Abstract

Membrane-type 1 matrix metalloproteinase 1 (MT1-MMP) is a potent modulator of the pericellular microenvironment and regulates cellular functions in physiological and pathological settings in mammals. MT1-MMP mediates its biological effects through cleavage of specific substrate proteins. However, our knowledge of MT1-MMP substrates remains limited. To identify new substrates of MT1-MMP, we purified proteins associating with MT1-MMP in human epidermoid carcinoma A431 cells and analyzed them by mass spectrometry. We identified 163 proteins, including membrane proteins, cytoplasmic proteins, and functionally unknown proteins. Sixty-four membrane proteins were identified, and they included known MT1-MMP substrates. Of these, eighteen membrane proteins were selected, and we confirmed their association with MT1-MMP using an immunoprecipitation assay. Co-expression of each protein together with MT1-MMP revealed that nine proteins were cleaved by MT1-MMP. Lutheran blood group glycoprotein (Lu) is one of the proteins cleaved by MT1-MMP, and we confirmed the cleavage of the endogenous Lu protein by endogenous MT1-MMP in A431 cells. Mutation of the cleavage site of Lu abrogated processing by MT1-MMP. Lu protein expressed in A431 cells bound to laminin-511, and knockdown of MT1-MMP in these cells increased both their binding to laminin-511 and the amount of Lu protein on the cell surface. Thus, the identified membrane proteins associated with MT1-MMP are an enriched source of physiological MT1-MMP substrates.

Cells in tissues are surrounded by an extracellular cellular matrix that interacts with cells to regulate their activity (1, 2). Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs)3 are endopeptidases responsible for extracellular matrix degradation and thereby regulate turnover of the extracellular matrix. However, recent studies have demonstrated that substrates of MMPs are expanded to a variety of pericellular proteins.

MT1-MMP/MMP14 is an integral membrane proteinase that cleaves multiple proteins in the pericellular milieu and thereby regulates various cell functions. Substrates of MT1-MMP identified to date include extracellular matrix proteins (type I collagen, fibronectin, vitronectin, laminin-1 and -5, and others), cell adhesion molecules (CD44, syndecan-1, and αv integrin), cytokines (SDF-1 and transforming growth factor-β and others), and latent forms of pro-MMPs (pro-MMP-2 and pro-MMP13) (3–5). Processing of these proteins by MT1-MMP alters their activities and thereby regulates a variety of cellular functions, such as motility, invasion, growth, differentiation, and apoptosis. Consistent with these functions, forced expression of MT1-MMP in tumor cells enhances behavior consistent with increased malignancy, such as rapid tumor growth, invasion, and metastasis (6). However, MT1-MMP is normally expressed in various types of cell and mice deficient in MT1-MMP expression (MT1−/−) display pleiotropic defects (7–10). However, we as yet have only limited knowledge of the physiological substrates of MT1-MMP that could explain such pleiotropic effects.

Proteases interact with their substrates at least transiently, but in some cases such interaction is more stable. For instance, type I collagen binds MT1-MMP via a hemopexin-like domain and is cleaved (11, 12). Cleavage of collagen by MT1-MMP regulates cell growth and invasion in a collagen-rich environment (13). CD44, a hyaluronic acid receptor, also binds to the hemopexin of MT1-MMP and is cleaved (14). Expression of CD44 and MT1-MMP in tumor cells promotes cell migration, accompanied by the shedding of CD44 by MT1-MMP (14, 15). pro-MMP-2, which is cleaved by MT1-MMP for activation, forms a tri-molecular complex with MT1-MMP and TIMP-2 (3, 16). Therefore, screening of proteins that associate with MT1-MMP may provide a systematic method to identify potential substrates of MT1-MMP in cells. In addition, these proteins may also be regulatory proteins of MT1-MMP.

To identify proteins associating with MT1-MMP in different types of tumor cells, we first studied conditions for cell lysis using malignant melanoma A375 cells and following purification method of the proteins as reported recently (17). Proteins purified in this manner were analyzed by high-throughput proteomic analysis (18–21). Interestingly, approximately one-half of the membrane proteins identified in our previous study could be cleaved by MT1-MMP at least in vitro. Here, we applied this approach to human carcinoma cells (A431) that originate from epidermoid cells and further validated the systemic whole cell analysis method. To evaluate whether the MT1-MMP-associated membrane proteins so identified include physiological targets of MT1-MMP activity, we select one of them, Lutheran blood group glycoprotein (Lu), and evaluate its processing in A431 cells.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Culture Cells

The human epidermoid carcinoma cell line A431 was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA), and the African green monkey kidney cell line COS-7 was obtained from Health Science Research Resources Bank (Osaka, Japan).

Construction of Expression Vectors

MT1-MMP constructs were prepared as previously described (14). Catalytically inactive MT1-MMP mutant (MT1 E/A) has a substitution of Ala for Glu240 in the active site as reported previously (22). A cDNA sequence corresponding to the open reading frame of human Lu was amplified using PCR. Expression constructs for C-terminally FLAG-tagged Lu were generated as previously described using the Gateway system (Invitrogen) (23). Transfection was performed using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. For inducible expression of wild-type or catalytically inactive MT1-MMP mutant (MT1 E/A) in A431 cells we used the RevTet-OffTM Gene Expression Systems (Clontech) according to the manufacturer's instructions. MMI270 (a synthetic hydroxamic MMP inhibitor, a kind gift of Novartis Pharma AG, Basel, Switzerland) (24) was added when the medium was changed 24 h after transfection.

Isolation of MT1-MMP-associated Proteins by FLAG Affinity Chromatography

A431 cells that stably expressed FLAG-tagged MT1-MMP were gently lysed by a lysis buffer containing 1% (w/v) Brij-98 as described previously (17). Lysate containing the FLAG-tagged MT1-MMP was subjected to affinity purification using a column packed with agarose beads conjugated to the anti-FLAG M2 antibody. Proteins bound to the column were eluted with successive fractions of buffer containing increasing concentrations of NaCl followed by elution buffer containing FLAG peptide (17). To label the cell surface proteins with biotin, cells were incubated with sulfo-LC-NHS-biotin (Pierce) at 0.1 mg/ml for 30 min at 4 °C. The reaction was terminated by washing three times with phosphate-buffered saline (+).

Identification of MT1-MMP-associated Proteins by LC/ MS/MS

The eluted fractions were digested with endoproteinase Lys-C, and subjected to Nano-Flow liquid chromatography (nano-LC), which was linked online to tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS). The details of the system were previously described (17). All MS/MS spectra were correlated with a search engine, Mascot program (Matrix Science), against the non-redundant protein sequence data base at the National Center for Biotechnology Information. We followed the criteria used for match acceptance as described previously (21). When the match scores exceeded 10 above the threshold, identifications were accepted without further consideration. When scores were lower than 10 or identifications were based on single matched MS/MS spectra, we manually inspected the raw data for confirmation prior to acceptance. Peptides assigned by less than three y series ions and those with a +4 charge state were all eliminated regardless of scores.

Immunoprecipitation

Immunoprecipitation of cell lysates prepared with RIPA buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mm NaCl, 1% (v/v) Nonidet P-40, 0.5% (v/w) sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% (v/w) SDS) and using agarose beads conjugated to an anti-FLAG M2 antibody was performed as previously described (23).

Western Blot Analysis

Proteins in the conditioned medium were precipitated with 10% (v/w) trichloroacetic acid, and prepared for SDS-PAGE. Total cell lysates (trichloroacetic acid), immunoprecipitated products, proteins in the conditioned medium, and purified laminin-511 were separated by SDS-PAGE under reducing or non-reducing conditions. Western blot analysis was performed as previously described (23). Primary antibodies included an anti-human MT1-MMP mouse monoclonal antibody (222-1D8, Daiichi-fine-Chemical, Takaoka, Japan), an anti-FLAG M2 mouse monoclonal antibody, an anti-FLAG rabbit polyclonal antibody (Sigma), an anti-human Lu goat polyclonal antibody (AF148, R & D Systems), an anti-c-Myc mouse monoclonal antibody (Roche Applied Science), an anti-FAS Ligand mouse monoclonal antibody (BD Biosciences), an anti-transferrin receptor mouse monoclonal antibody (Invitrogen), and an anti-CD44 rabbit polyclonal antibody (prepared as previously described (14)). The secondary antibodies were horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (Amersham Biosciences). The ECL Plus Western blot detection system (Amersham Biosciences) was used for development of the blots.

Purification of Recombinant Laminin-511

We established HEK293 cells expressing laminin α5 (C-FLAG-tagged), β1 and γ1 (25). Purification of recombinant laminin-511 was performed as previously described (26).

FACS Analysis

Cells were incubated on ice with the primary antibody followed by the secondary antibody for 30 min each. In the laminin-511 binding assay, cells were incubated with 20 μg/ml purified laminin-511 on ice for 30 min prior to application of the primary antibody. Samples were analyzed with FACS Aria (BD Biosciences). The primary antibodies used were an anti-human Lu mouse monoclonal antibody (BRIC221) (AbD), an anti-FLAG M2 mouse monoclonal antibody (Sigma). The secondary antibodies used were an Alexa 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG, an Alexa 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG, and an Alexa 488-conjugated goat anti-rat IgG (Invitrogen).

Stable Knockdown of Lu by shRNA

The entry and destination vectors were generated according to the manufacturer's instruction using a BLOCK-it U6 Entry Vector Kit and the Gateway system (Invitrogen). Lu knockdown cells were established using the Virapower lentiviral expression system (Invitrogen), and the cells were maintained in the presence of 10 μg/ml blasticidin (Invitrogen).

Transient Knockdown of MT1-MMP by RNA Interference

Small interfering RNA (siRNA) targeting MT1-MMP mRNA was designed and prepared by B-Bridge (Sunnyvale, CA), and transfection was carried out using Lipofectamine RNAi MAX Reagent (Invitrogen). The conditioned medium or cells were harvested 72 h after transfection.

RESULTS

Inducible Expression of MT1-MMP in A431 Cells

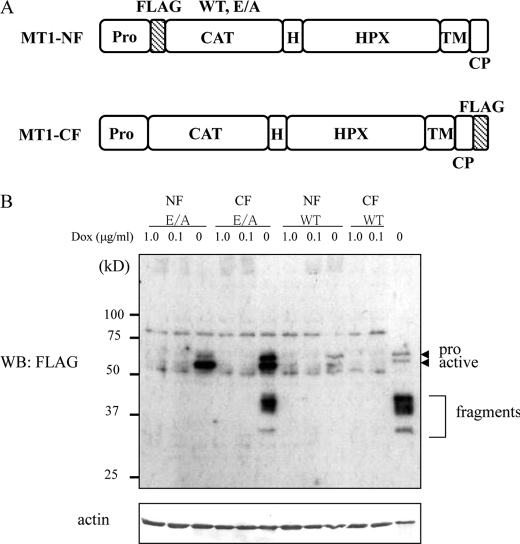

To isolate proteins associating with MT1-MMP, we first prepared tetracycline-inducible expression constructs for MT1-MMP FLAG-tagged at either the N (MT1-NF) or C terminus (MT1-CF) (Fig. 1A). To prevent the possible degradation of protein components in the complex by the proteolytic activity of MT1-MMP, we used a catalytically inactive mutant (E/A) containing an amino acid substitution from Glu240 to Ala (E/A) in the catalytic site (22). The viral vectors encoding the tagged MT1-MMPs were transduced into A431 cells as described under “Experimental Procedures,” and stable clones were isolated. Expression of MT1-MMP was induced by the depletion of doxycycline (Dox) in the culture medium, and the identities of the MT1-MMP proteins were confirmed by Western blot analysis using anti-FLAG antibody. We detected both pro and active forms of MT1-MMP (Fig. 1B, pro and active, respectively). An excessive amount of MT1-MMP to the endogenously expressed protein was induced as presented in supplemental Fig. S1. Protein fragments corresponding to those predicted by autodegradation of MT1-MMP were detected even in cells expressing the E/A mutant (Fig. 1B, fragment), presumably because A431 cells express endogenous MT1-MMP (refer to Fig. 5B).

FIGURE 1.

Inducible expression of FLAG-tagged MT1-MMP in A431 cells. A, schematic illustration of MT1-MMP proteins tagged with FLAG. NF, N-terminally FLAG-tagged; CF, C-terminally FLAG-tagged; WT, wild type; E/A, catalytically inactive mutant; Pro, Propeptide; FLAG, FLAG epitope; CAT, catalytic domain; H, hinge domain; HPX, hemopexin-like domain; TM, transmembrane domain; CP, cytoplasmic domain. B, stable transfectants of A431 expressing an inducible system for MT1-NF (WT and E/A) or MT1-CF (WT and E/A) were cultured in the absence, or presence of 0.1 or 1.0 μg/ml doxycycline (Dox) for 4 days. Total cell lysates were prepared and subjected to Western blot analysis using anti-FLAG M2 antibody. Pro and active forms of MT1-MMP are indicated together with the degraded forms.

FIGURE 5.

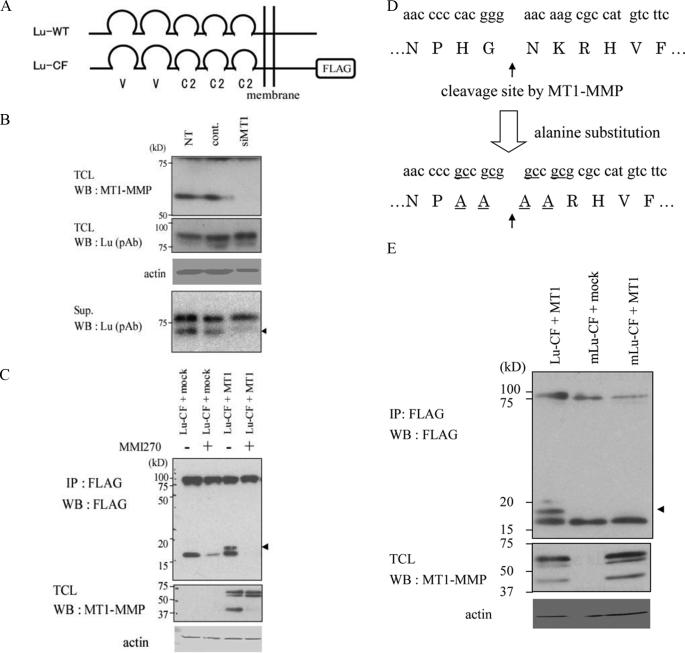

Processing of Lu by endogenous MT1-MMP in A431 cells. A, domain structure of Lu protein. Lu comprises five Ig-like domains within its extracellular region, a transmembrane domain, and a cytoplasmic tail. C-terminally FLAG-tagged Lu (Lu-CF) is also presented. B, shedding of Lu fragments in A431 cells. Proteins in the conditioned medium of A431 cells treated with the indicated siRNA were collected and analyzed by Western blot analysis (bottom panel) using a polyclonal antibody against the extracellular portion of Lu (Lu (pAb)). NT, non-treated; cont., control siRNA; siMT1, siRNA for knockdown of MT1-MMP. Total cell lysates were examined by Western blot analysis using anti-MT1-MMP antibody (top panel), Lu (pAb) (second panel), and anti-actin antibody (third panel). Knockdown of MT1-MMP in the cells diminished the amount of the shed Lu fragment with smaller apparent molecular weight (arrowhead). C, processing of Lu-CF by MT1-MMP in COS-7 cells. Lu-CF and MT1-MMP (MT1) were expressed in the cells in the indicated combinations, and cell lysates were analyzed by immunoprecipitation followed by Western blot analysis using anti-FLAG antibody. Total cell lysate (TCL) were examined for MT1-MMP expression using anti-MT1-MMP antibody. D, amino acid sequence of the cleavage site and design of a non-cleavable Lu mutant (mLu-CF). Two amino acids flanking the original Lu cleavage site were substituted by alanine. E, processing of mLu-CF was tested in COS-7 cells and analyzed by immunoprecipitation/Western blotting using an anti-FLAG antibody. The fragment processed by MT1-MMP is indicated by an arrowhead.

Affinity Purification of the FLAG-tagged MT1-MMP

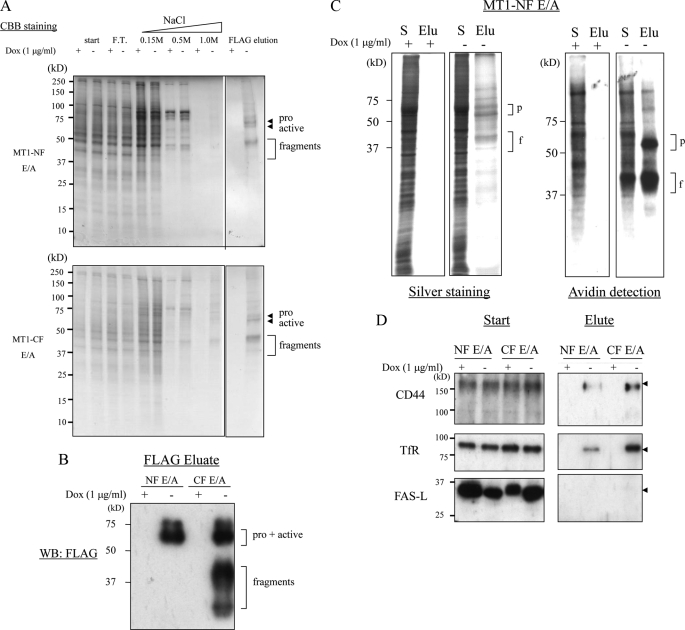

We examined different detergents for preparation of the cell lysate and determined to use Brij-98, because this reagent does not disrupt the reported association between MT1-MMP and CD44 (14, 27). Cleared lysate was applied to an affinity column packed with agarose beads conjugated to an anti-FLAG M2 antibody (refer to “Experimental Procedures” for a detailed purification procedure). The column was washed with increasing concentrations of NaCl, and finally the proteins bound to the beads were eluted with a FLAG peptide. Aliquots of each step sample were examined by Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining after SDS-PAGE (Fig. 2A). Most of the proteins that were nonspecifically retained in the column were eluted with washing buffer containing 0.5 m NaCl. The major polypeptides detected by Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining in the final elution fraction corresponded to MT1-MMP, because they could be detected by Western blot analysis using an anti-FLAG antibody (Fig. 2B). Unexpectedly, we observed autodegraded MT1-MMP fragments in the final FLAG eluate fraction even when we used cells expressing MT1-NF (Fig. 2A). We speculate that this is due to the ability of MT1-MMP to form homophilic dimers through the hemopexin-like domain (HPX), as we reported previously (22).

FIGURE 2.

Affinity purification of MT1-MMP expressed in A431 cells. A, A431 cells expressing MT1-NF (E/A) or MT1-CF (E/A) were cultured in the presence (+) or absence (−) of doxycycline (Dox) for 4 days. Cells were lysed with Brij-98 and the lysates (start) were applied to an anti-FLAG antibody affinity column and washed with lysis buffer containing 0.15, 0.5, and 1.0 m NaCl, and finally eluted with FLAG peptide (FLAG elution). Aliquots of each fraction were analyzed by SDS-PAGE, and proteins were stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250 (CBB). F.T., flow through. B, MT1-NF and MT1-CF in the final eluate were confirmed by Western blot analysis using anti-FLAG M2 antibody. C, detection of MT1-NF E/A-associating proteins. Left panels show silver staining of the proteins in the original cell lysate (S) and the final elution fractions (Elu). Right panels show detection of cell surface proteins labeled with biotin. Positions corresponding to the predicted molecular weights of the pro and active forms of MT1-MMP (p), and the degraded fragments (f) are indicated. D, analysis of the interaction of MT1-MMP with known interactors (CD44 and transferrin receptor, TfR), and a negative control, FAS ligand (FAS-L). Proteins in the cell lysates and final column eluate were analyzed by Western blot analysis. Arrowheads indicate the specific signals corresponding to each protein.

Multiple proteins in the final elution became visible with silver staining (Fig. 2C, left). The proteins that eluted with MT1-MMP showed a distinct pattern from that of the starting material. Almost no proteins were detected in the elution fraction from lysates prepared from non-induced cells (Dox(+)). We further examined whether a specific set of membrane proteins eluted with MT1-MMP by labeling them with biotin prior to cell lysis and affinity purification. The labeled proteins were detected by Western blot analysis using Avidin-horseradish peroxidase (Fig. 2C, right). Only a distinct subset of cell surface proteins eluted with MT1-MMP.

We next subjected the membrane proteins that eluted with MT1-MMP to Western blot analysis using antibodies specific for CD44 and the transferrin receptor, which have both been reported to interact with MT1-MMP (Fig. 2D) (14, 15). We detected both CD44 and transferrin receptor in the elution fractions prepared from the induced cells. We also probed the blots for FAS ligand (FAS-L), which has not been reported to associate with MT1-MMP, and we were unable to detect its presence. These results suggest that the proteins in the final elution represent those that associate with MT1-MMP.

Identification of Proteins using High Throughput MS

To identify the proteins associating with MT1-MMP, the final elution fractions for MT1-NF (E/A) and MT1-CF (E/A) were digested with endoproteinase Lys-C and subjected to nano-flow liquid chromatography (nano-LC). The separated peptide fragments were automatically subjected to tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) connected to the nano-LC and analyzed using the Mascot program. The validity of each high scoring peptide sequence was confirmed by manual inspection of the corresponding MS/MS spectrum (refer to “Experimental Procedures”). In total, 163 proteins were identified as MT1-MMP-associating proteins (supplemental Table S1), and these were classified into membrane, cytoplasmic, secretory, and unknown proteins (Table 1A). The 64 membrane proteins included adhesion molecules, receptors, transporters, and others (Table 1B). These proteins included known MT1-MMP substrates such as CD44 (14, 15) and EMMPRIN (23).

TABLE 1.

Classifications of MT1-MMP-associating proteins by localization (A) and MT1-MMP-associating membrane proteins by those functions (B)

163 proteins identified by LC/MS/MS were classified into four groups according to cellular localization; membrane, cytoplasmic, secretory proteins and unknown proteins. Representative of membrane proteins are further classified into adhesion molecules, receptors, transporters, and other functional proteins and listed here. The accession number of each protein in the NCBI database is indicated as NM_00xx.

| A) Classification of MT1-MMP-associating proteins by localization | |

| Membrane proteins | 64 |

| Cytoplasmic proteins | 87 |

| Secretory proteins | 5 |

| Uncharacterized proteins | 7 |

| Total | 163 |

| B) Classification of MT1-MMP-associating membrane proteins by those functions | |

| Adhesion molecules | NM_001728, EMMPRIN |

| NM_006505, poliovirus receptor | |

| NM_005581, Lu | |

| NM_002211, β1 integrin | |

| NM_000610, CD44 | |

| Receptors | NM_005228, EGFR |

| NM_003234, transferrin receptor | |

| Transporters | NM_002394, CD98 |

| Others | NM_001769, CD9 |

| NM_006670, 5T4 antigen | |

| NM_001304, carboxypeptidase D | |

Analysis of the Membrane Proteins Co-purified with MT1-MMP

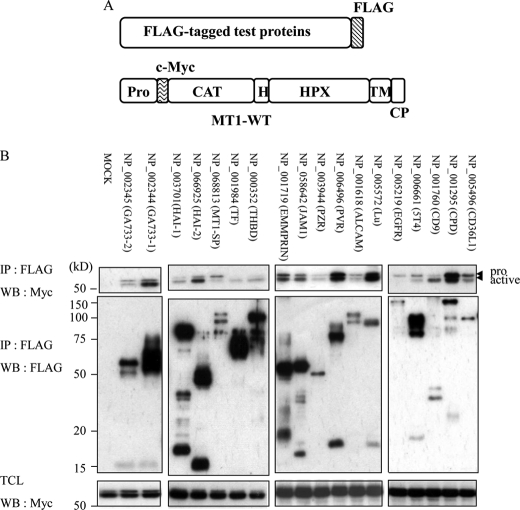

We chose 18 proteins randomly from the 64 membrane proteins and constructed vectors expressing FLAG-tagged versions of each interacting protein (Fig. 3A). We evaluated binding of these FLAG-tagged proteins to MT1-MMP by first co-expressing them individually along with Myc-tagged MT1-MMP in A431 cells. Lysates prepared from the transfected cells were then subjected to immunoprecipitation followed by Western blot analysis. We confirmed co-precipitation of MT1-MMP with each of the 18 selected test proteins (Fig. 3B) as it is expected from co-elution of the test proteins with MT1-MMP from the affinity columns. Interestingly, the ratio of pro and active forms of MT1-MMP that co-precipitated with the test proteins differed for each test protein. This may reflect the subcellular localization of the test proteins that interact with MT1-MMP.

FIGURE 3.

Co-expression and immunoprecipitation analysis of the newly identified binding partners of MT1-MMP. A, schematic illustration of the test proteins tagged with FLAG at the C terminus and MT1-MMP tagged with c-Myc at the N terminus (MT1-WT). B, the indicated test proteins were individually transiently co-expressed in A431 cells together with MT1-WT. Immunoprecipitation of the test proteins was carried out using anti-FLAG antibody. The immunoprecipitates were subjected to Western blot analysis using anti-Myc antibody (top panels) or anti-FLAG antibody (middle panels). MT1-MMP in the total cell lysate was detected by Western blot analysis (lower panels). The accession number of each test protein in the NCBI data base is indicated in the figure.

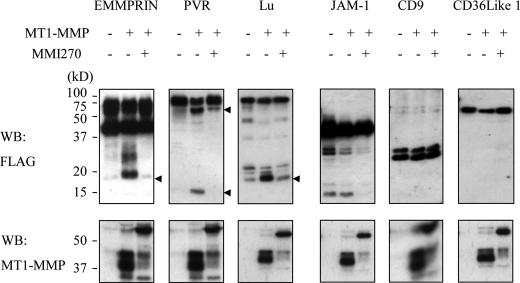

Some of these membrane proteins might be cleaved by MT1-MMP. To test this possibility, we co-expressed each of these proteins together with MT1-MMP in A431 cells. Indeed, co-expression of MT1-MMP and the test proteins generated new cleavage fragments in nine cases, and this fragmentation was inhibited by incubation of the cells with a synthetic MMP inhibitor, MMI270. Six representative cases are presented in Fig. 4, and the other twelve cases are presented in supplemental Fig. S2. Processing of JAM-1 was not affected by expression of MT1-MMP, although its processing can be inhibited by MMI270. These results indicate that approximately half of the identified membrane proteins can be cleaved by MT1-MMP when both proteins were overexpressed in A431 cells.

FIGURE 4.

Changes in the apparent molecular weights of the test proteins by MT1-MMP. FLAG-tagged test proteins were expressed in A431 cells in the absence (−) or presence of MT1-MMP expression (+). The cells were also treated with MMI270, a synthetic MMP inhibitor. The test proteins in the cells were detected by Western blot analysis (upper panels). Protein bands shifted by MT1-MMP expression are indicated by arrowheads. Expression of MT1-MMP in the cells is demonstrated in the lower panels. Results with 6 of 18 proteins are shown (refer to supplemental Fig. S2 for the other 12 proteins).

Processing of Lu Protein by MT1-MMP

To confirm processing of the test proteins by MT1-MMP in a more physiological condition, we focused on the Lu protein expressed in A431 cells. Lu is a transmembrane glycoprotein belonging to the immunoglobulin superfamily, comprises two variable and three constant Ig-like domains in its extracellular region (Fig. 5A), and has been reported to bind laminin-511 (previously called laminin-10) (26, 28, 29). A431 cells express an 85- kDa endogenous Lu protein and shed fragments of 76 and 74 kDa into the culture media (Fig. 5B). Shedding of the smaller fragment was specifically decreased by knockdown of MT1-MMP expression using siRNA. There was a corresponding slight increased in the amount of the intact Lu protein detected under these conditions. Thus, endogenous MT1-MMP is responsible for the constitutive shedding of the endogenous Lu in A431 cells.

To identify the site of the cleavage of Lu by MT1-MMP, we expressed a Lu protein that was FLAG-tagged at the C terminus in COS-7 cells (Fig. 5A, Lu-CF). Lu-CF was cleaved by an endogenous protease, and a 17-kDa C-terminal fragment was detected by an anti-FLAG antibody (Fig. 5C). Co-expression of MT1-MMP and Lu-CF generated a new 18-kDa fragment by Western blot analysis. The generation of both fragments was suppressed by incubation of cells with MMI270 (Fig. 5C). Thus, the 18-kDa fragment is the product of MT1-MMP-dependent cleavage. The 18-kDa band was transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane and subjected to amino acid sequence analysis from the N terminus.

Two amino acid sequences, 530NKRHV534 and 534VFHFG538, were identified that localized to the juxtamembrane region of Lu close to the fifth Ig-like domain (supplemental Fig. S3A). To examine whether MT1-MMP cleaves Lu protein directly and generates fragments having the two identified N-terminuses, a Lu peptide (520ISCEASNPHGNKRHVFHFGTVSPQT544) spanning both N-terminal amino acid sequences was synthesized. The peptide was incubated with the catalytic fragment of MT1-MMP. Analysis of the digestion fragments by MALDI-TOF MS revealed that MT1-MMP cleaves the peptide bond between Gly529 and Asn530 (supplemental Fig. S3B). In agreement with the preferential cleavage sites of peptide substrates by MT1-MMP (30), a proline residue is present at the P3 position. To confirm this is the primary cleavage site by MT1-MMP in cells, both two amino acids flanking the cleavage site in Lu-CF were substituted by alanine (Fig. 5D). This mutant Lu-CF (mLu-CF) was not cleaved by MT1-MMP when co-expressed in COS-7 cells (Fig. 5E). We do not think this mutation alters sensitivity of Lu protein to other proteases, because the 17-kDa fragment was still generated.

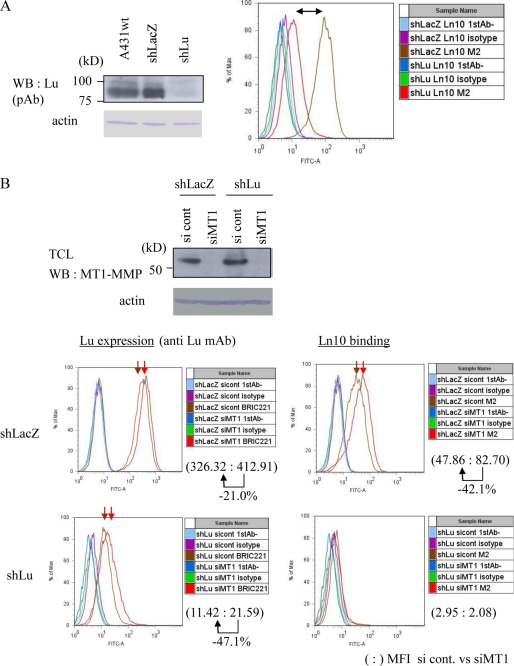

Effect of MT1-MMP on Lu-mediated Binding to Laminin-511

To analyze the effect of the MT1-MMP-dependent processing of Lu on the function of the latter, we employed FACS analysis to monitor the ability of A431 cells to bind FLAG-tagged laminin-511 using an anti-FLAG M2 antibody for detection. Although laminin-511 is a component of the basement membrane, we used a soluble form of this laminin to measure binding sites of the cells. To demonstrate Lu-dependent binding of the cells to laminin-511, the expression of Lu was knocked down using an shRNA targeted to Lu (shLu) or a control shRNA targeted to LacZ (shLacZ) (Fig. 6A, left). Binding of laminin-511 to A431 cells was observed following expression of the control shRNA vector (shLacZ) but was markedly impaired by knockdown of Lu following expression of shLu (Fig. 6A, right). Thus, binding of laminin-511 to A431 cells can serve as a surrogate marker to monitor Lu activity.

FIGURE 6.

Effect of MT1-MMP on the ability of Lu to bind laminin-511 in A431 cells. A, binding of laminin-511 to A431 cells. Expression of endogenous Lu in A431 cells was analyzed. Knockdown of Lu was performed using an shRNA targeted against Lu (shLu), or against LacZ (shLacZ) as a negative control. The ability of A431 cells in suspension to bind FLAG-tagged laminin-511 was analyzed by FACS using anti FLAG M2 antibody. Binding of laminin-511 to A431 cells was markedly impaired by Lu knockdown (right). B, effect of MT1-MMP on the cells' ability to bind laminin-511. Knockdown of MT1-MMP using an siRNA targeted to MT1-MMP (siMT1) or negative control (si cont) was performed using A431 clones expressing either shLacZ or shLu used in the experiment in panel A. The knockdown efficiency was confirmed (upper panel). Expression of Lu protein (left panels) and binding to laminin-511 (right panels) were analyzed by FACS analysis. Mean fluorescent intensities (MFI) of si cont and siMT1 cells were revised by MFI of the sample prepared without primary antibody and indicated as a colon (:) in each panel.

We first analyzed the effect of MT1-MMP on the level of Lu expressed on the cell surface. The expression of MT1-MMP was knocked down using siRNA against MT1-MMP (siMT1) or control RNA (si cont) (Fig. 6B, upper). Knockdown of MT1-MMP in A431 (shLacZ) cells increased the detection of Lu protein on the cell surface (Fig. 6B, lower panel, Lu expression). The knockdown cells also demonstrated an increased ability to bind laminin-511 (Fig. 6B, lower panel, Ln10 binding). However, A431 cells expressing an shRNA targeted to Lu (shLu) were unable to bind laminin-511, and this observation was not affected by knockdown of MT1-MMP (Fig. 6B, shLu).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have identified proteins that associate with MT1-MMP in A431 cells using an integrated Nano-Flow-LC/MS/MS system, and we were able to identify 163 such proteins, including 64 membrane proteins. To confirm whether these membrane proteins included substrates of MT1-MMP, we selected 18 of these and subjected them to further analysis. Co-precipitation of these proteins with MT1-MMP using an immunoprecipitation assay confirmed that these membrane proteins were indeed capable of interacting with MT1-MMP. Monitoring of each purification step of the column chromatography also suggested that a specific subset of membrane proteins were co-eluted with MT1-MMP.

Interestingly, in the immunoprecipitation assay, the test proteins showed differential affinity for the pro and active forms of MT1-MMP. The propeptide portion of pro-MT1-MMP is cleaved by furin or related proprotein convertases during transport from the trans-Golgi network to the cell surface, leading to the display of MT1-MMP on the cell surface as an active enzyme. Some test proteins, such as MT1-SP, EGFR, 5T4, DCP, and CD36L1, preferentially precipitated pro-MT1-MMP. The results presumably indicate that these proteins associate with MT1-MMP during the transport of vesicles to the cell surface. On the other hand, GA733-1, HAI-1, HAI-2, TF, THBD, and CD9 precipitated preferentially the active form of MT1-MMP indicating that these proteins may form a complex on the cell surface.

Half of the tested membrane proteins were cleaved by MT1-MMP in a MMI270-sensitive manner (Fig. 4 and supplemental Fig. S2). At least six of these proteins were able to interact with activated MT1-MMP in addition to the pro-MT1-MMP (Fig. 3B). Among the proteins cleaved by MT1-MMP, Lu was studied further. We first examined whether the endogenous Lu protein was processed by the endogenous MT1-MMP in A431 cells. Two distinct Lu fragments were shed from the cells, and production of one of these was inhibited by the knockdown of MT1-MMP (Fig. 5B). The size of the shed fragment roughly corresponds to the N-terminal portion of the 18-kDa C-terminal fragment. The N-terminal amino acid sequence of the 18-kDa Lu fragment was determined, and mutation of the cleavage site abrogated processing by MT1-MMP in COS-7 cells (Fig. 5E).

Although the biological role of Lu has yet to be determined clearly, it is known to bind laminin-511 (31). A431 cells expressing Lu showed Lu-dependent binding to laminin-511 by FACS analysis (Fig. 6A), and knockdown of MT1-MMP increased both the amount of Lu on the cell surface and the cell's ability to bind laminin-511. Lu can be processed by other metalloproteases as well, and the roles of different protease systems in the processing of the Lu protein remain to be fully elucidated. The processing of Lu may be differentially regulated by these proteases depending on the subcellular compartment in which they localize and in response to different local signals that regulate the interaction of Lu with these proteases.

Extracellular matrix metalloproteinase inducer (EMMPRIN), a member of the immunoglobulin superfamily, was also identified as an MT1-MMP-associating protein (Figs. 3 and 4). Since we identified EMMPRIN at a very early stage of this study, we had tested EMMPRIN in advance to Lu whether EMMPRIN is a physiological substrate of MT1-MMP (23). MT1-MMP cleaves EMMPRIN between the two extracellular Ig-like domains, and the shed fragment has the ability to stimulate fibroblasts to express MMPs. Because both EMMPRIN and MT1-MMP are frequently expressed in malignant tumor cells, the shed EMMPRIN could conceivably mediate MMP induction in the tumor stroma. Thus, EMMPRIN is another example that the proteins we identified in this study contain physiological MT1-MMP substrates. Several systematic approaches to identify MT1-MMP substrates have been reported to date (12, 32, 33). Hwang et al. analyzed cleavable proteins by MT1-MMP in human blood serum and identified 15 proteins (32), although these were not identified in our assay. The isotope-coded affinity tag (ICAT) MS method was successfully applied to identify many soluble form of substrates and membrane proteins shed into the culture media (12, 33). Interestingly however, only a few proteins, such as myoferlin, integrin α3, ALCAM, Kunitz-type proteinase inhibitor 2, and galectin-3-binding protein, were common with our result. Thus, we believe that our approach complements those methods, particularly in identifying membrane proteins. Our method also identifies non-substrate membrane proteins and cytoplasmic proteins that interact with MT1-MMP. These may regulate MT1-MMP functions or coordinate MT1-MMP activity with other cell functions.

In the previous study, we identified 158 MT1-MMP-associated proteins from human melanoma A375 cells (17). Among them, 61 proteins were identified again in the present assay (supplemental Fig. S4). The membrane proteins that we identified represented 28 and 39% of the total protein population in A375 and A431 cells, respectively (supplemental Fig. S4). Forty-five membrane proteins that interacted with MT1-MMP were newly identified in A431 cells. These proteins included those involved in cell-cell adhesion, such as cadherin 3, junctional adhesion molecule 1, and occludin. Because expression of these proteins is specific to epithelial cells, it is not surprising that these proteins were identified only in A431 cells. CD44 is expressed in both cells, but it was identified only in A431 cells. Even in A375 cells, CD44 was confirmed to associate with MT1-MMP (17). Therefore, sensitivity of mass spectrometry to detect proteins appears to be affected by complexities of the samples.

In summary, we have shown that systemic whole cell analysis can identify membrane proteins that are physiological substrates of MT1-MMP. Application of this method to cells in which MT1-MMP regulates important cell functions may provide a powerful approach to identify critical substrates for this regulation. Although we focused on membrane proteins in this study, other MT1-MMP-associated proteins may also modulate MT1-MMP functions in cells.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported by a Grant-in-aid for Scientific Research on Priority Areas “Integrative Research Toward the Conquest of Cancer” and was supported in part by Global COE Program from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S4 and Table S1.

- MMP

- matrix metalloproteinase

- Dox

- doxycycline

- FACS

- fluorescence-activated cell sorter

- LC/MS/MS

- liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry

- Lu

- Lutheran blood group glycoprotein

- MMI

- matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor

- MT-MMP

- membrane type-matrix metalloproteinase

- shRNA

- short hairpin RNA

- siRNA

- small interference RNA

- E/A

- catalytically inactive mutant containing an amino acid substitution from Glu240 to Ala

- EMMPRIN

- extracellular matrix metalloproteinase inducer.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lukashev M. E., Werb Z. (1998) Trends Cell Biol. 8, 437–441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Werb Z. (1997) Cell 91, 439–442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Itoh Y., Seiki M. (2006) J. Cell Physiol. 206, 1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Overall C. M. (2002) Mol. Biotechnol. 22, 51–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Egeblad M., Werb Z. (2002) Nat. Rev. Cancer 2, 161–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seiki M. (2003) Cancer Lett. 194, 1–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holmbeck K., Bianco P., Caterina J., Yamada S., Kromer M., Kuznetsov S. A., Mankani M., Robey P. G., Poole A. R., Pidoux I., Ward J. M., Birkedal-Hansen H. (1999) Cell 99, 81–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou Z., Apte S. S., Soininen R., Cao R., Baaklini G. Y., Rauser R. W., Wang J., Cao Y., Tryggvason K. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 4052–4057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chun T. H., Hotary K. B., Sabeh F., Saltiel A. R., Allen E. D., Weiss S. J. (2006) Cell 125, 577–591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ohtake Y., Tojo H., Seiki M. (2006) J. Cell Sci. 119, 3822–3832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tam E. M., Wu Y. I., Butler G. S., Stack M. S., Overall C. M. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 39005–39014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tam E. M., Morrison C. J., Wu Y. I., Stack M. S., Overall C. M. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 6917–6922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hotary K. B., Allen E. D., Brooks P. C., Datta N. S., Long M. W., Weiss S. J. (2003) Cell 114, 33–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kajita M., Itoh Y., Chiba T., Mori H., Okada A., Kinoh H., Seiki M. (2001) J. Cell Biol. 153, 893–904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nakamura H., Suenaga N., Taniwaki K., Matsuki H., Yonezawa K., Fujii M., Okada Y., Seiki M. (2004) Cancer Res. 64, 876–882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nagase H., Woessner J. F., Jr. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 21491–21494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tomari T., Koshikawa N., Uematsu T., Shinkawa T., Hoshino D., Egawa N., Isobe T., Seiki M. (2009) Cancer Sci. 100, 1284–1290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gavin A. C., Bösche M., Krause R., Grandi P., Marzioch M., Bauer A., Schultz J., Rick J. M., Michon A. M., Cruciat C. M., Remor M., Höfert C., Schelder M., Brajenovic M., Ruffner H., Merino A., Klein K., Hudak M., Dickson D., Rudi T., Gnau V., Bauch A., Bastuck S., Huhse B., Leutwein C., Heurtier M. A., Copley R. R., Edelmann A., Querfurth E., Rybin V., Drewes G., Raida M., Bouwmeester T., Bork P., Seraphin B., Kuster B., Neubauer G., Superti-Furga G. (2002) Nature 415, 141–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ho Y., Gruhler A., Heilbut A., Bader G. D., Moore L., Adams S. L., Millar A., Taylor P., Bennett K., Boutilier K., Yang L., Wolting C., Donaldson I., Schandorff S., Shewnarane J., Vo M., Taggart J., Goudreault M., Muskat B., Alfarano C., Dewar D., Lin Z., Michalickova K., Willems A. R., Sassi H., Nielsen P. A., Rasmussen K. J., Andersen J. R., Johansen L. E., Hansen L. H., Jespersen H., Podtelejnikov A., Nielsen E., Crawford J., Poulsen V., Sorensen B. D., Matthiesen J., Hendrickson R. C., Gleeson F., Pawson T., Moran M. F., Durocher D., Mann M., Hogue C. W., Figeys D., Tyers M. (2002) Nature 415, 180–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaji H., Saito H., Yamauchi Y., Shinkawa T., Taoka M., Hirabayashi J., Kasai K., Takahashi N., Isobe T. (2003) Nat. Biotechnol. 21, 667–672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Natsume T., Yamauchi Y., Nakayama H., Shinkawa T., Yanagida M., Takahashi N., Isobe T. (2002) Anal. Chem. 74, 4725–4733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Itoh Y., Takamura A., Ito N., Maru Y., Sato H., Suenaga N., Aoki T., Seiki M. (2001) EMBO J. 20, 4782–4793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Egawa N., Koshikawa N., Tomari T., Nabeshima K., Isobe T., Seiki M. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 37576–37585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.MacPherson L. J., Bayburt E. K., Capparelli M. P., Carroll B. J., Goldstein R., Justice M. R., Zhu L., Hu S., Melton R. A., Fryer L., Goldberg R. L., Doughty J. R., Spirito S., Blancuzzi V., Wilson D., O'Byrne E. M., Ganu V., Parker D. T. (1997) J. Med. Chem. 40, 2525–2532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kikkawa Y., Sasaki T., Nguyen M. T., Nomizu M., Mitaka T., Miner J. H. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 14853–14860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.El Nemer W., Gane P., Colin Y., Bony V., Rahuel C., Galactéros F., Cartron J. P., Le Van, Kim C. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 16686–16693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Suenaga N., Mori H., Itoh Y., Seiki M. (2005) Oncogene 24, 859–868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Udani M., Zen Q., Cottman M., Leonard N., Jefferson S., Daymont C., Truskey G., Telen M. J. (1998) J. Clin. Invest. 101, 2550–2558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kikkawa Y., Moulson C. L., Virtanen I., Miner J. H. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 44864–44869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kridel S. J., Sawai H., Ratnikov B. I., Chen E. I., Li W., Godzik A., Strongin A. Y., Smith J. W. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 23788–23793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kikkawa Y., Miner J. H. (2005) Connect. Tissue Res. 46, 193–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hwang I. K., Park S. M., Kim S. Y., Lee S. T. (2004) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1702, 79–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Butler G. S., Dean R. A., Tam E. M., Overall C. M. (2008) Mol. Cell Biol. 28, 4896–4914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.