Abstract

Context

Epidemiologists and public health researchers are studying neighborhood’s effect on individual health. The health of older adults may be more influenced by their neighborhoods as a result of decreased mobility. However, research on neighborhood’s influence on older adults’ health, specifically, is limited.

Evidence acquisition

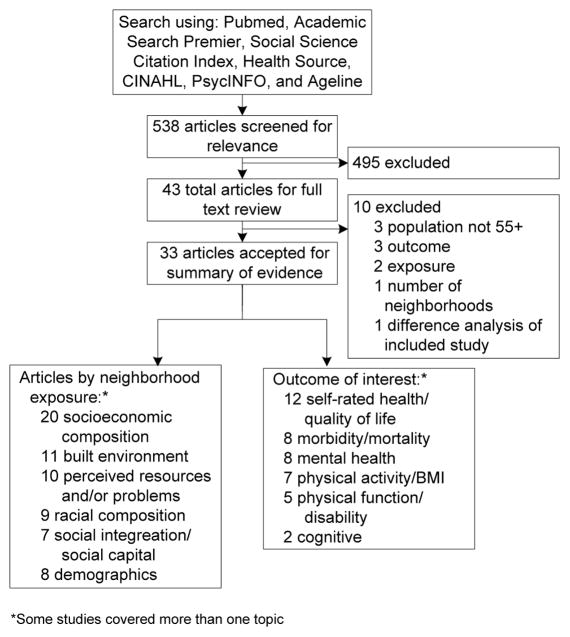

Recent studies on neighborhood and health for older adults were identified. Studies were identified through searches databases including PsychINFO, CINAHL, PubMed, Academic Search Premier, Ageline, Social Science Citation Index, and Health Source. Criteria for inclusion were: human studies; English language; study sample included adults aged ≥55 years; health outcomes including mental health, health behaviors, morbidity, and mortality; neighborhood as the primary exposure variable of interest; empirical research; and studies that included >=10 neighborhoods. Air pollution studies were excluded. Five hundred thirty-eight relevant articles were published 1997–2007; 33 of these articles met inclusion criteria.

Evidence synthesis

The measures of objective and perceived aspects of neighborhood were summarized. Neighborhood was primarily operationalized using census-defined boundaries. Measures of neighborhood were principally derived from objective sources of data; eight studies assessed perceived neighborhood alone or in combination with objective measures. Six categories of neighborhood characteristics were socioeconomic composition, racial composition, demographics, perceived resources and/or problems, physical environment, and social environment. The studies are primarily cross-sectional and use administrative data to characterize neighborhood.

Conclusions

These studies suggest that neighborhood environment is important for older adults’ health and functioning.

Background

A growing literature has reported associations between neighborhood and health behaviors and health status in the general population. As the literature expands, it is worthwhile to consider specific populations such as older adults. The world population is aging; the proportion of people age 65 and older is growing.1 In the U.S., the number of people aged 65 and older will more than double from 2000 to 2030 (from 35 to 71 million).2

The neighborhood-health literature highlights associations for four categories of health outcomes: overall mortality,3–6 chronic condition mortality or disease prevalence,4, 7–15 mental health outcomes,16–20 and health behaviors (e.g., diet, physical activity).21–23 Increasingly, the idea that neighborhoods affect health is accepted among researchers and policymakers. For example, PolicyLink, a national policy advocacy organization, recently created the Center for Health and Place and in 2007 released a report, “Why Place Matters: Building a Movement for Healthy Communities.” 24 “Unnatural Causes,” a U.S. public TV documentary series about health disparities that aired in the spring of 2008, featured a segment on place and health connections.

As neighborhood-health research has become more established, the mechanisms that connect place to health are gaining more attention. Such mechanisms can differ depending on the characteristics of a population. For example, presence of playgrounds or schools close to residences might increase physical activity for children, but not for older adults. Therefore, it is worthwhile to consider older adults specifically. Yet until recently, empirical research on the influence of neighborhoods on health among older adults was limited, despite conceptual models suggesting the importance of environmental determinants of health and well-being among older adults.25, 26

Environmental determinants may be accentuated among older adults due to combinations of: physical/mobility and mental decline associated with age, reduction in social networks and social support, and increased fragility.27, 28 In the U.S., close to 80% of people aged >65 years own their homes29 and as people age, mobility (i.e., getting around) becomes an issue. Mobility can refer to physical capacity to move around and also driving skills which influence number and location of activities.30 In a study of men and women aged ≥65 years, with mobility intact at baseline, 36% lost mobility (and 9% died without evidence of mobility loss prior to death) over 4 years.31 Another study found that about one third of high-functioning adults aged 70–74 years developed mobility limitations over 2 years.32 Concurrent with declines in functioning, the frequency of contact with social networks decreases with age.27, 33 The combination of declines in physical and cognitive functioning, increased discomfort with driving, and fewer contacts with social network members could lead to a greater dependence on the immediate residential neighborhood, an increased exposure to hazards and/or services or amenities.34

The purpose of this review was to summarize the current body of literature that investigated neighborhood effects for older adults. Neighborhood-health studies of general population samples have been reviewed35–37 and built environment and physical activity for older adults studies since 2004 have been reviewed.38 We are not aware of a review of studies for neighborhood health for older adults specifically including health variables beyond physical activity. Since policymakers are considering place-based strategies to improve health, special interest lay in understanding how the findings from this growing body of literature could inform the understanding of the mechanisms through which neighborhood influences health in older adults. To achieve these goals, all empirical research that investigated the role of neighborhood on health of older adults published between 1997 and 2007 was systematically identified. The quality of the methods was evaluated; the findings were assessed and interpreted as they could inform future research and policy. The use of theory to inform the conceptualization and subsequent measurement of neighborhood environment was also summarized.

Methods

Articles for possible inclusion were identified through a search of databases (see Figure 1), incorporating articles published from January 1, 1997 to December 31, 2007. The articles were identified articles using the MeSH term, “residence characteristics” and the PubMED search term, “neighborhood” in the title or abstract field. Prior to reviewing abstracts, the research team established inclusion and exclusion criteria. English-language empirical studies of physical and mental health outcomes (including health behaviors) of humans were included. For mental health, studies on diagnosable mental illness or mental disorders were included. Studies were excluded: if neighborhood was not the primary exposure variable or a key variable within an ecologic framework; with a population aged <55 years; or the sample included fewer than 10 neighborhoods. (While many statistics about older adults look at people aged ≥65 years based on the qualifying age for Medicare, a younger age cutpoint was selected recognizing that disease processes can be accelerated in disadvantaged populations.)

Figure 1.

Abstracts were reviewed by one reviewer (IY, YM, or LP). In cases where it could not be determined from the abstract whether or not the article met all inclusion criteria, the article was accepted for further review. Reference sections of articles meeting inclusion criteria were searched to identify additional articles for possible inclusion (yield = 39 articles). Of all 538 articles screened for relevance following initial abstract review, 496 were excluded because they did not meet all inclusion criteria, and 42 full-text articles were reviewed. Article selection flow is described in Figure 1. 33 articles remained. These 33 articles are summarized in Appendix A, available online at www.ajpm-online.net, with information about type of study (e.g., cross-sectional), the definition of neighborhood, neighborhood measures, primary outcome of interest, and key results.

The studies were assessed using a set of criteria created for the current study, informed by previous commentaries on neighborhood-health research.39–41 These commentaries and interest in examining this specific body of literature led to the creation of five categories: (1) the application of a stated theory or conceptual framework; (2) use of contextual or physical environment data either through databases of businesses and services or through direct observation; (3) taking into consideration length of time at an address in the analysis; (4) use of modeling to take clustering into account; and (5) for longitudinal studies, whether changes in the neighborhood over time were documented and taken into consideration.

Results

Identified Studies

The majority of the 33 studies (n=25) were cross-sectional, eight were longitudinal. The majority of the studies (n=26) were conducted in the U.S., seven were conducted in Europe or Australia. Neighborhood exposures were evaluated with respect to a wide variety of health outcomes, including mortality and morbidity, self-reported health or quality of life, mental health, cognition, disability, and physical activity/BMI. The size and scale of the studies varied. For example, 24 studies operationalized neighborhood using administrative boundaries, such as census or neighborhood association; among these the total number of included neighborhoods ranged from ten42 to 1,217 43 and the average n per neighborhood ranged from three44 to 207.45 The remaining studies used an individual-driven approach to characterizing neighborhood, focused on either individual perception of neighborhood characteristics of interest (e.g., neighborhood support)46–50 or objective information for a certain geographic radius surrounding an individual’s residence (e.g., physical environment characteristics within a quarter-mile radius of a participant).51–53

Measurement of Neighborhood Exposure

Each study was described in terms of six possible types of neighborhood exposure measures. These categories emerged from reading the articles and were in part guided by prior research experience.54–58 (1) Socioeconomic composition. Neighborhood is described by the composition of the people living in the area, using administrative (e.g., census) data. Examples of these variables include: (from U.S. census data) percentage of people who have incomes below 175% of the federal poverty level, median income in the administrative area (e.g., census tract), percentage of adults who are unemployed. (2) Racial composition. A subset of studies conducted in the U.S. investigated whether neighborhood-health associations differed based on the proportion of white, African American, or Latino residents in the area. (3) Demographics. Other demographic characteristics of interest included the age composition of an area and the geographic mobility of the residents (i.e., percentage of people who lived in the census tract for ≥5 years). (4) Perceived resources and/or problems. These neighborhood measures are derived from survey questions, which ask respondents about their perceptions of their environment (e.g., traffic, trash or litter, safety/crime, and access to or quality of commercial or public services). (5) Physical environment. Physical environment measures are the objective counterparts to the perceived resources and/or problems items. For example, telephone directory listings of commercial services are used to characterize health-related resources, and direct observations of traffic or trash characterize specific problems. Additionally, this category includes elements of neighborhood design, such as housing density and land-use diversity, hypothesized to be related to health primarily through behavior such as physical activity. (6) Social environment. Neighborhood social environment was operationalized as perceived social cohesion/support, collective efficacy, and neighborliness. In addition to perceived measures, neighborhood social environment was characterized using administrative data describing the availability of services that promote social organization or social interaction.59, 60

Results of the Systematic Review

Given the large number of exposures and outcomes considered in this body of literature, many exposure–outcome pairs are examined by only a single study. Additionally, publication bias favors the publication of significant associations, thus studies that demonstrate no association are less likely to be available for inclusion in this review of published studies. For these reasons, a quantitative analysis of the reviewed articles was not conducted; however, findings by exposure are briefly summarized below and notable findings are highlighted.

Socioeconomic composition

Neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage is associated with poor health,43–45, 59–69 but the association is not always straightforward. One study identified a significant interaction effect such that low-income older adults who lived in high-status neighborhoods had poorer physical functioning, more functional limitations, worse self-rated health, worse cognitive ability, and were more lonely than low-income adults who lived in low-status neighborhoods.70 This provocative interaction effect has also been reported in studies of neighborhood influences on general population samples, suggesting that in addition to material disadvantage associated with poorer neighborhoods, neighborhoods may influence health through psychosocial mechanisms (e.g., stress and lack of social support).34, 71, 72

Racial composition

There may be beneficial effect of ethnic enclaves for Latinos in terms of reduced morbidity and mortality, depressive symptoms, and self-rated health.65, 66, 73 In contrast, racial heterogeneity did not provide advantage for African Americans for depressive symptoms.60 The health benefits for Latinos living amongst other Latinos compared to Latinos who live in more heterogeneous settings is consistent with other findings that indicate that foreign-born Latinos have better health indicators than U.S.-born Latinos, and that health for foreign-born Latinos deteriorates with more years in the U.S..74, 75

Demographics

Living in a neighborhood with a higher density of older adults was associated with better mental health60 and a protective effect on the likelihood of reporting poor health.59 It has been proposed that “… older age concentration in a neighborhood [may be] a marker for better service provision targeted towards elders.” 59, p. S158).

Perceived environment resources and/or problems (from survey data)

The evidence for the influence of neighborhood problems on health outcomes was mixed. Neighborhood problems were significantly associated with self-rated health and symptoms47, 50 but results for physical function and mental health were mixed. There was no evidence of an association between neighborhood problems and physical activity in cross-sectional studies42, 76 nor in a longitudinal study.77 However, access to physical activity resources was associated with level of physical activity78 and change in physical activity.77

Physical environment (direct observations, administrative data)

Neighborhood design was primarily considered in relation to physical activity. Evidence consistently supported an association such that more accessible neighborhood design supported greater levels of walking.42,52,53,76,79

Social environment

While measures of neighborhood social environment were significantly associated with mortality and incidence of heart disease,45,48 evidence for an association with self-reported health,44,47,59 mental health, 60 physical function, 47 or physical activity76, 80 was inconsistent.

Application of Theory

The theoretic basis or model for the research question(s) in the included studies is summarized. Theoretic model refers to a previously described model (e.g., social–ecologic81,82) that provides a framework for hypotheses concerning relationships among variables. If authors provide general reasoning, short of a model, for how or why variables might be associated with their outcome(s) of interest, this is also noted.

The majority of studies did not explicitly name a guiding theory or model informing the research question and hypotheses. Three studies explicitly identified theoretic models: social–cognitive theory,76 collective efficacy theory,44 and environmental-press,83 focusing on one or two concepts within these large theories.

A number of studies provided general reasoning for how and why neighborhood might be associated with a particular health outcome. These studies investigated the effect of single neighborhood factors on health above and beyond (i.e., controlling for) individual factors. A typical example of this sort of study assessed whether neighborhood disadvantage influences health via differences in opportunity or access (for example, specific neighborhood problems, poor access to resources) based on current exposure. These studies are implicitly premised on a structural model that posits a main effect of neighborhood disadvantage beyond the compositional effects of individual characteristics.42,43,46,51–53,59–62,66,69,77,78,84,85

Robert and Li (2001) incorporated a life course perspective and evaluated a structural model of neighborhood influence on health at different stages across the life span. Other studies hypothesized that neighborhood characteristics may exacerbate the influence of individual-level factors (e.g., SES, number of comorbid conditions, disability) on health.45, 70, 83

Another group of studies posited that the primary influence of neighborhood on health was through heightened exposure to stress.48–50, 65, 68, 73 In this model, individual protective factors such as social support, mastery, and religious coping were hypothesized as buffers of the stressful influence of neighborhood problems and/or limited physical resources.

Quality Assessment

One third of the studies incorporated theory or used direct measures of neighborhood features and only 10 of the 33 accounted for length of residence in their analyses (see Table 1). Of the eight longitudinal studies, only one49 took into account any changes in the neighborhood environment during follow-up. In this study, neighborhood characteristics were measured at baseline and again after 4 years. Authors evaluated the association between neighborhood characteristics measured at both time points in relation to change in self-rated physical health. Notably, the investigators did not consider change between baseline and time two in relation to change in self-rated health.

Table 1.

Assessment of studies relating neighborhood context and health among older adults (n=33)

| Used Modeling to Take Neighborhood Clustering into Account | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |||

| Yes | Incorporated Theory | Cagney (2005)44 | Deeg (2005)70,a Krause (1998)49,b |

|

| No Theory | Kubzansky (2005)60 Li (2005)80 Patterson (2004) Subramanian (2006)59 |

Berke (2007) (AJPH)52,a Berke (2007) (JAGS)51 Michael (2006)42 |

||

| Direct Measures of Neighborhood Features | No | Incorporated Theory | Aneshensel (2007)43 Clarke (2005)83,a Fisher (2004)76 Robert (2006)68 |

Booth (2000)78 Bowling (2006)47 Schieman (2004)50,a |

| No Theory | Eschbach (2004)73 Hybels (2006)84 Li (2005)77 Merkin (2007)63 Ostir (2003)65 Patel (2003)66 Walters (2004)85 Wen (2005)45 Wight (2006)69 |

Balfour (2002)46 Breeze (2005)61 Bowling (2002)112 Chaix (2007)48 Diez Roux (2004)40 Nordstrom (2004)64 Robert (2001)67 |

||

The study accounted for the length of residence.

The study accounted for changes in the neighborhood over time.

Table 1 also highlights which of the studies used multilevel modeling to account for clustering within neighborhoods. It is not necessarily a higher quality study that uses this method. The method is possible if people were sampled within neighborhoods only and may not be appropriate even with sampling within neighborhoods, depending on sample size within the neighborhoods and the number of neighborhoods. Also, if a study used a convenience or clinic-based sample or geocoded the home addresses to a census tract, for example, multilevel modeling may not be appropriate.

Discussion

There is modest evidence that neighborhood significantly influences the health of older adults. However, the analytic approach of many of the studies limited their ability to identify specific neighborhood factors associated with health for older adults. While the study subjects of all of the studies discussed here were age 55 and older, the research questions and methods did not necessarily assess nor take into consideration characteristics specific to the older population, such as their physical mobility, ability to drive, habits around driving, or chronic conditions that might limit mobility. Theories of environmental aging suggest that as people age and their mobility declines, their residential neighborhood environment may become more relevant to their health and wellbeing. Yet the existing research does not consistently support this model. Future research should focus on the characteristics of neighborhoods that provide the most support and the most threat to older adults specifically. Finally in the U.S. specifically, the proportion of racial/ethnic minorities in the older adult population is steadily increasing. Based on studies included in this review and other neighborhood and health research, the racial/ethnic composition of one’s neighborhood is associated with health in different ways depending on the race/ethnicity of the study subject.65, 73, 86, 87 Below key findings of the reviewed literature and how future research can more specifically investigate how neighborhoods and more broadly, place, might affect health of older adults in the 21st century are elaborated.

Neighborhood-level SES was the strongest and most consistent predictor of a variety of health outcomes. This is both a noteworthy finding and it also reflects a limitation of this body of literature. It is noteworthy given that studies using individual-level measurements of SES have reported smaller gradients among older adults compared to younger populations. Measurement of SES is problematic among older adults because traditional markers – income, education, and occupation – have different meanings at older ages.88, 89 The finding that neighborhood SES is consistently associated with health in older adults confirms that the influence of deprivation persists to the oldest ages. Several studies of older adults have evaluated individual SES across the lifespan;90–93 results suggest a cumulative effect of poverty such that multiple periods of deprivation throughout the lifespan greatly increase the risk of poor health in late life. Only one study in this review specifically evaluated the influence of neighborhood SES across the lifespan.67 Additional studies incorporating measures of neighborhood across the lifespan are needed. The consistency of the effect of neighborhood SES on health of older people also reflects the fact that it is the most commonly studied neighborhood characteristics in the literature, perhaps due to the relative ease of obtaining these data from census and other administrative sources.

Very few studies directly measured neighborhood features or context that may be relevant for understanding the influence of neighborhoods on health. The studies that directly evaluate factors which are modifiable by intervention – specific problems or specific physical and social resources – are informative for developing policy solutions to improve health among older adults. The positive association between physical environment, perceived or objective, and physical activity behavior was fairly consistent. A majority of older adults are inactive 94, 95 and physical inactivity is linked to quality of life, morbidity, and mortality 96–99. Additional research is needed to determine if the physical environment is associated with these [downstream] health outcomes. Further, studies that measured perceived neighborhood physical or social resources and problems generally showed stronger associations than those using objective measures of resources and problems (see for example, Michael et al., 200655). This suggests that objective and perceived measures may be differentially related to health, and it would be useful to include perceived as well as objective measures in future studies. While policy solutions to objective neighborhood problems are perhaps more clear (e.g., improving walkability by adding sidewalks or clustering residential development near retail/employment), health promotion programs may successfully improve negative perceptions about neighborhood environment with some benefits for health.100

All of the studies reviewed here defined neighborhood as some designated geographic area in which the study participant lived, whether it was an administrative unit such as a census tract or a perceived area tied to the wording of a survey question. For frail older adults or older adults who have compromised mobility and minimal social ties to other people who can provide transportation support, the proximal environment could be more relevant. Older adults, however, are a highly heterogeneous group; many are very active and comfortably drive cars to varied destinations.101, 102 The idea that people engage in a variety of activities in multiple locations, often at some distance from their immediate neighborhoods, is not new to sociologists or geographers.103, 104 Incorporating these concepts into future research would permit researchers to delve deeper into the linkages between place and health for older adults.

Aging research has documented various racial/ethnic and SES disparities in health among older adults.105–107 One of the four primary goals of the U.S. National Institute on Aging’s strategic plan to address racial/ethnic disparities among older adults is to “advance understanding of the development and progression of disease and disability that contributes to health disparities in association with genetics, environmental/SES, mechanisms of disease, epidemiology and other risk factors.”108 It is valuable to do more studies with racially/ethnically diverse communities, perhaps incorporating community-based participatory research (CBPR) methods.109 CBPR methods include community members as experts. Including community members in the research team ensures the usefulness of the research to community residents. These methods could involve older neighborhood residents in identifying neighborhood factors and mechanisms which influence their health. This participatory approach would improve the a priori models linking neighborhood to health in this age group. Recent studies have shown success in including older community members in neighborhood research and advocacy efforts.55, 110 Fully including older community members as research partners will be valuable in creating neighborhood efficacy and sustaining advocacy efforts over time. It has been noted that older adults are in a perfect position to be advocates for the greater good of their communities due to the fact that they have “the benefit of life experience, the time to get things done, and the least to lose by sticking their necks out.”111

Some additional methodologic issues require discussion. Specifying a priori models and hypotheses for the association between (and among) specific neighborhood exposures and in relation to specific behavioral pathways to health outcome would allow for more rigorous evaluation of the putative associations. As mentioned in the quality assessment section, the majority of the evidence is from cross-sectional studies. Reverse causation is a possible explanation of positive associations in cross-sectional studies; specifically, poor health or health behaviors may be a cause rather than a result of neighborhood residence. Observed associations could also be spurious. Prospective studies are needed. Further, it is essential that studies evaluate neighborhoods as well as health prospectively so that the influence of change in neighborhoods on health may be more clearly articulated. Failure to account for length of residence may confound the results.

This review does have limitations. Some of the criteria for which articles to include were arbitrary. By including studies with 10 or more neighborhoods, case studies of single neighborhoods were excluded and qualitative studies were more likely to be excluded. These types of studies provide other valuable information about specific neighborhoods and are able to take into consideration local history and culture. The search criteria prioritized specificity at the cost of sensitivity. If neighborhood was not the primary exposure variable, the study was excluded possibly overlooking studies in which neighborhood might have had a strong but unanticipated effect. It is suspected that these studies would be cross-sectional, not contributing to the current gap in longitudinal studies. Another limitation is that a specific set of literature databases were searched. The Web of Science was not searched. It is possible that articles may have missed by not including it as one of the databases. Reference lists of included articles were reviewed to identify additional articles potentially missed by the database search. Finally, the age criterion of studies that featured adults aged ≥55 years precludes including studies that included a sample with wider age spans and also compared how neighborhood might be associated differently by age category.

Conclusion

This literature review provides limited support that neighborhood environment is a primary influence on older adults’ health and functioning. These results highlight the need for additional hypothesis-driven research based on models linking specific neighborhood exposure to health outcomes in older adults. New methods are needed to define “activity spaces”104 that are relevant to older adults and integrate direct measurement of these spaces into research. Further, relevant neighborhood exposures should be more consistently incorporated into health disparities research among older adults and use of innovative methods (e.g., CBPR) may enhance the usefulness of the research with this population.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Aleksandra Sumic for her assistance. We thank Rachel Gold, Sue Kim, Barbara Laraia, Elizabeth Smith, and Amy D. Sullivan for comments on earlier drafts.

Footnotes

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs. World Population Ageing 2007. Department of Economic and Social Affairs PD, ed; UN: 2007. p. 516. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bureau USC. [Accessed October 3, 2006];State and County QuickFacts. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yen IH, Kaplan GA. Neighborhood social environment and risk of death: multilevel evidence from the Alameda County Study. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1999;149(10):898–907. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borrell LN, Diez Roux AV, Rose K, Catellier D, Clark BL. Neighbourhood characteristics and mortality in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Int J Epidemiol. 2004 Apr;33(2):398–407. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Winkleby M, Cubbin C, Ahn D. Excess Mortality among Low SES People Living in High SES Neighborhoods: Results of a 17-Year Follow-up Study American. Journal of Public Health. in press. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Winkleby MA, Cubbin C. Influence of individual and neighbourhood socioeconomic status on mortality among black, Mexican-American, and white women and men in the United States. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003 Jun;57(6):444–452. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.6.444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diez-Roux AV, Nieto FJ, Muntaner C, et al. Neighborhood environments and coronary heart disease: a multilevel analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 1997 Jul 1;146(1):48–63. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.LeClere FB, Rogers RG, Peters K. Neighborhood social context and racial differences in women’s heart disease mortality. J Health Soc Behav. 1998 Jun;39(2):91–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davey Smith G, Hart C, Watt G, Hole D, Hawthorne V. Individual social class, area-based deprivation, cardiovascular disease risk factors, and mortality: the Renfrew and Paisley Study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1998 Jun;52(6):399–405. doi: 10.1136/jech.52.6.399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diez Roux AV, Merkin SS, Arnett D, et al. Neighborhood of residence and incidence of coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2001 Jul 12;345(2):99–106. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200107123450205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cubbin C, Hadden WC, Winkleby MA. Neighborhood context and cardiovascular disease risk factors: the contribution of material deprivation. Ethn Dis. 2001 Fall;11(4):687–700. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reijneveld SA. Neighbourhood socioeconomic context and self reported health and smoking: a secondary analysis of data on seven cities. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2002 Dec;56(12):935–942. doi: 10.1136/jech.56.12.935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sundquist K, Winkleby M, Ahlen H, Johansson SE. Neighborhood socioeconomic environment and incidence of coronary heart disease: a follow-up study of 25,319 women and men in Sweden. Am J Epidemiol. 2004 Apr 1;159(7):655–662. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sundquist K, Malmstrom M, Johansson SE. Neighbourhood deprivation and incidence of coronary heart disease: a multilevel study of 2.6 million women and men in Sweden. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2004 Jan;58(1):71–77. doi: 10.1136/jech.58.1.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cubbin C, Winkleby MA. Protective and harmful effects of neighborhood-level deprivation on individual-level health knowledge, behavior changes, and risk of coronary heart disease. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2005;162(6):1–10. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Galea S, Ahern J, Nandi A, Tracy M, Beard J, Vlahov D. Urban neighborhood poverty and the incidence of depression in a population-based cohort study. Ann Epidemiol. 2007 Mar;17(3):171–179. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2006.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gary TL, Stark SA, Laveist TA. Neighborhood characteristics and mental health among African Americans and whites living in a racially integrated urban community. Health Place. 2006 Aug 10; doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lofors J, Sundquist K. Low-linking social capital as a predictor of mental disorders: a cohort study of 4.5 million Swedes. Soc Sci Med. 2007 Jan;64(1):21–34. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Truong KD, Ma S. A systematic review of relations between neighborhoods and mental health. J Ment Health Policy Econ. 2006 Sep;9(3):137–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sundquist K, Ahlen H. Neighbourhood income and mental health: a multilevel follow-up study of psychiatric hospital admissions among 4.5 million women and men. Health Place. 2006 Dec;12(4):594–602. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2005.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Papas MA, Alberg AJ, Ewing R, Helzlsouer KJ, Gary TL, Klassen AC. The built environment and obesity. Epidemiol Rev. 2007;29:129–143. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxm009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saelens BE, Handy SL. Built environment correlates of walking: a review. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008 Jul;40(7 Suppl):S550–566. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31817c67a4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sallis JF, Glanz K. Physical activity and food environments: solutions to the obesity epidemic. Milbank Quarterly. 2009;87(1):123–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2009.00550.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bell J, Rubin V. Why Place Matters: Building a movement for healthy communities. Oakland: PolicyLink; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lawton MP. Environment and Aging. Albany: Center for the Study of Aging; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Glass TA, Balfour JL. Neighborhoods, aging, and functional limitations. In: Kawachi I, Berkman LF, editors. Neighborhoods and Health. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2003. pp. 303–334. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shaw BA, Krause N, Liang J, Bennett J. Tracking changes in social relations throughout late life. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2007 Mar;62(2):S90–99. doi: 10.1093/geronb/62.2.s90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johnson CL, Troll LE. Constraints and facilitators to friendships in late late life. Gerontologist. 1994 Feb;34(1):79–87. doi: 10.1093/geront/34.1.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lawler K. Coordinating housing and health care provision for America’s growing elderly population. Cambridge: Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University; Oct, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marottoli RA, de Leon CFM, Glass TA, Williams CS, Cooney LM, Jr, Berkman LF. Consequences of driving cessation: decreased out-of-home activity levels. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2000 Nov;55(6):S334–340. doi: 10.1093/geronb/55.6.s334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guralnik JM, LaCroix AZ, Abbott RD, et al. Maintaining mobility in late life. I. Demographic characteristics and chronic conditions. Am J Epidemiol. 1993 Apr 15;137(8):845–857. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Manton KG. A longitudinal study of functional change and mortality in the United States. J Gerontol. 1988 Sep;43(5):S153–161. doi: 10.1093/geronj/43.5.s153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Tilburg T. Losing and gaining in old age: changes in personal network size and social support in a four-year longitudinal study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1998 Nov;53(6):S313–323. doi: 10.1093/geronb/53b.6.s313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yen IH, Scherzer T, Cubbin C, Gonzalez A, Winkleby M. Women’s perceptions of neighborhood resources and hazards related to chronic disease risk factors: focus group results from economically diverse neighborhoods in a mid-sized U.S. city. American Journal of Health Promotion. 2007;22(2):98–106. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-22.2.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pickett KE, Pearl M. Multilevel analyses of neighbourhood socioeconomic context and health outcomes: a critical review. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2001 Feb;55(2):111–122. doi: 10.1136/jech.55.2.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ellen IG, Mijanovich T, Dillman K-N. Neighborhood effects on health: Exploring the links and assessing the evidence. Journal of Urban Affairs. 2001;3(4):391–408. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Owen N, Humpel N, Leslie E, Bauman A, Sallis JF. Understanding environmental influences on walking; Review and research agenda. Am J Prev Med. 2004 Jul;27(1):67–76. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saelens BE, Papadopoulos C. The importance of the built environment in older adults’ physical activity: A review of the literature. Washington State Journal of Public Health Practice. 2008;1(1):13–21. [Google Scholar]

- 39.O’Campo P. Invited commentary: Advancing theory and methods for multilevel models of residential neighborhoods and health. Am J Epidemiol. 2003 Jan 1;157(1):9–13. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Diez Roux AV. Estimating neighborhood health effects: the challenges of causal inference in a complex world. Soc Sci Med. 2004 May;58(10):1953–1960. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(03)00414-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Diez Roux AV. The study of group-level factors in epidemiology: rethinking variables, study designs, and analytical approaches. Epidemiol Rev. 2004;26:104–111. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxh006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Michael Y, Beard T, Choi D, Farquhar S, Carlson N. Measuring the influence of built neighborhood environments on walking in older adults. J Aging Phys Act. 2006 Jul;14(3):302–312. doi: 10.1123/japa.14.3.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aneshensel CS, Wight RG, Miller-Martinez D, Botticello AL, Karlamangla AS, Seeman TE. Urban neighborhoods and depressive symptoms among older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2007 Jan;62(1):S52–59. doi: 10.1093/geronb/62.1.s52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cagney KA, Browning CR, Wen M. Racial disparities in self-rated health at older ages: what difference does the neighborhood make? J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2005 Jul;60(4):S181–190. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.4.s181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wen M, Christakis NA. Neighborhood effects on posthospitalization mortality: a population-based cohort study of the elderly in Chicago. Health Services Research. 2005;40(4):1108–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00398.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Balfour JL, Kaplan GA. Neighborhood environment and loss of physical function in older adults: evidence from the Alameda County Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2002 Mar 15;155(6):507–515. doi: 10.1093/aje/155.6.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bowling A, Barber J, Morris R, Ebrahim S. Do perceptions of neighbourhood environment influence health? Baseline findings from a British survey of aging. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006 Jun;60(6):476–483. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.039032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chaix B, Isacsson SO, Rastam L, Lindstrom M, Merlo J. Income change at retirement, neighbourhood-based social support, and ischaemic heart disease: results from the prospective cohort study “Men born in 1914”. Soc Sci Med. 2007 Feb;64(4):818–829. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Krause N. Neighborhood deterioration, religious coping, and changes in health during late life. Gerontologist. 1998 Dec;38(6):653–664. doi: 10.1093/geront/38.6.653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schieman S, Meersman SC. Neighborhood problems and health among older adults: received and donated social support and the sense of mastery as effect modifiers. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2004 Mar;59(2):S89–97. doi: 10.1093/geronb/59.2.s89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Berke EM, Gottlieb LM, Moudon AV, Larson EB. Protective association between neighborhood walkability and depression in older men. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007 Apr;55(4):526–533. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Berke EM, Koepsell TD, Moudon AV, Hoskins RE, Larson EB. Association of the built environment with physical activity and obesity in older persons. Am J Public Health. 2007 Mar;97(3):486–492. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.085837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Patterson PK, Chapman NJ. Urban form and older residents’ service use, walking, driving, quality of life, and neighborhood satisfaction. Am J Health Promot. 2004 Sep–Oct;19(1):45–52. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-19.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yen IH, Syme SL. The social environment and health: a discussion of the epidemiologic literature. Annu Rev Public Health. 1999;20:287–308. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.20.1.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Michael YL, Green MK, Farquhar SA. Neighborhood design and active aging. Health Place. 2006 Dec;12(4):734–740. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nagel CL, Carlson NE, Bosworth M, Michael YL. The Relation between Neighborhood Built Environment and Walking Activity among Older Adults. Am J Epidemiol. 2008 Jun 20; doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yen IH, Yelin EH, Katz P, Eisner MD, Blanc PD. Perceived neighborhood problems and quality of life, physical functioning, and depressive symptoms among adults with asthma. Am J Public Health. 2006 May;96(5):873–879. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.059253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Blanc PD, Yen IH, Chen H, et al. Area-level socio-economic status and health status among adults with asthma and rhinitis. Eur Respir J. 2006 Jan;27(1):85–94. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00061205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Subramanian SV, Kubzansky L, Berkman L, Fay M, Kawachi I. Neighborhood effects on the self-rated health of elders: uncovering the relative importance of structural and service-related neighborhood environments. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2006 May;61(3):S153–160. doi: 10.1093/geronb/61.3.s153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kubzansky LD, Subramanian SV, Kawachi I, Fay ME, Soobader MJ, Berkman LF. Neighborhood contextual influences on depressive symptoms in the elderly. Am J Epidemiol. 2005 Aug 1;162(3):253–260. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Breeze E, Jones DA, Wilkinson P, et al. Area deprivation, social class, and quality of life among people aged 75 years and over in Britain. Int J Epidemiol. 2005 Apr;34(2):276–283. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Diez Roux AV, Borrell LN, Haan M, Jackson SA, Schultz R. Neighbourhood environments and mortality in an elderly cohort: results from the cardiovascular health study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2004 Nov;58(11):917–923. doi: 10.1136/jech.2003.019596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Merkin SS, Roux AV, Coresh J, Fried LF, Jackson SA, Powe NR. Individual and neighborhood socioeconomic status and progressive chronic kidney disease in an elderly population: The Cardiovascular Health Study. Soc Sci Med. 2007 Aug;65(4):809–821. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nordstrom CK, Diez Roux AV, Jackson SA, Gardin JM. The association of personal and neighborhood socioeconomic indicators with subclinical cardiovascular disease in an elderly cohort. The cardiovascular health study. Soc Sci Med. 2004 Nov;59(10):2139–2147. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ostir GV, Eschbach K, Markides KS, Goodwin JS. Neighbourhood composition and depressive symptoms among older Mexican Americans. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003 Dec;57(12):987–992. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.12.987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Patel KV, Eschbach K, Rudkin LL, Peek MK, Markides KS. Neighborhood context and self-rated health in older Mexican Americans. Ann Epidemiol. 2003 Oct;13(9):620–628. doi: 10.1016/S1047-2797(03)00060-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Robert SA, Li LW. Age variation in the relationship between community socioeconomic status and adult health. Research on Aging. 2001;23:233–258. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Robert SA, Ruel E. Racial segregation and health disparities between black and white older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2006 Jul;61(4):S203–211. doi: 10.1093/geronb/61.4.s203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wight RG, Aneshensel CS, Miller-Martinez D, et al. Urban neighborhood context, educational attainment, and cognitive function among older adults. Am J Epidemiol. 2006 Jun 15;163(12):1071–1078. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Deeg DJ, Thomese G. Discrepancies between personal income and neighbourhood status: Effects on physical and mental health. European Journal of Ageing. 2005;2(2):98–108. doi: 10.1007/s10433-005-0027-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Winkleby M, Cubbin C, Ahn D. Effect of cross-level interaction between individual and neighborhood socioeconomic status on adult mortality rates. Am J Public Health. 2006 Dec;96(12):2145–2153. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.060970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Roos LL, Magoon J, Gupta S, Chateau D, Veugelers PJ. Socioeconomic determinants of mortality in two Canadian provinces: multilevel modelling and neighborhood context. Soc Sci Med. 2004 Oct;59(7):1435–1447. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Eschbach K, Ostir GV, Patel KV, Markides KS, Goodwin JS. Neighborhood context and mortality among older Mexican Americans: is there a barrio advantage? Am J Public Health. 2004 Oct;94(10):1807–1812. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.10.1807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Dey AN, Lucas JW. Physical and mental health characteristics of U.S. and foreign-born adults: UnitedStates, 1998–2003. 2003 Advance data from vital and health statistics: National Center for Health Statistics. 2006 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Minnis AM, Padian NS. Reproductive health differences among Latin American- and U.S.-born young women. J Urban Health. 2001 Dec;78(4):627–637. doi: 10.1093/jurban/78.4.627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Fisher KJ, Li F, Michael Y, Cleveland M. Neighborhood-level influences on physical activity among older adults: a multilevel analysis. J Aging Phys Act. 2004 Jan;12(1):45–63. doi: 10.1123/japa.12.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Li F, Fisher J, Brownson RC. A multilevel analysis of change in neighborhood walking activity in older adults. J Aging Phys Act. 2005 Apr;13(2):145–159. doi: 10.1123/japa.13.2.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Booth ML, Owen N, Bauman A, Clavisi O, Leslie E. Social–cognitive and perceived environment influences associated with physical activity in older Australians. Prev Med. 2000 Jul;31(1):15–22. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2000.0661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Li F, Fisher J. A Multilevel Path Analysis of the Relationship Between Physical Activity and Self-Rated Health in Older Adults. Journal of Physical Activity and Health. 2004;1(4):398–412. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Li F, Fisher KJ, Brownson RC, Bosworth M. Multilevel modelling of built environment characteristics related to neighbourhood walking activity in older adults. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005 Jul;59(7):558–564. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.028399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Krieger N. Epidemiology and the web of causation: has anyone seen the spider? Soc Sci Med. 1994 Oct;39(7):887–903. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90202-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sampson RJ, Morenoff J, Gannon-Rowley T. ASSESSING “NEIGHBORHOOD EFFECTS”: Social Processes and New Directions in Research. Annual Review of Sociology. 2002;28:443–478. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Clarke P, George LK. The role of the built environment in the disablement process. Am J Public Health. 2005 Nov;95(11):1933–1939. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.054494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hybels CF, Blazer DG, Pieper CF, et al. Sociodemographic characteristics of the neighborhood and depressive symptoms in older adults: using multilevel modeling in geriatric psychiatry. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006 Jun;14(6):498–506. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000194649.49784.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Walters K, Breeze E, Wilkinson P, Price GM, Bulpitt CJ, Fletcher A. Local area deprivation and urban–rural differences in anxiety and depression among people older than 75 years in Britain. Am J Public Health. 2004 Oct;94(10):1768–1774. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.10.1768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Acevedo-Garcia D. Zip code-level risk factors for tuberculosis: neighborhood environment and residential segregation in New Jersey, 1985–1992. Am J Public Health. 2001 May;91(5):734–741. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.5.734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Osypuk TL, Acevedo-Garcia D. Are racial disparities in preterm birth larger in hypersegregated areas? Am J Epidemiol. 2008 Jun 1;167(11):1295–1304. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Grundy E, Holt G. The socioeconomic status of older adults: how should we measure it in studies of health inequalities? J Epidemiol Community Health. 2001 Dec;55(12):895–904. doi: 10.1136/jech.55.12.895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.von dem Knesebeck O, Luschen G, Cockerham WC, Siegrist J. Socioeconomic status and health among the aged in the United States and Germany: a comparative cross-sectional study. Soc Sci Med. 2003 Nov;57(9):1643–1652. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(03)00020-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lynch JW, Kaplan GA, Shema SJ. Cumulative impact of sustained economic hardship on physical, cognitive, psychological, and social functioning. N Engl J Med. 1997 Dec 25;337(26):1889–1895. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199712253372606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kuh D, Hardy R, Langenberg C, Richards M, Wadsworth ME. Mortality in adults aged 26–54 years related to socioeconomic conditions in childhood and adulthood: post war birth cohort study. Bmj. 2002 Nov 9;325(7372):1076–1080. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7372.1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Turrell G, Lynch JW, Kaplan GA, et al. Socioeconomic position across the lifecourse and cognitive function in late middle age. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2002 Jan;57(1):S43–51. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.1.s43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Singh-Manoux A, Ferrie JE, Chandola T, Marmot M. Socioeconomic trajectories across the life course and health outcomes in midlife: evidence for the accumulation hypothesis? Int J Epidemiol. 2004 Oct;33(5):1072–1079. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Caspersen CJ, Pereira MA, Curran KM. Changes in physical activity patterns in the United States, by sex and cross-sectional age. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000 Sep;32(9):1601–1609. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200009000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Mokdad AH, Giles WH, Bowman BA, et al. Changes in health behaviors among older Americans, 1990 to 2000. Public Health Rep. 2004 May–Jun;119(3):356–361. doi: 10.1016/j.phr.2004.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Mazzeo RS, Cavanagh P, Evans WJ, et al. ACSM Position Stand: Exercise and Physical Activity for Older Adults. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 1998;30(6):992–1008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Sumic A, Michael YL, Carlson NE, Howieson DB, Kaye JA. Physical activity and the risk of dementia in oldest old. J Aging Health. 2007 Apr;19(2):242–259. doi: 10.1177/0898264307299299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Yaffe K, Barnes D, Nevitt M, Lui LY, Covinsky K. A prospective study of physical activity and cognitive decline in elderly women: women who walk. Arch Intern Med. 2001 Jul 23;161(14):1703–1708. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.14.1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Nelson ME, Rejeski WJ, Blair SN, et al. Physical activity and public health in older adults: recommendation from the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2007 Aug 28;116(9):1094–1105. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.185650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Humpel N, Marshall AL, Leslie E, Bauman A, Owen N. Changes in neighborhood walking are related to changes in perceptions of environmental attributes. Ann Behav Med. 2004 Feb;27(1):60–67. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2701_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Lyman SA, Ferguson ER, Braver, Williams OdiiprcafcTap AF. Injury Prevention. 2002;8:116–120. doi: 10.1136/ip.8.2.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Fain MJ. Should older drivers have to prove that they are able to drive? Arch Intern Med. 2003 Oct 13;163(18):2126–2128. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.18.2126. discussion 2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Matthews SA, Detwiler JE, Burton LM. Geoethnography: coupling geographic information analysis techniques with ethnographic methods in urban research. Cartographica. 2005;40:75–90. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Matthews SA. The salience of neighborhood: some lessons from sociology. Am J Prev Med. 2008 Mar;34(3):257–259. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Adler NE, Newman K. Socioeconomic disparities in health: pathways and policies. Inequality in education, income, and occupation exacerbates the gaps between the health “haves” and “have-nots”. Health Aff (Millwood) 2002 Mar–Apr;21(2):60–76. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.2.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Pamuk E, Makuc D, Heck K, Reuben C, Lochner K. Socioeconomic Status and Health Chartbook: Health, United States, 1998. Hyattsville: National Center for Health Statistics; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 107.House JS, Williams DR. Understanding and reducing socioeconomic and racial/ethnic disparities in health. In: Smedly B, Syme SL, editors. Promoting Health: Intervention Strategies from Social and Behavioral Research. Washington, D.C: National Academy of Sciences Press; 2000. pp. 81–124. [Google Scholar]

- 108.National Institute on Aging. [Accessed January 6, 2004]. 2004. Health Disparities Strategic Plan: Director’s message. pdf file. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Leung MW, Yen IH, Minkler M. Community-based participatory research: a promising approach for increasing epidemiology’s relevance in the 21st century. Int J Epidemiol. 2004 Jun;33(3):499–506. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Hooker SP, Cirill LA, Geraghty A. Evaluation of the Walkable Neighborhoods for Seniors Project in Sacramento County Health Promotion Practice. 2008 doi: 10.1177/1524839907307887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Kuhn M, Quinn L, Long C. No Stone Unturned: The Life and Times of Maggie Kuhn. 1. New York: Ballantine Books; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Bowling A, Banister D, Sutton S, Evans O, Windsor J. A multidimensional model of the quality of life in older age. Aging Ment Health. 2002 Nov;6(4):355–371. doi: 10.1080/1360786021000006983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.