Abstract

The alveolar epithelial cell (AEC) Na,K-ATPase contributes to vectorial Na+ transport and plays an important role in keeping the lungs free of edema. We determined, by cell surface labeling with biotin and immunofluorescence, that approximately 30% of total Na,K-ATPase is at the plasma membrane of AEC in steady-state conditions. The half-life of the plasma membrane Na,K-ATPase was about 4 hours, and the incorporation of new Na,K-ATPase to the plasma membrane was Brefeldin A sensitive. Both protein kinase C (PKC) inhibition with bisindolylmaleimide (10 μM) and infection with an adenovirus expressing dominant-negative PKCζ prevented Na,K-ATPase degradation. In cells expressing the Na,K-ATPase α1-subunit lacking the PKC phosphorylation sites, the plasma membrane Na,K-ATPase had a moderate increase in half-life. We also found that the Na,K-ATPase was ubiquitinated in steady-state conditions and that proteasomal inhibitors prevented its degradation. Interestingly, mutation of the four lysines described to be necessary for ubiquitination and endocytosis of the Na,K-ATPase in injurious conditions did not have an effect on its half-life in steady-state conditions. Lysosomal inhibitors prevented Na,K-ATPase degradation, and co-localization of Na,K-ATPase and lysosomes was found after labeling and chasing the plasma membrane Na,K-ATPase for 4 hours. Accordingly, we provide evidence suggesting that phosphorylation and ubiquitination are necessary for the steady-state degradation of the plasma membrane Na,K-ATPase in the lysosomes in alveolar epithelial cells.

Keywords: Na,K-ATPase; alveolar epithelial cells; ubiquitination; lysosome; degradation

CLINICAL RELEVANCE

This is the first report studying the degradation in steady-state conditions of the plasma membrane Na,K-ATPase in alveolar epithelial cells. We found that ubiquitination was necessary for the plasma membrane Na,K-ATPase lysosomal degradation and that the mechanism differs from the one under pathologic conditions.

In patients with acute lung injury (ALI) and acute respiratory distress syndrome, there is fluid accumulation in the alveoli and impaired gas exchange, in part due to the decreased ability of the lungs to clear edema (1–3). Edema reabsorption in the alveolar epithelium is mediated via active vectorial Na+ transport, with the basolaterally located Na,K-ATPase being the major contributor (4, 5). The minimal functional unit of the Na,K-ATPase is a heterodimer of an α- and a β-subunit (6).

Impairment of Na,K-ATPase function due to its endocytosis and degradation has been reported as a common mechanism in many models of ALI (7–12). Models of alveolar hypoxia and hypercapnia have provided insights into the mechanisms of Na,K-ATPase endocytosis (7, 10, 11, 13, 14), with phosphorylation of the Na,K-ATPase α1-subunit at Ser18 by protein kinase C (PKC)ζ as the trigger signal (7, 10). Phosphorylation at Ser18 is followed by binding of ubiquitin at any of the four lysines that surround the phosphorylated residue, which leads to Na,K-ATPase endocytosis and degradation (9, 12, 15).

In this report, we set out to investigate the steady-state levels of the alveolar epithelial plasma membrane Na,K-ATPase and its degradation pathways. We found that approximately 30% of the Na,K-ATPase in AEC is at the plasma membrane and has a half-life of about 4 hours. Interestingly, Na,K-ATPase degradation in the lysosome during steady-state conditions required phosphorylation and ubiquitination, but via a different pathway than in pathologic (i.e., hypoxic) conditions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

All cell culture reagents were from Mediatech Inc (Herndon, VA). Ouabain was purchased from ICN Biomedicals, Inc. (Aurora, OH). Bisindolylmaleimide I, E64, pepstatin, lactacystin, and MG-132 were form Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA). All other chemicals were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Secondary goat anti-mouse-Alexa-488 and LysoTracker Red DND-99 were from Invitrogen (Eugene, OR). The Na,K-ATPase α1 monoclonal antibody (clone 464.6) was from Upstate Biotech (Lake Placid, NY). The Na,K-ATPase β1 monoclonal antibody (clone M17-P5-F11) was from Affinity BioReagents (Golden, CO). Monoclonal anti-ubiquitin (cloneP4D1), monoclonal anti-GFP (B-2), and polyclonal rab7 antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Mouse anti-HA.11 antibody (clone 16B12) was from Covance (Emeryville, CA). Polyclonal anti-GFP antibody was from Clontech (Palo Alto, CA). Secondary goat anti-mouse horseradish peroxidase was from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA).

Cell Culture

Human A549 (ATCC CCL 185) were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 20 mM Hepes. Cells were incubated in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2/95% air at 37°C. GFP-rat-Na,K-ATPase-α1-subunit- (7), GFP-S18A-rat-Na,K-ATPase-α1-subunit- (16), WT-rat-Na,K-ATPase-α1-subunit- (7), Δ5–26N-rat Na,K-ATPase-α1-subunit-, GFP-K4R-rat-Na,K-ATPase-α1-subunit- (15), and HA-rat-Na,K-ATPase-α1-subunit-A549 cells were grown as above, but 3 μM ouabain was added to suppress the endogenous Na,K-ATPase α1 subunit.

Alveolar Epithelial Type II Cell Isolation and Culture

Alveolar epithelial type II (ATII) cells were isolated from pathogen-free male Sprague-Dawley rats (200–225 g) as previously described (17). Briefly, the lungs were perfused via the pulmonary artery, lavaged, and digested with elastase (3 U/ml; Worthington Biochemical, Freehold, NJ). ATII cells were purified by differential adherence to IgG-pretreated dishes, and cell viability was assessed by trypan blue exclusion (> 95%). Cells were incubated in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2–95% air at 37°C. The day of isolation and plating is designated Day 0. All experimental conditions were performed in Day 3 cells.

Permanent Transfection

A549 cells were plated in 10-cm plates at 3–4 × 106 cells/plate and transfected with 14 μg of plasmid DNA (Δ5-26N-rat Na,K-ATPase-α1-subunit; a gift of Dr. C. Pedemonte, University of Houston, Houston, TX [18]; HA(2x)119I rat Na,K-ATPase-α1-subunit; a gift from Dr V. Canfield, Penn State College of Medicine, Hershey, PA [19]) by using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) as indicated by the manufacturer. Individual colonies were isolated using cloning cylinders (PGC Scientifics, Frederick, MD), and the resulting cell lines were propagated in complete DMEM supplemented with 3 μM ouabain.

Biotinylation of Cell Surface Proteins

Cells were placed on ice, washed twice with ice-cold PBS (with Ca2+ and Mg2+), and surface proteins were labeled for 10 minutes using 1 mg/ml EZ-link NHS-SS-biotin (Pierce Chemical Co., Rockford, IL) following the protocol by Gottardi and coworkers (20). After labeling, the cells were rinsed three times with PBS containing 100 mM glycine to quench unreacted biotin and then lysed in modified RIPA (m-RIPA) buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, 100 μg/ml TPCK, and 1 mM PMSF).

For pulse-chase experiments, after quenching unreacted biotin, warm DMEM was added to the cells. Then, after incubating at 37°C for the desired times, cells were washed in ice-cold PBS and lysed in m-RIPA. Proteins were incubated at 4°C with end-over-end shaking in the presence of streptavidin beads (Pierce Chemical) for a period of 2 hours to overnight. Beads were thoroughly washed (16), resuspended in 30 μl of Laemmli's sample buffer solution, and analyzed by Western blot.

Quantitation of Fractions

The relative amount of Na,K-ATPase present in the total, intracellular, and surface fractions was calculated as described before (21). Briefly, cells were biotinylated and lysed as described above. A portion of the cell lysate was retained and considered the total fraction; the remaining cell lysate was incubated with streptavidin beads, and after three consecutive streptavidin precipitations, the remaining supernatant was considered the intracellular fraction. The beads (considered the surface fraction) were washed and solubilized in equivalent volumes (to volume initially added to beads) of Laemmli's sample buffer solution. Several dilutions of the total, intracellular, and surface fractions were run on the same SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blot as described below. The density of each band was determined in arbitrary densitometric units and was plotted versus sample volume. Curves for each fraction were generated and analyzed by linear analysis on GraphPad Prism (version 4.00 for Windows; GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Fractions were quantitated as the percentage of total as follows: (1) the sample needed to give the same densitometric value was determined for each fraction, (2) comparisons among sample volumes for each sample were done only when they fell on the liner range of all curves simultaneously, and (3) values were considered only when surface plus intracellular fractions were ± 20% of the total value (see Figure 1A).

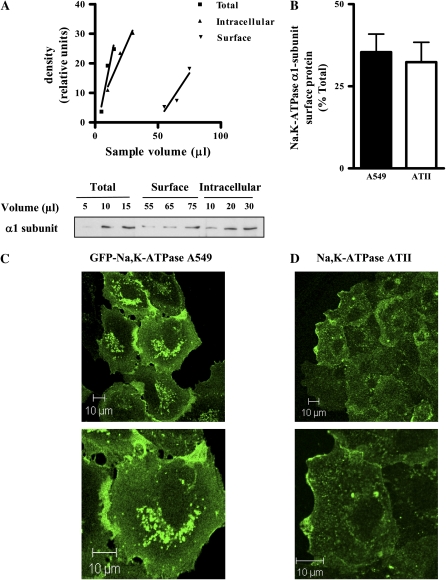

Figure 1.

Approximately 32% of the Na,K-ATPase is at the plasma membrane in alveolar epithelial cells. (A) Alveolar epithelial cells (AEC) were labeled with biotin and total, intracellular, and plasma membrane fractions were isolated as described in Materials and Methods. Several dilutions of the total, intracellular, and surface fractions were run on the same SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blot. The volume of each band was determined in arbitrary densitometric units and was plotted versus sample volume. Upper panel: representative quantitation. Lower panel: representative Western blot. (B) Graph representing the % of Na,K-ATPase protein at the plasma membrane on human A549 cells (solid bar, mean ± SEM, n = 12) and rat ATII cells (open bar, mean ± SEM, n = 9). (C) Representative image of A549 cells expressing the Na,K-ATPase α1-subunit with a GFP tag, fixed, and visualized by confocal microscopy. (D) Representative image of ATII cells fixed, immunostained with an antibody against the Na,K-ATPase α1-subunit and visualized by confocal microscopy.

Western Blot Analysis

Protein was quantified by Bradford assay (Bio-Rad) and resolved in 10% polyacrylamide gels (SDS-PAGE). Thereafter, proteins were transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes (Optitran; Schleider and Schuell, Keene, NH) using a semi-dry transfer apparatus (Bio-Rad). Incubation with specific antibodies was performed overnight at 4°C. Blots were developed with a chemiluminescence detection kit (PerkinElmer Life Sciences, Boston, MA) used as recommended by the manufacturer. The bands were quantified by densitometric scan and ImageJ software (ImageJ 1.41a; National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD).

Confocal Microscopy

A549 cells expressing the Na,K-ATPase α1-subunit with a GFP tag and ATII cells were fixed for 10 minutes in methanol (−20°C), permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 and blocked in 1 μg/μl Normal goat serum + 2% BSA. The Na,K-ATPase was visualized by using an anti-α1-subunit antibody (1:100) and a secondary antibody labeled with Alexa 488 (1:200). GFP was directly visualized. Cellular distribution of Na,K-ATPase α1-subunit was analyzed by direct fluorescence using a Zeiss LSM 510 laser-scanning confocal microscope (objective Plan Apochromat, ×63/1.4 oil; Zeiss, Heidelberg, Germany). Cross-sections were generated with a 0.2-μm motor step. Contrast and brightness settings were adjusted so that all pixels were in the linear range. Quantification of fluorescence intensity was calculated using ImageJ software (ImageJ 1.41a; National Institutes of Health).

To study the degradation of the plasma membrane Na,K-ATPase in HA-A549 cells, cells were placed on ice, incubated with anti-HA antibody for 45 minutes and placed back at 37°C for 3 hours. The remaining extracellular antibody was stripped with an acid wash (0.5% acetic acid, pH 3) before fixing with 4% formaldehyde. Immunofluorescence image was taken using a goat anti-mouse antibody labeled with Alexa 488 with a confocal microscope. Cells were loaded with lysotracker (red) for 15 minutes at 37°C before fixing.

Preparation of Intracellular Compartments

A549 cells were biotinylated as described above and incubated for 4 hours in the absence or presence of 100 μM chloroquine at 37°C. Cells were placed on ice, washed twice with ice-cold PBS and resuspended in homogenization buffer (250 mM sucrose, 3 mM imidazole, 2 mM EGTA, 1 mM PMSF, 100 μg/ml TPCK, and 10 μg/ml leupeptin, pH 7.4). Cells were gently homogenized (15–20 strokes) by using a Dounce homogenizer, and the samples were centrifuged for 5 minutes (4°C, 500 × g). Intracellular compartments were fractionated on a flotation gradient as previously described (22) by using the technique of Gorvel and coworkers (23). Briefly, the postnuclear supernatant was loaded in 40.6% sucrose and overlaid successively with 16% sucrose in deuterium oxide (D2O), 10% sucrose in D2O, and with homogenization buffer. The endosomal carrier vesicles are recovered between the 16% and 10% sucrose layers. Basolateral plasma membranes can be isolated as described below from the fraction recovered between the 40.6% and 16% layers. Fractions were solubilized with 1% NP-40 and biotinylated Na,K-ATPase was pulled down with streptavidin beads.

Preparation of Basolateral Membranes

A549 cells incubated for 4 hours in the absence or presence of 5 μg/ml Brefeldin A at 37°C, or samples recovered from the sucrose gradient described above, were washed twice with ice-cold PBS, and basolateral membranes (BLMs) were purified according to Hammond et al. by using a 16% Percoll gradient (24).

Adenoviral Infection

Seventy percent confluent A549 cells cultured in 60-mm plates were infected with 20 pfu of null or dominant-negative PKCζ adenovirus (Cell Biolabs, San Diego, CA), in DMEM. After 4 hours of incubation, the medium was removed and replaced with fresh DMEM. Twenty-four hours after infection, cells were labeled with biotin and a pulse-chase experiment was performed as described above.

Immunoprecipitation

A549-GFPα1 or A549-GFPα1-K4R cells were incubated for 4 hours with 20 μM MG-132 at 37°C. The incubation was terminated by placing the cells on ice, aspirating the media, washing twice with ice-cold PBS and adding lysis buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.45, 50 mM KCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 1% Nonidet P-40, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, 100 μg/ml TPCK, and 1 mM PMSF). Cells were scraped from the plates and cell lysates were centrifuged for 5 minutes at 20,000 × g. Lysates were pre-cleared for 1 hour with Protein A/G PLUS-Agarose (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) and equal amounts of protein (500–1,000 μg) were then incubated with polyclonal anti-GFP antibody overnight at 4°C. Protein A/G PLUS-Agarose was added, and the samples were incubated for 2 hours at 4°C. The samples were then washed three times with lysis buffer and resuspended in Laemmli's sample buffer solution. Samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blot.

Statistical Analysis

Data are represented as means ± SEM. Comparisons between two groups of values were evaluated by Student's t test. Multiple comparisons were made using a one-way ANOVA followed by a multiple comparison test (Dunnett) when the F statistic indicated significance. Results were considered significant when P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Approximately 30% of the Na,K-ATPase Is at the Plasma Membrane in Alveolar Epithelial Cells with a Half-Life of Approximately 4 Hours

We determined the relative amount of the Na,K-ATPase pool at the plasma membrane in steady-state conditions by labeling the surface Na,K-ATPase with biotin and comparing it to the intracellular pool as described in Materials and Methods. We found that the alveolar epithelial cell (AEC) line A549 had approximately 32% of the Na,K-ATPase at the cell surface at any given time (35.4 ± 5.5%, n = 12), similar to primary rat alveolar epithelial type II cells (ATII) (32.4 ± 6%, n = 9) (Figure 1B). These data were corroborated by immunofluorescence of A549 cells expressing GFP-α1-Na,K-ATPase or ATII cells immunolabeled with an antibody against the Na,K-ATPase α1-subunit (Figures 1C and 1D, respectively). Quantification of the immunofluorescence intensity revealed that the amount of Na,K-ATPase at the plasma membrane was: 32.8 ± 4.9% in A549 cells and 27.8 ± 1.64% in ATII cells (n = 5).

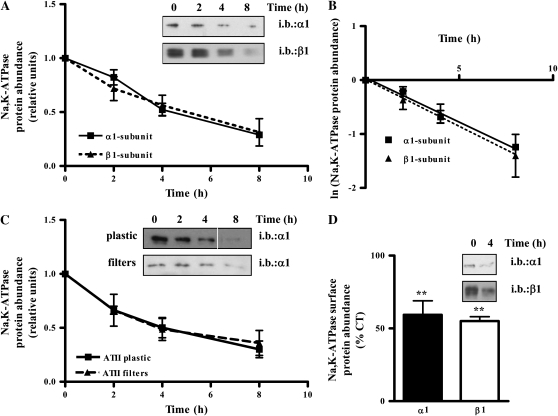

To determine Na,K-ATPase stability, we performed biotin pulse-chase experiments and found that the plasma membrane Na,K-ATPase α1-subunit had a half-life of approximately 4.2 hours (n = 4), while the Na,K-ATPase β1-subunit had a half-life of approximately 4 hours (n = 4) (Figures 2A and 2B). The half-life was calculated using the equation Bt = B0e−kt, where Bt is the band density at time t and B0 is the initial band density (25). The degradation constant (k) corresponded with the slope calculated by linear regression of the plot of the natural logarithm of the band density versus time (Figure 2B). The stability of the Na,K-ATPase at the plasma membrane was the same in both A549 cells and in primary rat alveolar epithelial cells, independent of whether they were grown on plastic (4.05 h, n = 4) or in filters under air–liquid interface (4.4 h, n = 4) (Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

The half-life of the plasma membrane Na,K-ATPase α1- and β1-subunits is approximately 4 hours. (A) A549 cells were labeled with biotin and a pulse-chase was performed. Upper panel: representative Western blot. Lower panel: graph represents mean ± SEM, n = 4. (B) Graph represents the natural logarithm of the band density as a function of time. The line trough the points was calculated by linear regression. The slope of the line is the degradation constant used to calculate the half-life. (C) ATII cells grown on plastic or in filters were labeled with biotin and a pulse-chase was performed. Upper panel: representative Western blot. Lower panel: graph represents mean ± SEM, n = 4. (D) A549 cells were incubated for 4 hours with 5 μg/ml Brefeldin A, basolateral membranes were isolated and the amount of Na,K-ATPase α1- and β1-subunits was determined by Western blot with specific antibodies. Graph represents mean ± SEM, n = 3 (**P < 0.01).

As shown in Figure 2D, we also conducted experiments in which anterograde transport was blocked by incubating the cells with 5 μg/ml Brefeldin A, a fungal toxin used to inhibit Golgi-based membrane vesicle fusion (26, 27). We found that after incubation for 4 hours with Brefeldin A, the protein abundance of both Na,K-ATPase subunits at the plasma membrane was decreased by 50%, indicating that the turnover of the protein at the plasma membrane corresponded with our estimated half-life of about 4 hours.

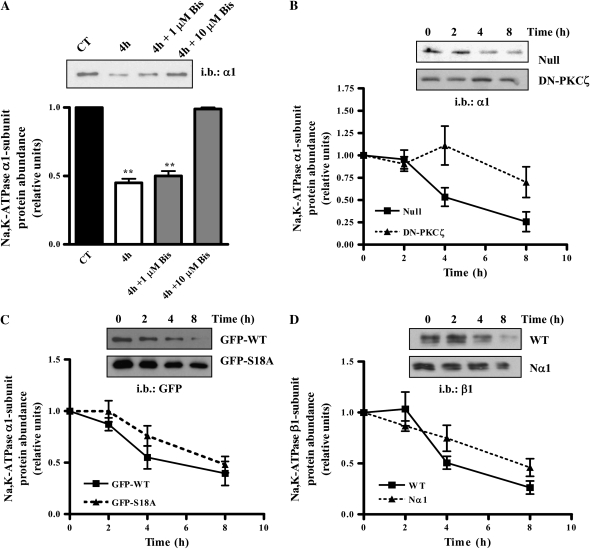

Phosphorylation by PKCζ Is Necessary for Na,K-ATPase Degradation

Phosphorylation of the Na,K-ATPase α1-subunit by PKCζ has been shown to be the first step necessary for endocytosis to occur (7, 8, 10, 15, 28). Therefore, we set out to determine whether phosphorylation is required in the degradation process during steady-state conditions. We found that after 4 hours of incubation with the PKC inhibitor bisindolylmaleimide, degradation of the Na,K-ATPase was prevented at a dose of 10 μM, suggesting a role for the atypical PKCζ isoform (7, 29) (Figure 3A). The involvement of PKCζ in the degradation of the plasma membrane Na,K-ATPase was confirmed by infecting A549 cells with an adenovirus expressing a dominant-negative (DN) PKCζ. As shown in Figure 3B, overexpression of DN-PKCζ increased the half-life of the Na,K-ATPase by 4.6-fold (Null: 3 h, DN-PKCζ: 14 h; n = 3), suggesting an important role for phosphorylation by PKCζ in the degradation of the Na,K-ATPase in steady-state conditions.

Figure 3.

Phosphorylation by PKCζ is necessary for Na,K-ATPase degradation in steady-state conditions. (A) A549 cells were biotinylated and pulse-chased for 0 and 4 hours in the presence of the PKC inhibitor Bysindolylmaleimide (Bis). Upper panel shows a representative Western blot. Graph represents mean ± SEM, n = 3 (**P < 0.01). (B) A549 cells were infected with 20 pfu of Null or DN-PKCζ adenovirus, and a pulse-chase assay was performed 24 hours after transfection. Upper panel shows a representative Western blot. Graph represents mean ± SEM, n = 3. (C) GFP-rat-Na,K-ATPase-α1-subunit- and GFP-S18A-rat-Na,K-ATPase-α1-subunit-A549 cells were labeled with biotin and a pulse-chase was performed. Upper panel: representative Western blot. Lower panel: graph represents mean ± SEM, n = 4. (D) WT-rat-Na,K-ATPase-α1-subunit- and Δ5–26N-rat Na,K-ATPase-α1-subunit- A549 cells were labeled with biotin and a pulse-chase was performed. Upper panel: representative Western blot. Lower panel: graph represents mean ± SEM, n = 4.

Two PKC phosphorylation sites have been described in the Na,K-ATPase α1-subunit, Ser11 and Ser18; Ser11 is present in all species, while S18 is only expressed in rat (30). Ser18 is a known target of PKCζ phosphorylation, necessary for subsequent endocytosis (10, 15). We found that in cells expressing the Na,K-ATPase α1-subunit in which the Ser18 has been mutated to an alanine (S18A), the rate of degradation decreased approximately 1.5 times (WT: 4.8 h and S18A: 6.6 h; n = 4) (Figure 3C). To explore whether other sites in the N-terminus (i.e., Ser11) were necessary for phosphorylation and degradation of the Na,K-ATPase, we generated a stable cell line expressing a Na,K-ATPase α1-subunit lacking the first 26 amino acids, which includes both PKC phosphorylation sites. We then studied the stability of the Na,K-ATPase β1-subunit because most antibodies used to detect the Na,K-ATPase α1-subunit recognize the N-terminus of the protein. As depicted in Figure 3D, this clone had a stability similar to the one with the S18A mutation, about 1.5 times longer degradation time (WT: 3.69 h, Nα1: 6.38 h; n = 4), suggesting that just one of the phosphorylation sites is necessary for the endocytosis and degradation.

The Ubiquitin-Proteasomal Pathway Is Involved in the Plasma Membrane Na,K-ATPase Degradation

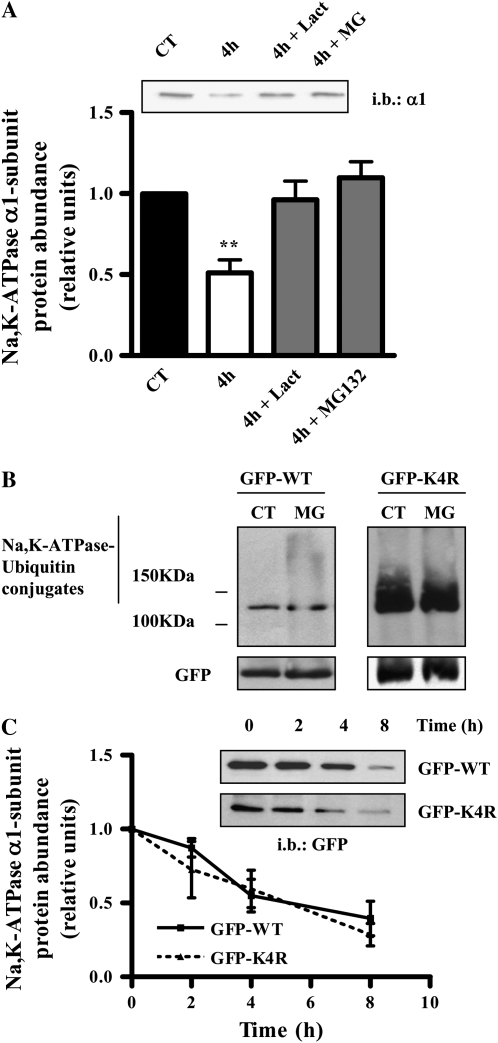

The proteasomal pathway has been shown to participate in the degradation of the Na,K-ATPase (9, 31). In agreement with these observations, we found that incubation for 4 hours with the proteasomal inhibitors MG-132 (20 μM) and lactacystin (20 μM) prevented the degradation of the Na,K-ATPase located at the plasma membrane (Figure 4A).

Figure 4.

The ubiquitin-proteasonal pathway is necessary for Na,K-ATPase degradation in steady-state conditions. (A) A549 cells were biotinylated and pulse-chased for 0 and 4 hours in the presence of the proteasomal inhibitors Lactacystin (Lact) and MG-132 (MG). Upper panel shows a representative Western blot. Graph represents mean ± SEM, n = 4. (B) GFP-rat-Na,K-ATPase-α1-subunit- and GFP-K4R-rat-Na,K-ATPase-α1-subunit-A549 cells were incubated for 4 hours in the presence of MG-132. Cells were lysed and immunopreciptated using a GFP antibody. Immunoprecipitates were immunoblotted against ubiquitin. The membranes were then stripped and re-blotted against GFP as loading control (n = 4). (C) GFP-rat-Na,K-ATPase-α1-subunit- and GFP-K4R-rat-Na,K-ATPase-α1-subunit-A549 cells were labeled with biotin and a pulse-chase was performed. Upper panel: representative Western blot. Lower panel: graph represents mean ± SEM, n = 4 (**P < 0.01).

To study whether the Na,K-ATPase itself was ubiquitinated in steady-state conditions, we incubated cells for 4 hours with the proteasome inhibitor MG132 and found an “ubiquitin smear” above the molecular weight corresponding to the Na,K-ATPase consistent with the presence of ubiquitin conjugates (Figure 4B, left panel).

It has been reported that under hypoxic conditions the Na,K-ATPase α1-subunit is phosphorylated at Ser18 with consequent ubiquitination of the lysines that surround that residue (15). To determine the involvement of these lysines in the degradation of the plasma membrane Na,K-ATPase, we studied the rate of degradation of the Na,K-ATPase in A549 clones expressing a Na,K-ATPase α1-subunit with all lysines residues described to be ubiquitinated mutated to arginines (K16, K17, K19, and K20; K4R cells) (15), and found no difference in the rate of degradation as compared with wild-type cells (WT: 4.7 h; K4R: 4.2 h) (Figure 4C). To determine whether these clones could still be ubiquitinated in steady-state conditions, cells were incubated for 4 hours with the proteasome inhibitor MG132, and a similar ubiquitin smear was observed in these K4R mutants cells comparable to that found in wild-type cells (Figure 4B, right panel), suggesting that these residues do not participate in the Na,K-ATPase steady-state degradation.

The Plasma Membrane Na,K-ATPase Is Degraded in the Lysosomes

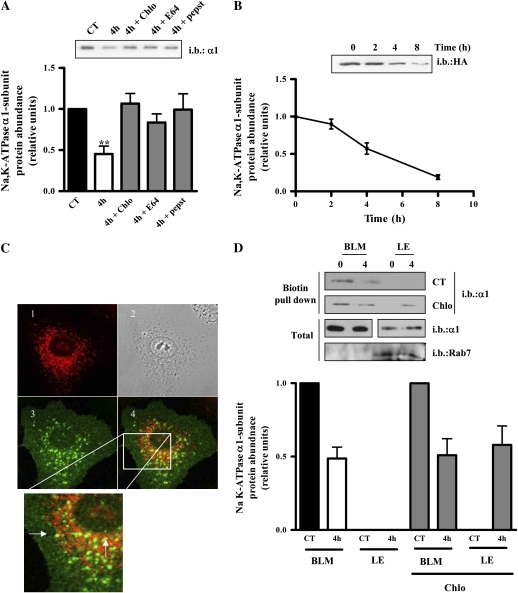

As depicted in Figure 5A, incubation for 4 hours with the lysosomal inhibitors chloroquine (100 μM), E64 (10 μM), and pepstatin (10 μM) prevented the degradation of the plasma membrane Na,K-ATPase. To further study this pathway, we used A549 cells stably expressing the rat Na,K-ATPase α1-subunit containing an extracellular HA-tag to label and follow the plasma membrane Na,K-ATPase. First, as shown in Figure 5B, we determined that the presence of the tag did not alter the stability of the Na,K-ATPase at the plasma membrane (HAα1: 3.03 h, n = 3). To study whether the plasma membrane Na,K-ATPase was degraded in lysosomes, we labeled these cells with an anti-HA antibody and allowed the Na,K-ATPase to internalize for 3 hours at 37°C. The antibody that remained at the cell surface was removed, and the location of the internalized protein was studied by immunofluorescence. Figure 5C shows co-localization of lysosomes and the plasma membrane Na,K-ATPase. To confirm lysosomal degradation of the plasma membrane Na,K-ATPase, we incubated A549 cells in the presence of the lysosomal inhibitor chloroquine for 4 hours and studied the accumulation of the plasma membrane Na,K-ATPase in intracellular compartments. As depicted in Figure 5D, only in cells treated with chloroquine was it possible to observe accumulated plasma membrane Na,K-ATPase in the late endosomal compartments (enriched in Rab7) (32, 33), further supporting the lysosomal degradation of the plasma membrane Na,K-ATPase in steady-state conditions.

Figure 5.

The plasma membrane Na,K-ATPase is degraded at the lysosomes. (A) A549 cells were biotinylated and pulse-chased for 0 and 4 hours in the presence of the lysosomal inhibitors chloroquine (Chlo), E64, and pepstatin (pepst). Upper panel shows a representative Western blot. Graph represents mean ± SEM, n = 3. (B) HA-rat-Na,K-ATPase-α1-subunit-A549 cells were labeled with biotin and a pulse-chase was performed. Upper panel: representative Western blot. Lower panel: graph represents mean ± SEM, n = 3. (C) HA-rat-Na,K-ATPase-α1-subunit-A549 were incubated with HA antibody, placed back at 37°C for 3 hours, and the remaining extracellular antibody was stripped and cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde. HA was detected using a goat anti-mouse antibody labeled with Alexa 488 (panel 3, green). Cells were loaded with lysotracker (panel 1, red) for 15 minutes at 37°C before fixing. (D) A549 cells were incubated in the presence or absence of chloroquine for 4 hours, and late endosomal compartments (LE; enriched in Rab 7) and BLMs were isolated. Upper panel shows a representative Western blot. Graph represents mean ± SEM, n = 3 (**P < 0.01).

DISCUSSION

The plasma membrane Na,K-ATPase of alveolar epithelial cells (AEC) is regulated during injury via an endocytosis and degradation process that seems to follow a regulated pathway: the phosphorylation-ubiquitination-recognition-endocytosis-degradation or PURED pathway (9, 15, 34). The PURED pathway has been proposed as a mechanism for the internalization and degradation of cell surface proteins involving a series of events in which phosphorylation acts as a signal for ubiquitination, leading to the endocytosis and degradation of membrane proteins (35, 36). In the present study, we set out to determine whether the plasma membrane Na,K-ATPase follows this process in steady-state conditions in AEC.

We found that the Na,K-ATPase protein abundance at the plasma membrane in AEC was about 32% of the total pool, similar to the amount described in lacrimal acinar cells (20–(40% of the total pool) (37, 38); however, in renal cells approximately 50% of the Na,K-ATPase is present at the plasma membrane (39, 40). These results are in agreement with the hypothesis that a significant pool of Na,K-ATPase is accessible for recruitment from intracellular compartments to the plasma membrane after treatment with dopamine and α- and β-adrenergic agonists in AEC (22, 41, 42).

Classically, the Na,K-ATPase has been considered to belong to the class of long-lived proteins (∼ 72 h) (31); however, this appears to be cell type specific. It has been shown that the half-life is 10 to 12 hours in LLC-PK1 cells (43), while the half-life of the total pool is approximately 24 hours in HeLa cells and in AEC (9, 44), which correlates with a degradation rate of the plasma membrane Na,K-ATPase (∼ 32% of total) of about 4 hours (Figure 2 and Ref. 12). This rapid turnover allows the abundance of Na,K-ATPase at the plasma membrane to adjust rapidly in response to changing physiologic or pharmacologic demands (7, 10, 11, 16, 29, 45, 46).

The Na,K-ATPase is a phosphorylation substrate for several PKC isoforms (47); in particular, phosphorylation by PKCζ in the N-terminus of the Na,K-ATPase α1-subunit has been described as a requisite for its endocytosis (7, 10, 15). We found that PKCζ was necessary for the degradation of the plasma membrane Na,K-ATPase. Two PKC phosphorylation sites have been described in the Na,K-ATPase α1-subunit, Ser11 and Ser18; Ser11 is present in all species, while S18 is only expressed in rat (30). Phosphorylation of either of these residues has been described to be involved in the Na,K-ATPase endocytosis (7, 10, 48).We found that mutation of Ser18 to alanine or deletion of the first 26 amino acids of the α1-subunit increased the half-life of the protein 1.5 times (see Figure 3), suggesting that phosphorylation of these residues might be important to initially accelerate the endocytosis process (7, 8, 10, 28), but is not essential in the degradation process during steady-state conditions. The inhibition of PKCζ prevented the degradation to a much greater extent than the one observed in the mutants lacking the phosphorylation sites, suggesting a role for PKCζ in an intermediary step of the endocytosis/degradation processes. For example, phosphorylation by PKCζ of the adaptor protein-2 μ2 has been shown to be required for the endocytosis of the Na,K-ATPase (49).

Both the lysosome and the proteasome have been suggested to participate in the degradation of the Na,K-ATPase (9, 31). In agreement with these observations, inhibition of both pathways prevented the degradation of the plasma membrane Na,K-ATPase. We found that the Na,K-ATPase is ubiquitinated in basal conditions, as incubation for 4 hours with a proteasomal inhibitor led to the detection of Na,K-ATPase–ubiquitin conjugates. It has been reported that in hypoxic conditions, the Na,K-ATPase α1-subunit was ubiquitinated in any of the four lysines that surround Ser18 (K16, K17, K19, K20) and that ubiquitination is necessary for the Na,K-ATPase endocytosis and degradation (9, 15). Surprisingly, we found that the half-life of a Na,K-ATPase mutant in which these four lysines have been substituted with arginines was the same as that of the Na,K-ATPase in control cells; however, we observed an increased abundance of Na,K-ATPase–ubiquitin conjugates in these mutant cells, suggesting that possibly some of the other 53 lysines in the Na,K-ATPase α1-subunit are possibly ubiquitination sites in steady-state conditions.

In the present report, we demonstrated that the Na,K-ATPase is degraded in the lysosomal compartment in steady-state conditions, as we found co-localization of lysosomes with the plasma membrane Na,K-ATPase as well as an intracellular accumulation of the plasma membrane Na,K-ATPase when the cells were treated with a lysosome inhibitor. Also, the above data suggest that the Na,K-ATPase is not a direct target of the proteasome. Both processes are compatible, as it has been previously reported for other plasma membrane proteins such as the epidermal growth factor receptor and E-cadherin, which have been shown to be ubiquitinated and degraded in the lysosomes (50, 51). Previous reports have suggested that the effects of proteasome inhibitors are mostly due to free ubiquitin depletion resultant from the suppression of preteasomal functioning by the inhibitors (50). Also, we have shown previously that pretreatment with the proteasomal inhibitor MG132 prevented Na,K-ATPase endocytosis, which could also explain our results (15).

In summary, we provide evidence that in steady-state conditions approximately 32% of the Na,K-ATPase is at the plasma membrane with a half-life of about 4 hours. This process is dependent on phosphorylation and ubiquitination events which leads to its degradation in the lysosomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the valuable insights to this manuscript of Ms. Lynn C. Welch and Ms. Aileen M. Kelly.

This research was partially supported by National Institutes of Health grants HL48129, HL71643, and HL85534 (J.I.S.).

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0365OC on March 13, 2009

Conflict of Interest Statement: None of the authors has a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Ware LB, Matthay MA. The acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 2000;342:1334–1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ware LB, Matthay MA. Alveolar fluid clearance is impaired in the majority of patients with acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001;163:1376–1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sznajder JI. Alveolar edema must be cleared for the acute respiratory distress syndrome patient to survive. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001;163:1293–1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matthay MA, Folkesson HG, Clerici C. Lung epithelial fluid transport and the resolution of pulmonary edema. Physiol Rev 2002;82:569–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vadász I, Raviv S, Sznajder J. Alveolar epithelium and Na,K-ATPase in acute lung injury. Intensive Care Med 2007;33:1243–1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blanco G, Mercer RW. Isozymes of the Na-K-ATPase: heterogeneity in structure, diversity in function. Am J Physiol 1998;275:F633–F650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dada LA, Chandel NS, Ridge KM, Pedemonte C, Bertorello AM, Sznajder JI. Hypoxia-induced endocytosis of Na,K-ATPase in alveolar epithelial cells is mediated by mitochondrial reactive oxygen species and PKC-{zeta}. J Clin Invest 2003;111:1057–1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vadász I, Morty RE, Olschewski A, Konigshoff M, Kohstall MG, Ghofrani HA, Grimminger F, Seeger W. Thrombin impairs alveolar fluid clearance by promoting endocytosis of Na+,K+-ATPase. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2005;33:343–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Comellas AP, Dada LA, Lecuona E, Pesce LM, Chandel NS, Quesada N, Budinger GRS, Strous GJ, Ciechanover A, Sznajder JI. Hypoxia-mediated degradation of Na,K-ATPase via mitochondrial reactive oxygen species and the ubiquitin-conjugating system. Circ Res 2006;98:1314–1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Briva A, Vadasz I, Lecuona E, Welch LC, Chen J, Dada LA, Trejo HE, Dumasius V, Azzam ZS, Myrianthefs PM, et al. High CO2 levels impair alveolar epithelial function independently of pH. PLoS One 2007;2:e1238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vadász I, Dada LA, Briva A, Trejo HE, Welch LC, Chen J, Tóth PT, Lecuona E, Witters LA, Schumacker PT, et al. AMP-activated protein kinase regulates CO2-induced alveolar epithelial dysfunction in rats and human cells by promoting Na,K-ATPase endocytosis. J Clin Invest 2008;118:752–762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou G, Dada LA, Chandel NS, Iwai K, Lecuona E, Ciechanover A, Sznajder JI. Hypoxia-mediated Na-K-ATPase degradation requires von Hippel Lindau protein. FASEB J 2008;22:1335–1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Litvan J, Briva A, Wilson MS, Budinger GRS, Sznajder JI, Ridge KM. Beta-adrenergic receptor stimulation and adenoviral overexpression of superoxide dismutase prevent the hypoxia-mediated decrease in Na,K-ATPase and alveolar fluid reabsorption. J Biol Chem 2006;281:19892–19898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dada LA, Novoa E, Lecuona E, Sun H, Sznajder JI. Role of the small GTPase RhoA in the hypoxia-induced decrease of plasma membrane Na,K-ATPase in A549 cells. J Cell Sci 2007;120:2214–2222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dada LA, Welch LC, Zhou G, Ben-Saadon R, Ciechanover A, Sznajder JI. Phosphorylation and ubiquitination are necessary for na,k-atpase endocytosis during hypoxia. Cell Signal 2007;19:1893–1898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lecuona E, Dada LA, Sun H, Butti ML, Zhou G, Chew T-L, Sznajder JI. Na,K-ATPase α1-subunit dephosphorylation by protein phosphatase 2A is necessary for its recruitment to the plasma membrane. FASEB J 2006;20:2618–2620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ridge K, Rutschman D, Factor P, Katz A, Bertorello A, Sznajder J. Differential expression of Na-K-ATPase isoforms in rat alveolar epithelial cells. Am J Physiol 1997;273:L246–L255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Efendiev R, Bertorello AM, Pressley TA, Rousselot M, Feraille E, Pedemonte CH. Simultaneous phosphorylation of ser11 and ser18 in the α1-subunit promotes the recruitment of Na+,K+-ATPase molecules to the plasma membrane. Biochemistry 2000;39:9884–9892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Canfield VA, Norbeck L, Levenson R. Localization of cytoplasmic and extracellular domains of na,k-atpase by epitope tag insertion. Biochemistry 1996;35:14165–14172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gottardi CJ, Dunbar LA, Caplan MJ. Biotinylation and assessment of membrane polarity: caveats and methodological concerns. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 1995;268:F285–F295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Akhter S, Cavet ME, Tse C-M, Donowitz M. C-terminal domains of Na+/H+ exchanger isoform 3 are involved in the basal and serum-stimulated membrane trafficking of the exchanger. Biochemistry 2000;39:1990–2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ridge KM, Dada L, Lecuona E, Bertorello AM, Katz AI, Mochly-Rosen D, Sznajder JI. Dopamine-induced exocytosis of Na,K-ATPase is dependent on activation of protein kinase C-epsilon and -delta. Mol Biol Cell 2002;13:1381–1389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gorvel JP, Chavrier P, Zerial M, Gruenberg J. Rab5 controls early endosome fusion in vitro. Cell 1991;64:915–925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hammond TG, Verroust PJ, Majewski RR, Muse KE, Oberley TD. Heavy endosomes isolated from the rat cortex show attributes of intermicrovillar clefts. Am J Physiol 1994;267:F516–F527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fallon RF, Goodenough DA. Five-hour half-life of mouse liver gap-junction protein. J Cell Biol 1981;90:521–526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Misumi Y, Misumi Y, Miki K, Takatsuki A, Tamura G, Ikehara Y. Novel blockade by brefeldin A of intracellular transport of secretory proteins in cultured rat hepatocytes. J Biol Chem 1986;261:11398–11403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nebenfuhr A, Ritzenthaler C, Robinson DG. BrefeldinA: deciphering an enigmatic inhibitor of secretion. Plant Physiol 2002;130:1102–1108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chibalin AV, Pedemonte CH, Katz AI, Feraille E, Berggren PO, Bertorello AM. Phosphorylation of the catalytic α-subunit constitutes a triggering signal for Na+,K+-ATPase endocytosis. J Biol Chem 1998;273:8814–8819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sweeney G, Niu W, Canfield VA, Levenson R, Klip A. Insulin increases plasma membrane content and reduces phosphorylation of Na+-K+ pump alpha 1-subunit in HEK-293 cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2001;281:C1797–C1803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Feschenko MS, Sweadner KJ. Structural basis for species-specific differences in the phosphorylation of Na,K-ATPase by protein kinase C. J Biol Chem 1995;270:14072–14077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thevenod F, Friedmann JM. Cadmium-mediated oxidative stress in kidney proximal tubule cells induces degradation of Na+/K+-ATPase through proteasomal and endo-/lysosomal proteolytic pathways. FASEB J 1999;13:1751–1761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Feng Y, Press B, Wandinger-Ness A. Rab 7: An important regulator of late endocytic membrane traffic. J Cell Biol 1995;131:1435–1452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meresse S, Gorvel JP, Chavrier P. The rab7 GTPase resides on a vesicular compartment connected to lysosomes. J Cell Sci 1995;108:3349–3358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lecuona E, Trejo H, Sznajder J. Regulation of Na,K-ATPase during acute lung injury. J Bioenerg Biomembr 2007;39:391–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hicke L. Ubiquitin-dependent internalization and down-regulation of plasma membrane proteins. FASEB J 1997;11:1215–1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hicke L, Dunn R. Regulation of membrane protein transport by ubiquitin and ubiquitin-binding proteins. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 2003;19:141–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bradley ME, Azuma KK, McDonough AA, Mircheff AK, Wood RL. Surface and intracellular pools of Na,K-ATPase catalytic and immuno-activities in rat exorbital lacrimal gland. Exp Eye Res 1993;57:403–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bradley M, Lambert R, Mircheff A. Isolation and identification of plasma membrane populations. Methods Enzymol 1994;228:432–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chibalin AV, Ogimoto G, Pedemonte CH, Pressley TA, Katz AI, Feraille E, Berggren PO, Bertorello AM. Dopamine-induced endocytosis of Na+,K+-ATPase is initiated by phosphorylation of ser-18 in the rat α subunit and is responsible for the decreased activity in epithelial cells. J Biol Chem 1999;274:1920–1927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Efendiev R, Das-Panja K, Cinelli AR, Bertorello AM, Pedemonte CH. Localization of intracellular compartments that exchange Na,K-ATPase molecules with the plasma membrane in a hormone-dependent manner. Br J Pharmacol 2007;151:1006–1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lecuona E, Ridge K, Pesce L, Batlle D, Sznajder JI. The GTP-binding protein RhoA mediates Na,K-ATPase exocytosis in alveolar epithelial cells. Mol Biol Cell 2003;14:3888–3897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Azzam ZS, Adir Y, Crespo A, Comellas A, Lecuona E, Dada LA, Krivoy N, Rutschman DH, Sznajder JI, Ridge KM. Norepinephrine increases alveolar fluid reabsorption and Na,K-ATPase activity. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2004;170:730–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lescale-Matys L, Putnam DS, McDonough AA. Na(+)-K(+)-ATPase alpha 1- and beta 1-subunit degradation: evidence for multiple subunit specific rates. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 1993;264:C583–C590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yoshimura SH, Takeyasu K. Differential degradation of the Na+/K+-ATPase subunits in the plasma membrane. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2003;986:378–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chibalin AV, Katz AI, Berggren PO, Bertorello AM. Receptor-mediated inhibition of renal Na+-K+-ATPase is associated with endocytosis of its α- and β- subunits. Am J Physiol 1997;273:C1458–C1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ridge KM, Olivera WG, Saldias F, Azzam Z, Horowitz S, Rutschman DH, Dumasius V, Factor P, Sznajder JI. Alveolar type 1 cells express the α2 Na,K-ATPase which contributes to lung liquid clearance. Circ Res 2003;92:453–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kazanietz MG, Caloca MJ, Aizman O, Nowicki S. Phosphorylation of the catalytic subunit of rat renal Na+,K+-ATPase by classical PKC isoforms. Arch Biochem Biophys 2001;388:74–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Khundmiri SJ, Bertorello AM, Delamere NA, Lederer ED. Clathrin-mediated endocytosis of Na+,K+-ATPase in response to parathyroid hormone requires ERK-dependent phosphorylation of ser-11 within the α1-subunit. J Biol Chem 2004;279:17418–17427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen Z, Krmar RT, Dada L, Efendiev R, Leibiger IB, Pedemonte CH, Katz AI, Sznajder JI, Bertorello AM. Phosphorylation of adaptor protein-2 μ2 is essential for Na+,K+-ATPase endocytosis in response to either G protein-coupled receptor or reactive oxygen species. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2006;35:127–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Melikova MS, Kondratov KA, Kornilova ES. Two different stages of epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptor endocytosis are sensitive to free ubiquitin depletion produced by proteasome inhibitor MG132. Cell Biol Int 2006;30:31–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shen Y, Hirsch DS, Sasiela CA, Wu WJ. CDC42 regulates E-cadherin ubiquitination and degradation through an epidermal growth factor receptor to src-mediated pathway. J Biol Chem 2008;283:5127–5137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]