Abstract

Gram-negative bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS) activates macrophages by interacting with Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) and triggers the production of various pro-inflammatory Th1 type (type 1) cytokines such as IFNγ, TNFα, and IL8. Though some recent studies cited macrophages as potential sources for Th2 type (type 2) cytokines, little however is known about the intracellular events that lead to LPS-induced type 2 cytokines in macrophages. To understand the mechanisms by which LPS induces type 2 cytokine gene expression, macrophages were stimulated with LPS, and the expression of IL-4 and IL-5 genes were examined. LPS, acting through TLR4, activates both type 1 and type 2 cytokine production both in vitro and in vivo by using macrophages from C3H/HeJ or C3H/HeOuJ mice. Although the baseline level of both TNFα and IL-4 protein was very low, TNFα was released rapidly after stimulation (within 4 h); however, IL-4 was released after 48 h LPS stimulation in secreted form. Silencing of myeloid differentiation protein (MyD88) and TRIF-related adaptor molecule (TRAM), using small interfering RNA abolished IL-4 induction induced by LPS whereas silencing of TRAM has no effect on TNFα induction, thereby indicating that LPS-induced TNFα is MyD88-dependent but IL-4 is required both MyD88 and TRAM. These findings suggest a novel function of LPS and the signaling pathways in the induction of IL-4 gene expression.

Pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs)2 such as bacterial LPS are powerful activators of the innate immune system. Exposure to LPS induces an inflammatory reaction in the lung, mediated primarily by an array of inflammatory chemokines and cytokines released by blood monocytes and alveolar macrophages. Mammalian Toll-like receptors (TLRs) are key molecules for recognizing microbial PAMPs and transducing the subsequent inflammatory response (1). LPS is well known to interact with macrophages via TLR4 receptor resulting in cellular activation and synthesis and release of type 1 proinflammatory cytokines such as IFNγ, IL-2, and TNFα (2, 3). These cytokines can further activate monocytes, neutrophils, and lymphocytes, initiating cellular injury and tissue damage (4, 5).

Inhaled LPS signaling through TLR4 has also been shown to be necessary to induce type 2 responses to inhaled antigens in a mouse model of allergic asthma (6). IL-4, the prototypic type 2 cytokine, is a pleiotropic cytokine with regulatory effects on B cell growth, T cell growth, and function, immunoglobulin class switching to IgE during the development of immune responses (7). It is also involved in promoting cellular inflammation in the asthmatic lung and contributes to the pathogenesis of allergy and lung remodeling in chronic asthma (8, 9). Different cell types have been reported to produce IL-4 including the well known CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (10, 11), basophils (12), natural killer cells (13), mast cells (14), and eosinophils (15). Pouliot et al. (3) have shown that human alveolar macrophages (AMs) can produce IL-4 in response to PMA and calcium ionophore A23187, and they suggest that AMs might play a crucial role in the type 1/type 2 balance in the lung.

LPS-stimulated production of type 1 cytokines such as TNFα and INFγ has been extensively studied in macrophages; however, LPS-stimulated production of type 2 cytokines by macrophages has not yet been well defined. Because the presence of IL-4 at the site of a developing immune response can skew the ultimate cytokine pattern, alveolar macrophage produced IL-4 may be important in the development of allergic airway disease. Indeed, TLR4-defective mice studied using a standard murine model of allergic airway inflammation had an overall decrease in lung inflammatory responses, a dramatic reduction of eosinophils and lymphocytes, and lower circulating levels of OVA-specific IgE (16).

The intracellular events following LPS stimulation of TLR4 depends on different sets of Toll/interleukin-1 resistance (TIR) domain containing adaptor molecules. These adaptors provide a structural platform for the recruitment of downstream effector molecules (17, 18). Two distinct responses following engagement of TLR4 with LPS have been described. An early response leading to activation of NF-κB is dependent on MyD88, while a late response utilizes TIR domain-containing adaptor-inducing interferon-γ (TRIF) and TRIF-related adaptor molecule (TRAM) to activate NF-κB (19). While TRIF is common to both TLR3 and TLR4 pathways, TRAM is highly specific for TLR4 (20). The complex signaling network initiated by the interaction of the adaptor and effector proteins ultimately decides the specific pattern of gene expression that is elicited in response to TLR agonists and the particular type of cytokine that is produced determines the recruitment and activation of other immune cells. Therefore, further clarification of the cellular responses following the activation of TLR is crucial and fundamental to our understanding of immune responses.

In this report, we show that LPS can stimulate de novo IL-4 gene expression in murine macrophages, both in vitro and in vivo. Utilizing RNA interference we further showed that the induction of IL-4 is both MyD88- and TRAM-dependent (MyD88-independent), while LPS-induced TNFα is strictly dependent on MyD88. These results indicate that LPS induces IL-4 production by macrophages, and provide a new molecular mechanism controlling the regulation of IL-4 prior to the emergence of a polarized adaptive immune response.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Culture

The RAW264.7 murine macrophage cell line was from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) (Manassas, VA) and cultured in DMEM with GlutaMAX-1, HEPES (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) and penicillin-streptomycin. The MH-S murine alveolar macrophage cell line was a kind gift from Dr. R. G. Worth (University of Toledo, HSC, Toledo, OH). MH-S cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 with l-glutamine (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) sodium bicarbonate (1.5g/liter), glucose (4.5g/liter) HEPES (10 mm), sodium pyruvate (1 mm), 0.05 mm 2-mercaptoethanol, and 10% heat-inactivated FBS. Both RAW264.7 cells and the MH-S cells were cultured in an incubator at 37 °C and 5% CO2.

Mouse and Animal Experiments

C3H/HeJ (TLR4d), C3H/HeOuJ, and C57BL/6 mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME), and all animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at The Scripps Research Institute and Medical University of Ohio. Mice were treated intranasally with LPS (0.3 mg/kg) in 50 μl of sterile PBS (control), administered under light anesthesia. Broncho-alveolar lavage (BAL) was performed by cannulating the trachea and performing lavage with 1 ml of sterile PBS. To characterize airway cells, cytocentrifuge slides prepared using BAL fluid were stained with Wright-Giemsa stain and examined by light microscopy. BAL fluid cytokine levels were measured by ELISA using commercially available kits.

Isolation of BMDMs and Culture

8–10-week old mice were euthanized and bone marrow cells obtained from femurs by flushing the bone marrow cavities with complete media (RPMI (Cell-Gro, Kansas City, MO), 10% horse serum (Invitrogen), 0.5% glutamax, 1% penicillin-streptomycin, 0.1% 2-mercaptoethanol, and 30% L929 supernatant (source of M-CSF)). Bone marrow cells were cultured for 4 days in the complete medium in an incubator at 37 °C and 5% CO2. On the fourth day, the medium was changed, and the cells cultured for another 2 days. On the sixth day the cells were detached using a rubber policeman and centrifuged at 1,100 rpm for 5 min at 4 °C. The BMDM were then counted and re-plated at a density of 1–3 × 106 cells per ml into 6- or 24-well culture dishes, depending on the experiment.

In Vitro LPS Stimulation

BMDMs or RAW264.7 cells were treated with 10 ng/ml of Escherichia coli (0111:B4) ultra pure LPS (InvivoGen, San Diego, CA) for the indicated times. Culture supernatants were collected, aliquoted, and frozen. Total RNA or protein lysates were prepared from the cells and frozen. All samples were stored at −80 °C until analyzed.

ELISA

On the day of the assay, supernatant samples were thawed, speed-vacuumed by the SPD 1010 speed vac (Thermo Electron Corporation, Waltham, MA), and analyzed for secreted IL-4 and TNF-α by ELISA (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Western Blot

Following stimulation with LPS, cells were washed with 1× PBS (Invitrogen) and treated with 60 μl of lysis buffer (150 mm NaCl, 5 mm EDTA, pH 8, 1% Triton-X 100, 10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 1 mm sodium orthovanadate, and one tablet of protease inhibitor mixture in 50 ml of lysis buffer) for 15 min on ice then centrifuged at 13,000 rpm, 4 °C for 15 min. Supernatants were collected and the protein concentrations were determined by Bradford assay using the Coomassie Protein Assay Reagent (Pierce) and the Bio-Rad spectrophotometer. 10 μl of 2× SDS buffer (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was added to the lysate having equal amounts of protein and boiled at 95 °C for 6 min, placed on ice for 2 min, and then centrifuged for 1 min at 13,000 rpm. Equal amounts of protein (50 μg) were loaded in each lane and separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel (12%) electrophoresis. Fractionated proteins were blotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad). Blots were probed with specific antibodies to IL-4 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), MyD88 (ProSci, Proway, CA), or TRAM (ProSci, Proway, CA) followed by horseradish peroxidase-labeled mouse anti-goat IgG (Bio-Rad) and goat antirabbit IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), respectively and visualized by SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (Pierce) and the fluorchem 890 (Alpha Innotech, San Leandro, CA) detection system. To re-confirm an equal loading, the probed membrane was stripped (2% SDS, 62.5 mm Tris-HCl, 100 mm 2-ME, and pH adjusted to 6.5) and re-probed with antimouse β-actin monoclonal antibody (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA) followed by horseradish peroxidase-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG (Bio-Rad), and visualized as above.

Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted using the TRIzol (Invitrogen) technique following manufacturer's protocol. Any residual DNA contaminant in the resulting RNA was removed by DNase I treatment using the DNA-free kit (Ambion, Austin, TX) according to the protocol provided. 1 μg of total RNA was reverse-transcribed to cDNA using Omniscript RT kit (Qiagen, Hatsworth, CA) following the manufacturer's protocol. Negative control samples (no first-strand synthesis) were prepared by performing reverse transcription reactions in the absence of reverse transcriptase. Quantitative real time PCR was carried out with cDNA using SYBR Green 1 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) gene-specific primers (IL-4: 5′ sense AGCTAGTTGTCATCCTGCTCT, 3′ antisense GCATGGAGTTTTCCCATGTTT; TNF-α: 5′ sense GACCCTCACACTCAGATCATCTTC, 3′ antisense CGCTGGCTCAGCCACTCC; β-actin: 5′ sense TGGAATCCTGTGGCATCCATGAAAC, 3′ antisense TAAAACGCAGCTCAGTAACAGTCCG) (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA) and an ABI Prism 7500 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The threshold cycle (Ct) value was calculated from amplification plots, and gene expression was normalized using the Ct of the housekeeping gene β-actin. Fold induction of the target gene was then calculated using the formula 2̂−ΔΔCt.

Expression Plasmids and Luciferase Assay

The luciferase reporter plasmid containing the DNA sequences encoding the 5′ upstream IL-4 (pIL-4-luc) promoter was a kind gift of Dr. Kenneth Murphy (21). The MyD88 dominant negative construct pcDNA3-MyD88DN was generated as described (22). RAW264.7 cells were plated at a density of 3 × 105 cells per well in 24-well tissue culture plates, and 24 h later they were co-transfected with 0.35 μg of pIL-4-luc and 0.05 μg pRL-tk-null-luc (reporter gene) (Promega, Madison, WI) using FuGENE 6 according to the manufacturer's protocol. 24-h post-transfection, the cells were stimulated with 10 ng/ml LPS for varying times or left unstimulated. Following stimulation the luciferase activity was measured by utilizing the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega, Madison, WI) according to the protocol provided and the Monolight 3010 luminometer (BD Biosciences/Pharmingen, San Jose, CA). For experiments with dominant negative MyD88, the RAW264.7 cells were cotransfected with either pcDNA3-MyD88DN and pIL-4-luc and pRL-tk-null-luc or pcDNA3 and pIL-4-luc and pRL-tk-null-luc and then stimulated with LPS for measuring luciferase activity.

RNA Interference

Custom-designed small interfering RNA duplexes were purchased from Dharmacon (Lafayette, CO) and cells were transfected with DharmaFECT 2 transfection reagent (Dharmacon). Transfection efficiency of the siRNA's in RAW264.7 was determined by co-transfecting siGLO control with either of the siRNA and then visualizing the effect using fluorescence microscopy. To determine the efficiency of gene silencing, the whole cell lysate of the above co-transfected cells was used for Western blotting as described above and probed using specific antibodies for MyD88 and TRAM. The control groups were co-transfected with siRNA RISC (RNA-induced silencing complex)-free, nontargeting control and nontransfected group. β-actin was used as loading control, and the protein expressions were also normalized to it to determine the silencing efficiency. For reporter assays RAW264.7 cells (3 × 105 cells/well) were transfected individually (100 nm each) or co-transfected (50 nm each) with the siRNAs, 3 h prior to the transfection of the 0.35 μg of pIL4-luc and 0.05 μg of pRL-tk-null-luc in the 24-well tissue culture plates. 24-h post-transfection; cells were stimulated with LPS for different times following which luciferase activity was measured. For siRNA transfection of MH-S cells and the BMDMs we used amaxa electroporation technique utilizing cell line nucleofector Kit V (Amaxa Biosystems, Gaithersburg, MD) and mouse macrophage nucleofector kit (Amaxa Biosystems), respectively, following the manufacturer's protocol.

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed with Student's t test. p values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

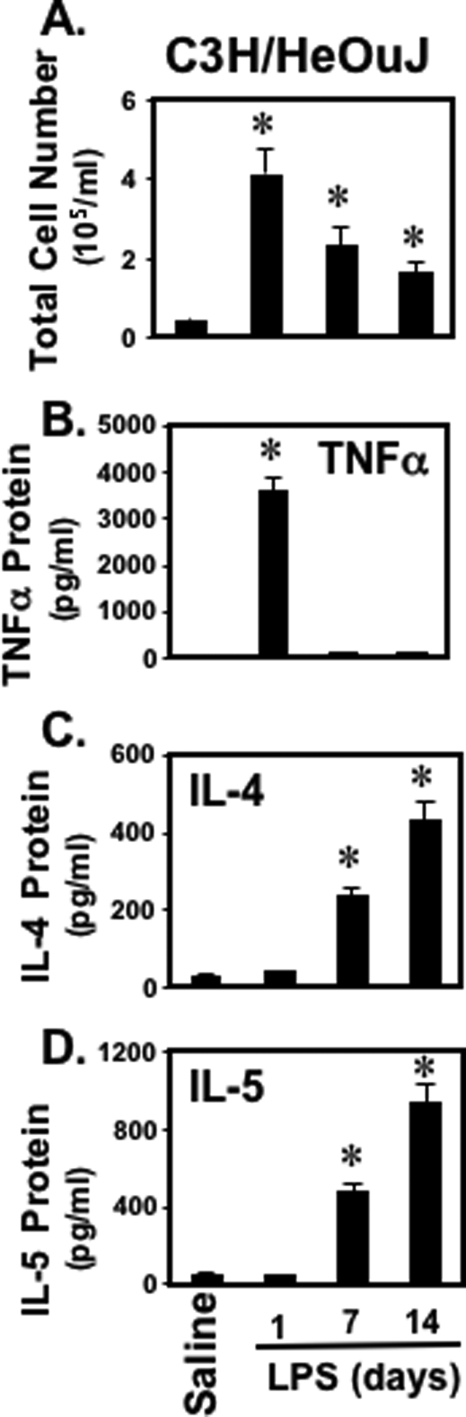

LPS Induces Type 2 Cytokine Production in Vivo

We first determined whether intranasal administration of bacterial LPS induced in vivo type 2 cytokine production in C3H/HeOuJ mice, which are responsive to LPS. Mice were treated with LPS (0.3 mg/kg) administered intranasally in 50 μl of sterile phosphate-buffered saline. After 1, 7, or 14 days, bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid was assessed for total cells (Fig. 1A) as well as levels of type 1 cytokine (TNFα) (Fig. 1B) and type 2 cytokines (IL-4 and IL-5) (Fig. 1, C and D). Mice exposed to LPS had significantly more cells in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) than did the mice exposed to saline (Fig. 1A). There was also a dramatic and significant increase in the amount of type 2 cytokines (IL-4, IL-5) in BALF when mice received LPS (Fig. 1, C and D). Collectively, these data demonstrate that bacterial LPS can induce a significant type 2 response in the murine model of lung inflammation.

FIGURE 1.

LPS induces type 1 and type 2 cytokine production in the murine model of lung inflammation. C3H/HeOuJ mice were treated intranasally with LPS (0.3 mg/kg) in 50 μl of sterile saline. After 1, 7, or 14 days, mice were sacrificed, and the BAL fluid was assessed for the total cell counts (A) as well as levels of cytokines, including: TNFα (B), IL-4 (C), and IL-5 (D). Cytokine levels were measured by ELISA. Data are expressed as mean ± S.E. of three different experiments, and each had five mice per group. Significance (p < 0.05), indicated by an asterisk, is LPS-challenged animals versus saline-treated animals.

LPS Induces Type 2 Cytokine Production in Vitro

We next determined whether bacterial LPS also induced type 2 cytokine gene expression in macrophages. RAW264.7 murine macrophages, MH-S murine alveolar macrophages or BMDMs from C57BL/6 mice were stimulated with LPS (10 ng/ml) for varying times. Both RAW264.7 and MH-S macrophages are derived from Balb/c mice. Because Balb/c mice are more predisposed to mount a Th2 response, we also wanted to study macrophages from C57BL/6 mice. LPS induced IL-4 mRNA (Fig. 2A) and TNFα mRNA (Fig. 2B) expression in a time-dependent manner compared with the control. The kinetics were similar for all three macrophage cell types in that there was a markedly different kinetic response seen between IL-4 and TNFα induced by LPS. TNFα mRNA increased rapidly, peaking at 4 h then falling rapidly, returning to baseline within 24 h. In contrast, there was little change seen in IL-4 mRNA levels until 36 h, and levels continued to increase at 48 h, the final time point sampled. Since induction of cytokine gene transcription does not necessarily correlate with protein translation and release, we also assessed cytokine secretion into the supernatant of LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 cells. Similar to the gene expression results, we observed a rapid but transient increase in TNFα secretion, with a delayed and sustained increase in IL-4 secretion (Fig. 2, C and D). Thus our data suggest that LPS induces a dual response in macrophages. This dual response consists of a rapid but transient stimulation of TNFα, followed by a delayed and sustained stimulation of IL-4.

FIGURE 2.

LPS induces IL-4 and TNFα gene expression in macrophages. A, RAW264.7, MH-S, and BMDMs cells were plated at a density of 1 × 106 cells per well in 6-well plates. A day later the cells were stimulated with or without LPS (10 ng/ml) for varying times (1, 2, 4, 8, or 24 h for TNF-α) and (8, 24, 36, or 48 h for IL-4). The cells were then lysed with TRIzol, total RNA was extracted, and cDNA was reverse-transcribed. The cDNA was then analyzed for IL-4 (A) and TNF-α (B) mRNA by real time gene amplification using relevant primers and Sybr green 1. Error bars represent S.D. from the average of three readings. The figures are representatives of five independent experiments done in triplicates. C, LPS induces IL-4 protein release in macrophages. RAW264.7 cells plated at a density of 3 × 105 cells per well in 24-well plate tissue culture plates were stimulated with LPS for varying times. The supernatants were analyzed for murine IL-4 (C) or TNF-α (D) by ELISA according to the manufacturer's instructions. All the experiments were repeated three times and yielded similar results. Significance (p < 0.05), indicated by *, is LPS-treated cells versus LPS-untreated cells.

LPS-induced Cytokine Release Is TLR4-dependent

The discovery that TLR4 encodes the LPS receptor and transduces the effect of stimulation with LPS was a major advance in our understanding of LPS-mediated cytokine gene transcription. Nevertheless, it has become clear that many LPS preparations may be contaminated with other PAMPs, and thus that the consequences of LPS stimulation may reflect signaling through TLRs other than TLR4. Therefore, we investigated the role of TLR4 in LPS-induced macrophage IL-4 production using a TLR4 functional antibody (TLR4fAb) that blocks binding of LPS to TLR4. Pretreatment of RAW264.7 cells with the TLR4fAb completely abrogated the LPS-induced IL-4 release in macrophages (Fig. 3A), indicating that LPS-induced IL-4 release in macrophages requires LPS binding to TLR4. To further confirm this result we compared the responses in BMDMs from TLR4-sufficient mice (C3H/HeOuJ) to the responses in TLR4-defective mice (C3H/HeJ). Primary BMDMs were stimulated with LPS for different times (12, 24, and 48 h) and IL-4 mRNA measured by quantitative RT-PCR. Stimulation of TLR4-defective BMDMs with LPS failed to induce IL-4 mRNA (Fig. 3C). In striking contrast, LPS-induced robust IL-4 mRNA up-regulation in TLR4-sufficient BMDMs (Fig. 3B).

FIGURE 3.

LPS-induced IL-4 release is TLR4-dependent in macrophages and in the murine model of lung inflammation. RAW264.7 cells were pretreated with functional antibody of TLR4 (TLR4fAb) for 1 h and then stimulated with LPS for 72 h. The supernatant was collected, and IL-4 ELISA was done using the manufacturer's protocol (A). BMDMs from C3H/HeOuJ (B) and C3H/HeJ (C) mice were stimulated with or without LPS for 12, 24, or 48 h. The cells were lysed with TRIzol and frozen at −80 °C. On the day of the experiment, the samples were thawed, total RNA was extracted, and cDNA was reverse-transcribed. The cDNA was then amplified by real time PCR using IL-4 primers and Sybr Green 1. The experiment is a representative of three independent experiments using two mice each time. Results are expressed as mean ± S.D. C3H/HeOuJ and C3H/HeJ mice were treated intranasally with LPS (0.3 mg/kg) in 50 μl of sterile phosphate-buffered saline. After 2 weeks, mice were sacrificed, and the BAL fluid was assessed for total cell counts (D and E), and IL-4 was measured by ELISA (F and G). Data are expressed as mean ± S.E. of three different experiments, and each had five mice per group. *, p < 0.05 compared with CON; **, p < 0.05 compared with LPS treatment without TLR4 fAb.

We then compared the consequences of intranasal challenge with LPS in TLR4-defective (C3H/HeJ) and TLR4-sufficient mice (C3H/HeOuJ). TLR-sufficient mice demonstrated the expected increase in total BALF cells (Fig. 3D) and IL-4 protein (Fig. 3F). In contrast, TLR4-defective mice failed to show either an increase in BALF cell number (Fig. 3E) or IL-4 protein (Fig. 3G). These in vivo results are consistent with the in vitro results above and conclusively demonstrate that bacterial LPS-induced IL-4 production in macrophages and the airway are TLR4-dependent. Collectively, these data demonstrate that bacterial LPS-induced type 2 cytokine production in a TLR4-dependent manner.

LPS-induced IL-4 Cytokine Response Is MyD88/TRAM- dependent

LPS-induced TNFα synthesis has previously been shown to be TLR4-dependent, mediated through the signal transduction molecule MyD88 (19). We tested whether LPS-induced IL-4 production was also mediated through MyD88. RAW26.7 cells were transiently co-transfected with a dominant negative form of MyD88 as well as a chimeric IL-4 luciferase plasmid. Fig. 4A shows that the dominant negative MyD88 only partially blocked LPS-induced IL-4 luciferase activity. We, therefore, hypothesized that the MyD88-independent TRIF/TRAM signaling pathway may contribute to LPS-induced IL-4 synthesis. To address this, we utilized a small interfering RNA approach to knockdown MyD88 or TRAM (highly specific for TLR4). RAW264.7 cells were co-transfected with pIL-4-luc plus siRNA against MyD88, siRNA against TRAM, or siRNA against both MyD88 and TRAM. While siRNA MyD88 (Fig. 4B, lane 3) and siRNA TRAM (Fig. 4B, lane 4) each partially inhibited LPS-driven IL-4 luciferase activity, knocking down MyD88 and TRAM simultaneously resulted in almost complete abrogation of LPS-driven luciferase activity (Fig. 4B, lane 5). Consistent with these results, we also showed that silencing either MyD88 or TRAM partially inhibited IL-4 protein secretion but that simultaneous silencing of both MyD88 and TRAM led to complete blockade of IL-4 release in the RAW264.7 cells (Fig. 5A). We also employed a siRNA approach to silence MyD88 and TRAM in the MH-S alveolar macrophage cell line (Fig. 4C) as well as in primary BMDMs from C57BL/6 mice (Fig. 4D) using the Amaxa electroporation technique. These data again indicated that MyD88-dependent and MyD88-independent pathways are both involved in LPS-induced type 2 cytokine production.

FIGURE 4.

LPS-induced Th2 response is MyD88/TRAM-dependent in murine macrophages. RAW264.7 cells (A) were co-transfected with pcDNA3-MyD88DN and pIL4-luc then stimulated with LPS for 24 h following which the luciferase activity was measured. *, p value < 0.05. RAW264.7 (B), MH-S (C), and BMDM (D), cells were co-transfected with siRNA MyD88 or siRNA TRAM or both together with pIL4-luc. One day post-transfection, the whole cell lysate was separated by SDS-PAGE and blotted with anti-MyD88 or anti-TRAM antibodies. Another set of cells were stimulated with media or LPS for 48 h, and then luciferase gene activity was determined with 3010 luminometer. The experiment is a representative of three independent experiments. Results are expressed as mean ± S.D. Statistical analysis was done using Student's t test, and p value < 0.05 was considered significant.

FIGURE 5.

LPS-induced IL-4 protein release requires both MyD88 and TRAM pathways, while LPS-induced TNF-α protein release is MyD88-dependent and TRAM-independent. RAW264.7 cells were transfected with siRNA against MyD88 or siRNA against TRAM or both together. A day later, the cells were stimulated with LPS for the indicated times. The supernatants were collected and were utilized to measure IL-4 (A) and TNF-α (B) levels by ELISA, following the manufacturer's protocol. The experiment was repeated three times with similar results. Results are expressed as mean ± S.D. Statistical analysis was done using the Student's t test, and a p value < 0.05 was considered significant.

Differential Regulation of LPS-driven IL-4 and TNFα Cytokines in Macrophages

We showed that LPS-driven TNFα and IL-4 production in macrophages are both TLR4-dependent, but that the type 1 cytokine response is early while the type 2 cytokine response is delayed. To clarify this difference, we assessed whether LPS-stimulated IL-4 and TNFα responses utilize different TLR4 adaptor proteins in RAW264.7 cells. We confirmed that LPS-induced TLR4-dependent IL-4 production requires both MyD88-dependent and MyD88-independent (TRAM-dependent) pathways (Fig. 5A). LPS-induced TLR4-dependent TNFα production, however, was only dependent on MyD88 and was independent of TRAM (Fig. 5B) (23). Taken together, our data indicate that the MyD88-dependent pathway is necessary and sufficient for LPS-stimulated TNFα production in macrophages, but that LPS-stimulated IL-4 production requires both MyD88-dependent and MyD88-independent pathways.

DISCUSSION

Endotoxin or its purified derivative LPS is a key activator of the innate immune system, stimulating mononuclear phagocytes to synthesize an array of cytokines and chemokines that recruit inflammatory cells to the involved tissue as well as activating immune and inflammatory responses (4, 25). While LPS is an essential component of the innate immune response to microorganisms, repeated exposure to inhaled LPS also occurs as a consequence of its nearly ubiquitous presence in environmental dust (26–28). In previous studies, we and others have demonstrated that LPS stimulates activation of NF-κB and production of type 1 cytokine gene expression in macrophages (29–31). The ability of LPS to stimulate type 2 cytokine gene expression from macrophages is not nearly as well described. Furthermore little is known regarding the cellular signaling pathways transducing these effects. The present study provides evidence that LPS induces type 2 cytokine production in vitro and in vivo. Our results also demonstrate that the signaling pathway leading to LPS-induced IL-4 involves TLR4, MyD88, and TRAM. These results indicate, for the first time, that LPS-stimulated type 1 cytokine production is MyD88-dependent, whereas LPS-stimulated IL-4 production requires both MyD88-dependent and MyD88-independent pathways.

Using C3H/HeOuJ and C3H/HeJ mice, macrophage cell lines, as well as primary macrophages, we showed that LPS stimulated IL-4 synthesis in a TLR4-dependent manner both in vitro and in vivo. Although a previous study has shown that low dose of LPS initiates type 2 immunity and high doses cause type 1 immunity (6), our data showed that LPS induces both type 1 and type 2 cytokines in a time-dependent manner, with a transient TNFα response being induced early whereas IL-4 had a delayed but sustained induction. This difference in the timing of the cytokine response appeared to correlate with differential utilization of downstream TLR4 signaling pathways. LPS-stimulated TNFα production exclusively utilized the MyD88-dependent pathway while LPS-stimulated IL-4 production involved both MyD88-dependent and -independent pathways.

Macrophages play pivotal roles in host response to injury and are exquisitely sensitive to the major outer membrane component of Gram-negative bacteria, LPS, signaling through TLR4. Activation of TLR4 on antigen presenting cells triggers up-regulation of proinflammatory cytokines, co-stimulatory molecules, and chemokines, paving the path for the activation of naïve T cells (32, 33). Thus it is hypothesized that TLR4 signaling has the ability to shape the adaptive immune response, thereby emphasizing the basis of immunological discrimination between self and microbial non-self (34). The type 1 proinflammatory cytokine response from LPS stimulation of macrophages has been extensively studied. Recent evidence suggests that LPS may also stimulate type 2 cytokines from macrophages (35, 36); however the nature of this response and the underlying signaling events remain poorly understood. Moreover recent epidemiological evidence suggested that exposure to LPS influences the development and severity of various inflammatory disorders, including asthma, due to aberrant type 2 responses (particularly IL-4) (6).

The contribution of LPS to asthmatic airway inflammation appears complex. Recent data suggest that exposure to LPS prior to allergic sensitization may protect against subsequent sensitization and development of asthma (37, 38); however, exposure to LPS in established asthmatic subjects appears to worsen airway inflammation and bronchial hyperresponsiveness (27) and inhalation of endotoxin has been shown to potentate antigen-specific IgE responses in mice (39). Clinical studies have shown that asthmatic subjects develop airway inflammation and bronchospasm at much lower doses of inhaled LPS than normal subjects (26, 27), and this hyperresponsiveness to LPS is further heightened following allergen exposure (40). Furthermore, asthma severity has been linked to the concentration of LPS in house dust samples (40). Our data suggest that prolonged stimulation of macrophages with LPS can induce delayed but sustained IL-4 secretion. This observation stands in contrast to prior reports indicating that TLR signaling is not important for the induction of type 2 responses (24). Our results suggest that LPS has a dual effect on macrophages, stimulating an initial type 1 cytokine response that is then followed by a more sustained type 2 cytokine response. Considering that most people are subjected to repeated environmental exposures to LPS, our results suggest that the dual effect of LPS on airway macrophages could play a significant role in directing in vivo adaptive immune responses, including the development of type 2 cytokine responses.

In summary, we have shown that LPS, acting through TLR4, activates both type 1 and type 2 cytokine production in vitro and in vivo. We have also shown that LPS-induced TNFα production in macrophages is rapid, MyD88-dependent, and TRAM-independent; while LPS-induced IL-4 production in macrophages is delayed, sustained, and requires both MyD88 and TRAM signaling pathways (Fig. 6). These findings provide the first evidence that a single dose of LPS mediates both type 1 and type 2 cytokine responses through distinct kinetic patterns and signaling mechanisms.

FIGURE 6.

Schematic representation depicting LPS, acting through TLR4, activates both Th1 and Th2 cytokine production in macrophages. As indicated, LPS is an early Th1 cytokine inducer, which is MyD88-dependent, and LPS is also a delayed Th2 cytokine inducer that is both MyD88- and TRAM-dependent.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant M01RR00833 provided to the General Clinical Research Center of the Scripps Research Institute. This work was also supported by USPHS Grants AI43524 and by the Sam and Ross Stein Charitable Trust.

- PAMP

- pathogen-associated molecular patterns

- LPS

- lipopolysaccharide

- TLR4

- Toll-like receptor 4

- BMDMs

- bone marrow-derived macrophages

- ActD

- actinomycin D

- CHX

- cycloheximide

- MyD88

- myeloid differentiation protein

- TRAM

- TRIF-related adaptor molecule

- TRIF

- TIR domain-containing adaptor-inducing interferon-γ

- TIR

- Toll/interleukin-1 resistance domain

- TNF

- tumor necrosis factor

- NF-κB

- nuclear factor κB

- QRT-PCR

- quantitative real time-PCR

- IL

- interleukin

- ELISA

- enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- AM

- human alveolar macrophages

- siRNA

- small interfering RNA.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rock F. L., Hardiman G., Timans J. C., Kastelein R. A., Bazan J. F. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 588–593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gioannini T. L., Teghanemt A., Zhang D., Coussens N. P., Dockstader W., Ramaswamy S., Weiss J. P. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 4186–4191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pouliot P., Turmel V., Gélinas E., Laviolette M., Bissonnette E. Y. (2005) Clin. Exp Allergy 35, 804–810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Svanborg C., Godaly G., Hedlund M. (1999) Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2, 99–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matsukawa A., Yoshinaga M. (1998) Inflamm. Res. 47, Suppl. 3, S137–S144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eisenbarth S. C., Piggott D. A., Huleatt J. W., Visintin I., Herrick C. A., Bottomly K. (2002) J. Exp. Med. 196, 1645–1651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paul W. E. (1991) Blood 77, 1859–1870 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doucet C., Brouty-Boyé D., Pottin-Clemenceau C., Jasmin C., Canonica G. W., Azzarone B. (1998) Int. Immunol. 10, 1421–1433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moser R., Fehr J., Bruijnzeel P. L. (1992) J. Immunol. 149, 1432–1438 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dombrowicz D., Capron M. (2001) Curr. Opin. Immunol. 13, 716–720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wills-Karp M. (1999) Annu. Rev. Immunol. 17, 255–281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Min B., Prout M., Hu-Li J., Zhu J., Jankovic D., Morgan E. S., Urban J. F., Jr., Dvorak A. M., Finkelman F. D., LeGros G., Paul W. E. (2004) J. Exp. Med. 200, 507–517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yoshimoto T., Paul W. E. (1994) J. Exp. Med. 179, 1285–1295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Plaut M., Pierce J. H., Watson C. J., Hanley-Hyde J., Nordan R. P., Paul W. E. (1989) Nature 339, 64–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moqbel R., Ying S., Barkans J., Newman T. M., Kimmitt P., Wakelin M., Taborda-Barata L., Meng Q., Corrigan C. J., Durham S. R., Kay A. B. (1995) J. Immunol. 155, 4939–4947 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dabbagh K., Dahl M. E., Stepick-Biek P., Lewis D. B. (2002) J. Immunol. 168, 4524–4530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O'Neill L. A., Fitzgerald K. A., Bowie A. G. (2003) Trends Immunol. 24, 286–290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vogel S. N., Fitzgerald K. A., Fenton M. J. (2003) Mol. Interv. 3, 466–477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pålsson-McDormott E. M., O'Neil L. A. (2004) Immunology 113, 153–162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fitzgerald K. A., Rowe D. C., Barnes B. J., Caffrey D. R., Visintin A., Latz E., Monks B., Pitha P. M., Golenbock D. T. (2003) J. Exp. Med. 198, 1043–1055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wenner C. A., Szabo S. J., Murphy K. M. (1997) J. Immunol. 158, 765–773 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen L. Y., Zuraw B. L., Liu F. T., Huang S., Pan Z. K. (2002) J. Immunol. 169, 3934–3939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kawai T., Adachi O., Ogawa T., Takeda K., Akira S. (1999) Immunity 11, 115–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schnare M., Barton G. M., Holt A. C., Takeda K., Akira S., Medzhitov R. (2001) Nat. Immunol. 2, 947–950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matsukawa A., Yoshinaga M. (1998) Inflamm. Res. 47, Suppl. 3, S137–S144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Michel O., Duchateau J., Sergysels R. (1989) J. Appl. Physiol. 66, 1059–1064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Michel O., Ginanni R., Le Bon B., Content J., Duchateau J., Sergysels R. (1992) Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 146, 352–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Michel O., Nagy A. M., Schroeven M., Duchateau J., Nève J., Fondu P., Sergysels R. (1997) Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 156, 1157–1164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen L. Y., Zuraw B. L., Zhao M., Liu F. T., Huang S., Pan Z. K. (2003) Am. J. Physiol. 284, L607–L613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Honstettre A., Ghigo E., Moynault A., Capo C., Toman R., Akira S., Takeuchi O., Lepidi H., Raoult D., Mege J. L. (2004) J. Immunol. 172, 3695–3703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barton G. M., Medzhitov R. (2003) Science 300, 1524–1525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luster A. D. (2002) Curr. Opin. Immunol. 14, 129–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goldstein D. R. (2004) Curr. Opin. Immunol. 16, 538–544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yamane H., Zhu J., Paul W. E. (2005) J. Exp. Med. 202, 793–804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Büttner C., Skupin A., Reimann T., Rieber E. P., Unteregger G., Geyer P., Frank K. H. (1997) Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 17, 315–325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gereda J. E., Leung D. Y., Thatayatikom A., Streib J. E., Price M. R., Klinnert M. D., Liu A. H. (2000) Lancet 355, 1680–1683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Holt P. G. (1995) Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 6, 1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wan G. H., Li C. S., Lin R. H. (2000) Clin. Exp. Allergy 30, 426–432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eldridge M. W., Peden D. B. (2000) J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 105, 475–481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Michel O., Kips J., Duchateau J., Vertongen F., Robert L., Collet H., Pauwels R., Sergysels R. (1996) Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 154, 1641–1646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]