Abstract

The core lipopolysaccharide (LPS) of Aeromonas hydrophila AH-3 and Aeromonas salmonicida A450 is characterized by the presence of the pentasaccharide α-d-GlcN-(1→7)-l-α-d-Hep-(1→2)-l-α-d-Hep-(1→3)-l-α-d-Hep-(1→5)-α-Kdo. Previously it has been suggested that the WahA protein is involved in the incorporation of GlcN residue to outer core LPS. The WahA protein contains two domains: a glycosyltransferase and a carbohydrate esterase. In this work we demonstrate that the independent expression of the WahA glycosyltransferase domain catalyzes the incorporation of GlcNAc from UDP-GlcNAc to the outer core LPS. Independent expression of the carbohydrate esterase domain leads to the deacetylation of the GlcNAc residue to GlcN. Thus, the WahA is the first described bifunctional glycosyltransferase enzyme involved in the biosynthesis of core LPS. By contrast in Enterobacteriaceae containing GlcN in their outer core LPS the two reactions are performed by two different enzymes.

INTRODUCTION

The genus Aeromonas comprises ubiquitous water-borne Gram-negative bacteria, Aeromonas salmonicida subsp. salmonicida is an important pathogen of fish, producing the systemic disease furunculosis (1). On the other hand, mesophilic aeromonads Aeromonas hydrophila HG1 and HG3, Aeromonas veronii biovar sobria HG8/10, and Aeromonas caviae HG4 are human pathogens associated with gastroenteritis, bacteremia, and septicemia in both healthy and immunocompromised individuals (2–3). The aeromonad lipopolysaccharide (LPS)3 is involved in adhesion to epithelial cells (4), resistance to non-immune serum (5), and virulence (6) and plays a major role in the pathogenesis of Aeromonas infections.

As in other Gram-negative bacteria, in the A. hydrophila LPS three domains are recognized: the highly conserved and hydrophobic lipid A; the hydrophilic and highly variable O-antigen polysaccharide (O-PS); and the core oligosaccharide, connecting lipid A and O-antigen. The core domain is usually divided into the inner and outer cores on the basis of sugar composition.

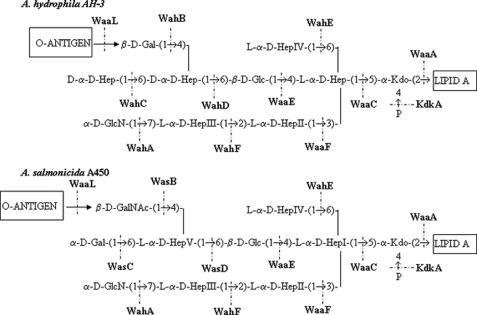

The A. hydrophila and A. salmonicida core LPS structure were determined before (7, 8). The inner core is highly conserved as can be observed in Fig. 1. The genes (wa) coding the eleven glycosyltransferases involved in the A. hydrophila and A. salmonicida core LPS are clustered in three different regions of their respective chromosomes, and the functions for most of them have been elucidated (Fig. 1) (9, 10). A common feature of both core LPS is the presence of a GlcN residue linked by an α-1,7 bond to an l-glycero-d-manno-heptopyranose (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1.

A. hydrophila AH-3 and A. salmonicida A450 oligosaccharide core structures. Shown is the proposed function of gene products involved in core oligosaccharide biosynthesis (7, 8–10).

The mechanism leading to the incorporation of the core GlcN residue in Enterobacteriaceae, such as Klebsiella pneumoniae and Serratia marcescens, requires two distinct enzymatic steps: the incorporation of GlcNAc from UDP-GlcNAc to the LPS core and the deacetylation of the core LPS containing the GlcNAc residue to GlcN. Two genes and their corresponding products were assigned for each function in K. pneumoniae and S. marcescens (11). By contrast only one A. hydrophila or A. salmonicida gene was found, which mutation precluded the incorporation of the core GlcN residue (Fig. 1) (9, 10). In this work we show that a bifunctional enzyme is responsible for the two enzymatic reactions needed to incorporate the core GlcN residue.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Bacterial Strains, Plasmids, and Growth Conditions

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in (Table 1). A. hydrophila strains and Vibrio cholerae N16961 were routinely grown on tryptic soy broth or tryptic soy agar at 30 °C. A. salmonicida A450 was grown at 20 °C. Escherichia coli strains were grown on Luria-Bertani (LB) Miller broth and LB Miller agar at 37 °C. Chloramphenicol (25 μg/ml), rifampicin (100 μg/ml), kanamycin (25 μg/ml), or gentamicin (20 μg/ml) were added to the different media.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristics | Ref. or source |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli strains | ||

| MC1061 λpir | thi thr-1 leu6 proA2 his-4 argE2 lacY1 galK2 | 13, 14 |

| ara-14 xyl-5 supE44 λpir | ||

| HB101 | mcrB mrr hsdS20(rB− mB−) recA13 leuB6 ara-14 proA2 lacY1 galK2 xyl-5 mtl-1 rpsL20(SmR) glnV44 | 15 |

| BL21(λD3) | F−ompT hsdSB (rB− mB−) gal dcm(λDE3) | Novagen |

| K. pneumoniae strains | ||

| 52145 | Serovar O1:K2 (core type 2) | 36 |

| 52145ΔwabH | Non-polar wabH mutant from 52145 | 11 |

| 52145ΔwabN | Non-polar wabN mutant from 52145 | 11 |

| A. hydrophila strains | ||

| AH-3 | O34, Wild type | 37 |

| AH-405 | AH-3, spontaneous RifR | 37 |

| AH-3ΔwahA | Non-polar wahA mutant from AH-405 | 9 |

| AH-3ΔwaaL | Non-polar waaL mutant from AH-405 | 9 |

| AH-3ΔwaaL wahA | Non-polar waaL wahA mutant from AH-405 | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pRK2073 | Helper plasmid, SpcR | 16 |

| pDM4 | λpir-dependent plasmid with sacAB genes, oriR6K, CmR | 17 |

| pDM4ΔwaaL wahA | pDM4 with an in-frame deletion of waaL wahA, CmR | This study |

| pBAD33 | Arabinose-inducible expression vector, CmR | 12 |

| pBAD33-WahA | pBAD33 expressing the wahA gene from A. hydrophila AH-3, CmR | This study |

| pBAD33-GTWahA-CEWahA | pBAD33 expressing independently the GT and CE domains of wahA gene from A. hydrophila AH-3, CmR | This study |

| pBAD33-GTWahA | pBAD33 expressing the GT domain of wahA gene from A. hydrophila AH-3, CmR | This study |

| pBAD3-CEWahA | pBAD33 expressing the CE domain of wahA gene from A. hydrophila AH-3, CmR | This study |

| pBAD33-WahAVc | pBAD33 expressing the wahA gene from V. cholerae N16961, CmR | This study |

| pBAD33Gm-WahAAsA450 | pBAD33-Gm expressing the wahA gene from A. salmonicida A450, GmR | 10 |

| pET28a(+) | IPTG-inducible expression vector, KmR | Novagen |

| pET28a-WahA | pET28a expressing His6-WahA | This study |

| pET28a-GTWahA | pET28a expressing the His6-GTWahA domain | This study |

| pET28b(+) | IPTG-inducible expression vector, KmR | Novagen |

| pET28b-CEWahA | pET28b expressing the CEWahA-His6 domain | This study |

| pBAD18-Cm-WabH | pBAD18-Cm expressing the wabH gene from K. pneumoniae 52145, CmR | 11 |

| pBAD18-Cm-WabN | pBAD18-Cm expressing the wabN gene from K. pneumoniae from 52145, CmR | 11 |

Plasmid Constructions for Gene Overexpression and Mutant Complementation Studies

To overexpress the wahA gene, this gene was PCR-amplified from chromosomal DNA of A. hydrophila AH-3 by using specific primer pairs A (5′-AACGCCCGGGGAAAGGGGCAATCGAGTACA-3′) and D (AACGGTCGACAGCCAGATAACCCAGCATCA). The double underlined nucleotides denote SmaI and SalI restriction sites for primers A and D, respectively. The amplified DNA fragment was digested with SmaI and SalI and ligated to vector pBAD33 (12) digested with both enzymes to obtain pBAD33-WahA.

Primer pairs A and B (5′-CATCGTTCCACTCCTCATTACTCTAGATCCAAGCCATACTCATCCTGAA-3′) and C (5′-TCTAGAGTAATGAGGAGTGGAACGATGGGGCTGGAATCCATCTATCA-3′) and D were used in two sets of asymmetric PCR to amplify DNA fragments of 1227 (AB) and 1174 (CD) bp, respectively. The 27 underlined nucleotides in primers B and C are complementary, including a stop and start codon (bold letters), a ribosomal binding sequence (italic letters), and an XbaI restriction site (double underlined letters). DNA fragments AB and CD were annealed at their overlapping region and amplified by PCR as a single fragment (2374 bp) using primers A and D. This DNA fragment was digested with SmaI and SalI and ligated to vector pBAD33 digested with both enzymes to obtain pBAD33-GTWahA-CEWahA.

DNA fragments of 1198 and 1168 bp were obtained from pBAD33-GTWahA-CEWahA by independent double digestion with SmaI-XbaI and XbaI-SalI, respectively. These fragments were ligated to pBAD33 double-digested with SmaI-XbaI and XbaI-SalI to obtain pBAD33-GTWahA and pBAD33-CEWahA, respectively.

The V. cholerae N16961 (ATCC 39315) wahA homologue (wavL) was amplified using primers VFw (5′-ACTGCGGGGTACCGGAGTGTAAGATGAATATTTTGATGGCCCT-3′) and VRv (5′- ACTGCTCTAGATTAAACCAAAGCCAGCCAT-3′). In primer VFw ribosomal binding site and wavL start codon are denoted in italics and bold letters, respectively. In primer VRv bold letters denote the wavL stop codon complementary nucleotides. The double underlined nucleotides denote KpnI and XbaI restriction sites for primers VFw and VRv, respectively. The amplified DNA fragment was digested with KpnI and XbaI and ligated to vector pBAD33 (12) digested with both enzymes to obtain pBAD33-WahAVc.

The plasmid pBAD33 constructions were transformed into E. coli MC1061 (λpir) (13, 14) by electroporation, plated on chloramphenicol LB agar plates, and incubated at 30 °C. The pBAD33 constructions were then transferred into mutants AH-3ΔwahA (9) and AH-3ΔwaaL wahA (see below) by triparental mating using the mobilizing strain HB101/pRK2073 (15, 16). Transconjugants were selected on plates containing chloramphenicol and rifampicin.

Plasmid Constructions for Histidine-tagged Protein Overexpression

Constructs allowing the expression of N-terminal histidine-tagged WahA (His6-WahA) and His6-GTWahA were based in pET28a. The wahA gene was amplified from pBAD33-WahA with primers A1 (5′-ACGCCATATGAACATATTGATGGCACTCTCC-3′ and D1 (5′-ACGCAAGCTTTATCGAGCAGATAAAGGCATC-3′). The independently expressed GT domain of WahA was amplified with primer pairs A1 and B1 (5′-ACGCAAGCTTCCATCGTTCCACTCCTCATT-3′) from pBAD33-GTWahA-CEWahA. The two amplified DNA fragments were digested with NdeI (double underlined nucleotides in A1) and HindIII (double underlined nucleotides in B1 and D1) and ligated to pET28a digested with the same enzymes to obtain plasmids pET28a-WahA and pET28a-GTWahA. The construct expressing C-terminal histidine-tagged CE domain was performed by amplification of the CE domain using primers C1 (5′-GGTACCCGGGGATCCTCTA[GA]-3′) and D2 (5′-ACGCAAGCTTCCTGAAGACATAGTTACCCCGGATTTTG-3′) from pBAD33-CEWahA. The DNA fragment was digested with XbaI (double underlined nucleotides C1, bracketed nucleotides adjacent to the primer) and HindIII (double underlined nucleotides in D2) and ligated to pET28b digested with the same enzymes to obtain plasmids pET28b-CEWahA.

Preparation of Cell-free Extracts

Genes based in pBAD33 were overexpressed from the arabinose-inducible and glucose-repressible promoter. Repression from the PBAD promoter was achieved by growth in medium containing 0.2% (w/v) d-glucose, and induction was obtained by adding l-arabinose to a final concentration of 0.2% (w/v). The cultures were grown for 18 h at 30 °C in tryptic soy broth medium supplemented with chloramphenicol and 0.2% glucose. These cultures were diluted 1:100 in fresh medium (without glucose) and grown until they reached an A600 nm of ∼0.2. l-arabinose was then added, and the cultures were grown for another 2 h. Repressed controls were maintained in glucose-containing medium.

E. coli BL21(λD3) was used to overexpress genes from the T7 promoter in pET28a(+)- and pET28b(+)-based plasmids. The cultures were grown as above in LB supplemented with kanamycin for 18 h at 37 °C, diluted 1:100 in fresh medium, grown until they reached an A600 nm of ∼0.5, induced by adding isopropyl-1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside, and grown for two more hours.

The cells from induced cultures were harvested, washed once with 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), and frozen until used. To prepare the lysates, cell pellets were resuspended in 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) and sonicated on ice (for a total of 2 min using 10-s bursts followed by 10-s cooling periods). Unbroken cells, cell debris, and membrane fraction were removed by ultracentrifugation at 100,000 × g for 60 min. Protein expression was monitored by SDS-PAGE, and protein contents of cell-free extracts were determined using the Bio-Rad Bradford assay.

His-tagged Protein Purification

Cell-free lysates from E. coli BL21(λD3) harboring pET28a-WahA, pET28a-GTWahA, or pET28b-CEWahA were prepared as above using a phosphate-saline buffer (20 mm sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) containing 500 mm NaCl). His6-tagged proteins were purified by affinity chromatography on a fast-protein liquid chromatography system (Amersham Biosciences) using 1-ml HiTrap chelating HP columns (Amersham Biosciences) previously loaded with nickel sulfate and equilibrated with the phosphate-saline buffer. The columns were washed with phosphate-saline buffer containing 5 mm imidazole (10 column volumes), and the His-tagged proteins were eluted by a continuous gradient of 50–500 mm imidazole in phosphate-saline buffer. The buffer in the eluted proteins was exchanged into 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) and the proteins concentrated.

Mutant Construction

The chromosomal in-frame AH-3ΔwaaL wahA was constructed by allelic exchange as described by Milton et al. (17). The four primers used to obtain this mutant were 2.1A (5′-ACGCGTCGACCGTCTATGGCTACTCCAAGC-3′), 2.1.B (5′-CCCATCCACTAAACTTAAACAACCACGTCGGGTCAATTCGT-3′), 3.1C (5′-TGTTTAAGTTTAGTGGATGGGTTTCTTGGCCTGCCGCTC-3′), and 3.1D (5′-ACGCGTCGACAGATATCTGGCAAGCCGATA-3′). The double underlined nucleotides denote SalI sites, and the single underlined ones denote complementary bases. Two asymmetric PCRs were carried out to obtain two DNA fragments (2.1A–2.1B and 3.1C–3.1D) that were annealed at their overlapping regions and PCR-amplified as a single DNA fragment using primers 2.1A and 3.1D. The amplified in-frame deletion was purified, SalI-digested, ligated into SalI-digested and phosphatase-treated pDM4 vector, electroporated into E. coli MC1061 (λpir), and plated on chloramphenicol LB agar plates at 30 °C to obtain pDM4ΔwaaL wahA. Triparental mating as above was used to transfer pDM4ΔwaaL wahA into the spontaneous rifampicin-resistant AH-3 strain A. hydrophila AH-405 to introduce the double deletion mutation into the chromosome of A. hydrophila AH-3 by homologous recombination using the λpir replication-dependent feature of the plasmid, which contains the counterselectable marker sacB. Transconjugants were selected on plates containing chloramphenicol and rifampicin at 30 °C. PCR analysis confirmed that the plasmid had integrated correctly into the chromosomal DNA. To complete the allelic exchange, the integrated suicide plasmid was forced to recombine out of the chromosome by growth on agar plates containing 15% sucrose. The deletion mutant was selected based on its survival on sucrose plates and the loss of the chloramphenicol-resistant marker of plasmid pDM4ΔwaaL wahA. The mutation was confirmed by sequencing the whole construction in an amplified PCR product.

LPS Isolation and SDS-PAGE

Cultures for analysis of LPS were grown in tryptic soy broth at 30 °C. LPS was purified by the method of Galanos (18) resulting in a 2.3% yield. For screening purposes LPS was obtained after proteinase K digestion of whole cells (19). LPS samples were separated by SDS-PAGE or SDS-Tricine-PAGE and visualized by silver staining as previously described (19, 20).

Large Scale Isolation and Mild Acid Degradation of LPS

Dry bacterial cells of each mutant in 25 mm Tris·HCl buffer containing 2 mm CaCl2, pH 7.63 (10 ml/g), were treated at 37 °C with RNase, DNase (24 h, 1 mg/g each), and then with Proteinase K (36 h, 1 mg/g). The suspension was dialyzed and lyophilized, and the LPS was extracted by the Galanos (18) or phenol-water (21) procedures.

A portion of the LPS (∼50 mg) from each strain was heated with aqueous 2% HOAc (6 ml) at 100 °C for 45 min. The precipitate was removed by centrifugation (13,000 × g, 20 min) and the supernatant was fractionated on a column (56 × 2.6 cm) of Sephadex G-50 (S) in 0.05 m pyridinium acetate buffer, pH 4.5, with monitoring using a differential refractometer. An oligosaccharide fraction was obtained in a yield 9–20% depending on the strain.

Mass Spectrometry

Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectra were acquired on a Voyager DE-PRO instrument (Applied Biosystems) equipped with a delayed extraction ion source. Ion acceleration voltage was 20 kV, grid voltage was 14 kV, mirror voltage ratio was 1.12, and delay time was 100 ns. Samples were irradiated at a frequency of 5 Hz by 337 nm photons from a pulsed nitrogen laser. Post source decay was performed using an acceleration voltage of 20 kV. The reflectron voltage was decreased in ten successive 25% steps. Mass calibration was obtained with a maltooligosaccharide mixture from corn syrup (Sigma). A solution of 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid in 20% CH3CN in water at a concentration of 25 mg/ml was used as the MALDI matrix. One microliter of matrix solution and 1 μl of the sample were premixed and than deposited on the target. The droplet was allowed to dry at ambient temperature. Spectra were calibrated and processed under computer control using the Applied Biosystems Data Explorer software.

GlcNAc-Core LPS-Deacetylase Assay

The ability of independently expressed CEWahA domain to catalyze the deacetylation of GlcNAc residue in LPS was assayed by using LPS from mutant AH-3ΔwaaL wahA in reactions containing AH-3ΔwaaL wahA harboring pBAD33-WahA, pBAD33-GTWahA-CEWahA, pBAD33-GTWahA, or pBAD33-CEWahA cell-free extracts. Assay reactions using UDP-[14C]GlcNAc were carried out in a total of 0.1 ml at a final concentration of 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) containing 10 mm MgCl2, 1 mm dithiothreitol, 0.3 mg of AH-3ΔwaaL wahA acceptor LPS, and 0.2 mg of one or more cell-free extracts. The reactions were started by addition of 0.25 μCi of UDP-[14C]GlcNAc (specific activity of 10.2 mCi/mmol, ICN Biochemicals Inc.). Assays were performed at 37 °C for 2 h and were stopped by adding two volumes of 0.375 m MgCl2 in 95% ethanol and cooling at −20 °C for 2 h. The LPS was recovered by centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 15 min and suspended in 100 μl of water. The LPS was precipitated with 2 volumes of 0.375 m MgCl2 in 95% ethanol; this step was repeated three times to eliminate the unincorporated UDP-[14C]GlcNAc. The LPS was hydrolyzed by resuspension in 100 μl of 0.1 m HCl and heating to 100 °C for 48 h. The labeled residues from the hydrolyzed LPS samples were separated by TLC (Kieselgel 60, Merck Co., Berlin) with n-butanol/methanol/25% ammonia solution/water (5:4:2:1, v/v). The labeled residues were detected by autoradiography using as standards [14C]GlcNAc and [14C]GlcN.

Enzyme assays using purified His6-WahA, His6-GTWahA, and/or CEWahA-His6 were performed as above using different concentrations of UDPGlcNAc (1–800 μm) and acceptor LPS (1–800 μm). The micromolar LPS concentration was determined from the known molecular mass of the core and lipid A sugar backbone from A. hydrophila AH-3 (7) and assuming the O- and N-acylations are identical to those of A. salmonicida (8). The reactions were stopped at different times, and the data from three independent experiments were used to determine the apparent Km for acceptor LPS and enzyme substrate.

RESULTS

The A. hydrophila Gene/Protein wahA/WahA

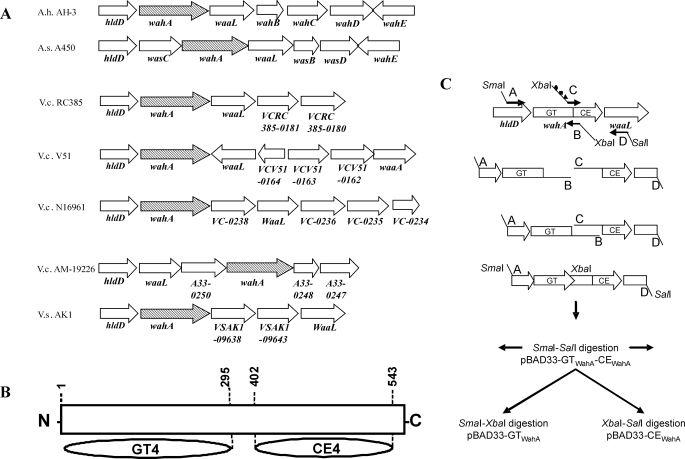

The A. hydrophila 1761-bp wahA gene was found in region 1 of the wa cluster between the genes coding for ADP-l-glycero-β-d-manno-heptose-6-epimerase (hldD) and O-PS ligase (waaL) (9) (Fig. 2A). BLAST (22) analysis showed putative homologue genes in A. hydrophila ATCC7966 (23), A. salmonicida subsp. salmonicida A449 and A450 (24, 10), V. cholerae N16961 (O1 El Tor) (25), and partially genome-sequenced strains V51 (NZ_AAKI00000000), AM-19226 (NZ_AATY00000000), RC385 (NZ_AAKH00000000), and Vibrio shilonii AK1 (NZ_ABCH01000012). In all these strains the wahA homologues are found either between hldD and waaL homologues or near hldD (Fig. 2A). The AH-3ΔwahA LPS mutant showed a relevant glycoform corresponding to the whole core LPS but devoid of the GlcN residue, suggesting that it may be involved in the transfer of the GlcN residue to the core LPS (9).

FIGURE 2.

Localization of wahA homologues, domains, and diagram of the construction of pBAD33 derivatives. A, distribution of wahA homologues among A. hydrophila AH-3 (9), A. salmonicida A450 (23, 10), V. cholerae strains N16961 (25), RC385 (NZ_AAKH00000000), V51 (NZ_AAKI00000000), and AM-19226 (NZ_AATY00000000), and V. shilonii AK1 (NZ_ ABCH01000012). B, diagram showing the domains detected in the WahA protein from A. hydrophila AH-3: glycosyltransferase family 4 (GT4) and carbohydrate esterase family 4 (CE4) (according to CAZy). C, schematic of the construction of pBAD33 derivatives expressing independently the glycosyltransferase (GT) and carbohydrate esterase (CE) domains of WahA from A. hydrophila AH-3. Symbols ●, ■, and ▴ denote stop, ribosomal binding site, and start codon designed in primer C, respectively.

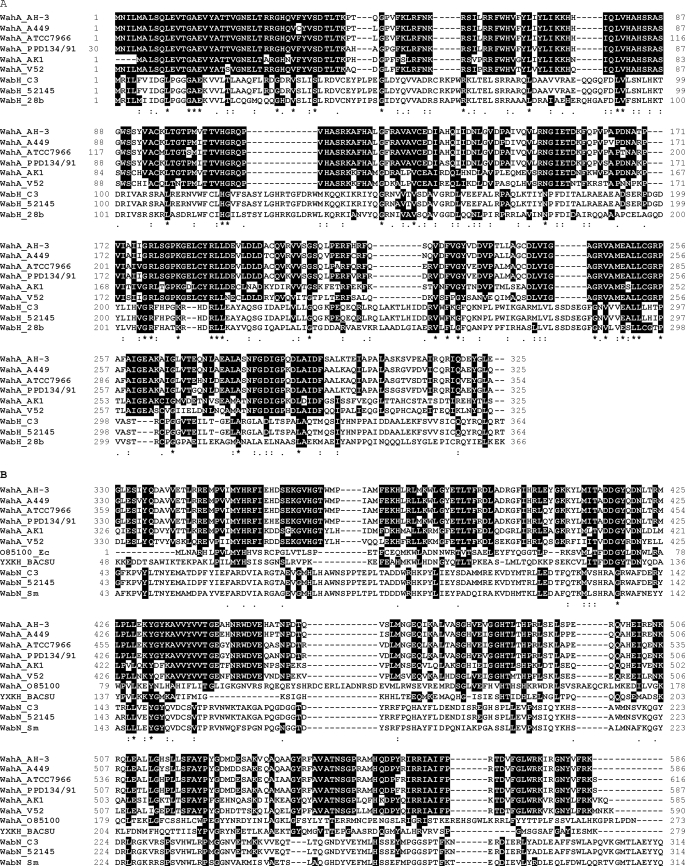

The 586-amino acid residue A. hydrophila WahA protein was similar to the wahA homologues encoded products (64–91% identity and 64–96% similarity). The WahA N-terminal region (residues 1–295) showed similarity to glycosyltransferase enzymes containing the GTB fold grouped in the clan IV glycosyltransferase family GT4 according to the Carbohydrate Active Enzyme data base (CAZy, available on-line) (26). The GT4 family includes lipopolysaccharide N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase (WahH) among other glycosyltransferases. The WahA C-terminal region (residues 402–543) showed similarity to carbohydrate esterase family 4 (CE4); this family includes chitin, peptidoglycan GlcNAc, and peptidoglycan N-acetylmuramic acid deacetylases also according to CAZy. Alignments of C- and N-terminal domains of WahA with glycosyltransferase WabH homologues and two examples of CE4 enzymes are shown in Fig. 3. For comparison non-CE4 WabN deacetylase homologues are included (Fig. 3B). This analysis led us to predict a bifunctional function for the WahA protein. A scanning study of the open reading frames from the available A. hydrophila and A. salmonicida genomes failed to identify better candidates for the deacetylase reaction needed for the incorporation of GlcN to the core LPS as previously shown in K. pneumoniae (11) strengthening the bifunctional hypothesis.

FIGURE 3.

Amino acid sequence alignments of the WahA domains. Alignment of the glycosyltransferase (GT, A) and carbohydrate esterase (CE, B) domains of WahA from A. hydrophila strains AH-3 (9), ATCC7966 (YP_858653.1), PPD134/91 (AAR27963.1), A. salmonicida A449 (YP_001140042.1), V. shilonii AK1 (NZ_ ABCH01000012), and V. cholerae V51 (ZP_01680215.1). The domains GT from WahA protein homologues are aligned with GT4 family enzymes WabH from K. pneumoniae strains C3, 52145, and S. marcescens 28b (11). The domains CE are aligned with CE4 family putative polysaccharide deacetylases from B. subtilis strain 168 (CAB15906.1) and E. coli (AAR00429.1), for comparison the non-CE4 family deacetylase WabN from strains C3, 52145, and 28b are included (11). Alignments were performed with the ClustalW program (38). Identical (*) amino acid residues are denoted by white letters in the white background. Black letters in the gray background denote conserved (:) and semiconserved (.) amino acid substitutions.

Expression of WahA Domains

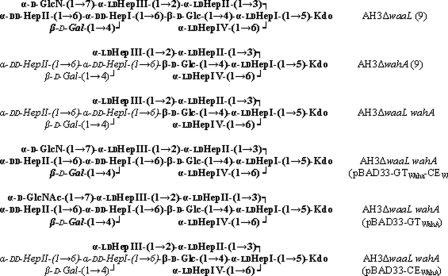

To test the above hypothesis we decided to express independently the two putative domains of WahA under the control of the arabinose promoter (PBAD). By using a PCR asymmetric amplifications approach (see “Experimental Procedures”) we introduced a stop codon for the glycosyltransferase (GTWahA) domain and a start codon with a ribosomal binding site in front of the carbohydrate esterase (CEWahA) domain (Fig. 2C). The pBAD33-GTWahA-CEWahA construct contained the last 55 codons of hldD, the first 324 codons of wahA fused to 3 additional amino acid (DLE) residues (GTWahA), the last 257 codons of wahA with an initiation codon (CEWahA), and the first 119 codons of waaL fused to 13 amino acid residues (VDLQACKLGCFGG). These pBAD33 derivatives were introduced into strain AH-3ΔwahA by triparental mating. SDS-PAGE and SDS-Tricine-PAGE of LPS extracted from strain AH-3ΔwahA (pBAD33-GTWahA-GEWahA) (Fig. 4, A and B, lane 4) was identical to LPS from this mutant complemented with wahA (Fig. 4, A and B, lane 3) and to wild-type LPS (Fig. 4, A and B, lane 1), including the presence of O-PS (Fig. 4A, lanes 1, 3, and 4).

FIGURE 4.

Polyacrylamide gels showing the migration of LPS from AH-3ΔwahA mutant and its complementation. Shown are SDS-PAGE (A) and SDS-Tricine-PAGE (B) analyses of LPS samples from A. hydrophila AH-3 (wild-type, lane 1), mutant AH-3ΔwahA (lane 2), and AH-3ΔwahA containing plasmids pBAD33-WahA (lane 3), pBAD33-GTWahA-CEWahA (lane 4), pBAD33-GTWahA (lane 5), and pBAD33-CEWahA (lane 6). The strains with pBAD33 plasmid derivatives were grown under induced conditions. LPS samples were extracted and analyzed according to Darveau and Hancock (19).

WahA Glycosyltransferase Domain

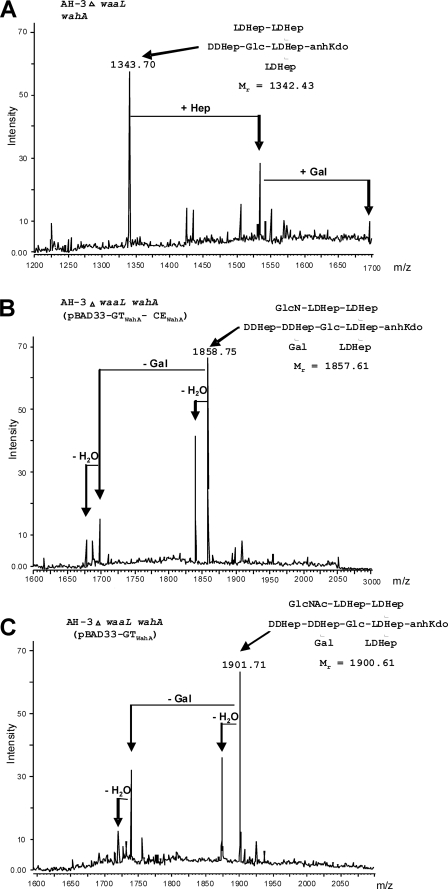

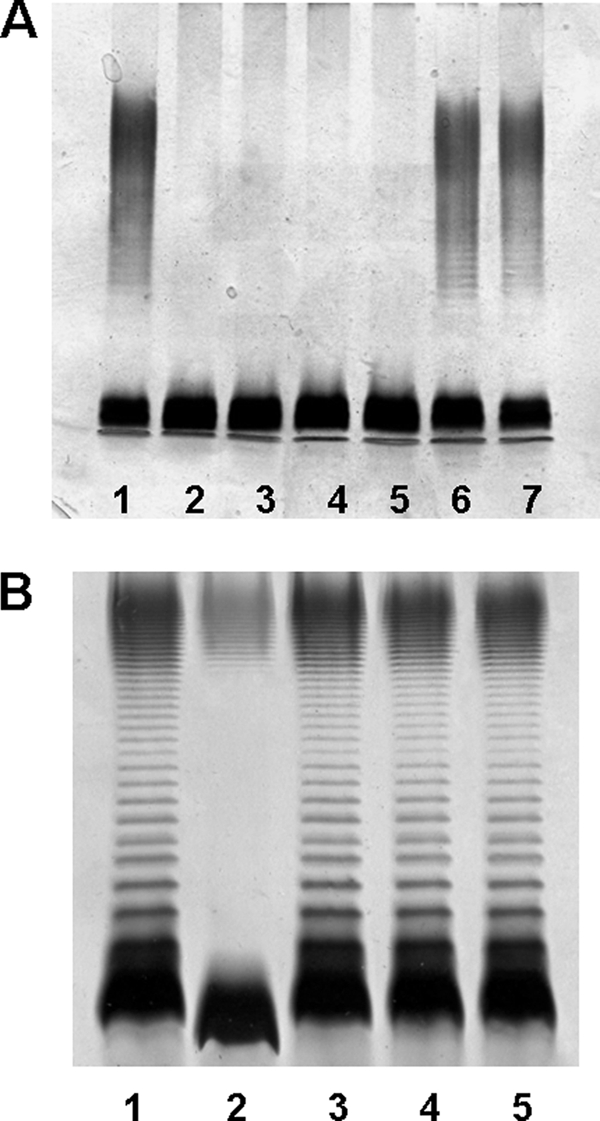

To test the core chemical composition a double waaL wahA mutant was constructed (see “Experimental Procedures”). The chemical composition of the LPS core oligosaccharide fraction obtained by mild acid hydrolysis from AH-3ΔwaaL wahA was similar to that of AH-3ΔwahA (9) showing the presence of Kdo, ld-Hep, Glc, dd-Hep, and Gal without GlcN. In addition, MALDI-TOF analysis showed a pattern of ions similar to that of mutant AH-3ΔwahA with an identical relevant ion at m/z 1343.70 (Figs. 5A and 6). LPS from mutant AH-3ΔwaaL wahA containing pBAD33-GTWahA-CEWahA showed a chemical composition similar to that of AH-3ΔwaaL, including the presence of GlcN. MALDI-TOF analysis of the core oligosaccharide fraction showed the presence of major ions at m/z 1858.75, 1840.70, and 1696.60 corresponding to Kdo, 6Hep, 2Hex, GlcN (whole core LPS), a dehydrated form and Kdo, 6Hep, Hex, and GlcN, respectively (Figs. 5B and 6).

FIGURE 5.

Positive ions MALDI-TOF of acid-released core LPS oligosaccharides. Shown are spectra from A. hydrophila AH-3ΔwaaL wahA (A), AH-3ΔwaaL wahA (pBAD33-GTWahA-CEWahA) (B), and AH-3ΔwaaL wahA (pBAD33-GTWahA) (C). Schematic structures of the most representative compounds are shown in the insets.

FIGURE 6.

Proposed structures of the core oligosaccharides released by mild acid hydrolysis from the LPSs of the A. hydrophila AH-3 mutants alone or complemented. Major glycoforms are shown in bold and components present in non-stoichiometric amounts are shown in italics.

The pBAD33-GTWahA-CEWahA was constructed in such a way that allowed easy subcloning of both domains (pBAD33-GTWahA and pBAD33-CEWahA; see “Experimental Procedures” and Fig. 2C) independently. LPS from AH-3ΔwahA mutant containing pBAD33-GTWahA expressing only the GT domain contained O-PS and migrated similarly to wild-type LPS in SDS-PAGE and SDS-Tricine-PAGE (Fig. 4, A and B, lanes 1 and 5). But compositional analysis of the core LPS oligosaccharide, obtained after LPS mild acid hydrolysis, showed the presence of GlcNAc instead of GlcN. Furthermore, mass spectra analysis of the core LPS from AH-3ΔwaaL wahA (pBAD33-GTWahA) showed major ions at m/z 1901.71, 1883.68, and 1739.55 (Figs. 5C and 6). These ions correspond to molecular mass species 43 atomic mass units higher than those from wild-type core LPS (9). These higher molecular mass ions are in agreement with the single expression of the glycosyltransferase domain. These results suggest that the GT domain is involved in the transfer of GlcNAc to the core LPS.

As expected, the expression of the WahA CE domain in AH-3ΔwahA mutant by introducing pBAD33-CEWahA did not modify the characteristics of the mutant LPS as analyzed by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 4, A and B (lanes 2 and 6)). In addition, core LPS from AH-3ΔwaaL wahA containing pBAD33-CEWahA showed a chemical composition and ion pattern in mass spectra analysis identical to that of AH-3ΔwaaL wahA (data not shown).

WahA Deacetylase Domain

To test if the CEWahA domain is responsible for the deacetylation of the GlcNAc containing core LPS an in vitro enzymatic assay was performed (11). This assay measured the amount of radiolabeled GlcNAc and/or GlcN incorporated into acceptor LPS from UDP-[14C]GlcNAc after acid hydrolysis and TLC separation of the radiolabeled residues. LPS from mutant AH-3ΔwaaL wahA was used as acceptor, and as enzymatic source cell-free extracts from A. hydrophila AH-3ΔwaaL wahA (pBAD33-WahA), AH-3ΔwaaL wahA (pBAD33-GTWahA), and AH-3ΔwaaL wahA (pBAD33-CEWahA) overexpressing the WahA protein, glycosyltransferase, and carbohydrate esterase domains, respectively, were used.

The reaction with extract from AH-3Δ waaL wahA (pBAD33-WahA) allowed the detection of radiolabeled GlcN residue and minor amounts of GlcNAc residue confirming that the enzyme is responsible for the incorporation of GlcN residue into the A. hydrophila core oligosaccharide. The same result was obtained using the AH-3ΔwaaL wahA (pBAD33-GTWahA-CEWahA) extract as enzyme source. In control reactions using AH-3ΔwaaL wahA (pBAD33) extract neither GlcNAc nor GlcN was incorporated into the acceptor LPS (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

In vitro analysis of LPS-GlcNAc deacetylation

Reactions contained LPS from AH-3ΔwaaL wahA, 0.25 μCi of UDP-[14C]GlcNAc, and the soluble fraction of cell-free lysates of AH-3ΔwaaL wahA harboring the indicated plasmids. After 2-h reaction at 37 °C, LPS was recovered by centrifugation, precipitated, washed, and hydrolyzed in 100 μl of 0.1 m HCl before application to a TLC plate. Non-radioactive controls were used to localize the positions of GlcN and GlcNAc. Radioactive spots were scraped and suspended in scintillating liquid, and the radioactivity was measured.

| Protein source | Radioactivity |

|

|---|---|---|

| GlcNAc | GlcN | |

| cpm | ||

| pBAD33 | <100 | <100 |

| pBAD33-WahA | <100 | 1998 |

| pBAD33-GTWahA-CEWahA | <100 | 1990 |

| pBAD33-GTWahA | 1551 | <100 |

| pBAD33-CEWahA | <100 | <100 |

| pBAD33-GTWahA + pBAD33-CEWahA | <100 | 1886 |

The reaction with extract from AH-3Δ waaL wahA (pBAD33-GTWahA) allowed the detection of radiolabeled GlcNAc residue, whereas the reaction containing both AH-3ΔwaaL wahA (pBAD33-GTWahA) and AH-3ΔwaaL wahA (pBAD33-CEWahA) extracts showed radiolabeled GlcN and GlcNAc. In reactions using AH-3ΔwaaL wahA (pBAD33-CEWahA) extract neither GlcNAc nor GlcN was incorporated into the acceptor LPS (Table 2). These results indicate that the WahA protein is bifunctional with its glycosyltransferase domain catalyzing the transfer of the GlcNAc residue from UDP-GlcNAc and the carbohydrate esterase domain responsible for the deacetylation of the GlcNAc residue to GlcN.

In Vitro Kinetics of WahA and Its Domains

Recombinant plasmids expressing N-terminal histidine-tagged WahA (His6-WahA), His6-GTWahA, and C-terminal-tagged CEWahA-His6 were constructed to facilitate the purification of the enzyme and its independently expressed domains GT and CE by affinity chromatography. Reactions performed with cell-free extracts from AH-3ΔwaaL wahA (pET28a-WahA), AH-3ΔwaaL wahA (pET28a-GTWahA), andAH-3ΔwaaL wahA (pET28b-CEWahA) gave results similar to those shown in Table 2. The His6-WahA was used to assay in vitro the incorporation of GlcN from UDP-GlcNAc into acceptor LPS in two sets of experiments. In one the concentration of UDP-GlcNAc was maintained constant at 200 μm, and a range of acceptor LPS from mutant AH-3ΔwaaL wahA was used (1–800 μm). In the other set the acceptor LPS was held constant (200 μm), and different levels of UDP- GlcNAc were used (1–800 μm). The data allow us to determine the apparent Km of His6-WahA for acceptor LPS and UDP-GlcNAc (Table 3). In reactions containing 100 nm each of His6-GTWahA and CEWahA-His6 the apparent Km for both reaction substrates was ∼3-fold higher than the values obtained when using the whole His6-WahA enzyme (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Kinetics of His6-WahA and His6-GTWahA plus CEWahA-His6

The Prism GraphPad program was used to calculate the apparent Michaelis-Menten parameters from three replicate experiments.

| Enzyme | Kcat | Km, UDP-GlcNAc | Km, LPS | Kcat/Km, UDP-GlcNAc | Kcat/Km, LPS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| min−1 | μm | μm | |||

| His6-WahA | 25 ± 5 | 40 ± 3 | 16 ± 2 | 0.6 | 1.5 |

| His6-GTWahA + CEWahA-His6 | 8 ± 1 | 119 ± 15 | 52 ± 3 | 0.06 | 0.15 |

Complementation Assays

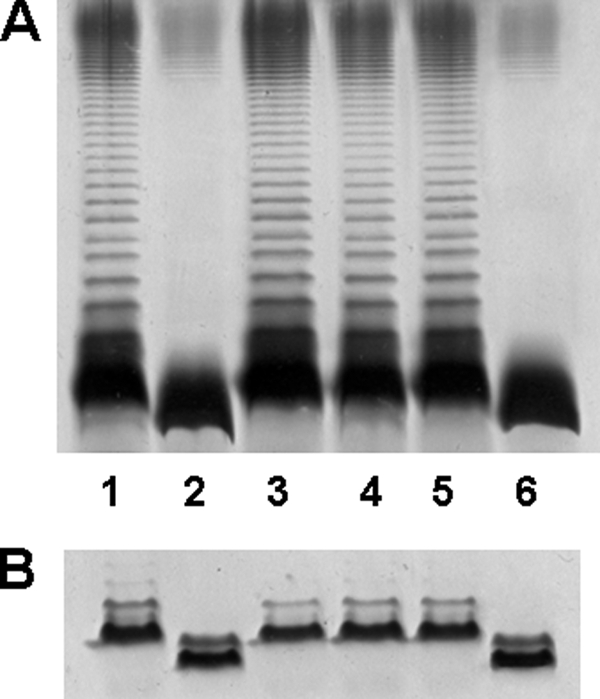

Although the WahA enzyme contains two domains performing GlcNAc transferase and deacetylase functions, this enzyme is unable to complement K. pneumoniae 52145 harboring non-polar mutations in the genes encoding core oligosaccharide GlcNAc transferase (wabH) or deacetylase (wabN) (Fig. 7A), indicating that these enzymes efficiently discriminate between different potential acceptor LPS molecules.

FIGURE 7.

Polyacrylamide gels showing the migration of LPS from K. pneumoniae 52145 and A. hydrophila AH-3ΔwahA mutant and its complementation by wahA homologues. Shown are SDS-PAGE analyses of LPS samples from K. pneumoniae 52145 (lane 1), mutant 52145ΔwabH (lane 2), 52145ΔwabH (pBAD33-WahA) (lane 3), mutant 52145ΔwabN (lane 4), 52145ΔwabN (pBAD33-WahA) (lane 5), 52145ΔwabH (pBAD18-Cm-WabH) (lane 6), and 52145ΔwabN (pBAD18-Cm-WabN) (lane 7) (A); and A. hydrophila AH-3 (wild-type, lane 1), mutant AH-3ΔwahA (lane 2), and AH-3ΔwahA containing plasmids pBAD33-WahA (lane 3), pBAD33Gm-WahAAsA450 (lane 4), and pBAD33-WahAVc (lane 5) (B). The strains with pBAD18 and pBAD33 derivatives were grown under induced conditions. LPS samples were extracted and analyzed according to Darveau and Hancock (19).

The pentasaccharide α-d-GlcN-(1→7)-l-α-d-Hep-(1→2)-l-α-d-Hep-(1→3)-l-α-d-Hep-(1→5)-α-Kdo was found to be shared by A. hydrophila AH-3 (7), A. salmonicida A450 (8, 9), V. cholerae O139 strain MO10-T4, and V. cholerae O1 strains 162 (Ogawa) and 569B (Inaba) (27, 28). Thus, the presence of wahA homologues in A. salmonicida and V. cholerae strongly suggests that these homologues perform the same function in core LPS biosynthesis. To test this possibility the wahAAsA450 and wahAVc genes were subcloned in vector pBAD33 and were introduced into strain AH-3ΔwahA by triparental mating. SDS-PAGE of LPS extracted from AH-3ΔwahA (pBAD33Gm-WahAAsA450) and AH-3ΔwahA (pBAD33-WahAVc) showed the presence of O-antigen, and the migration of the core-lipidA was similar to that of wild-type A. hydrophila AH-3 (Fig. 7B). These results strongly suggest that the two-domain enzyme WahA performs the same function in the studied strains of Aeromonas and V. cholerae. In addition, our results suggest that a similar pentasaccharide should be found in the core LPS of V. shilonii because of the presence of a WahA homologue.

DISCUSSION

The results presented here demonstrated that a single A. hydrophila AH-3 gene encoded a bifunctional WahA protein. The WahA GT domain, expressed independently, appears to be responsible for the transfer of GlcNAc from UDP-GlcNAc as shown by MALDI-TOF analysis of LPS from mutant AH-3ΔwaaL wahA overexpressing this domain (Fig. 5). The independently overexpressed WahA CE domain is responsible for the deacetylation of the GlcNAc residue incorporated to the core LPS by the action of the GT domain, as shown by the in vitro deacetylation assay (Table 2).

By contrast, in the enterobacteria K. pneumoniae and S. marcescens containing GlcN in their core LPS the incorporation of GlcN to the core LPS requires two different enzymes encoded by two independent genes, a glycosyltransferase (wabH) and a deacetylase (wabN) (11). Both the WabH and the WahA GT domain use UDP-GlcNAc but differ in the attachment site of GlcNAc residue in the inner core LPS of Aeromonas and K. pneumoniae or S. marcescens. In agreement with their function both enzymes belong to the CAZy GT4 family, and there is significant similarity between the WahA GT domain and the WabH glycosyltransferase (Fig. 3A). The WahA CE domain belongs to the CE4 family (CAZy and Ref. 26) (Fig. 3B). Position-specific iterated BLAST (29) analysis of WabN suggests a distant relationship to CE4 family members, although this deacetylase does not belong to CAZy family CE4. These differences probably reflect the variation in the attachment site of GlcN residue in the inner core LPS between Aeromonas and K. pneumoniae. Not surprisingly, neither the wabH nor the wabN are able to complement the wahA mutation. In addition the WabN protein is unable to catalyze the deacetylation of the GlcNAc residue in A. hydrophila AH-3 core LPS (data not shown).

The comparison between the in vitro His6-WahA Km for acceptor LPS and UDP-GlcNAc and those of His6-GTWahA and His6-CEWahA acting together shows that, as expected, the bifunctional enzyme is more efficient in catalyzing the GlcN incorporation into the core LPS of A. hydrophila AH-3 than the concerted action of the two domains expressed independently. Although we have used N- and C-terminal tags for the GT and CE domains, respectively, it cannot be ruled out that these tags could diminish a potential interaction between the GT and CE domains and enzyme substrates. On the other hand these in vitro data do not necessarily reflect the in vivo situation.

The advantage in vivo of having these two activities in a single protein in A. hydrophila AH-3 while they are found in two different enzymes in K. pneumoniae is difficult to determine. It just can be hazardous or could be related to the different consequences of the lack of the GlcN residue in each model bacteria. Although wahA mutants still contain O-PS, because the GlcN residue is terminally located on a branch of core LPS (7), wabH and wabN mutants are completely devoid of O-PS, because the GlcN residue is located in the main branch of core LPS in K. pneumoniae and S. marcescens (11). It is clear that a lack of O-antigen LPS in vivo jeopardizes the virulence in both Gram-negative bacteria. In addition, while transcriptional regulation of wahA expression in A. hydrophila should control both GlcNAc transferase and deacetylase reactions, in K. pneumoniae wabH and wabN are transcribed from different promoters, because these two genes are transcribed in opposite directions (11). This fact may suggest the possibility of a different regulation on the GlcNAc transferase and deacetylase reactions in the mentioned bacteria and similar ones.

The WahA enzyme is found in members of the genus Aeromonas and Vibrio that contain the pentasaccharide α-d-GlcN-(1→7)-l-α-d-Hep-(1→2)-l-α-d-Hep-(1→3)-l-α-d-Hep-(1→5)-α-Kdo. From the results obtained it can be predicted that this pentasaccharide should also be present in the core LPS of V. shilonii AK1. The absence of WahA homologues in other Vibrio species suggests the absence of the above pentasaccharide.

Previously it was shown that the E. coli HldE bifunctional protein is involved in the biosynthesis of the core LPS precursor ADP-l-glycero-β-d-manno-heptose. This enzyme contains two functionally different domains, a heptokinase and an adenylyltransferase that could be expressed independently (30). The HldE kinase domain catalyzes the phosphorylation at the 1 position of the d-glycero-β-d-manno-heptose 7-phosphate to generate d-glycero-α,β-d-manno-heptose 1,7-biphosphate (31), the GmhB phosphatase catalyzes the removal of the phosphate at the 7 position to form d-glycero-β-d-manno-heptose 1-phosphate (32), and the adenylyltransferase domain of HldE catalyzes the transfer of AMP to give ADP-d-glycero-β-d-manno-heptose (30, 32). Genomic sequence comparisons show that, in some bacteria, such as Neisseria meningitidis, the bifunctional HldE is replaced by two distinct enzymes, HldA and HldC, which perform their respective functions (32).

Only one putative bifunctional glycosyltransferase involved in core LPS biosynthesis has been described. The E. coli Kdo transferase WaaA was proposed to be responsible for the transfer of two Kdo residues to the LPS precursor lipid IVA (33, 34), but evidence is lacking about the possible existence of two different domains involved in the two reactions catalyzed by this enzyme.

True bifunctional proteins catalyze two independent reactions at separate catalytic sites. This term has been used to describe a single polypeptide with two catalytic activities for which, in some organisms, there are two proteins that carry out the equivalent biochemical reaction (35). Thus the WahA is the first known glycosyltransferase bifunctional enzyme involved in core LPS biosynthesis.

Acknowledgments

We thank Maite Polo for her technical assistance and the Servicios Científico-Técnicos from the University of Barcelona.

This work was supported by Plan Nacional de I + D and Fondo de Investigaciones Sanitarias grants from Ministerio de Educación, Ciencia y Deporte, and Ministerio de Sanidad, Spain and the Generalitat de Catalunya (Centre de Referència en Biotecnologia).

- LPS

- lipopolysaccharide

- CAZy

- Carbohydrate-Active EnZyme data base

- CE

- carbohydrate esterase

- GT

- glycosyltransferase

- Gal

- galactose

- ld-Hep

- l-glycero-d-manno-heptopyranose

- Kdo

- 3-deoxy-d-manno-oct-2-ulosonic acid

- MALDI-TOF

- matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time of flight

- MS

- mass spectrometry

- O-PS

- O-antigen polysaccharide

- Tricine

- N-[2-hydroxy-1,1-bis(hydroxymethyl) ethyl]glycine

- CE4

- carbohydrate esterase family 4.

REFERENCES

- 1.Scott M. (1968) J. Gen. Microbiol. 50, 321–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burke V., Robinson J., Gracey M., Petersen D., Partridge K. (1984) Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 48, 361–366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thornley J. P., Shaw J. G., Gryllos I., Eley A. (1997) Rev. Med. Microbiol. 8, 61–72 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Merino S., Rubires X., Aguilar A., Tomás J. M. (1996) FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 139, 97–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Merino S., Camprubí S., Tomás J. M. (1991) J. Gen. Microbiol. 137, 1583–1590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aguilar A., Merino S., Rubires X., Tomas J. M. (1997) Infect. Immun. 65, 1245–1250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Knirel Y. A., Vinogradov E., Jimenez N., Merino S., Tomás J. M. (2004) Carbohydr. Res. 339, 787–793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang Z., Li J., Vinogradov E., Altman E. (2006) Carbohydr. Res. 341, 109–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jimenez N., Canals R., Lacasta A., Kondakova A. N., Lindner B., Knirel Y. A., Merino S., Regué M., Tomás J. M. (2008) J. Bacteriol. 190, 3176–3184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jimenez N., Lacasta A., Vilches S., Reyes M., Vazquez J., Aquilini E., Merino S., Regué M., Tomás J. M. (2009) J. Bacteriol. 191, 2228–2236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Regué M., Izquierdo L., Fresno S., Jimenez N., Piqué N., Corsaro M. M., Parrilli M., Naldi T., Merino S., Tomás J. M. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 36648–36656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guzman L. M., Belin D., Carson M. J., Beckwith J. (1995) J. Bacteriol. 177, 4121–4130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Casadaban M. J., Cohen S. N. (1980) J. Mol. Biol. 138, 179–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rubirés X., Saigi F., Piqué N., Climent N., Merino S., Albertí S., Tomás J. M., Regué M. (1997) J. Bacteriol. 179, 7581–7586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boyer H. W., Roulland-Dussoix D. J. (1969) J. Mol. Biol. 41, 459–472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Figurski D. H., Helinski D. R. (1979) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 76, 1648–1652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Milton D. L., O'Toole R., Horstedt P., Wolft-Watz H. (1996) J. Bacteriol. 178, 1310–1319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Galanos C., Lüderitz O., Westphal O. (1969) Eur. J. Biochem. 9, 245–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Darveau R. P., Hancock R. E. W. (1983) J. Bacteriol. 155, 831–838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hitchcock P. J., Brown T. M. (1983) J. Bacteriol. 154, 269–277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Westphal O., Jann K. (1965) Methods Carbohydr. Chem. 5, 83–89 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Altschul S. F., Gish W., Miller W., Myers E. W., Lipman D. J. (1990) J. Mol. Biol. 215, 403–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seshadri R., Joseph S. W., Chopra A. K., Sha J., Shaw J., Graf J., Haft D., Wu M., Ren Q., Rosovitz M. J., Madupu R., Tallon L., Kim M., Jin S., Vuong H., Stine O. C., Ali A., Horneman A. J., Heidelberg J. F. (2006) J. Bacteriol. 188, 8272–8282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reith M. E., Singh R. K., Curtis B., Boyd J. M., Bouevitch A., Kimball J., Munholland J., Murphy C., Sarty D., Williams J. J., Nash H. E., Jonson S. C., Brown L. L. (2008) BCM Genomics 9, 427–441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heidelberg J. F., Eisen J. A., Nelson W. C., Clayton R. A., Gwinn M. L., Dodson R. J., Haft D. H., Hickey E. K., Peterson J. D., Umayam L., Gill S. R., Nelson K. E., Read T. D., Tettelin H., Richardson D., Ermolaeva M. D., Vamathevan J., Bass S., Qin H., Dragoi I., Sellers P., McDonald L., Utterback T., Fleishmann R. D., Nierman W. C., White O., Salzberg S. L., Smith H. O., Colwell R. R., Mekalanos J. J., Venter J. C., Fraser C. M. (2000) Nature 406, 477–483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lairson L. L., Henrissat B., Davies G. J., Whiters S. G. (2008) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 77, 521–555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Knirel Y. A., Widmalm G., Senchenkova S. F., Jansson P. E., Weintraub A. (1997) Eur. J. Biochem. 247, 402–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vinogradov E. V., Bock K., Holst O., Brade H. (1995) Eur. J. Biochem. 233, 152–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Altschul S. F., Madden T. L., Schäffer A. A., Zhang J., Zhang Z., Miller W., Lipman D. J. (1997) Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 3389–3402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Valvano M. A., Marolda C. L., Bittner M., Glaskin-Clay M., Simon T. L., Klena J. D. (2000) J. Bacteriol. 182, 488–497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McArthur F., Andersson C. E., Loutet S., Mowbray S. L., Valvano M. A. (2005) J. Bacteriol. 187, 5292–5300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Valvano M. A., Messner P., Kosma P. (2002) Microbiology 148, 1979–1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brozek K. A., Hosaka K., Robertson A. D., Raetz C. R. H. (1989) J. Biol. Chem. 264, 6956–6966 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Belunis C. J., Raetz C. R. (1992) J. Biol. Chem. 267, 9988–9997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.James C. L., Viola R. E. (2002) Biochemistry 41, 3720–3725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nassif X., Fournier J. M., Arondel J., Sansonetti P. J. (1989) Infect. Immun. 57, 546–552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Merino S., Camprubí S., Tomás J. M. (1992) Infect. Immun. 60, 4343–4349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thompson J. D., Higgins D. G., Gibson T. J. (1994) Nucleic Acids Res. 22, 4673–4680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]