Abstract

Objective

To examine whether early child care exposure influences the risk of developing asthma.

Study design

Longitudinal data from 939 children and their families from the National Institute of Child Health and Development (NICHD) Study of Early Child Care and Youth Development (SECCYD) were analyzed. Exposure to other children in the primary child care setting as an infant (before 15 months) and as a toddler (16–36 months) were assessed as risk factors for persistent or late-onset asthma by age 15 via logistic regression.

Results

The number of children in the child-care environment when the child was a toddler was significantly associated with odds of asthma, even after adjusting for respiratory illnesses and other risk factors (p<.05). The fewer the children exposed to as toddlers, the higher the probability of persistent or late-onset asthma by age 15.

Conclusions

This study supports the theory of a protective effect of exposure to other children at an early age, especially as a toddler, on the risk of asthma. This effect appears to be independent of the number of reported respiratory tract illnesses, suggesting that other protective mechanisms related to the number of children in the child care environment may be involved.

Asthma is the most prevalent of chronic childhood disorders, affecting about twelve percent of children (or more than nine million) in the United States.1 The prevalence of childhood asthma has increased in the latter half of the 20th century with no clear explanation.2 One hypothesis for the increasing rate of asthma is the decreased rate of infections in early childhood.3 The discoveries of the inverse association between the number of childhood infections and the development of atopy2 support this theory.

It has also been hypothesized that exposure to fewer children during early childhood has led to increasing rates of atopy.4 The number of siblings has been found to be inversely associated with risk of various allergic disorders.4–6 Day care attendance in early childhood has been observed to be inversely associated with allergies7, wheezing, and asthma.2,8 Many have postulated that since day care attendance leads to increased rates of respiratory tract infections9,10, these illnesses are partially responsible for its protective effect.11

Three general phenotypes of asthma/wheezing have previously been proposed and are now widely recognized: 1) “transient early wheezing”, associated with lower respiratory tract infections during the first three years of life, 2) children with “late-onset wheezing” beginning after 3 years of age, and 3) children with “persistent wheezing” starting before age three and continuing throughout childhood.12 Exposure to more children may increase the risk for preschool children of infection-related wheezing, but it may help to reduce the risk of developing allergy-related asthma later in childhood.2 Day care attendance was shown to be a risk factor for wheezing and asthma in children less than 5 years old,9,10 but was found to be protective of asthma in older children.7,11

The objective of our study was to utilize an existing longitudinal dataset from a large U.S. child care study to examine the impact of the exposure to the number of children during early childhood on the risk of developing persistent or late-onset asthma. The prospective nature of this study and its wealth of information about child care characteristics provided a framework for a more detailed evaluation of this relationship.

Methods

The National Institute of Child Health and Development (NICHD) Study of Early Child Care and Youth Development (SECCYD) followed children from 10 U.S. sites from birth through age 1513 Families were recruited at hospital visits following the birth of the child in 1991. Of the 8,986 mothers who gave birth during the sampling period, 5,416 agreed to participate and were eligible as previously described.14 Of those eligible, 3,015 were randomly selected after two weeks, using conditions to ensure representation of single mothers, mothers with less than a high-school degree, and non-Caucasian mothers. Families were excluded if the infant had been in the hospital more than 7 days, if the family expected to move within three years, or if the family could not be reached after three contact attempts. Of the remaining 1,526 still eligible, 1,364 families enrolled in the study.13 By Phase IV of the study (2005–2008; age 14 and 15), 1,056 families of the original 1,364 (77%) were still enrolled. The following questions were asked of the mother at six different time points: (1) 36 months: “Did child ever have asthma?”; (2) 54 months: “Has child had asthma since last interview (at 36 months)?; (3) Grade 1 (6 years): “In the past 12 months, did child have asthma?”; (4) Grades 3 and 5 (8 and 10 years): “Have you ever been told by a teacher, school official, doctor, nurse, or other health professional that your child has asthma?”; and (5) 15 years: “Have you ever been told by a doctor, nurse, or other health professional that your child has asthma?”

Given that the asthma information was reported by the parent and did not involve the diagnosis of asthma by a physician, we chose a more conservative route in classifying a child’s asthma status. If a mother responded “yes” to any of the questions, her child was classified as having asthma only if an answer of “yes” was also reported for at least one of the subsequent questions about asthma. If only “no” responses followed a “yes”, that child was not given an asthma classification (treated as missing). The only exception to this rule is for those answering “yes” at 15 years, as no data were available after this age. This classification scheme may eliminate some who have asthma, but is less likely to misclassify children who may not have asthma. Responses to these questions allowed us to define asthma/wheezing into two of three previously described categories: “persistent asthma” and “late onset-asthma” (Table I).12 The third previously described category, “transient wheezing”, defines wheezing episodes that are only experienced by children during the first 3 years of life. The parent, however, was asked about the diagnosis of “asthma” at 36 months, and not wheezing per se. As a result, we focused on the development of persistent or late-onset asthma as the primary outcome measures in this study.

Table 1.

Asthma Classification and Rates*

| Answers to Asthma-Related Question at: |

Asthma classification |

Frequency (%) (n = 939) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 36 mos | 54 mos | Grade 1 | Grade 3 | Grade 5 | 15 yrs | ||

| Yes | No | No | No/Yes | No/Yes | No/Yes | Transient** | 27 (2.9%) |

| Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Persistent | 27 (2.9%) |

| No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Late-onset | 31 (3.4%) |

| No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Late-onset | 21 (2.3%) |

| No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Late-onset | 31 (3.4%) |

| No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Late-onset | 27 (3.0%) |

| No | No | No | No | No | Yes | Late-onset | 38 (4.2%) |

Only subsequent “No” responses after a “Yes” response disqualified a child from being classified as having symptoms consistent with asthma. If missing responses followed a “Yes’, that child was classified as having asthma.

Given the nature of the questions, transient wheezers were excluded from further analysis.

Information was obtained from the mother via face-to-face interviews when the child was 1,6,15,24, and 36 months of age. Specific questions about child care were asked at 6, 15, 24, and 36 months of age. Three types of care were of interest: center care, home-based, or parent care. Due to the fluidity of care experience over these first three years, and given the hypotheses involving child care experience and asthma risk, we focused on the number of children in the child’s primary care arrangement at each of the four time points. When the child was cared for by a parent at any point, in many cases the number of other children was missing. In these instances, we used the number of other children at home as the number of other children in the child’s care environment when this information was available. The mean number of other children was then calculated for the 6 and 15 month time points to produce a composite number of other children in the child’s care environment as an infant. Similarly, the mean number of other children in the toddler’s child care environment was calculated from the 24 and 36 month interviews. Mean hours in care were computed in a similar fashion for the infant and toddler periods as defined above. Again, these data were often missing when the child was cared for by the parent. To maximize our statistical power, we imputed 40 hours as the time cared for by the parent for those time points when these data were missing in order to resemble the amount of care received by a typical child in other care environments when one or both parents worked.

Given what is known about asthma and its risk factors, and given the observational nature of this study, other factors were examined, including the child’s sex, race/ethnicity, years of maternal education, maternal age at birth, whether or not the child was breastfed, the mean income-to-needs ratio of the household, and the mean number of other children at home over the first three years of life. Whether or not the mother smoked through the entire pregnancy, whether the child was preterm (< 37 weeks gestational age) or had eczema or any other skin allergy by 36 months (as reported by the mother) was also of interest. Additionally, the total number of respiratory infections as an infant (up through 15 months) and as a toddler (16–36 months) were tabulated from three-month phone interviews with the mother. Cleanliness of the home was measured using the yes/no response to the item “House is reasonably clean and minimally cluttered” from the 36-month Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment (HOME) Inventory, administered during a home-visit when the child was three years of age.15 To capture whether or not the family lived in an urban area, the mean percent of census block group persons living in an urban area over the first three years was calculated for each child. When the child was 15 years old, information regarding maternal health history (including asthma) was obtained. Asthma history was also collected for their “spouses”, but it is not clear that the spouses were the biological fathers of the children in this data set. Similarly, questions about the current and past smoking status of household members did not include accurate information about passive smoke exposure at home when the child was younger. Thorough and valid information on cleanliness of the child care environment or pets at home were not available in the data set.

Statistical Methods

All analyses were performed utilizing SAS® Version 9.1; statistical significance was defined as a p-value < 0.05. Distributions of the factors listed above, including type and timing of care, were compared between asthma types (no asthma vs. persistent asthma vs. late-onset asthma). Chi-square tests were used to compare rates of persistent asthma and late-onset asthma separately; when categorical factors were ordinal (e.g. income-to-needs ratio), the Cochran-Armitage test was used to test for trends. For the purposes of this univariate examination, four basic categories of child care were used: parent-only care during the first three years, center-care beginning as an infant (between 6 and 15 months), center-care beginning as a toddler (between 16 and 36 months), and some mixture of other care arrangements. The mean number of other children in the care environment when the child was both an infant and a toddler were examined further. To do this, both primary exposure variables were used to model the odds of either persistent or late-onset asthma via logistic regression. Odds of these two types of asthma were allowed to vary with both exposure variables quadratically, and the interaction between infant and toddler exposure was assessed. All of the above other factors were included in this model to adjust for any possible confounding effects. The interaction and quadratic terms of the exposure to children variables were removed individually from the model if not close to statistically significant (p > 0.10). As a supplementary analysis, we used the covariates in the final logistic model to model time to late-onset asthma only via a piecewise exponential model.

Results

Of the 1,364 families, the asthma status of 939 children could be determined based on the criteria established for this study. Among these children, 3% had persistent asthma, and 16% developed late-onset asthma by age 15 (Table I). Males had a higher rate of late-onset asthma by Grade 5, although males and females were roughly equivalent with respect to rate of late-onset asthma by age 15 (Table II). This was primarily due to the relatively large number of females who were reported to have developed asthma at an older age (i.e. between Grade 5 and 15 years of age). Those from lower-income households had higher rates of persistent asthma. Children living in a “clean” household were less likely to have late-onset asthma. Those living in more urban locales or whose mother reported having asthma had higher rates of late-onset asthma. Those with eczema or any other type of skin allergy by 3 years of age were more likely to have either type of asthma.

Table 2.

Subject Characteristics and Asthma Type

| % with Late-Onset Asthma* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency (% of Overall) |

% with Persistent Asthma* |

By Grade 5 |

By Age 15 |

|

| Total Sample | 912 | 3.0% | 12.2% | 16.2% |

| Child Sex | ||||

| Male | 456 (50.0%) | 4.0% | 14.3% † | 17.3% |

| Female | 456 (50.0%) | 2.0% | 9.9% | 15.1% |

| Child Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| White | 715 (78.4%) | 3.1% | 11.2% | 15.9% |

| African-American | 100 (11.0%) | 3.0% | 15.0% | 17.0% |

| Hispanic | 51 (5.6%) | 2.0% | 9.8% | 13.7% |

| Other | 46 (5.0%) | 2.2% | 21.7% | 21.7% |

| Maternal Education | ||||

| < 12 Years | 67 (7.4%) | 6.0% | 14.9% | 19.4% |

| 12–15 Years | 479 (52.5%) | 2.5% | 12.3% | 16.1% |

| > 15 Years | 366 (40.1%) | 3.0% | 11.2% | 15.9% |

| Maternal Prenatal Smoking | ||||

| Did not smoke or stopped before pregnancy |

726 (82.5%) | 2.8% | 11.4% | 15.6% |

| Smoked but stopped during Pregnancy |

70 (8.0%) | 4.3% | 8.6% | 12.9% |

| Smoked beyond birth | 84 (9.6%) | 2.4% | 15.4% | 21.4% |

| Family Income-to-Needs Ratio (36 month average) |

||||

| < 1 (Poverty) | 84 (9.2%) | 6.0% ‡ | 17.9% | 20.2% |

| 1.0 – 2.0 (“Working Poor”) | 186 (20.4%) | 4.8% | 11.8% | 16.1% |

| 2.0 – 5.0 (Low to middle class) |

447 (49.1%) | 2.5% | 10.3% | 14.5% |

| > 5.0 (Relatively affluent) | 194 (21.3%) | 1.0% | 13.9% | 18.6% |

| Location (Average % of Block Group Persons Living in Urban Area over 0–36 months) |

||||

| 76%–100% | 687 (77.2%) | 2.6% | 12.8% ‡ | 16.7% |

| 26%-75% | 108 (12.1%) | 2.8% | 11.1% | 14.8% |

| 0%-25% | 95 (10.7%) | 3.2% | 4.2% | 11.6% |

| Gestational Age | ||||

| < 37 weeks | 38 (4.2%) | 7.9% | 15.8% | 15.8% |

| 37 weeks or greater | 861 (95.8%) | 2.8% | 12.1% | 16.5% |

| Breastfed | ||||

| No | 213 (24.0%) | 3.3% | 14.6% | 18.3% |

| Yes | 673 (76.0%) | 2.8% | 11.1% | 15.6% |

| Eczema or other Skin Allergy (by 36 months) |

||||

| No | 745 (82.5%) | 1.7% † | 10.1% † | 13.4% † |

| Yes | 158 (17.5%) | 8.9% | 16.5% | 24.7% |

| Maternal History of Asthma | ||||

| No | 761 (89.5%) | 2.1% | 9.1% † | 12.9% † |

| Yes | 89 (10.5%) | 4.5% | 21.4% | 30.3% |

| 36 month H.O.M.E. Physical Environment Question: “House is reasonably clean and minimally cluttered” |

||||

| No | 89 (9.8%) | 3.4% | 24.7% † | 29.2% † |

| Yes | 823 (90.2%) | 2.9% | 10.7% | 14.8% |

| Child Care during first 36 months | ||||

| Parent Only | 165 (20.3%) | 4.2% | 13.9% | 18.8% |

| Center: | ||||

| Starting before 15 months | 68 (8.3%) | 2.9% | 11.8% | 16.2% |

| Starting between 16 and 35 months |

178 (21.8%) | 1.7% | 10.1% | 14.6% |

| Other and Mixed Arrangements |

404 (49.6%) | 2.7% | 11.1% | 15.6% |

Row-wise percentage

Significant difference between the groups (chi-square p < 0.05)

Significant trend between the ordinal categories (Cochran-Armitage trend test p < 0.05)

Predominant child care arrangements over the first three years of age were characterized and compared with respect to asthma prevalence (Table II). Approximately 20% of the children were exclusively cared for at home by the parent(s). About the same proportion began child care in a center as a toddler (between 16 and 36 months); less than 10 percent began center-based care as an infant (prior to 15 months). The other half of the children studied were in other arrangements that were not easily classified, either due to movement from one type to another over the three years or being cared for in other environments (e.g., home-based care by others). Rates of both asthma phenotypes (persistent and late-onset) were similar among the two center groups, with a slightly lower rate of persistent asthma among those who started center-based care as a toddler. Those who did not fall into either the parent-care or center-care categorizations had rates of both asthma types between, but not significantly different from either of the two groups. These four child-care groups were then compared with respect to child and family characteristics during the first three years (Table III; available at www.jpeds.com). The children in center-care arrangements tended to come from higher socio-economic backgrounds. They experienced more frequent symptoms of respiratory tract infections and were exposed to more children in the primary care settings.

Table 3.

Child and Family Characteristics by Child Care Classification*

| Parent Only | Center before | Center between | Other or | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 months | 16 and 36 months | Mixed | ||

| (n = 165) | (n = 68) | (n = 178) | (n = 404) | |

| Categorical Variables | ||||

| Male | 52.1% | 45.6% | 50.0% | 48.8% |

| Child Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| White | 79.4% | 89.7% | 76.4% | 77.7% |

| African-American | 9.1% | 7.4% | 9.6% | 12.6% |

| Hispanic | 4.2% | 1.5% | 6.1% | 6.7% |

| Other | 7.3% | 1.5% | 7.9% | 3.0% |

| Maternal Prenatal Smoking | ||||

| Did not smoke or stopped before pregnancy |

81.0% | 86.8% | 86.4% | 81.8% |

| Smoked but stopped during pregnancy |

7.4% | 5.9% | 6.8% | 8.6% |

| Smoked beyond birth | 11.7% | 7.4% | 6.8% | 9.6% |

| Preterm (< 37 weeks) | 4.9% | 1.5% | 3.5% | 4.3% |

| Breastfed | 72.9% | 79.4% | 77.0% | 77.3% |

| Eczema or other Skin Allergy (by 36 months) |

17.7% | 17.7% | 24.3% | 16.7% |

| 36 month H.O.M.E.: “House is reasonably clean and minimally cluttered” |

89.7% | 95.6% | 90.5% | 91.6% |

| Maternal History of Asthma | 9.7% | 14.9% | 9.3% | 10.9% |

| Continuous Variables | ||||

| Years of Maternal Education | 13.7 ± 2.3 | 15.1 ± 2.2 | 15.1 ± 2.5 | 14.5 ± 2.4 |

| Mean Income-to-Needs Ratio (0–36 months) |

2.5 ± 1.7 | 4.4 ± 3.1 | 4.3 ± 3.0 | 3.7 ± 2.7 |

| Mean Number of Other Children in Household (0 – 36 months) |

1.4 ± 1.2 | 0.6 ± 0.7 | 0.9 ± 0.9 | 0.9 ± 0.9 |

| Mean % of Block Group Persons Living in Urban Area (0–36 months) |

81.9 ± 32.1 | 85.9 ± 30.3 | 87.7 ± 27.1 | 80.4 ± 35.1 |

| Number of Respiratory Infections (0 – 15 months) |

3.2 ± 1.2 | 3.8 ± 1.1 | 3.4 ± 1.2 | 3.3 ± 1.2 |

| Number of Respiratory Infections (16 – 36 months) |

4.3 ± 1.5 | 5.1 ± 1.5 | 4.9 ± 1.6 | 4.4 ± 1.6 |

| Mean number of other children in primary care setting (6 – 15 months)** |

1.4 ± 1.3 | 6.9 ± 3.3 | 1.6 ± 1.8 | 1.7 ± 1.6 |

| Mean number of other children in primary care setting (16 – 36 months)** |

1.7 ± 1.4 | 10.8 ± 3.9 | 8.1 ± 3.5 | 2.3 ± 2.0 |

Categorical variables are reported in terms of column-wise percentages. Continuous variables are reported as means + standard deviations for the group defined by the column.

In the case of parent care, if information on other children in primary care setting was missing, the number of other children in the home was used for that observation (6, 15, 24, or 36 months).

Logistic regression was used to model the odds for persistent or late-onset asthma as a function of other common risk factors for asthma, most notably exposure to other children during infancy or as a toddler (Table IV). Both the interaction between infant and toddler exposure to children as well as the quadratic term of infant exposure did not reach significance (p > 0.10) and were removed individually from the model. Odds ratios (and 95% confidence intervals) are presented in Table IV for all of the remaining model covariates except for the number of other children in the toddler-care setting, which notably had a significant quadratic relationship with the odds of developing asthma. Of the factors unrelated to child care, maternal history of asthma, having eczema or a skin allergy, and the number of respiratory infections as a toddler remained significantly associated with an increased odds of developing persistent or late-onset asthma. Those with eczema or a skin allergy by 36 months, or whose mother reported having asthma, were about three times more likely to have asthma (p < 0.001). For every additional reported respiratory infection reported as a toddler, the odds of asthma for the child increased 1.2 times (p < 0.01). Interestingly, maternal age was also found to be a significant predictor of developing asthma (odds ratio = 0.94, p = 0.03). For each additional year older of the mother at the child’s birth, the odds of asthma decreased by a factor of 0.94. In other words, a child of a 25-year-old mother is about 1.4 times more likely to have asthma than a child of a 30-year-old mother, after adjusting for all of the factors listed in Table IV.

Table 4.

Logistic Regression Results: Full Model of Odds of Asthma

| Model Covariate | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Males (vs. Females) | 1.14 | (0.76, 1.71) | 0.538 |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| Black (non-Hispanic) vs. Caucasian | 0.98 | (0.47, 2.08) | 0.318 |

| Hispanic vs. Caucasian | 0.28 | (0.08, 1.04) | 0.071 |

| Other vs. Caucasian | 0.90 | (0.35, 2.35) | 0.538 |

| Maternal History of Asthma | 2.88 | (1.66, 5.00) | < 0.001 |

| Mean number of other children (0–36 mos) in the home |

1.11 | (0.89, 1.39) | 0.354 |

| 36 month H.O.M.E.: ”Reasonably clean and minimally cluttered house” vs. not |

0.74 | (0.35, 1.58) | 0.443 |

| Number of respiratory infections (0–15 months) | 1.09 | (0.90, 1.32) | 0.372 |

| Number of respiratory infections (16–36 mos) | 1.24 | (1.08, 1.44) | 0.003 |

| Years of Maternal Education | 1.01 | (0.90, 1.13) | 0.866 |

| Mean Income-to-Needs Ratio (0–36 mos) | 1.07 | (0.98, 1.17) | 0.139 |

| Preterm (< 37 weeks) vs. not | 1.36 | (0.48, 3.87) | 0.564 |

| Eczema or other skin allergy (by 36 mos) | 3.09 | (1.94, 4.91) | < 0.001 |

| Maternal age | 0.94 | (0.90, 0.99) | 0.027 |

| Mom smoked through pregnancy vs. not | 0.92 | (0.44, 1.92) | 0.825 |

| Mean % of Block Group Persons Living in Urban Area over 0–36 months |

1.00 | (1.00, 1.01) | 0.314 |

| Breastfed vs. not | 1.12 | (0.64, 1.95) | 0.691 |

| Mean number of hours in primary infant care setting per week (6 – 15 mos) |

0.99 | (0.97, 1.01) | 0.243 |

| Mean number of hours in primary toddler care setting per week (15 – 36 mos) |

1.00 | (0.98, 1.02) | 0.959 |

| Mean number of other children in primary infant care setting (6– 15 mos) |

0.96 | (0.87, 1.06) | 0.375 |

| Mean number of other children in primary toddler care setting (16– 36 mos) |

* | 0.048 | |

| (Mean number of other children in toddler care)2 | * | 0.036 | |

Due to the quadratic nature of the relationship, a single odds ratio is not feasible. The odds ratio “function”, comparing a certain number of other children in toddler care to zero children in toddler care, is = e(−0.131*(other children) + 0.008*(other children)2). For a better representation of the quadratic relationship between other children in care and probability of asthma, see the Figure.

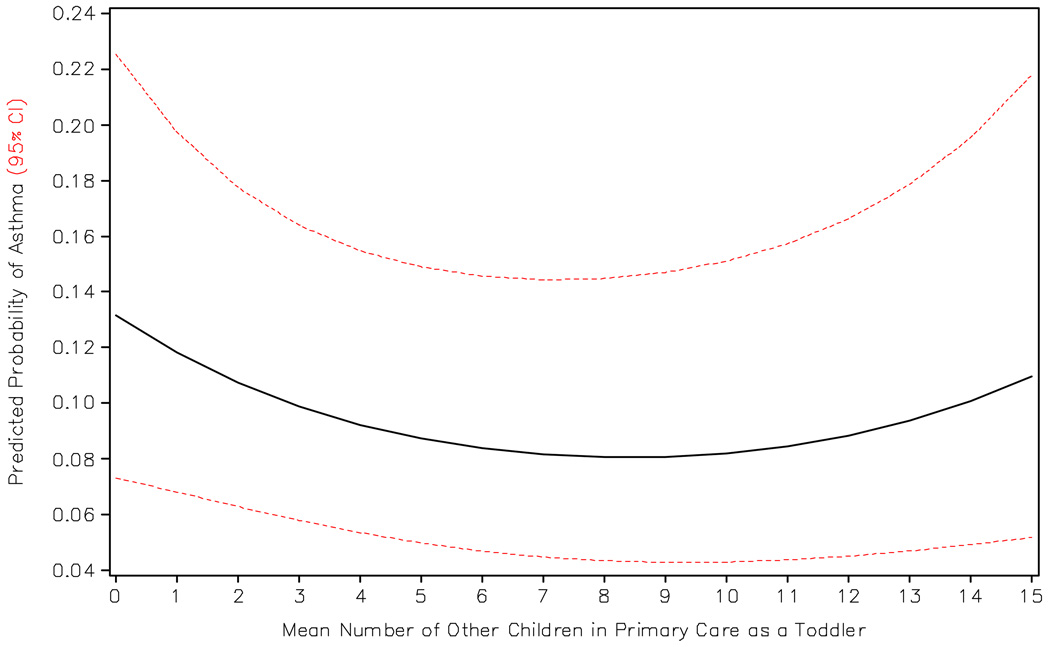

Exposure to more children during infancy was not significantly associated with reduced odds of asthma in this study (p = 0.38). However, a significant predictor of asthma was the number of children in the child-care environment when the child was a toddler. As the number of children in this age group (16 to 36 months of age) increased, the odds of asthma (persistent or late-onset) varied in a quadratic fashion (p = 0.036; Figure). The Figure shows that children exposed to few or no other children as toddlers had a higher risk of persistent or late-onset asthma by 15 years of age. This probability continues to decrease as the number of children in the toddler child-care setting increased, reaching a minimum at around 9 children. The probability then leveled off, and in fact increased as the number of other children in the child-care center grew larger (10 or more children). This model and the resulting figure indicate that exposure to other children during the toddler years may protect against development of asthma, but that there appears to be a threshold for this protective effect.

Figure 1.

Model-Predicted Probability of Asthma (Persistent or Late-Onset) by Number of Other Children in the Child-Care Environment as a Toddler*

* Predicted probability as a function of mean number of other children in the child care setting as a toddler, using the final logistic model (Table IV), adjusting for all of the listed covariates. This figure presents specific probabilities for a Caucasian male whose mother did not report having asthma in a “clean” household who had 4 and 5 respiratory infections as an infant and toddler, respectively, who was not preterm, does not have eczema, and was breastfed, who was in primary care 32 hours per week in the first three years, who was around 2 other children in the primary care setting as an infant, with a mother with 14 years of education and is 29 years old and did not smoke during pregnancy, from an urban household with an income-to-needs ratio of 3 (all values are medians from the dataset). This overall relationship would remain no matter what values were chosen for the other covariates.

As an additional analysis, the same covariates in the final model (Table IV) were included in a piecewise exponential model of time to late-onset asthma, excluding those defined as having persistent asthma. The very same factors found to be significant in the logistic model were found to significantly impact the hazard of late-onset asthma (i.e. toddler exposure to children in the primary care setting again had a significant quadratic relationship; p < 0.05; results not shown).

Discussion

The results from this study support the theory of a protective effect of exposure to other children at an early age with respect to asthma risk. However, our results indicate this protective effect is more strongly associated with child-care experiences as a toddler (ages 16 to 36 months).Moreover, this effect may be independent of the number of respiratory tract illnesses a child experiences during this period, suggesting that other mechanisms may be involved.

Given the fluidity of child care experience over the first three years, we chose to focus on the number of other children in the child care environment. The protective effect of exposure to other children as a toddler as judged by this study differs from previous investigations which have focused on child care experiences during infancy.2,11 These studies found protective effects at an early age (6 months to 1 year of age). It is possible that children in child care environments with more children at an earlier age are likely to stay in those environments when they become toddlers. If true, the effect seen at an earlier age may be confounded by the real protection afforded by exposure to more children at an older (toddler) age. Our study provides some evidence for this possibility. In this regard, when the model presented in Table IV is fit with only infant child-care variables, results similar to the previous studies are observed, albeit without statistical significance. Additionally, our results are consistent with at least one previous study that found that the protective effect of large household size on asthma risk may not occur in the first year of life, but rather later.16

An advantage in our evaluation of the NICHD SECCYD data set is the fact that the exposures encountered by the children in this survey were documented prior to defining asthma status. Additionally, we focused on risk factors for the development of asthma reported by the parent(s) after 36 months of age, because most children who experience early childhood wheezing do so transiently. As a result, they are less often given the diagnosis of asthma which was reported in only 3% of the children in this study prior to 36 months (Table I). We also combined the persistent and late-onset asthma groups, because those who fit into the persistent group did not include enough subjects to evaluate separately. In this investigation, it is possible that the parents of children with persistent asthma, which includes wheezing during infancy, may have been inclined to keep their child at home when they were toddlers. The data do suggest this as a possibility (i.e. 22% of children with persistent asthma were enrolled in center care by three years of age, compared with 28% and 31%, for children with late-onset or no asthma, respectively). However, when examining the logistic model of odds of late-onset asthma only, which eliminates this possible bias, exposure to other children as a toddler remained significantly associated with asthma risk in a similar fashion.

A limitation associated with this study includes the observational nature of the questions to which the parents were asked to respond. For example, although the definitions used to distinguish wheezing or asthmatic phenotypes in this investigation are in keeping with those used in previous studies, our definitions of persistent and late-onset asthma were influenced by the timing when parents were asked about the asthmatic status of their child. The nature of the survey questions asked to the parents regarding asthma makes it difficult to definitively classify individuals into one of the three phenotypes. We believe we implemented a conservative strategy in classifying individuals, ignoring any positive responses to asthma questions if negative responses followed. Additionally, our definition of persistent asthmatics may not be precise, as some individuals may have said “no” at 36 months given the term “asthma” is typically avoided prior to this point. In this case, we may have classified some individuals as late-onset asthmatics when they truly had persistent asthma However, such misclassification does not impact the primary analysis nor the resulting conclusions, as we grouped these two phenotypes as our outcome of interest. One must also discuss the validity of parent-reported respiratory infections in particular. It is possible that parents of children who have asthma exacerbations related to infection are more likely to remember these infections, which would at least partially explain our observed positive relationship between toddler respiratory infections and asthma odds. But, such bias should not alter the observed primary relationship between asthma and the child care environment.

It has previously been shown that increased exposure to other children, presumably in day care settings, leads to more respiratory infections.17,18 Previous research using this same dataset found that children in non-maternal care had more respiratory illnesses in the first two years of life.19 These results are consistent with the hypothesis that an increase in respiratory tract infections, predominantly in the upper airway, may influence the immune system and protect against the development of asthma, whereas infections in the lower airway can confer an increased risk for persistent wheezing as children grow older.20 Our model adjusts for the number of respiratory tract illnesses reported by the parent(s) and suggests that other environmental factors may also be associated with exposure to other children at day care that could influence asthma risk. Tests to document the presence of viral, or other respiratory tract, pathogens were understandably not done as part of this evaluation. Thus, flares of allergic respiratory tract symptoms that become more prominent during the toddler years, may also account for a proportion of these reported illnesses. Because allergen sensitization and higher levels of allergen exposure are associated with an increased risk for developing asthma, it would be important to know in designing future studies whether allergen exposures (as well as exposure to other airway irritants) are higher in homes than in center care environments, especially in centers that care for a larger number of children.

The validity of these study results is strengthened by significant associations observed between asthma and other risk factors which have previously been reported. For example, having a mother with asthma has been found to be a risk factor for developing asthma,8 as well as having eczema or other skin allergies.22 Additionally, maternal age has also been shown to be inversely related to the risk for developing asthma.23 Although we discovered that Hispanic children in this survey had a lower risk for developing asthma, the “Hispanic” ethnic group in the United States is quite diverse, and includes Puerto Rican, Cuban, and Mexican individuals. In keeping with our results, however, it has previously been reported that Mexican-American children have lower odds of developing asthma.24 Unfortunately, more specific ethnicity information was not collected in this study, so we are unable to explore our results further to demonstrate consistency with previous findings.

Unlike previous studies8, male sex was not found to be a risk factor in the final model which grouped children with persistent asthma with those who developed asthma as late as 15 years of age. Individuals who tend to develop asthma later in adolescence are more likely to be female,25 which would offset the elevated risk of being male for developing asthma earlier in childhood. Our univariate results regarding sex and asthma timing (Table II) are consistent with previous research, given further credence to our definitions of asthma using parent-reported information over time. Taken together, the extent of agreement between our observations from the NICHD SECCYD and previous studies heightens interest in future studies to decipher environmental factors at home versus center care during the toddlers years which may influence the risk for asthma that develops or persists during the school age years.

In conclusion, our study adds new insights to previous observations involving risk factors for asthma associated with child care during the preschool years. The results are consistent with previous work, suggesting that the more children an individual is exposed to at an early age, the less likely that child will develop persistent or late-onset asthma. Our findings indicate that the timing of this exposure does matter, and that the exposure to other children during the toddler-years is more protective. Moreover, the possibility that more frequent respiratory tract illnesses may not be the only factor in this observed relationship sets this study apart from others.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by NICHD grant R03-HD055298.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors declare no potential, perceived, or real conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.National Center for Health Statistics. Asthma prevalence, health care use and mortality, 2002. 2002 http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/pubs/pubd/hestats/asthma/asthma.htm. In: ;

- 2.Ball TM, Castro-Rodriguez JA, Griffith KA, Holberg CJ, Martinez FD, Wright AL. Siblings, day-care attendance, and the risk of asthma and wheezing during childhood. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(8):538–543. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200008243430803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martinez FD. Maturation of immune responses at the beginning of asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999;103(3 Pt 1):355–361. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(99)70456-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Strachan DP. Hay fever, hygiene, and household size. BMJ. 1989;299(6710):1259–1260. doi: 10.1136/bmj.299.6710.1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ponsonby AL, Couper D, Dwyer T, Carmichael A. Cross sectional study of the relation between sibling number and asthma, hay fever, and eczema. Arch Dis Child. 1998;79(4):328–333. doi: 10.1136/adc.79.4.328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Strachan DP, Harkins LS, Johnston ID, Anderson HR. Childhood antecedents of allergic sensitization in young british adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1997;99(1 Pt 1):6–12. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(97)70294-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kramer U, Heinrich J, Wjst M, Wichmann HE. Age of entry to day nursery and allergy in later childhood. Lancet. 1999;353(9151):450–454. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)06329-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martel M, Rey E, Malo J, et al. Determinants of the incidence of childhood asthma: A two-stage case-control study. Am J Epidemiol. 2008 doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marbury MC, Maldonado G, Waller L. Lower respiratory illness, recurrent wheezing, and day care attendance. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;155(1):156–161. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.155.1.9001305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nafstad P, Hagen JA, Oie L, Magnus P, Jaakkola JJ. Day care centers and respiratory health. Pediatrics. 1999;103(4):753–758. doi: 10.1542/peds.103.4.753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Celedon JC, Wright RJ, Litonjua AA, et al. Day care attendance in early life, maternal history of asthma, and asthma at the age of 6 years. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167(9):1239–1243. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200209-1063OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martinez FD, Wright AL, Taussig LM, Holberg CJ, Halonen M, Morgan WJ. Asthma and wheezing in the first six years of life. the group health medical associates. N Engl J Med. 1995;332(3):133–138. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199501193320301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.The national institute of child health and human development study of early child care and youth development study summary. available at http://secc.rti.org/summary.cfm. In: .

- 14.Does amount of time spent in child care predict socioemotional adjustment during the transition to kindergarten? Child Dev. 2003;74(4):976–1005. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Caldwell BM, Bradley RH. HOME Observation for Measurement of the Environment. Rev. ed. Little Rock, Ark.: University of Arkansas at Little Rock; 1984. Center for Child Development and Education; p. 135. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ponsonby AL, Couper D, Dwyer T, Carmichael A, Kemp A. Relationship between early life respiratory illness, family size over time, and the development of asthma and hay fever: A seven year follow up study. Thorax. 1999;54(8):664–669. doi: 10.1136/thx.54.8.664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Louhiala PJ, Jaakkola N, Ruotsalainen R, Jaakkola JJ. Form of day care and respiratory infections among finnish children. Am J Public Health. 1995;85(8 Pt 1):1109–1112. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.8_pt_1.1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ball TM, Holberg CJ, Aldous MB, Martinez FD, Wright AL. Influence of attendance at day care on the common cold from birth through 13 years of age. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156(2):121–126. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.2.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Early Child Care Research Network. Child care and common communicable illnesses: Results from the national institute of child health and human development study of early child care. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155(4):481–488. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.155.4.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Illi S, von Mutius E, Lau S, et al. Early childhood infectious diseases and the development of asthma up to school age: A birth cohort study. BMJ. 2001;322(7283):390–395. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7283.390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Raby BA, Celedon JC, Litonjua AA, et al. Low-normal gestational age as a predictor of asthma at 6 years of age. Pediatrics. 2004;114(3):e327–e332. doi: 10.1542/peds.2003-0838-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rusconi F, Galassi C, Corbo GM, et al. Risk factors for early, persistent, and late-onset wheezing in young children. SIDRIA collaborative group. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160(5):1617–1622. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.160.5.9811002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Laerum BN, Svanes C, Wentzel-Larsen T, et al. Young maternal age at delivery is associated with asthma in adult offspring. Respiratory Medicine. 2007;101(7):1431–1438. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2007.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hunninghake GM, Weiss ST, Celedon JC. Asthma in hispanics. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173(2):143–163. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200508-1232SO. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Withers NJ, Low L, Holgate ST, Clough JB. The natural history of respiratory symptoms in a cohort of adolescents. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;158(2):352–357. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.158.2.9705079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]