Abstract

Cholecystectomy has been widely performed in the treatment of acute cholecystitis, and laparoscopic cholecystectomy has been increasingly adopted as the method of surgery over the past 15 years. Despite the success of laparoscopic cholecystectomy as an elective treatment for symptomatic gallstones, acute cholecystitis was initially considered a contraindication for laparoscopic cholecystectomy. The reasons for it being considered a contraindication were the technical difficulty of performing it in acute cholecystitis and the development of complications, including bile duct injury, bowel injury, and hepatic injury. However, laparoscopic cholecystectomy is now accepted as being safe for acute cholecystitis, when surgeons who are expert at the laparoscopic technique perform it. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy has been found to be superior to open cholecystectomy as a treatment for acute cholecystitis because of a lower incidence of complications, shorter length of postoperative hospital stay, quicker recuperation, and earlier return to work. However, laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis has not become routine, because the timing and approach to the surgical management in patients with acute cholecystitis is still a matter of controversy. These Guidelines describe the timing of and the optimal surgical treatment of acute cholecystitis in a question-and-answer format.

Key words: Acute cholecystitis, Cholecystectomy, Laparoscopic cholecystectomy, Open surgery, Cholecystostomy, Guidelines

Introduction

Cholecystectomy has been widely accepted as an effective treatment for acute cholecystitis. Several studies conducted during the era of open cholecystectomy demonstrated the advantages of early cholecystectomy for patients with acute cholecystitis — its safety, cost-effectiveness, and the rapid return of the patient to normal activity (level 1b).1–3 Although acute cholecystitis had initially been considered a contraindication to laparoscopic cholecystectomy because of the higher incidence of complications than in non-acute cholecystitis (level 2b),4 as a result of the mastery of the required skills by surgeons and the improvements in laparoscopic instruments, laparoscopic cholecystectomy is now accepted as safe when surgeons who are expert in laparoscopic techniques perform it. Some recent randomized clinical trials (level 1b)5–9 have addressed the timing and surgical approach to the gallbladder in patients with acute cholecystitis, and the results have indicated that laparoscopic cholecystectomy was associated with a shorter hospital stay, more rapid recovery, and a reduction in the overall cost of treatment, and that early laparoscopic cholecystectomy was sufficiently safe to be performed routinely.

Nevertheless, urgent or early laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystits seems to remain unpopular, and the reasons for its unpopularity include a lack of availability of surgeons who have mastered the necessary skills, as well as the limited availability of operating room space (level 2c).10,11

Critically ill patients with acute cholecystitis often present a difficult therapeutic dilemma. Although they require emergency surgical intervention, many such patients have a serious medical or surgical complication and may be too ill to undergo open or laparoscopic cholecystectomy under general anesthesia. By avoiding the risks of cholecystectomy, drainage by cholecystostomy offers a distinct advantage in such critically ill patients, but the optimal timing of subsequent surgery has not been examined. These Guidelines describe the timing and optimal type of surgical treatment for acute cholecystitis in a question-and-answer format.

Q1. When is the optimal time for cholecystectomy in acute cholecystitis?

Cholecystectomy is preferable early after admission (recommendation A).

Randomized controlled trials in the open cholecystectomy era, comparing early surgery with delayed surgery in the 1970s–1980s, found that early surgery had the advantages of less blood loss, a shorter operation time, a lower complication rate, and a briefer hospital stay (level 1b)1–3,12 (level 3b).13

Some recent randomized clinical trials (level 1b)5–9 have addressed the timing of and surgical approach to the gallbladder in patients with acute cholecystitis, and the results have indicated that laparoscopic cholecystectomy performed during the first admission was associated with a shorter hospital stay, quicker recovery, and reduction in overall cost of treatment compared to open cholecystectomy. Early laparoscopic cholecystectomy is now accepted to be sufficiently safe for routine use, because earlier reports of increased risk of bile duct injury (level 4)14 have not been substantiated by more recent experience (level 1b).5,7,8,15

The results of a randomized controlled trial comparing early laparoscopic cholecystectomy after admission with delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy showed that performing the surgery early was superior in terms of a lower conversion rate to open surgery and shorter total hospital stay (Table 1). These results indicate that early laparoscopic cholecystectomy is preferable in patients with acute cholecystitis.

Table 1.

Comparisons of early and delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis

| Author | Number of patients | Conversion rate of early LC | Conversion rate of delayed LC | Postoperative complications of early LC | Length of Postoperative complications of delayed LC | Length of hospital stay (days) Early surgery | hospital stay (days) Delayed surgery |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lo et al.5 | 86 | 11% | 23% | 13% | 29% | 6 | 11 |

| Lai et al.6 | 91 | 21% | 24% | 9% | 8% | 7.6 | 11.6 |

| Chandler et al.7 | 43 | 24% | 36% | 4% | 9% | 5.4 | 7.1 |

| Johansson et al.15 | 143 | 31% | 29% | 18% | 10% | 5 | 8 |

LC, laparoscopic cholecystectomy; conversion rate, conversion rate to open surgery

However, the fact that the above trials excluded patients with pan-peritonitis caused by perforation of the gallbladder, patients with common bile duct stones, and those with concomitant severe cardiopulmonary disease should be borne in mind when evaluating the results.

After evaluation of patients’ overall condition and confirmation of the diagnosis by ultrasonography, computed tomography (CT), and/or magnetic resonance cholargio-parcreatography (MRCP), the timing of the surgical management of acute cholecystitis patients should be immediately decided by experienced surgeons (level 5).16

Outcome of the Tokyo Consensus Meeting

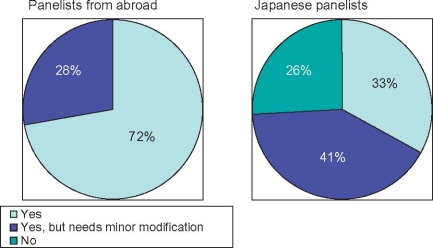

The panelists voted on the timing of cholecystectomy in patients with grade 1 (mild) and 2 (moderate) acute cholecystitis. The results showed that 72% of doctors from abroad and 33% of Japanese doctors agreed with early cholecystectomy, but 28% of the doctors from abroad and 41% of the Japanese doctors voted that minor modification of the guideline was needed, and none of the doctors from abroad and 26% of Japanese doctors disagreed with early timing (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Timing of cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis. Votes on the proposed guideline: cholecystectomy is preferable early after admission

Q2. Which surgical procedure should be adopted, laparoscopic cholecystectomy or open cholecystectomy?

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is preferable to open cholecystectomy (recommendation A).

Cholecystectomy has been widely performed to treat acute cholecystitis, with laparoscopic cholecystectomy having been increasingly adopted over the past 10 years. Several reports of complications associated with early laparoscopic cholecystectomy caused a transient wane in the enthusiasm for early laparoscopic cholecystectomy (level 4),14 (level 2b),17 (level 4),18,19 but such concerns were allayed by evidence indicating that early laparoscopic cholecystectomy for patients with acute cholecystitis was safe and effective, and required a shorter hospitalization time (level 1b)8,9 (level 2b)20,21 (level 3b)22 (level 4).23 Thus, increased experience with laparoscopic surgery has led to laparoscopic cholecystectomy becoming as good as, or safer than, open cholecystectomy for the treatment of acute cholecystitis (level 1b).8 Although early cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis has remained unpopular (level 2c),10,11 if early cholecystectomy is performed early laparoscopic cholecystectomy is the preferable procedure.

Because the set of skills required for laparoscopic cholecystectomy is different from the set required for conventional open cholecystectomy, only surgeons who possess that set of skills in laparoscopic cholecystectomy should perform it. The surgeon should be aware of the complications (described later in Q4) that have been associated with the laparoscopic procedure and should take maximum care to prevent bile duct injury, which sometimes lead to serious complications. The surgeon should never hesitate to convert to open cholecystectomy to prevent severe complications, if the anatomy of Calot’s triangle remains unclear despite accurate dissection.

Decompression of an acutely inflamed gallbladder may not only allow the patient time to recover from the acute illness prior to surgery, but may decrease the technical difficulty of cholecystectomy. Open cholecystostomy under local anesthesia is a traditional practice that provides an alternative to cholecystectomy in critically ill patients with acute cholecystitis (level 4),24 but percutaneous cholecystostomy has now become a valuable alternative procedure for decompressing an acutely inflamed gallbladder.

Out come of the Tokyo Consensus Meeting

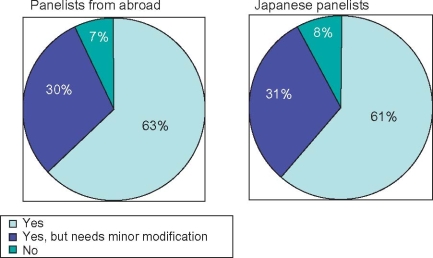

Voting for “laparoscopic cholecystectomy is preferable to open cholecystectomy” showed that 63% of the doctors from abroad and 61% of the Japanese doctors agreed with this; 30% of the doctors from abroad and 31% of the Japanese doctors voted that they agreed, but that minor modification of the guideline was needed; while 7% of the doctors from abroad and 8% of the Japanese doctors disagreed (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Surgical procedure for the treatment of acute cholecystitis. Votes on the proposed guideline: laparoscopic cholecystectomy is preferable to open cholecystectomy

Q3. What is the optimal surgical treatment for acute cholecystitis according to grade of severity?

Mild (grade I) acute cholecystitis: early laparoscopic cholecystectomy is the preferred procedure.

Moderate (grade II) acute cholecystitis: early cholecystectomy is performed. However, if patients have severe local inflammation, early gallbladder drainage (percutaneous or surgical) is indicated. Because early cholecystectomy may be difficult, medical treatment and delayed cholecystectomy are necessary.

Severe (grade III) acute cholecystitis: urgent management of organ dysfunction and management of severe local inflammation by gallbladder drainage and/or cholecystectomy should be carried out. Delayed elective cholecystectomy should be performed later, when cholecystectomy is indicated.

Treatment of acute cholecystitis essentially consists of early cholecystectomy, and the optimal surgical treatment for each grade of severity of acute cholecystitis is required. Early laparoscopic cholecystectomy is indicated for patients with mild (grade I) acute cholecystitis, because laparoscopic cholecystectomy can be performed in most these patients. Early laparoscopic or open cholecystectomy (within 72 h of the onset of acute cholecystitis) is generally required for patients with moderate (grade II) acute cholecystitis, but in some patients with moderate (grade II) acute cholecystitis, it is difficult to remove the gallbladder surgically, because of severe inflammation limited to the gallbladder. The severe local inflammation of the gallbladder is evaluated according to factors such as more than 72 h from the onset, wall thickness of the gallbladder of more than 8 mm, and a WBC count of more than 18 000. Continuous medical treatment or drainage of the contents of a swollen gallbladder by percutaneous transhepatic gallbladder drainage (PTGBD) or surgical cholecystostomy is the optimal treatment, with delayed cholecystectomy indicated after the inflammation of the gallbladder resolves. Urgent management of severe (grade III) acute cholecystitis is always necessary, because the patients have organ dysfunction, and drainage of the gallbladder contents and/or cholecystectomy is required to treat the severe inflammation of the gallbladder. Urgent or early cholecystectomy is required after improvement of patient’s general condition.

Q4. What are the complications of laparoscopic cholecystectomy to be avoided?

Bile duct injury and injury of other organs.

Complications of laparoscopic cholecystectomy were reported soon after its introduction, and consist of bile duct injury, bowel injury, and hepatic injury, as well as the common complications of conventional open cholecystectomy, such as wound infection, ileus, intraperitoneal hemorrhage, atelectasis, deep vein thrombosis, and urinary tract infection. Bile duct injury is considered a serious complication. Bowel and hepatic injuries should be avoided as they are also serious complications (level 2b).25 These injuries have been attributable to the limitations of laparoscopy, such as the narrow view and the lack of tactile manipulation. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy has not always been associated with a higher incidence of complications than open cholecystectomy, but any serious complication that requires reoperation and prolonged hospitalization may become a serious problem for patients who firmly believe that laparoscopic cholecystectomy is less invasive. The incidence of biliary injury has recently decreased in association with the acquisition of greater surgical skills and the improvements in laparoscopic instruments.

Q5. When is the optimal time for conversion from laparoscopic to open cholecystectomy?

To prevent injuries, surgeons should never hesitate to convert to open surgery when they experience difficulty in performing laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

There is a relatively high rate of conversion from laparoscopic cholecystectomy to open cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis because of technical difficulties, and laparoscopic cholecystectomy is associated with a high complication rate (level 3b).22 Although certain pre operative factors, such as male sex, previous abdominal surgery, presence or history of jaundice, advanced cholecystitis, and infectious complications are associated with a need for conversion from laparoscopic to open cholecystectomy, they have limited predictive ability (level 3b).22,26,27 Surgeons find factors that lead them to decide whether to convert to open cholecystectomy mostly during the laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Not only the experience of the surgeon but also the experience of the institution with laparoscopic cholecystectomy is a prerequisite for successful cholecystectomy for all patients with acute cholecystitis.

Because conversion to open cholecystectomy is not disadvantageous for patients, to prevent intraoperative accidents and postoperative complications, surgeons should never hesitate to convert when they experience difficulty in performing laparoscopic cholecystectomy. A low threshold for conversion to open cholecystectomy is important to minimize the risk of major complications.

Q6. When is the optimal time for cholecystectomy following PTGBD?

Early cholecystectomy during the initial hospital stay is preferable (recommendation B).

There have been no randomized controlled trials of surgical management in patients with acute cholecystitis after PTGBD. However, PTGBD is known to be an effective option in critically ill patients, especially in elderly patients and patients with complications (level 4).28 Cholecystectomy is often performed at an interval of several days following PTGBD. Early cholecystectomy following PTGBD is preferable when the patient’s condition improves, and if the patient has no complications. Complications of PTGBD, such as intrahepatic hematoma, pericholecystic abscess, biliary pleural effusion, and biliary peritonitis (which may be caused by puncture of the liver and migration of the catheter) sometimes occur (level4)29 and efforts should be made to prevent such occurrences. More case-series studies are required.

Q7. When is the optimal time for laparoscopic cholecystectomy after endoscopic stone extraction in patients with cholecysto-choledocholithiasis?

Early cholecystectomy following endoscopic stone extraction during the same hospital stay is preferable (recommendation B).

Combining endoscopic stone extraction during endoscopic retrograde cholangiography with laparoscopic cholecystectomy has been found to be a useful means of treating patients with cholecysto-choledocholithiasis. However, the optimal time for laparoscopic cholecystectomy following endoscopic stone extraction (ESE) is still a matter of controversy. There have been several reports of combinations of ESE and laparoscopic cholecystectomy (level 2b),30 (level4),31–33 and in most of them, the interval between the two procedures was a few days. Actually, the interval between ESE and laparoscopic cholecystectomy was left to the individual surgeon. At present, early laparoscopic cholecystectomy following ESE during the same hospital stay is regarded as preferable in most patients without complications related to ESE.

Discussion at the Tokyo Consensus Meeting

Severity of acute cholecystitis

There has been some high-quality evidences obtained by randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in the field of surgical treatment for acute cholecystitis. However, no RCTs have examined the optimal surgical treatment for acute cholecystitis according to grade of severity. The need for surgical treatment according to grade of severity was suggested by panelists, and surgical treatment strategies were discussed.

Steven Strasberg (USA) proposed grading the severity of acute cholecystitis as mild (grade I), moderate (grade II), and severe (grade III).

Early cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis

There were some important remarks in the discussion of the concept that early cholecystectomy during the first admission is preferable. These remarks were that: (a) it is necessary to know whether the numbers of patients in the RCTs were sufficient to evaluate the incidence of serious complications such as bile duct injury, (b) it is important to know whether all of the surgeons who performed cholecystectomy in the RCTs possessed the skills for laparoscopic surgery, (c) “early cholecys tectomy” was not defined in any of the RCTs, (d) surgical treatments for acute cholecystitis of each grade of severity should be stated individually in these Guidelines.

On the basis of these remarks, the panelists voted on the timing of cholecystectomy in patients with mild (grade I) and moderate (grade II) acute cholecystitis. None of the doctors from abroad disagreed with early cholecystectomy. In contrast, 26% of the Japanese doctors disagreed with it. Thus, the results of the votes of the doctors from abroad and the Japanese doctors differed.

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis

There were some important remarks in the discussion of the concept that laparoscopic cholecystectomy was superior to open cholecystectomy. They were: (a) laparoscopic cholecystectomy is associated with a greater risk of bile duct injury, (b) laparoscopic cholecystectomy should be performed by experienced surgeons, and (c) the majority of acute cholecystitis patients treated surgically have mild (grade I) acute cholecystitis.

The vote on the cholecystectomy procedure was performed on the basis of the above remarks. Voting for “laparoscopic cholecystectomy is preferable to open cholecystectomy” showed that approximately 60% of both Japanese and overseas doctors agreed, and approximately 30% of both groups of doctors voted that they agreed, but that minor modification of the guideline was needed; only a few percent of both groups of doctors disagreed. Thus, laparoscopic cholecystectomy for mild (grade I) and moderate (grade II) acute cholecystitis, except in patients with localized severe inflammation of the gallbladder, was approved of by many doctors in both groups.

Cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis

The results of the voting on the timing and surgical procedure for mild (grade I) and moderate (grade II) acute cholecystitis are described above. There was an important remark during the discussion, that patients in whom it is difficult to remove the gallbladder are frequently encountered among patients with moderate (grade II) acute cholecystitis, and that removal of the gallbladder, especially by laparoscopic cholecystectomy, is difficult in such patients. This remark was agreed with by many panelists at the Meeting, and it was concluded that if patients have severe local inflammation of the gallbladder, early gallbladder drainage (percutaneous or surgical) is the initial treatment of choice. Because early cholecystectomy may be difficult, medical treatment and delayed cholecystectomy are performed.

The fact that there was a consensus among the doctors from abroad and Japanese doctors concerning the surgical treatment strategy for moderate (grade II) acute cholecystitis facilitated the drafting of the Guideline.

Acknowledgment

We would like to express our deep gratitude to the Japanese Society for Abdominal Emergency Medicine, the Japan Biliary Association, and the Japanese Society of Hepato-Biliary-Pancreatic Surgery, who provided us with great support and guidance in the preparation of the Guidelines. This process was conducted as part of the Project on the Preparation and Diffusion of Guidelines for the Management of Acute Cholangitis (H-15-Medicine-30), with a research subsidy for fiscal 2003 and 2004 (Integrated Research Project for Assessing Medical Technology) sponsored by the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare.

We also truly appreciate the panelists who cooperated with and contributed significantly to the International Consensus Meeting, held in Tokyo on April 1 and 2, 2006.

References

- 1.Lahtinen J, Alhava EM, Aukee S. Acute cholecystitits treated by early and delayed surgery. A controlled clinical trial. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1978;13:673–8. doi: 10.3109/00365527809181780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jarvinen HJ, Hastbacka J. Early cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis: a prospective randomized study. Ann Surg. 1980;191:501–5. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198004000-00018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Norrby S, Herlin P, Holmin T, Sjodahl R, Tagesson C. Early or delayed cholecystectomy in acute cholecystitis? A clinical trial. Br J Surg. 1983;70:163–5. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800700309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cushieri A, Dubois F, Mouiel J, Mouiel P, Becker H, Buess G, et al. The European experience with laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Am J Surg. 1991;161:385–7. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(91)90603-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lo CM, Cl Liu, Fan ST, Lai EC, Wong J. Prospective randomized study of early versus delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis. Am Surg. 1998;227:461–7. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199804000-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lai PB, Kwong KH, Leung KL, Kwok SP, Chan AC, Chung SC. Randomized trial of early versus delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis. Br J Surg. 1998;85:764–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1998.00708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chandler CF, Lane JS, Ferguson P, Thonpson JE. Prospective evaluation of early versus delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy for the treatment of acute cholecystitis. Am Surg. 2000;66:896–900. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kiviluoto T, Siren J, Luukkonen P, Kivilaakso E. Randomized trial of laparoscopic versus open cholecystectomy for acute and gangrenous cholecystitis. Lancet. 1998;351:321–325. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)08447-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berrgren U, Gordh T, Grama D, Haglund U, Rastad J, Arvidsson D. Laparoscopic versus open cholecystectomy: hospitalization, sick leave, analgesia and trauma responses. Br J Surg. 1994;81:1362–5. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800810936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Senapati PSP, Bhattarcharya D, Harinath G, Ammori BJ. A survey of the timing and approach to the surgical management of cholelithiasis in patients with acute biliary pancreatitis and acute cholecystitis in the UK. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2003;85:306–12. doi: 10.1308/003588403769162404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cameron IC, Chadwick C, Phillips J, Johnson AG. Management of acute cholecystitis in UK hospitals: time for a charge. Postgrad Med J. 2004;80:292–4. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2002.004085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van der Linden W, Sunzel H. Early versus delayed operation for acute cholecystitis. A controlled clinical trial. Am J Surg. 1970;120:7–13. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(70)80133-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van der Linden W, Edlund G. Early versus delayed cholecystectomy: the effect of a change in management. Br J Surg. 1981;68:753–7. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800681102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kum CK, Eypasch E, Lefering R, Math D, Paul A, Neugebauer E, et al. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis: is it really safe? World J Surg. 1996;20:43–9. doi: 10.1007/s002689900008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johansson M, Tbune A, Blomqvist A, Nelvin L, Lundell L. Management of acute cholecystitis in the laparoscopic era: results of a prospective, randomized clinical trial. J Gastrointest Surg. 2003;7:642–5. doi: 10.1016/S1091-255X(03)00065-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mason GR. Acute cholecystitis; surgical aspects. Berk JE, editor. 4th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1985. p.3616–18. (level 5)

- 17.Russell JC, WaIsh SJ, Mattie AS, Lynch JT. Bile duct injuries, 1989–993. A statewide experience. Arch Surg. 1996;131:382–8. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1996.01430160040007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Branum G, Schmtt C, Baillie J. Management of major biliary complications after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Ann Surg. 1993;217:532–40. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199305010-00014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bender JS, Zenilman ME. Immediate laparoscopic cholecystectomy as definitive therapy for acute cholecystitis. Surg Endosc. 1995;9:1081–8. doi: 10.1007/BF00188991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zacks SL, Sandler RS, Rutledge R, Brown RS. A population-based cohort study comparing laparoscopic cholecystectomy and open cholecystectomy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:334–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Flowers JL, Bailey RW, Scovill WA, Zucker KA. The Baltimore experience with laparoscopic management of acute cholecystitis. Am J Surg. 1991;161:388–92. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(91)90604-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eldar S, Sabo E, Nash E, Abrahamson J, Matter I. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis: prospective trial. World J Surg. 1997;21:540–5. doi: 10.1007/PL00012283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cox MR, Wilson TG, Luck AJ, Leans PL, Padbury RTA, Toouli J. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute inflammation of the gallbladder. Ann Surg. 1993;218:630–4. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199321850-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Glenn F. Cholecystostomy in the high risk patient with biliary tract disease. Ann Surg. 1977;185:185–91. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197702000-00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.The Southern Surgeons Club A prospective analysis of 1518 laparoscopic cholecystectomies. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:1073–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199104183241601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brodsky A, Matter I, Sabo E, Cohen A, Abrahamson J, Eldar S. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis: can the need for conversion and the probability of complications be predicted? Surg Endosc. 2000;14:755–60. doi: 10.1007/s004640000182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kama NA, Doganay M, Dolapci E, Reis E, Ati M, Kologlu M. Risk factors resulting in conversion of laparoscopic cholecystectomy to open surgery. Surg Endosc. 2001;15:965–8. doi: 10.1007/s00464-001-0008-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tseng LJ, Tsai CC, Mo LR, Lin RC, Kuo JY, Chang KK, et al. Palliative percutaneous transhepatic gallbladder drainage of gallbladder empyema before laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Hepato gastroenterology. 2000;47:932–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kivinen H, Makela JT, Autio R, Tikkakoski T, Leinonen S, Siniluoto T, et al. Percutaneous cholecystostomy in acute cholecystitis in high-risk patients: an analysis of 69 patients. Int Surg. 1998;83:299–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cuschieri A, Crose E, Faggioni A, Jakimowicz J, Lacy A, Lezoche E, et al. EAES ductal stone study. Preliminary findings of multi-center prospective randomized trial comparing two-stage vs single-stage management. Surg Endosc. 1996;10:1130–5. doi: 10.1007/s004649900262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sarli L, Iusco DR, Roncoroni L. Preoperative endoscopic sphincterotomy and laparoscopic cholecystectomy for the management of cholecystocholedocholithiasis: 10-year experience. World J Surg. 2003;27:180–6. doi: 10.1007/s00268-002-6456-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Basso N, Pizzuto G, Surgo D, Materia A, Silecchia G, Fantini A, et al. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy and intraoperative endoscopic sphincterotomy in the treatment of cholecysto-choledocholithiasis. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50:532–5. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5107(99)70078-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cemachovic I, Letard JC, Begin GF, Rousseau D, Nivet LM. Intraoperative endoscopic sphincterotomy is a reasonable option for complete single-stage minimally invasive biliary stone treatment: short-term experience with 57 patients. Endoscopy. 2000;32:956–62. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-9622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]