Abstract

γ-Secretase is a proteolytic membrane complex that processes a variety of substrates including the amyloid precursor protein and the Notch receptor. Earlier we showed that one of the components of this complex, nicastrin (NCT), functions as a receptor for γ-secretase substrates. A recent report challenged this, arguing instead that the Glu-333 residue of NCT predicted to participate in substrate recognition only participates in γ-secretase complex maturation and not in activity per se. Here, we present evidence that Glu-333 directly participates in γ-secretase activity. By normalizing to the active pool of γ-secretase with two separate methods, we establish that γ-secretase complexes containing NCT-E333A are indeed deficient in intrinsic activity. We also demonstrate that the NCT-E333A mutant is deficient in its binding to substrates. Moreover, we find that the cleavage of substrates by γ-secretase activity requires a free N-terminal amine but no minimal length of the extracellular N-terminal stub. Taken together, these studies provide further evidence supporting the role of NCT in substrate recognition. Finally, because γ-secretase cleaves itself during its maturation and because NCT-E333A also shows defects in γ-secretase complex maturation, we present a model whereby Glu-333 can serve a dual role via similar mechanisms in the recruitment of both Type 1 membrane proteins for activity and the presenilin intracellular loop during complex maturation.

The brains of Alzheimer disease patients are characterized by dense neuritic plaques that consist of the insoluble β-amyloid peptide (Aβ)2 and neurons containing neurofibrillary tangles of the Tau protein (1, 2). The Aβ peptide is produced via the sequential proteolysis of APP by β- and γ-secretase (3). γ-secretase is a multisubunit complex consisting of at least four proteins: presenilin (PS), NCT, APH-1, and PEN-2, all of which are necessary and sufficient for activity (4–9). The formation of the γ-secretase complex is tightly controlled, with an ordered assembly of subunits coupled to spatial restriction (10). It is believed that the last step of the complicated γ-secretase maturation and activation process involves in cis endoproteolysis of the PS holoprotein (11–13). It is this form of γ-secretase with PS in its N- and C-terminal fragments (NTF and CTF, respectively) that represents the fully mature, proteolytically active enzyme.

γ-Secretase is a unique protease that cleaves within the lipid bilayer a large number of Type 1 single transmembrane-spanning proteins that vary widely in their sequence and size (14–16). In a previous report, we demonstrated that NCT functions as a substrate receptor for γ-secretase (4). In that report, we showed that NCT recruits substrates that have had their large extracellular domains first removed by an upstream protease in a process termed “ectodomain shedding.” This process generates a new, short extracellular stub with a free N terminus, which is required for proteolysis by γ-secretase. We also established that Glu-333 of NCT participates in activity within the larger context of the DYIGS and peptidase-like (DAP) domain, which shares distant homology to amino- and carboxypeptidases. A recent study by Chávez-Gutiérrez et al. (17) confirmed that mutations at the equivalent rodent residue impair γ-secretase. However, the authors attributed the reduction in activity to a role for Glu-333 in γ-secretase maturation but not directly in activity per se. Although a role for NCT and Glu-333 in γ-secretase assembly and maturation is consistent with our early work (4, 18, 19), the authors' conclusion that mature γ-secretase complexes containing the Glu-333 mutant NCT are fully active presents a challenge to the model that NCT is a receptor for γ-secretase substrates in mature, active enzyme. Although PS-NTF or -CTF alone is an adequate measure of active γ-secretase complexes, Chávez-Gutiérrez et al. (17) measured specific activity by normalizing γ-secretase products to the sum of PS1-CTF and PEN-2 presumably due to the levels of PS-NTF/CTF by themselves being at the detection limit of Western blotting with electrochemiluminescence (ECL). Such an approach has caveats, as normalizing to the sum of PS1 and PEN-2 does not represent a measurement of the intrinsic activity per single, active enzyme; rather, this mode of normalization instead skews the data to minimize the effects of the mutations, especially when compounded with the unreliability of ECL measurement at the detection limit of Western blotting. Indeed, normalizing to the amount of mature, active γ-secretase in a rigorous, quantitative manner would be necessary to accurately compare the intrinsic activities of wild-type and mutant enzymes.

In this study we used two γ-secretase reconstitution methods, including one that bypasses endoproteolysis and two separate normalization approaches to demonstrate that γ-secretase complexes containing NCT-E333A are indeed intrinsically less active than wild-type NCT. We show that this mutant is deficient in its ability to directly bind to γ-secretase substrates. Moreover, we confirm our observations with a second γ-secretase substrate, C83, which is itself the physiological product of α-secretase cleavage of APP. We also examine a series of substrate truncation mutants and find that γ-secretase can cleave substrates that lack the entire extracellular domain, provided that such substrates also contain a free N-terminal amine. Taken together, we conclude that Glu-333 participates directly in activity after γ-secretase complex maturation. Finally, we put forth a model wherein the dual role of Glu-333 in γ-secretase maturation and substrate recognition could be explained in the context of NCT being a substrate receptor. In this model Glu-333 partakes in the recruitment of not only the ectodomain-shed Type 1 membrane proteins but also of the intracellular loop of PS for its endoproteolysis, a hallmark event of γ-secretase maturation and activation.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

C100FLAG was custom synthesized by Upstate Biotechnology. Restriction enzymes were from New England Biolabs, Inc. Electrophoresis reagents were from Bio-Rad. All other reagents and chemicals were reagent grade. PS1-NTF was detected with an antibody equivalent to Ab14 (12), NCT was detected with a rabbit polyclonal antibody raised against purified NCT ectodomain, V5His6-tagged NCT and APH-1aL was detected with α-His6 (Qiagen), HA-PEN-2 was detected with α-HA (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), C100 and related constructs was detected with α-APP-CTF (Sigma catalog no. A8717), and N100FLAGHis6 was detected with α-FLAG M2 (Sigma).

Construct Design

Human PS, NCT, NCT-E333A, APH-1aL-V5His6, and HA-PEN-2 were subcloned into the pFastBac1 vector (Invitrogen) as described previously (4). Human PS1-NTF and -CTF (residues Met-1—Met-292 in the EcoRI/HinDIII sites and Val-293—Ile-467 in the BbsI/XhoI sites, respectively) were similarly subcloned into the pFastBac-Dual vector of the same system. N-terminal deletions of C100FLAG were subcloned into the NdeI (5′) and HindIII (3′) sites using the pET21b-PA(−)-C100FLAG construct described earlier (4) as a template, the antisense primer 5′-AAGCTTCTACTTATCGTCATCGTC-3′ for all, and the following sense primers: 5′-GGAATTCCATATGTATGAAGTTCATCATCAAAAATTGG-3′ (NΔ8); 5′-GGAATTCCATATGGTGTTCTTTGCAGAAGATGTGGG-3′ (NΔ16); 5′-GGAATTCCATATGGAAGATGTGGGTTCAAACAAAGG-3′ (NΔ20); 5′-GGAATTCCATATGTCAAACAAAGGTGCAATCATTGG-3′ (NΔ24); 5′-GGAATTCCATATGGCAATCATTGGACTCATGG-3′ (NΔ28). Construction and purification of N100FLAGHis6 was described previously (4).

Recombinant γ-Secretase Expression and Purification from Baculovirus-infected Sf9 Cells

Sf9 cells were grown in suspension in EX-CELL 420 medium (Sigma-Aldrich) at 27 °C, with routine passage to 0.5 × 106 cells/ml. Before infection cells were diluted to 1.2 × 106 cells/ml in 500 ml and allowed to recover for 24 h. The appropriate baculovirus stocks were then diluted 1:200 per virus in this culture for infection. At 60 h post-infection, cells were harvested by centrifugation at 1000 × g for 20 min at 4 °C. Cell pellets were resuspended in 40 ml of lysis buffer A (20 mm HEPES, pH 7.5, 50 mm KCl, 2 mm EGTA, plus Roche EDTA-free protein inhibitor mixture). The resuspended pellet was homogenized using a Dounce homogenizer before lysis via three passages through a Parr bomb at >1500 p.s.i. Intact cells were removed by spinning at 1000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C, and the resulting supernatant was spun at 100,000 × g for 1 h at 4 °C. This 100,000 × g pellet was then resuspended by homogenization in lysis buffer A plus 5% glycerol, separated into aliquots, and stored at −80 °C for future use. Partially purified γ-secretase was prepared from these membranes by thawing these aliquots and spinning at 100,000 × g for 1 h at 4 °C. The resulting pellet was resuspended by homogenization in 5 volumes of 1% CHAPSO in extraction buffer B (20 mm HEPES, pH 7.0, 150 mm NaCl, 5 mm EDTA, plus Roche EDTA-free protein inhibitor mixture). Membranes were then extracted by end-over-end rotation in this buffer for 1 h at 4 °C followed by 1:1 dilution in buffer B without detergent and centrifugation at 100,000 × g for 1 h at 4 °C. Protein concentration was measured by BCA protein assay (Thermo Scientific) and diluted when appropriate with Buffer B supplemented with 0.5% CHAPSO.

Ni-NTA Pulldown of γ-Secretase Complexes

Sf9 cells were infected with baculoviruses expressing holo-PS1 or PS1-NTF/CTF, wild-type NCT-V5His6 or NCT-E333A-V5His6, APH-1aL-V5His6, and HA-PEN-2 as described above. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 1000 × g for 20 min at 4 °C and washed once with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline. The pellet was then resuspended in lysis buffer C (50 mm HEPES, pH 7.2, 150 mm NaCl, 5 mm EDTA, 5 mm imidazole, 1% CHAPSO, EDTA-free Roche protease inhibitors) and rocked for 1 h at 4 °C. The lysed cell suspension was then centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 20 min at 4 °C, and the resulting supernatant was incubated at 4 °C overnight with Ni-NTA beads (Qiagen) that had been prewashed with phosphate-buffered saline and 5 mm imidazole. γ-Secretase complexes were washed and eluted according to manufacturer's directions using wash buffer D (buffer C containing 300 mm NaCl) and elution buffer E (buffer C containing 250 mm imidazole, 0.5% CHAPSO without protease inhibitors). Inputs and eluates were analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting on polyvinylidene difluoride (Millipore Corp.).

Pulldown of C100FLAG with NCT

Sf9 cells were infected with baculoviruses expressing C100FLAG and either wild-type NCT-V5His6 or NCT-E333A-V5His6 as described above. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 1000 × g for 20 min at 4 °C and washed once with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline. The pellet was then resuspended in lysis buffer F (50 mm sodium phosphate, pH 7.2, 150 mm NaCl, 0.5% Triton X-100, EDTA-free Roche protease inhibitors) and rocked for 1 h at 4 °C. The lysed cell suspension was then centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 20 min at 4 °C, and the resulting supernatant was incubated at 4 °C overnight with anti-FLAG M2-agarose beads (Sigma) that had been prewashed with lysis buffer F. C100FLAG·NCT complexes were washed according to the manufacturer's directions using wash buffer G (buffer F containing 300 mm NaCl) and eluted with 100 mm glycine, pH 2.5, and neutralized with 0.1 volumes of 1 m Tris, pH 8.0, before use. Inputs and eluates were analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting on polyvinylidene difluoride.

Expression and Purification of Substrates from Bacteria

The bacterial expression vector pET21b-PA(−) containing substrate was transformed into the Escherichia coli host strain BL21(DE3) for expression and purification. Luria broth (LB) containing 75 μg/ml ampicillin was inoculated with a single bacterial colony and grown overnight at 37 °C. This was then used at a 1:50 dilution to inoculate 1 liter of LB-ampicillin at 37 °C to an A600 of 0.6–0.8. The culture was then chilled at 4 °C for 15 min before induction with 0.1 mm isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside overnight at room temperature. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 2500 × g for 10 min at 4 °C, and cells were resuspended in lysis buffer H (50 mm Tris, pH 7.5, 150 mm NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 1 mg/ml lysozyme, plus Roche EDTA-free protein inhibitor mixture). Cells were homogenized by a Dounce homogenizer and lysed by syringe with at least five passages each through 20.5½-gauge and 25½-gauge needles. The lysate was spun at 100,000 × g for 40 min at 4 °C, and the resulting supernatant was diluted 10-fold in phosphate-buffered saline plus 1% Nonidet P-40 before purification by anti-FLAG antibody affinity gel chromatography (Sigma) according to manufacturer's directions. Substrates were eluted in 100 mm glycine, pH 2.5, plus 1% Nonidet P-40 and neutralized with 0.1 volumes of 1 m Tris, pH 8.0, before use in γ-secretase assays. Protein concentration was measured by DC protein assay. α-Amino N-terminal formylated substrates were expressed from the E. coli host strain AG100A(DE3) as described previously (4). Induction and purification was performed as described above but with the addition of 2 μg/ml actinonin when adding isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside.

Saturation Binding of l-[3H]685,458 to Membranes

The number of γ-secretase binding sites (βmax) was determined similar to described previously (20). Briefly, labeled and unlabeled compound were incubated for 90 min at 37 °C with 1 mg/ml of CHAPSO membrane lysate and increasing amounts of tracer. Nonspecific binding (which represented <20% of the total binding) was determined for all experiments by adding an excess (1 μm) of unlabeled inhibitor, and serial dilutions of l-[3H]685,458 were used to obtain saturation binding isotherms from which βmax values were extracted. Experiments were performed in duplicate.

Cell-free γ-Secretase Activity Assay (APP Intracellular Domain (AICD))

Recombinant γ-secretase extracted from Sf9 cell membranes was assayed as described in Shah et al. (4). Briefly, 25 μg of γ-secretase preparation was combined with 2 μg of substrate in the presence or absence of 20 μm concentrations of the γ-secretase inhibitor N-[N-(3,5-difluorophenacetyl)-l-alanyl]-S-phenylglycine t-butyl ester (DAPT, dissolved in DMSO; Sigma). Samples were placed on a 37 °C heat block overnight (12–24 h), after which samples were run on 15% Tris-glycine SDS-PAGE. Gels were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride and probed for APP-CTF.

Quantification of γ-Secretase Activity (AICD)

Relative specific activity was quantified from four independent experiments using ImageJ software (rsb.info.nih.gov). Briefly, the integrated density of each AICD band and the corresponding PS1-NTF band were calculated. AICD production was normalized to PS1-NTF levels, from which the values for DAPT-treated samples were subtracted for a measure of specific γ-secretase activity. The relative specific activity within each NCT-WT/E333A pairing was then measured as a ratio of mutant NCT activity versus WT activity (defined as unity).

Cell-free γ-Secretase Activity Assay (Aβ40 and Aβ42)

Recombinant γ-secretase was extracted from Sf9 cell membranes as described above and assayed for Aβ40 and Aβ42 production by ELISA (Meso Scale Discovery). Assays were performed similar to those for AICD detection, with the exception of using 100 μg of γ-secretase preparation and 15 μg of substrate. Samples were placed in a 37 °C humid incubator overnight (18 h), after which they were assayed for Aβ40 and Aβ42 production using Aβ-specific ELISAs according to the manufacturer's directions.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc.). Comparisons between wild-type and mutant NCT was performed by two-way analysis of variance.

RESULTS

Glu-333 of NCT Directly Participates in γ-Secretase Activity

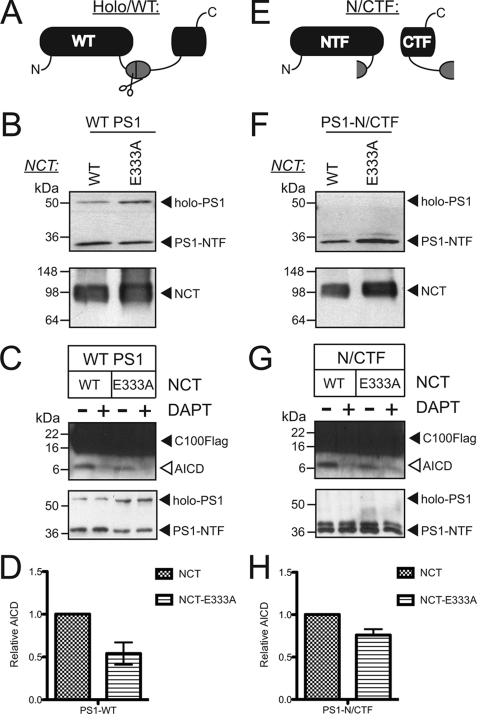

Earlier we found that NCT recruits substrates via Glu-333 (4); however, we and others have also obtained evidence that this same residue participates in maturation of the γ-secretase complex (17–19, 22). We, therefore, revisited our earlier model by testing whether Glu-333 of NCT directly participates in γ-secretase activity in proteolytically active enzyme that has already fully matured. To this end, we sought to examine the effects of Glu-333 of NCT in the context of either a normally formed γ-secretase complex (Fig. 1, A–D) or a “pre-matured” γ-secretase complex that bypasses PS endoproteolysis, the last step of γ-secretase maturation and activation (Fig. 1, E–H). To do so, we expressed either wild-type PS or a “pre-endoproteolyzed” form of PS (PS1-NTF/CTF) together with APH-1aL, PEN-2, and either wild-type NCT or the mutant NCT-E333A (Fig. 1A) using the baculovirus recombinant protein system that we and several other groups have shown effectively reconstitutes fully functional γ-secretase activity (4, 7, 9).

FIGURE 1.

Mutation of Glu-333 of NCT reduces AICD production independently of its role in γ-secretase maturation. A and E, shown are schematics of PS constructs used in this study. Incorporation of holo-PS1 (A) into γ-secretase complexes containing NCT, APH-1, and PEN-2 leads to its endoproteolysis within a hydrophobic domain (gray oval) in the large intracellular loop. Cleavage in this region (scissors) yields PS1-NTF and -CTF. Alternatively, a “pre-processed” form of PS may be expressed as PS1-NTF and -CTF individually (E). B and F, shown is the maturation of wild-type PS1- and PS1-NTF/CTF-containing γ-secretase complexes. γ-Secretase complexes reconstituted with APH-1aL, PEN-2, NCT-WT, or NCT-E333A plus either holo-PS1 (B) or PS1-NTF/CTF (F) as depicted in panel A or E were probed with antibodies that recognize the N terminus of PS1 and the extracellular domain of NCT. The blot for PS1-CTF is similar to that of PS1-NTF (data not shown). C and G, shown are the effects of the NCT-E333A mutant on generation of AICD in the context of γ-secretase complexes reconstituted with wild-type PS1 (C) and PS1-NTF/CTF (G). γ-Secretase complexes containing the indicated PS1 and NCT constructs along with APH-1aL and PEN-2 were subjected to in vitro γ-secretase cleavage assays using C100FLAG as a substrate. The resulting products were run on SDS-PAGE and blotted for the C terminus of APP or N terminus of PS1. Shown are representative immunoblots for the in vitro γ-secretase assays. D and H, γ-secretase product AICD from the assays in C and G was normalized to PS1-NTF. Data represent the mean ± S.E. of four independent experiments.

Complementing these reconstitution methods for obtaining mature γ-secretase, we utilized two normalizing methods for measuring the active pools of γ-secretase enzyme. First, we normalized activity to PS1-NTF to provide a proxy for the amount of mature γ-secretase complexes. More importantly, we developed a radioligand displacement assay using a 3H-labeled γ-secretase inhibitor to measure the number of active γ-secretase complexes in each preparation. This assay was critical to our analysis, as normalization of activity to the number of active γ-secretase complexes establishes a measure of the total amount of activity per active γ-secretase complex or the “intrinsic activity” of each γ-secretase complex. Using this assay we found that γ-secretase complexes containing either wild-type NCT or NCT-E333A had a similar number of binding sites whether in the context of wild-type or pre-endoproteolyzed PS1 (Table 1; differences between wild-type NCT and NCT-E333A within each PS form were not statistically significant). This result suggests that the E333A mutation in NCT does not affect the active site per se, as the number of active complexes per mg protein was equivalent in the wild-type and mutant NCT preparations, regardless of the PS1 form with which NCT was co-expressed. This is indeed an important observation, as it suggests that Glu-333 of NCT does not participate in structuring the enzyme active site.

TABLE 1.

Number of substrate binding sites in γ-secretase complexes

The number of binding sites, βmax, was determined using l-[3H]685,458, a potent γ-secretase transition state analog inhibitor as described under “Experimental Procedures.” βmax was determined from saturation binding isotherms. Data are presented as the pmol of substrate binding sites per mg of protein. No statistical difference was seen in βmax between NCT-WT or -E333A within a given PS1 background.

| PS1-WT |

PS1-NTF/CTF |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| NCT-WT | NCT-E333A | NCT-WT | NCT-E333A |

| 1.09 ± 0.07 | 0.98 ± 0.08 | 1.26 ± 0.06 | 1.1 ± 0.1 |

Having shown that the reconstituted γ-secretase complexes, including those containing PS1-NTF/CTF, provide sufficient active quantities of both wild-type and mutant enzymes, we next asked whether mutation of NCTs Glu-333 directly affects intrinsic enzymatic activity by measuring γ-secretase activity of Sf9 cell membranes expressing different γ-secretase complexes. We began by measuring by immunoblot the production of AICD from a synthetic C100FLAG substrate, which corresponds to the C-terminal FLAG-tagged product of APP cleavage by β-secretase (10). We normalized activity to PS1-NTF, which represents the amount of mature γ-secretase complexes. We found that wild-type PS1 γ-secretase complexes containing NCT-E333A showed a ∼50% reduction in intrinsic activity toward production of AICD when compared with its wild-type NCT counterpart (Fig. 1, C and D). Sensitivity of AICD production to DAPT, a γ-secretase inhibitor, demonstrates the specificity of this cleavage product. Furthermore, the γ-secretase complex expressing the “pre-cleaved” PS1-NTF/CTF together with NCT-E333A also shows a reduction in intrinsic activity compared with its wild-type NCT counterpart (Fig. 1, G and H). Thus, the E333A NCT mutant directly affects γ-secretase activity, independent of any effects it may have on γ-secretase complex maturation.

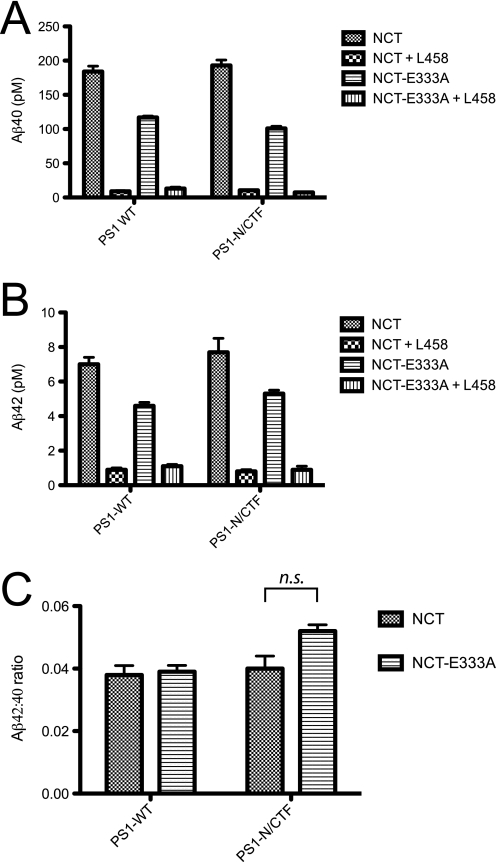

γ-Secretase cleavage of C100 results in two products: the C-terminal AICD and the N-terminal Aβ peptides. Aβ peptides can vary in their length, with the majority comprised of Aβ40 (∼90%) and the more toxic Aβ42 (1, 2). Having established that Glu-333 of NCT plays a direct role in AICD production, we next asked, using a second independent assay, whether this same residue participates in formation of Aβ40 and Aβ42 peptides. We again used baculovirus-infected Sf9 cell membranes and measured production of these two major Aβ peptides by ELISA, normalizing the data to the total number of binding sites, or βmax, by radioligand assay (Fig. 2). As described earlier, this normalization allows measurement of the intrinsic activity of each active γ-secretase complex. As seen in the production of AICD (Fig. 1), γ-secretase complexes containing wild-type PS1 and NCT-E333A again exhibited a reduction in the production of both Aβ40 and Aβ42 peptides when compared with their wild-type NCT counterparts (Figs. 2, A and B, respectively, left). Moreover, the reduction in activity was also seen in the context of pre-endoproteolyzed PS1-NTF/CTF-containing γ-secretase complexes (Figs. 2, A and B, right). Interestingly, the E333A mutation affected Aβ40 and Aβ42 production equally, as there was no significant difference in the Aβ42:Aβ40 ratio between wild-type NCT- and NCT-E333A-containing γ-secretase complexes (Fig. 2C).

FIGURE 2.

Mutation of Glu-333 of NCT reduces Aβ40 and Aβ42 production equally and does so independently of its role in γ-secretase maturation. Shown are the effects of NCT-E333A mutation on the in vitro production of Aβ40 (A), Aβ42 (B), and the Aβ42:40 ratio (C) in the context of wild-type PS1- and PS1-NTF/CTF-containing γ-secretase complexes. Complexes also contained APH-1aL, PEN-2, and either wild-type NCT or NCT-E333A. The indicated complexes were subjected to in vitro γ-secretase cleavage assays using C100FLAG as a substrate; the resulting Aβ peptides were measured by ELISA. Data were normalized to βmax values reported in Table 1. Two-way analysis of variance revealed no significant difference (n.s.) for interaction of NCT with PS1 forms.

NCT-E333A Is Deficient in Its Binding to γ-Secretase Substrates

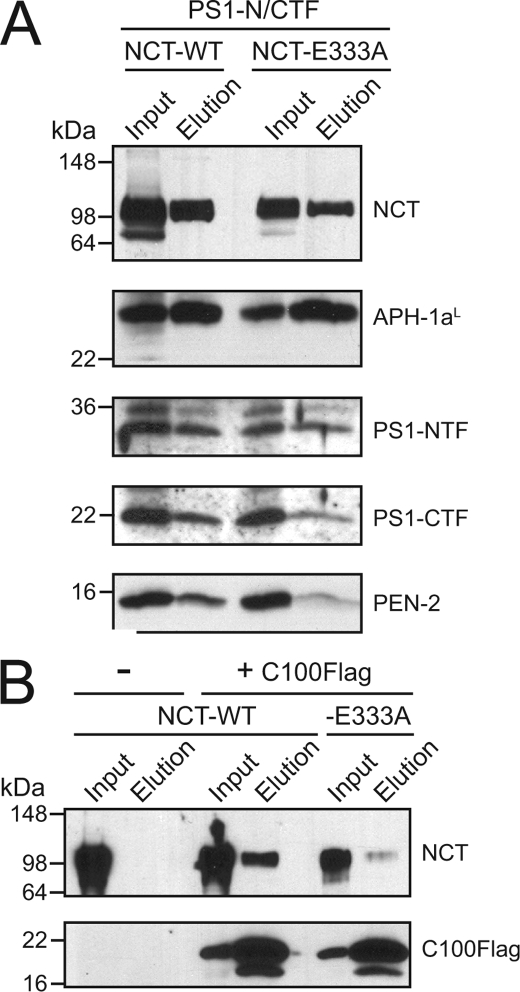

We previously established that, after ectodomain shedding, the newly generated free N termini of substrates are used for recruitment to the γ-secretase active site by NCT (4). Figs. 1 and 2 showed that NCT-E333A is deficient in γ-secretase activity, outside of the requirement for this residue in γ-secretase complex maturation. We next asked what part of the γ-secretase biochemistry was responsible for the reduction in activity. Data from Fig. 1 showed that in our experimental system, PS endoproteolysis and PS and NCT stability were preserved in γ-secretase complexes containing the NCT-E333A mutant. Therefore, we next asked whether the mutant NCT could efficiently incorporate into γ-secretase complexes with the remaining three components. For ease of detection, NCT and APH-1aL were fused with His6 tags at their C termini, and CHAPSO-solubilized Sf9 cell membrane extracts were subjected to pulldown assay using Ni-NTA beads. Pulldown of γ-secretase complexes containing PS1-NTF/CTF and either wild-type NCT or NCT-E333A demonstrated that both wild-type and mutant NCT can effectively pull down PS1-NTF. Intriguingly, NCT-E333A was slightly less efficient at pulling down PS1-CTF and PEN-2 despite retaining the ability to pull down PS1-NTF similar to wild-type NCT (Fig. 3A). Pulldown assays with full-length PS1 yielded similar results (data not shown). Thus, the complexes analyzed contain similar stoichiometries between the γ-secretase complex subunits.

FIGURE 3.

NCT-E333A efficiently incorporates into γ-secretase complexes but is deficient in its binding to C100FLAG substrate. A, shown is pulldown of γ-secretase components. γ-Secretase complexes containing C-terminal V5His6-tagged NCT and APH-1aL were pulled down on Ni-NTA-agarose and blotted for PS1-NTF, PS1-CTF, and HA-PEN-2. B, shown is pulldown of NCT with C100FLAG. C100FLAG was pulled down using FLAG-M2-agarose from Sf9 cells infected with baculovirus expressing C100FLAG and either wild-type NCT or NCT-E333A. The resulting precipitates were probed for the N terminus of NCT and the C terminus of APP (C100).

NCT shares distant homology with exopeptidases, and the analogous residue to Glu-333 in aminopeptidases participates in interactions with the N-terminal amine of substrates (4, 23). Therefore, we asked whether a direct interaction between NCT and γ-secretase substrates was impaired for the NCT-E333A mutant. To this end, we expressed the C100FLAG substrate in Sf9 cells with C-terminal His6-tagged wild-type or mutant NCT alone (i.e. without PS, APH-1, or PEN-2) and tested whether the interaction between NCT-E333A and C100FLAG was impaired relative to that with wild-type NCT. We used this same approach in our initial paper to show that NCT binds specifically and stoichiometrically to C100FLAG (4). Less NCT-E333A was pulled down with C100FLAG relative to wild-type NCT, revealing that NCT-E333A indeed has a lower affinity for C100FLAG than its wild-type counterpart (Fig. 3B). Moreover, the interaction between NCT and C100FLAG was mediated by the extracellular domain of NCT and not by the transmembrane domain, as C100FLAG equally pulled down NCT chimeras with their transmembrane domains swapped with that of E-selectin (data not shown and (4)). Thus, although NCT-E333A can incorporate relatively efficiently into γ-secretase complexes in the reconstitution systems, the major deficiency of NCT-E333A is its relative inability to bind to γ-secretase substrates, even outside of the context of the γ-secretase complex.

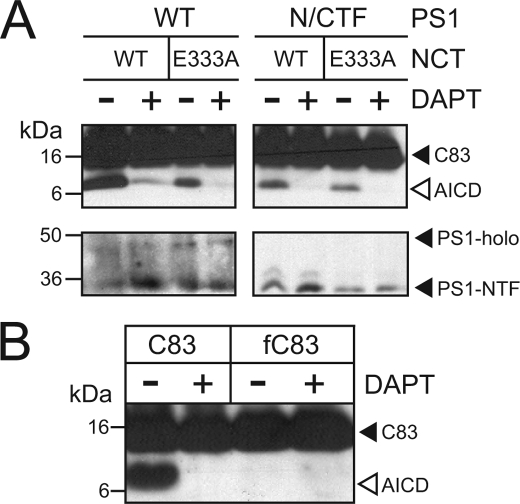

Glu-333 of NCT and a Free N Terminus Are Also Required for γ-Secretase Cleavage of C83, the Product of α-Secretase Cleavage of APP

Having demonstrated previously that C100 cleavage is dependent on Glu-333 of NCT and on C100 having a free N terminus (this report and Ref. 4), we investigated whether the C-terminal product of APP cleavage by α-secretase (C83) also shares these properties. Using the membranes of Sf9 cells infected with the four components of γ-secretase as above, we found that γ-secretase cleavage of C83FLAG, like C100FLAG, is dependent on Glu-333 of NCT (Fig. 4A). Moreover, like C100FLAG, formylation (a modification of only three atoms) of the N-terminal α-amino group of C83FLAG (fC83) results in the complete blocking of its cleavage by γ-secretase (Fig. 4B). These results show that, like C100, γ-secretase cleavage of C83 occurs via Glu-333 of NCT and requires a free N terminus on C83. Equally important, these results also show that mutation of Glu-333 of NCT to Ala results in a similar reduction in γ-secretase activity toward two different substrates.

FIGURE 4.

Like C100FLAG, cleavage of C83FLAG is also sensitive to the NCT-E333A mutant and also requires a free N terminus. A, shown are the effects of NCT-E333A mutation on the in vitro production of AICD from C83FLAG in the context of wild-type PS1- and PS1-NTF/CTF-containing γ-secretase complexes. Upper panel, activity assay probing for AICD; lower panel, normalization to PS1-NTF. B, formylation of the α-amino group of the N terminus of C83FLAG (fC83) eliminates its cleavage by γ-secretase. C83 and its N-terminal-formylated counterpart were subjected to in vitro γ-secretase cleavage assays. Analyses were conducted as in Fig. 1.

γ-Secretase Cleavage of APP-derived Substrates Requires a Free N Terminus of No Minimal Length

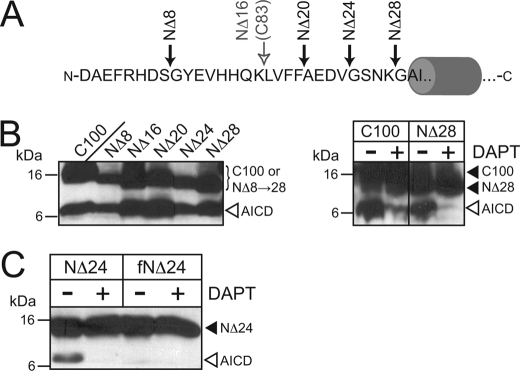

γ-Secretase substrates must first undergo ectodomain shedding to create an N terminus that is short enough to enter the γ-secretase complex (4, 24). Because the extracellular domain of NCT binds to substrates (Ref 4 and Fig. 3B), we reasoned that the extracellular N-terminal stub of γ-secretase substrates may provide determinants to allow for such an interaction. We have already shown that γ-secretase can cleave a C100 mutant in which the N-terminal seven amino acids have been replaced with the FLAG epitope (4). This, coupled with the wide variety of non-similar substrates suggests that γ-secretase lacks specific contacts with residues in the N terminus of substrates. Therefore, we focused on structural properties of the C100 substrate critical for its cleavage by γ-secretase.

Although Struhl and Adachi (24) determined a maximal length for the N termini of substrates for cleavage by γ-secretase, no study to date has attempted to find a minimal length for the N termini of γ-secretase substrates. Having established above that two naturally occurring APP-derived γ-secretase substrates require a free N terminus for their cleavage, we next attempted to find the minimal size, if any, for APP-derived γ-secretase substrates. To this end, we made several N-terminal deletions of C100FLAG, including NΔ16 (i.e. C83) and deletion of the entire extracellular N terminus (NΔ28, Fig. 5A). Surprisingly, each of these was a suitable substrate in in vitro γ-secretase assays (Fig. 5B). Moreover, α-amino formylation at the N terminus of each of these substrates prevented their cleavage by γ-secretase (Fig. 5C and data not shown).

FIGURE 5.

γ-Secretase cleavage of APP-derived substrates requires a free N terminus of no minimum size. A, shown are the N-terminal deletions of C100FLAG used in this study. The open gray arrow denotes NΔ16 (or C83), which is the natural product of α-secretase cleavage of APP. B, shown is in vitro cleavage of C100 the N-terminal truncations from panel A by γ-secretase. Left, shown are in vitro γ-secretase activity assays on N-terminal truncations. All truncations produce AICD of the same size (open arrowhead) despite variations in their total molecular weight (bracket). Right, in vitro γ-secretase activity assays demonstrate that cleavage of C100 and NΔ28 are sensitive to the γ-secretase inhibitor DAPT. C, like C100FLAG and C83FLAG, α-amino formylation of the N terminus of NΔ24 (fNΔ24) abrogates its cleavage by γ-secretase. Analyses were conducted as in Fig. 1.

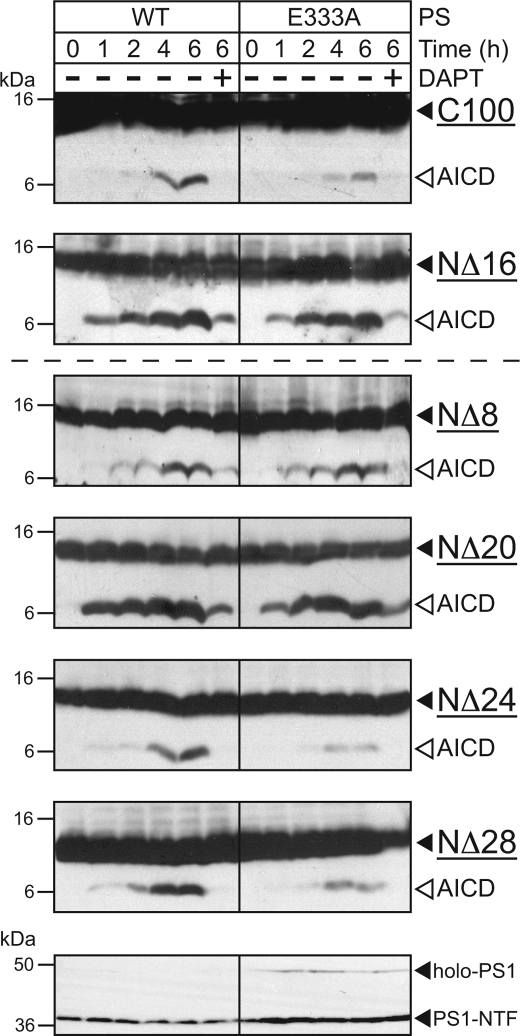

Having demonstrated that γ-secretase cleavage of both C100 and C83 are sensitive to the NCT-E333A mutant (Figs. 1, 2, and 4A) and that several N-terminal truncations of C100 can still serve as γ-secretase substrates (Fig. 5), we next asked whether any of these N-terminal truncations was also sensitive to the NCT-E333A mutant. The incomplete (∼25–50%) reduction of activity seen with long (overnight) incubation times of C99 and C83 (Figs. 1, 2, and 4A) prompted us to first ask whether shorter incubation times would reveal a larger difference in activity between wild-type NCT and NCT-E333A. As with overnight (12–24 h) incubation, incubation of C100 and C83 (NΔ16) with γ-secretase from 1 to 6 h revealed ∼25–50% reduction in activity with NCT-E333A-containing γ-secretase complexes at those time points in which products were detected (Fig. 6). Interestingly, we found that the N-terminal truncations NΔ24 and NΔ28 were particularly sensitive to the NCT-E333A mutant, whereas NΔ8, NΔ16, NΔ20 were less sensitive. Thus, mutation of Glu-333 of NCT to Ala affects γ-secretase cleavage of a variety of physiological and mutant APP-based substrates regardless of the sequence or length of their N-terminal stubs.

FIGURE 6.

APP N-terminal truncations are sensitive to the NCT-E333A mutant. The APP substrates assayed in Fig. 5 were subjected to in vitro γ-secretase activity assays using modified γ-secretase complexes containing wild-type PS1 and either wild-type NCT or NCT-E333A. Experiments were conducted over the course of 6 h, and at each time point the reaction was quenched with SDS sample loading buffer before loading on SDS-PAGE. The bottom panel shows a representative anti-PS1-NTF immunoblot for all six assays. Analyses were conducted as in Fig. 1.

DISCUSSION

γ-Secretase substrates are first pre-processed by an upstream protease to lose their bulky extracellular domain in a process called ectodomain shedding. Previously, we found that NCT, partly via Glu-333, functions as a γ-secretase substrate receptor by binding to the newly generated N terminus resulting from ectodomain shedding (4). However, a recent study challenged this model, arguing that although mutations of this residue impair γ-secretase activity, the main role of Glu-333 is in the maturation process of γ-secretase rather than directly in activity (17). We, therefore, revisited our earlier studies with refined experiments.

Here, we show that Glu-333 of NCT does, in fact, directly participate in activity. We measure the production of three γ-secretase products using two separate methods of γ-secretase reconstitution, two different modes of analysis (immunoblotting and ELISA), two different normalization methods (radioligand saturation binding and PS1-NTF levels), and normalizing to the amount of active enzymes to demonstrate that Glu-333 is indeed important in the proteolytic activity to generate Aβ40, Aβ42, and AICD from APP. Importantly, we also establish a novel radioligand saturation assay to sensitively and quantitatively measure the number of active γ-secretase complexes within a given assay. Such a method far exceeds comparable methods using immunoblotting and ECL in both its sensitivity and accuracy and provides a robust standard measurement against which one may compare activity across γ-secretase preparations, isoforms, and mutants.

The utilization of the pre-endoproteolyzed PS fragments (NTF/CTF) in γ-secretase reconstitution provided γ-secretase that bypasses the need for the PS endoproteolysis maturation step, which can otherwise complicate interpretation of the results. The γ-secretase complex undergoes a sophisticated series of events in its maturation. These include the preassembly of discreet subcomplexes from the four components, trafficking of the individual and subcomplexes through the ER and Golgi to the plasma membrane, binding of modulators such as Rer1p, complex glycosylation of NCT and its subsequent conformational change, and the endoproteolysis of PS within its large intracellular loop (10). To represent a pre-matured γ-secretase complex, we chose to use a mimic of PS endoproteolysis by co-expressing the individual fragments PS1-NTF and -CTF together with APH-1, PEN-2, and NCT. Pre-endoproteolyzed PS was chosen for the following reasons. (i) γ-Secretase activity only requires the assembly of the four main components (PS, NCT, APH-1, and PEN-2; Ref 10); (ii) activity does not require the complex glycosylation of NCT (25); (iii) most PS is found as its endoproteolyzed fragments in vivo (12); (iv) transition state analog inhibitors of γ-secretase bind to the PS fragments (26), and (v) expression of PS1-NTF and -CTF in cells and in vivo successfully reconstitutes γ-secretase activity (27, 28) We, too, show that expression of PS fragments form stable γ-secretase complexes with appropriate subunit stoichiometries and with the proper glycosylation and conformation of NCT. Moreover, radioligand saturation binding indicates similar numbers of γ-secretase active sites between holo-PS1- and PS1-NTF/CTF-containing complexes. Therefore, reconstitution with PS1-NTF and -CTF recapitulates the process of generating mature γ-secretase complexes. Moreover, regardless of whether all of the required maturation steps have been replicated in this system, it provides a way to obtain fully matured, active enzyme.

Using these tools, we show that NCT-E333A indeed displays a reduction in intrinsic γ-secretase activity toward several substrates, independent of its role in maturation. Furthermore, we find that the deficiency in activity mainly stems from the reduced ability of NCT-E333A to bind to γ-secretase substrates. However, we wish to emphasize that the effects of the NCT-E333A mutant on γ-secretase are not complete in the active enzyme. Thus, Glu-333 of NCT is important but not essential for γ-secretase activity, and other residues within the DAP domain most likely also contribute substantially to activity. Nevertheless, we find that within NCT, mutation of Glu-333 gives the largest reduction in γ-secretase activity (4). We also wish to point out that, although we demonstrate that Glu-333 of NCT directly participates in γ-secretase activity, we also acknowledge that Glu-333 of NCT participates in γ-secretase complex maturation. In γ-secretase reconstituted with wild-type PS1, PS endoproteolysis is moderately impaired by NCT-E333A (Figs. 1B and 6). Elsewhere, we and others have also shown that NCT-E333A mutant is partially defective in PS endoproteolysis (17, 19, 22). Thus, whereas we, too, find a role for Glu-333 of NCT in γ-secretase complex maturation or activation, our data clearly demonstrate that this residue also participates directly in γ-secretase activity in the mature and active enzyme.

A Model for Participation of Glu-333 of NCT in Both γ-Secretase Activity and Maturation

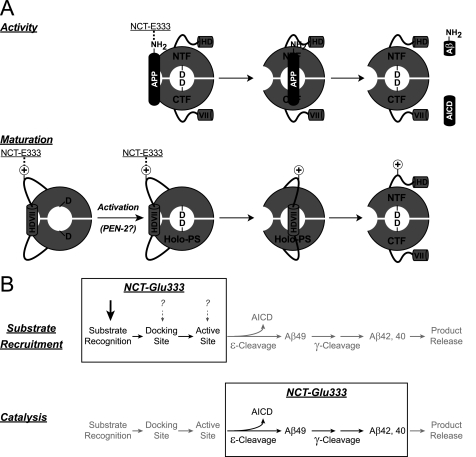

How can Glu-333 doubly participate in both γ-secretase maturation and activity? γ-Secretase substrates sit in the active site of γ-secretase, with their N termini toward the extracellular space (24, 29). However, γ-secretase also cleaves itself autocatalytically within the hydrophobic domain VII (HDVII) of PS in the large intracellular loop (11, 13). Therefore, HDVII must adopt a similar topology to substrates and in fact is the first substrate of γ-secretase. Indeed, a peptide representing HDVII can inhibit γ-secretase activity (30), and HDVII interacts closely with the γ-secretase active site (31). Therefore, our earlier report showing that NCT-E333A is deficient in activity predicts that PS endoproteolysis would also be affected (4). Therefore, our data support an “autoinhibitory model” whereby HDVII of PS occupies its own active site in cis (Fig. 7A). In this model Glu-333 interacts with HDVII during autoinhibition/assembly and with substrates during activity.

FIGURE 7.

Model for the dual role of Glu-333 of NCT in both γ-secretase activity and maturation. A, upper panel, substrates such as APP are recruited to the γ-secretase complex via interactions with Glu-333 of NCT. The interaction between NCT and substrates may be necessary for the initial recruitment and/or binding of substrates to the docking site. Substrates then enter the active site, where they are cleaved, thus resulting in the generation of Aβ peptides and the AICD in the case of APP. Lower panel, PS cleaves itself within HDVII in its intracellular loop. HDVII is, thus, a γ-secretase substrate and may, therefore, be recruited to γ-secretase and enter the active site in an analogous manner. Activation of the γ-secretase complex, perhaps though the binding of PEN-2, aligns the two catalytic aspartate residues, thus rendering the γ-secretase complex catalytically active. This allows HDVII to enter the active site, where it is cleaved autocatalytically to generate the PS N- and C-terminal fragments (PS-NTF and -CTF, respectively), thereby relieving autoinhibition (alternatively, HDVII sits in the active site awaiting activation of γ-secretase). Because the free N terminus of substrates is required for γ-secretase cleavage, an analogous functionality may exist on or near HDVII. Glu-333 participates in both γ-secretase activity and maturation and may, therefore, bridge to a full or partial positive charge functionality of both substrates and HDVII. B, shown are two possible models for the role of Glu-333 in γ-secretase activity. The mechanism of γ-secretase activity includes recognition of substrate, docking of substrate to the complex, movement into the active site, cleavage at the ϵ-site to generate AICD, cleavage at the γ-sites to generate Aβ42 and Aβ40, and ends with the release of products. Mutation of Glu-333 to Ala reduces production of AICD, Aβ42, and Aβ40 equally. Therefore, Glu-333 may participate in either of two processes; the recruitment or binding of substrate upstream of catalysis (upper panel) or directly in the catalysis of all three cleavage products (lower panel).

If HDVII occupies the γ-secretase active site without getting cleaved, then the complex must not be in an active conformation. Maturation of the complex then must trigger the rearrangement of the active site to render it catalytically active (Fig. 7A, lower panel). Indeed, recent data suggests that HDVII adopts distinct conformations with PS holoprotein and endoproteolyzed PS (31). γ-Secretase activation may include rearrangement of the PS catalytic aspartate residues upon binding of PEN-2 to the complex, which is concomitant with PS endoproteolysis (32–36). Once the active site has been established, HDVII is cleaved and vacates the active site to allow for entry of substrates. This model also explains the pathogenicity of the PS1 familial Alzheimer disease mutant PS1-ΔE9, in which HDVII is deleted (37); deletion of HDVII would be predicted to alleviate autoinhibition and, thus, render γ-secretase constitutively active. Furthermore, because PS is an endoplasmic reticulum calcium leak channel (38), occupation of the PS active site by HDVII may also regulate channel activity, analogous to the ball-and-chain model for the gating of potassium channels (39). Autoinhibition is common among proteases (40), and this model revisits the hypothesis that PS acts as a zymogen (13, 26, 41). Moreover, because γ-secretase requires a free N-terminal amine on its substrates, this model further suggests that an analogous functionality may dwell on or around HDVII.

Glu-333 of NCT Contributes Equally to ϵ- and γ-Secretase Activities; Mechanistic Details on γ-Secretase Catalysis

γ-Secretase sequentially cleaves C100 at multiple sites; initial cleavage at the ϵ-site releases the C-terminal AICD, and the resulting N-terminal Aβ49 peptide is further cleaved to yield Aβ42 and Aβ40, which compose the majority of Aβ species and are of particular relevance to the progression of Alzheimer disease (42, 43). Our data show that mutation of Glu-333 in NCT to Ala equally affects the production of AICD, Aβ42, and Aβ40. Thus, to exert its effects equally, NCT may either act upstream of catalysis (Fig. 7B, upper panel) or may participate equally in all of the proteolytic events (Fig. 7B, lower panel). We found that the loss in substrate binding with mutant NCT is greater than the loss in activity, suggesting that the identity of this residue may be more critical for the initial recruitment of substrates than it is for catalysis. Therefore, we favor the simpler (first) model in which NCT participates in a step (or steps) upstream of catalysis, which may include movement of substrate to the docking and/or active sites (44–46). However, we cannot rule out the possibility that the catalysis model, or both models together, may be true.

Glu-333 and the Structure of NCT

Bioinformatics approaches have shown that NCT shares a distant homology with exopeptidases and the transferrin receptor (23). The equivalent NCT-Glu-333 residue in aminopeptidases is located in the active site and forms a salt bridge with the N-terminal amine of substrates (47, 48). Interestingly, others and we have found that substitution of Glu-333 for Asp and Gln retains partial functionality, thus implying that this interaction may involve hydrogen bonding and need not be via a salt bridge (4, 17, 23). NCT may have retained its ability to interact with the N terminus of substrates via Glu-333 while losing other key residues critical for proteolytic activity (23). Similarly, there exist several inactive rhomboids, which are catalytically inactive proteases, yet retain chaperone or regulatory functions (49–51). Recent attempts to model a portion of the extracellular domain of NCT have highlighted several conserved residues presumably critical for binding of substrates and/or catalysis. However, mutation of these residues had only modest effects on γ-secretase activity (17). Although efforts to model NCT by homology are noble, the failure to use the resulting model to predict an experimental outcome calls into question the reliability of such a model. We, too, attempted homology modeling against a large panel of distant homologs with known structures, but our efforts failed to produce a model with high confidence (data not shown). Thus, to date we lack a reliable model for the structure of NCT with any predictive value.

NCT and the N Terminus of APP-based Substrates

γ-Secretase cleaves a wide array of Type 1 transmembrane proteins, with seemingly little or no sequence specificity (14, 29); rather, the only requirement is ectodomain shedding of their precursors, whereby the extracellular domain is removed to generate a short extracellular stub with a free N-terminal amine (4, 24). Recently, Li et al. (52) demonstrated that another intramembrane protease with inverted topology, RseP, which utilizes ectodomain shedding by the upstream protease DegS to generate a new C terminus of its substrate RseA, in turn requires an interaction between a PDZ domain of RseP and a small hydrophobic C-terminal-most amino acid of substrate (Val-148 in RseA) for cleavage. Interestingly, the RseP PDZ domain harbors a non-canonical binding pocket that could only accommodate a single terminal-most residue. This study, thus, provides a second example of a potentially general mechanism by which ectodomain-shed substrates are recognized by intramembrane proteases (53). Unlike RseP, however, γ-secretase appears to have no specificity for the identity for the N-terminal-most residue. Instead, we asked here whether there is a minimal length of the extracellular domain that is required for recognition by γ-secretase and/or Glu-333 of NCT. We found that deletion of the entire extracellular domain still allows for proteolysis by γ-secretase and that proteolysis of this substrate is sensitive to the NCT-E333A mutation. Likewise, a related intramembrane protease, SPPL2b, was found to cleave a substrate lacking the entire extracellular domain (54). Moreover, we found that a free N-terminal amine, regardless of the individual identity of the N-terminal-most residue, is important for its cleavage by γ-secretase even when the entire extracellular domain of the substrate has been removed. These two observations are particularly striking as they imply that if NCT directly interacts with the N-terminal amine of ectodomain-shed substrates, it can do so for a variety of substrates with a variety of lengths provided that such substrates have a free N-terminal amine. This also implies that NCT may bind close to the lipid bilayer so as to form a cap over the active core in a manner strangely reminiscent of the proteasome (a speculation compatible with available ultrastructural data (55)). Moreover, because Glu-333 of NCT may also bridge to HDVII of PS to position this region within the γ-secretase active site (Fig. 7A), the NCT extracellular domain must be very close to the membrane to do so. Although other sequences in the NCT ectodomain almost certainly play structural and functional roles during the substrate recruitment process, Glu-333 may be a main NCT residue that guides the free N-terminal amine to the active site. The interaction between Glu-333 and the N-terminal amine conceivably is rather weak. This, however, is compensated by the high local concentration of the membrane-anchored NCT and substrate in the two-dimensional membrane environment.

In addition to substrate lacking the entire extracellular domain, Aβ49, which lacks the entire intracellular domain, is also a γ-secretase substrate (Ref. 56 and data not shown). Moreover, a small fluorescent peptide can enter the active site of γ-secretase for cleavage and bypass the requirement of Glu-333 of NCT for its cleavage (4). Together, these data agree with structural analyses which demonstrate that related intramembrane proteases utilize lateral gating through their transmembrane domains to allow substrates to gain access to the active site (21, 57, 58). Because we hypothesize that NCT participates in activity upstream of catalysis (Fig. 7B, upper panel), it is tempting to speculate that NCT participates in the recruitment of substrates, whereas lateral gating, independent of NCT, is required for entry of substrates into the γ-secretase active site. We hope that the models presented here provide new avenues for investigation into the unique biochemistry and enzymology of γ-secretase. Moreover, we hope that future cellular, biochemical, biophysical, and structural studies will clarify the mechanistic detail and the cellular and molecular logic of the dual function of NCT in γ-secretase complex maturation and substrate recognition.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants F32 AG031625 (to D. R. D.), R01 AG023104, and R01 AG029547. This work was also supported by the Welch Foundation (I-1566) and the Ted Nash Long Life Foundation.

- Aβ

- β-amyloid peptide

- AICD

- APP intracellular domain

- APP

- amyloid precursor protein

- C100

- the C-terminal 100 residues of APP

- C83

- the C-terminal 83 residues of APP

- DAPT

- N-[N-(3,5-difluorophenacetyl)-l-alanyl]-S-phenylglycine t-butyl ester

- NCT

- nicastrin

- PS

- presenilin

- CTF

- C-terminal fragment

- NTF

- N-terminal fragment

- Ni-NTA

- nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid

- HDVII

- hydrophobic domain VII

- CHAPSO

- 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-2-hydroxy-1-propanesulfonic acid

- WT

- wild type

- ELISA

- enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- HA

- hemagglutinin.

REFERENCES

- 1.Haass C., Selkoe D. J. (2007) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 101–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walsh D. M., Selkoe D. J. (2007) J. Neurochem. 101, 1172–1184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steiner H. (2008) Curr. Alzheimer Res. 5, 147–157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shah S., Lee S. F., Tabuchi K., Hao Y. H., Yu C., LaPlant Q., Ball H., Dann C. E., 3rd, Südhof T., Yu G. (2005) Cell 122, 435–447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Edbauer D., Winkler E., Regula J. T., Pesold B., Steiner H., Haass C. (2003) Nat. Cell Biol. 5, 486–488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fraering P. C., Ye W., Strub J. M., Dolios G., LaVoie M. J., Ostaszewski B. L., van Dorsselaer A., Wang R., Selkoe D. J., Wolfe M. S. (2004) Biochemistry 43, 9774–9789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hayashi I., Urano Y., Fukuda R., Isoo N., Kodama T., Hamakubo T., Tomita T., Iwatsubo T. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 38040–38046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kimberly W. T., LaVoie M. J., Ostaszewski B. L., Ye W., Wolfe M. S., Selkoe D. J. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 6382–6387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang L., Lee J., Song L., Sun X., Shen J., Terracina G., Parker E. M. (2005) Biochemistry 44, 4450–4457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dries D. R., Yu G. (2008) Curr. Alzheimer Res. 5, 132–146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brunkan A. L., Martinez M., Walker E. S., Goate A. M. (2005) Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 29, 65–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thinakaran G., Borchelt D. R., Lee M. K., Slunt H. H., Spitzer L., Kim G., Ratovitsky T., Davenport F., Nordstedt C., Seeger M., Hardy J., Levey A. I., Gandy S. E., Jenkins N. A., Copeland N. G., Price D. L., Sisodia S. S. (1996) Neuron 17, 181–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wolfe M. S., Xia W., Ostaszewski B. L., Diehl T. S., Kimberly W. T., Selkoe D. J. (1999) Nature 398, 513–517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nyborg A. C., Ladd T. B., Zwizinski C. W., Lah J. J., Golde T. E. (2006) Mol. Neurodegener. 1, 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wolfe M. S., Kopan R. (2004) Science 305, 1119–1123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beel A. J., Sanders C. R. (2008) Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 65, 1311–1334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chávez-Gutiérrez L., Tolia A., Maes E., Li T., Wong P. C., de Strooper B. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 20096–20105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen F., Yu G., Arawaka S., Nishimura M., Kawarai T., Yu H., Tandon A., Supala A., Song Y. Q., Rogaeva E., Milman P., Sato C., Yu C., Janus C., Lee J., Song L., Zhang L., Fraser P. E., St George-Hyslop P. H. (2001) Nat. Cell Biol. 3, 751–754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu G., Nishimura M., Arawaka S., Levitan D., Zhang L., Tandon A., Song Y. Q., Rogaeva E., Chen F., Kawarai T., Supala A., Levesque L., Yu H., Yang D. S., Holmes E., Milman P., Liang Y., Zhang D. M., Xu D. H., Sato C., Rogaev E., Smith M., Janus C., Zhang Y., Aebersold R., Farrer L. S., Sorbi S., Bruni A., Fraser P., St George-Hyslop P. (2000) Nature 407, 48–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clarke E. E., Churcher I., Ellis S., Wrigley J. D., Lewis H. D., Harrison T., Shearman M. S., Beher D. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 31279–31289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang Y., Zhang Y., Ha Y. (2006) Nature 444, 179–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shirotani K., Edbauer D., Kostka M., Steiner H., Haass C. (2004) J. Neurochem. 89, 1520–1527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fagan R., Swindells M., Overington J., Weir M. (2001) Trends Biochem. Sci. 26, 213–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Struhl G., Adachi A. (2000) Mol. Cell 6, 625–636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Herreman A., Van Gassen G., Bentahir M., Nyabi O., Craessaerts K., Mueller U., Annaert W., De Strooper B. (2003) J. Cell Sci. 116, 1127–1136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li Y. M., Xu M., Lai M. T., Huang Q., Castro J. L., DiMuzio-Mower J., Harrison T., Lellis C., Nadin A., Neduvelil J. G., Register R. B., Sardana M. K., Shearman M. S., Smith A. L., Shi X. P., Yin K. C., Shafer J. A., Gardell S. J. (2000) Nature 405, 689–694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laudon H., Mathews P. M., Karlström H., Bergman A., Farmery M. R., Nixon R. A., Winblad B., Gandy S. E., Lendahl U., Lundkvist J., Näslund J. (2004) J. Neurochem. 89, 44–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Levitan D., Lee J., Song L., Manning R., Wong G., Parker E., Zhang L. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 12186–12190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kopan R., Ilagan M. X. (2004) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 5, 499–504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Knappenberger K. S., Tian G., Ye X., Sobotka-Briner C., Ghanekar S. V., Greenberg B. D., Scott C. W. (2004) Biochemistry 43, 6208–6218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tolia A., Horré K., De Strooper B. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 19793–19803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Capell A., Beher D., Prokop S., Steiner H., Kaether C., Shearman M. S., Haass C. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 6471–6478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shiraishi H., Sai X., Wang H. Q., Maeda Y., Kurono Y., Nishimura M., Yanagisawa K., Komano H. (2004) J. Neurochem. 90, 1402–1413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim S. H., Yin Y. I., Li Y. M., Sisodia S. S. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 48615–48619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Luo W. J., Wang H., Li H., Kim B. S., Shah S., Lee H. J., Thinakaran G., Kim T. W., Yu G., Xu H. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 7850–7854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Takasugi N., Tomita T., Hayashi I., Tsuruoka M., Niimura M., Takahashi Y., Thinakaran G., Iwatsubo T. (2003) Nature 422, 438–441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Perez-Tur J., Froelich S., Prihar G., Crook R., Baker M., Duff K., Wragg M., Busfield F., Lendon C., Clark R. F. (1995) Neuroreport 7, 297–301 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tu H., Nelson O., Bezprozvanny A., Wang Z., Lee S. F., Hao Y. H., Serneels L., De Strooper B., Yu G., Bezprozvanny I. (2006) Cell 126, 981–993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Armstrong C. M., Bezanilla F. (1977) J. Gen. Physiol. 70, 567–590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Khan A. R., James M. N. (1998) Protein Sci. 7, 815–836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yu G., Chen F., Nishimura M., Steiner H., Tandon A., Kawarai T., Arawaka S., Supala A., Song Y. Q., Rogaeva E., Holmes E., Zhang D. M., Milman P., Fraser P. E., Haass C., George-Hyslop P. S. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 27348–27353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhao G., Tan J., Mao G., Cui M. Z., Xu X. (2007) J. Neurochem. 100, 1234–1246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Qi-Takahara Y., Morishima-Kawashima M., Tanimura Y., Dolios G., Hirotani N., Horikoshi Y., Kametani F., Maeda M., Saido T. C., Wang R., Ihara Y. (2005) J. Neurosci. 25, 436–445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Das C., Berezovska O., Diehl T. S., Genet C., Buldyrev I., Tsai J. Y., Hyman B. T., Wolfe M. S. (2003) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 11794–11795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kornilova A. Y., Bihel F., Das C., Wolfe M. S. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 3230–3235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wolfe M. S. (2006) Biochemistry 45, 7931–7939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Luciani N., Marie-Claire C., Ruffet E., Beaumont A., Roques B. P., Fournié-Zaluski M. C. (1998) Biochemistry 37, 686–692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vazeux G., Iturrioz X., Corvol P., Llorens-Cortes C. (1998) Biochem. J. 334, 407–413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lemberg M. K., Freeman M. (2007) Genome Res. 17, 1634–1646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hulko M., Lupas A. N., Martin J. (2007) Protein Sci. 16, 644–653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Spiess C., Beil A., Ehrmann M. (1999) Cell 97, 339–347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li X., Wang B., Feng L., Kang H., Qi Y., Wang J., Shi Y. (2009) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 14837–14842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dries D. R., Yu G. (2009) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 14737–14738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Martin L., Fluhrer R., Haass C. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 5662–5670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lazarov V. K., Fraering P. C., Ye W., Wolfe M. S., Selkoe D. J., Li H. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 6889–6894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Funamoto S., Morishima-Kawashima M., Tanimura Y., Hirotani N., Saido T. C., Ihara Y. (2004) Biochemistry 43, 13532–13540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Feng L., Yan H., Wu Z., Yan N., Wang Z., Jeffrey P. D., Shi Y. (2007) Science 318, 1608–1612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wu Z., Yan N., Feng L., Oberstein A., Yan H., Baker R. P., Gu L., Jeffrey P. D., Urban S., Shi Y. (2006) Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 13, 1084–1091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]