Abstract

The lack of robust methods for culturing Cryptosporidium parasites remains a major challenge and is hampering efforts to screen for anti-cryptosporidial drugs. In existing culture methods, monolayers of mammalian epithelial cells are inoculated with oocysts. The system supports an initial phase of asexual proliferation of the parasite. For reasons that are not clear, development rapidly declines within 2 to 3 days. The unexpected report of C. parvum culture in the absence of host cells, and the failure of others to reproduce the method, prompted us to apply quantitative PCR to measure changes C. parvum DNA levels in cell-free cultures, and parasite-specific antibodies to identify different life cycle stages. Based on this approach, which has not been applied previously to analyze C. parvum growth in cell-free culture, we found that the concentration of C. parvum DNA increased by about 5-fold over 5 days of culture. Immuno-labelling of cultured organisms revealed morphologically distinct stages, only some of which reacted with Cryptosporidium-specific monoclonal antibodies. These observations are indicative of a modest proliferation of C. parvum in cell-free culture.

Cryptosporidium parvum (Apicomplexa) is one of the most common agents for cryptosporidiosis, an intestinal infection typically associated with transient diarrhea in humans and ruminants. (Guerrant, 1997; Griffiths, 1998). The parasite completes its life cycle in a single host and is transmitted via environmentally resistant oocysts. Asexual multiplication takes place in the intestinal epithelium.

Although the first report of successful culture of C. parvum in monolayers of epithelial cells dates back 25 yr (Current and Haynes, 1984), existing methods are limited by the transient nature of parasite multiplication. Only small numbers of C. parvum oocysts are produced in some cell lines, including Caco-2 (human colon adenocarcinoma), MDBK (bovine kidney), and HCT-8 cells (human ileocecal adenocarcinoma) (Buraud et al., 1991; Villacorta et al., 1996; Hijjawi et al., 2001), and primary cell culture (Yang et al., 1996). Work in this laboratory, and by others, has shown that many cells infected with C. parvum are released from the monolayer and undergo apoptosis (Griffiths et al., 1994; Chen et al., 1998; Ojcius et al., 1999; Widmer et al., 2000). Improving cell anchorage only marginally increases the density of infected monolayer cells and does not extend parasite survival.

Because most of the C. parvum life cycle takes place within the host cell, the report of extracellular development of C. parvum parasites (Hijjawi et al., 2004) was unexpected. Some authors observed new parasite forms in cell-free culture (Rosales et al., 2005; Thompson, et al., 2005; Karanis et al., 2008). Supported by phylogenetic analyses of diagnostic DNA sequences (Carreno et al., 1999; Barta and Thompson, 2006), these observations were interpreted as consistent with the proposed classification of the genus Cryptosporidium in the apicomplexan class Gregarinia. However, reports on cell-free culture have remained controversial (Girouard et al., 2006; Woods and Upton, 2007). We used DNA quantification to assess C. parvum proliferation in cell-free culture. Consistent with C. parvum extracellular development, we observed a limited, but measurable, increase in DNA concentration during culture. Immunofluorescence analysis was consistent with the emergence of morphologically and antigenically distinct parasite forms.

For immunofluorescence analysis, oocysts purified from feces of experimentally infected animals were surface sterilized in 0.5% sodium hypochloride for 5 min on ice and washed 3 times in PBS. Doses of 6 × 106 – 6 × 107 oocysts were split into 2 equal portions, an experimental sample and a heat-inactivated control. To induce excystation, oocyst suspensions were incubated at 37 C for 60 min in PBS supplemented with 0.8% taurocholic acid. The control was heat-inactivated at 85 C for 15 min (Fayer, 1994). Live and inactivated samples were then inoculated into 12 ml DMEM medium (Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's medium, Sigma, St Louis, Missouri) supplemented with 5–10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 5% normal goat serum (NGS), 50 U/ml penicillin, and 50 µg/ml streptomycin (Cellgro, Manassas, Virginia) in 10-cm diameter Petri dishes. In some experiments, parasites were labeled with 1 µM of the carbocyanine membrane dye DiI (Invitrogen/Molecular Probes Vybrant CM-DiI cell-labeling solution, Carlsbad, California) (Table I). Plates were incubated in a humidified incubator at 37 C, 5% CO2. The cultures were observed daily and those with visible bacterial or fungal contamination were discarded. As expected when incubating oocysts extracted from feces, contamination was observed in about 10% of the cultures.

Table I.

Summary of culture experiments analyzed by real-time PCR.

| Experiment* | Isolate | Oocyst age | DMEM supplement |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | TUM1† | 2 mo | 5% FBS/5%NGS§ |

| 2 | TUM1 | 2 mo | 5% FBS/5%NGS |

| 3 | TUM1 | 3 mo | 5% FBS/5%NGS |

| 4 | TUM1 | 3 mo | 5% FBS/5%NGS |

| 5 | TUM1 | 4 mo | 5% FBS/5%NGS |

| 6 | TUM1 | <1 mo | 10% FBS |

| 7 | IOWA‡ | unknown | 10% FBS |

| 8 | TUM1 | <2 mo | 10% FBS |

Numbered as in Figure 2.

Bovine C. parvum from Massachusetts.

FBS, fetal bovine serum; NGS, normal goat serum.

Cultured parasites were harvested by centrifugation (5,000 g) after various periods of culture as indicated in Figure 1. Pellets were washed in PBS, fixed in 100% methanol for 15 min at room temperature, and dried onto 3-well Teflon slides (Meridian Diagnostics, Cincinnati, Ohio). Slides were blocked with 50 µl/well of 1% normal goat serum for 30 min at room temperature. Samples were then reacted with primary antibody (monoclonal or polyclonal) for 30 min at room temperature. Both monoclonal antibodies react with the sporozoites and the intracellular stages of C. parvum. The immunoblot profile of each antibody against different C. parvum isolates is identical. Both antibodies react with periodate-sensitive carbohydrate epitopes that are shared by different parasite antigens. The monoclonal 4H6 reacts with antigens of 70, 78, 300, and 900 kDa; monoclonal 2E5 reacts with the antigens of 40, 300, and 900 kDa. The polyclonal antibody is reactive against C. parvum oocysts and sporozoites. Subsequently, slides were washed 3 times with PBS and incubated with a 1/2,000 dilution of Alexa 488 conjugated secondary antibody (Invitrogen/Molecular Probes, Carlsbad, California; goat anti-rabbit or goat-anti-mouse). Slides were again washed 3 times with PBS, covered with mounting medium and a cover slip. An irrelevant monoclonal antibody was included in parallel slides to confirm specificity of labeling. Images were captured with a 100× oil immersion objective mounted on an Olympus BX40 epifluorescent microscope fitted with a Nikon Coolpix 995 digital camera. DiI labeling and immunofluorescence were not applied to samples used for real-time PCR analysis.

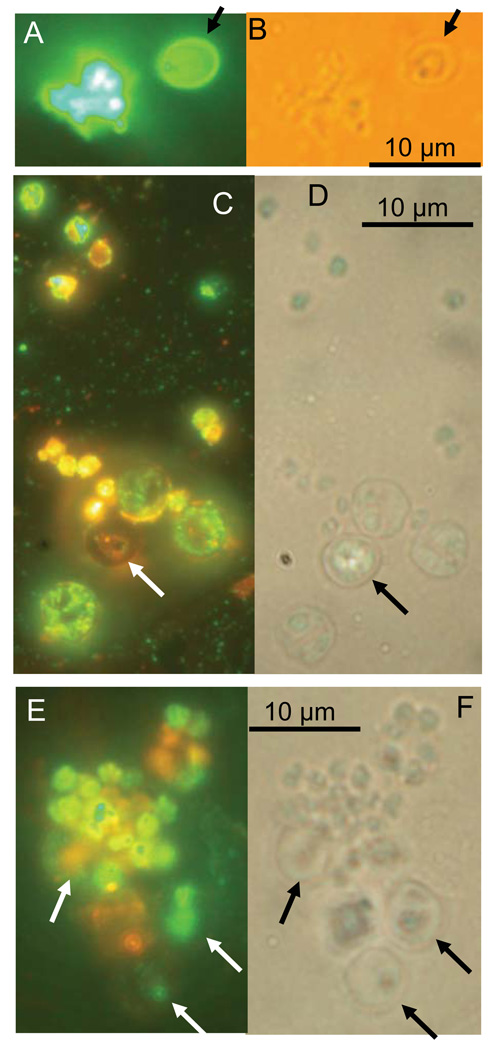

FIGURE 1.

Immunofluorescence and phase-contrast images of C. parvum cultured for 10 and 37 days. (A, B) Thirty-seven day culture stained with a polyclonal antibody (Theodos et al., 1998). (C, D) Ten day culture stained with monoclonal antibody 4H6 and counter-stained with DiI. (E, F) Ten day culture stained with monoclonal 2E5 and counter-stained with DiI. Arrows indicate empty or partially empty oocyst shells. Note lack of immunolabeling of oocyst walls by monoclonal antibodies (C, E). Labelled putative proliferative stages are visible in A, C and E. Orange fluorescence is from DiI used as counterstain. In analogy to Hijjawi et al. (2004), spherical shapes with punctated labeling (C) were observed.

For quantitative PCR analysis, oocysts of C. parvum from experimentally infected calves were surface sterilized as described above. Doses of 9 × 106 – 9 × 107 oocysts were split into 3 equal groups and randomly assigned to the experimental sample, the uncultured control, and the heat-inactivated control. Each treatment was run in triplicate for a total of 9 samples per experiment. The experimental samples and heat-inactivated controls were incubated at 37 C for 60 min in 0.8% taurocholic acid to induce excystation. The experimental sample was then inoculated into 12 ml of media (Table I). The heat-inactivated control was inactivated at 85 C for 15 min and inoculated into media as the experimental samples. Oocyst samples assigned to the uncultered controls were stored at 4 C for the duration of the experiment. To exclude the possibility that DNA recovery from the uncultured oocyst samples may be less efficient, uncultered oocyst suspensions were exposed to excystation condition prior to DNA extraction. This uncultured control thus represents the true experimental baseline which was subjected to the identical treatment as the experimental culture, except that it was not incubated at 37 C in medium. Cultures (live and heat-inactivated) were incubated at 37 C, 5% CO2 for 5 days to induce parasite proliferation, while the uncultured control was kept at 4 C.

Following a 5-day incubation period, the uncultured control samples (triplicates) were exposed to the same excystation conditions in 0.8% taurocholic acid as described above. The 3 replicate experimental and heat-inactivated cultures were harvested by centrifugation at 5,000 g and washed in PBS. DNA was then extracted from all 3 treatment groups (3 × 3=9 samples) in parallel using the HighPure PCR kit (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, Indiana). DNA was eluted in 100 µl elution buffer. A portion of 5 µl of DNA was real-time PCR amplified in a LightCycler instrument (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, Indiana) using primers specific for the C. parvum glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (forward primer AACAAACTGTCTTGCTCCTT; reverse primer TTGCCACCCTTGCTTG). Because the cultures contain bovine serum, we verified that the primer sequences did not occur in bovine genomic sequence available in GenBank. Amplification curves and crossing points were acquired with LightCycler 3 Data Analysis software (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, Indiana). A GAPDH standard curve was constructed using 7 triplicates of genomic DNA serially diluted at a 1:4 ratio. Two experiments (6, 7) were also analyzed using the C. parvum MSG minisatellite PCR assay (Tanriverdi et al., 2006) to ensure that the results were independent of the PCR assay, and to confirm the genotype of the cultured samples. The primers for the MSG amplicon were TGGAATGATAATTGGACC and GGAGTTTCTGAGACAC.

Figure 1 shows matched fluorescent and visible light micrographs of cellular precipitate recovered from culture medium at 10 and 37 days post-inoculation. Life cycle stages which are clearly different from the oocysts and sporozoites that were added to the medium. The parasite preparations were labeled with a polyclonal antibody (Theodos et al., 1998), which recognizes all C. parvum life cycle stages (Fig. 1A), including the oocyst wall as well as monoclonal antibodies that do not recognize the oocyst wall, but bind to sporozoites and intracellular stages (Figs. 1C, E). In some experiments, the lipophylic dye DiI was used as a counterstain (Figs. 1C, E). The fact that the 2 monoclonals (4H6, panel C, and 2E5 [1E]) did not bind to oocyst walls, but reacted strongly with other stages as well as with some antigen remaining inside the oocysts, is consistent with the labeling being specific and with C. parvum development taking place. The absence of labeled oocyst walls in Figures 1C and E is consistent with the previous characterization of these monoclonals, which showed no reactivity with the oocyst wall (A. S. Sheoran, unpubl. obs.). To ensure that antibody binding was specific, parallel samples were labeled with isotype control antibodies. As a control for 2E5, an IgG monoclonal specific for Encephalitozoon intestinalis was used, whereas the control for 4H6 was an IgM specific for Enterocytozoon bieneusi spores (Sheoran et al., 2005). No immunofluorescence was observed in samples labeled with these antibodies (data not shown).

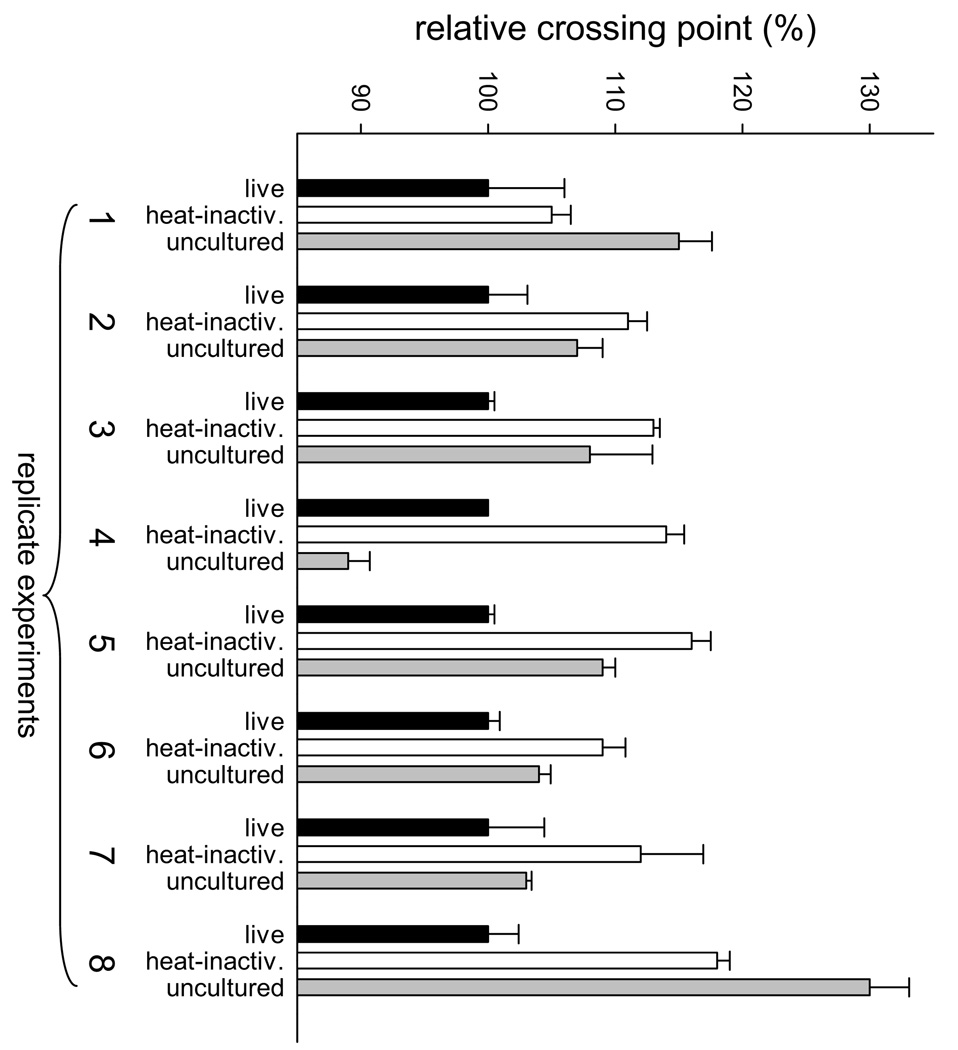

Eight independent culture experiments, each conducted at different times and in triplicate, were performed and analyzed by real-time quantitative PCR (Fig. 2, Table I). DNA concentration was estimated using the PCR crossing point, defined as the number of temperature cycles needed to reach a pre-determined fluorescence threshold. The relative crossing points observed with the C. parvum GAPDH PCR assay were normalized against the experimental sample, which was set equal 100%. By definition, crossing point and DNA concentration are inversely correlated. As shown in Figure 2, in 7 of 8 experiments, the concentration of C. parvum DNA was highest in the live culture as compared to the uncultured and heat-inactivated controls. The only exception was experiment 4, where the DNA concentration in the uncultured control appeared to be the highest. This experiment is shown here because the relative crossing point value for this sample did not deviate sufficiently from the remaining 7 replicates to be considered an outlier (Dixon’s test, P>0.05; Grubb’s test, P>0.1). We observed that in the heat-inactivated controls the DNA concentration in 6 of 8 experiments was lower than in the uncultured oocysts control, which could be the result of DNA degradation during incubation of the inactivated cultures. However, the fact that in 7 of 8 replicates, the DNA concentration in the experimental sample exceeded that in the uncultered control argues for parasite replication in culture. Experiments 6 and 7 were also analyzed with a PCR assay specific for the MSG marker, which gave analogous results to the GAPDH PCR assay (data not shown). Mean MSG crossing point ranks were live < uncultured < heat-inactivated.

FIGURE 2.

Quantification of C. parvum in cell-free culture. DNA was extracted from 12 ml of 5-day-old cultures and C. parvum DNA quantified by amplifying a 129-bp fragment of the C. parvum GAPDH gene. Shown are normalized real-time PCR crossing points expressed as % of the experimental sample (black bars). Lower crossing point values convert to higher DNA concentration. Independently replicated culture experiments are numbered from 1 to 8 as in Table I. White bars (controls) represent cultures seeded with the same number of heat-inactivated oocysts. Gray bars represent real-time PCR results from equivalent numbers of uncultered, excysted oocysts. Error bars indicate SD (n=3).

To assess the level of DNA replication during the 5-day culture period, GAPDH crossing points were converted to DNA concentration using the experimentally derived regression: Cycle Number= 31.75–3.6 × log DNA concentration. Conversion of the mean crossing point difference between experimental cultures and heat-inactivated controls yielded an estimated 5.6-fold increase in C. parvum DNA concentration over a 5-day culture period.

Because of the controversy surrounding reports of C. parvum proliferation in cell-free culture, we wanted to independently examine the ability of C. parvum multiplying in cell-free conditions. As discussed by Wood and Upton (2007), parasite morphology is an unreliable indicator of parasite multiplication, particularly for a parasite that is extracted from feces and is potentially contaminated with other microorganisms. We used the most discriminating methods available to us, i.e., immunofluorescence and quantitative PCR. Although these methods are less likely to be affected by contaminants, we maximized the stringency of the analyses by using 3 antibody preparations and 2 PCR assays. Together, these methods indicate that the parasite multiplied in the medium.

Using the generally accepted model of a C. parvum life cycle with 8 first-generation merozoites and 4 second-generation merozoites (Pohlenz et al., 1978), an estimated duration of the asexual phase of the life cycle of about 4 days (Current and Haynes, 1984), and exponential growth, the DNA concentration during the 5-day culture period should have increased by approximately 70-fold (321.25). We measured only a fraction of this ratio, indicating that parasite multiplication was far from optimal. Measurements of growth rates, as opposed to the current single-point experiments, may reveal whether the low rate of multiplication is due to the fact that only a minority of sporozoites in the inoculum actually develop, or whether a large number of parasites survived but multiplied inefficiently. If the latter is true, the annotation of the C. parvum and C. hominis genomes (Abrahamsen et al., 2004; Xu et al., 2004) and the inferred dependence of the intracellular parasite on host cell metabolites (Striepen et al., 2004) could guide further experimentation to maximize parasite multiplication.

Acknowledgments

Financial support from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (AI055347) and the National Center for Research Resources (K01 RR17383) is gratefully acknowledged. Some oocysts were obtained from NIAID's Biodefense & Emerging Infections Research Resources Repository, Manassas, Virginia.

LITERATURE CITED

- Abrahamsen MS, Templeton TJ, Enomoto S, Abrahante JE, Zhu G, Lancto CA, Deng M, Liu C, Widmer G, Tzipori S, et al. Complete genome sequence of the apicomplexan, Cryptosporidium parvum. Science. 2004;304:441–445. doi: 10.1126/science.1094786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barta JR, Thompson RCA. What is Cryptosporidium? Reappraising its biology and phylogenetic affinities. Trends in Parasitology. 2006;22:463–468. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2006.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buraud M, Forget E, Favennec L, Bizet J, Gobert JG, Deluol AM. Sexual stage development of cryptosporidia in the Caco-2 cell line. Infection and Immunity. 1991;59:4610–4613. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.12.4610-4613.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carreno RA, Martin DS, Barta JR. Cryptosporidium is more closely related to the gregarines than to coccidia as shown by phylogenetic analysis of apicomplexan parasites inferred using small-subunit ribosomal RNA gene sequences. Parasitology Research. 1999;85:899–904. doi: 10.1007/s004360050655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen XM, Levine SA, Tietz P, Krueger E, McNiven MA, Jefferson DM, Mahle M, LaRusso NF. Cryptosporidium parvum is cytopathic for cultured human biliary epithelia via an apoptotic mechanism. Hepatology. 1998;28:906–913. doi: 10.1002/hep.510280402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Current WL, Haynes TB. Complete development of Cryptosporidium in cell culture. Science. 1984;224:603–605. doi: 10.1126/science.6710159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fayer R. Effect of high temperature on infectivity of Cryptosporidium parvum oocysts in water. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 1994;60:2732–2735. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.8.2732-2735.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girouard D, Gallant J, Akiyoshi DE, Nunnari J, Tzipori S. Failure to propagate Cryptosporidium spp. in cell-free culture. Journal of Parasitology. 2006;92:399–400. doi: 10.1645/GE-661R.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths JK. Human cryptosporidiosis: Epidemiology, transmission, clinical disease, treatment, and diagnosis. Advances in Parasitology. 1998;40:37–85. doi: 10.1016/s0065-308x(08)60117-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths JK, Moore R, Dooley S, Keusch GT, Tzipori S. Cryptosporidium parvum infection of Caco-2 cell monolayers induces an apical monolayer defect, selectively increases transmonolayer permeability, and causes epithelial cell death. Infection and Immunity. 1994;62:4506–4514. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.10.4506-4514.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrant LR. Cryptosporidiosis: An emerging, highly infectious threat. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 1997;3:51–57. doi: 10.3201/eid0301.970106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hijjawi NS, Meloni BP, Morgan UM, Thompson RC. Complete development and long-term maintenance of Cryptosporidium parvum human and cattle genotypes in cell culture. International Journal of Parasitology. 2001;31:1048–1055. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(01)00212-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hijjawi NS, Meloni BP, Morgan UM, Thompson RC, Ng'anzo M, Ryan UM, Olson ME, Cox PT, Monis PT, Thompson RC. Complete development of Cryptosporidium parvum in host cell-free culture. International Journal of Parasitology. 2004;34:769–777. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2004.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karanis P, Kimura A, Nagasawa H, Igarashi I, Suzuki N. Observations on Cryptosporidium life cycle stages during excystation. Journal of Parasitology. 2008;94:298–300. doi: 10.1645/GE-1185.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojcius DM, Perfettini JL, Bonnin A, Laurent F. Caspase-dependent apoptosis during infection with Cryptosporidium parvum. Microbes and Infection. 1999;1:1163–1168. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(99)00246-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pohlenz J, Bemrick WJ, Moon HW, Cheville NF. Bovine cryptosporidiosis: A transmission and scanning electron microscopic study of some stages in the life cycle and of the host-parasite relationship. Veterinary Pathology. 1978;15:417–427. doi: 10.1177/030098587801500318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosales MJ, Cordon GP, Moreno MS, Sanchez CM, Mascaro C. Extracellular like-gregarine stages of Cryptosporidium parvum. Acta Tropica. 2005;95:74–78. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2005.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheoran AS, Feng X, Kitaka S, Green L, Pearson C, Didier ES, Chapman S, Tumwine JK, TZIPORI S. Purification of Enterocytozoon bieneusi from stools and production of specific antibodies. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2005;43:387–392. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.1.387-392.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Striepen B, Pruijssers AJ, Huang J, Li C, Gubbels MJ, Umejiego NN, Hedstrom L, Kissinger JC. Gene transfer in the evolution of parasite nucleotide biosynthesis. Proceeding of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 2004;101:3154–3159. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0304686101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanriverdi S, Markovics A, Arslan MO, Itik A, Shkap V, Widmer G. Emergence of distinct genotypes of Cryptosporidium parvum in structured host populations. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2006;72:2507–2513. doi: 10.1128/AEM.72.4.2507-2513.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theodos CM, Griffiths JK, D'Onfro J, Fairfield A, Tzipori S. Efficacy of nitazoxanide against Cryptosporidium parvum in cell culture and in animal models. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 1998;42:1959–1965. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.8.1959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RC, Olson ME, Zhu G, Enomoto S, Abrahamsen MS, Hijjawi NS. Cryptosporidium and cryptosporidiosis. Advances in Parasitology. 2005;59:77–158. doi: 10.1016/S0065-308X(05)59002-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villacorta I, de Graaf D, Charlier G, Peeters JE. Complete development of Cryptosporidium parvum in MDBK cells. FEMS Microbiology Letters. 1996;142:129–132. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1996.tb08419.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widmer G, Corey EA, Stein B, Griffiths JK, Tzipori S. Host cell apoptosis impairs Cryptosporidium parvum development in vitro. Journal of Parasitology. 2000;86:922–928. doi: 10.1645/0022-3395(2000)086[0922:HCAICP]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods KM, Upton SJ. In vitro development of Cryptosporidium parvum in serum-free media. Letters in Applied Microbiology. 2007;44:520–523. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2006.02101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu P, Widmer G, Wang Y, Ozaki LS, Alves JM, Serrano MG, Puiu D, Manque P, Akiyoshi D, Mackey AJ, et al. The genome of Cryptosporidium hominis. Nature. 2004;431:1107–1112. doi: 10.1038/nature02977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S, Healey MC, Du C, Zhang J. Complete development of Cryptosporidium parvum in bovine fallopian tube epithelial cells. Infection and Immunity. 1996;64:349–354. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.1.349-354.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]