Abstract

Biliary decompression and drainage done in a timely manner is the cornerstone of acute cholangitis treatment. The mortality rate of acute cholangitis was extremely high when no interventional procedures, other than open drainage, were available. At present, endoscopic drainage is the procedure of first choice, in view of its safety and effectiveness. In patients with severe (grade III) disease, defined according to the severity assessment criteria in the Guidelines, biliary drainage should be done promptly with respiration management, while patients with moderate (grade II) disease also need to undergo drainage promptly with close monitoring of their responses to the primary care. For endoscopic drainage, endoscopic nasobiliary drainage (ENBD) or stent placement procedures are performed. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have reported no difference in the drainage effect of these two procedures, but case-series studies have indicated the frequent occurrence of hemorrhage associated with endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST), and complications such as pancreatitis. Although the usefulness of percutaneous transhepatic drainage is supported by the case-series studies, its lower success rate and higher complication rates makes it a second-option procedure.

Key words: Cholangitis, Endoscopic sphincterotomy, Biliary drainage, Percutaneous, Endoscopy, Endoscopic cholangiopancreatography, Guidelines

Introduction

Acute cholangitis may progress rapidly to a severe form, particularly in the elderly, and the severe form often results in a high mortality (level 4).1–3 When Reynolds and Dargan1 published their report, surgical operation was the only available treatment, and the mortality rate was steep. Even now, when the mortality rate has declined, due to the ubiquitous application of endoscopic and percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage, acute cholangitis can be fatal unless it is treated in a timely way. Although endoscopic drainage is less invasive than other drainage techniques and should be considered as the drainage technique of first choice (level 2b),4 details of its procedures remain controversial. This article outlines various biliary drainage techniques, especially in regard to endoscopic procedures.

Techniques of endoscopic biliary drainage

Transpapillary biliary drainage for acute cholangitis is based on selective cannulation into the bile duct with endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). However, as these drainage procedures are different in regard to: (i) the additional application of endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST), and (ii) the selection of either endoscopic nasobiliary drainage (ENBD) or stent placement, they are explained below in detail.

ERCP

ERCP is a procedure to insert a contrast test catheter into the papilla, using a duodenal scope to visualize the bile duct. To secure a drainage route (for ENBD or stent placement), successful selective cannulation into the bile duct is essential. If cannulation deep into the bile duct is difficult, replacement of the catheter, the use of a guidewire, and precutting (by EST, explained below), are necessary. If the cannulation into the bile duct fails, other drainage, such as percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage, is necessary. Also, the quantity of contrast medium should be minimized to avoid the infusion of an excessive amount, which may exacerbate the cholangitis.

EST

Standard techniques

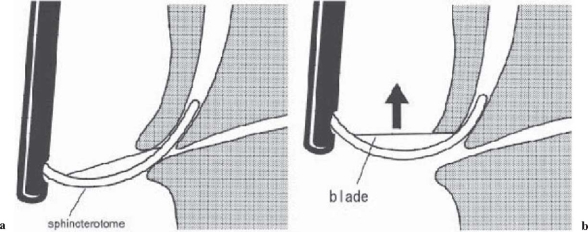

EST is a procedure used widely not only in the treatment of choledocholithiasis but also as a drainage procedure for malignant biliary obstruction. Sphincterotomes used for incision include several types such as: the pull-type (Fig. 1a,b), push-type (Fig. 2), needle type (Fig. 3) and, the shark’s fin-type, and others, each of which has a different length of exposed wire and different tip shape. The most common sphincterotome is the pull type. The pull-type sphincterotome is useful when ERCP is difficult, because the direction of the tip of the sphincterotome can be changed by adjusting the tension of the blade (Fig. 1b). The push-type and needle-type are used for difficult cases.

Fig. 1a,b.

Pull-type sphincterotome. a A pull-type sphincterotome is shown; it has various applications, and is useful for opening the bile duct. b The direction of the tip of the blade can be manipulated by pulling. The direction can usually be changed by using a guidewire

Fig. 2.

Push-type sphincterotome. The direction of the blade cannot be altered, but its length and form can be changed. It can be used for precutting

Fig. 3.

Needle-type sphincterotome. Because of the needle point, opening of the bile duct can be performed

A common EST technique is to perform a high-frequency electric surgical incision of the duodenal papilla, using a sphincterotome selectively cannulated in the bile duct (Figs. 4 and 5). In EST for drainage purposes, unlike that for stone removal, only a limited incision is necessary (level 4).5 Acute pancreatitis and cholangitis are common complications caused by EST, and the incidence of acute pancreatitis, known to become fatal once it progresses severely, depends on the skills of the endoscopist (level 1b, level 4)6,7 (Table 1).

Fig. 4a,b.

Standard techniques for endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST). a Selective cannulation of the bile duct. b A high-frequency electric surgical incision of the papilla of Vater is made with the blade

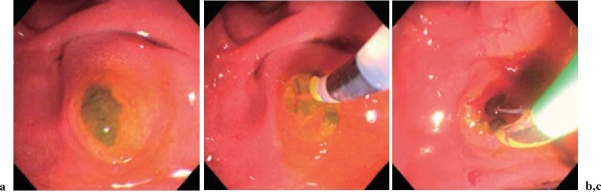

Fig. 5a–c.

Example of EST procedure. a Gallstones are visible via the duodenal papilla. b In this patient, cannulation with an endoscopic catheter resulted in resolution of the debris-like stones. c The catheter was replaced by a high-frequency electric sphincterotome

Table 1.

Complications caused by EST

Precutting techniques

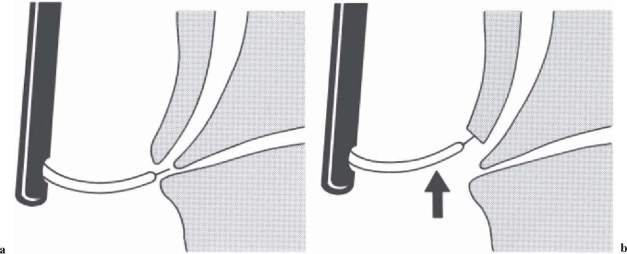

Precutting is an incision of the papilla to facilitate cannulation into the bile duct when selective cannulation is impossible. EST can be completed by a common procedure after selective cannulation into the bile duct becomes possible. The method using a needle-type sphincterotome for probing in the opening of the bile duct is common (Fig. 6), but there is also a method to incise the tips of the bile duct with a push-type or shark’s fin-type sphincterotome. The types of sphincterotome and the detailed procedures used differ depending on the medical institution. It is also known that precutting is likely to cause serious complications such as acute pancreatitis and perforation, and therefore it can be used only by skilled endoscopic surgeons (level 1b, level 4).6,7

Fig. 6a,b.

Precutting EST techniques with a needle-type sphincterotome. a Needle-knife sphincterotomy was performed, starting from the papillary orifice, cutting upward. b Incising through the wall of the major papilla is performed with the needle-knife until achieving access into the bile duct

Significance of EST in endoscopic biliary drainage

According to some case-series studies, the reasons that additional EST are not necessary in acute cholangitis are that:

The application of additional EST to drainage produces no difference in effect

the additional EST causes complications such as hemorrhage.

Acute cholangitis is one of the risk factors for post-EST hemorrhage (level 1b),6 and the use of EST in patients with severe (grade III) disease complicated by coagulopathy should be avoided. On the other hand, EST has advantages such as:

Not only drainage but also single-stage lithotomy can be employed in patients with choledocholithiasis (not complicated by severe cholangitis)

Precutting can ensure a drainage route into the bile duct in patients in whom selective cannulation is difficult.

Endoscopic drainage employed for acute cholangitis does not always require EST (level 4).8,9 However, precutting may be indispensable in performing drainage in some patients with impacted stones in the papilla of Vater, and whether or not additional EST should be conducted depends on the condition of the patient and the skills of the endoscopist. In the Guidelines, readers are reminded to be cautious when additional EST is employed.

Endoscopic biliary drainage (EBD)

Endoscopic drainage includes not only endoscopic biliary drainage (EBD) but also EST without stent insertion, which means that calculus removal can be performed with only one endoscopic procedure. EBD is of two types endoscopic nasobiliary drainage (ENBD; external drainage) and stent placement (internal drainage). No difference between these two methods was proven by past RCTs (level 2b),10,11 and the Guidelines suggest that either drainage procedure may be chosen. Internal drainage does, however, confer less electrolyte disturbance as there is no external loss of bile and its contents.

Endoscopic nasobiliary drainage (ENBD)

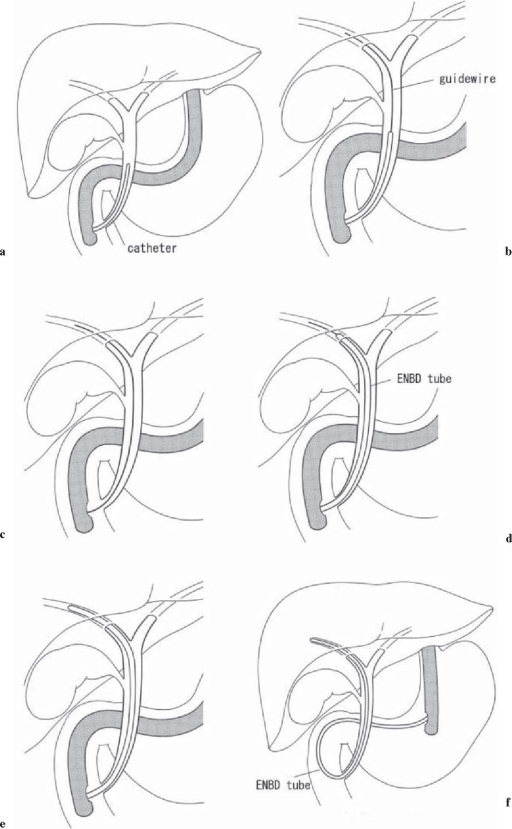

ENBD is an external drainage procedure done by placing a 5- to 7-Fr tube, using a guidewire technique, after selective cannulation into the bile duct, and it is used to complete nasobiliary drainage (Fig. 7–10). ENBD has these advantages:

No additional EST is required

Clogging in the tube (external drain) can be washed out

Bile cultures can be done

Fig. 8.

Cholangiography through ENBD tube. Many stones are seen in the bile duct. Attention should be paid: cholangiography should be performed after improvement of inflammation

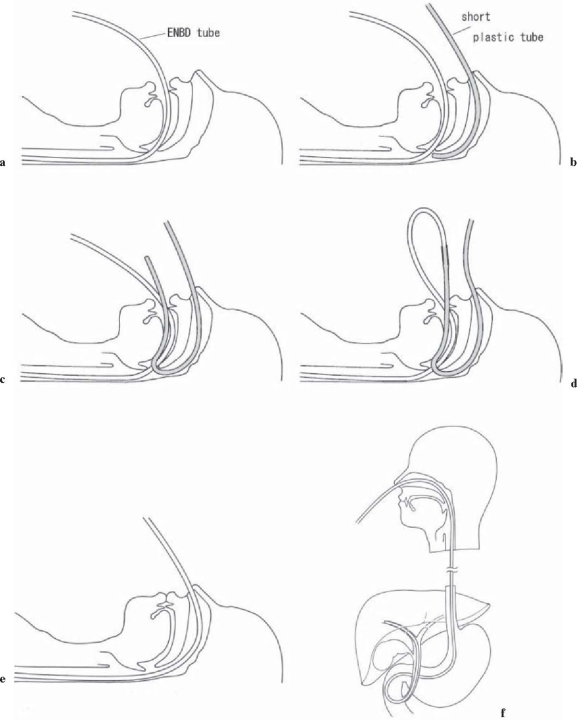

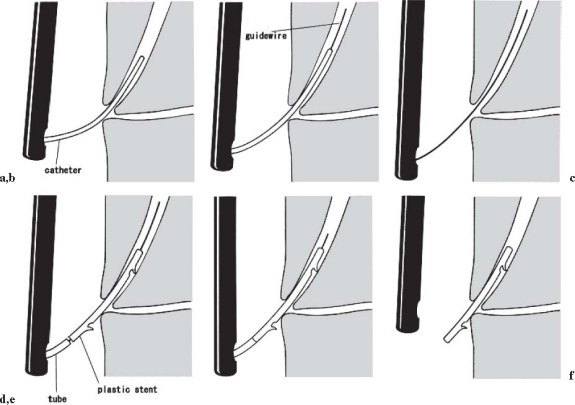

Fig. 9a-f.

ENBD procedure: part 1. a An endoscopic catheter is cannulated into the bile duct. b A guidewire is passed through the catheter into the bile duct. c The catheter is withdrawn. d The ENBD tube is passed along the guidewire. e The guidewire is withdrawn. f The endoscope is removed while applying pushing pressure on the ENBD tube to keep it in place

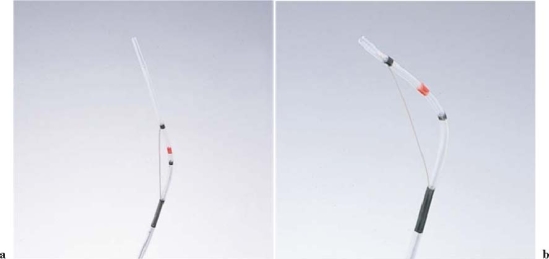

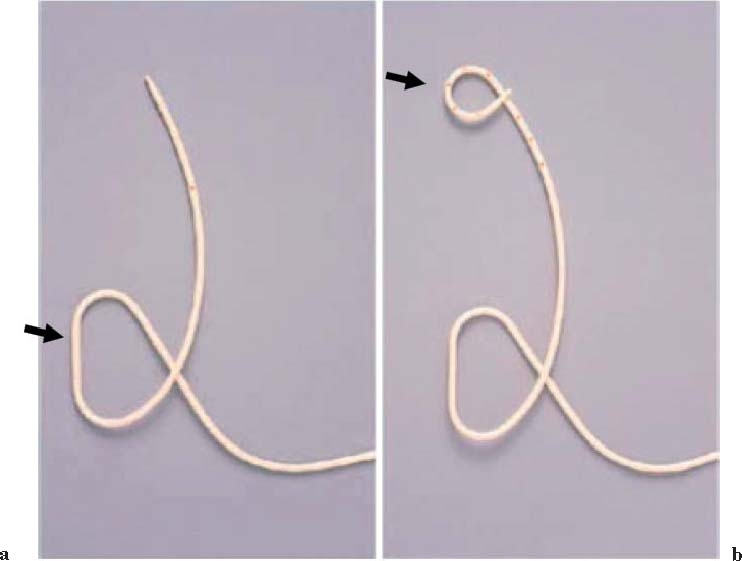

Fig. 7a,b.

Endoscopic nasobiliary drainage (ENBD) tubes. a Straight-tip tube. The leading portion of the tube is straight. A “duodenal loop” of the tube (arrow) is formed to prevent dislocation. b Pigtail-tip tube (arrow). To prevent dislodgement, the leading portion of the tube has a “pigtail”

Fig. 10a–f.

ENBD procedure: part 2. a The ENBD tube is inserted transorally. b A short plastic tube is inserted transnasally in order to engage the ENBD tube. c Surgical forceps are used to pull the leading end of the short plastic tube out orally. d The tubes are connected by inserting the end of the ENBD tube into the short plastic tube. e The short plastic tube and the connected ENBD tube are then pulled back out nasally. f A 5- to 7-French tube is used for biliary drainage via the nasal route

However, because of the patient’s discomfort from the transnasal tube placement, self-extraction and dislocation of the tube are likely to occur, especially in elderly patients. Loss of electrolytes and fluid as well as collapse of tubes by twisting, may also occur.

Additional EST must be considered for the removal of concomitant bile duct stones and viscous bile or pus in patients with suppurative cholangitis.

Plastic stent placement

Plastic stent placement is an internal drainage procedure done to place a 7- to 10-Fr plastic stent in the bile duct, using a guidewire after selective cannulation into the bile duct (Figs. 11 and 12). There are two different stent shapes, a straight type with flaps on both sides, and a pig tail type, to prevent dislocation (Fig. 13). Absence of discomfort and no loss of electrolytes or fluid relative to transnasal biliary drainage are advantages. However, as it cannot be known in real time whether the stent is patent, there is a risk of dislodgement or clogging of the stent. The other disadvantage is that when a stent with a diameter larger than 7-Fr is inserted, EST is necessary.

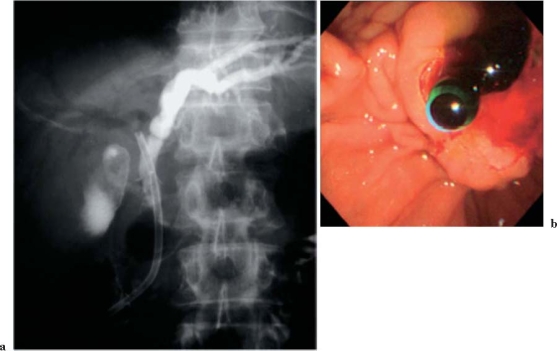

Fig. 11a–f.

Plastic stent placement (7-Fr straight plastic stent). a An endoscopic catheter is cannulated into the bile duct. b A guidewire is passed through the catheter into the bile duct. c The catheter is withdrawn. d A plastic stent is inserted along the guidewire into the bile duct by using a pusher tube. e The guidewire is removed while pushing on the pusher tube (care should be taken not to deviate from the bile duct). f The endoscope is removed, leaving the plastic stent in place

Fig. 12a,b.

Leaving the stent in place (acute cholangitis, arising from chronic pancreatitis caused by bile duct stricture). a Endoscopic cholangiography (ERC) shows the stent in place. b Endoscopic view immediately following stent placement. Bile flows to the duodenum via the stent

Fig. 13a,b.

Types of plastic stent. a Straight stent : the stent has two flaps to prevent dislocation or deviation. Should EST be required, a 10-Fr or larger stent can be used. b Pigtail stent: both ends of the stent have a “pigtail” form to prevent dislocation or deviation. Maximum stent size is 7 Fr

EST without stent insertion

EST without stent insertion can be used to remove bile duct calculi as well as for drainage. This method can shorten the hospital stay because both calculus removal and drainage are completed with only one endoscopic procedure. However, caution should be exercised, with monitoring for cholangitis due to residual calculi or sludge.

Techniques of percutaneous transhepatic cholangial drainage (PTCD)

Though there are no studies comparing percutaneous transhepatic cholangial drainage PTCD; also known as percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage; PTBD, and endoscopic drainage, PTCD should applied, in principle, to those patients who cannot undergo endoscopic drainage because of the possible serious complications of PTCD, including intraperitoneal hemorrhage and biliary peritonitis (level 4) (Table 212) and a long hospital stay. A propensity for hemorrhage is a relative contraindication, but if there is no other lifesaving method, PTCD is indicated. In view of this, the Guidelines give recommendation grades A and B to endoscopic drainage and PTCD, respectively.

Table 2.

Serious complications caused by PTCD12

| Complication | Rate |

|---|---|

| Sepsis | 2.5% |

| Hemorrhage | 2.5% |

| Localized inflammation/infection (abscess, peritonitis, cholecystitis, pancreatitis) | 1.2% |

| Pleural effusion | 0.5% |

| Death | 1.7% |

Before the widespread application of ultrasonography, a procedure to puncture the bile duct under fluoroscopic control following PCTD (level 4)13 was employed. But because it caused complications in many cases, puncture under ultrasonography is more common now (level 4).14

After ultrasound-guided transhepatic puncture of the intrahepatic bile duct is done with an 18- to 22-G needle to confirm backflow of bile, a 7- to 10-Fr catheter is placed in the bile duct under fluoroscopic control, using a guidewire (Seldinger technique). As a guidewire cannot be inserted directly when a 22-G needle is used, it is necessary to insert the guide-wire after dilating the bile duct with an elastic needle, using a steel wire. This procedure, requiring another step, is a little complicated (see Fig. 14), but puncture with a small-gauge (22-G) needle is safer in those patients without biliary dilatation. According to the Quality Improvement Guidelines produced by American radiologists, the success rates of drainage are 95% in patients with biliary dilatation and 70% in those without biliary dilatation (level 4).13

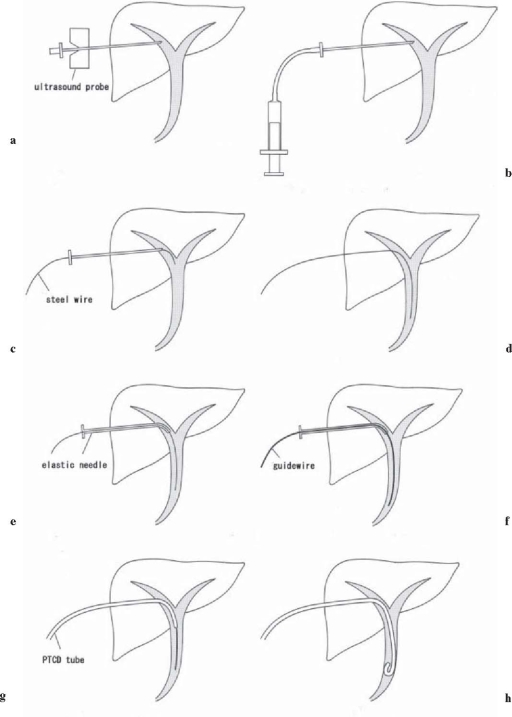

Fig. 14a–h.

Percutaneous transhepatic cholangial drainage (PTCD or PTBD [biliary]) procedure. a Under ultrasound guidance, the intrahepatic bile duct is punctured by the use of a hollow needle (external cylinder with a mandolin). b Only the mandolin is removed, and the cylinder remains. After confirming the backflow of bile, bile duct imaging is performed. c A steel wire is inserted through the cylinder. d After confirming sufficient insertion of the wire into the bile duct, the hollow needle (cylinder with the mandolin) is removed. e An elastic needle is passed over the wire. f Backflow of bile is confirmed after withdrawing the inner tube from the elastic needle. A guidewire is then inserted. g A PTCD (or PTBD) tube is passed over the guidewire. h The guidewire is withdrawn and the tube is left and fixed in place

Techniques of open drainage

Patients with acute cholangitis are preferentially treated with a noninvasive drainage procedure such as endoscopic drainage and PTCD, and only a few undergo open drainage. However, open drainage may be indicated for patients who cannot undergo such noninvasive drainage procedures, for anatomical and structural reasons, including patients after Roux-en-Y choledochojejunostomy with a propensity for hemorrhage. In open drainage, the goal is to decompress the biliary system. Simple procedures such as T-tube placement without choledocholithotomy should be recommended, because prolonged operations should be avoided in such ill patients (level 4).15

Acknowledgment

We would like to express our deep gratitude to the Japanese Society for Abdominal Emergency Medicine, the Japan Biliary Association, and the Japanese Society of Hepato-Biliary-Pancreatic Surgery, who provided us with great support and guidance in the preparation of the Guidelines. This process was conducted as part of the Project on the Preparation and Diffusion of Guidelines for the Management of Acute Cholangitis (H-15-Medicine-30), with a research subsidy for fiscal 2003 and 2004 (Integrated Research Project for Assessing Medical Technology) sponsored by the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare.

We also truly appreciate the panelists who cooper ated with and contributed significantly to the International Consensus Meeting, held in Tokyo on April 1 and 2, 2006.

References

- 1.Reynolds BM, Dargan EL. Acute obstructive cholangitis. A distinct syndrome. Ann Surg. 1959;150:299–303. doi: 10.1097/00000658-195908000-00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O’Connor MJ, Schwartz ML, McQuarrie DG, Sumer HW. Acute bacterial cholangitis: an analysis of clinical manifestation. Arch Surg. 1982;117:437–41. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1982.01380280031007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Welch JP, Donaldson GA. The urgency of diagnosis and surgical treatment of acute suppurative cholangitis. Am J Surg. 1976;131:527–32. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(76)90003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lai EC, Mok FP, Tan ES, Lo CM, Fan ST, You KT, et al. Endoscopic biliary drainage for severe acute cholangitis. N Engl J Med. 1992;24:1582–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199206113262401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boender J, Nix GA, De Ridder MA, Dees J, Schutte HE, van Buuren HR, et al. Endoscopic sphincterotomy and biliary drainage in patients with cholangitis due to common bile duct stones. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:233–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Freeman ML, Nelson DB, Sherman S, Haber GB, Herman ME, Dorsher PJ, et al. Complications of endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:909–18. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199609263351301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cotton PB, Lehman G, Vennes JA, Geenen JE, Russell RCG, Meyers WC, et al. Endoscopic sphincterotomy complications and their management : an attempt at consensus. Gastrointest Endosc. 1991;37:255–8. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(91)70740-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sugiyama M, Atomi Y. The benefits of endoscopic nasobiliary drainage without sphincterotomy for acute cholangitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:2065–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.00593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hui CK, Lai KC, Yuen MF, Ng M, Chan CK, Hu W, et al. Does the addition of endoscopic sphincterotomy to stent insertion improve drainage of the bile duct in acute suppurative cholangitis? Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:500–4. doi: 10.1067/S0016-5107(03)01871-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee DW, Chan AC, Lam YH, Ng EK, Lau JY, Law BK, et al. Biliary decompression by nasobiliary catheter or biliary stent in acute suppurative cholangitis: a prospective randomized trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:361–5. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5107(02)70039-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sharma BC, Kumar R, Agarwal N, Sarin SK. Endoscopic biliary drainage by nasobiliary drain or by stent placement in patients with acute cholangitis. Endoscopy. 2005;37:439–43. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-861054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burke DR, Lewis CA, Cardella JF, Citron SJ, Drooz AT, Haskal ZJ, et al. Society of Interventional Radiology Standards of Practice Committee Quality improvement guidelines for percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography and biliary drainage. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2003;14:243–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takada T, Hanyu F, Kobayashi S, Uchida Y. Percutaneous transhepatic cholangial drainage: direct approach under fluoroscopic control. J Surg Oncol. 1976;8:83–97. doi: 10.1002/jso.2930080113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takada T, Yasuda H, Hanyu F. Technique and management of percutaneous transhepatic cholangial drainage for treating an obstructive jaundice. Hepatogastroenterology. 1995;42:317–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saltzstein EC, Peacock JB, Mercer LC. Early operation for acute biliary tract stone disease. Surgery. 1983;94:704–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]