Abstract

In replicating yeast, lysine 63-linked polyubiquitin (polyUb) chains are extended from the ubiquitin moiety of monoubiquitinated proliferating cell nuclear antigen (monoUb-PCNA) by the E2-E3 complex of (Ubc13-Mms2)-Rad5. This promotes error-free bypass of DNA damage lesions. The unusual ability of Ubc13-Mms2 to synthesize unanchored Lys63-linked polyUb chains in vitro allowed us to resolve the individual roles that it and Rad5 play in the catalysis and specificity of PCNA polyubiquitination. We found that Rad5 stimulates the synthesis of free polyUb chains by Ubc13-Mms2 in part by enhancing the reactivity of the Ubc13∼Ub thiolester bond. Polyubiquitination of monoUb-PCNA was further enhanced by interactions between the N-terminal domain of Rad5 and PCNA. Thus, Rad5 acts both to align monoUb-PCNA with Ub-charged Ubc13 and to stimulate Ub transfer onto Lys63 of a Ub acceptor. We also found that Rad5 interacts with PCNA independently of the number of monoubiquitinated subunits in the trimer and that it binds to both unmodified and monoUb-PCNA with similar affinities. These findings indicate that Rad5-mediated recognition of monoUb-PCNA in vivo is likely to depend upon interactions with additional factors at stalled replication forks.

DNA is susceptible to chemical alteration by many endogenous and exogenous agents. To counter this threat and maintain genome integrity, eukaryotic cells employ three main strategies: DNA repair pathways that directly reverse DNA damage, cell cycle checkpoints that allow time to repair the damage prior to replication, and DNA damage tolerance (DDT),2 which is a method of bypassing DNA damage lesions during the DNA replication phase of the cell cycle.

Proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) is a key regulatory protein in DNA replication and repair (1). At the replication fork, DNA is encircled by PCNA, a homotrimeric protein that promotes processive movement of the replicative DNA polymerase. Upon DNA damage and subsequent stalling of the replicative polymerase, Ub modifications of PCNA signal DDT, which allows a cell to bypass the lesion and proceed past this potential block in replication (2–4).

In the DDT pathway, as in other Ub-dependent pathways, Ub is conjugated to a substrate by the actions of three enzymes, an E1 activating enzyme, an E2 conjugating enzyme, and an E3 ligase (5). The E1 enzyme initiates the pathway in a two-step reaction that utilizes ATP hydrolysis to activate the C terminus of Ub, culminating in the formation of an E1∼Ub thiolester. Subsequent transthiolation to the active site cysteine of the E2 generates an E2∼Ub thiolester. An E3 ligase then brings a substrate into close proximity to the E2∼Ub intermediate, thereby catalyzing the formation of an isopeptide bond between the amino group of a substrate lysine and the C-terminal glycine of Ub. Polyubiquitination occurs when this substrate is another Ub, either free or as part of a Ub-protein conjugate.

The DDT pathway is characterized by distinct ubiquitination events on PCNA that occur in two stages (3, 4, 6). The first of these is monoubiquitination of lysine 164 on one or more of the PCNA subunits by the E2-E3 complex of Rad6-Rad18 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (3, 4, 7). monoUb-PCNA can serve either as a signal for error-prone bypass of the DNA lesion by recruiting translesion polymerases or as a substrate for subsequent polyubiquitination by the E2 heterodimer Ubc13-Mms2 and the E3 ligase Rad5 (3, 4, 8, 9). The polyUb chain extended from the initial Ub moiety on monoUb-PCNA is linked specifically through Ub Lys63 residues. This Lys63-linked chain is thought to enable a template switch mechanism that allows for error-free bypass of the DNA lesion, in part by utilizing the single-strand DNA-dependent helicase activity of Rad5 (3, 4, 10, 11). Both PCNA ubiquitination events promote bypass of the DNA lesion rather than direct removal or repair of the lesion.

We have been interested in the mechanism by which the yeast (Ubc13-Mms2)-Rad5 complex catalyzes the formation of Lys63-linked polyUb on PCNA. Previous studies have shown that heterodimerization of the Ubc13-Mms2 E2 is essential for Lys63-specific Ub-Ub conjugation in vitro and in vivo (12–15). Ubc13 is a canonical E2 enzyme with an active site cysteine that receives activated Ub by transthiolation from the E1∼Ub complex (12, 13). This Ub is referred to as the “donor Ub.” Mms2 is a Ub E2 variant protein that lacks the active site cysteine (12, 15); rather, Mms2 binds to a second Ub, the “acceptor Ub,” and positions it to facilitate nucleophilic attack on the Ubc13∼Ub thiolester bond by the ϵ-amine of Lys63 (15, 16). The positioning of the acceptor Ub by Mms2 controls the specificity of polyUb assembly such that only Lys63-linked chains can be formed (16).

Ubc13-Mms2 can synthesize Lys63-linked chains in vitro in the absence of a PCNA substrate or an E3 ligase (12, 13). However, unlike the synthesis of free Lys63-linked polyUb chains by Ubc13-Mms2, little is known about the polyubiquitination of PCNA or the role of the Rad5 E3 ligase in these reactions. Rad5 can bind PCNA and Rad18, and it contains a catalytic RING domain that characterizes the largest class of E3 ligases (17–21). There is evidence that RING E3s like Rad5 may play a more active role in ubiquitination than simply bringing the substrate into close proximity with the E2∼Ub. Several RING E3s have been shown to stimulate the synthesis of unanchored polyUb chains or autoubiquitination of their cognate E2s in the absence of substrates (22–24). This stimulation may be related to the ability of RING E3s to enhance reactivity of the E2∼Ub thiolester bond through allosteric effects (25, 26).

Using purified recombinant forms of Ubc13, Mms2, and Rad5, we have explored the assembly of free Lys63-linked polyUb chains as well as the extension of a polyUb chain on a synthetic analog of monoUb-PCNA. We show that Rad5 facilitates ubiquitination in part by increasing the reactivity of the Ubc13∼Ub thiolester bond. With monoUb-PCNA substrates, Rad5 also stimulated polyubiquitination through direct interactions with PCNA and recruitment of Ub-charged Ubc13-Mms2. Surprisingly, Rad5 recognition of monoUb-PCNA appeared to depend on interactions only with the PCNA moiety of the conjugate, which suggests that substrate selectivity in vivo is likely to depend on additional factors.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Plasmids

The RAD5 gene coding sequence was PCR-amplified from S. cerevisiae genomic DNA and cloned into pFastBacDual (Invitrogen) with either a H6 or FLAG N-terminal tag. The I916A mutation was introduced into pFastBacDual (FLAG-Rad5) by standard PCR methods. The yeast Ub gene was modified and cloned into the pET3a vector (Novagen) to make pET3a (H6Ub(G76C)). All of the inserts were sequenced at the Johns Hopkins Biosynthesis and Sequencing Facility. pET11a (FLAG-PCNA(C22A,C30A,C62A,C81A,K164C)) was a gift from Todd Washington (University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA).

Proteins

Insect cell expression and purification of murine H6-E1, and bacterial expression and purification of Ub, Ub(K63R), Ub-D77, Ubc13, Ubc13(N79A), Ubc13(N79Q), and Mms2 have been described (12, 27–29). Ub(K63R) was radioiodinated as described (27). H6-Rad5, FLAG-Rad5, and FLAG-Rad5(I916A) were expressed in Sf21 insect cells using the Bac-to-Bac baculovirus system (Invitrogen). H6-Rad5-containing Sf21 cells were lysed in 50 mm Tris, pH 8.0, 0.5 m NaCl, 2 mm β-mercaptoethanol, and 0.02% Triton X-100. Clarified lysate was loaded onto a 1-ml nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid-agarose (Qiagen) column, and bound proteins were washed with 50 mm Tris, pH 8.0, 2 mm β-mercaptoethanol, 0.5 m NaCl, and 10 mm imidazole. H6-Rad5 was eluted in wash buffer supplemented with 200 mm imidazole. H6-Rad5 was further purified by size exclusion chromatography (Superose 6; GE Healthcare) in 50 mm Tris, pH 8.0, 100 mm NaCl, 2 mm β-mercaptoethanol. FLAG-Rad5 and FLAG-Rad5(I916A)-expressing insect cells were lysed similarly, and proteins were bound to anti-FLAG resin (M2 antibody agarose; Sigma), eluted with 0.2 mg/ml FLAG peptide, and further purified by gel filtration as above.

H6-Ub(G76C)-expressing bacterial cells were lysed as with recombinant wild-type Ub (27), except that 1 mm TCEP (Sigma) was added to the lysis buffer. The protein was purified on nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid-agarose as described above. Anti-polyhistidine antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, and anti-FLAG M2 antibodies were from Sigma.

BL21(DE3) cells expressing FLAG-PCNA(C22A,C30A,C62A,C81A,K164C) (hereafter referred to as FLAG-PCNA) were lysed in 50 mm Tris, pH 7.6, 100 mm NaCl, 2 mm β-mercaptoethanol, 0.02% Triton X-100, 0.4 mg/ml lysozyme. DNA was digested upon addition of 10 mm MgCl2 and 20 μg/ml DNase I. Clarified lysate was applied to a 30-ml Mono Q column equilibrated in Buffer A (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, 0.1 mm TCEP) plus 200 mm NaCl. Bound proteins were washed with the same buffer and then eluted with 500 mm NaCl in Buffer A. The PCNA-containing fractions were diluted to 150 mm NaCl, loaded onto a 6-ml Resource Q column, and eluted using a 40-column volume linear gradient from 200–500 mm NaCl in Buffer A. FLAG-PCNA eluted at ∼400 mm NaCl and was ∼95% pure by SDS-PAGE. Rad5ΔN (amino acids 500–1169) was a gift from Michael Eddins (Johns Hopkins Medical Institutes), RFC was a gift from Manju Hingorani (Wesleyan University), and Ub-GFP was available from a previous study. Doubly biotinylated template DNA and primer DNA were as described (31).

Synthesis and Purification of monoUb*-PCNA Conjugates

Synthesis followed the general strategy of Yin et al. (30). FLAG-PCNA (∼0.35 mm) and H6-Ub(G76C) (1 mm) were incubated on ice in 0.2 m sodium borate, pH 8.6, and 2 mm TCEP. 1,3-Dichloroacetone was added to 0.35 mm. After 1 h, the reaction was terminated by the addition of 5 mm β-mercaptoethanol. The coupling of FLAG-PCNA to H6-Ub(G76C) was 60–70% efficient and produced differentially modified PCNA trimers; these trimers were visualized by native gel electrophoresis (10% acrylamide). H6-Ub(G76C) and coupled H6-Ub(G76C) dimers were removed by gel filtration (Superdex 200; GE Healthcare) in 50 mm Tris, pH 8.0, 500 mm NaCl. The mixed monoUbn*-PCNA species (where n corresponds to the number of subunits in the trimer that are coupled to Ub) were loaded onto a 1-ml HisTrap FF column (GE Healthcare), and bound proteins were eluted with a 40-ml linear gradient of imidazole (5–200 mm). (H6-Ub(G76C))1PCNA eluted at ∼40 mm imidazole, (H6-Ub(G76C))2 PCNA eluted between 40 and 120 mm imidazole, and (H6-Ub(G76C))3 PCNA eluted after 100 mm imidazole.

Rad5 Binding Assays

1 nmol of FLAG-PCNA or FLAG-PCNA–(H6-Ub(G76))3 was immobilized on anti-FLAG M2 agarose and incubated with 1 nmol of H6-Rad5 for 1 h at 4 °C in 50 mm Tris, pH 7.6, 1 mm dithiothreitol, 100 mm NaCl. The resin was collected and washed twice in the same buffer, and bound proteins were eluted by incubation with 0.2 mg/ml FLAG peptide. The proteins were resolved using SDS-PAGE and detected by a Western blot using anti-FLAG or anti-polyhistidine antibody.

ATPase Assays

The reactions contained 25 mm Tris acetate, pH 7.6, 5% (v/v) glycerol, 1 mm dithiothreitol, 10 mm Mg(OAc)2, 25 μm [α-32P]ATP, 0.05 μm E1, and 0.1 μm Ubc13-Mms2 complex with or without 0.05 μm Rad5. The reactions were initiated by the addition of ATP, and after incubation at 30 °C, the products were resolved by thin layer chromatography (polyethyleneimine cellulose F; Merck) developed with 0.5 mm LiCl in 0.5 m formic acid and detected with a PhosphorImager.

Ubc13∼Ub Thiolester Assays

E2 thiolester assays were conducted as described (28) with 8 μm Ubc13-Mms2, 20 μm 125I-Ub(K63R), and 0.1 μm E1 with or without 2 μm Rad5. Nonreducing SDS-PAGE loading buffer was added to terminate the reactions. After SDS-PAGE, the Ub-thiolester adduct was detected by autoradiography and quantified by γ-counting. Reactions in which Ubc13 was precharged with 125I-Ub(K63R) were done similarly except that, after charging, E1 activity was stopped by the addition of 1 unit of apyrase (Sigma) to deplete ATP (25); Rad5 was then added, and the 125I-labeled thiolester products were measured as described above.

Free Chain Assembly and polyUb Chain Extension Assays

All of the conjugation reactions were at 37 °C and pH 7.6. In qualitative chain assembly assays, equal concentrations (117 μm) of acceptor Ub (Ub-D77) and donor Ub (Ub(K63R)) were used; by this means, conjugation was terminated at diubiquitin (Ub2). The reactions also contained 0.1 μm H6-E1, 2 μm Ubc13-Mms2, and 2 μm Rad5 (wild-type or I916A mutant). The Ub2 product was visualized by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie staining. polyUb synthesis assays were done similarly but used 234 μm Ub. In chain extension assays, 20 μm H6-PCNA (wild-type) or monoUb3*-PCNA and 117 μm Ub(K63R) were incubated under similar conditions. To determine the stoichiometry of the functional (Ubc13-Mms2)-Rad5 complex, increasing amounts of Rad5 were added to 0.4 μm Ubc13-Mms2 and incubated for 5 min. To quantify Ub2 production, 125I-Ub(K63R) was used. Ub2 was resolved using SDS-PAGE, and after staining with Coomassie Blue the 125I-Ub2 bands were excised and counted in a γ-counter (13).

Unless indicated otherwise, kinetic assays were conducted similarly using 2 μm Ubc13-Mms2 with or without 2 μm Rad5. The reactions were monitored to determine the initial rates of Ub conjugation at various Ub-D77 or monoUb3*-PCNA concentrations. The measurements were done in triplicate.

Ubiquitination of DNA-loaded PCNA

Loading assays were conducted as published (31), except that monoUb3*-PCNA was loaded onto the biotinylated DNA. Ubiquitination reactions were as described above.

RESULTS

Rad5 Accelerates Unanchored Lys63-linked polyUb Synthesis by Ubc13-Mms2

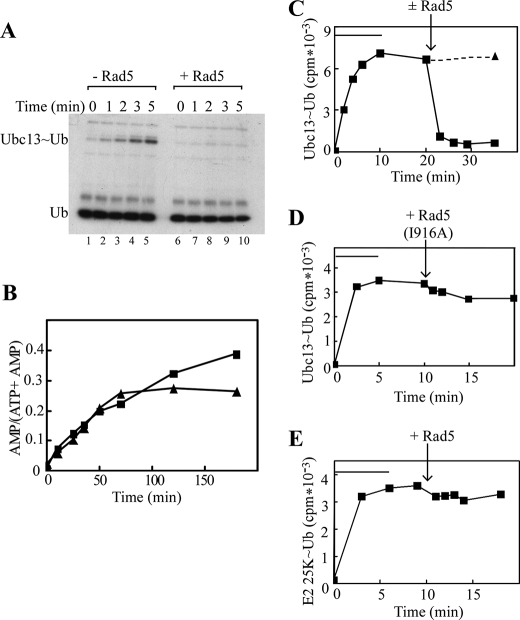

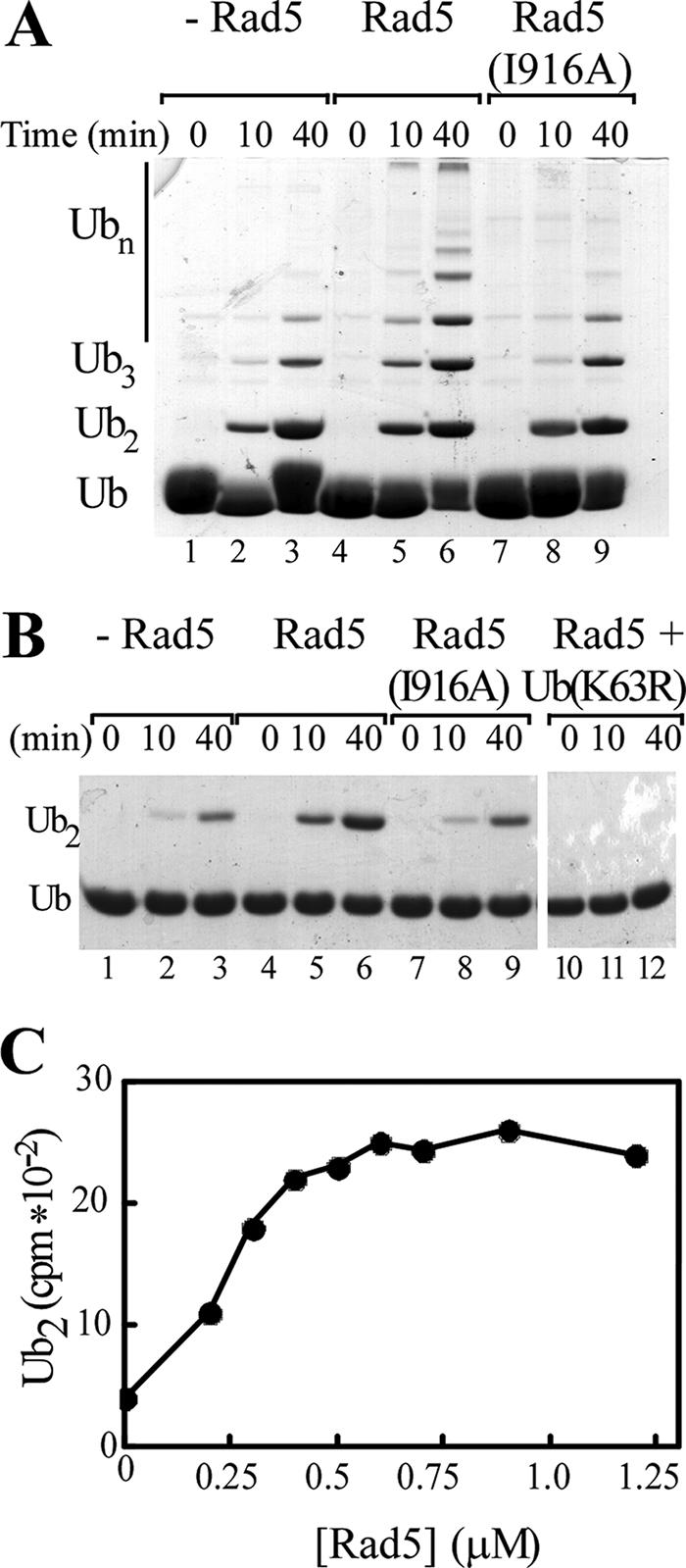

RING E3 ligases, such as Rad5, are generally thought to support ubiquitination by bringing together a Ub-charged E2, and the substrate. Ubc13-Mms2 can synthesize free polyUb chains in vitro, so we could examine the effects of Rad5 on free chain synthesis to see whether this E3 contributes to Ub conjugation in the absence of the monoUb-PCNA substrate. The addition of Rad5 to free chain assembly assays stimulated the rate of chain synthesis by Ubc13-Mms2 (Fig. 1A, lanes 1–3 versus lanes 4–6). This effect depended on the Rad5 RING domain, because there was no stimulation with a mutated form of Rad5, Rad5(I916A), in which the RING domain binding site for Ubc13-Mms2 was disrupted (lanes 7–9). It was previously shown that mutation of Ile916, which is conserved among many RING E3s, abrogates E2 binding, thereby inactivating the ligase function (20).

FIGURE 1.

Rad5 accelerates unanchored Lys63-linked polyUb synthesis by Ubc13-Mms2. A, standard free chain conjugation reactions were performed in the presence of Ubc13-Mms2, E1, wild-type Ub, and either no Rad5 (lanes 1–3), wild-type Rad5 (lanes 4–6), or Rad5(I916A) (lanes 7–9). Reaction products were resolved by SDS-PAGE and visualized with Coomassie Blue. B, reactions were as in A but used Ub(K63R) and Ub-D77 (lanes 1–9). The reactions containing wild-type Rad5 were also done with Ub(K63R) as the sole Ub source (lanes 10–12). C, conjugation assays employed Ubc13-Mms2, E1, Ub-D77, 125I-labeled Ub(K63R), and increasing amounts of Rad5. Following SDS-PAGE and autoradiography, 125I-Ub2 products were quantified and are plotted with respect to Rad5 concentration.

To facilitate more quantitative analysis, we limited chain assembly to diubiquitin formation by use of Ub-D77, which can serve only as a Ub acceptor, and Ub(K63R), which can serve only as a Ub donor. As in reactions containing wild-type Ub, Rad5 stimulated the formation of Ub2 by Ubc13-Mms2 (Fig. 1B, lanes 1–3 versus lanes 4–6). No stimulation was observed with Rad5(I916A), again indicating that stimulation depends on the RING domain (lanes 7–9). polyUb chains were not formed when reactions contained only Ub(K63R), confirming that chains were linked specifically through Lys63 (lanes 10–12).

To estimate the stoichiometry of the active complex, Rad5 was titrated into Ub2 synthesis reactions that contained a fixed concentration of Ubc13-Mms2 complex (0.4 μm). Maximal stimulation occurred when Rad5 was approximately equimolar with Ubc13-Mms2, indicating that the functional enzyme complex is a heterotrimer consisting of one Rad5 molecule and one Ubc13-Mms2 heterodimer (Fig. 1C).

Rad5 interacts with the E3 ligase Rad18, which is initially required to monoubiquitinate PCNA. The significance of this E3-E3 interaction has not been explored. Whereas other interacting E3s have been shown to cooperate in the catalysis of ubiquitination (e.g. BRCA1 and BARD1) (32, 33), we found that the addition of Rad6-Rad18 did not affect free chain synthesis by Ubc13-Mms2 in either the presence or the absence of Rad5 (supplemental Fig. S1). This may not be surprising because, unlike the BRCA1 and BARD1 E3 ligases, Rad18 and Rad5 do not interact through their RING domains.

Rad5 Destabilizes the Ubc13∼Ub Thiolester

We hypothesized two ways in which Rad5 could stimulate polyUb assembly by Ubc13-Mms2. Rad5 could stimulate the E1-catalyzed transthiolation that produces the Ubc13∼Ub thiolester, possibly by enhancing E1 interaction with Ubc13. Rad5 also could act after this step to promote the catalytic attack by Lys63 of the acceptor Ub on the thiolester bond of the donor Ub in Ubc13∼Ub. These two scenarios are not mutually exclusive.

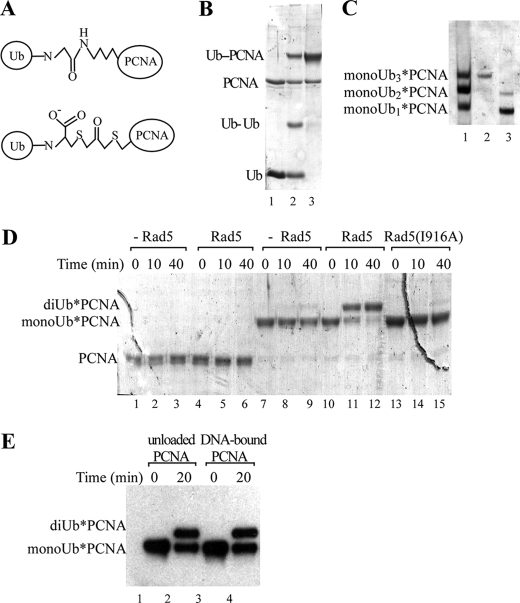

To examine whether Rad5 affects the E1-catalyzed charging of Ubc13 with Ub, we measured the rate of Ubc13∼Ub formation and its dependence on the presence of Rad5. The E1 enzyme catalyzed the formation of a Ubc13∼Ub thiolester between Ub(K63R) and the active site cysteine of Ubc13 (Fig. 2A, lanes 1–5). Remarkably, in the presence of Rad5, the formation of the Ubc13∼Ub thiolester could no longer be detected (Fig. 2A, lanes 6–10). We repeated this reaction in the absence of Mms2, with a similar outcome (data not shown).

FIGURE 2.

Rad5 destabilizes the Ubc13∼Ub thiolester. A, under nonreducing conditions, Ubc13-Mms2, E1, and 125I-labeled Ub(K63R) were incubated in the absence (lanes 1–5) or presence (lanes 5–10) of Rad5 for the indicated times. The reactions were terminated in nonreducing SDS-loading buffer, and the Ubc13∼Ub thiolester intermediates were visualized by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. B, the E1-catalyzed production of 32P-labeled AMP from [α-32P]ATP was measured in the absence (triangles) or presence (squares) of Rad5. C, Ubc13∼Ub thiolesters were formed over 5–10 min (bars) as in A. ATP was then depleted by the addition of apyrase, and incubations were continued in the presence (squares, solid line) or absence (triangle, dotted line) of Rad5. Ubc13∼Ub thiolesters were quantified following SDS-PAGE and γ-counting of excised bands. D, reactions were as in C, except that Rad5(I916A) was added upon depletion of ATP. E, reactions were as in C but contained the E2 conjugating enzyme E2–25K instead of Ubc13.

Although these results seemed to indicate that Rad5 inhibits transthiolation of Ub from E1 to E2, this was highly unlikely because, as shown in Fig. 1, Rad5 stimulated ubiquitination. Furthermore, assays to monitor the accumulation of the AMP byproduct of the E1-catalyzed Ub activation revealed that E1 activity was not affected by Rad5 (Fig. 2B). The initial rates of AMP production, as well as ATP consumption (data not shown), were similar in the presence and absence of Rad5. Note that under these conditions Rad5 single-strand DNA-dependent ATPase activity (18) was negligible, because the ADP product of this reaction did not accumulate (data not shown). In the absence of Rad5, AMP production plateaued as the limiting amounts of free Ubc13 were converted to Ubc13∼Ub. Inhibition did not occur in the presence of Rad5, suggesting that Rad5 may stimulate the turnover of Ubc13∼Ub. To investigate whether Rad5 affects that reactivity of the Ubc13∼Ub thiolester bond, we preformed complexes and evaluated their stabilities in the presence and absence of Rad5. Following depletion of ATP, Ubc13∼Ub intermediates were stable for >30 min in the absence of Rad5 (Fig. 2C, dotted line). Ubc13∼Ub intermediates were rapidly hydrolyzed upon the addition of Rad5, indicating that Rad5 increases reactivity of the thiolester bond (Fig. 2C, solid line).

The ability of Rad5 to affect the thiolester bond stability relied upon binding to Ubc13. Thiolester destabilization was lost when Ubc13 binding was abrogated by the I196A mutation in the Rad5 RING domain (Fig. 2D). Similarly, when presented with a noncognate E2∼Ub thiolester intermediate containing E2–25K, Rad5 did not effect thiolester hydrolysis (Fig. 2E). These results are in accord with reports in which UbcH5b or Cdc34 thiolester intermediates were destabilized by their cognate RING E3s (25, 26).

Rad5-induced Stimulation Does Not Rely on Repositioning of the Conserved Ubc13 Residue, Asn79

Wu et al. (28) have suggested that a conserved E2 asparagine residue (Asn79 in Ubc13) facilitates ubiquitination by stabilizing the charged intermediate formed when the lysine attacks the thiolester bond. Because crystal structures do not show this asparagine in a catalytically competent position, it was hypothesized that transient repositioning of this residue upon E2 binding to the E3 or Ub could be required to promote ubiquitination (15, 16, 21).

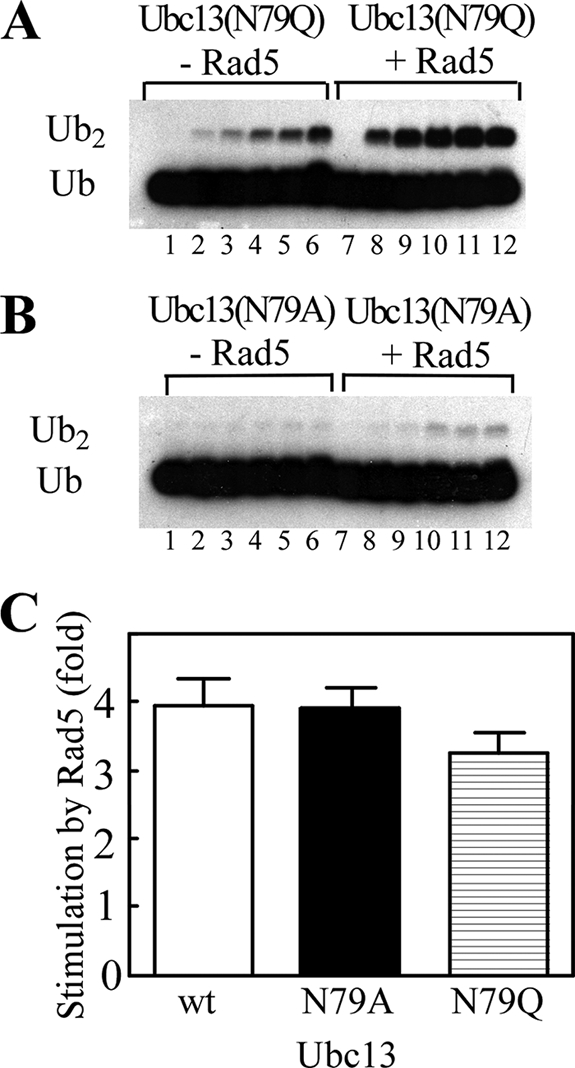

We hypothesized that if Rad5-stimulated chain synthesis by Ubc13-Mms2 occurred through repositioning of Asn79, mutating this residue to an glutamine or alanine would prevent stimulation upon addition of Rad5. Free chain assembly by Ubc13(N79Q)-Mms2 and Ubc13(N79A)-Mms2 was reduced to 5–10 and 2.5%, respectively, of the wild-type enzyme rate (28). Despite these defects, Rad5 enhanced the rate of chain synthesis by the mutant E2 heterodimers by ∼4-fold, similar to that observed with wild-type Ubc13-Mms2 (Fig. 3). Thus, repositioning of Asn79 is not critical for Rad5-induced stimulation of free chain synthesis.

FIGURE 3.

Rad5 stimulation of ubiquitination does not rely on repositioning of the conserved E2 residue, Ubc13 Asn79. A, free chain synthesis reactions were performed in the presence of E1, Ubc13(N79Q)-Mms2, 125I-labeled Ub(K63R), and Ub-D77 either in the absence (lanes 1–6) or presence (lanes 7–12) of Rad5. The reactions were terminated at 0, 0.5, 1, 2, 3, and 4 h. The products were resolved by SDS-PAGE and visualized by autoradiography. B, reactions were as in A, except that Ubc13(N79A) was used. C, comparison of free polyUb chain synthesis in reactions with or without Rad5 and wild-type (wt) or mutant Ubc13. Each bar represents the ratio of the rates of Ub2 formation in the presence versus the absence of Rad5. The error bars indicate ± S.E.

Rad5 Stimulates the Extension of a Ub Signal on PCNA

Deletion of Rad5 in yeast leads to sensitivity to DNA-damaging agents because PCNA polyubiquitination and consequently DDT are impaired. Therefore, we wanted to investigate the abilities of Ubc13-Mms2 and (Ubc13-Mms2)-Rad5 to extend a polyUb chain on monoUb-PCNA. Because large scale synthesis of monoUb-PCNA by Rad6-Rad18 is not yet feasible, we adapted a chemical cross-linking strategy (30). A FLAG-tagged PCNA variant mutated to eliminate four endogenous cysteines and include a K164C substitution was coupled to the C-terminal cysteine in H6-Ub(G76C) using dichloroacetone, a bifunctional alkylating agent. The resulting nonhydrolyzable linker between Ub and PCNA is similar in size to an isopeptide bond (Fig. 4A). We obtained ∼60% conversion of FLAG-PCNA to FLAG-PCNA-H6-Ub (Fig. 4B).

FIGURE 4.

Rad5 catalyzes the extension of a Ub signal on PCNA. A, diagram comparing the isopeptide linkage of monoUb-PCNA (top panel) and the chemically synthesized analog, monoUb*-PCNA (bottom panel) (adopted from Ref. 30). B, FLAG-PCNA and H6-Ub(G76C) (lane 1) were coupled using dichloroacetone (lane 2) to produce monoUb*-PCNA. Unreacted H6-Ub and cross-linked H6-Ub dimers were removed by gel filtration (lane 3). C, monoUbn*-PCNA reaction products (n = 0–3) were separated using native gel electrophoresis (lane 1) and visualized with Coomassie Blue. The mixture of products was separated by nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid chromatography to yield monoUb3*-PCNA (lane 2) and monoUb1–2*-PCNA (lane 3). D, PCNA (lanes 1–6) or monoUb3*-PCNA (lanes 7–15) were incubated in conjugation reactions containing E1, Ubc13-Mms2, and Ub(K63R), with or without Rad5, as indicated. The products were separated by SDS-PAGE and visualized with Coomassie Blue. E, reactions were as in D, except that monoUb3*-PCNA was first loaded onto DNA by RFC (lanes 3 and 4), and the PCNA species were detected by immunoblotting with anti-FLAG antibodies.

Native PCNA is a stable homotrimer. Because the coupling reaction was incomplete, the reaction produced a mixture of PCNA trimers containing zero, one, two, and three H6-Ub moieties; these products could be resolved by native PAGE (Fig. 4C). Size exclusion and nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid affinity chromatographies were used to isolate the different PCNA species (Fig. 4C, lanes 2 and 3). These modified trimers were stable, and exchange of subunits among the trimers did not occur at a significant rate (supplemental Fig. S2). For simplicity, unless otherwise noted, we refer to the substrate analog polypeptide as monoUb*-PCNA and the trimers as monoUbn*-PCNA, where n indicates the number of modified PCNA subunits.

As genetic studies have suggested (3, 4), neither Ubc13-Mms2 nor (Ubc13-Mms2)-Rad5 could assemble a polyUb chain on PCNA de novo (Fig. 4D, lanes 1–6). However, Ubc13-Mms2 recognized monoUb3*-PCNA and catalyzed its conjugation to Ub(K63R) (Fig. 4D). The addition of Rad5 greatly stimulated this reaction (Fig. 4D, lanes 7–9 versus lanes 10–12). When wild-type Ub was used, ubiquitination of monoUb3*-PCNA resulted in the formation of long polyUb conjugates (supplemental Fig. S3).

Unlike PCNA for monoubiquitination by Rad6-Rad18 (7, 31), monoUb3*-PCNA did not need to be loaded onto DNA to serve as a substrate for ubiquitination by (Ubc13-Mms2)-Rad5. Moreover, neither loading monoUb3*-PCNA onto DNA nor addition of the Rad6-Rad18 complex affected the rate of polyubiquitination by (Ubc13-Mms2)-Rad5 (Fig. 4E and supplemental Figs. S4 and S5).

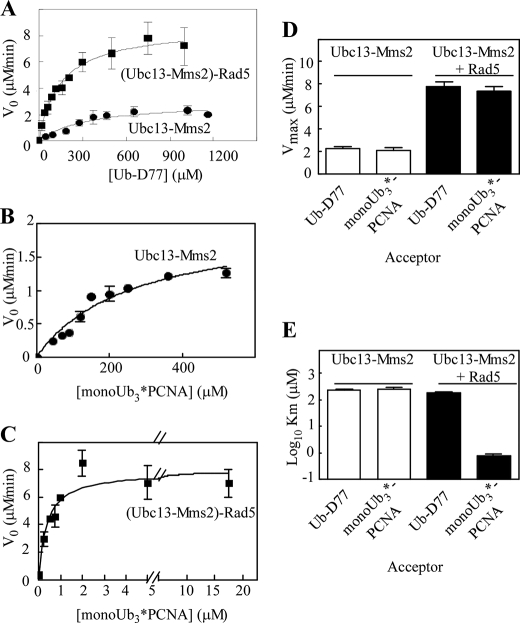

Rad5 Affects the Vmax of Free polyUb Chain Synthesis and Both Vmax and Km of monoUb3*-PCNA Polyubiquitination

To compare the effect of Rad5 on free chain assembly with polyUb chain extension on monoUb3*-PCNA, steady state kinetic assays were conducted. Ubc13-Mms2 was combined with donor Ub(K63R) and increasing concentrations of an acceptor (either Ub-D77 or monoUb3*-PCNA) with or without Rad5 (Fig. 5, A–C, and Table 1). With Ubc13-Mms2 alone, similar Km (212 versus 248 μm) and Vmax (2.3 versus 1.8 μm/min) values were obtained for reactions containing either Ub-D77 or monoUb3*-PCNA acceptors. The addition of Rad5 increased Vmax ∼4-fold for both free chain assembly and ubiquitination of monoUb3*-PCNA (7.7 and 7.3 μm/min, respectively) (Fig. 5D). However, the binding of Rad5 to the two acceptors was markedly different, as revealed by the Km values. Whereas only a modest decrease in acceptor substrate Km was observed upon the addition of Rad5 in free chain assembly (212 μm without Rad5 versus 141 μm with Rad5), the Km decreased significantly with Rad5 when monoUb3*-PCNA was the acceptor (248 μm without Rad5 versus ∼1 μm with Rad5) (Fig. 5E and Table 1). Like other E3s, Rad5 functions to recruit substrates for conjugation by its cognate E2.

FIGURE 5.

Rad5 affects the Vmax for free polyUb chain synthesis but both Vmax and Km for monoUb3*-PCNA modification. A, standard polyUb chain synthesis reactions contained E1, Ubc13-Mms2, 125I-Ub(K63R), and increasing amounts of Ub-D77, with or without Rad5. The products were separated by SDS-PAGE, and 125I-Ub2 was quantified by γ-counting. The initial velocities as a function of [Ub-D77] are shown. The rates were measured in triplicate and fit by the Michaelis-Menten equation. B and C, reactions were performed as in A, but with monoUb3*-PCNA as the acceptor substrate. D and E, comparisons of Vmax and Km values for ubiquitination of Ub-D77 and monoUb3*-PCNA with or without Rad5. To obtain an accurate Km value, the (Ubc13-Mms2)-Rad5 concentration was lowered to 0.05 μm. The error bars represent ± S.E.

TABLE 1.

Kinetic constants for ubiquitination by the Ubcl3-Mms2 and (Ubcl3-Mms2)-Rad5 complexes

| Reaction catalyzed | Km | kcata |

|---|---|---|

| μm | min−1 | |

| Ubcl3-Mms2 | ||

| Free chain synthesis | 212 ± 26 | 1.1 ± 0.1 |

| monoUb3*-PCNA chain extension | 248 ± 57 | 0.9 ± 0.3 |

| (Ubcl3-Mms2)-Rad5 | ||

| Free chain synthesis | 141 ± 29 | 3.8 ± 0.4 |

| monoUb3*-PCNA chain extension | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 3.5 ± 0.03 |

| monoUb1*-PCNA chain extension | 0.9 ± 0.3 | 3.0 ± 0.04 |

kcat = Vmax/[Etotal].

We were unable to measure accurately the Km of (Ubc13-Mms2)-Rad5 for monoUb3*-PCNA under the conditions used in Fig. 5C. Therefore, the enzyme concentration was lowered to maintain the steady state condition of approximately constant free substrate. Under this condition, the Km was determined to be 0.9 μm (Table 1).

To promote error-free DDT, (Ubc13-Mms2)-Rad5 must be specifically recruited to stalled replication forks. Whether efficient recognition of these stalled replication forks by the (Ubc13-Mms2)-Rad5 complex requires monoubiquitination of multiple subunits within the PCNA trimer or whether monoubiquitination of a single subunit functions equally well has not been resolved. We therefore compared the fully modified monoUb3*-PCNA with monoUb1*-PCNA as acceptors for Rad5-catalyzed ubiquitination. The concentrations of PCNA species used in these assays were adjusted to provide equal amounts of monoUb*-PCNA subunits. When normalized in this way, no differences in either the Km or Vmax for Rad5-mediated ubiquitination of these two substrates were observed (Table 1), suggesting that monoubiquitination of a single subunit of the PCNA trimer suffices for polyubiquitination by the (Ubc13-Mms2)-Rad5 complex.

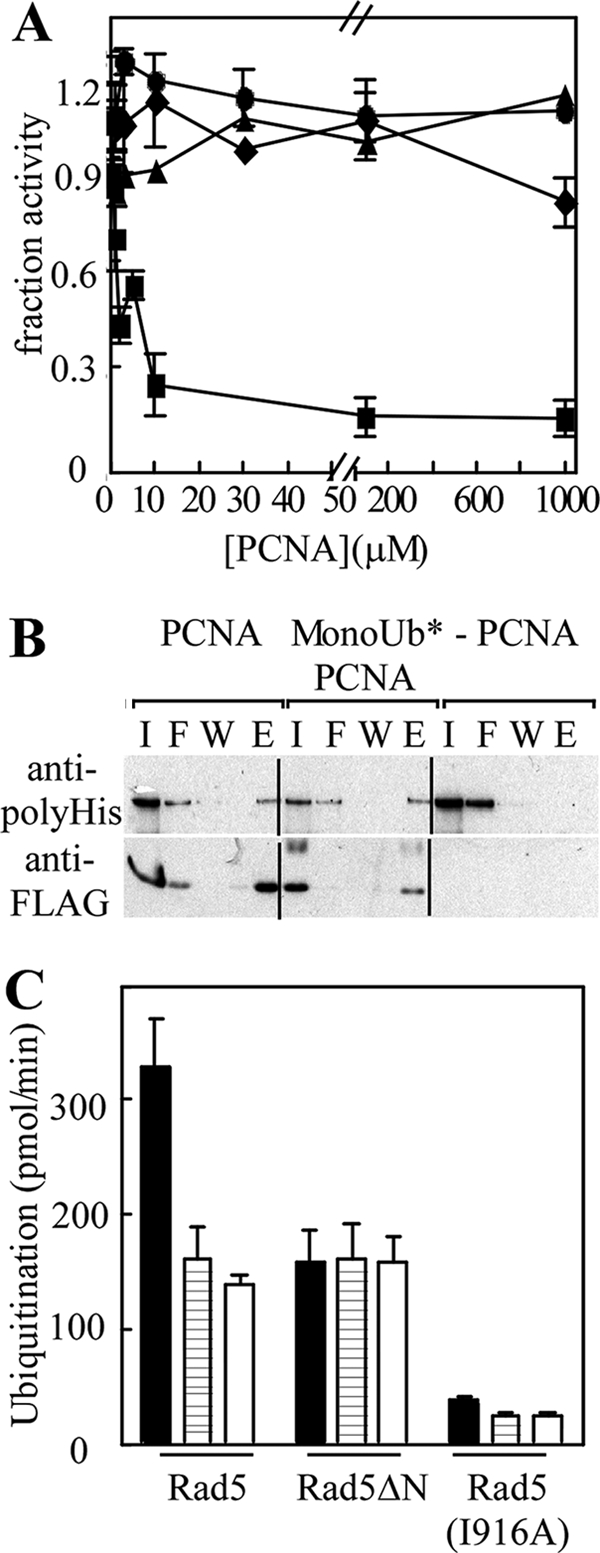

The N Terminus of Rad5 Imparts Affinity for PCNA

In vivo, levels of monoUb-PCNA are likely to be very low relative to the level of unmodified PCNA. We therefore investigated the effect of unmodified PCNA on (Ubc13-Mms2)-Rad5-catalyzed polyUb chain extension on monoUb3*-PCNA as well as on free chain synthesis. Unmodified PCNA strongly inhibited Rad5-stimulated ubiquitination of monoUb3*-PCNA but had no effect on the stimulation of free chain synthesis (Fig. 6A). This indicates that PCNA binding to Rad5 neither alters nor occludes the acceptor-Ub binding site on Mms2. Free PCNA did not effect the reactions catalyzed by Ubc13-Mms2 alone, confirming that Rad5 is primarily responsible for interactions with the PCNA moiety of monoUb-PCNA.

FIGURE 6.

Rad5 interacts with PCNA. A, standard polyUb chain synthesis or monoUb3*-PCNA modification reactions were performed with increasing concentrations of unmodified PCNA. The assays contained E1, (Ubc13-Mms2), 125I-Ub(K63R), and either monoUb3*-PCNA (diamonds), monoUb3*PCNA acceptor plus Rad5 (squares), Ub-D77 (triangles), or Ub-D77 plus Rad5 (circles). The error bars represent ± S.E. from three experiments. B, FLAG-PCNA (lanes 1–4) or monoUb3*-FLAG-PCNA (lanes 5–8) was immobilized on anti-FLAG beads and incubated with H6-Rad5. Input (I), flow-through (F), wash (W), and FLAG peptide-eluted proteins (E) were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-FLAG or anti-polyhistidine antibodies. Anti-FLAG antibody beads without bound PCNA were included as a control (lanes 9–12). C, rates of ubiquitination of monoUb3*-PCNA (solid bars), Ub-GFP (striped bars), and Ub-D77 (open bars) were determined in standard reactions containing E1, Ubc13-Mms2, 125Ι-Ub(K63R), and either wild-type Rad5, Rad5ΔN, or Rad5 (I916A). The products were resolved by SDS-PAGE and counted in a γ-counter. Each reaction was done in triplicate; the error bars represent ± S.E.

The inhibition of Rad5-stimulated ubiquitination of monoUb3*-PCNA described above suggested that Rad5 binds to both modified and unmodified PCNA. To test this directly, FLAG-tagged PCNA and monoUb3*-PCNA were immobilized on anti-FLAG beads. As predicted, Rad5 interacted similarly in pull-down assays with modified and unmodified PCNA (Fig. 6B).

Consistent with the above results, Rad5 has been shown previously to interact with PCNA (3, 39). Because the helicase domain of Rad5 is not thought to bind to PCNA (41), we hypothesized that the N terminus of Rad5 is responsible for binding PCNA. We therefore compared the abilities of Rad5 and a Rad5 N-terminal deletion mutant (Rad5ΔN, residues 500–1169) to stimulate Ubc13-Mms2-mediated ubiquitination of monoUb3*-PCNA (Fig. 6C). Ubiquitination of a Ub-GFP fusion protein and Ub-D77 were analyzed as controls. Whereas Rad5ΔN stimulated ubiquitination of all three substrates to a similar degree, full-length Rad5 increased Ub(K63R) conjugation to monoUb3*-PCNA much more than to Ub-GFP and Ub(D77). The Rad5(I916A) RING mutant had similar slow ubiquitination rates with all three substrates, as expected. The differences exhibited by Rad5 and Rad5ΔN are consistent with the N terminus of Rad5 mediating binding to monoUb-PCNA.

DISCUSSION

Our characterization of the in vitro activity of the (Ubc13-Mms2)-Rad5 complex has shown that the Rad5 E3 ligase acts in two ways to facilitate polyUb synthesis by the Ubc13-Mms2 E2 heterodimer. First, through analysis of free polyUb chain synthesis, we found that Rad5 enhances the reactivity of the thiolester bond of Ubc13∼Ub intermediates. Second, through our use of stable analogs of monoUbn-PCNA, we found that Rad5 also binds directly to PCNA. Thus, Rad5 coordinates polyubiquitination of PCNA by activating the Ub-Ubc13 thiolester in close proximity to the bound substrate.

That Rad5 stimulated free chain synthesis by Ubc13-Mms2 indicates that the role of Rad5 in the polyubiquitination of monoUb-PCNA is not simply to bring the substrate together with Ub∼Ubc13-Mms2. Mutation of Rad5 Ile916, a key residue in the RING domain that is required for Ubc13 binding (20), eliminated the stimulation of free chain synthesis, which showed that the effect was mediated through Rad5 interaction with Ubc13.

Rad5 Enhances Ubc13∼Ub Reactivity

ATPase assays confirmed that the stimulation by Rad5 is not due to an effect on the E1-catalyzed Ub charging of Ubc13. This was not unexpected, because competition assays and crystal structures of the UbcH5a E2 conjugating enzyme in a complex with either the E1 enzyme or an E3 ligase (SCFβ-TRCP) revealed that overlapping binding sites on the E2 prevent simultaneous binding of the E1 and E3 (21, 35). Rather, we found that Rad5 stimulated the release of Ub from the Ub∼Ubc13 intermediate. Neither Ub∼Ubc13 thiolester formation nor subsequent Ub release upon the addition of Rad5 depended on the presence of Mms2. Accordingly, the effect of Rad5 on the stability of the E2∼Ub thiolester intermediate depends on direct interactions with Ubc13.

Like Rad5, the SCFβ-TRCP RING E3 ligase affects the stability of the Ub thiolester formed on its cognate E2, UbcH5b (25). This particular E2-E3 pair catalyzes the formation of Lys48-linked chains rather than Lys63-linked chains. Collectively, these findings suggest that activation of the E2∼Ub thiolester for nucleophilic attack may be a general mechanism whereby RING E3 ligases stimulate ubiquitination. A detailed picture of the molecular basis for this effect awaits future structural studies.

Previous work indicated that a conserved E2 asparagine residue (Asn79 in Ubc13) may play an important role in catalyzing ubiquitination by stabilizing the oxyanion reaction intermediate (28). However, structural studies show that this Asn may be positioned unfavorably to serve such a role (15, 16, 21). We examined whether Rad5 might stimulate Ub release from charged Ubc13 by repositioning Asn79 closer to the thiolester bond. Consistent with previous findings (28), mutating Asn79 caused severe defects in free chain synthesis by Ubc13-Mms2. Nonetheless, we observed a consistent 4-fold stimulation by Rad5 of the rate of free chain assembly by these mutants. Thus, the role of Rad5 in the activation of the Ubc13∼Ub thiolester is not to reposition Asn79.

Rad5 Binding to PCNA Promotes Substrate Interaction with Ubc13-Mms2

To examine further how Rad5 stimulates free chain assembly, we compared the kinetics of chain synthesis by Ubc13-Mms2 alone and with Rad5. These experiments revealed that Rad5 had only a modest effect on the Km for the acceptor Ub-D77 during free chain assembly, which in either case was >10-fold greater than the estimated 10–20 μm concentration of free Ub in the cell (34). This high Km would help to mitigate against nonproductive free chain assembly in vivo. In contrast to its effects on Km, Rad5 increased the Vmax 4-fold, which is likely due to increased reactivity of the Ubc13∼Ub thiolester bond.

Rad5 functions to promote genome integrity primarily by facilitating PCNA polyubiquitination to promote DDT. Many questions remain regarding recognition of the monoUb-PCNA trimer and polyUb chain extension by (Ubc13-Mms2)-Rad5. In vivo, DNA damage-induced synthesis of monoUb-PCNA is catalyzed by the E2-E3 pair, Rad6-Rad18. Recognition of PCNA by Rad18 requires that PCNA is loaded onto DNA by RFC, the five-subunit clamp loading complex (7, 31, 36). In reports of this reaction, high enzyme concentrations and long incubation times were required to produce fully modified monoUb-PCNA in vitro (7, 31). To circumvent this constraint, we adapted a chemical coupling approach (30) that enabled us to produce monoUbn*-PCNA analogs that mimic the native isopeptide-linked conjugate (Fig. 4A). Modeling and in vivo studies indicate that monoUb-PCNA has a flexible conformation, suggesting that this analog would behave similarly to the native form. For example, a C-terminal Ub-PCNA fusion protein can recruit downstream factors to sites of DNA damage to promote DDT (37).

Ubc13-Mms2 and (Ubc13-Mms2)-Rad5 each were able to polyubiquitinate monoUbn*-PCNA. The rates were similar when monoUb*-PCNA was free or loaded onto DNA or when reactions included Rad6-Rad18. These observations allowed us to compare the ubiquitination of monoUb*-PCNA species by Ubc13-Mms2 and Rad5. There was no difference in the ability of Ubc13-Mms2 alone to bind or ubiquitinate a Ub on monoUb3*-PCNA or, as a control, Ub-D77. This suggests that the only portion of monoUb3*-PCNA recognized by Ubc13-Mms2 is the Ub moiety. Consistently, free PCNA had no effect on Ubc13-Mms2-mediated ubiquitination of monoUb3*-PCNA.

In contrast, when assays were performed in the presence of Rad5, significantly different Km values where observed, depending on the acceptor. (Ubc13-Mms2)-Rad5 recognized monoUb3*-PCNA much more effectively than Ub-D77, as indicated by a >100-fold reduction in the Km. In addition, excess free PCNA reduced Rad5-stimulated ubiquitination of monoUb3*-PCNA, which confirmed that Rad5 interacts directly with the PCNA moiety. Rad5 interacted with either fully or partially modified monoUb*-PCNA. Likewise, the Rad5-induced stimulation (or increased Vmax) of ubiquitination was similarly ∼4-fold for both free polyUb chain synthesis and ubiquitination of the monoUb3*-PCNA acceptor.

How the (Ubc13-Mms2)-Rad5 complex is recruited to stalled DNA replication forks in vivo is unclear. Our pull-down experiments suggest that Rad5 interacts well with both monoUb3*-PCNA and unmodified PCNA (Fig. 6B). We also found that unmodified PCNA inhibited ubiquitination of monoUb3*-PCNA by (Ubc13-Mms2)-Rad5. Therefore, specific recognition by (Ubc13-Mms2)-Rad5 of PCNA complexes within a stalled DNA replication fork is likely to require other components. Hallmarks of a stalled replication fork include DNA damage at a forked DNA structure as well as the concomitant accumulation of single-stranded DNA. Notably, Rad5 contains N-terminal regions that bind to single-stranded DNA (18, 38). This DNA binding activity may help to recruit Rad5 to stalled replication forks, and Rad5 has been shown to exhibit preference for forked DNA (11). However, we found that unmodified PCNA inhibited polyubiquitination of PCNA by (Ubc13-Mms2)-Rad5 even when the monoUb3*-PCNA acceptor was loaded onto DNA containing a single-strand–duplex DNA junction. In addition, Rad5 interacts with Rad18, the E3 ligase responsible for monoubiquitinating PCNA (40). Rad18 is recruited to stalled replication forks by interactions with PCNA, DNA, and RPA, the single-stranded DNA binding complex. In vitro, however, Rad18 did not assist in free chain synthesis by Rad5 (supplemental Fig. S1, B and C), but it remains possible that interactions between forked DNA, RPA, PCNA, and Rad18 could help to recruit Rad5 to the sites of stalled replication.

Based on our observations, we can propose how (Ubc13-Mms2)-Rad5 interacts with monoUb-PCNA to catalyze polyUb chain synthesis. In this minimal model, Mms2 interacts directly with the Ub moiety of monoUb-PCNA, whereas Rad5 interacts with PCNA. This scenario is supported by the 150-fold lower Km observed for the monoUb*1–3-PCNA acceptors relative to free Ub (Table 1). Our model predicts that Rad5 and Mms2 function together to bind monoUb-PCNA and position Lys63 of the acceptor Ub moiety near the active site thiolester bond of Ub∼Ubc13, thereby promoting transfer of a new Ub onto Ubn-PCNA. However, chain extension in vivo is likely to also involve interactions with forked DNA, Rad18, and other components of the DDT pathway to achieve specificity for the monoUb-PCNA substrate.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grant R01GM060372 (to C. M. P. and M. J. M.). This work was also supported by American Heart Association Predoctoral Grant 0715305U (to C. M. C.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental text and Figs. S1–S5.

- DDT

- DNA damage tolerance

- PCNA

- proliferating cell nuclear antigen

- Ub

- ubiquitin

- polyUb

- polyubiquitin

- monoUb

- monoubiquitin

- E1

- ubiquitin-activating enzyme

- E2

- ubiquitin carrier protein

- E3

- ubiquitin-protein isopeptide ligase

- H6

- His6

- TCEP

- tris(2-carboxy-ethyl)phosphine hydrochloride

- RFC

- replication protein C

- GFP

- green fluorescent protein.

REFERENCES

- 1.Moldovan G. L., Pfander B., Jentsch S. (2007) Cell 129, 665–679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Torres-Ramos C. A., Yoder B. L., Burgers P. M., Prakash S., Prakash L. (1996) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 9676–9681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoege C., Pfander B., Moldovan G. L., Pyrowolakis G., Jentsch S. (2002) Nature 419, 135–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haracska L., Torres-Ramos C. A., Johnson R. E., Prakash S., Prakash L. (2004) Mol. Cell Biol. 24, 4267–4274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pickart C. M., Eddins M. J. (2004) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1695, 55–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Torres-Ramos C. A., Prakash S., Prakash L. (2002) Mol. Cell Biol. 22, 2419–2426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garg P., Burgers P. M. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 18361–18366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guo C., Tang T. S., Bienko M., Parker J. L., Bielen A. B., Sonoda E., Takeda S., Ulrich H. D., Dikic I., Friedberg E. C. (2006) Mol. Cell Biol. 26, 8892–8900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Plosky B. S., Vidal A. E., Fernández de Henestrosa A. R., McLenigan M. P., McDonald J. P., Mead S., Woodgate R. (2006) EMBO J. 25, 2847–2855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gangavarapu V., Haracska L., Unk I., Johnson R. E., Prakash S., Prakash L. (2006) Mol. Cell Biol. 26, 7783–7790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blastyák A., Pintér L., Unk I., Prakash L., Prakash S., Haracska L. (2007) Mol. Cell 28, 167–175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hofmann R. M., Pickart C. M. (1999) Cell 96, 645–653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hofmann R. M., Pickart C. M. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 27936–27943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McKenna S., Spyracopoulos L., Moraes T., Pastushok L., Ptak C., Xiao W., Ellison M. J., Spyracopoulos L. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 40120–40126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.VanDemark A. P., Hofmann R. M., Tsui C., Pickart C. M., Wolberger C. (2001) Cell 105, 711–720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eddins M. J., Carlile C. M., Gomez K. M., Pickart C. M., Wolberger C. (2006) Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 13, 915–920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson R. E., Henderson S. T., Petes T. D., Prakash S., Bankmann M., Prakash L. (1992) Mol. Cell Biol. 12, 3807–3818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson R. E., Prakash S., Prakash L. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 28259–28262 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ardley H. C., Robinson P. A. (2005) Essays Biochem. 41, 15–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ulrich H. D., Jentsch S. (2000) EMBO J. 19, 3388–3397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zheng N., Wang P., Jeffrey P. D., Pavletich N. P. (2000) Cell 102, 533–539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scaglione K. M., Bansal P. K., Deffenbaugh A. E., Kiss A., Moore J. M., Korolev S., Cocklin R., Goebl M., Kitagawa K., Skowyra D. (2007) Mol. Cell Biol. 27, 5860–5870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang M., Pickart C. M. (2005) EMBO J. 24, 4324–4333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.You J., Pickart C. M. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 19871–19878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ozkan E., Yu H., Deisenhofer J. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 18890–18895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Petroski M. D., Deshaies R. J. (2005) Cell 123, 1107–1120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haldeman M. T., Xia G., Kasperek E. M., Pickart C. M. (1997) Biochemistry 36, 10526–10537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu P. Y., Hanlon M., Eddins M., Tsui C., Rogers R. S., Jensen J. P., Matunis M. J., Weissman A. M., Wolberger C., Pickart C. M. (2003) EMBO J. 22, 5241–5250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pickart C. M., Raasi S. (2005) Methods Enzymol. 399, 21–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yin L., Krantz B., Russell N. S., Deshpande S., Wilkinson K. D. (2000) Biochemistry 39, 10001–10010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haracska L., Unk I., Prakash L., Prakash S. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 6477–6482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brzovic P. S., Rajagopal P., Hoyt D. W., King M. C., Klevit R. E. (2001) Nat. Struct. Biol. 8, 833–837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hashizume R., Fukuda M., Maeda I., Nishikawa H., Oyake D., Yabuki Y., Ogata H., Ohta T. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 14537–14540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Haas A. L., Bright P. M. (1985) J. Biol. Chem. 260, 12464–12473 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eletr Z. M., Huang D. T., Duda D. M., Schulman B. A., Kuhlman B. (2005) Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 12, 933–934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tsurimoto T., Fairman M. P., Stillman B. (1989) Mol. Cell Biol. 9, 3839–3849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bienko M., Green C. M., Crosetto N., Rudolf F., Zapart G., Coull B., Kannouche P., Wider G., Peter M., Lehmann A. R., Hofmann K., Dikic I. (2005) Science 16, 1821–1824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Iyer L. M., Babu M. M., Aravind L. (2006) Cell Cycle 5, 775–782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen S., Davies A. A., Sagan D., Ulrich H. D. (2005) Nucleic Acids Res. 33, 5878–5886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ulrich H. D. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 7051–7058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Eisen J. A., Sweder K. S., Hanawalt P. C. (1995) Nucleic Acids Res. 23, 2715–2723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.