Abstract

Pathways for tailoring and processing vitamins into active cofactor forms exist in mammals that are unable to synthesize these cofactors de novo. A prerequisite for intracellular tailoring of alkylcobalamins entering from the circulation is removal of the alkyl group to generate an intermediate that can subsequently be converted into the active cofactor forms. MMACHC, a cytosolic cobalamin trafficking chaperone, has been shown recently to catalyze a reductive decyanation reaction when it encounters cyanocobalamin. In this study, we demonstrate that this versatile protein catalyzes an entirely different chemical reaction with alkylcobalamins using the thiolate of glutathione for nucleophilic displacement to generate cob(I)alamin and the corresponding glutathione thioether. Biologically relevant thiols, e.g. cysteine and homocysteine, cannot substitute for glutathione. The catalytic turnover numbers for the dealkylation of methylcobalamin and 5′-deoxyadenosylcobalamin by MMACHC are 11.7 ± 0.2 and 0.174 ± 0.006 h−1 at 20 °C, respectively. This glutathione transferase activity of MMACHC is reminiscent of the methyltransferase chemistry catalyzed by the vitamin B12-dependent methionine synthase and is impaired in the cblC group of inborn errors of cobalamin disorders.

INTRODUCTION

Although mammals cannot synthesize vitamins de novo, they can process inactive precursor forms obtained from the diet to the active cofactor forms. This capacity is exemplified with cobalamin or derivatives of vitamin B12, which can be introduced from the diet to the cell in a variety of inactive forms. Intracellular processing leads to methylcobalamin (MeCbl)3 and 5′-deoxyadenosylcobalamin (AdoCbl) (1–3), which support the activities of methionine synthase and methylmalonyl-CoA mutase, respectively (4, 5). In fact, even provision of an active cofactor form, e.g. MeCbl, the dominant form of the cofactor found in human plasma (6), demands its conversion to an intermediate that can be subsequently partitioned for AdoCbl and MeCbl synthesis. This is necessary to meet the cellular needs for both cofactor forms (see Fig. 1), i.e. the inability to convert incoming MeCbl (or AdoCbl) into a common intermediate that can be utilized for the synthesis of both active cofactor forms would lead to a functional deficiency of one or the other cofactor derivative. An analogous situation exists with mammalian folate metabolism, where the circulating form of the cofactor, 5-methyltetrahydrofolate, must be dealkylated to tetrahydrofolate by the action of methionine synthase to release the cofactor into a form that can be subsequently used in other folate-dependent reactions (7).

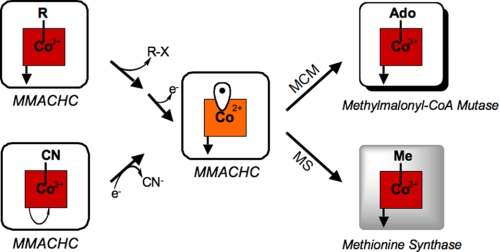

FIGURE 1.

Reactions catalyzed by MMACHC. CNCbl in the presence of NADPH and an oxidoreductase is converted via a reductive decyanation reaction to cyanide and cob(II)alamin. Alternatively, alkylcobalamins undergo nucleophilic displacement to give cob(I)alamin, which is oxidized to cob(II)alamin and subsequently converted to the active cofactor forms for the vitamin B12-dependent enzymes methionine synthase (MS) and methylmalonyl-CoA mutase (MCM).

Early insights into the complexity of a trafficking pathway for vitamin B12 were provided by clinical genetics studies on patients with inherited disorders of cobalamin metabolism (8, 9). These studies led to the distinction of eight complementation groups (cblA–G and mut), two of which (cblG and mut) correspond to the vitamin B12-dependent enzymes (10). The rest were postulated to play auxiliary functions in a pathway for tailoring and escorted delivery of the vitamin to its intracellular targets (11).

Mutations in an early protein in the trafficking pathway, MMACHC (for methylmalonic aciduria type C and homocystinuria), corresponding to the cblC class of cobalamin disorders, compromise activities of both vitamin B12 enzymes. Indeed, mutations at the cblC locus are the most common class of inborn errors in cobalamin metabolism (12). Individuals belonging to the cblC group of cobalamin disorders are among the most severely affected and exhibit homocystinuria, methylmalonic aciduria, and associated neurological, developmental, hematological, and ophthalmologic complications (13). We have demonstrated recently that when the incoming cofactor is cyanocobalamin (CNCbl; or vitamin B12), MMACHC catalyzes its reductive decyanation to yield cob(II)alamin and cyanide (Fig. 1) (1). The reaction involves a facile one-electron reduction (14), with the reducing equivalents being furnished by NADPH via a cytosolic flavoprotein oxidoreductase such as methionine synthase reductase (15) or a protein described as novel reductase 1 (16). The physiological relevance of this reaction is demonstrated by ex vivo studies showing that normal but not cblC patient fibroblasts are able to convert exogenously supplied [57Co]CNCbl to radiolabeled AdoCbl and MeCbl, respectively (2). Furthermore, the impairment of this decyanase function in cblC patients explains their poorly responsive phenotype to CNCbl supplementation (17, 18). However, a comparable one-electron reduction of alkylcobalamins (Scheme 1, Reaction 1) is estimated to represent an approximately −1-V (versus the standard hydrogen electrode) redox potential (14, 19), a thermodynamic challenge that is beyond the reach of biological reducing systems. This raises an important mechanistic question, namely does the same protein deploy an entirely different catalytic strategy for dealkylation compared with decyanation (Scheme 1)? And if human MMACHC, a small protein with a native molecular mass of 29 kDa and devoid of metal or organic cofactors (1), exhibits this versatility, what is the mechanistic strategy that allows catalysis of both one-electron (for CNCbl) and presumably two-electron (for alkylcobalamins) chemistry, depending on the nature of the cobalamin it encounters? In this study, we demonstrate that upon binding varied natural and unnatural alkylcobalamins, MMACHC converts them via a glutathione transferase activity to cob(I)alamin and the corresponding glutathione thioether. Chemically, this reaction is reminiscent of the methyl transfer reaction catalyzed by vitamin B12-dependent methionine synthase, in which the thiolate group of homocysteine displaces the methyl group from MeCbl to yield the thioether, methionine, and cob(I)alamin (20). The physiological relevance of the alkyl transfer activity of MMACHC is demonstrated by the impaired ability of cblC patient fibroblasts to convert exogenously supplied MeCbl to AdoCbl, which is observed in control cell lines.

SCHEME 1.

Alternative reaction mechanisms for dealkylation of alkylcobalamin.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Protein Purification

Recombinant MMACHC His-tagged at the C terminus was prepared as described previously (1) with the following modifications. The purification was conducted using 100 mm HEPES (pH 7.0) and 10% glycerol (Buffer A). Following nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid column chromatography, MMACHC-containing fractions were pooled, and 10 mm dithiothreitol was added. The concentrated protein was then loaded onto a Superdex 200 column (1.6 × 80 cm) using Buffer A containing 150 mm KCl. MMACHC-containing fractions (>95% pure) were pooled and, if needed, stored at −80 °C after addition of EDTA-free protease inhibitor (1×; Roche Applied Science).

HPLC Analysis

The alkyl transfer reaction products were detected by HPLC following quenching of the reaction mixture with 3% ice-cold metaphosphoric acid and centrifugation to remove the precipitate. The standards were prepared in the same buffer and treated analogously. The cobalamin products were analyzed as described (21). GSH and GSH-derived thioethers were analyzed as described (22). The amino groups were derivatized with 2,4-dinitrofluorobenzene following reaction of free thiols with monoiodoacetic acid and injected onto a μBondapakTM NH2 column (3.9 × 300 mm, Waters) equilibrated with 4:1 (v/v) methanol/H2O. The column was eluted as described (21), and the eluant was monitored at 340 nm.

Liquid Chromatography-Electrospray Ionization-Mass Spectrometry (MS) Analysis

Reaction mixtures were lyophilized and resuspended in 120 μl of water. The samples were separated on a Synergi Hydro-RP C18 HPLC column (4 μm) with polar end capping (Phenomenex) and eluted isocratically with 0.1% formic acid/acetonitrile at a 99:1 ratio for 30 min. This step was designed to eliminate the glycerol, KCl, and HEPES buffer that were originally present in the reaction mixtures and interfered with the MS analysis. They eluted in the void volume. GSH, GSSG, and methylglutathione in the reaction mixtures co-migrated with commercially available standards (Sigma). The retention times under these conditions were as follows: GSH, 4.14 min; methylglutathione, 7.07 min; and GSSG, 10.3 min. A peak with a retention time of ∼8.9 min was tentatively identified as 5′-deoxyadenosylglutathione. Fractions were collected between 3 and 15 min, dried using a SpeedVac, and resuspended in 90% MeOH/H2O for MS analysis. Liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-MS was carried out using a Thermo Finnigan triple-stage quadrupole quantum ultra mass spectrometer (Thermo Electron Corp., Waltham, MA). Each sample was dissolved in 90% MeOH and 10% H2O and infused at a rate of 0.3 μl/min. Identification of the products was carried out by detection of the parent ion peaks and comparison with commercial standards, when available.

Dealkylation Kinetics

The reaction mixture (200-μl total volume) contained 60 μm MMACHC and 40 μm alkylcobalamin in 100 mm HEPES (pH 8.0), 150 mm KCl, and 10% glycerol in the dark under aerobic conditions at 20 °C. The reaction was started by addition of 1 mm GSH. The formation of aquocobalamin (OH2Cbl) was followed at 355 nm (Δϵ = 11 cm−1 mm−1), and the dealkylation activity of MMACHC was determined from the initial slope. The kinetic parameters Vmax and Km for dealkylation of MeCbl were determined using 5 μm MMACHC, 40 μm MeCbl, and varying concentrations of GSH. The data were fitted to the Michaelis-Menten equation, where v = Vmax × [GSH]/(Km(GSH) + [GSH]).

Synthesis and Purification of [57Co]MeCbl

[57Co]MeCbl was synthesized by the reaction of cob(I)alamin with methyl iodide (Sigma) using a dim red light under anaerobic conditions as described previously (2).

Cell Culture Lines and [57Co]Cobalamin Metabolic Labeling

Normal and cblC mutant fibroblasts were grown in AdvancedTM Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. Normal human skin fibroblasts were kindly provided by the Cell Culture Core of the Department of Cell Biology, Lerner Research Institute, as described previously (2). David Rosenblatt (McGill University) kindly provided human cblC mutant skin fibroblasts from patients with severe disease (WG1801, WG2176, and WG3354). For [57Co]cobalamin metabolic labeling experiments, cells were passaged at a ratio of 1:2. [57Co]MeCbl was added to achieve a final concentration of 0.125 nm (specific activity of 379 μCi/μg). After 48 h, cells were harvested, total cobalamins were extracted with 80% aqueous ethanol, and the intracellular cobalamin profile was determined as described (2). The cell cultures were protected from light at all times to prevent photolysis of MeCbl.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Dealkylation of MeCbl by MMACHC

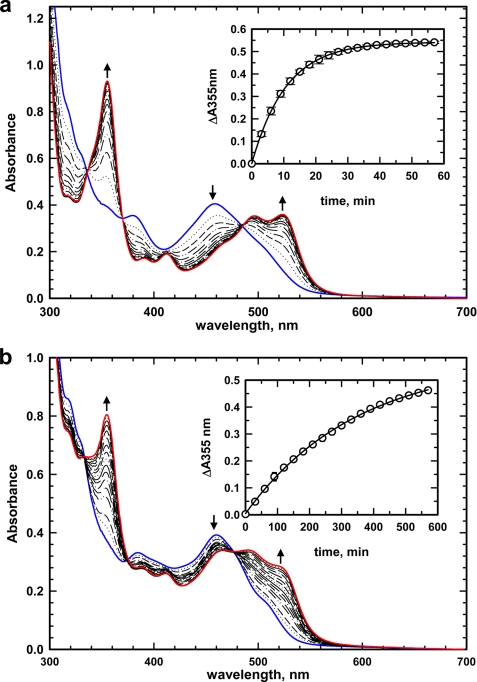

Binding of MeCbl or AdoCbl to MMACHC elicited a diagnostic “base-off” spectrum with an absorption maximum at 460 nm (Fig. 2). Addition of GSH to MMACHC·MeCbl under aerobic conditions resulted in the formation of OH2Cbl as revealed by the appearance of the characteristic spectral features at 355 and 525 nm (Fig. 2a). A concomitant decrease in absorption at 460 nm was observed with isosbestic points at 337, 377, and 489 nm. From the time dependence of the absorbance change at 355 nm, a kobs = 0.2 ± 0.01 min−1 at 20 °C was estimated (Fig. 2a, inset). The reaction was specific for GSH, and other thiols (10 mm dithiothreitol, cysteine, and homocysteine) did not elicit any changes in the MeCbl absorption spectrum under the same conditions (data not shown). The dependence of the demethylase activity of MMACHC on GSH concentration was determined in the presence of MeCbl under aerobic conditions and yielded a value for Km(GSH) of 27.7 ± 3.9 μm. The dissociation constant for binding of GSH to MMACHC was determined to be 30 ± 1 μm by isothermal titration calorimetry (data not shown).

FIGURE 2.

Dealkylation of MeCbl and AdoCbl bound to MMACHC under aerobic conditions. Shown are the spectra of MMACHC·MeCbl (60:40 μm; blue trace in a) and MMACHC·AdoCbl (60:40 μm; blue trace in b) in aerobic 100 mm HEPES (pH 8.0) containing 150 mm KCl and 10% glycerol. Addition of GSH (1 mm) resulted in the spectral changes that are consistent with formation of OH2Cbl. Insets show the absorbance increases at 355 nm (○) at 20 °C and the single exponential fits to the data (solid line).

Dealkylation of MeCbl by MMACHC to form OH2Cbl in the cellular milieu explains why therapeutic MeCbl for cblE and cblG patients, who are specifically impaired in the cytoplasmic pathway for MeCbl synthesis, is unlikely to be effective. This was first suggested by Hall and co-workers (6) based on their observation that, once internalized, both MeCbl and OH2Cbl are converted in similar proportion to the active coenzyme forms, i.e. AdoCbl and MeCbl, supporting the processing strategy involving a common intermediate shown in Fig. 1.

Dealkylation of AdoCbl by MMACHC

The reaction of MMACHC·AdoCbl with GSH (Fig. 2b) shows an increase in absorption at 355 and 525 nm with a concomitant decrease at 460 nm. The kobs for this reaction monitored at 355 nm is 0.003 ± 0.0001 min−1 at 20 °C (Fig. 2b, inset) and is ∼67-fold slower than the rate observed with MeCbl. Dealkylation of AdoCbl by MMACHC poses a potential limitation for AdoCbl therapy for patients who are specifically impaired in the mitochondrial pathway for AdoCbl synthesis, i.e. those belonging to the cblA and cblB groups.

Mechanism of MMACHC-catalyzed Dealkylation

In principle, the cleavage of the cobalt–carbon bond in alkylcobalamins can occur via a homolytic or heterolytic mechanism, leading to cob(II)alamin and cob(I)alamin, respectively (Scheme 1, Reactions 2 and 3). The fates of the alkyl groups are also distinct, i.e. formation of an organic radical in the case of Reaction 2 and an alkylated nucleophile in Reaction 3. Based on product analyses described below, the MMACHC-catalyzed dealkylation is consistent with a nucleophilic displacement reaction as described by Equation 1,

|

in which the thiolate anion attacks the alkyl group, resulting in heterolytic cleavage of the cobalt–carbon bond and formation of cob(I)alamin and a thioether product. Under aerobic conditions, oxidation of the highly reactive cob(I)alamin product to cob(II)alamin and then to OH2Cbl is expected and is consistent with the electronic absorption spectral changes that are seen (Fig. 2).

Identification of Dealkylation Products

The identity of OH2Cbl formed during dealkylation of either MeCbl or AdoCbl was confirmed by analytical HPLC (Fig. 3a). Complete conversion of MeCbl to OH2Cbl was observed in contrast to partial conversion of AdoCbl to OH2Cbl. The slower rate of reaction with AdoCbl combined with the instability of MMACHC at 20 °C during prolonged incubation likely results in the dealkylation reaction being incomplete. Two additional peaks with retention times of 9.8 and 13.4 min were observed in the reaction mixture when AdoCbl was employed (Fig. 3a, upper trace). The appearance of these peaks was dependent on the presence of both GSH and MMACHC. We tentatively assigned one of these peaks as the expected thioether product, 5′-deoxyadenosylglutathione (as confirmed by mass spectrometric analysis described below), which is expected to absorb at 255 nm. The identity of the other peak is presently not known, but it could represent 5′-deoxyadenosine.

FIGURE 3.

HPLC analysis for alkyl transfer reaction products. The HPLC traces were monitored at 255 nm for cobalamins (a) and at 340 nm for derivatized GSH thioethers (b) as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The reaction mixtures (50:70 μm in both samples) for MMACHC·AdoCbl (upper traces) and MMACHC·MeCbl (middle traces) were prepared in 100 mm HEPES (pH 8.0), 150 mm KCl, and 10% glycerol. The reaction was started with 50 μm GSH and incubated in the dark for 30 min (MMACHC·MeCbl + GSH) or overnight (MMACHC·AdoCbl + GSH) at 20 °C. The products were analyzed by HPLC as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The elution profiles of standards are shown in the lower traces. MeSG, S-methylglutathione.

To confirm that cob(I)alamin is indeed the immediate product of the alkyl transfer reaction, the latter was followed under strictly anaerobic conditions using the more reactive MeCbl substrate (Fig. 4). Upon addition of GSH, spectral changes were observed that were distinct from those seen under aerobic conditions. Thus, absorbance increases at 390, 545, and 680 nm, typical for formation of cob(I)alamin, were seen with a corresponding decrease at 460 nm. The spectral changes showed isosbestic points at 420 and 530 nm and occurred with a kobs of 0.21 ± 0.001 min−1 as monitored at 390 nm (Fig. 4, inset). The kobs for cob(I)alamin formation under anaerobic conditions is identical to that of OH2Cbl formation under aerobic conditions, indicating that the slow nucleophilic displacement reaction yielding cob(I)alamin is followed by rapid oxidation to give OH2Cbl.

FIGURE 4.

Dealkylation of MeCbl bound to MMACHC under anaerobic conditions. Addition of anaerobic GSH (50 μm) to an anaerobic solution of MMACHC·MeCbl (70:50 μm) in anaerobic 100 mm HEPES (pH 8.0) containing 150 mm KCl and 10% glycerol at 20 °C resulted in spectral changes consistent with formation of cob(I)alamin. The inset shows the increase in absorbance at 390 nm (○) for cob(I)alamin formation and the single exponential fit to the data (solid line).

The glutathionyl thioether products of the alkyl transfer reactions were identified by HPLC and MS. With MeCbl, the reaction mixture revealed almost complete conversion of glutathione to a compound with a retention time of 10.6 min that co-migrated with authentic methylglutathione (Fig. 3b). Its identity was confirmed by electrospray ionization-MS (m/z = 321) (data not shown). With AdoCbl, a new asymmetric peak eluted at 8.7 min and was tentatively assigned as 5′-deoxyadenosylglutathione. Its identity was confirmed by electrospray ionization-MS analysis (m/z = 556) (data not shown). Unreacted GSH (m/z = 306) and GSSG (m/z = 612) were also observed in these samples due to incomplete conversion to product.

Comparison of Solution- Versus MMACHC-catalyzed Dealkylation Rates

Although dealkylation of alkylcobalamins by thiols has chemical precedence (23, 24), harsh conditions, e.g. pH ≥ 9.5, high temperature, and an excess of the thiol (dithiothreitol or 2-mercaptoethanol), are needed to observe the displacement reaction. Under conditions of the MMACHC-catalyzed reactions, dealkylation of MeCbl or AdoCbl by GSH in solution was not observed even after overnight incubation (data not shown). Considering a temperature coefficient (Q10) of ∼2, i.e. the reaction rate doubles for every 10 °C rise in temperature, the transfer of a methyl group from MeCbl to the thiolate of 2-mercaptoethanol in alkaline solution is estimated to be ∼3 × 102-fold slower (kobs = 0.5 × 10−4 s−1, pH 9.5, 43 °C) than the corresponding demethylation catalyzed by MMACHC (kobs = 33 × 10−4 s−1, pH 8.0, 20 °C). The alkyl transfer rate from AdoCbl to 2-mercaptoethanol in solution is considerably slower (kobs = 0.14 × 10−4 s−1, pH 9.5, 70 °C) and is ∼103-fold slower than that catalyzed by MMACHC (kobs = 0.5 × 10−4 s−1, pH 8.0, 20 °C). These reaction rate differences are further magnified upon correcting for the pH difference, assuming a 10-fold increase in the concentration of the nucleophile for a unit increase in pH. Hence, the MMACHC-catalyzed dealkylation of MeCbl and AdoCbl is estimated to be ∼15,000- and 50,000-fold faster, respectively, than the corresponding uncatalyzed reactions. Although the proficiency of these MMACHC-catalyzed rates may be modest compared with other enzymes, we speculate that it is sufficient to meet the cellular needs for what is expected to be low flux through the vitamin B12-processing pathway.

Dealkylation of Varied Alkylcobalamins

In its postulated role as the proximal cytoplasmic acceptor of vitamin B12 exiting the lysosome (1, 11), MMACHC is predicted to exhibit a broad specificity for binding incoming cobalamin derivatives. Furthermore, a practical application of vitamin B12 is its potential use as a vehicle for delivery of drugs or fluorescent imaging probes and for targeting certain cancers (25) where the cell-surface receptor for the vitamin B12 binder transcobalamin II is overexpressed (26). Therefore, to assess the latitude that MMACHC exhibits for its alkyl substrate, we assessed the reactivity of a series of alkylcobalamins (Table 1). In the presence of GSH, MMACHC catalyzed the slow conversion of a series of alkyl derivatives, which were bound in a base-off conformation, to OH2Cbl under aerobic conditions (data not shown). Based on the observed reaction rate, the alkylcobalamins can be ordered into the following series based on decreasing reactivity: MeCbl > ethylcobalamin > AdoCbl ≈ propylcobalamin > butylcobalamin ≈ pentylcobalamin ≈ hexylcobalamin.

TABLE 1.

Comparison of rates of MMACHC-catalyzed dealkylation of alkylcobalamins

| Alkylcobalamin substituent (R) | kobsa |

|---|---|

| h−1 | |

| R-CH3 | 11.7 ± 0.2 |

| R-Ado | 0.174 ± 0.006 |

| R-CH2-CH3 | 1.86 ± 0.12 |

| R-(CH2)2-CH3 | 0.13 ± 0.01 |

| R-(CH2)3-CH3 | 0.036 ± 0.006 |

| R-(CH2)4-CH3 | 0.024 ± 0.001 |

| R-(CH2)5-CH3 | 0.022 ± 0.001 |

a Values were determined by UV-visible spectroscopy at 20 °C as described under “Experimental Procedures” and represent the mean ± S.D. of three different independent experiments.

The broad specificity of MMACHC for alkylcobalamins suggests that upon delivery of cargo conjugated at the upper axial ligand position, a naturally occurring alkyl transfer reaction might be exploited to cleave the cobalt–carbon bond. This mechanism of drug release would have advantages over photocleavage because visible light has limited tissue penetration.

Physiological Relevance of the Alkyltransferase Activity of MMACHC

Because MeCbl is the predominant form of the cofactor in circulation that is delivered to cells (6, 27), we examined its fate in fibroblasts from normal and cblC patients. After 48 h of incubation of fibroblast cells with [57Co]MeCbl, radioactivity was observed in MeCbl, AdoCbl, and OH2Cbl (Fig. 5) in addition to a pool denoted as “others,” which likely represents side reactions of protein-bound OH2Cbl released during sample preparation with intracellular ligands and has been seen previously (2). In contrast, cblC cell lines from three patients accumulated radioactivity primarily in the MeCbl pool, albeit at significantly lower levels than in the control cell line. This is consistent with the increased efflux of cobalamins from cblC fibroblasts reported previously (28). The very low level of conversion of MeCbl to AdoCbl in all three cblC cell lines is consistent with their impaired alkyltransferase activity of MMACHC (28).

FIGURE 5.

Processing of [57Co]MeCbl by normal and cblC mutant human fibroblasts (WG1801, WG2176, and WG3354). Cells were cultured in the presence of 0.125 nm [57Co]MeCbl (0.06 μCi/ml of culture medium) for 48 h. 57Co-Labeled cobalamins were then extracted and analyzed by HPLC as described (2).

Relationship between MMACHC and the Glutathione Transferase Superfamily

The glutathione S-transferase superfamily encompasses enzymes that have resulted from both convergent and divergent evolution and are important for the detoxification of endogenous and xenobiotic electrophilic compounds (29, 30). They catalyze the general reaction shown in Equation 2.

A common mechanistic feature of these enzymes is the activation of glutathione by deprotonation, typically by an active-site serine or tyrosine residue. Using various basic local alignment search tools (BLASTP, PSI-BLAST, and PHI-BLAST), homologies between MMACHC and glutathione transferases were not identified. This suggests that MMACHC either represents a novel type of glutathione transferase or is very distantly related to one of the five subclasses whose members are cytosolic proteins.

Summary

We report the discovery that MMACHC, involved in the cobalamin-processing pathway, is an alkyltransferase and uses the abundant intracellular thiol GSH as a nucleophile. Chemically, the MMACHC-catalyzed reaction represents a hybrid of the alkyltransferase activity exhibited by the glutathione transferase superfamily of enzymes (29, 30) and the half- reaction catalyzed by cobalamin-dependent methionine synthase, in which the methyl group from MeCbl is transferred to the thiolate of homocysteine (7). However, evolutionarily, MMACHC does not appear to be a sequence relative of either enzyme class and may have arisen by convergent evolution. The relaxed specificity of MMACHC for the upper alkyl ligand of cobalamin might be therapeutically useful for delivery of drugs conjugated to vitamin B12.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants DK45776 (to R. B.) and HL71907 (to D. W. J.).

- MeCbl

- methylcobalamin

- AdoCbl

- 5′-deoxyadenosylcobalamin

- CNCbl

- cyanocobalamin

- HPLC

- high pressure liquid chromatography

- MS

- mass spectrometry

- OH2Cbl

- aquocobalamin.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kim J., Gherasim C., Banerjee R. (2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 14551–14554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hannibal L., Kim J., Brasch N. E., Wang S., Rosenblatt D. S., Banerjee R., Jacobsen D. W. (2009) Mol. Genet. Metab. 97, 260–266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banerjee R., Gherasim C., Padovani D. (2009) Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 13, 477–484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mellman I. S., Youngdahl-Turner P., Willard H. F., Rosenberg L. E. (1977) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 74, 916–920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kolhouse J. F., Allen R. H. (1977) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 74, 921–925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chu R. C., Begley J. A., Colligan P. D., Hall C. A. (1993) Metabolism 42, 315–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Banerjee R. V., Matthews R. G. (1990) FASEB J. 4, 1450–1459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gravel R. A., Mahoney M. J., Ruddle F. H., Rosenberg L. E. (1975) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 72, 3181–3185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Willard H. F., Mellman I. S., Rosenberg L. E. (1978) Am. J. Hum. Genet. 30, 1–13 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shevell M. I., Rosenblatt D. S. (1992) Can. J. Neurol. Sci. 19, 472–486 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Banerjee R. (2006) ACS Chem. Biol. 1, 149–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lerner-Ellis J. P., Tirone J. C., Pawelek P. D., Doré C., Atkinson J. L., Watkins D., Morel C. F., Fujiwara T. M., Moras E., Hosack A. R., Dunbar G. V., Antonicka H., Forgetta V., Dobson C. M., Leclerc D., Gravel R. A., Shoubridge E. A., Coulton J. W., Lepage P., Rommens J. M., Morgan K., Rosenblatt D. S. (2006) Nat. Genet. 38, 93–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosenblatt D. S., Fenton W. A. (2001) in The Metabolic & Molecular Bases of Inherited Diseases (Scriver C. R., Sly W. S. eds) pp. 3897–3933, McGraw-Hill Inc., New York [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lexa D., Saveant J. M. (1983) Acc. Chem. Res. 16, 235–243 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olteanu H., Banerjee R. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 35558–35563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paine M. J., Garner A. P., Powell D., Sibbald J., Sales M., Pratt N., Smith T., Tew D. G., Wolf C. R. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 1471–1478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bartholomew D. W., Batshaw M. L., Allen R. H., Roe C. R., Rosenblatt D., Valle D. L., Francomano C. A. (1988) J. Pediatr. 112, 32–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Andersson H. C., Shapira E. (1998) J. Pediatr. 132, 121–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martin B. D., Finke R. G. (1992) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 114, 585–592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matthews R. G. (2001) Acc. Chem. Res. 34, 681–689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Padovani D., Banerjee R. (2006) Biochemistry 45, 2951–2959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mosharov E., Cranford M. R., Banerjee R. (2000) Biochemistry 39, 13005–13011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hogenkamp H. P., Bratt G. T., Kotchevar A. T. (1987) Biochemistry 26, 4723–4727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hogenkamp H. P., Bratt G. T., Sun S. Z. (1985) Biochemistry 24, 6428–6432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gupta Y., Kohli D. V., Jain S. K. (2008) Crit. Rev. Ther. Drug Carrier Syst. 25, 347–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Amagasaki T., Green R., Jacobsen D. W. (1990) Blood 76, 1380–1386 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gimsing P., Nexø E., Hippe E. (1983) Anal. Biochem. 129, 296–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mellman I., Willard H. F., Youngdahl-Turner P., Rosenberg L. E. (1979) J. Biol. Chem. 254, 11847–11853 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Babbitt P. C. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 10298–10300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Armstrong R. N. (1997) Chem. Res. Toxicol. 10, 2–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]