Abstract

Radical cyclizations (Bu3SnH, Et3B/air, rt) of racemic α-halo-ortho-alkenyl anilides provide 3,4-dihydroquinolin-2-ones in high yield. Cyclizations of enantioenriched precursors occur in similarly high yields and with transfer of axial chirality to the new stereocenter of the products with exceptionally high fidelity (often > 95%). Single and tandem cyclizations of α-halo-ortho-alkenyl anilides bearing an additional substituent on the α-carbon occur with high chirality transfer and high diastereoselectivity. Straightforward models are proposed to interpret both the chirality transfer and diastereoselectivity aspects. These first examples of an approach for axial chiral transfer from a reactive species in the amide to an acceptor suggest broad potential for extension both within and beyond radical reactions.

Introduction

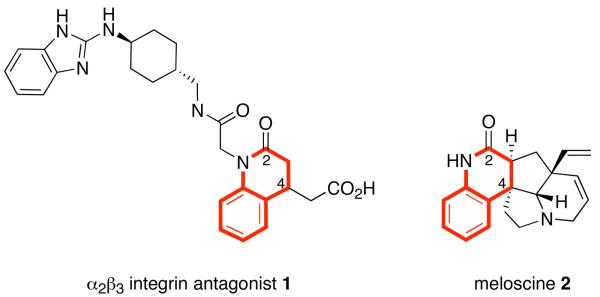

The dihydroquinolin-2-one ring is an important heterocycle that is featured in both natural products and medicinally active compounds.1 Dihydroquinolin-2-ones can exist as isolated ring systems, as in the penigquinolones,2 pinolinone,3 α2β3 integrin antagonists4 (see 1, Figure 1), and a class of HIV reverse transcriptase inhibitors.5 Or, they can be conjoined with other rings, as in scandine and the related meloscine alkaloids (see 2, Figure 1).6,7 Many methods exist to make racemic dihydroquinolin-2-ones, but only a few routes toward single enantiomers have been reported.8 These methods suffer from various drawbacks (low ee, limited generality), so new methods are needed.

Figure 1.

Representative 3,4-dihydroquinolin-2-ones with ring system highlighted in red

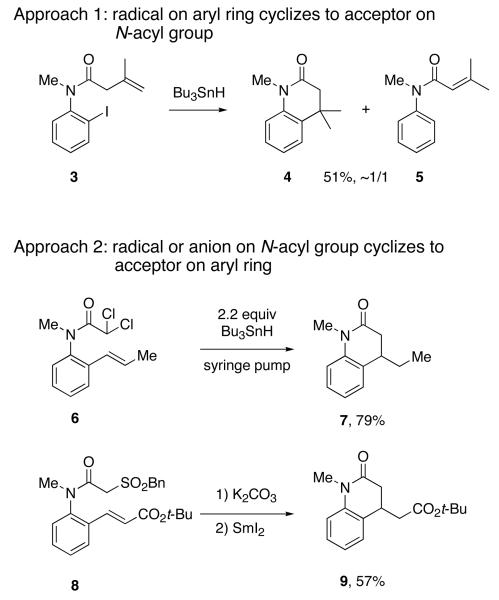

Many of the most important dihydroquinolin-2-ones have alkyl or other substituents at the C-4 position, and convenient ways to access such compounds in racemic form involve 6-exo-trig cyclizations. Figure 2 shows examples of both radical9 and ionic approaches. Jones reported that reduction of 3 with Bu3SnH provided target dihydroquinolin-2-one 4 along with comparable amounts of the product of 1,5-hydrogen transfer 5 in 51% combined yield.10 In this method (Approach 1), a radical generated on the aryl ring cyclizes to an acceptor on the anilide carbonyl group. Ikeda11 and Parsons12 took the reverse strategy (Approach 2), generating a radical adjacent to the amide carbonyl group and allowing it to cyclize onto an alkene at the ortho position of the aryl ring. For example, cyclization of 6 under syringe pump conditions provided 7 in 79% isolated yield.

Figure 2.

Two 6-exo-trig cyclization approaches to racemic dihydroquinolin-2-ones

Cyclization strategies towards these targets are not limited to radical approaches. Procter and coworkers have developed a general approach to racemic dihydroquinolin-2-ones by using intramolecular conjugation addition of α-arene sulfonyl anilides.13 For example, base-promoted cyclization of 8 followed by reductive desulfonylation with samarium diiodide provided 9 in 57% yield. α-Alkylation can be conducted between the cyclization and the desulfonylation steps to provide products with substitution at C-3. The sulfone can also be grafted to a polymer bead for solid phase synthesis.

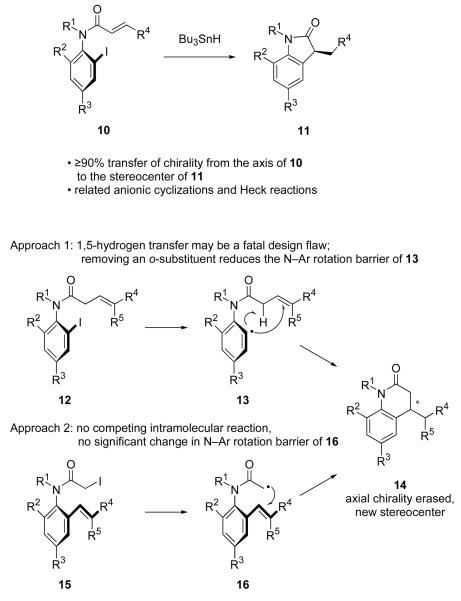

It is now widely recognized that ortho-substituted anilides like 3, 6 and 8 are not planar, as implied by the two-dimensional drawings in Figure 2. Instead, the planes of the amide group and the aryl ring are roughly orthogonal, as shown by the structures in Figure 3.14 Accordingly, the molecules are axially chiral, and stable atropisomers result with suitable substitution patterns.15 With such molecules, cyclizations (radical or otherwise) might occur with transfer of axial chirality to give a product whose configuration is predetermined by that of the starting material.16 For example, tin hydride cyclizations of o-iodoacrylanilides 10 provide indol-2-ones 11 in high yields with excellent levels of chirality transfer. The scope of this radical reaction is excellent, and anionic17 and organometallic18 variants also exist. Because this produces an indol-2-one rather than a dihydroquinolin-2-one, this reaction can be viewed as a lower homolog of Approach 1 in Figure 2.

Figure 3.

Established approach to indol-2-ones (top) compared to two potential approaches to dihydroquinolin-2-ones (bottom)

However, in assessing prospects for making dihydroquinolin-2-ones by axial chirality transfer, we felt that Approach 2 was considerably more interesting than Approach 1 for three reasons. First, the scope and generality of Approach 1 may be limited; β,γ-unsaturated amides like 12 are not as easy to make or handle as α,β-unsaturated analogs, and the competing 1,5-hydrogen transfer reaction that these substrates permit (see 13) could be a fatal design flaw in many cases.19 Second, Approach 2 represents a potentially new class of chirality transfer reaction for axially chiral anilides. In all previous reactions, a reactive intermediate (radical, anion, metal) on the aryl ring is generated first, and reacts in turn with an acceptor in a pendant side chain on the amide. Is it possible to reverse the roles of the two partners without sacrificing the high chirality transfer?

The third reason has to do with N–Ar bond rotation, which must be avoided because it results in racemization. Consider the generation of radical 13 from 12 in Approach 1. This event must cause a significant decrease in the N–Ar rotation barrier because one of the ortho-substituents is now a radical, which is much smaller than its precursor. In contrast, the N–Ar rotation barriers of precursor 15 and radical 16 in Approach 2 are likely comparable because their substitution patterns are very similar. Even so, strict prevention of N–Ar bond rotation is a necessary but not sufficient condition for axial chirality transfer. Addition to the alkene must also be face selective, as must addition to the radical (rho selectivity) if it has three different substituents (this later selectivity is not illustrated in Figure 3 because the radical has two hydrogen atoms).

Here we report details of an in-depth study of 6-exo-trig radical cyclizations of both racemic and enantiopure axially chiral α-halo-ortho-alkenyl anilides. Dihydroquinolin-2-ones are formed in good yields, and with exceptionally high fidelity in transfer of axial chirality. As a bonus, the reactions of alkyl-substituted amide radicals are also highly diastereoselective. These first results suggest that there is excellent potential to extend Approach 2 for axial chirality transfer both within and beyond radical reactions.

Results and Discussion

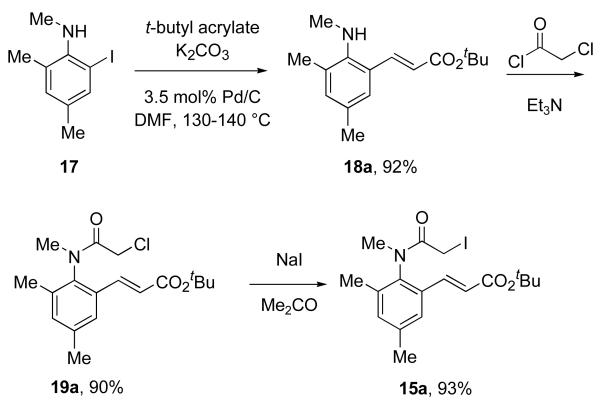

Synthesis of Radical Cyclization Precursors

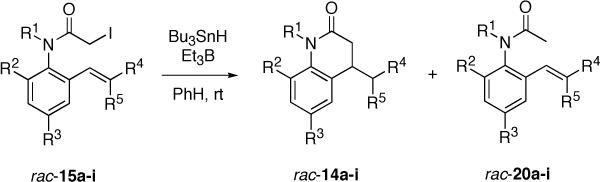

An initial set of nine radical cyclization precursors 15a-i (Table 1) was prepared in racemic form to assess the efficiency of the radical cyclization as a function of substituent pattern. The synthesis of 15a is typical, and is summarized in Scheme 1. Heck reaction of 2-iodo-N,4,6-trimethylaniline 1716e with t-butyl acrylate under ligand-free conditions20 provided 18a in 92% yield. Acylation of 18a with chloroacetyl chloride gave α-chloro anilide 19a in 90% yield. This was converted to the α-iodoanilide 15a by Finkelstein reaction in 93% yield. The syntheses of all the precursors 15a-i are described in detail in the Supporting Information. Most pathways were similar to Scheme 1, with suitable variations for substrate. Other protocols were sometimes used for the Heck reaction,21 and the trisubstituted alkene of 15i was appended by Negishi coupling.22

Table 1.

Isolated yields of radical cyclization products 14a-i from racemic precursors 15a-ia

| entry | α-I | R1 | R2 | R3 | R4 | R5 | % yieldb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 15a | Me | Me | Me | CO2t-Bu | H | 83 |

| 2 | 15b | PMB | Me | Me | CO2t-Bu | H | 85 |

| 3 | 15c | PMB | OMe | H | CO2t-Bu | H | 97 |

| 4 | 15d | Ts | Me | Me | CO2t-Bu | H | ndc,d |

| 5 | 15e | PMB | TMS | Me | CO2t-Bu | H | 93 |

| 6 | 15f | PMB | Br | Me | CO2t-Bu | H | 61 |

| 7 | 15g | PMB | Me | Me | 4-BrC6H4 | H | ndc |

| 8 | 15h | PMB | Me | Me | CN | H | < 70d |

| 9 | 15i | PMB | Me | Me | Me | Me | 51e |

Conditions: Bu3SnH and Et3B in 20 mL PhH were added over 2 h via syringe to a 10 mM PhH solution of 15.

Yield of racemic 14 after isolation by column chromatography on 10% w/w KF/silica gel.

nd = Not determined.

Fixed concentration of Bu3SnH at 5 mM.

Directly reduced 20 was detected in crude reaction mixture by TLC or 1H NMR.

Scheme 1.

Typical synthesis of a radical cyclization precursor illustrated with 15a

Cyclizations of Racemic Precursors

Table 1 compiles the key results of cyclization experiments conducted under a standard set of conditions. In a typical experiment, Bu3SnH and Et3B initiator23 were dissolved in degassed PhH, and this solution was added dropwise by syringe pump over 2 h to a non-degassed PhH solution of substrate 15a at room temperature. TLC analysis showed that the reaction was complete at the end of the addition period. The solvent was removed, and the crude mixture was directly chromatographed on 10% w/w KF/silica gel.24 This removed the tin byproducts and at the same time purified the target product 14a, which was isolated in 83%. A similar experiment at a fixed Bu3SnH concentration of 10 mM was complete in 5 min, but provided only 55% yield of a sample of 14a that was not completely separable from the directly reduced product 20a.

Substrate 15b, with an N-p-methoxybenzyl (PMB) substituent, provided product 14b in 83% purified yield. The ortho substituent was also varied in this series to include methoxy (15c, lacking the p-methyl group), trimethylsilyl (TMS, 15e) and bromine (15f) while holding the N-PMB group and the acceptor constant. The corresponding products 14c,e,f were isolated in 97, 93 and 61% yields. The TMS group of 14e survived chromatography over KF-doped silica gel.

The substituents on the acceptor were also changed to p-bromophenyl (15g), cyano (15h) and dimethyl (15i). Reduction of the p-bromophenyl substrate 15g provided a complex product mixture that did not obviously contain the expected product 14g or the reduced product 20g. The aryl bromide of 15g is probably not the culprit for this failure, because bromide 15f cyclized smoothly. Instead, we speculate that the benzyl radical resulting from cyclization will not react quickly enough with tin hydride under these conditions (low concentration and temperature),25 and instead finds other pathways. Reduction of nitrile 15h under the syringe pump conditions provided product 14h in about 70% yield but in unsatisfactory purity even after chromatography. A similar experiment conducted at fixed 5 mM concentration gave the same product in about the same yield, but now the purity was considerably better (95% estimated). The dimethyl substrate 15i provided pure 14i in 51% isolated yield. Small amounts of the directly reduced product were also produced, presumably because the alkene of 15i is not as good of a radical acceptor as the other alkenes.

Finally, a tosyl group was also probed as the N-substituent, but reduction of 15d gave a mixture of products whose major component (~80%) was the directly reduced product 20d. This failure is surprising since N-tosyl groups have been used in the past to facilitate cyclizations of α-amidoyl radicals.26

Rate constant measurements

The necessity of syringe pump conditions to minimize premature reduction in reactions of compounds 15 implies a relatively low rate constant for 6-exo-trig cyclization. This is not surprising since 6-heptenyl radicals typically cyclize more slowly than analogous 5-hexenyl ones. All the atoms connecting the radical precursor and radical acceptor are sp2-hybridized in 15, so estimating rate constants by analogy to other hexenyl and heptenyl radicals is risky. Therefore, we undertook kinetic competition experiments27 to determine the cyclization rate constant kc for the reaction of a representative compound 15b.

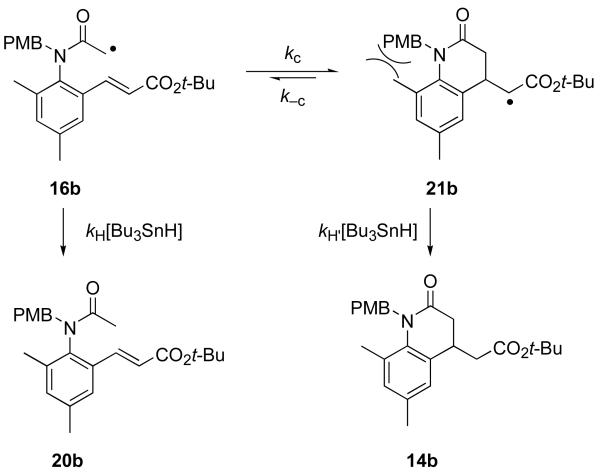

The mechanistic framework for the rate constant analysis is shown in Figure 4. Radical 16b derived from 15b can be directly reduced in a bimolecular reaction with tin hydride to give 20b. Alternatively, it can undergo 6-exo cyclization to provide a new radical 21b, which in turn reacts with tin hydride to give 14b. Measurement of the ratio of cyclized 14b to reduced 20b products as a function of tin hydride concentration provides the rate constant kc in the usual way.27

Figure 4.

Mechanistic framework for rate constant measurements

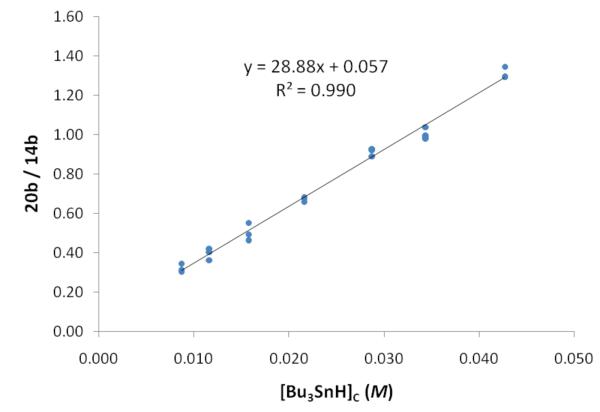

The competition experiments were performed by mixing stock benzene solutions (non-degassed) of 15b (0.025 mmol), Bu3SnH (0.030 mmol), and eicosane (internal GC standard) in round bottom flasks open to air. A hexane solution of Et3B (0.010 mmol) was added all at once. The reaction mixtures were stirred for 10 min, and were then subjected to GC analysis without workup to provide standardized yields of 14b and 20b. The average results of three trials at each concentration are summarized in Table 2, and the usual kinetic competition plot of this data is shown in Figure 5. Reactions were complete, reproducible, high-yielding (76–95%), and clean (no significant side peaks in GC analysis) in all cases.

Table 2.

Summary of results of competition experiments with 15b

| [Bu3SnH]a | % yld 14bb | % yld 20bb | total yld | red : cycd |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14.9 mM | 67 | 21 | 89 | 24 : 76 |

| 19.9 mM | 64 | 25 | 89 | 28 : 72 |

| 27.0 mM | 59 | 30 | 88 | 33 : 67 |

| 37.0 mM | 58 | 39 | 97 | 40 : 60 |

| 49.2 mM | 50 | 46 | 95 | 48 : 52 |

| 58.8 mM | 45 | 45 | 90 | 50 : 50 |

| 73.2 mM | 33 | 43 | 76 | 57 : 43 |

initial concentration.

GC yield, using eicosane as an internal standard. Yields are an average of three trials.

The ratio of reduced 20b to cyclized 14b.

Figure 5.

Kinetic competition plot of the data in Table 2 for reactions of radical 16b

By using the estimated value kH = 2.3 × 106 M−1s−1 for radical 16b,28 we calculated kc at 25 °C as 8 × 104 s−1. This value is about an order of magnitude higher than that for the 6-exo cyclization of the 6-heptenyl radical,27 presumably due to the activating effect of the ester on the alkene. It is coincidentally close to the rate constant for 5-exo cyclization of the 5-hexenyl radical (1 × 105 s−1), a value that synthetic chemists often use as a touchstone for radical cyclizations of intermediate rate.

The intercept of a plot of data for an irreversible cyclization should be zero, but the intercept in Figure 5 appears to be slightly positive. This raises the possibility that the cyclization of 16b may be reversible. From the value of the intercept, we calculated that the ring opening rate constant of k−c of 21b must be at least 25 times slower than cyclization, so the back cyclization can probably be neglected for most practical purposes. Even so, most 6-exo cyclizations to activated alkenes are irreversible.29 We speculate that the unfavorable 1,3-steric interactions between the N-substituent and the substituent of C-8 of the cyclized intermediate 21b (see Figure 4) may both retard the cyclization and promote the reverse reaction.

Resolution and measurements of rotation barriers

To perform the chirality transfer experiments, we secured highly enantioenriched samples of seven of the precursors by resolution on semipreparative chiral HPLC. Typically, samples of 15 were dissolved in i-PrOH, and injected onto either a Chiralcel OD or (S,S)-Whelk-O 1 column (25.0 cm × 21.1 mm ID) and eluted with a hexane:i-PrOH solvent mixture. Depending on the ease of separation, samples ranging in size from 40–120 mg were resolved per injection. After fraction collection and solvent removal, the enantiomeric ratios of the resolved compounds were measured by analytical chiral HPLC. Six of the compounds exhibited the expected two peaks for the individual enantiomers, which were isolated in > 98% ee.

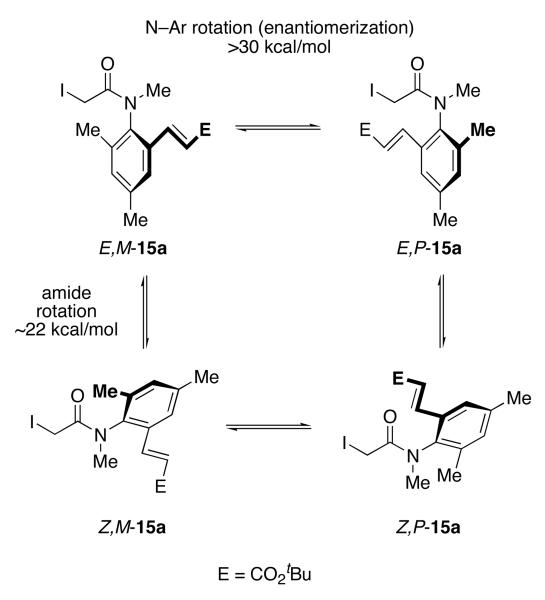

The HPLC behavior of N-methyl congener 15a was an interesting exception. This exists as a 94/6 ratio E:Z of amide rotamers as assessed by 1H NMR analysis (see Figure 6). The amide rotamers are visible by silica TLC analysis, but not isolable under ambient laboratory conditions. Analytical HPLC (Whelk, 80:20 hexanes:i-PrOH) of the sample showed a small peak at 10.5 min, followed by two large peaks at 14.5 min and 18.5 min. Analysis of the resolved fractions allowed interpretation of this chromatogram. The peak at 10.5 min is the minor Z-amide rotamer of (−)-15a, while the major E amide rotamer of (+)-15a elutes at 14.5 min. The minor Z amide rotamer of (+)-15a and the major E amide rotamer of (−)-15a overlap at 18.1 min. A plateau between the minor and major amide rotamer peaks of each enantiomer shows partial interconversion on the timescale of the HPLC separation. Based on this behavior, we estimate that the barrier for E/Z rotation is in the vicinity of ΔG‡E/Z ≈ 22 kcal/mol. This barrier is considerably higher than that for typical amides;30 however, E/Z rotamers of anilides with even larger ortho substituents have even higher barriers and can be separated and handled at ambient temperature.31 This effect complicates the measurement of the enantiomer ratio (er) of resolved 15a, but the relatively small proportion of the minor Z rotamer (6%) minimizes any error.

Figure 6.

Rotational dynamics of N-methyl anilide 15a

The other samples with N-PMB groups instead of the N-Me group did not have significant amounts of the Z rotamer at equilibrium according to analysis of their 1H NMR spectra (E/Z >98/2), and their resolutions were straightforward. Like 15a, these samples probably have a substantial barrier to E/Z rotation, but the population of the Z rotamer is so low at equilibrium that it can be neglected entirely.

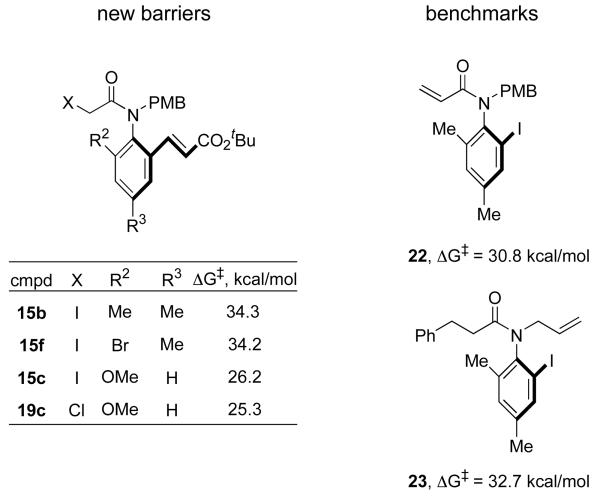

Small samples of four substrates bearing N-PMB groups were then racemized to measure their respective barriers to N-aryl bond rotation. The samples were dissolved in 90:10 hexane:i-PrOH and heated in a sealed tube at an appropriate temperature. Racemization was monitored by periodically measuring the er of aliquots of the solution by analytical chiral HPLC. The experimental data and details of the standard analysis are in the Supporting Information.

The newly measured rotation barriers are summarized in Figure 7 along with benchmarks 22 and 23 from previous work in our group.16d,e The barrier to rotation of o-methyl substrate 15b was ΔG‡rot = 34.3 kcal/mol, while the o-Br substrate 15f had a similar barrier of 34.2 kcal/mol. The magnitudes of these barriers are surprisingly high when contrasted against compounds like 22, which has the alkenyl group on the amide rather than the aryl ring; its barrier to rotation is about 3 kcal/mol lower. Even 23, which contains a primary group on nitrogen (allyl) rather than Me, has a barrier 1.5 kcal/mol lower than that for 15b. With estimated half-lives >20,000 years, atropisomers like 15b,f are essentially indefinitely stable at ambient temperature.

Figure 7.

Measured rotation barriers for amides 15 and 19 along with literature benchmarks 22 and 23

The barrier to rotation of o-methoxy substrate 15c was much lower, ΔG‡rot = 26.3 kcal/mol, and the α-chloro analog 19c was a little lower still at 25.3 kcal/mol. The 8.1 kcal/mol barrier difference between 15c and 15b is significantly larger than expected from related axially chiral systems. For example, Sternhell's model for effects of ortho-substituents in biphenyl rotation32 predicts only a 2–4 kcal/mol difference. The half-lives of the o-methoxy analogs are on the order of days at ambient temperature. So rapid room temperature reactions can be conducted with these substrates, but the resolved samples must be stored in the cold.

Chirality Transfer in 6-exo-trig cyclizations

Enantioenriched samples of 15a-c,e-f,h-i were subjected to optimized reaction conditions for reductive cyclization. The cyclized products were isolated by column chromatography over KF-doped silica, and enantiopurities were determined by chiral HPLC with reference to racemic standards of the product 3,4-dihydroquinolin-2-ones. The results of this series of experiments are shown in Table 3. Both enantiomers of each substrate were tested, and provided identical results within experimental error. Isolated yields of each product were comparable to yields of reactions with racemic substrate (Table 1). The precursor and product enantiomers are correlated in Table 3 by sign of optical rotation, except for 15f/14f, whose absolute configurations are known (see below). Correlation by elution order in the chiral HPLC is provided in the Supporting Information. Unfortunately, there was no obvious correlation between the optical rotation or HPLC elution order of substrates and the respective products of cyclization, so assigning absolute configurations by analogy is not straightforward.

Table 3.

Yields and chirality transfer levels in cyclizations of enantiomeric precursors 15 to give 14a

| entry | precursor | R1 | R2 | R3 | R4 | R5 | er | % yield 14b |

er | % cte |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | (+)-15a | Me | Me | Me | CO2t-Bu | H | 98.5/1.5 | 79 | 91/9 | 92 |

| 2 | (−)-15a | Me | Me | Me | CO2t-Bu | H | 85/15 | 81 | 84/16 | 99 |

| 3 | (+)-15b | PMB | Me | Me | CO2t-Bu | H | 100/0 | 87 | 95/5 | 95 |

| 4 | (−)-15b | PMB | Me | Me | CO2t-Bu | H | 100/0 | 85 | 96/4 | 96 |

| 5 | (+)-15c | PMB | OMe | H | CO2t-Bu | H | 99/1 | 94 | 93/7 | 94 |

| 6 | (−)-15c | PMB | OMe | H | CO2t-Bu | H | 99/1 | 96 | 93/7 | 94 |

| 7 | (+)-15e | PMB | TMS | Me | CO2t-Bu | H | 100/0 | 95 | 95/5 | 95 |

| 8 | (−)-15e | PMB | TMS | Me | CO2t-Bu | H | 100/0 | 93 | 94/6 | 96 |

| 9 | (P)-15f | PMB | Br | Me | CO2t-Bu | H | 99/1 | 63 | 95/5 | 96 |

| 10 | (M)-15f | PMB | Br | Me | CO2t-Bu | H | 0/100 | 66 | 94/6 | 94 |

| 11 | (+)-15h | PMB | Me | Me | CN | H | 99.5/0.5 | 71 | 93/7 | 93e |

| 12 | (−)-15h | PMB | Me | Me | CN | H | 99/1 | 68 | 96/4 | 97e |

| 13 | (+)-15i | PMB | Me | Me | Me | Me | 99/1 | 57 | 80/20 | 81 |

| 14 | (−)-15i | PMB | Me | Me | Me | Me | 0/100 | 55 | 80/20 | 80 |

Conditions: Bu3SnH and Et3B in 20 mL PhH were added over 2 h via syringe pump to a stirred 10 mM PhH solution of 15.

Yield of 14 after isolation by column chromatography on 10% w/w KF/silica gel.

Absolute configuration determined by X-ray crystallography.

Percent chirality transfer.

Neat Bu3SnH and Et3B were added sequentially in one portion to a stirred PhH solution of iodide with [Bu3SnH]i = 5 mM.

Briefly, the levels of chirality transfer were outstanding in almost all cases, ranging from 92 up to 99%. These high levels were not changed by altering the N-substituent (Me or PMB) or the ortho substituent (Me, Br, TMS). Even the samples of 15c with the o-methoxy group cyclized with excellent chirality transfer (94%). The only exception was 15i, which gave 14i with a chirality transfer of 80-81% (Entries 13-14). This substrate differs from the others because it lacks an activating group on the alkene and because its R4 group is Me, not H. Either difference could be responsible for the erosion, as discussed below. These values of chirality transfer in the first examples of “Approach 2” cyclizations are comparable to and usually better than those observed in “Approach 1” room temperature cyclizations of N-allyl-o-iodoacetamides (74-97%) and N-acryloyl-o-iodoanilides (49-94%).

The substrate/product pair 15f/14f incorporating an ortho-bromine atom was designed to allow assignment of absolute configuration by X-ray crystallography. Unfortunately 15f did not cooperate. With the goal of making crystalline salts, a sample of (+)-15f (99/1 er) was treated with TFA in CH2Cl2 producing α,β-unsaturated acid 24 in 71% yield (Figure 8). Salt formation became unnecessary when that acid itself crystallized by slow vapor diffusion method.

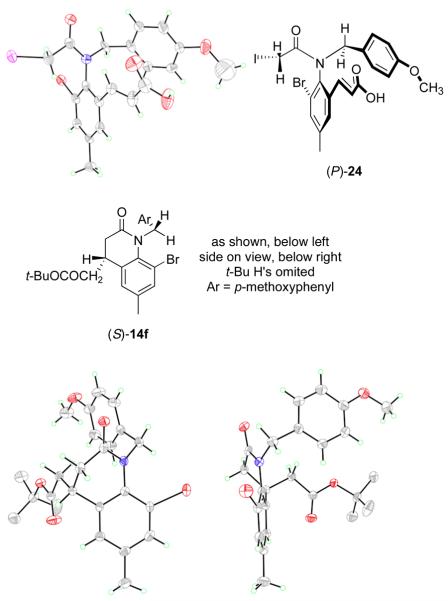

Figure 8.

X-ray crystal structures of (P)-24 (top) and 14f (bottom, with front and side views)

Acid 24 crystallized with four unique molecules in the unit cell, as two pairs of dimers displaying hydrogen bonding between the carboxylic acid groups. The differences in geometries between the four structures are small, so only one is shown in Figure 8. In this structure, the plane of the aromatic ring is almost completely orthogonal to the plane of the amide, with a torsion angle of 83°. The alkene acceptor exists in the s-trans conformation (an s-cis conformation would have significant A-strain), and is twisted slightly out of planarity with the aromatic ring (torsion angle = 156°). Interestingly, the N-PMB group is twisted to the same side of the molecule as the α,β-unsaturated carboxylic acid, with their planes nearly parallel. The 3.32–3.86 Å distance range between the two quasi-parallel planes is close to ideal for π-π stacking.33 Notice that the PMB group shields one face of the alkene. However, this shielding cannot be important in the radical cyclization because the PMB substituent is not essential for high chirality transfer. The absolute configurations of all four molecules in the unit cell were the same, and were assigned by the anomalous scattering method;34 24 and accordingly its precursor (+)-15f have the (P) configuration.

The product 14f was more cooperative; both the racemate and the pure enantiomers spontaneously solidified on standing. A crystal of (+)-14f—the product of cyclization of (+)-15f—was grown by vapor phase diffusion and the structure was solved as above; (+)-14f has the (S) configuration. Two views of this structure are shown in Figure 8. The view on the left is oriented to facilitate comparison with the structure of 15f. The view on the right, looking into the side of the 3,4-dihydroquinolin-2-one ring, shows how the serious 1,3-interaction between the N-PMB group and the o-bromine atom is minimized. The angle between these two groups cannot be 90° as in the precursor, and it cannot be 0° as normally preferred for sp2 hybridized atoms. Instead, a compromise of about 40° is reached because the lactam ring adopts a boat-like conformation that twists the N-aryl bond. This twisting occurs without appreciable pyramidalization at N, and the CH2CO2tBu substituent adopts the less-crowded axial-like orientation.

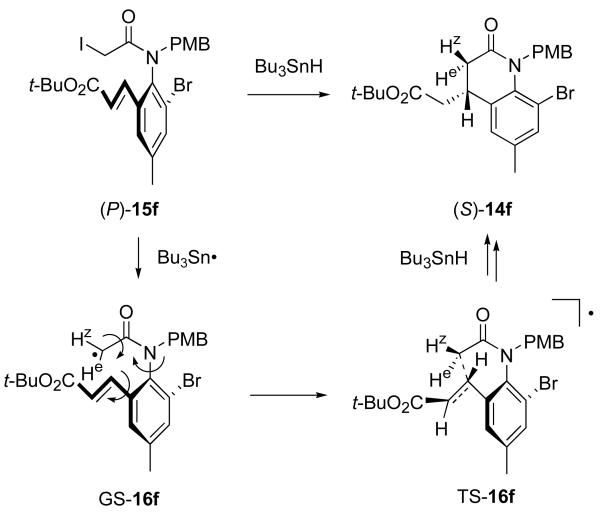

These results validate a working model that is shown in Figure 9. Iodine abstraction by a tributyltin radical from (P)-15f produces a ground state α-amidoyl radical GS-16f that has roughly orthogonal amide and aryl planes as in the precursor. Likewise, the key radical SOMO and the alkene LUMO orbitals are also nearly orthogonal in this ground state of the radical. Coordinated rotation of the N-aryl bond, the aryl-alkenyl bond and the CO–CH2• bond brings the radical to a twisted transition state TS-16f. This in turn progresses to the cyclized radical (not shown), and then the cyclized product (S)-14f after Bu3SnH reduction.

Figure 9.

Model for chirality transfer illustrated with 15f

Production of the enantiomeric product (R)-14f from radical GS-16f requires either that the N–Ar or Ar-alkenyl bond rotates the other way (or alternatively, rotates on past the TS). The former rotation seems unlikely due to the very high barrier. The latter is disfavored because the alkene C=C bond begins to eclipse the N–Ar bond.

In the model shown in Figure 9, the twisting about the NC(O)–CH2• bond has no stereochemical consequence because a new stereocenter is not formed at the radical carbon atom. That changes if one of the two hydrogen atoms, labeled He and Hz in Figure 9, is another group. α-Amidoyl radicals of the general structure NC(O)-CHR• prefer the s-cis orientation rather than s-trans.35 In other words, an R group that is appended to radical GS-16f alpha to the carbonyl group will take the position of He, not Hz. The model TS-16f then predicts that a diastereoselective cyclization should occur to give a trans-3,4-disubstituted-3,4-dihydroquinolin-2-one.

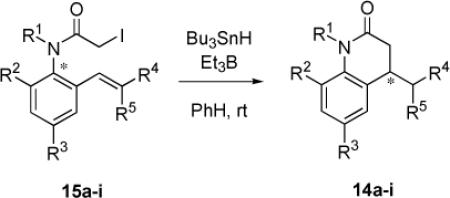

Single and tandem cyclizations of 2-substituted-α-amidoyl radicals

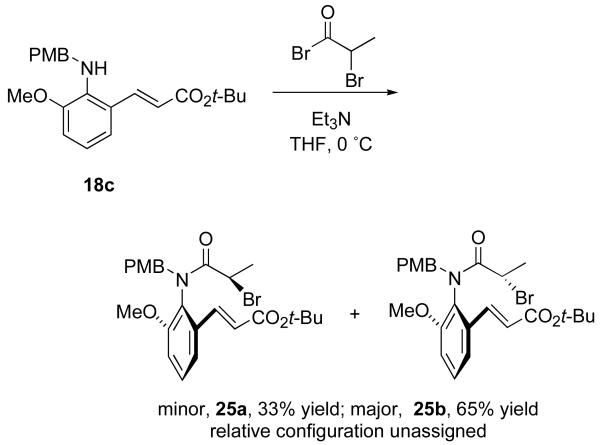

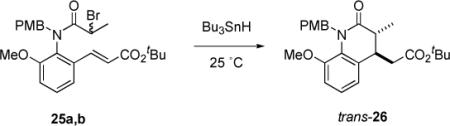

To test the prediction of diastereoselectivity, we prepared precursor 25 by acylation of PMB-aniline 18c with racemic 2-bromopropanoyl bromide, as shown in Scheme 2. Precursors 25 have both a chiral axis and a stereocenter, so two racemic diastereomers were produced. These proved to be easily separable by column chromatography and were isolated in yields of 33% and 65%. Each diastereomer was fully characterized, but we could not unambiguously assign relative configurations. Since both diastereomers gave the same products (see below), this ambiguity did not prove to be important in the reaction analysis.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis and separation of two diastereomers of precursor 25

Data for the reductive cyclizations of various isomers of 25 are summarized in Table 4. Racemic samples of 25 were reacted with Bu3SnH and Et3B at room temperature according to the usual syringe pump procedure. Both diastereomers gave the single product trans-26 in excellent yield (95-97%). The trans relative configuration was initially assigned based on analysis of coupling constants (J3,4 = 14 Hz), and this assignment was later confirmed by crystallography (see below). The cis isomer was not detected.

Table 4.

Cyclizations of secondary radical precursor 25 to 26

| entry | substrate | er | product | % yielda | er | % chirality transfer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | rac-25a | 50/50 | rac-26 | 95 | 50/50 | N/A |

| 2 | rac-25b | 50/50 | rac-26 | 97 | 50/50 | N/A |

| 3 | (+)-25a | 98/2 | (+)-26 | 98 | 98/2 | 100 |

| 4 | (−)-25a | 99/1 | (−)-26 | 96 | 98/2 | 99 |

| 5 | (+)-25b | 100/0 | (−)-26 | 98 | 99/1 | 99 |

| 6 | (−)-25b | 100/0 | (+)-26 | 97 | 99.5/0.5 | 99.5 |

Yield after isolation by column chromatography on 10% w/w KF/silica gel.

Next, both samples 25a,b were resolved by chiral HPLC to high enantiopurity, and the four pure stereoisomers were cyclized as usual (Entries 3-6). Yields were reproducibly high (96-98%), and chirality transfers were nearly perfect. The values (99-100%) are even higher than those observed for the primary α-amide radical precursor series. Each enantiomer in a given diastereomeric pair gives a different enantiomer of the product. Across the diastereomeric pairs, (+)-25a and (−)-25b give the same enantiomer of the product (+)-26, so these compounds must have the same configuration in the chiral axis and opposite configurations at the stereocenter. Likewise for the (−)-25a and (+)-25b pair; each gives (−)-26. These results show that the stereoselectivity is dictated by the chiral axis and not the stereocenter. In other words, the diastereomeric pairs of bromides with the same chiral axis configuration provide the same radical. This is sensible since the initially produced radical has sp2 geometry.35,36

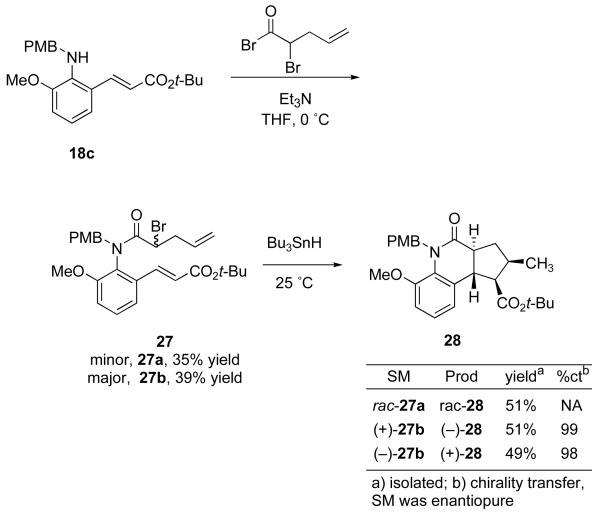

Radical cyclizations often proceed with high levels of diastereoselectivity when the radical and alkene acceptor are connected by a pre-formed ring, so we extended the design to incorporate a second cyclization that incorporated new elements of stereoselectivity.37 The synthesis and cyclizations of tandem precursor 27a-b are shown in Scheme 3. Racemic 2-bromo-4-pentenoic acid was converted to the acid chloride, which was used to acylate 18c. This produced diastereomers 27a (35% yield) and 27b (39% yield) that were separated by column chromatography. Again, the relative configurations of 27a,b were not assigned.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis and cyclization of tandem precursor 27

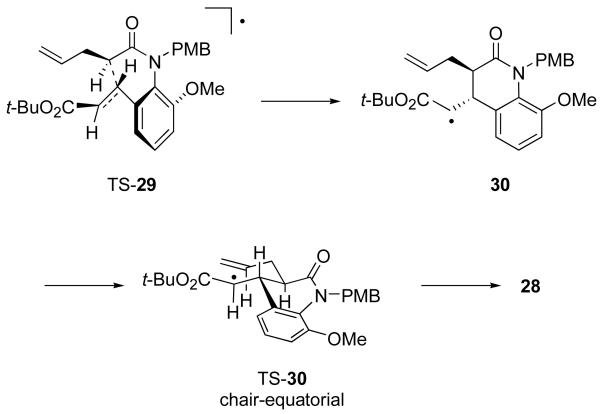

Tandem cyclization of a single enantiomer of 27 can give as many as 16 stereoisomers of 28; however, we already know that racemization will not occur and that the first cyclization should be highly diastereoselective for the trans isomer. This reduces to four the number of likely product isomers. Since we already understood the effect of the relative stereochemistry from the experiments in Table 3, we cyclized one of the diastereomers of 27 as a racemate, and resolved the other prior to cyclization.

Racemic 27a was treated with Bu3SnH under syringe pump conditions at room temperature (Scheme 3). After column chromatography, tricyclic product rac-28 was isolated in 51% yield as a single diastereomer. Other fractions of side products contained, among other unidentified compounds, two minor diastereomers of the 6-endo-trig/5-exo-trig sequence, as evidenced by two distinct doublets in the upfield region denoting the respective methyl signals of the diastereomers. Enantiopure samples of 27b were accessed by resolution with chiral HPLC, and were also subjected to the reaction conditions. These reactions provided the same diastereomer but opposite enantiomers of 28 in similar yields and excellent chirality transfer (98-99%).

Because the minor products and various impurities were inseparable from each other, it was not possible to characterize any of the secondary products or to provide an accurate measure of the diastereoselectivity in the second cyclization. However, we conservatively estimate that none of the minor products exceeded 10% of the mixture, so the second cyclization must also be reasonably diastereoselective (≥4/1).

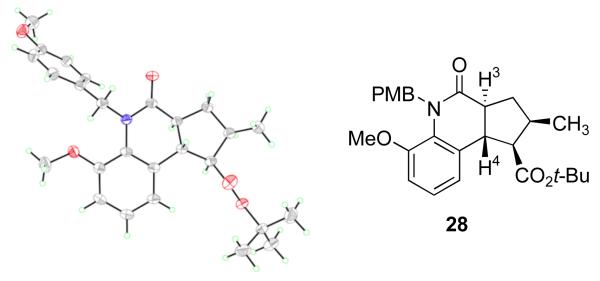

The structure of rac-28 was established by X-ray crystallography, and a diagram is shown in Figure 10. The ring fusion is trans,38 and J3,4 is again 14.1 Hz with a dihedral angle H3–C3–C4–H4 of 176° in the crystal. This confirms the assignment of trans relative configuration of 26 above.

Figure 10.

X-ray crystal structure of tricycle 28

Models for the first and second cyclizations of the radicals generated from 27 are shown in Figure 11. The model for the first cyclization, which also serves for the radical derived from 25, follows directly from the model for the primary radical (Figure 9). The alkyl group on the radical center (R = Me or CH2CH=CH2) orients itself s-cis to the anilide carbonyl group. Then, twisting as indicated in TS-29 directs the first cyclization with control of both relative and absolute configuration. The structure of the major isomer 28 formed in the second cyclization follows directly from the Beckwith-Houk model39 of a chair-like transition state TS-30 with equatorial-like substituents on the forming ring. The minor products can arise from a chair-like transition state with the radical substituent in a quasi-axial orientation, or boat-like transition states with either axial or equatorial orientations. In flexible systems, the chair and boat can flip to provide additional possible geometries, but the rigidity of the ring fusion to the 3,4-dihydroquinolone ring prevents that flip in this case.

Figure 11.

Models of first and second cyclizations of radicals derived from 27

Conclusions

Radical cyclizations (Bu3SnH, Et3B/air, rt) of an assortment of α-halo-ortho-alkenyl anilides provide 3,4-dihydroquinolin-2-ones in high yield. The precursors are axially chiral (stable atropisomers) but the products are not. Cyclizations of enantioenriched precursors occur with transfer of axial chirality to the new stereocenter of the products with exceptionally high fidelity (often > 95%). Single and tandem cyclizations of α-halo-ortho-alkenyl anilides bearing an additional substituent on the α-carbon occur with both high chirality transfer and high diastereoselectivity. Overall, the new method is an attractive route for stereoselective synthesis of diverse 3,4-dihydroquinolin-2-ones.

Crystal structures have been used to rigorously assign configurations of one precursor and two products. Straightforward models interpret both the chirality transfer and diastereoselectivity aspects, reinforcing the notion that predictions of stereochemical outcomes of reactions of axially chiral amides are both easy and reliable.

Prior reactions with axial chirality transfer in the anilide series have featured reactive intermediates (radicals, anions, transition metals) on the aryl ring of the anilide and acceptors in the amide. This first-in-class example of the reverse approach suggests broad potential for axial chirality transfer from assorted reactive intermediates in the amide to acceptors on the aryl ring.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the National Science Foundation for funding this work and the National Institutes of Health for a grant to purchase an NMR spectrometer.

Footnotes

SUPPORTING INFORMATION AVAILABLE: Contains procedures of synthesis and characterization data of all new compounds and copies of NMR spectra. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References and Footnotes

- 1.For a more complete collection of references to biologically active 3,4-dihydroquinolin-2-ones and methods of synthesis, see: Zhou W, Zhang L, Jiao N. Tetrahedron. 2009;65:1982–1987.

- 2.Ito C, Itoigawa M, Otsuka T, Tokuda H, Nishino H, Furukawa H. J. Nat. Prod. 2000;63:1344–1348. doi: 10.1021/np0000318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kimura Y, Kusano M, Koshino H, Uzawa J, Fujioka S, Tani K. Tetrahedron Lett. 1996;37:4961–4964. [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Ellis D, Kuhen KL, Anaclerio B, Wu B, Wolff K, Yin H, Bursulaya B, Caldwell J, Karanewsky D, He Y. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006;16:4246–4251. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.05.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Patel M, McHugh RJ, Jr., Cordova BC, Klabe RM, Bacheler LT, Erickson-Viitanen S, Rodgers JD. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2001;11:1943–1945. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(01)00331-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seitz W, Geneste H, Backfisch G, Delzer J, Graef C, Hornberger W, Kling A, Subkowskic T, Norbert Z. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2008;18:527–531. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.11.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(b) Bernauer K, Englert G, Vetter W, Weiss E. Helv. Chim. Acta. 1969;52:1886–1905. [Google Scholar]; c) Oberhänsli WE. Helv. Chim. Acta. 1969;52:1905–1911. [Google Scholar]; d) Plat M, Hachem-Mehri M, Koch M, Scheidegger U, Potier P. Tetrahedron Lett. 1970;39:3395–3398. [Google Scholar]; Isolation: Bernauer K, Englert G, Vetter W. Experientia. 1965;21:374–375. doi: 10.1007/BF02139743.

- 7.(b) Denmark SE, Cottell JJ. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2006;348:2397–2042. [Google Scholar]; c) Selig P, Bach T. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:5082–5084. doi: 10.1002/anie.200800693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Selig P, Herdtweck E, Bach T. Chem. Eur. J. 2009;15:3509–3525. doi: 10.1002/chem.200802383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Synthesis: Overman LE, Robertson GM, Robichaud AJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991;113:2598–2610.

- 8.(a) El Ali B, Okuro K, Vasapollo G, Alper H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:4264–4270. [Google Scholar]; (b) Dong C, Alper H. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2004;15:35–40. [Google Scholar]; (c) Okuro K, Kai H, Alper H. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 1997;8:2307–2309. [Google Scholar]; (d) Blay G, Cardona L, Torres L, Pedro JR. Synthesis. 2007:108–112. [Google Scholar]; e) Bolm C, Hildebrand JP. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998;39:5731–5734. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Other radical approaches include bimolecular additions, see reference 1, and cyclizations to isocyanates, see: Minin PL, Walton JC. J. Org. Chem. 2003;68:2960–2963. doi: 10.1021/jo034002o.

- 10.(a) Clark AJ, Jones K, McCarthy C, Storey JMD. Tetrahedron Lett. 1991;32:2829–2832. [Google Scholar]; (b) Clark AJ, Jones K. Tetrahedron. 1992;48:6875–6882. [Google Scholar]; (c) Lopez de Turiso FG, Curran DP. Org. Lett. 2005;7:151–154. doi: 10.1021/ol0477226. Related additions to aryl rings. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Sato T, Ishida S, Ishibashi H, Ikeda M. J. Chem. Soc. Perk. Trans. 1. 1991:353–359. [Google Scholar]; (b) Ishibashi H, Sato T, Ikeda M. Synthesis. 2002;6:695–713. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Allan GM, Parsons AF, Pons J-F. Synlett. 2002:1431–1434. [Google Scholar]

- 13.McAllister LA, Turner KL, Brand S, Stefaniak M, Procter DJ. J. Org. Chem. 2006;71:6497–6507. doi: 10.1021/jo060940n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.(a) Oki M. Allinger NL, Eliel E, Wilen SH, editors. Top. Stereochem. 1983;14:1–81. [Google Scholar]; (b) Oki M. The Chemistry of Rotational Isomers. Springer-Verlag; New York: 1993. [Google Scholar]; (c) Wolf C. Dynamic Stereochemistry of Organic Compounds. RSC Publishing; Cambridge, UK: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 15.(a) Curran DP, Hale GR, Geib SJ, Balog A, Cass QB, Degani ALG, Hernandes MZ, Freitas LCG. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 1997;8:3955–3975. [Google Scholar]; (b) Adler T, Bonjoch J, Clayden J, Font-Bardía M, Pickworth M, Solans X, Solé D, Vallverdú L. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2005;3:3173–3183. doi: 10.1039/b507202f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Petit M, Lapierre AJB, Curran DP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:14994–14995. doi: 10.1021/ja055666d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.(a) Curran DP, Qi H, Geib SJ, DeMello NC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994;116:3131–3132. [Google Scholar]; (b) Curran DP, Liu WD, Chen CH-T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:11012–11013. [Google Scholar]; (c) Ates A, Curran DP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:5130–5131. doi: 10.1021/ja010467p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Curran DP, Chen CHT, Geib SJ, Lapierre AJB. Tetrahedron. 2004;60:4413–4424. [Google Scholar]; (e) Petit M, Geib SJ, Curran DP. Tetrahedron. 2004;60:7543–7552. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guthrie DB, Curran DP. Org. Lett. 2009;11:249–251. doi: 10.1021/ol802616u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lapierre AJB, Geib SJ, Curran DP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:494–495. doi: 10.1021/ja067790i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Curran DP, Abraham AC, Liu HT. J. Org. Chem. 1991;56:4335–4337. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Opatz T, Ferenc D. Org. Lett. 2006;8:4473–4475. doi: 10.1021/ol061617+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jeffery T. Tetrahedron. 1996;52:10113–10130. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Campbell JB, Jr., Firor JW, Davenport TW. Synth. Commun. 1989;19:2265–2272. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yorimitsu H, Oshima K. In: Radicals in organic synthesis. Renaud P, Sibi MP, editors. Vol. 1. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2001. pp. 11–27. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harrowven DC, Guy IL. Chem. Commun. 2004:1968–1969. doi: 10.1039/b406041e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Franz JA, Suleman NK, Alnajjar MS. J. Org. Chem. 1986;51:19–25. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stork G, Mah R. Heterocycles. 1989;28:723–727. [Google Scholar]

- 27.(a) Newcomb M. Tetrahedron. 1993;49:1151–1176. [Google Scholar]; (b) Newcomb M. In: Radicals in Organic Synthesis. 1st ed. Renard P, Sibi M, editors. Vol. 1. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2001. pp. 317–336. [Google Scholar]

- 28.(a) Chatgilialoglu C, Dickhaut J, Giese B. J. Org. Chem. 1991;56:6399–6403. [Google Scholar]; (b) Chatgilialoglu C, Ingold KU, Scaiano JC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1981;103:7739–7742. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hanessian S, Dhanoa DS, Beaulieu PL. Can. J. Chem. 1987;65:1859. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stewart WE, Siddall TH. Chem. Rev. 1970;70:517–551. [Google Scholar]

- 31.(a) Chupp JP, Olin JF. J. Org. Chem. 1967;32:2297–2303. [Google Scholar]; (b) Ototake N, Taguchi T, Kitagawa O. Tetrahedron Lett. 2008;49:5458–5460. [Google Scholar]; (c) Nobutaka O, Masashi N, Yasuo D, Haruhiko F, Osamu K. Chem. Eur. J. 2009;15:5090–5095. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bott G, Field LD, Sternhell S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1980;102:5618–5626. [Google Scholar]

- 33.(a) Maddaluno JF, Gresh N, Giessner-Prettre C. J. Org. Chem. 1994;59:793–802. [Google Scholar]; (b) Roesky HW, Andruh M. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2003;236:91–119. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dunitz JD. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2001;40:4167–4173. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20011119)40:22<4167::AID-ANIE4167>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Porter NA, Giese B, Curran DP. Acc. Chem. Res. 1991;24:296–304. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Musa OM, Choi SY, Horner JH, Newcomb M. J. Org. Chem. 1998;63:786–793. doi: 10.1021/jo9717907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Interestingly, however, the rate of rotation of rotation about the NC(O)-CHMe(•) may be similar to or possibly even slower than the rate of radical cyclization. If that is the case, then both diastereomers of precursor must produce the same s-cis radical. For rotation rate information see: Strub W, Roduner E, Fischer H. J. Phys. Chem. 1987;91:4379–4383.

- 37.Curran DP, Porter NA, Giese B. Stereochemistry of Radical Reactions: Concepts, Guidelines, and Synthetic Applications. VCH Publishers, Inc.; New York: 1996. pp. 30–82. see especially. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Akritopoulou-Zanze I, Whitehead A, Waters JE, Henry RF, Djuric SW. Tetrahedron Lett. 2007;48:3549–3552. doi: 10.1021/ol070164l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Spellmeyer DC, Houk KN. J. Org. Chem. 1987;52:959–974. [Google Scholar]; Beckwith ALJ, Schiesser CH. Tetrahedron Lett. 1985;26:373–376. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.