Autoinflation refers to the opening of the eustachian tube by blowing up a balloon with the nose, which raises intranasal pressure. Although autoinflation has been proposed for the treatment of glue ear in children it has been researched far less than surgical or pharmacological interventions, and research that has been conducted has not been reviewed systematically.

Methods and results

We searched Medline and the Cochrane Library using “otitis media,” “autoinflation,” “auto-inflation,” “valsalva,” and “politzer” as headings. This provided 35 potential studies, five of which were randomised controlled trials (see table on website).1–5 A further unpublished trial was obtained from a pharmaceutical company (J Suonpää and R Grènman, unpublished data). All the subjects in that trial underwent myringotomy.

Each of the trials used a mechanical aid to assist autoinflation of the middle ear; one trial used a modified anaesthetic mask,1 two used toy balloons,4,5 and three used manufactured nasal balloons2,3 (unpublished data).

Unfortunately, no two studies were comparable in several respects: method of autoinflation, selection criteria for subjects, presence of unilateral or bilateral glue ear, length of treatment (range 2-12 weeks), and level of data analysis (patient versus ear). Two studies used poorly defined outcome measures such as “recovery” (unpublished data) and “absence of effusion,”1 two studies used tympanograms,2,3 and two studies measured improvement in hearing.4,5 One study did not provide direct data on the number of patients who improved in the treatment and control groups.4 Instead, improvement was estimated from the sample sizes, the standard error of the mean difference between the groups, and an increased audibility of 10 dB as measured on an audiogram.

None of the studies used blinding to outcome measures.

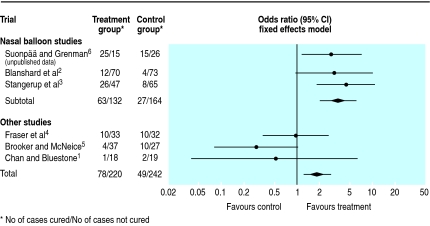

We recreated an intention to treat analysis of two of the studies, which reported results from “low compliance” and “high compliance” patients separately. The figure shows the odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for all the studies.

The study using the modified anaesthetics mask1 and one of the toy balloon studies5 showed no significant difference between the treatment and the controls, although the trend was towards treatment having an adverse effect on outcome. The other toy balloon study showed no significant difference between the treatment group and controls (odds ratio almost one).4 All the nasal balloon studies2,3 (unpublished data) showed a trend towards a benefit of treatment, although only two of these studies showed a significant benefit2 (unpublished data).

For all studies combined, the odds ratio for improvement with autoinflation was 1.85 (95% confidence interval 1.22 to 2.8; P=0.0038) suggesting a benefit. There was, however, significant heterogeneity in the observed effects between the six studies (Q=16.44, df=5, P=0.006); that is, there was evidence that the studies were not measuring a common treatment effect.

Because the nasal balloon studies provided a potentially homogeneous group (Q=0.52, df=2, P=0.76), we retrospectively calculated the Mantel-Haenszel statistic for the three studies. This indicated that children receiving autoinflation were around 3.5 times more likely to improve than controls (odds ratio 3.53, 2.03 to 6.14); however, two of these studies were of low quality3 (unpublished data).

Comment

Evidence for the use of autoinflation in the treatment of glue ear in children is conflicting but suggests that it may be of clinical benefit. Unfortunately, the studies are of variable and low quality. None used blinded outcome assessors, and all were short term studies. We cannot recommend autoinflation for clinical practice, as a better designed and larger trial is warranted.

Figure.

Meta-analysis (Mantel-Haenszel fixed effects model) of autoinflation as treatment for glue ear

Footnotes

Funding: Commonwealth Department of Health and Family Services.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Chan KH, Bluestone CD. Lack of efficacy of middle-ear inflation: treatment of otitis media with effusion in children. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1989;100:317–323. doi: 10.1177/019459988910000412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blanshard JD, Maw AR, Bawden R. Conservative treatment of otitis media with effusion by autoinflation of the middle ear. Clin Otolaryngol. 1993;18:188–192. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2273.1993.tb00827.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stangerup SE, Sederberg Olsen J, Balle V. Autoinflation as a treatment of secretory otitis media. A randomized controlled study. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1992;118:149–152. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1992.01880020041013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fraser JG, Mehta M, Fraser PA. The medical treatment of secretory otitis media. A clinical trial of three commonly used regimes. J Laryngol Otol. 1977;91:757–765. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100084334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brooker DS, McNeice A. Autoinflation in the treatment of glue ear in children. Clin Otolaryngol. 1992;17:289–290. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2273.1992.tb00997.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]