Abstract

Mechanism-based inhibitors of class A β-lactamases, such as sulbactam, undergo a complex series of chemical reactions in the enzyme active site. Formation of a trans-enamine acyl-enzyme via a hydrolysis-prone imine is responsible for transient inhibition of the enzyme. Although the imine to enamine tautomerization is crucial to inhibition of the enzyme, there is no experimental data to suggest how this chemical transformation is catalyzed in the active site. In this report, we show that E166 acts as a general base to promote the imine to enamine tautomerization.

The active sites of class A β-lactamases possess a complex ensemble of conserved amino acids that participate in the acylation and deacylation mechanisms. This ensemble includes, but is not limited to, the nucleophilic serine (S70), K73, S130, E166, and K234. K73, located three residues to the C-terminal side of the nucleophilic serine is required for serine acyl-enzyme formation (1). There are two proposed mechanisms for the acylation step: 1) Upon substrate binding, a proton is shuttled from K73 to E166 via a conserved active-site water and S70. This gives an unprotonated K73 and protonated E166. Then, in a concerted general base process, K73 promotes S70 addition to the β-lactam carbonyl (2). However, there is evidence supporting the presence of a protonated K73 in the apo enzyme based on NMR titrations, pKa calculations, and kinetics and these data argue against a neutral K73 acting as a general base (1, 3, 4). 2) A second, and more widely-accepted mechanism, proposes that E166 activates the catalytic water, which, in turn, deprotonates S70 and primes the nucleophile for attack on the β-lactam carbonyl. For the deacylation mechanism, it is widely accepted that E166 enables the deprotonation of the water molecule for catalytic acyl-enzyme hydrolysis (5, 6). Mutation of E166 to alanine or asparagine decreases the rate constant for acylation by as much as 100-1000-fold and decreases the microscopic rate constant for deacylation by six orders of magnitude (1). As such, kinetic data from E166N and E166A mutants indicate that acylation is possible, but impaired, in the absence of the E166 carboxylate but deacylation does not occur.

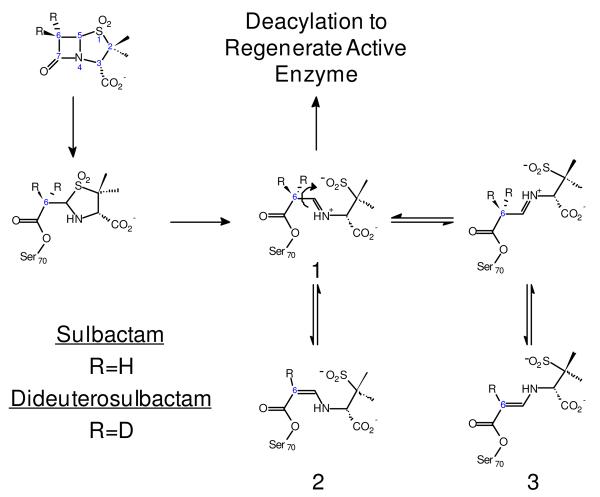

Scheme 1 shows the reaction scheme between SHV-1, an Ambler class A β-lactamase, and sulbactam, a mechanism-based inhibitor. Following the noncovalent association step, S70 is acylated opening the β-lactam ring of the inhibitor. This is followed by cleavage of the C5-S bond and opening the thiazolidine ring with concomitant formation of a C5-N imine (species 1, Scheme 1). This imine intermediate partitions between three pathways: tautomerization to form both cis- and trans-enamines (species 2 and 3, respectively, Scheme 1); or covalent modification resulting in irreversibly inactivated enzyme (not shown); or hydrolysis which liberates active enzyme. Imtiaz et al. were first to propose that deprotonation of the imine at C6 is likely to be carried out by the conserved E166 via an intervening crystallographic water (7).

Scheme 1.

Using wild-type (WT) SHV-1 and SHV E166A, we provide spectroscopic evidence that the glutamic acid at position 166 facilitates imine/enamine tautomerization of the sulbactam acyl-enzyme by deprotonation/protonation at C6. This observation is made with the aid of a Raman microscope, which allows us to undertake Raman difference spectroscopic analyses in single enzyme crystals (8). This approach, termed Raman crystallography, provides a means of characterizing chemical events within the crystals, especially enzyme reactions. Raman spectra are recorded as a function of time and the difference spectrum [enzyme-substrate complex] minus [enzyme] provides the Raman spectra of intermediates on the reaction pathway.

In order to “track” tautomerization of the acyl-enzyme, we rely on deuterium incorporation or loss at C6 of the enamine's double bond moiety, which shifts the C=C stretch to lower or higher wavenumbers, respectively, in the Raman spectrum. Depending on the experiment, the deuterium at C6 of the enamine's double bond is from one of two sources—either an isotopologue of sulbactam, 6,6-dideuterosulbactam (6,6-DDS), or the solvent, D2O. Based on the following data, we confirm the role, aside from deacylation, for E166 proposed by Imtiaz et al. (7): E166 facilitates deprotonation/protonation at C6 via the intervening structurally conserved water in the WT enzyme to facilitate the imine/enamine tautomerization.

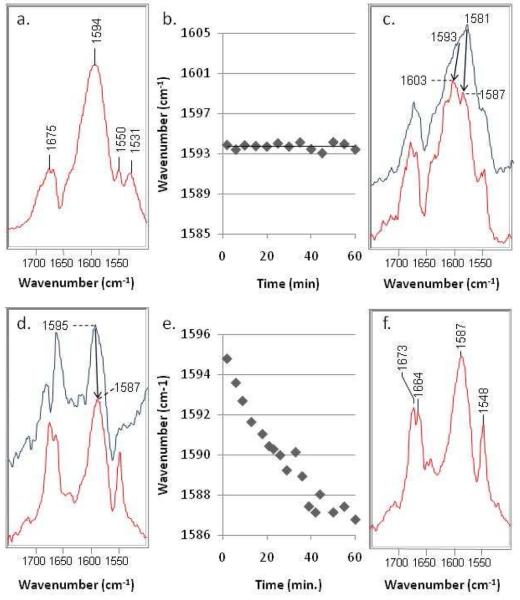

In the first experiment, 6,6-DDS is reacted with SHV E166A. The difference spectrum of the 6,6-DDS/E166A complex is shown in Figure 1a. The 1594 cm−1 peak is assigned to the O=C-DC=CH-NH stretch of the trans-enamine. The trans-enamine vibration from 6,6-DDS is down-shifted by 9 cm−1 compared to the unlabeled compound due to the deuterium at C6 (see spectrum of sulbactam/E166A in Supplemental Figure 1). The frequency of the trans-enamine vibration of 6,6-DDS in H2O is essentially the same for a period of one hour (Fig. 1b). As shown in Scheme 1, inter-conversion between the trans-enamine and the imine requires either proton abstraction (imine→enamine) or addition (enamine→imine) at C6. For the labeled compound, repeated deprotonation/reprotonation cycles at C6 would result in loss of deuterium at C6 and replacement by hydrogen from H2O. This isotope scrambling would, in turn, shift the frequency of 6,6-DDS's trans-enamine band (1594 cm−1) to the same position as the unlabeled compound's trans-enamine band (1603 cm−1). Nonetheless, for the E166A form, a time-dependence is not observed for the 1594 cm−1 feature of 6,6-DDS (Fig. 1b) and is strong evidence that tautomerization does not occur on the observed time scale between E166A-bound intermediates of 6,6-DDS. The features that appear in each of the difference spectra around 1670 cm−1 indicate a small ligand-induced conformational change (Fig. 1a, c, d, and f) (9).

Figure 1.

a) 6,6-DDS/SHV E166A difference spectrum at 10 min., b) Frequency of the trans-enamine stretch as a function of time for the reaction between 6,6-DDS and SHV E166A, c) 6,6-DDS/WT SHV-1 difference spectra at 2 min. (blue) and 60 min. (red), d) Sulbactam/WT SHV-1 difference spectra in D2O at 2 min. (blue) and 60 min. (red), e) Frequency of the trans-enamine stretch as a function of time for the reaction between sulbactam and WT SHV-1 in D2O, f) 6,6-DDS/WT SHV-1 difference spectrum in D2O at 10 min.

The difference spectra of the 6,6-DDS/WT SHV-1 complexes are shown in Fig. 1c, where the effects of restoring the glutamic acid at position 166 are immediately obvious: First, the spectra are more complex than those obtained with SHV E166A, which indicates that additional acyl-enzyme species are formed with the WT enzyme. Second, some features in the 6,6-DDS difference spectra are time-dependent from 1 to 60 min., which suggests that D→H exchange occurs with H2O. The region of the spectra shown contains bands largely due to stretching features from a number of acyl-enzymes. For 6,6-DDS, the cis-enamine is marked by a band at 1581 cm−1 in the 10 min. spectrum (top). After 60 min., the position of this band shifts to 1587 cm−1, indicating near complete D→H exchange with the solvent at C6. A similar phenomenon is observed for the trans-enamine vibration of deuterated sulbactam, which appears as a shoulder near 1593 cm−1 in the 10 min. spectrum (blue) and 1603 cm−1 in the 60 min. spectrum (red). The complexity of the 6,6-DDS/WT SHV-1 difference spectra prohibits kinetic traces as in Fig. 1b or Fig 1e. For comparison, the sulbactam/WT SHV-1 difference spectrum is provided in Supplemental Figure 2 and resembles the 6,6-DDS/WT SHV-1 difference spectrum at 60 min. following complete D→H exchange at C6 (Fig. 1c, bottom).

In the preceding section, we observed the labeled inhibitor lose a deuterium to the solvent as it tautomerized between the imine and enamine in the active site of the WT enzyme. In the “reverse” experiment, presented next, unlabeled sulbactam is reacted with the WT enzyme in D2O, which allows us to observe the incorporation of deuterium into the enamine skeleton as a function of time. The sulbactam/WT SHV-1 difference spectrum in D2O at 2 min. is shown in Figure 1d. The 1595 cm−1 peak is assigned to the O=C-HC=CH-ND stretch of the trans-enamine. (Note: Compared to the sulbactam/SHV-1 difference spectrum in H2O, the starting frequency of the trans-enamine stretch in the sulbactam/WT SHV-1 difference spectrum in D2O is lower due to rapid NH→ND exchange.) During repeated imine/enamine tautomerization of the acyl-enzyme intermediate, the hydrogen at C6 is replaced by deuterium from the solvent. Following complete H→D exchange at C6, the trans-enamine stretch falls to 1587 cm−1 at 60 min. (Fig. 1d, red). The frequency of the trans-enamine stretch is plotted as a function of time in Fig. 1e, which illustrates that H→D exchange at C6 is complete around 60 min. At this point, the sulbactam/WT SHV-1 in D2O difference spectrum (Fig. 1d, bottom) is identical to the 6,6-DDS/WT SHV-1 difference spectrum in D2O (Fig. 1f).

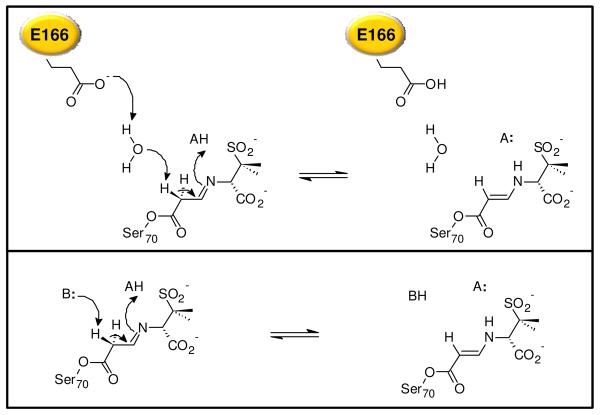

To date, there is no experimental evidence implicating E166 in the mechanism of imine/enamine tautomerization of ‘suicide’ inhibitors, despite the importance of this interconversion to transient inhibition of the enzyme. Our interpretation of the Raman data begins with the imine intermediate of sulbactam. In order for this species to tautomerize to the trans-enamine, deprotonation at C6 is required. Interestingly, the Raman data show that both WT SHV-1 and SHV E166A form a predominant population of the enamine-type intermediates with both sulbactam and 6,6-DDS. For WT SHV-1, deprotonation at C6 of the imine is mediated by E166, possibly via an intervening water molecule (Fig. 2, top). Using stereospecifically monodeuterated sulfones, Brenner and Knowles showed that the 6β hydrogen is preferentially abstracted in the formation of the transiently stable enamine intermediate. In SHV E166A, an alanine is substituted for the general base; consequently, another pathway for deprotonation at C6 must exist in the absence of glutamic acid (Fig. 2, bottom). The crystal structure of SHV E166A shows that the normally catalytic water is only moved 1.2 Å from its position in the WT enzyme, and the smaller E166A side chain creates space a second water ~2.8 Å away. While it is possible that the same water is responsible for proton/deprotonation at C6 of the imine in SHV E166A, our data can neither support nor refute its role in the tautomerization reaction. The time resolution of the Raman experiment cannot reliably distinguish between differences in the rate of formation of the trans-enamine for WT SHV-1 and SHV E166A; however, a predominant population of the trans-enamine is evident in the earliest difference spectra at 2 min. for both enzymes.

Figure 2.

Proposed mechanism for imine to trans-enamine tautomerization for WT SHV-1 (top) and SHV E166A (bottom).

Furthermore, the Raman data show that E166 affects the rate at which the enamine can be tautomerized to the imine. In the reaction between 6,6-DDS and WT SHV-1 or SHV E166A, the tautomerization between imine and enamine is tracked by changes in the enamine stretching frequency as a function of time. A change in the enamine stretching frequency reflects isotope exchange at C6 and can only occur in the case of repeated protonation/deprotonation events at this carbon. The Raman data with 6,6-DDS/SHV E166A show that, once the trans-enamine is formed, tautomerization back to the imine is drastically slowed, such that it is not detectable during the lifetime of the experiment (Fig. 1a and 1b). When the same experiment is performed with the WT enzyme, the trans-enamine's deuterium atom at C6 is replaced by a hydrogen atom from the solvent over a period of 1 hour (Fig. 1c). The “reverse” experiment, in which unlabeled sulbactam is reacted with the WT enzyme in D2O, reveals incorporation of deuterium into the enamine skeleton over 60 min. and thus provides supporting evidence (Fig. 1d-f). Knowledge of the imine/enamine tautomerization mechanism enzyme may find broad use in design of inhibitors based on the penam sulfone and clavam scaffolds.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

SUPPORTING INFORMATION AVAILABLE

Details of the experimental procedures and Graphs S1 and S2. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

National Institutes of Health Grant RO1 GM54072 (P.R.C.), the Case Western Reserve University MSTP Program (M.K.), and Robert A. Welch Foundation Grant N-0871 (J.D.B.) supported this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lietz EJ, Truher H, Kahn D, Hokenson MJ, Fink AL. Lysine-73 is involved in the acylation and deacylation of β-lactamase. Biochemistry. 2000;39:4971–4981. doi: 10.1021/bi992681k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meroueh SO, Fisher JF, Schlegel HB, Mobashery S. Ab initio QM/MM study of class A β-lactamase acylation: dual participation of Glu166 and Lys73 in a concerted base promotion of Ser70. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:15397–15407. doi: 10.1021/ja051592u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Damblon C, Raquet X, Lian LY, Lamotte-Brasseur J, Fonze E, Charlier P, Roberts GC, Frere JM. The catalytic mechanism of β-lactamases: NMR titration of an active-site lysine residue of the TEM-1 enzyme. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:1747–1752. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.5.1747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lamotte-Brasseur J, Lounnas V, Raquet X, Wade RC. pKa calculations for class A beta-lactamases: influence of substrate binding. Protein Sci. 1999;8:404–409. doi: 10.1110/ps.8.2.404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Escobar WA, Tan AK, Fink AL. Site-directed mutagenesis of β-lactamase leading to accumulation of a catalytic intermediate. Biochemistry. 1991;30:10783–10787. doi: 10.1021/bi00108a025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hermann JC, Ridder L, Holtje HD, Mulholland AJ. Molecular mechanisms of antibiotic resistance: QM/MM modelling of deacylation in a class A β-lactamase. Org Biomol Chem. 2006;4:206–210. doi: 10.1039/b512969a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Imtiaz U, Billings EM, Knox JR, Mobashery S. A structure-based analysis of the inhibition of class A β-lactamases by sulbactam. Biochemistry. 1994;33:5728–5738. doi: 10.1021/bi00185a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carey PR. Raman crystallography and other biochemical applications of Raman microscopy. Annu Rev Phys Chem. 2006;57:527–554. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physchem.57.032905.104521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kalp M, Totir MA, Buynak JD, Carey PR. Different intermediate populations formed by tazobactam, sulbactam, and clavulanate reacting with SHV-1 β-lactamases: Raman crystallographic evidence. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:2338–2347. doi: 10.1021/ja808311s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.