Abstract

Sterol-accelerated degradation of the enzyme 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase is one of several mechanisms through which cholesterol synthesis is controlled in mammalian cells. This degradation results from sterol-induced binding of the membrane domain of reductase to endoplasmic reticulum membrane proteins called Insig-1 and Insig-2, which are carriers of a ubiquitin ligase called gp78. The ensuing gp78-mediated ubiquitination of reductase is a prerequisite for its rapid, 26 S proteasome-mediated degradation from endoplasmic reticulum membranes, a reaction that slows a rate-limiting step in cholesterol synthesis. Here, we report that the membrane domain of hamster reductase is subject to sterol-accelerated degradation in Drosophila S2 cells, but only when mammalian Insig-1 or Insig-2 are co-expressed. This degradation mimics the reaction that occurs in mammalian cells with regard to its absolute requirement for the action of Insigs, sensitivity to proteasome inhibition, augmentation by nonsterol isoprenoids, and sterol specificity. RNA interference studies reveal that this degradation requires the Drosophila Hrd1 ubiquitin ligase and several other proteins, including a putative substrate selector, which associate with the enzyme in yeast and mammalian systems. These studies define Insigs as the minimal requirement for sterol-accelerated degradation of the membrane domain of reductase in Drosophila S2 cells.

In mammalian cells, the enzyme 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A (HMG-CoA)4 reductase catalyzes the reduction of HMG-CoA to mevalonate, a rate-limiting step in the synthesis of cholesterol and essential nonsterol isoprenoids (1). The reductase is a resident glycoprotein of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) that consists of a hydrophobic N-terminal domain with eight membrane-spanning segments followed by a hydrophilic C-terminal domain projecting into the cytosol where it exerts enzymatic activity (2–4). The membrane domain plays a key role in accelerated ER-associated degradation (ERAD) of reductase (2, 5), one of several mechanisms through which sterols and nonsterol isoprenoids exert stringent feedback control on the enzyme (6). Excess sterols cause reductase to become ubiquitinated through a reaction mediated by its membrane domain (5, 7–9). This ubiquitination results from sterol-induced binding of the membrane domain of reductase to one of two ER membrane proteins called Insig-1 and Insig-2 (5). A subset of Insig molecules is found associated with a membrane-anchored ubiquitin ligase named gp78, which mediates transfer of ubiquitin to a pair of cytosolically exposed lysine residues in the membrane domain of reductase. Once ubiquitinated, reductase presumably becomes extracted from membranes and delivered to 26 S proteasomes for degradation through an as yet undefined mechanism that likely involves the gp78-bound AAA-ATPase VCP/p97 and its associated cofactors. Current evidence indicates that this extraction may be augmented by the 20-carbon isoprenoid geranylgeraniol (8).

Insigs also play a major role in sterol-mediated regulation of another protein called Scap (10, 11), which like reductase contains a hydrophobic N-terminal domain with eight membrane-spanning segments and a large C-terminal domain located in the cytosol (12). Scap associates with sterol regulatory element-binding proteins (SREBPs), a family of transcription factors that enhance transcription of all of the genes required for cholesterol synthesis (including reductase) (13, 14). In sterol-deprived cells, Scap ferries SREBPs from their site of synthesis in the ER to the Golgi, where active fragments of SREBPs are proteolytically released from membranes (11, 15, 16). These fragments then migrate from the cytosol into the nucleus to enhance transcription of target genes, thereby increasing the synthesis of cholesterol. Sterol accumulation causes binding of Insigs to the membrane domain of Scap, which traps the protein in the ER and prevents delivery of its associated SREBP to the Golgi for release. Without this release, expression of SREBP target genes falls and rates of cholesterol synthesis decline.

Sterol-mediated regulation of SREBP-2, one of two SREBP isoforms expressed in mammalian cells, has been reconstituted in Drosophila Schneider S2 cells (17), which lack a recognizable Insig gene and cannot synthesize cholesterol or other sterols de novo (18, 19). In these experiments, S2 cells were transfected with cDNAs encoding human SREBP-2, hamster Scap, and human Insig-1 or Insig-2. Hamster Scap mediated translocation of human SREBP-2 from the ER to Golgi where the protein became proteolytically processed. Importantly, this translocation was inhibited by sterols, but only when human Insig-1 or Insig-2 were co-expressed. Thus, Scap and Insigs are the minimal requirements for sterol-regulated transport of mammalian SREBPs from the ER to the Golgi in insect cells.

In the current study, we reconstituted sterol-accelerated degradation of hamster reductase in Drosophila S2 cells. For this purpose, we transfected S2 cells with expression plasmids encoding either human Insig-1 or Insig-2 and the membrane domain of hamster reductase, which is necessary and sufficient for accelerated degradation in mammalian cells (2, 20). These studies demonstrate that Insig is sufficient to cause the membrane domain of reductase to become ubiquitinated and subsequently degraded by proteasomes through mechanisms mediated by the Drosophila Hrd1 ubiquitin ligase complex.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

We obtained 25-HC and 24,25-dihydrolanosterol from Steraloids; lanosterol from Sigma; MG-132 and digitonin from Calbiochem; and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated donkey anti-mouse IgG (affinity-purified) from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories. SR-12813 and Apomine were synthesized by the Core Medicinal Chemistry Laboratory at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center. Stock solutions of palmitate were made up in 0.15 m NaCl and 10% (w/v) fatty acid-free bovine serum albumin at pH 7.4 as described (21, 22). Stock solutions of ethanolamine were made up in H2O. Other reagents, including lipoprotein-deficient serum (LPDS, d > 1.215 g/ml), sodium compactin, sodium mevalonate, and geranylgeraniol were prepared or obtained from sources as described previously (5, 15).

Expression Plasmids

The previously described plasmids pAc-Insig-1-Myc and pAc-Insig-2-Myc encode amino acids 1–277 and 1–225 of human Insig-1 and Insig-2, respectively, followed by six copies of a c-Myc epitope (EQKLISEEDL) under control of the Drosophila actin 5C promoter (17). The following plasmids were constructed by subcloning the indicated open reading frame from mammalian expression vectors into pAc5.1/V5-HisB: pAc-HMG-Red-T7 (TM1–8) encodes amino acids 1–346 of hamster HMG-CoA reductase tagged with three copies of a T7 epitope (MASMTGGQQMG) (5); pAc-HMG-Red-T7 (TM1–8) (K89R/K248R) encodes amino acids 1–346 of the hamster HMG-CoA reductase tagged with three copies of a T7 epitope and harbors substitutions of arginine for lysines 89 and 248 (8).

The membrane domain of Drosophila HMG-CoA reductase (amino acids 1–391) and the open reading frames for Drosophila homologs of Hrd1 and Trc8 were amplified by PCR with the Phusion DNA polymerase kit (New England Biolabs) using first strand cDNA obtained by reverse transcriptase-PCR of total RNA isolated from Drosophila S2 cells. The primers and templates used are listed in Table 1. The PCR products were gel purified, subjected to restriction enzyme digestion, and subcloned into the insect cell expression vector pAc5.1/V5-HisB (Invitrogen). All of the proteins encoded by these plasmids contain three tandem copies of a T7 epitope at the C terminus. The integrity of all plasmids constructed above was confirmed by DNA sequencing.

TABLE 1.

Primers used for generation of plasmids

| Gene | Template | Primers (forward and reverse) |

|---|---|---|

| Hamster HMG-CoA reductase (X00494) | pCMV-HMG-Red-T7 (TM1–8) (5) | ATGTTGTCACGACTTTTCCGTATGCAT |

| GGACTCTGTCTCTGCTTGTTCAAAGAA | ||

| Drosophila HMG-CoA reductase (NM_170089) | cDNA | ATGATAGGACGTTTGTTTCGCGCC |

| CGGCAGAGGATCACGATTGTCAA | ||

| Drosophila Hrd1 (NM_143637) | cDNA | ATGCAGCTGCTCTTATCGTCCGTT |

| TTCCGCTGTCGTGCGTTCATTAGT | ||

| Drosophila Trc8 (NM_170413) | cDNA | ATGTCCGTGCGGACGAAGG |

| CTGCTGGTCCTGCGACATCC |

Culture and Transfection of Drosophila S2 Cells

Stock cultures of Drosophila S2 cells were maintained in a monolayer at 23 °C in medium A (Schneider's Drosophila medium containing 100 units/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin sulfate) supplemented with 10% (v/v) heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (HI-FCS). Cells were set up for experiments on day 0 in 6-well plates at a density of 1 × 106 cells per well in medium A supplemented with 10% HI-FCS. After 3–4 h, the cells were washed with PBS and transfected with 2–3 μg of DNA/well using 10 μl of Cellfectin transfection reagent (Invitrogen) in 2 ml of Medium B (Drosophila SFM medium). The total amount of DNA was kept constant in each well by the addition of empty vector DNA. On day 1, cells were washed with PBS and switched to medium C (IPL-41 containing 100 units/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin sulfate) supplemented with 10% HI-LPDS. On day 3, cells were subjected to treatments as described in the figure legends, after which they were harvested and pooled for analysis as described below.

Preparation of Cell Lysates and Immunoblot Analysis

Conditions of the incubations are described in the figure legends. At the end of the incubations, the cells were harvested by scraping in PBS and collected by centrifugation at 1000 × g for 5 min at 4 °C. Cell pellets from triplicate wells were combined, resuspended in RIPA buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mm NaCl, 0.1% (w/v) SDS, 1.5% (w/v) Nonidet P-40, 0.5% (w/v) sodium deoxycholate, and 2 mm MgCl2) containing protease inhibitors (0.1 mm leupeptin, 5 μg/ml pepstatin A, 2 μg/ml aprotinin, 25 μg/ml N-acetyl-leucinal-leucinal-norleucinal, 0.5 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 0.5 mm Pefabloc, and 0.25 mm dithiothreitol), disrupted by passing through a 22-gauage needle, and rotated at 4 °C for 30 min. Following removal of insoluble material by centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 5 min at 4 °C, aliquots of clarified lysates were subjected to 8% SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Immunoblot analysis was carried out with 1 μg/ml monoclonal anti-T7 IgG (Novagen), 2 μg/ml monoclonal IgG-9E10, 0.4 μg/ml monoclonal IgG-P4D1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), or 2 μg/ml monoclonal IgG-3B2 (22).

Immunoprecipitation

Following treatments as described in the figure legends, cells were harvested and lysed in PBS containing 0.2–1% (w/v) digitonin plus 5 mm EDTA and 5 mm EGTA supplemented with protease inhibitors as described above. The clarified lysates were then subjected to immunoprecipitation with either 50 μl of monoclonal anti-T7 IgG-coupled agarose beads (Novagen) or 5 μg of polyclonal anti-Myc IgG plus 50 μl of protein A/G-coupled agarose beads (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) as described previously (8). Aliquots of the pellet and supernatant fractions of the immunoprecipitation were subjected to SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western immunoblot analysis as described above.

Ubiquitination of HMG-CoA Reductase

Ubiquitination of hamster HMG-CoA reductase in Drosophila S2 cells was assessed as previously described (8). Briefly, S2 cells were harvested and lysed in PBS containing 1% Nonidet P-40, 1% deoxycholate, 5 mm EDTA, and 5 mm EGTA; the buffer was also supplemented with protease inhibitors and 10 mm N-ethylmaleimide. Clarified lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with the anti-T7 IgG-coupled agarose beads as described above. Aliquots of the immunoprecipitates were subjected to SDS-PAGE, followed by immunoblot analysis with 0.4 μg/ml monoclonal IgG-P4D1 (against ubiquitin) and 1 μg/ml monoclonal anti-T7 IgG (against reductase).

Production of Double-stranded (ds) RNA and RNA Interference (RNAi)-mediated Knockdown in Drosophila S2 Cells

DNA templates used for synthesis of dsRNA were amplified by PCR with the Phusion DNA polymerase kit (New England Biolabs) using first strand cDNA obtained by reverse transcriptase-PCR of total RNA isolated from Drosophila S2 cells; sequences of the primers used in the amplifications are shown in Table 2. The resulting PCR products (700 bp) were purified with the QIAquick PCR Purification kit (Qiagen) and subsequently used to synthesize dsRNA with the MEGAscript T7 kit (Ambion); products of these reactions were purified using the RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen). RNAi was performed as previously described with minor modifications (22). S2 cells were set up in 6-well plates on day 0 at a density of 1 × 106 cells per well in 1 ml of medium B. Each well received 15 μg of dsRNA immediately after plating and was incubated for 1 h, after which 2 ml of medium A containing 10% HI-FCS was added to each well. On day 1, the cells were transfected as described above and subsequently treated on day 3 as described in the figure legends.

TABLE 2.

Primers used for generation of dsRNAs

Forward and reverse primers contain the T7 binding site: GAATTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGA.

| Gene | Nucleotides | Primers (forward and reverse) |

|---|---|---|

| Mouse CYP7A1 | 317–339 | CGAAGGCATTTGGACACAGAAGC |

| 1044–1065 | CCGCAGAGCCTCCTTGATGATG | |

| dDerlin-1 | 33–51 | CCGCTTCACCCGCTACTGG |

| (CG10908-RA) | 670–689 | TGCCTAGGTGGTGCTCTGCT |

| dDerlin-2/3 | 105–127 | GCCGCTGCAGCTCTACTTCAATC |

| (CG14899-RA) | 733–754 | GATTCGCTGGCTCCTCATCCTG |

| dHerp | 696–714 | CTTGCCGCCACCGACTCAA |

| (CG14536-RA) | 1350–1373 | AGCGAGGTGAAGAACGTGATGACA |

| dHrd1 | 220–243 | CATCTGCTGGAGCGCTTTTGGTAT |

| (CG1937-RA) | 892–915 | GCAGGGCAGTTTCTTTGAGTGATT |

| dNpl4 | 67–90 | GTGCGCCATCGTCTGTTTGTGTTA |

| (CG4673-RA) | 810–831 | GGTGCGCCAGTAGTTGAGGAAG |

| dOs9 | 111–138 | TGATTTCGAAGTGCCGGATTTAGATGTG |

| (CG6766-RA) | 802–825 | CGCCTCGGATTCAACCCATTCCTT |

| dSel1 | 80–101 | ACATTGATGGTACGGGCAGCAG |

| (CG10221-RA) | 822–842 | TGGATCAGCGCCTTCTCACAG |

| dTeb4 | 823–846 | GTTTTTCTGGAGCACGTCTTCTGG |

| (CG1317-RB) | 1524–1548 | CAGCAATTGCAAGTTAACCGCTGAA |

| dTrc8 | 1052–1074 | TCGACGGCTGTGAGACTATGACG |

| (CG2304-RA) | 1617–1638 | GATGCCGAAGCAGAACTCCACT |

| dUbc1 | 1–22 | ATGGCGAACATGGCAGTGTCGC |

| (CG8284-RA) | 577–599 | TAACTGAACAGGCCCTCGGTGGC |

| dUbc6 | 48–71 | GTCGCGCATGAAGCAGGACTATAT |

| (CG5823-RA) | 699–717 | TCCTCCGCCGCTGGCCAAA |

| dUbc7 | 1–20 | ATGGCTGGGTCCGCACTGCG |

| (CG4443-RA) | 478–504 | TTACGCCGGTAAACCAAGAGTTTTGCG |

| dUbxd2 | 540–566 | GGAGGCCAAGACGAATCCACCAAATTC |

| (CG8042-RA) | 1198–1218 | TCGGATCTGCAGCCTCGTCTC |

| dUbxd8 | 20–42 | CCAACGAACAGACGGAGAAGGTC |

| (CG10372-RA) | 654–675 | GGCTACGTCGCATCCCCATAAC |

| dUfd1 | 163–187 | CGCCTGAATGTCGAGTATCCAATGC |

| (CG6233-RA) | 853–878 | GCTACGGCATCATCTTCTTGGCTTCT |

Isolation of Total RNA and Quantitative Real-time PCR Analysis

Total RNA was prepared from Drosophila S2 cells using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen) and used as a template for cDNA synthesis employing the TaqMan reverse transcription reagents (Applied Biosystems) and random hexamer primers. Quantitative real-time PCR was performed as previously described (23) using the primers listed in Table 3. Relative expression was calculated using the comparative CT method. Drosophila acetaldehyde dehydrogenase mRNA was used as an internal control for variations in amounts of mRNA.

TABLE 3.

Primers used for real-time PCR analysis

| Drosophila Gene | Nucleotides | Primers (forward and reverse) |

|---|---|---|

| Acetaldehyde dehydrogenase | 1180–1254 | GAGGGCCTACCCGGCTACT |

| (CG3752-RA) | CTCCCTTGCAATGGTCATATCA | |

| Derlin-1 | 642–701 | TCAAGTTCCAATACTCGCAGGAT |

| (CG10908-RA) | AGAACTGCGGCGTTTCCA | |

| Derlin-2/3 | 1072–1138 | ATGAGCACATCGAACGCAACT |

| (CG14899-RA) | CCGCCCCAAGGAAATCC | |

| Herp | 1142–1217 | CCTGCTGATCCTCAGATTAATGG |

| (CG14536-RA) | CGTGCATTTCCGGTTCCT | |

| Hrd1 | 1562–1635 | CGGCTTGCCCAATGGA |

| (CG1937-RA) | GCGAAATCATGGGCATTACTG | |

| Os9 | 1477–1546 | AGCCGAAGACGTGCCAGTATA |

| (CG6766-RA) | TCGGCGTTGTGGATGAGAT | |

| Sel1 | 2944–3035 | TCGATCCCACTGGTTAGTCTTAGTAA |

| (CG10221-RA) | TCGGGCGAAATTAGATGATAAATAT | |

| Teb4 | 2815–2884 | TCGAGCCTACATGGATGGATT |

| (CG1317-RB) | GACCGGCACAGCCAAGTCT | |

| Trc8 | 1966–2036 | CTGCTGCACTTCCTGCACAA |

| (CG2304-RA) | CGCGAGGGATTCCGTG | |

| Ubc1 | 956–1020 | TCCCAGCCGCACTAGCAT |

| (CG8284-RA) | GAAGTTGGCCGGTGTTCTTG | |

| Ubc6 | 1047–1111 | CCTGCGCAACACCAACTTCT |

| (CG5823-RA) | GCAGCCGCTGCTTGATCT | |

| Ubc7 | 458–516 | CCTGAGGGCACTTGTTTCGA |

| (CG4443-RA) | GGATAGTCGGTCGGAAAGATGA | |

| Ubxd2 | 1895–1960 | TCCGCCGGCTCATAACAC |

| (CG8042-RA) | CCGGGTCGCTGTTGGA | |

| Ubxd8 | 1367–1432 | AGGCATACGAGCAGAGTTTGC |

| (CG10372-RA) | CATCCCGCTCCCTTTGC | |

| Ufd1 | 499–568 | GTGGCCACCTTCTCAAAGTTTC |

| (CG6233-RA) | GCACCGCCTTGGGATTG |

RESULTS

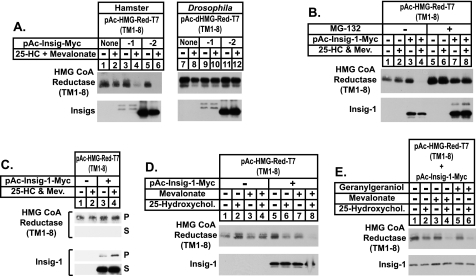

Fig. 1A shows an experiment designed to determine whether Insig is the minimal requirement for sterol-accelerated degradation of hamster reductase in Drosophila S2 cells. Considering our previous findings that established the membrane domain of reductase as necessary and sufficient for regulated degradation (20, 24), we transfected S2 cells with an expression plasmid encoding the entire membrane domain of hamster reductase, followed by three tandem copies of the T7 epitope. Expression of this plasmid, designated pAc-HMG-Red-T7 (TM1–8), is driven by the Drosophila actin 5c promoter (pAc). Some of the dishes were also transfected with pAc-Insig-1-Myc or pAc-Insig-2-Myc, expression plasmids that encode amino acids 1–277 of human Insig-1 and 1–225 of human Insig-2, respectively. Following transfection, cells were treated in the absence or presence of the regulatory oxysterol 25-hydroxycholesterol (25-HC) plus mevalonate, which provides a source of nonsterol isoprenoids that combine with sterols to maximally accelerate degradation of reductase in mammalian cells (8, 25–27). The cells were subsequently harvested and detergent lysates were prepared; aliquots of the resulting lysates were then subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-T7 and anti-Myc monoclonal antibodies to detect the membrane domain of reductase and Insigs, respectively. Immunoblotting revealed that expression of the membrane domain of reductase was constant in the absence or presence of 25-HC plus mevalonate when the protein was overexpressed in cells (Fig. 1A, top panel, lanes 1 and 2). Co-expression of either Insig-1 or Insig-2 (Fig. 1A, bottom panel, lanes 3–6) led to the disappearance of the membrane domain of reductase, but only when the cells were treated with 25-HC plus mevalonate (Fig. 1A, top panel, lanes 3–6). The doublet in the Insig-1 immunoblots was caused by utilization of two sites of translational initiation. The larger band results from translation initiation at residue 1, whereas the smaller band comes from initiation at residue 37 (10). The doublet sometimes observed in immunoblots for the membrane domain of reductase is likely due to incomplete N-glycosylation. Both glycosylated and non-glycosylated forms of reductase are subject to sterol-induced degradation (data not shown).

FIGURE 1.

Insig-mediated, sterol-accelerated degradation of the membrane domain of hamster HMG-CoA reductase in Drosophila S2 cells. A–E, S2 cells were set up on day 0 at 1 × 106 cells per well of 6-well plates in medium A supplemented with 10% HI-FCS. Several hours later, cells were washed with PBS and transfected in medium B with 1.8 μg of pAc-HMG-Red-T7 (TM1–8), 50 ng of pAc-dHMG-Red-T7 (TM1–8), and 0.2 μg pAc-Insig-1-Myc or pAc-Insig-2-Myc as indicated using Cellfectin reagent. The total amount of DNA was adjusted to 2 μg/well by the addition of empty vector. On day 1, cells were switched to medium C supplemented with 10% HI-LPDS. On day 3, cells were treated with the identical medium in the absence (−) or presence (+) of 2.5 μm 25-HC plus 10 mm mevalonate (A–C); in D and E, cells were treated with various combinations of 2.5 μm 25-HC, 10 mm mevalonate, and 30 μm geranylgeraniol. In B, the proteasome inhibitor MG-132 was also present at a concentration of 10 μm as indicated; in C, all of the dishes received MG-132. A, B, D, and E, following incubation for 6 h, the cells were harvested and detergent lysates were prepared as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Aliquots of the lysates (40 μg of protein/lane for reductase and 10 μg of protein/lane for Insig) were fractionated by 8% SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Immunoblot analysis was carried out with 1 μg/ml anti-T7 IgG (against reductase) and 2 μg/ml IgG-9E10 (against Insig). C, following incubation for 2 h, the cells were harvested, lysed in PBS containing 1% digitonin, and immunoprecipitation was carried out with anti-T7 IgG-coupled agarose beads as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Aliquots of the pellet (P) and supernatant (S) fractions were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analysis was performed as described above.

We transfected parallel sets of dishes with an expression plasmid encoding the membrane domain of Drosophila reductase (designated pAc-dHMG-Red-T7) (TM1–8). Expression of this protein was not subject to sterol regulation (Fig. 1A, top panel, lanes 7–12), regardless of co-expression of either Insig-1 or Insig-2 (Fig. 1A, bottom panel, lanes 9–12). It is noteworthy that Drosophila reductase contains the crucial lysine residues in the membrane domain that are required for sterol-induced ubiquitination of the mammalian enzyme (see below). The inability of 25-HC to stimulate degradation of the membrane domain of Drosophila reductase is consistent with previous observations that endogenous reductase in either Drosophila S2 or Kc cells did not become degraded in the presence of sterols (28, 29).

To establish a role for 26 S proteasomes in sterol-mediated degradation of the membrane domain of reductase in S2 cells, we employed the inhibitor MG-132. Consistent with results of Fig. 1A, disappearance of the membrane domain of reductase required Insig-1 co-expression and treatment of the cells with 25-HC plus mevalonate (see Fig. 1B, top panel, lanes 1–4). Inclusion of MG-132 in the treatment medium blocked this disappearance (see Fig. 1B, lanes 5–8), indicating that regulated degradation of reductase in S2 cells requires the action of proteasomes. Notably, MG-132 also stabilized Insig-1 (Fig. 1B, bottom panel, compare lanes 3 and 4 with lanes 7 and 8), demonstrating that the protein is subject to proteasome-mediated degradation in S2 cells as well as mammalian cells (30).

In the experiment of Fig. 1C, we used co-immunoprecipitation to determine whether 25-HC and mevalonate trigger reductase-Insig binding. S2 cells transfected with the membrane domain of reductase in the absence or presence of Insig-1 were treated with MG-132; some of the dishes also received 25-HC plus mevalonate. Following treatments, the cells were harvested and the membrane domain of reductase was immunoprecipitated from detergent lysates with anti-T7-coupled agarose beads. Immunoblotting of the pellet and supernatant fractions revealed that reductase immunoprecipitation was essentially complete (Fig. 1C, top two panels, lanes 1–4). When co-expressed with the membrane domain of reductase, Insig-1 appeared in the pellet fraction (Fig. 1C, third panel, lane 3) and this co-immunoprecipitation was enhanced when the cells were treated with 25-HC plus mevalonate (lane 4).

To directly address the requirement for nonsterol isoprenoids in the degradation of reductase in S2 cells, we designed the experiment of Fig. 1D in which 25-HC and mevalonate were added to cells individually or in combination. As expected, the membrane domain of reductase was fully resistant to sterol-induced degradation in the absence of Insig-1 co-expression (Fig. 1D, top panel, lanes 1–4). In the presence of Insig-1 (Fig. 1D, bottom panel, lanes 5–8), neither 25-HC nor mevalonate treatment alone stimulated degradation of the membrane domain of reductase to a significant extent (Fig. 1D, top panel, lanes 5–7). However, the protein became completely degraded in the presence of both 25-HC and mevalonate (Fig. 1D, lane 8). Consistent with our previous findings in mammalian cells (8), the mevalonate requirement for reductase degradation in S2 cells was satisfied by the addition of geranylgeraniol (Fig. 1E, top panel, compare lanes 1 and 2 with lanes 5 and 6).

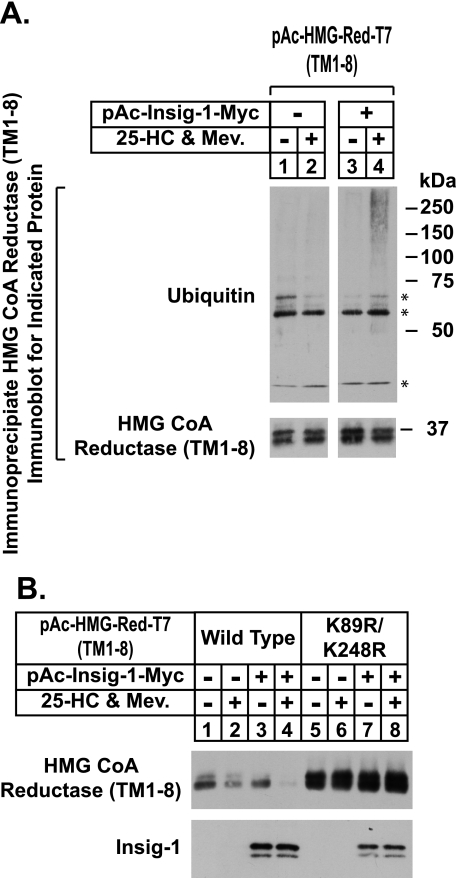

To determine the ubiquitination status of the membrane domain of reductase, transfected S2 cells were subjected to MG-132 treatment in the absence or presence of 25-HC plus mevalonate. Following treatments, the cells were harvested and the membrane domain of reductase was immunoprecipitated from detergent extracts with anti-T7 antibody. Immunoblot analysis of the precipitated material with anti-T7 and anti-ubiquitin antibodies reveal that in the absence of Insig-1, the membrane domain of reductase did not become ubiquitinated in the presence of 25-HC plus mevalonate (Fig. 2A, top panel, lanes 1 and 2). Co-expression of Insig-1 led to a significant increase in the amount of ubiquitinated reductase, but only in the presence of 25-HC plus mevalonate (Fig. 2A, lanes 3 and 4).

FIGURE 2.

Sterols stimulate Insig-dependent ubiquitination and degradation of the membrane domain of hamster HMG-CoA reductase in Drosophila S2 cells. A and B, S2 cells were set up and transfected on day 0 and refed on day 1 as described in the legend of Fig. 1. On day 3, the cells were treated with medium C supplemented with 10% HI-LPDS in the absence or presence of 2.5 μm 25-HC and 10 mm mevalonate (Mev.). Following incubation for 6 h, the cells were harvested; detergent lysates were prepared and immunoblot analysis was carried out as described in the legend of Fig. 1. A, following incubation for 2 h, the cells were lysed in PBS containing 1% Nonidet P-40, 1% deoxycholate, and 10 mm N-ethylmaleimide; transfected reductase was immunoprecipitated from the resulting lysates with anti-T7-coupled agarose beads as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Aliquots of the immunoprecipitated material were subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblot analysis with 1 μg/ml anti-T7 IgG (against reductase) and 0.4 μg/ml IgG-P4D1 (against ubiquitin). Asterisks denote reactivity of heavy and light chains of the anti-T7 antibody used in immunoprecipitations with secondary antibody used for immunoblotting.

The current evidence in mammalian cells indicates that two lysine residues (amino acids 89 and 248) in the membrane domain of reductase are sites of Insig-mediated, sterol-induced ubiquitination (8). To determine whether modification of these lysines is required for degradation of reductase in S2 cells, we examined the degradation of a mutant form of the protein that harbors conservative substitutions of arginine for lysines 89 and 248. These substitutions prevent sterol-induced ubiquitination and degradation of reductase in mammalian cells (8). Consistent with this, Fig. 2B shows that the wild type version of the membrane domain of reductase (top panel, lanes 3 and 4), but not the lysine mutant of the protein (lanes 7 and 8), was subjected to Insig-mediated, sterol-induced degradation in S2 cells.

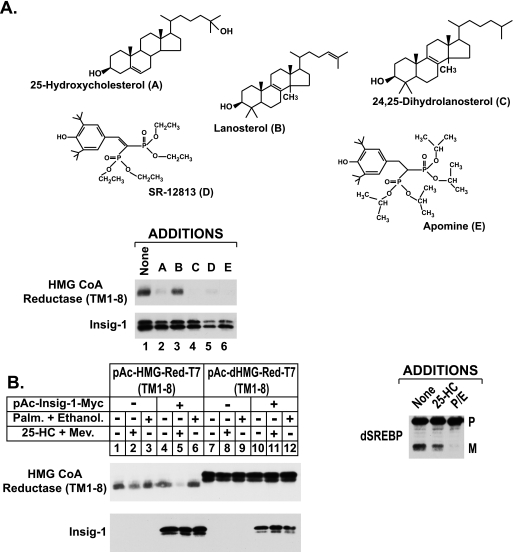

To further characterize degradation of hamster reductase in S2 cells, we next examined the sterol specificity of the reaction. Previous studies from our group and others have established that in addition to 25-HC, the cholesterol synthesis intermediate 24,25-dihydrolanosterol and 1,1-bisphosphonate esters SR-12813 and Apomine trigger degradation of reductase in mammalian cells (24, 31–33). Fig. 3A shows that 25-HC, 24,25-dihydrolanosterol, SR-12813, and Apomine stimulated degradation of the membrane domain of reductase in transfected S2 cells (Fig. 3A, top panel, lanes 2, 4, 5, and 6, respectively). The inability of lanosterol to stimulate degradation of the membrane domain of reductase (lane 3) contrasts with our previous findings (31), which likely resulted from contamination of 24,25-dihydrolanosterol in preparations of lanosterol used in those studies. It should be noted that purity of lanosterol and 24,25-dihydrolanosterol used in the current experiment was confirmed by GC-mass spectrometry (data not shown).

FIGURE 3.

Selectivity of Insig-mediated degradation of the membrane domain of hamster HMG-CoA reductase in Drosophila S2 cells. A and B, S2 cells were set up and transfected on day 0 and treated on day 1 as described in the legend of Fig. 1. A, cells were treated on day 3 for 6 h with medium C containing 10% HI-LPDS and 10 mm mevalonate in the absence or presence of 2.5 μm 25-HC, 25 μm lanosterol, 25 μm 24,25-dihydrolanosterol, 30 μm SR-12813, or 10 μm Apomine. In B, the cells were treated for 6 h with medium C containing 10% HI-LPDS in the absence or presence of 2.5 μm 25-HC plus 10 mm mevalonate or 100 μm palmitate plus 100 μm ethanolamine. At the end of the incubations, cells were harvested; detergent lysates were prepared and subjected to immunoblot analysis as described in the legend of Fig. 1. Proteolytic processing of dSREBP was assessed by immunoblot analysis using 2 μg/ml IgG-3B2. P denotes the precursor form and M denotes the mature nuclear form.

In contrast to the mammalian system, ER to Golgi transport of Drosophila Scap-SREBP is not inhibited by 25-HC but rather by a lipid derived from palmitate and ethanolamine (22). This observation prompted us to next determine the effect of palmitate plus ethanolamine treatment on degradation of the membrane domain of hamster reductase in S2 cells (Fig. 3B). Neither 25-HC and mevalonate (Fig. 3B, top panel, lane 2) nor a combination of palmitate and ethanolamine (lane 3) stimulated degradation reductase in the absence of Insig-1. As expected, co-expression of Insig-1 led to 25-HC plus mevalonate-induced degradation of reductase (lane 5), but palmitate and ethanolamine continued to have no effect (lane 6). Importantly, the membrane domain of Drosophila reductase was not subject to accelerated degradation regardless of the absence or presence of Insig-1, 25-HC and mevalonate, and palmitate plus ethanolamine (lanes 7–12). The combination of palmitate, ethanolamine, and mevalonate treatment also failed to stimulate degradation of both hamster and Drosophila reductase in S2 cells (data not shown). It should be noted that palmitate plus ethanolamine prevented processing of Drosophila SREBP as expected.

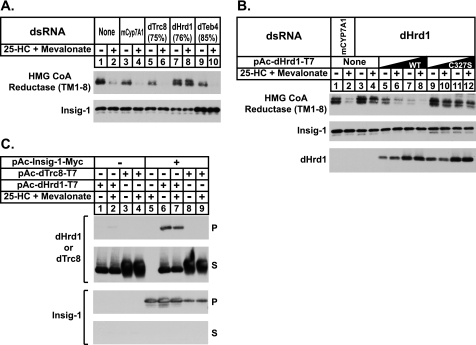

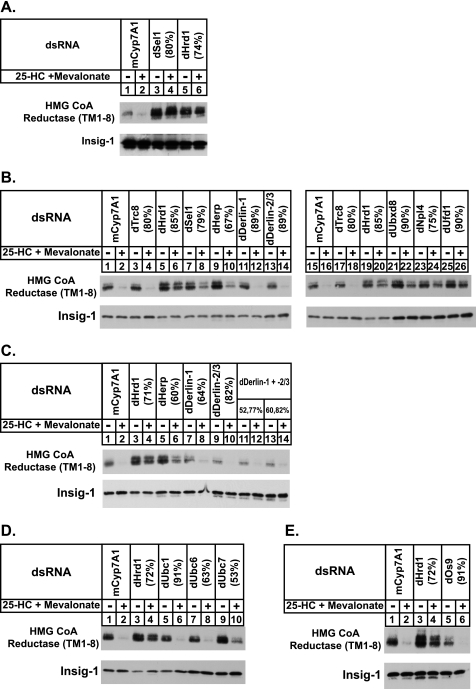

In mammalian cells, Insigs bridge reductase to gp78 when sterols accumulate (11, 34). Faithful reconstitution of sterol-accelerated degradation of the membrane domain of reductase in S2 cells points to the existence of a Drosophila ubiquitin ligase that is capable of binding to human Insig-1 and initiating reductase ubiquitination. Data base searches failed to identify a recognizable homolog of mammalian gp78 in the Drosophila genome. Instead, these searches revealed the existence of Drosophila homologs of three membrane-bound mammalian ubiquitin ligases: Trc8, Teb4, and Hrd1. Fig. 4A shows an experiment in which we used RNAi to determine whether the presence of Drosophila Trc8, Hrd1, or Teb4 (dTrc8, dHrd1, and dTeb4, respectively) is required for sterol-induced degradation of reductase in S2 cells. In untreated cells and in those treated with a control dsRNA against an irrelevant mRNA (mouse Cyp7A1), the membrane domain of reductase became degraded in the presence of 25-HC and mevalonate (Fig. 4A, top panel, lanes 1–4). The protein was similarly degraded when the cells were subjected to treatment with dsRNA against mRNAs for dTrc8 and dTeb4 (Fig. 4A, lanes 5, 6, 9, and 10). In contrast, the RNAi-mediated knockdown of dHrd1 completely blocked the sterol-accelerated degradation of reductase (Fig. 4A, lanes 7 and 8). Similar results were obtained for Insig-2-mediated degradation (data not shown). It is worth noting that knockdown of dTeb4, but not dHrd1, caused a modest increase in the amount of Insig-1 (Fig. 4A, bottom panel, compare lanes 7 and 8 with lanes 9 and 10), which indicates that the ubiquitin ligase may participate in the degradation of the protein in S2 cells (see Fig. 2A). Quantitative real-time PCR analysis revealed that RNAi reduced the expression of dTrc8, dHrd1, and dTeb4 by 75, 76, and 85%, respectively.

FIGURE 4.

Drosophila Hrd1 (dHrd1) is the ubiquitin ligase required for sterol-induced degradation of the membrane domain of hamster HMG-CoA reductase in Drosophila S2 cells. A and B, S2 cells were set up on day 0 at 1 × 106 cells per well of 6-well plates in 1 ml of medium B. Immediately after plating, the cells were incubated for 1 h with 15 μg of dsRNA targeted against the indicated endogenous mRNAs. Following this incubation, each well received 2 ml of medium A supplemented with 10% HI-FCS. On day 1, the cells were washed with PBS and transfected with Cellfectin reagent in medium B as follows: A, 1.8 μg of pAc-HMG-Red-T7 (TM1–8) and 0.2 μg of pAc-Insig-1-Myc per well, and B, 1.8 μg of pAc-HMG-Red-T7 (TM1–8), 0.2 μg of pAc-Insig-1-Myc, and 0.3 or 1 μg of pAc-dHrd1-T7 per well (total amount of DNA was adjusted to 3 mg/well by addition of empty vector). On day 2, the cells were switched to medium C supplemented with 10% HI-LPDS and subsequently treated for 6 h on day 3 with the identical medium in the absence or presence of 2.5 μm 25-HC and 10 mm mevalonate. Following this incubation, cells were harvested; detergent lysates were prepared and subjected to immunoblot analysis as described in the legend of Fig. 1. The efficiency of RNAi-mediated knockdown was determined in parallel wells by quantitative real-time PCR analysis and the percent knockdown of the indicated mRNA relative to that in control-treated cells is indicated in parentheses. C, S2 cells were set up on day 0 in 6-well plates and transfected with 1 μg of pAc-Insig-1-Myc and 0.5 μg of pAc-dHrd1-T7 or 0.5 μg of pAc-dTrc8-T7 per well in medium B; the cells were subsequently treated on day 1 as described in the legend to Fig. 1. On day 3, the cells were refed medium C supplemented with 10% HI-LPDS without or with 2.5 μm 25-HC plus 10 mm mevalonate. After 2 h, cells were harvested and lysed in PBS containing 0.2% digitonin. Immunoprecipitation was carried out using anti-Myc IgG and protein A/G-coupled agarose beads. Aliquots of the resulting pellet (P) and supernatant (S) fractions of the immunoprecipitation were subjected to immunoblot analysis with 1 μg/ml anti-T7 IgG (against dHrd1 or dTrc8) and 2 μg/ml IgG-9E10 (against Insig).

The effects of dHrd1 knockdown on degradation of reductase appear to be specific as indicated by the experiment of Fig. 4B. Here, we compared the ability of wild type dHrd1 and a mutant form of the enzyme to restore reductase degradation in dHrd1-knockdown cells. The mutant form of dHrd1 evaluated harbors a substitution of Ser for Cys-327 in the C-terminal RING-H2 domain, which corresponds to Cys-399 and Cys-329 in yeast and human Hrd1, respectively. Mutation of this cysteine residue abolishes in vitro and in vivo ubiquitin ligase activity of the enyzmes (35–37). Degradation of reductase in dHrd1 knockdown cells (Fig. 4B, top panel, compare lanes 1 and 2 with 3 and 4) was restored by the overexpression of wild type, T7-tagged dHrd1 (lanes 5–8), but not the inactive C327S mutant (lanes 9–12). A role for dHrd1 in sterol-accelerated degradation of reductase is further supported by its co-immunoprecipitation with Insig-1 (Fig. 4C, top panel, lanes 6 and 7). The specificity of this interaction is indicated by the finding that Insig-1 failed to co-immunoprecipitate with dTrc8 (Fig. 4C, lanes 8 and 9), which does not participate in degradation of reductase in S2 cells.

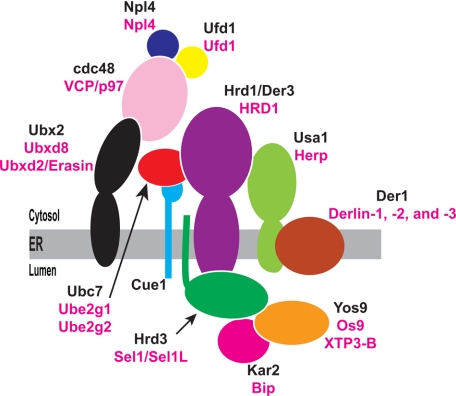

In the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Hrd1 associates with a large complex containing its cofactor Hrd3, the cytosolic ubiquitin conjugating enzyme Ubc7, and its membrane anchor Cue1, the polytopic ER membrane protein Der1, and its recruitment factor Usa1, the UBX domain-containing protein Ubx2, which aids in the recruitment of an AAA-ATPase cdc48, and the Hsp70 chaperone Kar2 bound to the lectin Yos9 (Fig. 5) (38). The mammalian genome encodes for homologs of all members of the yeast Hrd1 complex, except Cue1. Moreover, sucrose gradient centrifugation experiments indicate that mammalian Hrd1 exists in a large multiprotein complex (39). In Fig. 6A, we examined a role for dSel1, the Drosophila homolog of Hrd3, in sterol-induced degradation of the membrane domain of reductase in S2 cells. In yeast, Hrd3 forms a 1:1 stoichiometric complex with Hrd1 and is required for Hrd1-mediated ubiquitin ligase activity in cells (35, 40). The results show that RNAi-mediated knockdown of dSel1 abrogated sterol-induced degradation of the membrane domain of reductase (compare Fig. 6A, lanes 1 and 2 with 3 and 4); similar results were obtained in dHrd1-knockdown cells (lanes 5 and 6).

FIGURE 5.

The S. cerevisiae Hrd1 ubiquitin ligase complex. Schematic of the Hrd1 complex including lumenal factors Kar2 and Yos9 that, together with Hrd3, function in the initial steps of substrate recognition and recruitment. Yeast proteins are shown in black and their mammalian counterparts are shown in magenta.

FIGURE 6.

Requirement of dHrd1 complex components for sterol-accelerated degradation of the membrane domain of hamster HMG-CoA reductase in Drosopohila S2 cells. A–E, S2 cells were set up, transfected, and subjected to RNAi-mediated knockdown as described in the legend of Fig. 4A. The efficiency of RNAi-mediated knockdown for each mRNA is indicated in parentheses.

In the next set of experiments, we used RNAi to identify Drosophila homologs of other Hrd1 complex components that are required for the degradation of reductase in S2 cells (see Fig. 5). As expected, the membrane domain of reductase was subjected to sterol-induced degradation in cells treated with dsRNA against mouse Cyp7A1 or dTrc8 (Fig. 6B, top panel, lanes 1–4), but not in cells treated with dsRNA against dHrd1 and dSel1 (lanes 5–8). Degradation of the membrane domain of reductase was also significantly blunted by RNAi-mediated knockdown of dHerp (Fig. 6B, lanes 9 and 10), dUbxd8 (lanes 21 and 22), and VCP/p97 cofactors dNpl4 (lanes 23 and 24), and dUfd1 (lanes 25 and 26). Sterol-accelerated degradation of reductase continued in cells treated with dsRNA against the two Drosophila homologs of yeast Der1, dDerlin-1 and dDerlin-2/3 (Fig. 6B, lanes 11–14); a similar result was obtained when expression of both dDerlin-1 and dDerlin-2/3 were reduced by RNAi (Fig. 6C, top panels, lanes 11–14). Fig. 6D shows that knockdown of the ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme dUbc7 partially blocked regulated degradation of the membrane domain of reductase (Fig. 6D, top panel, lanes 9 and 10); this partial effect is likely due to incomplete knockdown (53%) of dUbc7. Although the membrane domain of reductase contains a single N-linked glycan, knockdown of lectin-like dOs9 failed to inhibit sterol-induced degradation of the protein (Fig. 6E, top panel, compare lanes 1 and 2 with 5 and 6). This result is consistent with the observation that a mutant form of the membrane domain of reductase that cannot become N-glycosylated continues to become degraded in the presence of sterols (data not shown). A summary of the results obtained in Figs. 5 and 6 is shown in Table 4.

TABLE 4.

Role of dHrd1 complex components in sterol-accelerated degradation of hamster HMG-CoA reductase in Drosophila S2 cells

| S. cerevisiae | Mammalian cells | Required for degradation of HMG-CoA reductase in Drosophila S2 cells |

|---|---|---|

| Hrd1 | Hrd1 | Yes |

| Hrd3 | Sel1 or Sel1L | Yes |

| Usa1 | Herp | Yes |

| Yos9 | Os9 | No |

| Kar2 | Bip | Not determined |

| cdc48 | VCP/p97 | Not determined (cell toxicity) |

| Ubx2 | Ubxd8 | Yes |

| Npl4 | Npl4 | Yes |

| Ufd1 | Ufd1 | Yes |

| Ubc7 | Ubc7 | Yes |

| Der1 | Derlin-1, -2, and -3 | No |

| Cue1 | None |

DISCUSSION

The current results establish that Insig is the minimal requirement for sterol-accelerated degradation of the membrane domain of hamster HMG-CoA reductase in Drosophila S2 cells. By several criteria, this degradation precisely mirrors the reaction that occurs in mammalian cells. Remarkably, the selectivity of reductase degradation is also preserved in the Drosophila system: the reaction is stimulated by not only 25-hydroxychoesterol, but also by 24,25-dihydrolanosterol, SR-12813, and Apomine (Fig. 3A). The action of 25-HC in S2 cells can be explained by the finding that the oxysterol directly binds to Insig, allowing it to bind to and modulate the activities of Scap and reductase (41). The mechanism through which 24,25-dihydrolanosterol, SR-12813, and Apomine accelerate degradation of reductase is unknown, but is likely distinct from that of 25-HC. This is indicated by the inability of these compounds to bind Insig in vitro and inhibit Scap-mediated processing of SREBPs (41).5 Considering that cholesterol binds directly to the membrane domain of Scap and induces Scap-Insig complex formation (42), we reason the most likely mode of action for 24,25-dihydrolanosterol, SR-12813, and Apomine involves their direct binding to the membrane domain of reductase.

A major role for the Drosophila homolog of the yeast ubiquitin ligase Hrd1 in sterol-accelerated degradation of hamster reductase is revealed in RNAi experiments (see Fig. 4A). Hrd1 was first identified in genetic analyses of regulated degradation of Hmg2p, one of two reductase isozymes in yeast (43). Together with its binding partner Hrd3, Hrd1 exists in a multiprotein complex (see Fig. 5) that mediates ER-associated degradation of Hmg2p and a variety of misfolded ER lumenal and membrane proteins (38).

Our studies show that the Drosophila homolog of Hrd3, dSel1, and a subset of dHrd1 complex components including dHerp (Usa1p), dUbxd8 (Ubx2), dUbc7 (Ubc7), dNpl4, and dUfd1 are also required for reductase degradation in S2 cells (see Table 4 for summary). A role for dUbxd8, dNpl4, and dUfd1 in degradation of reductase is not surprising considering their well established roles in the action of VCP/p97. Unfortunately, we could not directly address a role for VCP/p97 in the current studies owing to cellular toxicity of the RNAi-mediated knockdown of the protein (data not shown). On the other hand, the requirement for dHerp in degradation of reductase is somewhat surprising when previous observations in yeast are taken into consideration (38, 45). In those studies, degradation of substrates with misfolded intramembrane domains such as Hmg2p did not require Usa1p, the yeast equivalent of dHerp. Degradation of Hmg2p was also unaffected by the absence of Der1, for which Usa1p acts as an adaptor to the Hrd1 complex (38). The requirement of dHerp, but not the Drosophila Derlin proteins (dDerlin-1 and dDerlin-2/3) in degradation of reductase (see Fig. 6, B and C) indicates a role for dHerp in S2 cells that is distinct from recruitment of Derlins to the Hrd1 complex. This notion is consistent with the recent finding that mammalian Herp binds to a family of proteins called ubiquilins (46). Ubiquilins contain an N-terminal ubiquitin-like domain that binds to proteasomes and a C-terminal ubiquitin-associated domain that recognizes polyubiquitin chains. The yeast equivalent of ubiquilins, Dsk2, is known to play a key role in ERAD by guiding substrates to the proteasome (47, 48). Determining whether dHerp mediates reductase degradation in S2 cells through a mechanism involving Drosophila ubiquitin will be a goal of future studies.

Based on the current results, a working model for reductase degradation in S2 cells can be proposed that predicts that Insigs nucleate a dSel1-reductase interaction. This interaction results in the transfer of reductase to the dHrd1 complex for ubiquitination and subsequent degradation. An important feature of this model is the role of Insig as an intermediary protein that bridges reductase (the ERAD substrate) to the ubiquitin ligase complex. Thus, mammalian reductase should bind to dHrd1 in an Insig-dependent, sterol-induced fashion and the reductase-Insig complex should bind to dHrd1 through a dSel1-mediated reaction. Although Insig-1 co-immunoprecipitates with overexpressed dHrd1 in a specific manner (see Fig. 4C), we have been unable to demonstrate if this interaction requires the presence of dSel1 (data not shown). Moreover, attempts to demonstrate Insig-dependent binding of reductase to overexpressed dHrd1 have so far been unsuccessful. A likely explanation may be provided by the observation that overexpression of Hrd1 restores degradation of ERAD substrates in yeast lacking Hrd3 (40, 49), suggesting that the ubiquitin ligase has an intrinsic affinity for these substrates that is somehow enhanced by Hrd3. However, we must also consider alternative models for the role of dSel1 in reductase degradation. In addition to its requirement for Hrd1-mediated ubiquitination and degradation, Hrd3 also prevents autoubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of Hrd1 (49). Thus, the possibility exists that dSel1 stabilizes dHrd1 by preventing autoubiquitination so that the enzyme can interact with the sterol-dependent reductase-Insig complex. Future efforts employing RNAi-mediated knockdown and co-immunoprecipitation with antibodies against endogenous proteins are required to distinguish between these models and define interactions between reductase, Insigs, dSel1, and dHrd1.

In conclusion, the ability to reconstitute sterol-accelerated degradation of the membrane domain of hamster reductase in S2 cells provides a new tool to delineate the molecular mechanisms of the reaction. The current results suggest that a unique feature of Insigs is recognized by gp78 in mammalian cells and dHrd1 in Drosophila cells that allows bridging of reductase to these enzymes. Understanding how Insigs mediate selection and delivery of mammalian reductase to the dHrd1 complex in S2 cells should provide important insights into how Insigs arbitrate the gp78-mediated reaction in mammalian cells. Moreover, information gleaned from these studies will likely be applicable to the selection of similar types of substrates in both yeast and mammalian systems.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Michael S. Brown and Joseph L. Goldstein for continued encouragement and insightful advice. We also thank Tammy Dinh and Kristi Garland for excellent technical assistance, and Lisa Beatty, Dr. Krista Matthews, and Dr. Robert Rawson for help with tissue culture.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant HL20948 and the Perot Family Foundation.

A. D. Nguyen, S. H. Lee, A. Radhakrishnan, and R. A. DeBose, unpublished observations.

- HMG-CoA

- 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A

- dsRNA

- double-stranded RNA

- ER

- endoplasmic reticulum

- ERAD

- ER-associated degradation

- RNAi

- RNA interference

- SREBP

- sterol regulatory element-binding protein

- 25-HC

- 25-hydroxycholesterol

- pAc

- actin 5c promoter

- LPDS

- lipoprotein-deficient serum

- HI

- heat-inactivated

- FCS

- fetal calf serum

- PBS

- phosphate-buffered saline.

REFERENCES

- 1.Goldstein J. L., Brown M. S. (1990) Nature 343, 425–430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gil G., Faust J. R., Chin D. J., Goldstein J. L., Brown M. S. (1985) Cell 41, 249–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liscum L., Finer-Moore J., Stroud R. M., Luskey K. L., Brown M. S., Goldstein J. L. (1985) J. Biol. Chem. 260, 522–530 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roitelman J., Olender E. H., Bar-Nun S., Dunn W. A., Jr., Simoni R. D. (1992) J. Cell Biol. 117, 959–973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sever N., Yang T., Brown M. S., Goldstein J. L., DeBose-Boyd R. A. (2003) Mol. Cell 11, 25–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown M. S., Goldstein J. L. (1980) J. Lipid Res. 21, 505–517 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ravid T., Doolman R., Avner R., Harats D., Roitelman J. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 35840–35847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sever N., Song B. L., Yabe D., Goldstein J. L., Brown M. S., DeBose-Boyd R. A. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 52479–52490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee P. C., Nguyen A. D., Debose-Boyd R. A. (2007) J. Lipid Res. 48, 318–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang T., Espenshade P. J., Wright M. E., Yabe D., Gong Y., Aebersold R., Goldstein J. L., Brown M. S. (2002) Cell 110, 489–500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldstein J. L., DeBose-Boyd R. A., Brown M. S. (2006) Cell 124, 35–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nohturfft A., Brown M. S., Goldstein J. L. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 17243–17250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Horton J. D., Shah N. A., Warrington J. A., Anderson N. N., Park S. W., Brown M. S., Goldstein J. L. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 12027–12032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Horton J. D., Goldstein J. L., Brown M. S. (2002) Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol. 67, 491–498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DeBose-Boyd R. A., Brown M. S., Li W. P., Nohturfft A., Goldstein J. L., Espenshade P. J. (1999) Cell 99, 703–712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nohturfft A., Yabe D., Goldstein J. L., Brown M. S., Espenshade P. J. (2000) Cell 102, 315–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dobrosotskaya I. Y., Goldstein J. L., Brown M. S., Rawson R. B. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 35837–35843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clark A. J., Block K. (1959) J. Biol. Chem. 234, 2578–2582 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clayton R. B. (1964) J. Lipid Res. 15, 3–19 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Skalnik D. G., Narita H., Kent C., Simoni R. D. (1988) J. Biol. Chem. 263, 6836–6841 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hannah V. C., Ou J., Luong A., Goldstein J. L., Brown M. S. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 4365–4372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Seegmiller A. C., Dobrosotskaya I., Goldstein J. L., Ho Y. K., Brown M. S., Rawson R. B. (2002) Dev. Cell 2, 229–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liang G., Yang J., Horton J. D., Hammer R. E., Goldstein J. L., Brown M. S. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 9520–9528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sever N., Lee P. C., Song B. L., Rawson R. B., Debose-Boyd R. A. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 43136–43147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Correll C. C., Edwards P. A. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 633–638 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roitelman J., Simoni R. D. (1992) J. Biol. Chem. 267, 25264–25273 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakanishi M., Goldstein J. L., Brown M. S. (1988) J. Biol. Chem. 263, 8929–8937 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gertler F. B., Chiu C. Y., Richter-Mann L., Chin D. J. (1988) Mol. Cell. Biol. 8, 2713–2721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brown K., Havel C. M., Watson J. A. (1983) J. Biol. Chem. 258, 8512–8518 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee J. N., Ye J. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 45257–45265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Song B. L., Javitt N. B., DeBose-Boyd R. A. (2005) Cell Metabolism 1, 179–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lange Y., Ory D. S., Ye J., Lanier M. H., Hsu F. F., Steck T. L. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 1445–1455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roitelman J., Masson D., Avner R., Ammon-Zufferey C., Perez A., Guyon-Gellin Y., Bentzen C. L., Niesor E. J. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 6465–6473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Song B. L., Sever N., DeBose-Boyd R. A. (2005) Mol. Cell 19, 829–840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bays N. W., Gardner R. G., Seelig L. P., Joazeiro C. A., Hampton R. Y. (2001) Nat. Cell Biol. 3, 24–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Deak P. M., Wolf D. H. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 10663–10669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kikkert M., Doolman R., Dai M., Avner R., Hassink G., van Voorden S., Thanedar S., Roitelman J., Chau V., Wiertz E. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 3525–3534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carvalho P., Goder V., Rapoport T. A. (2006) Cell 126, 361–373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schulze A., Standera S., Buerger E., Kikkert M., van Voorden S., Wiertz E., Koning F., Kloetzel P. M., Seeger M. (2005) J. Mol. Biol. 354, 1021–1027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gardner R. G., Swarbrick G. M., Bays N. W., Cronin S. R., Wilhovsky S., Seelig L., Kim C., Hampton R. Y. (2000) J. Cell Biol. 151, 69–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Radhakrishnan A., Ikeda Y., Kwon H. J., Brown M. S., Goldstein J. L. (2007) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 104, 6511–6518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Radhakrishnan A., Sun L. P., Kwon H. J., Brown M. S., Goldstein J. L. (2004) Mol. Cell 15, 259–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hampton R. Y., Gardner R. G., Rine J. (1996) Mol. Biol. Cell 7, 2029–2044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Deleted in proof

- 45.Denic V., Quan E. M., Weissman J. S. (2006) Cell 126, 349–359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim T. Y., Kim E., Yoon S. K., Yoon J. B. (2008) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 369, 741–746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ko H. S., Uehara T., Tsuruma K., Nomura Y. (2004) FEBS Lett. 566, 110–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Walters K. J., Goh A. M., Wang Q., Wagner G., Howley P. M. (2004) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1695, 73–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bordallo J., Wolf D. H. (1999) FEBS Lett. 448, 244–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]