Abstract

Proteins composed of α-amino acids are essential components of the machinery required for life. Stanley Miller's renowned electric discharge experiment provided evidence that an environment of methane, ammonia, water, and hydrogen was sufficient to produce α-amino acids. This reaction also generated other potential protein building blocks such as the β-amino acid β-glycine (also known as β-alanine); however, the potential of these species to form complex ordered structures that support functional roles has not been widely investigated. In this report we apply a variety of biophysical techniques, including circular dichroism, differential scanning calorimetry, analytical ultracentrifugation, NMR and X-ray crystallography, to characterize the oligomerization of two 12-mer β3-peptides, Acid-1Y and Acid-1Y*. Like the previously reported β3-peptide Zwit-1F, Acid-1Y and Acid-1Y* fold spontaneously into discrete, octameric quaternary structures that we refer to as β-peptide bundles. Surprisingly, the Acid-1Y octamer is more stable than the analogous Zwit-1F octamer, in terms of both its thermodynamics and kinetics of unfolding. The structure of Acid-1Y, reported here to 2.3 Å resolution, provides intriguing hypotheses for the increase in stability. To summarize, in this work we provide additional evidence that nonnatural β-peptide oligomers can assemble into cooperatively folded structures with potential application in enzyme design, and as medical tools and nanomaterials. Furthermore, these studies suggest that nature's selection of α-amino acid precursors was not based solely on their ability to assemble into stable oligomeric structures.

Introduction

In 1929 Svedberg first recognized that discrete polypeptide chains could assemble into multisubunit quaternary structures.1 The formation of multisubunit proteins composed of highly ordered homo- or heteroligomers enables both control and specificity at the molecular level and has guided the evolution of sophisticated cellular processes essential for the development of life from simple precursors.2 Moreover, the discovery that control can be afforded via regulation of stable quaternary structures has accelerated the development of nanoscale devices with broad application in science and technology.3–5 Seminal work on natural and designed coiled coil proteins has revealed critical insights into the fundamental parameters that govern α-peptide assembly and conformation.6–8 A next goal is to elucidate the molecular rules governing the aqueous assembly of non-proteinaceous quaternary structure, a critical step in developing new and unique materials with potential as nanomaterials, drugs, and enzymatic platforms.9

β-Peptides, in particular oligomers of β3-amino acids, are a class of non-proteinaceous material with considerable potential for the development of unique quaternary structures.9–12 When properly designed, β3-peptides assemble into stable, monomeric, 314-helical structures in water, a first step toward formation of stable quaternary structures. Structural features that promote stable 314-helices include alternating cationic and anionic side chains arranged on one helical face to support salt bridge formation13–15 and arranged to minimize the helix macrodipole.12,16,17 Indeed, β3-peptides that embody these features tolerate extensive substitution of the remaining two helix faces12,17,18 to generate highly protease-resistant19 molecules that inhibit interactions between proteins both in vitro18,20,21 and in cell-based assays.22 Importantly, the inherent conformational flexibility of β3-peptides, when compared to cyclic analogues such as ACHC,23 may be essential to the general success of this approach, as all β3-peptides of known structure that effectively inhibit protein interactions possess geometries that deviate from the ideal 314-helix imposed by ACHC.21,22,24 Larger mixed-sequence peptides containing both α- and β-amino acids have also shown success as protein ligands for the BH3 recognition site of Bcl-xL.25,26

Several strategies have been pursued to identify β-peptides that assemble into discrete, well-folded quaternary structures whose thermodynamic properties resemble those of natural proteins. Remarkably, as early as 1998, Clark et al. showed that cyclic β3-peptides designed to self-assemble in lipid bilayers supported K+ conductance, although the existence of higher-order structure was not investigated.27 In 2001, Raguse et al. described a short β-peptide that self-associated in water to form a buffer-dependent mixture of quaternary states at high concentration as judged by analytical ultracentrifugation.28 The first example of a protein-like higher-order structure was reported in 2003 by Cheng and DeGrado, who described a β-peptide 15-mer containing an amino terminal (S)-cysteine residue.29 Disulfide bond formation between two β-peptide monomers generated a covalent β-peptide dimer that underwent a cooperative melting transition.29,30

Recently, we discovered that β-peptides containing alternating cationic and anionic side chains arranged on one helical face13,14 and β-homoleucine residues on a second face assemble into helical oligomers that we refer to as β-peptide bundles.31-33 The β-peptide bundles formed from the sequences Zwit-1F, its iodinated analogue Zwit-1F*, and the 1:1 mixture of Acid-1F and Base-1F (Figure 1) were characterized extensively using biophysicalmethodsandhigh-resolutionstructuredetermination.31–34 Here, we characterize the related homo-oligomers Acid-1Y and its iodinated analogue Acid-1Y* using analytical ultracentrifugation (AU), circular dichroism (CD), differential scanning calorimetry (DSC), 1-anilino-8-naphthalenesulfonate (ANS) binding, NMR spectroscopy, and X-ray crystallography. Acid-1Y and Acid-1Y* assemble into stable, well-folded, octameric bundles whose three-dimensional structures are remarkably similar to those of Zwit-1F32 and the mixture of Acid-1F and Base-1F (D. Daniels, J. Qiu, and A. Schepartz, manuscript in preparation), indicating the robust nature of the octamer fold. Surprisingly, the Acid-1Y octamer is more stable, in terms of both its thermodynamics and kinetics of unfolding, than the analogous structures formed from either Zwit-1F or the Acid-1F/Base-1F pair. The structure of Acid-1Y, reported here to 2.3 Å resolution, provides an intriguing hypothesis for the increase in stability. To summarize, in this work we provide additional evidence that nonnatural β-peptide oligomers can assemble into cooperatively folded structures (with potential application in enzyme design) and as medical tools and nanomaterials. Furthermore, these studies imply that nature's selection of α-amino acid precursors was not based solely on their ability to assemble into stable oligomeric structures, and rather might be attributed to the minimal availability of diverse β-amino acids monomers in the primitive environment.

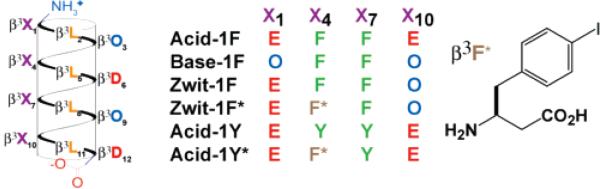

Figure 1.

Helical net representation of bundle-forming β3-peptides and the structure of the β3-4-iodohomophenylalanine residue found in Zwit-1F* and Acid-1Y*. Previously characterized β-peptide bundles include Zwit-1F and Zwit-1F*31–33 as well as a 1:1 mixture of Acid-1F and Base-1F (D. Daniels, J. Qiu, A. Schepartz, manuscript in preparation).

Results

Circular Dichroism (CD) Spectroscopy Detects Acid-1Y Self-Association in Solution

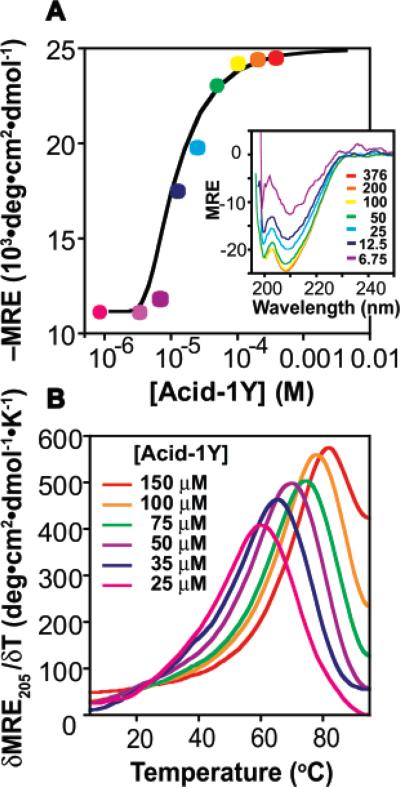

A series of experiments were performed to characterize whether Acid-1Y underwent self-association and, if so, how the oligomeric state and stability compared with that of Zwit-1F. Initially, we made use of CD spectroscopy to determine whether there was a concentration-dependent change in 314-helical structure (as judged by the molar residue ellipticity at 208 nm, MRE20813) in Acid-1Y. As was true for Zwit-1F and Zwit-1F*,33 CD analysis of Acid-1Y reveals an increase in 314-helix structure between concentrations of 6 and 376 μM (Figure 2A, inset). The concentration-dependent change in the 314-helical CD signature suggests that Acid-1Y equilibrates between a minimally structured monomeric state and a more highly structured oligomeric state. A plot of MRE208 as a function of Acid-1Y concentration fits well to a monomer–octamer equilibrium with ln Ka = 82.5 ± 1.8 (Figure 2A). In addition, the CD spectra of Acid-1Y as a function of temperature (Figure 2B) reveals a concentration-dependent increase in Tm, also clearly indicative of concentration-dependent self-association.35 The Tm (defined as the maximum in a plot of δMRE208·δT–1) of a 100 μM Acid-1Y solution is 78 °C, a value comparable to the previously observed value of 70 °C for Zwit-1F (100 μM).33 In summary, both wavelength- and temperature-dependent CD experiments indicate that Acid-1Y assembles into a 314-helical oligomer and shows CD characteristics that mimic those found in proteins composed solely of α-amino acids.36

Figure 2.

Acid-1Y self-association monitored by circular dichroism spectroscopy (CD). (A) Plot of MRE208 as a function of [Acid-1Y]T fit to a monomer–octamer equilibrium. (Inset) Wavelength-dependent CD spectra of Acid-1Y (MRE208 in units of 103 deg·cm2·dmol–1) at the indicated [Acid-1Y]T (μM). (B) Plot of δMRE205·δT–1 for the concentrations of Acid-1Y shown.

Analytical Ultracentrifugation: The Acid-1Y Oligomer Is an Octamer in Solution

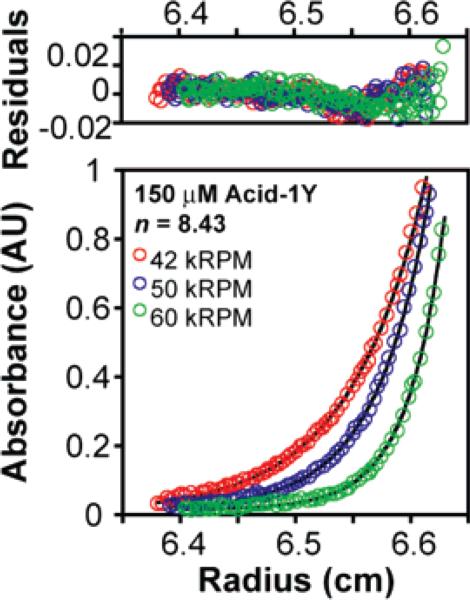

Next we turned to analytical ultra-centrifugation to elucidate the oligomeric state of Acid-1Y in solution. Sedimentation was monitored at three speeds (42 000, 50 000, and 60 000 RPM) at concentrations of 75, 150, and 300 μM. The AU data fit best to a monomer-n-mer equilibrium where n = 8.4 (n was allowed to vary) with an rmsd of 0.0093 (Figure 3). Significantly poorer fits (rmsd's of 0.0172 and 0.0132) were observed when n was set to equal 7 or 10, respectively, whereas comparable fits were found when n was set to equal 8 or 9 (rmsd's of 0.0100 and 0.0101, respectively, see Supporting Information). The ln Ka value calculated from the fits where n = 8.43 and n = 8 (84.3 ± 1.6 and 83.3 ± 1.8) agree well with the ln Ka value calculated from the CD data (82.5 ± 1.8), providing additional support for equilibration between monomeric and octameric Acid-1Y. The value of ln Ka describing the Acid-1Y monomer–octamer equilibrium calculated from either the AU or CD data (84.3 ± 1.6 and 82.5 ± 1.8, respectively) is significantly more favorable than the corresponding values calculated for Zwit-1F (ln Ka = 71.0 ± 0.9 and 70.5 ± 1.9, respectively).33 suggesting that the Acid-1Y octamer is thermodynamically more stable than the previously characterized Zwit-1F octamer.

Figure 3.

Acid-1Y self-association monitored by analytical ultracentrifugation (AU) (150 μM Acid-1Y) and fit to monomer-n-mer equilibria where n = 8.4. Samples were prepared in 10 mM NaH2PO4, 200 mM NaCl (pH 7.1) and centrifuged to equilibrium at 25 °C at speeds of 42 (red), 50 (green), or 60 (blue) kRPM. The experimental data points are shown as open circles; lines indicate a fit to a monomer–octamer model as described in the experimental section (see Supporting Information).

ANS Fluorescence Indicates Acid-1Y Contains a Close-Packed Hydrophobic Core

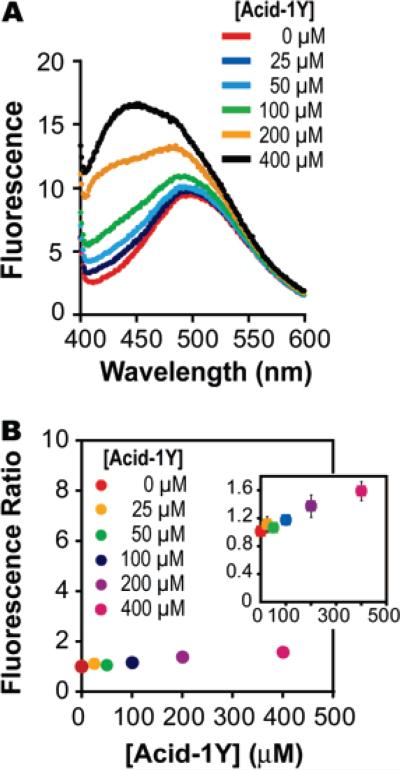

Next we used 1-anilino-8-naphthalenesulfonate (ANS) to probe the quaternary structure of the Acid-1Y octamer. An increase in the fluorescence of ANS occurs upon binding to hydrophobic surfaces and is an important diagnostic for probing the exposure of the hydrophobic core of a protein.37 A significant increase in ANS fluorescence in the presence of a protein indicates a loosely folded, more exposed hydrophobic core; for example, relative ANS fluorescence increases by a factor of 100 in the presence of the α-lactalbumin molten globule.38 By contrast, well-folded or unfolded proteins generally do not provide a favorable ANS binding site, and little or no fluorescence changes (fewer than 10 units in fluorescence intensity) are observed in these cases.38–40 The relative ANS fluorescence (as determined by the ratio of the maximal emission of the solution in the presence and absence of Acid-1Y) increased from a value of 1.1 at 25 μM Acid-1Y (26% monomer, 74% octamer) to a value of 1.6 at 400 μM Acid-1Y, where 98% of the sample is assembled into the octameric form (Figure 4). The minimal increase in ANS fluorescence as a function of Acid-1Y concentration implies that the Acid-1Y octamer is well-folded, with a minimally exposed hydrophobic interior. Similar results were obtained with the Acid-1Y analogue Acid-1F; in this latter case the ANS fluorescence is unchanged at concentrations as high as 400 μM. Zwit-1F precipitated from solution when mixed with ANS and thus could not be characterized in this way.

Figure 4.

Fluorescence of 1-anilino-8-naphthalenesulfonate (ANS) in the presence and absence of Acid-1Y. (A) Change in fluorescence of 10 μM ANS in the presence of the indicated concentration of Acid-1Y. Binding reactions were prepared in a buffer composed of 10 × PBC (100 mM phosphate, borate, and citrate) and 200 mM NaCl (pH 7.0). (B). Ratio of ANS fluorescence in the presence of given concentrations of Acid-1Y relative to fluorescence in the absence of peptide (10 μM ANS) as calculated using the global maximum fluorescence value for each concentration (observed at 492, 497, 491, 490, 487, 433 nm for concentrations of 0, 25, 50, 100, 200, and 400 μM Acid-1Y, respectively). (Inset) Fluorescence ratio of Acid-1Y as a function of concentration on a smaller scale to show the error bars.

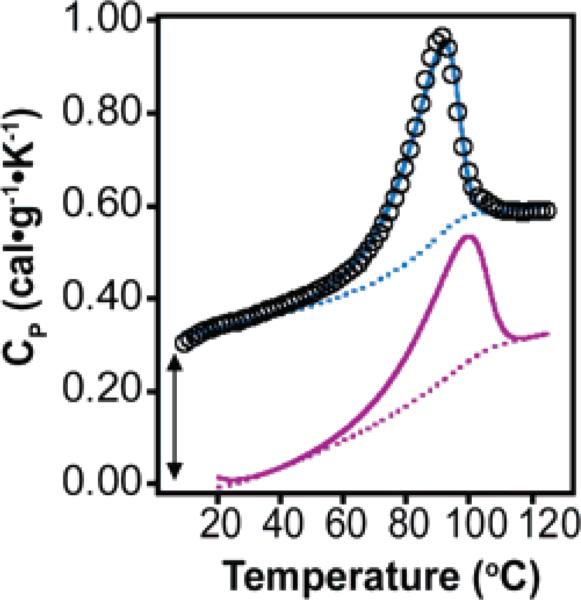

Direct Calorimetric Measurement of Acid-1Y Stability

To further explore the differences in stability between Zwit-1F and Acid-1Y, we determined the enthalpy of unfolding of Acid-1Y by differential scanning calorimetry.35,41 Experiments were performed in phosphate buffer (10 mM sodium phosphate, 200 mM sodium chloride, pH 7.2) to enable direct comparison with previously reported values for Zwit-1F.33 Examination of the thermograms in Figure 5 reveals that the width at half-maximum of the Acid-1Y unfolding transition is 18 °C versus 26 °C for the Zwit-1F transition. This difference could indicate that Acid-1Y unfolds more cooperatively than does Zwit-1F, but a formal assessment of cooperativity requires comparison of the ratios of van't Hoff enthalpy to calorimetric enthalpy (ΔHvH/ΔHCal) for each β-peptide. The thermal denaturation of both β-peptide bundles fits well to a two-state dissociative unfolding transition, but the enthalpy at the transition temperature ΔHCal(T1/2) is greater for Acid-1Y than for Zwit-1F. For a 300 μM Acid-1 Y sample, ΔHCal is 132.0 kcal·mol–1 octamer at the T1/2 of 83.1 °C, nearly 25 kcal greater than ΔHCal(T1/2) of an equivalent concentration of Zwit-1F (107.4 kcal·mol–1 octamer at 89.1 °C). Using the Gibbs–Helmholz equation, we determined the folding/association equilibrium constant of Acid-1Y to be 1.7 × 10–35 (ln Ka = 81.1) at 25 °C, in agreement with fits to the AU and CD data (see Supporting Information),. The ΔHvH/ΔHCal ratios of Zwit-1F and Acid-1Y are 1.64 and 1.57, respectively, indicating comparable levels of intermolecular cooperativity.35,42 Thus, the DSC data demonstrate that Acid-1Y is significantly more stable thermodynamically than Zwit-1F with a similar level of cooperativity in its folding transition.

Figure 5.

DSC analysis of 300 μM Acid-1Y fit to a subunit dissociation model as described in Supporting Information. Raw data are shown as black circles, the calculated thermogram is shown as a blue line, and the baseline as a dotted blue line. The calculated thermogram and baseline for 300 μM Zwit-1F are shown as purple solid and dotted lines, respectively. The Acid-1Y data set is offset artificially for clarity, as indicated by the arrow.

Side Chain Packing Drives Octamer Formation

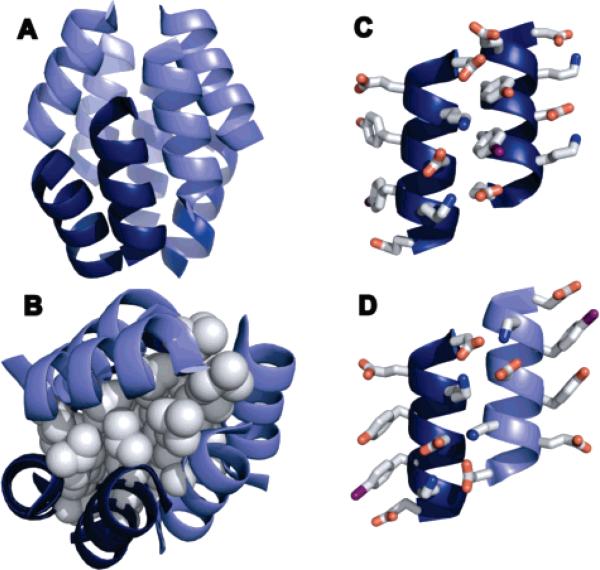

To further characterize the Acid-1Y octamer and identify potential explanations for its increased stability, we determined the structure of the Acid-1Y* oligomer by molecular replacement of a tetrameric asymmetric unit of Zwit-1F (Table SI-1). The refined model is octameric and remarkably similar to the octameric Zwit-1F and Zwit-1F* structures (Figure 6).32 The Acid-1Y* model consists of eight 314-helices organized into two tetramers related by a two-fold rotation axis (Figure 6A). The design for the β-peptide quaternary structure was based on the packing of leucine residues in coiled coils, a motif that promotes oligomerization of natural proteins.43,44 As predicted, our structure possesses a quaternary organization that facilitates leucine packing and sequestration from water, minimizing exposure of the leucine side chains to the polar solvent. The tetramers are positioned to allow the leucine residues to maximize hydrophobic packing and shielding from solvent, affording a 180° rotation of one of the tetramers in relation to the other.45

Figure 6.

Crystal structure of Acid-1Y*. (A) Ribbon diagram of Acid-1Y* octamer with parallel helices represented by similar shading. The rmsd is 20 Å between the previously solved Zwit-1F and the current Acid-1Y structures. (B) Space-filling model of leucine side-chain packing in the Acid-1Y* core. Ribbon diagram of (C) parallel and (D) antiparallel helices illustrating side-chain interactions.

Acid-1Y is a Stable Template for Design

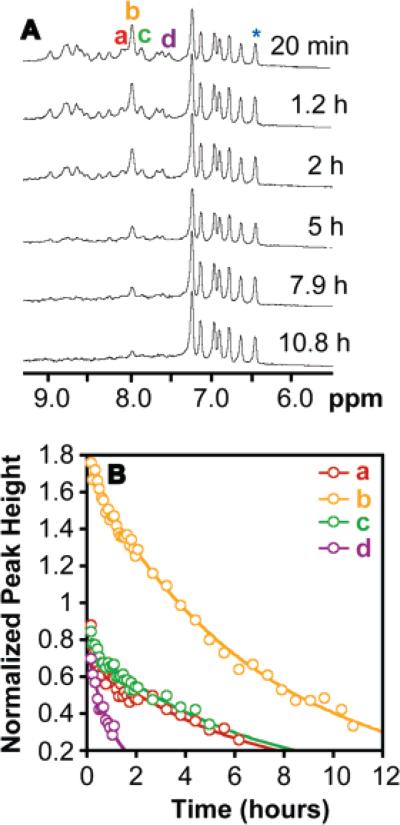

We used hydrogen/deuterium exchange NMR, a method used to characterize the stabilities of natural proteins, to characterize the kinetic stability of the Acid-1Y octamer.46 The Acid-1Y amide resonances span 1.5 ppm (Figure 7A), a range similar to that observed for the amide resonances of Zwit-1F (1.4 ppm).33 The amide resonances of both β-peptide bundles span a chemical shift range larger than the 0.5 ppm range observed for the monomeric Acid-1YL2A,L11A variant.33 The broad chemical shift range observed for the Acid-1Y amide resonances indicates that Acid-1Y forms a distinct quaternary structure, providing unique and differentiated electronic environments for the amide resonances.

Figure 7.

Hydrogen/deuterium NMR exchange analysis of the Acid-1Y octamer. (A) 500 MHz 1H NMR spectra of 0.750 mM Acid-1Y acquired at the indicated times after a lyophilized Acid-1Y sample was reconstituted in phosphate-buffered D2O. (B) The normalized heights of the indicated resonances (normalized to the aromatic resonance at 6.39 ppm (*)) fit to exponential function.

Amide N–H exchange rates (kex) correlate with the availability of amide protons to exchange with bulk solvent.47 Slow exchange rates are observed for amide protons that are protected from exchange due to participation in stabilizing hydrogen-bond interactions. The disappearance of peaks a–d (Figure 7A) of the Acid-1Y bundle can be fit to a first-order kinetic model with exchange rate constants that vary between 3.5 × 10–5 and 2.3 × 10–4 s–1 (Figure 7B). These exchange rate constants can be compared to that calculated for a random coil amide N-H model system (krc), in our case β-glycine oligomers.48 Using these values, the protection factor (P) for the amide resonances of the samples can be calculated (P = krc/kex), and the P value used to compare amide exchange rates among different protein and other β-peptide quaternary systems.33,48,49 The calculated protection factors for a 750 μM (98% folded) solution of Acid-1Y range between 2.1 × 104 and 6.5 × 104. In contrast, the protection factors for a 1.5 mM (97% folded) solution of Zwit-1F are between 3.4 × 103 and 2 × 104 and 6 × 103 for a 750 μM (94% folded) solution of Zwit-1F.33,50 The differences in the protection factors suggests that Acid-1Y amide protons are more protected than those of Zwit-1F. Furthermore, the stability inferred from these Acid-1Y protection factors is comparable to the stability of small-bundle proteins GCN4 (P = 104 at 1.0 mM) and ROP (P = 105 at 250 μM).6,33,46,51

We note that our interpretations of stability are based on protection factors calculated with reference to poly-β-homoglycine exchange rates, the only data available for β-amino acid oligomers. An alternative (and more conservative) method to calculate P values for Acid-1Y makes reference to krc values for α-amino acid dipeptides corresponding to the Acid-1Y sequence, specifically to that of Glu-Leu, whose exchange rate is the lowest.49 P values calculated using the krc for Glu-Leu agree within a factor of 4 (Table S1) with those calculated with reference to poly-β-homoglycine. A more accurate analysis of Acid-1Y and Zwit-1F stabilities, as evaluated from their respective protection factors, requires broad calibration of exchange rates for all β-amino acids to reduce the uncertainty in the protection factors calculated for our β-peptide bundles.

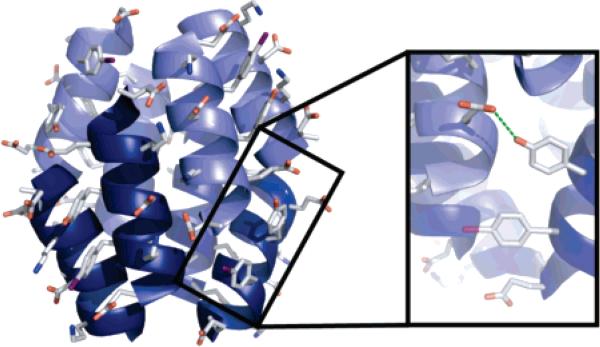

Our biophysical characterization of Acid-1Y identified a small, but significant increase in thermal stability of the Acid-1Y octamer as compared to the previously characterized Zwit-1F octamer. A possible explanation for the increased stability of Acid-1Y derives from hydrogen-bonding interactions of the Acid-1Y tyrosine hydroxyl group (Figure 8). The distance between the tyrosine hydroxyl (Y7) and the nearest hydrogen bond-accepting carbonyl (E10) is too far to support formation of a direct hydrogen bond (4.08 Å). However, solvent density in the crystal structure suggests that a water hydrogen-bond network may exist as supported by the hydrogen-bonding potential of the tyrosine residue in Acid-1Y, which is not provided by the phenylalanine residue in Zwit-1F. The presence of this water network could contribute added stability to the Acid-1Y structure as compared to the lack of phenylalanine solvation in Zwit-1F, and the unfavorable entropic penalty introduced by the exposure of the hydrophobic residue to the polar solvent.52

Figure 8.

Structure of Acid-1Y with tyrosine side chains rendered as sticks illustrates hydrogen-bond formation between a tyrosine residue of one helix with an aspartic acid residue from another helix, showing how the tyrosine hydroxyl could provide additional stability through hydrogen-bond formation.

Discussion

The question of how complex structures evolved under primitive Earth conditions has been extensively investigated.53 One widely cited experiment of this kind, Miller's classic electric discharge experiment,54 provided the first glimpse at how α-amino acids could be generated in a primordial environment composed of methane, hydrogen, ammonia, and water. The α-amino acids produced during the Miller discharge experiment provided a chemical rationale for the source of monomer building blocks used for ribosomal protein synthesis.

The plethora of products produced from Miller's experiment–which include β- and γ-amino acids in addition to β-amino acids–does not provide a sigular rationale for the selection of α-amino acids as protein building blocks. β-glycine (described as β-alanine) was produced from the electric discharge reaction in amounts comparable to levels of certain α-amino acids.54–56 The similarity in backbone structure of β-amino acids to that of α-amino acids would indicate that either product could support secondary and quaternary structure formation and unique functionalization. Additionally, although β-amino acids are not constituents of natural proteins, they are requisite intermediates during metabolism (metabolites of thymine and valine), constituents of natural products (for example, crytophycins), and can be isolated from meteorites in quantities comparable to α-amino acids.54,56,57

With such an array of functional amino acid products arising from Miller's reaction, it is interesting to ask why α-amino acids were selected in the presence of alternative compounds containing the same functional groups. Possible answers include the following: (1) that the other products did not have the ability to assemble into discrete higher-order structures and/or (2) assemblies of the other products lacked stability to support the complex functions required for the evolution of life. We have shown that β-peptide quaternary structures possess stabilities and structures that closely resemble those of natural α-amino acid proteins. These results suggest that nature did not preferentially select α-amino acids as the minimal protein unit because of the stability of quaternary structures formed from α-amino acid oligomers, but perhaps because of the incremental energetic cost of assembling the extended β-amino acid backbone. The distribution of amino acids produced in Miller's experiments support this reasoning, as the products include a greater variety of α-amino acid monomers (glycine, alanine, valine, proline, serine, aspartic acid, glutamic acid) than β-amino acid monomers (β-alanine).54–56,58 The diverse array of available α-amino acids may have provided an expanded capacity to develop unique and differentiated structures with specialized functions as compared to β-amino acids.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

This work is dedicated to Stanley Miller. This work was supported by the NIH (GM 65453 and 74756) and by the National Foundation for Cancer Research. We thank the faculty and staff at the Yale Center for Structural Biology for assistance and use of their data collection facilities. We also thank Cody J. Craig for assistance with the analytical ultracentrifugation studies and buffer optimization.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Experimental details. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org. CCDC 662300 contains the supplementary crystal-lographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.

References

- 1.Svedberg T, Fahraeus R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1926;48:430–438. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klotz IM, Langerman NR, Darnall DW. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1970;39:25–62. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.39.070170.000325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shimojima A, Liu Z, Ohsuna T, Terasaki O, Kuroda K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:14108–14116. doi: 10.1021/ja0541736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mirkin CA, Letsinger RL, Mucic RC, Storhoff JJ. Nature. 1996;382:607–609. doi: 10.1038/382607a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hartgerink JD, Clark TD, Ghadiri RM. Chem. Eur. J. 1998;4:1367–1372. [Google Scholar]

- 6.O'Shea EK, Lumb KJ, Kim PS. Curr. Biol. 1993;3:658–667. doi: 10.1016/0960-9822(93)90063-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harbury PB, Zhang T, Kim PS, Alber T. Science. 1993;262:1401–1407. doi: 10.1126/science.8248779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moffet DA, Hecht MH. Chem. Rev. 2001;101:3191–3203. doi: 10.1021/cr000051e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goodman CM, Choi S, Shandler S, DeGrado WF. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2007;3:252–262. doi: 10.1038/nchembio876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DeGrado WF, Schneider JP, Hamuro Y. J. Pept. Res. 1999;54:206–217. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3011.1999.00131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheng RP, Gellman SH, DeGrado WF. Chem. Rev. 2001;101:3219–3232. doi: 10.1021/cr000045i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kritzer JA, Tirado-Rives J, Hart SA, Lear JD, Jorgensen WL, Schepartz A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:167–178. doi: 10.1021/ja0459375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheng RP, DeGrado WF. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:5162–5163. doi: 10.1021/ja010438e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arvidsson PI, Rueping M, Seebach D. Chem. Commun. 2001;7:649–650. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stable 314-helices are also obtained upon replacement of β3-amino acids with cyclic ACHC residues: Gellman SH. Acc. Chem. Res. 1998;31:173–180.

- 16.Hart SA, Bahadoor AB, Matthews EE, Qiu XJ, Schepartz A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:4022–4023. doi: 10.1021/ja029868a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guarracino DA, Chiang HR, Banks TN, Lear JD, Hodsdon ME, Schepartz A. Org. Lett. 2006;8:807–810. doi: 10.1021/ol0527532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kritzer JA, Luedtke NW, Harker EA, Schepartz A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:14584–14585. doi: 10.1021/ja055050o. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schreiber JV, Frackenpohl J, Moser F, Fleischmann T, Kohler HP, Seebach D. ChemBioChem. 2002;3:424–432. doi: 10.1002/1439-7633(20020503)3:5<424::AID-CBIC424>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kritzer JA, Zutshi R, Cheah M, Ran FA, Webman R, Wongjirad TM, Schepartz A. ChemBioChem. 2006;7:29–31. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200500324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kritzer JA, Hodsdon ME, Schepartz A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:4118–4119. doi: 10.1021/ja042933r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stephens OM, Kim S, Welch BD, Hodsdon ME, Kay MS, Schepartz A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:13126–13127. doi: 10.1021/ja053444+. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Raguse TL, Porter EA, Weisblum B, Gellman SH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:12774–12785. doi: 10.1021/ja0270423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kritzer JA, Stephens OM, Guarracino DA, Reznik SK, Schepartz A. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2005;13:11–16. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2004.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sadowsky JD, Schmitt MA, Lee HS, Umezawa N, Wang S, Tomita Y, Gellman SH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:11966–8. doi: 10.1021/ja053678t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.English EP, Chumanov RS, Gellman SH, Compton T. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:2661–2667. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508485200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clark TD, Buehler LK, Ghadiri MR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:651–656. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Raguse TL, Lai JR, LePlae PR, Gellman SH. Org. Lett. 2001;3:3963–3966. doi: 10.1021/ol016868r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cheng RP, DeGrado WF. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:11564–5. doi: 10.1021/ja020728a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.In 2006, Lelais et al. reported a β-peptide that bound Zn2+ in a 1:1 stoichiometry: Lelais G, Seebach D, Jaun B, Mathad RI, Flogel O, Rossi F, Campo M, Wortmann A. Helv. Chim. Acta. 2006;89:361–403.

- 31.Qiu JX, Petersson EJ, Matthews EE, Schepartz A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:11338–11339. doi: 10.1021/ja063164+. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Daniels DS, Petersson EJ, Qiu JX, Schepartz A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:1532–1533. doi: 10.1021/ja068678n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Petersson EJ, Craig CJ, Daniels DS, Qiu JX, Schepartz A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:5344–5345. doi: 10.1021/ja070567g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Recently Horne et al. described the structure of a GCN4 variant containing several β-amino acids in place of their α-amino acid counterparts: Horne WS, Price JL, Keck JL, Gellman SH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:4178–4179. doi: 10.1021/ja070396f.

- 35.Sturtevant JM. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 1987;38:463–488. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Privalov PL, Tiktopulo EI, Venyaminov S, Griko Yu V, Makhatadze GI, Khechinashvili NN. J. Mol. Biol. 1989;205:737–750. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(89)90318-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Matulis D, Baumann CG, Bloomfield VA, Lovrien RE. Biopolymers. 1999;49:451–458. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0282(199905)49:6<451::AID-BIP3>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lumb KJ, Kim PS. Biochemistry. 1995;34:8642–8648. doi: 10.1021/bi00027a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Semisotnov GV, Rodionova NA, Razgulyaev OI, Uversky VN, Gripas AF, Gilmanshin RI. Biopolymers. 1991;31:119–128. doi: 10.1002/bip.360310111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bruckner AM, Chakraborty P, Gellman SH, Diederichsen U. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2003;42:4395–4399. doi: 10.1002/anie.200351871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Privalov PL, Potekhin SA. Methods Enzymol. 1986;131:4–51. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(86)31033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marky LA, Breslauer KJ. Biopolymers. 1987;26:1601–1620. doi: 10.1002/bip.360260911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Crick FHC. Acta Crystallogr. 1953;6:689–697. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Crick FHC. Acta Crystallogr. 1953;6:685–689. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chothia C, Janin J. Nature. 1975;256:705–708. doi: 10.1038/256705a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Krishna MM, Hoang L, Lin Y, Englander SW. Methods. 2004;34:51–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2004.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Krishna MMG, Hoang L, Lin Y, Englander SW. Methods. 2004;34:51–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2004.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Glickson JD, Applequist J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1971;93:3276–3281. doi: 10.1021/ja00742a030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bai YW, Milne JS, Mayne L, Englander SW. Proteins: Struct., Funct., Genet. 1993;17:75–86. doi: 10.1002/prot.340170110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Please see Supporting Information for details.

- 51.Munson M, Balasubramanian S, Fleming KG, Nagi AD, O'Brien R, Sturtevant JM, Regan L. Protein Sci. 1996;5:1584–1593. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560050813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rossky PJ, Karplus M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1979;101:1913–1937. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Brack A. Chem. Biodiversity. 2007;4:665–679. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.200790057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Miller SL. Science. 1953;117:528–529. doi: 10.1126/science.117.3046.528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Miller SL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1955;77:2351–2361. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wolman Y, Haverland WJ, Miller SL. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1972;69:809–811. doi: 10.1073/pnas.69.4.809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lelais G, Seebach D. Biopolymers. 2004;76:206–243. doi: 10.1002/bip.20088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Miyakawa S, Yamanashi H, Kobayashi K, Cleaves HJ, Miller SL. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2002;99:14628–14631. doi: 10.1073/pnas.192568299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.