Abstract

Background and purpose:

The sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR), regulates the cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]cyto) in vascular smooth muscle. Release from the SR is controlled by two intracellular receptor/channel complexes, the ryanodine receptor (RyR) and the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor (IP3R). These receptors may be regulated by the accessory FK506-binding protein (FKBP) either directly, by binding to the channel, or indirectly via FKBP modulation of two targets, the phosphatase, calcineurin or the kinase, mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR).

Experimental approach:

Single portal vein myocytes were voltage-clamped in whole cell configuration and [Ca2+]cyto measured using fluo-3. IP3Rs were activated by photolysis of caged IP3 and RyRs activated by hydrostatic application of caffeine.

Key results:

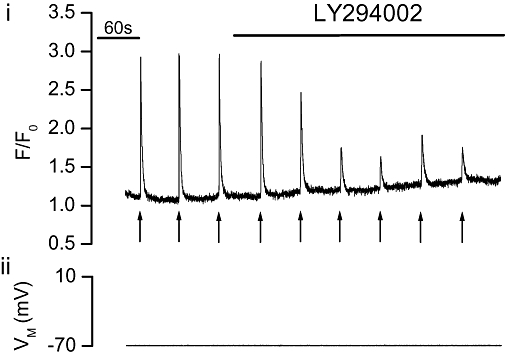

FK506 which displaces FKBP from each receptor (to inhibit calcineurin) increased the [Ca2+]cyto rise evoked by activation of either RyR or IP3R. Rapamycin which displaces FKBP (to inhibit mTOR) also increased the amplitude of the caffeine-evoked, but reduced the IP3-evoked [Ca2+]cyto rise. None of the phosphatase inhibitors, cypermethrin, okadaic acid or calcineurin inhibitory peptide, altered either caffeine- or IP3-evoked [Ca2+]cyto release; calcineurin did not contribute to FK506-mediated potentiation of RyR- or IP3R-mediated Ca2+ release. The mTOR inhibitor LY294002, like rapamycin, decreased IP3-evoked Ca2+ release.

Conclusions and implications:

Ca2+ release in portal vein myocytes, via RyR, was modulated directly by FKBP binding to the channel; neither calcineurin nor mTOR contributed to this regulation. However, IP3R-mediated Ca2+ release, while also modulated directly by FKBP may be additionally regulated by mTOR. Rapamycin inhibition of IP3-mediated Ca2+ release may be explained by mTOR inhibition.

Keywords: FK506; rapamycin; FK506-binding proteins; ryanodine receptor; inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor; mTOR; calcineurin; vascular smooth muscle; calcium

Introduction

Regulation of the cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]cyto) is vital to the control of vascular tone. The intracellular Ca2+ store, the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR), critically regulates [Ca2+]cyto, by controlling Ca2+ release (Bootman et al., 2001; McCarron et al., 2006). Release from the SR is mediated by two intracellular receptor complexes, the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor (IP3R) and the ryanodine receptor (RyR; nomenclature follows Alexander et al., 2008). IP3Rs are activated primarily by IP3 generated via G-protein- or tyrosine kinase-linked receptor activation (Bootman et al., 2001). In smooth muscle RyRs may also be activated pharmacologically (e.g. by caffeine) or when the Ca2+ content of the SR exceeds normal physiological levels (Burdyga and Wray, 2005; McCarron et al., 2006).

RyR and IP3R are regulated by accessory proteins. Of particular importance are the FK506-binding proteins (FKBPs) (Cameron et al., 1995b; Dargan et al., 2002; Tang et al., 2002; Zheng et al., 2004) which were identified initially as the cytoplasmic receptor for the clinical immunosuppressant drugs FK506 and rapamycin (Harding et al., 1989). The association between FKBP and IP3R or RyR is disrupted by FK506 and rapamycin, each of which binds to the accessory protein to form a drug-immunophilin protein complex and displaces FKBP from the channels (Cameron et al., 1995b; Bultynck et al., 2001a; Dargan et al., 2002).

The two major isoforms of the FKBP recognized as regulators of Ca2+ release channels are FKBP12 (the 12 kDa form of the protein) and FKBP12.6 (the 12.6 kDa form) (Tang et al., 2002; Wang et al., 2004; MacMillan et al., 2005b). FKBP12 and FKBP12.6 associate with IP3R in various cell types (Cameron et al., 1995b; Cameron et al., 1995a; MacMillan et al., 2005b) suggesting that FKBP-dependent modulation of channel function may have an important role in Ca2+ signaling. Indeed, in some investigations removal of FKBP12 from the channel decreased IP3R-mediated Ca2+ release (MacMillan et al., 2005b) and addition of exogenous FKBP12 increased IP3R channel activity in bilayer studies (Dargan et al., 2002). Furthermore, rapamycin, which disrupts FKBP-IP3R, decreased phenylephrine-induced contractions in rat vas deferens (Scaramello et al., 2009). These results suggest that FKBP12 potentiates IP3R activity. In other studies FKBP12 may inhibit channel activity and removal of FKBP12 from the channel increased IP3R-mediated Ca2+ release (Cameron et al., 1995b; Cameron et al., 1997).

FKBP12 also associates with RyR2 and RyR3 (Bultynck et al., 2001a; MacMillan et al., 2008) and with the skeletal muscle isoform, RyR1 (e.g. Carmody et al., 2001). An association between FKBP12.6 and RyR occurs in tracheal, pulmonary and coronary artery smooth muscle (e.g. Tang et al., 2002; Wang et al., 2004). RyR may be modulated by FKBPs to inhibit activity of the channel. Removal of FKBPs by either FK506 or rapamycin increased RyR channel open probability in lipid bilayers from coronary arterial smooth muscle (Tang et al., 2002) and cardiac muscle (Kaftan et al., 1996) or [Ca2+]cyto in intestinal, colonic, bladder and pulmonary artery myocytes (Weidelt and Isenberg, 2000; Zheng et al., 2004; MacMillan et al., 2008). Conversely rebinding either FKBP12 or FKBP12.6, following their removal, decreases channel opening (Brillantes et al., 1994; Barg et al., 1997; Bultynck et al., 2001b).

However, evidence is not universally supportive of a role of FKBPs in regulating either RyR or IP3R activity. In some studies no interaction between either RyR (Carmody et al., 2001; Wang et al., 2004; Zheng et al., 2004) or IP3R (Bultynck et al., 2001a; Carmody et al., 2001; Zheng et al., 2004) and FKBP12 occurred. Other studies failed to demonstrate an association between FKBP12.6 and either RyR (types 1&3) or IP3R (types 1–3) in pulmonary artery (Zheng et al., 2004). Functional studies also failed to detect any effect of FK506 or FKBP12 on IP3-mediated Ca2+ release in various cell types, including smooth muscle (Bultynck et al., 2000; Bultynck et al., 2001a). Neither did removal nor addition of FKBP12 or FKBP12.6 alter RyR channel function (Timerman et al., 1996; Barg et al., 1997; Xiao et al., 2007). Nor did FK506 alter Ca2+ release via RyR in porcine coronary artery (Yasutsune et al., 1999) or cardiac myocytes (duBell et al., 1997) or induce contraction in renal, mesenteric, coronary or carotid arteries (Epstein et al., 1998).

In addition to binding to the channel, FKBPs may modulate signaling pathways by regulating kinase and phosphatase activity. Thus FKBPs may modulate Ca2+ release either directly by binding to the channel or indirectly via the kinase and phosphatase pathways modulated by FKBP. The different signaling pathways regulated by FKBPs, may account, at least in part, for the contradictory findings on FKBP modulation of IP3R and RyR. For example, following the removal of FKBP from either IP3R or RyR by FK506, the FK506-FKBP complex formed binds to and inhibits the Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent serine/threonine phosphatase calcineurin (Liu et al., 1991) Indeed, calcineurin may regulate RyR and IP3R by forming part of the FKBP-channel complex (Cameron et al., 1995b; Cameron et al., 1995a; Cameron et al., 1997; Bandyopadhyay et al., 2000a; Shin et al., 2002). In support, calcineurin inhibitors increased caffeine- and ryanodine-induced Ca2+ release and the frequency and amplitude of Ca2+ oscillations in cardiac and skeletal muscle (Bandyopadhyay et al., 2000a; Shin et al., 2002). In COS-7 cells and cerebellar microsomes inhibition of calcineurin increased ATP-induced Ca2+ release and IP3R activity respectively (Cameron et al., 1995a; Bandyopadhyay et al., 2000b).

Calcineurin may also regulate Ca2+ release via RyR (Bultynck et al., 2003; MacMillan et al., 2008) or IP3R (Bultynck et al., 2003) independently of FKBPs or not at all (Kanoh et al., 1999). Indeed, the comparatively few studies in vascular smooth muscle failed to confirm a role for calcineurin in regulating [Ca2+]cyto. Drugs which can inhibit calcineurin, cypermethrin and okadaic acid, for example, did not alter Ca2+ release via either RyR (MacMillan et al., 2008) or IP3R (MacMillan and McCarron, unpublished data) in aortic myocytes. Neither did okadaic acid alter [Ca2+]cyto in porcine coronary artery (Ashizawa et al., 1989; Hirano et al., 1989). Cyclosporin A, a calcineurin inhibitor which does not interact with FKBPs, did not alter [Ca2+]cyto in pulmonary (Zheng et al., 2004) and coronary artery myocytes (Frapier et al., 2001) or SR [Ca2+] in aorta myocytes (Avdonin et al., 1999).

Rapamycin, a structural analogue of FK506, also binds to FKBP12 resulting in the formation of a rapamycin-FKBP12 complex. This complex does not inhibit calcineurin but binds to FKBP12-rapamycin-associated protein (Heitman et al., 1991; Peterson et al., 2000) also named mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) and inhibits its function (Brown et al., 1995). mTOR is a 289 kDa serine/threonine protein kinase and classified as a member of the phosphatidylinositol kinase-related kinase (PIKK) family. mTOR regulates a myriad of intracellular processes which include cell cycle progression and growth. Inhibition of mTOR by FKBP12-rapamycin may mediate the pharmacological actions of rapamycin (Brown et al., 1995; Sun et al., 2005) including the regulation of IP3-mediated Ca2+ release in colonic smooth muscle (MacMillan et al., 2005b).

In view of the controversy which surrounds the effects of the drugs FK506 and rapamycin and the mechanism of action of FKBPs on intracellular Ca2+ release in vascular smooth muscle the present study was carried out in single myocytes from portal vein. Cells were voltage-clamped to avoid [Ca2+]cyto changes which may have occurred via Ca2+ influx as a result of FK506- or rapamycin-evoked changes in membrane potential. The use of photolysed caged IP3, to activate IP3R, minimized the number of second messenger systems activated. This study has shown that pharmacological removal of FKBP from RyR with either FK506 or rapamycin, augmented caffeine-evoked Ca2+ release in portal vein myocytes. On the other hand, FK506 (FKBP-calcineurin inhibitor) augmented whereas rapamycin (mTOR inhibitor) reduced the IP3-evoked [Ca2+]cyto release. Neither cypermethrin nor okadaic acid (drugs which can inhibit calcineurin) altered caffeine- or IP3-evoked [Ca2+]cyto release. Thus, calcineurin is not required for the potentiation of RyR or IP3R Ca2+ release to occur. The mTOR inhibitor LY294002, like rapamycin, decreased IP3R Ca2+ release; mTOR inhibition may mediate the rapamycin-induced decrease in IP3R Ca2+ release. Our results, in portal vein myocytes, suggest that RyR- and IP3R-mediated Ca2+ release are modulated directly by FKBP. IP3R-mediated Ca2+ release may be additionally modulated by mTOR.

Methods

Preparation of portal vein myocytes

All animal care and experimental procedures complied with the Animal (Scientific Procedures) Act UK 1986. Male guinea pigs (500–700 g) were humanely killed by cervical dislocation and immediate exsanguination, and the portal vein was removed quickly and transferred to an oxygenated (95% O2–5% CO2) physiological saline solution of the following composition (mM): NaCl 118.4, NaHCO3 25, KCl 4.7, NaH2PO4 1.13, MgCl2 1.3, CaCl2 2.7 and glucose 11 (pH 7.4). From this tissue single vascular smooth muscle cells were isolated using a two-step enzymatic process. The vessel was initially treated (12 min at 34.5°C) with papain (1.7 mg·mL–1), DTT (0.7 mg·mL–1) and BSA (1.64 mg·mL–1) in a low Ca2+ solution which contained (mM): sodium glutamate, 80; NaCl, 55; KCl, 6; MgCl2, 1; CaCl2, 0·1; Hepes, 10; glucose, 10; 0·2, EDTA (to remove heavy metals) (pH 7·3). During a second incubation, the tissue was further digested (14 min at 34.5°C) in the low Ca2+ solution containing BSA (1.64 mg·mL–1), by collagenase (type F; 1.3–2 mg·mL–1) and hyaluronidase (0.8–1 mg·mL–1). The tissue was then rinsed several times with enzyme-free low Ca2+ solution containing BSA and then with the enzyme- and BSA-free low Ca2+ solution. Single smooth muscle cells were dispersed by trituration with a Pasteur pipette, stored at 4°C and used the same day. All experiments were conducted at room temperature (20–22°C).

Electrophysiological experiments

Cells were voltage clamped using conventional tight seal whole-cell recording (MacMillan et al., 2005a; 2008;). The composition of the extracellular solution was (mM): sodium glutamate 80, NaCl 40, tetraethylammonium chloride (TEA) 20, MgCl2 1.1, CaCl2 3, HEPES 10 and glucose 30 (pH 7.4 adjusted with NaOH 1M). The pipette solution contained (mM): Cs2SO4 85, CsCl 20, MgCl2 1, HEPES 30, pyruvic acid 2.5, malic acid 2.5, KH2PO4 1, MgATP 3, creatine phosphate 5, guanosine triphosphate 0.5, fluo-3 penta-ammonium salt 0.1 and caged Ins (1,4,5) P3-trisodium salt 0.025 (pH 7.2 adjusted with CsOH 1M). Whole cell currents were amplified by an Axopatch 1D amplifier (Axon instruments, Union City, CA, USA), low pass filtered at 500 Hz (8-pole bessel filter; Frequency Devices, Haverhill, MA, USA), and digitally sampled at 1.5 kHz using a Digidata interface, pCLAMP software (version 6.0.1, Axon Instruments) and stored on a personal computer for analysis.

Assay of [Ca2+]cyto

[Ca2+]cyto was measured as fluorescence using the membrane-impermeable dye fluo-3 (penta-ammonium salt) introduced into the cell via the patch pipette (MacMillan et al., 2005a,b;). Fluorescence was quantified using a microfluorimeter which consisted of an inverted microscope (Nikon diaphot) and a photomultiplier tube with a bi-alkali photo cathode. Fluo-3 was excited at 488 nm (bandpass 9 nm) from a PTI Delta Scan (Photon Technology International Inc., London, UK) through the epi-illumination port of the microscope (using one arm of a bifurcated quartz fibre optic bundle). Excitation light was passed through a field stop diaphragm to reduce background fluorescence and reflected off a 505 nm long-pass dichroic mirror. Emitted light was guided through a 535 nm barrier filter (bandpass 35 nm) to a photomultiplier in photon counting mode. Interference filters and dichroic mirrors were obtained from Glen Spectra (London, UK). To photolyse caged IP3 (25 µM) the output of a xenon flash lamp (Rapp Optoelektronik, Hamburg, Germany) was passed through a UG-5 filter to select UV light and merged into the excitation light path of the microfluorimeter using the second arm of the quartz bifurcated fibre optic bundle and applied to the caged compound. The nominal flash lamp energy was 57 mJ, measured at the output of the fibre optic bundle and the flash duration was approximately 1 ms. Fluorescence signals were expressed as ratios (F/F0) of fluorescence counts (F) relative to baseline (control) values (taken as 1) before stimulation (F0).

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as means ± SEM. Student's t-tests were applied to test and control conditions, a value of P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Materials

Caged Ins (1,4,5) P3-trisodium salt was purchased from Invitrogen (Paisley, UK). Fluo-3 penta-ammonium salt was purchased from TEF labs (Austin, Texas, USA). Rapamycin, cypermethrin and okadaic acid were each purchased from Calbiochem-Novabiochem (Beeston, Nottingham, UK) and papain was purchased from Worthington Biochemical Corporation (Lakewood, NJ, USA). All other reagents were purchased from Sigma (Poole, Dorset, UK). IP3 was released from its caged compound by flash photolysis. Caffeine (10 mM) was applied by hydrostatic pressure ejection using a pneumatic pump (PicoPump PV 820, World Precision Instruments, Stevenage, Herts, UK). The concentration of caged, non-photolysed IP3 refers to that in the pipette. Caffeine was dissolved in extracellular bathing solution, FK506 was dissolved in 100% ethanol (final bath concentration of the solvent, 0.05%, was by itself ineffective). Rapamycin, cypermethrin and okadaic acid were each dissolved in dimethyl sulphoxide (final bath concentration of the solvent, 0.01%, was by itself ineffective). Each drug (with the exception of caffeine) was perfused into the solution bathing the cells (∼5 mL per min). The calcineurin inhibitory peptide (CiP) based on the autoinhibitory fragment (ITSFEEAKGLDRINERMPPRRDAMP) was obtained from Sigma (Poole, UK) and introduced to the cell via the patch pipette filling solution.

Results

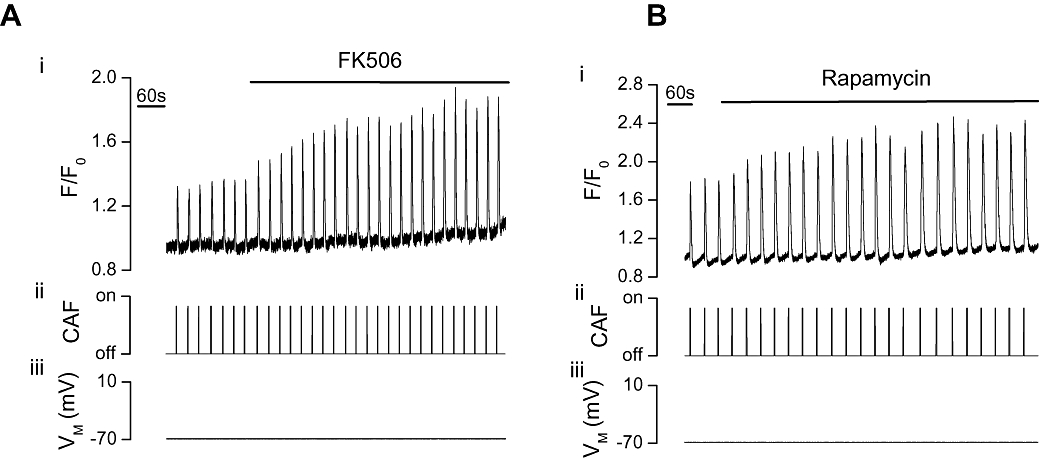

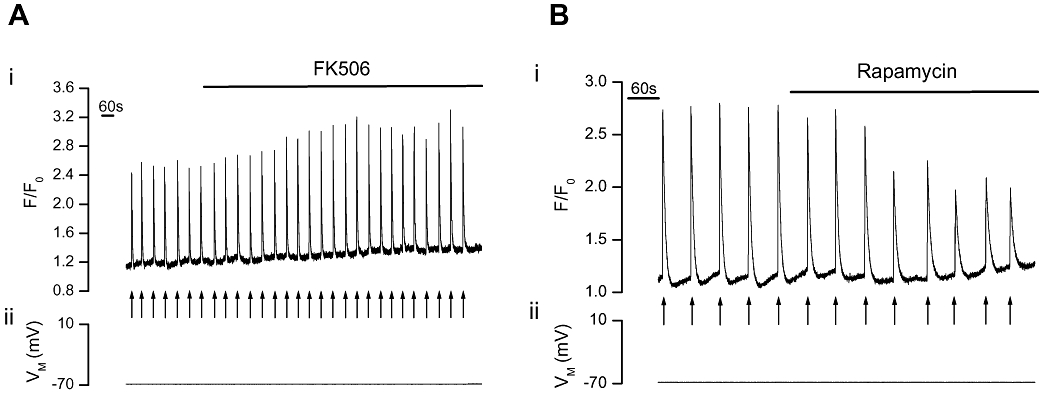

To determine the role of FKBPs in regulating Ca2+ release via RyRs and IP3Rs, the effects of FK506 and rapamycin, each of which disrupt the FKBP-channel association, were examined on caffeine- and IP3-induced Ca2+ release in voltage-clamped, single portal vein myocytes. Caffeine (10 mM), which activates RyR (Figure 1A), and photolysed caged IP3 (25 µM, Figure 2A), which activates IP3R, each reproducibly increased [Ca2+]cyto. FK506 (10 µM; Figure 1A) and rapamycin (10 µM; Figure 1B) each significantly (P < 0.05) increased caffeine-induced Ca2+ release (ΔF/F0) by 70 ± 11% and 59 ± 7% respectively [from 0.4 ± 0.02 (control) to 0.68 ± 0.08 (FK506, n= 3, Figure 1A) and 0.66 ± 0.11 (control) to 1.02 ± 0.16 (rapamycin, n= 7, Figure 1B)]. FK506 (10 µM; Figure 2A) also increased IP3-induced Ca2+ release by 30 ± 1% (ΔF/F0 from 0.93 ± 0.2 to 1.23 ± 0.2, n= 3). Rapamycin (10 µM; Figure 2B) on the other hand, significantly (P < 0.05) decreased the IP3-evoked Ca2+ transient (ΔF/F0) by 55 ± 8% from 1.78 ± 0.5 to 0.74 ± 0.14 (n= 3).

Figure 1.

FK506 or rapamycin increased the [Ca2+]cyto rise evoked by caffeine in voltage clamped single portal vein myocytes. At −70 mV (iii) caffeine (CAF, 10 mM, ii) increased [Ca2+]cyto (i) as indicated by F/F0. FK506 (10 µM, n= 3, P < 0.05, A) and rapamycin (10 µM, n= 7, P < 0.05, B) each significantly increased the caffeine-evoked [Ca2+]cyto transients (i). [Ca2+]cyto, cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentration; F, fluorescence counts; F0, baseline fluorescence counts.

Figure 2.

FK506 increased but rapamycin decreased IP3-evoked Ca2+ increases in voltage clamped single portal vein myocytes. At −70 mV (ii) photolysed caged IP3 (↑) increased [Ca2+]cyto (i) as indicated by F/F0. FK506 (10 µM, n= 3, P < 0.05, A) increased but rapamycin (10 µM, n= 3, P < 0.05, B) decreased the [Ca2+]cyto transients (i). [Ca2+]cyto, cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentration; F, fluorescence counts; F0, baseline fluorescence counts; IP3, inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate.

FK506 and rapamycin each form a complex with FKBP to disrupt binding of FKBP to IP3R and RyR. Disrupting FKBP binding to the channels is thus a feature which is common to the mechanism of action of both drugs. However, thereafter the action of the drug differs. The FK506-FKBP complex inhibits calcineurin whereas the rapamycin-FKBP complex inhibits mTOR. Therefore, the effects of FK506 and rapamycin on Ca2+ release may be either mediated by calcineurin or mTOR inhibition respectively, or by the removal of FKBP from the receptor.

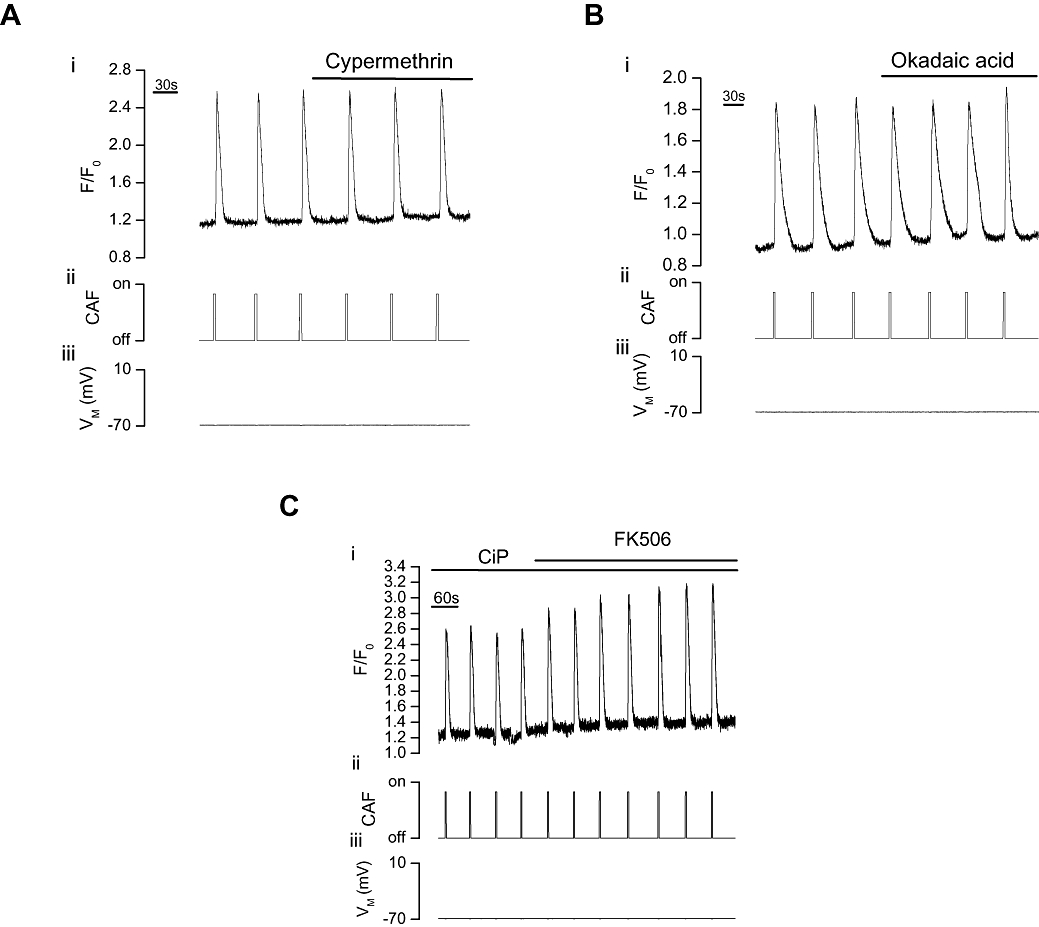

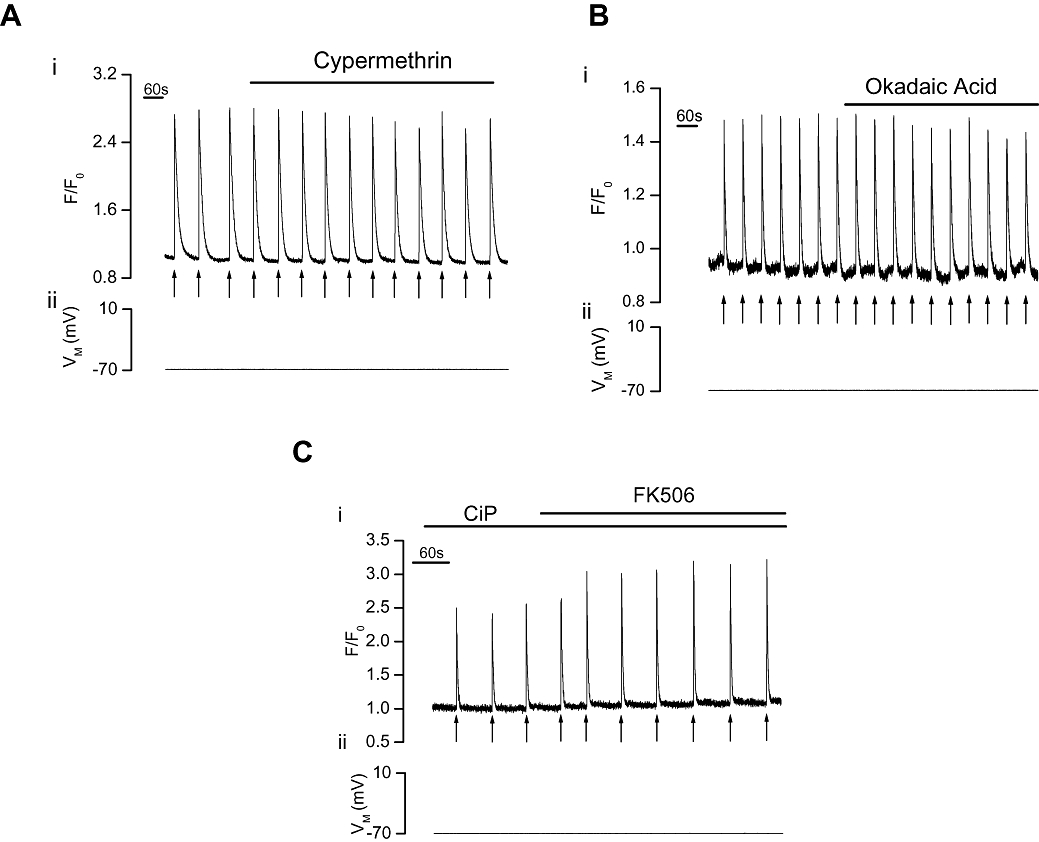

Role of calcineurin in FK506-evoked potentiation of Ca2+ release

If the potentiation of RyR activity by FK506 was explained by inhibition of calcineurin, then the potentiation should be mimicked by calcineurin inhibitors. However, drugs which can inhibit calcineurin, cypermethrin (10 µM; Figure 3A) or okadaic acid (5 µM; Figure 3B), failed to alter caffeine-evoked Ca2+ transients [(ΔF/F0) from 1.22 ± 0.25 (control) to 1.22 ± 0.26 (cypermethrin, n= 8, P > 0.05) and 0.65 ± 0.08 (control) to 0.65 ± 0.07 (okadaic acid, n= 5, P > 0.05) respectively]. Neither did the CiP prevent FK506 potentiation of caffeine-evoked Ca2+ release. CiP was administered into the cell via the pipette solution (because it is impermeant) and FK506 remained effective in increasing caffeine-evoked Ca2+ transients [(F/F0) from 0.9 ± 0.09 (control) to 1.33 ± 0.09 (FK506, n= 7, P < 0.05); Figure 3C].

Figure 3.

Effect of calcineurin inhibition on caffeine-evoked Ca2+ increases in voltage-clamped single portal vein myocytes. Caffeine (CAF, 10 mM, ii) increased [Ca2+]cyto (i) as indicated by F/F0. Neither cypermethrin (10 µM, n= 8, A) nor okadaic acid (5 µM, n= 5, B) significantly (P > 0.05) altered the caffeine-evoked [Ca2+]cyto transients (VM−70 mV, iii). Following pretreatment with the calcineurin inhibitor CiP (100 µM, C) via the patch pipette filling solution, FK506 (10 µM) still significantly (P < 0.05) increased the caffeine-evoked [Ca2+]cyto transients (VM−70 mV, iii, n= 7). [Ca2+]cyto, cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentration; CiP, calcineurin inhibitory peptide; F, fluorescence counts; F0, baseline fluorescence counts.

If the potentiation of IP3-mediated Ca2+ release by FK506 arose by inhibition of calcineurin, then inhibitors of the phosphatase should increase IP3-mediated Ca2+ release. However, again, neither cypermethrin (10 µM; Figure 4A) nor okadaic acid (5 µM; Figure 4B) increased IP3-mediated Ca2+ release [(ΔF/F0) (from 2.02 ± 0.21 (control) to 2.03 ± 0.21 (cypermethrin, n= 5, P > 0.05) and 1.21 ± 0.19 (control) to 1.16 ± 0.19 (okadaic acid, n= 6, P > 0.05)]. Following calcineurin inhibition with CiP (Figure 4C), FK506 also remained effective in increasing IP3-evoked Ca2+ transients [(F/F0) from 1.39 ± 0.12 (control) to 2.00 ± 0.15 (FK506, n= 6, P < 0.05)].

Figure 4.

Effect of calcineurin inhibition on IP3-evoked Ca2+ increases in voltage-clamped single portal vein myocytes. Photolysed caged IP3 (↑) increased [Ca2+]cyto (i) as indicated by F/F0. Neither cypermethrin (10 µM, n= 5, A) nor okadaic acid (5 µM, n= 6, B) significantly (P > 0.05) altered the IP3-evoked [Ca2+]cyto transients (VM−70 mV, ii). Following pretreatment with the calcineurin inhibitor CiP (100 µM, C), via the patch pipette filling solution, FK506 (10 µM) still significantly (P < 0.05) increased the IP3-evoked [Ca2+]cyto transients produced by photolysed caged IP3 (VM−70 mV, ii, n= 6). [Ca2+]cyto, cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentration; CiP, calcineurin inhibitory peptide; F, fluorescence counts; F0, baseline fluorescence counts; IP3, inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate.

Role of mTOR in rapamycin-evoked suppression of IP3-mediated Ca2+ release

Interestingly, removal of FKBP by rapamycin decreased IP3-mediated Ca2+ release. The decrease is unlikely to be explained by a reduction in the store's Ca2+ content by rapamycin's inhibition of the sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase (SERCA; Bultynck et al., 2000; Loughrey et al., 2007), because the Ca2+ transient in response to RyR activation with caffeine was significantly (P < 0.05) increased by the drug (Figure 1B). Had rapamycin inhibited SERCA the caffeine-evoked [Ca2+]cyto rise would also have been reduced. Furthermore, inhibition of SERCA pump activity should increase steady-state [Ca2+]cyto (Bultynck et al., 2000). No increase in steady-state [Ca2+]cyto (measured as fluorescence) was observed either following FK506 [(F/F0) from 1.06 ± 0.05 (control) to 1.09 ± 0.07 (FK506, n= 6, P > 0.05)] or rapamycin [(F/F0) from 1.07 ± 0.04 (control) to 1.08 ± 0.04 (rapamycin, n= 10, P > 0.05)]. Moreover, neither FK506 nor rapamycin significantly altered the rate of Ca2+ removal from the cytoplasm following each of IP3- or caffeine-evoked Ca2+ release. The 80–20% decay interval following IP3- and caffeine-evoked Ca2+ release was 4.0 ± 1.0 s and 6.2 ± 1.4 s in controls and 4.7 ± 1.2 s and 6.3 ± 1.5 s in FK506, (each n= 3, P > 0.05) respectively. Similarly, the 80–20% decay interval following IP3- and caffeine-evoked Ca2+ release was 5.8 ± 0.2 s and 6.2 ± 0.6 s in controls and 6.5 ± 0.9 s and 6.4 ± 0.5 s in rapamycin, (n= 3 and 7, P > 0.05) respectively.

Rapamycin-FKBP-mediated inhibition of mTOR may explain the inhibition of IP3-mediated Ca2+ release. To test this, the effect of the mTOR inhibitor LY294002 (inhibits mTOR without first binding to FKBP) was examined on IP3-evoked Ca2+ release. If the rapamycin-induced decrease in IP3-mediated Ca2+ release arose by inhibition of mTOR, then an inhibitor of the kinase should also decrease IP3-mediated Ca2+ release. LY294002 (20 µM; Figure 5) significantly (P < 0.05) decreased the IP3-evoked Ca2+ transient (ΔF/F0) by 52 ± 12% from 2.64 ± 0.4 to 1.24 ± 0.3 (n= 4).

Figure 5.

The mTOR inhibitor LY294002 decreased IP3-evoked Ca2+ increases in voltage clamped single portal vein myocytes. Photolysed caged IP3 (↑) increased [Ca2+]cyto (i) as indicated by F/F0. Addition of LY294002 (20 µM, n= 4, P < 0.05) decreased the IP3-evoked [Ca2+]cyto transients (i) (VM−70 mV, ii). [Ca2+]cyto, cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentration; F, fluorescence counts; F0, baseline fluorescence counts; IP3, inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin.

Discussion and conclusions

FK506 and rapamycin exert multiple effects on intracellular signaling via their effects on FKBP binding to RyRs and IP3Rs, and by regulating the phosphatase calcineurin and the kinase mTOR. The multiple effects of the drugs explain the present results and account for apparently contradictory findings which exist in the literature on the role of FKBPs in Ca2+ signaling. The present study, in portal vein myocytes, suggests RyR is modulated directly by FKBP to decrease Ca2+ release via the channel. Neither calcineurin nor mTOR are required for FKBP modulation of RyR activity to occur. IP3R activity, like RyR, is modulated directly by FKBP but, unlike RyR, also indirectly via the kinase mTOR. FKBP binding to IP3R decreases Ca2+ release while inhibition of mTOR, by the FKBP-rapamycin complex, additionally decreases IP3-mediated Ca2+ release.

An association between FKBPs and either RyR or IP3R to regulate the activities of the channels has been reported in various cell types (e.g. Carmody et al., 2001; MacMillan et al., 2005b; 2008;) including vascular smooth muscle (Tang et al., 2002; Zheng et al., 2004). However, FKBPs may increase (Dargan et al., 2002; Su et al., 2003; MacMillan et al., 2005b), decrease (Cameron et al., 1995b; Zheng et al., 2004; MacMillan et al., 2008) or have no effect on channel activity (Barg et al., 1997; duBell et al., 1997; Kanoh et al., 1999; Yasutsune et al., 1999; Bultynck et al., 2000). The drugs FK506 and rapamycin each inhibit FKBP association with IP3R and RyR but differ in that the FK506-FKBP complex inhibits calcineurin (Liu et al., 1991) whereas the rapamycin-FKBP complex inhibits mTOR (Brown et al., 1995). Therefore, the effects of FK506 and rapamycin may be either mediated by calcineurin or mTOR inhibition respectively, or by the removal of FKBP from the channels.

In the present study while FK506 increased, drugs which can inhibit calcineurin (cypermethrin or okadaic acid) failed to alter caffeine- or IP3-evoked Ca2+ release. FK506 also remained effective in increasing the caffeine- and IP3-evoked Ca2+ transients in the presence of CiP. These results suggest that calcineurin is unlikely to contribute to the FK506-induced potentiation of caffeine- or IP3-evoked Ca2+ increases in portal vein. Had it done so the calcineurin inhibitors would have increased Ca2+ release and the effect of FK506 would have been inhibited. As FK506 and rapamycin each increased caffeine-induced Ca2+ release, a mechanism common to the action of both drugs, i.e. FKBP removal from the FKBP-RyR complex, may explain the increased Ca2+ release in the present study. This finding is consistent with our own previous results in colonic smooth muscle (MacMillan et al., 2008) and those of other investigators in various tissues which suggest that FK506 and rapamycin each increase the activity of RyR by disrupting FKBP-RyR association (Brillantes et al., 1994; Kaftan et al., 1996; Bultynck et al., 2000; Weidelt and Isenberg, 2000; Xiao et al. 2007).

On the other hand, while FK506 increased, rapamycin decreased IP3-mediated Ca2+ release. The target for the rapamycin-FKBP12 complex has been identified as the kinase mTOR (Sabatini et al., 1994; Brown et al., 1995). The rapamycin-induced reduction in IP3-mediated Ca2+ release in the present study may be mediated by inhibition of mTOR. In support, the inhibitor LY294002 which inhibits PI-3 kinase and mTOR (Brunn et al., 1996), but does not remove FKBP from the channel, reduced the IP3-mediated Ca2+ release. As LY294002 mimicked the effects of rapamycin, inhibition of IP3-mediated Ca2+ release by rapamycin may be mediated by mTOR. Thus, in addition to regulating vascular smooth muscle cell differentiation, proliferation and migration our study suggests mTOR also regulates Ca2+ release in vascular (portal vein) smooth muscle.

In addition to mTOR regulation of IP3-mediated Ca2+ release, the present study has also shown that FKBP may modulate IP3R directly in portal vein myocytes. This conclusion is derived from the finding that FK506 but not calcineurin inhibitors increased IP3-mediated Ca2+ release. In our previous study in colonic smooth muscle, FKBP had little direct effect on IP3-mediated Ca2+ release but indirectly modulated Ca2+ release through mTOR, to increase, and calcineurin, to inhibit, Ca2+ release (MacMillan et al., 2005b). Apart from the differences in the tissues used in the two studies, experimental conditions were otherwise identical. FKBPs, calcineurin and mTOR may each regulate RyR and IP3R differently in various tissues and calcineurin appears to regulate neither IP3R or RyR in portal vein. Similar findings were obtained in other vascular tissues. Calcineurin did not alter [Ca2+]cyto in coronary (Ashizawa et al., 1989; Hirano et al., 1989) and pulmonary (Zheng et al., 2004) arteries nor SR [Ca2+] in aorta myocytes (Avdonin et al., 1999). Yet, the differences in IP3R regulation by FKBP and calcineurin between colonic and portal vein myocytes, are not explained simply by peculiarities of vascular and gastrointestinal smooth muscle. We have investigated RyR and IP3R regulation in two types of vascular smooth muscle and, again, interesting differences exist. While FKBP modulated RyR and IP3R in portal vein, it neither modulated Ca2+ release or even associated with either RyR or IP3R in aorta (MacMillan et al., 2005b; 2008;). Clearly, substantial tissue to tissue variation exists in the regulation of RyR and IP3R by FKBPs and the effects of compounds such as FK506 and rapamycin.

In summary, the present study, in portal vein myocytes, suggest RyR-mediated Ca2+ release is modulated directly by FKBP as a result of the binding of the accessory protein to the channel. IP3-mediated Ca2+ release may be modulated by both FKBP binding to IP3R and also indirectly via the kinase mTOR. FK506 increased RyR and IP3R channel activity whereas rapamycin decreased IP3R activity. The opposing effects of FK506 and rapamycin on IP3-mediated Ca2+ release suggest different roles for FKBPs and mTOR in IP3R-mediated Ca2+ release in portal vein myocytes; FKBPs decrease RyR and IP3R activity whereas mTOR increases IP3R activity.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the Wellcome Trust (078054/2/05/Z) and the British Heart Foundation (PG/08/066), the support of which is gratefully acknowledged.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- [Ca2+]cyto

cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentration

- CiP

calcineurin inhibitory peptide

- F

fluorescence counts

- F0

baseline fluorescence counts

- FKBPs

FK506-binding proteins

- IP3

inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate

- IP3R

inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor

- mTOR

mammalian target of rapamycin

- RyR

ryanodine receptor

- SERCA

sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase

- SR

sarcoplasmic reticulum

Conflicts of interest

None.

References

- Alexander SP, Mathie A, Peters JA. Guide to Receptors and Channels (GRAC), 3rd edition. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153:S1–209. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashizawa N, Kobayashi F, Tanaka Y, Nakayama K. Relaxing action of okadaic acid, a black sponge toxin on the arterial smooth muscle. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1989;162:971–976. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(89)90768-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avdonin PV, Cottet-Maire F, Afanasjeva GV, Loktionova SA, Lhote P, Ruegg UT. Cyclosporine A up-regulates angiotensin II receptors and calcium responses in human vascular smooth muscle cells. Kidney Int. 1999;55:2407–2414. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandyopadhyay A, Shin DW, Ahn JO, Kim DH. Calcineurin regulates ryanodine receptor/Ca2+-release channels in rat heart. Biochem J. 2000a;352:61–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandyopadhyay A, Shin DW, Kim DH. Regulation of ATP-induced calcium release in COS-7 cells by calcineurin. Biochem J. 2000b;348:173–181. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barg S, Copello JA, Fleischer S. Different interactions of cardiac and skeletal muscle ryanodine receptors with FK-506 binding protein isoforms. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:C1726–1733. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.272.5.C1726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bootman MD, Collins TJ, Peppiatt CM, Prothero LS, MacKenzie L, De Smet P, et al. Calcium signalling – an overview. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2001;12:3–10. doi: 10.1006/scdb.2000.0211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brillantes AB, Ondrias K, Scott A, Kobrinsky E, Ondriasova E, Moschella MC, et al. Stabilization of calcium release channel (ryanodine receptor) function by FK506-binding protein. Cell. 1994;77:513–523. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90214-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown EJ, Beal PA, Keith CT, Chen J, Shin TB, Schreiber SL. Control of p70 s6 kinase by kinase activity of FRAP in vivo. Nature. 1995;377:441–446. doi: 10.1038/377441a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunn GJ, Williams J, Sabers C, Wiederrecht G, Lawrence JC, Jr., Abraham RT. Direct inhibition of the signaling functions of the mammalian target of rapamycin by the phosphoinositide 3-kinase inhibitors, wortmannin and LY294002. Embo J. 1996;15:5256–5267. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bultynck G, De Smet P, Rossi D, Callewaert G, Missiaen L, Sorrentino V, et al. Characterization and mapping of the 12 kDa FK506-binding protein (FKBP12)-binding site on different isoforms of the ryanodine receptor and of the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor. Biochem J. 2001a;354:413–422. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3540413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bultynck G, De Smet P, Weidema AF, Ver Heyen M, Maes K, Callewaert G, et al. Effects of the immunosuppressant FK506 on intracellular Ca2+ release and Ca2+ accumulation mechanisms. J Physiol. 2000;525:681–693. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-1-00681.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bultynck G, Rossi D, Callewaert G, Missiaen L, Sorrentino V, Parys JB, et al. The conserved sites for the FK506-binding proteins in ryanodine receptors and inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors are structurally and functionally different. J Biol Chem. 2001b;276:47715–47724. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106573200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bultynck G, Vermassen E, Szlufcik K, De Smet P, Fissore RA, Callewaert G, et al. Calcineurin and intracellular Ca2+-release channels: regulation or association? Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;311:1181–1193. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.08.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burdyga T, Wray S. Action potential refractory period in ureter smooth muscle is set by Ca sparks and BK channels. Nature. 2005;436:559–562. doi: 10.1038/nature03834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron AM, Nucifora FC, Jr., Fung ET, Livingston DJ, Aldape RA, Ross CA, et al. FKBP12 binds the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor at leucine-proline (1400–1401) and anchors calcineurin to this FK506-like domain. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:27582–27588. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.44.27582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron AM, Steiner JP, Roskams AJ, Ali SM, Ronnett GV, Snyder SH. Calcineurin associated with the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor-FKBP12 complex modulates Ca2+ flux. Cell. 1995a;83:463–472. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90124-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron AM, Steiner JP, Sabatini DM, Kaplin AI, Walensky LD, Snyder SH. Immunophilin FK506 binding protein associated with inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor modulates calcium flux. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995b;92:1784–1788. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.5.1784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmody M, Mackrill JJ, Sorrentino V, O'Neill C. FKBP12 associates tightly with the skeletal muscle type 1 ryanodine receptor, but not with other intracellular calcium release channels. FEBS Lett. 2001;505:97–102. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02787-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dargan SL, Lea EJ, Dawson AP. Modulation of type-1 Ins(1,4,5)P3 receptor channels by the FK506-binding protein, FKBP12. Biochem J. 2002;361:401–407. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3610401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- duBell WH, Wright PA, Lederer WJ, Rogers TB. Effect of the immunosupressant FK506 on excitation-contraction coupling and outward K+ currents in rat ventricular myocytes. J Physiol. 1997;501:509–516. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.509bm.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein A, Beall A, Wynn J, Mulloy L, Brophy CM. Cyclosporine, but not FK506, selectively induces renal and coronary artery smooth muscle contraction. Surg. 1998;123:456–460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frapier JM, Choby C, Mangoni ME, Nargeot J, Albat B, Richard S. Cyclosporin A increases basal intracellular calcium and calcium responses to endothelin and vasopressin in human coronary myocytes. FEBS Lett. 2001;493:57–62. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02269-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding MW, Galat A, Uehling DE, Schreiber SL. A receptor for the immunosuppressant FK506 is a cis-trans peptidyl-prolyl isomerase. Nature. 1989;341:758–760. doi: 10.1038/341758a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heitman J, Movva NR, Hall MN. Targets for cell cycle arrest by the immunosuppressant rapamycin in yeast. Science. 1991;253:905–909. doi: 10.1126/science.1715094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano K, Kanaide H, Nakamura M. Effects of okadaic acid on cytosolic calcium concentrations and on contractions of the porcine coronary artery. Br J Pharmacol. 1989;98:1261–1266. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1989.tb12672.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaftan E, Marks AR, Ehrlich BE. Effects of rapamycin on ryanodine receptor/Ca2+-release channels from cardiac muscle. Circ Res. 1996;78:990–997. doi: 10.1161/01.res.78.6.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanoh S, Kondo M, Tamaoki J, Shirakawa H, Aoshiba K, Miyazaki S, et al. Effect of FK506 on ATP-induced intracellular calcium oscillations in cow tracheal epithelium. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:L891–L899. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1999.276.6.L891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Farmer JD, Jr., Lane WS, Friedman J, Weissman I, Schreiber SL. Calcineurin is a common target of cyclophilin-cyclosporin A and FKBP-FK506 complexes. Cell. 1991;66:807–815. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90124-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loughrey CM, Otani N, Seidler T, Craig MA, Matsuda R, Kaneko N, et al. K201 modulates excitation-contraction coupling and spontaneous Ca2+ release in normal adult rabbit ventricular cardiomyocytes. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;76:236–246. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarron JG, Chalmers S, Bradley KN, MacMillan D, Muir TC. Ca2+ microdomains in smooth muscle. Cell Calcium. 2006;40:461–493. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2006.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacMillan D, Chalmers S, Muir TC, McCarron JG. IP3-mediated Ca2+ increases do not involve the ryanodine receptor, but ryanodine receptor antagonists reduce IP3-mediated Ca2+ increases in guinea-pig colonic smooth muscle cells. J Physiol. 2005a;569:533–544. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.096529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacMillan D, Currie S, Bradley KN, Muir TC, McCarron JG. In smooth muscle, FK506-binding protein modulates IP3 receptor-evoked Ca2+ release by mTOR and calcineurin. J Cell Sci. 2005b;118:5443–5451. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacMillan D, Currie S, McCarron JG. FK506-binding protein (FKBP12) regulates ryanodine receptor-evoked Ca2+ release in colonic but not aortic smooth muscle. Cell Calcium. 2008;43:539–549. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson RT, Beal PA, Comb MJ, Schreiber SL. FKBP12-rapamycin-associated protein (FRAP) autophosphorylates at serine 2481 under translationally repressive conditions. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:7416–7423. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.10.7416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabatini DM, Erdjument-Bromage H, Lui M, Tempst P, Snyder SH. RAFT1: a mammalian protein that binds to FKBP12 in a rapamycin-dependent fashion and is homologous to yeast TORs. Cell. 1994;78:35–43. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90570-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scaramello CB, Muzi-Filho H, Zapata-Sudo G, Sudo RT, Cunha Vdo M. FKBP12 depletion leads to loss of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ stores in rat vas deferens. J Pharmacol Sci. 2009;109:185–192. doi: 10.1254/jphs.08064fp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin DW, Pan Z, Bandyopadhyay A, Bhat MB, Kim DH, Ma J. Ca2+-dependent interaction between FKBP12 and calcineurin regulates activity of the Ca2+ release channel in skeletal muscle. Biophys J. 2002;83:2539–2549. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75265-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su Z, Sugishita K, Li F, Ritter M, Barry WH. Effects of FK506 on [Ca2+]i differ in mouse and rabbit ventricular myocytes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;304:334–341. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.041210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun SY, Rosenberg LM, Wang X, Zhou Z, Yue P, Fu H, et al. Activation of Akt and eIF4E survival pathways by rapamycin-mediated mammalian target of rapamycin inhibition. Cancer Res. 2005;65:7052–7058. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang WX, Chen YF, Zou AP, Campbell WB, Li PL. Role of FKBP12.6 in cADPR-induced activation of reconstituted ryanodine receptors from arterial smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;282:H1304–1310. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00843.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timerman AP, Onoue H, Xin HB, Barg S, Copello J, Wiederrecht G, et al. Selective binding of FKBP12.6 by the cardiac ryanodine receptor. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:20385–20391. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.34.20385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang YX, Zheng YM, Mei QB, Wang QS, Collier ML, Fleischer S, et al. FKBP12.6 and cADPR regulation of Ca2+ release in smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2004;286:C538–C546. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00106.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weidelt T, Isenberg G. Augmentation of SR Ca2+ release by rapamycin and FK506 causes K+-channel activation and membrane hyperpolarization in bladder smooth muscle. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;129:1293–1300. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao J, Tian X, Jones PP, Bolstad J, Kong H, Wang R, et al. Removal of FKBP12.6 does not alter the conductance and activation of the cardiac ryanodine receptor or the susceptibility to stress-induced ventricular arrhythmias. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:34828–34838. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707423200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasutsune T, Kawakami N, Hirano K, Nishimura J, Yasui H, Kitamura K, et al. Vasorelaxation and inhibition of the voltage-operated Ca2+ channels by FK506 in the porcine coronary artery. Br J Pharmacol. 1999;126:717–729. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng YM, Mei QB, Wang QS, Abdullaev I, Lai FA, Xin HB, et al. Role of FKBP12.6 in hypoxia- and norepinephrine-induced Ca2+ release and contraction in pulmonary artery myocytes. Cell Calcium. 2004;35:345–355. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2003.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]