Abstract

Procollagen C-proteinase enhancers (PCPE-1 and -2) specifically activate bone morphogenetic protein-1 (BMP-1) and other members of the tolloid proteinase family during C-terminal processing of fibrillar collagen precursors. PCPEs consist of two CUB domains (CUB1 and CUB2) and one NTR domain separated by one short and one long linker. It was previously shown that PCPEs can strongly interact with procollagen molecules, but the exact mechanism by which they enhance BMP-1 activity remains largely unknown. Here, we used a series of deletion mutants of PCPE-1 and two chimeric constructs with repetitions of the same CUB domain to study the role of each domain and linker. Out of all the forms tested, only those containing both CUB1 and CUB2 were capable of enhancing BMP-1 activity and binding to a mini-procollagen substrate with nanomolar affinity. Both these properties were lost by individual CUB domains, which had dissociation constants at least three orders of magnitude higher. In addition, none of the constructs tested could inhibit PCPE activity, although CUB2CUB2NTR was found to modulate BMP-1 activity through direct complex formation with the enzyme, resulting in a decreased rate of substrate processing. Finally, increasing the length of the short linker between CUB1 and CUB2 was without detrimental effect on both activity and substrate binding. These data support the conclusion that CUB1 and CUB2 bind to the procollagen substrate in a cooperative manner, involving the short linker that provides a flexible tether linking the two binding regions.

INTRODUCTION

Tolloid proteinases have been shown to play important roles during embryogenesis and tissue remodeling. They control extracellular matrix synthesis as well as morphogenetic events such as dorso-ventral patterning, neural differentiation, and muscle growth (1). This control is achieved through proteolytic modifications of several matrix components (fibrillar and non-fibrillar procollagens, small leucine-rich proteoglycans, laminin 332, perlecan, and others), enzymes (lysyl oxidases) and growth factors or associated molecules (chordin, latent transforming growth factor-β-binding protein-1, growth differentiation factors 8 and 11, prolactin, and others). In mammals, the tolloid family includes bone morphogenetic protein-1 (BMP-1),2 mammalian tolloid, and mammalian tolloid like-1 and -2 (2). BMP-1 and mammalian tolloid are also known as “procollagen C-proteinases” (PCPs), because one of their key functions is to trigger collagen fibrillogenesis through cleavage of the C-terminal propeptides in fibrillar procollagens (3). Collagen fibrils then provide a scaffold for further deposition of other matrix molecules.

Tolloid enzymes are assisted during collagen maturation by the procollagen C-proteinase enhancers-1 and -2 (PCPE-1 and -2), which can increase tolloid activity on the major fibrillar procollagens by >10-fold (4, 5) while not affecting the cleavage of other known tolloid substrates (6). PCPEs are rather small extracellular glycoproteins (∼50 kDa) consisting of, from the N to the C terminus, two CUB domains and one NTR domain. These domains are separated by two linkers: one short linker (9 amino acids in human PCPE-1) between the two CUB domains and one rather long linker (44 amino acids in human PCPE-1) between the second CUB and the NTR domain. CUB domains were originally found in proteins from the complement system, in the sea urchin protein Uegf and in BMP-1, whereas the NTR domain shares homology with the C-terminal domain of netrins whose primary role is in axonal guidance (7).

The mechanism by which PCPEs increase tolloid activity in such an efficient and specific manner is only partially understood. One major determinant of this efficiency seems to be the direct and strong interaction of PCPEs with fibrillar procollagen substrates (4, 8), whereas interaction of PCPEs with tolloid proteinases is possible but probably much weaker (9). Interestingly, the CUB domain region alone is sufficient to promote enhancement (4, 10). We have shown that the triple helix of procollagens is not required for tolloid stimulation (6) and have identified several residues in CUB1 that seem to play a major role in the PCPE-procollagen interaction (11). Of note, when the calcium-binding site in CUB1 is disrupted, interaction with the C-terminal part of procollagen III is completely abolished, locating one possible interaction site on loops 5, 7, and 9 of CUB1. One attractive hypothesis is that PCPEs actually bind to both sides of the tolloid cleavage site (located between the C-telopeptide and the C-propeptide), thereby inducing a conformational change in the procollagen molecule and facilitating procollagen C-proteinase action (8).

Here, using a series of novel constructs derived from PCPE-1 and resulting from the deletion of one or more domains or from domain-swapping, we show that although both CUBs are required for enhancement, they bind very weakly to the substrate as individual domains. Also, we show that exchanging one CUB domain for another CUB domain results in complete loss of enhancing activity and can even lead to tolloid inhibition. In contrast, increasing the length of the short linker region between CUB1 and CUB2 has no significant effect. Altogether, our present data give further insight into previously proposed mechanisms and raise new possibilities to explain PCPE action.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Molecular Biology

New DNA constructs used in this study are CUB1NTR, CUB2NTR, CUB1CUB1NTR, CUB2CUB2NTR, and PCPE+4 (Fig. 1A). CUB1NTR and CUB2NTR were produced with the QuikChange XL site-directed mutagenesis kit from Stratagene using the cDNA of human PCPE-1 inserted into the pCEP4 vector (Invitrogen), in-frame with an 8-histidine C-terminal tag (known as PCPEhis) (11). 5′-Phosphorylated primers were designed to delete residues 150–275 to obtain CUB1NTR (numbering according to human full-length PCPE-1, including the signal peptide) and residues 26–149 to obtain CUB2NTR. CUB2CUB2NTR corresponds to the insertion of residues 162–273 (CUB2) in place of residues 40–149 (CUB1). This was obtained after ligation of the 5′-phosphorylated PCR product corresponding to residues 162–273 directly in an opened PCR product resulting from deletion of the region corresponding to residues 40–149 in PCPEhis inserted in pCR-BluntII-TOPO (Invitrogen). The resulting construct was subcloned in pCEP4 using the KpnI and BamHI sites. The same procedure applied to CUB1CUB1NTR failed to yield the desired product so, instead, insertion of residues 40–149 (CUB1) in place of residues 162–273 (CUB2) was performed by addition of a SacI restriction site on the 5′-end of the fragment coding for CUB1 and a NotI site on its 3′-end. Ligation of this product in the PCPEhis+pCR-BluntII-TOPO construct, modified to accept the SacI-NotI fragment, and further subcloning in pCEP4 yielded the construct called CUB1CUB1NTR. This construct contains four additional residues (ELQF), not present in PCPE-1, at the end of the linker between the CUB1 domains. Finally, the same four additional residues were inserted after F158 in PCPEhis+pCR-BluntII-TOPO using primers overlapping in the region to be inserted with 5′-phosphorylated and 6-base floating ends. The PCR product was again ligated, transformed, and subcloned into pCEP4, resulting in the construct called PCPE+4.

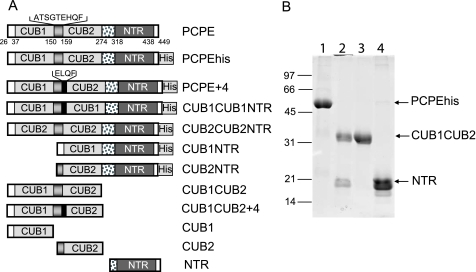

FIGURE 1.

PCPE constructs used in this study. A, schematic representation of the constructs derived from human PCPE-1 (PCPE) used in the present study. Numbers indicate first amino acid for (from left to right) N-terminal extension, CUB1, short linker, CUB2, long linker, NTR, and C-terminal extension. Inserted sequences are those of the short linker in PCPE-1 and the sequence of the insertion present in PCPE+4, CUB1CUB1NTR, and CUB1CUB2+4. His = His tag. B, SDS-PAGE showing the products of PCPEhis (lane 1) obtained after trypsinolysis (lane 2) and separation on heparin-Sepharose (lane 3, flow-through containing CUB1CUB2; lane 4, elution fraction containing NTR). The gel was run in reducing conditions (13% acrylamide) and stained with Coomassie Blue.

Protein Production, Purification, and Characterization

Human forms of mini-procollagen III, PCPE, PCPEhis, and BMP-1-FLAG were produced in 293-EBNA cells as previously described (6, 11). Similarly, the pCEP4 constructs described in the previous section were transfected in 293-EBNA cells using Lipofectamine as transfection agent. After 24 h, hygromycin B (300 μg/ml) was added to the medium, and selection was maintained for the duration of cell amplification. Protein production was performed in serum-free conditions for up to 3 weeks, and medium was collected every 2 days. Cell supernatants were clarified by centrifugation and batch purified with nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid-agarose (Qiagen, 20 ml/liter) for 3 h at 4 °C (11). The gel was then loaded into a column, and His-tagged proteins were eluted with 250 mm imidazole in 50 mm NaH2PO4, pH 8, 0.3 m NaCl. Imidazole was removed either by dialysis or by diluting protein fractions 3-fold followed by loading onto a 5-ml heparin HiTrap column (Amersham Biosciences). CUB1CUB2, CUB1CUB2+4, CUB1, CUB2, and NTR were obtained by limited proteolysis of, respectively, PCPEhis, PCPE+4, CUB1NTR, and CUB2NTR on agarose-immobilized trypsin (Sigma, ∼1 mg of protein was incubated with 500 μl of slurry for 15 min at room temperature in a total volume of 3 ml of 20 mm HEPES, pH 7.4, 0.15 m NaCl, 5 mm CaCl2). CUB-containing fragments, found in the flow-through and wash fractions, were separated from the NTR domain on a heparin HiTrap column.

N-Glycosidase F (Roche Applied Science) was used according to the manufacturer's instructions with native CUB1. Mass spectrometry and N-terminal sequencing were performed at the facility for protein microsequencing (IFR128, Gerland). Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectra were recorded on a Voyager DE-PRO (Applied Biosystems) instrument in the 2.5- to 25-kDa mass range using linear mode and external calibration. The matrix was a sinapinic acid solution (Laser BioLabs, 1 mg/100 μl in 50% CH3CN/50% H2O/0.1% trifluoroacetic acid).

CD Spectroscopy

To evaluate the folding of the PCPE-1 fragments, far UV (195–260 nm) CD measurements were carried out using thermostatted 0.2-mm path length quartz cells in an Applied Photophysics Chirascan instrument, calibrated with aqueous d-10-camphorsulfonic acid. Proteins (∼0.5 mg/ml) were analyzed at 25 °C in 10 mm Tris-HCl, 150 mm NaCl, pH 7.4, in the presence and absence of 10 mm CaCl2. Spectra were measured with a wavelength increment of 0.5 nm, integration time of 1–6 s, and bandpass of 1 nm. Protein concentrations were determined by absorbance at 280 nm using the absorbance calculated from the amino acid sequence. To calculate simulated curves for full-length PCPEhis, the observed mean residue ellipticities for the CUB1 and CUB2NTR fragments were combined after weighting according to the number of residues in each protein.

Labeling of Mini-procollagen III

Mini-procollagen III was covalently labeled with the fluorescent dye DyLight633-NHS ester (ThermoScientific) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Briefly, 100–500 μl of mini-procollagen III at 1 mg/ml in 50 mm borate buffer, pH 8.5, was transferred to a 50-μg vial of dye, and the mixture was incubated at room temperature for 1 h. Excess reagent was removed using dye-removal columns (ThermoScientific), and the labeled protein was aliquoted and stored at −80 °C in black tubes. The number of fluorescent labels per molecule of mini-procollagen III was calculated from the emission maximum (630 nm) of the dye fluorescence spectrum after coupling, according to the manufacturer's instructions. An extinction coefficient of 122 700 m−1 cm−1 was used to determine the mini-procollagen III concentration.

Activity Assays

Assays of PCPE-like enhancing activity were run in 50 mm Tris-HCl or HEPES, pH 7.4, 0.15 m NaCl, 5 mm CaCl2, and 0.02% Brij-35 for 2 h at 37 °C. Incubation volumes were 50 μl and contained 315 nm mini-procollagen III-, 8 nm BMP-1-FLAG-, and 315 nm PCPE-derived constructs. Reactions were stopped and precipitated with 1/10 (v/v) trichloroacetic acid. Pellets were boiled in 8 m urea for 5 min before addition of sample buffer and analysis by SDS-PAGE. Competition experiments, including PCPEhis and the various constructs, were run in a similar way except that the total volume was 100 μl and 2.5 nm BMP-1-FLAG, 160 nm mini-procollagen III, 120 nm PCPE, and 800 nm constructs were used.

When fluorescent mini-procollagen III was used as a substrate, the incubation volume was 20 μl and contained 140 nm mini-procollagen III, 12 nm BMP-1-FLAG, and various concentrations of CUB2CUB2NTR. After 1 h at 37 °C and addition of 10 μl of Laemmli buffer, samples were boiled for 5 min at 100 °C and loaded onto a 7.5% acrylamide precast gel (Bio-Rad). Protein bands were analyzed with a fluorescent gel reader (STORM 860, Molecular Dynamics) using the red laser excitation at 630 nm and ImageQuant 5.2 for quantitation.

Experiments using the BMP-1 fluorescent peptide (Mca-YVADAPK(Dnp)-OH, Bachem) were run in a microtiter plate using 20 μm peptide, 36 nm BMP-1-FLAG in 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 0.15 m NaCl, 5 mm CaCl2, and 0.02% octylglucoside (final volume of 100 μl). Excitation and emission wavelengths were set at 320 and 405 nm, and changes in fluorescence were monitored over time in a TECAN fluorometer for 30 min at 37 °C.

Interaction Studies

Surface plasmon resonance experiments were done with a Biacore T100 (Amersham Biosciences) at the protein production and analysis facility of the IFR128. Mini-procollagen III was immobilized on a CM5 sensorchip (series S, non-certified) using amine-coupling chemistry as previously described (11). The control channel was prepared with the same activation/deactivation procedure except that the mini-procollagen III solution was replaced by 10 mm sodium acetate buffer, pH 5. Prior to injection, proteins were dialyzed against HBS (10 mm HEPES, pH 7.4, 0.15 m NaCl) containing 5 mm CaCl2, which was also used as running buffer after addition of 0.05% P-20. Sensorgrams were recorded at 25 °C with a flow rate of 30 μl/min. Regeneration of active and control channels was performed with sequential injections of 0.5 m EDTA and 2 m guanidinium chloride. Double referencing (subtraction of the sensorgram obtained on the control channel then subtraction of a sensorgram obtained with buffer alone) was used to analyze kinetic experiments, which were fitted using Biacore T100 Evaluation software 2.0.1.

For the ELISA experiments, mini-procollagen III or BMP-1 (10 μg/ml) was coated on Immulon 4HBX (Thermo) microtiter plates overnight at 4 °C. Wells were then blocked with 5% (w/v) dried milk in TBS (10 mm Tris, pH 7.4, 0.15 m NaCl) for 1.5 h at room temperature. After washing three times with TBS, increasing concentrations of PCPE constructs in TBS plus 5 mm CaCl2 were added for 2 h at room temperature. Wells were again washed with TBS, and a polyclonal antibody directed against full-length human PCPE-1 (6) was added for 1 h. Secondary antibody was goat anti-rabbit coupled to horseradish peroxidase (Bio-Rad), used at a dilution of 1:3000, with 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzthiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) ammonium salt (Sigma) as substrate. Color development was measured at 405 nm after 10 min, in a microtiter plate reader (Dynex Technologies). Each measurement was done in triplicate, and values of the blank (TBS with no PCPE construct) wells were subtracted. Dissociation constants were obtained using KaleidaGraph software from the hyperbolic equation, A405 nm = A0[ligand]/(KD + [ligand]), where KD and A0 are set as variables with A0 corresponding to the maximum absorbance for each ligand studied.

Analysis of Short Linker Flexibility

The model for CUB1 was as previously described (11). The model for CUB2 was obtained by comparative homology modeling using the structure of the CUB domain of human neuropilin-2 (PDB code 2QQO) (12) as template (sequence identity 35%). Sequences were aligned using ClustalW2 and refined manually. Based on this alignment, the program Modeler (13) was used to generate a three-dimensional representation of CUB2. The structure of the NTR domain was already known (14) (PDB code 1UAP). BUNCH software (part of the ATSAS package, available on-line) was used to generate models, including linkers, from the small angle x-ray scattering curve of PCPE-1 obtained previously (15). Finally, PyMOL software (available on-line) served to superimpose the models and root-mean square deviations were calculated with LSQMAN (16).

RESULTS

Production and Characterization of PCPE Constructs

Since the discovery of PCPE-1 by Adar and co-workers, it is known that proteolytic fragments of PCPE-1, encompassing the CUB1 and CUB2 domains (Fig. 1A), retain an enhancing activity that seems similar to the activity of the full-length molecule (4, 17). In the present study, we produced and purified nine recombinant proteins derived from human PCPE-1 or its His-tagged version to precisely analyze the role of each domain and determine which combinations of domains result in enhancing activity. These constructs are described in Fig. 1A and include: (i) shorter proteins, for which one CUB domain has been deleted (CUB1NTR and CUB2NTR), (ii) chimeric proteins with contiguous repetitions of the same domain (CUB1CUB1NTR and CUB2CUB2NTR), and (iii) a slightly longer protein where four amino acids were inserted just before the beginning of the CUB2 domain yielding a longer linker region between CUB1 and CUB2 (PCPE+4). The inserted sequence was ELQF to resemble a sequence already found in the linker (Fig. 1A) and to serve as a control for CUB1CUB1NTR, in which this sequence was also inserted for cloning purposes.

Attempts to produce CUB1, CUB2, or CUB1CUB2 in 293-EBNA cells yielded very low amounts of protein compared with the amounts obtained with other constructs, suggesting that the NTR domain was required for proper folding or secretion. To circumvent this problem, another approach was chosen that consisted of submitting PCPEhis, PCPE+4, CUB1NTR, and CUB2NTR to limited proteolysis, then separating fragments on heparin-Sepharose. Complete cleavage of the parent proteins was obtained after incubation with trypsin-agarose for 15 min (Fig. 1B, lanes 1 and 2). Cleavage occurred mainly in the long linker preceding the NTR domain but at several sites yielding three major fragments on a SDS-PAGE 13% gel (Fig. 1B, lanes 3 and 4). The two fragments retained on heparin-Sepharose (lane 4) correspond to the NTR domain starting in the linker at serine 300 or threonine 306 (numbering for full-length PCPE-1, including the signal peptide), as determined by N-terminal sequencing. A longer fragment resulting from incomplete cleavage could also be detected in some preparations, starting at valine 294.

The fragments that were not retained on the heparin column were more homogeneous and corresponded to CUB1, CUB2, CUB1CUB2, or CUB1CUB2+4 depending on the starting material. For CUB2, we determined using mass spectrometry that the molecular mass of the fragment was 13,984 Da for a calculated average mass of 13,981 Da with CUB2 starting at alanine 150, ending at lysine 279, and containing two disulfide bridges. CUB1 was first deglycosylated with N-glycosidase F and then submitted to the same analysis, yielding a molecular mass of 13,845 Da. This mass was in good agreement with a fragment starting at glutamine 26 and ending after the end of CUB1 (corresponding to arginine 149) with the sequence WYSGR149GTAK, including four residues from the linker (theoretical molecular mass of 13,848 Da, if the first glutamine is modified to pyroglutamate and taking into account two disulfide bridges). Finally, CUB1CUB2 and CUB1CUB2+4 were assumed to start like full-length PCPE at glutamine 26 and to end at lysine 279 like CUB2 (with four additional residues in the linker for CUB1CUB2+4). All the purified proteins are shown in reduced and non-reduced forms in supplemental Fig. S1.

To determine whether the fragments were well folded, we carried out CD spectroscopy. As shown in supplemental Fig. S2A, the simulated spectrum for full-length PCPEhis, calculated from the observed spectra for the CUB1 and CUB2NTR fragments, was almost identical to the observed spectrum for PCPEhis, suggesting that the folding of the fragments was similar to the intact protein. Furthermore, the spectrum of the intact CUB2NTR fragment was unchanged after limited proteolysis with immobilized trypsin (supplemental Fig. S2B), showing that separation of the CUB2 and NTR domains had no effect on their folding. The presence or absence of calcium also had no effect on the observed spectra.

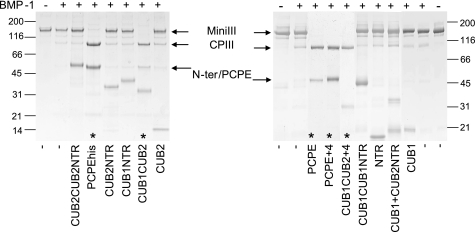

Only PCPE-1, CUB1CUB2, PCPE+4, and CUB1CUB2+4 Have Enhancing Activity

We first checked if the recombinant CUB1CUB2 protein was capable of enhancing BMP-1 activity, as would be expected from previous reports using proteolytic fragments of mouse PCPE-1 (4, 10). When a model substrate composed of a c-Myc tag, a short triple helix including the last 33 triplets, the C-telopeptide, and the C-propeptide of procollagen III was used as a substrate (mini-procollagen III (6)), we observed that CUB1CUB2 induced a total conversion of the substrate by BMP-1, similarly to PCPE and PCPEhis (Fig. 2). In this assay, the molar ratio of enhancer over substrate was 1:1. In contrast, when mini-procollagen III was incubated with BMP-1 in the presence of other constructs, including CUB1, CUB2, NTR, CUB1NTR, CUB2NTR, CUB1CUB1NTR, and CUB2CUB2NTR (Fig. 2), no visible enhancing effect was observed. Importantly, when an equimolar mixture of CUB1 and CUB2NTR was added, the PCPE-like activity could not be reconstituted indicating that the short linker between the two CUB domains plays a crucial role. However, modifying this region by insertion of four additional amino acids, as in PCPE+4 and CUB1CUB2+4, did not lead to significant changes in the enhancing activity of PCPEhis. This result also shows that this additional sequence, which was also introduced in CUB1CUB1NTR for cloning purposes, is not responsible for the loss of enhancing activity observed with the latter construct. Altogether, these experiments clearly indicate that: (i) the two contiguous CUB domains are required for the stimulation of BMP-1, (ii) these CUB domains cannot be exchanged, and (iii) even though the short linker between the two CUB domains is absolutely required, some flexibility is still permitted within this region.

FIGURE 2.

Enhancing effects of PCPE constructs on BMP-1 activity. Samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE on 4–20% gradient gels stained with Coomassie Blue under non-reducing conditions. The molar ratio mini-procollagen III/construct was 1/1. Asterisks indicate lanes where an enhancing effect of the tested construct on mini-procollagen III processing by BMP-1 can be seen. MiniIII, mini-procollagen III; CPIII, C-propeptide III; and N-ter, N-terminal cleavage product.

PCPE-1 Domains Are Inefficient Competitors of PCPE-1

For a better understanding of why most of the PCPE constructs lost enhancing activity, we then searched to determine how their interactions with the substrate were modified. The first experiment was a competition assay where CUB-containing constructs were assessed for their ability to inhibit enhancement by PCPE-1. In all cases, a 6.6 molar excess of construct compared with PCPEhis was used. In these conditions, CUB2CUB2NTR was the only protein for which a significant reduction in the amount of C-propeptide formed could be observed (Fig. 3). In another experiment, BMP-1 alone was assayed in the presence of mini-procollagen III and CUB2CUB2NTR, and we observed that CUB2CUB2NTR also decreased substrate processing in this case (data not shown). This result suggested that CUB2CUB2NTR inhibited BMP-1 through a direct effect rather than through competition with PCPE. Unexpectedly, our preliminary experiments also seemed to indicate that, although partial inhibition could be detected in the presence of 10 nm CUB2CUB2NTR, BMP-1 retained some activity even at very high concentrations of the construct (up to 2 μm).

FIGURE 3.

Competition between PCPE and non-enhancing constructs. Samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE on 8% acrylamide gels stained with Coomassie Blue under non-reducing conditions. The molar ratio mini-procollagen III/PCPE/construct was 1/0.75/5. MiniIII, mini-procollagen III; CPIII, C-propeptide III; and N-ter, N-terminal cleavage product.

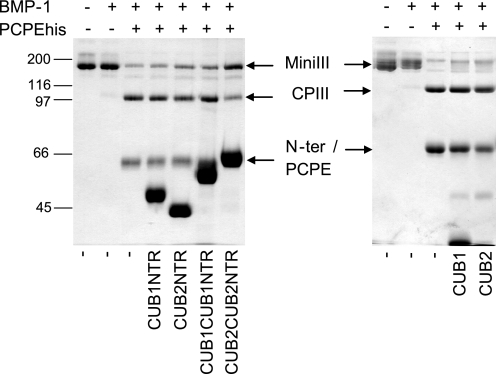

To better quantify BMP-1 activity in the presence and absence of CUB2CUB2NTR, we decided to develop a new quantitative and non-radioactive assay. We thus labeled recombinant mini-procollagen III with the fluorescent dye DyLight633 from ThermoScientific, a fast and easy procedure that targets free amines (N terminus and lysines; see “Experimental Procedures” for details). When 50 μg of labeling reagent was mixed with a 1 mg/ml solution of mini-procollagen III, we calculated that between 1.3 and 2 molecules of label had reacted with mini-procollagen III. This labeled substrate could still be cleaved by BMP-1, and this cleavage was enhanced by PCPE-1, as shown in Fig. 4A. Both cleavage products could be separated on a gel and quantified on a gel scanner equipped with a red laser. Of note, the N-terminal product, including the triple helix and the C-telopeptide, gave a weaker signal than the C-propeptide (Fig. 4A), in agreement with a smaller number of potential reactive sites (5 compared with 19). The plot of measured mini-procollagen III fluorescence intensity versus the amount of protein was found to be linear up to 500 ng of protein loaded per well (data not shown).

FIGURE 4.

Inhibition of BMP-1 by CUB2CUB2NTR. A, cleavage of fluorescent mini-procollagen III in the presence and absence of enhancer. MiniIII, mini-procollagen III; CPIII, C-propeptide III; and N-ter, N-terminal cleavage product. B, BMP-1 activity on fluorescent mini-procollagen III (diamonds) and on a fluorescent peptide, plotted as a function of CUB2CUB2NTR (circles) or PCPEhis (triangles) concentration (means ± S.D. values of three experiments). For mini-procollagen III, quantitation of products and substrate was done with a STORM 860 gel scanner. For the fluorescent peptide, the increase in fluorescence upon BMP-1 cleavage was measured using a TECAN fluorometer.

Using increasing concentrations of CUB2CUB2NTR (10–500 nm) with fixed concentrations of fluorescent mini-procollagen III and BMP-1, we confirmed that CUB2CUB2NTR was a BMP-1 inhibitor, but that maximum inhibition was only 40% even when enzyme was saturated with inhibitor (above 100 nm (Fig. 4B)). Such a partial inhibition is usually referred to as “hyperbolic inhibition” because apparent Michaelis parameters depend on inhibitor concentration both in the numerator and denominator (18). It implies that the enzyme-inhibitor complex is still active, unlike “linear inhibition” modes where formation of the enzyme-inhibitor complex is a dead-end but has a slower catalytic constant than the free enzyme (19). Interestingly, when a fluorogenic peptide was used as a substrate (20), a similar behavior was obtained with CUB2CUB2NTR, whereas PCPEhis seemed to have no effect on the peptide (Fig. 4B). As a consequence, CUB2CUB2NTR appears to be a general modulator of BMP-1 activity. Although a thorough kinetic analysis of BMP-1 inhibition by CUB2CUB2NTR was beyond the scope of this report, we did determine the dissociation constant of the BMP-1-CUB2CUB2NTR complex by ELISA and found it to be 56 ± 17 nm (data not shown).

PCPE-1 Domains Bind Cooperatively to Mini-procollagen III

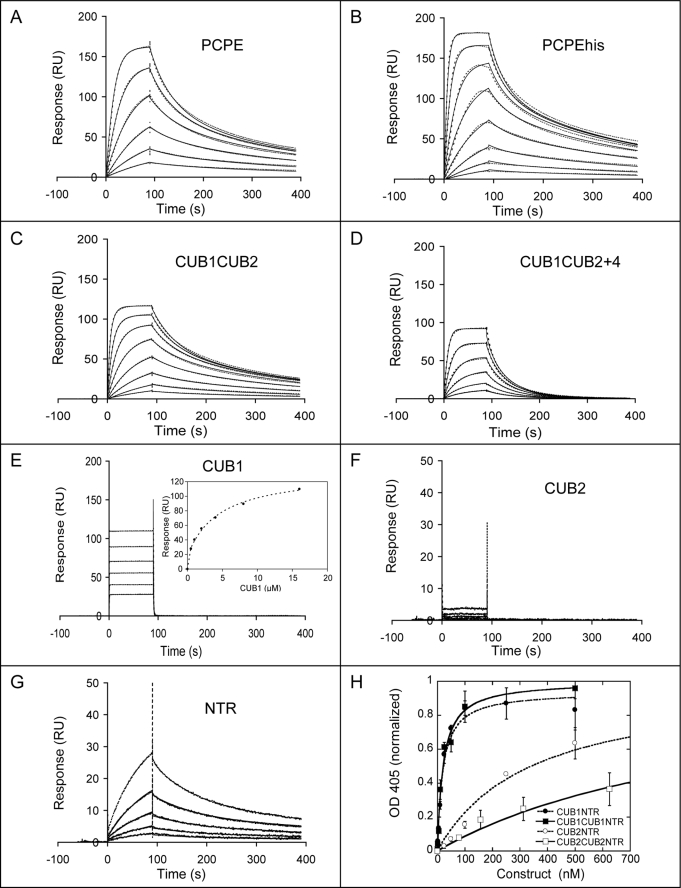

In the last part of this study, we determined dissociation constants for all constructs and mini-procollagen III. The first technique used was surface plasmon resonance on a Biacore T100 apparatus. Mini-procollagen III was covalently coupled to a CM5 sensor chip, and the various PCPE constructs were injected in a buffer containing 5 mm calcium, the concentration used in the activity assays. All constructs were found to interact with mini-procollagen III, but the concentrations required varied over more than four orders of magnitude. When we compared PCPE and PCPEhis (Fig. 5, A and B), it also appeared that the His tag present on several of our constructs could impair the quality of the recorded sensorgrams during the association phase, a phenomenon that was not observed previously on a Biacore 3000 in the absence of calcium (11). This effect was diminished when decreased flow rates and concentrations were used or when measurements were made in the absence of calcium, but it precluded reliable kinetic analysis of the binding curves. For this reason and because kinetic association and dissociation constants were not required for this study, we decided to use ELISA in parallel to assess dissociation constants of His-tagged constructs.

FIGURE 5.

Interaction studies of PCPE constructs with mini-procollagen III. A–G, representative sets of curves obtained with a Biacore T100 apparatus when injecting various PCPE constructs at a flow rate of 30 μl/min for 90 s on immobilized mini-procollagen III (500–700 resonance units (RU) immobilized). Dotted lines represent experimental curves obtained when injecting increasing concentrations (prepared as successive 2-fold dilutions of the highest concentration) of the following proteins: A, PCPE 0.39–12.5 nm; B, PCPEhis 0.39–50 nm; C, CUB1CUB2 0.39–50 nm; D, CUB1CUB2+4 0.78–25 nm; E, CUB1 0.5–16 μm; F, CUB2 1.12–20 μm; and G, NTR 0.12–2 μm. Fits are shown as solid lines and were obtained with the Biacore T100 Evaluation software 2.0.1. Inset in panel E shows steady-state analysis of the CUB1 curves. H, plots of representative curves obtained in the ELISA experiments for CUB1NTR, CUB1CUB1NTR, CUB2NTR, and CUB2CUB2NTR. For clarity, the concentration range chosen for the graph was 0–700 nm. Hyperbolic fits are also shown, and mean values of KD values calculated from three similar experiments are given in Table 1.

Comparison of the two techniques in the case of PCPE and CUB1CUB2 gave values that fell in the same range (Table 1). However, the Biacore curves are more informative and can reveal more subtle effects such as the presence of two binding sites. In the present case, curves for PCPE and CUB1CUB2 (Fig. 5, A and C) were best fitted with the heterogeneous ligand model assuming that there are two possible binding sites on mini-procollagen III. Two constants were thus derived, one around 0.4 nm and one around 8 nm (Table 1). The constants for PCPE were significantly lower than those previously determined for PCPEhis and mini-procollagen III (1.8 and 48 nm (11)), and this is explained by the addition of calcium in the present experiments, which significantly strengthens the interactions. Importantly, we also conclude from this that CUB1CUB2 binds to mini-procollagen III with dissociation constants similar to those for PCPE.

TABLE 1.

Dissociation constants of PCPE constructs for mini-procollagen III determined by Biacore or ELISA

Means of three independent experiments (with different surfaces for Biacore) ± S.D. For the Biacore studies of PCPE and CUB1CUB2, the best fits were obtained with the “heterogeneous ligand” model (values in parentheses show the mean contribution of each interaction site expressed as a percentage of the total signal); for CUB1CUB2+4 and NTR, the best model was “1:1 binding” and for CUB1 and CUB2, the KD values were obtained from the steady-state responses plotted against CUB concentrations. χ2 values were all <3.6. Representative curves and fits are shown in Fig. 5.

|

Kd |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCPE | CUB1CUB2 | CUB1CUB2+4 | CUB1 | CUB2 | NTR | ||

| nm | |||||||

| Biacore | 0.33 ± 0.10 (47%) 7.3 ± 2.4 (53%) | 0.54 ± 0.18 (61%) 9.1 ± 3.4 (39%) | 5.6 ± 0.7 | 7800 ± 4300 | >10,000 | 770 ± 480 | |

| ELISA | 1.5 ± 0.5 | 2.2 ± 0.6 | NDa | ND | ND | ND | |

| PCPEhis | CUB1NTR | CUB2NTR | CUB1CUB1NTR | CUB2CUB2NTR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nm | |||||

| Biacore | NF | NF | NF | NF | NF |

| ELISA | 1.1 ± 0.6 | 26 ± 9 | 220 ± 90 | 37 ± 18 | 790 ± 280 |

a ND, not done; NF, curves could not be fitted with available models.

To further assess the consequences of lengthening the linker between the two CUB domains, we also used CUB1CUB2+4, prepared from PCPE+4 by limited proteolysis, for Biacore analysis (Fig. 5D). In these conditions, we found a unique KD of 5.6 ± 0.7 nm, which is comparable to the higher of the two KD values found for CUB1CUB2 and PCPE. The addition of four residues in CUB1CUB2 seemed to prevent binding of the protein to the higher affinity site but did not modify the lower affinity site. Because PCPE+4 and CUB1CUB2+4 were found to be as active as PCPE and CUB1CUB2 in the conditions used, this would suggest that the high affinity site does not play a major role in the enhancing activity of the proteins studied.

Unexpectedly, individual CUB1 and CUB2 domains were found to bind to mini-procollagen III with very high dissociation constants (7.8 μm for CUB1 and even higher for CUB2 (Fig. 5, E and F, and Table 1)). Both the association and dissociation kinetics were actually very fast for the two constructs, and because they were out of the Biacore specifications, we used a steady-state analysis to determine KD values. Even in this case, saturation was difficult to reach in a reasonable concentration range, and it was only for CUB1 that a KD could be derived (inset in Fig. 5E). Noteworthy, using less detergent (0.005% instead of 0.05% P20) in the running buffer of the Biacore experiments, a significant improvement of the signal obtained with CUB2 was observed (reaching 30–50 resonance units at 10 μm for 700 resonance units of immobilized mini-procollagen III). This shows that CUB2 can also bind mini-procollagen III but much more weakly than other constructs. The fact that the dissociation constants for CUB1 and CUB2 were at least 103-fold higher than the values found for CUB1CUB2 is probably the most striking of all and clearly suggests that CUB1 and CUB2 bind to the procollagen substrate in a cooperative manner. This confirms that CUB1 and CUB2 cannot be efficient competitors of PCPE, as described in the previous section. Interestingly, the NTR domain which, from previous results, is not expected to play a role in the mechanism of action of PCPE, interacted with mini-procollagen III with a lower KD (0.77 μm) than the individual CUB domains, which are essential for activity. From the ELISA experiments, we can also deduce that CUBNTR constructs show significant improvements in their affinities for mini-procollagen III compared with single domain constructs (Fig. 5H and Table 1). The CUB1NTR construct, which brings together two normally distant domains, had a surprisingly high affinity for the substrate with a KD of 26 ± 9 nm. Addition of a third domain to the CUBNTR constructs had only a weak effect on the interaction with mini-procollagen III and even seemed detrimental in the case of CUB2CUB2NTR compared with CUB2NTR. Moreover, the KD of CUB2CUB2NTR for mini-procollagen III was much higher than the concentration required for maximum inhibition of BMP-1 (see above). This gives strength to the hypothesis that this construct hinders cleavage of substrate by BMP-1 through a direct interaction with the enzyme rather than through an interaction with the substrate, as was first expected.

DISCUSSION

Extracellular proteases are known to be regulated by a complex “arsenal” of endogenous inhibitors (e.g. serpins for serines proteases, cystatins for cathepsins, tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases for extracellular metalloproteases). Mammalian tolloid proteinases are rather unique among extracellular proteases in that their action seems to be modulated mainly by enhancers rather than inhibitors (21). In addition to PCPEs, other tolloid enhancers include twisted gastrulation and olfactomedin, both of which seem to specifically enhance cleavage of chordin, the BMP antagonist involved in dorso-ventral patterning (22, 23) and secreted frizzled related protein-2, another enhancer of procollagen C-proteinase activity (24). Strikingly, all the tolloid enhancers reported to date have the property of targeting cleavage of either chordin or fibrillar procollagens and thus working in a substrate-specific manner. The use of such substrate-specific enhancers could actually be a powerful mechanism to direct protease activity toward one particular substrate, for which there is a crucial need in some circumstances (e.g. development and wound healing) or which is required in especially high amounts, like fibrillar collagens. In this context, a better understanding of how PCPEs exert their activity may help to obtain new insights into how specificity and efficiency are achieved by these tolloid enhancers.

In this report, we show that the minimal enhancing unit in PCPE-1 is CUB1CUB2 and that shorter constructs can neither promote BMP-1 stimulation nor bind efficiently to the substrate, a normal property of the PCPEs. We have also observed that CUB1 has a higher affinity for the model substrate mini-procollagen III than CUB2 for which no significant interaction was observed in the conditions used. The same observation was made with CUB1NTR compared with CUB2NTR and for CUB1CUB1NTR compared with CUB2CUB2NTR. The important role of CUB1 was already suspected from our previous results showing that single point mutations in CUB1 are sufficient to abolish PCPE-1 activity (11). The present study unravels two other important aspects of the mechanism of action of PCPE, which could not be predicted from previous studies: (i) the strong cooperativity between CUB1 and CUB2 and (ii) the major role played by the short linker region between the two CUB domains.

Concerning the short linker, it could have been hypothesized that its role was to impose a precise geometry to the CUB1CUB2 association to provide a matching surface for interaction with the procollagen molecule. This could have explained the striking improvement in the dissociation constants in CUB1CUB2 compared with isolated CUB1 and CUB2. However, the constructs that have four additional residues in the linker region, PCPE+4 and CUB1CUB2+4, seem to efficiently enhance mini-procollagen III processing and only show a subtle modification to the dissociation constants, arguing against the rigid geometry model. On the other hand, when CUB1 and CUB2NTR are mixed, enhancing activity is not reconstituted, suggesting that freely independent CUB domains have insufficient affinities to bind to their respective binding sites in the appropriate synchronized manner. This is borne out by the experimentally determined affinities of the isolated CUB domains. We can conclude from these data that, rather than dictating a precise geometry for interaction with procollagen, the role of the short linker is to increase the rate of association of the second CUB domain once the first CUB domain is bound. As discussed above, it is likely that the first CUB domain to bind is CUB1.

This situation is reminiscent of the phenomenon of avidity observed typically for binding of a bivalent IgG antibody to its immobilized antigen: even though the affinities for individual antigen binding sites are identical, binding to the second site is faster once the first binding site is occupied. Similarly, both binding sites must release at the same time in order for the antibody molecule to dissociate. The effect is to increase the apparent strength of the binding. By analogy, the role of the short linker in PCPEs would be similar to that of the Fc region in an antibody molecule, to provide a flexible tether linking the two binding regions. In contrast to the antibody-antigen interaction, however, both interacting regions in PCPEs (the CUB domains) are binding to different sites on the same target molecule (procollagen), and the individual affinities are slightly different.

Other mechanisms can contribute to the strong cooperativity between the two CUB domains. For example, CUB1 could bind and induce a conformational change in the procollagen molecule that would facilitate the binding of CUB2. Alternatively, interaction of CUB1 with procollagen could create a completely new interaction surface for CUB2, with amino acids from both CUB1 and procollagen contributing. From the Biacore curves, we saw that dissociation of CUB1 from mini-procollagen III was very fast (too fast to yield reliable kinetic parameters), and even when injection times were increased up to 10 min, there was no evidence of a conformational change that would decrease the dissociation rate of the complex (data not shown). Moreover, when taken alone, these mechanisms would probably imply that a mixture of CUB1 and CUB2NTR should activate procollagen processing and this is not the case. Altogether, the avidity hypothesis seems the most attractive, but contributions from the two other mechanisms cannot be excluded.

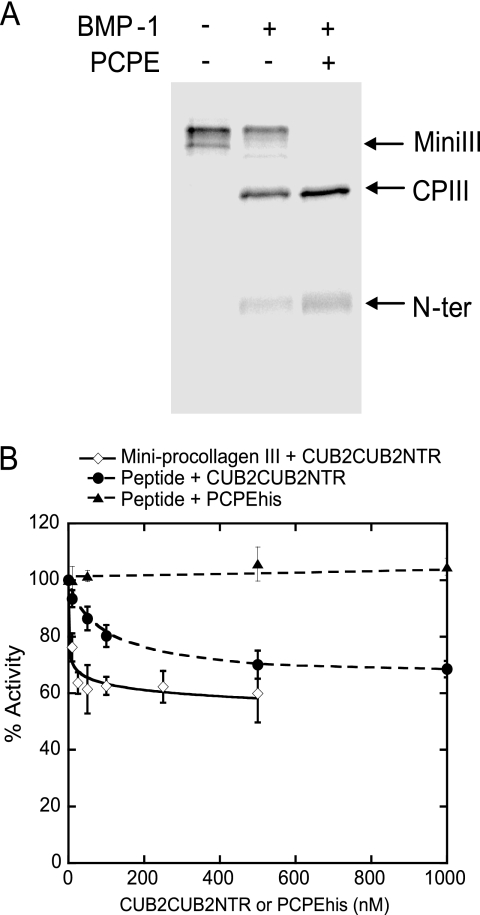

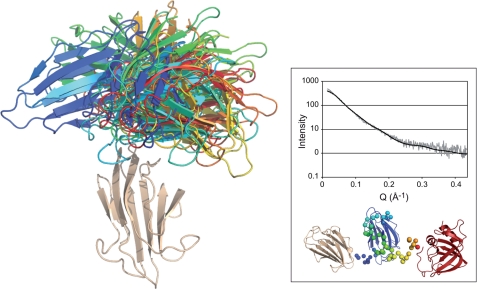

To further assess the flexibility of the linker, we calculated thirteen independent models from the previously obtained small angle X-ray scattering data for PCPE-1 (15) using BUNCH software (which was not available at the time of the earlier study). This new program allows the simultaneous determination of the optimal positions and orientations of each domain (CUB1, CUB2, and NTR) and of the probable conformations of the flexible linkers. From these calculations, it is clear that the angle between CUB1 and CUB2 can vary significantly, from approximately −90° to +90° (Fig. 6), with all configurations fitting the previously determined curve. This is also shown by the measure of the root mean square deviation between each pair of CUB2 domains, which revealed a large dispersion from 10 to 30 Å2. Thus, the CUB1 and CUB2 domains seem to be able to explore several relative orientations, and this leads us to conclude that, in solution and in the absence of a binding partner, PCPE-1 shows an inherent flexibility between its two CUB domains.

FIGURE 6.

Possible orientations of CUB1 and CUB2 based on small angle X-ray scattering data. Schematic representation, made with PyMOL, of α-carbon traces of 13 models using BUNCH, with all CUB1 domains (wheat color) superimposed. CUB2 domains are shown with a spectrum of color from blue to red. Linkers and NTR domains are not represented. The inset shows the experimental small angle X-ray scattering curve (15) and an example of a model calculated by BUNCH with the corresponding computed scattering curve. A measure of the discrepancy between the two curves is given by χ2 = 0.81. Fits for all other models were similar. From left to right: CUB1 (wheat), CUB2 (blue), and NTR (red). The linkers are represented as spheres (blue for the short linker and with a spectrum of color from pale blue to red for the long linker).

CUBNTR constructs also show some degree of cooperativity as they bind more strongly to mini-procollagen III than individual domains. Although this could be expected for CUB2NTR, which is a “natural” domain association, it was more surprising for CUB1NTR, which brings together two domains that are not contiguous in PCPE-1. This unnatural fusion does not seem to preclude interaction of each domain with its normal binding site and could even facilitate these interactions for the reasons described above. It should be noted here that the CUB1NTR linker is the same as that normally found between CUB2 and NTR in PCPE-1, a 44-residue long sequence that is predicted to be intrinsically disordered and very flexible.3 No further gain in affinity was observed in CUBCUBNTR constructs (containing identical CUB domains) compared with CUBNTR constructs. With CUB2CUB2NTR, even a decrease in affinity was observed, and this construct bound to mini-procollagen III with a dissociation constant similar to that of the NTR domain alone. However, the CUB2CUB2NTR construct, but not the NTR domain alone, was shown to modulate BMP-1 activity with a completely new mechanism. CUB2CUB2NTR does not bind mini-procollagen III very strongly but binds and inhibits BMP-1 in the same range of concentrations, suggesting that its inhibitory effect was mediated by a direct interaction with the enzyme. Despite the fact that cleavage of a small fluorescent peptide was also inhibited by CUB2CUB2NTR, it is more likely that this protein does not bind in the catalytic pocket of BMP-1, because processing remains possible at high CUB2CUB2NTR concentrations. In conclusion, we can assume that CUB2CUB2NTR binds in close proximity to the enzyme active site, thereby decreasing the reaction rate.

One negative aspect of the fact that CUB domains and CUBNTR proteins are not efficient PCPE antagonists is that these constructs cannot be used as therapeutic tools to counteract PCPE action. Because of their specificity in enhancing procollagen processing, in contrast to tolloid proteinases, which have a wide range of substrates, PCPEs would appear to be attractive targets in the prevention of fibrosis and hypertrophic scarring. PCPE antagonists could serve to slow down collagen deposition during the repair process, thereby improving the quality of the remodeled tissue. Because single domain PCPE constructs cannot be used, other therapeutic strategies will have to be investigated. Interestingly, a new approach using chimeric proteins derived from PCPEs is suggested here with CUB2CUB2NTR.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dominique Mazzocut for N-terminal sequencing, Michel Becchi and Isabelle Zanella-Cléon for mass spectrometry analysis, Yannick Tauran and Annie Chaboud for excellent Biacore maintenance, and Eve Pêcheur for technical assistance during the use of the TECAN fluorometer.

This work was supported by the Région Rhône-Alpes, the European Commission (contract NMP2-CT-2003-504017), the Agence Nationale de la Recherche, the CNRS, and the Université Claude Bernard Lyon 1.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1 and S2.

M. Bekhouche, D. Kronenberg, S. Vadon-Le Goff, C. Bijakowski, N. H. Lim, B. Font, A. Colige, H. Nagase, G. Murphy, D. J. S. Hulmes, and C. Moali, manuscript in preparation.

- BMP-1

- bone morphogenetic protein-1

- PCP

- procollagen C-proteinase

- PCPE

- PCP enhancer

- ELISA

- enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ge G., Greenspan D. S. (2006) Birth Defects Res. C. Embryo. Today 78, 47–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hopkins D. R., Keles S., Greenspan D. S. (2007) Matrix Biol. 26, 508–523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hulmes D. J. (2008) in Collagen–Structure and Mechanics (Fratzl P. ed) pp. 15–47, Springer, New York [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adar R., Kessler E., Goldberg B. (1986) Coll. Relat. Res. 6, 267–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steiglitz B. M., Keene D. R., Greenspan D. S. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 49820–49830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moali C., Font B., Ruggiero F., Eichenberger D., Rousselle P., François V., Oldberg A., Bruckner-Tuderman L., Hulmes D. J. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 24188–24194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bradford D., Cole S. J., Cooper H. M. (2009) Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 41, 487–493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ricard-Blum S., Bernocco S., Font B., Moali C., Eichenberger D., Farjanel J., Burchardt E. R., van der Rest M., Kessler E., Hulmes D. J. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 33864–33869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ge G., Zhang Y., Steiglitz B. M., Greenspan D. S. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 10786–10798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hulmes D. J., Mould A. P., Kessler E. (1997) Matrix Biol. 16, 41–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blanc G., Font B., Eichenberger D., Moreau C., Ricard-Blum S., Hulmes D. J., Moali C. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 16924–16933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Appleton B. A., Wu P., Maloney J., Yin J., Liang W. C., Stawicki S., Mortara K., Bowman K. K., Elliott J. M., Desmarais W., Bazan J. F., Bagri A., Tessier-Lavigne M., Koch A. W., Wu Y., Watts R. J., Wiesmann C. (2007) EMBO J. 26, 4902–4912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sali A., Blundell T. L. (1993) J. Mol. Biol. 234, 779–815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liepinsh E., Banyai L., Pintacuda G., Trexler M., Patthy L., Otting G. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 25982–25989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bernocco S., Steiglitz B. M., Svergun D. I., Petoukhov M. V., Ruggiero F., Ricard-Blum S., Ebel C., Geourjon C., Deleage G., Font B., Eichenberger D., Greenspan D. S., Hulmes D. J. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 7199–7205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kleywegt G. J. (1996) Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 52, 842–857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kessler E., Adar R. (1989) Eur. J. Biochem. 186, 115–121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baici A. (1981) Eur. J. Biochem. 119, 9–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cornish-Bowden A. (2004) Fundamentals of Enzyme Kinetics, 3rd Ed., Portland Press, London [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee H. X., Ambrosio A. L., Reversade B., De Robertis E. M. (2006) Cell 124, 147–159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moali C., Hulmes D. J. (2009) Eur. J. Dermatol. 19, in press [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scott I. C., Blitz I. L., Pappano W. N., Maas S. A., Cho K. W., Greenspan D. S. (2001) Nature 410, 475–478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Inomata H., Haraguchi T., Sasai Y. (2008) Cell 134, 854–865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kobayashi K., Luo M., Zhang Y., Wilkes D. C., Ge G., Grieskamp T., Yamada C., Liu T. C., Huang G., Basson C. T., Kispert A., Greenspan D. S., Sato T. N. (2009) Nat. Cell Biol. 11, 46–55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.