Abstract

The prevalence of substance use disorders (SUD) and aspects of the help-seeking process among a high-risk sample of 946 students at one large public university were assessed in personal interviews during the first three years of college. After statistically adjusting for purposive sampling, an estimated 46.8%wt of all third-year students met DSM-IV criteria for SUD involving alcohol and/or marijuana at least once. Of 548 SUD cases, 3.6% perceived a need for help with substance use problems; 16.4% were encouraged by someone else to seek help. Help-seeking was rare among SUD cases (8.8%), but significantly elevated among individuals who perceived a need (90.0%) or experienced social pressures from parents (32.5%), friends (34.2%), or another person (58.3%). Resources accessed for help included educational programs (38%), health professionals (27%), and twelve-step programs (19%). College students have high rates of substance use problems but rarely recognize a need for treatment or seek help. Results highlight the opportunity for early intervention with college students with SUD.

Keywords: treatment-seeking, help-seeking, college students, substance use disorder, longitudinal studies

1. Introduction

Young adulthood is the peak developmental period for the onset of drug problems (Chen, O’Brien, & Anthony, 2005; Fillmore, Johnstone, Leino, & Ager, 1993; Harford, Grant, Yi, & Chen, 2005; Hilton, 1991). National surveys estimate that almost a quarter (21.2%) of 18 to 25 year olds meet criteria for an alcohol or illicit drug use disorder, far exceeding the estimates for younger or older persons (8.8%, 7.3%, respectively) (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2006). While the vast majority of drug-dependent young adults do not perceive a need for drug treatment, the rate of perceived need increased significantly from 4.5% in 2004 to 8.4% 2005 among 18 to 25 year olds (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2006). National data indicate that the treatment gap—that is, the proportion of individuals meeting DSM-IV criteria for substance use disorders who have never sought help—is greater for young adults than for any other age group (Schmidt, 2007).

For college students, the patterns of recent drug use are not appreciably different from other young adults. The National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) estimates that past-year illicit drug use among 18 to 22 year olds is similar for full-time college students (37.5%), part-time students (38.5%) and non-students (38.4%) (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2005). Other evidence suggests that the transition out of high school is an important risk factor for increasing substance-related problems, rather than the transition into college per se (White, Labouvie, & Papadaratsakis, 2005). Despite the popular notion that heavy drinking and drug use are “a rite of passage” in college, the consequences for college students can be quite serious (Caldeira, Arria, O’Grady, Vincent, & Wish, 2008; Pope Jr, Ionescu-Pioggia, & Pope, 2001; Wechsler, Lee, Kuo, & Lee, 2000). Annually, more than 500,000 students are injured unintentionally while drinking alcohol, and 25% drive while under the influence of alcohol (Hingson, Heeren, Winter, & Wechsler, 2005). In 1999, approximately 38% of college students met criteria for alcohol abuse or dependence in the past year (Knight et al., 2002), and in 2001 more than 1,700 students died in unintentional alcohol-related deaths (Hingson et al., 2005).

Despite their high rates of problematic heavy drinking and drug use, college students’ help-seeking behavior is poorly understood. Prior studies of help-seeking for either substance abuse or mental health treatment have primarily focused on substance-abusing adults in the general population (Brennan, Moos, & Mertens, 1994; Kaskutas, Weisner, & Caetano, 1997; Kessler et al., 2001), arrestees and young offenders (Lennings, Kenny, & Nelson, 2006; Warner & Leukefeld, 2001), and clinical treatment samples (Cahill, Adinoff, Hosig, Muller, & Pulliam, 2003; Satre, Knight, Dickson-Fuhrmann, & Jarvik, 2003). For developmental reasons, young-adult substance abusers represent a distinct special population, and when they attend college they are further distinguished by the unique combination of social, cultural, and environmental contexts associated with college life. The need for more complete information on college students’ help-seeking becomes more urgent in light of recent evidence that substance-abusing young adults are among the least likely age group to seek treatment (Kessler et al., 2001; Schmidt, 2007). In one study, only 4% of college students with alcohol use disorders obtained treatment, and college students were less likely to seek treatment than their non-student peers (Wu, Pilowsky, Schlenger, & Hasin, 2007).

At an individual level, the factors known to influence help-seeking in the general population include both personal beliefs or attitudes and social pressures. First, consistent with the concept of readiness for change posited in the transtheoretical model of change (Connors, Donovan, & DiClemente, 2001), numerous studies have demonstrated that help-seeking for SUD problems is often motivated in part by a personal recognition that a problem exists, and a desire to change the problematic behavior. Typically, treatment-seeking is preceded by an experience of one or more significant problems in relationships, employment, and other key social roles and functions (Blomqvist, 1999; Hajema & Knibbe, 1999; Kaskutas et al., 1997; Varney et al., 1995), which act as cues to heighten one’s awareness and motivation to obtain help or treatment. There is also some indication that individuals who experience more severe symptoms of dependence have greater motivation and readiness to seek treatment (Agosti & Levin, 2004; Hartnoll, 1992; Storbjork & Room, 2008; Varney et al., 1995). Furthermore, a general willingness to seek help also appears to be influential in motivating treatment-seeking (Tucker & King, 1999). In light of what is known about psychological development during adolescence and young adulthood—for example, the heightened feelings of invincibility and propensity for risk-taking that occur during this time period (Arnett, 1996; Boyer, 2006; Donovan & Jessor, 1985; Kuhn, 2006)—it is unclear whether personal attitudes regarding help-seeking might be less salient to young adults.

Second, social pressures are also regarded as an important determinant of treatment-seeking in the general population, and are thought to be the predominant mechanism by which most people enter treatment (Schmidt & Weisner, 1999). Numerous studies have focused on formal social pressures, for example, treatment mandates handed down through the judicial system (Klag, O’Callaghan, & Creed, 2005; Storbjork & Room, 2008) or required by employers (Freedberg & Johnston, 1980; Lawental, McLellan, Grissom, Brill, & O’Brien, 1996; Storbjork & Room, 2008). Informal social pressures from family, friends, and other individuals in one’s social network are also frequently cited as motivators for treatment entry (Storbjork, 2006). During college, the level of informal pressure from family and peers, and formal pressure from the university administration varies tremendously among students. Therefore, there is a possibility that social pressures could affect help-seeking behaviors differently in college students than in the general population.

The present study aims to address this gap in our understanding of the help-seeking process among college students. To encompass the broadest possible range of treatment resources students might access, we use the term “help-seeking” to comprise any steps taken towards getting help for their substance-related problems, including but not limited to formal treatment programs. This study has three objectives: (1) to describe the prevalence of substance use disorders (SUD) involving alcohol and/or marijuana in a cohort of students during their first three years of college; (2) to estimate the extent to which substance use problems were recognized among individuals with SUD, in terms of both the individual’s own self-change behaviors, their perception of needing help or treatment for substance use problems, and their experience of any social pressures from someone else to obtain help; and (3) to describe the nature and prevalence of help-seeking behaviors among individuals with SUD.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Study Design

This study uses data from the College Life Study (CLS), a longitudinal cohort study of 1,253 undergraduate college students. All first-time, first-year students ages 17 to 19 from a large, public, mid-Atlantic university were eligible for an initial screening during summer orientation prior to their freshman year in 2004. After screening more than 3,400 incoming students (89% response rate), we selected a sample for longitudinal follow-up. Students who had used illicit drugs prior to college entry were oversampled with 100% probability to ensure adequate numbers of drug users for the study across time; students with no prior drug use were sampled with 40% probability within each race-sex cell to approximate the demographic composition of the target population. Beginning with a baseline interview during the first year of college (n=1,253, 86% response rate) and annually thereafter, face-to-face interviews were administered covering a wide variety of topics, including alcohol and other drug use. All 1,253 students in the baseline sample were eligible for each follow-up assessment, regardless of continued enrollment in college, and 85% (n=1,060) of the original 1,253 participants completed all of the first three annual interviews. Participants were given $5 for participating in the screening survey and $50 for completing each interview. An additional $20 bonus was offered to participants for completing their follow-up interviews within four weeks of their baseline anniversary. Informed consent was obtained, and the study was approved by the university’s Institutional Review Board. A federal Certificate of Confidentiality was also obtained. Interviews were administered by extensively trained staff who were typically graduate students, recent graduates, or advanced undergraduates, and supervision and spot-checks were performed at regular intervals for quality assurance. More detail regarding recruitment and retention methods are described elsewhere (Arria et al., 2008).

2.2 Participants

For the present study, we restricted the sample to 946 individuals (46% male, 71% White) who completed all three interviews and provided complete data on SUD criteria. Although continued college enrollment was not a requirement for participating in the study, most (90%) were still enrolled at the same university as of the third interview. The sample was representative of the general population of students in the 2004 cohort with respect to demographics (Arria et al., 2008). Slight but significant differences were observed between included and excluded individuals with respect to sex, baseline frequency of alcohol and marijuana use, and baseline quantity of alcohol typically consumed; however, substance use differences became non-significant when sex was held constant (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of baseline characteristics of included and excluded participants.

| Included (n=946) | Excluded (n=307) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (n) | Mean (SD) | % (n) | Mean (SD) | |

| Sex (% male) | 46.0 (435) | 56.4 (173)* | ||

| Race (% White) | 71.2 (674) | 68.7 (211) | ||

| Alcohol use characteristics a | ||||

| DSM-IV Status b | ||||

| Dependence | 16.1 (140) | 15.3 (42) | ||

| Abuse | 12.2 (106) | 16.1 (44) | ||

| Diagnostic orphan c | 40.5 (351) | 39.1 (107) | ||

| Non-problematic | 31.1 (270) | 29.6 (81) | ||

| Typical number of drinks/drinking day | 4.8 (2.6) | 5.2 (3.0)* | ||

| Past-year frequency of drinking | 50.8 (48.1) | 58.3 (54.7)* | ||

| Age first drank alcohol | 14.7 (2.3) | 14.6 (2.5) | ||

| Marijuana use characteristics d | ||||

| DSM-IV Status b | ||||

| Dependence | 9.2 (53) | 12.6 (22) | ||

| Abuse | 15.6 (90) | 9.2 (16) | ||

| Diagnostic orphan c | 12.5 (72) | 15.5 (27) | ||

| Non-problematic | 62.8 (363) | 62.6 (109) | ||

| Past-year frequency of use | 35.2 (64.2) | 47.5 (81.1)* | ||

| Age first used marijuana | 16.0 (1.5) | 15.9 (1.7) | ||

Denotes statistically significant difference between participants and non-participants (p<.05). Mean differences in alcohol frequency, alcohol quantity, and marijuana frequency became non-significant when sex was held constant.

Results based on 867 included and 288 excluded participants who were past-year alcohol users at baseline.

In the “excluded” column, cell counts for DSM-IV status do not sum to column totals due to missing data on individual DSM-IV items.

“Diagnostic orphan” refers to individuals endorsing 1 or 2 dependence criteria but not meeting the definition for abuse or dependence.

Results based on 578 included and 201 excluded participants who were past-year marijuana users at baseline.

2.3 Measures

2.3.1 Demographics

Sex was coded as observed by the interviewer at baseline. Age was self-reported at baseline, and confirmed using data from university administrative datasets, as allowed by participants’ informed consent. Self-reported data on race and mother’s education were also obtained from the university. Mother’s education was included as a proxy for socioeconomic status.

2.3.2 Substance Use Disorders

Participants were assessed annually for past-year abuse or dependence on alcohol and/or marijuana, using a series of questions adapted from the NSDUH questionnaire (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2003). Alcohol use behaviors were assessed first, followed by a separate series of questions on marijuana. Responses were then mapped to the corresponding criteria for abuse and dependence, as defined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV (DSM-IV) (American Psychiatric Association, 1994).

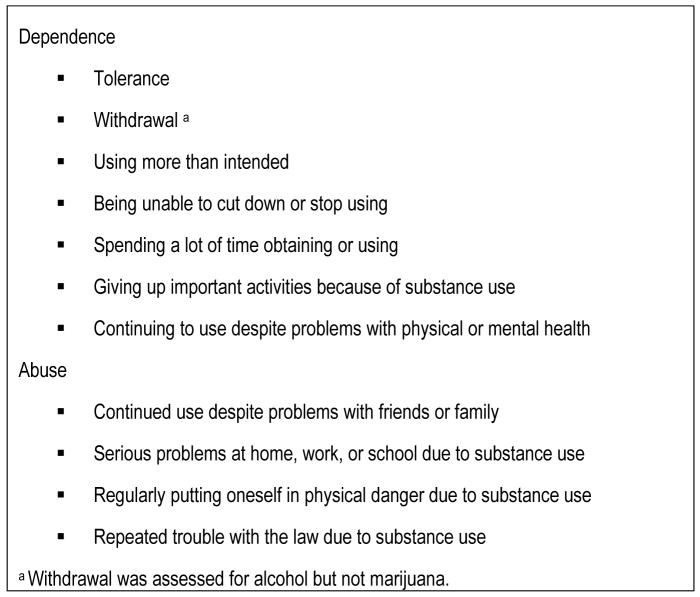

Figure 1 lists the DSM-IV criteria for dependence and abuse, as assessed in the present study. Alcohol dependence was defined by meeting three or more of the seven dependence criteria in the past 12 months; alcohol abuse was defined by the absence of dependence and the presence of one or more abuse criteria. Marijuana abuse and dependence were defined similarly, with the exception that only six possible criteria for marijuana dependence were available because withdrawal symptoms were not assessed.

Figure 1.

Criteria for substance abuse and dependence, based on DSM-IV guidelines.

To further characterize SUD in this sample, we examined the longitudinal patterns in meeting criteria for SUD. A binary variable was constructed based on whether SUD was persistent or intermittent. SUD cases were coded as “persistent” if criteria for SUD were met in all three years of the study. All other SUD cases were coded as “intermittent” (i.e., SUD was present in only one or two years). A separate categorical variable was coded to represent the year in which a SUD first presented, that is, year one, two, or three of the study.

2.3.3 Help-seeking, self-perceived need for help, and social pressures

As part of the third annual interview, which corresponded to participants’ third year in college, participants were asked about the presence of influences that might have motivated them to seek help or treatment for substance use problems since starting college. Because no existing scale for college students could be found, we adapted items from SAMHSA’s drug treatment needs assessment survey (McAuliffe et al., 1994) and the NSDUH (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2003). Questions were asked on a self-administered form, with assistance provided by the interviewer if necessary. All participants were encouraged to answer the questions, regardless of their level of drinking or drug involvement. Self-perceived need for help was assessed in the question, “At any time since starting college did you need any help or treatment for drug or alcohol use?” To assess the presence of any social pressures to obtain help or treatment, participants were asked whether anyone else thought they “needed help or treatment for drug or alcohol use,” with multiple response options of “parents,” “friends,” “police/courts (e.g., court-ordered treatment),” “university administrators,” and/or “someone else.” Participants were prompted to check all that applied, and to write in additional details if they checked “someone else.” Finally, to assess actual help-seeking, participants were asked, “At any time since starting college, did you take steps to obtain help or treatment?” Individuals who responded affirmatively were prompted to specify what kinds of steps they took to get help using open-ended responses.

2.3.4 Self-change behavior

Acknowledging that personal strategies for changing behavior play a significant role in the course of SUD, we computed a self-change behavior variable based on data from two of the DSM-IV criteria described above: attempts to cut down or stop using, and attempts to set limits on how much one consumes. Because the original questionnaire included separate questions ascertaining both attempts (i.e., “did you ever want to or try to cut down or stop using” and “did you ever try to set limits on how often or how much you would use”) and whether those attempts were successful (i.e., “were you able to cut down or stop using every time you wanted to or tried to” and “were you able to keep to the limits you set or did you often use more than you intended to”), we were able to create a three-level categorical variable indicating that either no attempts were made (0), attempts were made and were always successful (1), or attempts were made and were unsuccessful at least some of the time (2). This variable encompassed data on both alcohol and marijuana self-change behaviors from all three annual interviews.

2.4 Statistical Analysis

First, annual and three-year cumulative prevalence was computed for SUD overall and separately for alcohol use disorders and marijuana use disorders. Statistical weighting procedures were used to adjust for our purposive sampling strategies (Arria et al., 2008). At the time of sample selection, the sampling frame was stratified using screener data on sex, race (White, Black, Asian, Other), and illicit drug use before college (yes, no). Sampling weights were later computed within each sex-race-drug use cell as the number of individuals in the sampling frame divided by the number of individuals in the final cohort sample. Thus, prevalence was computed based on our high-risk sample of 946 individuals and weighted to represent 2,494 students in the target population, namely, the cohort of screened students who were incoming freshman in the fall of 2004. Therefore, although experienced drug users were purposively overrepresented, students with no drug use history had larger sampling weights, making the resulting prevalence estimates generalizable to the entire cohort of students entering the university in the fall of 2004.

To focus the remaining analyses on students with substance use problems, we restricted the sample to the 548 individuals who met criteria for SUD (involving alcohol and/or marijuana) at least once during the three years of the study. Within that subset, we computed the proportion who perceived a need for help with their substance use problems, experienced social pressures from someone else to obtain help, and/or took any steps to obtain help. Cross-tabulations were performed to: 1) observe any possible differences in self-perceived need and social pressures across demographic and SUD characteristics; and, 2) to examine differential help-seeking rates by self-perceived need, social pressures, demographics, and SUD characteristics. All comparisons were subjected to Chi-square goodness-of-fit tests for statistical significance, and evaluated at α=.05. Finally, for the subset of participants who did seek help, qualitative data on types of programs and services accessed were examined for emergent themes and coded accordingly.

3. Results

3.1 Prevalence of alcohol and marijuana SUD during the first three years of college

Table 2 presents the annual prevalence estimates for SUD for the three consecutive years of the study, and cumulative prevalence for the entire three-year period. Nearly half (46.8%wt) of all students in the cohort met criteria for SUD involving alcohol and/or marijuana at least once in the first three years of college. Note that all prevalence estimates were statistically weighted to approximate the actual prevalence within the general population of students who entered the university in the fall of 2004.

Table 2.

Annual and cumulative weighted prevalence of substance use disorders (SUD) involving alcohol and/or marijuana during the first three years of college.a

| SUD | Year 1 %wt | Year 2 %wt | Year 3 %wt | Cumulative %wt |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol Use Disorders | 19.3 | 26.5 | 30.9 | 44.0 |

| Marijuana Use Disorders | 9.3 | 12.8 | 14.2 | 19.2 |

| Any Substance Use Disorder (Alcohol or Marijuana) | 23.6 | 30.7 | 35.0 | 46.8 |

Results are presented as the weighted percent of participants, based on data from a high-risk sample of 946 individuals who provided complete data in all three years, and weighted to represent the general population of screened students in the target population (nwt=2,494).

3.2 Self-perceived need for help and social pressures to obtain help

Sample characteristics for the 548 individuals who ever met criteria for alcohol or marijuana SUD and completed all three interviews are presented in the first column of Table 3. As can be seen, approximately half (46.0%) of the 548 SUD cases were male, and 71.4% were White. In most cases, there was at least some recognition that they had a substance use problem, as indicated by the presence of self-change behaviors, either successful (36.3%) or unsuccessful (54.2%). However, recognition of a need for help or treatment was rare. Twenty individuals (3.6%) perceived that they needed help for their substance use problems, and 90 individuals (16.4% of SUD cases) were encouraged by someone else to seek help or treatment. Parents and friends were the most common sources of social pressure, yet only a small minority of SUD cases were ever encouraged by their parents (7.3%) or friends (6.9%) to seek help for a substance use problem (probably because of the other person’s lack of awareness of the student’s problem). At the bottom of Table 3, participants were categorized into four mutually exclusive groups: 72 individuals were encouraged by someone else to seek help for their substance use problems but did not themselves perceive a need for help, 18 individuals were encouraged by others and perceived a need, 2 individuals were not encouraged by others but did perceive a need, and the remaining 456 individuals neither were encouraged by others nor perceived a need. Although very few individuals ever perceived that they needed help (3.6%) this proportion was considerably higher among the 90 individuals who were encouraged by others to seek help (18/90=20.0%).

Table 3.

Comparison of self-perceived need for help, social pressures to obtain help for substance use disorders (SUD) involving alcohol and/or marijuana, and help-seeking, by demographic and SUD characteristics, among 548 individuals who met criteria for SUD during the first three years of college.

| Demographics & SUD Characteristics | Sample characteristics, all SUD cases % (n) | % who perceived a need for help themselves | % who were encouraged by someone else to seek help | % who took steps to obtain help or treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 100.0 (548) | 3.6 | 16.4 | 8.8 |

|

| ||||

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 48.0 (263) | 3.8 | 17.5 | 9.1 |

| Male | 52.0 (285) | 3.5 | 15.4 | 8.4 |

| Race | ||||

| Non-White | 23.5 (129) | 3.9 | 10.9 | 7.0 |

| White | 76.5 (419) | 3.6 | 18.1 | 9.3 |

| Mother’s education a | ||||

| High school or less | 15.9 (81) | 4.9 | 17.3 | 14.8 |

| Some college or technical | 9.2 (47) | 0.0 | 8.5 | 4.3 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 37.7 (192) | 3.6 | 17.2 | 8.9 |

| Graduate degree | 37.1 (189) | 3.7 | 18.5 | 6.9 |

| Substance(s) involved in SUD | ||||

| Alcohol only | 50.9 (279) | 3.6 | 14.7* | 7.9 |

| Alcohol and marijuana | 43.2 (237) | 4.2 | 20.3* | 11.0 |

| Marijuana only | 5.8 (32) | 0.0 | 3.1* | 0.0 |

| Persistence of SUD | ||||

| Alcohol | ||||

| Intermittent | 70.1 (384) | 1.7* | 10.4* | 8.6 |

| Persistent | 24.1 (132) | 5.0* | 20.8* | 11.4 |

| Marijuana | ||||

| Intermittent | 35.4 (194) | 3.4 | 14.8* | 8.8 |

| Persistent | 13.7 (75) | 5.3 | 24.2* | 12.0 |

| Type of SUD | ||||

| Not dependent | 42.2 (231) | 2.6 | 17.5 | 7.4 |

| Dependent | 57.8 (317) | 6.7 | 20.0 | 9.8 |

| Timing of SUD Onset | ||||

| First year | 55.5 (304) | 4.3 | 19.4 | 10.5 |

| Second year | 26.8 (147) | 2.0 | 15.0 | 6.8 |

| Third year | 17.7 (97) | 4.1 | 9.3 | 6.2 |

| Self-change behaviors (cutting back, setting limits) | ||||

| Never attempted | 9.5 (52) | 3.8 | 7.7 | 3.8 |

| Successfully attempted | 36.3 (199) | 2.0 | 10.6 | 8.0 |

| Unsuccessfully attempted | 54.2 (297) | 4.7 | 21.9* | 10.1 |

| Recognition of treatment need | ||||

| Self-perceived need | 3.6 (20) | -- | 90.0* | 90.0* |

| Social pressures (any) b | 16.4 (90) | 20.0* | -- | 45.6* |

| Parents | 7.3 (40) | 25.0* | -- | 32.5* |

| Friends | 6.9 (38) | 26.3* | -- | 34.2* |

| Police/courts | 2.4 (13) | 16.7* | -- | 100.0* |

| University administrators | 2.7 (15) | 13.3* | -- | 100.0* |

| Some other person c | 2.2 (12) | 33.3* | -- | 58.3* |

| Neither self nor anyone else | 83.2 (456) | -- | -- | 1.3* |

| Someone else but not self | 13.1 (72) | -- | -- | 33.3* |

| Self but no one else | 0.4 (2) | -- | -- | 50.0* |

| Both self and someone else | 3.3 (18) | -- | -- | 94.4* |

Response options for mother’s education do not sum to 548 due to missing data for that variable.

Response options for social pressures are not mutually exclusive; participants were allowed to check all responses that applied.

Other persons mentioned as having encouraged participants to obtain help were romantic partner (n=4), counselor/therapist (n=2), university resident assistant (n=1), sibling (n=1), coworker (n=1), and lawyer (n=1).

Denotes differences that are statistically significant at p<.05, as indicated by chi-square tests of independence.

--Denotes cells that were intentionally left blank because the result was redundant with the categories displayed (i.e., 0% or 100% was, by definition, the only possible result).

3.3 Comparison of self-perceived need and social pressures by demographic and SUD characteristics

The second and third columns of Table 3 illustrate that both self-perceived need and social pressures were present at similar levels across gender, race, and mother’s education. Self-perceived need remained low across all the comparisons tested, and the only statistically significant difference was that self-perceived need was slightly more common among individuals with persistent alcohol use disorder (5.0%) than individuals with intermittent alcohol use disorder (1.7%). However, social pressures differed in relation to SUD characteristics. For example, individuals whose SUD involved marijuana but not alcohol were the least likely to experience a social pressure (3.1%). By contrast, social pressure was significantly more prevalent among alcohol-only SUD cases (14.7%) and greater still among those whose SUD status derived from both marijuana and alcohol (20.3%). Moreover, individuals with persistent SUD were significantly more likely than intermittent SUD cases to experience social pressures, but social pressures were similar regardless of whether DSM-IV criteria for dependence (versus abuse) were satisfied. Significantly greater social pressures were also observed for individuals with unsuccessful self-change behavior (21.9%) relative to individuals who succeeded at self-change (10.6%).

3.4 Comparison of help-seeking rates

The fourth column of Table 3 presents the differential help-seeking rates by demographic and SUD characteristics, self-change behavior, self-perceived need, and social pressures. The overall sample prevalence of help-seeking was low (8.8%), with only 48 of the 548 individuals having sought help or treatment at some point since starting college. Help-seeking was remarkably similar across gender, race, and mother’s education. No help-seeking occurred among individuals whose SUD involved marijuana only, but help-seeking was somewhat higher among those with both alcohol- and marijuana-involved SUD (11.0%) relative to the alcohol-only SUD cases (7.9%). With respect to the severity of SUD, help-seeking was similar regardless of whether or not criteria were met for dependence or persistence, and no significant association between self-change behaviors and help-seeking was observed. Nearly all the individuals who perceived a need for help actually sought help (90.0%), but even in the absence of a self-perceived need, those who were encouraged by someone else to seek help were significantly more likely to have done so (33.3%), relative to their non-encouraged counterparts (1.3%). Not surprisingly, all of the individuals who experienced formal social pressures (i.e., from university or law enforcement personnel) had sought help, even though very few of them actually perceived a need for help. Help-seeking rates were also significantly elevated among individuals who experienced informal social pressures, regardless of whether they were from parents (32.5%), friends (34.2%), or another person (e.g., girlfriend/boyfriend, lawyer, coworker; 58.3%).

3.5 Types of resources accessed

Of the 48 participants who took any steps to obtain help or treatment, 37 provided qualitative information about what kinds of steps they took. These data were coded into themes, which are presented in Table 4. Themes were not mutually exclusive, and six individuals were coded for more than one help-seeking theme. The most frequently mentioned type of help was alcohol education, representing 38% of help-seekers. Alcohol education resources included both web-based and other types of classes. One in four (27%) help-seekers had consulted a health professional about their SUD, such as counselors, therapists, physicians, and the university health center. Roughly one in five (19%) participants seeking help entered twelve-step programs such as alcoholics anonymous or narcotics anonymous. It is noteworthy that one in five help-seekers (22%) mentioned a university program or staff member as a source of help. No one mentioned accessing a formal drug or alcohol treatment program.

Table 4.

Characteristics of resources accessed, among 48 individuals who sought any type of help or treatment for substance use disorders (SUD) involving alcohol and/or marijuana

| na | %b | |

|---|---|---|

| Type of resource | ||

| Education (Web-based or other class) | 14 | 38% |

| Professional provider (therapist, counselor, doctor) | 10 | 27% |

| Twelve-step program | 7 | 19% |

| Personal strategies (setting limits, willpower) | 6 | 16% |

| Other (taken to hospital, random drug testing, talked with residence hall director, nicotine gum) | 4 | 11% |

| Circumstances of help-seeking | ||

| Mandatory referral | 7 | 19% |

| Help was obtained from university programs and/or personnel | 8 | 22% |

|

| ||

| Missing data on what resources were accessed | 11 | -- |

Frequencies do not sum to 48 because multiple responses were permitted.

Percentages were computed based on the 37 cases with non-missing data on resources.

Interestingly, in response to the question on help-seeking, six participants described what appear to be personal strategies for self-change, such as using willpower, setting limits, finding new groups of friends, and making the decision to stop using. In four of the six cases, personal strategies were the only form of help-seeking mentioned. This observation, coupled with the substantial amount of missing qualitative data on what steps were taken to seek help (n=11), raise the possibility that our estimate of help-seeking might, in fact, be slightly inflated.

3.6 Post-hoc analysis of help-seeking predictors

To clarify the relative importance of the various correlates of help-seeking in this study, a series of three multiple logistic regression analyses were conducted with help-seeking as the binary dependent variable. The independent variables for each model were as follows: (1) sex, race, and dependence and persistence of SUD; (2) sex, race, self-perceived need for help, and a binary variable representing the presence or absence of at least one social pressure; (3) sex, race, dependence, persistence, self-perceived need, and social pressure. Results revealed no significant differences in help-seeking based on demographics or the two indicators of SUD severity. Self-perceived need (AOR=56.6; 95% CI=7.9, 402.9; p<.001) and social pressures (AOR=42.2; 95% CI=16.3, 109.1; p<.001) were both significantly predictive of help-seeking, even controlling for race, sex, dependence, and persistence.

4. Discussion

This study reports the prevalence of SUD involving alcohol and/or marijuana in a cohort of college students during their first three years of college (unweighted n=946). The weighted annual prevalence of SUD increased from 23.6%wt in the first year to 35.0%wt in the third year, with nearly half of all students (46.8%wt) meeting criteria for alcohol or marijuana SUD at least once during the first three years of college. Among SUD cases, the treatment gap was quite large: only 8.8% took steps to obtain help or treatment for their substance use problems. Moreover, the proportion seeking help was similar regardless of whether self-change behaviors had been attempted successfully (8.0%) or unsuccessfully (10.1%). In most cases (83.2%), there was no apparent recognition that they might need help with their substance use problems, either by the participant or by anyone else.

The present finding that only 8.8% of these SUD cases sought help or treatment is consistent with prior evidence of a large gap between treatment need and help-seeking among college students (Wu et al., 2007). However, evidence from the present study is mixed regarding the importance of SUD severity as a treatment motivator, as has been demonstrated in non-college populations (O’oole, Pollini, Ford, & Bigelow, 2006). Specifically, individuals with persistent SUD were significantly more likely than their intermittent-SUD counterparts to perceive a need for help and/or experience social pressures to obtain help, but no corresponding difference was observed for individuals who did or did not meet DSM-IV criteria for dependence (versus abuse). Moreover, neither of our indicators of SUD severity was significantly associated with help-seeking. Although the low overall prevalence of help-seeking in the sample made it difficult to examine the possible correlates of help-seeking, and our indicators of SUD severity were fairly simplistic, nevertheless we cannot rule out the possibility that severity of SUD might be less important as a determinant of help-seeking for college students than in the general population.

Based on the present finding that social pressures were rare, even among students meeting SUD criteria, it is tempting to attribute the treatment gap at least in part to a popular perception that binge drinking and recreational marijuana use are regarded as normative rites of passage, harmless, and integral to college life. This attitude might be contributing to delaying serious SUD problems from being identified and acknowledged as soon as possible. As others have observed (Wild, Roberts, & Cooper, 2002), we found that individuals who experienced social pressures to obtain treatment were significantly more likely to seek help than their non-pressured counterparts. This finding was consistent across each type of social pressure that was reported, including both informal pressures from friends and family and formal pressures from police and the university. Moreover, the presence of a self-perceived need for help almost never occurred in the absence of social pressures (0.4% of SUD cases). This finding raises the possibility that for many college students, social pressures might be a necessary step in the process of developing an internal awareness that their substance use might be escalating.

An important contribution of this study is the finding that the vast majority of students (96.4%) thought they did not need help or treatment for their alcohol or marijuana use even though they met DSM-IV criteria for SUD, and this proportion was similar even among students who had failed in their own attempts to change their substance use behaviors (95.3%). Of the 528 who did not personally think they needed help, only 5.7% (30) sought help. These results highlight the need to deepen our understanding of the help-seeking process of substance-abusing college students in order to facilitate early identification and intervention. A few prior studies have suggested that intervention during college can reduce problematic substance abuse among college students (Barnett et al., 2004; Borsari & Carey, 2005; Carey, Scott-Sheldon, Carey, & DeMartini, 2007; White et al., 2006), but utilization is still a major concern because, as demonstrated in this study, few students even seek help.

In this study, substantial differences were observed based on the type of substance involved in the SUD. Rates of all three outcomes (i.e., self-perceived need, social pressures, and help-seeking) were higher among individuals who met criteria for an alcohol use disorder; as compared with individuals whose SUD involved marijuana only. Although marijuana-only SUD was rare (i.e., only 5.8% of the SUD sample), this finding is intriguing and warrants further study. It is plausible that alcohol problems, relative to marijuana problems, might be more outwardly apparent to others, perhaps due to differences in the social contexts in which these two substances are consumed. It is also possible that there are differences in how students, peers, parents, and others perceive the seriousness and acceptability of alcohol problems relative to marijuana problems. These questions should be explored in future studies of college students given their high prevalence of marijuana use disorders (Caldeira et al., 2008).

Several limitations of this study must be acknowledged. First, help-seeking, social pressures, and perceived need were measured only once, and therefore our data might underestimate the true extent of these phenomena. Second, as with all cross-sectional analyses, we cannot address questions of causality with respect to any of the observed associations. Third, the findings are subject to recall bias because the data were collected via self-report and no corroborating evidence was gathered from friends, relatives or university administrators. Collecting corroborating evidence would be difficult given confidentiality concerns. Moreover, there is also the possibility of over-reporting of substance use or associated problems, as shown in previous studies of adolescents (Chen & Anthony, 2003). It is also important to note that, although the NSDUH-style questionnaire items are designed to correspond to the DSM-IV criteria for SUD, they are not equivalent to a clinical diagnosis; thus we cannot tell how many of our SUD cases might not have met the condition of “clinically significant impairment or distress” (American Psychiatric Association, 1994; p. 181) had they received a true clinical evaluation for SUD. Fourth, because the participants were recruited from only one university, the sample is not representative of other college populations and findings may not be generalizable to smaller academic institutions or universities in other geographic areas. Fifth, although we did not find clear evidence that our inclusion criteria biased the sample substantially, we acknowledge the possibility that our results on help-seeking might have been affected by a tendency for individuals with the most severe levels of substance use problems to decline to participate in follow-up assessments. Finally, detailed information was not gathered about the type of help sought by the students, the duration or the status of completion of the treatment. Future research should focus on understanding how college students perceive the treatment options available to them, the barriers they experience, and the relative effectiveness of various intervention methods.

The present study focused on social pressures and self-perceived need, but future studies of college students should investigate other important factors that might influence help-seeking. For example, it is possible that the presence of co-morbid mental health conditions might be related to earlier recognition of an emerging drug and alcohol problem, especially if the student has regular contact with a mental health professional. Also, students with a significant family history of drug or alcohol problems might experience both social pressures and self-perceived need differently. Because this study was largely descriptive, we recommend that future studies use larger samples to examine the temporality of the help-seeking process more fully. For example, one could model the statistical effect of informal social pressures on help-seeking both directly and indirectly via increasing self-perceived need. Given the present finding that social pressures were an important correlate of help-seeking, future studies should include more precise measures (e.g., number of times they were confronted by someone, number of different people who talked to them about getting help) to explore whether the association is linear or exhibits a ceiling effect.

Although this study focused on college-attending young adults, it is important to recognize that college students represent only one segment of the young-adult population, and substance-related problems are prevalent in this age group regardless of college attendance (White et al., 2005). Future studies of young adults not attending college are warranted to understand their help-seeking behaviors, perceptions of treatment need, and the social pressures they experience.

Based on the present findings and prior evidence of a wide treatment gap among college students (Wu et al., 2007), it is apparent that a need exists to revisit current policies regarding substance abuse treatment among college students. If college administrators are reluctant to set policies that make high-quality substance abuse and early intervention services on campus easily accessible, students with substance abuse problems might rely on sporadic visits to health care providers on visits home to their parents, or not receive intervention or treatment services at all. Broad-based implementation of screening and brief intervention, as recommended nearly 20 years ago by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) (Institute of Medicine Division of Neuroscience and Behavioral Health, 1990) remains one of the most promising strategies for college students, but has not yet been realized. Colleges could enact policies that enhance the availability and utilization of on-campus resources needed to provide SUD treatment for their students. Ideally, because the onset of substance use problems peak during this developmental period, it would make sense to provide a spectrum of services, from brief interventions to more intensive services, to prevent escalation of problems among students who are at high risk for developing SUD.

Although SUD is prevalent in college students (Caldeira et al., 2008; Harford, Hsiao, & Hilton, 2006; Slutske, 2005), these cases are typically in an early stage of development and therefore unlikely to access formal treatment services, as observed in the present study. Educational interventions have been shown to increase college students’ positive attitudes towards treatment (Yu, Evans, & Perfetti, 2003), and in this study, educational programs were the most common type of resource students accessed, although the actual number of students reached was quite small (14 out of 548 SUD cases). It is apparent from these data that a great opportunity exists to increase students’ access to the low-intensity types of interventions recommended by the IOM.

Future studies should explore the feasibility of innovative approaches such as making online confidential intervention assessment tools available to students. The online tools could focus on increasing awareness of susceptibility to SUD at the individual level, and help the student gauge the severity of his/her current problem. Since young adults ages 19 to 24 are the least likely age group to have health insurance (Roberts & Rhoades, 2008), electronic interventions may also remove the financial barrier that exists for some students who do not seek treatment even though they or others believe they need it.

In light of the strong correlation between social pressures and help-seeking, future research should explore effective ways of involving parents and peers in increasing help-seeking among college students. Unlike intervention methods widely used in the past, informal social pressures need not be applied in a manner that is highly confrontational or punitive (Tucker & King, 1999). If replicated, the present findings point to the possibility that, by talking openly with college students whose substance use might be a cause for concern, parents, peers, health providers, and other college personnel might succeed in encouraging more students to seek help, and at earlier stages, in order to mitigate longer-term problems.

Acknowledgments

The investigators would like to acknowledge funding from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01DA14845). Special thanks are given to Elizabeth Zarate, Laura Garnier, Gillian Pinchevsky, the interviewing team, and the participants.

References

- Agosti V, Levin FR. Predictors of treatment contact among individuals with cannabis dependence. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2004;30(1):121–127. doi: 10.1081/ada-120029869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV. 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ. Sensation seeking, aggressiveness, and adolescent reckless behavior. Personality and Individual Differences. 1996;20(6):693–702. [Google Scholar]

- Arria AM, Caldeira KM, O’Grady KE, Vincent KB, Fitzelle DB, Johnson EP, Wish ED. Drug exposure opportunities and use patterns among college students: Results of a longitudinal prospective cohort study. Substance Abuse. 2008;29(4):19–38. doi: 10.1080/08897070802418451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett NP, Tevyaw TOL, Fromme K, Borsari B, Carey KB, Corbin WR, et al. Brief alcohol interventions with mandated or adjudicated college students. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research. 2004;28(6):966–975. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000128231.97817.c7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blomqvist J. Treated and untreated recovery from alcohol misuse: Environmental influences and perceived reasons for change. Substance Use & Misuse. 1999;34(10):1371–1406. doi: 10.3109/10826089909029389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Carey KB. Two brief alcohol interventions for mandated college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2005;19(3):296–302. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.3.296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer TW. The development of risk-taking: A multi-perspective review. Developmental Review. 2006;26(3):291–345. [Google Scholar]

- Brennan PL, Moos RH, Mertens JR. Personal and environmental risk factors as predictors of alcohol use, depression, and treatment-seeking: A longitudinal analysis of late-life problem drinkers. Journal of Substance Abuse. 1994;6(2):191–208. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(94)90217-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill MA, Adinoff B, Hosig H, Muller K, Pulliam C. Motivation for treatment preceding and following a substance abuse program. Addictive Behaviors. 2003;28(1):67–79. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(01)00217-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldeira KM, Arria AM, O’Grady KE, Vincent KB, Wish ED. The occurrence of cannabis use disorders and other cannabis-related problems among first-year college students. Addictive Behaviors. 2008;33(3):397–411. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, Scott-Sheldon LAJ, Carey MP, DeMartini KS. Individual-level interventions to reduce college student drinking: A meta-analytic review. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32(11):2469–2494. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CY, Anthony JC. Possible age-associated bias in reporting of clinical features of drug dependence: Epidemiological evidence on adolescent-onset marijuana use. Addiction. 2003;98(1):71–82. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00237.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CY, O’Brien MS, Anthony JC. Who becomes cannabis dependent soon after onset of use? Epidemiological evidence from the United States: 2000–2001. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2005;79(1):11–22. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connors GJ, Donovan DM, DiClemente CC. Substance abuse treatment and the stages of change. New York: Guilford; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Donovan JE, Jessor R. Structure of problem behavior in adolescence and young adulthood. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53(6):890–904. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.6.890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillmore KM, Johnstone BM, Leino EV, Ager CR. A cross-study contextual analysis of effects from individual-level drinking and group-level drinking factors: A meta-analysis of multiple longitudinal studies from the Collaborative Alcohol-Related Longitudinal Project. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1993;54(1):37–47. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1993.54.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedberg EJ, Johnston WE. Outcome with alcoholics seeking treatment voluntarily or after confrontation by their employer. Journal of Occupational Medicine. 1980;22(2):83–86. doi: 10.1097/00043764-198002000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajema KJ, Knibbe RA. Social resources and alcohol-related losses as predictors of help seeking among male problem drinkers. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1999;60(1):120–129. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1999.60.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harford TC, Grant BF, Yi HY, Chen CM. Patterns of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence criteria among adolescents and adults: Results from the 2001 National Household Survey on Drug Abuse. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research. 2005;29(5):810–828. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000164381.67723.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harford TC, Hsiao Y, Hilton ME. Alcohol abuse and dependence in college and noncollege samples: A ten-year prospective follow-up in a national survey. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67(6):803–808. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartnoll R. Research and the help-seeking process. British Journal of Addiction. 1992;87(3):429–437. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1992.tb01943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilton ME. The demographic distribution of drinking problems in 1984. In: Clark WB, Hilton ME, editors. Alcohol in America: Drinking practices and problems. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press; 1991. pp. 87–101. [Google Scholar]

- Hingson R, Heeren T, Winter M, Wechsler H. Magnitude of alcohol-related mortality and morbidity among U.S. college students ages 18–24: Changes from 1998 to 2001. Annual Review of Public Health. 2005;26(1):259–279. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine Division of Neuroscience and Behavioral Health. Broadening the base of treatment for alcohol problems. Washington, D.C: National Academy Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Kaskutas LA, Weisner C, Caetano R. Predictors of help seeking among a longitudinal sample of the general population, 1984–1992. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1997;58(2):155–161. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Berglund PA, Caraveo-Anduaga JJ, DeWit DJ, Greenfield SF, et al. Patterns and predictors of treatment seeking after onset of a substance use disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2001;58(11):1065–1071. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.11.1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klag S, O’Callaghan F, Creed P. The use of legal coercion in the treatment of substance abusers: An overview and critical analysis of thirty years of research. Substance Use & Misuse. 2005;40(12):1777–1795. doi: 10.1080/10826080500260891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight JR, Wechsler H, Meichun K, Seibring M, Weitzman ER, Schuckit MA. Alcohol abuse and dependence among U.S. college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;63(3):263–270. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn D. Do cognitive changes accompany developments in the adolescent brain? Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2006;1(1):59–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6924.2006.t01-2-.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawental E, McLellan AT, Grissom GR, Brill P, O’Brien C. Coerced treatment for substance abuse problems detected through workplace urine surveillance: Is it effective? Journal of Substance Abuse. 1996;8(1):115–128. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(96)90127-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lennings CJ, Kenny DT, Nelson P. Substance use and treatment seeking in young offenders on community orders. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2006;31(4):425–432. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAuliffe WE, LaBrie N, Mulvaney N, Shaffer HJ, Geller S, Fournier EA, et al. Technical monograph. I. National Technical Center for Substance Abuse Needs Assessment; 1994. Assessment of substance abuse treatment needs: A telephone survey and questionnaire. [Google Scholar]

- O’Toole TP, Pollini RA, Ford DE, Bigelow G. Physical health as a motivator for substance abuse treatment among medically ill adults: Is it enough to keep them in treatment? Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2006;31:143–150. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope HG, Jr, Ionescu-Pioggia M, Pope KW. Drug use and life style among college undergraduates: A 30-year longitudinal study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158(9):1519–1521. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.9.1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts M, Rhoades JA. The Uninsured in America, 2007: Estimates for the U.S. Civilian Noninstitutionalized Population under Age 65. Statistical Brief #215. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satre DD, Knight BG, Dickson-Fuhrmann E, Jarvik LF. Predictors of alcohol-treatment seeking in a sample of older veterans in the GET SMART program. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2003;51(3):380–386. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt LA. Trends in access to addiction treatment, 1984–2004. Paper presented at the American Public Health Association.2007. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt LA, Weisner CM. Public health perspectives on access and need for substance abuse treatment. In: Tucker JA, Donovan DM, Marlatt GA, editors. Changing addictive behavior: Bridging clinical and public health strategies. New York: Guilford; 1999. pp. 67–96. [Google Scholar]

- Slutske WS. Alcohol use disorders among U.S. college students and their non-college-attending peers. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62(3):321–327. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storbjork J. The interplay between perceived self-choice and reported informal, formal, and legal pressures in treatment entry. Contemporary Drug Problems. 2006;33(4):611–643. [Google Scholar]

- Storbjork J, Room R. The two worlds of alcohol problems: Who is in treatment and who is not? Addiction Research and Theory. 2008;16(1):67–84. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. 2002 National Survey on Drug Use and Health Questionnaire. 2003 Retrieved September 26, 2006, from http://www.drugabusestatistics.samhsa.gov/nhsda/2k2MRB/2k2CAISpecs.pdf. [PubMed]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. College Enrollment Status and Past Year Illicit Drug Use among Young Adults: 2002, 2003, and 2004. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2005 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National findings (Office of Applied Studies, NSDUH Series H-30, DHHS Publication No. SMA 06–4194) 2006 Retrieved September 26, 2006, from http://www.oas.samhsa.gov/NSDUH/2k5nsduh/tabs/2k5Tabs.pdf.

- Tucker JA, King MP. Resolving alcohol and drug problems: Influences on addictive behavior change and help-seeking processes. In: Tucker JA, Donovan DM, Marlatt GA, editors. Changing addictive behavior: Bridging clinical and public health strategies. New York: Guilford; 1999. pp. 97–126. [Google Scholar]

- Varney SM, Rohsenow DJ, Dey AN, Myers MG, Zwick WR, Monti PM. Factors associated with help seeking and perceived dependence among cocaine users. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 1995;21(1):81–91. doi: 10.3109/00952999509095231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner BD, Leukefeld CG. Rural-urban differences in substance use and treatment utilization among prisoners. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2001;27(2):265–280. doi: 10.1081/ada-100103709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Lee JE, Kuo M, Lee H. College binge drinking in the 1990s-A continuing problem: Results of the Harvard School of Public Health 1999 College Alcohol Study. Journal of American College Health. 2000;48(5):199–210. doi: 10.1080/07448480009599305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Labouvie EW, Papadaratsakis V. Changes in substance use during the transition to adulthood: A comparison of college students and their noncollege age peers. Journal of Drug Issues. 2005;35(2):281–305. [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Morgan TJ, Pugh LA, Celinska K, Labouvie EW, Pandina RJ. Evaluating two brief substance-use interventions for mandated college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67(2):309–317. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wild TC, Roberts AB, Cooper EL. Compulsory substance abuse treatment: An overview of recent findings and issues. European Addiction Research. 2002;8(2):84–93. doi: 10.1159/000052059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L, Pilowsky DJ, Schlenger WE, Hasin D. Alcohol use disorders and the use of treatment services among college-age young adults. Psychiatric Services. 2007;58(2):192–200. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.58.2.192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J, Evans PC, Perfetti L. Attitudes toward seeking treatment among alcohol-using college students. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2003;29(3):671–690. doi: 10.1081/ada-120023464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]