Abstract

We have previously shown that the antinociceptive effect of nitrous oxide (N2O) in the rat hot plate test is sensitive to antagonism by antisera against the endogenous opioid peptide β-endorphin. Moreover, N2O-induced antinociception is reduced by inhibition of nitric oxide (NO) production in the brain. To test the hypothesis that N2O might stimulate an NO-dependent neuronal release of β-endorphin, we conducted a ventricular-cisternal perfusion with artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) in urethane-anesthetized Sprague Dawley rats. Ten-min fractions of aCSF perfusate were collected from separate groups of room air-exposed rats, N2O-exposed rats, and L-NAME-pretreated, N2O-exposed rats; they were then analyzed for their content of NO metabolites and β-endorphin. Compared to room air control, exposure to 70% N2O increased perfusate levels of the NO metabolites nitrite and nitrate as well as β-endorphin. Pretreatment of rats with L-NG-nitro arginine methyl ester, an inhibitor of NO synthase, prevented the N2O-induced increases in nitrite, nitrate and β-endorphin. These findings demonstrate in an in vivo rat model that N2O may stimulate an NO-dependent neuronal release of β-endorphin.

Keywords: Nitrous oxide, nitric oxide, β-endorphin, ventricular-cisternal perfusion, rats

1. Introduction

N2O-induced antinociception in rats is mediated by central opioid mechanisms (Berkowitz et al., 1976, 1977), possibly involving the endogenous opioid peptide β-endorphin (Zuniga et al., 1987a, 1987b). Moreover, the important signaling molecule nitric oxide (NO) has also been implicated in the antinociceptive response to N2O (McDonald et al., 1994; Ishikawa and Quock, 2003; Li et al., 2004). Based on strong preliminary findings, we have hypothesized that exposure to N2O stimulates an NO-dependent neuronal release of β-endorphin. The aim of the present study was to demonstrate in vivo whether exposure to N2O concurrently increases the release of NO metabolites and β-endorphin into the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of ventricular-cisternally-perfused rats and determine whether these effects are sensitive to antagonism by inhibition of NO production.

2. Results

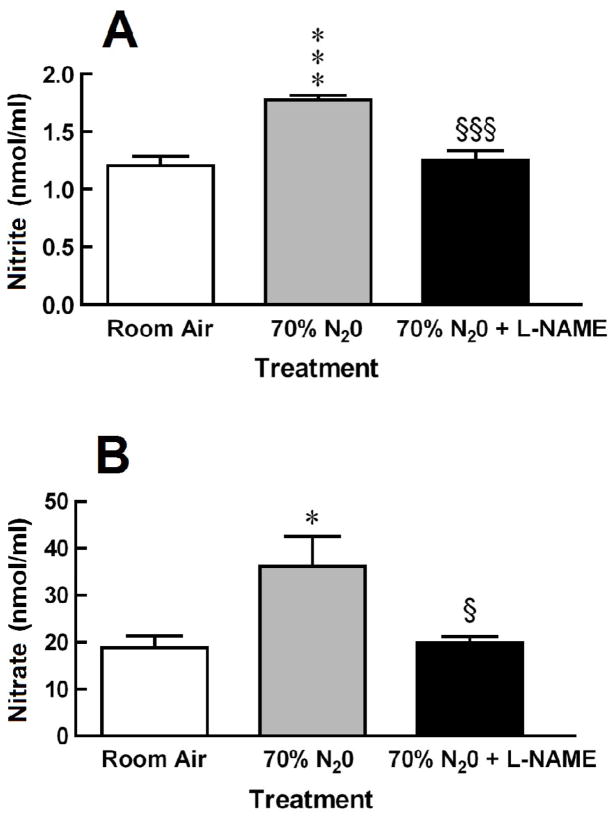

Exposure to 70% N2O did increased perfusate levels of nitrite and nitrate by 46% and 95%, respectively (Fig. 1). The N2O-induced increases in NO metabolites were abolished by pretreatment with L-NAME [nitrite: F = 20.87, P < 0.0001; and nitrate: F = 5.532, P = 0.0118].

Fig. 1.

Antagonism by L-NAME of N2O-induced increases in perfusate levels of (A) nitrite and (B) nitrate. Each bar represents the mean ± SEM of 8 rats per group. Significance of difference: *, P < 0.05, ***, P < 0.001, compared to Room Air control group; and §, P < 0.05, §§§, P < 0.001, compared to 70% N2O group (Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test).

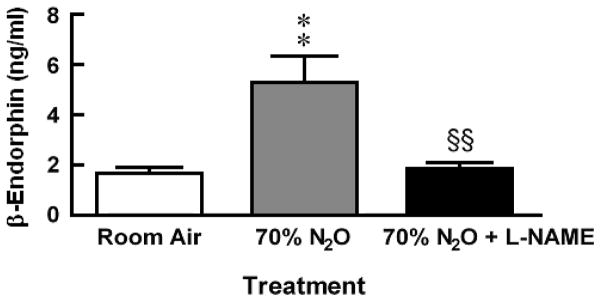

In a different group of rats, exposure to 70% N2O increased perfusate levels of β-endorphin threefold more than levels collected from room air control animals (Fig. 2). The N2O-induced increase in β-endorphin was abolished by pretreatment with L-NAME 30 min prior to N2O exposure [F = 10.09, P = 0.0006].

Fig. 2.

Antagonism by L-NAME of N2O-induced increases in perfusate levels of β-endorphin. Each bar represents the mean ± SEM of 8–11 rats per group. Significance of difference: **, P < 0.01, compared to Room Air control group, §§, P < 0.01, compared to 70% N2O group (Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test).

3. Discussion

The results of the present study demonstrate in vivo that exposure to N2O causes the neuronal release of β-endorphin and confirm the in vitro findings of Zuniga and associates (Zuniga et al., 1987b). The findings also show an increase in perfusate levels of NO metabolites concomitant with the elevation in β-endorphin in ventricular-cisternally perfused rats. The increases in β-endorphin and NO metabolites are both sensitive to antagonism by prior administration of an NOS-inhibitor. One interpretation of these findings is that N2O-induced release of β-endorphin is NO-dependent. The feasibility of this concept is strong as NO has been implicated as a modulator in the neuronal release of several different neurotransmitters (Lonart et al., 1992; Prast and Philippu, 1992; Tanioka et al., 2002; Kodama and Koyama, 2006) and endocrine hormones (Uretsky et al., 2002; Rubinek et al., 2005).

One prominent concentration of pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC) neurons in the brain is in the basal hypothalamus, most notably the arcuate nucleus (Bloom et al., 1978). A major POMC pathway projects to the periaqueductal gray (PAG) of the midbrain (Pilcher et al., 1988; Yoshida and Taniguchi, 1988), and high levels of β-endorphin are localized in the PAG (Palkovits and Eskay, 1987). Electrical stimulation of the arcuate nucleus was found to increase release of β-endorphin (Bach and Yaksh, 1995) as did exposure to stress or ethanol (Marinelli et al., 2004). This arcuate-PAG pathway appears to be important in the antinociceptive effect of some drugs. L-Tetrahydropalmatine-induced antinociception in rabbits was antagonized after lesioning of the arcuate nucleus or following intra-PAG pretreatment with naloxone (Hu and Jin, 2000). Microinjection of galanin into the arcuate nucleus of rats elicited an antinociceptive effect that was antagonized by naloxone or β-funaltrexamine microinjected into the PAG (Sun et al., 2007).

There are also suggestions that this same arcuate-PAG pathway may also be implicated in the antinociceptive effect of N2O. Zuniga and coworkers (Zuniga et al., 1978b) demonstrated that exposure to 80% N2O stimulated release of β-endorphin from basal hypothalamic cells dispersed on cytodex microcarrier beads in an in vitro superfusion model. This same research team (Zuniga et al., 1987a) also found that exposure to N2O increased the concentration of β-endorphin and the level of immunoreactive ACTH1–39 staining in the pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC) pathway — both β-endorphin and ACTH1–39 are cleavage products of POMC. It was also found that the antinociceptive response of rats to N2O was significant attenuated by kainic acid lesions of the ventral and caudal PAG (Zuniga et al., 1987c). Zuniga concluded that that N2O may have a stimulatory effect on central POMC neurons to release β-endorphin.

Zuniga’s conclusion was later indirectly supported by our findings that N2O-induced antinociception in the rat hot plate test was antagonized in dose-related manner by intracerebroventricular pretreatment with a rabbit antiserum against rat β-endorphin but not by an antiserum against methionine-enkephalin (Hara et al., 1994). Furthermore N2O-induced antinociception was also blocked by intracerebroventricular (i.c.v.) pretreatment with β-endorphin1–27 (Hodges et al., 1994) — a truncated form of β-endorphin that is a partial antagonist of β-endorphin (Takemori and Portoghese, 1993; Yanagita et al., 2008) — and also by intra-PAG microinjection with the μ opioid antagonist CTOP (D-Phe-Cys-Tyr-D-Trp-Orn-Thr-Pen-Thr-NH2) (Hawkins et al., 1989). These results implicate N2O-induced release of β-endorphin in the antinociceptive response of rats to N2O.

Earlier work from our laboratory also demonstrated that N2O-induced antinociception is sensitive to antagonism by inhibition of NO synthesis. The antinociceptive response of rats and mice was inhibited in stereoselective manner by various L-arginine analogs (McDonald et al., 1994) and other inhibitors of NOS enzyme (Ishikawa and Quock, 2003). The antinociceptive effect in mice was also antagonized by i.c.v. pretreatment with an antisense oligodeoxynucleotide directed against neuronal NOS (Li et al., 2004). We also found that the β-endorphin-stimulated release of methionine-enkephalin in the spinal cord of intrathecally-perfused rats was significantly reduced by inclusion of an NOS-inhibitor in the artificial cerebrospinal fluid that was infused intrathecally (Hara et al., 1995). We have suggested that NO plays a critical role in regulating the neuronal release of endogenous opioid peptides.

Microdialysis experiments are currently in progress to localize the brain sites from which NO metabolites and β-endorphin are released by N2O. Intracerebral microinjection of NOS-inhibitors will also circumvent potential confounds that might be associated with changes in systemic blood pressure and cerebral blood flow.

4. Experimental procedures

4.1. Animals

Male Sprague Dawley rats, 200–250 g body weight, were purchased from Simonsen Laboratories (Gilroy, CA). Rats were housed two per cage with food and water available ad libitum in the Wegner Hall Vivarium at Washington State University, which is accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC). The facility was maintained on a 12-h light/dark cycle (lights on 0700–1900) under standard conditions (22 ± 1°C room temperature, 33% humidity). Rats were kept in the holding room for at least four days following arrival in the facility.

This research was approved by the institutional animal care and use committee (IACUC) of Washington State University with post-approval review. All experiments were carried out in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 1996) as adopted and promulgated by the U.S. National Institutes of Health. All measures to minimize pain or discomfort were taken by the investigators.

4.2. Ventricular-Cisternal Perfusion

Rats were anesthetized with ketamine/xylazine (100/15 mg/kg, i.p.). Rats were implanted with a 20-G stainless steel inflow cannula in the lateral cerebral ventricle at stereotaxic coordinates 0 mm AP, 1.5 mm ML and −3.0 mm DV (Paxinos and Watson, 2006) and secured to the calvarium with stainless steel screws and dental cement.

On the following day, rats were anesthetized with 1.2 g/kg urethane and mounted in a stereotaxic headholder. The inflow cannula and its connecting 50-cm length of PE-10 polyethylene tubing were filled with artificial CSF (aCSF; 145.4 mM NaCI, 2.6 mM KCl, 0.9 mM MgCl2, 1.3 mM CaCl2 and 30 mg/l bacitracin, adjusted to pH 7.4) prior to insertion. The PE-10 tubing was connected to an infusion pump (KD Scientific Inc., Holliston, MA). The aCSF flow rate was set at 50 μl/min. To obtain outflow from the cisterna magna, a second 20-G stainless steel needle was inserted through the exposed atlanto-occipital membrane and connected to another 3-cm length of PE-50 tubing. The aCSF perfusate was collected in Eppendorf minitubes for subsequent determination of NO metabolites and β-endorphin. Each fraction consisted of perfusate collected during a 10-min period in separate groups of room air-exposed rats, N2O-exposed rats, and L-NAME-pretreated, N2O-exposed rats.

4.3. Exposure to N2O

The stereotaxic apparatus and infusion pump were placed inside an inflatable AtmosBag™ (Aldrich Chemical Co., Milwaukee, WI) with gas inlet and outlet ports. Nitrous Oxide, U.S.P. and Oxygen, U.S.P. (A-L Compressed Gases, Inc., Spokane, WA) were mixed and delivered into the bag using a dental-sedation system (Porter, Hatfield, PA) at a total flow rate of 10 L/min. Control and L-NAME-pretreated rats were exposed to N2O for 20 min; perfusate from the last 10 min only were analyzed for NO metabolite or β-endorphin content. The levels of N2O and O2 in the AtmosBag™ were monitored using a POET II® anesthetic monitoring system (Criticare, Milwaukee, WI). Exhausted gases were routed to a nearby fume hood.

4.4. Quantification of NO metabolites and β-endorphin

Levels of total NOx — defined as nitrite (NO2−) plus nitrate (NO3−) — were determined using a NO Quantitation Kit (Active Motif, Carlsbad, CA). β-Endorphin was quantified using a commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (EK-022-33, Phoenix Pharmaceutical, Belmont, CA).

4.5. Drugs

The following drug was used in this research: L-NG-nitro arginine methyl ester (L-NAME; 50 mg/kg i.p., Sigma Aldrich/Research Biochemicals Inc., Natick, MA). Drug was freshly prepared in 0.9% physiological saline solution. Systemic pretreatment drugs were administered in an injection volume of 0.1 ml/100 g body weight.

4.6. Statistical Analysis of Data

The perfusate levels of nitrite, nitrate, total NOx (nitrite plus nitrate) and β-endorphin collected from control (room air), N2O only and N2O + L-NAME treatment groups were compared using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with post-hoc Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test (Graphpad Prism, Graphpad Software, San Diego CA).

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by NIH Grant GM-77153 (R.M.Q.), State of Washington Initiative Measure No. 171 (R.M.Q.) and the American Society for Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics (ASPET) through an institutional Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowship (SURF) Program in Pharmacology and Toxicology.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bach FW, Yaksh TL. Release into ventriculo-cisternal perfusate of beta-endorphin- and Met-enkephalin-immunoreactivity: effects of electrical stimulation in the arcuate nucleus and periaqueductal gray of the rat. Brain Res. 1995;690:167–176. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00600-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkowitz BA, Finck AD, Ngai SH. Nitrous oxide analgesia: reversal by naloxone and development of tolerance. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1977;203:539–547. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkowitz BA, Ngai SH, Finck AD. Nitrous oxide ‘analgesia’: resemblance to opiate action. Science. 1976;194:967–968. doi: 10.1126/science.982058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom F, Battenberg E, Rossier J, Ling N, Guillemin R. Neurons containing beta-endorphin in rat brain exist separately from those containing enkephalin: immunocytochemical studies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1978;75:1591–1595. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.3.1591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara S, Gagnon MJ, Quock RM, Shibuya T. Effect of opioid peptide antisera on nitrous oxide antinociception in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1994;48:699–702. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(94)90335-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara S, Kuhns ER, Ellenberger EA, Mueller JL, Shibuya T, Endo T, Quock RM. Involvement of nitric oxide in intracerebroventricular β-endorphin-induced neuronal release of methionine-enkephalin. Brain Res. 1995;675:190–194. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00065-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins KN, Knapp RJ, Lui GK, Gulya K, Kazmierski W, Wan YP, Pelton JT, Hruby VJ, Yamamura HI. [3H]-[H-D-Phe-Cys-Tyr-D-Trp-Orn-Thr-Pen-Thr-NH2] ([3H]CTOP), a potent and highly selective peptide for mu opioid receptors in rat brain. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1989;248:73–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges BL, Gagnon MJ, Gillespie TR, Breneisen JR, O’Leary DF, Hara S, Quock RM. Antagonism of nitrous oxide antinociception in the rat hot plate test by site-specific μ- and ε-opioid receptor blockade. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1994;269:596–600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu JY, Jin GZ. Arcuate nucleus of hypothalamus involved in analgesic action of l-THP. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2000;21:439–444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa M, Quock RM. Role of nitric oxide synthase isoforms in nitrous oxide antinociception in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;306:484–489. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.049551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodama T, Koyama Y. Nitric oxide from the laterodorsal tegmental neurons: Its possible retrograde modulation on norepinephrine release from the axon terminal of the locus coeruleus neurons. Neuroscience. 2006;138:245–256. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.10.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Bieber AJ, Quock RM. Antagonism of nitrous oxide antinociception in mice by antisense oligodeoxynucleotide directed against neuronal nitric oxide synthase enzyme. Behav Brain Res. 2004;152:361–363. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2003.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonart G, Wang J, Johnson KM. Nitric oxide induces neurotransmitter release from hippocampal slices. Eur J Pharmacol. 1992;220:271–272. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(92)90759-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marinelli PW, Quirion R, Gianoulakis C. An in vivo profile of beta-endorphin release in the arcuate nucleus and nucleus accumbens following exposure to stress or alcohol. Neuroscience. 2004;127:777–784. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.05.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald CE, Gagnon MJ, Ellenberger EA, Hodges BL, Ream JK, Tousman SA, Quock RM. Inhibitors of nitric oxide synthesis antagonize nitrous oxide antinociception in mice and rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1994;269:601–608. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palkovits M, Eskay RL. Distribution and possible origin of β-endorphin and ACTH in discrete brainstem nuclei of rats. Neuropeptides. 1987;9:123–137. doi: 10.1016/0143-4179(87)90051-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates. 6. Academic Press; San Diego: 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilcher WH, Joseph SA, McDonald JV. Immunocytochemical localization of pro-opiomelanocortin neurons in human brain areas subserving stimulation analgesia. J Neurosurg. 1988;68:621–629. doi: 10.3171/jns.1988.68.4.0621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prast H, Philippu A. Nitric oxide releases acetylcholine in the basal forebrain. Eur J Pharmacol. 1992;216:139–140. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(92)90223-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubinek T, Rubinfeld H, Hadani M, Barkai G, Shimon I. Nitric oxide stimulates growth hormone secretion from human fetal pituitaries and cultured pituitary adenomas. Endocrine. 2005;28:209–216. doi: 10.1385/ENDO:28:2:209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun YG, Gu XL, Yu LC. The neural pathway of galanin in the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus of rats: activation of beta-endorphinergic neurons projecting to periaqueductal gray matter. J Neurosci Res. 2007;85:2400–2406. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takemori AE, Portoghese PS. The mixed antinociceptive agonist-antagonist activity of beta-endorphin1–27 in mice. Life Sci. 1993;53:1049–1052. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(93)90257-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanioka H, Nakamura K, Fujimura S, Yoshida M, Suzuki-Kusaba M, Hisa H, Satoh S. Facilitatory role of NO in neural norepinephrine release in the rat kidney. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2002;282:R1436–1442. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00697.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uretsky AD, Weiss BL, Yunker WK, Chang JP. Nitric oxide produced by a novel nitric oxide synthase isoform is necessary for gonadotropin-releasing hormone-induced growth hormone secretion via a cGMP-dependent mechanism. J Neuroendocrinol. 2003;15:667–676. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.2003.01046.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanagita K, Shiraishi J, Fujita M, Bungo T. Effects of N-terminal fragments of beta-endorphin on feeding in chicks. Neurosci Lett. 2008;442:140–142. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida M, Taniguchi Y. Projection of pro-opiomelanocortin neurons from the rat arcuate nucleus to the midbrain central gray as demonstrated by double staining with retrograde labeling and immunohistochemistry. Arch Histol Cytol. 1988;51:175–183. doi: 10.1679/aohc.51.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuniga JR, Joseph SA, Knigge KM. The effects of nitrous oxide on the central endogenous pro-opiomelanocortin system in the rat. Brain Res. 1987a;420:57–65. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)90239-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuniga JR, Joseph SA, Knigge KM. The effects of nitrous oxide on the secretory activity of pro-opiomelanocortin peptides from basal hypothalamic cells attached to cytodex beads in a superfusion in vitro system. Brain Res. 1987b;420:66–72. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)90240-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuniga J, Joseph S, Knigge K. Nitrous oxide analgesia: partial antagonism by naloxone and total reversal after periaqueductal gray lesions in the rat. Eur J Pharmacol. 1987c;142:51–60. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(87)90653-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]