Abstract

Objectives

To determine whether older adults with high plasma carboxymethyl-lysine (CML), an advanced glycation end product, are at higher risk of all-cause and cardiovascular disease (CVD) mortality.

Design

Prospective cohort study.

Setting

Population-based sample of adults aged 65 and older residing in Tuscany, Italy.

Participants

One thousand thirteen adults participating in the Invecchiare in Chianti study.

Measurements

Anthropometric measures, plasma CML, fasting plasma total, high-density and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, triglycerides, glucose, creatinine. Clinical measures: medical assessment, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, coronary heart disease, heart failure, stroke, cancer. Vital status measures: death certificates and causes of death according to the International Classification of Diseases. Survival methods were used to examine the relationship between plasma CML and all-cause and CVD mortality, adjusting for potential confounders.

Results

During 6 years of follow-up, 227 (22.4%) adults died, of whom 105 died with CVD. Adults with plasma CML in the highest tertile had greater all-cause (hazard ratio (HR) = 1.84, 95% confidence interval) CI) = 1.30–2.60, P<.001) and CVD (HR = 2.11, 95% CI = 1.27–3.49, P = .003) mortality than those in the lower two tertiles after adjusting for potential confounders. In adults without diabetes mellitus, those with plasma CML in the highest tertile had greater all-cause (HR = 1.68, 95% CI = 1.15–2.44, P = .006) and CVD (HR = 1.74, 95% CI = 1.00–3.01, P = .05) mortality than those in the lower two tertiles after adjusting for potential confounders.

Conclusion

Older adults with high plasma CML are at higher risk of all-cause and CVD mortality.

Keywords: advanced glycation end products, aging, all-cause mortality, cardiovascular disease mortality

Advanced glycation end products (AGEs) are a heterogeneous group of bioactive molecules formed by the nonenzymatic glycation of proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids.1,2 AGEs have been implicated in the pathogenesis of diabetes mellitus,2 atherosclerosis,1,3 and renal disease.4 AGEs induce covalent cross-links with proteins such as collagen, enhance the synthesis of extracellular matrix components, increase oxidation of low-density lipoprotein, and upregulate the expression of adhesion molecules.1–4 AGEs accumulate within the intimal extracellular matrix of arteries and atherosclerotic lesions1,3 and increase glomerulosclerosis and interstitial fibrosis.4

AGEs have been the focus of growing interest because of substantial improvement in measurement technology and because experiments conducted in animal models have shown that reduced dietary intake of AGEs or pharmacological blockage of AGEs reduces the complications of atherosclerosis and diabetes mellitus.1,2 In humans, treatment with drugs that reduce systemic AGE concentrations, known as AGE breakers, and dietary restriction of AGE-containing foods have been shown to improve cardiovascular function.5–7 AGEs have primarily been studied in groups of patients with diabetes mellitus, end-stage renal disease, or both, and the relationship between AGEs and adverse clinical outcomes in older community-dwelling adults has not been well characterized. It was hypothesized that older adults with high levels of plasma carboxymethyl-lysine (CML), one of the dominant AGEs in the circulation and in tissues, have greater risk of mortality, especially cardiovascular disease mortality. To address this hypothesis, CML was characterized in a prospective population-based study of older men and women living in the community.

Materials And Methods

Participants and Setting

The study participants consisted of men and women aged 65 and older who participated in the Invecchiare in Chianti, “Aging in the Chianti Area” (InCHIANTI) study, conducted in two small towns in Tuscany, Italy. The rationale, design, and data collection have been described elsewhere, and the main outcome of this longitudinal study is mobility disability.8 Briefly, in August 1998, 1,270 people aged 65 and older were randomly selected from the population registry of Greve in Chianti (population 11,709) and Bagno a Ripoli (population 4,704); of 1,256 eligible subjects, 1,155 (90.1%) agreed to participate. Of the 1,155 participants, 1,043 (90.3%) participated in the blood drawing. During 6 years of follow-up, 227 participants died, 34 refused to participate in the follow-up examinations of the study, and 16 moved away from the area. Those who refused to participate in follow-up or moved away were known to be alive at the time of censoring of this analysis. Participants received an extensive description of the study and participated after providing written, informed consent. The study protocol complied with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Italian National Institute of Research and Care on Aging Ethical Committee and the institutional review board of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

Vital Status

Participants were evaluated again for a 3-year follow-up visit from 2001 to 2003 (n = 926) and 6-year follow-up visit from 2004 to 2006 (n = 844). At the end of the field data collection, mortality data of the original InCHIANTI cohort were collected using data from the Mortality General Registry maintained by the Tuscany Region and the death certificates that are deposited immediately after the death at the Registry office of the municipality of residence. CVD mortality was defined as death codes 390 to 459 from the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision.9

Clinical Evaluation

Demographic information and information on smoking and medication use were collected using standardized questionnaires. Smoking history was determined from self-report and dichotomized in the analysis as currently smoking versus ever smoked and never smoked. Daily alcohol intake, expressed in grams per day, was determined based on the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition food frequency questionnaire, which has been validated in the Italian population. Education was recorded as years of school. Pyridoxine (vitamin B6) and aspirin are two medications that can inhibit the formation of AGEs. Fewer than 3% of the participants reported taking any form of vitamins.

A trained geriatrician examined all participants, and diseases were ascertained according to standard, preestablished criteria and algorithms based upon those used in the Women's Health and Aging Study for diabetes mellitus, coronary heart disease, chronic heart failure, stroke, and cancer.10 Fasting plasma glucose was defined as normal, impaired, or diabetic based on a fasting plasma glucose of 99 mg/dL or less, 100 to 125 mg/dL, and greater than 125 mg/dL, respectively.11 The diagnosis of diabetes mellitus was based on the diagnostic algorithm,10 and of those who reported no diabetes mellitus, on a fasting plasma glucose of greater than 125 mg/dL.12 The diagnostic algorithm for the diagnosis of diabetes mellitus was based on the use of insulin, oral hypoglycemic agents, hemoglobin A1c, and a questionnaire administered to the primary care physician of the study participant.10

Systolic and diastolic blood pressures were calculated from the mean of three measures taken using a standard mercury sphygmomanometer during the physical examination. Weight was measured using a high-precision mechanical scale. Standing height was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight/height2 (kg/m2). BMI was categorized as underweight (<18.5 kg/m2), normal range (18.5–24.9 kg/m2), overweight (≥25.0-29.9 kg/m2), and obese (≥30.0 kg/m2) according to World Health Organization criteria.13 The Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) was administered at enrollment, and a MMSE score of less than 24 was considered consistent with cognitive impairment.14 Renal insufficiency was defined as estimated glomerular filtration rate of less than 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2 using the four-variable Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study equation.15

Laboratory Studies

Blood samples were collected in the morning after a 12-hour fast. Aliquots of serum and plasma were immediately obtained and stored at −80°C. The measure of plasma AGEs in this study was plasma CML. CML is a dominant circulating AGE, the best characterized of all the AGEs, and a dominant AGE in tissue proteins.16 CML was measured using a competitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (AGE-CML ELISA, Microcoat, Bernried, Germany, under license to Synvista Therapeutics, Montvale, NJ).17 This assay has been validated,18 is specific, and shows no cross-reactivity with other compounds.17 The minimum level of detectability of the assay is 5 ng/mL,17 which is below the concentration that has been found in human studies. The intra-assay and interassay coefficients of variation were both less than 5%.

Fasting blood glucose was determined according to an enzymatic colorimetric assay using a modified glucose oxidase–peroxidase method (Roche Diagnostics, GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) and a Roche-Hitachi 917 analyzer. Commercial enzymatic tests (Roche Diagnostics) were used for measuring serum total cholesterol, triglycerides, and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) concentrations. Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) was calculated using the Friedewald formula.19

Statistical Analysis

Variables are reported as medians (25th, 75th percentiles) or as percentages. Plasma CML was divided into tertiles, and the cutoffs between tertiles were 314 and 396 ng/mL. Age and BMI were used as categorical variables, because the relationships between age and mortality and between BMI and mortality were not linear. Characteristics of subjects according to their vital status were compared using Wilcoxon rank sum tests for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables. Cox proportional hazards models were used to examine the relationship between plasma CML and all-cause and CVD mortality over 6 years of follow-up. Variables that were significant in the univariate analyses were entered into the multivariate Cox proportional hazards models, except for CVD mortality, in which CVD were not included. Survival curves were compared using log-rank tests. The statistical program used was SAS (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC). The level of significance used in this study was P<.05.

Results

Plasma CML concentrations were measured at enrollment in 1,013 participants. During 6 years of follow-up, 227 (22.4%) of 1,013 participants died, of whom 105 died with CVD. The main causes of death were CVD (46.3%); cancer (26.1%), respiratory disease, including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and pneumonia (10.1%); and other (17.1%). The cause of death was unknown for one participant. The vital status of all 1,013 participants was known for the 6 years of follow-up.

All-Cause Mortality

Demographic and other characteristics of participants who died from all causes or survived are shown in Table 1. Median plasma CML concentrations were significantly higher in adults who died from all causes than those who survived. Participants who died from all causes were more likely to be older, male, less educated, and taking aspirin and to have a higher BMI; higher mean arterial pressure; abnormal fasting plasma glucose; lower total cholesterol, HDL-C, and LDL-C; an MMSE score less than 24; coronary heart disease, congestive heart failure; peripheral arterial disease; stroke; and renal insufficiency. There were no significant differences between participants who survived or died from all causes in smoking status, triglycerides, diabetes mellitus, or cancer.

Table 1. Demographic and Health Characteristics of Adults Aged 65 and Older in the Invecchiare in Chianti Study Who Survived or Died from All Causes or Cardiovascular Disease During Follow-Up.

| Characteristic | Lived n = 786 | Died from All Causes n = 227 | P-Value* | Died from Cardiovascular Disease n = 105 | P-Value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, n (%) | |||||

| 65–69 | 265 (33.7) | 17 (7.5) | <.001 | 5 (4.7) | <.001 |

| 70–74 | 243 (30.9) | 29 (12.8) | 8 (7.6) | ||

| 75–79 | 159 (20.2) | 50 (22.0) | 23 (21.9) | ||

| 80–84 | 68 (8.7) | 46 (20.3) | 21 (20.0) | ||

| 85–89 | 38 (4.8) | 46 (20.3) | 26 (24.8) | ||

| ≥90 | 13 (1.7) | 39 (17.1) | 22 (21.0) | ||

| Sex, n (%) | |||||

| Male | 324 (41.2) | 118 (52.0) | .004 | 54 (51.4) | .046 |

| Female | 462 (58.8) | 109 (48.0) | 51 (48.6) | ||

| Education, years, n, median (25th, 75th percentile) | 786, 5.0 (4.0, 6.0) | 227, 5.0 (3.0, 5.0) | <.001 | 105, 5.0 (3.0, 5.0) | <.001 |

| Alcohol intake, g/d, n, median (25th, 75th percentile) | 657, 13.7 (7.8, 27.4) | 190, 13.7 (5.9, 27.4) | .01 | 87, 13.7 (5.9, 27.4) | .02 |

| Smoking status, n (%) | |||||

| Current | 106 (13.5) | 32 (14.1) | .75 | 10 (9.5) | .51 |

| Former | 208 (26.5) | 65 (28.6) | 28 (26.7) | ||

| Never | 472 (60.0) | 130 (57.3) | 67 (63.8) | ||

| Aspirin use, n (%) | 240 (30.5) | 102 (44.9) | <.001 | 53 (50.5) | <.001 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2, n (%) | |||||

| <18.5 | 2 (0.3) | 0 (0 | .03 | 0 (0.0) | .10 |

| 18.5–24.9 | 205 (26.5) | 57 (26.6) | 30 (30.3) | ||

| 25.0–29.9 | 355 (45.8) | 78 (36.5) | 33 (33.3) | ||

| ≥30.0 | 212 (27.4) | 79 (36.9) | 36 (36.4) | ||

| Fasting plasma glucose, mg/dL, n (%) | |||||

| ≤99 | 584 (74.5) | 166 (73.8) | .03 | 73 (70.2) | .26 |

| 100–125 | 133 (17.0) | 38 (12.4) | 17 (16.5) | ||

| >125 | 67 (8.5) | 31 (13.8) | 14 (13.5) | ||

| Arterial pressure, mmHg, median (25th, 75th percentile) | 777, 104 (99, 113) | 216, 107 (100, 116) | .006 | 99, 110 (102, 117) | .003 |

| Plasma carboxymethyl-lysine, ng/mL, n, median (25th, 75th percentile) | 786, 343 (287, 414) | 227, 377 (303, 450) | <.001 | 105, 392 (315, 464) | <.001 |

| Serum triglycerides, mg/dL, n, median (25th, 75th percentile) | 786, 110 (84, 149) | 227, 111 (80, 154) | .86 | 105, 113 (81, 160) | .36 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL, n, median (25th, 75th percentile) | 786, 219 (196, 146) | 227, 202 (177, 227) | <.001 | 105, 209 (186, 243) | .02 |

| High-density lipoprotein cholesterol, mg/dL, n, median (25th, 75th percentile) | 786, 54 (46, 66) | 227, 50 (42, 60) | <.001 | 105, 50 (42, 62) | .002 |

| Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, mg/dL, n, median (25th, 75th percentile) | 786, 137 (118, 160) | 227, 123 (101, 147) | <.001 | 105, 132 (111, 154) | .03 |

| Mini-Mental State Examination score <24, n (%) | 181 (23.0) | 114 (50.2) | <.001 | 59 (56.2) | <.001 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 360 (45.8) | 121 (53.3) | .046 | 62 (59.1) | .01 |

| Coronary heart disease, n (%) | 31 (3.9) | 16 (7.1) | .05 | 10 (9.5) | .01 |

| Congestive heart failure, n (%) | 32 (2.8) | 22 (14.1) | <.001 | 19 (18.1) | <.001 |

| Peripheral artery disease, n (%) | 29 (3.7) | 33 (14.5) | <.001 | 20 (19.1) | <.001 |

| Stroke, n (%) | 25 (3.2) | 27 (11.9) | <.001 | 12 (11.4) | <.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 96 (12.2) | 39 (17.8) | .06 | 16 (15.2) | .38 |

| Cancer, n (%) | 47 (6.0) | 18 (7.9) | .29 | 6 (5.7) | .91 |

| Renal insufficiency, n (%) | 100 (12.8) | 54 (24.0) | <.001 | 33 (31.7) | <.001 |

Median (25th, 75th percentile) for continuous variables. Column percentages are shown for subcategories of age, smoking, and body mass index. Percentages are shown for specific conditions.

P-values for comparison of the group with all-cause mortality or cardiovascular disease mortality, respectively, with the group that lived, using Wilcoxon rank sum tests for continuous variables or chi-square tests for proportions.

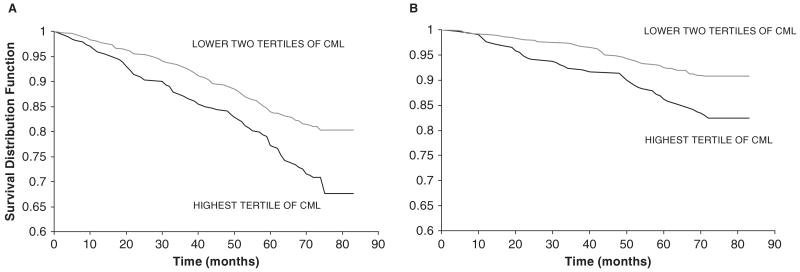

The proportions of participants who died from all causes in the lower, middle, and upper tertiles of plasma CML were 18.6%, 19.2%, and 29.3%, respectively (P = .001). Survival curves for all-cause mortality in participants in the highest tertile of plasma CML versus the lower two tertiles are shown in Figure 1A.

Figure 1.

Survival curves for (A) all-cause mortality of adults with plasma carboxymethyl-lysine (CML) concentrations in highest versus lower two tertiles (P<.001 by log-rank test) and (B) cardiovascular disease mortality of adults with plasma carboxymethyl-lysine concentrations in highest versus lower two tertiles (P<.001 by log-rank test). Survival distribution function refers to the percentage of surviving subjects in the study population.

CVD Mortality

Demographic and other characteristics of adults who died from CVD or survived are shown in Table 1. Median plasma CML concentrations were significantly higher in adults who died from CVD compared to adults who survived. Adults who died from CVD were more likely to be older, male, less educated, and taking aspirin and have higher mean arterial pressure; abnormal fasting plasma glucose; lower total cholesterol, HDL-C, and LDL-C; an MMSE score less than 24; hypertension; coronary heart disease; congestive heart failure; peripheral arterial disease; stroke; and renal insufficiency. There were no significant differences between adults who survived or died from all causes in smoking status, BMI, triglycerides, diabetes mellitus, or cancer.

The proportions of participants who died from CVD in the lower, middle, and upper tertiles of plasma CML were 8.3%, 9.9%, and 17.3%, respectively (P = .001). Survival curves for CVD mortality in adults with plasma CML in the highest tertile of plasma CML versus the lower two tertiles are shown in Figure 1B.

Plasma CML and All-Cause and CVD Mortality

Multivariate Cox proportional hazards models were used to examine the relationship between plasma CML and all-cause and CVD mortality (Table 2). Plasma CML was an independent predictor of all-cause mortality in multivariate Cox proportional hazards models that adjusted for age and sex; additionally for education, aspirin use, BMI, MMSE, alcohol intake, mean arterial pressure, and fasting plasma glucose; and additionally for total cholesterol, HDL-C, diabetes mellitus, renal insufficiency, and CVD (hypertension, coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, peripheral artery disease, and stroke) in all participants and after excluding participants with diabetes mellitus. No significant interactions were found between diabetes mellitus and plasma CML in multivariate Cox proportional hazards models for all-cause and CVD mortality.

Table 2. Multivariate Cox Proportional Hazards Models of Plasma Carboxymethyl-Lysine* and All-Cause and Cardiovascular Disease Mortality in Adults Aged 65 and Older in the Invecchiare in Chianti Study.

| Mortality | HR (95% Confidence Interval) P-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

| All cause | |||

| All participants | 1.57 (1.17–2.12) .003 | 1.63 (1.17–2.28) .004 | 1.84 (1.30–2.60) <.001 |

| Without diabetes mellitus | 1.48 (1.07–2.06) .02 | 1.45 (1.01–2.10) .046 | 1.68 (1.15–2.44) .006 |

| Cardiovascular disease | |||

| All participants | 2.06 (1.33–4.19) .001 | 2.16 (1.31–3.56) .002 | 2.11 (1.27–3.49) .003 |

| Without diabetes mellitus | 1.79 (1.11–2.90) .02 | 1.72 (0.99–2.99) .06 | 1.74 (1.00–3.01) .05 |

Covariates included in the multivariate models: Model 1 (age, sex), Model 2 (age, sex, education, body mass index, Mini-Mental State Examination score, alcohol intake, aspirin use, mean arterial pressure, fasting plasma glucose), Model 3 (age, sex, education, body mass index, Mini-Mental State Examination score, alcohol intake, aspirin use, mean arterial pressure, fasting plasma glucose, total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, diabetes mellitus, renal insufficiency, and additionally for all-cause mortality, hypertension, coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, peripheral arterial disease, and stroke).

Hazard ratios (HRs) shown for highest tertile of plasma carboxymethyl-lysine versus lower two tertiles.

Plasma CML was an independent predictor of CVD mortality in multivariate Cox proportional hazards models that adjusted for age and sex; additionally for education, aspirin use, BMI, MMSE, alcohol intake, mean arterial pressure, and fasting plasma glucose; and additionally for total cholesterol, HDL-C, diabetes, and renal insufficiency in all participants (Table 2). Plasma CML was an independent predictor of CVD mortality in participants without diabetes mellitus, adjusting for the same covariates above.

Plasma CML was not a significant predictor of non-CVD mortality in multivariate Cox proportional hazards models adjusted for age and sex (HR = 1.38, 95% = CI 0.91–2.08, P = .13); additionally for education, aspirin use, BMI, MMSE, alcohol intake, mean arterial pressure, and fasting plasma glucose (HR = 1.48, 95% CI = 0.90–2.28, P = .13); and additionally for renal insufficiency and CVD (HR = 1.48, 95% CI = 0.93–2.37, P = .10).

Discussion

This study demonstrates that older community-dwelling men and women with high plasma CML are at greater risk of dying, especially from CVD. To the authors' knowledge, this is the first study to show that plasma CML is an independent predictor of all-cause and CVD mortality in older community-dwelling adults. Plasma CML is one of the dominant AGEs in the circulation and in tissues,16 and CML is the only AGE that is a known ligand for receptors for AGE (RAGEs).20 Binding of RAGEs on cell membranes by CML adducts leads to greater generation of free radicals, activation of the nuclear factor κB pathway, and upregulation of inflammatory mediators such as tumor necrosis factor alpha, interleukin-6, and C-reactive protein.1

The strong association between high plasma CML and CVD mortality in this population-based study is consistent with the role that the AGE-RAGE pathway is considered to play in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis and CVD.1 CML accumulates in large blood vessels with age,21 and high serum CML concentrations were found to be associated with greater arterial stiffness, a strong risk factor for cardiovascular mortality, in adults in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging.22

A limitation of this study is that there may be residual confounding in the multivariate models due to measurement error and incomplete characterization of variables that were included in the models, given that only one set of measurements was used to determine baseline status. Some of the participants who provided the blood pressure readings used in this study were taking antihypertensive medication. In addition, the diagnosis of diabetes mellitus and the adjustment for fasting plasma glucose may be insufficient to truly characterize the risk for CVD attributable to diabetes mellitus.

In the present study, lower LDL-C was associated with higher all-cause and CVD mortality, which is consistent with previous reports in cohorts of older adults.23 Lower HDL-C was associated with higher all-cause and CVD mortality, which is consistent with a previous report.24

The dietary consumption of foods that are processed at high temperatures, such as by deep frying, roasting, and grilling, has been shown to lead to high levels of circulating CML.7 The Western diet is especially rich in AGEs.25 A limitation of the present study is that data on the dietary intake of AGEs was not available, because specialized dietary questionnaires are needed that address the cooking method used in the preparation of specific foods, although a previous study in older adults showed that serum CML concentrations are correlated with dietary intake of AGEs (correlation coefficient = 0.46, P<.001).26 Controlled dietary intervention studies in humans show that restriction of dietary AGE intake can substantially reduce serum CML concentrations.7 The findings from these dietary intervention studies are relevant to the present study, because circulating CML concentrations represent a modifiable risk factor. Circulating CML concentrations can be reduced using dietary interventions7,27 and pharmacological intervention with AGE breakers or AGE inhibitors.5,6,28 Restriction of dietary AGE intake reduces the expression of C-reactive protein and adhesion molecules and improves endothelial function.7,27 In animals, dietary restriction of AGEs increases longevity to a magnitude comparable with that of caloric restriction.29

Most studies of AGEs and their circulating receptors have been limited to patients with specific diseases, mainly diabetes mellitus, atherosclerosis, and end-stage renal disease. The strength of this study is that it was a large population-based sample of community-dwelling older men and women. These results are consistent with previous studies that showed higher mortality in patients undergoing hemodialysis30 and women with type 2 diabetes mellitus3 who had high circulating AGEs. The biological mechanisms by which high AGEs could increase the risk of dying cannot be specifically determined from this epidemiological study, although there is potential for high AGEs to cause widespread damage to multiple systems, because AGEs are known to alter the structural quality of blood vessels, bone, skeletal muscle, and other tissues through cross-linking with collagen2 and to accelerate inflammation, atherosclerosis, and renal damage through the AGE-RAGE pathway.1

In this study, plasma CML was independently predictive of CVD mortality and all-cause mortality. The magnitude of the HRs for mortality was greater for CVD mortality than all-cause mortality, suggesting that high plasma CML may be more specifically involved in CVD mortality. In addition, plasma CML was not significantly predictive of non-CVD mortality. Although it is believed that the hyperglycemia associated with diabetes mellitus increases the generation of endogenous AGEs,1 the relationship between plasma CML and all-cause and CVD mortality was found in patients without diabetes mellitus. The association between plasma CML and all-cause and CVD mortality was nonlinear, with a threshold at the highest tertile. These findings suggest that there may be a critical threshold for plasma CML above which the risk of mortality increases greatly. The search for this threshold is a priority for future research, because it is essential for clinical translation of these findings. In the present study, plasma CML was the only AGE measured, and there are many other AGEs such as pentosidine, carboxyethyl-lysine, and hydroimidazolone AGEs that could be measured and might provide additional insight into the relationship between AGEs and cardiovascular mortality.

The present study raises the possibility of using plasma CML as a prognostic biomarker for all-cause and CVD mortality in the general population. Further studies are needed to corroborate these findings in other population-based studies and to determine whether plasma CML is an independent predictor of specific adverse cardiovascular outcomes such as myocardial infarction, stroke, and heart failure.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institute on Aging (NIA) Grants R01 AG027012, R01 AG029148 and the Intramural Research Program, NIA, National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Sponsor's Role: The NIH had no role in the design, methods, subject recruitment, data collections, analysis, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The editor in chief has reviewed the conflict of interest checklist provided by the authors and has determined that the authors have no financial or any other kind of personal conflicts with this paper.

Author Contributions: Richard D. Semba and Luigi Ferrucci: origination of hypothesis and study design, laboratory analysis, data analysis and interpretation, preparation of manuscript. Stefania Bandinelli: acquisition of subjects and data, data analysis and interpretation, preparation of manuscript. Kai Sun: primary data analysis, preparation of manuscript. Jack M. Guralnik: data analysis and interpretation, preparation of manuscript.

References

- 1.Basta G, Schmidt AM, de Caterina R. Advanced glycation end products and vascular inflammation: Implications for accelerated atherosclerosis in diabetes. Cardiovasc Res. 2004;63:582–592. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vlassara H, Striker G. Glycotoxins in the diet promote diabetes and diabetic complications. Curr Diabetes Rep. 2007;7:235–241. doi: 10.1007/s11892-007-0037-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kilhovd BK, Juutilainen A, Lehto S, et al. Increased serum levels of advanced glycation endproducts predict total, cardiovascular and coronary mortality in women with type 2 diabetes: A population-based 18 year follow-up study. Diabetologia. 2007;50:1409–1417. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0687-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bohlender JM, Franke S, Stein G, et al. Advanced glycation end products and the kidney. Am J Renal Physiol. 2005;289:F645–F659. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00398.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kass DA, Shapiro EP, Kawaguchi M, et al. Improved arterial compliance by a novel advanced glycation end-product crosslink breaker. Circulation. 2001;104:1464–1470. doi: 10.1161/hc3801.097806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Little WC, Zile MR, Kitzman DW, et al. The effect of alagebrium chloride (ALT-711), a novel glucose cross-link breaker, in the treatment of elderly patients with diastolic heart failure. J Card Fail. 2005;11:191–195. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2004.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Negrean M, Stirban A, Stratmann B, et al. Effects of low- and high-advanced glycation endproduct meals on macro- and microvascular endothelial function and oxidative stress in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85:1236–1243. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/85.5.1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferrucci L, Bandinelli S, Benvenuti E, et al. Subsystems contributing to the decline in ability to walk: Bridging the gap between epidemiology and geriatric practice in the InCHIANTI study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:1618–1625. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb03873.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.International Classification of Diseases. Ninth revision, clinical modification. Washington, DC: U.S. Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guralnik JM, Fried LP, Simonsick EM, et al. The Women's Health and Aging Study: Health and Social Characteristics of Older Women with Disability. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Aging; 1995. NIH Publication No. 95-4009. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Genuth S, Alberti KG, Bennett P, et al. Follow-up report on the diagnosis of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:3160–3136. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.11.3160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Diabetes Association. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(suppl 1):S43–S48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.James PT, Leach R, Kalamara E, et al. The worldwide obesity epidemic. Obes Res. 2001;9(suppl 4):228S–233S. doi: 10.1038/oby.2001.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-Mental State”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levey AS, Bosch JP, Lewis JB, et al. A more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: A new prediction equation. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130:461–470. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-130-6-199903160-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reddy S, Bichler J, Wells-Knecht KJ, et al. N epsilon-(carboxymethyl)lysine is a dominant advanced glycation end product (AGE) antigen in tissue proteins. Biochemistry. 1995;34:10872–10878. doi: 10.1021/bi00034a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boehm BO, Schilling S, Rosinger S, et al. Elevated serum levels of Nε-carboxymethyl-lysine, an advanced glycation end product, are associated with proliferative diabetic retinopathy and macular oedema. Diabetologia. 2004;47:1376–1379. doi: 10.1007/s00125-004-1455-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang X, Frischmann M, Kientsch-Engel R, et al. Two immunochemical assays to measure advanced glycation end-products in serum from dialysis patients. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2005;43:503–511. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2005.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Friedewald WT, Levy RI, Frederickson DS. Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparation ultracentrifuge. Clin Chem. 1972;18:499–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kislinger T, Fu C, Huber B, et al. Nå-(carboxymethyl)lysine adducts of proteins are ligands for receptor for advanced glycation end products that activate cell signaling pathways and modulate gene expression. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:31740–31749. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.44.31740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schleicher ED, Wagner E, Nerlich AG. Increased accumulation of the glycoxidation product Nå-(carboxymethyl)lysine in human tissues in diabetes and aging. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:457–468. doi: 10.1172/JCI119180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Semba RD, Najjar SS, Sun K, et al. Serum carboxymethyl-lysine, an advanced glycation end product, is associated with increased aortic pulse wave velocity in adults. Am J Hypertens. 2009;22:74–79. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2008.320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tikhonoff V, Casiglia E, Mazza A, et al. Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and mortality in older people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:2159–2164. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weverling AWE, Jonker IJAM, van Exel E, et al. High-density vs low-density lipoprotein cholesterol as the risk factor for coronary artery disease and stroke in old age. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:1549–1554. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.13.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goldberg T, Cai W, Peppa M, et al. Advanced glycoxidation end products in commonly consumed foods. J Am Diet Assoc. 2004;104:1287–1291. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2004.05.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Uribarri J, Cai W, Peppa M, et al. Circulating glycotoxins and dietary advanced glyation endproducts: Two links to inflammatory response, oxidative stress, and aging. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;72:427–433. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.4.427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vlassara H, Cai W, Crandall J, et al. Inflammatory mediators are induced by dietary glycotoxins, a major risk factor for diabetic angiopathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:15596–15601. doi: 10.1073/pnas.242407999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smit AJ, Lutgers HL. The clinical relevance of advanced glycation endproducts (AGE) and recent developments in the pharmaceutics to reduce AGE accumulation. Curr Med Chem. 2004;11:2767–2784. doi: 10.2174/0929867043364342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cai W, He JC, Zhu L, et al. Reduced oxidant stress and extended lifespan in mice exposed to a low glycotoxin diet: Association with increased AGER1 expression. Am J Pathol. 2007;170:1893–1902. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.061281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wagner Z, Molnár M, Molnár GA, et al. Serum carboxymethyllysine predicts mortality in hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2006;47:294–300. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]