Abstract

The hypoxic response in humans is regulated by the hypoxia-inducible transcription factor system; inhibition of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) activity has potential for the treatment of cancer. Chetomin, a member of the epidithiodiketopiperazine (ETP) family of natural products, inhibits the interaction between HIF-α and the transcriptional coactivator p300. Structure-activity studies employing both natural and synthetic ETP derivatives reveal that only the structurally unique ETP core is required and sufficient to block the interaction of HIF-1α and p300. In support of both cell-based and animal work showing that the cytotoxic effect of ETPs is reduced by the addition of Zn2+ through an unknown mechanism, our mechanistic studies reveal that ETPs react with p300, causing zinc ion ejection. Cell studies with both natural and synthetic ETPs demonstrated a decrease in vascular endothelial growth factor and antiproliferative effects that were abrogated by zinc supplementation. The results have implications for the design of selective ETPs and for the interaction of ETPs with other zinc ion-binding protein targets involved in gene expression.

A major transcriptional activation system, involving HIF2 and the p300/CREB-binding protein (CBP) coactivators, coordinates cellular and physiological responses to hypoxia in animals (for review, see Ref. 1). The oxygen-sensing component of the HIF system is provided by oxygenases that catalyze the post-translational hydroxylation of the HIF α-subunit. HIF-α prolyl-hydroxylation signals for proteasomal degradation, whereas asparaginyl hydroxylation reduces HIF activity by blocking interaction of the HIF-1α C-terminal activation domain (C-TAD) with the cysteine histidine-rich domain 1 (CH1) of p300/TAZ1 (transcription adaptor zinc-binding domain) domain of CBP (2) (Fig. 1A). Because hypoxia is a general characteristic of solid tumors and HIF-regulated genes are linked to cancer progression, inhibition of HIF activity has therapeutic potential (for review, see Ref. 3).

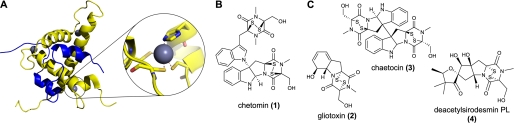

FIGURE 1.

HIF-1α-C-TAD and p300-CH1 interaction and naturally occurring ETPs. A, views from structures of the C-TAD of HIF-1α (amino acids 786–826, in blue) interacting with the CH1 of p300 (amino acids 323–423, in yellow). Protein Data Bank (PDB) ID code 1L3E (2), showing the location of the three zinc-binding sites. A close-up of one of the zinc-coordinating sites of CH1 showing His402, Cys406, Cys411, and Cys414 is shown. B, structure of chetomin. C, structures of the naturally occurring ETPs gliotoxin (2), chaetocin (3), and deacetylsirodesmin PL (4).

Although the C-TAD-CH1 interaction is tight, the observation that the addition of a single oxygen atom at Asn803 of HIF-1α (4) significantly reduces binding suggests that it is amenable to small molecule intervention. Evidence for this proposal came from the demonstration that a C-TAD-derived peptide reduces HIF activity in cells and attenuated tumor growth in a mouse xenograft model (5). Subsequently, Kung et al. (6) developed a C-TAD-CH1 interaction assay and screened >600,000 compounds that identified a single inhibitor, chetomin (1) (Fig. 1B), with a submicromolar IC50 in cellular assays, that possessed significant antitumor activity in mice. In addition to effectively reducing HIF-dependent transcription, chetomin also radiosensitizes hypoxic HT 1080 human fibrosarcoma cells (7).

Chetomin is one of the epidithiodiketopiperazine (ETP) family of fungal secondary metabolites and was initially identified as an antibiotic. ETPs contain a unique diketopiperazine scaffold with a bridge formed by two or more sulfur atoms; the disulfide link exists in an unusual conformation that induces significant torsional strain (8) (Fig. 1C). Chetomin is an interesting, promising lead structure, not only because of its unusual structure but because it is a rare example of a small molecule that disrupts a specific protein-protein interaction within a signaling pathway (6); there is also evidence that reduced forms of ETPs are selectively trapped in cells, a property that may be used to target hypoxic tumor cells (9). However, the molecular mechanism(s) of action of chetomin, and other ETPs, are unclear.

Recent attention has focused on the anticancer properties of ETPs. Many naturally occurring ETPs exert anticancer and other biological activities (for review, see Ref. 10). Gliotoxin (2) is reported to inhibit farnesyltransferase and geranylgeranyltransferase (11), and chaetocin (3) was reported recently to inhibit a histone methyl transferase (12). Chaetocin has also been shown to possess antimyeloma activity and is selective in killing myeloma cells over healthy cells (13). Despite the promising anticancer properties found thus far, there has been a longstanding lack of structure-activity relationship or data on the mechanism of action between ETPs and specific biological targets, in part because ETPs have historically been difficult to synthesize. Here we describe the synthesis, via a three-component procedure, of a set of ETP molecules that we used to carry out structure-activity analyses with the HIF-1α-C-TAD-p300-CH1 interaction.

Unexpectedly, the work with isolated proteins and cells reveals that the ETP disulfide core of the complex chetomin structure is itself sufficient for activity and that the mechanism of action involves disruption of the zinc-binding sites in the CH1 domain of p300. Although the zinc sites in p300 are known to be important for CH1 structure and binding of HIF-1α, they had not previously been recognized as a specific target for chetomin. To our knowledge, no other drug has been known to target this zinc interaction.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Synthesis: General Experimental

For full experimental details, see supplemental information. All reactions requiring the use of dry conditions were carried out under an atmosphere of nitrogen, and all glassware was predried in an oven (110 °C) or flame-dried and cooled under nitrogen prior to use. Stirring was by internal magnetic follower unless otherwise stated. All reactions were followed by TLC, and organic phases extracted were dried with anhydrous magnesium sulfate. Melting points were determined on a Gallenkamp melting point apparatus. Infrared spectra were recorded on a PerkinElmer Life Sciences 1605 FT-IR spectrophotometer using NaCl plates. 1H NMR (J values are reported to the nearest 0.5 Hz) and 13C NMR were recorded either on a Bruker AMX300 spectrometer or on a Bruker Avance 500 spectrometer. High resolution mass spectra were carried out at University College, London University. Mass spectra were carried out using either a Kratos MS89MS with Kratos DS90 software or a Jeol AX505W with a Jeol complement data system. Samples were ionized electronically, with an accelerating voltage of ∼6 kV or by low resolution fast atom bombardment in a thioglycerol matrix. High resolution fast atom bombardment was carried out at the University of London Intercollegate Research Scheme (ULIRS) mass spectrometry facility at the School of Pharmacy, University of London. Elemental analyses of compounds were carried out at the Chemistry Department, University College, London University.

C-TAD-CH1 Fluorescent Binding Assay and Screen

Inhibition of HIF-1α binding to p300 was measured, essentially as reported (6), by displacement of GST-p300-CH1323–423 from a synthetic biotinylated HIF-1α C-TAD786–826 (Peptide Protein Research Ltd., Fareham, UK) immobilized on 96-well streptavidin-coated plates. GST-CH1 was detected using a Europium-labeled antibody to GST (PerkinElmer Life Sciences). 48.5 nm HIF-1α C-TAD was used to coat plates for 5 h at room temperature. Plates were washed four times with TBST (50 mm Tris, 150 mm NaCl, 0.05% Tween 20, pH 8.0) buffer. 7.35 nm GST-CH1 was added with compounds or control (1% DMSO) in TBST with 5% BSA, 0.5 mm DTT, and 10 μm ZnCl2 and incubated overnight at 4 °C. Plates were washed four times with TBST, and Europium-labeled anti-GST (450 ng/ml) was added to plates in the buffer used for GST-CH1 addition, and after 2 h, plates were washed six times in TBST. DELFIA enhancement solution (PerkinElmer Life Sciences) was added before reading with a Victor3 plate reader (PerkinElmer Life Sciences), using the Europium setting under time-resolved fluorescence. Values were corrected for background and expressed as a percentage of controls (DMSO) to provide the percentage of CH1 binding. IC50 values were calculated using the Prism version 5.01 (GraphPad) graphing program using the non-linear regression equation log(inhibitor) versus response − variable slope.

Purification of His6-HIF-1α-C-TAD

A hexahistidine (His6)-tagged version of the HIF-1α C-TAD (His6-HIF-1α-C-TAD residues786–826) was prepared as described (14).

Purification of GST-CH1323–423

Recombinant N-terminal GST-tagged p300-CH1 (p300 residues323–423) was overexpressed and purified as described for GST-tagged p300302–423 (6) except for the following modifications; purification used a glutathione-Sepharose 4B (GE Healthcare) column (20 ml) with further purification by gel filtration chromatography using a Superdex 200 column (GE Healthcare). Protein was stored in TBST buffer with 10 μm ZnCl2 and 0.5 mm DTT, and protein concentration was determined by Bradford assay.

Depsipeptide

For crystal structure, see Ref. 15.

In Vitro Transcription/Translation and Co-immunoprecipitation of CH1-HIF-1α (6)

In vitro transcription/translation was performed using the TNT SP6 high-yield protein expression system (Promega) with pCMV HIF-1α-FLAG tag to produce full-length HIF-1α (supplemental information). GST-CH1 was purified as above. HIF-1α-FLAG and GST-CH1 were combined in the presence of compound or vehicle control (DMSO) in TBST with 10 μm ZnCl2, 0.5 mm DTT, and protease inhibitors (Complete protease inhibitor tablet, EDTA-free, Roche Applied Science). Mouse monoclonal anti-FLAG antibody (Sigma) was added with protein G-Sepharose and Fast Flow (Sigma) and then incubated for 1 h at room temperature. After 4× TBST washes, the samples were boiled in SDS-PAGE loading buffer, separated on 4–20% Novex Tris-glycine SDS-PAGE gels (Invitrogen), and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes, which were blocked in 3% nonfat milk (w/v) and probed with either rabbit anti-FLAG (1:2,000) and goat anti-rabbit-horseradish peroxidase (HRP) or anti-GST-HRP (1:1,666). Detection was performed using ECL Plus chemiluminescence (Amersham Biosciences). Films were scanned using a regular desktop scanner on the negative film setting.

Cell Culture

HCT 116 colorectal carcinoma cells were grown in McCoy's 5a medium modified supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, penicillin (50 IU/ml), streptomycin (50 μg/ml), and l-glutamine (2 mm), and Hep G2 hepatocellular carcinoma cells were grown in minimum Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, penicillin (50 IU/ml), streptomycin (50 μg/ml), and l-glutamine (2 mm), at 37 °C in 5% CO2 and 95% air. For hypoxic experiments, cells were placed in a modular incubator chamber flushed with 1% O2, 5% CO2, 94% N2.

Cell Viability Assays

HCT 116 cells were seeded overnight into white 96-well plates in 100 μl of medium at a concentration of 5 × 104 cells well−1, and Hep G2 cells were plated in the same manner at a concentration of 8 × 104 cells well−1. After overnight incubation at 37 °C, medium was removed and replaced with 200 μl of medium containing either drug or vehicle control. Plates were placed in either a normoxic incubator or a hypoxic chamber (Billups-Rothenberg) for 18 h. 100 μl of medium were removed for VEGF measurement, and cell viability was determined using the CellTiter-Blue cell viability reagent (Promega) according to the manufacturer's protocol. For the viability assessment in the presence of zinc, after the initial overnight incubation of cells at 37 °C, medium was removed and replaced with 100 μl of medium containing 150 μm ZnSO4 or ZnCl2. Cells were returned to 37 °C incubator for ∼90 min before adding 100 μl of medium containing 2× final concentration of drug or vehicle control. The final concentration of Zn2+ for incubation with ETPs was 75 μm. The viability assessment was carried out the same as for non-zinc-treated cells.

Cell Proliferation Assays

After viability readings were recorded, 20 μl of culture media containing 10 μm bromodeoxyuridine were added to the cells, and they were placed back in the 37 °C incubator for 18–24 h. Proliferation was measured using the cell proliferation enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, bromodeoxyuridine (colorimetric) (Roche Applied Science), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

VEGF Quantification

Tissue culture supernatant levels of VEGF were determined using a VEGF immunoassay (Calbiochem) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Removal of GST Tag from GST-p300-CH1 and Purification for ESI-MS Studies

After purification of GST-CH1323–423, the GST tag was removed by treatment with PreScission protease (Amersham Biosciences) treatment as specified by the manufacturer. CH1 was purified by size exclusion chromatography using a 300-ml Superdex 75 column (GE Healthcare).

Non-denaturing Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometric Assay (16–19)

As purified, CH1 was a mixture of apo and zinc complexes. To produce the fully tri-metallated form, CH1 was treated with 3 eq of Zn(II) and an excess of DTT. p300-CH1323–423 protein (GST tag-removed CH1, as described above) was desalted using a Bio-Spin 6 column (Bio-Rad) into 15 mm ammonium acetate (pH 7.5) to a final concentration of 20 μm. An aqueous solution of ZnSO4 · 7H2O (100 mm) was then diluted with MilliQ water to a final working concentrations of 100 μm. DTT was dissolved in MilliQ water at a concentration of 1 mm. ETPs were dissolved in DMSO (10 mm) and then diluted with ammonium acetate (15 mm, pH 7.5) to a concentration of 100 μm. The p300 protein (1.25 μl) was mixed with 3 eq of Zn(II) (0.75 μl), 20 eq of DTT (0.5 μl), and 20 eq of ETP (5 μl) and incubated for 30 min at room temperature prior to electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) analysis. Data were acquired using a quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometer (Q-TOF micro, Micromass, Altrincham) interfaced with a Nanomate (Advion Biosciences, Ithaca, NY) with a chip voltage of 1.70 kV and a delivery pressure 0.25 p.s.i. (1 p.s.i. = 6.81 kilopascals). The sample cone voltage was typically 200 V with a source temperature of 40 °C and with an acquisition/scan time of 10 s/1 s. Calibration and sample acquisition were performed in the positive ion mode in the range of 200–5,000 m/z. The pressure at the interface between the atmospheric source and the high vacuum region was fixed at 6.60 mbar. External instrument calibration was achieved by using sodium iodide. Data were processed with MASSLYNX 4.0 (Waters).

Epidithiodiketopiperazines

ETPs were stored frozen in DMSO. Chetomin and gliotoxin were purchased from Calbiochem; chaetocin was purchased from Sigma. Deacetylsirodesmin PL was a kind gift from Soledade Petras (University of Saskatchewan).

Software

Graphing was done using Prism version 5.01 (GraphPad) for curves, and IC50 determinations were generated from built-in functions. Molecular modeling was performed in PyMOL version 99 (20).

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using built-in GraphPad Prism version 5.01 functions, as specified. All statistical tests were two-sided, and the level of significance was set at p < 0.05. *, p < 0.05, **, p < 0.01, ***, p < 0.001 in the legends for Figs. 2–4, 8, and 9.

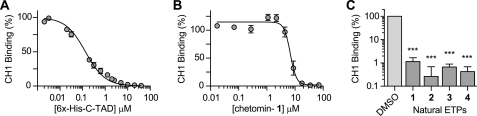

FIGURE 2.

Results from fluorescent binding assay. A, validation of C-TAD-CH1 fluorescent binding assay (6) by competitive inhibition. Biotin-C-TAD786–826 and GST-CH1 binding inhibited by increasing His6His-C-TAD775–826 (mean ± S.E. (error bars), n = 2–4 independent experiments run in duplicate). B, validation of C-TAD-CH1 fluorescent binding assay using chetomin. Chetomin was identified by Kung et al. (6) in a screen for compounds that block the CH1-C-TAD interaction. We also found that chetomin abrogates C-TAD and CH1 binding in a dose-dependent manner as reported (6) (mean ± S.E., n = 2–8 independent experiments run in duplicate) with a mean IC50 = 6.8 μm. C, in vitro inhibition of CH1 and C-TAD binding in the fluorescent binding assay by natural ETPs (mean ± S.E., n = 4–6 independent experiments). All four of the natural ETPs reduced CH1-C-TAD binding by ≥ 98.9% (ETP concentration tested at the approximately highest concentration soluble in 1% DMSO: 1 and 3 = 70 μm; 2 = 61 μm; 4 = 100 μm). Statistical analysis of differences between the means of three or more independent groups was evaluated by one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc test (versus DMSO control). There was no statistical significance between the activity of the different ETPs in the fluorescent binding assay. *, p < 0.05, **, p < 0.01, ***, p < 0.001.

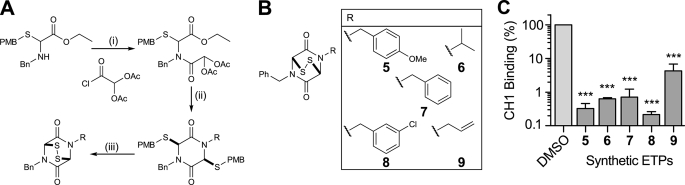

FIGURE 3.

Synthetic ETPs and activity against blocking C-TAD-CH1 interaction. A, outline route used for ETP synthesis. The syntheses of the dibenzyl-substituted ETP (7), the related dithiol (10) and the bis-methylated dithiol (12) were carried out following literature precedent (23, 24, 26, 27). PMB, p-methoxybenzyl. B, synthetic ETPs (racemic). C, in vitro inhibition of CH1 and C-TAD binding in fluorescent assay by synthetic ETPs. Mean ± S.E. (error bars) (n = 3–4, in duplicate) at 62.5 μm. Statistical analysis of synthetic ETPs was evaluated by one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc test. There was no statistical significance between the activity of the different ETPs. *, p < 0.05, **, p < 0.01, ***, p < 0.001.

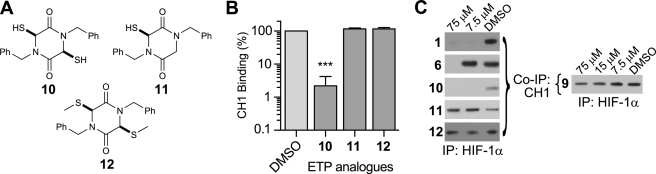

FIGURE 4.

Synthetic ETP analogues and activity against blocking C-TAD-CH1 interaction. A, synthetic ETP analogues (racemic). B, in vitro inhibition of CH1 and C-TAD binding in fluorescence assay by synthetic ETP analogues. Compounds possessing the ETP core in both oxidized (1–9) and reduced (10) form ablate CH1-C-TAD binding. Analogues possessing a single thiol (11) or methylated thiols (12) are inactive. (Mean ± S.E. (error bars), n = 2–3, at 62.5 μm.) Statistical analysis of synthetic ETPs was evaluated by one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc test. There was no statistical significance between the activity of the different ETPs. *, p < 0.05, **, p < 0.01, ***, p < 0.001. C, co-immunoprecipitation (IP) of FLAG-HIF-1α and bound GST-CH1 in the presence of ETPs. Shown is the amount of CH1 pulled down. Compounds with reduced/oxidized ETP core block the CH1-HIF-1α interaction, except for 9, indicating that selectivity of ETPs may be achievable. The single thiol analogue (11) and methylated thiols (12) analogue did not block the interaction. For the entire range of compounds and controls, see supplemental information.

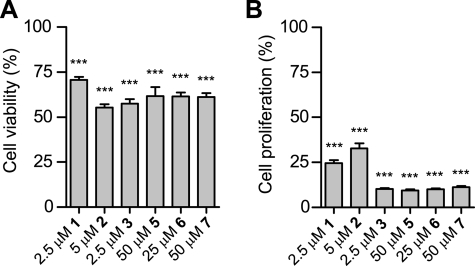

FIGURE 8.

Effect of both natural and synthetic ETPs on HCT116 cell viability (A) and proliferation (B) in normoxia (mean ± S.E. (error bars); viability: n ≥ 4; proliferation: n ≥ 3). Statistical analysis of differences between the means of three or more independent groups was evaluated by one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc test (versus DMSO control). See supplemental information for more supporting data. *, p < 0.05, **, p < 0.01, ***, p < 0.001.

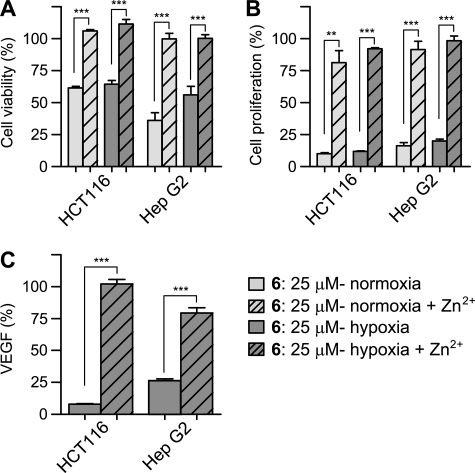

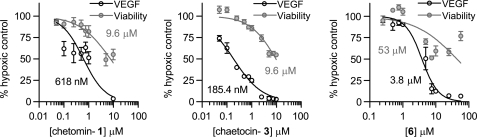

FIGURE 9.

Effect of representative synthetic ETP, compound 6, on HCT116 cell viability, proliferation, and VEGF secretion in the presence or absence of zinc (mean ± S.E. (error bars); viability: n ≥ 4; proliferation: n ≥ 3; VEGF n ≥ 3). HCT116 and Hep G2 cells were treated with 25 μm compound 6, with or without zinc supplementation for 18 h. A, viability of HCT116 and Hep G2 cells under normoxic and hypoxic (1% O2) conditions. The percentage of viable cells was considerably higher in zinc-treated cells versus non-zinc-treated. B, zinc supplementation increases proliferation to levels similar to the control, in both cell lines. C, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay quantification of secreted VEGF normalized to DMSO control in hypoxic HCT116 and Hep G2 cells. Zinc supplementation restores VEGF production in hypoxic HCT116 and Hep G2 cells. For data on other ETPs, see supplemental information. Statistical significance of differences between the means of ETP-treated samples and ETP-treated samples with zinc supplementation was evaluated by unpaired Student's t test. *, p < 0.05, **, p < 0.01, ***, p < 0.001.

RESULTS

Structure-activity Relationship of Chetomin in Disrupting HIF-1α and p300

To address the question of the structural features that are required for chetomin-mediated ablation of the HIF-1α-C-TAD and p300-CH1 interaction, an in vitro fluorescence binding assay was established using a biotinylated synthetic peptide of the C-TAD domain of HIF-1α and a recombinant GST-tagged protein containing the CH1 domain of p300 (amino acids 323–423) similarly to Kung et al. (6). The assay was verified by demonstration of competitive inhibition by the addition of His6-labeled HIF-1α-C-TAD775–826 (reported Kd of 123 nm (21); 134 nm under our assay conditions; Fig. 2A).

As reported (6), chetomin inhibited the C-TAD-CH1 interaction with an apparent IC50 of 6.8 μm under our conditions (Fig. 2B). As work with isolated proteins uses much higher levels of protein than those found in a cellular environment, in vitro IC50 values do not necessarily correspond to IC50 values in cellular studies.

Because of the biological activities associated with ETPs (10, 22), we then tested other naturally occurring ETPs, gliotoxin (2), chaetocin (3), and deacetylsirodesmin PL (4), as C-TAD-CH1-binding inhibitors. Unexpectedly, given the structural differences between these compounds and chetomin, all these ETPs effectively inhibited binding similarly to chetomin, blocking more than 98.9% of CH1-C-TAD binding at the given concentrations (Fig. 2C), suggesting that the ETP core itself is central to the observed activity.

Synthesis of ETPs and Activity against Blocking C-TAD-CH1 Binding

To test this hypothesis, we developed synthetic methodology employing tandem three-component reactions to give ETPs in an efficient four-step route (23) (Fig. 3A). This method enabled us to synthesize a set of ETPs, 5 to 9 (Fig. 3B) in which substituents on the diketopiperazine ring were varied.

As with the complex natural ETPs, the synthetic ETPs disrupted C-TAD and CH1 binding with IC50 values for the synthetic ETPs ranging from ∼6.4 to 52.3 μm (Fig. 3C, and see supplemental information for inhibition curves and IC50 values). As shown in Fig. 3C, at 62.5 μm, more than 95.7% of CH1-C-TAD binding was blocked. These results are important because they imply that a simple ETP core structure is sufficient to ablate the very tight binding between the C-TAD and CH1 domains.

Synthesis of ETP Analogues and in Vitro Activity

We then investigated the role of the ETP dithiol/disulfide group by preparing a dithiol analogue (10), an analogue containing one thiol (11), and an analogue with methylated thiols (12) (Fig. 4A) (24–26). The monothiodiketopiperazine (11) was obtained using a modification of the three-component approach used for ETP preparation (27). Except for 10, which blocked 97.8% of binding at 62.5 μm and likely underwent some disulfide formation under the aerobic reaction conditions, these compounds were completely inactive (Fig. 4B), revealing that a dithiol/disulfide is necessary for activity. The lack of activity of a disulfide-linked depsipeptide provides evidence for the requirement of a disulfide bridged/dithiol diketopiperazine for activity.

ETPs Block CH1 Binding to Full-length HIF-1α in Vitro

Because assays with HIF-1α and HIF-binding proteins (the HIF hydroxylases) have shown that binding affinities can vary significantly with the length of the HIF fragment (28–30), we tested whether the ETP compounds could prevent CH1 from binding to full-length HIF-1α. A co-immunoprecipitation assay using full-length HIF-1α and p300-CH1 demonstrated dose-dependent inhibition with both the natural and the synthetic ETPs (Fig. 4C, and see supplemental information for the entire range of compounds) as seen in the in vitro C-TAD-CH1 assay. However, compound 9, which was slightly less active than the other ETPs in the in vitro fluorescence assay (although not to statistical significance), failed to block CH1 binding to full-length HIF-1α at the same concentration as the other ETPs. This indicates that appropriate modifications can lead to a decrease in activity and that selectivity of ETPs might be achieved (Fig. 4C).

ETPs Cause Zinc Ejection from CH1 as Mechanism of Action

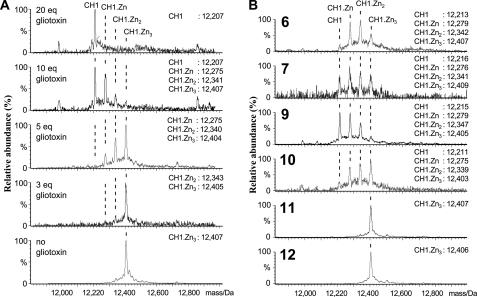

The molecular mechanism of action of the ETPs was then investigated by using non-denaturing ESI-MS to analyze ETP-induced modifications. We did not observe ETP-mediated modification of the C-TAD under our conditions (although it contains a cysteine (Cys800)). In contrast, we observed striking effects on p300-CH1 upon ETP treatment.

Upon treatment of CH1 with an excess of the natural ETPs (chetomin, chaetocin, gliotoxin, and deacetylsirodesmin PL), complete zinc ion release was observed from CH1. The results with chetomin and chaetocin were complex, probably because they contain two ETP cores, so we carried out further investigations with gliotoxin, which contains a single ETP core. When CH1 was treated with gliotoxin (5 eq), partial zinc ejection was observed (CH1·Zn-CH1·Zn2:CH1·Zn3 in an ∼1:3:4 ratio, respectively). In the presence of 10 eq of gliotoxin, the two main species observed were apo CH1 and CH1·Zn, in an ∼1:1 ratio. With 20 eq of gliotoxin, complete release of zinc gave apo CH1 as the only observed species (Fig. 5A).

FIGURE 5.

ETPs block the C-TAD-CH1 interaction by zinc ejection from CH1, demonstrated by ESI-MS. A, non-denaturing ESI-MS analyses on the effect of increasing amounts of gliotoxin (2) on zinc ion binding by CH1. B, non-denaturing electrospray ionization mass spectrometric analyses on the effect of various synthetic ETPs and ETP analogues on zinc ion binding by CH1. Note the variations in efficiency and note that the analogues 11 and 12, lacking the ETP core, do not cause zinc ion ejection.

Next we screened the synthetic ETPs for zinc ejection activity. Interestingly, and consistent with the structure-activity relationship studies, the results showed that 6, 7, and 10 caused partial zinc release (yielding apo CH1 and all three metallated species). In contrast, the monothiol (11) and thioether (12) analogues, all of which were inactive in the binding assays, did not cause zinc release, demonstrating that a dithiol/disulfide ETP core is essential for the activity (Fig. 5B).

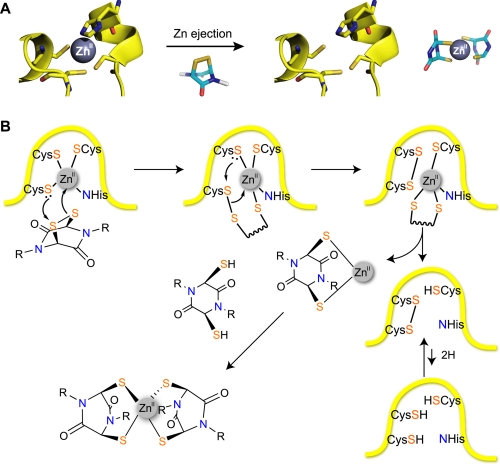

These results reveal that the ETP disulfide core structure is both sufficient and, within the set of tested compounds, necessary for inhibition of the HIF-1α-CH1 interaction. The mechanism of action involving modification of the zinc-binding sites on CH1 domain of p300 is supported by observations, employing NMR studies, that CH1 becomes less structured in the presence of chetomin (6). Consistent with the previous study of chetomin (6), we did not acquire evidence for irreversible covalent modification of CH1. We did, however, observe complexes between metallated, but not apo, forms of CH1, on treatment with ETPs, that were labile to increased sample cone voltages, consistent with the formation of protein-zinc-thiol(ate) complexes (16). We propose that ETPs cause zinc ion ejection via a mechanism related to that proposed for some known zinc-binding disrupting compounds (31) in which a zinc-binding cysteinyl thiol(ate) reacts with the torsionally strained disulfide of the ETP core to generate a transient protein-ETP disulfide (Fig. 6). This disulfide can then rearrange to form an intramolecular protein disulfide with consequent reduction in zinc ion affinity. The ejected zinc ion (or zinc ETP complex) can then complex with a second (reduced) ETP core to form a stable complex (17, 18). We therefore propose that from both the kinetic (lowering the energy barrier for zinc ejection) and the thermodynamic perspectives (formation of a stable zinc complex), the ETP core is particularly suited to the task of disrupting protein zinc-binding sites.

FIGURE 6.

Proposed mechanism of action of ETPs for modification of CH1 (31). A, summary of the mechanism of zinc ejection from p300-CH1. B, a zinc-coordinating cysteine thiol(ate) reacts with the disulfide of the ETP core to generate a transient protein-ETP disulfide. The disulfide then rearranges to form an intramolecular protein disulfide with consequent reduction in zinc ion affinity. The ejected zinc ion (or zinc ETP complex) can then complex with a second (reduced) ETP core to form a stable complex.

ETP Activity against Cell Lines

To test whether the various ETPs remained effective in blocking the HIF-1α-p300 interaction in the complex cellular environment, HCT116 (colorectal carcinoma) or Hep G2 (hepatocellular carcinoma) cells were treated with ETPs in normoxia and hypoxia. Because HIF regulates the expression of a gene array (1) and the CH1 domain of p300 is involved in the gene regulation of many other transcription factors (for review, see Ref. 32), the effects of inhibiting the HIF-1α-p300-CH1 interaction in cells are likely complex, making it difficult to use general markers, such as proliferation and viability, as a surrogate for the efficacy of the ETPs against HIF. We therefore used VEGF, a verified HIF target gene, to assess the effects of ETPs on HIF activity in cells. The levels of secreted VEGF were measured after ETP treatment, and the compounds demonstrating the most potent activity in decreasing VEGF independent of a nonspecific reduction in viability in both cell lines were chetomin, chaetocin, and 6 (Fig. 7). The effect of ETPs on general cell viability and proliferation were measured, and we found that chetomin, chaetocin, gliotoxin, and the synthetic ETPs 5, 6, and 7 possessed varying degrees of antiproliferative activity and reduced cell viability after a short 18-h incubation (Fig. 8 and supplemental Fig. 3).

FIGURE 7.

Effect of the three most potent ETPs on VEGF expression and viability of HCT116 cells after 18 h. Chetomin (left), chaetocin (middle), and compound 6 (right) all caused a decrease in secreted VEGF levels. The decrease in secreted VEGF was not directly due to nonspecific cytotoxicity of the ETPs as the percentage of viable cells was considerably higher than the percentage of decrease in VEGF levels at concentrations up to 1 μm chaetocin and chetomin and ∼2.5 μm compound 6 after 18 h. Only at concentrations greater than 10 μm did cell viability decrease to ∼50% in the 18-h time period. Longer incubations with the ETPs did lead to a further decrease in viability, see supplemental Fig. 4B. Data points are presented as mean ± S.E. (error bars) from independent experiments run in duplicate (chetomin: viability n = 2–7, VEGF n = 2–4), (chaetocin: viability n = 6–12, VEGF n = 2–6), and (compound 6: viability n = 3–7, VEGF n = 2–5).

It was noted that the effect of the ETPs on viability and proliferation was dependent upon cell density. The ETPs were more potent in reducing viability and proliferation at lower cell densities (see supplemental Fig. 4A). This observed effect is likely due to the accumulation of ETPs inside the cells by a redox-uptake mechanism, where the reduced form of the ETP is trapped within the cell, leading to very high intracellular concentrations (9). We also observed that ETPs would continue to decrease cell viability over time (18 h as compared with 72 h, see supplemental Fig. 4B) (33).

Zinc Ejection in Cells

To investigate the hypothesis that ETPs work via zinc ejection in a cellular environment, we supplemented cells with zinc 90 min before ETP treatment. We found that as compared with growth medium without zinc, there was substantially increased cell viability (34) and proliferation, as well as restored production of VEGF, in both Hep G2 cells and HCT116 cells (Fig. 9 and supplemental Figs. 5 and 6).

DISCUSSION

Our results have isolated the active pharmacophore in chetomin by revealing that the ETP core in itself was both necessary and sufficient for ablation of the HIF-p300 interaction. Using non-denaturing mass spectrometry, we investigated the mechanism of disruption and found that both the natural and the synthetic ETPs cause zinc ion ejection from the CH1 domain of p300. This is important from a medicinal perspective because most of the identified targets for ETPs are actually zinc-binding proteins (or have zinc-binding partners).

In a cancer cell-based model, the addition of zinc eliminated the antiproliferative effects of both natural and synthetic ETPs and drastically increased the percentage of viable cells. Most importantly, the addition of zinc restored the cell's production of VEGF in hypoxia, a protein that is under the direct transcriptional control of HIF.

The potentially lethal poisoning of grazing animals by the fungus Pithomyces chartarum and its treatment provide evidence that ETPs directly target zinc binding in animals (10). This fungus poses a serious agricultural problem in parts of the world that have ryegrass pastures and hot and/or humid weather (10). As a source of the sporidesmin family of ETPs, the fungus can cause liver toxicity and facial/udder eczema, a phenomenon that can be reversed by adding zinc ions to the diet, which is consistent with our proposed mechanism.

It is very likely that ETPs operate by more than one mechanism in cells (including redox cycling/producing reactive oxidizing species (10). However, it is striking that some, but not all (e.g. thioredoxin (35)), proposed ETP targets either are known zinc-binding proteins (e.g. farnesyltransferase/geranylgeranyltransferase-gliotoxin (11)) or are associated with zinc-binding proteins (histone methyl transferase-chaetocin (12)), suggesting that the disruption of zinc binding may be one of the potential generic mechanisms of ETP action and account, at least in part, for their toxicity (10).

It is notable that ETP biosynthesis itself in microorganisms is positively regulated by a zinc-containing transcription factor (36); it is possible that inhibition of this transcription factor by ETPs could provide a feedback loop. Further, nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB), which is known to bind the p300-CH1 domain for transcription (37), is a proposed target of gliotoxin (38). Because the p65 subunit of NF-κB subunit binds the CH1 domain of p300, disruption of the CH1 domain could account for all or part of the gliotoxin-mediated loss in activity of NF-κB.

Further work is needed to determine whether ETP-mediated disruption of the CH1 domain affects all CH1 interactions and whether ETPs disrupt interactions with other domains of p300, such as that with PGC-1α (39), and whether the stability of p300 is affected. Because of the multiple transcription factors that bind the CH1 domain, loss of CH1 structure and functionality could account for the extensive antitumor effects seen with chetomin in vivo (6), as seen previously with the overexpression of a CH1 polypeptide that decreased HIF transcription and led to a significant decrease in tumor size (5).

In addition to the potential consequences of zinc binding in vivo, other proposed targets of ETPs are likely to contribute to the anticancer effects: for example, the effects of chaetocin on the thioredoxin system (40), which itself is a proposed target for cancer drug development. Finally, the identification of the mechanism by which ETPs inhibit the HIF-1α-p300 interaction via zinc ejection now opens the way to the generation of ETP derivatives that are rationally targeted to specific protein targets.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Soledade Petras (University of Saskatchewan) for generously providing deacetylsirodesmin PL. We thank the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Cancer Research UK, The Wellcome Trust, and Biochemical and Biotechnology Research Council, for funding, Shandiz Shahbazi for assistance with cell culture and Dr. Douglas Price for advice and encouragement.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by the National Institutes of Health Grant Z01SC 006538. This work was also supported by grants from Cancer Research UK, The Wellcome Trust, and the Biochemical and Biotechnology Research Council. The structure-activity studies of the ETPs and HIF-1α/p300 inhibition were presented in a proffered abstract and oral presentation at the 99th AACR Annual Meeting, April 12–16, 2008, San Diego, CA (Cook, K. M., Hilton, S. T., Schofield, C. J., and Figg, W. F. (2008) Drug Design and Delivery: Oral Presentations: Proffered Abstracts, Abstr. 4149), available online at the AACR Meeting Abstractions Online web site.

The nucleotide sequence(s) reported in this paper has been submitted to the Gen-BankTM/EBI Data Bank with accession number(s) GQ340758.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. 1–6 and supplemental Schemes 1–3.

- HIF

- hypoxia-inducible factor

- HIF-1α

- α-subunit of hypoxia-inducible factor-1

- CBP

- CREB-binding protein

- CREB

- cAMP-response element-binding protein

- ETP

- epidithiodiketopiperazine

- C-TAD

- C-terminal activation domain of HIF-1α

- CH1

- cysteine/histidine-rich domain 1 of p300

- GST

- glutathione S-transferase

- TBST

- Tris-buffered saline, with Tween 20

- ESI-MS

- electrospray ionization mass spectrometry

- VEGF

- vascular endothelial growth factor

- DTT

- dithiothreitol

- ANOVA

- analysis of variance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hirota K., Semenza G. L. (2006) Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 59, 15–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Freedman S. J., Sun Z. Y., Poy F., Kung A. L., Livingston D. M., Wagner G., Eck M. J. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 5367–5372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaelin W. G., Jr., Ratcliffe P. J. (2008) Mol. Cell 30, 393–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lando D., Peet D. J., Whelan D. A., Gorman J. J., Whitelaw M. L. (2002) Science 295, 858–861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kung A. L., Wang S., Klco J. M., Kaelin W. G., Livingston D. M. (2000) Nat. Med. 6, 1335–1340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kung A. L., Zabludoff S. D., France D. S., Freedman S. J., Tanner E. A., Vieira A., Cornell-Kennon S., Lee J., Wang B., Wang J., Memmert K., Naegeli H. U., Petersen F., Eck M. J., Bair K. W., Wood A. W., Livingston D. M. (2004) Cancer Cell 6, 33–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Staab A., Loeffler J., Said H. M., Diehlmann D., Katzer A., Beyer M., Fleischer M., Schwab F., Baier K., Einsele H., Flentje M., Vordermark D. (2007) BMC Cancer 7, 213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hilton S. T., Motherwell W. B., Potier P., Pradet C., Selwood D. L. (2005) Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 15, 2239–2242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bernardo P. H., Brasch N., Chai C. L., Waring P. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 46549–46555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chai C. L., Waring P. (2000) Redox. Rep. 5, 257–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vigushin D. M., Mirsaidi N., Brooke G., Sun C., Pace P., Inman L., Moody C. J., Coombes R. C. (2004) Med. Oncol. 21, 21–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greiner D., Bonaldi T., Eskeland R., Roemer E., Imhof A. (2005) Nat. Chem. Biol. 1, 143–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Isham C. R., Tibodeau J. D., Jin W., Xu R., Timm M. M., Bible K. C. (2007) Blood 109, 2579–2588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coleman M. L., McDonough M. A., Hewitson K. S., Coles C., Mecinovic J., Edelmann M., Cook K. M., Cockman M. E., Lancaster D. E., Kessler B. M., Oldham N. J., Ratcliffe P. J., Schofield C. J. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 24027–24038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shigematsu N., Ueda H., Takase S., Tanaka H., Yamamoto K., Tada T. (1994) J. Antibiot. 47, 311–314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liénard B. M., Selevsek N., Oldham N. J., Schofield C. J. (2007) Chem. Med. Chem. 2, 175–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Woodcock J. C., Henderson W., Miles C. O. (2001) J. Inorg. Biochem. 85, 187–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Woodcock J. C., Henderson W., Miles C. O., Nicholson B. K. (2001) J. Inorg. Biochem. 84, 225–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Selevsek N., Tholey A., Heinzle E., Liénard B. M., Oldham N. J., Schofield C. J., Heinz U., Adolph H. W., Frère J. M. (2006) J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 17, 1000–1004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DeLano W. L. (2002) PyMOL version 99, the PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, DeLano Scientific LLC, San Carlos, CA [Google Scholar]

- 21.Freedman S. J., Sun Z. Y., Kung A. L., France D. S., Wagner G., Eck M. J. (2003) Nat. Struct. Biol. 10, 504–512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gardiner D. M., Waring P., Howlett B. J. (2005) Microbiology 151, 1021–1032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aliev A. E., Hilton S. T., Motherwell W. B., Selwood D. L. (2006) Tetrahedron Lett. 47, 2387–2390 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jiang H., Newcombe N., Sutton P., Lin Q. H., Mullbacher A., Waring P. (1993) Aust. J. Chem. 46, 1743–1754 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fukuyama T., Nakatsuka S. I., Kishi Y. (1981) Tetrahedron 37, 2045–2078 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seya H., Nozawa K., Nakajima S., Kawai K., Udagawa S. (1986) J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1, 109–116 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hilton S., Motherwell W., Selwood D. (2004) Synlett. 2609–2611 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dames S. A., Martinez-Yamout M., De Guzman R. N., Dyson H. J., Wright P. E. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 5271–5276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koivunen P., Hirsilä M., Günzler V., Kivirikko K. I., Myllyharju J. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 9899–9904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ehrismann D., Flashman E., Genn D. N., Mathioudakis N., Hewitson K. S., Ratcliffe P. J., Schofield C. J. (2007) Biochem. J. 401, 227–234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Loo J. A., Holler T. P., Sanchez J., Gogliotti R., Maloney L., Reily M. D. (1996) J. Med. Chem. 39, 4313–4320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goodman R. H., Smolik S. (2000) Genes Dev. 14, 1553–1577 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jordan T. W., Pedersen J. S. (1986) J. Cell Sci. 85, 33–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Duncan E. J., Thompson M. P., Phua S. H. (2005) Toxicol. Lett. 159, 164–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Choi H. S., Shim J. S., Kim J. A., Kang S. W., Kwon H. J. (2007) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 359, 523–528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fox E. M., Gardiner D. M., Keller N. P., Howlett B. J. (2008) Fungal. Genet. Biol. 45, 671–682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gerritsen M. E., Williams A. J., Neish A. S., Moore S., Shi Y., Collins T. (1997) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 2927–2932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pahl H. L., Krauss B., Schulze-Osthoff K., Decker T., Traenckner E. B., Vogt M., Myers C., Parks T., Waring P., Mühlbacher A., Czernilofsky A. P., Baeuerle P. A. (1996) J. Exp. Med. 183, 1829–1840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Puigserver P., Adelmant G., Wu Z., Fan M., Xu J., O'Malley B., Spiegelman B. M. (1999) Science 286, 1368–1371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tibodeau J., Benson L., Isham C., Owen W., Bible K. (2009) Antioxid. Redox. Signal. 11, 1097–1106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.