Abstract

Survival of T lymphocytes requires sustained Ca2+ influx-dependent gene expression. The molecular mechanism, which governs sustained Ca2+ influx in naive T lymphocytes, is unknown. Here we report an essential role for the β3 regulatory subunit of Cav channels in the maintenance of naive CD8+ T cells. β3 deficiency resulted in a profound survival defect of CD8+ T cells. This defect correlated with depletion of the pore-forming subunit Cav1.4 and attenuation of T cell receptor-mediated global Ca2+ entry in the absence of β3 in CD8+ T cells. Cav1.4 and β3 associated with T cell signaling machinery and Cav1.4 localized in lipid rafts. Our data demonstrate a mechanism by which Ca2+ entry is controlled by a Cav1.4–β3 channel complex in T cells.

Keywords: Calcium, Cacnb3, T lymphocyte, Cav channel, Apoptosis

Calcium (Ca2+) signaling plays a pivotal role in adaptive immune responses. Sustained Ca2+ influx across the plasma membrane of T cell leads to the activation of NFAT transcription factors. NFATs regulate survival, activation, proliferation and effector functions of T lymphocytes1-4. Despite the established role of Ca2+ in T lymphocyte development and functions, the mechanism of sustained Ca2+ entry in naive T lymphocytes remains elusive to date.

A well-characterized mode of Ca2+ entry in T cells is the CRAC (Calcium Release Activated Ca2+) pathway, in which, two key players, STIM1 and ORAI1 (also known as CRACM1), have been described5-7. STIM1 functions as an intracellular calcium store sensor, which activates the CRAC pore subunit ORAI1 upon release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores after T cell receptor (TCR) crosslinking8. The majority of studies implicated ORAI as being crucial for T cell development and functions9. Yet, ORAI deletion had no significant impact on Ca2+ influx in naive T cells and proliferation of naive T cells upon stimulation10,11. These intriguing observations suggest complexity of the Ca2+ response in primary T cells and indicate a potential role of more than one type of plasma membrane calcium channels.

Cav channels conduct Ca2+ in a variety of cell types most notably characterized in excitable cells. Cav channel complexes consist of the pore-forming α1 subunit, in addition to the α2, δ, γ and β subunits. β subunits are cytoplasmic proteins that strongly regulate Cav channels through direct interaction with the pore-forming α1 subunits and are required for the assembly of the channel complex12, correct plasma membrane targeting13-15 and stimulation of the channel activity16. Cav channels are now known to be present in many cells not traditionally considered excitable, such as cells of the immune system17-20. We previously showed that CD4+ T cells, a major arm of the adaptive immune system, express Cav1 family members and that functional β3 and β4 regulatory subunits are necessary for normal TCR-triggered Ca2+ responses, NFAT nuclear translocation and cytokine production19. Recently we have also shown that deficiency in AHNAK1, a scaffold protein, resulted in reduced interleukin 2 (IL-2) production, reduced proliferation of CD4+ T cells21 and defective cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) responses22, which were likely due to the reduced Cav1.1 [http://www.signaling-gateway.org/molecule/query?afcsid=A000443] expression and therefore attenuated Ca2+ signaling. These studies provide convincing evidence for a biological significance of Cav channels in T cell biology.

In the present study, we investigated the role of Cav channels in Ca2+ entry in CD8+ T cells. Although CRAC channels have been implicated to play a role in the entry of extracellular Ca2+ in effector CD8+ T cell clones23, nothing is known about the mechanism of Ca2+ entry in TCR-stimulated naive CD8+ T cells. Herein, we report an interesting expression pattern of Cav1 family proteins in CD8+ T cells and document genetic evidence for a novel role of β3 regulatory protein in the survival of CD8+ T cells in vitro and in vivo.

Results

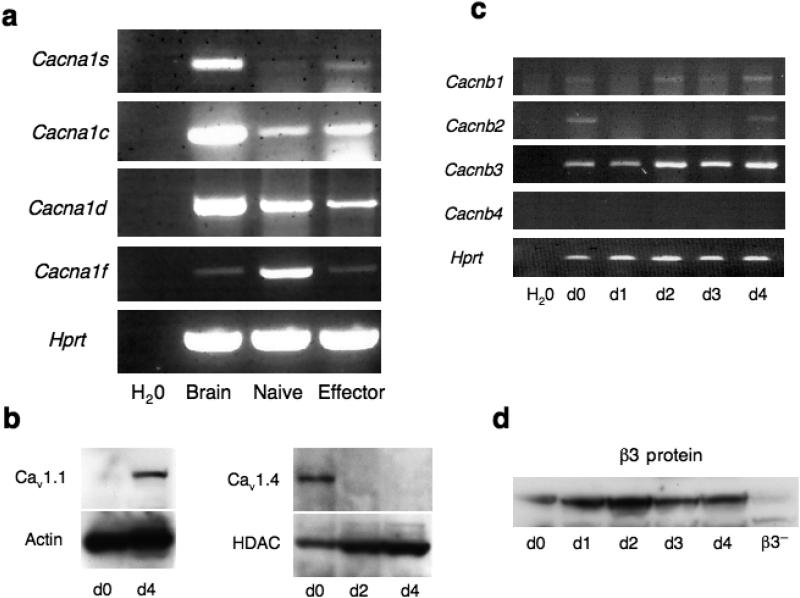

Expression of Cav channel components in CD8+ T cells

As a first step to analyzing the role of Cav channels in CD8+ T cell functions, we examined the expression pattern of pore-forming α1 subunits of Cav1 family members (Cav1.1-Cav1.4) [http://www.signaling-gateway.org/molecule/query?afcsid=A000440; http://www.signaling-gateway.org/molecule/query?afcsid=A000441; http://www.signaling-gateway.org/molecule/query?afcsid=A000442] and their regulatory β subunits (β1-β4) in both naive and activated CD8+ T cells. We designed intron-spanning PCR primer pairs for each gene and obtained the expected size of PCR products. Interestingly, expression of Cav1 family members in naive and effector CD8+ T cells was temporally regulated (Fig. 1a). Cacna1s mRNA was expressed only in effector but not in naive CD8+ T cells (Fig. 1a). In contrast to Cacna1s mRNA abundance, Cacna1f mRNA was highly expressed in naive CD8+ T cells and substantially downregulated in effector CD8+ T cells (Fig. 1a). We did not observe such temporal regulation of Cacna1c and Cacna1d mRNA expression (Fig. 1a). We further confirmed the reciprocal expression of Cav1.1 (encoded by Cacna1s) and Cav1.4 (encoded by Cacna1f) channel protein in wild-type CD8+ T cells. In agreement with the mRNA data (Fig. 1a), while expression of Cav1.4 was detected only in naive but not activated CD8+ T cells (Fig. 1b), expression of Cav1.1 was detected only in activated but not in naive CD8+ T cells (Fig. 1b). Cav1.1 protein expression appeared only on day 4 upon primary stimulation (Supplementary Fig. 1). However, in contrast to the mRNA data, we could not detect Cav1.2 protein (encoded by Cacna1c) in naive CD8+ T cells22.

Figure 1. Expression analysis of pore forming α subunits and regulatory β subunits of Cav channels.

(a) Naive CD8+ T cells (CD62Lhigh and CD44low) were left unstimulated (naive) or were stimulated with plate-bound anti-CD3 plus anti-CD28 Abs for 4 days (effector). Total RNA was extracted from each time point and subjected to RT-PCR analysis of the expression of mRNA encoding pore forming α1 subunits of Cav1 family: Cav1.1 (Cacna1s), Cav1.2 (Cacna1c), Cav1.3 (Cacna1d) and Cav1.4 (Cacna1f) (b) Purified naïve or in vitro generated effector CD8+ T cells were lyzed and expression of Cav1.1 and Cav1.4 was examined by immunoblot analysis using anti-Cav1.1 and anti-Cav1.4 antibodies. (c) Total RNA from cells, generated as described in panel (a) and stimulated as indicated, was subjected to RT-PCR analysis of the expression of mRNA encoding regulatory β subunits of Cav channels: β1 (Cacnb1), β2 (Cacnb2), β3 (Cacnb3), and β4 (Cacnb4), (d) Cells, as prepared in panel (c), were lyzed and β3 expression level was detected by immunoblot analysis. Results of all panels are representative of two independent experiments.

We also examined the expression pattern of β regulatory subunits in CD8+ T cells. Among all β subunits, only β3 subunit mRNA and protein, encoded by Cacnb3, was constitutively and predominantly expressed in naive as well as in effector CD8+ T cells (Fig. 1c,d). Other β subunits such as β1 (encoded by Cacnb1) and β2 (encoded by Cacnb2) were either expressed in minimal amounts or undetected such as β4 (encoded by Cacnb4) (Fig. 1c). The comparatively high expression of β3 protein in naive and activated CD8+ T cells led us to hypothesize a potential role for β3 in the CD8+ T cell biology. To investigate the function(s) of β3 in CD8+ T cell survival and proliferation, we analyzed Cacnb3-deficient mice24.

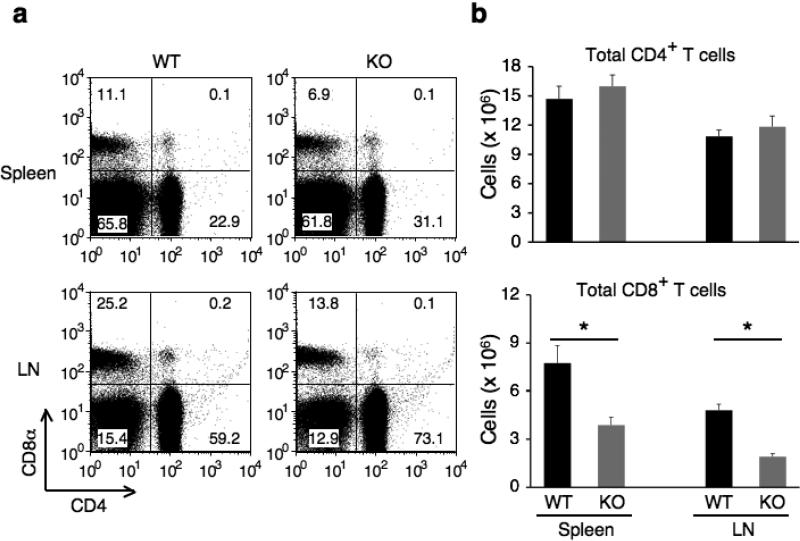

T cell compartment in Cacnb3-deficient mice

We showed previously that T lymphocytes developed normally in the thymus in the absence of the β3 subunit19. To identify the physiological roles of β3 in T cells, we analyzed peripheral lymphocytes isolated from Cacnb3+/+ and Cacnb3–/– mice. Cacnb3–/– mice exhibited normal number of CD4+ T cell populations in the periphery (Fig. 2a,b), however, we observed a reduction in the total number of CD8+ T cells in Cacnb3–/– mice (Fig. 2b). Although a reduction of the fraction of CD8+ T cells was not observed consistently (Fig. 2a), the total number of CD8+ T cells was substantially reduced (Fig. 2b). These observations indicated a perturbation in CD8+ T cell homeostasis in Cacnb3–/– mice.

Figure 2. Characterization of T cells in Cacnb3–/– mice.

(a) Splenocytes and LNs from 5 weeks old wild type and Cacnb3–/– male mice were analyzed by flow cytometry for CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. (b) Absolute numbers of CD4+ or CD8+ T cells in splenocytes and LNs. (c) Flow cytometry analysis of surface markers CD44 and CD62L expressed on CD8+ T cells of spleen and LNs. (d, e) Absolute numbers of naïve CD8+ or naïve CD4+ T cells in splenocytes and LNs. Results in panel a, b, c, d, and e are representative of two independent experiments (n=5 per experiment). Error bars in panel b, d and e show s.d. of 5 mice. *P < 0.05 (t-test).

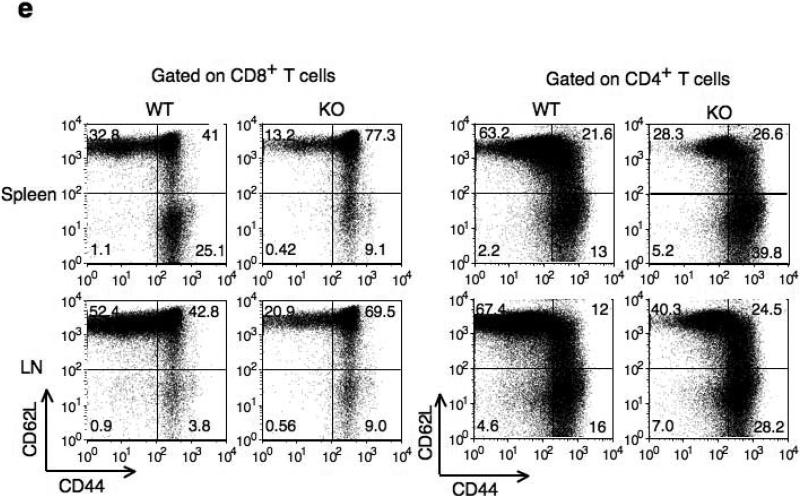

To examine the CD8+ T cell population in more detail, we determined the activation status of CD8+ T cells. Compared to control CD8+ T cells, a severe reduction in both the proportion and absolute numbers of splenic naive (CD44loCD62Lhi) CD8+ T cells was observed consistently in Cacnb3–/– mice (Fig. 2c,d). Similarly, reduction in absolute numbers, but not frequencies, of naive CD8+ T cells was also observed in peripheral LNs of Cacnb3–/– mice (Fig. 2c,d). Furthermore, a higher percentage of Cacnb3–/– CD8+ T cells exhibited a memory like phenotype (CD44hi) in spleen (Fig. 2c). On the other hand, the frequency and absolute number of naive CD4+ T were normal in LNs and spleen of Cacnb3–/– mice (Fig. 2e and Supplementary Fig. 2). These data indicate a specific defect in the CD8+ T cells compartment in vivo in Cacnb3–/– mice.

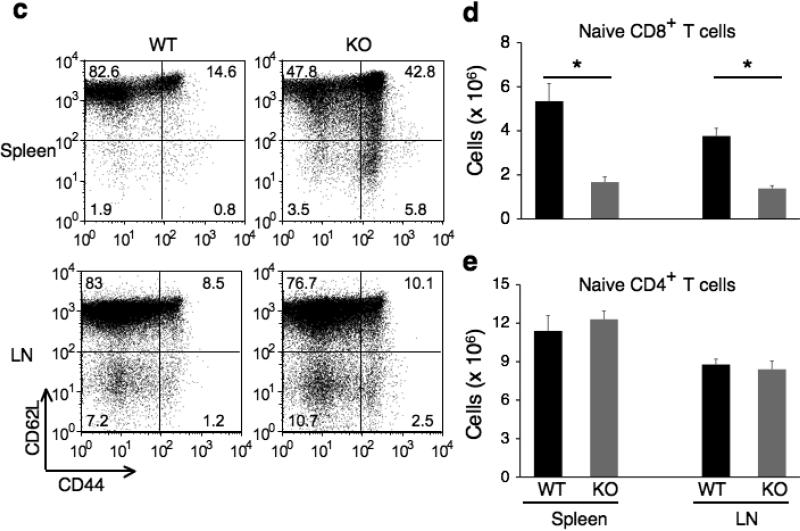

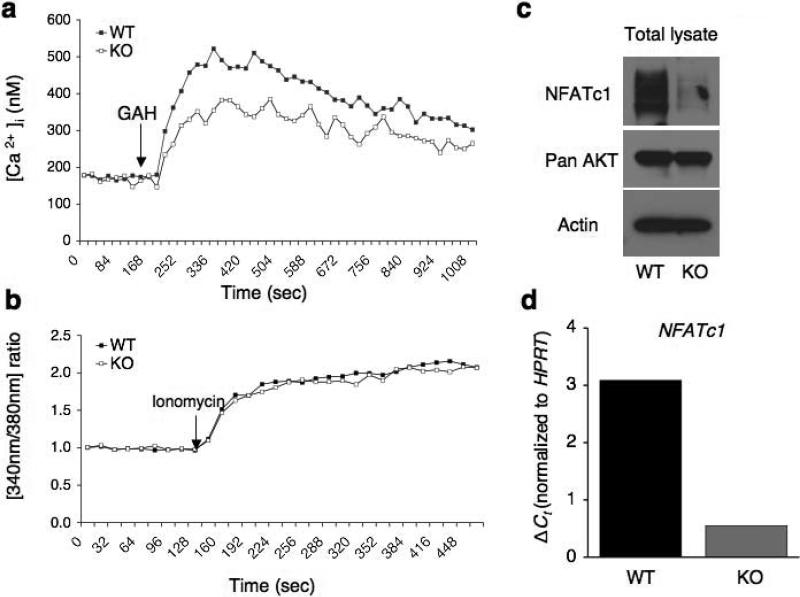

Ca2+ influx in Cacnb3–/– CD8+ T cells

The mechanism of Ca2+ entry in TCR stimulated naive CD8+ T cells is not known. Since β3 deficiency resulted in reduced Ca2+ entry into naive CD4+ T cells after TCR crosslinking19, we examined if this is also the case in naive Cacnb3–/– CD8+ T cells. The Ca2+ response to TCR cross-linking was markedly reduced in Cacnb3–/– CD8+ T cells compared to wild-type cells (Fig. 3a). Both the initial peak and the plateau were lower in the mutant cells as compared to wild-type cells. The ionomycin-induced calcium response in wild-type and Cacnb3–/– CD8+ T cells was similar, suggesting that the reduced Ca2+ entry was not due to CRAC deficiency (Fig. 3b).

Figure 3. Calcium/NFAT pathway is impaired in Cacnb3–/– CD8+ T cells.

(a, b) The calcium response of one million sorted naïve CD8+ T cells (CD62Lhigh and CD44low) from Cacnb3–/– mice and WT mice was evaluated by using 2C11 anti-CD3 Ab and goat anti-hamster (GAH) in a cross-linking system and upon ionomycin treatment. (c) Western blot assay was performed on whole cell lysates prepared from naive CD8+ T cells (CD62Lhigh and CD44low) of Cacnb3–/– and control mice. Actin was used as an internal control. (d) Total RNAs prepared from nonstimulated WT and Cacnb3–/– naïve CD8+ T cells were analyzed for the levels of NFATc1 transcripts using commercially available probe (ABI) by real-time PCR. Results are representative of three (a and b), and two (c and d) independent experiments.

To investigate if reduced Ca2+ entry in Cacnb3–/– CD8+ T cells affected NFAT translocation and thereby activation, we examined NFATc1 abundance in cytosolic and nuclear extracts prepared from wild-type and Cacnb3–/– naive CD8+ T cells stimulated by anti-TCR plus anti-CD28 for 12 h. As expected from the decrease in global Ca2+ concentrations in Cacnb3–/– CD8+ T cells (Fig. 3a), the nuclear translocation of three isoforms of NFATc1 was reduced in stimulated CD8+ T cells in the absence of β3 subunit (Supplementary Fig. 3). Although nuclear translocation of all three isoforms was reduced, NFATc1 activation (as measured by the faster electrophoretic migration by dephosphorylated NFATs) appeared normal in the absence of β3 (Supplementary Fig. 3). The cytoplasmic concentration of NFATc1 was also remarkably reduced in the stimulated Cacnb3–/– CD8+ T cells (Supplementary Fig. 3). Therefore, we examined the basal expression of NFATc1 in unstimulated wild-type or Cacnb3–/– naive CD8+ T cells. Whole cell lysates were made from equal number of live cells and assessed for the expression of NFATc1 and another survival factor, the kinase Akt. Less NFATc1 protein, but not Akt, was observed in Cacnb3–/– naive CD8+ T cells (Fig. 3c). To investigate if reduction in NFATc1 protein was due to altered gene expression, we measured the NFATc1 transcript abundance in wild-type or Cacnb3–/– naïve CD8+ T cells by real-time assay. Nfatc1 expression was much less in Cacnb3–/– naive CD8+ T cells as compared to wild-type cells (Fig. 3d). These data clearly demonstrate that β3-dependent Ca2+ entry is required for the steady-state transcriptional regulation of NFATc1 in naive CD8+ T cells.

Physiological significance of β3 in CD8+ T cells

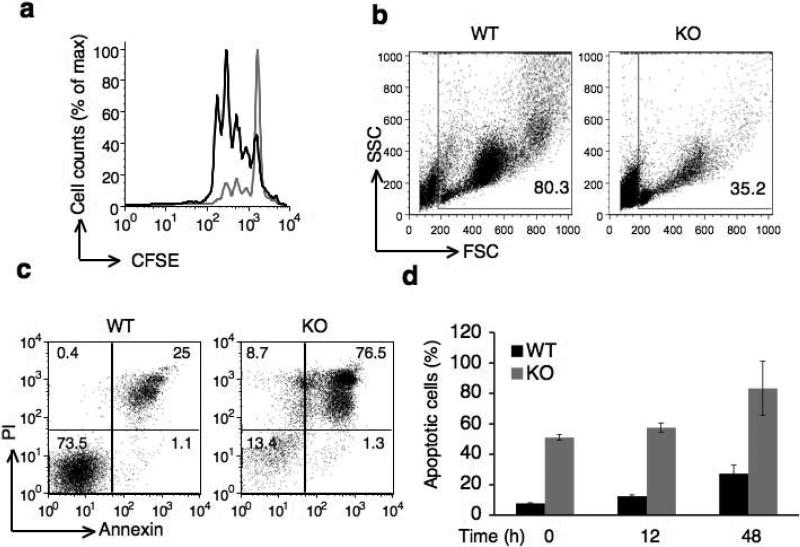

Given that the Ca2+–NFAT pathway is required for the T cell activation and proliferation, we determined whether reduced Ca2+ entry in Cacnb3–/– CD8+ T cells affected antigen induced proliferation in vitro. Sorted naive CD8+ T cells were labeled with CFSE (carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester) dye and cell cycle progression was assessed after 3 days of TCR plus CD28 stimulation in the presence of exogenous murine IL-2. Whereas wild-type cells underwent 4–5 cell divisions, a high number of Cacnb3–/– CD8+ T cells failed to divide (Fig. 4a). The forward and side scatter pattern of Cacnb3–/– cells showed remarkably a higher percentage of dead cells on day 3 (Fig. 4b) and cell recovery was also extremely low on d3 (data not shown). These observations led us to determine if Cacnb3–/– CD8+ T cells underwent activation-induced cell death (AICD).

Figure 4. Survival of naïve CD8+ T cells requires β3 subunit.

(a) Proliferation of Cacnb3–/– and WT naïve CD8+ T cells stimulated by plate-bound antibodies to CD3 and soluble CD28 assessed after 72 hours by CFSE. (b) Forward and side scatter pattern of Cacnb3–/– and WT naïve CD8+ T cells after 72 hrs as stimulated in panel (a). (c) Cacnb3–/– and WT naïve CD8+ T cells were stimulated as in panel (a), stained with annexin V and PI after 48 hrs of stimulation and analyzed. (d) Cacnb3–/– and WT naïve CD8+ T cells were stimulated for indicated time, stained with annexin V and PI and analyzed in flow cytometry. (e and f) 21 day old mice were thymectomized and analysis of T cell populations in spleen and LN was done six to eight weeks post thymectomy. Frequency and numbers of all T cell populations were shown from each individual mouse (n=5) of one experiment (P value - unpaired, two-tailed Student's t-test). Results in a, b, c, and d are representative of three independent experiments (error bars (d), s.d.) and results in (e) and (f) are representative of four independent experiments with 2-5 mice per group in each experiment.

To quantify AICD, we activated naive CD8+ T cells from WT and Cacnb3–/– mice by TCR plus CD28 stimulation for 48 h followed by staining with annexin and propidium iodide (PI). Annexin-PI staining revealed a very high incidence of AICD in Cacnb3–/– CD8+ T cells compared to wild-type controls (Fig. 4c). Cacnb3–/– CD8+ T cells in spleen, but not in thymus, exhibited enhanced annexin V positive (Supplementary Fig. 4). We also assessed the kinetics of AICD in Cacnb3–/– CD8+ T cells. Purified naive wild-type and Cacnb3–/– CD8+ T cells were stained for annexin-PI at 0 h (non-stimulated), or at 12 h or 48 h post-activation. Approximately 40% of naïve non-stimulated Cacnb3–/– CD8+ T cells were already annexin-PI positive compared to 4-5% wild-type cells (Fig. 4d), suggesting that these cells were undergoing spontaneous apoptosis in vivo which was further increased upon TCR plus CD28 stimulation ex vivo.

To study the longevity of naive T cells in vivo, wild-type and Cacnb3–/– mice were thymectomized just after weaning at 3 weeks of age and the survival of the naive T cell pool was determined. Because thymectomy prevents the addition of new naive T cells to the existing pool, a fixed population of naive T cells was created in vivo. We examined spleen and LNs for naïve and memory T cells after 6-8 weeks of thymectomy. We observed a substantial reduction in the proportion and absolute numbers of naive CD8+ T cells in all peripheral lymphoid organs (Fig. 4e,f). On the other hand, although the proportion of central memory CD8+ T cells (as characterized by CD62LhiCD44hi) was significantly higher in Cacnb3–/– mice (Fig. 4e), the total number of memory CD8+ T cell in spleen was reduced but not LNs (Fig. 4f). The frequency and total numbers of naive CD4+ T cells were also reduced in spleen and LNs of Cacnb3–/– mice compared to wild-type mice (Fig. 4e,f). These data clearly establish a critical requirement of β3 in the in vivo survival of T cell in general and naive CD8+ T cells in particular.

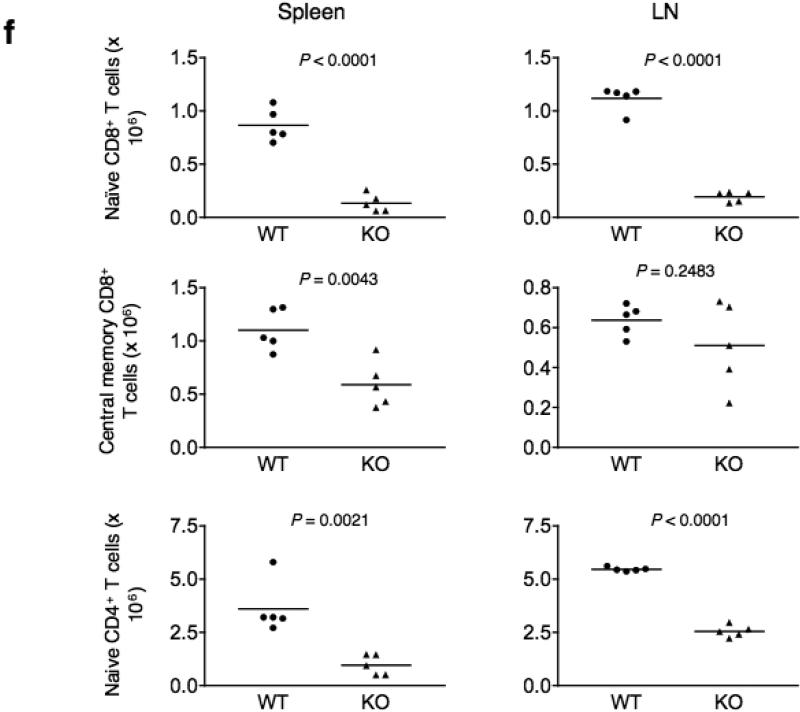

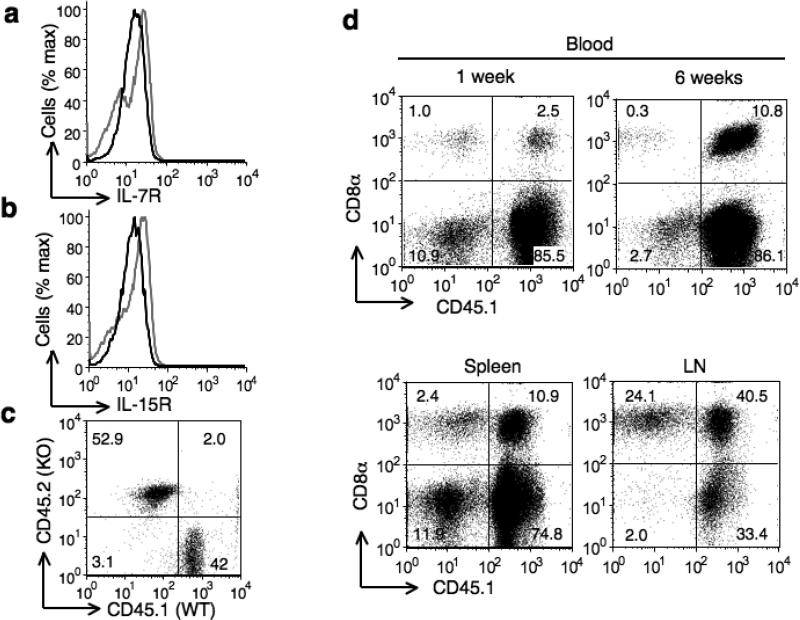

Defective homeostasis of Cacnb3–/– CD8+ T cells

Since we found that β3 supports the survival of naive CD8+ T cells, we next investigated the potential reason for the survival defect in the absence of β3. The survival of mature naive T cells in the peripheral environment requires continuous TCR contact with self-MHC ligands and γc family of cytokines such as IL-7 and IL-15 (ref. 25). It has been proposed that T cells constantly compete for the limited amounts of IL-7 available in the periphery and that this competition is influenced by downregulation of expression of the IL-7 receptor (IL-7R) after IL-7 signaling26. Therefore we investigated expression of IL-7R and IL-15R in wild-type or Cacnb3–/– naïve CD8+ T cells. No significant change in expression of either receptor was observed in the absence of β3 in naïve CD8+ T cells (Fig. 5a,b). These data suggested that β3 deficiency in naïve CD8+ T cells did not impair the survival signals generated by γc family of cytokines.

Figure 5. Homeostatic maintenance of naïve CD8+ T cells is critically dependent on β3 subunit.

(a and b) IL-7R and IL-15R protein expression were analyzed in non-stimulated Cacnb3–/– and WT naïve CD8+ T cells (CD62Lhigh and CD44low). (c) Frequency of mixture of sorted naïve CD8+ T cells (CD62Lhigh and CD44low) from WT (CD45.1.1+) mice and Cacnb3–/– (CD45.2.2+) mice before transfer. (d) Mixed cells as prepared in panel (c) was transferred into Rag1–/–CD45.1.1+ recipient mice, followed by analysis at 1 and 6 weeks after transfer in peripheral blood (upper) or at 6 weeks in spleen and LN (lower). Numbers inside boxed areas indicate percent recovered CD8+ T cells of Cacnb3–/–CD45.2.2+ cells (left top) or Cacnb3+/+CD45.1.1+ cells (right top). Results are representative of three (a & b) and two (c & d) independent experiments.

To investigate whether defective survival of Cacnb3–/– CD8+ T cells is cell intrinsic or due to other extrinsic factors, we performed homeostasis experiments. Homeostatic proliferation of naive T cells is most easily studied by transferring small numbers of these cells into T cell-deficient mice such as Rag1–/–, SCID or nude mice. For these experiments, we backcrossed Cacnb3–/– mice for eight generations onto congenic C57BL/6 mice and used age- and sex-matched wild-type (CD45.1.1) and Cacnb3–/– (CD45.2.2) mice for experiments. We transferred a mixture of Cacnb3–/– and wild-type sorted naïve CD8+ cells into CD45.1.1 Rag1–/– mice as recipients (Fig. 5c). One week after transfer, whereas wild-type donor cells survived and expanded their populations extensively to constitute 2-3% of the host cells, we detected ≤ 1% Cacnb3–/–-deficient donor cells (Fig. 5d), even though we transferred more Cacnb3–/– cells compared to wild-type at the beginning (Fig. 5c). After 4–6 weeks of transfer, we recovered 10–40% of wild-type cells but substantially reduced Cacnb3–/– cells (Fig. 5d). The disappearance of Cacnb3–/– cells is thus due to their defective long-term survival.

Fas-mediated apoptosis of Cacnb3–/– CD8+ T cells

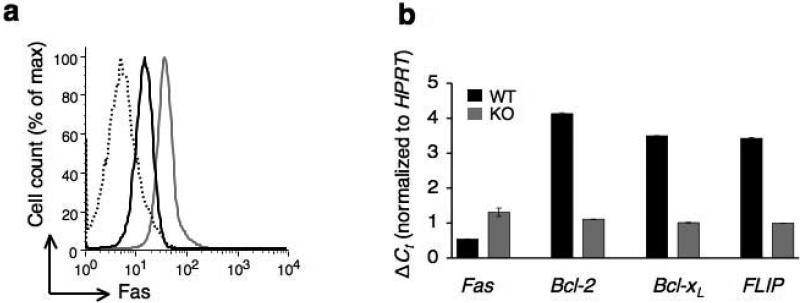

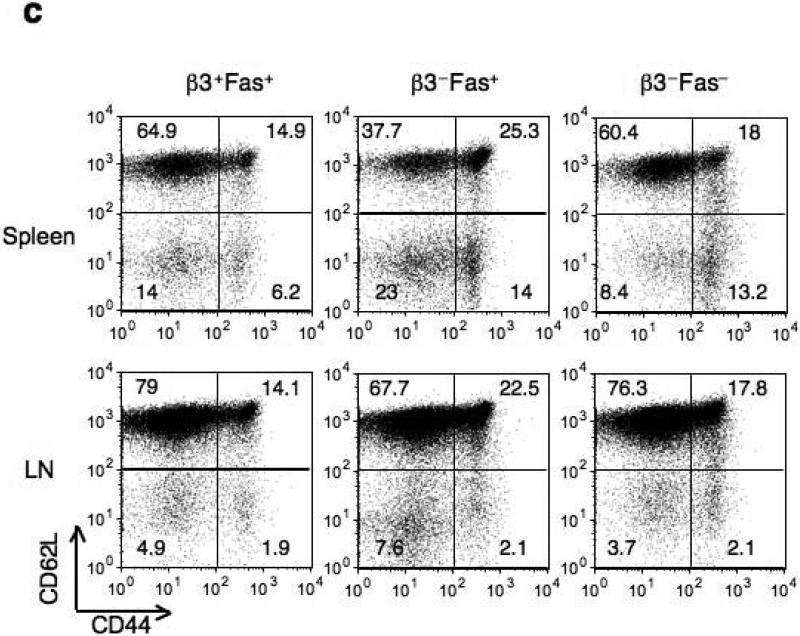

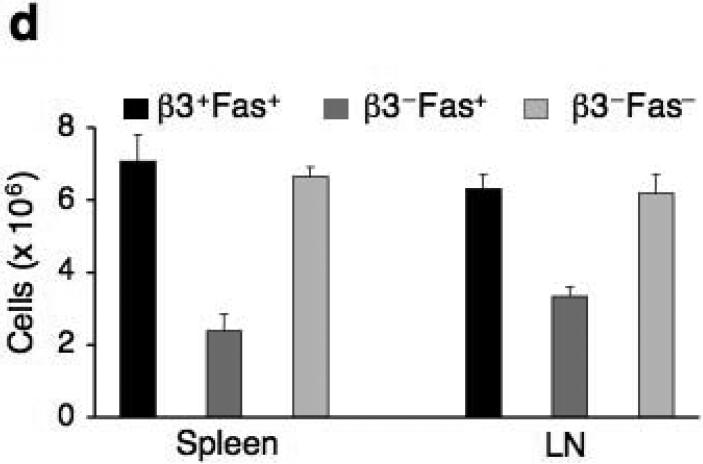

Numerous studies have established the anti-apoptotic function of NFAT factors in immune system27-29. We therefore examined the pro- and anti-apoptotic gene expression in wild-type or Cacnb3–/– CD8+ T cells. First, we determined Fas expression in Cacnb3–/– naïve CD8+ T cells. Notably, Cacnb3–/– naïve CD8+ T cells expressed a very high level of Fas protein compared to that of wild-type (Fig. 6a) and not CD43 or FasL (Supplementary Fig. 5). Similarly, Fas transcript abundance was increased by 2-3 fold in Cacnb3–/– naïve CD8+ T cells compared to the wild-type control (Fig. 6b), consistent with the earlier report describing the requirement of Ca2+ in repressing Fas gene expression30. Finally, we determined if β3 deficiency affected the expression of anti-apoptotic genes and found expression of Bcl-2, Bcl-xL and FLIP mRNAs were down-regulated in Cacnb3–/– naïve CD8+ T cells (Fig. 6b).

Figure 6. Upregulation of Fas and downregulation of anti-apoptotic gene expression in Cacnb3–/– CD8+ T cells.

(a) Fas protein expression in non-stimulated Cacnb3–/– and WT naïve CD8+ T cells (CD62Lhigh and CD44low). (b) Analysis of Fas, Bcl-2, Bcl-xl and FLIP mRNA expression levels in nonstimulated Cacnb3–/– and WT naïve CD8+ T cells using real-time quantitative PCR. (c) Flow cytometry analysis of surface markers CD44 and CD62L expressed on CD8+ T cells of spleen and LNs. (d) Absolute numbers of naïve CD8+ T cells in splenocytes and LNs. Results are representative of three (a) and two (b) independent experiments (error bars (b), s.d. of triplicate samples). Histograms in panel (c) represent 3 individual mice and panel (d) show s.d. of 3 mice.

To rescue this loss of CD8+ T cells in vivo, we crossed Cacnb3–/– mice with Fas–/– mice. The proportion and numbers of Cacnb3–/– Fas–/– naïve CD8+ T cells was restored to that of wild-type mice (Fig. 6c,d). These data collectively suggest that spontaneous apoptosis occurring in Cacnb3–/– naïve CD8+ T cells was Fas-mediated.

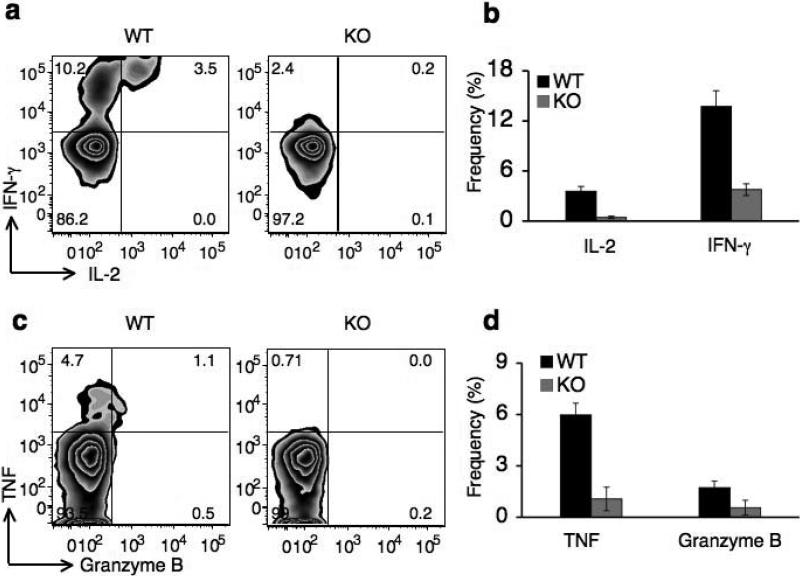

Defective CD8+ T cell responses in Cacnb3–/– mice

Since the β3 subunit was abundantly expressed in activated CD8+ T cells (Fig. 1c,d), we analyzed its role in effector CD8+ T cell functions. Because Cacnb3–/– CD8+ T cells were unable to proliferate in vitro (Fig. 4a), we used a model system previously described to test CD8+ T cell effector function in vivo31. For this purpose, wild-type dendritic cells (DCs) primed with SIINFEKL peptide were transferred to both wild-type and Cacnb3–/– mice. We examined the ability of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells to produce several effector molecules including interferon-γ (IFN-γ), IL-2, tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and granzyme B on day 7 after immunization. Cacnb3–/– CD8+ T cells showed a significant deficiency in IFN-γ and IL-2 production (Fig. 7a,b). A similar deficiency was also observed for TNF and granzyme B production by antigen specific Cacnb3–/– CD8+ T cells (Fig. 7c,d). These data also suggest that the deficiency in effector molecules production by Cacnb3–/– CD8+ T cells was not due to defective antigen presentation, since we primed Cacnb3–/– CD8+ T cells with wild-type DCs.

Figure 7. Defective CD8+ T cell dependent in vivo effector response in Cacnb3–/– mice.

Wild-type DCs primed with H-2Kb binding-SIINFEKL peptide (OVA) were transferred into WT and Cacnb3–/– mice. Seven days later, splenocytes were purified and restimulated with SIINFEKL peptide for 6 hrs followed by analysis of IFNγ and IL-2 (a) or Granzyme B and TNF (c) expression in CD8+ T cells by intracellular staining. Each histogram in panels (a) and (c) for both staining represents 5 wild-type and Cacnb3–/– mice. Results shown in panels (b) & (d) are mean ± SD for 5 mice per group. Unstimulated cells and CD4+ T cells serve as negative control in setting gates. Another independent experiment yielded similar results.

Cav1.4 is depleted in Cacnb3–/– naïve CD8+ T cells

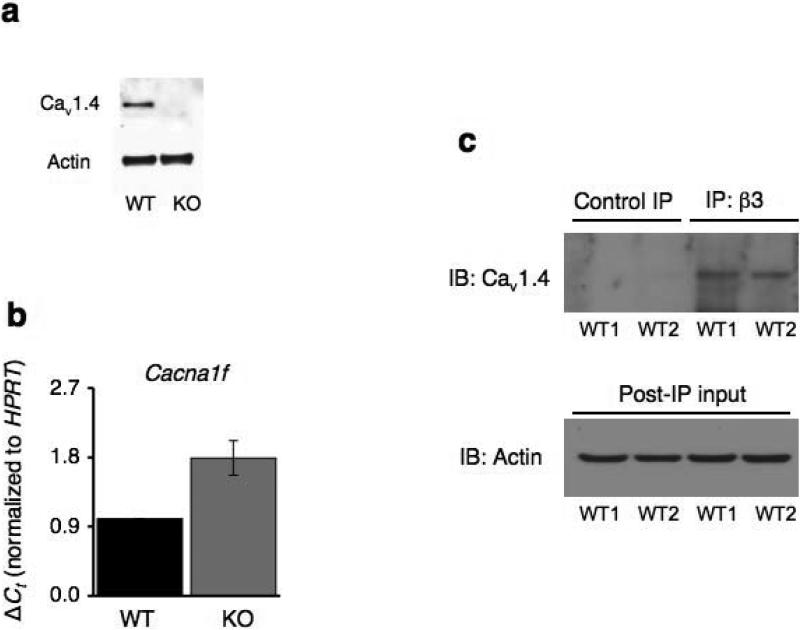

β subunits regulate expression of Cavα1 subunits by masking their endoplasmic reticulum retention signals13. Since Cav1.4 was found to be expressed in naïve CD8+ T cells (Fig. 1a&b), we analyzed its expression in naïve CD8+ T cells purified from wild-type and Cacnb3–/– mice. A complete loss of Cav1.4 protein (Fig. 8a), but not mRNA (Fig. 8b), was detected in the Cacnb3–/– CD8+ cells. Instead, an increase in Cacna1f mRNA abundance was observed in the absence of β3 (Fig. 8b), suggesting a compensatory increase in Cacna1f mRNA expression. Based on these data, we concluded that β3 was not needed for the upregulation of channel transcription but rather involved in post-transcriptional events.

Figure 8. Loss of Cav1.4 pore forming subunits in Cacnb3–/– naïve CD8+ T cells.

(a) Nonstimulated WT and Cacnb3–/– naïve CD8+ T cells (CD62Lhigh and CD44low) were lyzed and Cav1.4 expression was detected by immunoblot analysis using polyclonal antibody provided by JEM. (b) RNAs prepared from nonstimulated WT and Cacnb3–/– naïve CD8+ T cells were analyzed for the abundance of Cacna1f transcripts by real-time PCR. (c) Whole cell lysates were prepared from unstimulated CD8+ T cells purified from pLNs of approximately 20-25 WT mice per group. 1 mg protein extracts were taken for co-immunoprecipitation experiment and incubated with anti-β3 antibody (clone 828) overnight at 4°C followed by immunoblotting and detection by anti-Cav1.4 antibody. Results are representative of three (a & b) and two (c) independent experiments.

The β-subunit belongs to the membrane-associated guanylate kinase class of scaffolding proteins (MAGUK) and contains a conserved Src homology 3 (SH3) domain and a conserved guanylate kinase (GK) domain32 (Supplementary Fig. 6). Interaction between alpha interaction domain (AID) in the α1 subunit and GK domain is necessary for β subunit-stimulated Cav channel surface expression33. Depletion of Cav1.4 in Cacnb3–/– CD8+ T cells (Fig. 8a) indicated a potential interaction between Cav1.4 and β3. To examine this idea, we co-immunoprecipitated β3-interacting proteins from wild-type CD8+ T lymphocytes and immunoblotted with antibody against Cav1.4. We detected Cav1.4 only in those samples immunoprecipitated by antibody against β3 and not in samples immunoprecipitated by control isotype antibody (Fig. 8c). Collectively, these data demonstrate that Cav1.4 and β3 form a stable Cav1.4 calcium channel complex in these T cells and suggests that the absence of β3 destabilizes and leads to degradation of this channel complex without affecting Cacna1f gene expression.

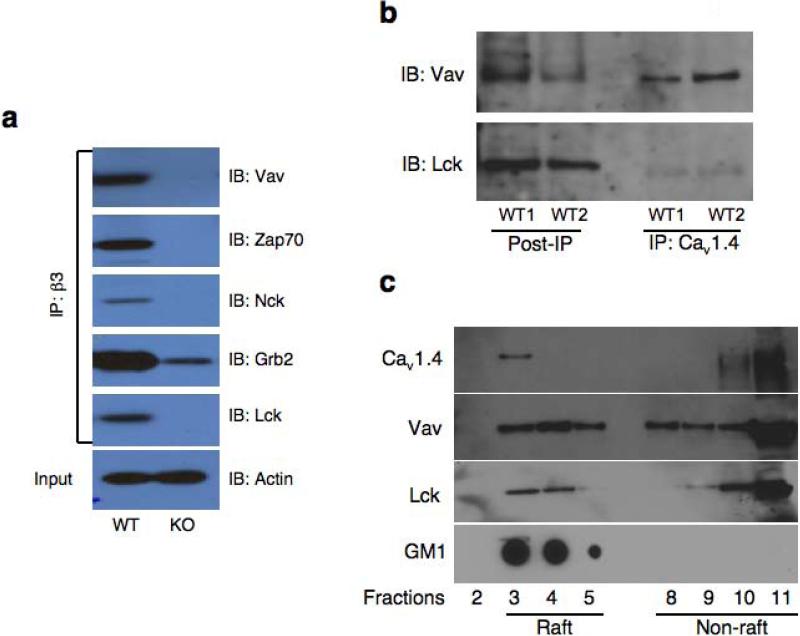

β3 and Cav1.4 interact with T cell signaling proteins

Many downstream TCR signaling proteins, such as Lck, Vav, Zap-70, Grb2, and Nck contain SH2 and SH3 motifs that are known to facilitate the assembly of multi-protein signaling complex. Similarly, SH3 and GK domains in β subunits highlight a multiplicity of potential protein partners. To investigate whether β3 interacts with such proteins and participate in multi-protein T cell signaling complex, β3-interacting proteins were immunoprecipitated from wild-type or Cacnb3–/– primary CD8+ T lymphocytes using antibody against β3 and immunoblotted with antibodies against known key T cell signaling kinases and adapters. Interestingly, β3 antibody recovered Lck, Vav, Zap70, Nck, and Grb2 only in wild-type but not in Cacnb3–/– CD8+ T cells (Fig. 9a).

Figure 9. Association of Cav1.4 and β3 with T cell signaling components and localization of Cav1.4 in lipid rafts.

(a) Whole cell lysates were prepared from unstimulated CD8+ T cells purified from pLNs of approximately 20-25 WT mice per group. 1 mg protein extracts were taken for co-immunoprecipitation experiment and incubated with anti-β3 antibody (clone 828) overnight at 4°C followed by immunoblotting and detection by respective antibodies. (b) 1 mg protein extracts as prepared in panel (a) were taken for co-immunoprecipitation experiment and incubated with monoclonal anti-Cav1.4 antibody (Sigma) overnight at 4°C followed by immunoblotting and detection by anti-Lck and anti-Vav antibodies. (c) Total CD8+ T cells, purified from spleen and LNs of approximately 8 - 10 wild-type mice, were subjected to lipid raft isolation protocol. 1 to 11 fractions were collected. Fractions # 3, 4, 5 were raft fractions as per GM1 staining and fractions # 8, 9, 10, 11 were non-raft fractions. Usually fraction # 1, 2, 6 and 7 were very low in protein concentrations and therefore not loaded. These fractions were analyzed for the presence of different proteins by immunoblotting. GM1 staining was done separately on these fractions. Results in all panels are representative of two independent experiments.

We performed coimmunoprecipitation experiments to determine whether Cav1.4 channel is directly present in the TCR signaling complex. Cav1.4-interacting proteins were immunoprecipitated from wild-type CD8+ T lymphocytes and immunoblotted with antibodies against known key T cell signaling kinases and adaptors. Lck and Vav were co-immunoprecipitated by a monoclonal antibody against Cav1.4 (Fig. 9b). Overall, these data indicate a possible synergy of crosstalk between Cav channels and the T cell signaling machinery in a cellular context where interaction of these molecules is required for rapid Ca2+ influx once TCR is stimulated either in an antigen-dependent or -independent manner.

Cav1.4 localizes in lipid rafts of CD8+ T cells

Recently, Cav1.4 channel protein has been shown to interact with filamin proteins in immune cells34. Filamin is expressed in T lymphocytes and participates in T cell activation35. Interestingly, CD28 associated with filamin which is required for CD28-induced lipid raft recruitment into the immunological synapse36. These lipid rafts concentrate glycophosphatidylinositol-linked proteins, glycosphingolipids, as well as several molecules involved in signal transduction such as Lck, LAT, Ras, and G proteins and thereby lipid rafts provide a signaling platform37.

Our finding that Cav1.4 was in a complex with raft resident proteins, Lck and Vav (Fig. 9b) coupled with the reported interaction of Cav1.4 with filamins34 led us to speculate that Cav1.4 might be localized in lipid rafts to facilitate the TCR-mediated sustained calcium influx. To investigate this possibility, lipid rafts were purified from CD8+ T cells of wild-type mice and were analyzed by immunoblot for the presence of Cav1.4 and known raft resident signaling proteins such as Lck and Vav. Interestingly, Cav1.4 along with Lck and Vav were found in lipid raft fractions (Fig. 9c). As a control for the purity of lipid raft fractions, we analyzed the presence of ganglioside GM1, which is a commonly used raft marker. GM1 staining was only positive in detergent-resistant lipid raft fractions (3–5) and not in detergent-soluble cytosolic fractions (8–11) suggesting the clear separation of raft from non-raft fractions (Fig. 9c). These data identify Cav1.4 as a potential calcium channel in lipid microdomains of T cells.

Discussion

In this study, we have examined the biological significance of Cav1 channels in CD8+ T cells. Surprisingly, we found Cav1.4, but not Cav1.1, is highly expressed in naïve CD8+ T cells whereas Cav1.1, not Cav1.4 (or Cav1.2), is highly expressed in activated CD8+ T cells. We also observed a significant and robust expression of only β3 subunit at all developmental stages of peripheral CD8+ T cells. Cacnb3–/– mice have a highly reduced pool of naïve CD8+ T cells due to spontaneous apoptosis in vivo. In the absence of thymic output, survival of both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells was affected in vivo. Increased expression of Fas caused spontaneous apoptosis since Fas deficiency rescued loss of CD8+ T cells in Cacnb3–/– mice. This observation supports an elegant prior study which showed that CD8+ T cells die via a Fas-dependent pathway in the absence of a survival signal provided by engagement of host MHC-self peptide complexes38.

Compared to wild-type, Cacnb3–/– CD8+ T cells have attenuated Ca2+ entry upon TCR crosslinking. Although our data lack a measurement of basal Ca2+ levels in unstimulated cells due to technical limitations, we found a severe reduction in basal NFATc1 levels in naive Cacnb3–/– CD8+ T cells (in the absence of any TCR stimulation). This suggested a reduction in NFAT-dependent NFATc1 gene expression since the NFATc1 gene has functional binding sites for NFATs and an autoregulatory role of NFAT factors has been described in murine T cells39.

We found that β3 associates with Cav1.4 subunit and β3 deficiency completely depletes the cellular levels of pore forming Cav1.4 subunit, suggesting that β3 is required for a functional and stable Cav1.4 channel in T cells probably by protecting Cav1.4 from degradation. Interestingly, we found that β3 and Cav1.4 are associated with a T cell signaling complex in primary CD8+ T cells, which was not dependent on TCR-stimulation suggesting that a preformed complex of these proteins exists in naïve T cells. Furthermore, we identified a fraction of Cav1.4 as a lipid raft resident calcium channel protein. Combining the previously reported interaction of Cav1.4 with filamins in spleen cells34 with our finding of its association with Lck and Vav highlight a Cav channel dependent molecular architecture of signaling complex in specialized microdomains of T cells. These observations further gain significance in light of a widely accepted model that the specificity, reliability and accurate execution of many of these processes depend on tightly regulated spatiotemporal Ca2+ signals restricted to precise microdomains that contain Ca2+-permeable channels and their modulators40,41.

It has been suggested that Cav1.4 is a unique channel which supports only minute amounts of Ca2+ entry42. Low intensity of calcium influx has been shown to regulate survival of naïve T cells in the absence of antigen43. Based on these observations we believe that a Cav1.4-β3 complex in naïve CD8+ T cells is involved in antigen-independent, MHC-triggered Ca2+ response which generates tonic signaling for the survival of these cells. Tonic signaling might be required to express a threshold level of important transcription factors like NFATs which, in turn, repress the expression of pro-apoptotic genes such as Fas and also maintain a threshold expression levels of anti-apoptotic genes such as Bcl-2/xL and cFLIP. Our observation that the Cav1.4/β3 complex regulates Ca2+ influx required for the survival of naïve CD8+ T lymphocytes has fundamental importance in understanding the regulatory mechanisms of calcium signaling in primary T cells. Since Cav channels are clinically well-established targets in many pathological conditions, this study identifies a β3/Cav1.4 dependent pathway in CD8+ T cells, which may be used to design therapeutic agents to inhibit aggressive CD8+ T cells in autoimmune and lymphoproliferative diseases.

Methods

Mice

Cacnb3–/– mice were as previously described24. Mice within experiments were age (5–6 weeks in all experiments) and sex-matched. Bulk of experiments was done either on 129svj or the mixed background (2 generations backcrossed with C57BL/6) mice. Mice were kept in accordance with institutional animal care and used according to committee-approved protocols at the Yale University School of Medicine animal facility.

T cell purification, culture and flow cytometry

Lymphocytes were isolated from 5–6- week-old mice. Peripheral CD8+ T cells were purified with CD8-coupled beads (Miltenyi Biotec) and were sorted for naive T cell population (gated on CD8, CD62Lhi and CD44lo) on a VantageSE station (Becton Dickinson). Unless otherwise stated, all experiments were done on sorted naive CD8+ T cells. T cells were cultured at 37°C with 5% CO2 in Bruff's medium supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) FBS and 1% (vol/vol) penicillin-streptomycin and 25 U/ml of IL-2.

RNA isolation and semiquantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA from cells was isolated with Trizol reagent and subjected to reverse transcriptase with Superscript II (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. PCR was done with sense and antisense primers: Cacnb1 (NM_031173), 5'-GAAAGGGCGGTTCAAAAGGTC-3′ (sense) and 5'-TTGGGCTCAAAGGTGATGGC-3′ (antisense); Cacnb2 (NM_023116.3), 5'-CGGACCAATGTCAGATACAGCG-3′ (sense) and 5'-TGGAACTGGGCACTATGTCACC-3′ (antisense); Cacnb3 (NM_001044741), 5'-AACCTGTGGCATTTGCTGTGAG-3′ (sense) and 5'-CCTGCTTTTGCTTCTGCTTGG-3′ (antisense). RT-PCR primers for Hprt (hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase), Cacnb4 and Cavα1 subunits were described previously19. Real-time PCR analysis of Cacna1f, NFATc1, Fas, Bcl-2, Bcl-xL was performed by using commercially available primers and probe from Applied Biosystems. Cycling conditions were 2 min at 94°C followed by 35 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 56°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min. Hprt was included as an internal control for all samples and quantified by ΔCt (change in cycle threshold) method.

Flow cytometry

Cells were stained with fluorochrome-conjugated Abs in 1% FBS in Bruffs medium and subsequently fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde. The following Abs were used: CD8α (53-6.7), TCRβ (H57-597), CD44 (clone IM7), CD62L (clone MEL-14), Fas (Jo2), and CD4 (RM4-5) (all Abs from BD PharMingen). Cells were analyzed with a FACS Calibur (BD Biosciences) and data were analyzed by FlowJo v. 6.1 (TreeStar, Inc.). Staining with annexin V and propidium iodide (BD Pharmingen) or CFSE (Molecular Probes) were done according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Antibodies

Following commercial antibodies were used: mouse monoclonal Ab to NFATc1 (Affinity Bioreagents), anti-actin goat polyclonal Ab, anti-Cav1.1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-AKT (Cell signaling # 4685), pan-Cadherin (abcam # ab6528), anti-Grb2 (BD transduction #610111), anti-Nck (BD Transduction # 610099), anti-Vav (Upstate # 05-219), anti-Lck (Cell Signaling # 610097) and anti-Zap70 (Sigma # Z0627). The Ab to β3 (Ab 828) was provided by V.F.44 and polyclonal anti-Cav1.4 was provided by J.M.45 and monoclonal anti-Cav1.4 was from Sigma.

Protein extracts and immunoblot analysis

For immunoblot assays, equal number (3–5 × 106) of WT and KO cells were directly lyzed in the LDS buffer (Invitrogen) and sonicated for 30 sec. Cell lysates were electrophoresed on 3–8% Bis-Tris (neutral pH) or 4-12% MOPS (neutral pH) NuPAGE gradient gel (Invitrogen), transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Millipore), and immunoblotted with appropriate Abs.

Analysis of intracellular calcium concentration

Concentrations of intracellular calcium were measured using the ratiometric calcium-binding dye Fura-2/AM as previously described19.

Thymectomy

3-weeks-old (just after weaning) mice were anesthetized with a mixture of 100 mg/ml ketamine (Fort Dodge Laboratories) and 20 mg/ml xylazine (Abbott Laboratories) by IP (0.1 ml per 10 g body weigh just before surgery. Thymectomy was performed by aspiration of the thymus through an incision in the skin and muscle over the thymus in the suprasternal notch. The skin and body wall were sutured using soluble sutures and Vetbond. Successful extraction of the thymus was verified upon sacrifice of the animals at the time of experiment.

In vivo priming of CD8+ T cells

BMDCs were generated in vitro in GM-CSF containing complete Bruffs medium for 7 days according to the method published previously31. On day 7, cells were washed and incubated overnight with H-2Kb binding SIINFEKL peptide (OVA257-264) (10 μg/ml) and LPS (200 ng/ml). Next day, cells were washed three times with sterile PBS and 1 × 106 cells were injected i.p. into WT and Cacnb3–/– mice. After 7 days spleens were harvested and splenocytes were in vitro stimulated with SIINFEKL peptide (10 μg/ml) for 6 h in the presence of Golgi stop (BD Biosciences, Cat # 554715). Cells were stained with CD8+ then fixed and permeabilized for intracellular staining of IFN-γ, IL-2, Granzyme B and TNF. Stained cells were analyzed by FACS calibur.

Coimmunoprecipitation

CD8+ T cells were resuspended in 500–1000 μl of cell lysis buffer (Cell signaling #9803) or RIPA buffer (Cell signaling #9806) containing protease- and phosphatase inhibitors (PMSF, leupeptin, NEM and cocktail tablets, Roche Diagnostics). Resulting extracts were pre-cleared by rocking with 1 ml of a 50% slurry of equilibrated Protein A/G beads (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for 2 h at 4°C and removal of the precipitate. The resulting supernatant was then subjected to immunopreciptation for overnight at 4°C followed by immunoblot assays.

Lipid raft isolation and characterization

Lipid rafts were isolated from CD8+ T cells as previously described46. Cells were lyzed in 1 ml of 25 mM HEPES (pH 6.5), 1 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 μg/ml leupeptin (all from Sigma) and Roche protease inhibitor cocktail. The homogenate was overlaid with 5 - 40% step gradient of sucrose solution and subjected to ultracentrifugation at 200,000g for 20 h at 4°C. The floating opaque band corresponding to the detergent-resistant membrane fraction was found at the interface between the 30% and 5% sucrose gradients. Fractions were characterized for the raft purity by blotting 1 μl of each fraction onto Duralon-UV membranes (Stratagene), followed by blocking and immunoblotting with cholera toxin B subunit from Vibrio cholerae - peroxidase (Sigma # C3741).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Prism™. P values were calculated with Student's t-test. P values of less than 0.05 were considered significant. Unless otherwise stated, numbers shown are mean±standard deviation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank E. Eynon for suggestions, F. Manzo for preparing the manuscript, C. Rathinam for critical reading of the manuscript, D. Butkus for performing thymectomy, T. Taylor for excellent Fluorescence Activated Cell Sorting and Fran Balamuth for advise on lipid raft isolation. M.K.J. is supported by an Arthritis Foundation postdoctoral fellowship. A.B. was supported by the Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale and by the Arthritis National Research Foundation. V.F. and M.F. are supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and Homburger Forschungsförderungsprogramm. J.E.M. is supported by an operating grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. M.K.J. and A.B. were Associates and R.A.F. is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

References

- 1.Hogan PG, Chen L, Nardone J, Rao A. Transcriptional regulation by calcium, calcineurin, and NFAT. Genes Dev. 2003;17:2205–2232. doi: 10.1101/gad.1102703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gallo EM, Cante-Barrett K, Crabtree GR. Lymphocyte calcium signaling from membrane to nucleus. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:25–32. doi: 10.1038/ni1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oukka M, et al. The transcription factor NFAT4 is involved in the generation and survival of T cells. Immunity. 1998;9:295–304. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80612-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Serfling E, et al. The role of NF-AT transcription factors in T cell activation and differentiation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1498:1–18. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(00)00082-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vig M, et al. CRACM1 multimers form the ion-selective pore of the CRAC channel. Curr Biol. 2006;16:2073–2079. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.08.085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prakriya M, et al. Orai1 is an essential pore subunit of the CRAC channel. Nature. 2006;443:230–233. doi: 10.1038/nature05122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang SL, et al. Genome-wide RNAi screen of Ca(2+) influx identifies genes that regulate Ca(2+) release-activated Ca(2+) channel activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:9357–9362. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603161103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feske S. Calcium signalling in lymphocyte activation and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:690–702. doi: 10.1038/nri2152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lewis RS. The molecular choreography of a store-operated calcium channel. Nature. 2007;446:284–287. doi: 10.1038/nature05637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vig M, et al. Defective mast cell effector functions in mice lacking the CRACM1 pore subunit of store-operated calcium release-activated calcium channels. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:89–96. doi: 10.1038/ni1550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gwack Y, et al. Hair loss and defective T- and B-cell function in mice lacking ORAI1. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:5209–5222. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00360-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tareilus E, et al. A Xenopus oocyte beta subunit: evidence for a role in the assembly/expression of voltage-gated calcium channels that is separate from its role as a regulatory subunit. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:1703–1708. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.5.1703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bichet D, et al. The I-II loop of the Ca2+ channel alpha1 subunit contains an endoplasmic reticulum retention signal antagonized by the beta subunit. Neuron. 2000;25:177–190. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80881-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chien AJ, Gao T, Perez-Reyes E, Hosey MM. Membrane targeting of L-type calcium channels. Role of palmitoylation in the subcellular localization of the beta2a subunit. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:23590–23597. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.36.23590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gao T, Chien AJ, Hosey MM. Complexes of the alpha1C and beta subunits generate the necessary signal for membrane targeting of class C L-type calcium channels. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:2137–2144. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.4.2137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Freise D, et al. Mutations of calcium channel beta subunit genes in mice. Biol Chem. 1999;380:897–902. doi: 10.1515/BC.1999.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stokes L, Gordon J, Grafton G. Non-voltage-gated L-type Ca2+ channels in human T cells: pharmacology and molecular characterization of the major alpha pore-forming and auxiliary beta-subunits. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:19566–19573. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401481200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gomes B, et al. Lymphocyte calcium signaling involves dihydropyridine-sensitive L-type calcium channels: facts and controversies. Crit Rev Immunol. 2004;24:425–447. doi: 10.1615/critrevimmunol.v24.i6.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Badou A, et al. Critical role for the beta regulatory subunits of Cav channels in T lymphocyte function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:15529–15534. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607262103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kotturi MF, Hunt SV, Jefferies WA. Roles of CRAC and Cav-like channels in T cells: more than one gatekeeper? Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2006;27:360–367. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2006.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matza D, et al. A Scaffold Protein, AHNAK1, Is Required for Calcium Signaling during T Cell Activation. Immunity. 2008;28:64–74. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matza D, et al. Requirement for AHNAK1-mediated calcium signaling during T lymphocyte cytolysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009 doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902844106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zweifach A. Target-cell contact activates a highly selective capacitative calcium entry pathway in cytotoxic T lymphocytes. J Cell Biol. 2000;148:603–614. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.3.603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murakami M, et al. Pain perception in mice lacking the beta3 subunit of voltage-activated calcium channels. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:40342–40351. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203425200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sprent J, Cho JH, Boyman O, Surh CD. T cell homeostasis. Immunol Cell Biol. 2008 doi: 10.1038/icb.2008.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Park JH, et al. Suppression of IL7Ralpha transcription by IL-7 and other prosurvival cytokines: a novel mechanism for maximizing IL-7-dependent T cell survival. Immunity. 2004;21:289–302. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Manicassamy S, et al. Requirement of calcineurin a for the survival of naive T cells. J Immunol. 2008;180:106–112. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.1.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ueffing N, Schuster M, Keil E, Schulze-Osthoff K, Schmitz I. Up-regulation of c-FLIP short by NFAT contributes to apoptosis resistance of short-term activated T cells. Blood. 2008;112:690–698. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-02-141382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Entschladen F, et al. Signal transduction--receptors, mediators, and genes. Sci Signal. 2009;2:mr3. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.263mr3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Feske S, Giltnane J, Dolmetsch R, Staudt LM, Rao A. Gene regulation mediated by calcium signals in T lymphocytes. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:316–324. doi: 10.1038/86318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lutz MB, et al. An advanced culture method for generating large quantities of highly pure dendritic cells from mouse bone marrow. J Immunol Methods. 1999;223:77–92. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(98)00204-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takahashi SX, Miriyala J, Colecraft HM. Membrane-associated guanylate kinase-like properties of beta-subunits required for modulation of voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:7193–7198. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306665101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.He LL, Zhang Y, Chen YH, Yamada Y, Yang J. Functional modularity of the beta-subunit of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Biophys J. 2007;93:834–845. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.101691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Doering CJ, et al. Modified Ca(v)1.4 expression in the Cacna1f(nob2) mouse due to alternative splicing of an ETn inserted in exon 2. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2538. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hayashi K, Altman A. Filamin A is required for T cell activation mediated by protein kinase C-theta. J Immunol. 2006;177:1721–1728. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.3.1721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tavano R, et al. CD28 interaction with filamin-A controls lipid raft accumulation at the T-cell immunological synapse. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:1270–1276. doi: 10.1038/ncb1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Seminario MC, Bunnell SC. Signal initiation in T-cell receptor microclusters. Immunol Rev. 2008;221:90–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Markiewicz MA, Brown I, Gajewski TF. Death of peripheral CD8+ T cells in the absence of MHC class I is Fas-dependent and not blocked by Bcl-xL. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33:2917–2926. doi: 10.1002/eji.200324273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chuvpilo S, et al. Autoregulation of NFATc1/A expression facilitates effector T cells to escape from rapid apoptosis. Immunity. 2002;16:881–895. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00329-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Berridge MJ, Bootman MD, Roderick HL. Calcium signalling: dynamics, homeostasis and remodelling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:517–529. doi: 10.1038/nrm1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pani B, Singh BB. Lipid rafts/caveolae as microdomains of calcium signaling. Cell Calcium. 2009;45:625–633. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2009.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Doering CJ, Hamid J, Simms B, McRory JE, Zamponi GW. Cav1.4 encodes a calcium channel with low open probability and unitary conductance. Biophys J. 2005;89:3042–3048. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.067124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Revy P, Sospedra M, Barbour B, Trautmann A. Functional antigen-independent synapses formed between T cells and dendritic cells. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:925–931. doi: 10.1038/ni713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weissgerber P, et al. Reduced cardiac L-type Ca2+ current in Ca(V)beta2-/- embryos impairs cardiac development and contraction with secondary defects in vascular maturation. Circ Res. 2006;99:749–757. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000243978.15182.c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McRory JE, et al. The CACNA1F gene encodes an L-type calcium channel with unique biophysical properties and tissue distribution. J Neurosci. 2004;24:1707–1718. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4846-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim KB, Lee JS, Ko YG. The isolation of detergent-resistant lipid rafts for two-dimensional electrophoresis. Methods Mol Biol. 2008;424:413–422. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-064-9_32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.