Abstract

Disease progression after nephrectomy for pathologically localized renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is associated with a significant mortality rate, given the limited efficacy of available treatment regimens for metastatic disease. As such, several adjuvant trials have been designed to treat patients at particularly high risk for post-surgical RCC progression. Several different prognostic models designed to identify patients at high risk of disease progression are available. Although these available predictive models provide a reasonable assessment of patients’ risks of disease progression, the accuracy of these models may further be improved via the incorporation of molecular prognostic biomarkers. Although numerous candidate molecules have been described, few have been specifically assessed for the association with disease progression after nephrectomy. IMP-3, CXCR3, p53, Survivin, cIAP1, B7-H1, and B7-H4 have all been associated with disease progression after nephrectomy. The incorporation of 1 or several of these biomarkers may increase the accuracy of currently available prognostic models and thereby facilitate the appropriate use of adjuvant therapies aimed at preventing future disease progression. As such, the authors review the current prognostic tools for predicting disease progression for localized RCC, and detail studies to date that have evaluated various biomarkers in this setting.

Keywords: renal cell carcinoma, molecular biomarkers, prognosis, disease progression, adjuvant trials

The routine use of cross-sectional abdominal imaging has led to a significant increase in the diagnosis of renal cell carcinoma (RCC).1 An estimated 51,000 new cases of cancer of the kidney and renal pelvis were diagnosed in 2007, with the vast majority representing RCC.2 Although the rate of metastatic RCC at initial presentation remains substantial, the incidence of asymptomatic, pathologically localized RCC has demonstrated the greatest increase.3 Despite the finding of pathologically confined disease at the time of nephrectomy, 10% to 28% of patients will demonstrate local recurrence or distant metastasis after nephrectomy.4-7 Unfortunately, the development of metastatic RCC is associated with a dismal prognosis, and treatment options are limited. The median cancer-specific survival for patients with recurrent RCC is 21 months, with 5-year survival rates ranging between 0% to 69% depending on the patient’s risk factors at the time of disease recurrence.7,8 Recently introduced tyrosine kinase inhibitors are associated with overall high rates of response for the treatment of metastatic RCC; however, associated response rates are not durable and improvements in the median survival are relatively modest9,10 compared with response rates provided by cytokine therapy.11

Prompted by the substantive rate of cancer progression in patients with pathologically localized disease, as well as the low rate of survival for patients with metastatic RCC, several clinical trials have been initiated to investigate the efficacy of adjuvant therapy for high risk patients to preempt cancer recurrence or progression after nephrectomy. Although all of the current adjuvant trials have a common primary endpoint, namely, progression-free survival, each trial has unique inclusion criteria owing to the lack of uniform methods to identify patients who are at greatest risk for disease progression after surgical extirpation of pathologically localized RCC. In response to this, several prognostic models to predict risk of progression after surgery have been developed. Each of these prognostic models is based on several clinicopathologic variables noted at the time of nephrectomy. Although these models are able to identify the majority of patients destined to demonstrate disease progression after nephrectomy, there are clearly a significant number of patients whose risk is inappropriately assigned using existing models. This point is particularly important when considering adjuvant trial design. For this and other reasons, investigators have attempted to identify molecular biomarkers associated with RCC outcomes to improve the risk stratification of patients at the time of nephrectomy. Although a multitude of biomarkers have been reported to predict cancer-specific survival, few have been associated with disease progression after nephrectomy for pathologically localized cancer.12 Herein, we review the available prognostic models for disease progression in pathologically localized RCC, inclusion criteria of contemporary adjuvant trials, and molecular biomarkers that have demonstrated potential in predicting disease progression after nephrectomy.

Contemporary Adjuvant Trials for RCC

Advances in our understanding of the molecular pathways involved in the pathophysiology of RCC have led to the development of several new therapeutic agents. Dysregulation of the hypoxia-inducible factor pathway leads to the generation of multiple factors, including increased expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), Platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), and carbonic anhydrase IX, which enable tumor cells to overcome and proliferate in hypoxic conditions. Available oral tyrosine kinase inhibitors (sunitinib and sorafenib) target VEGF and PDGF receptors and have demonstrated efficacy in the treatment of metastatic RCC.9,13 In contrast, the monoclonal antibody cG250 targets carbonic anhydrase IX, which is expressed in 94% to 97% of clear cell RCC (ccRCC) specimens.14-16 At present, there are 3 clinical trials investigating the efficacy of tyro- sine kinase inhibitors and 1 clinical trial investigating the efficacy of cG250 in preventing disease progression after nephrectomy (Table 1). Complete details regarding trial eligibility and participating institutions can be found at www.clinicaltrials.gov.

TABLE 1. Contemporary Adjuvant Trials for High-risk Localized RCC.

| Trial start date |

Projected accrual |

Pathologic inclusion criteria | Agents investigated | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ARISER (NCT00087022) |

2004 | 856 |

|

|

| ASSURE (NCT00326898) |

2006 | 1332 |

|

|

| SORCE (NCT00492258) |

2007 | 1656 |

|

|

| S-TRAC (NCT00375674) |

2007 | 228 |

|

|

RCC indicates renal cell carcinoma; ccRCC, clear cell RCC.

As with all clinical trials, the success of trials investigating adjuvant therapies for RCC will be predicated on both the efficacy of the therapeutic agent being investigated as well as purity of truly ‘high risk’ RCC patients being enrolled in study to ensure an early and predictable timeframe to monitor disease progression after nephrectomy.17 Interestingly, all 4 contemporary adjuvant trials use different pathologic inclusion criteria for enrollment (Table 1), which in essence reflects the imprecision of current definitions of ‘high risk’ RCC. This is particularly sobering given that these inclusion criteria are of utmost importance to ensure that sufficient numbers of truly high-risk RCC patients are accrued onto study (and will demonstrate disease progression) to assess the study agent’s efficacy in an accurate and timely fashion. For example, if too many low-risk patients are inadvertently accrued onto study, time-to-progression (as well as the overall duration of the study) would be unnecessarily prolonged and could potentially confound the interpretation of the study agents effectiveness as several studies have demonstrated that time to progression is associated with stage at the time of nephrectomy.18

Prognostic Models for Predicting Disease Recurrence

In the past, the identification of patients at risk for disease progression after nephrectomy was important primarily for counseling patients regarding prognosis and to guide the timing of disease surveillance.19,20 However, with the promise of more effective adjuvant therapies, prognostic models designed to predict disease progression after nephrectomy have an even greater potential application. Currently, several prognostic models are available that assess the risk of disease progression after nephrectomy, several of which are listed in Table 2. Although other prognostic models are available to help predict disease recurrence after nephrectomy, these additional models are based solely on preoperative variables and have been noted to be inferior in their ability to predict disease progression compared with models that include pathologic tumor features.21-23 At the same time, several well-recognized prognostic models designed to predict cancer-specific survival, including the UISS and SSIGN scoring systems, have been developed. However, these prognostic tools were created with the inclusion of patients who had metastatic disease at the time of nephrectomy, which limits their application to predict disease progression after nephrectomy for pathologically localized tumors, which is the focus of this review.7,24

TABLE 2. Prognostic Models for Predicting Disease Recurrence.

| Authors | Institution | Risk definition |

Tumor histology |

Nephrectomy | Years | Clinical variables |

Pathologic variables |

Location of recurrence |

Timepoint, y | Accuracy (c Index) |

External validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kattan 20014 | MSKCC | Nomogram | Papillary, chromophobe, ccRCC |

Partial and Radical |

1989–1998 | Disease related symptoms |

Histologic subtype, tumor size, pT stage |

Local, distant, asynchronous contralateral disease |

5 | 0.74 | No |

| Sorbellini 20056 | MSKCC | Nomogram | ccRCC | Partial and Radical |

1989–2002 | Disease related symptoms |

Tumor size, pT stage, grade, necrosis, vascular invasion |

Local, distant, asynchronous contralateral disease |

5 | 0.82 | Yes |

| Leibovich et al26 | Mayo Clinic | Algorithm | ccRCC | Radical | 1970–2000 | pT stage, lymph node status, tumor size, nuclear grade, histologic tumor necrosis |

Distant | 1,3,5,7,10 | 0.82 | No | |

| Zisman 20027 | UCLA | Algorithm | All RCC variants | Partial and Radical | 1989–2000 | ECOG PS | TNM stage, Fuhrman grade |

Local and distant | 1,2,3,4,5 | NA | No |

MSKCC indicates Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center; ccRCC, clear cell renal cell carcinoma; UCLA, University of California at Los Angeles.

The first model for predicting disease progression was proposed by Kattan et al.4 who developed a nomogram based on data from Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC). The study population included 601 patients with T1–3cN0/XM0 disease. It is important to note that this nomogram can be applied to patients with clear cell (cc), papillary, and chromophobe RCC variants, but does not account for nuclear grade. RCC recurrence was defined as local or distant recurrence, or the development of an asynchronous, contralateral renal tumor. The same authors subsequently developed a postoperative nomogram that focused solely on ccRCC.6 This nomogram was generated from a population of 701 T1–3cN0/XM0 ccRCC patients treated at MSKCC. In addition to focusing on ccRCC, this nomogram differed from the prior nomogram with the incorporation of additional prognostic features such as tumor necrosis, microvascular invasion, nuclear grade, as well as the 2002 American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system. External validation was performed by the authors using 200 ccRCC patients from a separate nephrectomy registry, demonstrating the nomogram’s generalizability. A recognized limitation to the MSKCC nomograms is the prediction of progression at a maximum of 5 years after nephrectomy. By limiting the nomogram’s prediction of disease progression to 5 years after nephrectomy, it does not account for the 15% to 19% of patients who demonstrate disease progression greater than 5 years following nephrectomy for localized disease.5,25

A prognostic model predicting metastasis-free survival based on the outcomes of patients undergoing radical nephrectomy for localized ccRCC was reported by Leibovich et al.26 at the Mayo Clinic. In this model, pathologic features of the nephrectomy specimen are used to calculate a score, between 0 and 11, which provides estimated metastasis-free rates at 1, 3, 5, 7, and 10 years. Further stratification based on these scores places patients into low, intermediate, and high risk groups for disease progression. In the Mayo model, local recurrence is not considered, whereas the MSKCC nomograms do account for local recurrences. Another prognostic model for disease recurrence after nephrectomy for pathologically localized RCC was designed by Zisman et al.7 This algorithm stratifies patients into low, intermediate, and high risk categories based on ECOG performance status and pathologic variables at the time of nephrectomy. This model provides probabilities for freedom from local or distant recurrence at 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 years.

Thus, several prognostic models are available, and all are based on clinicopathologic features associated with RCC outcomes. However, the application of these models to assess risk for individual patients must be tempered by a clear understanding of the populations from which each of these models were derived. Important considerations include pathologic features incorporated into each model, standard-of-care and prevailing therapeutic approaches at the time each model was created, and the overall prognostic accuracy of the model. Clearly, if an individual patient has been treated for a histologic variant other than ccRCC, using a prognostic model that was generated exclusively based on ccRCC patients would not be as applicable as a model that accounts for the histologic RCC subtype under investigation. In addition, prognostic models that are not regularly updated, or that were created based on RCC populations with relatively high percentages of advanced cancer patients may not prove to be accurate risk stratification tools for contemporary patients who tend to present with localized disease. Given that more patients are presenting with pathologically localized disease, we will surely need to identify a means to further stratify the growing number of patients who were all previously considered ‘low’ risk. Lastly, the ability of a prognostic model to accurately identify which patients will demonstrate disease progression is an important consideration during postoperative counseling and when considering adjuvant trials. The accuracy of a prognostic model can be expressed by the concordance index (c index).27 The c index is used to measure a prognostic model’s ability to predict an event, with a value of 0.5 representing no discriminatory ability and 1.0 being perfect. Table 2 provides the c index of the available prognostic models. Although the currently available prognostic models provide reasonable accuracy in regard to the c index, clearly there is room for improvement. Improvements in the accuracy of an individual model’s ability to predict disease progression after nephrectomy for RCC may be accomplished through the incorporation of molecular biomarkers. This principle has recently been demonstrated in predicting disease recurrence after cystectomy for urothelial cancer by Shariat et al.28

Molecular Biomarkers Associated With RCC Cancer-specific Survival

Although the focus of the current review is on predictors of disease progression after nephrectomy for pathologically localized disease, a significant number of molecular biomarkers have been associated with cancer-specific survival in patients with RCC. However, in the series evaluating cancer-specific survival after nephrectomy the inclusion of patients with metastatic disease prohibits the assessment of the biomarkers ability to predict disease progression. Although a detailed review of such biomarkers is beyond the scope of this review, manuscripts by Lam et al.29 and Nogueria and Kim12 provide excellent reviews of molecular biomarkers predictive of cancer-specific survival in RCC.

Molecular Biomarkers Associated With RCC Progression

Molecular biomarkers can assist with the diagnosis of a malignancy, may represent potential therapeutic targets, and may offer a means to monitor disease recurrence after treatment. Moreover, selected biomarkers may prove useful when incorporated into existing risk stratification models to help clinicians more accurately counsel patients regarding disease prognosis. The heterogeneous behavior of RCC makes the identification and development of molecular biomarkers particularly attractive. Although conventional clinical and pathologic indices provide reasonable accuracy in predicting disease-specific outcomes after nephrectomy, molecular biomarkers may serve to enhance the accuracy of existing prognostic models.29 In order for a biomarker to be useful in routine practice, however, it must provide information that is not obtained by the currently available prognostic indices for RCC.30

Multiple series have investigated the ability of molecular biomarkers to predict cancer-specific mortality in RCC; however, few have focused on predictors of disease progression after nephrectomy for pathologically localized disease. In identifying potential biomarkers for RCC, investigators have focused on key processes of tumorigenesis, including antitumoral immune evasion, apoptosis resistance, and cell cycle regulation. As the focus of the present review is on biomarkers of disease progression, molecular biomarkers that have not been specifically associated with disease progression after surgery will not be discussed here. However, future analysis of molecular biomarkers that have been associated with cancer-specific survival may prove to be of value when analyzed for predicting progression-free survival. For example, several molecular biomarkers that have been noted to be independent predictors of cancer-specific survival in RCC after nephrectomy have not been found to be significantly associated with disease-free progression. In particular, Ki-67, carbonic anhydrase IX, and vimentin have all been suggested to be significantly associated with cancer-specific survival on multivariate analysis, but were not independent predictors of disease progression after nephrectomy for pathologically localized tumors.12,31 To this end, we have selected those molecular biomarkers that have been specifically associated with disease progression in RCC after attempted extirpative surgery for discussion here. Table 3 outlines associations between conventional prognostic indices and the molecular biomarkers discussed below. Figure 1 depicts representative immunohistochemical staining for several biomarkers predictive of RCC disease progression after nephrectomy.

TABLE 3. Associations Between Conventional Prognostic Indices and Molecular Biomarkers.

| Sex | Age | ECOG pS | Symptoms at presentation |

Tumor size | Nuclear grade | Stage | Histology | Nodal status | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IMP-3 | + | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| CXCR3 | NA | NA | − | NA | − | − | − | NA | NA |

| P53 | − | − | NA | NA | NA | +/− | − | + | NA |

| cIAP1 | + | − | NA | NA | NA | − | + | − | NA |

| Survivin | − | − | − | − | +/− | + | + | NA | +/− |

| B7-H1 | NA | NA | − | NA | + | + | + | NA | − |

| B7-H4 | − | − | NA | + | + | + | + | NA | + |

Associations of clinicopathologic features with candidate biomarkers for RCC.

+ indicates positive association; − not significant; NA, not available.

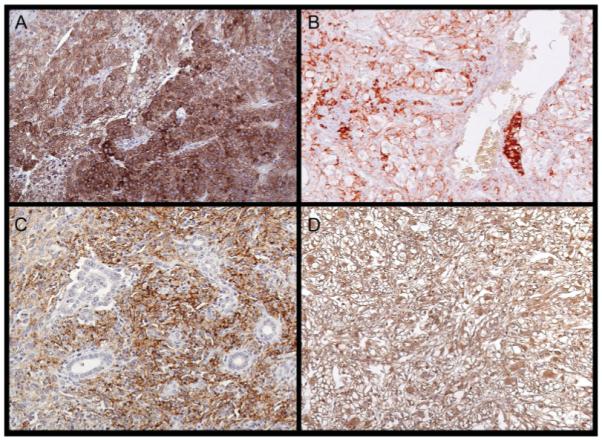

FIGURE 1.

Immunohistochemical staining of molecular biomarkers is shown in ccRCC specimens, (A) IMP-3, (B) Survivin, (C) B7-H1, and (D) B7-H4.

IMP-3

Aberrant expression of the insulin-like growth factor mRNA binding protein (IMP) family member IMP-3 has been demonstrated in several human malignancies.32-34 The role of IMP-3 in tumorigenesis is suspected to involve the promotion of cellular proliferation.35,36 In RCC, increased IMP-3 expression has been noted in 17% of tumors, and correlates with tumor stage, size, nuclear grade, and histologic subtype. IMP-3 expression was also observed to be a significant independent predictor of metastasis-free and overall survival after multivariate adjustment. Specifically, of the primary tumors that were positive for IMP-3, 85% (60 of 71) were associated with metastatic disease at the time of, or after nephrectomy. In this series, 371 patients had pathologically localized disease at the time of nephrectomy, of which 15% (54 of 371) stained positive for IMP-3. Among this subgroup of patients, 80% (43 of 54) demonstrated disease progression at a median follow-up of 38 months, compared with only 13% (41 of 317) of patients with IMP-3-negative tumors.37 In addition, the 5-year progression-free survival rate was significantly lower in IMP-3-positive tumors (33%) compared with IMP-3-negative tumors (89%). This relationship was also noted for each stage of RCC, with 5-year progression-free rates of 44% versus 98%, 41% versus 94%, and 16 versus 62% for stage I, II, and III IMP-3-positive and -negative tumors, respectively. Most important, these findings have recently been externally validated as reported by Hoffmann et al.38 In this series, 716 consecutive ccRCC specimens were examined for IMP-3 expression, 88% (629 of 716) of which had pathologically localized disease at the time of nephrectomy. Of pathologically localized tumors, 26% (163 of 629) stained positive for IMP-3. Five- and 10-year progression-free survival rates were significantly lower in IMP-3-positive tumors compared with IMP-3-negative tumors (51% and 41% vs 89% and 82%, respectively). The association between positive IMP-3 expression and decreased progression-free survival remained intact even after multivariate adjustment for symptoms at presentation, sarcomatoid differentiation, and the metastases-free survival score.24,26

CXCR3

The chemokine receptor CXCR3 has recently been described as an independent predictor of progression-free survival after nephrectomy in 154 patients with pathologically localized disease. In a single-institution, retrospective series, 96% of pathologically localized RCC specimens stained positive for CXCR3.39 Although CXCR3 expression was not correlated with adverse pathologic features of the primary tumor, decreased CXCR3 expression was significantly associated with a decreased progression-free survival. That is, the 5-year progression-free survival was significantly decreased in patients with low expression (57%) compared with those with high expression (82%). On multivariate analysis, patients with decreased CXCR3 expression remained 2.5 times more likely to demonstrate disease progression after nephrectomy.

p53

Expression of p53, a key regulator of the cell cycle, has been shown to be altered in several human malignancies. Mutations of p53 are associated with decreased DNA binding and an extended half-life that leads to the accumulation of p53 within the cell.40 Thus, the detection of increased p53 expression denotes abnormal function and potential dysregulation of the cell cycle. Significant associations of altered p53 expression with pathologic features, disease progression, and cancer-specific survival in RCC have been noted in several series.41-46 p53 expression has also been found to differ significantly between histologic subtypes of RCC, with papillary RCC having the greatest incidence of abnormal expression.45 Moreover, p53 expression was noted to be significantly increased in metastatic lesions compared with primary tumor specimens.44,45

One previous study specifically investigated the ability of p53 expression to predict tumor progression after surgical resection of localized RCC in 193 patients using immunostaining of tissue microarrays.46 Five-year progression-free survival was significantly decreased in tumors with high p53 expression compared with tumors with low expression (62.3% vs 85.6%). On multivariate analysis, p53 expression remained a significant predictor of disease progression. A second series that evaluated the association between p53 expression and disease progression in 184 primary tumor specimens was reported by Zigeuner et al.45 Although the median patient follow-up was relatively short at 26 months, a significant association between disease progression and p53 expression was noted, as the progression-free survival was 65% for tumors with high p53 expression compared with 89% in tumors with low expression. However, when progression-free survival was evaluated in individual histologic subtypes, a significant association between progression-free survival and p53 expression was only noted in patients with ccRCC. Despite the 2 studies previously discussed, the series investigating disease progression reported by Phuoc et al.41 failed to note a significant association between p53 expression and disease progression on multivariate analysis.

cIAP1

cIAP1 is a class 1 inhibitor of apoptosis protein that inhibits caspase activity and other cell regulatory processes. Altered expression of cIAP1 has been reported in several malignancies, including RCC.47 In a series of 104 consecutive RCC specimens, cIAP1 expression was noted in 100% of tumors and in 99% of adjacent normal renal parenchyma. Overall, median cIAP1 expression was 2.4-fold higher in malignant compared with normal tissue. However, 20.2% of tumors evaluated demonstrated decreased cIAP1 expression relative to adjacent normal renal parenchyma. A decreased tumor/normal (T/N) tissue cIAP1 expression ratio was associated with increased tumor stage and with postoperative disease progression, such that the estimated 5-year progression-free survival rate was 17% for patients with a cIAP1 T/N ratio <1, compared with 92% for patients with a T/N ratio ≥1.

Survivin

Survivin is an antiapoptotic protein that is overexpressed in almost all human malignancies, and has been rarely detected in normal tissue. Survivin is believed to inhibit both the intrinsic and extrinsic caspase cascades. Survivin expression has been correlated with several adverse pathologic features in ccRCC including tumor size, nuclear grade, TNM classification, presence of metastatic disease, coagulative tumor necrosis, and sarcomatoid differentiation.48,49 Moreover, in a series by Parker et al.48 312 patients with high survivin expression were twice as likely to die from ccRCC compared with patients with low survivin expression. A subset analysis of 273 patients with pathologically localized disease at the time of nephrectomy revealed that high survivin expression was predictive of future disease progression, such that the 5-year progression-free survival was 58.8% in patients with high survivin expression versus 86.6% in patients with low survivin expression. Similar results were noted in a series of 85 patients reported by Byun et al.,49 for while no patients from that series with low survivin expression experienced disease progression, 35% of patients with high survivin expression demonstrated progression during a median follow-up of 45 months after nephrectomy. The 5-year progression-free survival rate was 76% in patients with high survivin expression compared with 100% in patients with low survivin expression.

B7 Family Members

B7 family members are involved in the induction and modulation of host immune cell responses.50 Aberrant expression of B7 family members such as B7-H1 and B7-H4 have been demonstrated in several human malignancies, including RCC.51-56 B7-H1 (PD-L1, programmed death ligand-1) is a cell surface glycoprotein normally expressed only by cells of the macrophage lineage.57 Although B7-H1 has been shown to exert both a positive and negative influence on the physiologic T-cell response, aberrant tumor expression of B7-H1 has been consistently associated with inhibition of the immune system, and B7-H1 may in addition function to confer resistance to immunotherapy.58,59 Specifically, initial investigation demonstrated B7-H1 expression in primary and metastatic sites of ccRCC and found that expression was associated with adverse pathologic features at the time of nephrectomy and a decreased 3-year cancer-specific survival.54 Further investigation of a population of 306 patients undergoing nephrectomy for ccRCC with a median follow-up of 10 years was then performed.60 Positive B7-H1 expression was present in 24% of all patients, and was significantly associated with the rate of disease progression in patients with pathologically confined disease. That is, the 5-year progression-free survival was 56.5% in patients with B7-H1-positive tumors compared with 86% in patients with B7-H1-negative tumors. In addition, positive B7-H1 expression was associated with a decreased time to disease progression of 0.7 years compared with 2.9 years in B7-H1-negative tumors.60 Moreover, immunohistochemical analysis of renal tumors that contained infiltrates of mononuclear immune cells positive for PD-1 (a known receptor for B7-H1) were associated with significantly worse tumor stage and cancer-specific survival.61

B7-H4, another T cell coregulatory molecule, has also been implicated in immune system evasion by tumors. For example, in a series of 259 ccRCC specimens, 59% of tumors stained positive for B7-H4. B7-H4 expression was associated with increased tumor size, pathologic stage, nuclear grade, lymph node involvement, coagulative necrosis, and lymphocytic infiltration.51 Moreover, 3-year progression-free survival was significantly associated with B7-H4 expression (74.1% in tumors expressing B7-H4 vs 91.2% in B7-H4-negative tumors).

However, although B7-H1 and B7-H4 have demonstrated strong independent associations with disease progression, not all patients with tumors expressing these molecules perform poorly. Therefore, to identify those tumors that are potentially more biologically aggressive, a combined analysis of both B7-H1 and B7-H4 expression was performed.51,62 In that study, patients whose tumors expressed both B7-H4 and B7-H1 were noted to be significantly more likely to experience disease progression compared with patients with tumors that expressed neither molecule or were positive only for B7-H4 or B7-H1 alone. Similarly, a separate study assessed the association of the combined tumor expression of B7-H1 and survivin on disease progression after nephrectomy. Tumors that expressed both B7-H1 and high levels of survivin demonstrated a significantly decreased 5-year progression-free survival of 43.3% compared with 89.8%, 70.3%, and 68.2% in patients with B7-H1-negative/survivin low, B7-H1-negative/survivin high, and B7-H1-positive/survivin low tumors, respectively.62

Limitations of Molecular Biomarkers

Despite the promise of incorporating molecular biomarkers in clinical practice, several current limitations must be noted. Of the molecular biomarkers described above, all require histopathologic assessment of the tumor specimen that excludes the use of the biomarker in disease surveillance and as a means of monitoring response to subsequent therapy. The identification and development of serum- and urine-based molecular biomarkers may provide a means of enhancing disease surveillance and treatment response.63-65 In addition, although several biomarkers have now been associated with disease progression after nephrectomy for RCC, few have undergone external validation. External validation of a potential biomarker is necessary because of various limitations intrinsic to any single-institutional study that often includes a lack of generalizability.66 Generalizability refers to the ability of a predictive marker to remain accurate among different patient series.67 Additional consideration must be paid to the methods used in assigning predictive value to a candidate biomarker. In order for a biomarker to be of value it should offer prognostic information not provided by available clinicopathologic indices, which can be demonstrated through an improvement in a given predictive model’s concordance index.68 Furthermore, the assessment and interpretation of biomarker expression must be standardized and reproducible. Lastly, the cost of analyzing molecular biomarkers must be taken into account, especially considering the reasonable accuracy of prognostic models based on conventional and readily accessible clinicopathologic indices.

Prognostic Models Incorporating Molecular Biomarkers

Despite the ever-expanding accumulation of data pertaining to biomarkers, only 1 attempt to incorporate molecular biomarkers into a standardized RCC staging system has been reported. Kim et al.69 explored the benefit of adding molecular biomarkers to commonly accepted clinical and pathologic indices in predicting disease-specific survival after nephrectomy. The incorporation of p53, CAIX, and vimentin with clinical and pathologic indices significantly improved the accuracy of predicting disease-specific survival after nephrectomy compared with the University of California Los Angeles integrated staging system. Although this series investigated cancer-specific survival and included patients with metastatic disease opposed to disease progression in patients with pathologically localized disease, this study demonstrates that molecular biomarkers may prove useful to improve the accuracy of existing nomograms used in RCC. In addition, this model demonstrates how the incorporation of multiple biomarkers can improve the predictive ability of particular model compared with the use of a single biomarker.30

Conclusions

Disease progression after nephrectomy for RCC continues to occur in a significant proportion of patients who have pathologically localized disease, and is associated with a significant mortality rate. As such, the need to accurately identify those patients at high risk for disease recurrence and subsequent progression, who might benefit from early intervention provided via enrollment onto a clinical adjuvant therapy trial, will prove vital to extending long-term survival of RCC patients. Although multiple current prognostic models based on clinicopathologic variables exist, further improvements in the accuracy of these models may be attained through the incorporation of molecular prognostic biomarkers. Such accuracy is particularly important when considering the potential morbidity of overtreating patients with adjuvant therapy who are not likely to experience disease progression or undertreating those patients who will certainly progress and die of their disease.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chow WH, Devesa SS, Warren JL, Fraumeni JF., Jr. Rising incidence of renal cell cancer in the United States. JAMA. 1999;281:1628–1631. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.17.1628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Murray T, Xu J, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2007. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57:43–66. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.57.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hock LM, Lynch J, Balaji KC. Increasing incidence of all stages of kidney cancer in the last 2 decades in the United States: an analysis of surveillance, epidemiology and end results program data. J Urol. 2002;167:57–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kattan MW, Reuter V, Motzer RJ, Katz J, Russo P. A postoperative prognostic nomogram for renal cell carcinoma. J Urol. 2001;166:63–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levy DA, Slaton JW, Swanson DA, Dinney CP. Stage specific guidelines for surveillance after radical nephrectomy for local renal cell carcinoma. J Urol. 1998;159:1163–1167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sorbellini M, Kattan MW, Snyder ME, et al. A postoperative prognostic nomogram predicting recurrence for patients with conventional clear cell renal cell carcinoma. J Urol. 2005;173:48–51. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000148261.19532.2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zisman A, Pantuck AJ, Wieder J, et al. Risk group assessment and clinical outcome algorithm to predict the natural history of patients with surgically resected renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:4559–4566. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.05.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eggener SE, Yossepowitch O, Pettus JA, Snyder ME, Motzer RJ, Russo P. Renal cell carcinoma recurrence after nephrectomy for localized disease: predicting survival from time of recurrence. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3101–3106. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.8280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Motzer RJ, Michaelson MD, Redman BG, et al. Activity of SU11248, a multitargeted inhibitor of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor and platelet-derived growth factor receptor, in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:16–24. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.2574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haas NB, Uzzo RG. Targeted therapies for kidney cancer in urologic practice. Urol Oncol. 2007;25:420–432. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Tomczak P, et al. Sunitinib versus interferon alfa in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:115–124. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nogueira M, Kim HL. Molecular markers for predicting prognosis of renal cell carcinoma. Urol Oncol. 2008;26:113–124. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2007.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilhelm SM, Carter C, Tang L, et al. BAY 43-9006 exhibits broad spectrum oral antitumor activity and targets the RAF/MEK/ERK pathway and receptor tyrosine kinases involved in tumor progression and angiogenesis. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7099–7109. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu Z, Smyth FE, Renner C, Lee FT, Oosterwijk E, Scott AM. Anti-renal cell carcinoma chimeric antibody G250: cytokine enhancement of in vitro antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2002;51:171–177. doi: 10.1007/s00262-002-0268-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leibovich BC, Sheinin Y, Lohse CM, et al. Carbonic anhydrase IX is not an independent predictor of outcome for patients with clear cell renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4757–4764. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bui MH, Seligson D, Han KR, et al. Carbonic anhydrase IX is an independent predictor of survival in advanced renal clear cell carcinoma: implications for prognosis and therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:802–811. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Halabi S. Statistical considerations for the design and analysis of phase III clinical trials in prostate cancer. Urol Oncol. 2008;26:300–307. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2006.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lam JS, Shvarts O, Leppert JT, Pantuck AJ, Figlin RA, Belldegrun AS. Postoperative surveillance protocol for patients with localized and locally advanced renal cell carcinoma based on a validated prognostic nomogram and risk group stratification system. J Urol. 2005;174:466–472. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000165572.38887.da. discussion 72; quiz 801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thompson RH, Leibovich BC, Lohse CM, et al. Dynamic outcome prediction in patients with clear cell renal cell carcinoma treated with radical nephrectomy: the D-SSIGN score. J Urol. 2007;177:477–480. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.09.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Janzen NK, Kim HL, Figlin RA, Belldegrun AS. Surveillance after radical or partial nephrectomy for localized renal cell carcinoma and management of recurrent disease. Urol Clin North Am. 2003;30:843–852. doi: 10.1016/s0094-0143(03)00056-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cindolo L, Patard JJ, Chiodini P, et al. Comparison of predictive accuracy of 4 prognostic models for nonmetastatic renal cell carcinoma after nephrectomy: a multicenter European study. Cancer. 2005;104:1362–1371. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cindolo L, de la Taille A, Messina G, et al. A preoperative clinical prognostic model for nonmetastatic renal cell carcinoma. BJU Int. 2003;92:901–905. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.2003.04505.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yaycioglu O, Roberts WW, Chan T, Epstein JI, Marshall FF, Kavoussi LR. Prognostic assessment of nonmetastatic renal cell carcinoma: a clinically based model. Urology. 2001;58:141–145. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(01)01207-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frank I, Blute ML, Cheville JC, Lohse CM, Weaver AL, Zincke H. An outcome prediction model for patients with clear cell renal cell carcinoma treated with radical nephrectomy based on tumor stage, size, grade and necrosis: the SSIGN score. J Urol. 2002;168:2395–2400. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)64153-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klatte T, Lam JS, Shuch B, Belldegrun AS, Pantuck AJ. Surveillance for renal cancer: Why and how? When and how often? Urol Oncol Semin Orig Invest. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2007.05.026. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leibovich BC, Blute ML, Cheville JC, et al. Prediction of progression after radical nephrectomy for patients with clear cell renal cell carcinoma: a stratification tool for prospective clinical trials. Cancer. 2003;97:1663–1671. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harrell FE, Jr, Lee KL, Mark DB. Multivariable prognostic models: issues in developing models, evaluating assumptions and adequacy, and measuring and reducing errors. Stat Med. 1996;15:361–387. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19960229)15:4<361::AID-SIM168>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shariat SF, Karakiewicz PI, Ashfaq R, et al. Multiple biomarkers improve prediction of bladder cancer recurrence and mortality in patients undergoing cystectomy. Cancer. 2008;112:315–325. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lam JS, Klatte T, Kim HL, et al. Prognostic factors and selection for clinical studies of patients with kidney cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2008;65:235–262. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bensalah K, Montorsi F, Shariat SF. Challenges of cancer biomarker profiling. Eur Urol. 2007;52:1601–1609. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim HL, Seligson D, Liu X, et al. Using tumor markers to predict the survival of patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Urol. 2005;173:1496–1501. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000154351.37249.f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zheng W, Yi X, Fadare O, et al. The oncofetal protein IMP3: a novel biomarker for endometrial serous carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:304–315. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181483ff8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pryor JG, Bourne PA, Yang Q, Spaulding BO, Scott GA, Xu H. IMP-3 is a novel progression marker in malignant melanoma. Mod Pathol. 2008;21:431–437. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3801016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li C, Rock KL, Woda BA, Jiang Z, Fraire AE, Dresser K. IMP3 is a novel biomarker for adenocarcinoma in situ of the uterine cervix: an immunohistochemical study in comparison with p16(INK4a) expression. Mod Pathol. 2007;20:242–247. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nielsen FC, Nielsen J, Christiansen J. A family of IGF-II mRNA binding proteins (IMP) involved in RNA trafficking. Scand J Clin Lab Invest Suppl. 2001;234:93–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liao B, Hu Y, Herrick DJ, Brewer G. The RNA-binding protein IMP-3 is a translational activator of insulin-like growth factor II leader-3 mRNA during proliferation of human K562 leukemia cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:18517–18524. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500270200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jiang Z, Chu PG, Woda BA, et al. Analysis of RNA-binding protein IMP3 to predict metastasis and prognosis of renalcell carcinoma: a retrospective study. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:556–564. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70732-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hoffmann NE, Sheinin Y, Lohse CM, et al. External validation of IMP3 expression as an independent prognostic marker for metastatic progression and death for patients with clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Cancer. 2008;112:1471–1479. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Klatte T, Seligson DB, Leppert JT, et al. The chemokine receptor CXCR3 is an independent prognostic factor in patients with localized clear cell renal cell carcinoma. J Urol. 2008;179:61–66. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.08.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Strano S, Dell’Orso S, Di Agostino S, Fontemaggi G, Sacchi A, Blandino G. Mutant p53: an oncogenic transcription factor. Oncogene. 2007;26:2212–2219. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Phuoc NB, Ehara H, Gotoh T, et al. Immunohistochemical analysis with multiple antibodies in search of prognostic markers for clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Urology. 2007;69:843–848. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.01.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hofmockel G, Wittmann A, Dammrich J, Bassukas ID. Expression of p53 and bcl-2 in primary locally confined renal cell carcinomas: no evidence for prognostic significance. Anticancer Res. 1996;16(6B):3807–3811. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Girgin C, Tarhan H, Hekimgil M, Sezer A, Gurel G. P53 mutations and other prognostic factors of renal cell carcinoma. Urol Int. 2001;66:78–83. doi: 10.1159/000056575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Uhlman DL, Nguyen PL, Manivel JC, et al. Association of immunohistochemical staining for p53 with metastatic progression and poor survival in patients with renal cell carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1994;86:1470–1475. doi: 10.1093/jnci/86.19.1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zigeuner R, Ratschek M, Rehak P, Schips L, Langner C. Value of p53 as a prognostic marker in histologic subtypes of renal cell carcinoma: a systematic analysis of primary and metastatic tumor tissue. Urology. 2004;63:651–655. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2003.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shvarts O, Seligson D, Lam J, et al. p53 is an independent predictor of tumor recurrence and progression after nephrectomy in patients with localized renal cell carcinoma. J Urol. 2005;173:725–728. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000152354.08057.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kempkensteffen C, Hinz S, Christoph F, et al. Expression parameters of the inhibitors of apoptosis cIAP1 and cIAP2 in renal cell carcinomas and their prognostic relevance. Int J Cancer. 2007;120:1081–1086. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Parker AS, Kosari F, Lohse CM, et al. High expression levels of survivin protein independently predict a poor outcome for patients who undergo surgery for clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Cancer. 2006;107:37–45. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Byun SS, Yeo WG, Lee SE, Lee E. Expression of survivin in renal cell carcinomas: association with pathologic features and clinical outcome. Urology. 2007;69:34–37. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2006.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Inman BA, Frigola X, Dong H, Kwon ED. Costimulation, coinhibition and cancer. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2007;7:15–30. doi: 10.2174/156800907780006878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Krambeck AE, Thompson RH, Dong H, et al. B7-H4 expression in renal cell carcinoma and tumor vasculature: associations with cancer progression and survival. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:10391–10396. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600937103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Roth TJ, Sheinin Y, Lohse CM, et al. B7-H3 ligand expression by prostate cancer: a novel marker of prognosis and potential target for therapy. Cancer Res. 2007;67:7893–7900. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Inman BA, Sebo TJ, Frigola X, et al. PD-L1 (B7-H1) expression by urothelial carcinoma of the bladder and BCG-induced granulomata: associations with localized stage progression. Cancer. 2007;109:1499–1505. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Thompson RH, Gillett MD, Cheville JC, et al. Costimulatory B7-H1 in renal cell carcinoma patients: Indicator of tumor aggressiveness and potential therapeutic target. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:17174–17179. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406351101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tringler B, Liu W, Corral L, et al. B7-H4 overexpression in ovarian tumors. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;100:44–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.08.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dong H, Chen L. B7-H1 pathway and its role in the evasion of tumor immunity. J Mol Med. 2003;81:281–287. doi: 10.1007/s00109-003-0430-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dong H, Zhu G, Tamada K, Chen L. B7-H1, a third member of the B7 family, co-stimulates T-cell proliferation and interleukin-10 secretion. Nat Med. 1999;5:1365–1369. doi: 10.1038/70932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dong H, Strome SE, Salomao DR, et al. Tumor-associated B7-H1 promotes T-cell apoptosis: a potential mechanism of immune evasion. Nat Med. 2002;8:793–800. doi: 10.1038/nm730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hirano F, Kaneko K, Tamura H, et al. Blockade of B7-H1 and PD-1 by monoclonal antibodies potentiates cancer therapeutic immunity. Cancer Res. 2005;65:1089–1096. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Thompson RH, Kuntz SM, Leibovich BC, et al. Tumor B7-H1 is associated with poor prognosis in renal cell carcinoma patients with long-term follow-up. Cancer Res. 2006;66:3381–3385. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Thompson RH, Dong H, Lohse CM, et al. PD-1 is expressed by tumor-infiltrating immune cells and is associated with poor outcome for patients with renal cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:1757–1761. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Krambeck AE, Dong H, Thompson RH, et al. Survivin and b7-h1 are collaborative predictors of survival and represent potential therapeutic targets for patients with renal cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:1749–1756. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dulaimi E, Ibanez de Caceres I, Uzzo RG, et al. Promoter hypermethylation profile of kidney cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10(12 Pt 1):3972–3979. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gonzalgo ML, Eisenberger CF, Lee SM, et al. Prognostic significance of preoperative molecular serum analysis in renal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:1878–1881. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cairns P. Gene methylation and early detection of genitourinary cancer: the road ahead. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:531–543. doi: 10.1038/nrc2170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bleeker SE, Moll HA, Steyerberg EW, et al. External validation is necessary in prediction research: a clinical example. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003;56:826–832. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(03)00207-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Justice AC, Covinsky KE, Berlin JA. Assessing the generalizability of prognostic information. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130:515–524. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-130-6-199903160-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kattan MW. Evaluating a new marker’s predictive contribution. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:822–824. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-03-0061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kim HL, Seligson D, Liu X, et al. Using protein expressions to predict survival in clear cell renal carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:5464–5471. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]