Abstract

Background and purpose:

Glucocorticoids are highly effective in the therapy of inflammatory diseases. Their value, however, is limited by side effects. The discovery of the molecular mechanisms of the glucocorticoid receptor and the recognition that activation and repression of gene expression could be addressed separately opened the possibility of achieving improved safety profiles by the identification of ligands that predominantly induce repression. Here we report on ZK 245186, a novel, non-steroidal, low-molecular-weight, glucocorticoid receptor-selective agonist for the topical treatment of inflammatory dermatoses.

Experimental approach:

Pharmacological properties of ZK 245186 and reference compounds were studied in terms of their potential anti-inflammatory and side effects in functional bioassays in vitro and in rodent models in vivo.

Key results:

Anti-inflammatory activity of ZK 245186 was demonstrated in in vitro assays for inhibition of cytokine secretion and T cell proliferation. In vivo, using irritant contact dermatitis and T cell-mediated contact allergy models in mice and rats, ZK 245186 showed anti-inflammatory efficacy after topical application similar to the classical glucocorticoids, mometasone furoate and methylprednisolone aceponate. ZK 245186, however, exhibits a better safety profile with regard to growth inhibition and induction of skin atrophy after long-term topical application, thymocyte apoptosis, hyperglycaemia and hepatic tyrosine aminotransferase activity.

Conclusions and implications:

ZK 245186 is a potent anti-inflammatory compound with a lower potential for side effects, compared with classical glucocorticoids. It represents a promising drug candidate and is currently in clinical trials.

This article is part of a themed issue on Mediators and Receptors in the Resolution of Inflammation. To view this issue visit http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/journal/121548564/issueyear?year=2009

Keywords: drug discovery, glucocorticoid receptor, atopic dermatitis, skin atrophy, inflammation

Introduction

Glucocorticoids (GCs) are among the most effective drugs for the treatment of inflammatory diseases. Their era started with the discovery that cortisol was highly efficient in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (Hench et al., 1949). Tremendous efforts to develop more potent synthetic GCs were started thereafter. In the early 1950s, the introduction of hydrocortisone dramatically changed therapy in dermatology. Enthusiasm for topical GCs with an increased potency peaked in the 1960s and 1970s. However, this viewpoint soon changed as highly potent GCs, especially over long periods, were found to produce side effects that clearly limited their use for chronic treatment (Maibach and Wester, 1992).

To reduce the systemic side effects of topical GCs, development of new agents has focused on optimization of pharmacokinetic properties and a number of GCs conforming to pro- or soft drug principles have been designed (Bodor and Buchwald, 2006). While ‘soft drugs’ are compounds that undergo rapid hepatic deactivation after exerting their pharmacological effects at the site of disease (e.g. budesonide) (Bodor and Buchwald, 2006), ‘pro-drugs’ are activated locally by enzymes in the lung (e.g. ciclesonide) or in the skin [e.g. methylprednisolone aceponate (MPA)] and exhibit low systemic exposure. Especially in dermatology, the identification of GCs displaying preferentially local activity led to a significant improved effect/side effect ratio, the ‘therapeutic index’. For example, mometasone furoate (MF) and MPA potently inhibit pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines locally and are clinically highly effective, whereas systemic side effects are rare (Barton et al., 1991; Welker et al, 1996; O'Connell, 2003). Both MPA and MF are classified as medium-potent GCs based on their potency in the treatment of all forms of eczema. They display the best therapeutic indices and are currently accepted as gold standards of topical GC therapy in dermatological indications (Luger et al., 2004). Nonetheless, induction of skin atrophy continues to be a potential issue for topically applied GCs (Booth et al., 1982; Mills and Marks, 1993; Kimura and Doi, 1999). Depending on the disease or its severity, longer treatment duration, the use of more potent GCs or systemic application may become necessary. In such a case, the risk of systemic undesired effects increases. These are effects on the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis, hyperglycaemia (potentially leading to GC-induced diabetes), muscle atrophy, growth retardation in children and others (Gomez and Frost 1976; Nilsson and Gip 1979; Aggarwal et al., 1993; De Swert et al., 2004; Garrott and Walland 2004). Thus, there is a pressing need for better anti-inflammatory drugs, which are as effective as classical GCs but bear a lower risk for side effects.

A promising novel therapeutic approach is based on the better understanding of the various molecular mechanisms of the GC receptor (GR). The ligand-mediated activation of the GR induces conformational changes that in turn lead to translocation of the receptor from the cytosol into the nucleus where it modulates gene expression either positively (transactivation) or negatively (transrepression). Major anti-inflammatory effects of GCs are due to the GR-mediated repression of stimulus-induced pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, adhesion molecules and enzymes. In addition, the ligand-activated GR can also induce expression of proteins displaying anti-inflammatory activity, such as GC-induced leucine zipper (Berrebi et al., 2003), lipocortin-1/annexin-1 (Mizuno et al. 1997; Perretti and D'Acquisto, 2009) and MKP-1 (Kassel et al., 2001). On the other hand, prominent undesired effects, like diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, thymus atrophy, muscle atrophy, glaucoma induction, are dependent on GR-mediated activation of gene expression (see Schäcke et al., 2002; Miner et al., 2005). In particular, catabolic effects in liver or muscle are triggered by GR-dependent activation of enzymes, such as phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase and tyrosine aminotransferase (TAT) (see Schäcke et al., 2002). It has been shown in vitro (Heck et al., 1994) and in vivo (Reichardt et al., 1998) that repression activities of the GR could be separated from activation activities of the receptor. This discovery served as a valuable working hypothesis to search for novel synthetic GR ligands that should display a better therapeutic index than the known classical GCs. The concept was confirmed in studies using mice carrying a mutated GR (Reichardt et al., 2001). A point mutation within the GR led to a dimerization deficiency that in turn abolished the transactivation abilities of the receptor. Treatment of these mice with dexamethasone generated a similar anti-inflammatory response as in the wild-type animals (Reichardt et al., 2001). Although recent basic research in the GR field has discovered some limitations (see Schäcke et al., 2008), the transactivation/transrepression model has proven to be a valid tool for the discovery of GR ligands that have anti-inflammatory function but with impaired transactivation-mediated side effect potential. With this approach to search for compounds with so-called dissociated profiles, new GR ligands have been identified with a preference for repression over activation activities in vitro, including AL-438 (Coghlan et al., 2003), LGD-5552 (Lopez et al., 2008), ZK 216348 (Schäcke et al., 2004) and others (see Mohler et al., 2007; Schäcke et al., 2008). None of these compounds, however, has so far entered clinical development.

We have searched for a selective GR agonist particularly suited for local application. Such a compound is expected to show a favourable therapeutic index resulting primarily from its molecular action (i.e. dissociation between transactivation and transrepression) and a low systemic availability due to low metabolic stability and high systemic clearance. We screened many compounds using receptor binding assays followed by cellular in vitro tests for GR-mediated transactivation and transrepression and for anti-inflammatory activity as well as various animal models of cutaneous inflammation, GC-typical side effects and pharmacokinetic characterization. Here we report on the characterization of ZK 245186, which is currently in early clinical development for atopic dermatitis. To the best of our knowledge, it represents the most advanced dissociated GR ligand reported so far.

Methods

Binding and receptor selectivity

Receptor binding assays

Extracts from Sf9 cells, infected with recombinant baculovirus coding for the human GR, progesterone receptor (PR), androgen receptor (AR) or mineralocorticoid receptor (MR) were used for the receptor binding assays (Schäcke et al., 2004). All receptor nomenclature follows the ‘Guide to receptors and channels’ (Alexander et al., 2008).

For the binding assays for GR, PR, AR and MR [1,2,4,6,7-3H]dexamethasone (approximately 3.18 GBq·mmol−1, NEN) (∼20 nmol·L−1), [1,2,6,7-3H(N)]progesterone (approximately 3.7 GBq·mmol−1, NEN), [17a-methyl-3H]methyltrienolone (approximately 3.18 GBq·mmol−1, NEN) or D[1,2,6,7-3H(N)]aldosterone (approximately 2.81 GBq·mmol−1, NEN) respectively, SF9 cytosol (100–500 µg protein), test compounds and binding buffer (10 mmol·L−1 Tris/HCL pH 7.4, 1.5 mmol·L−1 EDTA, 10% glycerol) were mixed in a total volume of 50 µL and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. Specific binding was defined as the difference between binding of [1,2,4,6,7-3H]dexamethasone, [1,2,6,7-3H(N)]progesterone, [17a-methyl-3H]methyltrienolone and D[1,2,6,7-3H(N)]aldosterone in the absence and presence of 10 µmol·L−1 unlabelled dexamethasone, progesterone, metribolone or aldosterone respectively. After incubation, 50 µL of cold charcoal suspension was added for 5 min and the mixtures were transferred to microtiter filtration plates. The mixtures were filtered into Picoplates (Canberra Packard, Dreieich, Germany) and mixed with 200 µL Microszint-40 (Canberra Packard). The bound radioactivity was determined with a Packard Top Count plate reader. The concentration of test compound giving 50% inhibition of specific binding (IC50) was determined from Hill analysis of the binding curves.

Selectivity assays

The potential of the ZK 245186 SEGRA and competitor compounds to exhibit agonistic or antagonistic activity in oestrogen receptor α- (ERα-), PR-, AR- and MR-mediated transactivation assays was determined. Increasing concentrations of test compounds were added: (i) to MCF-7 cells stably transfected with a vit-tk luciferase reporter gene; (ii) to SK-N-MC cells stably co-transfected with the human PR and a mouse mammary tumour virus (MMTV)-luciferase reporter gene; (iii) to CV-1 cells transfected with the rat AR and an MMTV-luciferase reporter gene; and (iv) to COS-1 cells co-transfected with the human MR and a MMTV-luciferase reporter gene. Dose-dependent induction of reporter gene activity by test compounds via the respective nuclear receptors were determined and compared with the potency and efficacy of the reference estradiol (ERα), promegestone (PR), metribolone (AR) and aldosterone (MR). To test for antagonistic activity, the effects of ZK 245186 and competitor compounds on reporter gene activity stimulated by estradiol (ERα), promegestone (PR), metribolone (AR) or aldosterone (MR) were determined. Antagonistic potency and efficacy of test compounds in the respective transactivation experiments were compared with reference compounds: fulvestrant (ERα), mifepristone (PR), cyproterone acetate (AR) and the MR antagonist ZK 91587.

Anti-inflammatory/immunomodulatory activity in vitro (transrepression)

Inhibition of collagenase promoter activity

HeLa cells stably transfected with a luciferase reporter gene linked to the collagenase promoter were cultured for 24 h in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 3% charcoal absorbed foetal calf serum (FCS), 50 units·mL−1 penicillin and 50 µg·mL−1 streptomycin, 4 mmol·L−1 L-glutamine and 300 µg·mL−1 geneticin (all Invitrogen/Gibco Groningen, the Netherlands). Cells were then seeded onto 96-well dishes (1 × 104 cells per well). After 24 h, cells were incubated with inflammatory stimulus [10 ng·mL−1 12-o-tetradecanoylphorbol 13-acetate (TPA)] with or without increasing concentrations (1 pmol·L−1 to 1 µmol·L−1) of reference or test compounds. As negative control (unstimulated cells) cells were incubated with 0.1% dimethylsulphoxide (DMSO) and as positive control cells (stimulated cells) were incubated with 10 µg·mL−1 TPA plus 0.1% DMSO. After 18 h luciferase assay was carried out.

Inhibition of cytokine secretion in stimulated human primary cells

All blood cells were used with written consent of the donors in accordance with institutional ethical guidelines. Effects of compounds on monocytic secretion of IL-12p40 was determined after stimulation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from healthy donors with 10 ng·mL−1 lipopolysaccharide (Escherichia coli serotype 0127:B8; Sigma, Taufkirchen, Germany). Effects on interferon (IFN)-γ secretion were determined after PBMC stimulation with 10 µg·mL−1 of the mitogenic lectin, phytohemagglutinin. After 24 h incubation (37°C, 5% CO2), cytokine concentrations in supernatants of treated cells were determined using specific ELISA kits: IFN-γ and IL-12p40 ELISA (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, USA).

Inhibition of lymphocyte proliferation in mixed lymphocyte reaction

Human PBMCs obtained from healthy donors were isolated by centrifugation of heparinized blood on Histopaque-1077 (Sigma) and cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with FCS (10% v/v). For mixed leukocyte reaction (MLR), PBMC from one donor were incubated with 50 µg·mL−1 Mitomycin C for 30 min at 37°C followed by repeated washings with PBS and used as stimulator cells. PBMCs from an unrelated donor were used as responder cells and seeded (5 × 104 cells per well) together with Mitomycin C-treated stimulator PBMCs (1 × 105 cells per well) in 96-well round-bottom microtest plates (Costar). The cultures were set up in triplicate, compounds were added in concentrations as indicated in Figure 2 and plates were incubated at 37°C. On day 5 PBMCs were pulse-labelled with [methyl-3H]-thymidine (7.4 kBq per well) for 6 h and harvested on glass filters. [3H]-thymidine incorporation of the triplicate cultures was measured by liquid scintillation counts quantified by beta-plate scintigraphy (1450 Microbeta Trilux) (Zügel et al., 2002).

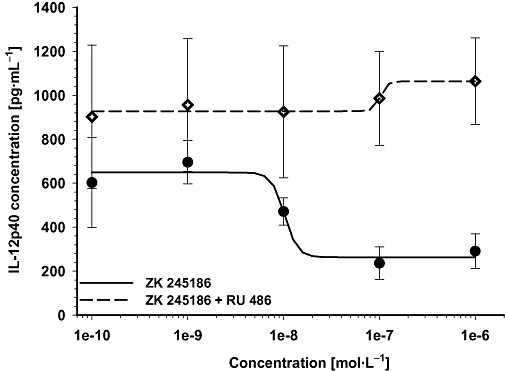

Figure 2.

Inhibition of IL-2 secretion by ZK 245186 is glucocorticoid receptor (GR)-mediated. The GR antagonist RU 486 (10 µmol·L−1) antagonizes IL-12p40 inhibition of ZK 245186. PBMCs were stimulated with lipopolysaccharide to induce IL-12p40 secretion. Treatment of cells with increasing concentrations of ZK 245186 (—) inhibited IL-12p40 secretion. Co-treatment with the GR antagonist RU 486 (----) totally prevented this inhibitory effect of ZK 245186.

In vitro surrogate marker for transactivation-mediated side effects

Induction of MMTV promoter activity

The MMTV promoter was linked to a luciferase reporter gene and HeLa cells were stably transfected with this construct. Cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 50 units of penicillin and 300 µg·mL−1 geneticin (all from Invitrogen/Gibco, Groningen, the Netherlands). To study transactivation activity of GR ligands, cells were cultured for 24 h in medium supplemented with 3% charcoal absorbed FCS. Cells were then seeded onto 96-well plates with 1 × 104 cells per well. After 24 h, cells were incubated with increasing concentrations of reference (dexamethasone) or test compounds. As negative control (unstimulated cells) cells were treated with 0.1% DMSO. Cells were incubated for 18 h with compounds, and then luciferase activity as a measure of GR activity was determined.

Induction of TAT activity

Induction of TAT by test compounds was determined in vitro using the human hepatoma cell line, HepG2. HepG2 cells were cultured in minimum essential medium containing 2 mmol·L−1 glutamax, 10% heat-inactivated FCS and 1% non-essential amino acids (all from Invitrogen/Gibco, Groningen, the Netherlands). To test induction of TAT by test compounds cells were seeded onto 96-well plates with 1 × 105 cells per well. After 24 h cells were incubated with test medium containing increasing concentrations of test and reference compounds. After 24 h cells were lysed and TAT activity was measured as absorption of the aromatic p-hydroxybenzaldehyde at 340 nm upon conversion of p-hydroxyphenylpyruvate.

Induction of apoptosis in the murine thymocyte cell line S49

To test the induction of apoptosis by established GCs and ZK 245186, cells of the murine thymocyte cell line S49 were co-incubated with increasing amounts of test or reference compound (dexamethasone). As negative controls, solvent (DMSO) was titrated in parallel to the volumes used in verum samples. The proportion of apoptotic cells was assessed after 72 and 96 h of incubation by staining with annexin V/propidium iodide and subsequent flow cytometric identification and quantification of early annexin V(+)/propidium iodide(−) and late apoptotic cells annexin V(+)/propidium iodide(−). Compound-mediated apoptosis was calculated by subtracting background values from corresponding serum values.

Determination of luciferase activity

100 µL Steady-Glo™ luciferase substrate (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) were added to cells, followed by an incubation for 10 min (in the dark). Then luciferase activity was measured with MicroBeta TriLux, Wallace 1450 (Perkin Elmer, Rodgau-Jügesheim, Germany) for 4 s per well as relative light units. All data (IC50 values and efficacies) are expressed as mean value ± standard deviation (SD).

Animal experiments

All animal studies were approved by the competent authority for labour protection, occupational health and technical safety for the state and city of Berlin, Germany, and were performed in accordance with the ethical guidelines of Bayer Schering Pharma AG. Animals were obtained from Charles River, Sulzfeld, Germany. NMRI mice (20–26 g), Wistar rats (140–160 g) and juvenile hr/hr rats (100–140 g) were housed according to institutional guidelines with access to food and water ad libitum.

Anti-inflammatory activity in vivo

Compounds were co-applied with croton oil or with dinitrofluorobenzene (DNFB) in ethanol containing 5% isopropylmyristate or acetone/olive oil 4/1 respectively.

Irritant contact dermatitis in mice and rats

Both ears of NMRI mice (10 per group) and Wistar rats (10 per group), respectively, were topically treated with compounds or vehicle that were dissolved in croton oil solution (10 µL of 1% for mice and 20 µL of 6.5% for rats). After 24 h, animals were killed and oedema was determined by measuring ear weight in mice or 10 mm diameter ear punch biopsy weight in rats as described earlier (Schäcke et al., 2004). As parameters for neutrophil infiltration, elastase activities were analysed in ear homogenate. The effect of ZK 245186 was compared with MPA and MF. Each experiment has been repeated twice.

Allergic contact dermatitis in mice and rats

NMRI mice (10 per treatment group) were sensitized in the skin of the flank with 25 µL of 0.5% DNFB at days 0 and 1. On day 5, mice were challenged by topical application of 20 µL of 0.3% DNFB as described earlier (Zügel et al., 2002). Wistar rats were sensitized with 75 µL of 0.5% DNFB at day 0. On day 5, rats were challenged by topical application of 40 µL 0.4% DNFB. Test or reference compounds (ZK 245186 and MPA respectively) were topically co-applied in up to four different concentrations (0.001%, 0.01%, 0.1% and 1%) with the hapten challenge. After 24 h, animals were killed to determine ear weight and elastase activity from ear homogenates as parameters for oedema and neutrophil infiltration. Each experiment has been repeated twice.

In vivo dissociation and side effect parameters

Determination of dissociated in vivo activity in mice as measured by its anti-inflammatory versus pro-diabetogenic effects

Determination of the induction of enzymes such as TAT may serve as a suitable surrogate marker for measuring the potential of a compound to act via transactivation in vivo. Two groups of mice (n = 10) were treated on the same day under identical conditions. All compounds were applied s.c., ZK 245186 and MPA in doses of 1, 3, 10, 30 mg·kg−1 body weight and MF in doses of 0.1, 0.3, 1 mg·kg−1 body weight. One group of mice was used in the croton oil model (main outcome parameter was inhibition of oedema formation) and in the second group of mice, TAT activity was determined from liver homogenates as described earlier (Schäcke et al., 2004). Induction of TAT activity was calculated in relation to vehicle-treated animals as baseline (-fold TAT induction). To determine the therapeutic window or the effect to side effect profile of the compounds, the per cent inhibition of oedema formation on the x-axis was plotted against TAT induction on the y-axis.

Glucose tolerance test following topical application of ZK 245186 onto rat skin

Hairless rats (hr/hr, n = 10) were treated topically with vehicle, ZK 245186 (0.1%), MPA (0.1%) or clobetasol propionate (0.1%). Prednisolone (3 mg·kg−1 body weight) p.o. served as a positive control to demonstrate GC-induced changes on the glucose metabolism. Treatment was performed once daily over four consecutive days. On day 5 after an overnight fasting period, 1 g glucose per kg body weight in 10 mL·kg−1 body weight was given orally and blood glucose concentrations were determined immediately before (baseline = 0 min) and shortly afterwards (30, 60, 120, 180 min) using glucose test strips and a blood sugar meter. In house experience with marketed topical GCs showed that compounds that only minimally increase blood glucose concentrations of topically treated hairless rats display low to no risk of altering glucose metabolism in humans after topical use, when applied according to the manufacturer's instructions (H. Wendt et al. unpubl. data).

Topical and systemic side effects following prolonged topical application

The variables measured were skin fold thickness, skin breaking strength (topical side effects) and total body weight as well as weights of thymus, spleen and the adrenal glands (systemic side effects after topical administration) as described earlier (Schäcke et al., 2004). The treatment regimen was daily application for 3 weeks.

Active compounds (ZK 245186, MPA and MF) or vehicle (EtOH containing 5% isopropylmyristate) were topically applied onto a skin area of 3 cm × 3 cm of juvenile, hr/hr rats (n = 10 per group) in equivalent concentrations for 19 days in a volume of 75 µL. Two different concentrations of the active compounds have been chosen: 3× ED50 determined in the croton oil rat model (for ZK 245186, 0.042%; for MPA, 0.035%; for MF, 0.0027%) and a concentration that results in ca. 80% inhibition of oedema formation in this model (for ZK 245186 and MPA, 0.1% and for MF, 0.01%).

Skin fold thickness and animal body weight were determined on days 1 (baseline), 5, 8, 12, 15 and 19. On day 20, animals were killed for determination of the weight of the following organs: thymus, spleen and adrenal glands. The correlation between the skin thinning effects in rodents and humans is well established (Kirby and Munro, 1976; van den Hoven et al., 1991; Woodbury and Kligman, 1992). In this paper, skin atrophy is defined as decrease of skin fold thickness. Body weight, spleen and thymus weight as well as the weight of the adrenal glands are used as measures of undesired systemic effects of topically applied GCs or similar compounds.

Statistical analyses

Competition factors, mean values and SD were determined using the commercial software Excel-97. IC50/EC50 values have been determined using DORA (Dose-Ratio Evaluation, version 1.4, copyright Schering AG 2000).

For comparison of in vitro activity data between the compounds, the Mann Whitney rank sum test was used for statistical analysis.

For all skin inflammation models in rodents, statistical analysis was performed with a modified Fieller's test, which was developed by Bayer Schering's Department of Biometrics based on the program sas System for Windows 6.12 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). To determine the inhibitory effect of anti-inflammatory compounds, the difference between the respective mean value of the positive controls and the mean value of the vehicle controls was set at 100%, and the percentile change by the test substance was estimated: % change = [(mean valuetreated group − mean valuepositive group)/(mean valuepositive group − mean valuecontrol group)] × 100 (Schottelius et al., 2002). To test whether the change caused by the treatment is different from zero, a 95% confidence interval was calculated under consideration of the variance of observations within the entire experiment. If the interval did not include zero, the hypothesis that there is no change was rejected at the level of α = 0.05.

Statistical differences regarding TAT enzyme activities were assessed by anova. Different distribution of variances was excluded using Barlett's test and data were analysed by anova with Dunnett's post-test using the program sisam.

In the glucose tolerance test, analysis of covariance was used on the log-transformed area under the curve (AUC), using the log of the baseline value as a covariate. Note that for the calculation of the AUCs, the trapezoidal rule was used.

Materials

ZK 245186, (R)-1,1,1-Trifluoro-4-(5-fluoro-2,3-dihydrobenzofuran-7-yl)-4-methyl-2-{[(2-methyl-5-quinolyl)amino]methyl}pentan-2-ol (melting point 186–188°C, logP 4.5 and molecular weight 462.48): MPA; MF, mifepristone, RU 486: progesterone, metribolone; aldosterone, oestradiol, fulvestrant, promegestone; cyproterone acetate; ZK 91587, 7α-methoxycarbonyl-15ß,16ß-methylene-3-oxo-17α-pregn-4-ene-21,17-carbolacetone (Nickisch et al., 1990) were all synthesized by the Medicinal Chemistry section of Bayer Schering Pharma AG. Dexamethasone and prednisolone were from Sigma. All compounds were dissolved in DMSO at a concentration of 1 × 10-2 mol·L−1 for in vitro characterization and stored at −20°C. Further dilutions were made in the appropriate cell culture media on the day of use. Final concentrations of DMSO did not exceed 0.1% and did not affect the assays used here.

Results

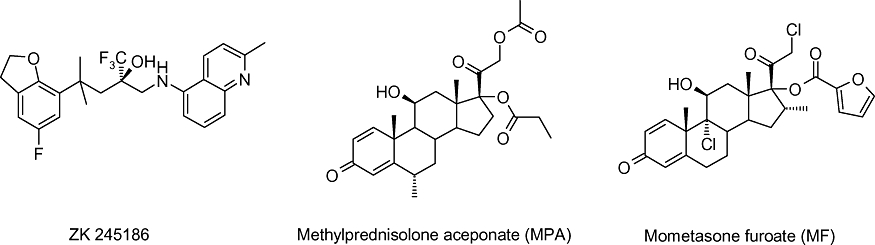

ZK 245186 has a non-steroid structure (Figure 1) and belongs to a group of topical selective GR agonists of the pentanolamine series.

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of ZK 245186, MPA and MF.

In the following pharmacological in vitro characterization, dexamethasone served as assay standard whereas the well-established topical GCs, MPA and MF, were used as reference compounds with which the novel GR ligand, ZK 245186, was compared. Data for the direct comparison of the reference compounds MPA and MF have been published by us recently (Mirshahpanah et al., 2007).

ZK 245186 is a highly GR-selective ligand

ZK 245186 binds with a high affinity and selectivity to the GR. In contrast, the binding profile of MF is not selective as reported previously. MF also binds to the MR and PR with high affinity (Table 1, and Mirshahpanah et al., 2007).

Table 1.

ZK 245186 is a highly selective GR ligand

| GR (dexamethasone) | PR (progesterone) | AR (metribolone) | MR (aldosterone) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZK 245186 | 1.9 ± 0.5 | 45 ± 11.8 | n.b. | n.b. |

| n = 6 | n = 6 | n = 6 | n = 6 | |

| MPA | 1.8 ± 0.2 | 50 ± 0.4 | n.b. | n.b. |

| n = 2 | n = 2 | n = 2 | n = 2 | |

| MF | 2.5 ± 0.6 | 1.7 ± 0.4 | 41.8 ± 12 | 1.6 ± 0.4 |

| n = 4 | n = 4 | n = 3 | n = 4 |

Binding profile of ZK 245186, MPA and MF to steroid hormone receptors was determined as described in the Methods. The competition factor (CF; defined as IC50 of test compound/IC50 of reference compound) values are shown. Reference compounds are given in parentheses. By definition, CF is 1.0 for standard compounds.

AR, androgen receptor; GR, glucocorticoid receptor; MF, mometasone furoate; MPA, methylprednisolone aceponate; MR, mineralocorticoid receptor; n.b., no binding; PR, progesterone receptor.

The receptor selectivity of ZK 245186 was confirmed using MMTV-luciferase activation assays (PR, AR, and MR) and a vitellogenin/thymidine kinase promoter (pvit-tk)-luciferase activation assay (ERα) (Table 2). ZK 245186 does not show significant activity via the ERα, PR, AR or MR. In contrast, as shown recently, MF behaves as a strong progestin and a partial agonist/antagonist in MR-dependent transactivation. MPA, although it binds with very low affinity to the PR, is much more selective for the GR in comparison with MF, which may represent an advantage for MPA (Mirshahpanah et al., 2007).

Table 2.

Functional effects on nuclear receptors

|

hERα |

hPR |

rAR |

hMR |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Agonism |

Antagonism |

Agonism |

Antagonism |

Agonism |

Antagonism |

Agonism |

Antagonism |

|||||||||

| EC50 (nmol·L−1) | Eff. (%) | IC50 (nmol·L−1) | Eff. (%) | EC50 (nmol·L−1) | Eff. (%) | IC50 (nmol·L−1) | Eff. (%) | EC50 (nmol·L−1) | Eff. (%) | IC50 (nmol·L−1) | Eff. (%) | EC50 (nmol·L−1) | Eff. (%) | IC50 (nmol·L−1) | Eff. (%) | |

| Reference | Estradiol | Fulvestrant | Promegestone | Mifepristone | Metribolone | Cyproterone acetate | Aldosterone | (ZK 91587) | ||||||||

| 0.038 ± 0.005 | 100 | 0.81 ± 0.025 | 100 | 0.024 ± 0.005 | 100 | 0.039 ± 0.005 | 100 | 0.28 ± 0.05 | 100 | 21.0 ± 5.5 | 100 | 0.026 ± 0.005 | 100 | 7.7 ± 0.8 | 100 | |

| n = 2 | n = 2 | n = 5 | n = 5 | n = 5 | n = 5 | n = 5 | n = 5 | |||||||||

| ZK 245186 | >1000 | – | >1000 | – | >1000 | – | 193 ± 158 | 65 ± 4 | >1000 | – | >1000 | – | >1000 | – | >1000 | 42 ± 4 @ 1 μmol·L−1* |

| N = 2 | n = 2 | n = 3 | n = 3 | n = 3 | n = 3 | n = 3 | n = 3 | |||||||||

ERα-, PR-, AR- and MR-dependent transactivation activity (agonist and antagonist) of ZK 245186, MPA and MF was determined as described in the Methods. EC50 values for agonistic and IC50 values for antagonistic activity are listed as mean values ± SD. Efficacies (Eff.) are shown as % of maximum effect of the respective reference. EC50 or IC50 values >1000 nmol·L−1 indicate no activity in the respective transactivation assay.

Correction added after online publication 6 October 2009: 1 mol·L was corrected to 1 μmol·L−1.

AR, androgen receptor; ERα, oestrogen receptor α; GR, glucocorticoid receptor; MR, mineralocorticoid receptor; PR, progesterone receptor.

In summary, ZK 245186 is highly selective at therapeutically effective concentrations, and has a better selectivity profile than the standard topical GCs tested.

In vitro pharmacology

ZK 245186 shows anti-inflammatory/immunomodulatory activity in cell lines and primary human cells

Collagenase promoter activation in response to an inflammatory stimulus is well known to be suppressed by a GR-mediated, DNA binding-independent, repression mechanism (König et al., 1992; Heck et al., 1994). The compound inhibited the TPA-triggered collagenase promoter activity with an IC50 of 1.6 nmol·L−1 and an efficacy of 89%. (Table 3).

Table 3.

Anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory activity (transrepression) in vitro

| n | IC50 (nmol·L−1) | P-value versus ZK 245186 | Efficacy (%) | P-value versus ZK 245186 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inhibition of collagenase promoter activity | |||||

| ZK 245186 | 6 | 1.6 ± 0.3 | 89 ± 4 | ||

| MPA | 5 | 9.3 ± 3.0 | 0.004 | 92 ± 7 | 0.329 |

| MF | 6 | 0.07 ± 0.02 | 0.002 | 96 ± 5 | 0.015 |

| Inhibition of IL-12p40 secretion | |||||

| ZK 245186 | 6 | 7.2 ± 2.0 | 83 ± 8 | ||

| MPA | 6 | 16.8 ± 9.3 | 0.041 | 98 ± 2 | 0.002 |

| MF | 5 | 0.1 ± 0.01 | 0.004 | 100 ± 3 | 0.004 |

| Inhibition of IFN-γ secretion | |||||

| ZK 245186 | 5 | 10.3 ± 7.8 | 88 ± 6 | ||

| MPA | 4 | 15.2 ± 11.1 | 0.73 | 88 ± 23 | 0.286 |

| MF | 4 | 0.08 ± 0.03 | 0.016 | 101 ± 1 | 0.016 |

| Inhibition of lymphocyte proliferation (MLR) | |||||

| ZK 245186 | 4 | 37.9 ± 23.2 | 99 ± 14 | ||

| MPA | 4 | 32.1 ± 11.5 | 1.000 | 102 ± 10 | 0.886 |

| MF | 4 | 0.15 ± 0.1 | 0.029 | 88 ± 12 | 0.486 |

Inhibition of collagenase promoter activity (in HeLa cells), lipopolysaccharide-induced IL-12p40 secretion (in human PBMCs) and phytohemagglutinin-induced IFN-γ secretion (in human PBMCs) by ZK 245186, MPA and MF were determined as described in the Methods. Inhibition of lymphocyte proliferation in 5 day MLR with allogeneic PBMCs by ZK 245186, MPA and MF were determined as described in the Methods. IC50 values are listed as mean value ± SD. Efficacies are shown as % of maximum effect of the reference dexamethasone at 1 µmol·L−1.

IFN, interferon; MF, mometasone furoate; MLR, mixed leukocyte reaction; MPA, methylprednisolone aceponate; PBMCs, peripheral blood mononuclear cells.

Figures in bold indicate that there is a significant difference.

Anti-inflammatory effects of GCs are partially mediated via the inhibition of lipopolysaccharide-induced stimulation of cytokines (Brattsand and Linden, 1996; Joyce et al., 1997; Barnes, 2001). Using freshly isolated human PBMCs, ZK 245186 was more potent but less efficacious than MPA in inhibition of lipopolysaccharide-induced secretion of IL-12p40 (Table 3). MF was as effective as MPA but displayed a higher potency than both ZK 241586 and MPA in this assay.

Co-incubation with a GR antagonist, RU-486, completely prevented the inhibitory effects of ZK 245186 on lipopolysaccharide-triggered IL-12p40 secretion, demonstrating that the inhibition of cytokine secretion by this compound was GR-dependent (Figure 2).

Phytohemagglutinin stimulation of PBMCs led to a significant increase in IFN-γ secretion, a strong pro-inflammatory cytokine produced by T cells, which was inhibited by the ZK 245186 and reference compounds. MF showed the highest potency and efficacy, and MPA and ZK 245186 were equally potent with similar efficacy (Table 3).

The MLR, that is, lymphocyte proliferation in response to allogeneic leukocytes, represents a standard in vitro assay for T cell immunity. Inhibition of MLR is induced by several classes of immunosuppressive agents, including calcineurin inhibitors, antimetabolites and GCs. ZK 245186 and the reference compounds have been tested for inhibition of lymphocyte proliferation in MLR. MF showed highest potency, but all compounds displayed comparable and high efficacy in the MLR (Table 3).

ZK 245186 has diminished transactivation activity

ZK 245186 was found to be less efficacious compared with the reference compounds in GR-dependent transactivation assays as shown by induction of MMTV-promoter activity in stably transfected HeLa cells (with an efficacy of 67%) and induction of TAT activity in human hepatoma cells (with an efficacy of 62%). In contrast, the efficacies of the tested classical GCs were in a range between 91% and 113% (Table 4). Regarding potency, a clear advantage for one or the other mechanism could not be seen for ZK 245186 or for one of the reference compounds. However, efficacy data obtained in transactivation assays (MMTV and TAT) for ZK 245186 were lower compared with efficacy data found in the transrepression/anti-inflammatory assays shown above (between 82% and 99% for inhibition of collagenase promoter, IL-12p40 and IFN-γ secretion). When comparing efficacy data from each transrepression assay (collagenase, IL-12p40, IFN-γ) with those from the transactivation assays (MMTV, TAT), ZK 245186 displayed for all cases a significantly higher efficacy for GR-mediated transrepression than transactivation. For MPA and MF this could be shown in only one instance (Table 5). These data underline that ZK 245186 behaved differently with regard to transactivation-induced mechanisms, when compared with the classical GCs.

Table 4.

Transactivation activity

| n | EC50 (nmol·L−1) | P-value versus ZK 245186 | P-value versus MPA | Efficacy (%) | P-value versus ZK 245186 | P-value versus MPA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Induction of MMTV promoter activity | |||||||

| ZK 245186 | 6 | 7.1 ± 3.2 | 67 ± 6 | ||||

| MPA | 5 | 21.8 ± 5.5 | 0.003 | 90 ± 6 | 0.003 | ||

| MF | 3 | 0.18 ± 0.11 | 0.017 | 0.036 | 113 ± 12 | 0.017 | 0.036 |

| Induction of TAT activity in human hepatoma cells | |||||||

| ZK 245186 | 5 | 71.2 ± 64.6 | 62 ± 7 | ||||

| MPA | 4 | 20.5 ± 1.7 | 0.016 | 98 ± 2 | 0.016 | ||

| MF | 4 | 0.1 ± 0.01 | 0.016 | 0.029 | 100 ± 3 | 0.016 | 0.029 |

Induction of MMTV promoter and TAT activities by ZK 245186, MPA and MF were determined as described in the Methods. EC50 values are listed as mean values ± SD. Efficacies are shown as % of maximum effect of the reference dexamethasone.

MF, mometasone furoate; MPA, methylprednisolone aceponate; MMTV, mouse mammary tumour virus; TAT, tyrosine aminotransferase.

Figures in bold indicate that there is a significant difference.

Table 5.

Comparison of efficacy data obtained in transrepression assays [inhibition of collagenase promoter activity (Coll) and of IL-12p40 and IFN-γ secretion] with efficacy data from transactivation assays (induction of MMTV promoter and of TAT activity)

| Coll/MMTV | IL-12p40/MMTV | IFN-γ/MMTV | Coll/TAT | IL-12p40/TAT | IFN-γ /TAT | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZK 245186 | Efficacy (%) | 89/67 | 83/67 | 88/67 | 89/62 | 83/62 | 88/62 |

| P-value | 0.001 | 0.008 | 0.003 | 0.004 | 0.009 | 0.008 | |

| MPA | Efficacy (%) | 92/90 | 98/90 | 88/90 | 92/98 | 98/98 | 88/98 |

| P-value | 0.548 | 0.03 | 0.556 | 0.413 | 0.114 | 0.686 | |

| MF | Efficacy (%) | 96/113 | 100/113 | 101/113 | 96/100 | 100/100 | 101/100 |

| P-value | 0.095 | 0.143 | 0.629 | 0.914 | 0.556 | 0.029 | |

P-values were determined using Mann Whitney rank sum test. Efficacy data are given in % (efficacy TR/efficacy TA).

IFN, interferon; MF, mometasone furoate; MPA, methylprednisolone aceponate; MMTV, mouse mammary tumour virus; TAT, tyrosine aminotransferase.

Figures in bold indicate that there is a significant difference.

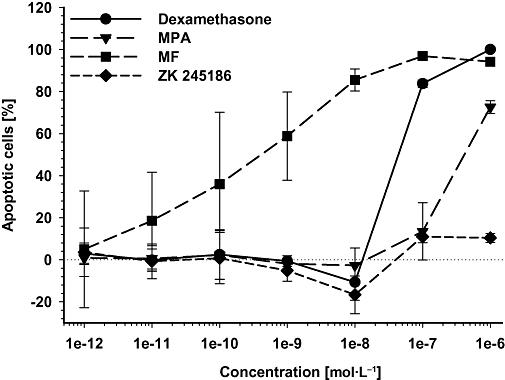

ZK 245186 has less effect on thymocyte apoptosis than classical GCs

GC-induced thymus involution is a well-known and unwanted phenomenon. Although the mechanisms of GC-induced thymocyte apoptosis are still not entirely understood, it is at least partially transactivation-dependent (Ashwell et al., 2000; Reichardt et al., 2000). Thus, the potential of ZK 245186 in the induction of gene transcription was determined in an assay for induction of thymocyte apoptosis with comparison with the effects of dexamethasone, MPA and MF. Remarkably, ZK 245186 did not induce apoptosis in the murine thymocyte cell line, S49, in contrast to the classical GCs included in the reference panel (Table 6, Figure 3).

Table 6.

ZK 245186 does not induce thymocyte apoptosis in vitro

| Time point (h) | n | ZK 245186 (%) | MPA (%) | MF (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 72 | 2 | −8.2 ± 11.2 | 46.5 ± 8.7 | 93.6 ± 3.0 |

| 96 | 2 | 10.4 ± 2.2 | 72.6 ± 3.0 | 94.2 ± 1.9 |

Glucocorticoid-mediated apoptosis in S49 thymocytes has been determined after 72 and 96 h of incubation with ZK 245186 or reference compounds at 1 µmol·L−1 as described in Methods. Background values (solvent DMSO) are subtracted. Results given show mean values normalized to the maximum effect of 1 µmol·L−1 dexamethasone of n = 2 experiments.

DMSO, dimethylsulphoxide; MF, mometasone furoate; MPA, methylprednisolone aceponate.

Figure 3.

Induction of thymocyte apoptosis by classical glucocorticoids but not by ZK 245186. S49 thymocytes were incubated with increasing concentrations of dexamethasone, methylprednisolone aceponate (MPA), mometasone furoate (MF) and ZK 245186 for 96 h. Background values (solvent dimethylsulphoxide) are subtracted. Results are calculated as % of maximum induction by dexamethasone at 1 µmol·L−1. Mean values from two experiments ± SD are shown.

Summarizing all the in vitro pharmacology data, ZK 245186 showed an anti-inflammatory activity comparable to MPA, but was less active compared with MF. In contrast, it showed substantially lower efficacies in assays of surrogate markers for potential transactivation-mediated side effects, suggesting a potentially advantageous safety profile in vivo.

In vivo pharmacology

The compound was tested in two skin inflammation animal models in mice and rats. As the model for non-specific inflammation, the irritant contact dermatitis model (croton oil) and for T cell-dependent inflammation, a model of allergic contact dermatitis (in response to DNFB) were chosen. The validity of these models has been established as many of the test compounds that exert marked anti-inflammatory efficacy in these models are therapeutically effective in human inflammatory skin diseases (Zollner et al., 2004). This is especially true for compounds acting via the GR, as there is a good correlation between the potency of GCs in these models and the potency observed in humans (Tramposch, 1999).

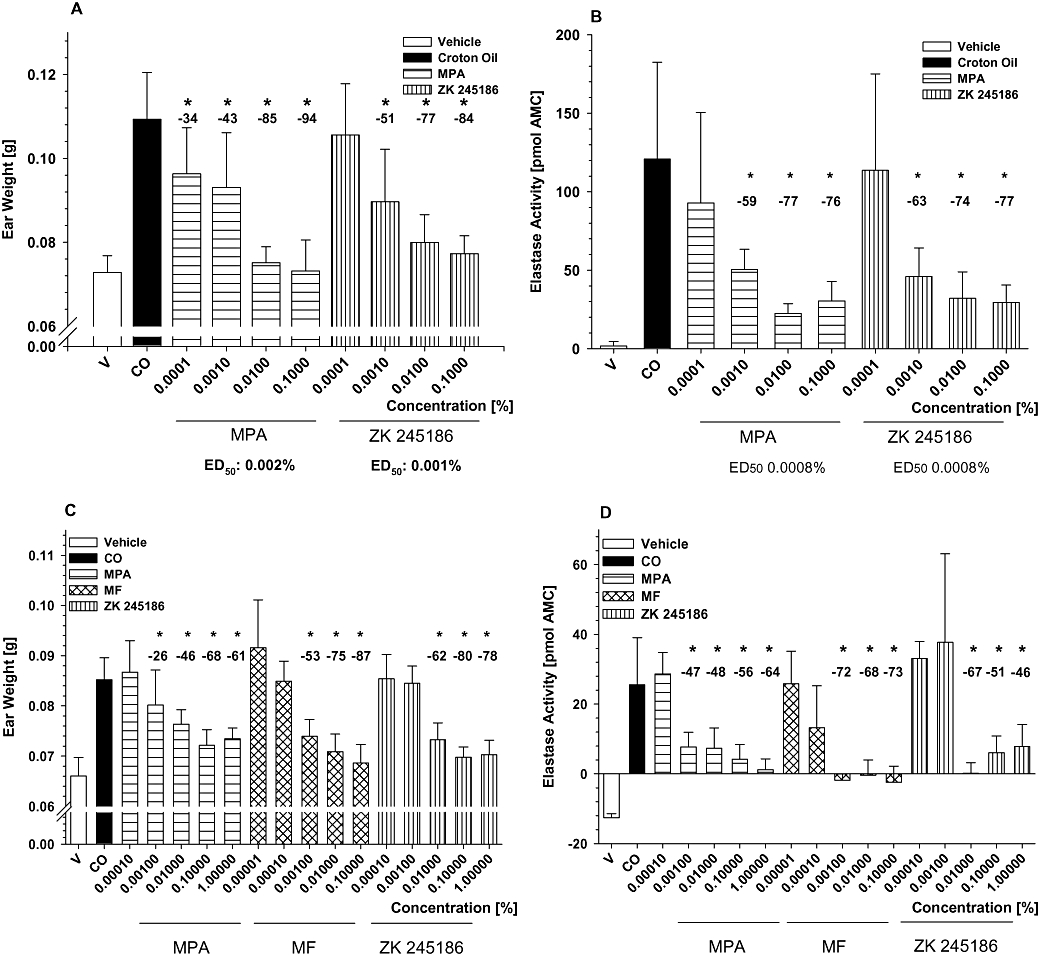

ZK 245186 exerts potent anti-inflammatory activity in irritant contact dermatitis in rodents

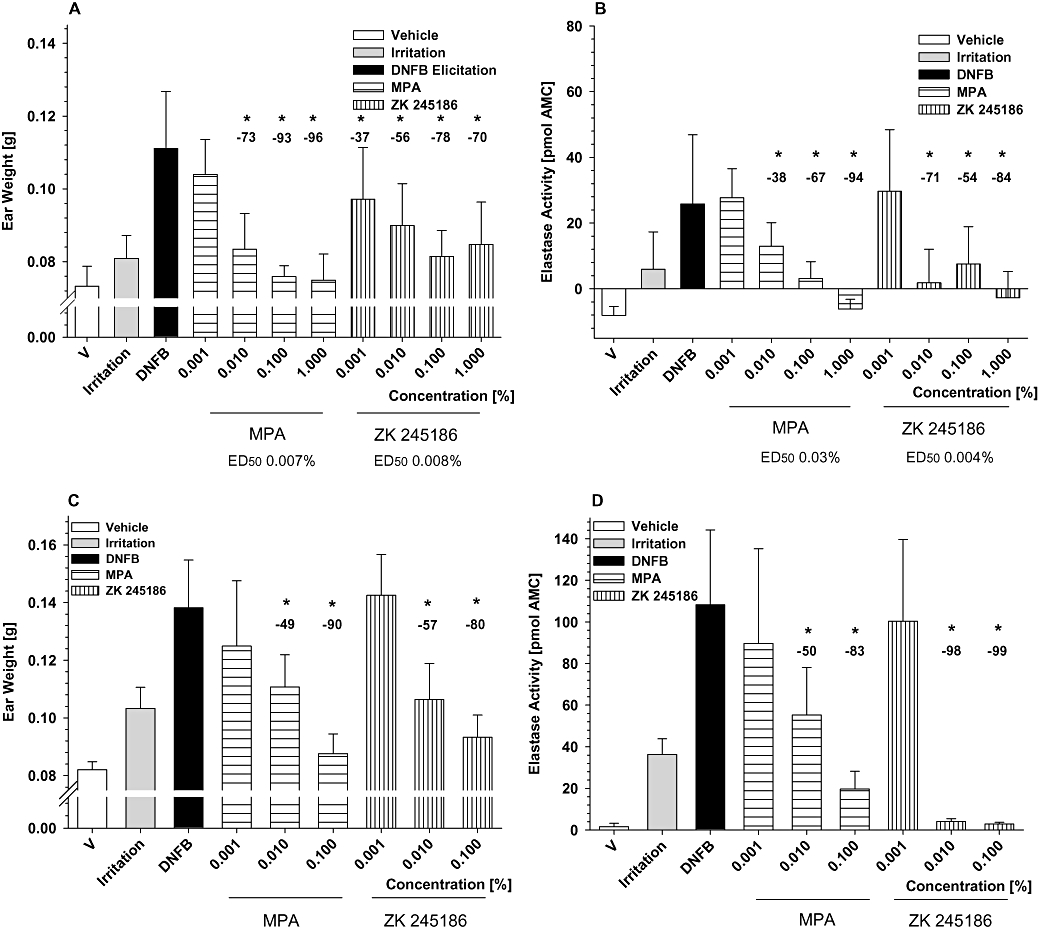

As shown in Figure 4A and B, ZK 245186 markedly and significantly inhibited ear inflammation in mice when applied topically to the ear. Already a significant reduction of ear weight as a marker of skin inflammation was observed at 0.001%, and maximum inhibition was achieved at 0.1%. The efficacy and potency of ZK 245186 were similar to that of MPA and the ED50 for inhibition of oedema formation was 0.001% and 0.002% for ZK 245186 and MPA respectively. The ED50 for inhibition of elastase activity as a marker of neutrophil infiltration was identical for both compounds (0.008%).

Figure 4.

Inhibition of croton oil-induced irritant contact dermatitis in mice and rats. Inhibition of oedema (A) and neutrophil infiltration (B) in the croton oil-induced model using female NMRI mice by topical treatment with ZK 245186 and methylprednisolone aceponate (MPA). Results show mean values ± SD from one representative (with 10 animals per group) out of three independent experiments. Comparing maximum inhibitory effects on oedema formation of ZK 245186 (0.1%) and MPA (0.1%), no significant differences between ZK 245186 and MPA were found (Tukey's post-test using sisam software package). Inhibition of oedema formation (C) and neutrophil skin infiltration (D) by ZK 245186 compared with MPA and mometasone furoate (MF) in the croton oil-induced irritant contact dermatitis model in rats. Results show mean values ± SD from one (with 10 animals per group) out of three independent experiments. Difference between vehicle and croton oil control bars represents the full magnitude of inflammation. Comparing maximum inhibitory effects on oedema formation of ZK 245186 (0.1%), MPA (0.1%) and MF (0.1%), no significant differences between ZK 245186, MPA and MF were found (Tukey's post-test using sisam software package). *P < 0.05 versus croton oil control (modified ‘Hemm-Test’, Department of Biometry, Bayer Schering Pharma AG).

Likewise, ZK 245186 inhibited croton oil-induced acute skin inflammation in rats (Figure 4C and D). All parameters including punch biopsy weight as a marker for overall skin inflammation and neutrophil infiltration measured by elastase activity were markedly and significantly reduced by ZK 245186. ZK 245186 was of similar potency regarding inhibition of oedema formation (ED50 0.008%) as the reference compound MPA (ED50 0.01%). MF showed about 10 times higher potency than MPA and ZK 245186 in this rat model, whereas MPA and MF are equipotent in man, in the same 0.1% formulation (Kecskes et al., 1993). In the croton oil-induced acute skin inflammation model in rats, the efficacies for ZK 245186, MPA and MF were comparable.

Immunomodulatory activity of ZK 245186 in rodent allergic contact dermatitis models

In mice, topically applied ZK 245186 markedly inhibited ear oedema formation in DNFB-induced contact dermatitis (measured by ear weight), reaching a maximum inhibition of 78% at concentrations of 0.1% with an ED50 concentration of 0.008%. The efficacy and potency of ZK 245186 to inhibit oedema formation were comparable to that of MPA. In addition, both compounds inhibited neutrophil skin infiltration with comparable efficacy (Figure 5A and B).

Figure 5.

Inhibition of dinitrofluorobenzene (DNFB)-induced allergic contact dermatitis in mice and rats. Inhibition of oedema (A) and neutrophil infiltration (B) by ZK 245186 compared with methylprednisolone aceponate (MPA) in female NMRI mice. Results show mean values ± SD from one representative (with 10 animals per group) out of three independent experiments. Comparing maximum inhibitory effects on oedema formation of ZK 245186 (0.1%) and MPA (0.1%), no significant differences were found (Tukey's post-test using sisam software package). Inhibition of oedema (C) and neutrophil infiltration (D) by ZK 245186 compared with MPA in female Wistar rats. Results show mean values ± SD from one representative (with 10 animals per group) out of three independent experiments. Difference between vehicle and croton oil control bars represents the full magnitude of inflammation. Comparing maximum inhibitory effects on oedema formation of ZK 245186 (0.1%) and MPA (0.1%), no significant differences were found (Tukey's post-test using sisam software package). *P < 0.05 versus DNFB control (modified ‘Hemm-Test’, Department of Biometry, Bayer Schering Pharma AG). Values in % show inhibition compared with DNFB positive control.

As shown in Figure 5C and D, ZK 245186 also significantly and markedly inhibited oedema formation and neutrophil skin infiltration and in DNFB-induced contact allergy in rats. The efficacy of ZK 245186 at 0.1% in the inhibition of oedema formation and neutrophil infiltration was 80% and 99% respectively, similar to that of MPA. ED50 values for inhibition of oedema and neutrophil infiltration were 0.0095% and 0.004%. No differences between the potency of ZK 245186 and MPA were observed.

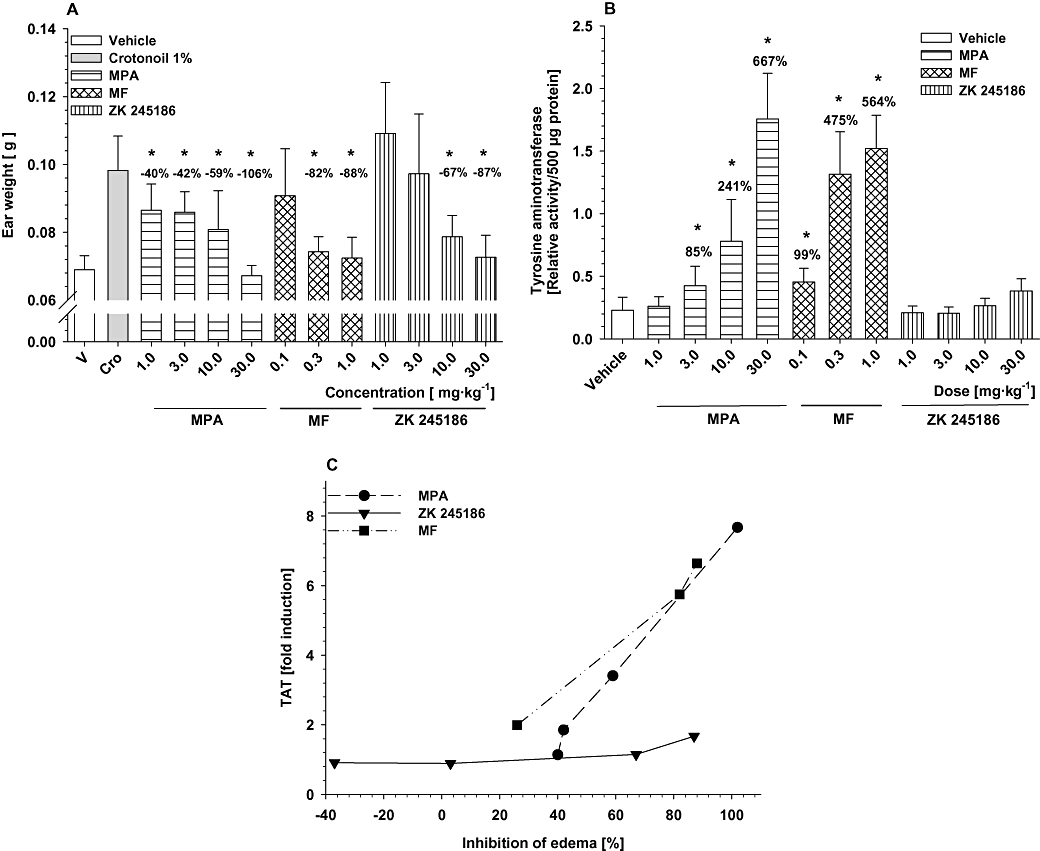

ZK 245186 is dissociated in vivo as measured by its anti-inflammatory versus pro-diabetogenic properties after systemic application

Impairment of glucose metabolism following GC application is predominantly caused by their transactivating potential, leading to induction of several enzymes involved in amino acid catabolism and gluconeogenesis, such as TAT. Therefore, determination of TAT induction may serve as a surrogate marker for measuring the potential of a compound to act via transactivation in vivo (Schäcke et al., 2004). Although all three compounds markedly inhibited croton oil-induced ear inflammation to a similar degree following s.c. application (Figure 6A), their potential for TAT induction was very different. ZK 245186 did not significantly induce TAT (maximum induction 1.67-fold compared with vehicle-treated animals at 87% inhibition of oedema formation; Figure 6B). MPA and MF, however, significantly and dose-dependently induced TAT activity (MPA up to 7.67-fold at 106% oedema inhibition and MF up to 6.64-fold at 88% inhibition). These data show that ZK 245186 is dissociated in vivo, whereas this is not the case for MPA and MF. The therapeutic ratio of ZK 245186 regarding its in vivo dissociation for the above-mentioned parameters is shown in Figure 6C.

Figure 6.

Dissociation of anti-inflammatory from side effects of ZK 245186 after systemic application. Anti-inflammatory properties have been determined in the croton oil mouse model following s.c. application. Inhibition of oedema formation (A) is shown. For side effects, induction of tyrosine aminotransferase (TAT) activity has been chosen as a surrogate marker (B). From these data, a therapeutic window (C) can be determined for ZK 245186 in which profound anti-inflammatory properties can be observed while induction of TAT enzyme (transactivation) is still absent. *P < 0.05 versus croton oil control (A) or versus vehicle control (B) (modified ‘Hemm-Test’ for data obtained from croton oil model and Dunnett's post-test for TAT data using the sisam software package, Department of Biometry, Bayer Schering Pharma AG). Values in % show inhibition compared with croton oil positive control (A) or % induction of TAT activity compared with vehicle. MF, mometasone furoate; MPA, methylprednisolone aceponate.

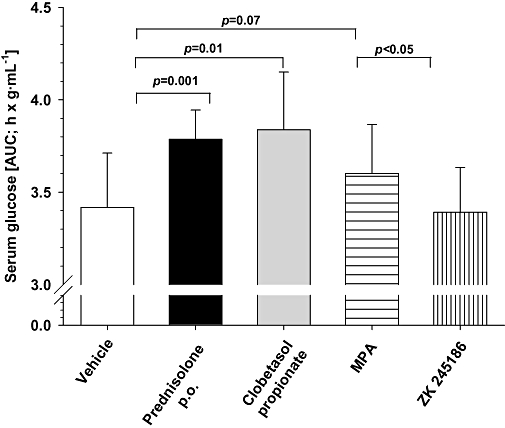

ZK 245186 does not alter glucose concentrations in the oral glucose tolerance test in therapeutically active doses in rats

GCs frequently cause hyperglycaemia by: (i) decreasing utilization of glucose; (ii) increasing hepatic glucose production; and (iii) inhibiting insulin sensitivity in hepatocytes, myocytes and adipocytes. The aim of this study was to analyse whether repeated topical or systemic application of marketed GCs is able to alter glucose tolerance and to investigate whether application of ZK 245186 may have advantages compared with classical GCs such as MPA.

ZK 245186, MPA and clobetasol propionate, the most potent topical GC, used as reference for systemic side effects after topical administration, were topically applied over a period of 4 days, whereas prednisolone as positive control was given orally. Fasting blood glucose among different groups on day 5 was in the range of 1–1.1 g·mL−1. Following glucose challenge, a rapid increase of blood glucose concentrations was observable in all groups within 30 min. In vehicle- and ZK 245186-treated animals (topical), blood glucose concentrations were rapidly reduced and reached baseline values within 120 min. In contrast, in animals pre-treated with either prednisolone orally or clobetasol propionate topically, glucose concentrations did not fall within the first 60 min and remained at the near maximal concentration for up to 120 min. AUC values (0–180 min) differed clearly between vehicle-treated animals and prednisolone (P < 0.001) as well as clobetasol propionate-treated animals (P < 0.01). MPA-treated animals took an intermediate position in between vehicle and ZK 245186-treated animals on one side and prednisolone and clobetasol propionate on the other. Normalization of blood glucose concentration in MPA-treated animals was delayed and AUC values had a trend to be different from vehicle-treated animals (P = 0.07). When MPA was compared with ZK 245186, this trend reached the level of significance (P < 0.05; Figure 7). In contrast to all the GCs tested, ZK 245186 did not disrupt the normal response to oral glucose challenge.

Figure 7.

Glucose tolerance test following topical application of ZK 245186 to rat skin. The area under the blood glucose-time curve (AUC) was measured for 180 min after an oral glucose challenge (see Methods). The AUC after treatment with prednisolone, clobetasol propionate or methylprednisolone aceponate (MPA), but not that after ZK 245186, was greater than that after control (vehicle), showing a disturbed tolerance of glucose load. Compounds (prednisolone p.o., clobetasol propionate, MPA and ZK 245186 topically) were applied for 4 days to hr/hr rats. On day 4, rats were subjected to an overnight fasting period prior to an oral glucose challenge on day 5. Results show mean values ± SD (A) from one out of two independent experiments, with six animals per group.

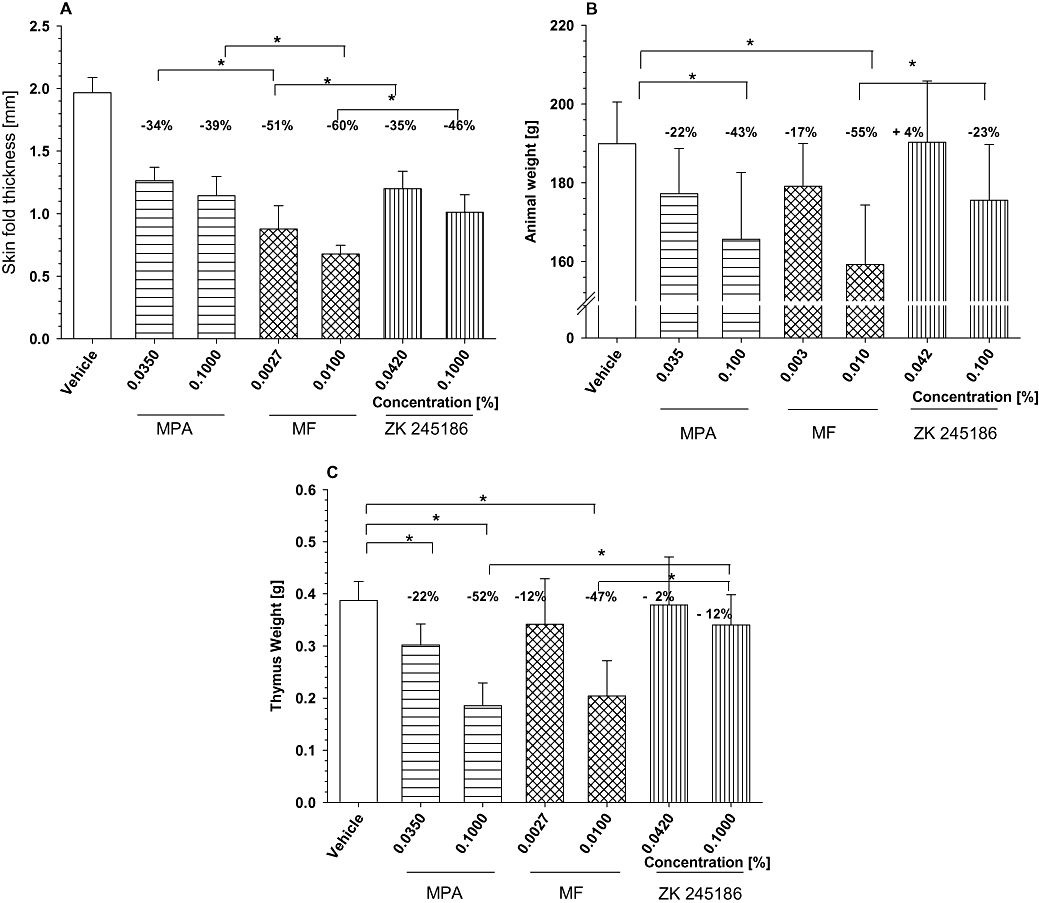

ZK 245186 has an improved cutaneous and systemic side effect profile after topical application

The aim of this experiment was to analyse the local and systemic safety profile of ZK 245186. The variable measured was skin fold thickness as indicator for skin atrophy (topical side effects). Measuring skin thickness in the rat model is known to be a very sensitive indicator of GC-mediated skin atrophy and it allows a rank-ordering of GC-mediated skin atrophy that correlates with the human situation (own observations; data not shown). Total body weight as well as weight of thymus and the adrenal glands were determined as indicators for systemic side effects after topical administration for 19 days at two different concentrations: 3× ED50 of anti-inflammatory effects and a concentration that results in ca. 80% inhibition of oedema formation in the croton oil rat model.

Skin fold thickness was significantly decreased in all groups compared with vehicle-treated animals when measured at the end of the treatment period on day 19. This effect was dose-dependent for all compounds. Reduction in skin fold thickness was most pronounced for MF-treated animals, whereas it was less pronounced for ZK 245186 and MPA. Skin fold thickness was significantly higher in MPA- and ZK 245186-treated animals compared with MF-treated animals. The superiority of MPA versus MF with regard to its atrophogenic potential has been reported previously (Mirshahpanah et al., 2007). There was no significant difference between MPA and ZK 245186 treatments, both showing only minimal effects on skin thickness (Figure 8A).

Figure 8.

Local and systemic side effects of glucocorticoid receptor (GR) agonists. ZK 245186 or reference glucocorticoids were topically applied to juvenile rat skin. ZK 245186, MPA and MF were topically applied for 19 days in equipotent (3× ED50: 0.042%, 0.035% and 0.0027% respectively) or equi-effective concentrations (0.1%, 0.1% and 0.01% respectively). Skin fold thickness and total body weight were monitored over time and data for dat 19 are given in (A) and (B) respectively. On day 20, animals were killed and the thymus dissected and weighed (C). *P < 0.05 versus vehicle control or reference compounds (Tukey's post-test using the sisam software package, Department of Biometry, Bayer Schering Pharma AG). Experiments have been repeated twice and one representative is depicted here.

Regarding systemic side effects, ZK 245186 showed the least effects when compared with MF and MPA. Animal growth was not significantly reduced in ZK 245186-treated animals whereas this was the case in MPA- and MF-treated animals at the higher concentration. Body weight of MF-treated animals (0.01%) was significantly lower compared with ZK 245186-treated animals (0.1%) (Figure 8B). Also thymus weight was not significantly decreased in ZK 245186-treated animals whereas this was the case following application of MPA and MF treatment. Thymus weight of ZK 245186-treated (0.1%) animals was significantly higher than following MPA (0.1%) and MF (0.01%) treatments (Figure 8C). Adrenal gland weight was slightly but not significantly reduced in all compound-treated groups compared with vehicle, and no significant differences between the compounds have been observed (data not shown).

Summarizing the in vivo data, ZK 245186 shows similar anti-inflammatory effects in rodents but fewer side effects than those of the classical GCs.

Pharmacokinetics

ZK 245186 is metabolically highly unstable with liver microsomes from various species, including human. In vivo kinetics in rats show a high hepatic clearance (CLH > 80% of liver blood flow), and a high volume of distribution (Vss: 8 L·kg−1). It has a short half-life (2 h) after i.v. administration and a low bioavailability (9%) after topical administration (data not shown). The prediction of human pharmacokinetics suggests a high hepatic blood clearance, a free but not excessive tissue distribution and a short half-life. Thus, these physicochemical and pharmacokinetic properties characterize ZK 245186 as being suited for topical treatment with low systemic activity.

Discussion

The GCs are among the most effective anti-inflammatory drugs. However, their value is limited by side effects. Therefore, in the pharmaceutical industry there is intense effort to identify compounds that display tailored biological properties leading to an improved safety profile (see Mohler et al., 2007; Schäcke et al., 2008). The first in vitro dissociated GR ligands, such as RU 24782, RU 24858 and RU 40066 (Vayssiere et al., 1997), did not show a separation of anti-inflammatory effects from side effects in vivo (Belvisi et al., 2001). Newer compounds, however, have been demonstrated to display a dissociated profile in vitro and in vivo. These include AL-438 (Coghlan et al., 2003), ‘compound A’ from an academic group (De Bosscher et al., 2005), LGD-5552 (Braddock, 2007; Lopez et al., 2008) and our first reported selective GR agonist, ZK 216348 (Schäcke et al., 2004). Whereas these compounds are valuable as investigational tools and support the hypothesis that dissociation of the molecular mechanisms can be translated into a higher therapeutic index, they may not necessarily represent drug candidates. Drawbacks like limited selectivity, unclear toxicology or unsuitable pharmacodynamic profile might prevent clinical use in patients.

The main focus in the search for novel GR ligands is on compounds to be used systemically. There are, however, a few programmes, including ours, aiming also at the identification of compounds particularly suited for topical application, such as cutaneous application in dermatoses, ophthalmic application for eye diseases or inhaled therapy in asthma. Such compounds have a target profile beyond the molecular dissociation, for instance, with regard to pharmacokinetic aspects, where low systemic bioavailability due to low metabolic stability would be an advantage. With ZK 245186, we describe for the first time a promising, novel, dissociated GR ligand suitable for topical treatment.

In vitro characterization showed that ZK 245186 binds with high affinity to the GR and is selective for the GR (Tables 1 and 2). Inhibition of pro-inflammatory cytokines (Andreakos, 2003; Braddock et al., 2004; Vandenbroeck et al., 2004) and chemokines (Bunikowski et al., 2000; Sebastiani et al., 2002) has been shown to be important for therapy of inflammatory skin diseases. In cell lines as well as in human primary cells, ZK 245186 inhibited stimulus-induced AP-1 activity, cytokine secretion and lymphocyte proliferation with high efficacy (Table 3). In contrast, ZK 245186 displayed a reduced efficacy in transactivation assays (Tables 4 and 5) and was ineffective in inducing apoptosis in murine thymocytes (Figure 3 and Table 6). These data indicated that ZK 245186 is a molecularly dissociated GR ligand with the potential for full anti-inflammatory activity in vivo, but a lower risk to induce side effects, or surrogate markers for side effects, in animal models.

Indeed, in two models of contact dermatitis a strong anti-inflammatory activity of this compound was demonstrated. Applied topically, ZK 245186 inhibited skin inflammation in croton oil-induced irritative dermatitis and in DNFB-induced contact hypersensitivity in mice and rats, as effectively as MPA and MF (Figures 4 and 5). Remarkably, ZK 245186 was clearly superior to MF, in terms of a risk of inducing skin atrophy (Figure 8). Moreover, when we looked at undesired systemic effects after topical as well as after systemic administration of pharmacologically active doses, the advantage of ZK 245186 was even more pronounced in comparison with both MPA and MF (Figure 6). So, surrogate markers for diabetes mellitus induction (increase in hepatic TAT activity and disturbed tolerance to oral glucose challenge) were not triggered by ZK 245186, in contrast to MPA and/or MF (Figure 7). Additionally, fully in line with the in vitro results from the assay of thymocyte apoptosis, thymus involution also was not induced by ZK 245186 after long-term topical treatment in contrast to both MPA and MF (Figure 8).

Together with a favourable pharmacokinetic profile, this pharmacodynamic profile resulted in an improved effect/side effect ratio in rodents for ZK 245186, compared with two well-established compounds for local GC treatment of inflammatory skin diseases. Consequently, we hypothesize that ZK 245186 may demonstrate significant advantages over conventional topical GCs in patients. Recently published clinical data, demonstrating similar efficacy for MPA or MF and tacrolimus in patients with atopic dermatitis (Bieber et al., 2007; Gradman and Wolthers, 2008), might also suggest that ZK 245186 could compete not only with established topical GCs but also with the more recently marketed topical calcineurin inhibitors. The fact that ZK 245186 represents a potent and highly specific GR ligand is a good precondition for a favourable safety profile.

Why do we see less undesired effects with ZK 245186 in vitro and in vivo? ZK 245186 binds to the GR with high affinity and induces anti-inflammatory effects, in a similar manner as the reference GCs. Nevertheless, this new compound varies from the classical GCs in some important aspects. First, ZK 245186 has a non-steroidal chemical structure. This feature may also be of interest as there is discomfort in a considerable subset of patients regarding the use of steroidal GCs (‘steroid-phobia’) (Charman et al., 2002). Second, ZK 245186 is highly specific for the GR and, therefore, interferes less with other closely related, nuclear receptors, such as the MR, than is found for the classical GCs. Third, in mechanistic assays, ZK 245186 showed a preference for actions related to repression over those related to activation in vitro (dissociation). Fourth and most importantly, this molecular dissociation was also exhibited in vivo in rodent models for anti-inflammatory efficacy and side effect induction. All these aspects combined with the suitable pharmacokinetic properties have been considered for compound generation and selection and add up to an improved therapeutic index at least in experimental settings.

The compound finding programme leading to the discovery of ZK 245186 was initiated on the basis of the transactivation/transrepression hypothesis (dissociation). Recent work has yielded new insights into the molecular mechanisms of the GR and disclosed a more complex picture (Newton and Holden, 2007). Many different factors are involved in GR-mediated repression of gene expression, such as the architecture of the regulatory recognition sequences in the promoter region of GR-sensitive genes, the availability and activity of additional transcription factors, co-factors, as well as regulatory inputs from synergistic and antagonistic pathways (Chinenov and Rogatsky, 2007). We think that this new selective GR agonist, ZK 245186, binds to the GR in a way that leads to a receptor surface, different to that provided by a GR binding a steroid. Such an altered receptor conformation can induce a different co-factor recruitment leading to an altered induction of molecular mechanisms of the GR, such as a preference for repression over activation. For this specific GR agonist, we have not shown the co-factor profile yet. However, such a modified cofactor pattern has been described for AL-438, representing another GR ligand with full anti-inflammatory activity but a reduced side effect pattern (Coghlan et al., 2003), supporting our hypothesis.

In summary, we show that ZK 245186 represents a novel non-steroidal GR ligand with potent anti-inflammatory activity and a superior therapeutic index in comparison with the gold standards of topical GCs. Thus, ZK 245186 is a promising drug candidate for the topical treatment of atopic dermatitis and other inflammatory disorders.

To the best of our knowledge except for this compound, all other dissociated GR ligands are still in the preclinical stage. ZK 245186, however, is already in early clinical development for application in inflammatory skin diseases and for ophthalmologic indications. Clinical proof of concept studies will eventually demonstrate whether the data from in vitro investigations and animal experiments will translate into separation of therapeutic effects and side effects in man. The data so far suggest that this will be the case and will ultimately lead to a novel drug.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Professor Wolfram Sterry (Berlin, Germany) and Professor Andrew Cato (Karlsruhe, Germany) for helpful discussions and critically reading the manuscript. Silke Kuehn (Berlin, Germany) from the German Skin Research Centre gave editorial assistance. Bayer Schering Pharma AG is collaborating intensively with AstraZeneca to fully explore the potential of selective GR agonists.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- AR

androgen receptor

- AUC

area under the curve

- CF

competition factor

- CLH

clearance in hepatocytes

- DMSO

dimethylsulphoxide

- DNFB

dinitrofluorobenzene

- ERα

oestrogen receptor α

- FCS

foetal calf serum

- GC

glucocorticoid

- GR

glucocorticoid receptor

- IFN

interferon

- IL

interleukin

- MF

mometasone furoate

- MLR

mixed leukocyte reaction

- MMTV

mouse mammary tumour virus

- MPA

methylprednisolone aceponate

- MR

mineralocorticoid receptor

- PBMCs

peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- PR

progesterone receptor

- TAT

tyrosine aminotransferase

- TNF

tumour necrosis factor

- TPA

12-o-tetradecanoylphorbol 13-acetate

- Vss

volume of distribution

Conflict of interest

The authors state no conflict of interest. All are employees of Bayer-Schering-Pharma AG, working on the drug discovery project described.

References

- Aggarwal RK, Potamitis T, Chong NH, Guarro M, Shah P, Kheterpal S. Extensive visual loss with topical facial steroids. Eye. 1993;18:309–345. doi: 10.1038/eye.1993.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SP, Mathie A, Peters JA. Guide to receptors and channels (GRAC), 3rd edn. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153(Suppl. 2):S1–S209. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreakos E. Targeting cytokines in autoimmunity: new approaches, new promise. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2003;3:435–447. doi: 10.1517/14712598.3.3.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashwell JD, Lu FWM, Vacchio MS. Glucocorticoids in T cell development and function. Ann Rev Immunol. 2000;18:309–345. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes PJ. Molecular mechanisms of corticosteroids in allergic diseases. Allergy. 2001;56:928–936. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.2001.00001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton BE, Jackway JP, Smith SR, Siegel MI. Cytokine inhibition by a novel steroid, mometasone furoate. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. 1991;13:251–261. doi: 10.3109/08923979109019704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belvisi MG, Wicks S, Battram CH, Bottoms SEW, Redford JE, Woodmann P, et al. Therapeutic benefit of a dissociated glucocorticoid and the relevance of in vitro separation of transrepression from transactivation activity. J Immunol. 2001;166:1975–1982. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.3.1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berrebi D, Bruscoli S, Cohen N, Foussat A, Migliorati G, Bouchet-Delbos L, et al. Synthesis of glucocorticoid-induced leucine zipper (GILZ) by macrophages: an anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive mechanism shared by glucocorticoids and IL-10. Blood. 2003;101:729–738. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-02-0538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bieber T, Vick K, Fölster-Holst R, Belloni-Fortina A, Städtler G, Worm M, et al. Efficacy and safety of methylprednisolone aceponate ointment 0.1% compared to tacrolimus 0.03% in children and adolescents with acute flare of severe atopic dermatitis. Allergy. 2007;62:184–189. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2006.01269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodor N, Buchwald P. Corticosteroid design for the treatment of asthma: structural insights and the therapeutic potential of soft corticosteroids. Curr Pharm Design. 2006;12:3241–3260. doi: 10.2174/138161206778194132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth BA, Tan EM, Oikarinen A, Uitto J. Steroid-induced dermal atrophy: effects of glucocorticosteroids on collagen metabolism in human skin fibroblast cultures. Int J Dermatol. 1982;21:333–337. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1982.tb03140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braddock M. Advances in anti-inflammatory therapeutics. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2007;16:257–261. doi: 10.1517/13543784.16.2.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braddock M, Quinn A, Canvin J. Therapeutic potential of targeting IL-1 and IL-18 in inflammation. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2004;4:847–860. doi: 10.1517/14712598.4.6.847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brattsand R, Linden M. Cytokine modulation by glucocorticoids: mechanism and actions in cellular studies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1996;10(Suppl. 2):81–90. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1996.22164025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunikowski R, Gerhold K, Bräutigam M, Hamelmann E, Renz H, Wahn U. Effects of low-dose cyclosporine A microemulsion on disease severity, interleukin-6, interleukin-8 and tumor necrosis factor alpha production in severe pediatric atopic dermatitis. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2000;125:344–348. doi: 10.1159/000053836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charman CR, Morries AD, Williams HC. Topical corticosteroid phobia in patients with atopic eczema. Br J Dermatol. 2002;142:931–936. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinenov Y, Rogatsky I. Glucocorticoids and the innate immune system: crosstalk with toll-like receptor signaling network. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2007;275:30–42. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2007.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coghlan MJ, Jacobson PB, Lane B, Nakane M, Lin CW, Elmore SW, et al. A novel anti-inflammatory maintains glucocorticoid efficacy with reduced side effects. Mol Endocrinol. 2003;17:860–869. doi: 10.1210/me.2002-0355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Bosscher K, Vanden Berghe W, Beck IME, Van Molle W, Hennuyer N, Hapgood J, et al. A fully dissociated compound of plant origin for inflammatory gene repression. PNAS. 2005;102:15827–15832. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505554102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Swert LF, Wouters C, de Zegher F. Myopathy in children receiving high-dose inhaled fluticasone. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1157–1159. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200403113501122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrott HM, Walland MJ. Glaucoma from topical corticosteroids to the eyelids. Clin Experiment Ophthamol. 2004;32:224–226. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2004.00787.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gradman J, Wolthers OD. Suppressive effects of topical mometasone furoate and tacrolimus on skin prick testing in children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2008;25:269–270. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2008.00651.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez EC, Frost P. Induction of glycosuria and hyperglycemia by topical corticosteroid therapy. Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:1559–1562. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heck S, Kullmann M, Gast A, Ponta H, Rahmsdorf HJ, Herrlich P, et al. A distinct modulating domain in glucocorticoid receptor monomers in the repression of activity of the transcription of AP-1. EMBO J. 1994;13:4087–4095. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06726.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hench PS, Kendall EC, Slocumb CH, Polley HF. The effect of a hormone of the adrenal cortex (17-hydroxy-11-dehydrocorticosterone: Compound E) and the pituitary adrenocorticotropic hormone on rheumatoid arthritis. Preliminary report. Proc Staff Meet Mayo Clin. 1949;24:181–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Hoven WE, van den Berg TP, Korstanje C. The hairless mouse as a model for study of local and systemic atrophogenic effects following topical application of corticosteroids. Acta Derm Venereol. 1991;71:29–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyce DA, Steer JH, Abraham LJ. Glucocorticoid modulation of human monocyte/macrophage function: control of TNF-alpha secretion. Inflamm Res. 1997;46:447–451. doi: 10.1007/s000110050222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassel O, Sancono A, Krätzschmar J, Kreft B, Stassen M, Cato AC. Glucocorticoids inhibit MAP kinase via increased expression and decreased degradation of MKP-1. EMBO J. 2001;20:7108–7116. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.24.7108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kecskes A, Heger-Mahn D, Kihlmann RK, Lange L. Comparison of the local and systemic side effects of methylprednisolone aceponate and mometasone furoate applied as ointments with equal anti-inflammatory activity. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:576–580. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(93)70224-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura T, Doi K. Dorsal skin reactions of hairless dogs to topical treatment with corticosteroids. Toxicol Pathol. 1999;27:528–535. doi: 10.1177/019262339902700506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby JD, Munro DD. Steroid-induced atrophy in animal and human model. Br J Dermatol. 1976;94:111–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1976.tb02279.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- König H, Ponta H, Rahmsdorf HJ, Herrlich P. Interference between pathway-specific transcription factors: glucocorticoids antagonize phorbol ester-induced AP-1 activity without altering AP-1 site occupation in vivo. EMBO J. 1992;11:2241–2246. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05283.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez FJ, Ardecky RJ, Bebo B, Benbatoul K, De Grandpre L, Liu S, et al. LGD-5552, an antiinflammatory glucocorticoid receptor ligand with reduced side effects, in vivo. Endocrinology. 2008;149:2080–2089. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luger T, Loske KD, Elsner P, Kapp A, Kerscher M, Korting HC, et al. Topische skin therapy with glucocorticoids – the rapeutischer index. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2004;2:629–634. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0353.2004.03626.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maibach HI, Wester RC. Issues in measuring percutaneous absorption of topical corticosteroids. Int J Dermatol. 1992;31(Suppl. 1):21–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1992.tb04008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills CM, Marks R. Side effects of topical glucocorticoids. Curr Probl Dermatol. 1993;21:122–131. doi: 10.1159/000422371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miner JN, Hong MH, Negro-Vilar A. New and improved glucocorticoid receptor ligands. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2005;14:1527–1545. doi: 10.1517/13543784.14.12.1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirshahpanah P, Döcke WD, Merbold U, Asadullah K, Röse L, Schäcke H, et al. Superior nuclear receptor selectivity and therapeutic index of methylprednisolone aceponate versus mometasone furoate. Exp Dermatol. 2007;16:753–761. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2007.00597.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno H, Uemura K, Moriyama A, Wada Y, Asai K, Kimura S, et al. Glucocorticoid induced the expression of mRNA and the secretion of lipocortin 1 in rat astrocytoma cells. Brain Res. 1997;764:256–264. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(96)01259-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohler ML, He Y, Wu Z, Hong SS, Miller DD. Dissociated non-steroidal glucocorticoids: tuning out untoward effects. Expert Opin Ther Patents. 2007;17:37–58. doi: 10.1517/13543776.17.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton R, Holden NS. Separating transrepression and transactivation: a distressing divorce for the glucocorticoid receptor? Mol Pharmacol. 2007;72:799–809. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.038794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickisch K, Bittler D, Laurent H, Losert W, Nishino Y, Schillinger E, et al. Aldosterone antagonists. 3. Synthesis and activities of steroidal 7α-(alkoxycarbonyl)-15,16-methylene spirolactones. J Med Chem. 1990;33:509–513. doi: 10.1021/jm00164a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson JE, Gip LJ. Systemic effects of local treatment with high doses of potent corticosteroids in psoriatics. Acta Derm Venereol. 1979;59:245–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connell EJ. Review of the unique properties of budesonide. Clin Ther. 2003;25(Suppl. C):C42–C60. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(03)80305-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perretti M, D'Acquisto F. Annexin A1 and glucocorticoids as effectors of the resolution of inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:62–70. doi: 10.1038/nri2470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichardt HM, Kaestner KH, Tuckermann J, Kretz O, Wessely O, Bock R, et al. DNA binding of the glucocorticoid receptor is not essential for survival. Cell. 1998;93:531–541. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81183-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichardt HM, Tronche F, Bauer A, Schütz G. Molecular genetic analysis of glucocorticoid signaling using the Cre/LoxP system. Bio Chem. 2000;381:961–964. doi: 10.1515/BC.2000.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichardt HM, Tuckermann JP, Göttlicher M, Vujic M, Weih F, Angel P, et al. Repression of inflammatory responses in the absence of DNA binding by the glucocorticoid receptor. EMBO J. 2001;20:7168–7173. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.24.7168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schäcke H, Döcke WD, Asadullah K. Mechanisms involved in the side effects of glucocorticoids. Pharmacol Ther. 2002;96:23–43. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(02)00297-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schäcke H, Schottelius A, Döcke WD, Strehlke P, Jaroch S, Schmees N, et al. Dissociation of transactivation from transrepression by a selective glucocorticoid receptor agonist leads to separation of therapeutic effects from side effects. PNAS. 2004;101:227–232. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0300372101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schäcke H, Berger M, Hansson TG, McKerrecher D, Rehwinkel H. Dissociated glucocorticoid receptor modulators: an update on new compounds. Expert Opin Ther Patents. 2008;18:339–352. [Google Scholar]

- Schottelius AJ, Giesen C, Asadullah K, Fierro IM, Colgan SP, Bauman J, et al. An aspirin-triggered lipoxin A4 stable analog displays a unique topical anti-inflammatory profile. J Immunol. 2002;169:7063–7070. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.12.7063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebastiani S, Albanesi C, De PO, Puddu P, Cavani A, Girolomoni G. The role of chemokines in allergic contact dermatitis. Arch Dermatol Res. 2002;293:552–559. doi: 10.1007/s00403-001-0276-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tramposch KM. Skin inflammation. In: Morgan DW, Marshall LA, editors. In vivo Models of Skin Inflammation. Birkhäuser Verlag: Basel; 1999. pp. 179–204. [Google Scholar]

- Vandenbroeck K, Alloza I, Gadina M, Matthys P. Inhibiting cytokines of the interleukin-12 family: recent advances and novel challenges. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2004;56:145–160. doi: 10.1211/0022357022962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]