Abstract

Two bacteriophages, DSS3Φ2 and EE36Φ1, which infect marine roseobacters Silicibacter pomeroyi DSS-3 and Sulfitobacter sp. EE-36, respectively, were isolated from Baltimore Inner Harbor water. These two roseophages resemble bacteriophage N4, a large, short-tailed phage infecting Escherichia coli K12, in terms of their morphology and genomic structure. The full genome sequences of DSS3Φ2 and EE36Φ1 reveal that their genome sizes are 74.6 and 73.3 kb, respectively, and they both contain a highly conserved N4-like DNA replication and transcription system. Both roseophages contain a large virion-encapsidated RNA polymerase gene (> 10 kb), which was first discovered in N4. DSS3Φ2 and EE36Φ1 also possess several genes (i.e. ribonucleotide reductase and thioredoxin) that are most similar to the genes in roseobacters. Overall, the two roseophages are highly closely related, and share 80–94% nucleotide sequence identity over 85% of their ORFs. This is the first report of N4-like phages infecting marine bacteria and the second report of N4-like phage since the discovery of phage N4 40 years ago. The finding of these two N4-like roseophages will allow us to further explore the specific phage–host interaction and evolution for this unique group of bacteriophages.

Introduction

The Roseobacter lineage in α-Proteobacteria comprises up to 25% of the bacterial community in seawater (Wagner-Döbler and Biebl, 2006). Roseobacters are diverse and ubiquitous in marine environments, and play an important role in marine biogeochemical cycles (Buchan et al., 2005; Wagner-Döbler and Biebl, 2006; Moran et al., 2007). Due to their ecological relevance, complete or draft genome sequences for more than 40 marine roseobacters are available (Brinkhoff et al., 2008). Recently, phage-like gene transfer agents (Lang and Beatty, 2007; Paul, 2008) and inducible prophages (Chen et al., 2006) have been found in Roseobacter genomes, indicating that virus-mediated gene transfer could be an important driving force for their genomic diversification and ecological adaptation.

Currently, only one lytic phage (SIO1), which infects a marine roseobacterium (Roseobacter sp. SIO67) has been reported (Rohwer et al., 2000). SIO1 is a T7-like podovirus containing the T7-like DNA replication genes and the genes involved in phosphate metabolism. To date, the vast majority of known marine podoviruses are the members of the T7 supergroup (i.e. P60, SIO1, P-SSP7, Syn5, S-CBP1, S-CBP2 and S-CBP3) (Rohwer et al., 2000; Chen and Lu, 2002; Sullivan et al., 2005; Pope et al., 2007; Wang and Chen, 2008), and they all contain a conserved DNA polymerase in their replication module (Wang and Chen, 2008).

Silicibacter pomeroyi DSS-3 and Sulfitobacter sp. EE-36 are among those roseobacters whose genomes have been sequenced. Both strains were isolated from Georgia coastal waters. Silicibacter pomeroyi DSS-3, the first roseobacterium with a sequenced genome, has been served as a model organism for studying the eco-physiological strategies of heterotrophic marine bacteria (Moran et al., 2004; Bürgmann et al., 2007). Sulfitobacter sp. EE-36 has a high inorganic sulfur oxidation activity and has been a model organism for studying sulfur cycle in coastal environments (Roseobase: http://www.roseobase.org/).

In a study undertaken to isolate bacteriophages from marine roseobacters, two novel phages (not seen in known marine phages) were isolated from S. pomeroyi DSS-3 and Sulfitobacter sp. EE-36 respectively. Here, we report the morphology, basic biology and genome sequences of these two newly discovered roseophages.

Results and discussion

Morphology and basic biology of DSS3Φ2 and EE36Φ1

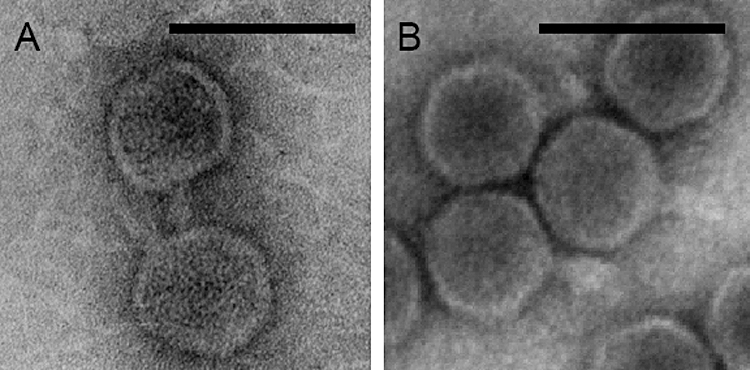

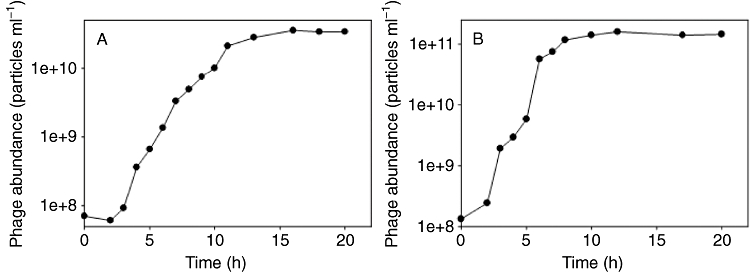

Phages DSS3Φ2 and EE36Φ1 were isolated from Baltimore Inner Harbor Pier V using an enrichment method. Both phages formed clear plaques. DSS3Φ2 produced large, clear plaques with irregular edges, while EE36Φ1 produced small, clear, round plaques. DSS3Φ2 and EE36Φ1 infected only S. pomeroyi DSS-3 and Sulfitobacter sp. EE-36, respectively, and did not cross-infect 13 other diverse marine Roseobacter strains (listed in the Experiment procedures). These two phages are morphologically similar to each other with icosahedral capsids (∼70 nm in diameter) and visible short tails (∼26 nm long) (Fig. 1). The capsids of DSS3Φ2 and EE36Φ1 are larger than those of T7-like podoviruses. The tails of DSS3Φ2 and EE36Φ1 are longer that those of T7-like podoviruses, but much shorter than those of typical myoviruses and siphoviruses. Morphologically, they resemble coliphage N4 (with a capsid size of ∼70 nm) (Kazmierczak and Rothman-Denes, 2006), a unique phage isolated from a sewage source in 1960s (Schito et al., 1967). The phage family Podoviridae currently consists of four genera (T7-like, Φ29-like, P22-like, N4-like), and phage N4 is the only member within N4-like genus (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ICTVdb/Ictv/index.htm). The infectivities of the DSS3Φ2 and EE36Φ1 were not affected by chloroform treatment (2%), indicating that neither of them is membrane-coated. Both phages had a prolonged lysis period. The latent periods of DSS3Φ2 and EE36Φ1 were about 3 and 2 h, respectively, followed by a gradual increase of released viral particles (Fig. 2A and B). It took about 15 and 10 h for DSS3Φ2 and EE36Φ1, respectively, to reach their growth plateaus and this resulted in the burst sizes approximately 350 and 1500 viral particles respectively. Delayed lysis and large burst size were also found in phage N4. A single N4-infected Escherichia coli produces c. 3000 viruses 3 h post infection (Schito, 1974). It is noteworthy that S. pomeroyi DSS-3 and Sulfitobacter sp.EE-36 grow nearly four times slower than E. coli, and this may partially explain the longer lysis period of these two roseophages compared with N4.

Fig. 1.

Transmission electron microscopy images of roseophages. (A) DSS3Φ2. (B) EE36Φ1. Scale bar = 100 nm.

Fig. 2.

One-step growth curves of roseophages. (A) DSS3Φ2. (B) EE36Φ1.

General genomic features of DSS3Φ2 and EE36Φ1

DSS3Φ2 and EE36Φ1 are linear, double-stranded DNA viruses. The genome sizes of DSS3Φ2 and EE36Φ1 are 74.6 and 73.3 kb, respectively, much larger than most known podoviruses, such as T7-like (37–46 kb), P22-like (39–50 kb) and Φ29-like (11–21 kb) podoviruses (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genomes/GenomesGroup.cgi?taxid=28883), but comparable to phage N4 (c. 70 kb, NCBI Accession No. EF056009). The G+C contents of DSS3Φ2 and EE36Φ1 genomes are 47.9% and 47.0%, respectively, higher than that of phage N4 (41%) but much lower than those of their hosts S. pomeroyi DSS-3 (64%) and Sulfitobacter sp. EE-36 (60%). A total of 81 open reading frames (ORFs) were identified in DSS3Φ2 and 79 ORFs were identified in EE36Φ1.

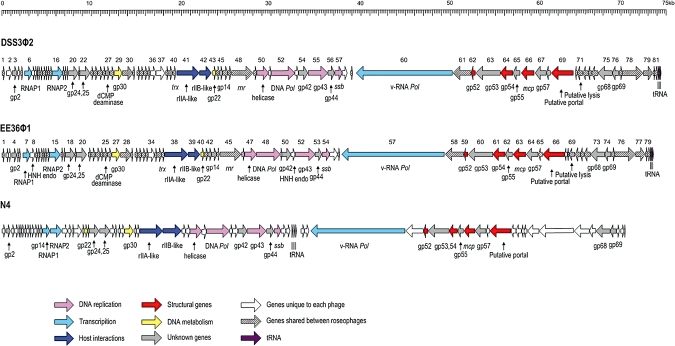

Despite their different host origin, the two roseophages share approximately 85% ORFs (70 ORFs) and have similar overall genome organization (Fig. 3). The ORFs shared between these two phages are 80–94% identical at the DNA level, and 83–98% identical at the amino acid level. The ORFs unique to each phage are mostly distributed on the left half side of their genomes (Fig. S1). Among all the identified ORFs, 26 ORFs from both roseophages are most closely related to genes from N4, with 26–57% amino acid identity, accounting for ca. 30% of both roseophages genomes (Table 1). Roseophages and N4 share DNA metabolism and replication genes, transcription genes, structural genes, host interaction genes and some additional genes without known function. DSS3Φ2 and EE36Φ1 also contain ORFs similar to genes from other types of phages and bacteria (Table 1), indicating the mosaic feature of the phage genomes. Approximately 40% of both roseophages ORFs have no matches in the database.

Fig. 3.

Genome organization and comparison of roseophages DSS3Φ2 and EE36Φ1 and coliphage N4. ORFs are depicted by leftward or rightward oriented arrows according to the direction of transcription. For comparison, the roseophage ORFs similar to N4 were named based on the N4 annotation.

Table 1.

Major predicted ORFs of roseophages DSS3Φ2 and EE36Φ1, the shaded ORFs are those similar to N4 genes.

| ORF no. | DSS3Φ2 (aa) | ORF no. | EE36Φ1 (aa) | Best hit | Potential function | % aa identity (similarity)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 156 | 4 | 172 | N4 gp2 | Unknown | 28 (43) |

| 6 | 260 | 7 | 260 | N4 gp15, RNA polymerase subunit 1 | Middle genes transcription | 39 (61) |

| 16 | 401 | 15 | 401 | N4 gp16, RNA polymerase subunit 2 | Middle genes transcription | 39 (52) |

| 20 | 398 | 18 | 398 | N4 gp24, putative ATPase, AAA superfamily | Unknown | 31 (49) |

| 22 | 393 | 20 | 388 | N4 gp25, hypothetical protein, vWFA Super-family | Unknown | 26 (43) |

| 23 | 92 | 21 | 92 | α-proteobacter Bradyrhizobium sp. ORS278, hypothetical protein | Unknown | 42 (63) |

| 27 | 142 | 25 | 142 | Bacteriophage Phi JL001 gp30, putative deoxycytidylate deaminase | DNA metabolism | 46 (60) |

| 28 | 142 | 26 | 143 | Mycobacterium phage Omega, gp174 | Unknown | 28 (51) |

| 29 | 282 | 27 | 293 | N4 gp30, putative thymidylate synthase | DNA metabolism | 39 (52) |

| 30 | 383 | 28 | 383 | Erwinia amylovora phage Era103, hypothetical protein g26 | Unknown | 27 (43) |

| 31 | 73 | 29 | 73 | Shewanella oneidensis MR-1, hypothetical protein SO_2678 | Unknown | 53 (65) |

| 32 | 110 | 30 | 110 | Roseobacter sp. AzwK-3b, hypothetical protein | Unknown | 34 (51) |

| 33 | 166 | 31 | 166 | Acidovorax avenae ssp. citrulli AAC00-1, hypothetical protein | Unknown | 36 (50) |

| 34 | 168 | 32 | 168 | Delftia acidovorans SPH-1, hypothetical protein | Unknown | 52 (69) |

| 40 | 105 | 37 | 105 | Paracoccus denitrificans PD1222, thioredoxin | DNA metabolism | 33 (64) |

| 41 | 862 | 38 | 860 | N4 gp33, rII A-like protein | Lysis inhibition | 35 (49) |

| 42 | 476 | 39 | 476 | N4 gp34, rII B-like protein | Lysis inhibition | 30 (48) |

| 43 | 102 | 40 | 102 | N4 gp22, putative homing endonuclease | DNA metabolism | 52 (69) |

| 45 | 129 | 42 | 129 | N4 gp14 | Unknown | 51 (65) |

| 46 | 181 | 43 | 182 | Azoarcus sp. EbN1, potential phage protein | Unknown | 43 (52) |

| 48 | 776 | 45 | 776 | Roseovarius sp. HT2601, ribonucleoside-diphosphate reductase | DNA metabolism | 56 (70) |

| 50 | 425 | 47 | 425 | N4 gp37, DNA helicase | DNA replication | 30 (53) |

| 52 | 876 | 48 | 876 | N4 gp39, DNA polymerase | DNA replication | 54 (70) |

| 44 (60) | ||||||

| 54 | 331 | 50 | 331 | N4 gp42 | Unknown | 44 (65) |

| 55 | 730 | 52 | 731 | N4 gp43 | DNA replication | 46 (66) |

| 56 | 244 | 53 | 244 | N4 gp44 | Unknown | 46 (66) |

| 57 | 277 | 54 | 277 | N4 gp45, DNA replication | Single-stranded DNA binding protein | 32 (48) |

| 60 | 3632 | 57 | 3786 | N4 gp50, virion-encapsulated RNA polymerase | Early genes transcription | 27 (46) |

| 61 | 666 | 58 | 672 | Roseobacter phage SIO1 gp24, C-Terminal partial sequence | Unknown | 41 (60) |

| 62 | 148 | 59 | 133 | N4 gp52, C-Terminal partial sequence | Structural gene | 40 (60) |

| 63 | 915 | 60 | 913 | N4 gp53 | Unknown | 29 (47) |

| 64 | 450 | 61 | 452 | N4 gp54 | Structural gene | 44 (61) |

| 65 | 251 | 62 | 249 | N4 gp55 | Unknown | 42 (61) |

| 66 | 482 | 63 | 482 | N4 gp56, major coat protein | Structural gene | 47 (63) |

| 67 | 447 | 64 | 448 | N4 gp57 | Unknown | 36 (57) |

| 69 | 800 | 66 | 800 | N4 gp59, putative portal gene | Structural gene | 45 (65) |

| 71 | 190 | 69 | 190 | Roseobacter sp. CCS2, hypothetical protein | Putative lysis gene | 47 (61) |

| 75 | 538 | 73 | 538 | N4 gp68 | Unknown | 57 (73) |

| 76 | 229 | 74 | 229 | N4 gp69 | Unknown | 42 (69) |

| 81 | 115 | 79 | 115 | E. coli SE11 hypothetical protein ECSE_1686 | Unknown | 39 (54) |

Most ORFs are similar between DSS3Φ2 and EE36Φ1, therefore only the best hits to DSS3Φ2 are listed here.

A large virion-encapsidated RNA polymerase gene

Strikingly, both DSS3Φ2 and EE36Φ1 contain a large ORF, which flanks more than 10 kb of phage genome (Table 1, Fig. 3). Those ORFs can be translated into 3632 aa and 3786 aa proteins for DSS3Φ2 and EE36Φ1, respectively, which match a 3500 aa virion-encapsidated RNA polymerase (vRNAP) in phage N4 (27% amino acid identity). Among all the known phages, N4 is the only one that contains this super large vRNAP gene (Falco et al., 1980). It is intriguing that these phages carry a conserved gene that makes up one-seventh of their genome. N4 vRNAP is responsible for early transcription (Falco et al., 1977) and DNA replication (Kazmierczak and Rothman-Denes, 2006). N4 vRNAP is packed in viral particles and injected into host cell upon infection (Falco et al., 1977; 1980). Similar to N4 vRNAP, the two roseophage vRNAPs do not contain any cysteine residues. The lack of cysteine residues could be important for v-RNAP to enter the host cells (Kazmierczak et al., 2002). Four conserved T7-like RNAP motifs (motifs T/DxxGR, A, B and C) and their catalytic residues (R424, K670, Y678, D559 and D951) described in N4 vRNAP (Kazmierczak et al., 2002) are also present in the two roseophages (Fig. S2), suggesting the similar function of vRNAP in DSS3Φ2, EE36Φ1 and N4. The advantage of a > 10 kb RNA polymerase gene to a phage is still not clear. However, it is interesting that this unique feature is conserved among the N4-like phages.

The two roseophages also encode two different RNA polymerase subunits (RNAP1 and RNAP2) which are similar to N4 RNAP1 and RNAP2. RNAP1 and RNAP2 constitute N4 RNA polymerase II (RNAP II) (Willis et al., 2002). RNAP II together with gp2, which also appears in roseophages, activates the transcription of N4 middle genes (Willis et al., 2002). In DSS3Φ2 and EE36Φ1, there are several small insertions (∼2 kb) between the RNAP1 and RNAP2 (Fig. 3). However, there is only a 47 bp gap between N4 RNAP1 and RNAP2. The presence of vRNAP and RNAP II in roseophages suggests that these two roseophages may use similar early and middle transcription machinery to that in N4.

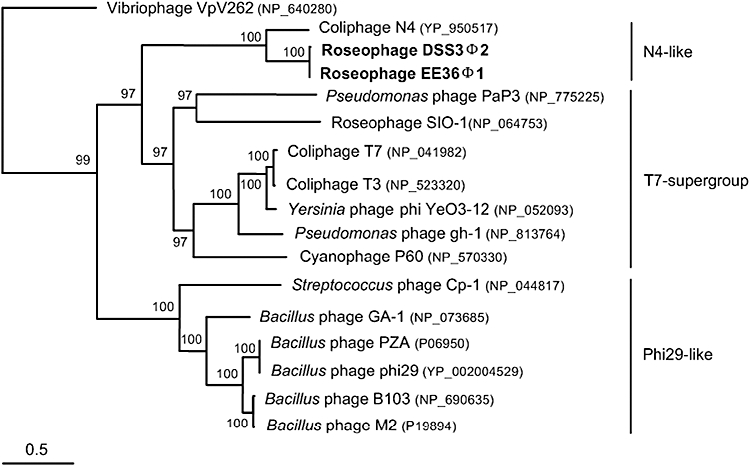

Conserved DNA replication module

Both DSS3Φ2 and EE36Φ1 possess the complete N4-like DNA replication system, including DNA helicase, DNA polymerase (DNA pol), single-stranded DNA binding protein (ssb), gp43 and vRNAP, and the relative gene order of these DNA replication genes is conserved among the two roseophages and N4 (Fig. 3). These genes are essential for in vivo N4 DNA replication (Kazmierczak and Rothman-Denes, 2006). The DNA pol genes of DSS3Φ2 and EE36Φ1 share high amino acid identity (53%) with N4 DNA pol (Table 1). DNA pol of the two roseophages and N4 all contain the DNA polymerase A domain and 3′-5′ exonuclease domain but lacks 5′-3′ exonuclease domain (Kazmierczak and Rothman-Denes, 2006). DNA pol gene phylogenetic analysis shows that DSS3Φ2 and EE36Φ1 are closely related to N4, but distantly related to T7 supergroup podoviruses (Fig. 4). When the N4-like DNA pol sequences were searched against the metagenomic databases, a limited amount of environmental sequences (11 hits) were obtained (Table 2). Interestingly, all the close hits were found in the nearshore GOS sites (i.e. harbors, basins, or mangrove-associated habitats), but not in the open ocean sites. In addition, we also searched the GOS database using other N4 like genes from DSS3Φ2 and EE36Φ1 genomes. Seventeen of 26 genes from these two roseophages could find homologous sequences in 13 GOS sites, resulting in a total of 96 N4-like environmental sequences (data not shown). Among these sequences, only two were found in the open ocean, and the rest 94 sequences were from coastal sites. These results suggest that N4-like roseophages are more abundant in the coastal waters than the open ocean water. It has been known that roseobacters are more abundant in the coastal water compared with the oceanic water (Buchan et al., 2005). Whether the geographic pattern of N4-like phages could be related to the distribution of roseobacters warrants further study.

Fig. 4.

Neighbour-joining tree constructed based on the aligned DNA pol amino acid sequences of 17 podoviruses. Phage VpV262 was used as an outgroup. The scale bar represents 0.5 fixed mutations per amino acid position. Bootstrap = 1000.

Table 2.

Homologues of N4-like DNA pol from GOS database.

| Location | Length (aa) | % aa identity (similarity) to N4 DNA pol | Temperature (°C) | E-value | CAMERA accession number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GS003 Browns Bank, Gulf of Maine (Coastal) | 241 | 43 (61) | 11.7 | 3e−40 | JCVI_PEP_1105101727847 |

| GS005 Bedford Basin, Nova Scotia (Coastal) | 292 | 44 (65) | 15 | 3e−63 | JCVI_PEP_1105130909873 |

| GS005 Bedford Basin, Nova Scotia (Coastal) | 331 | 29 (48) | 15 | 3e−33 | JCVI_PEP_1105128486423 |

| GS005 Bedford Basin, Nova Scotia (Coastal) | 361 | 29 (48) | 15 | 3e−33 | JCVI_PEP_1105132655935 |

| GS005 Bedford Basin, Nova Scotia (Coastal) | 323 | 31 (50) | 15 | 6e−31 | JCVI_PEP_1105124722171 |

| GS008 Newport Harbor, RI (Coastal) | 365 | 51 (71) | 9.4 | 2e−107 | JCVI_PEP_1105108615979 |

| GS008 Newport Harbor, RI (Coastal) | 291 | 61 (77) | 9.4 | 5e−93 | JCVI_PEP_1105142578775 |

| GS009 Block Island, NY (Coastal) | 135 | 58 (75) | 11 | 3e−29 | JCVI_PEP_1105118337801 |

| GS009 Block Island, NY (Coastal) | 203 | 51 (66) | 11 | 1e−45 | JCVI_PEP_1105120605863 |

| GS032 Mangrove on Isabella Island (Mangrove) | 302 | 52 (71) | 25.4 | 4e−77 | JCVI_PEP_1105137183151 |

| GS032 Mangrove on Isabella Island (Mangrove) | 223 | 59 (74) | 25.4 | 2e−68 | JCVI_PEP_1105112552903 |

Both roseophages possess a single-stranded DNA-binding protein (ssb) homologous to N4 ssb. N4 ssb belongs to a novel protein family and is involved in DNA replication, DNA recombination (Lindberg et al., 1989; Choi et al., 1995) and activation of E. coli RNA polymerase at late N4 transcription (Cho et al., 1995). The function of roseophages ssb genes is not clear. Previous research suggested that the single-stranded DNA binding activity and transcriptional activation of N4 ssb are separable, and the residues S260, K264 and K265 in the C-terminal of N4 ssb constitute part or all of an ‘activating region’ required for transcriptional activation, and were proposed to activating region (Miller et al., 1997). However, alignment of the amino acids of the ssb from roseophages and N4 shows that the C-terminal of roseophages ssb do not contain Lys residues at the end of polypeptide (Fig. S3). Moreover, the ssb residue Y75, which is essential for ssDNA binding activation in N4 was also not found in DSS3Φ2 and EE36Φ1. Further study on roseophages ssb could provide a better understanding on the function of these binding activity sites.

Roseophages contain host-related genes

Aside from the N4-like genes, DSS3Φ2 and EE36Φ1 also contain certain Roseobacter-related genes, suggesting that genetic exchange occurred between roseobacters and their phages. For examples, the roseophage ribonucleotide reductase (rnr) genes share the highest amino acid identity (56%) with nucleotide reductase from their Roseobacter hosts. The rnr phylogenetic analysis shows that DSS3Φ2 and EE36Φ1 cluster together with roseobacters (Fig. S4). Interestingly, N4 does not contain this rnr gene. The rnr converts ribonucleosides to deoxynucleotide, and is a key enzyme involved in DNA synthesis (Jordan and Reichard, 1998). The rnr gene is rarely seen in non-marine podoviruses, such as T7, T3 and P22. However, several podoviruses isolated from marine environments, such as SIO1, P60, P-SSP7 and syn5 contain rnr (Rohwer et al., 2000; Chen and Lu, 2002; Sullivan et al., 2005; Pope et al., 2007). Perhaps, obtaining sufficient free nucleotides for phage DNA synthesis is critical in the phosphorus-limited marine environment (Chen and Lu, 2002; Sullivan et al., 2005). Viral metagenomic analysis has shown that rnr is among the most abundant genes found in Sargasso Sea (Angly et al., 2006).

DSS3Φ2 and EE36Φ1 both contain a thioredoxin (trx) gene (105 aa) that shares high sequence homology with bacterial trx (Table 1). When binding with host thioredoxin, T7 DNA polymerase could increase its processing speed (Mark and Richardson, 1976; Huber et al., 1987). Thioredoxin has been found in other T7-like marine phage genomes (Rohwer et al., 2000; Chen and Lu, 2002; Pope et al., 2007) and appears to be a universal accessory cofactor of the replication module in these marine phages (Hardies et al., 2003). In contrast, neither coliphage N4 nor T7 contains trx. The finding of host-related thioredoxin in marine roseophages and other marine phages suggests that trx might be important to the phage survival in marine environments.

tRNA in roseophages

Using tRNA scan-SE, three tRNA genes were identified in both DSS3Φ2 and EE36Φ1 genomes (Table 3). DSS3Φ2 and EE36Φ1 both encode the tRNA gene CCA (Pro) and TCA (Ser). In hosts DSS-3 and EE-36, CCA and TCA are the rarest codons that code for Pro and Ser respectively. In contrast, CCA and TCA are abundant codes for Pro and Ser in phages DSS3Φ2 and EE36Φ1 (Table 3). It is possible that these two tRNAs are important for the roseophages during their translation stage (Bailly-Bechet et al., 2007). However, the reason for the presence of tRNA ATG (Met) in DSS3Φ2 and ATC (Ile) in EE36Φ1 is unclear.

Table 3.

Codon usage in phage DSS3Φ2, EE36Φ1 and their host strains (DSS-3 and EE-36), the codon in bold indicates the codon encoded by roseophages tRNAs.

| Usage frequency: per thousand (number) |

Usage frequency: per thousand (number) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Codon | Amino acid | DSS3Φ2 | DSS-3 | Codon | Amino acid | EE36Φ1 | EE-36a |

| CCT | Pro | 12.7 | 2.8 | CCT | Pro | 18.7 | 4.3 |

| CCC | Pro | 6.9 | 20.8 | CCC | Pro | 6.9 | 19.2 |

| CCA | Pro | 17.1 | 2.6 | CCA | Pro | 10.3 | 2.1 |

| CCG | Pro | 7.3 | 25.8 | CCG | Pro | 7.1 | 26.7 |

| TCT | Ser | 22.8 | 2.1 | TCT | Ser | 19.6 | 0 |

| TCC | Ser | 15.8 | 8.2 | TCC | Ser | 8.0 | 4.3 |

| TCA | Ser | 25.8 | 1.8 | TCA | Ser | 11.4 | 0 |

| TCG | Ser | 16.5 | 20.1 | TCG | Ser | 8.2 | 12.8 |

| ATG | Met | 26.6 | 27.5 | ATT ATCATA | Ile Ile Ile | 22.5 32.4 1.4 | 9.6 52.4 0 |

Analysed based on one contig for EE-36.

DNA metabolism genes

Both roseophages encode a putative deoxycytidylate deaminase (dCMP deaminase) gene, which is most similar to the dCMP deaminase in phage Phi JL001 (Lohr et al., 2005) (Table 1). Deoxycytidylate deaminase catalyses the dCMP to dUMP. The roseophages also code for putative thymidylate synthase (thyX) protein, which generates thymidine monophosphate (dTMP) from deoxyuridine monophosphate (dUMP). Both roseophages encode a putative HNH endonuclease homologous to N4 gp22 (ORF 43 in DSS3Φ2, and ORF40 in EE36Φ1). Compared with DSS3Φ2, EE36Φ1 encodes two additional endonucleases (ORF 8 and ORF 51) (Table 1, Fig. 3).

Lysis gene

It is noteworthy that homologue of N4 lysis gene, a new family of murein hydrolase (Stojković and Rothman-Denes, 2007), was not detected in DSS3Φ2 or EE36Φ1 genomes. However, a hypothetical protein (190 aa, ORF 71 in DSS3Φ2 and ORF 69 in EE36Φ1) located in the late region of DSS3Φ2 and EE36Φ1 genomes likely act as a lysis gene because this protein is similar to a lytic enzyme found in roseobacterium Sagittula stellata E-37 (37% amino acid identity).

Structural genes

Four structural genes are shared between roseophages and N4 (Table 1, Fig. 3). Both DSS3Φ2 and EE36Φ1 encode the major capsid protein (mcp) and putative phage portal gene, which are similar to their N4 counterparts (Table 1). The homologues of N4 structural genes gp52 and gp54 were also identified in the roseophages (Choi et al., 2008).

Conclusions

Phage N4 has been studied for 40 years without a comparable system. The genome sequences of DSS3Φ2 and EE36Φ1 reveal a close relationship between coliphage N4 and these two roseophages. Discovery of the two N4-like marine phages serves as a good reference system for further understanding of phage biology and evolution. The two podovirus-like roseophages are distantly related to all the known marine podoviruses. DSS3Φ2 and EE36Φ1 are warranted to investigate the ecological role of N4-like phage on marine roseobacters.

Experimental procedures

Roseobacter strains

Silicibacter pomeroyi DSS-3 and Sulfitobacter sp. EE-36 were kindly provided by Dr M.A. Moran at the University of Georgia. Bacterial strains were grown in YTSS medium (4 g l−1 yeast extract, 2.5 g l−1 tryptone, 20 g l−1 Crystal Sea) at 28°C.

Isolation of roseophages

Water samples were collected from Baltimore Inner Harbor Pier V on 24 January 2007, and immediately filtered through 0.22 μm polycarbonate membrane filters (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA). Filtrate of 100 ml was added to 150 ml of exponentially growing bacterial cultures and incubated overnight. Cultures were then centrifuged at 10 000 g for 20 min to remove bacterial cells. Cell-free lysates of 10–100 μl were added into 1 ml of exponentially growing cultures, and plated using plaque assay according to a protocol described elsewhere (Suttle and Chen, 1992). Each phage isolate was purified at least three times by plaque assay.

Transmission electron microscopy

One drop of purified roseophage particles was adsorbed to the 200-mesh Formvar/carbon-coated copper grid for several minutes and then the grids were stained with 0.5% aqueous uranyl acetate for c. 30 s. Samples were examined with a Zeiss CEM902 transmission electron microscope operated at 80 kV (University of Delaware, Newark). Images were taken using a Megaview II digital camera (Soft Imaging System, Lakewood, CO).

Cross-infection

The cross-infectivities of roseophages were tested against other marine Roseobacter strains. The 13 tested Roseobacter strains are Roseovarius nubinhibens ISM, Sulfitobacter 1921, Roseobacter sp. TM1038, Silicibacter sp. TM1040, Roseobacter sp. TM1039, Roseovarius sp. TM1042, Phaeobacter 27–4, Roseobacter denitrificans ATCC 33942, Roseobacter litoralis ATCC 49566, Sulfitobacter strain CHSB4, JL351, T11, and CBB406. Strains DSS-3, EE-36 and ISM were provided by M.A. Moran, while strains TM1038, TM1039, TM1040, TM1042, Phaeobacter strain 27-4, Roseobacter denitrificans ATCC 33942, and Roseobacter litoralis ATCC 49566 were provided by R. Belas at University of Maryland Biotechnology Institute (UMBI). The remaining strains were isolated in our laboratories. Exponentially growing cultures of these bacteria strains were incubated with roseophage lysates for 30 min and then plated using plaque assay.

Growth curve experiments

Exponentially growing cultures of S. pomeroyi DSS-3 and Sulfitobacter sp. EE-36 (100 ml) were inoculated with the DSS3Φ2 and EE36 Φ1 at a multiplicity of infection (moi) of 0.1. After inoculation, an aliquot of the cell suspension was collected from each culture every 1 h for 20 h, and the numbers of DSS3Φ2 and EE36 Φ1 were determined by epifluorescence microscopic count method (Chen et al., 2001).

Preparation of roseophage DNA

Each phage was added into a 500 ml host culture (OD600 = 0.1∼0.2) with moi of 3, and incubated overnight. Phage lysates (1010−1011 phage particles ml−1) was mixed with 10 ml chloroform (2% v/v) and 20 g NaCl, and left on ice for 30 min before the cell debris was pelleted by centrifugation at 10 000 g for 30 min. The supernatant was mixed well with polyethylene glycol 8000 to a final concentration of 10% (w/v) and incubated overnight at 4°C. The phage particles were precipitated by centrifugation at 15 000 g for 30 min and then re-suspended in 10 ml of TM buffer (Tris-HCl 20 mM, MgSO4 10 mM, pH 7.4). Polyethylene Glycol-concentrated phage lysates were overlaid onto a 10–50% iodixanol (OptiPrep, Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA) gradient, and centrifuged for 2 h at 200 000 g, using a T-8100 rotor in a Sorvall Discovery 100S centrifuge. The visible viral band was extracted using a 18-gauge needle syringe and then dialysed twice in TM buffer overnight at 4°C. Purified phages were stored at 4°C in the dark. Phage DNA was extracted using the method described previously (Sambrook and Russell, 2001).

Genome sequencing and analysis

To prepare DNA template for genome sequencing, purified phage DNA was amplified using Genomiphi V2 kit (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ, USA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The initial sequence segments were obtained by random PCR amplification of phage DNA using degenerate primer RP-1 (5′-ATHGAYGGNGAYATHCAY-3′) and RP-2 (5′-YTCRTCRTGNACCCANGC-3′). The PCR was performed in 50 μl volume containing 1× reaction buffer (Genescript, Scotch Plains, NJ, USA) with 1.5 mM MgCl2, 100 μM of dNTPs, 50 pmol of each primer, 1 U Taq DNA polymerase (Genescript) and 10 ng phage DNA as templates. PCR program consists of an initial denaturing at 94°C for 2 min, followed by 30 cycles of denaturing at 94°C for 30 s, annealing at 48°C for 1 min and extension at 72°C for 1 min and a final extension at 72°C for 10 min. Multiple PCR amplicons could be obtained for both phages. The most dominant bands for each phage were excised and the DNAs were purified using gel purification kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) and sequenced bi-directionally using the same primer set. The three fragments with unambiguous sequences are used as starting templates for primer walking. All the subsequent primer walking was done by using an automated sequencer ABI 310 (PE Applied Biosystems) in the Biological and Analytical Laboratory at the Center of Marine Biotechnology, UMBI. From each primer walking, unambiguous sequences were assembled together using AssemblyLIGN program (GCG, Madison). Open reading frames were predicted by using ORF Finder (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gorf/gorf.html) and GeneMarkS (Besemer and Borodovsky, 1999). Translated ORFs were compared with known protein sequences using blastp (Altschul et al., 1990). tRNA sequences were searched by using tRNAscan-SE (Lowe and Eddy, 1997). The countcodon program was used to determine codon usage (http://www.kazusa.or.jp/codon/countcodon.html).

Sequences alignment and phylogenetic analysis were performed using MacVector 7.2 program (GCG, Madison, WI). Jukes–Cantor distance matrix analysis was used to calculate the distances from the aligned sequences, and the neighbour-joining method was used to construct the phylogenetic tree.

GOS database search

The amino acid sequence of N4-like DNA pol gene was searched against the GOS metagenomic database using blastp (Seshadri et al., 2007) (E-value < 10−20). The blast homologues of the DNA pol gene were then searched against the NCBI database, only the sequences closely related to N4 DNA pol were retained and other sequences closer to the bacterial DNA pol were not included.

Nucleotide sequence accession number

The GenBank accession numbers assigned to the complete DSS3Φ2 and EE36Φ1 genomes are FJ591093 and FJ591094 respectively.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge funding support from the National Science Foundation's Microbial Observatories Program (MCB-0132070, MCB-0238515, MCB-0537041 to F.C.), and the funds from the Xiamen University 111 program to F.C. and 2007CB815904 to N.Z.J. We thank Dr. Russell Hill for comments and English editing.

Supporting information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article:

Fig. S1. Genome comparison of DSS3Φ2 and EE36Φ1. Red arrow: DSS3Φ2 unique ORF, blue arrow: EE36Φ1 unique ORF, white arrow: shared ORF.

Fig. S2. Amino acid sequence alignment of four Motifs (T/DxxGR, A, B and C) between N4-like phages v-RNAPs and other T-7 supergroup podoviruses RNAPs. Residues that highlighted in red are identical in all these phages, Residues that highlighted in yellow are > 50% identical. The arrows indicate the conserved catalytic residues.

Fig. S3. Amino acid sequence comparison of Roseophage ssb gene and N4 ssb gene. The arrows indicate the catalytic residues in N4.

Fig. S4. Neighbour-joining tree constructed based on the aligned rnr family amino acid sequences. Sequences from DSS3Φ2 and EE36Φ1 are shown in bold. The scale bar represents 0.1 fixed mutations per amino acid position. Bootstrap = 1000.

Please note: Wiley-Blackwell are not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

References

- Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angly FE, Felts B, Breitbart M, Salamon P, Edwards RA, Carlson C, et al. The marine viromes of four oceanic regions. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e368. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailly-Bechet M, Vergassola M, Rocha E. Causes for the intriguing presence of tRNAs in phages. Genome Res. 2007;17:1486–1495. doi: 10.1101/gr.6649807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besemer J, Borodovsky M. Heuristic approach to deriving models for gene finding. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:3911–3920. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.19.3911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkhoff T, Giebel HA, Simon M. Diversity, ecology, and genomics of the Roseobacter clade: a short overview. Arch Microbiol. 2008;189:531–539. doi: 10.1007/s00203-008-0353-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchan A, Gonzáléz JM, Moran MA. Overview of the marine Roseobacter lineage. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:5665–5677. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.10.5665-5677.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bürgmann H, Howard EC, Ye W, Sun F, Sun S, Napierala S, et al. Transcriptional response of Silicibacter pomeroyi DSS-3 to dimethylsulfoniopropionate (DMSP) Environ Microbiol. 2007;9:2742–2755. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2007.01386.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen F, Lu JR. Genomic sequence and evolution of marine cyanophage P60: a new insight on lytic and lysogenic phages. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2002;68:2589–2594. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.5.2589-2594.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen F, Lu JR, Binder B, Liu YC, Hodson RE. Application of digital image analysis and flow cytometry to enumerate marine viruses stained with SYBR gold. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001;67:539–545. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.2.539-545.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen F, Wang K, Stewart J, Belas R. Induction of multiple prophages from a marine bacterium: a genomic approach. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:4995–5001. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00056-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho NY, Choi M, Rothman-Denes LB. The bacteriophage N4-coded single-stranded DNA-binding Protein (N4SSB) is the transcriptional activator of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase at N4 late promoters. J Mol Biol. 1995;246:461–471. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.0098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi KH, McPartland J, Kaganman I, Bowman VD, Rothman-Denes LB, Rossmann MG. Insight into DNA and protein transport in double-stranded DNA viruses: the structure of bacteriophage N4. J Mol Biol. 2008;378:726–736. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.02.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi M, Miller A, Cho NY, Rothman-Denes LB. Identification, cloning and characterization of the bacteriophage N4 gene encoding the single-stranded DNA-binding protein. A protein required for phage replication, recombination, and late transcription. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:22541–22547. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.38.22541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falco SC, Laan KV, Rothman-Denes LB. Virion-associated RNA polymerase required for bacteriophage N4 development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:520–523. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.2.520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falco SC, Zehring W, Rothman-Denes LB. DNA-dependent RNA polymerase from bacteriophage N4 virions. J Biol Chem. 1980;255:4339–4347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardies SC, Comeau AM, Serwer P, Suttle CA. The complete sequence of marine bacteriophage VpV262 infecting Vibrio parahaemolyticus indicates that an ancestral component of a T7 viral supergroup is widespread in the marine environment. Virology. 2003;310:359–371. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6822(03)00172-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber HE, Tabor S, Richardson CC. Escherichia coli thioredoxin stabilizes complexes of bacteriophage T7 DNA polymerase and primed templates. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:16224–16232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan A, Reichard P. Ribonucleotide reductases. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:71–98. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazmierczak KM, Rothman-Denes LB. In: The Bacteriophages. Calender R, editor. New York, USA: Oxford University Press US; 2006. pp. 302–314. [Google Scholar]

- Kazmierczak KM, Davydova EK, Mustaev AA, Rothman-Denes LB. The phage N4 virion RNA polymerase catalytic domain is related to single-subunit RNA polymerases. EMBO J. 2002;21:5815–5823. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang AS, Beatty JT. Importance of widespread gene transfer agent genes in alpha-proteobacteria. Trends Microbiol. 2007;15:54–62. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2006.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindberg GJ, Kowalczykowski SC, Rist JK, Sugino A, Rothman-Denes LB. Purification and characterization of the coliphage N4-coded single-stranded DNA binding protein. J Bio Chem. 1989;264:12700–12708. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohr JE, Chen F, Hill RT. Genomic analysis of bacteriophage ϕJL001: insights into its interaction with a sponge-associated alpha-Proteobacterium. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:1598–1609. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.3.1598-1609.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe TM, Eddy SR. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:955–964. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.5.955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mark DF, Richardson CC. Escherichia coli thioredoxin: a subunit of bacteriophage T7 DNA polymerase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1976;73:780–784. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.3.780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller A, Wood D, Ebright RH, Rothman-Denes LB. RNA polymerase β′ subunit: target of DNA-binding-independent transcriptional activation. Science. 1997;275:1655–1657. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5306.1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran MA, Belas R, Schell MA, González JM, Sun F, Sun S, et al. Ecological genomics of marine roseobacters. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:4559–4569. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02580-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran MA, Buchan A, Gonzalez JM, Heidelberg JF, Whitman WB, Kiene RP, et al. Genome sequence of Silicibacter pomeroyi reveals adaptations to the marine environment. Nature. 2004;432:910–913. doi: 10.1038/nature03170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul JH. Prophages in marine bacteria: dangerous molecular time bombs or the key to survival in the seas? ISME J. 2008;2:579. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2008.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope WH, Weigele PR, Chang J, Pedulla ML, Ford ME, Houtz JM, et al. Genome sequence, structural proteins, and capsid organization of the cyanophage syn5: a ‘Horned’ bacteriophage of marine Synechococcus. J Mol Biol. 2007;368:966–981. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.02.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohwer F, Segall A, Steward G, Seguritan V, Breitbart M, Wolven F, et al. The complete genomic sequence of the marine phage roseophage SIO1 shares homology with nonmarine phages. Limnol Oceanogr. 2000;45:408–418. [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Russell DW, editors. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor, NY, USA: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory.; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Schito GC. Development of coliphage N4: ultrastructural studies. J Virol. 1974;13:186–196. doi: 10.1128/jvi.13.1.186-196.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schito GC, Molina AM, Pesce A. Lysis and lysis inhibition with N4. Giorn Microbiol. 1967;15:229–244. [Google Scholar]

- Seshadri R, Kravitz SA, Smarr L, Gilna P, Frazier M. CAMERA: a community resource for metagenomics. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e75. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stojković EA, Rothman-Denes LB. Coliphage N4 N-Acetylmuramidase defines a new family of murein hydrolases. J Mol Biol. 2007;2:406–419. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan MB, Coleman ML, Weigele P, Rohwer F, Chisholm SW. Three Prochlorococcus cyanophage genomes: signature features and ecological interpretations. PLoS Biol. 2005;5:e144. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suttle CA, Chen F. Mechanisms and rates of decay of marine viruses in seawater. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:3721–3729. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.11.3721-3729.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner-Döbler I, Biebl H. Environmental biology of the marine Roseobacter lineage. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2006;60:255–280. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.60.080805.142115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K, Chen F. Prevalence of highly host-specific cyanophages in the estuarine environment. Environ Microbiol. 2008;10:300–312. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2007.01452.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willis SH, Kazmierczak KM, Carter RH, Rothman-Denes LB. N4 RNA polymerase II, a heterodimeric RNA polymerase with homology to the single-subunit family of RNA polymerases. J Bacteriol. 2002;184:4952–4961. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.18.4952-4961.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.