Abstract

Cav1.4 channels are unique among the high voltage-activated Ca2+ channel family because they completely lack Ca2+-dependent inactivation and display very slow voltage-dependent inactivation. Both properties are of crucial importance in ribbon synapses of retinal photoreceptors and bipolar cells, where sustained Ca2+ influx through Cav1.4 channels is required to couple slow graded changes of the membrane potential with tonic glutamate release. Loss of Cav1.4 function causes severe impairment of retinal circuitry function and has been linked to night blindness in humans and mice. Recently, an inhibitory domain (ICDI: inhibitor of Ca2+-dependent inactivation) in the C-terminal tail of Cav1.4 has been discovered that eliminates Ca2+-dependent inactivation by binding to upstream regulatory motifs within the proximal C terminus. The mechanism underlying the action of ICDI is unclear. It was proposed that ICDI competitively displaces the Ca2+ sensor calmodulin. Alternatively, the ICDI domain and calmodulin may bind to different portions of the C terminus and act independently of each other. In the present study, we used fluorescence resonance energy transfer experiments with genetically engineered cyan fluorescent protein variants to address this issue. Our data indicate that calmodulin is preassociated with the C terminus of Cav1.4 but may be tethered in a different steric orientation as compared with other Ca2+ channels. We also find that calmodulin is important for Cav1.4 function because it increases current density and slows down voltage-dependent inactivation. Our data show that the ICDI domain selectively abolishes Ca2+-dependent inactivation, whereas it does not interfere with other calmodulin effects.

Retinal photoreceptors and bipolar cells contain a highly specialized type of synapse designated ribbon synapses. Glutamate release in these synapses is controlled via graded and sustained changes in membrane potential that are maintained throughout the duration of a light stimulus (1, 2). In recent years, it became clear that Cav1.4 L-type Ca2+ channels are the main channel subtype converting these analog input signals into corresponding permanent glutamate release (1, 3–5). In support of this mechanism, mutations in the Cav1.4 gene have been identified in patients suffering from congenital stationary night blindness type 2 and X-linked cone rod dystrophy (6–8). Individuals displaying congenital stationary night blindness type 2 as well as mice deficient in Cav1.4 typically have abnormal electroretinograms that indicate a loss of neurotransmission from the rods to second order bipolar cells, which is attributable to a loss of Cav1.4 (3).

Retinal Cav1.4 channels are set apart from other high voltage-activated (HVA)3 Ca2+ channels by their total lack of Ca2+-dependent inactivation (CDI) and their very slow voltage-dependent inactivation (VDI). Recently, we and others discovered an inhibitory domain (ICDI: inhibitor of CDI) in the C-terminal tail of the Cav1.4 channel that eliminates Ca2+-dependent inactivation in this channel by binding to upstream regulatory motifs (9, 10). Importantly, introducing the ICDI into the backbone of Cav1.2 or Cav1.3 almost completely abolishes the CDI of these channels. Contrasting with the clear cut function, the underlying mechanism by which ICDI abolishes CDI remains controversial. It was suggested that ICDI displaces the Ca2+ sensor calmodulin (CaM) from binding to the proximal C terminus (10), suggesting that the binding sites of CaM and ICDI are largely overlapping or allosterically coupled to each other. Alternatively, our own data rather suggested that CaM and the ICDI domain bind to different portions of the proximal C terminus (9). We proposed that the interaction between the ICDI domain and the EF-hand, a motif with a central role for transducing CDI (11–16), switches off CDI without impairing binding of CaM to the channel. In this study, we designed experiments to differentiate between these two models. Here, using FRET in HEK293 cells, we provide evidence that in living cells, CaM is bound to the full-length C terminus of Cav1.4 (i.e. in the presence of ICDI). Furthermore, our data suggest that the steric orientation of the CaM/Cav channel complex differs between Cav1.2 and Cav1.4 channels. We show that CaM preassociation with Cav1.4 controls current density and also affects VDI. Thus, although CaM does not trigger CDI in Cav1.4 as it does in other HVA Ca2+ channels, it is still an important regulator of this channel.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Constructs for Electrophysiology

For expression of murine Cav1.4 (17) (accession number AJ579852), the bicistronic pIRES2-EGFP expression vector (Clontech) was used. For the construction of truncated Cav1.4 channels lacking the ICDI (Cav1.4ΔICDI, previously termed C1884Stop (9)), a fragment of the wild-type Cav1.4 expression plasmid was replaced by DNA fragments that are carrying the required stop codon and a restriction site introduced by 3′ primers. In Cav1.4/5A channels, CaM preassociation is disrupted by mutating Ile-1592–Phe-1596 of the IQ motif to alanines, respectively. The mutated sequence (IQDYF) contains isoleucine 1592, glutamine 1593, and two highly conserved aromatic anchors (Tyr-1595 and Phe-1596) that in closely related Cav1.2 channels have been shown to form extensive contacts with CaM (19, 20).

Electrophysiology

HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with expression vectors encoding calcium channel α subunits together with equimolar amounts of vectors encoding β2a and α2δ1 as described in Ref. 17. ICa and IBa were measured by using the following solutions. For the pipette solution, we used 112 mm CsCl, 3 mm MgCl2, 3 mm MgATP, 10 mm EGTA, 5 mm HEPES, adjusted to pH 7.4 with CsOH; for experiments with low Ca2+ buffering, EGTA was reduced to 0.5 mm. For the bath solution, we used 82 mm NaCl, 30 mm BaCl2, 5.4 mm CsCl2, 1 mm MgCl2, 20 mm tetraethylammonium, 5 mm Hepes, 10 mm glucose, adjusted to pH 7.4 with NaOH. For experiments with 10 mm Ba2+ or 10 mm Ca2+ in the bath solution, the NaCl concentration was increased to 102 mm. ICa and IBa were measured from the same cell. Bath solution was changed by a local solution exchanger. Currents were recorded at room temperature 2–4 days after transfection by using the whole-cell patch clamp technique. Data were analyzed by using the Origin 6.1 software (OriginLab, Northampton, MA).

The peak IV relationship was measured by applying 350-ms or 5-s voltage pulses to potentials between −80 and +70 mV in 10-mV increments from a holding potential of −80 mV at 0.2 Hz. To obtain current densities, the current amplitude at Vmax was normalized to cell membrane capacitance (Cm). For determination of half-maximum activation voltage (V0.5), the chord conductance (G) was calculated from the current voltage curves by dividing the peak current amplitude by its driving force at that respective potential G = I/(Vm − Vrev), where Vrev is the extrapolated reversal potential, Vm is the membrane potential, and I is the peak current. The chord conductance was then fitted with a Boltzmann equation G = Gmax/(1 + e(V0.5−Vm)/kact), where Gmax is the maximum conductance, V0.5 is the half-maximum activation voltage, Vm is the membrane potential, and kact is the slope factor of the activation curve.

Cav1.4 channel inactivation was quantified by calculating the fraction of peak Ba2+ and Ca2+ currents remaining after 300 or 5000 ms of depolarization (R300 or R5000) as described (9). R300 is used to quantify CDI (fast process). R5000 is used to quantify VDI, a process that is intrinsically very slow in Cav1.4.

Constructs for FRET Imaging

For all FRET constructs, we used monomeric EYFP(A206K) or ECFP(A206K) (21, 22) to avoid homo- and heterodimerization. For simplicity, we refer to the different fluorescent proteins as “YFP” and “CFP” throughout the text. All FRET constructs were cloned into the pcDNA3 expression vector (Invitrogen).

For CaM interaction assays, the following YFP-tagged C-terminal fragments of Cav1.4 and Cav1.2 (rabbit Cav1.2b subunit (23); accession number X55763) were used: YFP-CT1.4 (Asp-1445–Leu-1984), YFP-CT1.4ΔICDI (Asp-1445–Thr-1883), YFP-CT1.4R1610Stop (Asp-1445–Gly-1609), and YFP-CT1.2 (Asp-1500–Leu-2166). In all CaM fusion constructs, CFP is fused N-terminally to CaM. In CFP-CaM, CFP is linked to CaM by an AAA linker (24, 25). In CFP227-CaM, CFP has been truncated after residue Ala-227 and linked to CaM by a CGC linker (26). We intentionally limited expression of CFP-CaM and CFP227-CaM by mutating the Kozac sequence from GCC GCC ACC ATG to GCC TCC TTT ATG in a subset of control experiments to avoid spurious FRET (27, 28). Cloning of CFPcp174 and CFPcp158 is described in Ref. 29. Briefly, the N and the C terminus of CFP are fused by a GGTGGS linker, and the new N and C termini were created as indicated in Fig. 1A. These permutations show similar spectral properties as the non-permutated fluorescent proteins (29). A Ca2+-insensitive CaM mutant harboring aspartate-to-alanine mutations in all four EF-hands (CaM1234) (30) was fused by an AAA linker to CFP or without a linker to CFPCp174. As negative control, CFP(A206K) and YFP(A206K) were used.

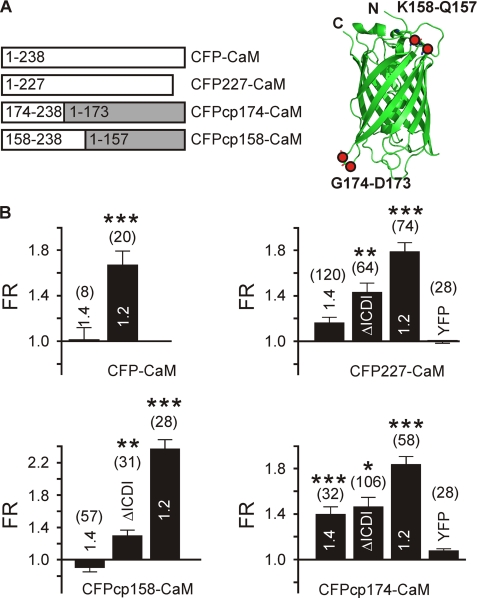

FIGURE 1.

FRET mapping of the CaM binding to the C terminus of Cav1.2 and Cav1.4. A, schematic of the CFP-CaM variants. Left and right, sequence (left) and steric orientation of the new C termini introduced in circularly permuted CFPs (right). The structure on the right was created by PyMOL (DeLano Scientific LLC, San Carlos, CA) using Protein Data Bank (PDB) accession code 1GFL. B, binding of CFP-CaM (top left), CFP227-CaM (top right), CFPcp158-CaM (bottom left), and CFPcp174-CaM (bottom right) to C termini of Cav1.4, Cav1.4ΔICDI, and Cav1.2 as indicated. FR is indicated; the number of cells is indicated in parentheses. *, p < 0.05, **, p < 0.01, ***, p < 0.001 as compared with control (CFP227 or CFPcp174 + YFP). Error bars indicate S.E.

For intramolecular FRET experiments, C-terminal fragments of Cav1.4 were N-terminally fused to YFP and C-terminally fused to CFP separated by a triple alanine linker. The fragments used for the respective fusion construct are as follows: YFP-CT1.4-CFP, complete C terminus of Cav1.4 (Asp-1445–Leu-1984); YFP-CT1.4Δ1493–1609-CFP, Asp-1445–Leu-1984 with a deletion of Gln-1493–Gly-1609; YFP-CT1.4Δ1445–1609-CFP, Asp-1445–Leu-1984 with a deletion of Asp-1445–Gly-1609.

For the ICDI interaction assays, YFP is fused to C-terminal fragments of Cav1.4. The C-terminal fragments for the respective constructs are as follows: YFP-CT1.4, complete C terminus (Asp-1445–Leu-1984); YFP-CT1.4ΔICDI, Asp-1445–Thr-1883; YFP-CT1.4R1610Stop, Asp-1445–Gly-1609; YFP-EF, Asp-1445–Ile-1492. Fragments of the ICDI domain C-terminally fused to CFP are as follows: ICDI-CFP, Leu-1885–Leu-1984; the proximal part of the ICDI proxICDI-CFP, Leu-1885–Lys-1929; the middle part of the ICDI midICDI-CFP, Gln-1930–Ala-1952; the distal part of the ICDI distICDI-CFP, Gln-1953–Leu-1984; XL-ICDI-CFP, Arg-1610–Leu-1984; L-ICDI-CFP, Ile-1742–Leu-1984.

FRET Measurements

HEK293 cells were grown on coverslips (ibiTreat, ibidi, Martinsried, Germany) and transiently transfected using FuGENE 6 (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). 1–2 days later, the cells were washed and maintained in buffer solution composed of 140 mm NaCl, 5 mm KCl, 1 mm MgCl2, 2 mm CaCl2, 10 mm glucose, 10 mm Na-HEPES, pH 7,4 at room temperature. Cells were placed on an inverted epifluorescence microscope equipped with an oil immersion 60× objective (UPlanSApo 60× OL/1.35, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) and a built-in dual-emission system (iMIC 2010 FRET module; TILL Photonics). For simultaneous recording of CFP and YFP emission, a multiband FRET filter set (CFP/YFP-A-000, Semrock, NY) was used consisting of a dual-band excitation filter (excitation bands: 416 ± 12.5 and 501 ± 9 nm), emission filter (emission bands: 464 ± 11.5 and 547 ± 15.5 nm), and dichroic beam splitter (reflection bands: 405 ± 22 and 502 ± 9 nm; transmission bands: 466 ± 17 and 549.5 ± 19.5 nm). Samples were excited with light from a Polychrome 5000 (TILL Photonics; center wave length ± 7.5 nm). The illumination time was set to 10 ms. For the single channels (CFP, YFP), mean intensity values derived from a selective background region near the investigated cell were used for background correction. After this correction, mean values for each cell were calculated from a region of interest drawn around a cell of interest. Images were recorded by a CCD camera (IMAGO-QE). The setup was controlled with the software TILLvisION (version 4.0) and a stand-alone DSP controller. TILLvisION was also used for the image analysis. All imaging equipment was supplied by TILL Photonics (part of Agilent Technologies) unless noted otherwise.

Measurements of single-cell FRET based on aggregate (nonspatial) fluorescence recordings were performed using three-cube FRET as described previously (24, 27). The notation and abbreviations used follow the definition of Refs. 24 and 27. The degree of FRET in an individual cell was quantified using the FRET ratio (FR), which is defined as the fractional increase in YFP emission caused by FRET. The FR was calculated using FR = [SFRET − (RD1)(SCFP)]/[(RA1)(SYFP − (RD2)(SCFP))].

Fluorescence measurements for the determination of SFRET, SCFP, and SYFP were performed in cells coexpressing CFP-tagged and YFP-tagged peptides or intramolecular FRET constructs dually labeled by CFP and YFP using the following parameters: SCFP, excitation at 416 ± 7.5 nm and emission at 464 ± 11.5 nm (donor excitation; donor emission); SFRET, excitation at 416 ± 7.5 nm and emission at 547 ± 15.5 nm (donor excitation; acceptor emission); and SYFP, excitation at 501 ± 7.5 nm and emission at 547 ± 15.5 nm (acceptor excitation; acceptor emission). RD1, RA1, and RD2 are experimentally predetermined constants from measurements applied to single cells expressing only CFP- or YFP-tagged molecules. These constants are used to correct for bleed-through of CFP into the YFP channel (RD1), direct excitation of YFP by CFP excitation (RA1), and the small amount of CFP excitation at the YFP excitation wavelength (RD2) as described by Ref. 24, 27.

Dynamic FRET

Kinetic measurements were performed using the setup described above and a 20× objective (UPlanSApo, N.A. 0.75, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Cells were maintained in buffer solution composed of 140 mm NaCl, 5 mm KCl, 1 mm MgCl2, 2 mm CaCl2, 10 mm glucose, 10 mm Na-HEPES, pH 7,4 at room temperature. 10 s after the start of the recording, 5 μm ionomycin was added. After 30 s, the cells were perfused with buffer solution containing 0 Ca2+, 5 μm ionomycin, and 5 mm EGTA. The illumination time was set to 100 ms. For ratiometric analysis, the ratio (R) of YFP and CFP fluorescence intensities was calculated as the following, R = SFRET/SCFP. The baseline ratio (R0) was calculated as an average of the first 10 s before stimulation. The ratio change (ΔR/R) is ΔR/R = (R − R0)/R0 (26, 31). For the single channels (CFP, YFP), mean intensity values derived from a selective background region near the investigated cell was used for background correction. After this correction, mean values for each cell were calculated from a region of interest drawn around a cell of interest. The ratio R was formed from the ratio of the background-corrected single channels.

Coimmunoprecipitation in HEK293 Cells

The complete C terminus of Cav1.4 containing the 5A mutation within the IQ motif (CT1.4/5A see above) or C-terminal fragments of Cav1.4 (CT1.4R1610Stop (Asp-1445–Gly-1609); CT1.4R1610Stop/5A) were amplified by PCR and cloned into the pcDNA3 expression vector. All sequences were fused with a Myc tag at the N terminus. CaM1234 was constructed in the same manner by using a 5′ primer containing the triple FLAG sequence. For expression of recombinant proteins, HEK293 cells were transfected by using the calcium phosphate method. Immunoprecipitation was performed 3 days after transfection. A detailed protocol has been published previously (9). Each coimmunoprecipitation was repeated at least three times.

Statistics

All values are given as mean ± S.E.; n is the number of experiments. An unpaired t test was performed for the comparison between two groups. Significance was tested by analysis of variance followed by Dunnett's test whether multiple comparisons were made. Values of p < 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

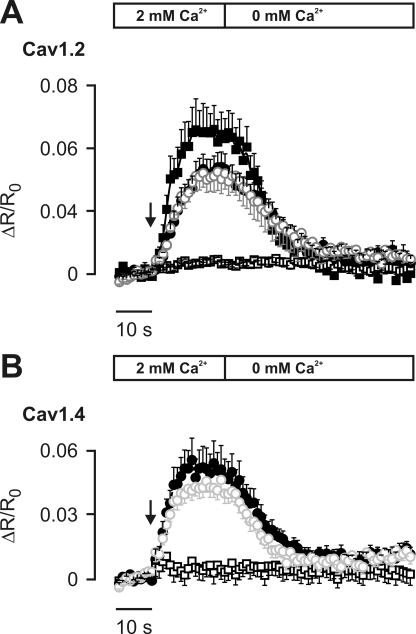

To test whether CaM is bound to Cav1.4 channels, we carried out FRET experiments in living cells using the full-length C terminus of Cav1.4 and CaM (Fig. 1, A and B). This approach has been successfully applied to other HVA Ca2+ channels (24, 25). We first fused wild type CFP and CaM by a flexible AAA linker (CFP-CaM). This construct yielded significant FRET with YFP-CT1.2, whereas there was no FRET for YFP-CT1.4 (Fig. 1B). A possible explanation for the lack of FRET could be that CaM does not bind to Cav1.4 as suggested previously (10). Alternatively, CaM may bind, but FRET could be prevented by structural constraints in the steric environment of the CaM binding region in Cav1.4. We addressed this problem using fusion proteins where CaM is attached to structurally modified CFPs (Fig. 1, A and B). A fusion protein where the last 11 residues of CFP have been truncated (CFP227-CaM) showed strong FRET in CT1.2 and in CT1.4ΔICDI, a CT1.4 variant lacking the ICDI domain. Importantly, in the wild type Cav1.4 C terminus, a very small FRET signal just below the threshold of significance was obtained. To further optimize the geometric orientation of the fluorophores, we fused CFP to CaM at different angles using circularly permutated CFPs (29, 32–34) (CFPcp158-CaM and CFPcp174-CaM; Fig. 1, A and B). To this end, the C and the N termini of wild type CFP were fused by a linker, and a new C and N termini were introduced at different positions. Using circularly permutated CFPs, CaM binding to CT1.2 and CT1.4ΔICDI could be detected (Fig. 1B). Notably, coexpression of CFPcp174-CaM and YFP-CT1.4 resulted in a significant FRET. The specificity of this interaction was demonstrated by the lack of FRET in the negative control (Fig. 1B). The FRET response for CFPcp174-CaM indicated that CaM binds to a target sequence in the C terminus and that binding of CaM is not prevented in the presence of the ICDI. To test whether the interaction observed is independent of resting Ca2+ levels and Ca2+ activation of CaM, we next used CaM mutant (CaM1234) that is deficient for Ca2+ binding (30). CaM1234 serves as a surrogate for apocalmodulin (apoCaM) and is known to preassociate with the C termini of other HVA Ca2+ channels (24, 25). Clear FRET could be observed between CFPcp174-CaM1234 and YFP-CT1.4 similar to that observed for CFPcp174-CaM and YFP-CT1.4 (supplemental Fig. S1). FRET between CaM and CT1.2 or CT1.4 could be significantly increased by raising the intracellular Ca2+ concentration above resting limits (Fig. 2, A and B). This increase was reversible because clamping intracellular Ca2+ to nominal zero Ca2+ decreased binding of CaM to resting levels. For CaM1234, no Ca2+-dependent changes in FRET could be observed.

FIGURE 2.

Raising intracellular [Ca2+] increases FRET between CaM and the C terminus of Cav1.2 and Cav1.4. A, time course of average ratiometric signal (ΔR/R) from YFP-tagged C termini of Cav1.2 coexpressed with CFPcp174-CaM (filled circles; n = 15), CFP227-CaM (open circles; n = 4), CFP-CaM (filled squares; n = 8), or CFP-CaM1234 (open squares; negative control; n = 6), before and after the addition of ionomycin (arrow) to a Ca2+-containing or nominal Ca2+-free solution as indicated and described under “Experimental Procedures.” B, Cav1.4 coexpressed with CFPcp174-CaM (filled circles; n = 12), CFP227-CaM (open circles; n = 14), or CFPcp174-CaM1234 (open squares, negative control; n = 25), experimental conditions. Error bars indicate S.E.

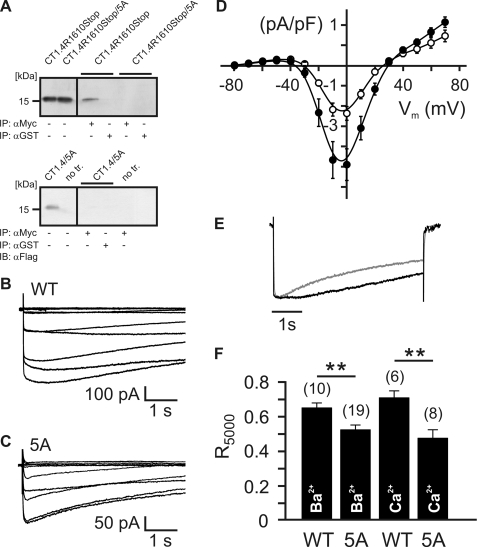

To study the functional effects that CaM exerts on Cav1.4, we generated a Cav1.4 mutant that is deficient for CaM binding (Cav1.4/5A; Fig. 3). In this mutant, five amino acid residues within the IQ motif are replaced by alanines (CT1.4/5A and CT1.4R1610Stop/5A). Indeed, coimmunoprecipitation experiments confirmed that CaM1234 binding to the mutated full-length C terminus (CT1.4/5A) or to CT1.4 that is truncated after the IQ (CT1.4R1610Stop/5A) was totally abolished. As a positive control, we used CT1.4R1610Stop that binds CaM (9). We next compared the electrophysiological properties of wild type Cav1.4 channels with the properties of Cav1.4 channels deficient for CaM (Cav1.4/5A) in HEK293 cells (Fig. 3, B–F). Currents induced for wild type Cav1.4 channels consistently gave higher peak Ba2+ current densities (−4.91 ± 0.79 pA/pF; n = 12) than Cav1.4/5A channels (−2.37 ± 0.34 pA/pF; n = 17; Fig. 3D), indicating that CaM plays a substantial role in controlling the current density. Like wild type channels, Cav1.4/5A channels did not display any CDI (R5000 for IBa, 0.53 ± 0.028; n = 19; R5000 for ICa, 0.48 ± 0.05; n = 8). Surprisingly, IBa through Cav1.4/5A revealed faster voltage-dependent inactivation than IBa through wild type Cav1.4 channel (test pulse, 5 s; Fig. 3, E and F). In contrast, V0.5 was unchanged (Cav1.4/5A, −13.2 ± 0.90 mV; n = 15; Cav1.4, −13.16 ± 1.27 mV; n = 13).

FIGURE 3.

CaM deficient Cav1.4 channels show a reduced current density and a faster voltage-dependent inactivation. A, coimmunoprecipitation (IP) of HEK293 cells coexpressing triple FLAG-tagged CaM1234 together with the proximal C terminus of Cav1.4 in the absence (CT1.4R1610Stop; upper panel) or presence (CT1.4R1610Stop/5A; upper panel) of mutations in the IQ motif or full-length CT1.4/5A (lower panel). Lysates (lanes 1 and 2) were immunoprecipitated with anti-Myc (lanes 3 and 5) or anti-glutathione S-transferase (anti-GST, control), blotted, and probed with anti-FLAG. CaM1234 does not bind to CT1.4/5A or CT1.4R1610Stop/5A (control) but binds to CT1.4R1610Stop (positive control). B, family of IBa traces for Cav1.4 (wild type (WT)). C, family of IBa traces for Cav1.4/5A (5A). Currents were recorded from a holding potential of −80 mV by applying 5-s pulses to membrane voltages between −80 mV and +70 mV. D, mean IV curves of IBa for Cav1.4 (filled circles; n = 12) and Cav1.4/5A (open circles; n = 17). Error bars indicate S.E. E, representative traces of IBa through Cav1.4 (black trace) and Cav1.4/5A (gray trace) evoked by stepping from a holding potential of −80 mV to +10 mV (pulse duration, 5 s). Current traces were normalized to peak current. F, fractional inactivation of IBa or ICa during a 5-s test pulse to Vmax. R5000 corresponds to the fraction of IBa or ICa remaining after 5 s. The number of experiments is given in parentheses. **, p < 0.01.

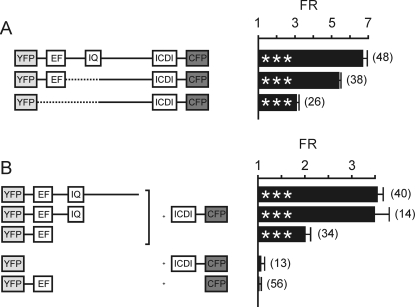

Our functional data suggested that five residues within the IQ motif are critical for CaM binding. Furthermore, Cav1.4 channels deficient for CaM had different properties than wild type Cav1.4, indicating that CaM is a physiological regulator of Cav1.4 channels. Our FRET experiments showed that CaM binds to Cav1.4 in the presence of the ICDI, which strongly suggests that the target sequence for CaM is different from that of the ICDI. To narrow down the target sequence of the ICDI domain, we applied a FRET approach (Fig. 4). To this end, we tagged the complete C terminus of Cav1.4 N-terminally with YFP and C-terminally with CFP. This construct showed pronounced intramolecular FRET (Fig. 4A; FR, 6.60 ± 0.21; n = 48) that is in the order of magnitude reported for YFP-CFP dimers (27) and is five times higher than the FRET signal observed for CaM binding (Fig. 1). Deletion of the sequence downstream of the EF-hand up to the end of the IQ motif only slightly reduced FRET (FR, 5.32 ± 0.09; n = 38), indicating that this sequence stretch is not essential for the binding of the ICDI domain.

FIGURE 4.

ICDI interaction with the C terminus of Cav1.4. A, intramolecular FRET analysis of the complete C terminus of Cav1.4 and C-terminal variants. Left, schematic of the constructs used for coexpression in HEK293 cells. Right, population data of the FR values. Numbers of cells are given in parentheses. B, intermolecular FRET analysis of the binding of the ICDI domain to fragments of the C terminus of Cav1.4. Left, schematic of the constructs. Right, population data of FR. As controls, FR values are given for CFP coexpressed with YFP-EF (control 1) and YFP coexpressed with ICDI-CFP (control 2). ***, p < 0.001 as compared with controls. Note the different scales for FRET ratios in A and B. Error bars indicate S.E.

There are likely to be two main components contributing to intramolecular FRET (35–38). One is the specific binding of the ICDI domain to the proximal C terminus. In addition, the specific folding of the peptide connecting the ICDI and the proximal C terminus could bring the N and the C termini carrying the fluorophores in close vicinity to each other. This effect would be expected to increase the efficiency of the energy transfer between the fluorophores. In support of this latter possibility, an intramolecular FRET construct lacking the proximal C terminus still showed reasonable FRET (FR, 3.03 ± 0.12; n = 26; Fig. 4A). Previously, we excluded biochemically that this construct contains a binding site for the ICDI (9). To circumvent FRET signals arising from intramolecular folding and to quantify the amount of FRET arising from actual binding, we separated YFP-tagged C-terminal fragments and CFP-tagged ICDI containing fragments and coexpressed them in HEK293 cells (Fig. 4B). Indeed, maximal intermolecular FRET observed in HEK293 cells coexpressing YFP-CT1.4ΔICDI and ICDI-CFP was smaller (FR, 3.53 ± 0.12; n = 40) as compared with intramolecular FRET. This observation suggests that approximately half of the intramolecular FRET can be attributed to specific binding. Raising intracellular Ca2+ above resting levels in the presence of endogenous CaM levels did not reduce FRET between YFP-CT1.4ΔICDI and ICDI-CFP (supplemental Fig. S2). It slightly reduced FRET when CaM was coexpressed with YFP-CT1.4ΔICDI and ICDI-CFP (supplemental Fig. S2). Truncation of the C terminus downstream of the IQ motif did not significantly change FRET when coexpressed with ICDI (Fig. 4B). In contrast, coexpression of YFP-EF together with ICDI-CFP reduced FRET. This finding suggests that additional motifs within the proximal C terminus other than the EF-hand contribute to the binding of the ICDI domain.

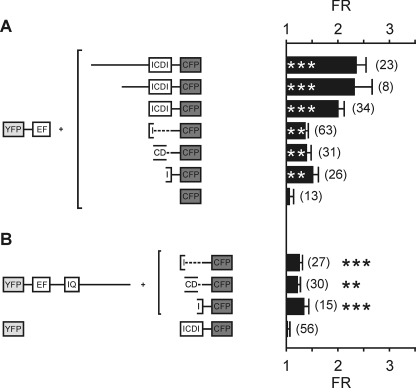

We next set out to narrow down regions within the ICDI required for interaction with the proximal C terminus (Fig. 5). Extension of the ICDI domain did not lead to further increase of FRET binding to the EF-hand, indicating that the core region of the ICDI domain is sufficient for binding (Fig. 5A). In contrast, dividing the ICDI domain into three parts significantly reduced the FRET signal as compared with CFP-tagged fragments containing the complete ICDI (Fig. 5A). This indicates that all three parts contribute to an interaction surface with the proximal C terminus and that splitting the ICDI domain destroys its binding ability. Furthermore, FRET was not increased when the full C terminus only lacking the ICDI domain was used as acceptor for the ICDI domain (Fig. 5B).

FIGURE 5.

Regions within the ICDI required for interaction with the proximal C terminus of Cav1.4. A, FRET between C-terminal fragments containing the complete ICDI domain or variants of the ICDI domain (broken boxes) and the EF motif. B, FRET between fragments of the ICDI and CT1.4ΔICDI. Controls are as described in the legend for Fig. 4. *, p < 0.05, **, p < 0.01,***, p < 0.001 as compared with control. Error bars indicate S.E.

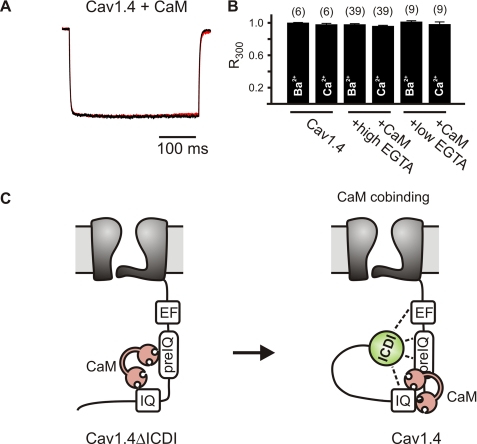

To functionally test whether CaM and the ICDI domain interfere with each other, Cav1.4 channels were coexpressed with CaM, and Ba2+ and Ca2+ currents were recorded. If so, it should be possible to displace the ICDI domain by CaM overexpression and reconstitute CDI. Fig. 6, A and B show that there was no change in current kinetics and no development of CDI even with extreme high amounts of CaM regardless of the Ca2+ buffering condition used. This finding strongly supports our FRET experiments arguing against a competitive mechanism.

FIGURE 6.

ICDI does not suppress CDI by competing with calmodulin for the channel. A and B, overexpression of CaM and Cav1.4 does not induce CDI. A, representative peak IBa (black trace) and ICa (red trace), demonstrating the lack of CDI. B, population data of R300 values for IBa and ICa for Cav1.4 in the absence and the presence of CaM overexpression with either high or low intracellular Ca2+ buffering by EGTA as indicated. Error bars indicate S.E. C, left, binding of CaM to the C terminus of Cav1.4 lacking the ICDI domain (Cav1.4ΔICDI). Right, CaM cobinding model. In wild type Cav1.4 channels, CaM binds to a target sequence in the proximal C terminus of Cav1.4, and binding of CaM is not prevented in the presence of the ICDI domain. The steric orientation of the CaM/Cav1.4 complex differs in the presence (right) and the absence (left) of the ICDI domain. The ICDI domain interacts with the EF-hand and other motifs in the proximal C terminus. The interaction with the EF-hand switches off CDI. Other CaM-dependent effects (VDI and current density) are still present. Motifs previously demonstrated to be important for CaM-dependent modulation of other L-type and neuronal Ca2+ channels (EF-hand, pre-IQ, IQ segment) are indicated. CaM is shown in red, and the ICDI domain is shown in green.

DISCUSSION

Here, we provide evidence that the ICDI domain and CaM bind to different portions of the proximal C terminus and act independently of each other (Fig. 6C, right). Using FRET experiments, we found that the ICDI binds to the EF-hand motif and downstream sequence of the proximal C terminus. Given the central role of the EF-hand within the framework of CDI (12–16), we suggest that it is mainly the interaction with the EF-hand that effectively switches off all downstream signaling events required for CDI. In line with this hypothesis, intramolecular FRET experiments indicate that in the context of the complete C terminus, the EF-hand may be the most important target of the ICDI domain. Furthermore, we provide evidence that different parts of the ICDI domain contribute to binding to the EF-hand. Additional binding of the ICDI to a single binding site or multiple binding sites described for apoCaM or Ca2+/CaM within the IQ and upstream of the IQ (39, 40) could interfere with the translocation of preassociated CaM to the effector site(s). Currently, it is not known exactly how CaM binding to each of these individual regions contributes to CDI. Alternatively, binding of the ICDI could clamp CaM at the preassociation site in a fixed position that does not permit translocation to free effector sites and/or that does not permit conformational changes required for CDI. In all these settings, preassociated CaM would have much less degree of freedom to change conformation or move to effector sites in the presence of the ICDI domain (Cav1.4) than in its absence (Cav1.4ΔICDI or Cav1.2). Our finding that the detection of FRET between CaM and Cav1.4 depends on steric orientation would be in favor of slightly different structure of the channel-CaM complex as compared with Cav1.2.

Based on different FRET approaches, we show that CaM binds to the C terminus of Cav1.4 and that binding of CaM is not prevented in the presence of the ICDI (Fig. 6C, right). The range of FRET ratios determined for CaM (1.4–2.3) is within the range reported for other HVA Ca2+ channels with the same method (24, 27). This indicates that our FRET approach is suitable to reliably measure CaM interaction with Ca2+ channels. Although CaM binding to the C terminus of Cav1.2 and Cav1.4ΔICDI was easily detected regardless of the CFP variant used, binding to the C terminus of Cav1.4 was only detectable with CFPcp174-CaM and CFPcp174-CaM1234. This finding indicates that in Cav1.4, but not in Cav1.2, structural constraints are present in the steric environment of the CaM binding region. This could explain why, in a recent study, CaM binding to Cav1.4 (10) or to a chimeric Cav1.3 C terminus containing the ICDI domain (41) was not detected. The FRET signal between CaM and the C terminus of Cav1.4 increased in parallel to the elevation of intracellular Ca2+. The time course of this FRET signal was identical for the C terminus of Cav1.4 and Cav1.2. This result is consistent with a Ca2+-dependent conformational change of preassociated CaM (16, 24, 39, 40, 42) rather than an increase in actual binding of cytosolic CaM (24). Our data indicate that this Ca2+-dependent conformational change only slightly, if at all, interferes with the binding of the ICDI domain. Considering that FRET was only slightly reduced (about 1%; supplemental Fig. S2) when CaM was coexpressed with YFP-CT1.4ΔICDI and ICDI-CFP, and considering that baseline FR was very high (about 3.5; Fig. 4B), it is very unlikely that this change is functionally relevant. This hypothesis is strongly supported by the Cav1.4 current recordings in the presence of CaM overexpression (see below).

Functional experiments support our FRET results. Electrophysiological experiments suggest that the target sequence for CaM is different from that of the ICDI because overexpression of CaM did not induce CDI. Using the Cav1.4/5A mutant, we found that five residues within the IQ motif are critical for CaM binding. Most importantly, we identified distinct Cav1.4 channel functions that clearly depend on CaM preassociation. Cav1.4 channels lacking CaM binding consistently yield lower current densities as compared with wild type channels. These findings could be the result of an impaired trafficking to the plasma membrane. Although we cannot completely exclude a CaM-independent mechanism, it is very likely that CaM binding to the IQ domain masks an endoplasmic reticulum retention signal within this domain as proposed for Cav1.2 (43). In Cav1.2, such a mechanism regulates trafficking to distal dendrites in hippocampal neurons (44). Furthermore, our data clearly indicate that CaM plays a role in the regulation of VDI in Cav1.4.

CDI is a hallmark of classical HVA Ca2+ channels. In Cav1.4, CDI is switched off by the ICDI domain. Our data show that CaM is bound to Cav1.4 and serves as a functional regulator of the channel. Specifically, we found that CaM is an important regulator for channel trafficking and VDI. It is very likely that CaM preassociation also regulates other physiological functions of Cav1.4. For example, in Cav1.2, CaM preassociation at the IQ motif seems to be essential for signaling to the nucleus and triggering of gene transcription (18). It is tempting to speculate that retinal network activity is regulated in a similar fashion by Cav1.4-dependent gene expression.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank David Yue for help in establishing the three-cube FRET.

This work was supported by a grant from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1 and S2.

- HVA

- high voltage-activated

- CDI

- Ca2+-dependent inactivation

- VDI

- voltage-dependent inactivation

- ICDI

- inhibitor of CDI

- CaM

- calmodulin

- FRET

- fluorescence resonance energy transfer

- FR

- FRET ratio

- YPF

- yellow fluorescent protein

- CFP

- cyan fluorescent protein

- pF

- picofarads.

REFERENCES

- 1.Thoreson W. B. (2007) Mol. Neurobiol. 36, 205–223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Juusola M., French A. S., Uusitalo R. O., Weckström M. (1996) Trends Neurosci. 19, 292–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mansergh F., Orton N. C., Vessey J. P., Lalonde M. R., Stell W. K., Tremblay F., Barnes S., Rancourt D. E., Bech-Hansen N. T. (2005) Hum. Mol. Genet 14, 3035–3046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haeseleer F., Imanishi Y., Maeda T., Possin D. E., Maeda A., Lee A., Rieke F., Palczewski K. (2004) Nat. Neurosci. 7, 1079–1087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barnes S., Kelly M. E. (2002) Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 514, 465–476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bech-Hansen N. T., Naylor M. J., Maybaum T. A., Pearce W. G., Koop B., Fishman G. A., Mets M., Musarella M. A., Boycott K. M. (1998) Nat. Genet. 19, 264–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Strom T. M., Nyakatura G., Apfelstedt-Sylla E., Hellebrand H., Lorenz B., Weber B. H., Wutz K., Gutwillinger N., Rüther K., Drescher B., Sauer C., Zrenner E., Meitinger T., Rosenthal A., Meindl A. (1998) Nat. Genet. 19, 260–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doering C. J., Peloquin J. B., McRory J. E. (2007) Channels (Austin) 1, 3–10 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wahl-Schott C., Baumann L., Cuny H., Eckert C., Griessmeier K., Biel M. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 15657–15662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singh A., Hamedinger D., Hoda J. C., Gebhart M., Koschak A., Romanin C., Striessnig J. (2006) Nat. Neurosci. 9, 1108–1116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mori M. X., Vander Kooi C. W., Leahy D. J., Yue D. T. (2008) Structure 16, 607–620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zühlke R. D., Reuter H. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 3287–3294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pitt G. S., Zühlke R. D., Hudmon A., Schulman H., Reuter H., Tsien R. W. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 30794–30802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bernatchez G., Talwar D., Parent L. (1998) Biophys. J. 75, 1727–1739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peterson B. Z., Lee J. S., Mulle J. G., Wang Y., de Leon M., Yue D. T. (2000) Biophys. J. 78, 1906–1920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim J., Ghosh S., Nunziato D. A., Pitt G. S. (2004) Neuron 41, 745–754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baumann L., Gerstner A., Zong X., Biel M., Wahl-Schott C. (2004) Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 45, 708–713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dolmetsch R. E., Pajvani U., Fife K., Spotts J. M., Greenberg M. E. (2001) Science 294, 333–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van Petegem F., Chatelain F. C., Minor D. L., Jr. (2005) Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 12, 1108–1115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fallon J. L., Halling D. B., Hamilton S. L., Quiocho F. A. (2005) Structure 13, 1881–1886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zacharias D. A., Violin J. D., Newton A. C., Tsien R. Y. (2002) Science 296, 913–916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tsien R. Y. (1998) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 67, 509–544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Biel M., Ruth P., Bosse E., Hullin R., Stühmer W., Flockerzi V., Hofmann F. (1990) FEBS Lett. 269, 409–412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Erickson M. G., Liang H., Mori M. X., Yue D. T. (2003) Neuron 39, 97–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liang H., DeMaria C. D., Erickson M. G., Mori M. X., Alseikhan B. A., Yue D. T. (2003) Neuron 39, 951–960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miyawaki A., Llopis J., Heim R., McCaffery J. M., Adams J. A., Ikura M., Tsien R. Y. (1997) Nature 388, 882–887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Erickson M. G., Alseikhan B. A., Peterson B. Z., Yue D. T. (2001) Neuron 31, 973–985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Erickson M. G., Moon D. L., Yue D. T. (2003) Biophys. J. 85, 599–611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mank M., Reiff D. F., Heim N., Friedrich M. W., Borst A., Griesbeck O. (2006) Biophys. J. 90, 1790–1796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xia X. M., Fakler B., Rivard A., Wayman G., Johnson-Pais T., Keen J. E., Ishii T., Hirschberg B., Bond C. T., Lutsenko S., Maylie J., Adelman J. P. (1998) Nature 395, 503–507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mank M., Santos A. F., Direnberger S., Mrsic-Flogel T. D., Hofer S. B., Stein V., Hendel T., Reiff D. F., Levelt C., Borst A., Bonhoeffer T., Hübener M., Griesbeck O. (2008) Nat. Methods 5, 805–811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baird G. S., Zacharias D. A., Tsien R. Y. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 11241–11246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Topell S., Hennecke J., Glockshuber R. (1999) FEBS Lett. 457, 283–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nagai T., Yamada S., Tominaga T., Ichikawa M., Miyawaki A. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 10554–10559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pedersen M., Carmosino M., Forbush B. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 2663–2674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mc Intyre J., Muller E. G., Weitzer S., Snydsman B. E., Davis T. N., Uhlmann F. (2007) EMBO J. 26, 3783–3793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang L., Bittner M. A., Axelrod D., Holz R. W. (2008) Mol. Biol. Cell 19, 3944–3955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schaufele F., Carbonell X., Guerbadot M., Borngraeber S., Chapman M. S., Ma A. A., Miner J. N., Diamond M. I. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 9802–9807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Halling D. B., Aracena-Parks P., Hamilton S. L. (2005) Sci. STKE 2005, re15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Van Petegem F., Minor D. L., Jr. (2006) Biochem. Soc. Trans. 34, 887–893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Singh A., Gebhart M., Fritsch R., Sinnegger-Brauns M. J., Poggiani C., Hoda J. C., Engel J., Romanin C., Striessnig J., Koschak A. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 20733–20744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fallon J. L., Quiocho F. A. (2003) Structure 11, 1303–1307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Michelsen K., Yuan H., Schwappach B. (2005) EMBO Rep. 6, 717–722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang H. G., George M. S., Kim J., Wang C., Pitt G. S. (2007) J. Neurosci. 27, 9086–9093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.