Abstract

Nipah virus (NiV) is a paramyxovirus whose reservoir host is fruit bats of the genus Pteropus. Occasionally the virus is introduced into human populations and causes severe illness characterized by encephalitis or respiratory disease. The first outbreak of NiV was recognized in Malaysia, but since 2001 eight outbreaks have been reported from Bangladesh. The primary pathways of transmission from bats to people in Bangladesh are through contamination of raw date palm sap by bats with subsequent consumption by humans and through infection of domestic animals (cattle, pigs, and goats), presumably from consumption of food contaminated with bat saliva or urine with subsequent transmission to people. Approximately half of recognized Nipah cases in Bangladesh developed their disease following person to person transmission of the virus. Efforts to prevent transmission should focus on decreasing bat access to date palm sap and reducing family members' and friends' exposure to infected patients' saliva.

Keywords: Nipah Virus, epidemiology, Bangladesh, Chiroptera

Discovery of Nipah Virus

Human Nipah virus (NiV) infection was first recognized in a large outbreak of 276 reported cases in peninsular Malaysia and Singapore from September 1998 through May 1999 [1-3]. Most cases had contact with sick pigs [4]. Cases presented primarily with encephalitis; 39% died [3, 5]. Autopsy studies noted diffuse vasculitis most prominently involving the central nervous system with intense immuno staining of endothelial cells with anti-Nipah virus hyperimmune serum [1]. The virus, a member of the recently designated genus Henipavirus, within the family Paramyxoviridae, was first isolated from a patient from Sungai Nipah village [1, 3]. The human outbreak of Nipah infection ceased after widespread deployment of personal protective equipment to people contacting sick pigs, restriction on livestock movements, and culling over 900,000 pigs [6].

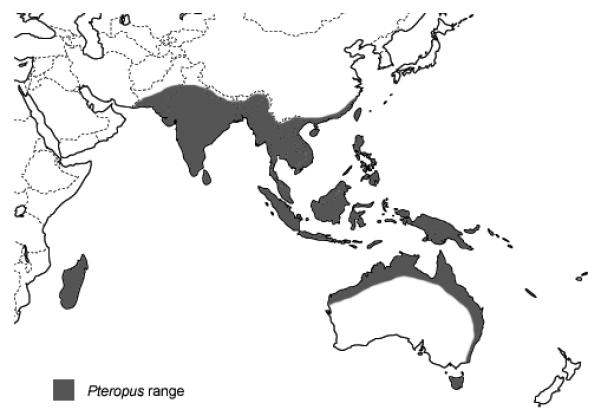

Large fruit bats of the genus Pteropus appear to be the natural reservoir of NiV. In Malaysia the seroprevalence of neutralizing antibodies to NiV in colonies of Pteropus vampyrus and P. hypomelanus ranged from 7 – 58% [7, 8]. Antibodies against henipaviruses have been identified in Pteropus bats wherever they have been tested including Cambodia, Thailand, India, Bangladesh and Madagascar [9-13]. NiV was isolated from urine specimens collected underneath a P. hypomelanus roost and from partially eaten fruit dropped during feeding activity in Malaysia [14], from urine collected underneath a P. lylei roost in Cambodia [9], and from saliva and urine of P. lylei in Thailand [10]. Experimental infection of Pteropus bats with NiV does not cause illness in the bats [15]. Surveys of rodents and other animals have not identified other wildlife reservoirs for NiV [7, 12]. Over 50 species of Pteropus bats live in South and South East Asia (Figure 1)[16]. P. giganteus, the only Pteropus species found in Bangladesh, is widely distributed across the country and frequently has antibody to NiV [12, 17].

Figure 1.

Range of Pterpous bats based on RM Nowak [16]

The growth of large intensively managed commercial pig farms in Malaysia with fruit trees on the farm created an environment where bats could drop partially eaten fruit contaminated with NiV laden bat saliva into pig stalls. The pigs could eat the fruit, become infected with NiV, and efficiently transmit virus to other pigs because of the dense pig population on the farms, frequent respiratory shedding of the virus among infected pigs [18], and the pigs' high birth rate that regularly brought newly susceptible young pigs into the population at risk [19].

Recurrent Nipah Outbreaks in Bangladesh

In the 10 years following the Nipah outbreak in Malaysia no further human cases of NiV infection have been reported from Malaysia, but eight human outbreaks of NiV infection in Bangladesh were reported from 2001 – 2008, all occurring between December and May [12, 20-24]. A total of 135 human cases of Nipah infection in Bangladesh were recognized; 98 (73%) died. One outbreak of NiV occurred in Siliguri, India, 15 kilometers north of the Bangladesh border in January and February 2001 [25] and a second NiV outbreak was reported by newspapers in Nadia District, India also close to the border with Bangladesh, in 2007 [26]. In addition to the outbreaks, between 2001 and 2007, 17 other NiV transmission events, ranging from single sporadic human cases to clusters of 2 – 4 human cases were recognized in Bangladesh [27]. Thus, in contrast to the Malaysia/Singapore outbreak, which could be coherently explained by a single or perhaps a few transmissions of NiV from an infected bat to pigs, leading to a porcine epidemic which in turn led to a human epidemic [19], in Bangladesh NiV transmission from bats to human is repeated and ongoing.

The diversity of NiV strains recovered from Bangladesh also supports multiple introductions of the virus from bats into human populations even within a single year. Among four NiV isolates from human NiV cases in 2004, the sequences of the nucleoprotein open reading frames of the isolates differed by 0.9% in nucleotide homology, in contrast to the sequences obtained from all of the human cases in Malaysia which were nearly identical to each other [28-30].

The clinical presentation of NiV infection in Bangladesh differed from Malaysia. In Bangladesh severe respiratory disease is more common, with 62% of cases having cough, 69% developing respiratory difficulty and available chest radiographs showing diffuse bilateral opacities covering the majority of the lung fields consistent with acute respiratory distress syndrome [31]. By contrast, in Malaysia, 14% of patients had a non-productive cough on presentation; only 6% of chest radiographs were abnormal and these abnormalities were mild and focal [5]. The case fatality rate was higher in Bangladesh at 73%, compared to 39% from Malaysia [5, 31], but much of this difference results from the more sophisticated clinical care provided in Malaysia. Half of Malaysian Nipah patients received mechanical ventilatory support compared to a single patient (1%) in Bangladesh [5] (unpublished data). One third of Nipah survivors in Bangladesh have moderate to severe objective neurological dysfunction 7 – 30 months after infection [32].

NiV transmission from bats to people

Epidemiological investigations in Bangladesh have identified three pathways of transmission of NiV from bats to people. The most frequently implicated route is ingestion of fresh date palm sap. Date palm sap is harvested from December through March, particularly in west central Bangladesh. A tap is cut into the tree trunk and sap flows slowly overnight into an open clay pot. Infrared camera studies confirm that P. giganteus bats frequently visit date palm sap trees and lick the sap during collection [33]. NiV can survive for days on sugar rich solutions such as fruit pulp [34]. Most date palm sap is processed at high temperature to make molasses, but some is enjoyed as a fresh juice, drunk raw within a few hours of collection. In the 2005 Nipah outbreak in Tangail District, Bangladesh, the only exposure significantly associated with illness was drinking raw date palm sap (64% among cases versus, 18% among controls OR 7.9, 95% CI, 1.6, 38, P=0.01) [22]. Twenty-one of the 23 index NiV cases recognized in Bangladesh developed their initial symptoms during the December through March date palm sap collection season[27].

A second route of transmission for NiV from bats to people in Bangladesh is via domestic animals. Fruit bats commonly drop partially-eaten saliva-laden fruit. Domestic animals in Bangladesh forage for such food. Date palm sap that is contaminated with bat feces and so is unfit for human consumption is also occasionally fed to domestic animals. The domestic animals may become infected with NiV, and shed the virus to other animals, including humans. Contact with a sick cow in Meherpur, Bangladesh in 2001 was strongly associated with Nipah infection (OR 7.9, 95% CI, 2.2, 27.7, p=.001) [12]. A pig herd visited the community two weeks before the 2003 Nipah outbreak in Naogaon and contact with the pigs was associated with illness (OR 6.1, 95% CI 1.3, 27.8, p=0.007) [35]. In 2004 one family explained that they owned two goats which their son frequently played with. The goats became ill with fever, difficulty walking, walking in circles, and frothing at the mouth. The parents believe their son had contact with goat saliva while the goats were ill. Both goats died. Within two weeks of the goats' death, the child developed encephalitis that was confirmed to be Nipah by antibody testing (unpublished data).

Third, some people may come into direct contact with NiV infected bat secretions. In the Goalando outbreak in 2004 persons who climbed trees were more likely to develop NiV infection than controls (odds ratio 8.2, 95% CI 1.3, undefined) [20].

Person to person transmission

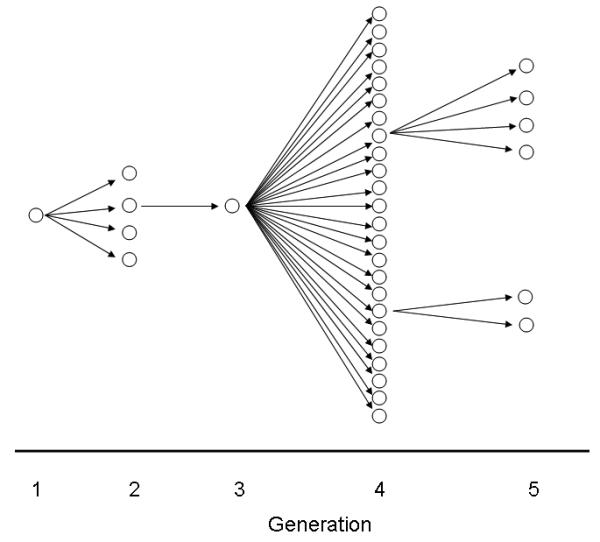

Several Bangladesh Nipah outbreaks resulted from person-to-person transmission. The clearest illustration of person to person NiV transmission occurred during the Faridpur outbreak in 2004 [21]. Four persons who cared for the index patient--his mother, his son, his aunt and a neighbor--became ill 15–27 days after the index patient first developed illness (Figure 2). During her hospitalization, the index patient's aunt was cared for by a popular religious leader who lived in a nearby village and who became ill 13 days later. When the religious leader became seriously ill, many of his relatives and members of his religious community visited at his home. Twenty-two persons developed Nipah infection after contact with the religious leader. One of these followers moved to his family's house in an adjacent village to receive care after becoming ill where he was cared for by a friend and two family members. These three caregivers and a rickshaw driver, who helped carry him to the hospital as his condition deteriorated, became ill. Ultimately, the chain of transmission involved 5 generations and affected 34 people [21] (Figure 2). Physical contact with an NiV infected patient who later died (OR 13.4, 95% CI 2.0, 89) was the strongest risk factor for developing NiV infection in the outbreak.

Figure 2.

Chain of person to person transmission in Nipah outbreak, Faridpur, Bangladesh, 2004.

The transmission pattern in Faridpur is not unique. For example, in Thakurgaon in 2007 six family members and friends who cared for an NiV infected patient developed Nipah infection. Cases were more likely than controls to have been in the same room when the index case was coughing [23]. In a review of the 122 identified Nipah cases identified in Bangladesh from 2001 through 2007, 62 (51%) developed illness after close contact with another Nipah patient [27]. A small minority of patients infected with NiV, 9 of 122 recognized cases (7%) transmitted NiV to 62 other persons.

Respiratory secretions appear to be particularly important for person-to-person transmission of NiV. NiV RNA is readily identified in the saliva of infected patients [28, 36]. Anthropological investigations during the Faridpur outbreak highlighted multiple opportunities for the transfer of NiV contaminated saliva from a sick patient to care providers [37]. Social norms in Bangladesh require family members to maintain close physical contact during illness. The more severe the illness, the more hands-on care is expected. Family members and friends without formal health care or infection control training provided nearly all the hands on care to Nipah patients both at home and in the hospital [38]. Care providers during the Faridpur outbreak continued to share eating utensils and drinking glasses with sick patients. Leftovers of food offered to see Nipah patients were commonly distributed to other family members. Family members maintained their regular sleeping arrangements, which often involved sleeping in the same bed with a sick, coughing Nipah patient. There was a particularly strong desire to have close physical contact near the time of death, demonstrated by such behaviors as cradling the patients head on the family member's lap, attempting to give liquids to the patient with a spoon or glass between bouts of coughing, or hugging and kissing the sick patient [37]. In both the Faridpur outbreak in 2004 and the Thakurgaon outbreak in 2007, persons who were in a room when a Nipah patient was coughing or sneezing were at increased risk of Nipah virus infection [21, 23]. Across all recognized outbreaks in Bangladesh from 2001 through 2007, Nipah patients with respiratory symptoms were more likely to transmit Nipah [27].

The capacity for NiV to spread in hospital settings to both staff and patients, was clearly illustrated in a large outbreak affecting 66 people in Siliguri, India in 2001. The outbreak apparently originated from an unidentified patient admitted to Siliguri District Hospital who transmitted infection to 11 additional patients, all of whom were transferred to other facilities. In two of the facilities, subsequent transmission infected 25 staff and 8 visitors [25]. However, transmission to health care workers is rarely recognized. Among a cohort of 338 health care workers who cared for Nipah patients at three Malaysian hospitals and reported a combined 89 episodes of Nipah patient blood or body fluid directly contacting their bare skin, 39 splash exposures of blood or body fluid into their eyes, nose or mouth, and 12 needle stick injuries, none developed clinical illness associated with Nipah infection [39]. Health care workers in Bangladesh have much less direct physical contact with patients than in Western hospitals [38]. Hands-on care is generally provided by family members and friends. No health care workers in Bangladesh who cared for identified Nipah patients have been identified with illness, though confirmed cases include one physician whose source of infection is unknown. A sero-survey among 105 health care workers who cared for at least one of seven patients admitted with Nipah infection at one hospital in Bangladesh identified two health care workers with serological evidence of NiV infection; however their antibody responses (IgG only, no IgM) and lack of symptoms suggest a previous infection, not recent nosocomial transmission [40].

Might person to person transmission be associated with particular strains of NiV that have genetic characteristics that lead to person to person transmission? The closely related strains in Malaysia resulted in less frequent and less severe respiratory disease than observed in Bangladesh and were not associated with frequent person to person transmission. However, the pattern of the outbreaks in Bangladesh and India suggests that person to person transmission is more dependent on the characteristics of the occasional Nipah transmitter than a specific strain. If the NiV strain was central to person to person transmission, then secondary cases of NiV would be more likely to become NiV transmitters, than primary cases (because secondary cases would already have selected for strains predisposed to person to person transmission.) However, in the review of seven years of human Nipah infection in Bangladesh, secondary cases were no more or less likely to become Nipah transmitters than were primary cases [27]. All persons who transmitted Nipah died, suggesting that late stages of infection, presumably with high virus titers, increases the risk of transmission. Even the pattern in Siliguri, the largest recognized Nipah outbreak from apparent person to person transmission, is consistent with the review of seven years of human Nipah infection in Bangladesh. The unidentified index case in Siliguri District Hospital infected 11 patients, 2 of whom infected an additional 33 patients. The 13 day duration of the outbreak at Medinova Hospital suggests two generation of transmission likely occurred there. Taken together this pattern suggests 4 NiV transmitters propagated human infection across 4 generations. There were 67 cases (66 recognized plus the unidentified index case) 4 of whom (5.9%) became Nipah transmitters, a proportion very close to the 7% recognized in Bangladesh. This suggests that the virus strain responsible for this largest recognized person to person outbreak was not exceptional. Its rate of secondary transmission was similar to other strains circulating in South Asia.

Exposures not associated with NiV transmission

Outbreak investigations have both identified important routes of transmission of human NiV infection, and identified exposures not associated with transmission. NiV was recovered from the urine of Pteropus bats in Malaysia, Cambodia and Thailand. [9, 10, 14]. In Bangladesh, P. giganteus bats live in close proximity to human populations, often roosting in trees located in rural Bangladeshi villages. Thus, bat urine, intermittently laced with NiV contaminates the immediate physical environment in many villages in Bangladesh. Yet in each of the eight Nipah outbreaks investigated in Bangladesh, an association between living near a bat roost and infection with Nipah was looked for, but never found. This suggests that the quantity of viable virus shed in bat urine is too low to initiate clinically apparent infection in humans.

Eating bat-bitten fruit is often suggested as a pathway of transmission for human Nipah infection. NiV was recovered from fruit dropped by Pteropus bats in Malaysia [14]. It is the most commonly suggested pathway for NiV transmission from bats to domestic animals. In contrast to general environmental contamination with urine, punctured fruit contaminated with bat saliva may favor virus survival. In Bangladesh where 43% of children under the age of 5 years meet the WHO standards for chronic malnutrition [41], little food is wasted. In outbreak investigations, villagers, especially children, commonly report consuming fruit which was partially eaten by bats. However, in the six NiV outbreak investigations where the question was asked, cases never reported consuming partially eaten fruit significantly more commonly than controls.

Unanswered questions

Did outbreaks of human Nipah infection occur in Bangladesh before the first outbreak was recognized in 2001? Almost certainly. P. giganteus are widely distributed across Bangladesh [16], and wherever Pteropus bats have been tested they have antibody to henipavirus [9-13]. When Pteropus bats are experimentally infected with NiV they do not become clinically ill [15], which suggests that NiV likely co-evolved with its Pteropus hosts over millennia. Bangladesh has long been densely populated, and date palm sap harvesting is an old profession using techniques and simple tools that are passed on from father to son. Moreover, people frequently die in Bangladesh of unknown causes, often outside of hospitals. Three factors that have contributed to recognition of Nipah outbreaks recently include development of diagnostic tests for Nipah infection following the Malaysian outbreak, expansion of surveillance for a range of communicable disease by the Government of Bangladesh, and expansion of news media coverage in rural Bangladesh.

Unanswered questions regarding Nipah transmission include: 1) Why is respiratory disease and person to person transmission more common among human NiV infection in Bangladesh compared to Malaysia? Are certain strains of virus more likely to cause respiratory tract disease in humans, or might the different clinical syndromes in Bangladesh and Malaysia reflect differences in host susceptibility from malnutrition or other causes? 2) How stable is the genome of Nipah? The overall nucleotide homology between a prototypical Malaysian strain of NiV and a strain of NiV from Bangladesh was 91.8% [28]. Is there a substantial risk of mutation that would improve the efficiency of person to person transmission of the virus? 3) How common is unrecognized, including subclinical, infection with NiV?

Prevention strategies

The epidemiology of NiV transmission in Bangladesh suggests two avenues to prevent human disease. The first is limiting exposure of Bangladeshi villagers to NiV contaminated fresh date palm sap. Date palm sap collection provides critical income to low income collectors and is a seasonal national delicacy enjoyed by millions every year. Steps to make the date palm sap consumption safer include diverting more of the production to molasses where the sap is cooked at temperatures above the level that NiV can survive and limiting bat access to date palm trees where the sap will be consumed fresh. A number of methods have been occasionally employed by date palm sap collectors to restrict bat access to date palm trees [42]. We are currently evaluating the effectiveness and scalability of these methods.

A second area for targeted intervention is reducing the exposure of caretakers to the saliva of seriously ill persons. When a Nipah outbreak is recognized it is appropriate to implement standard precautions [43], but recommendations to improve infection control practices more broadly in Bangladesh must consider the social and health care context in the country, where (1) the annual total per capita spending on health is $12 per person per year [44]; (2) over 99% of respiratory disease and over 99% of acute meningo encephalitis in Bangladesh is not caused by Nipah;(3) most of the people who contract Nipah are dead by the time the diagnosis is considered by local practitioners; and (4) even in the hospital setting most hands-on care is provided by family members, not health care professionals. If we recommend an unachievable level of infection control practices for persons caring for pneumonia and acute meningo encephalitis patients from rural communities in Bangladesh, we will not reduce the risk of person to person transmission of NiV in Bangladesh. An important research priority is to identify approaches that can be consistently implemented in these low income settings where family members are caring for patients with severe respiratory and neurological disease. For example, family members who washed their hands with soap after caring for Nipah patients were significantly less likely to become infected [21]. If such practices were widely adopted, they would lessen the risk of person to person transmission of NiV and other pathogens.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the many contributors to Nipah outbreak investigations in Bangladesh since 2001, both those recognized as co-authors in earlier publications, and the many field workers, laboratory technicians, and support staff whose willingness to promptly and thoroughly investigate outbreaks of this dangerous pathogen has been essential to our improved understanding of NiV epidemiology. We are also grateful to the community of scientists interested in NiV who have enlarged our understanding by posing pointed questions, and engaged the authors in prolonged discussions on Nipah transmission. We thank Michelle Luby for her assistance with drawing Figure 1 and Milton Quiah for his administrative support.

The investigations of human epidemiology of NiV infection in Bangladesh was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the U.S. National Institutes of Health Division of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, International Collaborations in Infectious Disease Opportunity Pool and the Government of Bangladesh through IHP-HNPRP (grant number MOHFW/HEALTH/AC-5/HNPR/ICDD,B/30/2003). ICDDR,B acknowledges with gratitude the commitment of CDC, NIH and the Government of Bangladesh to the centre's research efforts.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Chua KB, Bellini WJ, Rota PA, et al. Nipah virus: a recently emergent deadly paramyxovirus. Science. 2000 May 26;288(5470):1432–5. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5470.1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paton NI, Leo YS, Zaki SR, et al. Outbreak of Nipah-virus infection among abattoir workers in Singapore. Lancet. 1999 Oct 9;354(9186):1253–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)04379-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chua KB. Nipah virus outbreak in Malaysia. J Clin Virol. 2003 Apr;26(3):265–75. doi: 10.1016/s1386-6532(02)00268-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parashar UD, Sunn LM, Ong F, et al. Case-control study of risk factors for human infection with a new zoonotic paramyxovirus, Nipah virus, during a 1998-1999 outbreak of severe encephalitis in Malaysia. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2000 May;181(5):1755–9. doi: 10.1086/315457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goh KJ, Tan CT, Chew NK, et al. Clinical features of Nipah virus encephalitis among pig farmers in Malaysia. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2000 Apr 27;342(17):1229–35. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200004273421701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Uppal PK. Emergence of Nipah virus in Malaysia. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2000;916:354–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb05312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yob JM, Field H, Rashdi AM, et al. Nipah virus infection in bats (order Chiroptera) in peninsular Malaysia. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2001 May-Jun;7(3):439–41. doi: 10.3201/eid0703.010312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Daszak P, Plowright R, Epstein JH, Pulliam J, Abdul Rahman S, Field HE, Smith CS, Olival KJ, Luby S, Halpin K, Hyatt AD, HERG . The emergence of Nipah and Hendra virus: pathogen dynamics across a wildlife-livestock-human continuum. In: Collinge SRS, editor. Disease Ecology: Community structure and pathogen dynamics. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2006. pp. 186–201. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reynes JM, Counor D, Ong S, et al. Nipah virus in Lyle's flying foxes, Cambodia. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2005 Jul;11(7):1042–7. doi: 10.3201/eid1107.041350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wacharapluesadee S, Lumlertdacha B, Boongird K, et al. Bat Nipah virus, Thailand. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2005 Dec;11(12):1949–51. doi: 10.3201/eid1112.050613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Epstein JH, Prakash VB, Smith CS, et al. Henipavirus infection in Fruit Bats (Pteropus giganteus), India. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2008;14(8) doi: 10.3201/eid1408.071492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hsu VP, Hossain MJ, Parashar UD, et al. Nipah virus encephalitis reemergence, Bangladesh. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2004 Dec;10(12):2082–7. doi: 10.3201/eid1012.040701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iehle C, Razafitrimo G, Razainirina J, et al. Henipavirus and Tioman virus antibodies in pteropodid bats, Madagascar. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2007 Jan;13(1):159–61. doi: 10.3201/eid1301.060791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chua KB, Koh CL, Hooi PS, et al. Isolation of Nipah virus from Malaysian Island flying-foxes. Microbes and infection / Institut Pasteur. 2002 Feb;4(2):145–51. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(01)01522-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Middleton DJ, Morrissy CJ, van der Heide BM, et al. Experimental Nipah Virus Infection in Pteropid Bats (Pteropus poliocephalus) Journal of Comparative Pathology. 2007 May;136(4):266–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jcpa.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nowak R. Walker's Bats of the World. Johns Hopkins University Press; Baltimore: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bates PJJ, Harrison DL. Bats of the Indian Subcontinent. Harrison Zoological Museum; Kent, UK: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Middleton DJ, Westbury HA, Morrissy CJ, et al. Experimental Nipah virus infection in pigs and cats. Journal of Comparative Pathology. 2002 Feb-Apr;126(23):124–36. doi: 10.1053/jcpa.2001.0532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Epstein JH, Field HE, Luby S, Pulliam JR, Daszak P. Nipah virus: impact, origins, and causes of emergence. Current Infectious Disease reports. 2006 Jan;8(1):59–65. doi: 10.1007/s11908-006-0036-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Montgomery JM, Hossain MJ, Gurley ES, et al. Risk Factors for Nipah Virus Encephalitis in Bangladesh. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2008;10:1526–32. doi: 10.3201/eid1410.060507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gurley ES, Montgomery JM, Hossain MJ, et al. Person-to-person transmission of Nipah virus in a Bangladeshi community. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2007 Jul;13(7):1031–7. doi: 10.3201/eid1307.061128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luby SP, Rahman M, Hossain MJ, et al. Foodborne transmission of Nipah virus, Bangladesh. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2006 Dec;12(12):1888–94. doi: 10.3201/eid1212.060732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.ICDDRB Person to person transmission of Nipah infection in Bangladesh, 2007. Health and Science Bulletin. 2007;5(4):1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 24.ICDDRB Outbreaks of Nipah virus in Rajbari and Manikgonj, February. Health and Science Bulletin. 2008 March;6(1):12–3. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chadha MS, Comer JA, Lowe L, et al. Nipah virus-associated encephalitis outbreak, Siliguri, India. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2006 Feb;12(2):235–40. doi: 10.3201/eid1202.051247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mandal S, Banerjee R. Bat virus in Bengal. The Telegraph. 2007 May 8; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Luby S, Hossain J, Gurley E, et al. Recurrent Zoonotic Transmission of Nipah Virus into Humans, Bangladesh, 2001–2007. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2009;15(8):1229–35. doi: 10.3201/eid1508.081237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harcourt BH, Lowe L, Tamin A, et al. Genetic characterization of Nipah virus, Bangladesh, 2004. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2005 Oct;11(10):1594–7. doi: 10.3201/eid1110.050513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chan YP, Chua KB, Koh CL, Lim ME, Lam SK. Complete nucleotide sequences of Nipah virus isolates from Malaysia. The Journal of General Virology. 2001 Sep;82(Pt 9):2151–5. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-82-9-2151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.AbuBakar S, Chang LY, Ali AR, Sharifah SH, Yusoff K, Zamrod Z. Isolation and molecular identification of Nipah virus from pigs. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2004 Dec;10(12):2228–30. doi: 10.3201/eid1012.040452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hossain MJ, Gurley ES, Montgomery JM, et al. Clinical presentation of nipah virus infection in bangladesh. Clin Infect Dis. 2008 Apr 1;46(7):977–84. doi: 10.1086/529147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sejvar JJ, Hossain J, Saha SK, et al. Long-term neurological and functional outcome in Nipah virus infection. Annals of Neurology. 2007 Sep;62(3):235–42. doi: 10.1002/ana.21178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Khan M, Nahar N, Sultana R, Hossain M, Gurley ES, Luby S. American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene; New Orleans: 2008. Understanding bats access to date palm sap: identifying preventative techniques for Nipah virus transmission; p. 331. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fogarty R, Halpin K, Hyatt AD, Daszak P, Mungall BA. Henipavirus susceptibility to environmental variables. Virus Res. 2008 Mar;132(12):140–4. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2007.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.ICDDRB Outbreaks of encephalitis due to Nipah/Hendra-like Viruses, Western Bangladesh. Health and Science Bulletin. 2003 December;1(5):1–6. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chua KB, Lam SK, Goh KJ, et al. The presence of Nipah virus in respiratory secretions and urine of patients during an outbreak of Nipah virus encephalitis in Malaysia. The Journal of Infection. 2001 Jan;42(1):40–3. doi: 10.1053/jinf.2000.0782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blum LS, Khan R, Nahar N, Breiman RF. In-depth assessment of an outbreak of Nipah encephalitis with person-to-person transmission in Bangladesh: implications for prevention and control strategies. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2009 Jan;80(1):96–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hadley MB, Blum LS, Mujaddid S, et al. Why Bangladeshi nurses avoid 'nursing': social and structural factors on hospital wards in Bangladesh. Social Science & Medicine (1982) 2007 Mar;64(6):1166–77. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mounts AW, Kaur H, Parashar UD, et al. A cohort study of health care workers to assess nosocomial transmissibility of Nipah virus, Malaysia, 1999. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2001 Mar 1;183(5):810–3. doi: 10.1086/318822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gurley ES, Montgomery JM, Hossain MJ, et al. Risk of nosocomial transmission of nipah virus in a Bangladesh hospital. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2007 Jun;28(6):740–2. doi: 10.1086/516665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.NIPORT . Bangladesh demographic and health survey 2007. National Institute of Population Research and Training, Mitra and Associates; Dhaka, Bangladesh and Calverton, Maryland [USA}: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nahar N, Sultana R, Oliveras E, et al. American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene; New Orleans: 2008. Preventing Nipah virus infection: Interventions to interrupt bats accessing date palm sap; p. 210. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Siegel JD, Rhinehart E, Jackson M, Chiarello L. 2007 Guideline for Isolation Precautions: Preventing Transmission of Infectious Agents in Health Care Settings. American journal of infection control. 2007 Dec;35(10 Suppl 2):S65–164. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Health Economics Unit MoHaFW . A fact book on the Bangladesh HNP sector. Health Economics Unit, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare; Dhaka: 2007. [Google Scholar]