Abstract

ATR (ATM and Rad3-related) initiates a DNA damage signaling pathway in human cells upon DNA damage induced by UV and UV-mimetic agents and in response to inhibition of DNA replication. Genetic data with human cells and in vitro data with Xenopus egg extracts have led to the conclusion that the kinase activity of ATR toward the signal-transducing kinase Chk1 depends on the mediator protein Claspin. Here we have reconstituted a Claspin-mediated checkpoint system with purified human proteins. We find that the ATR-dependent phosphorylation of Chk1, but not p53, is strongly stimulated by Claspin. Similarly, DNA containing bulky base adducts stimulates ATR kinase activity, and Claspin acts synergistically with damaged DNA to increase phosphorylation of Chk1 by ATR. Mutations in putative phosphorylation sites in the Chk1-binding domain of Claspin abolish its ability to mediate ATR phosphorylation of Chk1. We also find that a fragment of Claspin containing the Chk1-binding domain together with a domain conserved in the yeast Mrc1 orthologs of Claspin is sufficient for its mediator activity. This in vitro system recapitulates essential components of the genetically defined ATR-signaling pathway.

introduction

DNA damage checkpoints delay cell cycle progression in response to DNA damage to maintain genomic integrity. In mammalian cells, two major signaling pathways that mediate the checkpoint response have been described: the ATM2 → Chk2 pathway that is activated mainly, but not exclusively, by double-strand breaks and the ATR → Chk1 pathway that is primarily activated by UV and UV-mimetic chemical agents as well as replication fork stalling due to DNA damage or nucleotide depletion (1). Upon activation, ATR phosphorylates Chk1 on Ser317 and Ser345 (2, 3) in a manner dependent on the mediator protein Claspin (4–6). Claspin was originally identified as a Chk1-interacting protein in Xenopus laevis egg extracts, where it was shown to be indispensable for ATR-dependent phosphorylation of Chk1 (7). Subsequent studies identified a 57-amino acid minimal Chk1-binding domain (CKBD) of Xenopus Claspin (8). Mutations in this domain abrogate Claspin-Chk1 association as well as the phosphorylation of Chk1 by ATR in both Xenopus (8–10) and human systems (11, 12).

Genetic studies in human cell lines and in vitro studies with HeLa cell-free extracts and Xenopus egg extracts have identified many proteins including RPA, the ATR-ATRIP heterodimer, the Rad17-RFC·9-1-1 and Timeless·Tipin checkpoint complexes, TopBP1, and Claspin as essential components for phosphorylation of Chk1 and activating the DNA damage or replication checkpoints (1). It was found that under certain reaction conditions, TopBP1 alone was sufficient to promote phosphorylation of Chk1 by ATR (13). Recently, using a defined system, we found that under physiologically relevant ionic strength, Chk1 phosphorylation by ATR was both TopBP1-dependent and DNA-dependent (14, 15). The ATR → Chk1 signaling pathway in these in vitro studies was not dependent on the other checkpoint proteins known to be required for ATR activation. A fully reconstituted checkpoint system that incorporates all of the genetically defined components would greatly facilitate mechanistic studies of this important DNA damage response pathway. In the current study, we have analyzed the contribution of Claspin to phosphorylation of Chk1 by ATR. We find that Claspin strongly stimulates the TopBP1-dependent ATR phosphorylation of Chk1 but not phosphorylation of other ATR substrates such as p53, and this stimulation is amplified by damaged DNA. Claspin functions by increasing the affinity of ATR for Chk1, and mutations in the CKBD of Claspin abrogate its mediator activity. We have identified a fragment of Claspin that contains the CKBD together with a domain conserved in the Mrc1 yeast orthologs of Claspin that is sufficient to stimulate ATR phosphorylation of Chk1. Our minimal checkpoint system provides a useful platform for analyzing the function of the Claspin mediator in the ATR-signaling pathway.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Antibodies and DNA

Chk1 phospho-Ser345 and p53 phospho-Ser15 antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). Chk1, p53, and GST antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA), and FLAG M2 antibodies were from Sigma. A 2-kb linear DNA fragment modified with Benzo[a]pyrene diol epoxide (BPDE) was prepared as described previously (15, 16). Both single-stranded and double-stranded undamaged DNAs stimulate the reaction (14–16); however, because the stimulation of ATR kinase was much stronger, we carried out all our experiments with BPDE-DNA in this study.

Purification of Checkpoint Proteins

Native ATR-ATRIP, GST-TopBP1-His, GST-TopBP1-C fragment, GST-p53, His-Chk1 kinase dead (Chk1-kd), and FLAG-tagged full-length Claspin and Claspin Δ851 were all purified as described previously (14–17). Point mutations were produced in Claspin by site-directed mutagenesis according to the QuikChange® instructions (Stratagene). GST-tagged fragments of Claspin were generated by subcloning into pGEX-4T1 (GE Healthcare) and purification from Escherichia coli with glutathione agarose according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Kinase Assays

The procedure was similar to our previously described system (16). Briefly, kinase assay reactions contained 12 mm Hepes, pH 7.9, 1.2 mm MgCl2, 0.4 mm ATP, 0.3 mm dithiothreitol, 0.6% polyethylene glycol 6000, 35 mm KCl, 25 ng/μl bovine serum albumin, and 1 μm microcystin in a 10-μl final volume. Unless otherwise indicated, 0.25 nm purified ATR-ATRIP was incubated for 15 min at 30 °C with 0.5 nm recombinant full-length TopBP1 or TopBP1-C fragment, 10 nm Chk1-kd or p53, with the indicated concentrations of Claspin or DNA. The reactions were terminated by the addition of SDS-PAGE loading buffer and separated by 10% SDS-PAGE. Chk1 or p53 phosphorylation was detected by immunoblotting using the indicated phospho-specific antibodies, and the levels of total Chk1 and p53 proteins were subsequently detected by immunoblotting the same membrane. Levels of phosphorylation were quantified using the ImageQuant 5.2 software after scanning the immunoblots. The highest level of Chk1 phosphorylation in each experiment was set equal to 100, and the levels of phosphorylated Chk1 in the other lanes were determined relative to this value, except in Fig. 1, where the phosphorylation in the first (control) lane was set equal to 1 to facilitate the comparison between p53 and Chk1. The averages from at least three independent experiments were graphed, and the error bars indicate the average deviation from the mean (see Figs. 1–5).

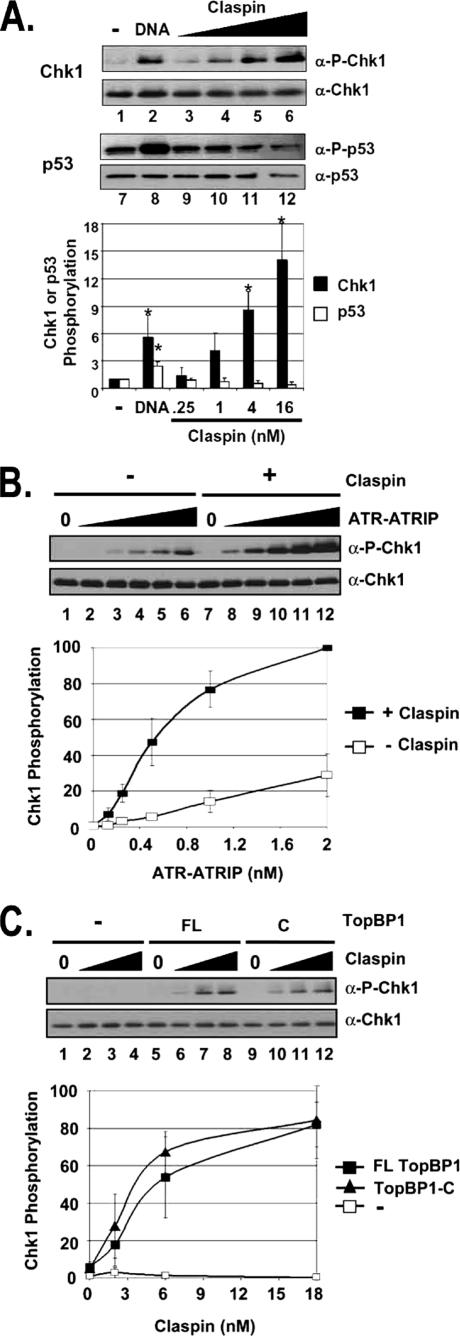

FIGURE 1.

Claspin specifically stimulates TopBP1-dependent ATR phosphorylation of Chk1 in a defined system. A, Claspin specifically stimulates ATR phosphorylation of Chk1 but not p53. All reactions contain 0.25 nm ATR and 0.5 nm TopBP1. Reactions 1–6 contain 10 nm His-Chk1kd, and reactions 7–12 contain 10 nm GST-p53. 1 ng of BPDE-modified 2-kb linear DNA was added to reactions in lanes 2 and 8. The values in lanes 1 and 7 are normalized to 1. ATR kinase activity was determined by immunoblotting for phospho-Chk1 (α-P-Chk1), Chk1, phospho-p53 (α-P-p53), and p53 as indicated. The graph shows quantitative analysis of the data from three independent experiments conducted under identical conditions. DNA stimulates both Chk1 and p53 phosphorylation, whereas Claspin stimulates Chk1 but not p53 phosphorylation. Values that are statistically different (T value <0.03 in the paired t test) than the control reactions (lanes 1 or 7) are indicated with an asterisk. The error bars indicate the average deviation from the mean. B, Claspin-mediated phosphorylation of Chk1 is dependent on ATR. 0, 0.125, 0.25, 0.5, 1, and 2 nm purified ATR-ATRIP was added to reactions lacking Claspin (lanes 1–6) or containing 16 nm Claspin (lanes 7–12) in addition to 0.5 nm TopBP1 and 10 nm Chk1kd. The results from three experiments were quantified and plotted. 0.25 nm ATR-ATRIP was chosen for the later kinase reactions. C, ATR activation by Claspin is dependent on TopBP1, and the C-terminal fragment of TopBP1 is sufficient. Kinase reactions containing 0, 2, 6, or 18 nm Claspin were performed without TopBP1 (lanes 1–4), with 1 nm full-length TopBP1 (FL) (lanes 5–8), or with 1 nm of the TopBP1-C fragment (C) (lanes 9–12).

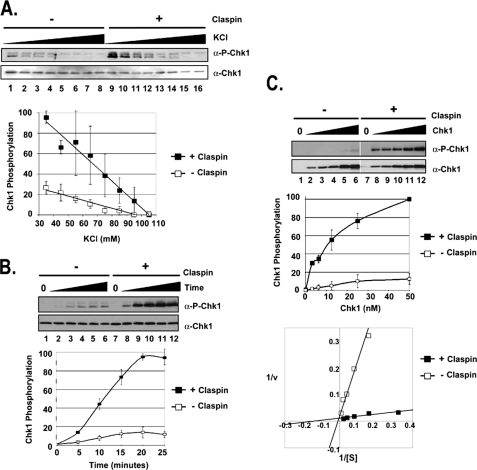

FIGURE 2.

Claspin mediates the phosphorylation of Chk1 by ATR through a salt-sensitive mechanism that increases the affinity of ATR for Chk1. A, Claspin stimulation of ATR phosphorylation of Chk1 is sensitive to ionic strength. Kinase assays were carried out with ATR-ATRIP (0.25 nm), Chk1 (10 nm), and TopBP1-C (0.5 nm) under different ionic strength conditions (35–105 mm KCl) in the absence or presence of 16 nm Claspin. The error bars indicate the average deviation from the mean. α-P-Chk1, phospho-Chk1; α-P-Chk1-p53, phospho-p53. B, kinetics of Claspin stimulation of phosphorylation of Chk1 by ATR. Kinase assays were performed as described in the legend for Fig. 1 with 10 nm His-Chk1 and incubated for the indicated amount of time without Claspin or with 16 nm Claspin. C, Claspin affects the affinity of ATR for Chk1. Kinase assays were performed as described in B, except that the Chk1 concentration varied from 0 to 50 nm. The results from three experiments were quantified and plotted as before (top graph) or with the Lineweaver-Burk format of 1/v versus 1/[S] (bottom graph), which allows for calculating the Km = −1/x-intercept and the Vmax = 1/y-intercept. The equation for the lines fitting the data for reactions lacking Claspin is y = 2.1049x + 0.0175, and for reactions containing Claspin, it is y = 0.0784x + 0.011. The units for Vmax have been determined by standardizing the signal from Western blotting to the amount of Pi incorporated in experiments containing radioactive [γ-32P]ATP. v, velocity.

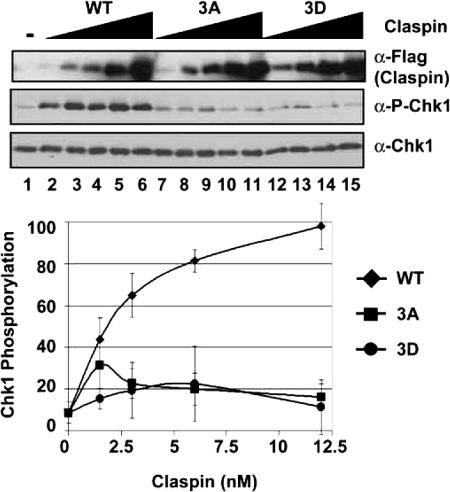

FIGURE 3.

Claspin-mediated ATR activation is dependent on the putative phosphorylation sites in the Chk1-binding domain of Claspin. Kinase assays were carried out with ATR-ATRIP, HisChk1-kd, and TopBP1-C fragment as described in the legend for Fig. 2 except with 35 mm KCl and with 0, 1.5, 3, 6, or 12 nm Claspin wild type (WT) or Thr916, Ser945, and Ser982 mutated to alanine (3A) or aspartic acid (3D). The graph shows quantitative analysis of the data from five independent experiments conducted under identical conditions. The error bars indicate the average deviation from the mean. α-P-Chk1, phospho-Chk1.

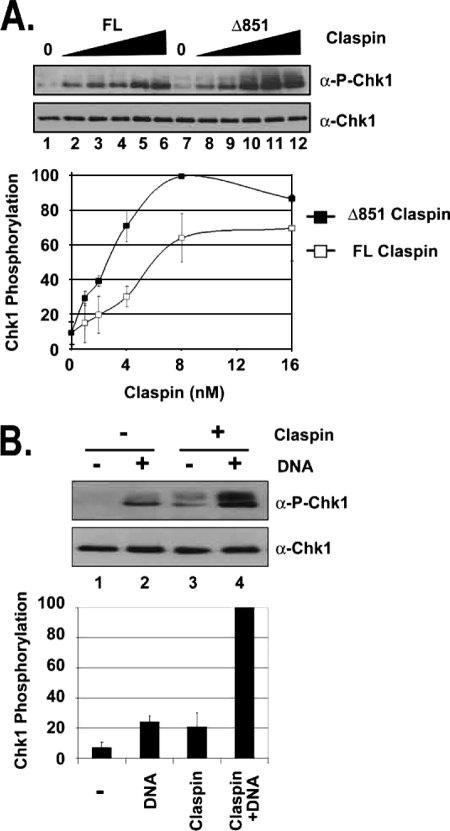

FIGURE 4.

The C terminus of Claspin is sufficient to stimulate Chk1 phosphorylation by ATR and acts synergistically with damaged DNA. A, the C terminus of Claspin is sufficient for stimulation of ATR phosphorylation of Chk1. Kinase assays were carried out with ATR-ATRIP, HisChk1-kd, and TopBP1 as described in the legend for Fig. 1 except with 0, 1, 2, 4, 8, or 16 nm full-length (FL) Claspin or Claspin Δ851 fragment. The error bars indicate the average deviation from the mean. α-P-Chk1, phospho-Chk1. B, Claspin and DNA synergistically stimulate ATR Kinase. Kinase assays were carried out with ATR-ATRIP, HisChk1-kd, and TopBP1-C fragment as described in A except with 75 mm KCl and with or without 16 nm Claspin Δ851 and 2 ng of BPDE-damaged DNA.

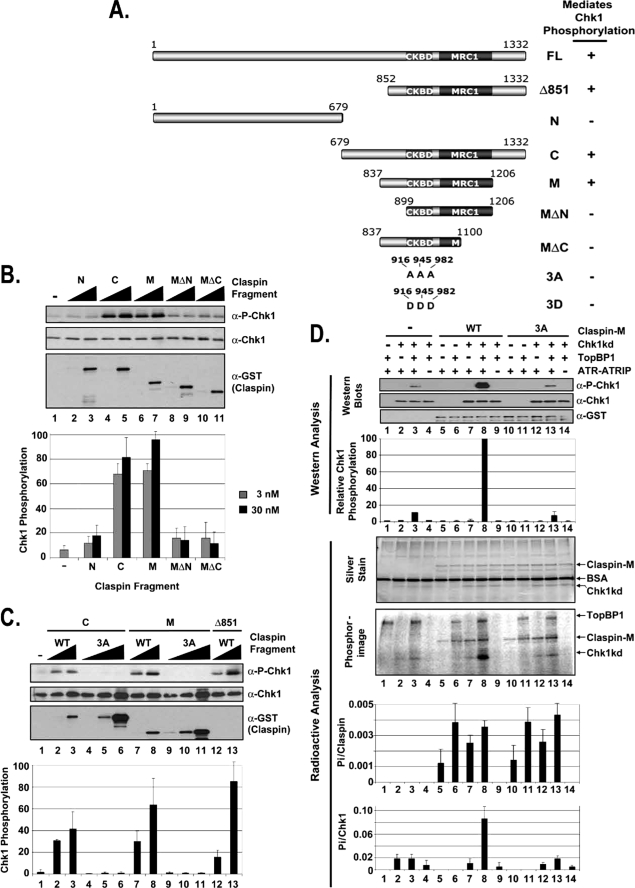

FIGURE 5.

Identification of the minimal functional domain in Claspin. A, schematic of the Claspin fragments and summary of their ability to mediate Chk1 phosphorylation by ATR. The locations of the putative phosphorylation site mutations at Thr916, Ser945, and Ser982 (3A and 3D) in the CKBD are indicated. The Mrc1-like domain (MRC1, amino acids 1045–1203) is defined in the Pfam protein families data base as a putative domain of average length of 142.3 amino acids that is found to be the most conserved region in Mrc1 (31). B, stimulation of ATR phosphorylation of Chk1 by Claspin fragments. Kinase assays were carried out with ATR-ATRIP, HisChk1-kd, and TopBP1 as described in the legend for Fig. 1 except with 0, 3, or 30 nm of the indicated Claspin fragment. The error bars indicate the average deviation from the mean. α-P-Chk1, phospho-Chk1. C, mutations in the Chk1-binding domain of the Claspin fragments abolish their ability to stimulate ATR phosphorylation of Chk1. Kinase assays were carried out with ATR-ATRIP, HisChk1-kd, and TopBP1 as described in B except with 0, 3, 30, or 300 nm of the indicated Claspin fragment. D, kinase assays were carried out with ATR-ATRIP, Chk1-kd, and TopBP1 as described in the legend for Fig. 1 except with the addition of [γ-32P]ATP to monitor the total phosphorylation in the reaction. 25 nm wild-type (WT) Claspin-M fragment or the Claspin-M fragment containing alanine mutations in the putative phosphorylation sites (3A) were included into the reactions as indicated. Half of the kinase reaction was loaded onto a gel for analysis by immunoblotting for phospho-Chk1 and Chk1, and the other half of the reaction was loaded onto a separate gel for analysis by silver staining and phosphorimaging as indicated. BSA, bovine serum albumin.

In the experiments with [γ-32P]ATP, 20 μCi of radiolabel was included in the kinase reactions, and the final concentrations of ATP and bovine serum albumin were lowered to 0.1 mm and 10 ng/μl, respectively. After separation on SDS-PAGE, the proteins were silver-stained, and then the gel was dried and analyzed by phosphorimaging. For quantification purposes, a phosphate standard curve was generated by spotting dilutions of the kinase mixture. The amount of Pi incorporated into Claspin or Chk1 was divided by the known amount of protein included in the reaction mixture to obtain the number of phosphates incorporated into each Claspin or Chk1 molecule. The averages from three independent experiments were graphed, and the error bars indicate the average deviation from the mean (see Fig. 5D).

RESULTS

Claspin Specifically Stimulates ATR Kinase Activity Toward Chk1

It has been reported that ATR phosphorylation of Chk1 on Ser345, but not phosphorylation of other ATR substrates, such as p53, is dependent on Claspin in vivo (6). Having obtained the requisite proteins in highly purified forms, we set out to test this model in a defined system. Because it has been shown that under certain reaction conditions TopBP1 is sufficient to activate ATR kinase on the Chk1 substrate (13, 14), we used this platform to test the contribution of Claspin to the phosphorylation of either Ser345 of Chk1 or Ser15 of p53 by ATR. The results from such an experiment are shown in Fig. 1A. Claspin significantly stimulates the kinase activity of ATR toward Chk1 (lanes 3–6 versus lane 1) but not p53 (lanes 9–12 versus lane 7). Similarly, DNA containing bulky adducts stimulates the TopBP1-dependent phosphorylation of both Chk1 (lane 2) and p53 (lane 8) by ATR, consistent with our previous reports (14–16). Thus, although damaged DNA stimulates ATR kinase activity on either substrate, the stimulatory effect of Claspin is specific for Chk1.

Analysis of the in Vitro Requirements for Claspin-mediated Chk1 Phosphorylation

We next tested the optimal requirement and specificity for two essential components, ATR-ATRIP and TopBP1, in the Claspin-dependent kinase reactions. The results shown in Fig. 1B indicate that the phosphorylation of Chk1 is completely dependent on ATR-ATRIP (lanes 1 and 7), and increasing the ATR-ATRIP concentration in the kinase reactions resulted in a corresponding increase of Chk1 phosphorylation (lanes 2–6). Importantly, there was up to 10-fold more phosphorylation of Chk1 when Claspin was included in the reaction mixture (lanes 8–12).

We have previously shown that the ATR kinase activity in our in vitro system is dependent on TopBP1 (14) and that a carboxyl-terminal (C) fragment of TopBP1 is sufficient for conferring damaged DNA-dependent stimulation of ATR (15). We wished to determine whether the Claspin-dependent stimulation of Chk1 phosphorylation by ATR is also dependent on TopBP1 and whether the C-fragment is sufficient. In Fig. 1C, increasing amounts of Claspin were added to reactions lacking TopBP1 (lanes 1–4) or containing full-length (FL) TopBP1 (lanes 5–8) or the C-fragment of TopBP1 (lanes 9–12). Even at the highest concentration of Claspin, no Chk1 phosphorylation is detectable in reactions lacking TopBP1 (lane 4), indicating that Claspin alone is not sufficient. However, ATR phosphorylates Chk1 in reactions containing either the full length TopBP1 or the C-fragment of TopBP1, and under these conditions, the phosphorylation is completely dependent on Claspin (compare lanes 5 and 8 with lanes 9 and 12). This experiment, for the first time, reconstitutes a TopBP1-dependent and Claspin-dependent in vitro ATR → Chk1 signaling system.

Mechanistic Details of Claspin-dependent Phosphorylation of Chk1

Next, we wished to analyze the mechanism by which Claspin stimulates the ATR kinase in more detail. First, we performed ATR kinase reactions under conditions of increasing ionic strength (Fig. 2A). As we have previously reported, the TopBP1-mediated ATR kinase activity is highly sensitive to the ionic strength of the reaction (lanes 1–8) (14). We find that the stimulatory effect of Claspin is also sensitive to the ionic strength (lanes 9–16), with the 2-fold difference in the slopes of the lines of TopBP1- and TopBP1+Claspin-stimulated kinase activity, indicating that the Claspin-dependent stimulation of ATR is twice as sensitive. This sensitivity to ionic strength is likely due to salt-sensitive protein-protein interactions of Claspin required to mediate the kinase reaction.

The results from kinetic experiments indicate that Claspin increases the initial rate of the kinase reaction by ∼5-fold (Fig. 2B). To better understand the mechanistic basis of the effect of Claspin in the reaction, we conducted the experiment shown in Fig. 2C in which the rate of Chk1 phosphorylation was measured as a function of Chk1 concentration in ATR kinase reactions lacking Claspin (lanes 1–6) or containing Claspin (lanes 7–12). Analysis of these data by the Lineweaver-Burk plot (18) enabled us to estimate the Vmax and Km for the kinase reactions with Chk1 substrate and the effects of Claspin on the kinetic parameters. We find that there is less than a 2-fold difference in Vmax for reactions containing Claspin (∼91 fmol of Pi/min) than for reactions lacking Claspin (∼57 fmol of Pi/min). However, the Km is decreased ∼17-fold by Claspin (Km ∼ 7 nm with Claspin; Km ∼ 120 without Claspin). Although this ATR kinase reaction is relatively complex because of the requirement for multiple protein-protein interactions, the large change in the Km indicates that the stimulation of Chk1 phosphorylation observed in the presence of Claspin is primarily achieved by increasing the affinity of ATR for Chk1.

Mutations in the CKBD of Claspin Abolish Its Mediator Activity

In vivo studies have suggested that the phosphorylations of Thr916, Ser945, and Ser982 in the CKBD of Claspin are important for Chk1 phosphorylation by ATR during the checkpoint response to DNA damage or stalled replication forks (12). We wished to test this observation in our in vitro system to ascertain the validity of this system and possibly gain insight into the role of Claspin phosphorylation in the checkpoint response. To this end, we used wild-type Claspin, Claspin carrying Thr/Ser → Ala mutations at the phosphorylation sites (3A), or the Thr/Ser → Asp phosphomimetic replacements (3D) at these sites in our in vitro assay. All three proteins were made in the baculovirus/insect cell expression systems. When the three proteins were tested in our assay, the wild-type (WT) Claspin stimulated the TopBP1-dependent phosphorylation of Chk1 up to ∼10-fold, whereas the mutants had only modest or no effect (Fig. 3). These results further support the notion that our in vitro system is a faithful representation of the in vivo ATR → Chk1 signaling pathway.

ATR Phosphorylation of Chk1 Is Stimulated by the C Terminus of Claspin and Is Further Stimulated by Damaged DNA

We have previously reported that Claspin is a DNA-binding protein and identified DNA-binding domains in fragments encompassing the N- and C-terminal halves of the protein (17). We examined the effects of these fragments on Chk1 phosphorylation by ATR to better define the role of Claspin in mediating ATR kinase activity. As seen in Fig. 4A, either full-length (FL) Claspin (lanes 2–6) or a C-terminal fragment of Claspin (Δ851) (lanes 8–12), which contains the CKBD, stimulates ATR phosphorylation of Chk1 up to 10-fold, and the C-terminal fragment appears to be more active than full-length Claspin, under these experimental conditions, suggesting that the N-terminal domain of Claspin may serve as a regulator of the reaction. Because this fragment has DNA binding activity (17), and we have previously shown that DNA stimulates the kinase activity of ATR in the presence of TopBP1 (14, 15), we wished to test the effect of adding both Claspin and DNA to the kinase reaction. The results are shown in Fig. 4B. Under these conditions, the addition of either damaged DNA (lane 2) or Claspin (lane 3) results in ∼4-fold more phosphorylation of Chk1 when compared with the control reaction (lane 1). However, the addition of both DNA and Claspin to the reaction (lane 4) resulted in ∼20-fold more phosphorylation than the control reaction, which suggests synergy of DNA and Claspin in stimulating ATR kinase because the stimulation is more than 2-fold higher than the sum of the kinase activity with either DNA alone or Claspin alone.

Identification of a Minimal Functional Domain of Claspin

To more precisely define the region of Claspin sufficient to mediate ATR phosphorylation of Chk1 in our system, we generated the fragments of Claspin summarized in Fig. 5A. Fragments spanning the N-terminal half (N) and C-terminal half (C) of Claspin were purified from E. coli and tested in the ATR kinase assay (Fig. 5B). The addition of the C-terminal half of Claspin resulted in ∼10-fold stimulation of ATR phosphorylation of Chk1 (compare lanes 4 and 5 with lane 1), whereas the N-terminal half of Claspin did not have a significant effect on ATR kinase activity (lanes 2 and 3). We further truncated the C-fragment, and discovered that the middle (M) region (lanes 6 and 7) was as active as the C-fragment. However, further deletions from the N or C termini of the M fragment (MΔN, lanes 8 and 9, and MΔC, lanes 10 and 11) abolish the stimulatory effect. Therefore, we conclude that the 354 amino acids between amino acid 852 and 1206 are sufficient for Claspin to mediate Chk1 phosphorylation by ATR.

To confirm our findings that mutations of the putative phosphorylation sites in the CKBD of full-length Claspin abrogate its function (Fig. 3), we also tested the effect of changing amino acids 916, 945, and 982 to alanine (3A) in the Claspin fragments. The results are shown in Fig. 5C. Mutating the putative phosphorylation sites abolishes the ability of either Claspin fragment C (compare lanes 4–6 with lanes 2 and 3) or Claspin fragment M (compare lanes 9–11 with lanes 7 and 8) to stimulate phosphorylation of Chk1 by ATR, consistent with the results obtained with the full-length protein produced in insect cells. Because these mutated residues are putative phosphorylation sites, and the bacterially produced protein is not phosphorylated, we wished to measure the amount of phosphorylation that occurs at these sites during the kinase reaction. We added radiolabeled ATP to the kinase reactions shown in Fig. 5D and quantified the amount of Pi incorporated in Claspin and Chk1. The addition of wild-type Claspin M-fragment to the kinase reaction containing Chk1-kd, TopBP1, and ATR-ATRIP (lane 8) resulted in 10- or 4-fold more Chk1 phosphorylation as determined by Western analysis of Ser345 phosphorylation or radioactive analysis of total Chk1 phosphorylation, respectively, than in the equivalent reactions lacking Claspin (lane 3) or containing Claspin with the 3A mutation (lane 13). In the presence of ATR-ATRIP, ∼0.001 Pi was incorporated per Claspin molecule. This was mediated by ATR-ATRIP because there was no measurable radioactivity incorporated into wild-type (WT) Claspin (lane 9) or 3A mutant (lane 14) in the absence of ATR-ATRIP, and about 4-fold more was incorporated when TopBP1 was also added to the reaction (lanes 6 and 11). These results indicate that Claspin is phosphorylated by ATR under these reaction conditions, however very inefficiently. Importantly, the amount of Claspin phosphorylation is not affected when the putative phosphorylation sites are mutated to alanine (compare lanes 5–8 with lanes 10–13), indicating that the three Ser/Thr residues (which do not match the ATR phosphorylation consensus sequence) involved in Claspin-mediated Chk1 phosphorylation are not phosphorylated in this system.

DISCUSSION

Development of a Human Reconstituted Checkpoint System

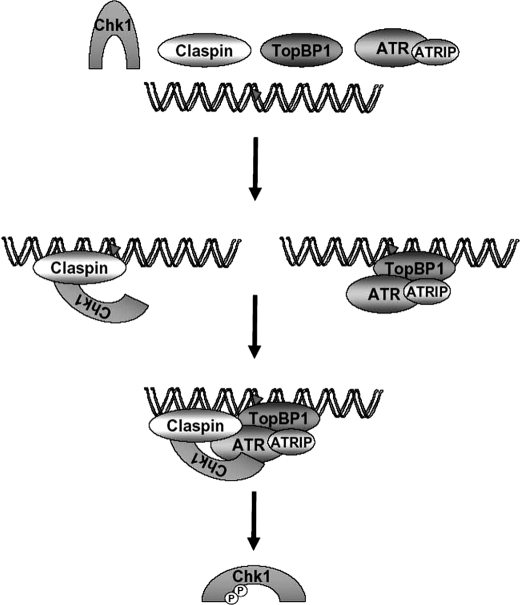

The genetically defined minimal set of components required for activation of the ATR → Chk1 pathway of checkpoint signaling in humans includes DNA, RPA, ATR-ATRIP, TopBP1, Rad17-RFC·9-1-1, Timeless·Tipin, Claspin, and Chk1. We previously described a minimal human in vitro checkpoint system consisting of damaged DNA, TopBP1, ATR-ATRIP, and Chk1 (14, 15). In this study, we have further developed the system to recapitulate essential components of the genetically defined ATR-signaling pathway by incorporating Claspin. We find that the combination of TopBP1 with Claspin is sufficient to strongly stimulate the phosphorylation of Chk1 by ATR and that damaged DNA further stimulates the phosphorylation (Fig. 6).

FIGURE 6.

Model for Claspin-mediated Phosphorylation of Chk1 by ATR. ATR-ATRIP may be recruited to DNA by several mechanisms, all of which eventually lead to enhanced kinase activity. Thus, TopBP1 recruits ATR-ATRIP to DNA containing bulky adducts (indicated by the triangle). Claspin binds to both DNA and Chk1 and increases the affinity of ATR for Chk1 through a mechanism that requires the Chk1-binding domain and the MRC1-like domain. Note that this is one mechanism by which ATR and its co-activators can be recruited to DNA. There are alternative pathways of recruiting ATR such as by RPA, mismatch repair proteins, and other factors. The circled P indicates phosphorylation.

Several studies in which HeLa cell-free extracts were used to analyze ATR kinase activity have been reported (11, 19, 20). Although these studies have been valuable, the presence of other kinases in the extracts makes the results open to alternative interpretations and limits their usefulness. Therefore, we have focused on developing a defined ATR checkpoint system with purified proteins. Partially reconstituted ATR checkpoint systems have been described in other species, including X. laevis (13, 21, 22) and Saccharomyces cerevisiae (23–27). A bona fide in vitro checkpoint system should depend on all of the checkpoint proteins necessary for Chk1 phosphorylation as defined by genetic data. By these criteria, our in vitro system falls short of representing the human in vivo checkpoint pathway. However, as it is often encountered in biochemical assays, by employing special reaction conditions such as high enzyme concentrations or non-physiological bivalent cations such as Mn2+ instead of Mg2+, the in vitro reactions circumvent some of the requirements for the reaction in vivo. Such systems nevertheless do contribute to the understanding of the biochemical function in question and to the ultimate development of in vitro systems that by all criteria recapitulate the in vivo reaction. From that perspective, our study may be considered a significant advance over the previous work aimed at establishing an in vitro checkpoint system. We are able to stimulate the ATR kinase phosphorylation of Chk1 by checkpoint components known to be required: DNA, TopBP1, and Claspin.

In Vitro Systems with Xenopus Claspin

Claspin was originally discovered in Xenopus egg extracts (7) and was shown to be indispensable for ATR-dependent phosphorylation of Chk1 in response to stalled DNA replication forks in cell-free reactions (7, 22). Reconstitution of a Claspin-dependent reaction with purified Xenopus components has been attempted (21, 22) but appears to be complicated by the requirement for Claspin to be phosphorylated (8, 10, 21). Mutations of two serines (Ser864 and Ser895) in Xenopus Claspin, which have been shown to be phosphorylated during the checkpoint response (8), abrogate its ability to interact with Chk1 (8, 10, 28) and to mediate Chk1 phosphorylation by ATR in egg extracts (8). These two serines are located in highly conserved repeats of about 10 amino acids in the CKBD of Claspin. Human Claspin contains three of these conserved repeats, and our results suggest that although mutations of the equivalent putative phosphorylated residues (Thr916, Ser945, and Ser982) abrogate the mediator function of Claspin (Figs. 3 and 5C), the residues are not phosphorylated in our system (Fig. 5D). Phospho-specific antibodies have been used to demonstrate that Thr916 is phosphorylated in human cell lines after DNA damage (12, 29, 30), and because the 3A mutation abolishes the ability of human Claspin to mediate Chk1 phosphorylation (12), it was concluded that phosphorylation of these sites is required for Claspin function. The results from our reconstituted system raise some doubt about this conclusion and suggest that it is the mutations, not the phosphorylation states of the Ser/Thr residues, that disrupt the mediator function of Claspin. In fact, phosphomimetic mutations at these amino acids abolish function in our system (Fig. 3) and in Xenopus egg extracts (8). The identity of the kinase that phosphorylates Claspin on these residues is unknown. These sites do not match the ATR consensus sequence ((S/T)Q), but ATR appears to be required to activate the kinase that phosphorylates these residues (8). An initial report implicated Chk1 (12); however, this was subsequently disputed (30). We conducted the experiments in this report with kinase-inactive Chk1 to avoid this complication. However, we did not detect a difference in the Claspin-dependent activation of ATR in reactions containing wild-type Chk1 (data not shown), suggesting that if there is significant phosphorylation of these sites by Chk1, it does not significantly affect Claspin function in our assay. Ultimately, our system will be useful for evaluating the functional significance of Claspin phosphorylation after identification of the kinase.

In Vitro System with Yeast Proteins

Using purified proteins, it was recently reported that the budding yeast Claspin ortholog, Mrc1, stimulates phosphorylation of the Chk1 functional ortholog, Rad53, by the Mec1 kinase (ATR ortholog) in a manner similar to our findings (26). However, in contrast to our system in which Claspin-dependent ATR phosphorylation of Chk1 is dependent on the presence of TopBP1 (Fig. 1C), the yeast Mrc1Claspin-dependent checkpoint system did not require the addition of the yeast TopBP1 homolog, Dpb11 (26). Similarly, the Rad17-RFC/9-1-1-dependent yeast Mec1ATR checkpoint system did not depend on the presence of Dpb11TopBP1 (25), although it was later reported that Dpb11TopBP1 acted synergistically with Rad17-RFC/9-1-1 in that system (24). We further demonstrated that the C terminus of TopBP1 is sufficient for Claspin-dependent stimulation of Chk1 phosphorylation by ATR. This fragment of TopBP1 is also sufficient to confer the damaged DNA-dependent stimulation of ATR, and in fact, damaged DNA acts synergistically with Claspin in our system (Fig. 4B).

Conclusion

Our minimal checkpoint system is the closest approximation to the genetically defined human ATR → Chk1 signaling pathway in that it incorporates ATR-ATRIP, Chk1, TopBP1, DNA, and Claspin for optimal ATR kinase activity on Chk1. As such, we believe this system will provide a useful platform for analyzing the contribution of the other components known to be required in the ATR-signaling pathway and ultimately defining the roles of the individual components by experimental designs addressing specific questions in a readily controllable in vitro system. However, with current technology, it is not possible to evaluate the spatio-temporal factors that play an important role in the cellular response to the complexity of DNA damage in the nucleus and its effect on cell-cycle progression.

Acknowledgment

We thank M. Kemp for critical reading and useful comments.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant GM32833 (to A. S.).

- ATM

- ataxia telangiectasia-mutated

- ATR

- ATM and Rad3-related

- ATRIP

- ATR-interacting protein

- CKBD

- Chk1-binding domain

- BPDE

- Benzo[a]pyrene diol epoxide

- GST

- glutathione S-transferase

- kd

- kinase dead

- RPA

- replication protein A.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sancar A., Lindsey-Boltz L. A., Unsal-Kaçmaz K., Linn S. (2004) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 73, 39–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu Q., Guntuku S., Cui X. S., Matsuoka S., Cortez D., Tamai K., Luo G., Carattini-Rivera S., DeMayo F., Bradley A., Donehower L. A., Elledge S. J. (2000) Genes Dev. 14, 1448–1459 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhao H., Piwnica-Worms H. (2001) Mol. Cell. Biol. 21, 4129–4139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chini C. C., Chen J. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 30057–30062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lin S. Y., Li K., Stewart G. S., Elledge S. J. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 6484–6489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu S., Bekker-Jensen S., Mailand N., Lukas C., Bartek J., Lukas J. (2006) Mol. Cell. Biol. 26, 6056–6064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kumagai A., Dunphy W. G. (2000) Mol. Cell 6, 839–849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kumagai A., Dunphy W. G. (2003) Nat. Cell Biol. 5, 161–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yoo H. Y., Jeong S. Y., Dunphy W. G. (2006) Genes Dev. 20, 772–783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jeong S. Y., Kumagai A., Lee J., Dunphy W. G. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 46782–46788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clarke C. A., Clarke P. R. (2005) Biochem. J. 388, 705–712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chini C. C., Chen J. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 33276–33282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kumagai A., Lee J., Yoo H. Y., Dunphy W. G. (2006) Cell 124, 943–955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Choi J. H., Lindsey-Boltz L. A., Sancar A. (2007) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 13301–13306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choi J. H., Lindsey-Boltz L. A., Sancar A. (2009) Nucleic Acids Res. 37, 1501–1509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Choi J. H., Sancar A., Lindsey-Boltz L. A. (2009) Methods 48, 3–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sar F., Lindsey-Boltz L. A., Subramanian D., Croteau D. L., Hutsell S. Q., Griffith J. D., Sancar A. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 39289–39295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lineweaver H., Burk D. (1934) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 56, 658–666 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yoshioka K., Yoshioka Y., Hsieh P. (2006) Mol. Cell 22, 501–510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shiotani B., Zou L. (2009) Mol. Cell 33, 547–558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kumagai A., Kim S. M., Dunphy W. G. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 49599–49608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hashimoto Y., Tsujimura T., Sugino A., Takisawa H. (2006) Genes Cells 11, 993–1007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sweeney F. D., Yang F., Chi A., Shabanowitz J., Hunt D. F., Durocher D. (2005) Curr. Biol. 15, 1364–1375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Navadgi-Patil V. M., Burgers P. M. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 35853–35859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Majka J., Niedziela-Majka A., Burgers P. M. (2006) Mol. Cell 24, 891–901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen S. H., Zhou H. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 18593–18604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mordes D. A., Nam E. A., Cortez D. (2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 18730–18734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yan S., Lindsay H. D., Michael W. M. (2006) J. Cell Biol. 173, 181–186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bennett L. N., Clarke P. R. (2006) FEBS Lett. 580, 4176–4181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bennett L. N., Larkin C., Gillespie D. A., Clarke P. R. (2008) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 369, 973–976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Finn R. D., Tate J., Mistry J., Coggill P. C., Sammut S. J., Hotz H. R., Ceric G., Forslund K., Eddy S. R., Sonnhammer E. L., Bateman A. (2008) Nucleic Acids Res. 36, D281–D288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]