Abstract

Objective

This study investigated the relationship between psychotropic medication use and adverse cardiovascular (CV) events in women with symptoms of myocardial ischemia undergoing coronary angiography.

Method

Women enrolled in the Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE), were classified into one of 4 groups according to their reported antidepressant and anxiolytic medication usage at study intake: (1) No medication (n=352); (2) Anxiolytics only (n=67); (3) Antidepressants only (n=58); and (4) Combined antidepressant and anxiolytics (n=39). Participants were followed prospectively for the development of adverse CV events (e.g., hospitalizations for nonfatal myocardial infarction, stroke, congestive heart failure, and unstable angina) or all cause mortality over a median of 5.9 years.

Results

Use of antidepressant medication was associated with subsequent CV events (HR= 2.16, 95% CI 1.21 to 3.93) and death (HR= 2.15, 95% CI 1.16 to 3.98) but baseline anxiolytic use alone did not predict subsequent CV events and death. In a final regression model that included demographics, depression and anxiety symptoms, and risk factors for cardiovascular disease, women in the combined medication group (i.e. antidepressants and anxiolytics) had higher risk for CV events (HR= 3.98, CI 1.74-9.10, p = .001 and all-cause mortality (HR=4.70, CI 1.7-12.97, p = .003) compared to those using neither medication. Kaplan Meier survival curves indicated that there was a significant difference in mortality among the four medication groups (p = .001).

Conclusions

These data suggest that factors related to psychotropic medication such as depression refractory to treatment, or medication use itself, are associated with adverse CV events in women with suspected myocardial ischemia.

Keywords: psychotropic medication, mortality, women, cardiovascular disease, antidepressants, depression, anxiety

Introduction

Depression is an independent risk factor for cardiac events in coronary artery disease (CAD) patients1, 2 and may increase cardiovascular (CV) risk in healthy populations 3. Anxiety may also be a CAD risk factor2. Therefore, studies have examined the efficacy of psychotropic medications, particularly selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI’s), in CAD patients with depressive symptoms.

Several randomized trials have demonstrated short term safety of SSRI’s in CAD patients. The CREATE study reported no 12-week increase risk of cardiovascular events for citalopram in CAD patients4. The SADHART study of patients with acute myocardial infarction (MI) or unstable angina, reported that sertraline, compared to placebo, did not affect left ventricular (LV) function, and other important CV parameters 5 over a 24 week period. In the ENRICHD trial6 of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) to reduce morbidity/mortality in CAD patients with depression and/or low social support, many patients in the study were treated with, but not randomly assigned to, SSRI’s. Secondary analysis of this data showed that SSRI use was associated with reduced nonfatal MI, and cardiac and all-cause mortality 7. Two other observational studies have also found fewer adverse CV effects in patients taking SSRI’s.

Use of tricyclic antidepressants (TCA) has been associated with increased risk of malignant ventricular arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death 8, 9. One retrospective study, 10 found that TCA use was associated with a dose-related increase in sudden cardiac death. Despite potential negative effects associated with many TCA’s, low doses of imipramine have been shown to be effective in treating patients with unexplained chest pain, and low TCA doses do not appear to be associated with increased risk11 .

Although causal relationships between antidepressant use and adverse CV events can only be made from randomized clinical trials, four other cohort studies are provocative 3, 12-14 in showing a positive association between antidepressant use and increased CV events and/or mortality in diverse populations of CAD patients,3, 14, 15 even after rigorous control for pre-existing depression. Most recently, in a cohort of over 63,000 women initially free of CAD, Whang et al. observed that antidepressant medication use with depression was associated with greater than 3-fold risk of sudden cardiac death and fatal CHD over a 3 ½ year follow-up period3.

The effects of anxiolytic medications in CAD patients have primarily been investigated in observational studies. In a 10 year follow-up of 500 men 16, anxiolytic and sedative medication use was associated with increased CV and all cause mortality. Another observational study 17, found that benzodiazepine use was associated with increased CV event risk. These studies did not statistically control for levels of anxiety or depression that could have been responsible for the observed increase in CV risk. Anxiety and depressive disorders commonly co-occur, and medication studies would be improved by jointly addressing both anxiolytic and antidepressant psychotropic treatments.

The issue of psychotropic medication use may be particularly relevant to women with CAD since psychotropic medication is more prevalent in women than men 18. However, previous examinations of use of psychotropics in CAD patients have been conducted in predominantly male samples. The Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE) is a National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute sponsored study designed to address ischemic heart disease diagnosis and mechanisms of ischemia in women with suspected CAD. The purpose of the present report is to describe the relationship between psychotropic medication use and adverse CV events in women undergoing coronary angiography for suspected myocardial ischemia. To rigorously account for confounding effects of prior symptoms, the present analyses control for levels of depression and anxiety and also control for prior depression treatment history. Because of the co-morbidity of anxiety and depressive disorders, the combined use of antidepressants and anxiolytic medications is often observed. Therefore, the present study also investigates associations of incident CV events with the combined, as well as individual use of these medications.

Methods

Participants were enrolled in the Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE) study, a collaborative study designed to optimize diagnostic evaluation and testing for ischemic heart disease in a cohort of 936 women, using a study design and methods previously published 19. To be enrolled in WISE, women had to be at least 18 years of age and be undergoing clinically-indicated coronary angiography. Exclusion criteria included: co-morbidity compromising one-year follow-up, pregnancy, contraindications to provocative diagnostic testing, cardiomyopathy, NYHA class IV congestive heart failure, recent myocardial infarction, significant valvular or congenital heart disease, and inability to complete questionnaires. The present study included 519 WISE participants both with and without angiographic CAD who had complete psychosocial data and psychotropic medication information.

The initial WISE visit consisted of a physical examination, medical history, and demographic, symptom, psychosocial assessment; all participants also underwent a coronary angiogram, subsequently analyzed by investigators blind to all WISE clinical data. Obstructive CAD was defined as the presence of ≥ 50% stenosis in ≥ 1 epicardial coronary artery, and a continuous CAD severity score was assessed, ranging from 5 to 88.5. Psychotropic medication usage was obtained from medication information collected during a baseline interview. Women were asked about treatment received within the last 6 weeks prior to study entry for (1) “antidepressants” and (2) “anxiolytics, sedatives, or hypnotics”. Response choices were “yes”, “no”, or “unknown”. Specific sub-classes of antidepressants or anxiolytics were not assessed. The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), a well-validated 21-item questionnaire was used to assess depressive symptomatology. Trait anxiety was assessed using the 10-item trait anxiety scale from the validated State Trait Personality Inventory. Higher scores on the BDI and the Trait Anxiety scale, indicate greater levels of depression and anxiety symptoms, respectively.

Follow-up for the occurrence of CV events was obtained by telephone interview at 6 weeks and yearly thereafter for occurrence of major cardiovascular events, including death due to CV or hospital stays for nonfatal myocardial infarction, stroke, or congestive heart failure. Deaths were verified via death certificate with cause blindly reviewed by an events committee. Median length of follow-up was 5.9 years. The primary outcome variables for this study were incidence of adverse CV events and all-cause mortality, which were examined separately. For the purposes of this study, women were classified into 4 groups according to their antidepressant and anxiolytic medication status during the week prior to intake: (1) No medication (n = 353); (2) Anxiolytics only (n= 68); (3) Antidepressants only (n=59); and (4) Combined antidepressants and anxiolytics (Combined medication; n= 39).

Variables are expressed as means ± standard deviations (SD) or as percentages. Group differences were assessed by non parametric Kruskal Wallis chi-square tests. Age-adjusted Cox regression analyses and stepwise Cox regression analyses were used to assess time to adverse CV events and all-cause mortality among the 4 medication groups. The no medication group was used as the reference category. Age-adjusted Kaplan Meier survival curves were plotted to examine the association of medication group with mortality and adverse CV events. The log rank test was used to compare survival between the medication groups. Criterion for significance was set at p < 0.05. Analyses were conducted using SAS version 8.2 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Demographic and Clinical Variables

Demographic and clinical characteristics for the 4 medication groups are presented in Table 1. Compared to women not taking medication, women in the combined medication groups were more likely to have ever smoked and to have a history of smoking, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and nonfatal MI. Women in the combined group also had greater depression and anxiety scores.

Table 1.

Demographic,Clinical Characteristics and CV Outcomes by Medication Group(N=519)

| No Medication (n=353) |

Anxiolytics Only (n=68) |

Antidepressants Only (n=59) |

Combined Medication (n=39) |

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yrs | 58.2 ± 11.2 | 57.1 ± 11.5 | 57.0 ± 10.4 | 55.5 ± 14.0 | .45 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29.2 ± 6.5 | 30.1 ± 6.9 | 28.9 ± 6.9 | 28.9 ± 5.1 | .70 |

| CAD severitya | 13.4 ± 13.4 | 16.0 ± 14.2 | 11.6 ± 9.5 | 12.6 ± 12.0 | .28 |

| Resting Heart Rate |

73.7 ± 11.8 | 72.3 ± 12.0 | 74.3 ± 15.8 | 71.7 ± 13.4 | .64 |

| BDI | 9 ± 7.1 | 11.3 ± 9.2 | 14.4 ± 9.6 | 15.6 ± 10.2 | <.001 |

| Trait Anxiety | 18.1 ± 5.3 | 19.9 ± 6.4 | 20.4 ± 6.4 | 22.5 ± 6.3 | <.001 |

| Ever Smoked | 167 (47%) | 41(60%) | 38 (64%) | 20 (51%) | .04 |

| Hx diabetes | 75 (21%) | 19(28%) | 17 (29%) | 9 (24%) | .42 |

| Hx hypertension |

190 (54%) | 45(66%) | 36 (61%) | 27 (69%) | .09 |

| Hx dyslipidemia |

173 (53%) | 34(52%) | 37 (63%) | 28 (74%) | .08 |

| Hx MI | 55 (16%) | 23(34%) | 11 (19%) | 11 (29%) | .003 |

| Current HRT | 134 (38%) | 28 (41%) | 33 (56%) | 18 (56%) | .02 |

| Total mortality | 25 (7.1%) | 6 (8.8%) | 8 (13.6%) | 7 (17.9%) | .07 |

| CVD events | 44 (12.5%) | 10 (14.7%) | 14 (23.7) | 13 (33.3%) | .002 |

CAD severity based on amount of stenosis, scores range from 0 – 100, higher scores indicate more severe stenosis; Values are means ± standard deviations or numbers of subjects (percentages). BMI=Body mass index; CAD = Coronary artery disease; HRT = Hormone replacement therapy; Hx = history of; MI = myocardial infarction; Tx = treatment.

Risk Factors and Psychotropic Medication

During the median follow-up of 5.9 years, there were a total of 81(15.6%) new CV events and 46 (8.8%) all-cause deaths. CV events (and percentage) and total mortality for each of the four medication groups are presented in Table 1. In unadjusted analyses, baseline use of antidepressant medication was associated with subsequent cardiovascular events (HR 2.16, 95% CI 1.21 to 3.93) and death (HR 2.15, 95% CI 1.16 to 3.98. The relationships between baseline anxiolytic use and subsequent cardiovascular events and death were not significant.

Risk factors, medical history variables, and the medication use categories were entered into multivariate analyses that also included initial depression and anxiety scores. In the full multivariate Cox regression model (Table 2), combined medication use was a significant predictor of both CVD events and mortality, even after adjusting for baseline BDI and STAI scores (p=0.001 and 0.003, respectively). Additional significant covariates for both CV events and total mortality were higher education, and CAD severity score, as well as a history of smoking, and diabetes history. Total mortality was related to age, CAD severity, smoking and diabetes history. In addition BDI scores were positively correlated with adverse CV events and total mortality (p=0.02 and p=0.01, respectively), and STAI scores were inversely related to CV events and total mortality (p=0.02 and 0.002, respectively).

Table 2.

Cox Regression Model for Risk Factors and CV Events and Mortality

| CVD events (n=81)* | All-Cause Mortality (n=46) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P value | HR | 95% CI | p value | |

| Antidepressants Only | 1.48 | (.67-3.26) | 0.33 | 1.21 | (0.42-3.48) | 0.71 |

| Anxiolytics Only | 1.41 | (0.67-2.94) | 0.36 | 1.05 | (0.36-3.0) | 0.94 |

| Combination Medication Use |

3.98 | (1.74-9.10) | 0.001 | 4.7 | (1.7-12.97) | 0.003 |

| Age, years | 0.99 | (0.97-1.02) | 0.42 | 1.03 | (.97-1.06) | 0.08 |

| Race | 1.28 | (0.67-2.44) | 0.46 | 1.26 | (0.53-2.98) | 0.59 |

| BMI | 0.98 | (0.93-1.02) | 0.27 | 0.94 | (0.87-1.01) | 0.09 |

| Marital Status | 0.72 | (0.42-1.23) | 0.23 | .94 | (0.45-1.94) | 0.87 |

| HS graduate | 2.10 | (1.13-3.92) | 0.02 | 2.40 | (1.07-5.4) | 0.03 |

| CAD Severity Score** |

2.10 | (1.43-3.09) | <0.001 | 2.08 | (1.25-3.46) | 0.005 |

| Hx Smoking | 2.96 | (1.61-5.43) | <0.001 | 3.22 | (1.43-7.27) | 0.005 |

| Hx Diabetes | 3.38 | (1.88-6.08) | <0.001 | 2.94 | (1.33-6.5) | 0.008 |

| Hx Hypertension | 1.22 | (0.64-2.32) | 0.55 | 1.45 | (0.59-3.57) | 0.42 |

| Hx nonfatal MI | 0.74 | (0.39-1.42) | 0.37 | 1.11 | (0.51-2.39) | 0.79 |

| Hx dyslipidemia | 1.42 | (0.78-2.57) | 0.25 | 0.92 | (0.43-1.95) | 0.82 |

| Current hormone therapy use |

1.18 | (0.69-2.04) | 0.54 | 1.11 | (0.54-2.27) | 0.77 |

| BDI | 1.05 | (1.00-1.09) | 0.02 | 1.07 | (1.01-1.14) | 0.01 |

| STAI | 0.93 | (0.87-.99) | 0.02 | 0.87 | (0.79-0.95) | 0.002 |

Includes stroke, congestive heart failure, myocardial infarction, or death with a cause rated as probably or definitely from CVD causes by an independent WISE study physician

CAD severity score was log transformed in this analysis

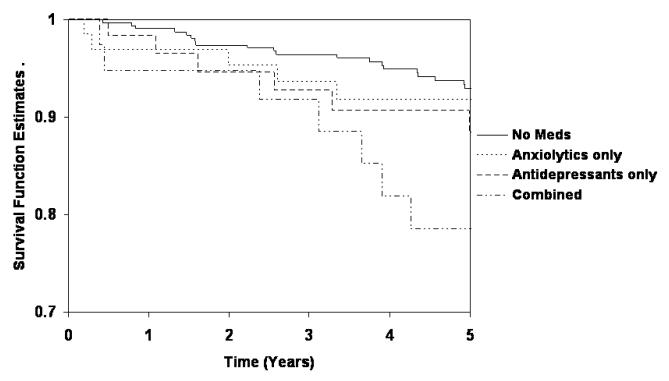

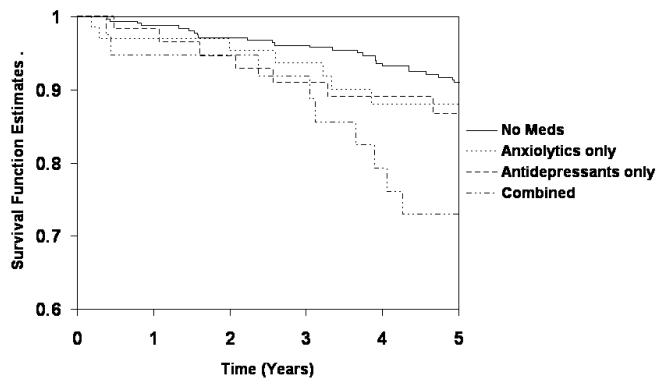

Age adjusted Kaplan-Meier survival analyses for all-cause mortality (See Figures 1-2) indicated a significant difference in mortality and CV events among the medication groups. In both models, the combined medication group experienced higher CV event rates compared to the no medication group (Log rank (Mantel Cox) test for all-cause mortality=6.9 (chi square, 1 df), p=.009; Log rank test for CV events=16.5 (chi square, 1 df), p<.001).

Figure 1.

Event-free survival curves for all cause mortality by medication group.

Figure 2.

Event-free survival curves for CV events by medication group.

In age adjusted regression models, combined medication use was associated with increased risk for CV events (HR 2.80, 95% CI 1.70 to 4.80) and all-cause mortality (HR 2.60 95% CI 1.40 to 5.00). The final multivariate Cox regression models presented in Table 2 indicate that the combined medication group had a higher risk for CV events (p = .001) and all-cause mortality (p = .003).

History of Depression Treatment

We also examined history of depression treatment as an additional covariate (with BDI scores remaining in the model), since it overlaps considerably with psychotropic medication use and has been associated with increased cardiovascular risk in WISE 20. Despite the shared variance between BDI scores and depression treatment history, when history of depression treatment was added as a covariate in the regression analyses, the relationship between combined medication use and adverse CV events was attenuated but remained statistically significant (HR=2.7, CI=1.10-6.90, p=0.04). However, all-cause mortality (HR=2.86, CI=0.82-9.96, p=0.10) was no longer significant.

Discussion

This is one of several prospective cohort studies to observe an association between psychotropic medication use and adverse CV outcomes in both patients with CAD and in an initially healthy population 3, 14, 15, 21. The study is unique, however, in demonstrating this relationship in a population of symptomatic women with suspected CAD, and these findings may be particularly relevant since psychotropic medication use is more prevalent in women than men 22 and these medications are frequently prescribed for women with chest pain and no angiographic evidence of CAD. Baseline use of antidepressant medication was associated with subsequent cardiovascular events and death in univariate analyses. Although we did not observe such a relationship with anxiolytics alone, in this cohort of women with suspected myocardial ischemia and CAD, in multivariate analyses, the often observed joint use of antidepressants and anxiolytics was associated with increased CV event and total mortality risk.

Prior studies of CAD patients have examined heart failure patients 14, CAD patients undergoing CABG 15 and predominantly male patients undergoing cardiac catheterization 23. The present study extends these observations to the important population of women with symptoms of ischemia and suspected CAD. Another recent study of more than 63,000 women enrolled in the Nurses Health Study also observed that reported antidepressant use (which included both SSRI’s and other antidepressants) in a population unselected for presence of coronary artery disease was prospectively associated with incidence sudden cardiac death, fatal MI, and nonfatal CHD events. 3

Although the present results are consistent with three additional long-term observational cohort studies; 3, 13, 24 these studies are in contrast to two short-term clinical trials of SSRI’s in depressed cardiac patients 5, 7 that did not demonstrate an association of these antidepressant medications with increased CV events. A post hoc analysis of clinical trial data found a beneficial relationship between SSRI use and cardiac outcomes. 4 The limitations and perils of drawing conclusions from observational studies as opposed to the definitive standard of clinical trials are well-known, and have been discussed in relation to studies of antidepressants and cardiac outcomes12. In addition, the present study only obtained data on medication use at study entry and it therefore cannot be determined whether patients are taking psychotropics at time of death or CVD event. Based on these observations, a definitive assessment of the effects of psychotropic medications on morbidity/mortality in women with suspected CAD and other CAD populations requires additional investigation.

Psychotropic medication use is likely a proxy for severity of psychiatric symptoms, treatment-refractory and/or residual depression in this sample, and/or other comorbidity, and has been used as such in prior research 3. Approximately 30% of the women were taking an anxiolytic, antidepressant, or both, in this study yet these patients remained with higher levels of symptomatology than women not taking medication. It has been previously demonstrated 25 that depression, and to a lesser extent anxiety 26, are independent risk factors for CV disease. In non-patient populations, dual diagnoses of generalized anxiety disorder and major depressive disorder may be associated with more significant impairment27. The possibility that depressive and anxiety symptoms may be linked to several of the same mechanisms involved in the development of CAD is currently under investigation, with some studies finding no evidence for a joint effect 2 while other results suggest that there may be a combined effect of anxiety and depression on cardiovascular outcomes28. Thus, there is a possibility that symptoms of depression and anxiety may be driving the elevated risk for adverse CV outcomes in these women, with the highest risk being evident in women taking both antidepressants and anxiolytic medications, and therefore those with more severe psychological disturbance. Supporting this possibility is a prior report from the WISE study 20 demonstrating that depressive symptoms and reported treatment history for depression are predictive of mortality. However, in our analyses we statistically accounted for symptomatology by including the BDI and anxiety measures as covariates. Risk for all-cause mortality and CV events was attenuated but remained significant for the combined medication group even after controlling for psychiatric symptoms. Adding history of depression treatment as an additional covariate similarly did not eliminate the effect of combined medications on adverse CV events, despite the fact that treatment history is itself a strong proxy variable for psychotropic medication use.

Study Limitations

A limitation of this study, as in other observational studies of antidepressant use and CAD outcomes, is that women with psychiatric symptoms were not randomly assigned to medication treatment. Further, medication usage was self-reported. Thus, causal relationship between psychotropic medications and CV events cannot be established. Only a randomized clinical trial of psychotropic medications adequately powered to detect adverse CV events can assess causal relationships and rule out confounding factors, such as severity of psychiatric symptoms. Another study limitation is the fact that the present medication assessments did not distinguish between SSRI and tricyclic antidepressants; although the latter are linked with possible adverse CV events, they may have been used for chest pain of unknown origin 11. Regardless of prescription pattern of particular antidepressant and anxiolytic medications in these women with suspected CAD, it is of note that those patients who were prescribed these medications were, for a variety of possible reasons, at increased risk of subsequent CV events. The present results were obtained after rigorous statistical controls for two indices of prior psychopathology—both depression and anxiety symptoms and also psychiatric treatment history. Despite these rigorous statistical controls, it is possible that the BDI and trait anxiety measures do not adequately capture the type of psychological distress typically experienced by patients with undiagnosed chest pain. For example, high rates of panic disorder29 are found in patients referred for cardiac workup, and panic and/or phobic anxiety may be related to increased cardiac death 26. Thus, controlling for symptoms such as trait anxiety and depressive symptoms may not be adequate, and treatment with psychotropic medications may not eliminate the increased risk in this sample associated with psychiatric symptoms.

Clinical Implications

The diagnosis of CAD in women presents particular challenges , and many women experience depression, anxiety, and impaired quality of life due to persistent symptoms30. Psychotropic medications may be prescribed for this these indications. The present data suggest that factors related to psychotropic medications, or medication use itself, are associated with increased CV events in women with suspected myocardial ischemia. It is unknown whether the depression and anxiety symptoms reported in this sample reflect under-treatment of psychiatric symptoms, a poor response to treatment, a treatment bias effect, or some other factor. Regardless, the persistence of psychiatric distress in women with chest pain and suspected ischemia needs to be addressed clinically. These symptoms are not only associated with elevated CV event risk but also with impaired psychological functioning 31 and significant economic burden 32 and therefore should be addressed clinically. Future research needs to focus on identifying relationships between use of psychotropic medications for depression and anxiety and adverse CV events in women with myocardial ischemia in prospective, controlled clinical trials.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by contracts from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institutes, nos. N01-HV-68161, N01-HV-68162, N01-HV-68163, N01-HV-68164, grants U0164829, U01 HL649141, U01 HL649241, T32HL69751, and grants from the Gustavus and Louis Pfeiffer Research Foundation, Danville, NJ, The Women’s Guild of Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA, The Ladies Hospital Aid Society of Western Pennsylvania, Pittsburgh, PA, and QMED, Inc., Laurence Harbor, NJ, the Edythe L. Broad Women’s Heart Research Fellowship, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, California, and the Barbra Streisand Women’s Cardiovascular Research and Education Program, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles.

The Corresponding Author has the right to grant on behalf of all authors and does grant on behalf of all authors, an exclusive license (or non exclusive for government employees) on a worldwide basis to the BMJ Publishing Group Ltd and its Licensees to permit this article (if accepted) to be published in HEART editions and any other BMJPGL products to exploit all subsidiary rights, as set out in our licence (http://heart.bmjjournals.com/ifora/licence.pdf).

Footnotes

The opinions and assertions expressed herein are those of the authors and are not to be construed as reflecting the views of the USUHS or the US Department of Defense.

References

- 1.Blumenthal JA, Lett HS, Babyak MA, White W, Smith PK, Mark DB, et al. Depression as a risk factor for mortality after coronary artery bypass surgery. Lancet. 2003;362(9384):604–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14190-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frasure-Smith N, Lesperance F. Depression and anxiety as predictors of 2-year cardiac events in patients with stable coronary artery disease. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(1):62–71. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2007.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Whang W, Kubzansky LD, Kawachi I, Rexrode KM, Kroenke CH, Glynn RJ, et al. Depression and risk of sudden cardiac death and coronary heart disease in women: results from the Nurses’ Health Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53(11):950–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.10.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lesperance F, Frasure-Smith N, Koszycki D, Laliberte MA, van Zyl LT, Baker B, et al. Effects of citalopram and interpersonal psychotherapy on depression in patients with coronary artery disease: the Canadian Cardiac Randomized Evaluation of Antidepressant and Psychotherapy Efficacy (CREATE) trial. JAMA. 2007;297(4):367–79. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.4.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glassman AH, O’Connor CM, Califf RM, Swedberg K, Schwartz P, Bigger JT, Jr., et al. Sertraline treatment of major depression in patients with acute MI or unstable angina. JAMA. 2002;288(6):701–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.6.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berkman LF, Blumenthal J, Burg M, Carney RM, Catellier D, Cowan MJ, et al. Effects of treating depression and low perceived social support on clinical events after myocardial infarction: the Enhancing Recovery in Coronary Heart Disease Patients (ENRICHD) Randomized Trial. JAMA. 2003;289(23):3106–16. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taylor CB, Youngblood ME, Catellier D, Veith RC, Carney RM, Burg MM, et al. Effects of antidepressant medication on morbidity and mortality in depressed patients after myocardial infarction. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(7):792–8. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.7.792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sala M, Coppa F, Cappucciati C, Brambilla P, d’Allio G, Caverzasi E, et al. Antidepressants: their effects on cardiac channels, QT prolongation and Torsade de Pointes. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2006;7(3):256–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bigger JT, Jr., Weld FM. Drugs and sudden cardiac death. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1982;382:229–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1982.tb55221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ray WA, Meredith S, Thapa PB, Hall K, Murray KT. Cyclic antidepressants and the risk of sudden cardiac death. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2004;75(3):234–41. doi: 10.1016/j.clpt.2003.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cannon RO, 3rd, Quyyumi AA, Mincemoyer R, Stine AM, Gracely RH, Smith WB, et al. Imipramine in patients with chest pain despite normal coronary angiograms. N Engl J Med. 1994;330(20):1411–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199405193302003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Narayan SM, Stein MB. Do depression or antidepressants increase cardiovascular mortality? The absence of proof might be more important than the proof of absence. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53(11):959–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roose SP, Glassman AH, Attia E, Woodring S, Giardina EG, Bigger JT., Jr. Cardiovascular effects of fluoxetine in depressed patients with heart disease. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155(5):660–5. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.5.660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sherwood A, Blumenthal JA, Trivedi R, Johnson KS, O’Connor CM, Adams KF, Jr., et al. Relationship of depression to death or hospitalization in patients with heart failure. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(4):367–73. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.4.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xiong GL, Jiang W, Clare R, Shaw LK, Smith PK, Mahaffey KW, et al. Prognosis of patients taking selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors before coronary artery bypass grafting. Am J Cardiol. 2006;98(1):42–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.01.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Merlo J, Hedblad B, Ogren M, Ranstam J, Ostergren PO, Ekedahl A, et al. Increased risk of ischaemic heart disease mortality in elderly men using anxiolytics-hypnotics and analgesics. Results of the 10-year follow-up of the prospective population study “Men born in 1914”, Malmo, Sweden. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1996;49(4):261–5. doi: 10.1007/BF00226325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lapane KL, Zierler S, Lasater TM, Barbour MM, Carleton R, Hume AL. Is the use of psychotropic drugs associated with increased risk of ischemic heart disease? Epidemiology. 1995;6(4):376–81. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199507000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paulose-Ram R, Safran MA, Jonas BS, Gu Q, Orwig D. Trends in psychotropic medication use among U.S. adults. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2007;16(5):560–70. doi: 10.1002/pds.1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Merz CN, Kelsey SF, Pepine CJ, Reichek N, Reis SE, Rogers WJ, et al. The Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE) study: protocol design, methodology and feasibility report. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;33(6):1453–61. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00082-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rutledge T, Reis SE, Olson MB, Owens J, Kelsey SF, Pepine CJ, et al. Depression symptom severity and reported treatment history in the prediction of cardiac risk in women with suspected myocardial ischemia: The NHLBI-sponsored WISE study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(8):874–80. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.8.874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Watkins L, Blumenthal J, Davidson J, McCants C, O’Connor C, Sketch M., Jr. Antidepressant use in coronary heart disease patients: Impact on survival. Psychosom Med. 2006;68(1):A95. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paulose-Ram R, Jonas BS, Orwig D, Safran MA. Prescription psychotropic medication use among the U.S. adult population: results from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988-1994. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57(3):309–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2003.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Watkins LLBJ, Davidson JR, McCants CB, O’Connor CM, Sketch MH., Jr. Antidepressant use in coronary heart disease patients: Impact on survival. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2006;68(1):A95. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sauer WH, Berlin JA, Kimmel SE. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2001;104(16):1894–8. doi: 10.1161/hc4101.097519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Agelink MW, Majewski TB, Andrich J, Mueck-Weymann M. Short-term effects of intravenous benzodiazepines on autonomic neurocardiac regulation in humans: a comparison between midazolam, diazepam, and lorazepam. Crit Care Med. 2002;30(5):997–1006. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200205000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kawachi I, Sparrow D, Vokonas PS, Weiss ST. Symptoms of anxiety and risk of coronary heart disease. The Normative Aging Study. Circulation. 1994;90(5):2225–9. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.90.5.2225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sherbourne CD, Wells KB. Course of depression in patients with comorbid anxiety disorders. J Affect Disord. 1997;43(3):245–50. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(97)01442-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Watkins LL, Blumenthal JA, Davidson JR, Babyak MA, McCants CB, Jr., Sketch MH., Jr. Phobic anxiety, depression, and risk of ventricular arrhythmias in patients with coronary heart disease. Psychosom Med. 2006;68(5):651–6. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000228342.53606.b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beitman BD, Mukerji V, Lamberti JW, Schmid L, DeRosear L, Kushner M, et al. Panic disorder in patients with chest pain and angiographically normal coronary arteries. Am J Cardiol. 1989;63(18):1399–403. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(89)91056-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johnson BD, Shaw LJ, Pepine CJ, Reis SE, Kelsey SF, Sopko G, et al. Persistent chest pain predicts cardiovascular events in women without obstructive coronary artery disease: results from the NIH-NHLBI-sponsored Women’s Ischaemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE) study. Eur Heart J. 2006;27(12):1408–15. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shaw LJ, Olson MB, Kip K, Kelsey SF, Johnson BD, Mark DB, et al. The value of estimated functional capacity in estimating outcome: results from the NHBLI-Sponsored Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE) Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47(3 Suppl):S36–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.03.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shaw LJ, Merz CN, Pepine CJ, Reis SE, Bittner V, Kip KE, et al. The economic burden of angina in women with suspected ischemic heart disease: results from the National Institutes of Health--National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute--sponsored Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation. Circulation. 2006;114(9):894–904. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.609990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]