Abstract

Aims

In humans, genetic variation in endocannabinergic signaling has been associated with anthropometric measures of obesity. In randomized trials, pharmacological blockade at the level of the cannabinoid receptor 1 (CNR1) receptor not only facilitates weight reduction, but also improves insulin sensitivity and clinical measures of lipid homeostasis. We therefore tested the hypothesis that genetic variation in CNR1 is associated with common obesity-related metabolic disorders.

Materials & methods

A total of six haplotype tagging SNPs were selected for CNR1, using data available within the Human HapMap (Centre d’Etude du Polymorphisme Humain population) these included: two promoter SNPs, three exonic SNPs, and a single SNP within the 3′-untranslated region. These tags were then genotyped in a rigorously phenotyped family-based collection of obese study subjects of Northern European origin.

Results & conclusions

A common CNR1 haplotype (H4; prevalence 0.132) is associated with abnormal lipid homeostasis. Additional statistical tests using single tagging SNPs revealed that these associations are partly independent of body mass index.

Keywords: CNR1, genetic association, haplotype, HDL, high-density lipoprotein, LDL, low-density lipoprotein, obesity, triglyceride

The endocannabinoid (eCB) system represents an emerging therapeutic target for the treatment of obesity and obesity-related metabolic disorders. Preclinical studies clearly demonstrate that eCB signaling modulates food intake and substrate utilization at multiple sites within the body. Activation of central CB1 cannabinoid receptors can modulate the activity of satiety factors [1,2] and increase sensitivity to rewarding stimuli, including food [3,4]. Activation of CB1 receptors within adipose tissue and the liver can regulate the metabolism and storage of lipids [5]. At all of these sites, increased CB1 receptor activation can lead to excessive weight gain, insulin resistance and dyslipidemia.

Genetic variation in the CB1 receptor (CNR1) has been associated with anthropometric measures of obesity in humans (e.g., waist circumference and skin-fold thickness) [6,7]. In clinical trials, CNR1 antagonists appear to be efficacious in facilitating weight reduction [8,9]. These studies also indicate that CNR1 antagonists improve glucose homeostasis and lipid homeostasis [8,9]. The latter effects appear to occur partly independent of weight loss [8,9], suggesting that variability in the CNR1 gene may contribute to obesity-related metabolic disorders within the context of human obesity.

We tested this hypothesis using a family-based collection of 1560 individuals participating in the Take Off Pounds Sensibly (TOPS) research program in the Midwestern USA [10]. Each participating TOPS family is comprised of at least four members: one obese study subject, one obese sibling, one never-obese sibling and a parent. Our previous work with these families has led to the characterization of a number of positional candidate genes residing within genomic loci contributing to obesity [10-16]. We now report that variability in CNR1, a biological candidate gene residing outside of these loci, is associated with dyslipidemia in the same cohort. The association between lipid levels and CNR1 is partly independent of body mass index (BMI).

Materials & methods

Study population

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Medical College of Wisconsin (WI, USA). All participants were part of a cohort previously recruited through the Midwestern divisions of a large national weight-loss organization (TOPS). The original TOPS study cohort represents 2207 individuals from 507 families reporting predominantly northern European ancestry (98% Caucasian) [10]. For the current study, we selected those families that were informative in our initial studies of quantitative traits related to obesity [10,11], insulin resistance [12-15] and dyslipidemia [13-16]. This yielded a final study cohort of 1560 individuals in 261 extended families.

The TOPS study database contains information from families with at least two obese siblings (BMI >30 kg/m2), plus one or more never obese siblings (BMI <27 kg/m2), and availability of at least one (preferably both) parent(s). All participants provided informed consent, and phenotypic measurements were obtained at time of enrollment, including weight, height, BMI, waist circumference, hip circumference, as well as fasting glucose, insulin and lipids (total cholesterol, low-density-lipoprotein cholesterol [LDL-C], high-density-lipoprotein cholesterol [HDL-C] and triglycerides). The insulin:glucose ratio and homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance, homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) [17], were calculated to provide estimates of insulin sensitivity. As noted, 261 families (1560 subjects) were selected for CNR1 genotyping based upon prior contribution to loci associated with obesity (Table 1).

Table 1. Subject characteristics.

| Variable | N | Mean | Median | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 1531 | 46 | 44 | 13.00 | 90.00 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 1530 | 31.94 | 30.66 | 17.10 | 75.31 |

| Waist (cm) | 1594 | 102 | 100 | 44 | 855 |

| Hip (cm) | 1593 | 116 | 113 | 43 | 985 |

| Waist:hip | 1593 | 0.87 | 0.87 | 0.53 | 1.45 |

| Glucose (mg/dl) | 1475 | 89 | 83 | 36 | 379 |

| Insulin (pmol/l) | 1497 | 16.6 | 13.2 | 2.0 | 172.4 |

| HOMA-IR | 1475 | 3.78 | 2.78 | 0.38 | 58.70 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dl) | 1511 | 198 | 194 | 66 | 458 |

| LDL (mg/dl) | 1316 | 122 | 112 | 13 | 360 |

| HDL (mg/dl) | 1512 | 39 | 37 | 11 | 116 |

| TG (mg/dl) | 1511 | 127 | 105 | 27 | 2564 |

BMI: Body mass index; HDL: High-density lipoprotein; HOMA-IR: Homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance; LDL: Low-density lipoprotein; TG: Triglycerides.

tagSNP selection

The chromosomal position of the CNR1 gene was obtained from the University of California, Santa Cruz (UCSC) human genome browser [101]. We interrogated the entire gene plus 5 kb upstream and 5 kb downstream using NCBI build 35. SNPs within the identified region were downloaded from the International Human Haplotype Map for the Centre d’Etude du Polymorphisme Humain (CEPH) population, and entered into Haploview for an analysis of linkage disequilibrium (LD) and tagSNP assignment. The extent of LD across this region was quantified [18], and tagSNPs were identified using Tagger [19]. Applying the confidence interval method implemented in Haploview version 3.2 [20], we observed two haplotype blocks covering the entire CNR1 region of interest. This block structure - based upon the strength of each pairwise correlation (D’) - reflects boundaries represented by genomic coordinates 88,902,418–488,936,943 (NCBI build 35).

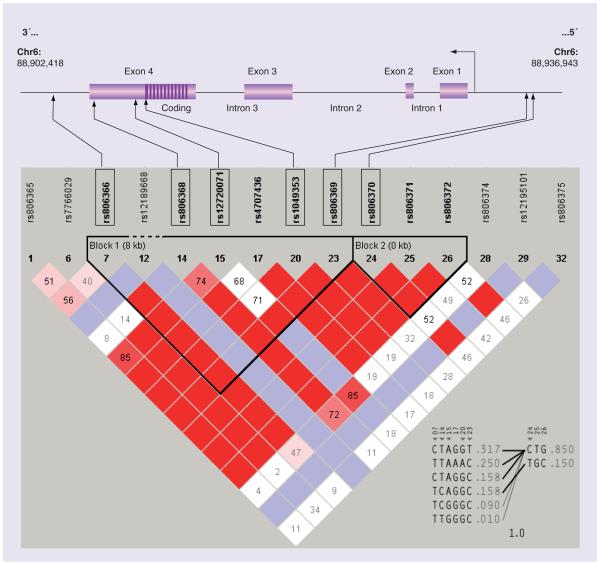

Using this approach, we observed that six tagSNPs were necessary to cover the linkage contained within the CNR1 region (Figure 1). These tagSNPs included two promoter SNPs (in separate LD blocks), three coding SNPs in the largest exon (exon 4), and a single SNP within the 3′-flanking region. The RefSeq accession numbers are listed in order from 5′ to 3′, in Table 2, along with the primers (designed within Primer3) used to amplify the regions encompassing each of the six respective tagSNPs used in this study.

Figure 1. Structure and physical location of the CNR1 gene on chromosome 6, along with the position of 15 CNR1 SNPs identified in the CEPH population of the Human HapMap.

The chromosomal position of the CNR1 gene was obtained from the UCSC human genome browser [101], for the entire gene plus 5 kb upstream and 5 kb downstream using NCBI build 35. SNPs within the identified region were downloaded from the International Human Haplotype Map [102], for the CEPH population, and entered into Haploview [103] for an analysis of LD and tagSNP assignment. Applying the confidence interval method implemented in Haploview version 3.2, we observed two haplotype blocks covering the entire region of interest. This block structure - based upon D’ - reflects boundaries represented by genomic coordinates 88,902,418–488,936,943 (NCBI Build 35). Pairwise comparison reveals the LD structure of these 15 SNPs (red: D’ 0.8). A total of six haplotypes were observed within the CEPH population at a frequency of more than 1% (five of these occurring at frequency >5%), and six haplotype-tagging SNPs (outlined by boxes) can be used to represent the variation in these haplotypes: two promoter SNPs, three coding SNPs (exon 4) and a single SNP within the 3′-flanking region.

CEPH: Centre d’Etude du Polymorphisme Humain; CNR1: Cannabinoid receptor 1; LD: Linkage disequilibrium; NCBI: National Center for Biotechnology Information; UCSC: University of California, Santa Cruz.

Table 2. Six haplotype tagging SNPs genotyped in TOPS for the CNR1 gene.

| No | tagSNP | Major/minor allele* | Location | Primers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | rs806370 | C/T (0.150) | Promoter | F: AGCTTTTTCACAGCAGGGATATG R: AAAGAAATGAATAGCCCACATTTT |

| 2 | rs806369 | C/T (0.317) | Promoter | F: AGCTTTTTCACAGCAGGGATATG R: CATGGAAATCCTTGGACACTCTC |

| 3 | rs1049353 | G/A (0.258) | Exon 4 | F: CTGCACAAACACGCAAACAAT R: CCTTTTCATTGAGCATGGTAAAGTT |

| 4 | rs12720071 | G/A (0.112) | Exon 4 | F: TGATTTAGATCTTGAAAGCACAACA R: GGCAGTACCAATGCTCTTTTCAC |

| 5 | rs806368 | C/T (0.190) | Exon 4 | F: GGTTTCCTTTCTTGGGAACTCTG R: ATGTTTGAGCAGTGGCCTACAA |

| 6 | rs806366 | T/C (0.475) | 3′-UTR | F: GGGTTGTGGCTTGTTTGAGTCTA R: CACTGTGTTGGAAAGAACACTGG |

Observed minor allele frequency within the TOPS population has been included in parenthesis (MAF).

F: Forward; MAF: Minor allele frequency; R: Reverse; TOPS: Take Off Pounds Sensibly.

Genotyping

The identified tagSNPs were genotyped using Invader™ technology (Third wave Technology, WI, USA). PCR primers (Table 2) were designed to amplify products containing each SNP locus, and custom Invader assays were then designed for all SNPs. Genotyping was performed in 384-well plates in a total volume of 6 μl, containing 0.5 μl PCR product, 0.02 μl of each primary probe, 0.002 μl Invader probe, 1.12 μl 2.6 M betaine (Sigma, MO, USA), 2.75 μl TrisEDTA (TE) buffer, 0.35 μl Cleavase (Third Wave Technologies) and 1.24 μl fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) mix (Third Wave Technologies). Reactions were denatured at 95°C for 5 mins and then incubated at 65°C for 15 mins. Plates were scanned twice on a plate reader (LJL Biosystems Model Analyst™ AD 96/384, Molecular Devices, Corp., CA, USA), using separate scans for each allele.

Genotypes were assigned, plate-by-plate, using a previously published clustering algorithm [21-23] implemented in a sequence management pipeline (SMP) hosted by the Human and Molecular Genetics Center at the Medical College of Wisconsin. Each datapoint was assigned to one of four clusters, representing negative controls, homozygotes (AA or BB), and heterozygotes (AB). Each cluster was then described by an ellipse whose axes were the standard deviations in the x and y directions of the component points [23].

Statistical analyses

Haploview 3.2 was used to characterize the LD across the region of interest, and Hardy-Weinberg (H-W) equilibrium statistics were calculated for each marker. Data management was conducted using SAS version 9.1 of the SAS/STAT System for Windows. Family-based tests of association were performed using the program single-locus family-based association tests (FBAT) [24,25]. This program tests for association in the presence of linkage, through a comparison of the genotypes received by the children (from their parents) with the genotypes expected to be received under the hypothesis of no association. Either FBAT or multilocus haplotype-based association tests (HBAT) can be performed. For single-locus genotypes, a comparison of all possible genotypes (the general genotype model) is available. This model considers simultaneous transmission from both parents, and separately tests for reception of each genotype by the children compared with what would be expected in the absence of association. More restrictive models include the additive model (in which the statistic used is the number of alleles of interest received by each affected child) and the dominant model (in which the statistic used is the presence or absence of the allele of interest in each affected child). The expected value in all situations is conditional on all available genotype data within the nuclear family. The FBAT program also indicates any data that are not consistent with Mendelian laws of segregation. Any inconsistent genotypes are removed, allowing this program to serve as a final check on the quality of our dataset.

Results

Study population

Our study cohort was selected based upon prior contribution to genetic loci associated with obesity and obesity-related metabolic disorders [10-16]. This cohort, shown in Table 1, represented the typical age and gender distribution observed in the general membership of the TOPS population: mean age 46 years (Standard deviation [SD]: 15 years). Although each family was recruited through an obese proband, the 1560 participants summarized in Table 1 represent members of large extended families (4–15 participants per family). We therefore observe wide variability in the distribution of each trait shown.

Single SNP-based association

Table 2 illustrates location, major allele, minor allele and minor allele frequency (MAF), for each of the six CNR1 tagSNPs, shown as oriented within the gene from 5′ to 3′ (rs806370 > rs806369 > rs1049353 > rs12720071 > rs806368 > rs806366). Each SNP was in H-W equilibrium in our study population. As introduced under Materials & methods, and shown in Figure 1, data available from International HapMap project [26] indicate that this entire gene contains two discrete haplotype blocks within the European population.

Within our cohort, we conducted family-based association tests (single-locus FBAT) to characterize the relationship between each of these CNR1 tagSNPs and phenotypic traits related to obesity (Table 3 & 4), insulin responsiveness (Table 5), and lipid homeostasis (Table 6 & 7). In the unadjusted dataset (Tables 3 & 4), only marginal associations were identified between CNR1 tagSNPs and traits related to obesity and insulin responsiveness. After the data were adjusted for age and gender, however, a single tagSNP located within the 3′-untranslated region (rs806366) was found to be associated with BMI (Table 4; n = 0.025). Although rs806366 was marginally associated with fasting insulin level in the unadjusted analyses (Table 5; p = 0.088), it was not associated with any other parameter of insulin responsiveness, and this marginal association with insulin level did not persist after the data were adjusted for age, gender and BMI (data not shown).

Table 3. Single SNP association, parameters of obesity and abdominal obesity.

| SNP | BMI | Waist circumference |

Hip circumference | Waist:hip ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs806366 | ns | 0.078 | ns | ns |

| rs806368 | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| rs806369 | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| rs806370 | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| rs1049353 | ns | 0.059 | ns | ns |

| rs12720071 | ns | ns | ns | ns |

BMI: Body mass index; ns: Not significant.

Table 4. Associations with parameters of obesity, adjusted for age and gender.

| SNP | BMI (adjusted for age, gender) |

Waist circumference (adjusted) |

Hip circumference (adjusted) |

Waist:hip ratio (adjusted) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs806366 | 0.025 | 0.068 | ns | ns |

| rs806368 | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| rs806369 | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| rs806370 | 0.095 | ns | ns | ns |

| rs1049353 | 0.066 | 0.068 | 0.079 | ns |

| rs12720071 | ns | ns | ns | ns |

BMI: Body mass index; ns: Not significant.

Table 5. Single SNP association tests, parameters reflecting insulin responsiveness.

| SNP | Insulin | Insulin adjusted for age, gender and BMI |

Glucose | I:G ratio | HOMA-IR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs806366 | 0.088 | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| rs806368 | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| rs806369 | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| rs806370 | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| rs1049353 | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| rs12720071 | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

BMI: Body mass index; HOMA-IR: Homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance; I:G: Insulin:glucose; ns: Not significant.

Table 6. Family-based, single-locus association tests - lipids.

| SNP | Total cholesterol | LDL cholesterol | HDL cholesterol | Triglyceride |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs806366 | ns | ns | 0.0090 | 0.0221 |

| rs806368 | 0.0795 | 0.0394 | 0.0900 | 0.0079 |

| rs806369 | 0.0240 | ns | ns | 0.0239 |

| rs806370 | ns | 0.0426 | 0.0576 | ns |

| rs1049353 | ns | ns | 0.0748 | ns |

| rs12720071 | ns | ns | ns | 0.0937 |

LDL: Low-density lipoprotein; HDL: High-density lipoprotein; ns: Not significant.

Table 7. Lipid associations adjusted for age, gender and BMI.

| SNP | Total cholesterol | LDL cholesterol | HDL cholesterol | Triglyceride |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs806366 | ns | ns | 0.0001 | 0.0325 |

| rs806368 | 0.0605 | 0.0321 | 0.0601 | 0.0001 |

| rs806369 | 0.0425 | ns | ns | 0.0257 |

| rs806370 | ns | 0.0600 | 0.0376 | ns |

| rs1049353 | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| rs12720071 | ns | ns | ns | 0.0643 |

BMI: Body mass index; LDL: Low-density lipoprotein; HDL: High-density lipoprotein; ns: Not significant.

Conversely, multiple CNR1 tagSNPs, in both LD blocks, were strongly associated with lipid levels (Table 6). For our study population (whose ancestry is primarily European), the most proximal promoter SNP (rs806370) was associated with circulating levels of HDL-C. By contrast, a second promoter SNP located within a more distal linkage block (rs806369) was associated with triglyceride levels as well as total cholesterol. Two additional tagSNPs were also associated with triglyceride levels: a coding SNP in exon 4 (rs806368) and a downstream SNP located within the 3′-untranslated region (rs806366). The results shown in Table 7 reveal that this pattern of association remained essentially unchanged after the data were adjusted for age, gender and BMI. This observation indicates that genetic variability in CNR1 is associated with dyslipidemia, independent of obesity.

Haplotype-based association

SNPs that form haplotypes can sometimes provide greater power than single-marker analyses for genetic disease associations. Although the uncertainty of haplotype prediction can reduce statistical power in collections of unrelated individuals, pedigree structure available within family-based collections yields only a very small residual error when haplotypes are assigned in the context of extended families [27,28]. Therefore, haplotype analysis was performed on the TOPS cohort to increase heterozygosity/genetic information, and improve our understanding of the relationship between CNR1 and lipids.

All haplotypes observed within our TOPS study population at a frequency greater than 5% are shown in Table 8, using six CNR1 tagSNPs oriented from 5′ to 3′ (i.e., according to the orientation presented initially in Table 2). A total of five common haplotypes were identified. These same haplotypes represent the five most common CNR1 haplotypes reported for the European (CEPH) cohort within the Human HapMap. All five haplotypes were tested for association with the metabolic traits available in the TOPS database [10].

Table 8. CNR1 haplotypes present in the TOPS population at a frequency of greater 5%.

| Haplotype (tags 5′–3′) |

TOPS (frequency) | CEPH (frequency*) |

Families‡ (number) |

Significance (n-value#) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCAATT | 0.290 | 0.250 | 158 | 0.209 |

| CTGATC | 0.275 | 0.317 | 175 | 0.697 |

| CCGATC | 0.213 | 0.158 | 161 | 0.0036 |

| TCGACT | 0.132 | 0.158 | 110 | 0.0491 |

| CCGGCT | 0.061 | 0.090 | 54 | 0.869 |

Frequency of the specified haplotype calculated in TOPS and observed in HapMap (CEPH).

The number of families informational for the test of transmission of the specific haplotype.

Significance estimated by applying a global test of all haplotype across the six given loci.

CEPH: Centre d’Etude du Polymorphisme Humain; TOPS: Take Off Pounds Sensibly.

The results are displayed with uncorrected p-values. These phenotypic traits are highly interrelated, and, therefore, not amenable to routine analytical strategies often used for the correction of multiple testing (i.e., such corrections assume ‘independence’ of each trait).

Although every possible combination of CNR1 tagSNPs can represent a haplotype that is preferentially transmitted to traits of interest under an additive model, the global tests implemented in the current study clearly indicate that the third haplotype (CCGATC) and the fourth haplotype (TCGACT) each carry an increased risk for the development of obesity and obesity-related metabolic disorders (Table 9). While haplotype 3 (H3) was associated with BMI and with the insulin:glucose (I:G) ratio, H3 was not associated with any lipid traits. Conversely, haplotype 4 (H4) was associated with all four lipid traits. These included total cholesterol (n = 0.005), LDL-C (n = 0.003), HDL-C (n = 0.03) and triglyceride (TG) (n = 0.004). H4 was also associated with I:G ratio (n = 0.04), and with four measures of obesity: BMI (n = 0.002), waist (n = 0.005), hips (n = 0.004) and waist:hip ratio (WHR); (n = 0.006). The association between H4 and HOMA-IR was marginal (n = 0.10, not shown).

Table 9. Association of CNR1 haplotypes with obesity-related phenotypes.

| Haplotype (tags 5′–3′) |

BMI (n-value) |

I:G ratio (n-value) |

T cholesterol (n-value) |

LDL-C (n-value) |

HDL-C (n-value) |

TGs (n-value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCAATT | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| CTGATC | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| CCGATC | 0.04 | 0.03 | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| TCGACT | 0.002 | 0.04 | 0.005 | 0.003 | 0.03 | 0.004 |

| CCGGCT | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

Two-sided unadjusted p-values: global tests allow us to partially offset the multiple testing problem.

BMI: Body mass index; HDL-C: HIgh-density-lipoprotein cholesterol; I:G Insulin:glucose; LDL-C: Low-density lipoprotein; ns: Not significant; TG: Triglyceride.

Lastly, to assess the directionality of these associations, we compared the mean and the distribution for three select obesity-related phenotypic traits (i.e., BMI, triglycerides and HDL-C) between individuals with 0, 1 or 2 copies of the H4 haplotype. As shown in Table 10, the subset of individuals expressing a H4 haplotype demonstrated higher mean BMI, higher mean triglyceride levels and lower mean HDL levels. An H4 haplotype may place subjects at an increased risk for developing the metabolic syndrome.

Table 10. Relationship between phenotype and number of H4 haplocopies.

| TCGACT | Descriptor | BMI* | HDL* | TGs* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 copies (n = 1505) | Max | 75.00 | 116.00 | 710.00 |

| Min | 17.10 | 11.00 | 27.00 | |

| Mean | 32.05 | 38.83 | 125.63 | |

| SD | 8.00 | 11.31 | 76.10 | |

| 1 copy (n = 313) | Max | 63.10 | 90.00 | 748.00 |

| Min | 17.90 | 18.00 | 30.00 | |

| Mean | 32.09 | 38.13 | 132.31 | |

| SD | 7.53 | 10.58 | 79.62 | |

| 2 copies (n = 18) | Max | 49.10 | 56.00 | 326.00 |

| Min | 22.70 | 23.00 | 54.00 | |

| Mean | 32.60 | 37.67 | 161.33 | |

| SD | 7.33 | 9.68 | 87.26 | |

p < 0.0001 by ANOVA.

ANOVA: Analysis of variance; BMI: Body mass index; HDL: high-density lipoprotein; SD: Standard deviation; TG: Triglyceride.

Discussion

Recent data suggest that CNR1 gene polymorphisms may be associated with obesity in subjects of European ancestry [6,7]. While several large population-based cohorts have provided evidence in support of this claim [7], this observation has failed to replicate in at least one cohort of similar composition [29]. We now present evidence for association between CNR1 gene variability and obesity in a family-based cohort, using one of the most rigorously characterized collections of obese study subjects in the USA, and we extend these findings to report a CNR1 haplotype that increases risk for dyslipidemia.

Using haplotype tagging SNPs selected from the European (CEPH) subset of the International Human Haplotype Map, we observed that a common haplotype (H4; prevalence 0.132) was associated with higher BMI, insulin resistance and dyslipidemia. The distribution of this haplotype within our study population was similar to the distribution of this haplotype within the European HapMap subpopulation. This observation is consistent with our prior comparison of LD in these two populations [23].

The most unique tagSNP within haplotype 4 is rs806370 (defined by a T allele that is shared with no other common CNR1 haplotype). This promoter SNP is also unique in that it tags a separate block of LD on the 5′ end of the gene. Within Haploview 3.2, application of the algorithm of Gabriel et al. recognized two blocks of LD within the CNR1 gene; rs806370 tags the smaller more proximal block of LD [18]. As shown in Tables 6 & 7, this promoter SNP is directly associated with HDL-C level. The physiologic mechanism underlying this association between CNR1 and HDL remains undetermined.

Within our study population, we also noted that a second promoter SNP (rs806369) was associated with triglyceride levels and total cholesterol, but not HDL. This promoter SNP is located closer to the transcription start site than rs806370, and within a larger block of LD that encompasses the remainder of the gene. Thus, genetic variability in CNR1 promoter function is likely to alter lipids through a complex, epistatic interaction [30]. In addition to the distal promoter SNP (rs806369), two more CNR1 tagSNPs were also associated with fasting triglyceride levels: a coding SNP in exon 4 (rs806368) and a downstream SNP located within the 3′-UTR (rs806366).

Recently, a considerable amount of investigation has been directed toward characterizing the relationship between exon 4 and obesity [6,7]. In a case-control analysis of CNR1 haplotype tagging SNPs in French-Caucasians, two tags (a SNP in exon 4, and a SNP in the intron proximal to exon 4) were found to be associated with obesity as a categorical variable [7]. This finding was replicated, using BMI as a continuous trait, in obese Swiss subjects, and within a sample of subjects from the general Danish population [7]. Prior work with haplotypes generated from CNR1 tagSNPs in exon 4 has revealed an association with substance abuse [31]. These haplotypes were constructed using tagSNPs typed in our study as well (rs1049353, rs12720071 and rs806368). Since two of these SNPs have recently been associated with impulsive behavior (rs1049353 and rs806368) [32], it is conceivable that the previously observed relationship(s) between variability in exon 4 and obesity may be partly mediated through a central effect on eating behavior.

In our family-based cohort of northern European ancestry, we saw no direct association between tagSNPs in exon 4 and obesity. However, we did observe a marginal association between exon 4 and waist circumference (tagSNP rs1049353; n = 0.059, single-locus FBAT). We also observed that another tagSNP, located just distal to exon 4, was strongly associated with BMI after the data were adjusted for age and gender (tagSNP rs806366; n = 0.025, single-locus FBAT). Clearly, genetic variability in (or around) exon 4 influences metabolic phenotype. However, the causative allele underlying this genetic association remains undetermined. One way to resolve this uncertainty would be the genomic resequencing of CNR1 in high-risk individuals from multiple populations. Analyses conducted with haplotypes could facilitate the identification of such individuals.

In the current study, we demonstrated that BMI is strongly associated with a common CNR1 haplotype (H4). This same CNR1 haplotype (H4) is also associated with insulin resistance and several clinical lipid derangements known to accompany the metabolic syndrome (i.e., high triglycerides and low HDL). Perhaps our most novel finding is the observation that the association between lipid disorders and genetic variability in CNR1 appears to be partly independent of BMI. Single SNP data presented in Table 7 reveal that the general pattern of association between lipids and CNR1 tagSNPs remains essentially unchanged after the data are adjusted for BMI. Although purely speculative, this latter interaction may be related to variability in CNR1 function within peripheral tissues (i.e., liver and adipose). Future mechanistic studies designed to test hypotheses such as these may inform the biology underlying the dyslipidemia of abdominal obesity.

Future perspective

Genetic variability in endocannabinergic signaling is known to influence the development of obesity. This can lead to secondary metabolic disorders associated with increased risk for cardiovascular disease. Our observation that genetic variability in CNR1 can influence lipid traits directly (i.e., independent of BMI) suggests that endocannabinergic signaling may play a physiological role in the maintenance of lipid homeostasis. Experiments designed to test this hypothesis may lead to novel treatment strategies for lipid disorders.

Executive summary

-

■

Cannabinoid receptor 1 (CNR1) antagonists have modest efficacy in the clinical treatment of obesity.

-

■

CNR1 antagonists have also been shown to improve lipid homeostasis, independent of their effect on obesity.

Results

-

■

Genetic variability in CNR1 is associated with body mass index.

-

■

Genetic variability in CNR1 is associated with insulin resistance and lipid disorders

-

■

Association between CNR1 and lipid disorders is partly independent of BMI.

Discussion

-

■

Endocannabinergic signaling may play a physiological role in the maintenance of lipid homeostasis.

-

■

Future experiments designed to advance our mechanistic understanding of this relationship may lead to novel treatment strategies for lipid disorders.

Footnotes

Financial & competing interests disclosure

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

Ethical conduct of research

The authors state that they have obtained appropriate institutional review board approval or have followed the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki for all human or animal experimental investigations. In addition, for investigations involving human subjects, informed consent has been obtained from the participants involved.

Bibliography

Papers of special note have been highlighted as:

■ of interest

■■ of considerable interest

- 1.Cota D, Tschöp MH, Horvath TL, Levine AS. Cannabinoids, opioids and eating behavior: The molecular face of hedonism? Brain Res. Rev. 2006;51(1):85–107. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2005.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jamshidi N, Taylor DA. Anandamide administration into the ventromedial hypothalamus stimulates appetite in rats. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2001;134(6):1151–1154. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eggan SM, Lewis DA. Immunocytochemical distribution of the cannabinoid CB1 receptor in the primate neocortex: a regional and laminar analysis. Cereb. Cortex. 2006;17(1):175–191. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhj136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lupica CR, Riegel AC. Endocannabinoid release from midbrain dopamine neurons: a potential substrate for cannabinoid receptor antagonist treatment of addiction. Neuropharmacology. 2005;48(8):1105–1116. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2005.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jbilo O, Ravinet-Trillou C, Arnone M, et al. The CB1 receptor antagonist rimonabant reverses the diet-induced obesity phenotype through the regulation of lipolysis and energy balance. FASEB J. 2005;19(11):1567–1569. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-3177fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ■.Provides evidence in favor of a peripheral role for CNR1 in lipid homeostasis.

- 6.Russo P, Strazzullo P, Cappuccio FP, et al. Genetic variations at the endocannabinoid type 1 receptor gene (CNR1) are associated with obesity phenotypes in men. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2007;92(6):2382–2386. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-2523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benzinou M, Chèvre JC, Ward KJ, et al. Endocannabinoid receptor 1 gene variations increase risk for obesity and modulate body mass index in European populations. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2008;17(13):1916–1921. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pi-Sunyer FX, Aronne LJ, Heshmati HM, et al. Effect of rimonabant, a cannabinoid-1 receptor blocker, on weight and cardiometabolic risk factors in overweight or obese patients: RIO-North America: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;295(7):761–775. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.7.761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van Gaal LF, Rissanen AM, Scheen AJ, Ziegler O, Rössner S, RIO-Europe Study Group Effects of the cannabinoid-1 receptor blocker rimonabant on weight reduction and cardiovascular risk factors in overweight patients: one year experience from the RIO-Europe study. Lancet. 2005;365(9468):1389–1397. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66374-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ■.Provides early evidence that an acquired (drug-induced) alteration in CNR1 activity can influence lipid homeostasis.

- 10.Kissebah AH, Sonnenberg GE, et al. Quantitative trait loci on chromosomes 3 and 17 influence phenotypes of the metabolic syndrome. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97(26):14478–14483. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.26.14478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ■.Describes the family-based cohort used in the current study, with an emphasis on the role of this cohort in the identification of quantitative trait loci for obesity.

- 11.Comuzzie AG, Funahashi T, Sonnenberg G, et al. The genetic basis of plasma variation in adiponectin, a global endophenotype for obesity and the metabolic syndrome. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2001;86(9):4321–4325. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.9.7878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martin LJ, Comuzzie AG, Sonnenberg GE, et al. Major quantitative trait locus for resting heart rate maps to a region on chromosome 4. Hypertension. 2004;43(5):1146–1151. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000122873.42047.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sonnenberg GE, Krakower GR, Martin LJ, et al. Genetic determinants of obesity-related lipid traits. J. Lipid Res. 2004;45(4):610–615. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M300474-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Curran JE, Jowett JB, Elliott KS, et al. Genetic variation in selenoprotein S influences inflammatory response. Nat. Genet. 2005;37(11):1234–1241. doi: 10.1038/ng1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walder K, Kerr-Bayles L, Civitarese A, et al. The mitochondrial rhomboid protease PSARL is a new candidate gene for Type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2005;48(3):459–468. doi: 10.1007/s00125-005-1675-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith EM, Wang X, Littrell J, et al. Comparison of linkage disequilibrium patterns between the HapMap CEPH samples and a family-based cohort of Northern European descent. Genomics. 2006;88(4):407–414. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ■.Provides evidence that our study cohort has similar linkage disequilibrium (LD) to the Centre d’Etude du Polymorphisme Humain (CEPH) population.

- 17.Matthews DR, Hosker JP, Rudenski AS, et al. Homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) and β-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia. 1985;28(7):412–419. doi: 10.1007/BF00280883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gabriel SB, Schaffner SF, Nguyen H, et al. The structure of haplotype blocks in the human genome. Science. 2002;296(5576):2225–2229. doi: 10.1126/science.1069424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Bakker PIW, Yelensky R, Pe’er I, Gabriel SB, Daly MJ, Altshuler D. Efficiency and power in genetic association studies. Nat. Genet. 2005;37:1217–1223. doi: 10.1038/ng1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barrett JC, Fry B, Maller J, Daly MJ. Haploview: analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(2):263–265. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Olivier M, Chuang LM, Chang MS, et al. High-throughput genotyping of single nucleotide polymorphisms using new biplex invader technology. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30(12):E53. doi: 10.1093/nar/gnf052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Olivier M. The Invader assay for SNP genotyping. Mutat. Res. 2005;573(1–2):103–110. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2004.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ■.Describes our adaptation of the high-throughput genotyping assay platform used in the current study.

- 23.Smith EM, Littrell J, Olivier M. Automated SNP genotype clustering algorithm to improve data completeness in high-throughput SNP genotyping datasets from custom arrays. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics. 2007;5(3–4):256–259. doi: 10.1016/S1672-0229(08)60014-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Laird NM, Horvath S, Xu X. Implementing a unified approach to family-based tests of association. Genet. Epidemiol. 2000;19(Suppl 1):S36–S42. doi: 10.1002/1098-2272(2000)19:1+<::AID-GEPI6>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Horvath S, Xu X, Lake SL, Silverman EK, Weiss ST, Laird NM. Family-based tests for associating haplotypes with general phenotype data: application to asthma genetics. Genet. Epidemiol. 2004;26(1):61–69. doi: 10.1002/gepi.10295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.International HapMap Consortium A second generation human haplotype map of over 3.1 million SNPs. Nature. 2007;449(7164):851–861. doi: 10.1038/nature06258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wiener HW, Perry RT, Chen Z, Harrell LE, Go RC. A polymorphism in SOD2 is associated with development of Alzheimer’s disease. Genes Brain Behav. 2007;6:770–775. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2007.00308.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Akey J, Jin L, Xiong M. Haplotypes vs single marker linkage disequilibrium tests: what do we gain? Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2001;9(4):291–300. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aberle J, Fedderwitz I, Klages N, George E, Beil FU. Genetic variation in two proteins of the endocannabinoid system and their influence on body mass index and metabolism under low fat diet. Horm. Metab. Res. 2007;39(5):395–397. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-977694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilke RA, Reif DM, Moore JH. Combinatorial pharmacogenetics. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2005;4(11):911–918. doi: 10.1038/nrd1874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang PW, Ishiguro H, Ohtsuki T, et al. Human cannabinoid receptor 1: 5′ exons, candidate regulatory regions, polymorphisms, haplotypes and association with polysubstance abuse. Mol. Psychiatry. 2004;9(10):916–931. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ehlers CL, Slutske WS, Lind PA, Wilhelmsen KC. Association between single nucleotide polymorphisms in the cannabinoid receptor gene (CNR1) and impulsivity in southwest California Indians. Twin Res. Hum. Genet. 2007;10(6):805–811. doi: 10.1375/twin.10.6.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Websites

- 101.UCSC human genome browser http://genome.cse.ucsc.edu/cgi-bin/hgGateway.

- 102.International Human Haplotype Map www.hapmap.org.

- 103.Haploview www.broad.mit.edu/mpg/haploview/

- 104.Sequence management pipeline (SMP) http://nitschke.brc.mcw.edu/~smp/snp/snp_index.shtml.