Women remembered the last of the six blocks better than all the other blocks (2nd through 5th blocks: ts>3.03, ps<0.007, uncorrected; 1st block: t=2.08, p=0.049, uncorrected). The other blocks were not different from each other (ts<1.98, ps>0.06). There were no effects of hormone status (F(1,21)=0.81, p=0.38) or any interaction (F(5,105)=0.29, p=0.92).

Correlations

Percent signal change in the amygdala did not significantly correlate with valence ratings, arousal ratings, or recognition for any valence category in HT or NONE women; the same was true for percent signal change in the VLPFC. Percent signal change in the VLPFC also did not significantly correlate with percent signal change in the amygdala for any valence category in either group of women (i.e. VLPFC activity to negative scenes vs. amygdala activity to negative scenes, etc.). However, more VLPFC habituation was related to less amygdala habituation for positive scenes in HT (R =-0.74, p = 0.01), but not NONE women.

Exploratory analyses: regrouping of hormone status

The pattern of statistical results was the same for HT/NONE and EVER/NEVER women for amygdala activity, VLPFC activity, valence ratings, and recognition; however, the pattern of results was different for arousal ratings (Supplementary Figure 4). Arousal ratings differed across valence category (F(2,42)=33.7, p<0.001), but this was modified by a group by valence interaction (F(2,42)=3.20, p=0.05). NEVER women rated neutral (p=0.03) and positive (p=0.02) scenes as more arousing than did the EVER women. Covarying for age in all of these analyses made the group by valence interaction stronger (F(2,40)=4.22, p<0.03), but did not otherwise modify these results.

Discussion

In this study, current use of hormone therapy only had minor effects on emotion-induced brain activity. Amygdala activation to late positive scenes differed from baseline in NONE, but not HT women. Amygdala and VLPFC activity did not otherwise differ between groups. The qualitative within-subjects analyses suggested that HT women activated more frontal regions than NONE women in response to negative and positive emotion, but the between subjects analyses found no regions that differed between groups. Additionally, current use of hormone therapy did not influence affective ratings (valence and arousal) or memory. However, the exploratory analysis of EVER vs. NEVER women revealed that hormone therapy may lower arousal for positive scenes and neutral, but otherwise the pattern of brain activation and behavioral results were the same as HT vs. NONE women. Finally, more VLPFC habituation was related to less amygdala habituation for positive scenes in HT, but not NONE women.

The data here suggest that hormone loss or replacement does not affect emotion-induced amygdala activity. One explanation may lie in the fact that the amygdala responded very little to the emotional scenes in this study. Other studies (Fischer et al., 2005;Mather et al., 2004;Tessitore et al., 2005), including our own (Roalf et al., under review), find that the amygdala responds less to emotional stimuli in older adults than in younger adults (Tessitore et al., 2005) or not at all (Gunning-Dixon et al., 2003;Iidaka et al., 2002). The current study suggests that hormone therapy does not modify the lower amygdala activity found in aging, at least in older women. This is in stark contrast to studies of younger adults, where the amygdala does respond to emotional stimuli (Breiter et al., 1996;Hamann et al., 1999;Lane et al., 1997;Mather et al., 2004;Morris et al., 1996) and is modified by hormone state in young women (Goldstein et al., 2005). Additionally, in our current study, NONE women had activity in response to late positive scenes. This could support a positivity bias in aging as others have reported (Mather and Knight, 2005), but additional studies would be needed to verify this idea, since our behavioral data did not show a positivity bias.

In contrast to the amygdala, the VLPFC responded to all valence categories. Older adults activate prefrontal regions in response to negative emotion more than younger adults (Roalf et al., under review;Tessitore et al., 2005). In the elderly, but not the young, the VLPFC differentially responds to valence (negative > neutral or positive; Roalf et al., under review), but we show here that this was not affected by hormone status in older women. Our qualitative between-subjects analyses found no frontal regions that differed between HT and NONE women. This complements our quantitative ROI analyses, which showed no effects of hormone status in VLPFC activation. Collectively, these results indicate that current use of hormone therapy does not modify the age-related amplification of prefrontal activity.

Women had better recognition for negative as compared to positive scenes, but hormone therapy did not affect recognition. The effects of hormone therapy on memory in the literature are variable. Verbal (Kampen and Sherwin, 1994) and visual (Smith et al., 2001) memory are enhanced in older women using long-term hormone therapy, while scene, face, and word recognition are not affected by short-term estrogen therapy (Schiff et al., 2005). Our previous work suggests that memory for emotional stimuli, including faces (LeBlanc et al., 2007) and scenes (Pruis et al., 2009), is not affected by short- and long-term hormone therapy, respectively. This would suggest that potential memory benefits of hormone therapy may only occur for specific types of information, but not including emotional information. Alternatively, memory benefits may be dependent on hormone therapy during the menopausal transition (Sherwin, 2006a; Sherwin, 2006b). We do not think that that was not the case for the emotional scenes reported here, as most HT and EVER women had used hormone therapy during menopause, but their memory did not differ from NONE and NEVER women, respectively. However, a study that recruits women at the appropriate time in menopause and controls hormone therapy initiation would be needed to fully address that hypothesis.

The study design may have modified memory for negative and neutral images. The last three blocks were shown in the reverse order as the first three blocks (see Figure 1 & methods), which left negative images at the beginning and end of the series, leaving the possibility of primacy and/or recency effects on memory. We found that the last block of scenes was remembered better than all the other blocks, suggesting a recency effect for memory. This may have affected memory for negative scenes; however, we do not think this precludes interpretation of hormone effects, which is the focus of this study, because the recent exposure to negative scenes did not differ between the groups. The study design also yielded consecutive neutral blocks, leaving the possibility that doubling the number of consecutive scenes is what allowed us to detect habituation in memory to neutral, but not negative or positive scenes. Exploratory analyses (not shown) suggested the habituation to neutral scenes may be driven by the habituation in the 2nd block of neutral scenes. However, this effect was marginal, and this analysis only included half the amount of data, since each block of pictures was analyzed separately, which lowered the power to detect significant differences.

In this study, we did not find that current use of hormone therapy affected valence or arousal ratings, which differs from our previous report (Pruis et al., 2009). There are several differences between the two studies. First, the negative scenes in this study had higher normative arousal ratings than the neutral or positive scenes, in part to try to increase the likelihood of obtaining amygdala activity. The normative arousal ratings in the previous study were the same across valence categories (Pruis et al., 2009). Thus, it may be that potential hormone effects on arousal in this study are overridden by the highly arousing nature of the negative stimuli. Second, women in the previous study viewed individual scenes from each valence category in random order, while in the present study they viewed blocks of scenes from the same valence category. The block design was necessary to examine habituation, but may not lend itself to studying behavioral ratings of arousal. However, our exploratory re-grouping of the women into EVER and NEVER users did reveal effects of hormone use on arousal that were similar to our previous study. Women without hormone therapy in the previous study and NEVER users in this study both rated positive images as more arousing than their respective counterparts with hormones. It may be that hormone therapy during a critical window in menopause (Sherwin, 2006b; Sherwin, 2006a) affect arousal later in life; however, a study designed specifically for this purpose is needed.

There are other limitations of this study. The cross-sectional design for hormone therapy and the small within group sample size could limit our ability to detect statistically significant effects (Savoy, 2006). However, our sample size is comparable to other fMRI studies of aging (Gunning-Dixon et al., 2003;Iidaka et al., 2002;Rosen et al., 2002) and emotion (Breiter et al., 1996;Canli et al., 2000;Fischer et al., 2003;Wright et al., 2001). Additionally, our groups of women do not allow us to distinguish any special effects of hormone therapy initiated because of hysterectomy, or whether particular timing, doses, or durations would provide different results. Finally, we did not include a measure of attention compliance during collection of the fMRI data, so we cannot exclude that as a factor in our null results; however, lack of attention would not explain our differential effect of valence in the VLPFC.

In summary, hormone therapy did not have large effects on amygdala or VLPFC activity, or maintenance of activity in either region. Current use of hormone therapy did not affect recognition, valence, or arousal ratings; however, having used hormone therapy in the critical window may affect arousal.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1. Regions-of-interest (ROIs). Coronal (top), sagittal (middle), and axial (bottom) views of the amygdala (A) and ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (B) ROIs on group-averaged anatomical scans.

Supplementary Figure 2. Activity from whole brain within-subjects analyses. A: Negative versus baseline. B: Neutral versus baseline. C: Positive versus baseline. D: Average of all valence categories versus baseline (i.e. [negative + neutral + positive] − baseline) averaged across both groups. The anterior area of activity at +/-40, 4, 24 (the ventrolateral prefrontal cortex) was quantified using a region-of-interest analysis.

Supplementary Figure 3. Data from EVER versus NEVER exploratory analysis. A: Amygdala % signal change did not differ between women that had ever used hormone therapy (EVER) and women that had never used hormone therapy (NEVER). B: Amygdala % signal change was higher for early neutral scenes than for late neutral scenes in EVER women (p = 0.02)*. First bar is early scenes; second bar is late scenes. C: Ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (VLPFC) % signal change did not differ between EVER and NEVER women. Inset: VLPFC signal change was higher for negative than for neutral or positive scenes (ps < 0.03)**. Neutral and positive scenes did not differ from each other. D: Valence ratings did not differ between EVER and NEVER women. Women rated negative scenes lower than neutral, which were lower than positive (ps < 0.003)***. E: NEVER women rated neutral and positive scenes as more arousing than did EVER women (ps< 0.04)+. Both groups of women rated negative scenes as more arousing than neutral or positive (ps < 0.003)++. Ratings for neutral and positive scenes did not differ. F: (left) Percent correct recognition did not differ between EVER and NEVER women. (top right) Women correctly recognized negative scenes better than positive scenes (p = 0.05)+++. Negative did not differ from neutral after Bonferroni correction (p = 0.10); recognition for neutral and positive scenes did not differ. (bottom right) Women recognized more early neutral than late neutral scenes (p = 0.05)‡. First bar is early scenes; second bar is late scenes.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH Grant R01 AG12611 & AG18843 (J.J.), Multidisciplinary Training Grant in Neuroscience (5T32NS007466 to T.P.), National Defense Science and Engineering Graduate Fellowship funded by the Department of Defense (T.P.), ARCS Foundation, Inc. Portland Chapter (T.P.), and Neuroscience of Aging Training Grant (T32 AG023477 to D.R.). We thank the Advanced Imaging Research Center at OHSU for assistance with neuroimaging.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Birmaher B, Ryan ND, Williamson DE, Brent DA, Kaufman J, Dahl RE, Perel J, Nelson B. Childhood and adolescent depression: a review of the past 10 years. Part I. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996;35:1427–1439. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199611000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breiter HC, Etcoff NL, Whalen PJ, Kennedy WA, Rauch SL, Buckner RL, Strauss MM, Hyman SE, Rosen BR. Response and habituation of the human amygdala during visual processing of facial expression. Neuron. 1996;17:875–887. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80219-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canli T, Zhao Z, Brewer J, Gabrieli JD, Cahill L. Event-related activation in the human amygdala associates with later memory for individual emotional experience. J Neurosci. 2000;20:RC99. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-19-j0004.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles ST, Mather M, Carstensen LL. Aging and emotional memory: the forgettable nature of negative images for older adults. J Exp Psychol Gen. 2003;132:310–324. doi: 10.1037/0096-3445.132.2.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberling JL, Wu C, Tong-Turnbeaugh R, Jagust WJ. Estrogen- and tamoxifen-associated effects on brain structure and function. Neuroimage. 2004;21:364–371. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2003.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson KI, Colcombe SJ, Raz N, Korol DL, Scalf P, Webb A, Cohen NJ, McAuley E, Kramer AF. Selective sparing of brain tissue in postmenopausal women receiving hormone replacement therapy. Neurobiol Aging. 2005;26:1205–1213. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer H, Sandblom J, Gavazzeni J, Fransson P, Wright CI, Backman L. Age-differential patterns of brain activation during perception of angry faces. Neurosci Lett. 2005;386:99–104. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer H, Wright CI, Whalen PJ, McInerney SC, Shin LM, Rauch SL. Brain habituation during repeated exposure to fearful and neutral faces: a functional MRI study. Brain Res Bull. 2003;59:387–392. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(02)00940-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman EW, Sammel MD, Lin H, Nelson DB. Associations of hormones and menopausal status with depressed mood in women with no history of depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:375–382. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.4.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein JM, Jerram M, Poldrack R, Ahern T, Kennedy DN, Seidman LJ, Makris N. Hormonal cycle modulates arousal circuitry in women using functional magnetic resonance imaging. J Neurosci. 2005;25:9309–9316. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2239-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunning-Dixon FM, Gur RC, Perkins AC, Schroeder L, Turner T, Turetsky BI, Chan RM, Loughead JW, Alsop DC, Maldjian J, Gur RE. Age-related differences in brain activation during emotional face processing. Neurobiol Aging. 2003;24:285–295. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(02)00099-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutchess AH, Welsh RC, Hedden T, Bangert A, Minear M, Liu LL, Park DC. Aging and the neural correlates of successful picture encoding: frontal activations compensate for decreased medial-temporal activity. J Cogn Neurosci. 2005;17:84–96. doi: 10.1162/0898929052880048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha DM, Xu J, Janowsky JS. Preliminary evidence that long-term estrogen use reduces white matter loss in aging. Neurobiol Aging. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamann SB, Ely TD, Grafton ST, Kilts CD. Amygdala activity related to enhanced memory for pleasant and aversive stimuli. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:289–293. doi: 10.1038/6404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao J, Rapp PR, Janssen WG, Lou W, Lasley BL, Hof PR, Morrison JH. Interactive effects of age and estrogen on cognition and pyramidal neurons in monkey prefrontal cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:11465–11470. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704757104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao J, Rapp PR, Leffler AE, Leffler SR, Janssen WG, Lou W, McKay H, Roberts JA, Wearne SL, Hof PR, Morrison JH. Estrogen alters spine number and morphology in prefrontal cortex of aged female rhesus monkeys. J Neurosci. 2006;26:2571–2578. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3440-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iidaka T, Okada T, Murata T, Omori M, Kosaka H, Sadato N, Yonekura Y. Age-related differences in the medial temporal lobe responses to emotional faces as revealed by fMRI. Hippocampus. 2002;12:352–362. doi: 10.1002/hipo.1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacowitz DM, Wadlinger HA, Goren D, Wilson HR. Is there an age-related positivity effect in visual attention? A comparison of two methodologies. Emotion. 2006;6:511–516. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.6.3.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joffe H, Hall JE, Gruber S, Sarmiento IA, Cohen LS, Yurgelun-Todd D, Martin KA. Estrogen therapy selectively enhances prefrontal cognitive processes: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study with functional magnetic resonance imaging in perimenopausal and recently postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2006;13:411–422. doi: 10.1097/01.gme.0000189618.48774.7b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kampen DL, Sherwin BB. Estrogen use and verbal memory in healthy postmenopausal women. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;83:979–983. doi: 10.1097/00006250-199406000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krasnow B, Tamm L, Greicius MD, Yang TT, Glover GH, Reiss AL, Menon V. Comparison of fMRI activation at 3 and 1.5 T during perceptual, cognitive, and affective processing. Neuroimage. 2003;18:813–826. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(03)00002-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster JL, Woldorff MG, Parsons LM, Liotti M, Freitas CS, Rainey L, Kochunov PV, Nickerson D, Mikiten SA, Fox PT. Automated Talairach atlas labels for functional brain mapping. Hum Brain Mapp. 2000;10:120–131. doi: 10.1002/1097-0193(200007)10:3<120::AID-HBM30>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane RD, Reiman EM, Bradley MM, Lang PJ, Ahern GL, Davidson RJ, Schwartz GE. Neuroanatomical correlates of pleasant and unpleasant emotion. Neuropsychologia. 1997;35:1437–1444. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(97)00070-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang PJ, Bradley MM, Cuthbert BN. The International Affective Picture System (IAPS): Instruction manual and affective ratings. University of Florida; Gainesville, FL: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- LeBlanc ES, Neiss MB, Carello PE, Samuels MH, Janowsky JS. Hot flashes and estrogen therapy do not influence cognition in early menopausal women. Menopause. 2007;14:191–202. doi: 10.1097/01.gme.0000230347.28616.1c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leigland LA, Schulz LE, Janowsky JS. Age related changes in emotional memory. Neurobiol Aging. 2004;25:1117–1124. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2003.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levenson RW, Carstensen LL, Gottman JM. The influence of age and gender on affect, physiology, and their interrelations: a study of long-term marriages. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1994;67:56–68. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.67.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberzon I, Taylor SF, Fig LM, Decker LR, Koeppe RA, Minoshima S. Limbic activation and psychophysiologic responses to aversive visual stimuli. Interaction with cognitive task. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2000;23:508–516. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(00)00157-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Buss C, Lupien SJ, Pruessner JC. Hippocampal volumes are larger in postmenopausal women using estrogen therapy compared to past users, never users and men: a possible window of opportunity effect. Neurobiol Aging. 2008;29:95–101. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Low LF, Anstey KJ, Maller J, Kumar R, Wen W, Lux O, Salonikas C, Naidoo D, Sachdev P. Hormone replacement therapy, brain volumes and white matter in postmenopausal women aged 60-64 years. Neuroreport. 2006;17:101–104. doi: 10.1097/01.wnr.0000194385.10622.8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mather M, Canli T, English T, Whitfield S, Wais P, Ochsner K, Gabrieli JD, Carstensen LL. Amygdala responses to emotionally valenced stimuli in older and younger adults. Psychol Sci. 2004;15:259–263. doi: 10.1111/j.0956-7976.2004.00662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mather M, Knight M. Goal-directed memory: the role of cognitive control in older adults' emotional memory. Psychol Aging. 2005;20:554–570. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.20.4.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JS, Frith CD, Perrett DI, Rowland D, Young AW, Calder AJ, Dolan RJ. A differential neural response in the human amygdala to fearful and happy facial expressions. Nature. 1996;383:812–815. doi: 10.1038/383812a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mu Q, Xie J, Wen Z, Weng Y, Shuyun Z. A quantitative MR study of the hippocampal formation, the amygdala, and the temporal horn of the lateral ventricle in healthy subjects 40 to 90 years of age. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1999;20:207–211. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neiss MB, Leigland LA, Carlson NE, Janowsky JS. Age differences in perception and awareness of emotion. Neurobiol Aging. 2009;30:1305–1313. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen TF, Ravn P, Pitkin J, Christiansen C. Pulsed estrogen therapy improves postmenopausal quality of life: a 2-year placebo-controlled study. Maturitas. 2006;53:184–190. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2005.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Hara MW, Swain AM. Rates and risk of postpartum depression-- a meta analysis. International Review of Psychiatry. 1996;8:37. [Google Scholar]

- Ojemann JG, Akbudak E, Snyder AZ, McKinstry RC, Raichle ME, Conturo TE. Anatomic localization and quantitative analysis of gradient refocused echo-planar fMRI susceptibility artifacts. Neuroimage. 1997;6:156–167. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1997.0289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osterlund MK, Keller E, Hurd YL. The human forebrain has discrete estrogen receptor alpha messenger RNA expression: high levels in the amygdaloid complex. Neuroscience. 2000;95:333–342. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00443-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson R, Lewis MB. Fear recognition across the menstrual cycle. Horm Behav. 2005;47:267–271. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlman WR, Webster MJ, Kleinman JE, Weickert CS. Reduced glucocorticoid and estrogen receptor alpha messenger ribonucleic acid levels in the amygdala of patients with major mental illness. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;56:844–852. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruis TA, Neiss MB, Leigland LA, Janowsky JS. Estrogen modifies arousal but not memory for emotional events in older women. Neurobiol Aging. 2009;30:1296–1304. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapp PR, Morrison JH, Roberts JA. Cyclic estrogen replacement improves cognitive function in aged ovariectomized rhesus monkeys. J Neurosci. 2003;23:5708–5714. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-13-05708.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raz N, Rodrigue KM, Kennedy KM, Acker JD. Hormone replacement therapy and age-related brain shrinkage: regional effects. Neuroreport. 2004;15:2531–2534. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200411150-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick SM, Pham DL, Kraut MA, Zonderman AB, Davatzikos C. Longitudinal magnetic resonance imaging studies of older adults: a shrinking brain. J Neurosci. 2003;23:3295–3301. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-08-03295.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rissman EF. Roles of oestrogen receptors alpha and beta in behavioural neuroendocrinology: beyond Yin/Yang. J Neuroendocrinol. 2008;20:873–879. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2008.01738.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roalf DR, Pruis TA, Stevens AA, Janowsky JS. More is less: Emotion-induced prefrontal cortex activity habituates in aging. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2009.10.007. under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen AC, Prull MW, O'Hara R, Race EA, Desmond JE, Glover GH, Yesavage JA, Gabrieli JD. Variable effects of aging on frontal lobe contributions to memory. Neuroreport. 2002;13:2425–2428. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200212200-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salat DH, Buckner RL, Snyder AZ, Greve DN, Desikan RS, Busa E, Morris JC, Dale AM, Fischl B. Thinning of the cerebral cortex in aging. Cereb Cortex. 2004;14:721–730. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhh032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savoy RL. Using small numbers of subjects in fMRI-based research. IEEE Eng Med Biol Mag. 2006;25:52–59. doi: 10.1109/memb.2006.1607669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiff R, Bulpitt CJ, Wesnes KA, Rajkumar C. Short-term transdermal estradiol therapy, cognition and depressive symptoms in healthy older women. A randomised placebo controlled pilot cross-over study. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2005;30:309–315. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2004.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherwin BB. Estrogen and cognitive aging in women. Neuroscience. 2006a;138:1021–1026. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.07.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherwin BB. The Critical Period Hypothesis: Can it explain discrepancies in the oestrogen-cognition literature? J Neuroendocrinol. 2006b;19:77–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2006.01508.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith YR, Giordani B, Lajiness-O'Neill R, Zubieta JK. Long-term estrogen replacement is associated with improved nonverbal memory and attentional measures in postmenopausal women. Fertil Steril. 2001;76:1101–1107. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(01)02902-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith YR, Love T, Persad CC, Tkaczyk A, Nichols TE, Zubieta JK. Impact of combined estradiol and norethindrone therapy on visuospatial working memory assessed by functional magnetic resonance imaging. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:4476–4481. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talairach J, Tournoux P. Co-planar Sterotaxic Atlas of the Human brain. Thieme; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SF, Phan KL, Decker LR, Liberzon I. Subjective rating of emotionally salient stimuli modulates neural activity. Neuroimage. 2003;18:650–659. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(02)00051-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tessitore A, Hariri AR, Fera F, Smith WG, Das S, Weinberger DR, Mattay VS. Functional changes in the activity of brain regions underlying emotion processing in the elderly. Psychiatry Res. 2005;139:9–18. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2005.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai JL, Levenson RW, Carstensen LL. Autonomic, subjective, and expressive responses to emotional films in older and younger Chinese Americans and European Americans. Psychol Aging. 2000;15:684–693. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.15.4.684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walhovd KB, Fjell AM, Reinvang I, Lundervold A, Dale AM, Eilertsen DE, Quinn BT, Salat D, Makris N, Fischl B. Effects of age on volumes of cortex, white matter and subcortical structures. Neurobiol Aging. 2005;26:1261–1270. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale - Revised. Psychological Corporation; New York: 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Wedig MM, Rauch SL, Albert MS, Wright CI. Differential amygdala habituation to neutral faces in young and elderly adults. Neurosci Lett. 2005;385:114–119. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whalen PJ, Rauch SL, Etcoff NL, McInerney SC, Lee MB, Jenike MA. Masked presentations of emotional facial expressions modulate amygdala activity without explicit knowledge. J Neurosci. 1998;18:411–418. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-01-00411.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright CI, Fischer H, Whalen PJ, McInerney SC, Shin LM, Rauch SL. Differential prefrontal cortex and amygdala habituation to repeatedly presented emotional stimuli. Neuroreport. 2001;12:379–383. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200102120-00039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yesavage J, Brink T, Rose T. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: A preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res. 1983;17:37–49. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(82)90033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1. Regions-of-interest (ROIs). Coronal (top), sagittal (middle), and axial (bottom) views of the amygdala (A) and ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (B) ROIs on group-averaged anatomical scans.

Supplementary Figure 2. Activity from whole brain within-subjects analyses. A: Negative versus baseline. B: Neutral versus baseline. C: Positive versus baseline. D: Average of all valence categories versus baseline (i.e. [negative + neutral + positive] − baseline) averaged across both groups. The anterior area of activity at +/-40, 4, 24 (the ventrolateral prefrontal cortex) was quantified using a region-of-interest analysis.

Supplementary Figure 3. Data from EVER versus NEVER exploratory analysis. A: Amygdala % signal change did not differ between women that had ever used hormone therapy (EVER) and women that had never used hormone therapy (NEVER). B: Amygdala % signal change was higher for early neutral scenes than for late neutral scenes in EVER women (p = 0.02)*. First bar is early scenes; second bar is late scenes. C: Ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (VLPFC) % signal change did not differ between EVER and NEVER women. Inset: VLPFC signal change was higher for negative than for neutral or positive scenes (ps < 0.03)**. Neutral and positive scenes did not differ from each other. D: Valence ratings did not differ between EVER and NEVER women. Women rated negative scenes lower than neutral, which were lower than positive (ps < 0.003)***. E: NEVER women rated neutral and positive scenes as more arousing than did EVER women (ps< 0.04)+. Both groups of women rated negative scenes as more arousing than neutral or positive (ps < 0.003)++. Ratings for neutral and positive scenes did not differ. F: (left) Percent correct recognition did not differ between EVER and NEVER women. (top right) Women correctly recognized negative scenes better than positive scenes (p = 0.05)+++. Negative did not differ from neutral after Bonferroni correction (p = 0.10); recognition for neutral and positive scenes did not differ. (bottom right) Women recognized more early neutral than late neutral scenes (p = 0.05)‡. First bar is early scenes; second bar is late scenes.