Abstract

Infectious mononucleosis due to Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection sometimes causes acute hepatitis, which is usually self-limiting with mildly elevated transaminases, but rarely with jaundice. Primary EBV infection in children is usually asymptomatic, but in a small number of healthy individuals, typically young adults, EBV infection results in a clinical syndrome of infectious mononucleosis with hepatitis, with typical symptoms of fever, pharyngitis, lymphadenopathy, and hepatosplenomegaly. EBV is rather uncommonly confirmed as an etiologic agent of acute hepatitis in adults. Here, we report two cases: the first case with acute hepatitis secondary to infectious mononucleosis and a second case, with acute hepatitis secondary to infectious mononucleosis concomitantly infected with hepatitis A. Both cases involved young adults presenting with fever, pharyngitis, lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, and atypical lymphocytosis confirmed by serologic tests, liver biopsy and electron microscopic study.

Keywords: Infectious mononucleosis, Epstein-Barr virus

INTRODUCTION

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) is a herpes virus that is usually transmitted by oropharyngeal secretions and is the causative agent of infectious mononucleosis. More than 90% of the world's population carries EBV as a life-long, latent infection of B lymphocytes [1]. Infectious mononucleosis is caused by an intense cytotoxic T lymphocyte response to eliminate EBV-infected B cells [2]. Usually, primary EBV infection in children is asymptomatic with seroconversion. If primary infection occurs in adolescents or in adulthood, the most common manifestation is infectious mononucleosis with the classic presentation of fever, oropharyngitis, and bilateral lymphadenitis. In the acute phase of infectious mononucleosis, elevated transaminases are found in 80% of patients, while jaundice is noted in only 5.0-6.6% [3]. Hepatitis owing to primary EBV infection is usually mild and self-limited, although the mechanism is unclear. Rarely, it results in hepatic failure with severe jaundice in fatal infectious mononucleosis [4].

Here, we report two cases: the first case with acute hepatitis secondary to infectious mononucleosis, and a second case with acute hepatitis secondary to infectious mononucleosis concomitantly infected with hepatitis A, in young adults presenting with fever, pharyngitis, lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, and atypical lymphocytosis confirmed by serologic test, liver biopsy and electron microscopic study.

CASE REPORT

Case 1

A 20-year-old male was admitted due to nausea, vomiting, fever, myalgia, and sore throat for the past 7 days. He had no history of smoking or alcohol, and no family history of liver disease.

On admission to the hospital, his body temperature was 38.3℃, blood pressure 130/80 mmHg, pulse rate 100 beats per minute, and respiratory rate 20 breaths per minute. Upon physical examination, he appeared acutely ill-looking with bilateral cervical lymph node enlargement. His tonsils were enlarged with white exudates and injection. He was not apparently jaundiced, but was dehydrated. The abdomen was remarkable for splenomegaly. Laboratory findings revealed hemoglobin, 14 g/dL; platelet count, 85,000/mm3; white blood cell count, 13,500/mm3 with 13% granulocytes, 34% atypical lymphocytes. The liver function tests reported aspartate aminotransferase, 532 IU/L; alanine aminotransferase, 412 IU/L; alkaline phosphatase, 583 IU/L; gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase, 235 IU/L, and albumin, 3.6 g/dL. Total bilirubin was 2.1 mg/dL and direct bilirubin was 1.2 mg/dL. The prothrombin time was 12.3 seconds and the activated partial thromboplastin time was 30.3 seconds. Chest radiography showed no active lung lesion. Treatment with amoxicillin for persistent fever was administered empirically.

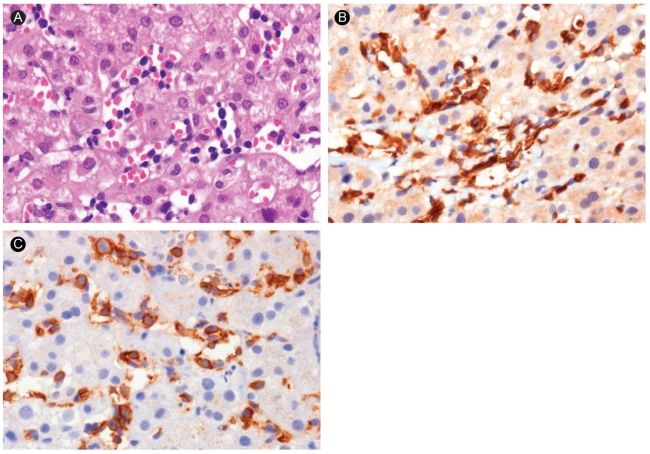

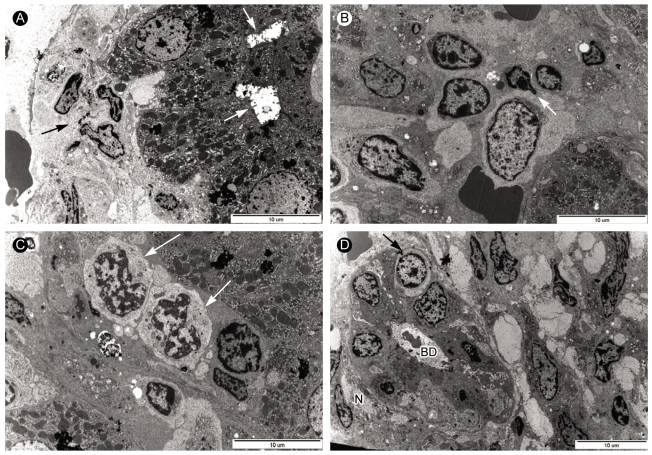

Abdominal sonography showed no change in liver echogenicity and no focal lesion in liver with marked splenomegaly, sized about 18.8 cm. On hospital day 3, a liver biopsy was conducted and the patient was then transferred to the intensive care unit temporarily, due to iatrogenic subcapsular hematoma and hemoperitonium confirmed by CT scan of the abdomen, which resolved spontaneously 10 days later. Serological tests for hepatitis A, B, C, cytomegalovirus (CMV), leptospirosis were negative. Serology for both serum IgM and IgG antibodies against EBV capsid antigen (EBV VCA IgM, IgG) showed positive. Heterophil antibody was negative. The liver biopsy showed infiltration of atypical lymphocytes within sinusoid, and some hepatocytes revealed acidophilic degeneration with frequent mitosis due to regeneration. The lymphocytes were mostly positive for CD3, CD8 cytotoxic T lymphocytes and negative for CD20, CD4 cytotoxic T lymphocytes by immunohistochemistry (Fig. 1). Electron microscopy findings showed degenerated hepatocytes with markedly dilated bile canaliculi and increased collagen fiber bundles in the periportal area (Fig. 2). Large and pale looking atypical lymphocytes with abundant cytoplasm and irregular nucleus could be seen in the sinusoid and portal area. In the portal area, extensive fibrosis and impaired bile ductules were observed with infiltrations of mononuclear cells and macrophages. Ductular lumen contained bleb formation. These findings were consistent with hepatic involvement of infectious mononucleosis. After 2 weeks of conservative treatment, his condition was well and he was discharged without any complications.

Figure 1.

Liver biopsy findings of case 1. (A) Multiple atypical lymphocytes are observed in the sinusoid (H&E, ×400). (B, C) Immunochemical staining shows CD 3 and CD 8 positive T lymphocytes (×400).

Figure 2.

Electron microscopic andiysis of liver biopsy samples from case 1. (A) Electron micrograph displaying degenerated hepatocyte with dilated bile canaliculi (arrow) in the periportal area. The sinusoid contained thick collagen fiber bundles and fibrosis (arrow) (×5,000). (B) Electron micrograph showing a large lymphocyte (arrow) with abundant pale cytoplasm and large nucleus in the sinusoid (×5,000). (C) Electron micrograph showing two atypical lymphocytes (arrows) with abundant cytoplasm and irregular shaped nucleus in the sinusoid. (×8,000). (D) Electron micrograph showing atypical lymphocyte (arrow) and interlobar bile ducts undergoing degenerative injury. Picnotic nuclei (arrow) of bile ductular epithelial cells and bile ductular lumen (BD) containing blebs and scanty microvilli were observed in the portal area with increased collagen fiber bundles (×4,000).

Case 2

A 24-year-old woman presented with a one-week history of fever, sore throat and palpable neck mass. She had lived in Canada for 10 years and was visiting Seoul for summer vacation. She had a recent upper respiratory infection with dry cough and nasal congestion. Recently, she noticed progressive fatigue, malaise, nausea, and vomiting with mildly swollen glands bilaterally. She had no history of dental treatment, blood transfusion or sexual activity in the previous 6 months. She had no family history of liver disease and took no medications. She had a travel history to the countryside for swimming about 10 days previously.

On admission to the hospital, her body temperature was 38℃, blood pressure 120/80 mmHg, pulse rate 104 beats per minute and respiratory rate 20 breaths per minute. Upon physical examination, she appeared acutely ill-looking. She had bilateral posterior cervical adenopathy, which was mobile and nontender. Her tonsils were enlarged with white exudates. Sclera jaundice was prominent. The auscultation of heart and lung were normal. The abdomen was remarkable for moderate hepatomegaly and splenomegaly. Laboratory findings revealed hemoglobin, 12 g/dL; platelet count, 69,000/mm3; white blood cell count, 8,400/mm3 with 10% atypical lymphocytes. Liver function tests reported aspartate aminotransferase, 368 IU/L; alanine aminotransferase, 319 IU/L; alkaline phosphatase, 544 IU/L; gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase, 69 IU/L, and albumin, 3.3 g/dL. Total bilirubin was 4.0 mg/dL and direct bilirubin was 2.4 mg/dL. Chest radiography showed no active lung lesion. Treatment with ceftriaxone was administered for persistent fever and she was treated symptomatically for dehydration.

Abdominal sonography showed the liver to be enlarged with a secondary change of gallbladder wall thickening. The spleen was homogeneously enlarged to 13.5 cm. There was no biliary tree dilatation or pathology. A CT scan of chest and neck revealed several enlarged lymph nodes of suspicious necrotic change at the supraclavicular area, mediastinal area and axillary area. On hospital day 3, neck node and liver biopsy were conducted.

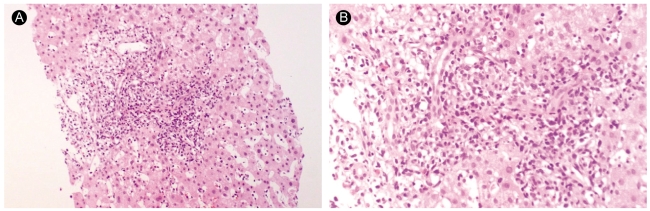

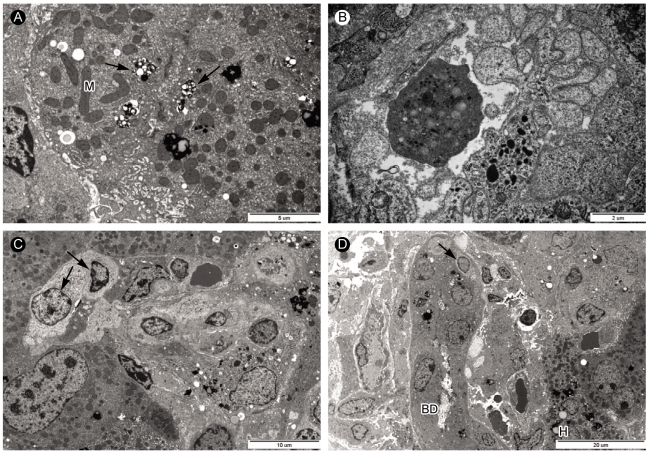

On hospital day 7, her course was complicated by several episodes of fever with negative blood cultures. Serologic and virologic studies revealed the absence of hepatitis B surface antigen, hepatitis B core antibody IgM, hepatitis C antibody, and negative CMV, but positive for hepatitis A virus antibody IgM and EBV VCA IgM, EBV VCA IgG was positive and Epstein-Barr nuclear antigen (EBNA) IgG was negative. The neck node biopsy revealed reactive hyperplasia with inflammation. The liver biopsy revealed dense mononuclear cell infiltration, indicating activated lymphocytes in the portal tract. The hepatic lobular architecture was generally preserved and the lobule showed sinusoidal lymphocytic infiltration, individual hepatocyte degeneration and few spotty necrosis. Portoportal extension due to inflammatory activity and fibrosis was also observed (Fig. 3). Electron microscopic findings showed acute hepatitis, with hepatocytes containing several bile pigments and lipofusin pigments near bile canaliculi in the cytoplasm (Fig. 4). The mitochondria had long paralleled inclusion bodies. An apoptotic body was observed occasionally in the sinusoid. In the sinusoid, mononuclear cells and atypical lymphocytes with a large and pale looking cytoplasm occupied the lumen. In the portal area, bile ducts were also injured with infiltration of atypical lymphocytes and increased collagen fiber bundles. These findings were suggestive of cholestatic hepatitis. Her laboratory test results and physical examination soon improved after two weeks of hospitalization.

Figure 3.

Liver biopsy findings of case 2. The lobule exhibits sinusoidal lymphocytic infiltration, individual hepatocyte degeneration, and few spotty necroses. Some of the portal tract shows dense mononuclear cell infiltration, indicating activated lymphocytes (A: H&E, ×100, B: H&E, ×200).

Figure 4.

Electron microscopic analysis of liver biopsy samples from case 2. (A) Bile pigments (arrows) and lipofusin pigments (arrowhead) were in the cytoplasm near bile canaliculus of hepatocytes. Mitochondria (M) contained long inclusion bodies (×8,000). (B) Apoptotic body in the sinusoid (×15,000). (C) In sinusoid, mononuclear cells occupied the sinusoid lumen in which atypical lymphocytes (arrow) with pale looking and large cytoplasm could be seen (×4,000). (D) Electron micrograph showing atypical lymphocyte (arrow) and portal area with injured bile ductules (BD) with increased collagen fiber bundles. Ductular lumen has a bleb. Hepatocytes contained a lot of lipofusin pigments (×2,500).

DISCUSSION

EBV is part of the herpes virus family and infects up to 90% of the population [1]. Initial infection is often subclinical in children, but will generally result in symptomatic infectious mononucleosis in adults who were not exposed during childhood. Transmission occurs through close personal contact among young children and via intimate oral contact among adults. Transmission by blood transfusion [5] and from a transplanted organ in a previously seronegative recipient [6] have been documented. The most common presentation in infectious mononucleosis is fever, sore throat and adenopathy. Hepatosplenomegaly may be seen in more than 10% of patients [7]. More rare manifestations of infectious mononucleosis include hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, aplastic anemia, myocarditis and neurological complications [8].

Hepatic involvement with infectious mononucleosis varies in severity and its frequency varies with age, which is estimated to be 10% in young adults and 30% in the elderly [9]. EBV infections are often associated with mild hepatocellular hepatitis and can go undetected and resolve spontaneously.

The elevated aminotransferases are usually less than five-fold normal levels, and bilirubin may be elevated in up to 5%, which may be due to intrahepatic cholestasis or hemolytic anemia [10]. In our cases, both immunocompetent adult patients had mild hepatitis with moderate elevation of aminotransferases. In the second case, the patient initially presented with icteric feature, as compared to the first patient, and was later found to be infected concomitantly with infectious mononucleosis and hepatitis A. The incubation period of hepatitis A is 15-45 days, and 30-50 days for EBV infection [11]. Though their transmission routes are different, hepatitis A spreads via the fecal-oral route and infectious mononucleosis spreads via nasopharyngeal secretion, their incubation periods may overlap and these viruses may be acquired at nearly the same time.

Only a few cases of cholestatic hepatitis by EBV infection have been reported [9]. The mechanism for the obstructive component is not well known, but it is assumed to be related to a mildly swollen bile duct [12] rather than an infection of the epithelial cells of the bile duct [13]. EBV infections are rarely associated with acute fulminant hepatic failure. It is characterized by the lymphocytic infiltration of organs, hemophagocytosis and pancytopenia [4]. It may occur, in particular, in immunodeficient states such as X-linked lymphoproliferative disease, human immunodeficiency virus co-infection and complement deficiency [14].

The histological findings of infectious mononucleosis hepatitis include minimal swelling and vacuolization of hepatocytes, as well as infiltration with lymphocytes and monocytes in the periportal area [7]. The sinusoidal invasion by monocytes in an 'Indian Bead' pattern, areas of scattered focal necrosis and proliferation of Kupffer cells, has also been observed [15]. An evaluation of infectious mononucleosis hepatitis has demonstrated that the virus did not infect hepatocytes, biliary epithelium, or vascular endothelium but, rather, the infiltration of CD8 T cells led to indirect hepatic damage [14].

The pathogenesis of infectious mononucleosis hepatitis is not well understood. Traditionally, it has been thought that hepatotropic viruses are not directly cytotoxic but, instead, that the immune responses to viral antigens on hepatocytes result in hepatocyte death. CD3 positive T lymphocytes present as the main lymphocytic population in EBV hepatitis, which are mainly cytotoxic CD8 positive T-lymphocytes [14,16]. A recent animal model [17] showed that activated CD8+ T cells were trapped in the liver selectively, primarily by intracellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1), which is expressed constitutively on sinusoidal endothelial cells and Kupffer cells. In infectious mononucleosis hepatitis, EBV infected CD8+ T cells, presumably activated T cells, may accumulate in the liver. A series of experiments have shown that certain soluble products of the immune response, especially interferon γ, tumor necrosis factor α and Fas ligand, induced hepatitis [18-20]. These products, which are produced by either EBV-infected CD8 + T cells or infiltrating cytotoxic T lymphocytes, may, therefore, induce hepatocyte injury [16].

The diagnosis of EBV infection is made by appropriate clinical symptoms, laboratory findings, and positive EBV IgM antibody and heterophil antibody tests [21]. The EBV-specific serology is a confirmative diagnostic tool, but can be negative initially in patients who have been ill for only a few days at the time of their first visit. However, within 1 to 2 weeks, antibodies to EBV-specific antigens appear at the expected titers [22]. The serology of Anti-VCA IgM generally persists for about 1-2 months. The original serologic test for infectious mononucleosis, the Paul-Bunnell test for detecting heterophil antibodies by agglutination of sheep or horse red blood cells, is now available as a convenient latex agglutination or solid phase immunoassay form [21]. The test is specific, but insensitive during the first weeks of illness. The false negative rate is as high as 25% in the first week, 5-10% in the second week and 5% in the third week [21]. The primary acute EBV infection is associated with VCA-IgM, VCA-IgG, and absent EBNA antibodies [9]. Recent infection in 3 to 12 months includes positive VCA-IgG and EBNA antibodies, negative VCA-IgM antibodies, and usually positive EA antibodies [9]. Infectious mononucleosis hepatitis should be differentiated from other viral hepatitis A, B, C, HIV, CMV, varicella zoster virus and herpes simplex virus [7]. In the present two cases, the patients were in acute phase of EBV infection and the diagnosis was based on typical symptoms, including atypical lymphocytosis, elevated liver enzymes, serologic marker of positive anti-EBV IgM and, subsequently, IgG with mononuclear cell infiltration of the portal tract and sinusoids in liver biopsy.

Treatment for infectious mononucleosis hepatitis is usually supportive as it is generally self-limiting. Steroids and antiviral medications have been utilized to treat cases of severe infectious mononucleosis hepatitis. Acyclovir has not been shown to be efficacious for the treatment of severe EBV hepatitis [23]. There is a case report of the successful use of ganciclovir in two immunocompetent patients with severe infectious mononucleosis hepatitis [10]. However, randomized studies have not been performed for all of these treatments of infectious mononucleosis hepatitis. In our cases, both patients soon recovered with only conservative treatment.

EBV is a rare causative agent of acute hepatitis, during the course of infectious mononucleosis. Usually, it is mild, undetected clinically and resolves spontaneously. Jaundice is distinctly uncommon; cholestatic hepatitis due to EBV infection is rarely reported. We should consider infectious mononucleosis hepatitis in differentiating patients presenting with liver abnormality, fever, pharyngitis, and lymphadenopathy.

References

- 1.Macsween KF, Crawford DH. Epstein-Barr virus-recent advances. Lancet Infect Dis. 2003;3:131–140. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(03)00543-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rickinson AB, Kieff E. Epstein-Barr virus. In: Knipe DM, Howly PM, editors. Virology. 4th ed. vol. 2. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2001. pp. 2575–2627. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Markin RS. Manifestations of Epstein-Barr virus-associated disorders in liver. Liver. 1994;14:1–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0676.1994.tb00001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Markin RS, Linder J, Zuerlein K, et al. Hepatitis in fatal infectious mononucleosis. Gastroenterology. 1987;93:1210–1217. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(87)90246-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paloheimo JA, Halonen PI. A case on mononucleosis-like syndrome after blood transfusion from a donor with symptomatic mononucleosis. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino) 1965;6:558–561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cen H, Breinig MC, Atchison RW, Ho M, McKnight JL. Epstein-Bar virus transmission the donor organs in solid organ transplantation: polymerase chain reaction and restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis of IR2, IR3 and IR4. J Virol. 1991;65:976–980. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.2.976-980.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Curm NF. Epstein Barr virus hepatitis: cases series and review. South Med J. 2006;99:544–547. doi: 10.1097/01.smj.0000216469.04854.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen JI. Epstein-Barr virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:481–492. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200008173430707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lawee D. Mild infectious mononucleosis presenting with transient mixed liver disease. Can Fam Physician. 2007;53:1314–1316. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adams LA, Deboer B, Jeffrey G, Marley R, Garas G. Ganciclovir and the treatment of Epstein-Barr virus hepatitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;21:1758–1760. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.03257.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karagoz G, Ak O, Ozer S. The coexistence of hepatitis A and infectious mononucleosis. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2005;16:102–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nelson RS, Darragh JH. Infectious mononucleosis hepatitis: a clinicopathologic study. Am J Med. 1956;21:26–33. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(56)90005-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feranchak AP, Tyson RW, Narkewicz MR, Karrer FM, Sokol RJ. Fulminant Epstein-Barr viral hepatitis: orthotopic liver transplantation and review of the literature. Liver Transpl Surg. 1998;4:469–476. doi: 10.1002/lt.500040612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kimura H, Nagasaka T, Hoshino Y, et al. Severe hepatitis caused by Epstein-Barr virus without infection of hepatocytes. Hum Pathol. 2001;32:757–762. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2001.25597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hinedi TB, Koff RS. Cholestatic Hepatitis Induced by Epstein-Barr virus infection in an adult. Dig Dis Sci. 2003;48:539–541. doi: 10.1023/a:1022592801060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hara S, Hoshino Y, Naitou T, et al. Association of virus infected-T cell in severe hepatitis caused by primary Epstein-Barr virus infection. J Clin Virol. 2006;35:250–256. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2005.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mehal WZ, Juedes AE, Crispe IN. Selective retention of activated CD8+ T cells by the normal liver. J Immunol. 1999;163:3202–3210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kusters S, Gantner F, Kunstle G, Tiegs G. Interferon gamma plays critical role in T cell-dependent liver injury in mice initiated by concanavalin A. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:462–471. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v111.pm8690213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bradham CA, Plumpe J, Manns MP, Brenner DA, Trautwein C. Mechanisms of hepatic toxicity. I. TNF-induced liver injury. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:G387–G392. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1998.275.3.G387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kondo T, Suda T, Fukuyama H, Adachi M, Nagata S. Essential roles of the Fas ligand in the development of hepatitis. Nat Med. 1997;3:409–413. doi: 10.1038/nm0497-409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ebell MH. Epstein-Barr virus infectious mononucleosis. Am Fam Physician. 2004;70:1279–1290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fleisher GR, Collins M, Fager S. Limitations of available tests for diagnosis of infectious mononucleosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1983;17:619–624. doi: 10.1128/jcm.17.4.619-624.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hart GK, Thompson WR, Schneider J, Davis NJ, Oh TE. Fulminant hepatic failure and fatal encephalopathy associated with Epstein-Barr virus infection. Med J Aust. 1984;141:112–113. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1984.tb132717.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]