Abstract

Stresses that perturb the folding of nascent endoplasmic reticulum (ER) proteins activate the ER stress response. Upon ER stress, ER-associated ATF6 is cleaved; the resulting active cytosolic fragment of ATF6 translocates to the nucleus, binds to ER stress response elements (ERSEs), and induces genes, including the ER-targeted chaperone, GRP78. Recent studies showed that nutrient and oxygen starvation during tissue ischemia induce certain ER stress response genes, including GRP78; however, the role of ATF6 in mediating this induction has not been examined. In the current study, simulating ischemia (sI) in a primary cardiac myocyte model system caused a reduction in the level of ER-associated ATF6 with a coordinate increase of ATF6 in nuclear fractions. An ERSE in the GRP78 gene not previously shown to be required for induction by other ER stresses was found to bind ATF6 and to be critical for maximal ischemia-mediated GRP78 promoter induction. Activation of ATF6 and the GRP78 promoter, as well as grp78 mRNA accumulation during sI, were reversed upon simulated reperfusion (sI/R). Moreover, dominant-negative ATF6, or ATF6-targeted miRNA blocked sI-mediated grp78 induction, and the latter increased cardiac myocyte death upon simulated reperfusion, demonstrating critical roles for endogenous ATF6 in ischemia-mediated ER stress activation and cell survival. This is the first study to show that ATF6 is activated by ischemia but inactivated upon reperfusion, suggesting that it may play a role in the induction of ER stress response genes during ischemia that could have a preconditioning effect on cell survival during reperfusion.

Stresses that alter the endoplasmic reticulum (ER)4 environment by impairing nascent ER protein glycosylation, disulfide bond formation, or calcium levels interfere with protein folding in this organelle, activating the ER stress response (1–5). Three ER-transmembrane signaling proteins serve as major proximal sensors of the ER stress response: IRE-1 (inositol-requiring protein-1), PERK (protein kinase RNA-like ER kinase), and ATF6 (activating transcription factor 6) (6, 7). When activated, these sensors initially lead to increased expression of ER-targeted chaperones, calcium-binding proteins, and disulfide isomerases as well as many proteins targeted to other cellular locations, which collaborate to enhance nascent ER protein folding capacity (8). ER stress also activates a transient translational repression of most transcripts that are not encoded by ER stress response genes; this repression is thought to conserve energy and reduce demands on the ER protein folding machinery (9). Additionally, ER stress augments the ER-associated protein degradation system, leading to proteasome-mediated degradation of terminally misfolded ER proteins, which helps relieve ER stress (10). Furthermore, under some conditions, ER stress activates autophagy (11, 12), a catabolic program that can promote cell survival (13). If activation of these survival-oriented pathways is insufficient to resolve the stress, continued ER stress can lead to apoptotic or necrotic cell death (14–18). Thus, depending on its strength and duration, ER stress can be survival- or death-oriented.

Compromises in blood supply, which are a common result of atherosclerosis, lead to combined stresses of hypoglycemia and hypoxia in numerous tissues, creating a potentially damaging ischemic condition. Although tissue damage occurs during ischemia, the generation of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species upon re-establishment of blood flow (i.e. reperfusion) is potentially even more damaging. Since nascent protein disulfide bond formation in the ER requires oxygen (19), it is possible that ER stress is activated during ischemia and that its effects might be exerted during ischemia and/or reperfusion. Consistent with this hypothesis are recent studies showing that simulating ischemia induces certain aspects of ER stress in several cell and tissue types (5). For example, simulated ischemia in cultured rat cardiac myocytes induced numerous ER stress response genes, including GRP78, an ER-resident chaperone that is known to be cardioprotective (20–23). The ER stress response was also activated during ischemia in an ex vivo mouse heart model of ischemia/reperfusion (24) and in an in vivo mouse model of myocardial infarction (20, 25). Additionally, studies using a novel transgenic mouse model have shown that ATF6 activation before ischemia has a preconditioning effect and protects the heart from ischemia/reperfusion damage (24). This finding suggests that the ATF6 branch of the ER stress response may have protective effects during ischemia and/or reperfusion; however, no studies to date have addressed whether ischemia activates ATF6 and, if so, whether ATF6 is required for subsequent ER stress response gene induction.

ATF6 is a 670-amino acid ER transmembrane protein that is cleaved during ER stress. The resulting N-terminal fragment of ATF6 translocates to the nucleus, where it binds to several types of regulatory sequences in target genes, such as ER stress elements (ERSEs), and activates ER stress response gene transcription (7, 10, 14, 26–37). A microarray study in the mouse heart showed that upon activation, ATF6 induced nearly 400 genes (38), supporting the hypothesis that ATF6 is a central regulator of numerous ER stress response genes, many of which may serve protective roles. The current study was undertaken to examine roles for ATF6 in ischemia-mediated ER stress gene induction of a prototypical ER stress response gene, GRP78, in a cultured cardiac myocyte model system of simulated ischemia/reperfusion.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Culture

Primary neonatal rat ventricular myocyte cultures were prepared and maintained as described previously (20). Cultures were subjected to conditions simulating ischemia (sI) or simulated ischemia followed by reperfusion (sI/R), essentially as described previously (39). Briefly, for sI, the medium was replaced with glucose-free Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium/F-12 containing 2% dialyzed fetal bovine serum, and cultures were placed in a gas-tight chamber outfitted with a BioSpherix PROOX model 110 controller, which was used to set the [O2] to 0.1%. For sI/R, following sI, the medium was replaced with glucose-containing Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium/F-12 supplemented with 2% fetal bovine serum albumin, and cultures were placed in an incubator at ∼20–21% O2.

Transfection and Reporter Assays

Constructs composed of nucleotides −284 to +221, or −284 to +7 of the human GRP78 promoter or −800 to +105 of the human GRP94 promoter driving luciferase were prepared using standard PCR and cloning approaches. Cultured cardiac myocytes were co-transfected with one of these reporter constructs or with pGL2p (control-luciferase) along with plasmids encoding SV40-β-galactosidase (pCH110; Amersham Biosciences), as described previously (20). Cultures were then plated, and after various treatments, cell extracts were assayed for β-galactosidase and luciferase activities, as previously described (20).

Adenovirus Preparation and Infection

The preparation of a recombinant adenovirus expressing a dominant-negative form of ATF6, AdV-dnATF6, was created using the AdEasy system, as previously described (20). AdV encoding rat ATF6-targeted miRNA was also generated using the AdEasy system.

Immunoblotting

Immunoblotting for ATF6β was carried out as previously described (40). For HIF-1α, 12 μg of cultured cell lysates were fractionated on 12% BisTris CriterionTM precast gels from Bio-Rad (catalog number 345-0117). Gels were then transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes, which were blotted with mouse monoclonal HIF-1α antibody raised against amino acids 432–628 of human HIF-1α from Novus Biologicals (catalog number NB100-105) used at a dilution of 1:100.

Small Interfering RNAs

Cultured cardiac myocytes plated at a density of 8 × 106 cells/60-mm plate (no coating) were transfected with siRNA oligoribonucleotides targeted against rat ATF6α (catalogue number 130003; Invitrogen) or a validated StealthTM RNA interference negative control (catalogue number 12935300; Invitrogen). Each well was incubated for 5 h with 10 pmol of each Stealth siRNA using TransMessengerTM transfection reagent (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), as described previously (38). The cells were then washed off the plates and replated at a density of 0.7 × 106 cells/well on fibronectin-coated 6-well plates. Transfected cultures were then maintained for 24 h in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium/F-12 with 10% fetal calf serum, followed by 24 h in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium/F-12 with 2% fetal calf serum, after which they were subjected to various treatments.

MicroRNAs

Recombinant adenovirus encoding either miRNA targeted to ATF6α, (miATF6) or a negative control (miCon) were created using the Gateway System from Invitrogen. The hairpin sequences to ATF6α (gttgtttgctgagcttggcta; catggactgactccaaagaaa) were generated using Invitrogen's online miRNA designer and ATF6α cDNA (GenBankTM accession number XM_001076843). The negative control sequence (gtctccacgcgcattacattt) was provided by Invitrogen and is not targeted toward any known gene. These oligonucleotides were expressed in pcDNA 6.2GW/EmGFP-miR using the Block-It Pol II miR expression kit from Invitrogen (catalog number K4936-00). The clones were first recombined into the Gateway pDONR vector, pDONR/Zeo (catalog number 12535-035) and then into the final adenoviral construct pAd/CMV/V5Dest (catalog number K4930-00).

Real Time Quantitative PCR

Real time quantitative PCR was performed as previously described (24). Primers were as follows: grp78, forward (CCACCTCAGTCTCCCAGCTAA) and reverse (GCCGAGCATGGTGGTAACA); pgk, forward (TTGGACAAGCTGGACGTGAA) and reverse (CAGCAGCCTTGATCCTTTGGT); atf6α, forward (TGCAGGTGTATTACGCTTCGC) and reverse (GCAGGTGATCCCTTCGAAATG).

Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assays (EMSAs)

EMSAs were carried out essentially as described previously (23). Briefly, double-stranded synthetic oligonucleotides designed to mimic the human GRP78 ERSE 2 and a mutant form of this ERSE (see below) were used as 32P-labeled probes or unlabeled competitors, as described in the figure legends (ERSE nucleotides are underlined): ccgggGTGGCCTGGGCCAATGAACGGCCTCCAACGAGCAGGGCCc (ERSE 2) and ccgggGTGGCCTGGGCtcgaGAACGGCCTaacacGAGCAGGGCCc (ERSE 2 mutant).

Nuclear extracts, which provide the source of other proteins (e.g. NF-Y, YY1, and TFII-I) needed for ATF6 binding to ERSEs, were prepared as described previously (23). Binding reactions were carried out in 20 mm HEPES (pH 7.9), 10% glycerol, 1 mm MgCl2, 1 mm 2-mercaptoethanol, 0.1% Tween 20, 0.2 μg of poly(dI-dC), 6 μg of cultured cardiac myocyte nuclear extract, 2 μl of in vitro translated ATF6α-(1–373), prepared as previously described (23), and 10,000 cpm of 32P-labeled probe. Reactions were incubated at room temperature for 20 min and then fractionated on a 5% polyacrylamide gel at 200 V for 150 min in 0.5× TBE buffer (45 mm Tris borate, 1 mm EDTA). For supershift EMSAs, 1 μl of anti-ATF6α (catalog number sc-22799; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA) or 1 μl of non-immune mouse antisera were added 15 min prior to probe addition. For oligonucleotide specificity assessment, a 10- or 50-fold excess of unlabeled double-stranded oligonucleotide was added 15 min prior to the addition of probe.

Cell Death Assay

Cultured cardiac myocytes were plated at 0.5 × 106 cells/60-mm fibronectin-coated culture dish and subjected to simulated ischemia and reperfusion, as previously described. Cells were then assessed for death by morphologic observation using epifluorescence microscopy and staining with 1.5 mm propidium iodide, which is not taken up by living cells. The total number of cells was measured using Hoechst catalog number 33358 (5 μg/ml), which stains the nucleus of all cells. Between 100 and 200 cells/culture were scored from 3–5 random fields; n = 3 cultures/treatment. Experiments were repeated three times, and the compiled data are shown.

ERSE Mutations

Using PCR-based mutagenesis (QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit, Stratagene catalogue number 200518), ERSE 1, ERSE 2, and ERSE 3 in the region from −284 to +221 of the human GRP78 gene in the luciferase reporter construct were changed to GATCTN9AACAT, CTCGAN9AACAC, GAGCTN9AACGC, respectively, using the following forward PCR primers and complementary reverse primers: ERSE 1, GAGCAGGGCCTTCAgatcTCGGCGGCCTaacatACGGGGCTGGGGGAG; ERSE 2, GGTGGCCTGGGCtcgaGAACGGCCTaacacGAGCAGGGCCTTC; ERSE 3, CGGAGGGGGCCGCTTgagcTCGGCGGCGGaacgcTTGGTGGCCTGGG. The ERSEs are underlined, and the sites that were mutated and the nucleotides to which they were changed are depicted in lowercase type.

Replicates and Statistical Analysis

Unless otherwise stated in the figure legends, each treatment was performed on three identical cultures. Statistical analyses were performed using a one-way analysis of variance followed by Student's Newman-Keul's post hoc analysis of variance (*, #, §, &, and ⊗, p < 0.05 different from control and all other values, unless otherwise stated in the figure legends).

RESULTS

Effects of Simulated Ischemia/Reperfusion on Induction of GRP78

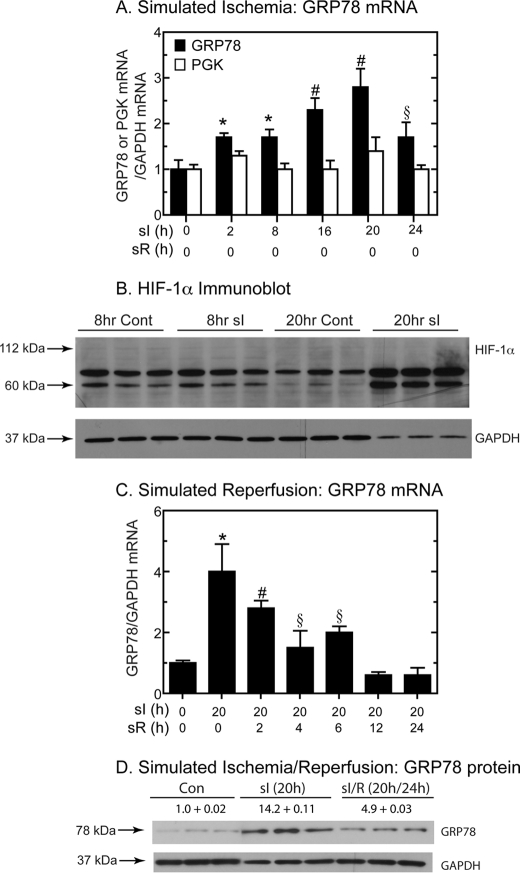

To determine the effects of ischemia on grp78 induction, cultured rat cardiac myocytes were subjected to sI conditions (i.e. glucose and oxygen deprivation (no glucose, 0.1% O2)), as described previously (20, 38, 41). Upon sI, rat grp78 mRNA progressively increased with time, attaining a maximum after 20 h of sI (Fig. 1A, black bars).

FIGURE 1.

Effect of sI/R on grp78 mRNA and protein, pgk mRNA, and HIF-1α protein. A, cultured cardiac myocytes were subjected to sI for the times shown. The levels of rat grp78, pgk, and gapdh (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) mRNA were assessed by reverse transcription quantitative PCR. Shown are the mean values of grp78 or pgk/gapdh mRNA expressed as -fold control level (control = 0 h sI/0 h sR) ± S.E. *, #, and §, p ≤ 0.05 different from control and all other values. B, cultured cardiac myocytes were treated with or without sI for 8 or 20 h, and then extracts were examined for rat HIF-1α and GAPDH by immunoblotting. The migration positions of 112-, 60-, and 37-kDa molecular mass markers are shown, as is the approximate expected migration position for full-length HIF-1α (n = 3 cultures/treatment). C, cultured cardiac myocytes were subjected to 20 h of sI/R for the times shown. The levels of rat grp78 and gapdh mRNA were assessed by reverse transcription quantitative PCR. Shown are the mean values of grp78/gapdh mRNA expressed as -fold control (control = 0 h sI/0 h sR) ± S.E. *, #, and §, p ≤ 0.05 different from control and all other values. D, cultured cardiac myocytes were subjected to sI or sI/R for the times shown. The levels of rat GRP78 and GAPDH were determined by immunoblotting (n = 3 cultures/treatment). The GRP78 levels were normalized to GAPDH and are shown as -fold control ± S.E.

Under certain conditions, oxygen deprivation can activate HIF-1α; accordingly, the effect of sI on expression of a well known HIF-1α-inducible gene, pgk (phosphoglycerate kinase) (42), was examined. In contrast to grp78, rat pgk mRNA did not change during any of the sI times (Fig. 1A, white bars), suggesting that HIF-1α was not activated under these conditions. When HIF-1α activation was examined by immunoblotting, there was no evidence of HIF-1α accumulation when cultured cells were subjected to 8 or 20 h of sI (Fig. 1B). This absence of HIF-1α activation is consistent with previous studies showing that HIF-1α activation is maximal at 0.5% oxygen but decreases to nearly basal levels at lower oxygen concentrations (43), including 0.1% oxygen, which was used in the current study. It was of interest that the intensities of two HIF-1α cross-reactive bands, migrating at 60 and ∼75 kDa, increased after 20 h of sI (Fig. 1B). Previous studies have shown that these bands are HIF-1α variants that are endogenous inhibitors of HIF-1α-mediated gene induction (44, 45). Taken together, the results shown in Fig. 1, A and B, suggest that sI induced grp78 in a HIF-1α-independent manner, consistent with the possibility that grp78 induction may be mediated in part by ER stress.

The effects of simulated reperfusion on rat grp78 gene induction in cultured cardiac myocytes were also examined. In contrast to sI alone, when cells were subjected to 20 h of sI followed by various times of simulated reperfusion (sI/R) there was a steady decline of rat grp78 mRNA, which began as soon as 2 h of reperfusion and returned to basal levels after 12 h (Fig. 1C). The effects of sI and sI/R on rat Grp78 protein were examined by immunoblotting. In cells subjected to sI, Grp78 increased to 14-fold control level, which decreased to about 5-fold control upon sI/R (Fig. 1D).

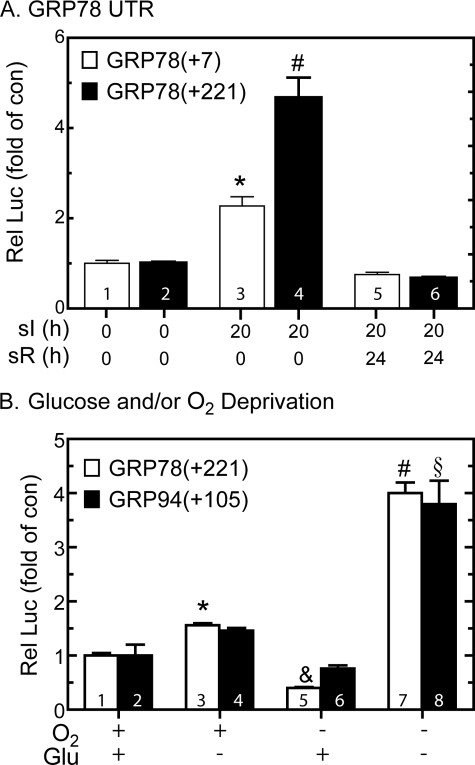

To examine whether transcriptional activation was responsible for ischemia-mediated increases in rat grp78 mRNA, we determined the effects of sI and sI/R on expression of a human GRP78 promoter-driven reporter, which serves as an indirect measure of GRP78 transcription. Previous studies showed that reporter constructs composed of nucleotides −304 to +7 of the human GRP78 gene contain three ERSEs, with the promoter-proximal ERSE, ERSE 1, being necessary for reporter induction by tunicamycin (TM) in HeLa cells (27). In the present study, sI activated reporter expression from GRP78(+7)-Luc5 to about 2-fold control; this activation declined to basal levels upon sI/R (Fig. 2A, bars 1, 3, and 5). This activation was relatively low compared with that observed with TM (∼10-fold; not shown), perhaps, in part, because during sI, hypoxia drives cellular ATP to very low levels, decreasing protein synthesis, thereby decreasing reporter expression. Accordingly, we redesigned the reporter construct to optimize luciferase expression under such conditions. GRP78(+7)-Luc does not contain the internal ribosomal entry site, which has been shown to be required for the GRP78 mRNA to escape ER stress-mediated translational repression (46). Therefore, we generated a construct that encoded the entire 221-nucleotide 5′-UTR of the human GRP78 mRNA, GRP78(+221)-Luc6; the internal ribosomal entry site is located between +7 and +221 (47). Using this reporter, sI increased luciferase expression to about 5-fold control (Fig. 2A, bars 2 and 4). As was observed with GRP78(+7)-Luc, promoter activation from GRP78(+221)-Luc decreased upon sR (Fig. 2A, bar 6). Thus, compared with GRP78(+7)-Luc, GRP78(+221)-Luc exhibited a greater range of induction by sI; therefore, it was used for the remainder of the experiments in this study that required the GRP78 promoter.

FIGURE 2.

Effect of oxygen and/or glucose deprivation on GRP78- and GRP94-luciferase. A, cultured cardiac myocytes were transfected with human GRP78(+7)-Luc (GRP78(+7)) or human GRP78(+221)-Luc (GRP78(+221)) and a β-galactosidase reporter and then subjected to sI or sI/R for the times shown, followed by extraction and reporter enzyme assays. *, p ≤ 0.05 different from control and all other values. B, cultured cardiac myocytes were transfected with GRP78(+221)-Luc or GRP94-(−800 to +105)-Luc (GRP94(+105)) and subjected to oxygen and/or glucose deprivation for 20 h, followed by extraction and reporter enzyme assays. Shown are the mean relative luciferase values (luciferase/β-galactosidase), expressed as the percentage of maximum for GRP78(+221)-Luc ± S.E. *, &, and #, p < 0.01 different from all other values for GRP78(+221)-Luc; §, p ≤ 0.05 different from all other values for GRP94-(−800 to +105)-Luc. *, #, §, and &, p ≤ 0.05 different from control and all other values.

Tissue ischemia results from a combination of nutrient and oxygen deprivation. Accordingly, to dissect the mechanism of ER stress response gene activation by simulated ischemia, the effects of starving cells of glucose and/or oxygen on GRP78(+221)-Luc activity were examined. GRP78 promoter activation in cells subjected to 20 h of glucose deprivation was 1.5-fold control, whereas promoter activity actually decreased in cells subjected to only oxygen deprivation (Fig. 2B, bars 1, 3, and 5). However, GRP78 promoter activation in cells subjected to 20 h of glucose and oxygen deprivation was 4-fold control (Fig. 2B, bar 7). To examine whether other ER stress response genes exhibit this pattern, we tested the effects of glucose and/or oxygen deprivation on GRP94-Luc activity. The results using the GRP94 promoter were very similar to those obtained with the GRP78 promoter (Fig. 2B, bars 2, 4, 6, and 8). Thus, deprivation of both glucose and oxygen, which most accurately mimics tissue ischemia, was required to obtain maximal induction of these two prototypical ER stress response gene promoters.

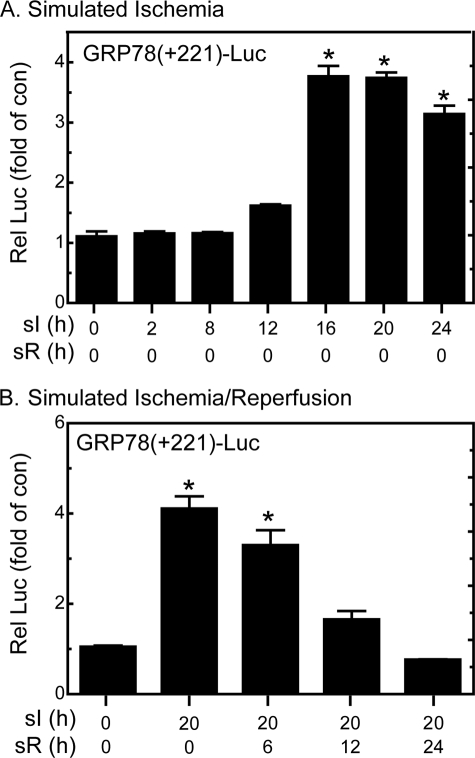

To compare the kinetics of GRP78 mRNA induction with promoter activation during sI, cardiac myocytes were transfected with GRP78(+221)-Luc and then subjected to sI or sI/R for various times. Although GRP78 promoter activity was slightly increased as early as 12 h of sI, maximal activation was observed after 16 h of sI and remained at this level through 24 h, the longest sI time examined (Fig. 3A). When cells were subjected to sI for a single time, 20 h, and then subjected to simulated reperfusion for various times, there was a progressive decline in reporter activity, reaching basal values by 24 h of sR (Fig. 3B). The relative kinetics of human GRP78 promoter activation and rat grp78 mRNA accumulation upon sI as well as the reduction of both upon sI/R support the hypothesis that, at least in part, sI-mediated grp78 induction is due to increased transcription during sI, which is reduced to basal levels upon sI/R.

FIGURE 3.

Effect of sI/R on GRP78-luciferase. A, cultured cardiac myocytes were transfected with GRP78(+221)-Luc and a β-galactosidase reporter and then subjected to various sI, followed by extraction and reporter enzyme assays. B, cardiac myocytes transfected as described in A were subjected to 20 h of sI, followed by various times of simulated reperfusion (sI/R), followed by extraction and reporter enzyme assays. Shown are the mean relative luciferase values (luciferase/β-galactosidase), expressed as -fold control (no sI; no sR) ± S.E. *, p ≤ 0.05 different from control and all other values.

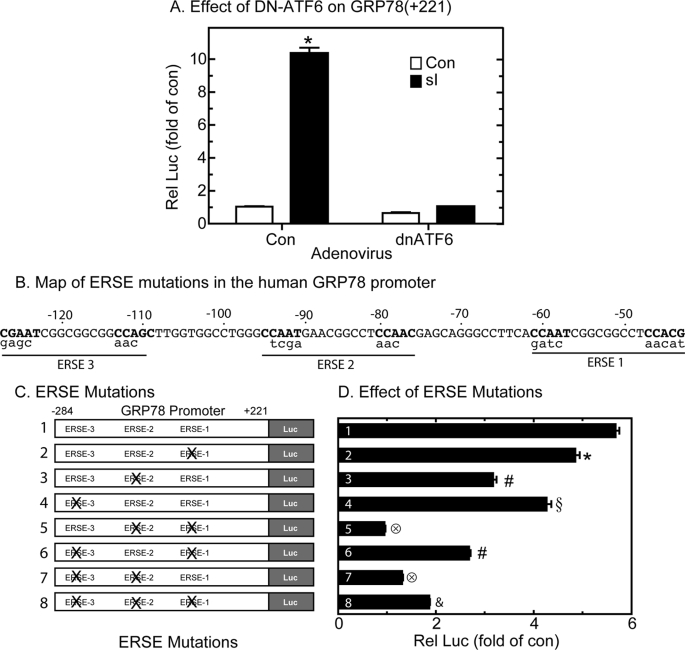

Effect of Dominant Negative ATF6 on sI-mediated GRP78 Promoter Activation

To examine roles for ATF6 in sI-mediated GRP78 induction, GRP78(+221)-Luc-transfected cultures were infected with adenovirus encoding a dominant negative form of ATF6, dnATF6.7 Although sI-mediated GRP78 promoter activation in cultures infected with a control adenovirus was 10-fold of control, promoter activation was completely blocked in cells expressing dnATF6 (Fig. 4A). This result suggests that under these conditions, endogenous ATF6 is required for sI-mediated GRP78 promoter activation. Accordingly, we investigated the roles of ATF6 binding sites in the GRP78 gene in sI-mediated induction.

FIGURE 4.

Effect of dominant negative ATF6 and ERSE mutations on sI-activated GRP78-Luc. A, cultured cardiac myocytes were transfected with GRP78-(+221)-Luc and a β-galactosidase reporter and later infected with AdV-Con or AdV-DN-ATF6. After 24 h, they were subjected to 20 h of sI, followed by extraction and reporter enzyme assays. Shown are the mean relative luciferase values (luciferase/β-galactosidase), expressed as -fold control (no sI) ± S.E. *, p ≤ 0.05 different from control and all other values. B, ERSEs 1, 2, and 3 are shown; the CCAAT-like motifs required for NF-Y and ATF6 binding are designated in boldface type. The mutations in the CCAAT-like motif and NFY-binding sites are shown in lowercase type below each ERSE. These mutations replicated those previously studied in the human GRP78 promoter (32). C, shown are the eight constructs used in this study. Construct 1 is the plasmid encoding the GRP78 promoter from −284 to +221 containing three ERSEs. Constructs 2–8 contain mutations that disrupt the ERSEs, as shown. D, cultured cardiac myocytes were co-transfected with either an empty vector control or with one of the eight constructs and β-galactosidase and, 48 h later, subjected to 20 h of sI, extracted, and then analyzed for reporter activities. Shown are the mean relative luciferase values (luciferase/β-galactosidase), expressed as -fold control (no sI) ± S.E. *, #, §, 196, and &, p ≤ 0.05 different from control and all other values.

Effect of ERSE Mutations on sI-mediated GRP78 Promoter Activation

In order to transcriptionally induce ER stress response genes, activated ATF6 can bind to ATF6 binding sites (29) or to ERSEs composed of the 19-nucleotide motif CCAATN9CCACG, in the regulatory regions of genes (28, 29, 48–50). The human GRP78 promoter contains three ERSEs; the promoter proximal ERSE, ERSE 1, is the only consensus ERSE, and it was shown in HeLa cells to be responsible for nearly all of the promoter activation observed in response to TM (27). To examine whether ERSE 1 is involved in sI-mediated GRP78 promoter activation, it was mutated in the context of GRP78(+221)-Luc (Fig. 4B), generating construct 2 (Fig. 4C). In contrast to previous findings with TM, mutating ERSE1 minimally affected sI-mediated promoter activation (Fig. 4D, construct 1 versus construct 2). Accordingly, the other ERSEs were mutated (Fig. 4C); mutating ERSEs 2 or 3 decreased sI-mediated promoter activation by 40 and 28%, respectively (Fig. 4D, construct 1 versus construct 3 or 4), suggesting that in this context, none of the three previously identified ERSEs accounted for all of the promoter induction by sI. Therefore, combinatorial mutations of the ERSEs were prepared (Fig. 4C, constructs 5–8). Mutating ERSEs 1 and 2 or ERSEs 2 and 3 conferred the greatest reduction in sI-mediated promoter activation, amounting to a nearly complete blockade of sI-mediated promoter activation (Fig. 4D, constructs 5 and 7). Therefore, in contrast to previous results with TM in HeLa cells, ERSE 2 appeared to play a dominant role in sI-mediated GRP78(+221)-Luc induction; however, it required that either ERSE 1 or ERSE 3 remain intact for maximal promoter activation.

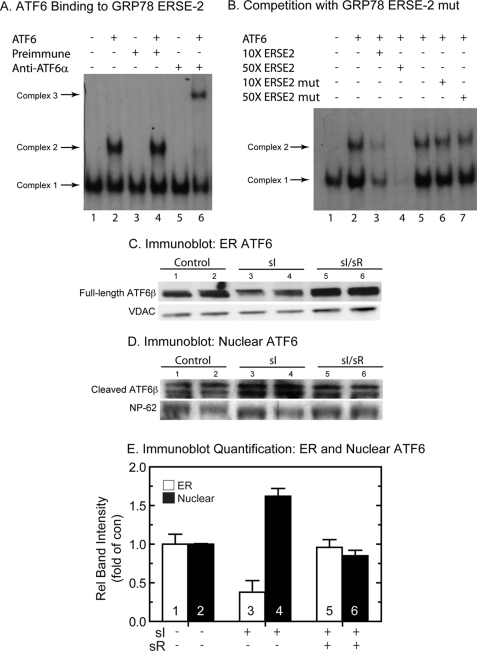

ATF6 Binding to GRP78 ERSE 2

Since ERSE 2 played a dominant role in sI-mediated promoter activation, electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) were carried out to examine whether ATF6 could bind to a labeled oligonucleotide that mimicked ERSE 2 in the human GRP78 gene. It has previously been shown that ATF6 binding to ERSEs requires the presence of three additional nuclear proteins, NF-Y A, B, and C (51). Accordingly, nuclear extracts of untreated cardiac myocytes were used as a source of NF-Y A, B, and C, as previously described (23). Incubation of nuclear extract with a labeled GRP78 ERSE 2 oligonucleotide resulted in the formation of a single complex, Complex 1 (Fig. 5A, lane 1), which has been shown to be due to the binding of NF-Y A, B, and C to the ERSE in the absence of ATF6 (51). The addition of recombinant ATF6 resulted in the formation of an additional, larger complex, Complex 2 (Fig. 5A, lane 2), which is due to ATF6 and NF-Y binding to the ERSE 2 oligonucleotide. To verify the presence of ATF6 in Complex 2, supershift EMSA experiments were carried out. Although the addition of preimmune antiserum to the reaction did not alter Complex 2 formation (Fig. 5A, lanes 3 and 4), the addition of an ATF6-specific antiserum shifted the mobility of Complex 2 to a higher molecular weight (Fig. 5A, lane 6) but had no effect on Complex 1 (Fig. 5A, lane 5), thus confirming the presence of ATF6 only in Complex 2. Competition studies showed that although the addition of excess unlabeled native ERSE 2 to the binding reaction disrupted the formation of Complexes 1 and 2 in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 5B, lanes 1–4), the addition of an unlabeled mutated form of ERSE 2, which does not bind NF-Y or ATF6, had no significant effect on complex formation (Fig. 5B, lanes 5–7). These results demonstrate that ERSE 2, which is not a consensus ERSE, is capable of binding ATF6 and could therefore be responsible for GRP78 transcriptional induction during sI.

FIGURE 5.

Electromobility shift assays and ATF6 immunoblots. A, to examine ATF6 binding to the GRP78 ERSE 2, EMSA analysis was carried out as described under “Materials and Methods.” Recombinant ATF6-(116–373), used in the reactions analyzed in lanes 2, 4, and 6, was prepared by in vitro transcription/translation and then added to neonatal rat ventricular myocyte nuclear extracts, as previously described (28). The 32P-labeled GRP78 ERSE 2 probe was added to initiate the binding reactions. Complex 1 is due to direct binding of nuclear extract-derived proteins (e.g. NF-Y and YY1) to the ERSE and has been shown to be required before ATF6 will bind under these conditions. For the supershift, EMSA was carried out as described, except for the addition of either preimmune or ATF6 antiserum to lanes 3, 4, 5, and 6, as shown. B, competition binding EMSA was carried out as described above, except for the addition of 10× or 50× unlabeled GRP78 ERSE 2 oligonucleotide to lanes 3 and 4 or 10× and 50× mutated GRP78 ERSE 2 oligonucleotide to lanes 6 and 7. C and D, cultured cardiac myocytes were treated with sI or sI/R, extracted, and subjected to subcellular fractionation, as described under “Materials and Methods” (n = 2 cultures/treatment; ∼20 × 106 cells/culture). The ER fraction (C) and the nuclear fraction (D) were then analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting for ATF6β. The region of the gel that includes the full-length endogenous ATF6 is shown in C, whereas the region of the gel that includes the cleaved active form of ATF6β is shown in D. Also shown are VDAC and NP-62, which are used as loading controls for ER and nuclear fractions, respectively. The reason for the ATF6β doublet is not known; however, it is possible that this could represent variable cleavage by S1P and/or S2P. E, immunoblots shown in C and D were quantified by densitometry. Shown are ATF6β/VDAC (ER) or ATF6β/NP-62 (Nuclear) as relative band intensity. ER and nuclear sI and sI/R values were normalized to ER and nuclear control values, respectively. n = 2 cultures/treatment, as described in C and D.

Activation of ATF6 by Simulated Ischemia

The results to this point were consistent with a role for ATF6 in ischemia-mediated GRP78 transcriptional induction. Accordingly, subcellular fractionation and immunoblotting were used to examine the effects of sI and sI/R on ATF6 processing and translocation in cultured cardiac myocytes. There are two forms of ATF6; ATF6α and ATF6β are both cleaved during ER stress, and the N-terminal fragments translocate to the nucleus, where they bind to ERSEs and influence ER stress response gene expression (28, 30, 52, 53). However, upon activation, ATF6α is extremely labile, making it difficult to detect after cleavage and translocation, whereas ATF6β is much more stable (23, 40). We initially attempted to examine the levels of ATF6α in cultured cardiac myocytes subjected to sI and sI/R but were unable to consistently detect the cleaved, nuclear form, due to its rapid degradation. Accordingly, the effect of ischemia on ATF6 activation was examined by immunoblotting for ATF6β in ER and nuclear fractions from cultured cardiac myocytes subjected to sI or sI/R. Full-length ATF6β decreased in the ER fraction upon sI (Fig. 5C, lanes 1 and 2 (control) versus lanes 3 and 4 (sI)) by ∼60% (Fig. 5E, bars 1 and 3), whereas cleaved active ATF6β in nuclear fractions increased (Fig. 5D, lanes 1 and 2 (control), versus lanes 3 and 4 (sI)) by ∼60% (Fig. 5E, bars 2 and 4). In contrast to sI, full-length ATF6β in the ER (Fig. 5C, lanes 5 and 6) and nuclear fractions (Fig. 5D, bars 5 and 6) returned to control (Fig. 5E, bars 5 and 6) upon sI/R. Thus, upon sI, there was a decrease in ER-associated ATF6β that coordinated with an increase in nuclear ATF6β. These results indicate that ER-associated ATF6β was cleaved and that the active form of ATF6β translocated to the nucleus. Moreover, ATF6β activation was reversed upon simulated reperfusion, consistent with the reversal of GRP78 gene induction during reperfusion (see Figs. 1–3).

Effect of Knockdown of ATF6 on GRP78 Expression and Cell Survival during sI and sI/sR

To further examine roles for endogenous ATF6 in sI-mediated grp78 induction, siRNA targeted to rat ATF6 was developed, and the levels of ATF6 mRNA in cultured cells were examined to assess efficacy of knockdown. Compared with cardiac myocytes transfected with a control, scrambled siRNA, cultures transfected with the ATF6-targeted siRNA exhibited an approximately 90% decrease in endogenous ATF6 mRNA (Fig. 6A, bars 1 and 2). When rat grp78 mRNA was examined, it was shown that compared with cells transfected with the control siRNA, grp78 mRNA levels were reduced by at least 80% in cultures transfected with the ATF6-targeted siRNA, either under control conditions (Fig. 6A, bars 3 and 4) or during sI (Fig. 6A, bars 5 and 6). As expected, sI/R had no effect on grp78 mRNA (Fig. 6A, bars 7 and 8).

FIGURE 6.

Effects of ATF6-targeted siRNA or miRNA on GRP78 mRNA and cell survival. A, cultured cardiac myocytes were transfected with a control or ATF6 siRNA. After 24 h, cultures were subjected to sI for 20 h plus sR for a subsequent 24 h. Cultures were then extracted and subjected to reverse transcription quantitative PCR to determine the levels of rat atf6 mRNA (bars 1 and 2) or rat grp78 mRNA, relative to gapdh. Shown are the mean values of grp78/gapdh mRNA, expressed as -fold control (bar 1) ± S.E. * and #, p ≤ 0.05 different from all other values. B, cultured cardiac myocytes were infected with AdV encoding a control, nontargeted miRNA (Con, bar 1) or with AdV encoding ATF6-targeted miRNA. Cultures were then extracted and subjected to reverse transcription quantitative PCR to determine the levels of ATF6 mRNA (bars 1 and 2) relative to GAPDH. Shown are the mean values of rat ATF6 or rat grp78/gapdh mRNA, expressed as -fold control (bar 1) ± S.E. for each treatment (n = 3 cultures/treatment; three experiments compiled). Alternatively, cultures were infected with control or ATF6-targeted miRNA, subjected to sI or sI/R, as shown, and then examined for cell death, as described under “Materials and Methods.” Shown are the mean values of cell death ± S.E., expressed as the percentage of dead cells. *, #, and §, p ≤ 0.05 different from control and different from each other.

Previous studies demonstrated that ATF6 activation in the mouse heart in vivo can protect cardiac myocytes from ischemia/reperfusion damage (24). Accordingly, to examine the functional role of endogenous ATF6 on cell survival during sI and sI/R, recombinant adenovirus (AdV) encoding either a control miRNA or an ATF6-targeted miRNA was generated. Compared with control, ATF6-targeted miRNA decreased basal ATF6 mRNA levels by about 80% (Fig. 6B, bars 1 and 2). Compared with control, ATF6-targeted miRNA had no effect on cell death in the absence of sI or sI/R (Fig. 6B, bar 3 versus bar 4). However, ATF6 miRNA increased cell death during sI (Fig. 6B, bars 5 and 6) and sI/R (Fig. 6B, bar 7 versus bar 8). These results are consistent with findings in ATF6 transgenic mice (38), which support protective roles for the ATF6 branch of the ER stress response during sI and sI/R.

DISCUSSION

In this study, simulating ischemia by depriving cultured cardiac myocytes of glucose and oxygen induced the prototypical ER stress response gene, GRP78. Although there have been no studies addressing whether ATF6 is activated during ischemia, numerous publications have demonstrated roles for HIF-1α as a mediator of gene induction under certain conditions of relatively mild ischemia and hypoxia. Moreover, there are several ER stress response genes that are inducible by both ATF6 and HIF-1 (e.g. heme oxygenase-1, stanniocalcin-2, and GRP94) (54–56). Thus, it was possible that ischemia-mediated grp78 gene induction could have been due, at least in part, to HIF-1α activation. However, under the conditions employed in this study, expression of the prototypical HIF-1-inducible gene, pgk, was not increased; nor was active HIF-1α. This was consistent with previous studies showing that HIF-1α activation is minimal under very low oxygen concentrations (43), such as 0.1% used in the current study. Interestingly, the levels of alternate forms of HIF-1α, which are endogenous inhibitors of HIF-1-mediated gene induction, were increased, suggesting that HIF-mediated gene induction might be inhibited under these conditions. Therefore, the remainder of the study focused on examining the involvement of ATF6 in mediating the effects of ischemia on grp78 gene induction.

Consistent with roles for ATF6 were our findings that upon sI, the inactive ER membrane form of ATF6β translocated to the nucleus, where it accumulated as the active form. Moreover, we showed that ATF6 could bind to a key ERSE in the GRP78 gene that we found to be responsible for transcriptional induction under these conditions.8 ATF6 activation and GRP78 gene induction were reversed upon simulated reperfusion, suggesting that in this model, ER stress is activated during simulated ischemia but not reperfusion. We also showed that ATF6 protected cells from death during ischemia as well as reperfusion, indicating that some genes regulated by ER stress during ischemia encode proteins that may precondition myocardial cells to better withstand the damaging effects of reperfusion.

Several studies have shown that ischemia or hypoxia can activate the PERK or IRE-1 branches of the ER stress response in cultured cells and tissues. For example, hypoxia is a potent trigger of PERK activation in cultured tumor cell lines. Moreover, it appears that this branch of the ER stress response fosters protection under these conditions, since cells with disrupted PERK exhibit impaired survival and/or proliferation upon hypoxia (57, 58). Hypoxia also activates the IRE-1 branch of the ER stress response in cultured cells, leading to the generation of the transcription factor, XBP-1, which augments tumor and normal cell survival (59). However, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of ATF6 activation by ischemia.

Although it is clear that all three branches of the ER stress response can be activated in response to ischemia and/or hypoxia, the precise mechanism by which oxygen deprivation activates ER stress is not well understood. It seems probable that disruption of the oxidative environment in the ER by hypoxia leads to ER protein misfolding. In support of this are the findings that ER protein folding requires oxygen-driven redox coupling of two well known ER stress response proteins, ERO1 (ER oxidoreductin 1) and protein-disulfide isomerase (60, 61). In fact, ERO1 uses molecular oxygen as a terminal electron acceptor. Therefore, it is probable that hypoxia reduces this redox coupling, thus providing a direct mechanism by which hypoxia might impair ER protein folding. Interestingly, there are two isoforms of ERO1, ERO1-Lβ, which is induced by ER stress (62), and ERO1-Lα, which is induced during hypoxia by HIF-1α (63, 64). This provides a potential linkage between HIF-1α and ER stress as mediators of a portion of the ischemia-dependent gene program. It is also of interest to note that although molecular oxygen is required for efficient ER protein disulfide bond formation and folding, when oxygen is consumed by ERO1, potentially damaging reactive oxygen species are generated (65), suggesting that a delicate balance of the ERO1/protein-disulfide isomerase redox couple must be maintained in order to optimize protein folding while minimizing reactive oxygen species generation (66).

ER stress has been shown to be both protective and damaging. In terms of protection, a study showed that in cancer and tumor cells, simulated ischemia activates the ER stress response, which promotes cell survival under these conditions (58). Moreover, the rate of tumor growth sometimes surpasses neoangiogenesis in aggressively growing solid tumors, leading to hypoxia and activation of the ER stress response, which enhances tumor survival and drug resistance (67). In the brain, ischemia induces a variety of ER stress response genes that are believed to contribute to the protective effects of ischemic preconditioning (68). Induction of ER stress response gene-encoded chaperones protects from ischemic damage in the brain (69, 70). A protective role for ER stress in the ischemic kidney has also been implicated (71). Moreover, several studies have implicated protective roles for ER stress in the heart. For example, when mouse hearts are subjected to aortic banding, they initially undergo hypertrophic growth that is often associated with cardiac myocyte protection; ER stress is activated during this growth phase (72). Also, overexpression of GRP94 protects cardiac myocytes from oxidative damage (73), and overexpression of GRP78 decreased hypoxia-mediated cell death of cultured cardiac myocytes (74). Furthermore, siRNA-mediated knockdown of XBP1 in cultured cardiac myocytes increases ischemia/reperfusion-mediated cell death (20). Moreover, ATF6 activation in transgenic mouse hearts decreases myocardial tissue damage in hearts subjected to ischemia/reperfusion (24).

In terms of damage, a study showed that activation of ER stress in the hearts of transgenic mice that overexpress monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 results in tissue damage and heart failure (75). Additionally, transgenic mice that overexpress a mutant form of the KDEL receptor, which is required for ER retention of many ER stress response gene products, increases ER stress, causing cardiac tissue damage and heart failure (76). Overexpression of the ER stress response gene, Puma (p53-up-regulated modulator of apoptosis), causes apoptosis in cultured cardiac myocytes (77), and knocking out Puma in the mouse heart in vivo reduces myocyte death from ischemia/reperfusion (78). Interestingly, one study showed that in cultured cardiac myocytes subjected to simulated ischemia, ER stress appeared to be protective early on, but upon prolonged ER stress, the cells succumbed to apoptosis (22). Because of the dichotomous nature of the end points of ER stress, a better understanding of the molecular mechanisms that determine whether ER stress is protective or damaging is required.

In summary, the results of this study suggest that ER stress contributes to the hypoxia-mediated reshaping of gene expression during ischemia in ways that may affect cell survival during ischemia/reperfusion. Future studies addressing the roles of ischemia-responsive ER stress response genes will be required to decipher the functionality of each in the context of determining the fate of ischemic tissue. Presumably, the various ischemia-responsive pathways are activated under different conditions, such as the severity of the ischemia and the metabolic demands of the affected tissue. Accordingly, investigating the activation of each pathway under various conditions, as well as elucidating the pathway-specific gene programs, will be required to better understand the specific functions of each as determinants of cell survival and tissue damage.

Acknowledgments

We thank Matthew Scott Glassy, Dr. Ross Whittaker, Archana Tadimalla, John Vekich, and Dr. Randy S. Johnson for helpful discussions during preparation of the manuscript.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants HL-075573 and HL-085577.

GRP78(+7)-Luc is composed of nucleotides −284 to +7 of the human GRP78 promoter driving luciferase.

GRP78(+221)-Luc is composed of nucleotides −284 to +221 of the human GRP78 promoter driving luciferase.

Dominant negative ATF6 is composed of a DNA-binding domain but lacking a transcriptional activation domain.

The promoters of numerous other known or putative ER stress response genes, such as GRP94, ERDJ4, RCAN1, and MANF, were also examined under these conditions and were shown to be activated by ischemia but not reperfusion.

- ER

- endoplasmic reticulum

- ERSE

- ER stress response element

- sI

- simulating ischemia

- sI/R

- simulating ischemia/reperfusion

- sR

- simulating reperfusion

- siRNA

- small interfering RNA

- miRNA

- microRNA

- EMSA

- electrophoretic mobility shift assay

- TM

- tunicamycin

- EMSA

- electrophoretic mobility shift assay

- AdV

- adenovirus

- BisTris

- 2-[bis(2-hydroxyethyl)amino]-2-(hydroxymethyl)propane-1,3-diol.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lee A. S. (2001) Trends Biochem. Sci. 26, 504–510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu J., Kaufman R. J. (2006) Cell Death Differ. 13, 374–384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xu C., Bailly-Maitre B., Reed J. C. (2005) J. Clin. Invest. 115, 2656–2664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Glembotski C. C. (2007) Circ. Res. 101, 975–984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim I., Xu W., Reed J. C. (2008) Nat. Rev. Drug. Discov. 7, 1013–1030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bailey D., O'Hare P. (2007) Antioxid. Redox Signal. 9, 2305–2321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yoshida H. (2007) Antioxid. Redox Signal. 9, 2323–2333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Malhotra J. D., Kaufman R. J. (2007) Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 18, 716–731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iwawaki T., Hosoda A., Okuda T., Kamigori Y., Nomura-Furuwatari C., Kimata Y., Tsuru A., Kohno K. (2001) Nat. Cell Biol. 3, 158–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meusser B., Hirsch C., Jarosch E., Sommer T. (2005) Nat. Cell Biol. 7, 766–772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ogata M., Hino S., Saito A., Morikawa K., Kondo S., Kanemoto S., Murakami T., Taniguchi M., Tanii I., Yoshinaga K., Shiosaka S., Hammarback J. A., Urano F., Imaizumi K. (2006) Mol. Cell. Biol. 26, 9220–9231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bernales S., McDonald K. L., Walter P. (2006) PLoS Biol. 4, e423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gustafsson A. B., Gottlieb R. A. (2008) J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 44, 654–661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heath-Engel H. M., Chang N. C., Shore G. C. (2008) Oncogene 27, 6419–6433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Szegezdi E., Logue S. E., Gorman A. M., Samali A. (2006) EMBO Rep. 7, 880–885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Egger L., Schneider J., Rhême C., Tapernoux M., Häcki J., Borner C. (2003) Cell Death Differ. 10, 1188–1203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dudgeon D. D., Zhang N., Ositelu O. O., Kim H., Cunningham K. W. (2008) Eukaryot. Cell 7, 2037–2051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ullman E., Fan Y., Stawowczyk M., Chen H. M., Yue Z., Zong W. X. (2008) Cell Death Differ. 15, 422–425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frand A. R., Cuozzo J. W., Kaiser C. A. (2000) Trends Cell Biol. 10, 203–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thuerauf D. J., Marcinko M., Gude N., Rubio M., Sussman M. A., Glembotski C. C. (2006) Circ. Res. 99, 275–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Terai K., Hiramoto Y., Masaki M., Sugiyama S., Kuroda T., Hori M., Kawase I., Hirota H. (2005) Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 9554–9575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Szegezdi E., Duffy A., O'Mahoney M. E., Logue S. E., Mylotte L. A., O'brien T., Samali A. (2006) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 349, 1406–1411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thuerauf D. J., Marcinko M., Belmont P. J., Glembotski C. C. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 22865–22878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martindale J. J., Fernandez R., Thuerauf D., Whittaker R., Gude N., Sussman M. A., Glembotski C. C. (2006) Circ. Res. 98, 1186–1193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harpster M. H., Bandyopadhyay S., Thomas D. P., Ivanov P. S., Keele J. A., Pineguina N., Gao B., Amarendran V., Gomelsky M., McCormick R. J., Stayton M. M. (2006) Mamm. Genome 17, 701–715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhu C., Johansen F. E., Prywes R. (1997) Mol. Cell. Biol. 17, 4957–4966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yoshida H., Haze K., Yanagi H., Yura T., Mori K. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 33741–33749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haze K., Yoshida H., Yanagi H., Yura T., Mori K. (1999) Mol. Biol. Cell 10, 3787–3799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang Y., Shen J., Arenzana N., Tirasophon W., Kaufman R. J., Prywes R. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 27013–27020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thuerauf D. J., Arnold N. D., Zechner D., Hanford D. S., DeMartin K. M., McDonough P. M., Prywes R., Glembotski C. C. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 20636–20643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bose A. K., Mocanu M. M., Carr R. D., Yellon D. M. (2007) Cardiovasc. Drugs Ther. 21, 253–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hausenloy D. J., Yellon D. M. (2007) Heart 93, 649–651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lin J. H., Walter P., Yen T. S. (2008) Annu. Rev. Pathol. 3, 399–425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mocanu M. M., Yellon D. M. (2007) Br. J. Pharmacol. 150, 833–838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Scheuner D., Kaufman R. J. (2008) Endocr. Rev. 29, 317–333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yellon D. M., Hausenloy D. J. (2007) N. Engl. J. Med. 357, 1121–1135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brown M. S., Ye J., Rawson R. B., Goldstein J. L. (2000) Cell 100, 391–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Belmont P. J., Tadimalla A., Chen W. J., Martindale J. J., Thuerauf D. J., Marcinko M., Gude N., Sussman M. A., Glembotski C. C. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 14012–14021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Craig R., Wagner M., McCardle T., Craig A. G., Glembotski C. C. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 37621–37629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thuerauf D. J., Morrison L., Glembotski C. C. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 21078–21084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tadimalla A., Belmont P. J., Thuerauf D. J., Glassy M. S., Martindale J. J., Gude N., Sussman M. A., Glembotski C. C. (2008) Circ. Res. 103, 1249–1258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Firth J. D., Ebert B. L., Pugh C. W., Ratcliffe P. J. (1994) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 91, 6496–6500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jiang B. H., Semenza G. L., Bauer C., Marti H. H. (1996) Am. J. Physiol. 271, C1172–C1180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gothié E., Richard D. E., Berra E., Pagès G., Pouysségur J. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 6922–6927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chun Y. S., Choi E., Yeo E. J., Lee J. H., Kim M. S., Park J. W. (2001) J. Cell Sci. 114, 4051–4061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yang Q., Sarnow P. (1997) Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 2800–2807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Macejak D. G., Sarnow P. (1991) Nature 353, 90–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Roy B., Li W. W., Lee A. S. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 28995–29002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Parker R., Phan T., Baumeister P., Roy B., Cheriyath V., Roy A. L., Lee A. S. (2001) Mol. Cell. Biol. 21, 3220–3233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li M., Baumeister P., Roy B., Phan T., Foti D., Luo S., Lee A. S. (2000) Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 5096–5106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yoshida H., Okada T., Haze K., Yanagi H., Yura T., Negishi M., Mori K. (2000) Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 6755–6767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Haze K., Okada T., Yoshida H., Yanagi H., Yura T., Negishi M., Mori K. (2001) Biochem. J. 355, 19–28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yoshida H., Okada T., Haze K., Yanagi H., Yura T., Negishi M., Mori K. (2001) Mol. Cell. Biol. 21, 1239–1248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lee P. J., Jiang B. H., Chin B. Y., Iyer N. V., Alam J., Semenza G. L., Choi A. M. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 5375–5381 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Law A. Y., Lai K. P., Ip C. K., Wong A. S., Wagner G. F., Wong C. K. (2008) Exp. Cell Res. 314, 1823–1830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Paris S., Denis H., Delaive E., Dieu M., Dumont V., Ninane N., Raes M., Michiels C. (2005) FEBS Lett. 579, 105–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Koumenis C., Wouters B. G. (2006) Mol. Cancer Res. 4, 423–436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bi M., Naczki C., Koritzinsky M., Fels D., Blais J., Hu N., Harding H., Novoa I., Varia M., Raleigh J., Scheuner D., Kaufman R. J., Bell J., Ron D., Wouters B. G., Koumenis C. (2005) EMBO J. 24, 3470–3481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Romero-Ramirez L., Cao H., Nelson D., Hammond E., Lee A. H., Yoshida H., Mori K., Glimcher L. H., Denko N. C., Giaccia A. J., Le Q. T., Koong A. C. (2004) Cancer Res. 64, 5943–5947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Feldman D. E., Chauhan V., Koong A. C. (2005) Mol. Cancer Res. 3, 597–605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Görlach A., Klappa P., Kietzmann T. (2006) Antioxid. Redox Signal. 8, 1391–1418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pagani M., Fabbri M., Benedetti C., Fassio A., Pilati S., Bulleid N. J., Cabibbo A., Sitia R. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 23685–23692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gess B., Hofbauer K. H., Wenger R. H., Lohaus C., Meyer H. E., Kurtz A. (2003) Eur. J. Biochem. 270, 2228–2235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.May D., Itin A., Gal O., Kalinski H., Feinstein E., Keshet E. (2005) Oncogene 24, 1011–1020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tu B. P., Weissman J. S. (2004) J. Cell Biol. 164, 341–346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Malhotra J. D., Kaufman R. J. (2007) Antioxid. Redox Signal. 9, 2277–2293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Koumenis C. (2006) Curr. Mol. Med. 6, 55–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Truettner J. S., Hu K., Liu C. L., Dietrich W. D., Hu B. (2009) Brain Res. 1249, 9–18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Oida Y., Izuta H., Oyagi A., Shimazawa M., Kudo T., Imaizumi K., Hara H. (2008) Brain Res. 1208, 217–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kudo T., Kanemoto S., Hara H., Morimoto N., Morihara T., Kimura R., Tabira T., Imaizumi K., Takeda M. (2008) Cell Death Differ. 15, 364–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Prachasilchai W., Sonoda H., Yokota-Ikeda N., Oshikawa S., Aikawa C., Uchida K., Ito K., Kudo T., Imaizumi K., Ikeda M. (2008) Eur. J. Pharmacol. 592, 138–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Okada K., Minamino T., Tsukamoto Y., Liao Y., Tsukamoto O., Takashima S., Hirata A., Fujita M., Nagamachi Y., Nakatani T., Yutani C., Ozawa K., Ogawa S., Tomoike H., Hori M., Kitakaze M. (2004) Circulation 110, 705–712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Vitadello M., Penzo D., Petronilli V., Michieli G., Gomirato S., Menabò R., Di Lisa F., Gorza L. (2003) FASEB J. 17, 923–925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pan Y. X., Lin L., Ren A. J., Pan X. J., Chen H., Tang C. S., Yuan W. J. (2004) J. Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 44, Suppl. 1, S117–S120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Azfer A., Niu J., Rogers L. M., Adamski F. M., Kolattukudy P. E. (2006) Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ Physiol. 291, H1411–H1420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hamada H., Suzuki M., Yuasa S., Mimura N., Shinozuka N., Takada Y., Suzuki M., Nishino T., Nakaya H., Koseki H., Aoe T. (2004) Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 8007–8017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Nickson P., Toth A., Erhardt P. (2007) Cardiovasc. Res. 73, 48–56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Toth A., Nickson P., Qin L. L., Erhardt P. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 3679–3689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]